Abstract

This curatorial dissertation proposes an exhibition exploring immersive textile-based artworks, and the relationship between artwork and viewer. Each artwork plays with a different immersion style creating an abundant multisensory experience, whilst including the audience within the artworks themselves. It seeks to be an engaging exhibition that rejects the traditional art gallery space, stimulating and encouraging engagement with the work and the medium of textile art.

I am proposing the setting for the exhibition to take place in Verdant Works High Mill building - a former jute mill which functions as a historic jute museum. The former mill thematically links with the textile pieces on show and already acts as an immersive educational space, whilst also providing a large space for the bigger installation pieces in this exhibition

Introduction

This proposal explores ways to engage visitors in immersive ways through the medium of textile-based installations, combining one of the oldest art-forms with modern gallery approaches The exhibition encourages interaction, exploration, and learning along with community-based approaches in traditional craftwork, creating an environment of education and curiosity.

Textiles are a fundamental part our lives from birth – from daily interaction through clothing and furniture they have become almost invisible to the average person. Early fibre crafts were often used to create tools and clothing, along with items for the home such as blankets and quilts. In the western world there has been a historic distinction between ‘Fine Art’ and ‘Craft’, with art referring to aesthetic-based practices such as painting and sculpture, and crafts to more utilitarian making such as weaving and woodwork (Markowitz, 1994) creating a culture of dismissal of the practice as an artform.

“The hand-made quilt will always be a "low" art form insofar as it is more meaningful in the home than on some gallery wall.” (Auger, 2000)

Over time as humanity figured out new ways to manipulate fibres, working with textiles became more decorative Often seen as ‘leisure art’, craftwork started to break the hierarchy in the late-19th century to the mid-20th century with movements such as the Arts and Crafts movement, Dadaism, the Fiber Arts movement and Bauhaus (Parker, 2010; Halperin, 2023) with artists like Anni Albers being the first textile artist to have a solo textile based exhibition at the New York MoMA in 1949 (Stehle, 2019).

The history of art gallery’s exclusion to crafts reflects a wider issue of gatekeeping and alienation in fine art. The functionality of craft due to its utilitarian status has resulted in lack of prioritisation in high art spaces. This highlights an element of classism, and often of misogyny, in which craft is devalued due to accessibility in materials and techniques to lower and middle classes. Historically, art institutions have a tradition of needing prerequisites in education to be able to understand and appreciate the artwork inside them (Bourdieu, 1979), which the admission of accessible crafts would sway due to larger masses being more familiar with the type of work, already having context to the craft.

Before fully exploring the topic at hand there is a clarification I want to make around the terms ‘immersive art’ and ‘immersion’. Through this proposal I use these terms in reference to the way in which the artworks are experienced. In the context of my proposal, immersive art and immersion refers to the ability for the artwork to have the ‘experiencer’ be a part of the world of the work and be more physically and mentally involved through multiple senses, rather than purely through viewership. The experiencer can be either creator or viewer, and the experience can be a-priori or a-posteriori to creation, similar to the immersive theatre experience in which actor and viewer are both active participants in the immersion process. I do not refer to the many ‘immersive’ exhibitions that use digital projections of paintings - usually of deceased artists - which offer no real 'immersion', due to the use of the paintings within the exhibition. That is, they are not being experienced in a way that can be considered truly transformative. The subjects featured still exist not only in their original formats (be that in galleries or similar) but are still very much presented in a way where any transformation is insisted upon the audience and is not necessarily left to unfold as intended as would be in its original setting. The popularity of these commercialised ‘immersive experiences’ representing around 29% of ‘immersive experiences’ (Barber, 2024) has influenced my proposal in gathering more traditional installation pieces that are immersive to the experiencer through innovative ways

The traditional placement of art in galleries for example flat on walls, or on plinths, lets the artwork be viewed in a passive manner. Philosopher and curator Laura U. Marks expresses the sentiment around fine art culture’s limitations, with the reduction to visual aesthetics and the focus on how ‘beautiful’ a piece is being detrimental to the viewership of art. She says about visual culture neglecting other senses:

“The turn toward visual culture has left in place the sensory hierarchy that subtends Western philosophy in which only vision and hearing can be vehicles of beauty It seems that the democratization of the object of aesthetic study to include high and low or popular arts has not really extended to non- visual objects.” (Marks, 2008)

This criticises the Western philosophy of art institutions regarding objects as valuable only for their visual elements, which is mirrored in the way museums and galleries display fine art.

Philosopher John Dewey believed that the shift of art from immersive daily experiences within community (such as religious paintings in churches, the dramatic recital of myths) to simply gallery art detaches the viewer and limits the art to being experienced for aesthetic value only

“The mobility of trade and of populations, due to the economic system, has weakened or destroyed the connection between works of art and the genius loci of which they were once the natural expression. As works of art have lost their indigenous status, they have acquired a new one that of ‘being specimens of fine art and nothing else’.” (Dewey, 1934).

Dewey expresses the way in which removing art from the original community context and limiting the ability to be experienced to only a museum destroys the art’s original function.

The move of art into museums creates a disconnect in how an audience can interact with an artwork, resulting in art and audience not influencing each other. It can also be argued that perception of art by an audience is already vital in the manifestation of art outside of the intent – similar to language as a form of communication needing two active participants – as “there is no art unless that stimulus acts upon an audience” (Gaertner, 1955; Sturtevant, 1947). Composer Jeffrey Mark wrote on attitudes about the role of audience pleasing in art and music stating that “Success in art is the usual sign of inferiority” (Mark, 1923), a sentiment which enables a public that often criticise contemporary art due to the conceptual nature making engagement with artworks more difficult, resulting in an audience that feel alienated (Martin, 2021). Museums should be responsive to a public’s concerns regarding accessibility in experiencing art, trying new approaches to attract a larger audience.

Immersive artworks break the traditional art ‘fixed’ viewing limitations found within museums by engaging the viewer through a range of devices aside from static visual aspects, stimulating multiple senses and the body through movement and play. When closing the distance between art and viewer, there is a higher involvement with the artwork not only physically, but emotionally due to the “passage from one mental state to another” caused by mental stimulation (Grau, 2003). The multi-sensory aspect of immersive installation takes the audience from static viewers to active participants. Active audience participation also reduces the pedestal in which an artwork is placed upon, due to the more literal accessibility.

Methods of Immersion

The versatility of immersive art can allow the stimulation of multiple senses - the combination of senses and movement allowing unique experiences. This can be done using various methods both with and without the use of technology.

Projection installations are the most common feature within immersive art (Barber, 2024) stimulating the sense of sight. These can be projections onto plain walls that transform the environment the viewer is in, but projection-mapping can cast images and textures onto sculptures or objects context within these spaces too. Audio-visual experiences can often be linked to projection art making use of sonic devices, creating a multi-layered soundscape stimulating hearing. Audio can be incorporated in other ways adding to various art mediums, creating an extra dimension surrounding the viewer.

Interactive art encouraging audience participation helps to create immersion in art. Methods of engagement within more traditional mediums such as sculpture are also possible and can include motion-based sensors, where the viewer must interact with the piece in a way that affects the work which can be done through movement or touch, immersing the viewer in the world of the art by letting them be an influential factor. We see this in Danny Rozin’s Mechanical Mirrors series which are sculptures using motors to reflect a viewer’s rough shape. When the viewer is gone, the ‘mirror’ reverts to a plain and still slate.

Just by moving through installations immersion is created by experiencing different areas of the artwork and uncovering details otherwise hidden. With Meow Wolf’s exhibitions and museums, viewers walk through various rooms and sculptures themselves, revealing more elements about them through their own exploration. This creates a sense of discovery in the viewer.

Utilising the sense of smell within artworks has been on the rise through Olfactory arts rejecting the dismissal of scent as a valid vessel of artwork (Shiner, 2020). As smell has the power to evoke strong emotions and memories (Rouby, 2002), this creates more personal engagement with the work

We can also find immersion in the method of creation

2. Curatorial Choices

The ten artworks within this exhibition all display diverse types of immersion. Not all of them will be interactive in the physical sense, but all offer visitors a space to explore and discuss Signage will accompany the works to let visitors know what ways they can interact with the artworks, along with history of the pieces and why they were chosen for this exhibition, allowing full transparency for the visitors (See appendix C, p.41).

The High Mill at the Verdant Works where the exhibition will take place is an important heritage site within Dundee, that not only provides history on Dundee’s jute industry, but serves to educate about the local community during the time of the industrial revolution. The High Mill space also hosts different exhibitions that explore local history outside of the mill. The cultural context that the museum provides allows locals to relate to the space through creating understanding of the space and objects they encounter, and fostering knowledge of a shared identity (Paris, 2006).

1

1 - The Dundee Tapestry (2022) – collaborative effort 35 tapestries 1 x 1m each Cotton fabric, embroidery threads

The Dundee Tapestry is a work of community made up of 35 hand embroidered panels depicting various elements of Dundee’s history and culture. This project exemplifies the theme of immersion through a community focussed method of creation, with over 140 stitchers involved the social interaction with the local Dundee and surrounding communities the Dundee Tapestry continues to encourage community involvement. By collaborating with the local community to tell the cultural story of the city, the city’s rich history is passed down through visual means by the people it represents, and whilst being created the stitchers have the opportunity to talk about what their panel represents. The city’s history with textiles is explored in this work adding not only local storytelling but site-specific context within the artwork displayed. Visitors can understand the works significance from a historic standpoint, reinforcing a space for shared learning and sparking conversation in viewers about Dundee’s history and shared culture.

The exhibition in Dundee’s V&A has the panels hanging from the top of frame stands, making the tapestries eye level. They also sit double-sided on these stands, allowing viewership from multiple angles. This display really appeals to me as the frames can be setup in any way in a three-dimensional space. By placing the panels at the entrance of the High Mill, I want to create a path into the rest of the exhibition, opening up a conversation about the world of textiles This also will share a space with the Red Box learning hub, encouraging the use of the space for the act of shared craft and conversation of community history.

Figure

Hub, 3rd Floor, Union Wharf, 23 Wenlock Road, London N1 7ST (2016) 259.2 x 464.1 x 202.5 cm

Polyester fabric, stainless steel

Hub-2, Breakfast Corner, 260-7, Sungbook-Dong, Sungboo-Ku, Seoul, Korea (2018) 271 x 325.9 x 356.8 cm

Polyester fabric, stainless steel,

Hub, 260-10 Sungbook-dong, Sungbook-ku, Seoul, Korea (2016) 297.18 cm × 259.08 cm × 165.1 cm

Polyester fabric, stainless steel

The work of Do Ho Suh explores themes of home and identity and often features threedimensional paper or fabric replicas of appliances from the home. Suh’s Hub series focuses on recreating his past living spaces out of sheer fabrics paying close attention to details such as fire escape signs and light switches. These are sculptures that viewers can walk through and imagine living in The Hubs are also modular and can be placed beside each other to create whole apartments and corridors, providing a larger immersive experience than one Hub, and a unique setup in any exhibition space I have chosen these three Hubs in particular due to the varying shapes and levels of detail, allowing for a more captivating walkthrough where each Hub is different from the last, whilst still not being too large for the High Mill space with the other artworks and support beams. This piece will also be in the open area of the High Mill towards the centre-west of the room

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

4 – Hubs (2016-18) – Do Ho Suh

5 - Hibiscus (2021) - Pallavi Padukone 86 cm x 132 cm Silk, cotton, earth pigments, hibiscus, indigo

Pallavi Padukone’s Reminiscent series is an olfactory textile experience, drawing inspiration from the ability for smell to trigger memories and express the chosen scents visually through patterns that are embroidered and weaved. She describes her practice as a form of aromatherapy using essential oils (Padukone, 2022).

Hibiscus is a work of embroidery on a sheer fabric with the scent of the hibiscus flower drawing the memory of her grandmothers red hibiscus plant in her garden in Bangalore (Padukone, 2022).

This is a unique piece in the exhibition, being the only one that uses the sense of smell. Viewers can feel and smell this piece up close, letting themselves imagine the garden that Padukone drew inspiration from.

This piece will be suspended between two beams closer to the north wall of the main High Mill room, benefiting from being a distance away from the wall as to let draughts naturally sway the fabric and let the aroma fill the air. This also helps the piece not blend into the wall of a similar tone.

Figure 8

8 - Petal Pusher (2008) – Maggie Orth 27.94 x 27.94 x 12.7 cm (variable)

DesignTex wool felt, embroidered rayon yarns, conductive yarns, acrylic, lamp and electrical parts

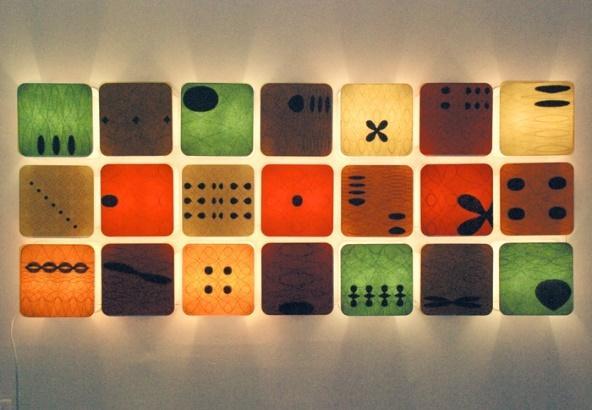

Maggie Orth was one of the first to use smart textiles in a creative manner through the use of technology within clothing at the MIT “Wearable Computing Fashion Show” (Orth, 1998). This series of light boxes patterned by textiles is a modular installation of interactive textile lighting which can be arranged on a wall or used as table lamps.

Viewer interaction in this installation is created through touching the electronic yarns and sensors in the patterns, signalling the light boxes to either dim or brighten in steps. The viewer chooses which boxes to light and by what degree, allowing viewer interaction to create the light and colour values within the work. With some of the boxes being darker with low contrast patterns embroidered, the audience’s choice to illuminate these boxes reveal the pattern. These two elements of visual control immerse the viewer in the art, allowing them to make their own creations in the process.

By including Orth’s work, this exhibition pays homage to her experimentation helping create the field of smart textiles.

Figure 11

Figure 12

13

9 - Inner Peace (2023) – Amelia Peng 3 x 10 m

Textiles Smart soft-system, organza, fibre optics, LED’s, electroencephalogram set

Amelia Peng’s work Inner Peace is a responsive installation combining textiles and audiovisual elements triggered by the viewers brainwave patterns read by an EEG set When installed at the London Design Biennale, viewers would listen to live performances or prerecorded pieces whilst the EEG headwear would record their brain data in regard to levels of focus or relaxation ([d]arc awards, 2023). The smart textile LEDs would then reflect the data through changing colours: “a green-blue light stands for high values in relaxation, while an amber-red light represents a peak in focus” ([d]arc awards, 2023). I chose this piece for its ability to bring together many different sensory experiences whilst still being a relaxing installation.

This piece will be hung from the north nook of the second-floor cascading into the first-floor balcony where it can be viewed alongside headphones for the viewer to listen to the recorded music in their own bubble. So that the audio elements are not competing, Inner Peace will be placed away from Yoo and Mathur’s sound pieces This will be a relaxing and restful floor paired with the final piece in this proposal.

Figure

3. Curatorial Influences

Through this proposal I have drawn influence from Scott Paris’ four principles for engaging visitors, fostering an environment that encourages interaction and active participation, along with engaging on a personal level and allowing dialogue about the works. Through having interactive elements alongside signage and conversational space, there are ways in this exhibition to provide meaningful transactions with objects. The signage additionally adds transparency to visitors, having context that allows for narrative knowing on how to interact with objects and why they were chosen. Furthermore, creating community within the visitors using the Red Box space accompanied by the Dundee Tapestries reinforces community learning and development. With these methods outlined by Paris, it is easier for visitors to relate to the pieces as they explore the exhibition, providing access to the final principleidentity development. The intention to create a space that is engaging to viewers and where knowledge of the art is accessible has influenced my curatorial choices in both considerations of the venue and the works themselves.

Target Audience

This exhibition is intended to reach a varied audience, with an initial focus on sensory seeking individuals of any age. This exhibition also aims to reach an audience otherwise rejecting engagement with contemporary arts due to inaccessibility around conceptual discussion and the inability for a lot of modern art to engage a wider audience. Whilst the artwork in this exhibition can be viewed under the theoretical lens, it is not mandatory to the ability to engaging with the works as there are various other methods the work itself uses to interact with the viewer.

I also want to create an exhibition that excites those usually not interested in visiting traditional art galleries and create a more exciting environment. By curating artworks which have multiple methods of immersion, this exhibition aims to have an experience for everyone - from people who want to be more interactive to those who want to just observe.

I have chosen the High Mill at Verdant Works in Dundee to be the location of the exhibition due to the rich history of the jute mill and how it functions to educate about Dundee’s textile industry. One of this exhibition’s aims is to have visitors reflect on how textiles are important, and this space provides a historic context for the audience.

Run by the Dundee Heritage Trust, the museum is a one of the few remaining jute mills still standing in Dundee. The former mill functions to educate about not only the history of the building but looks at the material and processing of jute itself and provides information on what the local community of jute workers was like in the Victorian times. By placing the exhibition in a historically working-class space removed from the traditional gallery atmosphere, the exhibition is more accessible to those who avoid galleries due to elitist preconceptions. The museum has a large collection of industrial equipment that was used in the mill during production. It is commonplace for schools to visit and have a demonstration of how the equipment worked, whilst learning about the history of not only the mill, but about their own where the city once stood as an industrial trade hub. Moreover, the museum has historical installations and mannequins both physically and digitally interactive, giving insight as to what the workers conditions and lives were like. It is already an engaging space with various resources designed to allow visitors to immerse themselves in the museum whilst educating themselves about Victorian times and Dundee’s history. The audience is encouraged to visit the rest of the museum and reflect on how the textile world has changed, comparing the industrial machinery and practical jute to the intricate craftmanship and technology displayed in this exhibition.

The High Mill itself functions as a social history museum, often hosting exhibitions that are educational such as the 2024 Tackling TB: Dundee Scientists Fighting the Killer Cough Exhibition which explored the local community’s experience of tuberculosis during the 19th century. There are a few historic pieces of jute processing equipment within the space, reminding visitors of the tradition of craft work and the history behind how textiles have managed to move from utilitarian and practical to pieces of art. Within the High Mill space, there is a learning hub called the Red Box functioning as a community learning venue where groups can meet. During this exhibition, this space can be used as a craft and discussion space, creating an area for discussion about the exhibition and having the visitors connecting with making craft themselves. This is a space that encourages social interaction, enhancing the themes of craft and immersion within the exhibition.

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art (2024) at the Barbican explores the undermined medium of textiles and how artists have challenged and embraced ideas about gender, politics, oppression, and power (Barbican, 2024). I find the Barbican as a building fascinating and so keep up to date with exhibitions occurring within it. Narrowly missing seeing it when I visited London in early 2024, finding out about this exhibition inspired me to further research the context of textiles within the Fine Art world as a textile artist myself. The exhibition features artworks from the 1960’s to present day exploring different methods of storytelling and textile art within the artworks, reflecting the diversity and evolution of the craft/artform.

The end of the exhibition has interactive elements that allow visitors to feel the textures of various textile methods used within the displayed works, creating a more personal link between artwork and viewer.

4. Other Influences

IKEA creates an enjoyable experience through their showrooms which are built to be more engaging than a typical shopping trip. The showroom designs that seem lived in have objects on display that are movable and motivate customers sense of touch and can allow shoppers to envision what their lives might be like if this kitchen and these products were theirs. The sense of touch creates an increased response and by having a meaningful transaction with the object there is a higher probability of purchase by acquiring knowledge on different

Figure 18

Figure 19

Bibliography

Arning, B; Neto, E. (2000) Ernesto Neto, BOMB, no.70

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40426241

Auger, E. (2000) Looking at Native Art through Western Art Categories: From the “Highest” to the “Lowest” Point of View, Journal of Aesthetic Education, 34(2) DOI: 10.2307/3333579

Barber, F; Szántó, A. (2024) Immersive Art Is Exploding, and Museums Have a Choice to Make, ARTnews Available at: https://www.artnews.com/art-news/opinion/immersive-artindustry-and-museums-1234715051/

Barbican. (2024) Press room

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican, Available at: https://www.barbican.org.uk/our-story/press-room/unravel-the-power-and-politics-oftextiles-in-art

Bourdieu, P. (1979) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Translated by Richard Nice 1984, Harvard University Press, ISBN: 0674212770

Chidambaram, S. (2023) Inside Meow Wolf’s Omega Mart: A Journey through the Surreal Intersection of Art and Capitalism, Medium, Available at: https://sarveshsea.medium.com/inside-meow-wolfs-omega-mart-a-journey-through-thesurreal-intersection-of-art-and-capitalism-7e20cf1de272

[d]arc awards, (2023) Inner Peace, UK, [d]arc awards, Available at: https://darcawards.com/portfolio/inner-peace-uk/

Dewey, J. (1934) Art as Experience, Capricorn Books, G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York 1958

Gowda, S. (2024) Duncan of Jordanstone Centenary Fund Lecture, Lecture given 08/10/2024, University of Dundee

Grau, O. (2003), Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion, The MIT Press, ISBN: 0-262-07241-6

Greer, B. (2008) Knitting for Good!: A Guide to Creating Personal, Social, and Political Change, Stitch by Stitch, Trumpeter, ISBN: 9781590305898

Greer, B. (2014) Craftivism, Arsenal Pulp Press, ISBN: 9781551525341

Halperin, J. (2023) Fiber Art Is Finally Being Taken Seriously, New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/11/t-magazine/fiber-art-textiles.html

Hulten, B. (2012) Sensory cues and shoppers' touching behaviour: The case of IKEA. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 40, DOI: 10.1108/09590551211211774

IKEA, (2024) IKEA Play Report 2024, Online, Available at: https://www.ikea.com/global/en/images/play_report_2024_55d5d8f782.pdf

Jenkins, D. (2003) The Cambridge history of Western textiles, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 0521341078

Kuiper, K; Yalzadeh, I. (2024) Anni Albers, Encyclopedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/biography/Anni-Albers

Kuusk, K; Tomico, O; Langereis, G; Wensveen, SAG. (2012) Crafting smart textiles: a meaningful way towards societal sustainability in the fashion field? Nordic Textile Journal.

Available at: https://research.tue.nl/en/publications/crafting-smart-textiles-ameaningful-way-towards-societal-sustain

Labarge, M. (1999) Stitches in Time: Medieval Embroidery in its Social Setting, Florilegium 16, available at: https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/flor/article/view/19198

Lave, J; Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation, Cambridge University Press DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Mark, J. (1923) The Problem of Audiences, Music and Letters, 4(4), DOI: 10.1093/ml/IV.4.348

Markowitz, S. J. (1994) The Distinction between Art and Craft, Journal of Aesthetic Education, 28(1) DOI: 10.2307/3333159

Marks, L. U. (2008) Thinking Multisensory Culture, Paragraph, 31(2) DOI: 10.3366/E0264833408000151

Martin, A. F. (2021) Why Everybody Hates Contemporary Art and Artists?, Medium, Available at: https://medium.com/counterarts/why-everybody-hates-contemporary-artand-artists-5500174b65d8

Mason, D; McCarthy, C. (2006) The feeling of exclusion’: Young peoples’ perceptions of art galleries, Museum Management and Curatorship 21 DOI: 10.1016/j.musmancur.2005.11.002

Mathur, N; Yoo, H. (2019) Sound Circles Taiwan Sonic Textile Installation, A' Design Award & Competition, Available at: https://competition.adesignaward.com/design.php?ID=80453

Mortaki, S. (2012) Key Issues Facing Art Museums in the Context of Their Social Role, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 16, Available at: https://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_16_Special_Issue_August_2012/14.pdf

Orth, M; Post, R; Cooper, E. (1998) Fabric computing interfaces. CHI 98 Conference Summary on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Association for Computing Machinery Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/286498.286800

Padukone, P. (2022) Reminiscent, Pallavi Padukone, Available at: https://www.pallavipadukone.com/reminiscent-2

Padukone, P. (2022) Hibiscus 52” x 34”, Instagram, 19/02/2022, Available at: https://www.instagram.com/pallu.padu/p/CaLFFAxPMMD/?img_index=1

Paris, S. G. (2006) How Can Museums Attract Visitors in the Twenty-first Century? In H. H. Genoways (Ed) Museum Philosophy for the Twenty-first Century, AltaMira Press, ISBN: 9780759107540

Parker, R. (2010) The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, New ed. I. B. Tauris ISBN: 9781848852839

Peck, J; Wiggins, J. (2006) It Just Feels Good: Customers’ Affective Response to Touch and Its Influence on Persuasion, Journal of Marketing, DOI: 10.1509/jmkg.70.4.56

Rouby, C. et al. (2002) Olfaction, taste and cognition, Cambridge University Press ISBN: 0 521 79058 1

Sabine, S. (2008) Fashionable technology: the intersection of design, fashion, science and technology, Springer, ISBN: 9783211745007

Shiner, L. E. (2020) Art Scents: Exploring the Aesthetics of Smell and the Olfactory Arts, Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780190089818

Stehle, B. (2019) Review of Anni Albers, Woman’s Art Journal, 40(2) Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27095961.

Sturtevant, E. H. (1947) An Introduction to Linguistic Science, New Haven ISBN: 0404148077

Szabo, J; Kuefler, N. (2015) The Bayeux Tapestry : A Critically Annotated Bibliography. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, ISBN: 978-1442251557

Tao, X. (2001) Smart Fibres, Fabrics and Clothing Fundamentals and Applications, Woodhead Publishing, ISBN: 9781855735460

Yoo, H. (n.d.), Projects, Github, Available at: https://jinnic.github.io/portfolio/

Young, J. O. (2010) Art and the Educated Audience, The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 44(3) DOI: 10.5406/jaesteduc.44.3.0029

Image Sources

Figure 1 – https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-tayside-central-68018397

Figure 2 - https://www.meer.com/irish-museum-of-modern-art/artworks/34846

Figure 3 - https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/32549/sheela-gowda/

Figure 4 – https://hyperallergic.com/539324/ernesto-neto-stimulates-bodies-and-mindsat-malba/

Figure 5 - https://aestheticamagazine.com/ethereal-architecture/

Figure 6- https://new.artsmia.org/stories/the-art-of-leaving-a-major-exhibition-shedslight-on-the-largest-global-movement-in-history

Figure 7 - https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/hub-260-10-sungbook-dongsungbook-ku-seoul-korea-do-ho-suh/jgEY17RFAcTzpA?hl=en

Figure 8 - https://www.pallavipadukone.com/reminiscent-2

Figure 9 - https://www.hyojinyoo.com/interactive-textiletouch/fi77718s4j9de07zplhw1flhimgif6

Figure 10 - https://www.hyojinyoo.com/sound-circlestaiwan/8elp6gcnae767gidj3zulouwnjb7m1

Figure 11 & 12 - http://www.maggieorth.com/art_PetalPusher.html

Figure 13 - https://www.innovationintextiles.com/smart-textiles-promote-mindfulness/

Figure 14 - https://www.pipaprize.com/pag/artists/ana-miguel/

Figure 15https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=399961220020940&set=a.399951186688610

Figure 16 - https://www.linkedin.com/posts/meow-wolf_best-art-explosion-omega-martactivity-7212528414623162368-Vwvr

Figure 17 - https://www.latimes.com/travel/story/2024-05-03/meow-wolf-los-angelesnew-location

Figure 18 – https://www.glamcult.com/articles/must-see-barbican-art-gallerys-unravelthe-power-and-politics-of-textiles-in-art/

Figure 19 - https://symbolsandsecrets.london/2024/04/11/unravel-at-the-barbican-anextraordinary-experience/