TOM SPEEDY

(dis)place

May 2025

DOI 10.20933/100001379

Except where otherwise noted, the text in this dissertation is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4 0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license.

All images, figures, and other third-party materials included in this dissertation are the copyright of their respective rights holders, unless otherwise stated. Reuse of these materials may require separate permission

Abstract

In (dis)place, I have carefully curated an exhibition of 10 oil paintings by Hurvin Anderson and Peter Doig. (dis)place will be held in the Fernandez Compound (Peter Doig’s Studio) in Port of Spain, Trinidad. The exhibition's title draws upon the challenges Doig and Anderson have faced when questioning their identity, culture, and sense of belonging My research has focused on past exhibitions, catalogues, books, interviews, and supporting archive material. Whilst both artists explore ideas about belonging, community, and commonality, ultimately, complex feelings of displacement have characterised their practice. The paintings often inhabit an otherworldly ‘no man’s land’ drifting between Caribbean and British landscapes. I intend the viewer to move between the two gallery spaces in a similar fashion.

I have also carefully considered ideas about curation and researched exhibitionmaking. My research has focused on curation from an artist’s perspective. The Fernandez Compound (a former rum Factory) is the perfect venue, allowing me a more creative and experimental approach to curation, outside the conventions of the white cube. I have also contributed to the ongoing conversation about identity and belonging by including one of my own artworks in (dis)place

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to several people who have very kindly supported my ongoing research into (dis)place. Firstly, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to Lisa and Martha from the Tate Library and Archive for granting me access to the reading rooms, where I explored an interview between Hurvin Anderson and Thelma Golden following his Peter’s series exhibition at Tate Britain (2009). I also wish to express my thanks to Tate Britain for preparing a selection of etchings, sketches, and study paintings by Peter Doig for me to view in the Tate’s archive room (2023). I would like to thank Kate McLeod for generously offering her time to talk about her exhibition antimonumental (2024) in a recorded interview which took place in my studio at DJCAD. I express my gratitude to Alan and Malcolm from the Contemporary Art practice workshop for their support and advice in the making of my exhibition model.

Above all, I would like to thank my tutor, Dr Helen Gorrill, for helping me stay motivated and positive throughout the dissertation process. Her generous knowledge, encouragement, and insights into exhibition-making have gone beyond the confines of my dissertation. I am confident that this curation of work by Hurvin Anderson and Peter Doig will influence my professional practice in the years to come.

List of illustrations

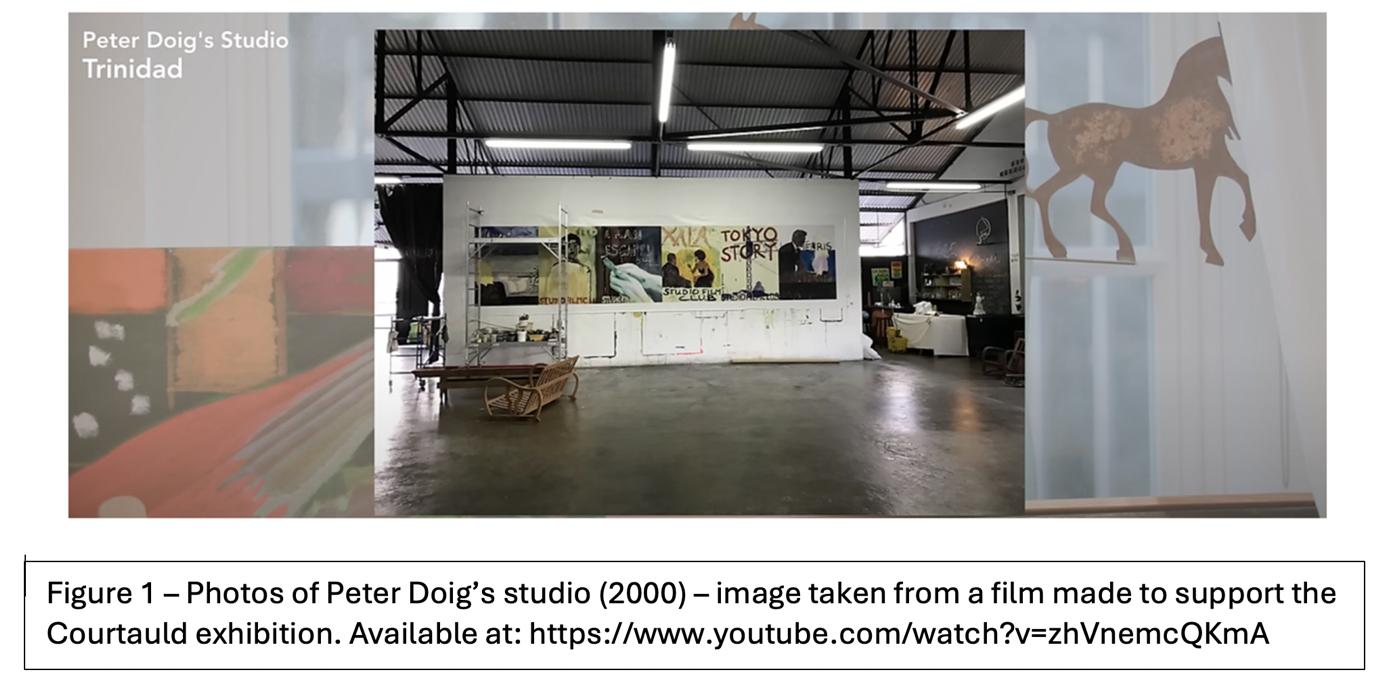

Figure 1 – Doig, P (2000) Peter Doig – in the Studio (The Courtauld) Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zhVnemcQKmA (accessed 4th December)

Figure 2 – Doig P (2000) Peter Doig: studiofilmclub – taken from: Peter Doig: Studiofilmclub. Germany: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König. page 130

Figure 3 – Bird’s eye view of gallery space illustrated by Tom Speedy (2024)

Figure 4 – Doig, P (2015) The Night Studio (Studio Film & Racquet Club), taken from: Peter Doig, Rizzoli New York. Rizzoli International Publications (2016) Page 123.

Figure 5 – Anderson. H (2008) Country Club: Chicken Wire, taken from: Hurvin Anderson: Reporting back, Ikon Gallery (2013) Page 135.

Figure 6 – Doig, P (2004) Pelican, taken from: Peter Doig in No Foreign Lands, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh (2013) page 121.

Figure 7 – Anderson, H (1997) Ball watching, taken from: Hurvin Anderson, Lund Humphries (2021) page 17.

Figure 8 – Doig, P (2017) Two Trees, taken from: Peter Doig, The Courtauld Gallery (2023) London, Page 33.

Figure 9 – Anderson, H (2004) Some People, The Welcome Series, taken from: Hurvin Anderson: Reporting back, Ikon Gallery (2013) page 49.

Figure 10 – Doig, P (2003) Xala, taken from: Hurvin Anderson: Reporting back, Ikon Gallery (2013) page 21.

Figure 11 - Anderson, H (2008) Back, taken from: Hurvin Anderson. New York: Rizzoli International Publications (2022) page 238.

Figure 12 - Doig, P (2004) Red boat (Imaginary Boys), taken from: Peter Doig. New York. Rizzoli International Publications (2016) page 311

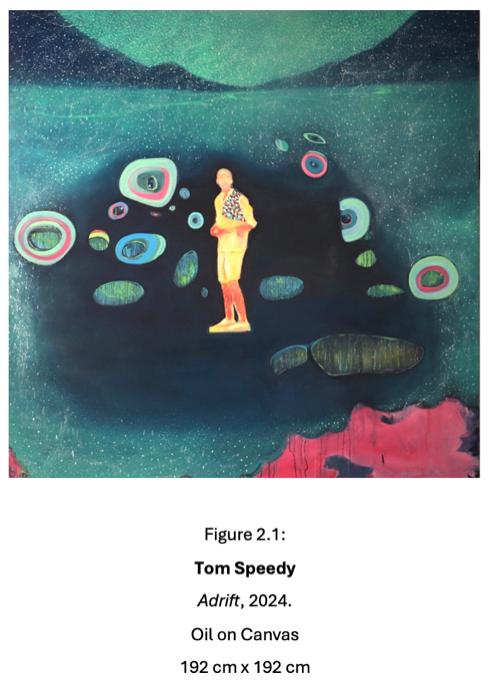

Figure 13 – Speedy, T (2024) Adrift, photo taken in my studio at DJCAD.

Figure 14 – Speedy, T (2024) Aerial 1:40 scale view of Fernandez Compound model

Figure 15 – Speedy, T (2024) The Fernandez Compound – adjusting lighting in Gallery 2

Figure 16 – Speedy, T (2024) The Fernandez compound – desired lighting in Gallery 2

Figure 17 – Speedy, T (2024) close up of Pelican, 2004 (figure 6).

Figure 18 – Speedy, T (2024) Xala, 2003 (figure 10) and Back, 2008 (figure 11)

Figure 19 – Speedy, T (2024) industrial gates (close-ups)

Figure 20 – Speedy, T (2024) raking gravel and volcanic black sand on the gallery floor.

Figure 21 – Speedy, T (2024) opened industrial gate in Fernandez Compound.

Figure 22 – Speedy, T (2024) intended outdoor window lighting in Gallery One.

Figure 23 – Speedy, T (2024) visiting Peter Doig’s Reflections of the Century, Musée d’Orsay, January 2024.

Figure 24 – Speedy, T (2022) visiting Leo Morocco’s ‘Long Road Home’, RSA, 2022

Figure 25 – Speedy, T (2024) industrial gate separating Gallery One and Two.

Figure 26 – Doig, P (2000) Peter Doig – in the Studio (The Courtauld) Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zhVnemcQKmA (accessed 4th December).

Figure 27 – McLeod, K (2024) Antimonumental, available at: https://www.thamessidestudios.co.uk/news/exhibitions/2024/antimonumental.

Figure 28 – Hall, S (2017) Familiar Stranger: A Life between Two Islands, London

Figure 29 – Walcott, D. and Doig, P. (2016) Derek Walcott, Peter Doig: Morning, Paramin. London: Faber & Faber Ltd.

Figure 30 – Doig, P (2013) Cricket Paragrand, taken from: Derek Walcott, Peter Doig: Morning, Paramin. London: Faber & Faber Ltd. Page 44

Figure 31 – Speedy, T (2024) Ebb and Flow, Montclair / Dundee University collaboration

Figure 32 –McGhie Jackson, E (2024) Dundee Mill Factory Gallery 2025

Figure 33 – The Twist (2024) Hurvin Anderson: salon paintings, accessed from: https://www.kistefosmuseum.com/exhibitions/hurvin-anderson-salon-paintings

Figure 34 – Anderson, H (2005) Hope Gardens, taken from: Hurvin Anderson, Double consciousness, reporting back (2013) ikon Gallery.

Figure 35 – Doig, P (2023) House of Music, taken from: Peter Doig, The Courtauld Gallery (2023) London, page 12.

Figure 36 – Doig, P (2002)- Gasthof Zur Muldentalsperre, taken from: Peter Doig, New York Rizzoli International Publications, Page 179

Chapter One - Curatorial Thesis……………………………………………………………..…….……12-16

a) Drifting, displacement, and challenges of Identity……………………..…………..……….….…12-14

b) Belonging, Commonality and Community .15-16

c) Concluding thoughts ……….16

Chapter Two - Curatorial Choices……………………………………………………………………….17-38

a)

b) 10 shortlisted

Chapter Three – Ideas about Curation and Exhibition Making…………..…………………..…39-45 The Street (2024) ………………………………………………………………………..…….………..….…..…39

of the Century (2024) ………………………………………..…………….……..................39

Trace Elements (2021) ………………………………………………………………..……….…….…….…….43 Peter Doig – in the studio (2023) ………………………

Kate McLeod and Tom Speedy in conversation about “antimonumental” …..45

Chapter Four – Other sources that have influenced my ideas………………..…………..…….46-51 Life Between Islands (2021-22) ………………………………………………..…………………..………….46

Stuart Hall, Familiar Stranger – A Life Between Two Islands (2017)..…...…..…....…………….…47

Derek Walcott and Peter Doig - Morning, Paramin (2016) ……

Peter Doig: No Foreign Lands (2013) ………………………… .…………49

Ebb and Flow (2024) ………………………………………………………….……………….………….……....50

Future Exhibition (2025) ………………………………………………………….………….……..…………….51

Hurvin Anderson: Salon Paintings (2024) …..…………………………………………….………..……….52 Conclusion …53-55

Introduction – Exhibition Dissertation

My exhibition, entitled (dis)place, will bring together ten figurative landscape paintings: five from Peter Doig (b. 1959), four from Hurvin Anderson (b. 1965) and one from Tom Speedy (b. 2003). The exhibition's title draws upon the challenges Doig and Anderson have faced when questioning their identity, culture, and sense of belonging. The paintings in this show evoke an untouched and otherworldly quality, which seems to drift between the Caribbean Islands and Great Britain. Despite Doig and Anderson being deeply involved in their surrounding communities, ultimately, notions of drifting and displacement have shaped their practice. Both artists battle with the awkwardness of feeling unable to immerse themselves entirely in their immediate environment due to the feeling of being an outsider. Feelings of isolation are also sometimes reflected in their works. This has been explored by Jennifer Higgie in relation to Anderson (Another Word for Feeling, 2013) and Richard Shiff in relation to Doig (Drift, 2016).

This exhibition takes place in the converted Fernandez Compound, an old rum factory in Port of Spain, Trinidad, a space that has also served as Peter Doig’s Studio. I aim to dissolve the boundaries between the traditional white cube gallery space and the natural world. I am creating a new space where light and air fuse in a tropical Trinidadian landscape.

Both artists have done a significant amount of geographical drifting. Peter Doig has lived a somewhat nomadic lifestyle: “Such uprooting and dislocation as Doig experienced can be both positive and negative…Doig shifted around the globe” (Gayford, 2024, p 222). He was born in Edinburgh in 1959 and spent his childhood between Trinidad and Canada. In 1979, he moved to London to study painting at Saint Martins and Wimbledon School of Art. He completed his master’s at Chelsea School of Art in 1990. In 2000, he was invited for an artist residency in Trinidad at the CCA with his fellow artist and friend, Chris Ofilli. Two years later, they both decided to make Trinidad their permanent residency. Peter Doig has created a sense of community through his passion for cinema by establishing STUDIOFILMCLUB, which he hosted within his studio every Thursday night. (Koegel, 2000, P134).

Hurvin Anderson is an artist raised in Birmingham: his work explores questions about his Jamaican heritage. He is the youngest of eight siblings and the only one to be born in Britain (in 1965) after his family emigrated from Jamaica in the 1960s. Anderson completed his undergraduate degree at Wimbledon School of Art (1994) and his MA at the Royal College of Art in 1998. During Anderson’s Masters programme, he was introduced to Peter Doig, who was holding a teaching position at the RCA. In 2002, Anderson joined a residency programme at the CCA in Trinidad, following Doig’s recommendation Doig had completed the same program in 2000. Trinidad has been vital in shaping the expressive painting styles of both artists. (Sherlock, 2021)

In preparation for this exhibition, I visited Tate Britain in December 2023 and studied Peter Doig’s etchings and drawings. I booked a one-on-one appointment at the gallery's archive, where I spent an hour observing, photographing, and drawing. In January 2024, I also had the opportunity to attend Doig’s exhibition at the Musee d’Orsay in Paris. This experience allowed me to see Doig’s own approach to curation as he had personally selected thirteen paintings from other artists in the Musee d’Orsay collection to be displayed alongside his own. Below each painting, Doig provided a thoughtful description, reflecting on how his own work speaks to an era of artists that preceded him. In October 2024, I revisited the reading room in Tate Britain to explore the archive of Hurvin Anderson’s exhibition, Peter’s Series (2009), in which he exhibited eight paintings depicting barbershop interiors.

As a curator, I am very interested in the discussions surrounding the artworks of Anderson and Doig. I have actively participated in the dialogue with this exhibition by introducing one of my own oil paintings. I invite the audience to delve deeper into meaningful conversation about displacement, drifting and isolation. This process has also helped me inform my own studio practice as I discover where my work lies within a conversation between Doig and Anderson. To help me explore this dialogue, I interviewed sculptor Kate McLeod, who recently took the role of curator in her exhibition Antimonumental (Thames-side studio, 2024). This exhibition interested me as her curation was informed by her experience as an artist. I will also be exploring this valuable relationship between curator and artist as I approach exhibition-making through the eye of the artist.

Initially, I considered a working title, Tradewinds, a cross-Atlantic Journey. The transatlantic Tradewinds are the powerful currents that help boats navigate smoothly between Britain and the Caribbean. It felt to me that the locations of Doig and Anderson’s landscape paintings were lost in the winds, adrift somewhere between the two islands. Although I felt this title might evoke ideas of drifting and displacement, I was also concerned that the word “trade” might carry unintended connotations of the slave trade. “UNESCO describes the slave trade as ‘the biggest tragedy in the history of humanity” (House of lord’s Library Briefing, 2019). Although the transatlantic slave trade was a very critical and devastating part of Caribbean and British history, I would feel uneasy and unqualified as a white, Scottish male to comment on such a traumatic period in history without sufficient insight into the topic. This working title didn’t fit with what I wanted to explore in this particular exhibition. Ultimately, I found myself drawn to the title (dis)place instead because it captures themes of drifting, displacement, and identity, as well as the other-worldly qualities that I believe are present in both artists’ work.

Chapter One – Curatorial Thesis:

Peter Doig and Hurvin Anderson have very different relationships with the Trinidadian landscape. Peter Doig spent his childhood living between Trinidad and Canada. The artist said “I’d lived in Trinidad as a child for almost six years. It felt close to me because of my past. I’d never really forgotten having lived there.” (Doig, 2014). When he returned to Trinidad for an artist residency in 2000 at Caribbean Contemporary Arts, it would have felt very familiar. Anderson first visited Trinidad in 2002, when he participated in that very same artist residency. His short time in Trinidad profoundly influenced his practice (Smith, 2024). Trinidad itself is a location that Anderson had little direct prior connection to, although he explores questions about Caribbean heritage in his work. When he visited Trinidad in 2002, “people he met assumed he was a local” (Higgie, 2013, p.12). This mistaken assumption is echoed in Anderson’s own experience of displacement, where unrelated places are intertwined.

Peter Doig - Drifting, displacement, and challenges of Identity

Despite Doig knowing the Trinidadian landscape very well, there is a lingering sense of an outsider’s perspective. In conversation with his friend and artist Chris Ofili, Doig remarks, “White culture here is quite marginalised, Local white people make up 0.67% of the population” (Doig, 2007). I think Doig’s painting often interrogates issues depicting a sense of place. The location appears distant or removed from Doig’s immediate surroundings. In an article by Sean O’Hagan, Doig said, “A big part of my work is about what is permissible to paint” (Doig, 2013) in a world that’s “slightly not mine to take” (Doig, 2016, p 407). Doig appears to be uncertain about “whether to address Trinidadian motifs and questions of race” (Lampert, 2023). The awkwardness of not knowing what is permissible to paint has resulted in paintings which appear lost or without origin.

Alice Koegel in her essay Terminus Museum (2000) argues that Doig’s Red Boat (Imaginary Boys), (Figure 12) evokes less of the Trinidadian landscape and instead presents a dreamlike, almost hallucinogenic quality reminiscent of paintings from another era. Koegel was reminded of Arnold Brocklin’s Island of the Dead (1883) and Henri Matisse’s Bathers with a Turtle (1908). Doig said “I don’t think of the present day as being that important to depict… [it] could be from long ago or right now” (Doig, 2023). There is a timeless, dislocated quality to Doig’s paintings. Jasper Sharp in an interview with Peter Doig felt that “Critics and Scholars … say that your paintings remind people of art from another time. They … remain both contemporary and speak to a tradition to painting”. (Sharp, 2017). Doig consistently resonates with his artistic practice with the generations that preceded him. This connection is evident in his 2001 painting titled “100 years ago (Carrera)” and his exhibition this year at the Musee d’Orsay titled, “Reflections of the Century” (2024).

I have noticed that many galleries emphasise the fact that Peter Doig is a ‘Scottish artist’. This was brought up in a conversation between Matthew Higgs and Doig in 2022, where Higgs remarked, “I notice in the press, especially the British press, even up until this week, he’s referred to as a Scottish painter” (Higgs, 2022). I find this somewhat misleading, considering Doig spent only the first 12 months of his life living in Edinburgh, and to the best of my knowledge, he has never painted a Scottish landscape. Doig himself has said, “It would be pushing it to call me a Scottish painter” (Doig, 2013). The artist’s work transcends the limitations of responding to any one specific culture or place. He “generates an atmospheric mood without referring to anything specific in the natural world” (Shiff, 2016, P345). Doig feels it would be an exaggeration to label himself an “anywhere painter” (Doig, 2013). His diasporic culture intertwines with his paintings, resulting in creations that appear unseen, enchanted, or even otherworldly.

Hurvin Anderson - Drifting, displacement, and challenges of Identity

I have detected a similar otherworldly quality in Hurvin Anderson’s paintings. I think this is due to his feelings of unease within the British Landscape. Anderson said, “We were still working out our place in Britain” (Anderson, 2013). His questions of identity and belonging are complex. There is a sense he often thinks about his roots in the Jamaican Landscape. Anderson allows “an English landscape…(to) echo a garden in the Caribbean, and vice versa.” (Higgie, 2013, p11). This concept is explored in Figure 7, where Anderson depicts a group of friends of Afro-Caribbean descent standing alongside a lake in Handsworth Park, Birmingham. These young men seem to be looking into the distance across the water as though yearning for a distant place. Anderson said he was “looking at British life through Caribbean eyes.” (Anderson, 2021). I noticed subtle changes in Figure 7, where Anderson has swapped the familiar English willow trees in Handsworth Park for a more tropical Caribbean palm tree.

Many of Anderson’s paintings seem to be charged with a wider social and political meaning. In Country Club: Chicken Wire (figure 5), the painting depicts a tennis court in an environment which should foster a sense of community. However, this is not the case; its location highlights the wider social and racial segregation in what is a postcolonial Jamaican society, where membership at a Country Club was not inclusive at all. The space appears deserted, and the court is only present through the silhouette of a wire fence. This restrictive grille prevents us from accessing the space. The painting has an overwhelming sense of depth and distance, which makes us feel removed and detached from the landscape. “In colonial times, these manicured landscapes conceal the grim realities of a land that is easy prey to criminally deregulated forms of neoliberal exploitation” (Smith, 2021, p.49). Anderson’s depiction of security grilles conveys an unsettling sense of foreboding, almost an anti-landscape

Hurvin Anderson - Belonging, Commonality and Community

Conversely, in other paintings (such as Back, figure 11), Anderson explores a very different experience of black identity and community. Hurvin Anderson has also shown an interest in depicting social spaces, gatherings, and sites of leisure. He has developed a significant body of work in his barbershop series. In conversation with Michael Prokopow, Anderson suggested these barbershops “partly represent the Caribbean in Britain” (Anderson, 2021). Over the last 80 years, Barbershops have played a crucial role in empowering communities, particularly for British black men (Ellams, 2017). Inua Ellams, the Poet and Playwright behind The Barber Shop Chronicles, stated in an interview with the Guardian that barbershops represent a “safe, sacred place for British Black men”. Similarly, Michael Prokopow noted that “Handsworth…is the most multicultural place in Europe. At least that’s how it was described in the 1990s and 2000s” (Prokopow, 2021). In Anderson’s Peter’s series, which was first exhibited at the Tate Britain in 2009, he explores his own relationship with these communal spaces. One of these paintings, Back (2008), is featured in Figure 11 of my exhibition. “The barbershops are part of a continuation of what I call the social space. Places where people meet and gather”. (Anderson, 2023, p31)

Doig - Belonging, Commonality and Community

Similarly, my choice of venue also leans into ideas of belonging and community. One of the two gallery spaces in Doig’s studio was the location of his STUDIOFILMCLUB (founded in 2002). This studio-run cinema club was founded with fellow artist Che Lovelace in Trinidad. Every Thursday night, the studio would be buzzing with discussion amongst local film enthusiasts (Koegel, 2000, P117). This initiative has helped Doig create his own sense of community, where locals could “watch films, but they could also visit the artists who were working in the studio” (Doig, 2022). In conjunction with each film screening, Doig would create a hand-painted paper poster to promote the next screening. One of these is shown in Figure 10: Xala (2003), which will feature in my exhibition. This shared space in what was his STUDIOFILMCLUB will serve as the unconventional gallery location for my exhibition, (dis)place.

Doig’s ongoing engagement with other artists has also been reflected in his teaching position at the Royal College of Art in London and the Fine Arts Academy in Dusseldorf. He “has continued to teach long after many people in his position probably would have given up” (Sharp 2017). Doig actively engages in creative conversations with other artists, students, and locals, making it an essential part of his practice and daily routine. For example, he has spent several years visiting Carrera Island, a prison on the coast of Trinidad, where he offers his time to help teach prisoners serving life sentences (Tomkins, 2017). The outline of this island has become a recurring symbol in Doig’s paintings.

Concluding thoughts:

There is an intriguing tension to explore between Doig and Anderson's interests in social and communal spaces, in contrast to complex ideas of identity and belonging, which ultimately shape their artistic practices. Despite their efforts, they find it challenging to capture a true sense of place, as they themselves feel displaced. “There is a push-me and pull-you” (Higgie, 2013, p.12) atmosphere where unrelated places can intertwine. The landscapes exhibit a new, vibrant, and untouched quality. I want the viewer to consider the uncertainty of place, drifting between the two gallery spaces, between the two artists, and between the Caribbean and British landscapes. As Alfred de Musset (1810-1857) said, “Great artists have no country”.

Chapter 2

Peter Doig has lived and painted in Trinidad since 2002, yet surprisingly rarely exhibits there. Doig has acknowledged the lack of suitable exhibition spaces in Trinidad. He also primarily works on a large scale, which means local audiences have limited opportunities to see his artwork, except in reproduction. Doig explains, “I have shown (work) there in smaller shows, but to be honest, there is no place to show bigger paintings… of that scale” (Doig, 2022).

The upcoming exhibition (dis)place would offer a unique opportunity for the Trinidadian community in Port of Spain to see Doig and Anderson’s work first-hand. I hope the feedback from the exhibition will address some of Doig’s anxieties about what is permissible to paint. (dis)place will be the first major exhibition of Doig’s work in Trinidad. This is surprising, considering he has spent half his life there. Catherine Lampert, director at the Whitechapel Gallery (1988-2001), recalled how “Doig imagines his Trinidadian and other lives coming together – rather than his leaving to meet artists in a metropolis or an art academy, people might come to the island, as a “Skowheganlike” place to work and get to know one another” (Lampert, 2016, p.412). The gallery consists of two spaces: Gallery One was once used as a painting studio, and Gallery Two screened films for Doig’s Studio Film Club. Each space is about 5,000 square feet, roughly the size of two basketball courts.

I was inspired by Doig’s initiative to invite locals into his STUDIOFILMCLUB. This exhibition, (dis)place, aims to embrace this community of film enthusiasts, as the venue has a well-earned reputation as a creative and communal space. Additionally, the venue welcomes an engaged audience of passionate locals who can drift between the two gallery spaces and immerse themselves in both artists’ work and lose themselves in the eerie silence and otherworldly atmosphere of the paintings.

Each of the ten artworks below is accompanied by an ekphrastic statement that I have written to expand upon my curatorial choices for (dis)place.

Figure 2 – Photo of Doig in cinema club – Sourced from Peter Doig – Studio Film Club (2000)

Figure 3 – Digital bird’s eye view of gallery space

The studio comes to life at night. The abstract crosshatching of a wire fence suggests the racquet court, where Doig and artist Che Lovelace would take breaks during their daily studio routine. The painting portrays a communal atmosphere. It evokes the STUDIOFILMCLUB, with Doig’s hand seemingly gesturing locals in. He encourages a refreshing, unpretentious search for community and a communal experience of film.

The evening heat is felt through the richness of the maroon studio floor. Beyond the figure, we catch a glimpse of what appears to be early trace elements of Doig’s painting Stag, 2002-2005. This artwork is crucial to this exhibition as it offers a unique chance to view an exhibiting painting on the site of its original creation

“Some nights the sweet, slightly putrid smell of fermenting molasses hangs in the air. The room is easily sixty by seventy feet, with a lofty, gently pitched roof – bare concrete floor, iron beams…The windows are open to the elements, so noises from the nearby Eastern Main Road and the hillside community of Laventille drift in continuously”. –

(Laughlin, 2000, p.134)

At first glance, Country Club: Chicken Wire may seem a beautiful study, a wash of turps in red and green. A deserted yet well-tended tennis court.

However, searching through the faint detail of a chicken wire fence leaves us feeling uneasy and displaced. We are uncertain whether the fence is keeping someone in or keeping us out. This added layer of security serves as a physical reminder of the history of racial and social segregation left from the colonial era. Here a membership at a Jamaican country club was not intended for locals.

“When you paint the grilles, you feel like you’re cutting into the landscape, a sacred thing. These things are not supposed to be there. They’re like anti-landscapes”.

(Anderson, 2023, p 13)

This is a haunting scene: a lone central figure dragging a lifeless pelican across a deserted beach in Trinidad a pale ghostly reflection in the shallows, as though reminiscent of a fading memory. A subtle suggestion of form. The location presented is arid and matte. The shadows are a dry mix of raw umber and viridian green. The canvas is bleached, raw and stripped of pigmentation.

In a moment too fleeting to capture on camera, Doig draws upon a further source, an image of a man dragging a net across a beach in India.

“The slippages of time and combinations of background and figure from two unrelated places” (Lampert, 2023, p22)

This painting poses a strong sense of yearning for a distant land. The painting, originally inspired by a photograph taken in Handsworth Park in Birmingham, mimics a Caribbean landscape. Anderson replaces the English willows with Palm trees. A distorted squeegee motion across the half-erased figures raises questions about belonging and place as history and memories collide.

The painting's sense of dislocation might raise questions linking back to the Windrush generation. The boat that landed at Tilbury, transported the first large groups of Caribbean people to the UK in 1948.

“It becomes a painting where the action of looking for the ball, other than identified in the name, is less present than this type of wistful longing that these young people seem to be looking at the water and a horizon line and distant places”. (Prokopow, 2021)

The painting captures the foreboding atmosphere of a tragedy, whilst Doig's presentation also exudes a haunting beauty. The landscape appears lost and paralysed within the sombre night sky and the shores of Trinidad.

An unlikely trio of (what appears to be) a cameraman, the fading transparency of a hockey player, and a man wearing a durag. The central figure is about to be convinced to make a life-changing decision. It is a painting stained in the reminiscence of human violence.

“There was a terrible incident in Trinidad, very close to where we live in the hills outside of Port of Spain… the killing was done by a seventeen-year-old boy who was being initiated into the gang.” (Doig, 2021)

“The filming, the guy with the camera…came from an incident I’d seen on the internet whereby these guys had filmed this man drowning on their cell phones and had posted it on the internet rather than actually attempting to save him”. (Doig, 2022)

The word "welcome" is placed at the top of the painting, ironically attached to the security grille. It appears decorative. However, its actual purpose is protection.

There is an awkwardness in understanding the distilled interior, as though we are invading someone else’s privacy. We perceive this space from an outsider's perspective.

In a painting dominated by an unwelcoming crimson mass, it is quite disorienting to grasp the composition of this image. These buoyant red rectangles pop out at us as we try to understand the different planes.

“It is this loaded sense of distance or otherworldliness that is pervasive in Anderson’s work, where conventional rules of perspective and structure are emphatically challenged.” (Chambers, 2013, p 77)

I question the opinion expressed by art historian and curator Alice Koegel that “Peter Doig’s film posters have never been created under the sign of “art”.

(Kögel, 2000, p 118)

Every Thursday night, the Studio Film Club comes alive with social interactions as passionate film enthusiasts gather to share a film-watching experience. Doig’s application of paint in Xala is thick and imprecise. The process leads to accidental scattering and spotting of pigmentation. The painting showcases the oscillation between representation and abstraction in Doig’s practice. The artwork conveys facts whilst still being expressive and free.

“Peter Doig’s posters knocked out on Thursday afternoons, and often hung while still wet, are a backdrop to this uncut scene.”

(Laughlin, 2000, p134)

This painting Back (2008) reminds me of Tam Joseph’s painting, “Is it OK at the back? (1983). It's an artwork charged with cultural references to the significance of barbershops for Afro-Caribbean people in Britain.

Anderson often avoids any direct confrontation by making the figures’ faces either blurred or non-visible. Here, the male figure has his back turned to us. This is one of the very few Peter Brown barbershop paintings which feature a figure. Anderson’s constructed colour pallet is curious. Red, white, and blue almost directly mimicking the Union Jack. It is a “smart and moving commentary on the history and the reconfiguration of Britain and Handsworth which we know is the most multicultural place in Europe.” (Prokopow, 2021)

“The barbershops are part of a continuation of what I call the social space. Places where people meet and gather”. (Anderson, 2023, p 31)

This painting is a scene of smoky trees with a wash of turpentine bleeding through the forest. Bleached shirts melt in the sun. Tree bark peels and blisters. A crimson kayak drifting aimlessly within this no man’s land - absorbed in a mass of emerald, green

There is uncertainty. Are these figures arriving or departing? The figures’ pose reflects Matisse’s Bathers with a Turtle (1908) whilst the drifting canoe resembles elements of Bocklin’s Island of the Dead (1883). Doig’s work consistently engages with painting from a different era.

“Figures in canoes and boats drift through Doig’s show, as though… biding their time, waiting to ferry us to the underworld”.

(Searle, 2008)

This artwork draws inspiration from Peter Doig’s 100 Years Ago (2001) and Hurvin Anderson’s Mrs. S. Keita – Blue (2010). Caught in a distant place, isolated from the outside world, a northern light shimmers. At the centre of the painting is the silhouette of a figure enveloped by a fragmented, swirling storm. The figure lacks any discernible features, yet it gazes directly outwards. Abstracted portals serve as its eyes. A languid silence, a distant horizon, a feeling of separation. Uncertain, displaced, paralysed.

Figure 14 – aerial view of the gallery – 1:40 scale model of The Fernandez Compound Port of Spain, Trinidad.

Figure 15 – The Fernandez Compound – adjusting lighting in Gallery Two Gallery Two

Figure 16 –The Fernandez Compound – desired lighting in Gallery Two Gallery Two

Figure 17 – close-up of Pelican, 2004 (Figure 6) – figure to scale

Gallery One

Figure 18 – close-up of Xala, 2003 (Figure 10) and Back, 2008 (Figure 11) Gallery Two

19 – industrial gate - close ups

Figure

Figure 20 – raking of gravel and volcanic black sand on the gallery floor of the Fernandez Compound.

Figure 21 – opened industrial gate in Fernandez Compound.

355 cm

Figure 22 – intended outdoor window lighting in Gallery One

Chapter Three

In preparation for my exhibition (dis)place, I have explored a variety of ideas about curation and exhibition-making.

In November 2024, Doig curated The Street in the Gagosian in New York. Doig exhibited his work alongside artists such as Francis Bacon (1909-1992), Max Beckmann (18841950) and Mark Rothko (1903-1970). Two of Doig’s past students from Kunst Akademie, Düsseldorf also featured in this cross-generational exhibition. In an online interview with Richard Shiff, Doig stated, “Larry [Gagosian] immediately recognised the potential for an exhibition informed by the eye of a painter, rather than a curator or gallerist, and is the ideal partner to bring it to fruition” (Doig, 2024). I think it is interesting to view curation from the artist’s perspective. Doig has created a visual dialogue across three generations of artists. For my exhibition, I have decided to include one of my paintings Adrift in the curation. I too, have engaged in a dialogue with Doig and Anderson by exploring ideas of displacement.

In January 2024, I visited Doig’s Exhibition “Reflections of the Century” at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris (shown overleaf in figure 23). I was intrigued by the layout of the exhibition in one of the museum's large cupola rooms: Doig’s works were displayed stacked on top of each other due to the unconventional dimensions of the space. Doig commented on the exhibition, saying, “There wasn't a special room for making an exhibition really, a room had to be found” (Doig, 2024). In this exhibition, also curated by Doig, he selected a series of works from artists in the Museum’s archive to accompany his work. These paintings were displayed in a neighbouring room and included artists such as Monet, Cezanne, and Rousseau. I thought this exhibition established the remarkable dialogue Doig’s work shares with artists from the past. He also wrote a commentary about each of the paintings and why he chose them. I have done something similar in my curation of (dis)place.

Figure 23 – visiting Peter Doig’s “Reflections of the Century”. Musée d’Orsay (2024).

I have deliberately included two works in my curation that might risk seeming misplaced within the formal context of an exhibition. Doig’s study, Xala (2003) (figure 10) is a painted poster originally intended to advertise his studio film club. Hurvin Anderson’s charcoal study Ball-watching (1997) (figure 7) is an early study in his wellknown Handsworth Park series. I believe something is revealed about the bold and experimental nature of such artworks. In more finished work, the process can feel lost within the layers of paint. (Gayford, 2024) In (dis)place, I feature a combination of resolved large-scale paintings and smaller, more experimental, and loosely executed works. Employing the Fernandez Compound (Doig’s studio space) will take us back to the beginning of the artistic process. The playful and gestural qualities captured in the artist’s studio can otherwise be muted within the walls of the white cube (Muhammad, 2015). There is a risk that the artist’s voice can be hidden from view or even edited out unwittingly by the curator.

Leon Morocco’s retrospective exhibition Long Road Home at the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh (2022) really interested me. The exhibition offered a glimpse into Morocco’s artistic process through reinstalling his studio space in the midst of finished work (figure 24). It was as though I had stepped into his working environment, providing me with a rare insight into the artist’s often chaotic process. I also went to visit the permanent installation of Eduardo Paolozzi’s (b.1924) studio space, which has been recreated within the Modern Art Gallery in Edinburgh. If space and funding were available, I would consider leaving traces of both artists’ studios untouched within my exhibition. This might include archive source material, sketchbooks, and works in progress from Doig’s studio and Anderson’s residency at CCA during his time in Trinidad

Figure 24 – Photo from my archive when visiting Leon Morocco’s exhibition. “Long Road Home” RSA (2022)

I have also been influenced by the artist-run exhibition Trace Elements | 1971 (2021), which took place in a 100,000-square-foot industrial warehouse located on the Thames in North Woolwich, Newham. The exhibition was one of the largest and most successful events of the London Frieze Week (Westall, 2021). In an interview with Recreational Grounds, Eric Thorp and Nicholas Stavri said that the Trace Elements exhibition “is a chance to be bold and try new things. We like to be ambitious, and the work will spill out to fill the space. We want to use the height, the architecture and the light that will spill in through the huge expanse of windows. The exhibition process is really important to us – we always encourage collaboration between the artists and curators”. (FAD magazine, 2021) My exhibition’s space, with its segregated industrial gates at the Fernandez compound, will echo the security grille elements in two of my selected Anderson paintings (figure 9 and figure 5). In my model, I have intentionally placed Anderson’s paintings on walls facing the industrial gates so they can be viewed across the gallery space from the opposite room (shown in figure 25). This further reinforces Anderson’s ideas about the ‘anti-landscape’ and feelings of displacement.

Figure 25 – Industrial gate separating Gallery 1 and 2

In a short online documentary-style film, Peter Doig – In the Studio (The Courtauld), we have the chance to see inside Doig’s studio space, where my exhibition takes place. Unusually, the building lacks glazed windows, so the space is open to the elements and the barred windows allow air and the breeze to mingle within the space. “The windows are open to the elements, so noises from the nearby Eastern Main Road and the hillside community of Laventille drift in continuously” (Laughlin, 2000, p.134). It is unusual for an exhibition space to be able to interact with the outside world in this way, but it might enhance the sensory experience of those attending the exhibition. My scale mode (Figure 15) recreates the bars on the windows in Doig’s studio (figure 26).

Figure 26 – screenshot from a documentary (2023)

Peter Doig – In the Studio | The Courtauld

I organised an interview with sculptor, researcher, and curator Kate McLeod about her recent exhibition Antimonumental (2024) (figure 27) in London, where she served as both curator and artist. As an artist approaching curation with little prior curatorial experience, I was eager to hear McLeod’s thoughts on the public’s response to her show, considering it was her first as a curator. She recollected the public’s feedback, noting. “The exhibition felt different because it was curated by artists, it was experimental and playful.” (McLeod, 2024). This aligns with my research into Jeffrey (2015) and Buckley and Conomos (2019), who found that artist-based curators expressed themselves more freely in exhibition-making than curators without an art background.

Figure 27– Antimonumental (2024) curated by Kate McLeod

Chapter Four

In preparation for my exhibition (dis)place, I have conducted wide research into a range of sources including exhibitions, interviews, books, catalogues, and films.

My research has led me to books such as Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s–Now (2021), which provided valuable insights into the Tate’s first exhibition celebrating 70 years of Caribbean-British art (2021-2022). I was also struck by the curatorial choices in Claudette Johnson’s Turner Prize show (2024). While exploring Johnson’s ideas about identity, I came across Stuart Hall’s book Familiar Stranger: Life Between Two Islands (2017). Additionally, I explored the collaboration between Derek Walcott and Peter Doig in their book Morning Paramin (2016). Finally, Peter Doig’s exhibition at the RSA in my hometown of Edinburgh titled No Foreign Lands (2013) made an important, lasting impression and influenced my curation of (dis)place.

Tate Britain's exhibition Life Between Islands (2021-2022) is the first and only exhibition to feature work by Peter Doig and Hurvin Anderson. The exhibition “follows 70 years of tumultuous history” (Cumming, 2021) through the works of 40 artists who have either migrated to Britain from the Caribbean or were inspired by Caribbean themes and heritage. I was fascinated by an accompanying interview recorded by Amy Sherlock with Doig and Anderson in which she explored their relationship with Trinidad. She asked, ‘Does the awkwardness of not feeling totally at home allow you to get at something deeper about a place or subject?’ (Sherlock, 2021). In conversation with Matthew Higgs, Hurvin Anderson said ‘I had always felt a double-edged thing about who I was and where I came from. In Trinidad I could be all these things, I was the Englishman, but I was also the Jamaican. It was an interesting place to explore this no man’s land, you could kind of drift back and forwards between these identities.’ (Anderson, 2011). I am fascinated by the idea of a ‘no man’s land’ and the sense of artistic freedom it might bring. The ‘awkwardness of not feeling at home’ which Sherlock identified is the very thing that Anderson valued during his residency in Trinidad.

In November 2024, I visited the Turner Prize exhibition at Tate Britain and noticed a corresponding theme to my own show, particularly regarding the complexity of identity and memory (Farquharson, 2024). One artist, Claudette Johnson (b.1959) nominated for her solo exhibition Presence at the Courtauld Gallery, felt that “our identity is not fixed, but is created and changeable” (Johnson, 2024). Johnson suggests that a shifting identity might allow an artist the freedom to explore complex and undiscovered ideas about themselves. This idea aligns with my reading of Stuart Hall’s book, Familiar

Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands (2017). Hall observes that “Identity is not a set of fixed attributes... but a constantly shifting process of positioning.” (Hall, 2017, p.16). This account of identity explains why Anderson and Doig’s paintings may feel displaced as they explore their diasporic identity. In Figure 1.3, Pelican (2004), the person is portrayed in isolation. In Doig’s work, this perhaps reflects that his own journey has been a solitary one. This is something I have explored myself in my painting Adrift (2024) (Figure 2.1).

Figure 28 – Stuart Hall (b.1932)

Familiar Stranger - A Life

Between Two Islands (2017)

I have read Morning, Paramin (2016), a collaboration between Nobel prize-winning Poet Derek Walcott and artist Peter Doig. In this book, Walcott published 51 poems, each responding to one of Doig’s paintings. Many of these poems reflect upon Trinidadian culture, traditions, and history. When writing my own explanatory statements for each of the 10 artworks in (dis)place, I adopted Walcott’s ekphrastic style of writing. This descriptive writing style allows me to bring a new narrative to the work. Da Vinci’s words, ‘Painting is poetry seen rather than felt, and poetry is painting that is felt rather than seen’ (Da Vinci – b.1452-1519) resonated with me. I hope my ekphrastic descriptions contribute something fresh and dynamic to the exhibition. Rather than simply providing straightforward descriptions of each image, they could be appreciated as an art form in themselves.

Figure 29 – Walcott and Doig, Morning, Paramin (2016)

I felt a particularly strong connection to Peter Doig’s exhibition, No Foreign Lands, at the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh in 2013. Although I was only 10 at the time, one painting, Cricket (Paragrand) (figure 30) stood out to me. My dad bought a poster of this painting at the gallery shop for me as a passionate cricket player and I grew up with this poster on my wall. This painting made an impression on me as a young artist. The title of the exhibition, No Foreign Lands, originates from the book “The Silverado Squatters” (1884) by Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson (1850 -1894). Stevenson observed that “there are no foreign lands. It is the traveller only who is foreign.” Whilst it might be true that there is no such thing as a foreign land, I would argue, in the case of Anderson and Doig, that there are no true ‘motherlands’ either. Doig said ‘I have always been an outsider. Even in London. If I returned to Scotland, I’d feel a complete foreigner.’ (Doig, 2012)

Figure 30 – Cricket (Paragrand), 2006-12 exhibited in No Foreign lands, RSA (2013)

In my own practice, there have been two significant exhibitions one past and one upcoming that have greatly influenced my ideas about curation. Firstly, in Ebb & Flow (2024) (figure 31), I took on the dual role of artist and curator in a transatlantic exhibition organised by students from Montclair State University and the University of Dundee. This collaborative project taught me the importance of effective communication over long distances. It provided me with experience in problem-solving and finding solutions in situations where face-to-face contact with other artists was not possible. Gaining this experience in exhibition-making gave me the confidence to select an exhibition format for my dissertation. In (dis)place, I would also be working across the Atlantic and showcasing work from artists with whom I have had no prior face-to-face contact

Collaboration between Montclair State University and the University of Dundee

Figure 31– Tom Speedy “Ebb and Flow” (2024)

In February 2025, I will be exhibiting with two other artists in a newly converted red brick mill in Dundee (Figure 32). There are some similarities between this venue and the Fernandez Compound in (dis)place. Both are former industrial spaces; both have been repurposed as artist’s studios. Although separate from my dissertation exhibition, it will allow me to exhibit my painting Adrift (figure 13) for the first time. If (dis)place were to materialise, I would consider updating my proposal by showing photos of my work in the venue below (figure 33). Others could then envisage how my work might look within a former industrial space like the Fernandez Compound in Trinidad

Figure 32 – Dundee Mill Factory – a new exhibition space opening in 2025.

The newly converted Twist Gallery in the Kistefos Sculpture Park in Norway hosted an exhibition, Hurvin Anderson: Salon Paintings. The space itself is unconventional. In addition to three exhibition venues, it also functions as a bridge and a sculpture connecting a communal woodland. The gallery’s owner, Christen Sveaas, explained, “The idea is that you make a round trip. You have to pass through the art exhibition, whatever it may be, to see the entire park. The new gallery knits the whole place together.” (Sveaas, 2019). In the Fernandez Compound, I have been experimenting with my own ways of encouraging people to flow naturally around the space. I hope, a little like the Twist Gallery, that the space would help to bring a similar connection for visitors between the work and this place.

Figure 33 – Hurvin Anderson’s “Salon paintings” in the Twist Kisefos, Norway (2024)

Conclusion

This exhibition (dis)place delves into the complex challenges faced by Peter Doig and Hurvin Anderson as they navigate questions of identity, culture, and sense of belonging. As the viewer walks around and between the two galleries, I think it is appropriate to describe the collective essence of the space. There is tension in the works, as notions of belonging are disrupted with unsettling feelings and disarray. The paintings evoke unearthly and ambiguous qualities. Both artists view their worlds as outsiders. Their paintings inhabit this in-between space, shifting between Caribbean and British landscapes, just as the viewer moves between Gallery One and Gallery Two.

In curating this show, I am aware of the slight imbalance of research between Anderson and Doig. It was, perhaps, inevitable that my research would lean more towards Doig. He was the artist who first led me to consider this exhibition, and it is his studio space that serves as the venue. Despite this, I feel that the industrial quality of the venue is well suited to Anderson’s paintings. The industrial gates separating the two galleries echo the segregated chicken wire fence and security grilles in Anderson’s work. I am interested in the history of the physical materials used to construct the Gallery space at the Fernandez Compound. Doig stated in an online video published by the Courtauld that the “steelwork was shipped down from Scotland” (Doig, 2023). The space itself holds a link between the Caribbean and Britain. I have already discussed the significance of the venue as a communal space in which to enjoy cinema. Importantly, the theme of the exhibition highlights that this search for a community was not a simple or linear journey.

I am aware of Doig’s prominent position within the world’s art market as one of the most successful living painters. In 2007, Doig’s painting White Canoe was sold at auction for what was then a record price for any living European painter. Due to worldwide demand, particularly from private collectors, it might be challenging to pull together my exact choice of Doig’s work. In a conversation with Ulf Küster, Doig reflects, “There are many, many paintings of mine that I don’t know where they are anymore… so when you’re making an exhibition, it becomes difficult… Some disappear” (Doig, 2014). The paintings themselves become displaced, but my virtual exhibition has allowed me to choose freely. There was also limited information about the Fernandez Compound, as it is a private studio space thousands of miles from where his work is usually exhibited. The information I gathered about this space was mostly found in interviews with Peter Doig or in his book STUDIOFILMCLUB (2000)

I thought a traditional white cube gallery space might be less creative and more rigid in possibilities for curation. An exhibition in an industrial space (a converted rum factory) would offer exciting and creative potential. What was even better was the idea of using Doig’s studio space, given that I was interested in curation from an artist’s point of view. The two identical-sized spaces had their advantages; however, there were also restrictions. I was only permitted to have ten artworks in the show, and I selected two smaller works as part of this. On reflection, this might not have been as successful as I had originally envisioned. Perhaps if there was an adjoining room, this would have suited the smaller paintings and avoided their effect being muted alongside larger work. I had considered other canvases (see appendix), and these might have worked very successfully in their place. It was only when I had constructed my scale model that I appreciated the difference in size and the impact this might have. I was very pleased with the model I had constructed. I used black volcanic sand for the flooring and added the security bars on the windows to reinforce the industrial nature of the site. I felt the dramatic lighting in the photographs served the space well.

Finally, it is important to return to the paintings in this exhibition to underline why they were chosen. Despite their scale, the spaces portrayed in Anderson’s work appear more enclosed than in Doig’s. In Anderson’s figure 5 and figure 9, we are left looking in through the security grilles from an outsider’s perspective. There is a feeling of separation. Anderson describes these works as “anti-landscapes” (Anderson, 2023, p 13). However, in his Barbershop series (figure 11) an enclosed interior evokes the opposite, there is an inviting sense of belonging in the social space. The figure has his back to the viewer, and I felt that this was a strong contrast with my own painting Adrift (Figure 13) in which the confrontational figure stares directly outwards and beyond the canvas I decided to display these paintings next to one another.

Feelings of ambiguity and uncertainty are powerful elements when trying to understand the drifting narratives in Doig’s work. Recurring distant and distorted horizon lines characterise the works I have chosen. Two paintings (figure 6 and figure 9) were both influenced by tragic incidents that Doig had witnessed or heard about in Trinidad. The landscapes in these works seem vaster; the figure is overwhelmed by the scale of the imagined land, and there is an enchanted, almost otherworldly quality. However, figure 10 and Figure 4 portray something rather different; there is a welcoming hand in Doig gesturing towards the Studio Film Club community in figure 4. And yet I noticed the cross-hatching gate in the midground of this painting and wanted to pair it with Anderson’s security grilles (figure 9). This reminds us that a more sinister and foreboding undertone is never far away in Doig’s work. The purpose of my exhibition is to raise complex questions about belonging and displacement rather than providing simplistic answers. The work is rich and nuanced in meaning, and I hope that my exhibition reflects this.

Interviews: Peter Doig

Reference List

Doig, P. (2014) Artist Talk: Peter Doig in Conversation with Richard Shiff Interviewed by R. Shiff for Fondation Beyeler, 25th November 2014. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I3jJ1CoyWLM (Accessed: 25th August 2024)

Doig, P. (2014) Artist talk with Peter Doig Interviewed by U. Küster for Fondation Beyeler, 25th June 2014. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qsUEFkQTyKI (Accessed: 10th July 2024)

Doig, P. (2021) At home: Artist in Conversation | Peter Doig Interviewed by S. Wagstaff for The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 5th November 2021. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vZtFBcvSNB8 (Accessed: 17th September 2024)

Doig, P. (2019) Exhibition talk: Peter Doig and Matthew Higgs Interviewed by M. Higgs for the Secession Vienna, 11th April 2019. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zJAqtQR2cug (Accessed: 21st August 2024)

Doig, P. (2014) Media conference at Fondation Beyeler: Peter Doig. Sam Keller, Peter Doig, and Ulf Küster Interviewed by S. Keller and U. Küster for Fondation Beyeler, 24th November 2014. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WWa7RD9oqzI (Accessed: 2nd November 2024)

Interviews: Peter Doig (continued)

Doig, P. (2018) Peter Doig and Matthew Higgs in Conversation | Groundwork Interviewed by M. Higgs for Groundwork, 26th May 2018. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q23w1cBFHC0 (Accessed: 22nd July 2024)

Doig, P. (2020) Peter Doig and Ono Masatsugu in conversation Interviewed by O. Masatsugu for the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 28th September 2020. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jvdj6LfWTSo (Accessed: 30th October 2024)

Doig, P (2024) Peter Doig and Richard Shiff Interviewed by Richard Shiff, for The Brooklyn Rail, 20th November 2024. Available at: https://youtu.be/NkSObntIRmI?si=V0T71bk62gWdBiD6 (Accessed 3rd December 2024)

Doig, P. (2024) Peter Doig at the Musée d’Orsay | HENI Talks, Musée d’Orsay, 21st March 2024. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QuZ_ffIaTX8 (Accessed: 27th July 2024)

Doig, P. (2017) Peter Doig in Conversation with Jasper Sharp Interviewed by J. Sharp for Kunst Histrorisches Museum Wien, 28th April 2017. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JBxtHgUHZws (Accessed: 28th June 2024)

Doig, P. (2013) Peter Doig | No Foreign Lands, The Scottish National Gallery, 9th August 2013. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_IKe529_2kM (Accessed: 11th October 2024)

Interviews: Hurvin Anderson

Anderson, H (2009) A Conversation between Hurvin Anderson and Thelma Golden Interview with Hurvin Anderson. Tate Britain, 3rd February 2009. Found in the archive at Tate Britain

Anderson, H. (2021) At home: Artist in Conversation | Hurvin Anderson Interviewed with M. Prokopow for Yale British Art, 11th June 2021. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dLxc4ZeLeqw (Accessed: 05th December 2024)

Anderson, H (2024) Hurvin Anderson in Conversation with Clarrie Wallis | Kistefos 2024 interview with Hurvin Anderson. Interviewed by Clarrie Wallis for the Kistefos Museum, 5th October 2024. Available at: https://www.kistefosmuseum.com/news/hurvinanderson-i-samtale-med-clarrie-wallis (Accessed: 3rd November 2024)

Anderson, H (2013) ‘Hurvin Anderson: reporting back’ Ikon Gallery, 17th October 2013. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5oZ2ObXvLtg (Accessed: 23rd September 2024)

Anderson, H (June 2024) Hurvin Anderson: Salon Paintings Exhibition/ Artist and Curator Interviews Interviewed with K. Smith Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cOuZbE6z5E (Accessed: 28th September 2024)

Anderson, H (2011) Hurvin Anderson in conversation with Matthew Higgs, in Hurvin Anderson: Subtitles, Michael Werner, New York (accessed: 4th January 2025).

Books:

Farquharson, A. and Bailey, D. (2021) Life between Islands: Caribbean-British Art. 1950s - now. London: Tate Publishing

Gayford, M. (2024) How Painting Happens (and Why it Matters) London: Thames and Husdon Ltd

Gawronski, A. (2019) Curated from Within: The Artist as Curator in B. Buckley and J. Conomos. (ed) A Companion to Curation Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Chapter 13

Hall, S (2017) Familiar Stranger: A life between two Islands. London: Allen Lane

Higgie, J. and Chambers, E. (2013) Hurvin Anderson: reporting back. Birmingham: Ikon Gallery

Jeffrey, C. (2015) The Artist as Curator Bristol: Intellect

Koegel, A. et al. (2000) Peter Doig: Studiofilmclub. Germany: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König

Kunsthalle zu Kiel. et al. (1998) Peter Doig: Blizzard Seventy-Seven. Germany. Kunsthalle zu Kiel et al.

Martin, C. and Lampert, M. and Robinson, R. (2022) Hurvin Anderson. New York: Rizzoli

International Publications

Nesbitt, J (2008) Peter Doig. London: Tate Publishing

Books (continued):

Prokopow, M (2021) Hurvin Anderson. London: Lund Humphries

Shiff, R and Lampert C (2016) Peter Doig. New York. Rizzoli International Publications

The Hepworth Wakefield. et al. (2023) Hurvin Anderson. London: The Hepworth Wakefield

The Courtauld Gallery (2023) Peter Doig. London: The Courtauld Gallery

Walcott, D. and Doig, P. (2016) Derek Walcott, Peter Doig: Morning, Paramin. London: Faber & Faber Ltd

Web Articles:

Batchelor, D (1996) Less is More Available at: https://www.frieze.com/article/less-more (Accessed: 17th July 2024)

Cumming, L (2021) Life Between Islands review- a mind-altering portrait of British Caribbean life through art Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/dec/05/life-between-islands-tatebritain-caribbean-british-art-1950s-to-now-review-a-crucial-mind-altering-show (Accessed: 15th August 2024)

Fox, D (2013) Being Curated Available at: https://www.frieze.com/article/being-

curated (Accessed: 27th June 2024)

Web Articles (continued):

Gawronski, A (2019) The Artist as Curator Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781119206880.ch13

(Accessed: 12th August 2024)

House of Lords Library Briefing (2019) Britain and the Transatlantic Slave Trade, Page 1.

Available at: https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/lln-20190104/ (Accessed: 03 September 20024)

Jeffries S. (2012) Peter Doig: the outsider comes home, The Guardian, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/sep/05/peter-doig-outsider-comeshome (accessed: 3rd January 2025)

Linklater, M (27th July 2013) ‘I do feel an outsider, but I’m Scottish,’ says Peter Doig

Available at: https://www.michaelwerner.com/news/i-do-feel-an-outsider-but-i-mscottish-says-peter-doig (Accessed: 10th September 2024)

Museums and Heritage Advisor (24th April 2024) 40th Anniversary Turner Prize shortlist announced Available at: https://museumsandheritage.com/advisor/posts/40thanniversary-turner-prize-shortlist-announced/ (Accessed: 10th September 2024)

Tomkins, C (2017) The Mythical Stories in Peter Doig’s Paintings

Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/12/11/the-mythical-storiesin-peter-doigs-paintings (Accessed: 15th September 2024)

Appendix:

I have included below three paintings that I also considered for this exhibition if space had allowed.

34

The painting is located at the main entrance to Hope Botanical Gardens in Jamaica. There’s a prevailing sense of uncertainty regarding what this painting conveys. Is it a foreboding or a welcoming place? The scale is vast, with trees reaching up and beyond the narrative of the artwork. The fortified red-brick wall evokes memories of Kew Gardens in London. The foliage is a dilute mixture of sap and phthalo green. Anderson manipulates the pigment to create drips which flood the foreground of this garden.

“Stencilled letters showing no concern for formal perspective spell out its ambiguous name/message: HOPE GARDENS and alert us to its colonial context. More wistfully, it does not indicate any clear future; instead, we are left in a situation that resides in an awkward state of uncertainty.” (Irving, 2013, P76)

Figure

Figure 35

This painting premiered at the Courtauld Gallery in London (2023). Shortly before the exhibition, Doig decided to add charcoal faces to the figures. The physical artwork has geographically drifted from Trinidad to London.

A fisherman's boat has been transformed into a musical composition. The word "Soca" is derived from (So)ul of (Ca)lypso, a popular music style that originated in Trinidad during the 1970s. The painting portrays a choppy, vibrant, and rugged sea, confidently preserving accidental elements. Doig would often use a “small hand plant sprayer –sometimes just with turpentine and linseed oil – to diffuse the paint”. (Shift, 2016, p343).

What was once a rain-damaged canvas, has been transformed into a stained, atmospheric, and fuming sky. “Whether it was in the dry season, or the rainy season, paint reacted differently there than it did here (London), which I quite liked… paintings would get wet from the rain and sometimes they would fade…in some of my paintings, I used these interventions.” (Doig, 2023)

The title is translated as Guest Stops on the Muldentalsperre, a phrase which strongly evokes German scenery. However, Doig’s painting has a theatrical and nocturnal quality that’s suggestive of something otherworldly. Doig explores this “tension between the often-generic representation of a pastoral scene and the investment in my own experiences of the landscape”.

(Doig, 2019)

Our eye is also drawn towards what appears to be two military figures. This painting conveys a playful exploration of disguise and identity. The figures are inspired by reference photos of Peter Doig and his friend dressed up for a fancy dress party. Doig’s narrative and location “Cannot be touched and rarely described”

(O’Hagan, 2013)