Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design University of Dundee

Title: In the Name of Art: an Analysis of the Ethics of Artistic Expression and its Tensions with Exploitation of Privacy

Author: Sophie Duncan

Publication Year/Date: May 2024

Document Version: Fine Art Hons dissertation

License:

DOI:

CC-BY-NC-ND

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/

https://doi.org/10.20933/100001303

Take down policy: If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim.

Abstract

This dissertation will analyse the growing contemporary concern for the ethics of artistic expression and its tensions with the exploitation of privacy. The objective of this investigation is toevaluatethemoral obligations ofcontemporaryartists andtheconstructive anddetrimental impacts of artistic expression on both a subject and a wider audience. This study examines the complexity of the debate and demonstrates the diverging consensus on what is a valid piece of work or an exploitation.

The first chapter investigates Sally Mann’s The Last Time Emmett Posed Nude (1987). I find that there is a strong correlation between controversial works and their ability to challenge inherited actualities. Confronted with vulnerability, an audience can discover within themselves their own boundaries which is pertinent for cultural growth. The second chapter reflects on the work of Heather Dewey-Hagborg. Her work Stranger Things (2012-2013) suggests that the evolving advancements in the modern digital age are dissolving calls for privacy. I analyse society’s ignorance to ethical violations in this age and find artists can provoke a re-examination of ignored elements of our shared culture that deserve our attention.

In chapter three, through research of Richard Prince’s Spiritual America (1983) I challenge censorship as a means of protection against an artist exploiting a subject. Censorship of artistic expression can brand certain subjects as inherently bad and there is damage in this. Ultimately, acknowledging the unstable, shifting boundaries of our society, I argue the importance of accountability and the responsibility of the spectator.

Acknowledgements

A big thank you to Sandra Plummer for her support and guidance.

Also, to Imogen Findlay, for her constant wisdom and always double-checking my referencing.

I would also like to acknowledge the invaluable emotional support of my family and boyfriend who have always believed in me.

List of Illustrations

Figures Page

Fig 1. 10

Sally Mann (1987), The Last Time Emmet Posed Nude, 50 × 60 cm, Gelatin silver print, image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art America.

Fig 2. 17

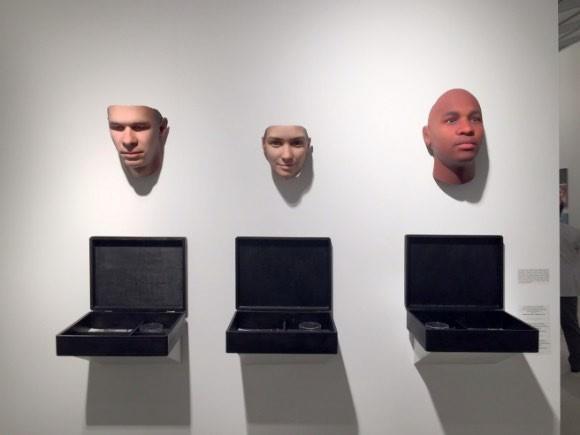

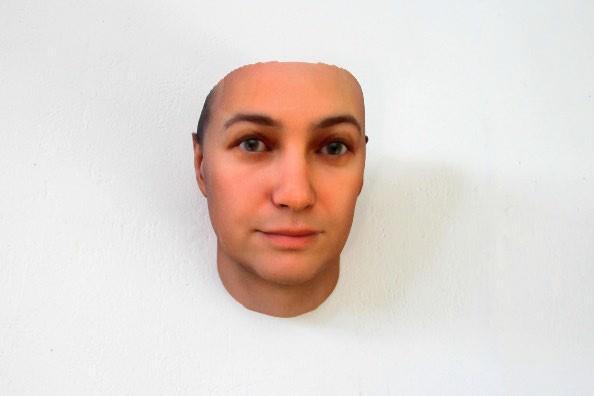

Heather Dewey-Hagborg (2012-2013), Stranger Visions,

304.8 × 304.8 × 20.3 cm, custom software, 3D printed portraits, found genetic materials, documentation, images courtesy of Heather Dewey-Hagborg and the Fridman Gallery America.

Fig. 3 24

Richard Prince (1983), Spiritual America,

60.9 x 50.8 cm, Chromogenic print, images courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Introduction

This dissertation examines the growing contemporary concern about the ethics of artistic expression and its tensions with the exploitation of privacy. Through critical reflection of appropriate works by Sally Mann (1987), Heather Dewey-Hagborg (2012-2013), and Richard Prince (1983), this research intends to analyse both the constructive and detrimental impacts of artistic expression, with particular regard to a subject's privacy and the way it can be exploited in the public and private realm. There is a specific focus on the moral obligations of artists and their conduct in these spaces breeding fears over ownership, identity, prospect for cultural growth, and harmful influence over a wider audience. I will discuss how artists use controversial subject matter and methods to communicate with an audience and examine the importance of making such a decision. However, at the same time, evaluating the ethical anxieties of the public and the validity of a call for protection from an artist. To produce a comprehensive analysis, I will investigate this subject by considering multiple voices of lawyers, critics, professors, theorists, historians, and philosophers who impart insight into this area. For example, Gaston Bachelard, Shoshana Zuboff, Anthony Julius, Michel Foucault, Alan Westin, Andrea Mubi Brighenti and Plato. To further my research, I have reflected on academic journals, scientific papers, and legal case studies to contribute a variety of evidence from different disciplines. This area of research is pertinent to my creative practice as my current objective is to delve into exposing blind faith in the artist and strangers, critically reflecting upon society's ignorance of violations. This research is relevant due to the modern predicament of exploitation in the age of technology and social media. There is a dissolution of personal boundaries that birthed a call for determining the extent to which personal information and identity are consumed. Furthermore, there is a perpetual criticism of the validity of artistic practices in society today, with an increase in legal cases and censorship, resulting in significant influence over creative expression. However, there is still no general

mandate for works, and this leaves the artist in a state of confusion. This study is necessary to consider what elements society and critics strongly dictate as worthy of protection.

There are three chapters featured in this dissertation. Chapter one will begin with Sally Mann’s The Last Time Emmet Posed Nude (1987) and will establish her controversial methodology and motivations for the work. I will then focus on her memoir and contemplate the ethical relationship between artist and subject, introducing the key power dynamics that are crucial to the discussion on respect for privacy. I will additionally introduce the context of space in this argument, a private boundary of a home, and offer a theoretical analysis of the safety this represents. Finally, chapter one will start to acknowledge the nature of true representation in art, in relation to public perception and the opposing reactions and critical defences. Furthermore, in chapter two, Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s Stranger Visions (2012-2013) will again commence with an introduction to her key objectives and practical approaches. I will explore the modern digital age of constant surveillance in the public sphere, followed by a reflection on the contradiction of expecting privacy in this sphere. I will then show how the artist’s methods can be linked to a commentary on the passivity of society to exploitation. The chapter will ultimately examine the vulnerability of identity and the unconsidered ethical violations already occurring at present and the laws that facilitate this. Chapter three, Richard Prince’s Spiritual America (1983),willinitiallydiscusstheartist’sworkandtheseriesofevents that preceded and followed its creation. There will be a discussion of the public consumption of art and the role that this can play in exploiting a subject. I will further examine the subject of censorship, at one point in context to a previous prominent artwork, as a protective defence, with a comparison of historical philosophy to contemporary critics in the subject area. I set out to analyse the harmful possibilities of art and the relevancy of an artist’s moral obligations.

This dissertation will produce an informed analysis of the diverging consensus on what can be considered a violation or a valid work.

Sally Mann The Last Time Emmet Posed Nude (1987)

American Sally Mann, born in 1951, is an artist widely acknowledged for her photography. Her body of work is made up of photographs and subsequently published books that are critically acclaimed and recognised internationally (artnet,2023). Mann intentionally uses an antique large format camera with an 8x10 view to capture her subjects, embracing stunning detail in her images (Savage, 2017). She concentrates on the complex realities of social and familial relationships. In addition, she contemplates the connection between memory, nature, and history (Mann, 2015). Her practice, despite winning numerous awards, is often discussed with criticism due to its controversy, with particular regard to her children as the subjects (Appleford, 2010).

In 1992 Mann published a book titled Immediate Family. In the tranquil backdrop of the southern landscape of Virginia, she depicts spectacular images of her children in private moments at their summer home. In this collection of 65 duotone images, the story of intimacy, childhood innocence, weakness, and fragility is told (Nightingale, 2014). Mann dives into not only the triumphs but also the hardships, for example documenting injuries, wet beds, and vomit (Mann, 2015). A realm of private familial interaction between mother and children is eternalised in film. However, this interaction is often cited as almost “unbearably intimate” (Williams, 2020). The role of a mother creates an unmistakable quality to the poignant photographs with what can only be described as an ardour of love (Nightingale, 2014). The children are frozen in their youthful antics, often in states of undress, and are repeatedly posed in mimicries of adulthood. Mann’s photographs evoke the “profound cultural fantasies of an innocent, ‘natural’ childhood.” (Hirsch, 1997, p.152). With this offer of innocence comes the risk of exploitation.

At an initial glance, one would assume Mann’s photographs are taken in the decisive moment, similar to street photography. However, her memoir Hold Still (2015) reveals the staging of her images, with the artist directing her children into these scenarios. They are not accurate representations, but recreations of the feelings experienced when witnessing her child naturally exploring their home (Mann, 2015). The Last Time Emmet Posed Nude illustrates how the roles of mother and artist can become blurred. Mann became obsessed with the perfect image, shooting over seven to eight days, continuously critiquing her son Emmet as he posed in a

freezing lake. Consequentially, this laborious process resulted in his refusal to pose again for his mother (Mann, 2015). In the final photograph, Mann captured Emmet waist-deep stepping through seemingly glossy dark water. The viewer is confronted with the vulnerability of a young naked boy, surrounded by ominous dark shadows. Yet it is clear Emmet is not fearful, he is in mid-stride towards the camera. His mouth set in a harsh line and a striking ferocity in his eyes. There is a clear defiance against his mother and the harsh conditions that he has been repeatedly subjected to. Furthermore, his hands sit gently but confidently on the surface of the water, fingers splayed ready to emerge from the river, another indication that Emmet was not comfortable continuing further (Crapo, 2015). Ethically, the mother is no longer doing the expected, taking care of the child in moments of intimacy or distress but willingly using them, even repeating the difficult moment over. Therefore, predictably, Mann’s work is regarded with apprehension (Savage, 2017). Ultimately, it is a privileged intrusion against the children, where the viewer is left questioning the morality of witnessing it. When reflecting on the increasing anxieties regarding the exploitation of her children she defends that “children cannot be forced to take pictures like these: mine gave them to me. Every picture represents a gesture of such generosity, and faith that I, in turn, felt obliged to repay them by making the best, most enduring images that I could….in many cases, they did this while hot, hungry, tired, or like Emmet, shaking with cold.” (Mann, 2015, p.126).

Privacy In the Private Sphere

It is integral in the discourse of privacy to analyse the topic in the context of space. There are increasing concerns over artists violating personal boundaries. Mann’s photographs are taken in the private boundary of a home, a trusted space. Furthermore, from the trusted role of a parent (Parsons, 2008). This exemplifies the power dynamic of artist vs subject and parent vs

child. It is the same, ultimately, the reasonable or unreasonable expectation of respect. Mann clarifies the importance of her home as a setting: “Within the sweet insularity of its boundaries

I still find my equilibrium” (2015, p. 99). It is “protected by distance, time, and our belief that the world was a safe space” (2015, p.161). Albeit what may be a naïve belief about the world, Mann’s home allowed for such a resonant expression of childhood purity. The profound nature of the home as a sacred space is expanded on by Gaston Bachelard, a professor of philosophy at the Sorbonne University. In his book The Poetics of Space (1994), he introduces a theory called “topoanalysis” which is the study of how we experience space, specifically the home. It centres around the deep relations we form with our inner self and the outer world through this space (Bachelard, 1994). Bachelard emphasises “The house is one of the greatest powers of integration for the thoughts, memories, and dreams of mankind…It is body and soul. It is the human being’s first world. Before he is ‘cast into the world’, …man is laid in the cradle of the house…Life begins well, it begins enclosed, protected, all warm in the bosom of the house…”.

(Bachelard, 1994, p.7) He acknowledges the concept of the hunter and the hunted has always existed and suggests this need for a safe refuge, pleasures us primally. The ubiquitous influence of hiding from the outside world activates within us feelings of safety and opens new possibilities of wonder and adventure. From this privacy, there evolves a sense of learning about your own identity in the self and the other (Bachelard, 1994). American author and professor, Shoshana Zuboff, in her work The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2019, p 477) further advances this theory: “Home is our school of intimacy, where we first learn to be human…It’s shelter, stability, and security work to concentrate our unique inner sense of self.” It suggests the influence a secure space can have on the development of self, a learning device that realises the way we experience home and universe, refuge and world, and private and public. It sustains us.

Indeed, Mann utilises the power a safe space can provide as a tool for artistic expression. Her intention was ephemeral moments, meant to be viewed in isolation from the outside world and its preconceptions (Mann, 2015).

Public Consumption

Through the process of her work set in a home space, Mann is exposing a private existence for public scrutiny. The sanctity of her home, and her children’s actions in said home, are exposed for public consumption. The images are re-circulated, not just in the contemporary art world, but through gallery exhibitions, printed books, and digital media (Parsons, 2008). As a result, the morality of this is therefore questioned, can it be considered a violation? It can be deduced that the violation amplifies Mann’s message: this is what already exists, innocence is real and pure. Aresponsibilityis placedonthespectatorto assess thedangeroflabelling certain subjects as inherently wrong, such as the child nude. Generally, the artist and their subjects follow Bachelard’s primal concept of hunter and hunted. There is a danger surrounding this and consequently, fears of exploitation. Mann later confessed that her children’s permission was acquired once they reached a certain age, and they had full censorship over what they wanted to make public (Mann,2015). However, does this equivalate to the initial act being any more ethically sound? Is it no longer an exploitation of trust? Once an artist publishes the images, it is out of their control what reaction the public has and how they consume the image. The power is with the viewer. Despite her motherly identity of protection, the artist has to become morally indifferent to this and must sacrifice her work, her children, and her sanctity.

The Taboo and Protection of Children

There is an inviolable rule regarding children. An injury or injustice against a child holds greater weight in a court of law. Childhood encompasses vulnerability, dependency and fragility that must not be violated. Art advocates and adversaries can acknowledge the taboo of using children and their innocence to create art (Julius, 2002). The uproar from critics of Immediate Family put weight on the uncensored nudity of the children as an exploitation. The religious organisation ‘Save the Children’ even organised a book burning (Parsons, 2008). The concept of an artist and the obligations of their vocation being superior to their morality is well argued. An obligation of respect is expected, but not mandated. There, is a continuous confusion over the implementation of limits of such artistic expressions. Ones that offend, or cause injury, or that resist societal boundaries (Julius, 2002). Michel Foucault specifies “criticismindeedconsistsofanalysingandreflectinguponlimits”(1984,p.45).Fromaprocess ofdoingsomethingsocietyconsidersunethicalorimmoral,anewrulecanemerge,illuminating the need to disregard the past rule. With contemporary audiences, it can be argued there is a certain significance in dislodging complacencies for cultural growth (Zuboff, 2019). This theory is further lamented by lawyer and lecturer, Anthony Julius. His book Transgressions, The Offences of Art (2002) dissects the question of censorship in art. In reference to the protection of art practices, he lists a set of defence systems. His “Estrangement defence” outlines how art can transform preconceptions, turning the unchallenged problematic and the familiar into something strange (Julius, 2002, p.26). Opposition can amplify the meaning of a work. In our reaction to something disagreeable, we discover in ourselves our own boundaries. There is a call for challenging the spectator, embracing resistance as a tool for necessary selfexploration and confrontation of inherited actualities. A ‘transgression’ involving a child has aesthetic potential for this (Julius, 2002). In this instance, it can expose deep feelings when contemplating childhood. Manns’s work aggravates our awareness that we would rather overlook due to the initial discomfort. The question then evolves is this nudity exploitation or

innocence expressed through art? Sally Mann counters in her memoir “An artist’s job is to make the commonplace singular, to project a different interpretation onto the conventional… some below the surface cultural unease about what it is to be a child, bringing the dialogue of innocence and threat and fear and sensuality and calling attention to the limitations of widely held views on childhood” (2015, p. 153). She summarises, “childhood sexuality is an oxymoron” and her morality should not be considered a factor (2015, p. 158). It can therefore be deduced that artworks can demonstrate how our preconceptions are supposedly wrong and should always be questioned. In this case, Sally Mann offers a new interpretation: the children are as innocent as you would be inclined to believe. They are representations detached from the regular conventions of the world and its opinions, giving a pure and resonant image. The spectator experiences her images afresh, a glimpse into the shelter of a free utopian life of a child.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg Stranger Visions (2012-2013)

Heather Dewey-Hagborg is an American information artist, activist, and biohacker. Born in 1982, her research specialises in technological critiques that expose societally ingrained issues surrounding privacy and exploitation. Dewey-Hagborg has a particular interest in the interaction between art and science concerning its laws, limitations, andbiases. Thereis afocus on the authoritative use of these technologies for criminal investigations and the faults that can arise from this (Wolthers, 2016). She mainly works in public spaces, investigating and reflecting upon shifting relationships between digital technologies, DNA, and evidence. Dewey-Hagborg is commonly cited as ‘controversial’ due to her means of data collection (Bright, 2020). Her methods involve gathering genetic ‘artifacts’ left behind by strangers in publicspaces.Shemaintains that in this developing society “thevery things that makeus human: hair, skin, saliva, become a liability … leaving artifacts which anyone could come along and mine for information." (Dewey-Hagborg, 2016, p. 2). The central thesis enveloping her practice is the unconsidered surrender of our individual genetic privacy, in a modern world where it is more convenient to do so (Wolthers, 2016). It is pertinent to evaluate society’s progression towards a complete dissolution of privacy in public spaces. The continuous advancements in new surveillance technologies threaten to emancipate us from ownership over our image and thus our identity (Dewey-Hagborg, 2019). Artists can engage with this threat and provoke a social commentary on this dissolution, illuminating the systems and laws in place that facilitate it. Dewey-Hagborg directly challenges the relationship of trust between artist and stranger but more importantly, anyone and everyone. What is considered an exploitation of privacy by an artist can highlight the very exploitation already apparent in these public settings (Trembley, 2015).

materials, documentation, images courtesy of Heather Dewey-Hagborg and the Fridman Gallery America.

From 2012 to 2013, Dewey-Hagborg created a series titled Stranger Visions. A wall of 3D printed, life-size, colour portraits of strangers from the neck up. Collecting materials such as cigarette butts and fingernails off the street, in public bathrooms, and waiting rooms, DeweyHagborg extracted DNA residue and constructed highly detailed profiles of the strangers based on traces inadvertently left behind (Dewey-Hagborg, 2016). Her investigative methods could be compared to that of a criminal forensic analyst; equipped with sealable plastic bags, tweezers,andacamera, shecould analyseasample. Dewey-Hagborg documentedthematerials in their original location and then placed them into individual bags for testing. Each sample

was amenable to a specific process and treated with a sequence of enzymes and primers to expand on the DNA. The procedure could extract detectable physical traits by isolating different locations on the genome, these are known as phenotypes (Steinberg, 2022). Through face-generating software, she then 3D-printed individual masks. Nevertheless, they are not a precise reconstruction but rather a technological approximation (Goodyear, 2020). The portraits aremounted on awall and accompanied bygriddedblackboxes exhibiting theoriginal specimens in Petri dishes, their sample number, location, and photograph in situ. Additionally, followed by short phenotype descriptions (ethnicity, gender, eye colour). The faces of these innocent strangers are stuck in expressions of relaxed passivity, unaware of the way their private details are being exploited. The portraits can be compared to mounted animal heads, displayed like trophies on a wall. An exercise of power over society. In haunting representations of breaches of privacy, the faces confront the viewer with their innocence and vulnerability. The spectator is left questioning the growing mutability of surveillance technologies, with new processes of bio-surveillance that threaten our very human existence (Trembley, 2015).

The Modern Digital Age of Surveillance

In a study on the rapid growth of surveillance systems for Urban Eye, it was estimated that in 2002 there were approximately 4.2 million CCTV cameras deployed in the UK (McCahill and Norris, 2002, p.20). Since then, numbers have substantially increased, with research indicating around 7 million reported in 2022 (Calipsa, 2022). Furthermore, we coexist, surveilled by each other (often referred to as multiveillance) (Wolthers, 2016). It would be incorrect to define society as passive spectators, on the contrary, we are active participants (Richards, 2013). These surveillance infrastructures are a modality in contemporary society and are

subconsciously accepted without much hesitation (Holert, 2016). They are an omnipresent threat with newtechnological advances such as biometric sensors, RFID tag readers, and object detection. Theadvances praised fortheir ability toprotect societyfrom criminal violations have subsequently crossed boundaries in the protection of our sense of private existence. Computer algorithms are flagging behaviours, faces, and objects of interest automatically, building up profiles forpossible alerts. Ourcultureaccepts thetechnological gazeduetoits so-called ability to be an objective witness. However, this is now not the case, and as such the dichotomy between public and private has dissolved (Senior, 2009). There is an ever-increasing interconnectedness, yet the anxiety remains; how do we protect our privacy? Stranger Visions disproves the objective gaze of technology; it is a provocative work that demonstrates privacy is no longer a rule but an impossible privilege. Even an amateur, such as Dewey-Hagborg, has the power to exploit a stranger’s information from debris discarded in public. Despite the criminal connotations associated with forensic techniques, the only crime these strangers committed was to exist in public spaces. Therefore, the question remains of what gave someone the right to do this, is there no protection for the individual from the exploitation of privacy? The Abandoned DNA Act

It is important to discuss the legality of this mode of data collection in the public sphere. Since Dewy-Hagborg gathered samples that were deserted by their owners, these materials are considered “abandoned DNA” under the law. Abandoned DNA is defined as “any amount of human tissue capable of DNA analysis and separated from a targeted individual’s person inadvertently or involuntarily, but not by police coercion.” (Joh, 2006, p. 859). This is separate from the retrieval of samples being obtained through force (such as drawing blood), or by

consent (for criminal exoneration) (Joh, 2006). U.S. Supreme Court Case Greenwood v. California (1988) established that the Fourth Amendment allows rubbish to be seized without consent or a legal warrant. In the United States, by law, this knowing disregard for private DNA is comparable to abandoned property or rubbish and as such allows for no additional protection from law enforcement, a corporation, nor the random individual (Tunick, 2000). This law lays emphasis on the public setting, this disregard of genetic DNA is grounded in physical boundaries. If remnants of rubbish harbouring DNA are intentionally deposited in a public place, it exists outside of the sphere of our body and has been intentionally exposed. Anyone’s identity is up for grabs and genetic privacy is unprotected (Joh, 2006). This easily enhances anyone’s ability to collect and own individual genetic information, without any objection or resistance. Dewey-Hagborg used this legal rationale to collect her strangers’ samples but what would be the cost if implemented by someone not so concerned with ethical boundaries? There are no criminal laws condemning Dewey-Hagborg and her controversial methods, so what remains is fear of exploitation by anyone and everyone. It is thus important to take into consideration the ethical concerns of the government, authorities, and the strangers we pass by every day.

The Vulnerability of Identity in A Surveillance Society

No one can elude these modern systems of surveillance and remain invisible, what emerges is an understanding, a realisation of the hierarchies that apply to law enforcement agencies and private corporations that conduct such surveillance in public places. Surveillance as a modality of power over society is famously theorised by French Philosopher Michel Foucault. In his 1975 book Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Foucault revitalises Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon as a means of discipline. As a piece of architecture, the panopticon exercises a principle of constant observation: with the implementation of a hidden “supervisor”,

an occupant is watched without knowing exactly when they are being looked at (Foucault, 1975, p. 200). Therefore, the anxiety of conscious and permanent visibility directly influences the occupant to modify their behaviours and discipline themselves. Foucault states “He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; he makes them play spontaneously upon himself; he inscribes in himself the power relation in which he simultaneously plays both roles; he becomes the principle of his own subjection.” (1975, p. 202). It was theorised to guarantee order in society these surveillance infrastructures must be in place. The panoptic principles can be found in contemporary CCTV systems with amechanical gazeofcameras as constant anonymous observers ofourbehaviours (Norris and McCahill 2006). Artists, likeDewey-Hagborg, can offer a critical engagement with contemporary surveillance complexes and expose the concealed visual exercises of power in our modern world. By intervening artists carry out acts of ‘sous-veillance’ (turning the tables and looking back at those operating surveillance from below) (Wolthers, 2016, p.8). DeweyHagborg conducts her own surveillance and takes on the role of the observer, directly exposing the dissolution of privacy in public spaces. Andrea Mubi Brighenti praises art’s ability to contribute to surveillance studies as an “ideoscape & collective imagery about what security, insecurity, and control are ultimately about, as well as the landscapes of mood and affects a surveillance society like ours expresses” (Brighenti, 2010, p.1). It is both human and machine watching that has led to a lack of trust and fears of exploitation (Senior, 2009). It is evident that we do not have ownership over our identity in shared spaces. Consequently, the call for defining privacy against an artist in a public realm is almost insignificant. What could be considered as unethical breaches of trust by an artist, is actually a demonstration of preexisting hierarchies and violations often undisclosed by an authoritarian system. Through art practices, this can be made transparent and thus be made amenable to critique and challenge. The questionable ethics are acknowledged by the artist herself, when interviewed by ‘Adjacent’ in

2019, she distinguishes “I wasn’t using the genetic information in a dangerous way. This was an artwork that shed light on these technologies and on the vulnerability of identity. That is, the fact that someone could use the information in an unethical way” (Dewey-Hagborg, 2019).

Privacy in the Public Sphere

Alan Westin, a lawyer, and political scientist emphasises that anonymity in a public space is an essential state of privacy. Westin’s 1967 book Privacy and Freedom states “Knowledge or fear that one is under systematic observation in public places destroys the sense of relaxation or freedom that men seek in open spaces and public arenas.” (Westin, 1967, p. 34). As previously distinguished in this study, our assumption of privacy varies depending on space. One expects a greater degree of privacy in one’s private home than the street. Nevertheless, the desire for respect remains, a sanctuary in public places. Shoshana Zuboff highlights that the demise of the ‘sanctuary privilege’ is a direct result of the modern era with the evolution of technology and social culture. The divide between public and private ceases to exist and there is no more need for Bachelard’s “topoanalysis” (Zuboff, 2019, p. 488). There is an eradication of hiding places that threaten our society’s need for privacy. Zuboff warns “each deletion of the possibility of sanctuary leaves a void that is seamlessly and soundlessly filled by the new conditions of instrumentarian power.” (Zuboff, 2019, p. 492). She exaggerates that our greatest threat is a surveyed world of constantly unstable, shifting boundaries and the danger is becoming numb to the powers that shape our society and existing comfortably in ignorance (Zuboff, 2019) An emerging concept in this dissertation is a call for responsibility of the spectator. It can be concluded the violation committed against the strangers in Stranger Visions is that of necessity a fight against ignorance in a world that is constantly changing.

Richard Prince Spiritual America (1983)

Richard Prince is an American photographer and painter born in 1949, greatly renowned for his appropriation art. Appropriation art can be defined as “the act of borrowing or reusing existing elements within a new work” (Rowe, 2011, p.1). This reappropriation steals an image from its original context and opens it up to a new perspective. The spectator is faced with more relevant or current interpretations (Prince, 2023). Richard Prince surfaced within the first surge of postmodernist photography in the late 1970s and is widely known for his appropriation technique of ‘rephotographing’ media, commonly derived from American culture such as advertisements and entertainment. This allows for impressive new definitions of authorship and representation in art (Tan, 2013). His signature obsession with storytelling, fantasy, and popular imagery is described as “witty, deft and subversive” (Cotton, 2004, p. 209). This devotion to the fictitious nature of authorship in the arts enlightens the growing contemporary issue of censorship. There is significance in analysing censorship as a means of protection against exploitation. In this ethical debate on artistic expression, Richard Prince offers insight into the public consumption of art and provokes discussion of appropriation art as an important means of reflection or a violation of someone’s privacy. I have found there is a considerable debate on the merit of re-used or mimetic imagery, as an art form worth validation, in philosophy and art practices. Especially imagery that has a possibility for harm,

American Art. In 1983, Prince ‘rephotographed’ a pre-existing image of famous actress Brooke Shields and titled it Spiritual America. The original image was taken by Gary Gross and depicts Shields as a ten-year-old child in a state of complete nudity. The initial photograph was first published for Gross’s series The Woman in the Child (1975) and Little Women (1975). However, it was later published in the Playboy magazine Sugar n’ Spice (1976) (Evans, 2015, p.144). The work exemplified the issue of exploitation of children for artistic purposes, especially in the nude, and whether a child was mentally mature enough to consent and understand the ramifications oftheiractions (Isaacs, Isaacs, 2010).OnceShield’s reached adulthood sheattempted to retract

the original image by Gross from the public sphere. Through legal action, she tried to purchase the rights to the negatives but was unsuccessful. Consequently, Prince was able to reproduce and reframe Gross’s photograph and display it in the Guggenheim Museum, without objection (Deitcher, 2004). Spiritual America was publicly exhibited in multiple countries before facing legal problems in the UK. The work was featured in the 2009 Tate Exhibition ‘Pop Life: Art in a Material World’. However, it received intense reactions from the media and resulted in the Metropolitan Police Service forcing the gallery to remove it from public display (Farrington, 2015). More recently, the work was posted on Instagram by Prince but was taken down by monitors as not complying with their guidelines (Swanson, 2014). The Ethics of Re-Exhibition to a Public Sphere

Spiritual America depicts Shields as a young child frozen with arms open, inviting the viewer to witnessherbody. Thereis no discomfort in herexpression, ratherhergaze is inconfrontation with the camera – an attempt at alluring. Furthermore, her face is heavy with cosmetics and her body appears to be greased up and posed sensuously (Turner, 2009). There is a contradiction between the extreme pornographic nature of the image and the extremely young Shields. The image has a disturbing quality due to its falsehood; Shields was a child, not capable of such an adult sexual presentation (Snow, 2020). In an interview with BOMB Magazine (1988), Prince alludes to this fictitious condition: “I seem to go after images that I don’t quite believe. And I try to re-present them even more unbelievably. If there’s any one thing going on through these images, it’s that I as an audience don’t believe them.” (Prince, 1988, p.1). It is key to highlight the re-exhibition of the work in this ethical debate. Prince’s re-exhibition of the image could be considered as an exploitation with Shields once again becoming a possible victim. Prince deliberately gave the piece an extravagant gold frame and exhibited it in a public gallery. In

addition, the audience is implicated as bystanders in this possible exploitation by witnessing the image (Cejudo,2021). Mihail Evans argues this was a commentary on society’s passivity. Evans implies that the act of re-framing brings the image back into circulation and demands “that we give serious consideration to elements of our culture that are not normally displayed for our attention.” (2015, p. 149). One could suggest that its re-exhibition explicitly orders us to reexamine the original photograph and methods by Gross at a different time. Spiritual America acts as an ethical tool toinduce a response from the spectator. As previously discussed in this dissertation, artists use controversial or morally questionable subject matter to challenge a spectator and their boundaries. In Spiritual America, we are encountered with a sense of responsibility for an injustice committed in the past, an opportunity to reflect on the nature of the society we live in. Therefore, the reoccurring censorship of Spiritual America has been criticised as “irresponsible” (Evans, 2015, p.151). Evans stresses this censorship dissolves any chance the individual may have to respond to cultural issues for societal development (Evans, 2015).

Censorship

When contemplating the origins of censorship in the arts it is key to reflect on the writings of Plato, especially his work The Republic. Plato is commonly referred to as the first Western censor of art and philosophised an idealistic vision of art, that impacts positively on morality, education, and politics. The Republic offers a comprehensive narrative of a system of censorship, with particular regard to the morality and immorality of the arts. He wrote passionately about both thedistrust and beauty of art,with recognition and respect ofits powers and subsequent fears of said powers (Allen, 2002). To Plato, censorship prevents artists “from portraying bad character, ill-discipline, meanness, or ugliness” (Plato, 1974, 111, 401B). He

mandates that artists can only produce a reproduction of a living thing, an imitation. They fall short in their attempt to depict a true reality and instead produce a mimicry of reality. However, this deception is harmful to society and can consequently modify our behaviours. Plato feared art’s potential to corrupt a spectator and further claimed if an artwork has immoral content, then society will be influenced to be immoral. Limitless expression in the arts would open society up to this very corruption. Art, therefore, should be strictly censored due to its persuasive nature (Allen, 2002). Contemporary art and morality continue to be just as intrinsically linked. Critics today are still concerned with the influential power of art on our behaviours. Nevertheless, the complexity of the argument is both freedom of expression and censorship are restricted in practice (Cejudo,2021). Censorship in the arts is not universally accepted as valid (Kayahan Dal, 2022).

The censorship of Spiritual America concentrates on the exploitation of a naked child and whether it can be considered child pornography that would cause harm to a spectator. Professor David Isaacs and Thomas G Isaacs (2010) acknowledge the persuasive nature of art: “The moral prohibition against public nudity is reflected commonly inlegislation, with the presumed intention not only of being explicit about and preserving societal values, but also of protecting theinnocent against ‘corruption’.”(Isaacs and Isaacs, 2010,p.369). However, Isaacs and Isaacs argue that such extreme censorship of art is irresponsible. They clarify the depiction of children in art, especially portrayed in sexual positions or acts, has no clear restrictions in the modern age. Concerning examples including Spiritual America, Isaacs and Isaacs stress fear of corruption by pornographic material is not a reasonable excuse for censoring artworks. Adults should be given the freedom to choose whether they expose themselves to such controversial works and should have the competency and maturity levels to not let themselves be manipulated. Furthermore, Isaacs and Isaacs question whether censorship is a protection of childhood innocence or a means of getting rid of it. Through the implementation of censorship,

the naked child (which is common practice in the contemporary familial home) is transformed into an existence that is strictly wrong and shameful (Isaacs and Isaacs, 2010). Spiritual America’s censorship demonstrates the issues surrounding the public consumption of what can be considered unethical or morally questionable subject matter in art. Censorships’ persuasive nature can brand certain subjects as wrong but there is damage in this to the evolution of our culture. The supposed protective defence has its own detrimental impact.

A further example of censorship in art is Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ (1987). The work is a 60 x 40-inch Cibachrome print of a plastic model of Christ on a cross. The model is immersed in a jar filled with a combination of cow blood and the artist’s urine (Lippard, 2023). Predictably this provoked severe uproar from the public, especially the Christian community (Casey, 2000). In a similar response to Spiritual America, it faced severe resistance at its public display concerning its possibility of a harmful effect. Despite being accepted at certain galleries, Piss Christ faced threats of censorship in 1989. This was spearheaded by Senator Jesse Helms, and Senator Alphonse D’Amato but ultimately failed (Phelan, 1990). In addition, it faced a physical attack in France in 2011. Serrano, as a Christian, defends his work as a truer depiction of the crucifixion of Christ: being impaled and left for dead, unable to take care of his bodily excretions (Holpuch,2012). Serrano sees beauty in these fluids which is his way of honouring the life and sacrifice of Christ (Casey, 2000). Like Prince, Serrano is offering a darker truth to a past image. In this case, the iconography of Christ is reframed with a different kind of commemoration. In unison, these examples provoke discussion on the public reception of art with both facing calls for censorship.

The Moral Obligation of the Artist

It is apparent censorship in the arts is difficult to mandate with the subjectivity of what offends an audience being dependent on cultural and societal variations. There are diverging opinions on topics such as nudity and religion, with constantly shifting developments as the years go on.

What was once unacceptable can become accepted (Kayahan Dal, 2022). Consequently, the moral obligation of an artist is hard to determine. With such instability, it can be argued that thereis valuein challenging anaudience’ssensibilities (Julius, 2002). Definitively condemning an artwork based on its controversial subject matter could be misguided. The future of how morally questionable artworks are consumed and critiqued is unpredictable and subject to change. It is, therefore, important to grasp the complexity of the issue and constantly reevaluate criticisms as society evolves.

Conclusion

This dissertation set out to analyse the ethics of artistic expression and its tensions with exploitation of privacy. Generally, there is a high value placed on the protection of privacy in contemporary society, with widely held fears regarding the disrespect of this principle. Privacy can activate feelings of safety and comfort, influencing the development of self-exploration and our identity in relation to others. The growing concern of the exploitation of this valued principle is therefore an important issue. As highlighted in this study, contemporary artists can interact with this concept and offer new interpretations. They produce controversial works that allow for ethical criticisms and grant deeper reflections on the continuous evolution of our shared culture. Therefore, exposing exactly how formidable artistic practice is to define as inherently right or wrong.

Through examination of innocence, space, evolving technology, identity, and censorship, this dissertation has provoked a deeper contemplation of what we perceive as an exploitation of privacy. Collectively all three artists and their respective works discussed in this dissertation use controversial subject matter and methodology that could be considered a violation against a subject. Sally Mann blurs the line between artist and mother, exposing her children and their innocence in their family home. Heather Dewey-Hagborg uses strangers and their abandoned DNA in public spaces, and Richard Prince recirculates an unethical pre-existing image of celebrity Brooke Shields. This study has identified the use of exploitation in art can amplify the meaning of a work. Artworks that offend, cause harm or defy societal boundaries can directly aggravate our awareness. From this process of doing something society considers unethical or immoral, an artist’s message is amplified. A common factor in all three artists’ work is they expose a subject and their vulnerability for public consumption. In committing controversial acts, they re-examine this vulnerability and alter a spectator’s opinion on a

conventionally accepted truth. Mann illuminates the purity of childhood innocence and demonstrates the danger of labelling a subject as wrong. Dewey-Hagborg committed a controversial act against strangers to expose the dissolution of privacy in the modern age of technology. Finally, Prince exhibits an unethical image to confront a spectator’s ignorance and question our accountability. By embracing resistance as a reflective tool, these artists allow a more relevant or current interpretation. A significant finding that emerges from this study is that bychallenging ourinheritedinteractions with taboosubjects, wegiveserious consideration to elements of our culture that are often unconsidered or undisclosed. Mann, Dewey-Hagborg and Princecall forthe responsibilityofthespectator.Wemust takeaccountability forthenature of the society we live in. A fight against passivity in a continuously evolving society.

The question raised in the dissertation is whether there is a conclusive mandate for what can be considered an exploitation of privacy or a valid piece of artistic expression. The diverging opinions of lawyers, critics, authors, and theorists demonstrate that the subjectivity of what offends an audience can alter alongside societal and cultural developments. Consequently, an artist’s moral obligation is difficult to determine. Through critical reflection, one can conclude that we exist in a world of constantly shifting, unstable boundaries where it is seemingly impossible to define what offends and what doesn’t. As time goes by, what was once unaccepted can become accepted. Overall, this study strengthens the idea that it is potentially more pertinent to continuously re-evaluate and make new judgments when faced with such instability. This study adds to the growing body of research on the evolution of ethical criticism of artistic expression. Due to the unpredictability of societal developments, this is a subject area that will need to be revisited. In the future, continued efforts are needed to further the discussion on the progression of what is acceptable or not in artistic practices.

Bibliography

Allen, J, S. (2002) ‘Plato: The Morality and Immorality of Art’, Arts Education Policy Review, 104:2, pp. 19-24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10632910209605999 (Accessed: 16/10/23)

Appleford, S. (December 4, 2010) "Sally Mann’s examination of life, death and decay", Los Angeles Times, 4 December. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2010dec-05-la-ca-1205-sally-mann-20101205-story.html (Accessed: 2/10/23).

artnet (2023) Sally Mann Available at: https://www.artnet.com/artists/sally-mann/biography (Accessed: 2/10/23).

Bachelard, G. (1994) The Poetics of Space. New York: Beacon Press.

Brighenti, A. (2010) ‘Artveillance: At the Crossroads of Art and Surveillance. Surveillance and Society, 7 (2), pp. 137-148. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320143264_Artveillance_At_the_Crossroads_of_A rt_and_Surveillance (Accessed: 22/11/23).

Bright, R. (2020) ‘A visceral encounter with the near future’, Interalia Magazine, (September). Available at:https://www.interaliamag.org/interviews/heather-dewey-hagborg/ (Accessed: 22/11/23).

Calipsa (2022) UK CCTV and crime prevention statistics: your FAQs answered Available at: https://www.calipsa.io/blog/cctv-statistics-in-the-uk-your-questions-answered (Accessed: 22/11/23).

Casey, D. (2000) ‘Sacrifice, Piss Christ, and Liberal Excess’, Law Text Culture, 5 (1), pp. 935. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/59964226/Law_and_The_Sacred_Sacrifice_Piss_Christ_and_Libe ral_Excess (Accessed: 14/11/23).

Cejudo, R. (2021) ‘J. S. Mill on Artistic Freedom and Censorship’, Utilitas, 33(2), pp. 180192. Available at: doi:10.1017/S0953820820000230 (Accessed: 13/11/23).

Cotton, C. (2004) The Photograph as Contemporary Art 1st edn. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd

Crapo,T.(2015)‘AFamilyRecipe’, The Women’s Review of Books,32(6),pp. 3-5.Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26433142?seq=2 (Accessed: 28/12/23).

Deitcher, D. (2004) ‘SPIRITUAL AMERICA’, Artforum, 43 (2). Available at: https://www.artforum.com/columns/spiritual-america-169723/(Accessed:13/11/23).

Dewey-Hagborg, H. (2016) Postgenomic Identity: Art and Biopolitics, Dissertation. The Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/openview/5b4724522079955d6f69a90c1dd814c2/1?cbl=51922&d iss=y&parentSessionId=hgg5O%2BKA2vZenk%2FlklwSf2Aik2A3NuXYuabFeszLJHc%3D &pq-

origsite=gscholar&parentSessionId=4bmvLyV0CgsmDDqa941s7jES%2Fh2LXXHi2xEGfH zwprQ%3D (Accessed: 22/11/23).

Dewey-Hagborg, H. (2019) ‘The Adjacent Interview: Heather Dewey-Hagborg’. Interviewed by N. Fernandez and A. Vaseghi for Adjacent. Available at: https://itp.nyu.edu/adjacent/issue-5/the-adjacent-interview/ (Accessed: 2/10/23).

Dewey-Hagborg, H. (2023) Bio. Available at: https://deweyhagborg.com/bio (Accessed: 16/10/23).

Evans, M. (2015) 'ART IN THE FRAME: SPIRITUAL AMERICA AND THE ETHICS OF IMAGES', Journal of Aesthetics and Phenomenology, 2 (2), pp. 143-170. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20539320.2015.1112037 (Accessed: 13/11/23).

Farrington, J. (2015) ‘Spiritual America 2014’, Index on Censorship, (21 July). Available at: https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2015/07/case-study-spiritual-america-2014/ (Accessed: 13/11/23).

Foucault, M. (1975) Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Available at: https://monoskop.org/images/4/43/Foucault_Michel_Discipline_and_Punish_The_Birth_of_t he_Prison_1977_1995.pdf (Accessed: 02/01/24).

Foucault, M. (1984) Interview avec Michel Foucault, in: D. Defert & F. Ewald (Eds) with J. Lagrange Dits et écrits: 1954-1988, 4 (1), pp. 654-660. Paris: Editions Gallimard.

Goodyear, M. (2020). Transfixed in the camera's gaze: foster v. svenson and the battle of privacy and modern art. Harvard Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law, 11(1), pp. 41-72. Available at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?collection=journals&handle=hein.journals/harvsel11&id =64&men_tab=srchresults# (Accessed: 22/11/23).

Hirsch, M. (1997) Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Post Memory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Holert, T. (2016) “Exposure Without Intelligibility. On Some Requirements of Addressing Surveillance as a Visual Practice”, in Wolthers, L [ed.] Watched! Surveillance, Art, and Photography. Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, pp. 276-280.

Holpuch, A. (2012) ‘Andres Serrano's controversial Piss Christ goes on view in New York’, The Guardian, (28 September). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/sep/28/andres-serrano-piss-christ-new-york (Accessed: 14/11/23).

Isaacs, D. and Isaacs, T.G. (2010), ‘Is child nudity in art ever pornographic?’ Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 46, pp. 369-371. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14401754.2010.01804.x (Accessed: 10/11/23).

Joh, E, E. (2006) ‘Reclaiming “Abandoned Dna”: The Fourth Amendment and Genetic Privacy’, Northwestern University Law Review, 100(2), pp. 857-884. Available at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?public=true&handle=hein.journals/illlr100&div=39&start_ page=857&collection=journals&set_as_cursor=1&men_tab=srchresults (Accessed:23/10/23)

Julius, A. (2002) Transgressions The Offences of Art. 1st edn. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd

Kayahan Dal, G. (2022). ‘Art & Censorship: Can Art be Harmful?’, International Journal of Social and Humanities Sciences, 6 (1), pp. 31-50. Available at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ijshs/issue/71328/1146522 (Accessed: 14/11/23).

Lippard, L. (2023) ‘From the Archives: Andres Serrano, The Spirit and The Letter’, Art in America, (5 January) Available at: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/andresserrano-provocative-work-lucy-lippard-1234652353/ (Accessed: 14/11/23).

Lütticken, S. (2005) ‘The Feathers of the Eagle’, New left review, 36. Available at: https://doi.org/info:doi/ (Accessed: 10/11/23).

Mann, S. (2015) Hold Still 1st edn. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

McCahill, M. and Norris, C. (2002) ‘CCTV in London’, Urban Eye Project, Available at: http://www.urbaneye.net/results/ue_wp6.pdf (Accessed: 30/12/23).

McCahill, M. and Norris, C. (2006) “CCTV: Beyond Penal Modernism?” The British Journal of Criminology, 46 (1), pp. 97–118. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23639334 (Accessed 02/01/24).

Nightingale, L. (2014) ‘A discussion of Utopian themes in Sally Mann's work ‘Immediate family’’, Academia, pp 1 - 16. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/34631449/A_discussion_of_Utopian_themes_Sally_Manns_work _Immediate_family_ (Accessed: 2/10/23).

Parsons, S. (2008) ‘Public/Private Tensions in the Photography of Sally Man’, Taylor & Francis Online, 32:2, pp 123-136. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03087290801895720 (Accessed: 3/10/23).

Phelan, P. (1990) ‘Serrano, Mapplethorpe, the NEA, and You: "Money Talks": October 1989’, TDR, 34 (1), pp. 4-15. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1145999 (Accessed: 14/11/23).

Plato (1974) The Republic Translated from the Greek by H, D, P, Lee. London: Penguin Books.

Prince, R. (1988) ‘Richard Prince’. Interview with Richard Prince. Interview by Marvin Heiferman for BOMB magazine, 1 July. Available at: https://bombmagazine.org/articles/richard-prince/ (Accessed: 13/11/23).

Prince, R. (2023) ‘I SECOND THAT EMOTION 1977-78’, Richard Prince Available at: http://www.richardprince.com/writings/i-second-that-emotion-1977-78/ (Accessed: 13/11/23).

Richards, N. M. (2013) ‘The Dangers of Surveillance’ Harvard Law Review, 126 (7), pp. 1934–1965. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23415062 (Accessed, 02/01/24).

Rowe, H, A. (2011) ‘Appropriation in Contemporary Art’, Inquiries Journal, 3 (6). Available at: http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1661/appropriation-in-contemporary-art (Accessed: 13/11/23).

Savage, S, L. (2017) ‘Through the Looking Glass: Sally Mann and Wonderland.’ Visual Arts Research, 43 (2), pp. 5–20. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/visuartsrese.43.2.0005?seq=1 (Accessed 28/12/23).

Senior, A. (2009) ‘Privacy Protection in a Video Surveillance System’, in A. Senior (ed) Protecting Privacy in Video Surveillance” New York: Springer-Verlag London Limited 2009, pp. 35-49.

Snow, P. (2020) ‘Richard Prince Showed Me the Impossible Contradictions of Female Sexuality’, ELEPHANT, (23 June). Available at: https://elephant.art/richard-prince-spiritualamerica-showed-me-the-impossible-contradictions-of-female-sexuality-23062020/ (Accessed: 13/11/23).

Steinberg, M. (2022) Extralegal Portraiture: Surveillance, between Privacy and Expression. Grey Room, 87: pp. 66–99. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1162/grey_a_00342 (Accessed: 22/11/23).

Swanson, C. (2014) ‘How Richard Prince Got Kicked Off Instagram (And Then Reinstated)’, VULTURE, (8 March). Available at: https://www.vulture.com/2014/03/how-richard-princegot-kicked-off-instagram.html (Accessed: 13/11/23).

Tan, D. (2013) ‘What Do Judges Know About Contemporary Art?: Richard Prince and Reimagining the Fair Use Test in Copyright Law’, Law Journal Library, 2, pp. 63-80. Available at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?collection=journals&handle=hein.journals/judioruie2013&i d=363&men_tab=srchresults (Accessed: 13/11/23).

Tremblay, É. (2014). ‘Stranger Visions by Heather Dewey-Hagborg: Reinterpreting Portraiture Through New Forensic and 3D Printing Techniques’ ETC MEDIA, 103, pp. 44–48. Availableat: https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/etcmedia/2014-n103etcmedia01585/72960ac/ (Accessed, 02/01/24).

Tunick, M. (2000) ‘Privacy in the Face of New Technologies of Surveillance’. Public Affairs Quarterly, 14(3), pp. 259–277. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40441261 (Accessed: 22/11/23).

Turner, C. (2009) ‘Sugar and Spice and all things not so nice’, The Guardian, (3 October). Available at: Sugar and Spice and all things not so nice | Photography | The Guardian (Accessed: 12/11/23).

Westin, A. (1967) Privacy and Freedom. New York: Ig Publishing.

Williams, M. (2020) This Artwork Changed My Life: Sally Mann’s ‘Immediate Family’ Availableat:https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-artwork-changed-life-sally-mannsimmediate-family (Accessed: 2/10/23).

Wolthers, L. [ed.] (2016) Watched! Surveillance, Art, and Photography. Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König.

Zuboff, S. (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism London: Profile Books Ltd.