UN PUNTO CASI PERDIDO

en la inmensidad del desierto chihuahuense es la cuna de un movimiento cultural y artístico con repercusión mundial, cuyo alcance nadie sospechaba.

An almost forgotten place in the vast Chihuahuan Desert is the birthplace of a cultural and artistic movement with global repercussions that no one could have anticipated.

Cerca de allí, se ubica el humilde hogar de un

NIÑO INQUIETO

destinado a hablar con la naturaleza, aprender su lenguaje y convertirlo en arte.

Not far from there is the humble home of a restless child destined to communicate with nature, learn its language, and transform it into art.

Creció hasta convertirse en un hombre de pocas palabras, pero capaz de entender el idioma

DEL BARRO Y DEL FUEGO

He grew into a man of few words but was able to understand the language of clay and 昀椀re.

De sus manos nacieron las más so昀椀sticadas creaciones que un

ALFARERO

de su tiempo y su tierra pudiera imaginar… Y con ellas, una explosión artística que ha iluminado a generaciones.

From his hands emerged the most sophisticated creations that a potter of his time and place could only imagine, along with an artistic explosion that has inspired generations.

COMITÉ EDITORIAL

Editorial comitee

Federico Terrazas Becerra, presidente / president

Enrique Escalante Ochoa

Daniel Helguera Moreno

Luis Jorge Amaya González

María Isabel Sen Venero

David Villegas Becerra

COORDINACIÓN INSTITUCIONAL

Institutional coordination

Daniel Helguera Moreno

David Villegas Becerra

TEXTOS Y TRADUCCÍÓN DE

Texts and translation by Marta Turok

ASISTENTE DE INVESTIGACIÓN

Research asssistant

Sara Meneses Cuapio

FOTOGRAFÍA

Photography

Nacho Guerrero

FOTO DE PORTADA

Cover photo

Jorge Vértiz publicada en la edición 45 de la revista Artes de México / Published in the 45th edition of Artes de México magazine.

IMPRESIÓN

Printing

SPI, SERVICIOS PROFESIONALES

DE IMPRESIÓN, S. A. de C. V. www.spi.com.mx

EDICIÓN Y DISEÑO

Editing and design

Sagrario Saraid, publisher

Gabriel Bauducco, editor

Alejandro Argandona, diseñador grá昀椀co / graphic designer

Sergio Moncada, diseñador grá昀椀co / graphic designer

Ángeles López Nápoles, diseñadora grá昀椀ca / graphic designer

Edición en español / spanish editing

Ofelia Salgado González, correctora de estilo / proofreader

Adán Medellín, dictaminador / reviewer

Fabiola de la Fuente, dictaminadora/ reviewer

Edición en inglés / English editing

Gabriella Morales Casas, dictaminadora / reviewer

Alexandra Jurado, correctora / proofreader

dobleuEse Atelier S. A. P. I. de C. V. www.dobleueseatelier.com

Revisión de estilo en inglés / Language and style

Maggie Galton y Leigh Thelmadatter

CONTRIBUCIONES DE FOTO

Photo contributions

Jorge Vértiz: pgs 11, 16, 17, 20, 102, 218, 219, 221, 309

Imágenes aparecidas en la edición 45 de la revista

Artes de México / Images appeared in edition 45 of Artes de México magazine.

Luis Colmenares Bottini: pág. 297

Martín Ayala: pgs. 45, 58, 59, 60, 61, 96, 97, 134, 136, 137, 235

The Museum of Us: pgs. 110, 111, 112, 114, 115, 116, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 130

Bobby Furst / The Museum of Us: pág. 107

John Malmin / The Museum of Us: pgs. 105, 108, 129

Camila Laguette: pág. 293

www.mataortizgallery.com: pgs. 272, 273, 274

JUAN QUEZADA, DREAMS OF CLAY AND FIRE

MATA

“PARA MÍ ES MUY SATISFACTORIO

QUE UNA

FAMILIA PUEDA VIVIR DE LA ALFARERÍA UN AÑO, DOS O TRES, POR LO QUE YO HICE.”

JUAN QUEZADA

“It is very satisfying for me that a family can live o昀昀 pottery making for a year, two, or even three, because of what I accomplished.”

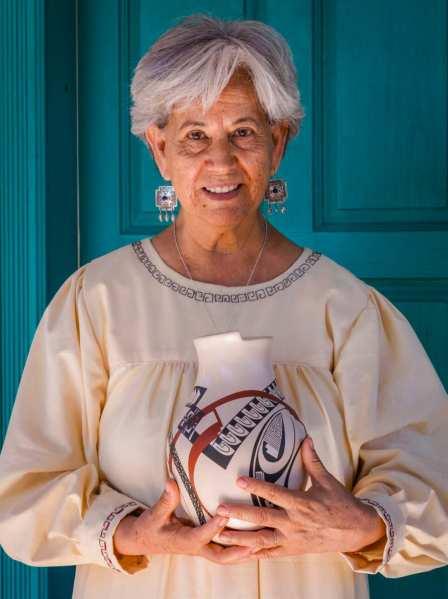

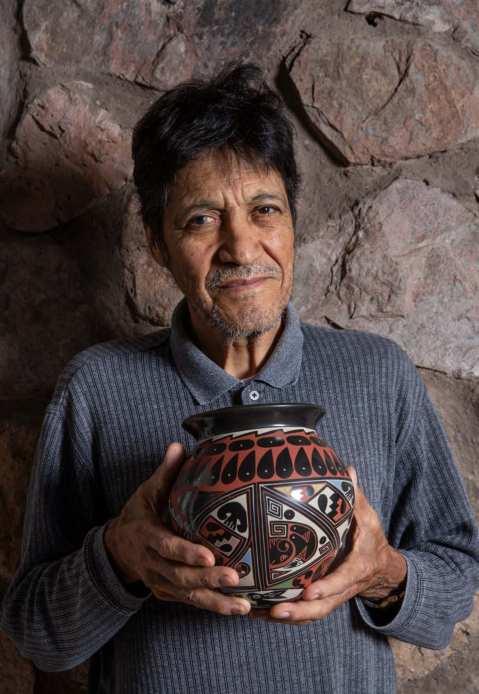

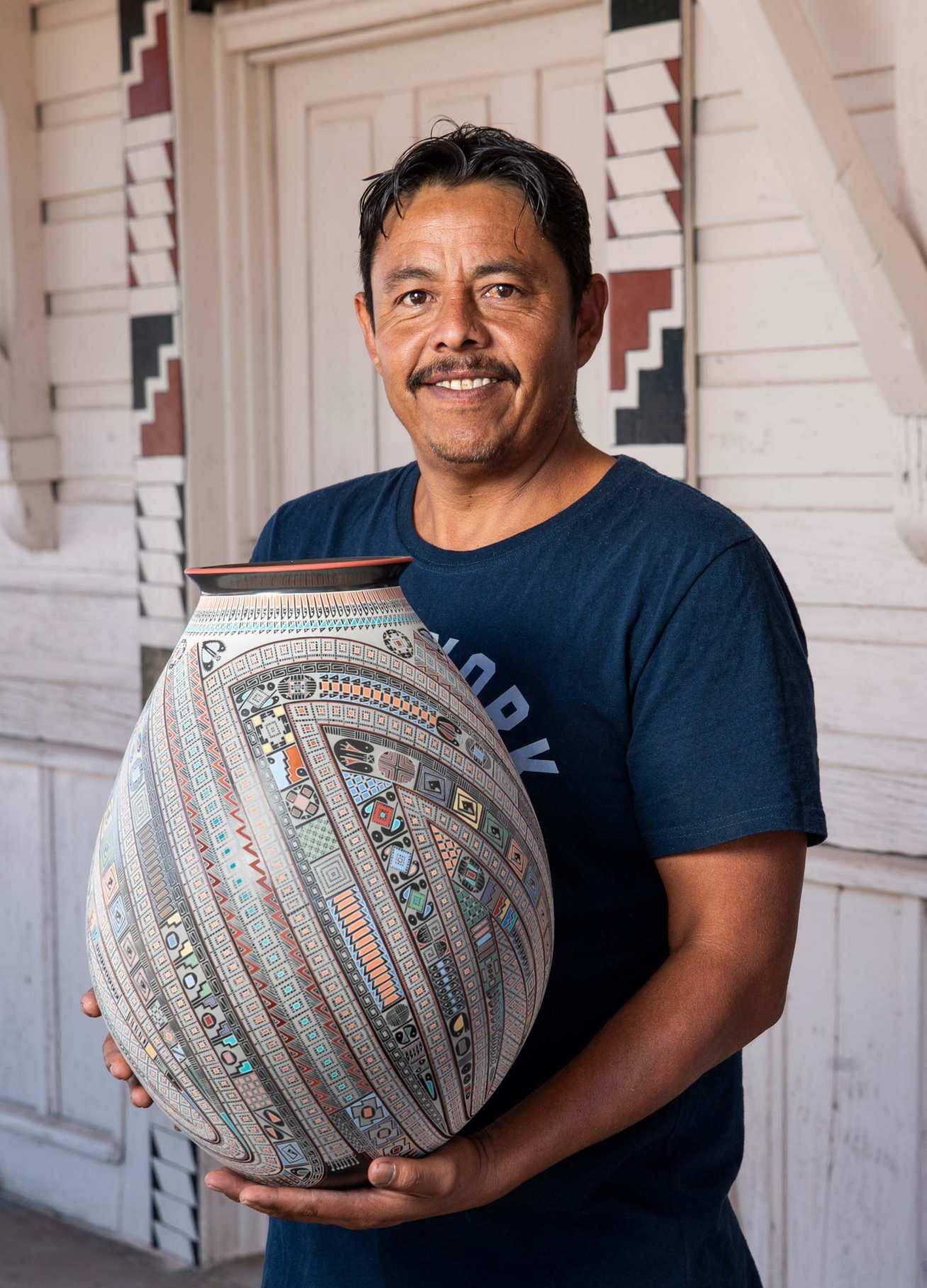

Juan Quezada Celado. Olla de barro blanco, decoración polícroma en tercios. White clay pot, polychrome decoration in thirds.

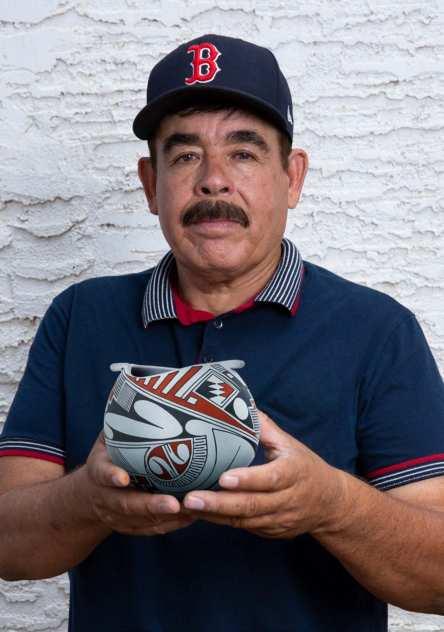

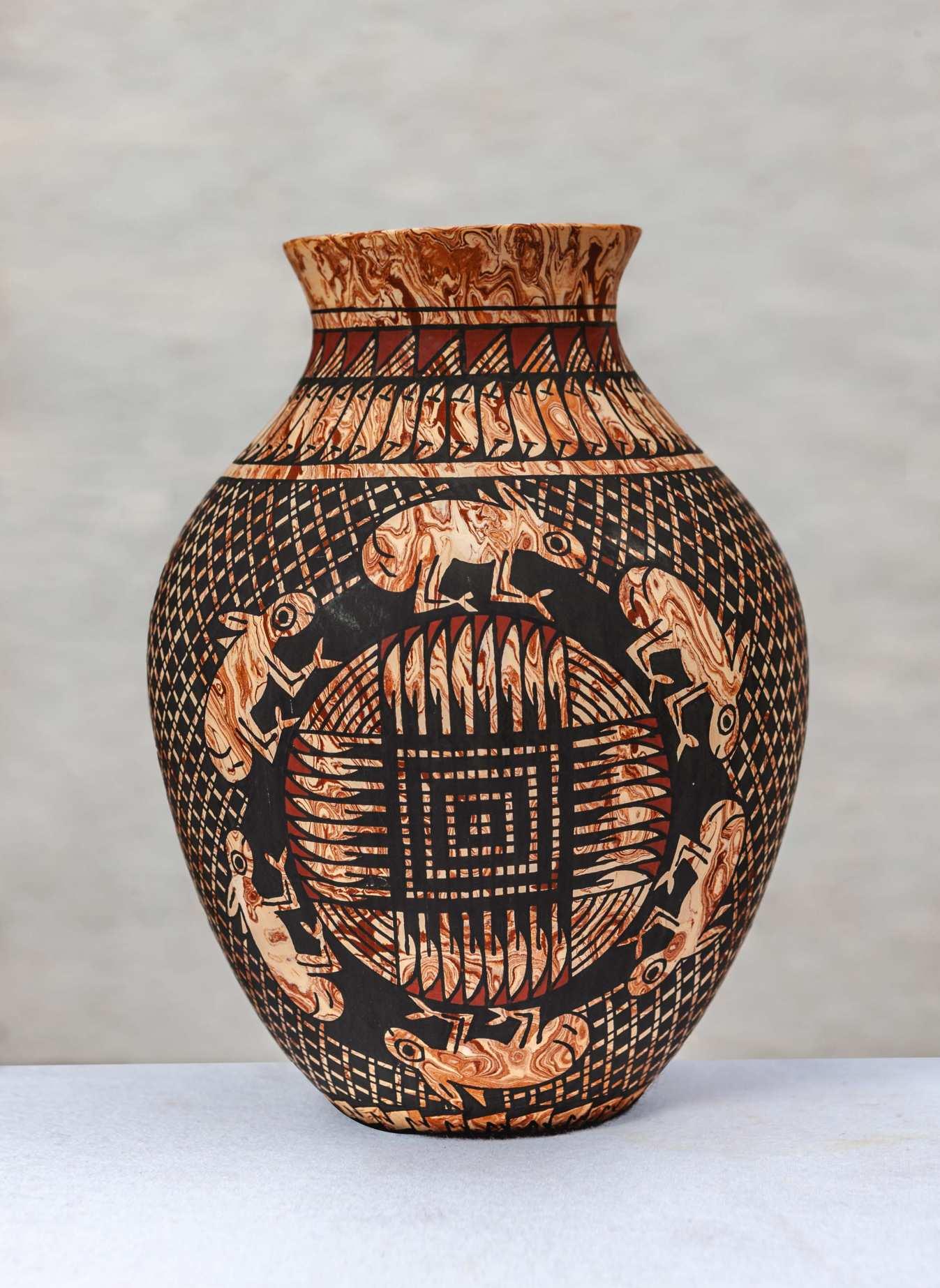

Olla de Damián EscárcegaQuezada. Barroblancocon decoraciónpolícroma seccionadaenoctavos.Whiteclaypot, polychromedecorationineightsections.

PRESENTACIÓN

PRESENTATION

La colección editorial de GCC ha sido –y continúa siendo– un re昀氀ejo de innumerables historias y hazañas que nos ayudan a preservar el rico acervo cultural del estado grande, siempre con el 昀椀rme propósito de promover y conservar el testimonio de Chihuahua y su gente.

La primera edición de la colección GCC se remonta a 1988. Su obra inaugural fue Explorando un mundo olvidado Sitios perdidos de la cultura Paquimé Transcurridas más de tres décadas, parece justo dar continuidad a la historia de esta fascinante civilización que sirvió de soplo creador para construir un sueño de barro y fuego.

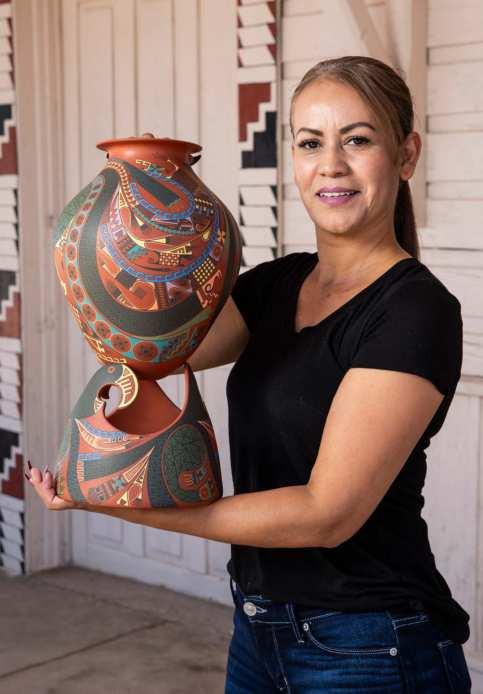

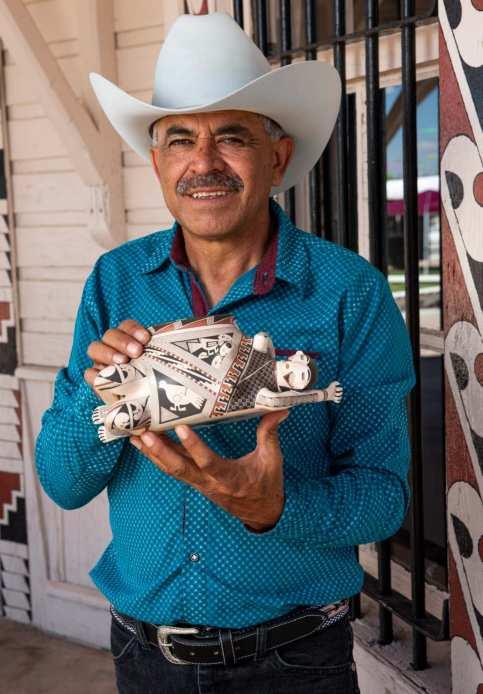

Con el ejemplar que tiene en sus manos –Mata Ortiz. Juan Quezada, sueños de barro y fuego– realizamos un recorrido por el pasado, presente y futuro del noroeste del estado de Chihuahua. En este viaje nos guía la reconocida antropóloga Marta Turok, cuya pluma detiene, regresa y adelanta el tiempo. También nos acompaña la lente de Nacho Guerrero, cuyas imágenes nos transportan a un mundo distinto. Las piezas retratadas por Jorge Vertiz y otros reconocidos fotógrafos nos permiten revelar la eternidad de un sueño que perdura hasta nuestros días.

Esta obra no solo reconoce la belleza de Mata Ortiz –su gente y su arte, que emergen como tributo a la cultura Paquimé– también distingue la creatividad sin límites de Juan Quezada Celado, gran exponente del arte popular y alfarería mexicana. Con sus manos logró capturar la esencia de paisajes, aspectos culturales y locales. Para hacerlo, también se sirvió de la simbología ancestral y preservó las técnicas más antiguas de la alfarería, mismas que hoy rebasan fronteras.

GCCcumpledenuevacuentaconel昀椀rmecompromiso de cuidar nuestro patrimonio histórico y cultural. Sobre todo, continuar con el tributo a los chihuahuenses que nos impulsan a seguir construyendo juntos el futuro de nuestra tierra, honrando nuestro origen.

The GCC editorial collection has been -and continues to be- a re昀氀ection of countless stories and feats that help us preserve the rich cultural heritage of the largest state in Mexico, always with the 昀椀rm purpose of promoting and preserving the sense of legacy of Chihuahua and its people.

The 昀椀rst edition of the GCC collection dates back to 1988, with its inaugural work being Exploring a Forgotten World. Lost sites of the Paquimé Culture. More than three decades later, it seems 昀椀tting to give continuity to the history of this fascinating civilization that inspired the creation of a dream built from 昀椀re and clay.

With the volume you have in your hands – “Mata Ortiz. Juan Quezada, dreams of 昀椀re and clay” -we embark on a journey through the past, present, and future of the northwestern state of Chihuahua. Our guide on this journey, is the renowned anthropologist Marta Turok, whose writing stops, rewinds, and fastforwards time. We are also accompanied by the lens of Nacho Guerrero, whose images transport us to a di昀昀erent world. The pieces portrayed by Jorge Vertiz and other renowned photographers reveal the timelessness of a dream that endures to this day.

This work not only recognizes the beauty of Mata Ortiz - its people and its art, which emerge as a tribute to the Paquimé culture - but also highlights the boundless creativity of Juan Quezada Celado, a great exponent of Mexican folk art and pottery. With his hands, he captured the essence of landscapes, cultural aspects and local features. To do so, he also drew upon ancestral symbolism and preserved the most ancient techniques of pottery, which today transcend borders.

GCC once again ful昀椀lls its 昀椀rm commitment to care for our historical and cultural heritage. Above all, we continue to pay tribute to the people of Chihuahua who inspire us to continue building the future of our land together, honoring our origins.

PRESENTACIÓN Presentation PRÓLOGO Prologue

DESTINO DE GRANDEZA

Destiny of Greatness

28. La guerra que “traíba” dentro

The War that Stirred Within

44. El pasado nutre una curiosidad nata

The Past Nurtures an Innate Curiosity

46. Oasisamérica, un enigma cultural

Oasisamerica, a Cultural Enigma

54. Primeras exploraciones

First Explorations

62. La olla que tardó quince años

The Pot that Took Fifteen Years

98

A PRUEBA Y ERROR

Trial and Error

66. El barro, la materia prima del o昀椀cio

Clay: the Raw Material of the Craft

68. Trabajar la pieza

Working the Piece

80. Lijar y pulir

Sanding and Burnishing

84. La pintura: colores y pinceles

Painting: Colors and Brushes

92. Las quemas

Firing

94. Comienza la expansión

Expansion Begins

EL CONTEXTO REGIONAL

The regional context

104. Dos caminos, un destino

Two Roads, One Destiny

110. El proceso creativo

The Creative Process

116. Valores en una 昀椀rma

Values in a Signature

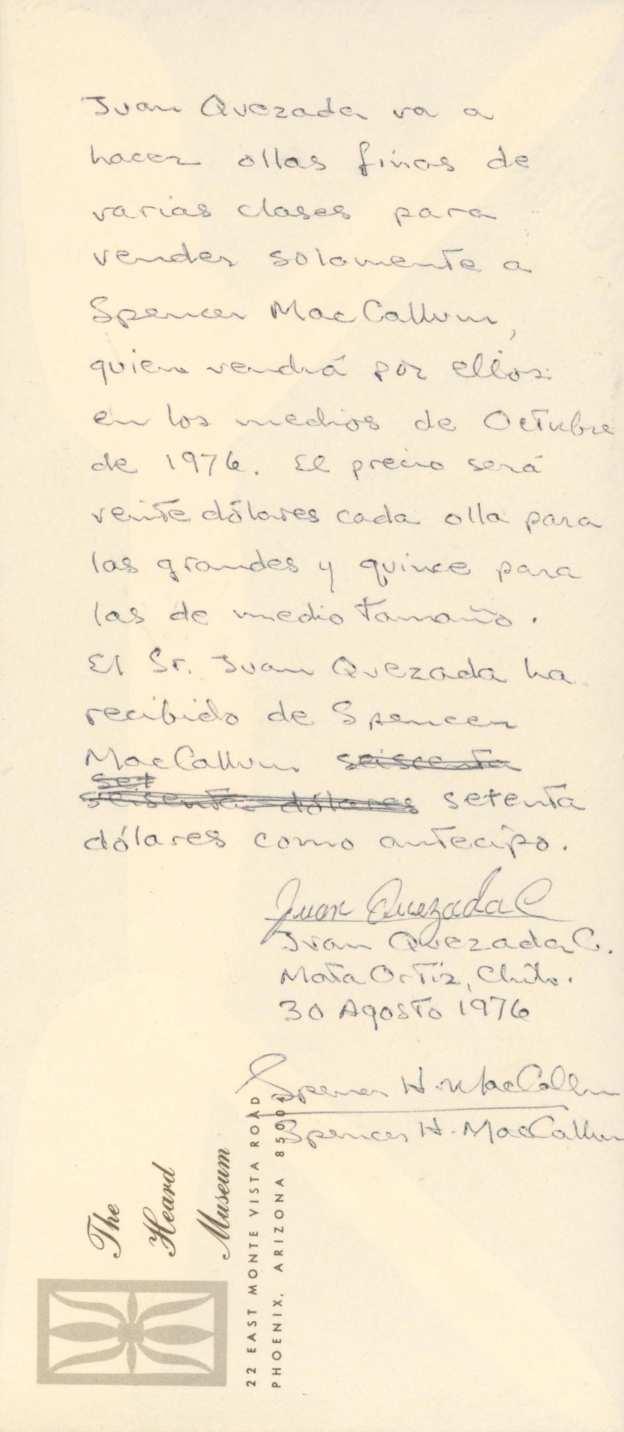

126. Spencer, mecenas y promotor

Spencer, Patron and Promoter

134. Un museo para Paquimé

A Museum for Paquimé

MATA ORTIZ: JUAN QUEZADA, 212527 64

SUEÑOS DE BARRO Y FUEGO

LA EVOLUCIÓN CREATIVA

A Creative Evolution

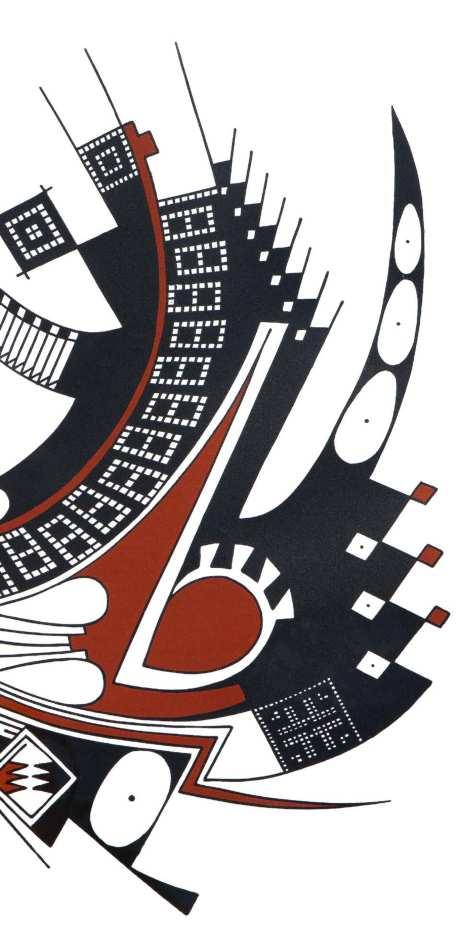

146. Matriz de diseños de Paquimé y Mata Ortiz

Matrix of Paquimé and Mata Ortiz Designs

148. Los trazos y sus signi昀椀cados

The Strokes and Their Meanings

196. Estilos y variaciones

Styles and Variations

198. Colores de barros

Clay Colors

206. Las formas

Shapes

214. La «piel» de la olla

Intervening with the Surface of the Pot

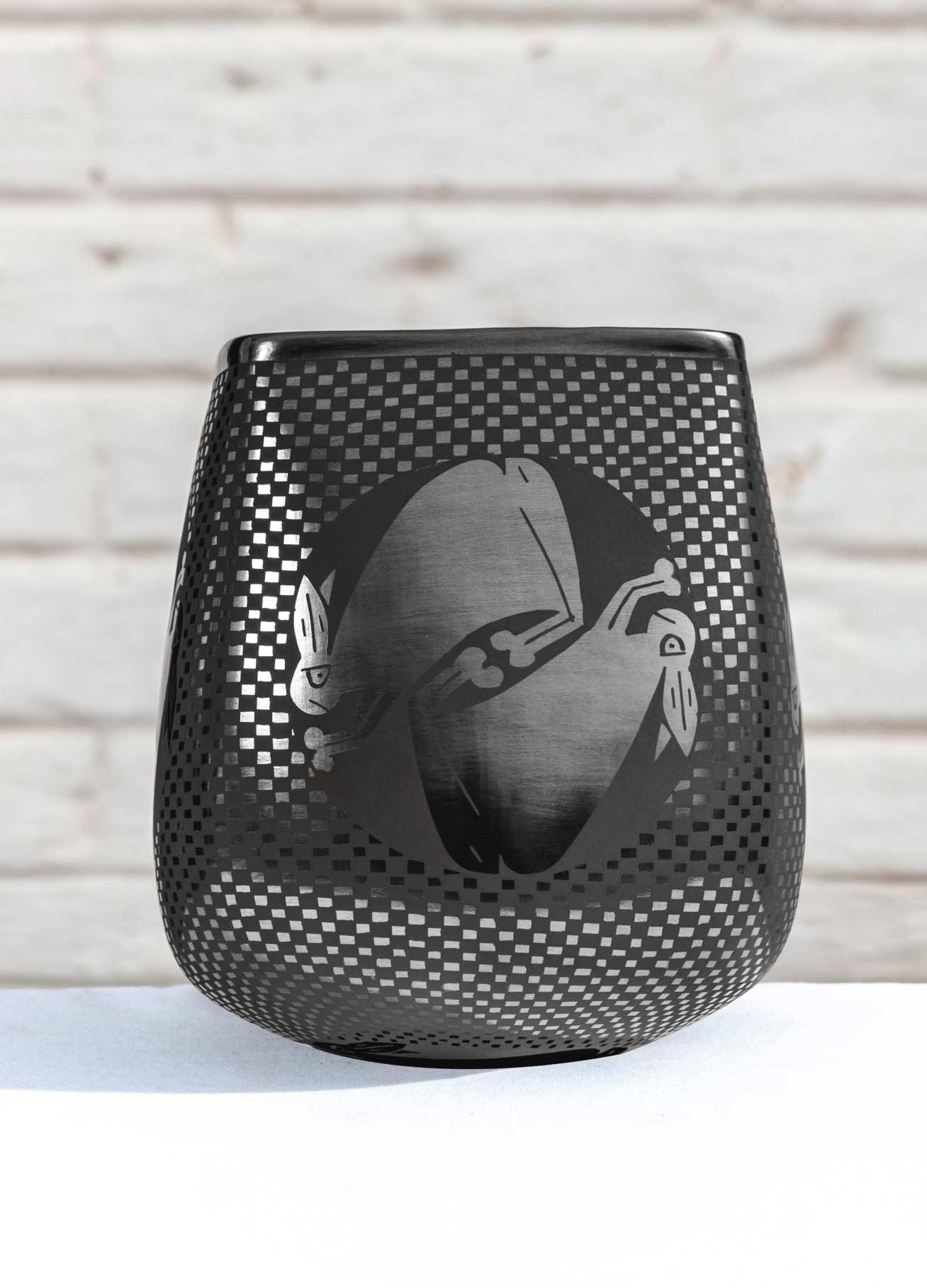

218. Las ollas negras

The Black Pots

228. Las manos en la masa (per昀椀les)

A Show of Hands (Pro昀椀les)

270. Retos y alternativas

Challenges and Alternatives

272. Estrategias de promoción

Promotion Strategies

276. Másalládelasollas,apoyosalacomunidadylaeducación

Beyond the Pots: Community and Education Support

278. Fortalecer la experiencia del comprador

Upgrading the Buyer Experience

282. Nuevas aplicaciones y caminos

New Applications and Paths

284. Grabados

Engravings

290. Joyería

Jewelry

292. Tatuajes

Tattoos

294. Ropa pintada y accesorios

Painted Clothing and Accessories

296. Arte público

Public Art

MATAORTIZ: JUANQUEZADA,DREAMS OFCLAYANDFIRE

¿CUÁNTO CUESTA? ¿CUÁNTO VALE?

How Much Does it Cost? How Much is it Worth?

SUEÑOS DE BARRO Y FUEGO Dreams of Clay and Fire

25 AÑOS DESPUÉS

25 Years Later

AGRADECIMIENTOS

Acknowledgments

LITERATURA CONSULTADA

Referenced Literature

PRÓLOGO

PROLOGUE

“Para formar la Tierra, (el dios) Marduk empleó un procedimiento de mezclar barro y cañas construyendo una barca, sobre la cual creó al hombre con su propia sangre amasada con el barro”, dice un poema babilónico de entre 669 a. C. y 627 a. C. Si un ser supremo mezcló el barro para dar vida a los seres humanos, ¿cómo no iban las personas a fascinarse con los materiales paridos por siglos y siglos de vida en el planeta? Desde tiempos muy remotos y en culturas muy diversas, el barro y la creación han estado ligados a la existencia de los humanos. Para muchos, el mismísimo Dios es alfarero

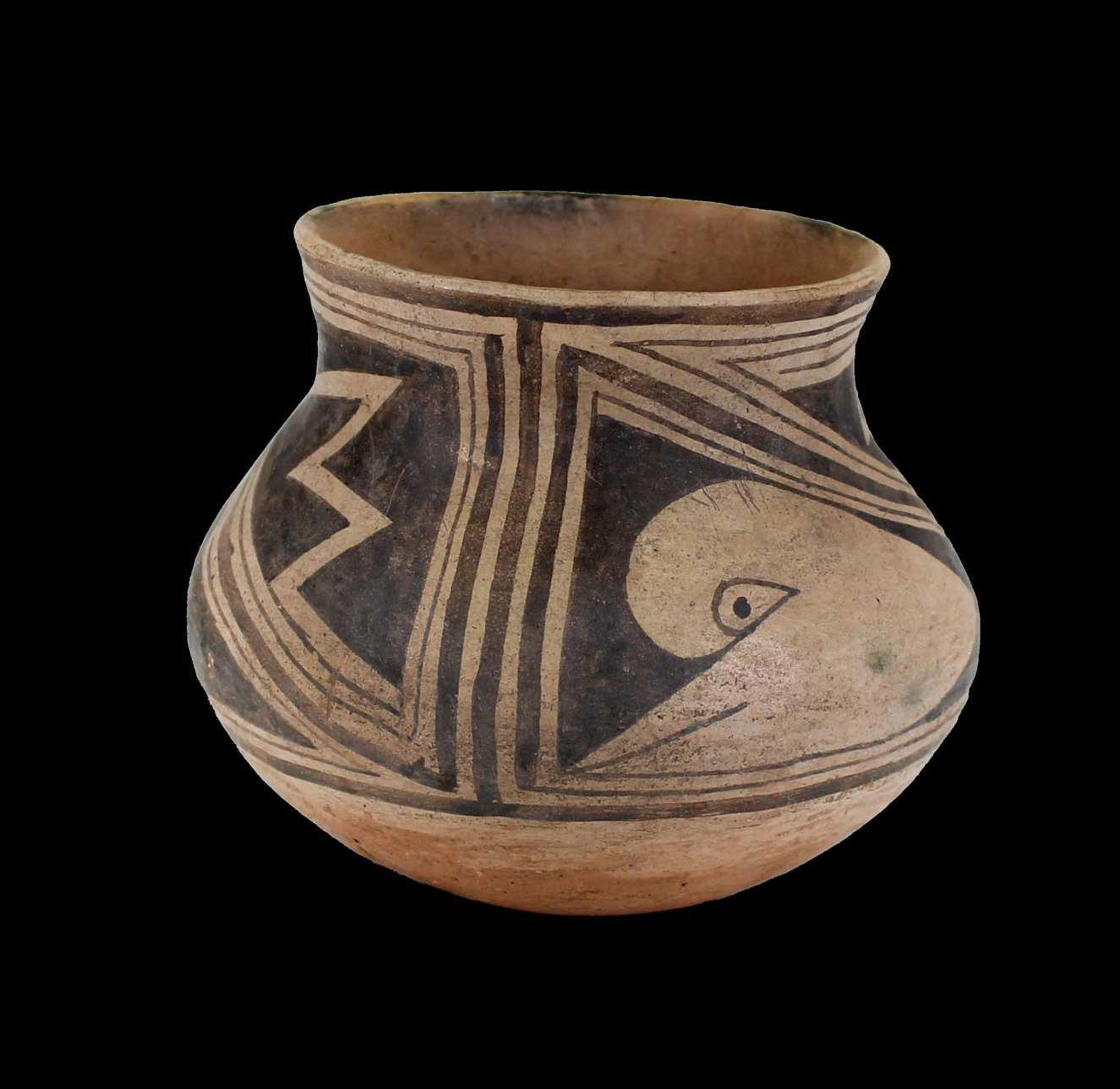

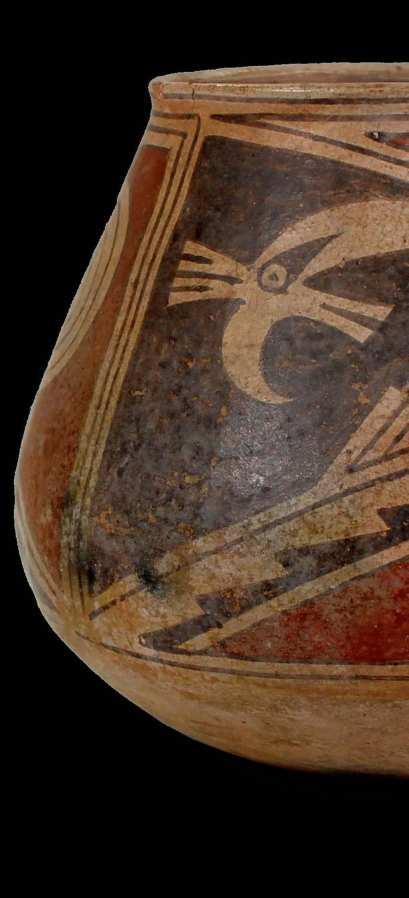

Hace mil años los habitantes de Paquimé se abocaron a la producción de piezas utilitarias que les hacían más fácil la vida cotidiana y luego usaron el barro con 昀椀nes rituales. Sin duda, no imaginaban entonces el impacto que sus vasijas –y el testimonio involuntario que ellas atesoraban– tendrían en la posteridad. Desde las cocinas hasta los yacimientos mortuorios, las ollas estaban presentes. Esa herencia es la que hoy, reinventada de mil maneras por algunas generaciones de artesanos, forma parte de la identidad de las cerámicas de Mata Ortiz, que tienen un bien ganado lugar entre las más cotizadas del planeta. El nivel artístico que alcanzan fascina a coleccionistas de diversos rincones del mundo. Desde Chihuahua, una expresión ceramista so昀椀sticada y rotunda atrae la atención de los ojos más entrenados en el universo de la alfarería.

Estas páginas son un viaje al origen de un movimiento cultural y artístico sin precedentes.

“To form the Earth, (the god) Marduk employed a procedure of mixing clay and reeds, constructing a boat upon which he created man, with his own blood kneaded with the clay”, reads a Babylonian poem from between 669 B.C. and 627 B.C. If a supreme being mixed clay to give life to human beings, how could people not be fascinated by the materials shaped by centuries of life on this planet? Since ancient times and across diverse cultures, clay and creation have been linked to human existence. For many, God himself is a potter.

A thousand years ago, the inhabitants of Paquimé devoted themselves to producing utility pieces that made their daily lives easier, and they also used clay for ritual purposes. They could not have imagined the impact their vessels—and their legacy—would have on posterity. From kitchens to mortuary sites, pots were always present. This heritage, now reinvented in many ways by several generations of artisans, forms the core of Mata Ortiz ceramics, which have earned a distinguished place among the most sought-after in the world. The artistic quality of these ceramics captivates collectors from various corners of the globe. From Chihuahua, a sophisticated and resounding ceramic tradition captures the attention of the most discerning eyes in the pottery world.

These pages o昀昀er a journey to the origins of an unprecedented cultural and artistic movement.

GABRIEL BAUDUCCO Editor

DESTINO DE GRANDEZA

Destiny of greatness

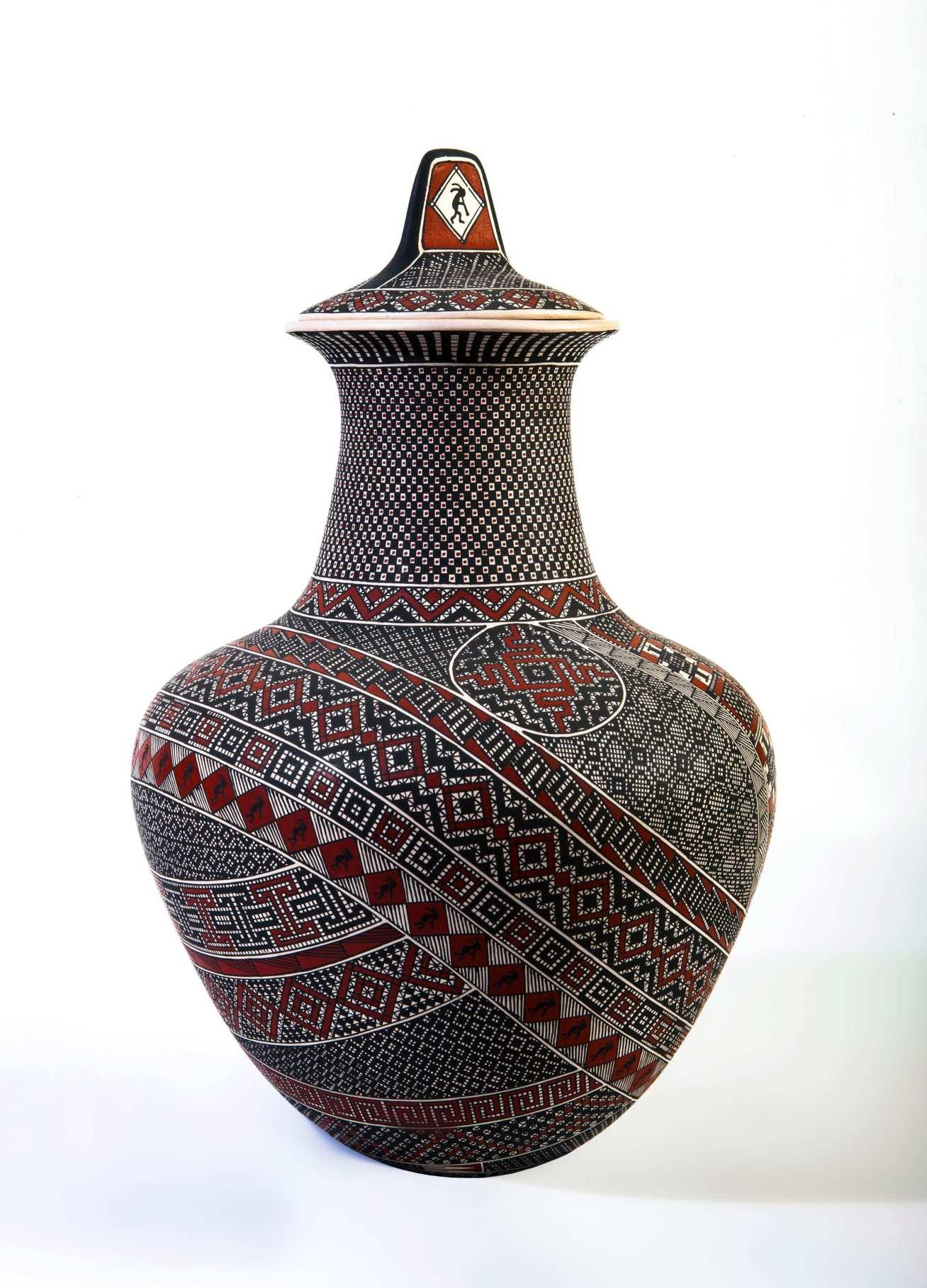

En la década de 1970, al norte de México surgió una sorprendente cerámica inspirada en la extinta cultura de Casas Grandes. Localmente se la conoce como Paquimé, por el sitio arqueológico que lleva ese nombre. Lo que inició como la mera reproducción y recreación de las ollas prehispánicas de la zona, en el pequeño poblado de Juan Mata Ortiz se convertiría en un verdadero movimiento de arte contemporáneo. En él destacan la calidad, la maestría técnica y una propuesta estética dinámica. Al ir dándose a conocer, creció su reconocimiento como una de las cerámicas hechas a mano más re昀椀nadas del mundo.

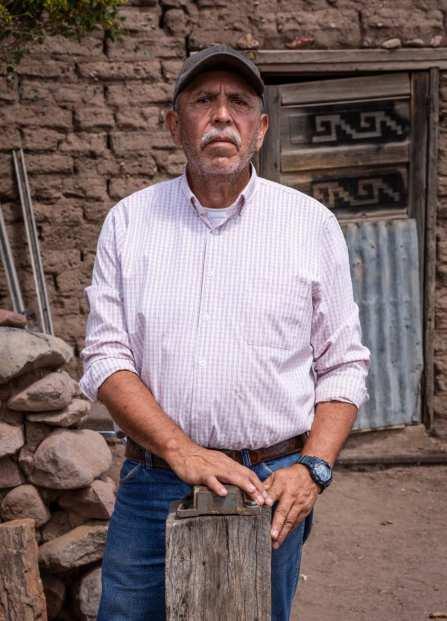

Al cumplirse dos años de la partida de Juan Quezada Celado (1940-2022), esta obra rinde un doble homenaje al hombre y su legado, para honrar la vida y la obra de un leñador que nació con un “don”. Su búsqueda lo condujo a lo largo de quince años a redescubrir el complejo proceso cerámico, sin guía ni maestro más que su inteligencia, su intuición y su curiosidad innata. También es necesario incluir y honrar a Spencer MacCallum (1931-2020), quién lo descubrió, nutrió y alentó a desarrollar sus capacidades al máximo, junto a otros que se sumaron al movimiento.

Así, se cuentan los hechos fortuitos que dieron paso a que Juan se encaminara al encuentro con su destino de grandeza, al de su familia y al de cientos de sus vecinos del pueblo y ejido de Mata Ortiz, incluidos aquellos que van migrando a Casas Grandes y a Nuevo Casas Grandes. El fenómeno de Mata Ortiz sigue deslumbrando, aquel consejo de Juan Quezada a los jóvenes de no conformarse, de seguir experimentando y de apostar por la calidad es uno de sus legados.

In the 1970s, a remarkable form of ceramics emerged inspired by the extinct Casas Grandes culture, in northern Mexico. Locally it is known as Paquimé, named after the archaeological site. What began as mere reproductions and recreations of pre-Hispanic pots, in the small town of Juan Mata Ortiz, soon evolved into a true contemporary art movement. This movement is distinguished by its quality, technical mastery, and dynamic aesthetic. As it gained recognition, it was soon acknowledged as one of the most re昀椀ned handmadeceramicsintheworld.

Two years after the passing of Juan Quezada Celado (1940-2022), this work pays a double tribute to the man and his legacy. It honors the life and work of a woodcutter born with a gift seemingly absent among his close ancestors, but undoubtedly representing one of humanity’s oldest crafts. Over 昀椀fteen years, his quest led him to rediscover the complex ceramic process, without any guide or master other than his own intelligence, intuition, and innate curiosity. It is also necessary to include and honor Spencer MacCallum (1931-2020), who discovered, nurtured, and encouraged Juan to fully develop his abilities, alongside others who joined the movement.

Until they found each other, they traversed the labyrinths of goodfortuneandheartbreak.Herewerecountthefortuitousevents that led Juan Quezada to meet his destiny of greatness, that of his family and that of hundreds of his neighbors in the town and ejido of Mata Ortiz, including those who are migrating to Casas Grandes and Nuevo Casas Grandes. The phenomenon of Mata Ortiz continues to dazzle, perhaps due largely to Juan Quezada’s advice to young people: do not settle or conform, rather experiment and striveforquality.Thisisoneofhislastinglegacies.

LA GUERRA QUE

“TRAÍBA”

DENTRO

The War that Stirred Within

Juan Quezada Celado, el cuarto hijo de José Quezada y Paula Celado, era un niño diferente, sensible, incansable, pero ¿cuándo fue evidente su espíritu creativo? ¿Un artista nace o se hace? Durante una entrevista en 1999, parecía tenerlo muy claro: «Desde que tuve uso de razón, a los 6 o 7 años, me gustó crear. En aquella época no se conocían las pinturas ni las herramientas para esculpir, pero yo hacía escultura y pintura. Me agradaba hacer muebles también, me gustaba todo lo que pudiera hacer con las manos».

Juan Quezada Celado, the fourth son of José Quezada and Paula Celado, was a di昀昀erent kind of child —sensitive and tireless. However, when did his creative spirit emerge and become evident? Is an artist born or made? During an interview in 1999, he seemed certain: “Ever since I can remember, around 6 or 7 years old, I loved creating. Back then, we didn’t have paints or sculpting tools, but I made sculptures and paintings. I also enjoyed making furniture, anything I could do with my hands.”

ÉL MISMO DESCUBRÍA LAS TIZAS Y PREPARABA SUS COLORES EXPERIMENTANDO

CON PIGMENTOS MINERALES Y VEGETALES; POR

EJEMPLO, YEMAS DE HUEVO, HOJAS VERDES, CHAPULINES”.

“He discovered the chalks himself and prepared his own colors, experimenting with mineral and plant pigments –egg yolks, green leaves, and grasshoppers”.

A los 13 años se dedicó a trabajar con madera, la más dura y difícil. Lo hacía junto a la ventana, desde donde escuchaba a su padre echarle un grito a su madre: —¿Dónde está Juan? —Pues ha de estar por ahí haciendo sus 昀椀guritas—, respondía ella. Era algo que no lograban entender, pensaba Juan.

Noé Quezada Olivas, su hijo, recuerda que alguna vez su abuelo agregó enfadado que así iban a «morirse de hambre», que necesitaba que Juan fuera a traer leña. La pobreza era palpable y cuando doña Paulita hacía tortillas de harina, era una 昀椀esta. Solo le tocaba una a cada uno; incluso a Juan, que había ido por la leña y le hacía señas de que le diera una más.

Para poder alimentar a su creciente familia, don José migraba por largos periodos a Estados Unidos, donde trabajaba como jornalero para enviar dinero de regreso a casa. Lidia Quezada, la hija menor, recuerda que entre esos viajes de su padre a Mata Ortiz doña Paulita quedaba embarazada.

La escuela no era para Juan, decía su madre. Lo aburría. Solo asistió a clases entre los 9 y 12 años. Tímido y solitario, se encerraba en una habitación cuando había visitas: «Déjeme en paz, mamá. No les diga dónde estoy».

Cuando no le tocaba ir por leña, pues se turnaban entre los hermanos, en cualquier oportunidad Juan se metía a una bodeguita que había en la casa y hacía dibujos en los muros encalados. «Mi satisfacción era pintarlos hasta acabar y retirarme para mirarlos. Cuando los veía bien, los borraba con un trapo con petróleo y pintaba otros». Él mismo descubría las tizas y preparaba sus colores experimentando con pigmentos minerales y vegetales; por ejemplo, yemas de huevo, hojas verdes, chapulines: «Cualquier cosa que tuviera color». (Samuelson, 2023, p. 176). Su hermana Lidia no se explica cómo los encontraba. Gerardo Cota, un joven vecino que realizó caminatas con la familia, recuerda cómo Juan se 昀椀jaba en todo a su paso, pateaba piedras y terrones que veía en el camino, los recogía y los guardaba. (Gerardo Cota, 5 de mayo, 2024.)

At 13 years old, he began working with wood, the hardest and most challenging, often by the window where he could hear his father shout to his mother, “Where’s Juan?” “He’s probably out there making his little 昀椀gures,” she would reply. It was something they couldn’t quite understand, Juan thought.

Noé Quezada Olivas, his son, remembers his grandfather was annoyed that they would “starve to death” this way, and that Juan needed to go fetch 昀椀rewood, not sculpt it! Poverty was palpable and when doña Paulita made 昀氀our tortillas, it was a feast. They only got one tortilla each; even Juan, who had collected the 昀椀rewood and felt entitled to an extra one, signaling to his mother to give him one more.

To feed his growing family, don José would migrate for long periods to the United States, working as a day laborer to send money back home. Lidia Quezada, the youngest daughter, recalls that between her father’s trips to Mata Ortiz, doña Paulita became pregnant.

School was not for Juan, his mother said. It bored him. He only attended classes between the ages of 9 and 12. Shy and solitary, he would lock himself in a room when there were visitors, saying, “Leave me alone, Mama. Don’t tell them where I am.”

Whenitwasn’thisturntofetch昀椀rewood,heandhisbrothers took turns, Juan would go to a small warehouse in the house and draw on the whitewashed walls. “My satisfaction came from painting them until they were 昀椀nished, then stepping back to look at them. When they looked good, I’d wipe them clean with a rag soaked in petrol and paint new ones.” He discovered the chalks himself and prepared his own colors, experimenting with mineral and plant pigments –egg yolks, green leaves, grasshoppers: “Anythingthathadcolor”.(Samuelson2023:176).HissisterLidia wonders how he found them. Gerardo Cota, a young neighbor who hiked with the family, recalls how Juan noticed everything along their path, kicking rocks and clumps of earth, picking them up and keeping them. (Gerardo Cota, May 5, 2024).

Sonora

Cueva de la Olla

80km

Sinaloa

Chihuahua

Casas Grandes

Paquimé

60km

Durango

Juan Mata Ortiz

Al norte de México, en Chihuahua, donde Juan Quezada vio nacer sus inquietudes. Northern Mexico, in Chihuahua, where Juan Quezada’s inclinations were born.

A unos cuantos kilómetros de la casa familiar, Juan Quezada tenía el rancho Barro Blanco, en el que pasaba muchas horas entregado a la creación. A few kilometers from the family home, Juan Quezada had the Barro Blanco ranch, where he spent many hours dedicated to creation.

Juan nació en 1940 en Tutuaca (Santa Bárbara de Tutuaca), municipio de Dr. Belisario Domínguez, un pueblo de la Sierra Madre Occidental, donde sus tíos paternos eran hábiles talabarteros, zapateros, carpinteros y ebanistas. Su madre, Paula (Paulita) Celado Sáenz era del cercano San Lorenzo, pueblo de origen rarámuri.

José Quezada Gallegos –padre de Juan– creció con su tío Sabino Hernández y doña Lupe, quienes decidieron migrar al valle de Mata Ortiz con la intención de criar vacas y buscar una mejor vida. Invitaron a sus parientes a acompañarlos en un viaje de diez horas hacia el norte, siguiendo la vía del tren. Juan, el cuarto de los diez hijos que llegarían a ser, tenía apenas un año cuando arribaron.

Juan was born in 1940 in Tutuaca (Santa Bárbara de Tutuaca), a municipality in Dr. Belisario Domínguez, a town in the Sierra Madre Occidental, where his paternal uncles were skilled leatherworkers (producing mostly saddles), shoemakers, carpenters, and cabinetmakers. His mother, Paula (Paulita) Celado Sáenz, was from nearby San Lorenzo, a town of Rarámuri origin.

José Quezada Gallegos –Juan’s father– grew up with his uncle Sabino Hernández and Doña Lupe, who decided to migrate to the Mata Ortiz valley with the intention of raising cows and looking for a better life. They invited their relatives to accompany them on a ten-hour journey north, following the train tracks. Juan, the fourth of ten children, was only a year old when they arrived.

BUSCAR LEÑA, TRAER MIEL SILVESTRE, CORTAR QUIOTES Y ASARLOS ERAN TAREAS

QUE JUAN LLEVABA A CABO EN ESOS AÑOS TEMPRANOS PARA AYUDAR AL SOSTÉN DE SU FAMILIA.

Fetching 昀椀rewood, gathering wild honey, cutting and roasting agave 昀氀ower stalks were tasks Juan performed in those early years to help support his family.

Años después, doña Paulita recordaría que, de su lado materno, su hermana mayor, abuela y bisabuela, entre otras, habían sido alfareras. Juan viajó a San Lorenzo con Spencer MacCallum –su mecenas y mentor– en busca de esas raíces. Descubrió que, hasta principios del siglo XX, este había sido un pueblo alfarero donde las mujeres trabajaban el barro, como las ollas utilitarias para hacer el tesgüino, la bebida de maíz fermentado de los rarámuris. Spencer logró obtener una olla tesgüinera de la bisabuela Celado; sin embargo, a Paulita no le tocó aprender a prepararlo. Ellasehabíacriadoenotracasay,paraentonces,aquelerauno昀椀cio extinto. Así, puede decirse que Juan proviene de dos familias con raíces en las artes y o昀椀cios tradicionales y, quizá, en su sangre aún persistía esa pulsión de los genes por crear con las manos. Buscar leña, traer miel silvestre, cortar quiotes y asarlos eran tareas que Juan llevaba a cabo en esos años tempranos para ayudar al sostén de su familia, ya sea para compartir los alimentos a la hora de la comida o para venderlos y obtener unos pesos. Sin embargo, a Juan no lo motivaba únicamente la necesidad económica. Cuando no se quedaba en casa obsesionado por una nueva pintura o labor artística, iba a caminar por los pastizales, subía los cerros, cuidaba las vacas de la familia, se dejaba llevar por senderos antiguos y descubría nuevos lugares. Él amaba el campo, era el lugar en donde más cómodo se sentía.

Years later, Doña Paulita would recall that, on her mother’s side, her older sister, grandmother, and great-grandmother, among others had been potters. Juan traveled to San Lorenzo with Spencer MacCallum –his patron and mentor– in search of these roots. He discovered that until the early 20th century, this had been a pottery town where women worked with clay, making utilitarian pots for brewing tesgüino, the fermented corn drink of the Rarámuri. Spencer managed to obtain a tesgüinera pot from Paulita’s great-grandmother, though Paulita never learned to make pottery. She had grown up in another household, and by then, the trade had become extinct. Thus, it can be said that Juan comes from two families with roots in traditional arts and crafts, and perhaps the urge to create with his hands still lingered in his genes.

Fetching 昀椀rewood, gathering wild honey, cutting and roasting agave 昀氀ower stalks were tasks Juan performed in those early years to help support his family, either sharing the food at mealtime or selling them to earn a few pesos. But Juan was not solely motivated by economic necessity. When he wasn’t home, obsessed with a new painting or artistic project, he walked through pastures, climbed hills, and tended to the family’s cows. He followed ancient trails and discovered new places. He loved the countryside; it was where he felt most comfortable.

Cerro “Moctezuma”, o “montezuma”, como llaman los locales a casi todos los yacimientos arqueológicos. Cerro “Moctezuma”, or Montezuma, as the locals pronounce and identify archaeological sites.

Adquirió conocimientos explorando las cuevas, observando los tepalcates en los «montezumas» (como conocen localmente a los sitios prehispánicos), encontrando puntas de 昀氀echa y reproduciéndolas para entender cómo se usaban. En la «piel» de las antiguas ollas o en los vestigios de estas y en petroglifos, encontraba espirales, escalones, retículas ajedrezadas. Toda esta obsesión tenía su raíz en la intención de querer saber más sobre sus antepasados y su forma de vida.

Sobre ese día a día que le tocaba enfrentar para «vivir de algo», Juan relató en muchas ocasiones que se iba con las bestias por la sierra y las cargaba. Mientras comían y descansaban una o dos horas, él se metía en las cuevas. Allí encontraba «ollas bien bonitas. Unas completas y otras pegadas. Traje unas para acá y alguien me dijo: “¡Unas ‘ollas pintas’!”. Había una creencia de que durante la Semana Santa los tesoros se abrían. Yo, que estaba chavalo, oía que los sacaban de las ‘ollas pintas’, pero algunas tenían esqueletos en vez de tesoros, así que no todos se animaban». El hallazgo en una de las cuevas fue particularmente memorable. Juan tendría unos 15 años. Se encontraba cubierta con una piedra y al removerla se quedó asombrado. Contenía los esqueletos momi昀椀cados de una pareja y algunas ollas colocadas en diferentes puntos. A sus pies había cinco ollas y otras vasijas utilitarias con restos de frijoles, calabaza, raíces y otros alimentos. Sin embargo, dos más destacaban por su tamaño y decoración, una blanca y otra amarilla. (Samuelson, 2023, p. 176). Piezas cuyabellezaloimpactaronmásquecualquierotra.«Entoncesno tenía decidido que a esto iba a dedicarme –recuerda Juan–. No pensaba en las ollas, ni siquiera las conocía… Como los dibujos mefascinaron,pensé:“Tengoquehaceralgocomoesto”.Notenía la intención de vivir de ello, nada más quería hacer una olla». Alguna vez llevó a sus hijos por aquellas veredas, quería que supieran por dónde su padre había atravesado la sierra. Su intención era que vieran dónde había nacido su vocación.

He acquired knowledge by exploring the caves, observing the tepalcates or artifacts in “Montezumas” (as locals call pre-Hispanic sites), 昀椀nding arrowheads, and replicating them to understand their use. On the surface of ancient pots or the remains of these and petroglyphs, he found spirals, step-frets, and checkered grids. This obsession stemmed from his desire to learn more about his ancestors and their way of life.

Regarding the daily challenges he faced to “make a living,” Juan often recounted that he would wander the mountains with his loaded pack animals. While they grazed and rested for an hour or two, he would go and explore the caves. There he would 昀椀nd “beautiful pots –some intact and others pieced together. I brought some of them back and someone exclaimed: “Some ‘ollas pintas’!” or painted pots. There was a belief that during Holy Week the treasures were revealed. As a kid, I heard that they were taken out of the ‘ollas pintas’, but some had skeletons instead of treasures, so not everyone dared to open them”.

One particularly memorable discovery in a cave occurred when he was about 15 years old. It was covered with a stone and when he removed it, he was astonished. It contained the mummi昀椀ed skeletons of a couple and some pots placed at di昀昀erent points. At their feet were 昀椀ve pots and other utilitarian vessels with remnants of beans, squash, roots, and other foods. However, two stood out for their size and decoration, one white and the other one yellow. (Samuelson 2023: 176) Pieces which beauty impressed him more than anything else. “At that point I had not decided that this was what I was going to do,” recalls Juan. I didn’t think about the pots, I didn’t even know them... As the drawings fascinated me, I thought, ‘I have to do something like this.’ I didn’t intend to make a living from it, I just wanted to make one.”

He once took his children along those trails, wanting them to see where his vocation was born.

(COMO CONOCEN LOCALMENTE A LOS SITIOS PREHISPÁNICOS), ENCONTRANDO PUNTAS DE FLECHA Y REPRODUCIÉNDOLAS PARA ENTENDER CÓMO SE USABAN.

He acquired knowledge by exploring the caves, observing the tepalcates or artifacts in “Montezumas” (as locals call pre-Hispanic sites), 昀椀nding arrowheads, and replicating them to understand their use.

Cueva de la olla. En sitios como este suelen encontrarse vestigios de vasijas con restos humanos. Cave of la Olla or Pot. In sites like this one, vestiges of pots with human remains are often found.

EL PASADO NUTRE UNA CURIOSIDAD NATA

The Past Nurtures Innate Curiosity

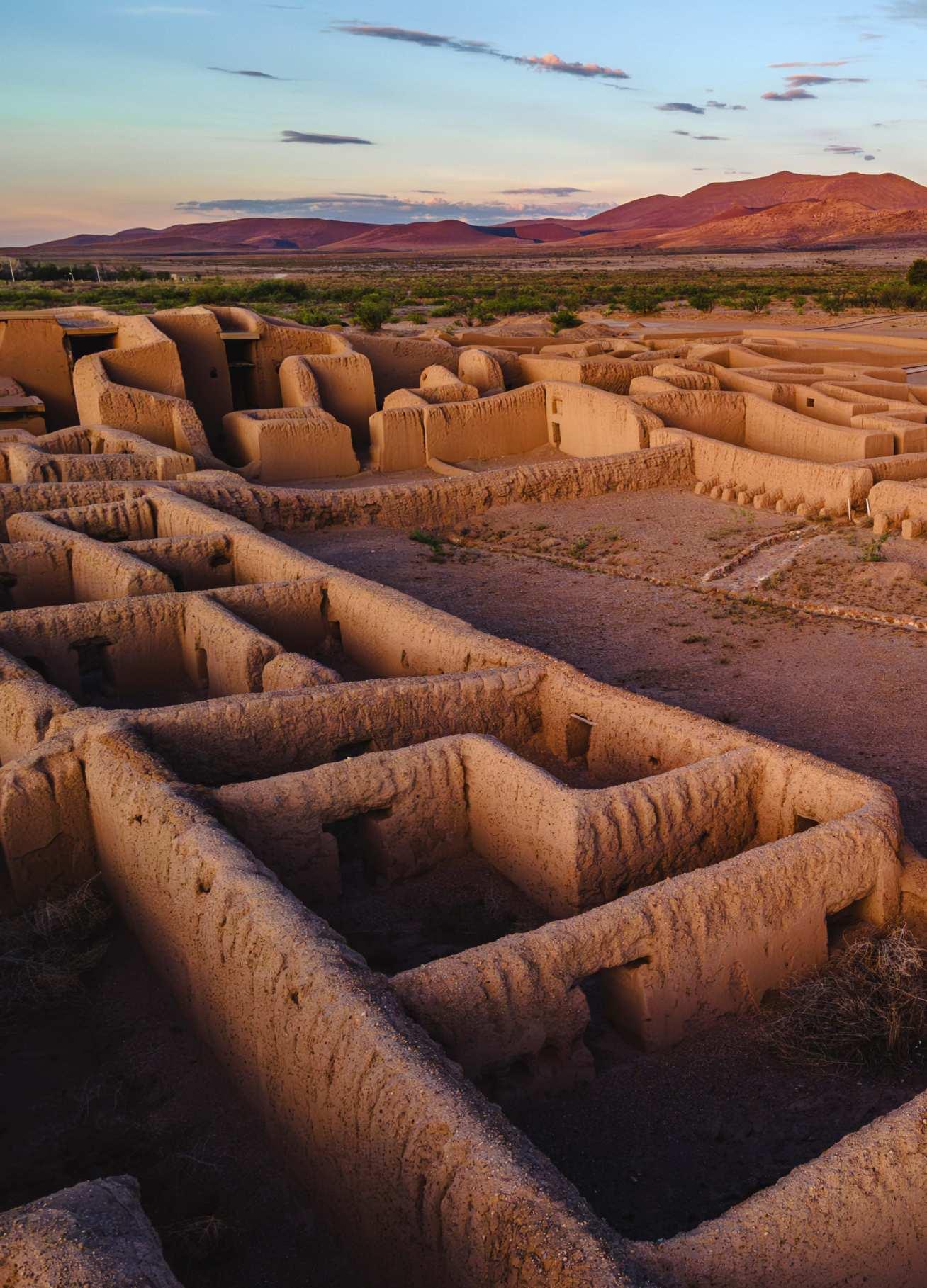

Paredesdetierraapisonadaselevantandesdeelsuelo.Suintenso color café rojizo se funde con el horizonte y a la vez contrasta con el azul del cielo. Al pie de la Sierra Madre Occidental, a 240 kilómetros al noreste de la ciudad de Chihuahua, se ubican los vestigios de la ciudad más grande e importante de la zona. Para algunos autores, esta región corresponde a la Gran Chichimeca; para otros, es un sitio destacado de Oasisamérica. Paquimé (“Casas Grandes” en lengua ópata) es una zona arqueológica cuyo territorio comprende 146 hectáreas. En su apogeo, tan solo la ciudad cubría 750 kilómetros cuadrados. Su posición entre ríos fue estratégica para propiciar su desarrollo en un entorno agreste. Situada en la cabecera del río Casas Grandes, al norte del río Palanganas, al este del río Santa María y el río Carmen, estas «arterias de vida» –como las nombra Eduardo Pío Gamboa– fueron aprovechadas de manera estratégica por un sistema de aprovisionamiento hídrico.

Persisten varios enigmas e hipótesis que los arqueólogos han desarrollado en torno a la caída de esta cultura. ¿Qué provocó el abandono de Paquimé? Desde que el doctor Charles Di Peso inició excavaciones cientí昀椀cas en 1958, distintos aspectos de su organización social han causado admiración; en particular, la cerámica que destaca por su fuerza expresiva. Concebirla como pieza de un rompecabezas más amplio de la tradición alfarera prehispánica de la cultura pueblo puede ayudar a su comprensión.

Walls of packed earth rise from the ground. Their intense reddish-brown color blends with the horizon and contrasts with the blue sky. At the foot of the Sierra Madre Occidental, 240 kilometers northeast of Chihuahua City, lie the remains of the largest and most important city in the area. For some authors, this region corresponds to the Great Chichimeca; for others, it is a prominent site of Oasisamerica. Paquimé (known as “Casas Grandes” in the Ópata language) is an archaeological zone covering 146 hectares. At its peak, the city alone covered 750 square kilometers. Its position between rivers was strategic for promoting development in a rugged environment. Located at the headwaters of the Casas Grandes River, north of the Palanganas River, east of the Santa María River and the Carmen River, these “arteries of life” –as Eduardo Pío Gamboa calls them– were strategically used by a water supply system.

Several enigmas and hypotheses were developed by archaeologists surround the decline of this culture. What caused the abandonment of Paquimé? Since Dr. Charles Di Peso began scienti昀椀c excavations in 1958, di昀昀erent aspects of its social organization have caused admiration; in particular, its pottery which stands out for its expressive strength. Conceiving it as a piece of a larger puzzle of the pre-Hispanic pottery tradition of the Pueblo culture can aid in its understanding.

Las puertas ‘T’ son características de la zona arqueológica de Paquimé. ‘T’ shaped doors are a characteristic feature in the archaeological site of Paquime.

Con decoración que representa los granos de maíz, esta es una de las piezas encontradas en Paquimé. Decorated with designs that represent corn kernels, this pot was found in Paquimé.

Oasisamérica

UN ENIGMA CULTURAL

Oasisamerica, A Cultural Enigma

Una región que se extendía por el suroeste de Estados Unidos y el norte de México fue hogar de grupos sedentarios agrícolas. Este territorio, que formó parte de la zona áridoamericana durante milenios, albergó a grupos nómadas de cazadores-recolectores. El surgimiento de culturas sedentarias fue posterior al de Mesoamérica y comenzó en los siglos previos a nuestra era. Oasisamérica engloba cuatro grandes culturas notables: anasazi, hohokam, mogollón y Casas Grandes. A region extending across the southwestern United States and northern Mexico was home to sedentary agricultural groups. This territory, which was part of the Aridoamerica region for millennia, was home to nomadic hunter-gatherer groups. The emergence of sedentary cultures followed that of Mesoamerica and began in the centuries before our era. Oasisamerica encompasses four major notable cultures: Anasazi, Hohokam, Mogollon, and Casas Grandes.

ANASAZI

(100 a. C. - 1300 d. C.)

De voz navajo que signi昀椀ca ‘antiguos enemigos’, la cultura anasazi fue un pueblo que ocupó durante al menos trece siglos las mesetas y valles de los estados de Colorado, Nuevo México, Arizona y Utah, en Estados Unidos. Sus casas en acantilados fueron edi昀椀cadas con piedra, lodo y troncos. Las ruinas de Mesa Verde, en Colorado, son un ejemplo de sus sistemas constructivos y organización urbanística. La cerámica anasazi se transformó a través de sus distintos periodos, hasta 昀氀orecer en piezas con llamativos diseños geométricos en negro sobre fondo blanco o rojo. Los sitios anasazi comenzaron a ser abandonados en torno al 1300 d. C., sin que se conozca el motivo.

From the Navajo word meaning ‘ancient enemies,’ the Anasazi culture was a people who occupied the valleys and plateaus of the U.S. states of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah for at least thirteen centuries. Their cli昀昀 dwellings were built of stone, mud, and logs. The ruins of Mesa Verde –in Colorado– exemplify their construction systems and urban planning. Anasazi pottery evolved through various periods, culminating in pieces with striking geometric designs in black on white or red backgrounds. The Anasazi sites began to be abandoned around 1300 A.D., with the reason still unknown.

HOHOKAM

(450 d. C. - 1450 d. C.)

Su nombre en lengua pima signi昀椀ca ‘los que se fueron’. Los hohokam, hábiles agricultores en el desierto, desarrollaron un sistema de canales de riego para llevar agua de río a zonas de cultivo, en donde sembraban maíz, variedades de frijol, calabazas y algodón. Se asentaron en el territorio que hoy conforma Arizona, sobre todo en el área de Phoenix. Los remanentes más importantes de esta cultura son fragmentos de cerámica de color beige y café, con iconografía de motivos animales, humanos y geométricos, plasmados en tonos rojos y negro; sin embargo, también se han hallado restos de cerámicas de culturas vecinas, indicio de su interacción e intercambios comerciales con ellas. Uno de los vestigios más importantes de su arquitectura es el sitio de Casa Grande, en Arizona.

MOGOLLÓN

(200 d. C. - 1450 d. C.)

En la región montañosa de Nuevo México, Arizona, Chihuahua y Sonora se desarrolló la cultura mogollón. Los integrantes de este pueblo al principio eran recolectores móviles, después comenzaron a incursionar en la agricultura y eso los llevó a asentarse en lugares 昀椀jos y a construir extensas instalaciones de riego. Aunque su alimentación se basaba en la cosecha de maíz, frijoles y calabazas, ellos también dependían de la caza. La primera tipología arquitectónica de los mogollón se re昀椀ere a las casas pozo, en las cimas de los cerros. Alrededor del año 550 d. C., las casas pozo comenzaron a erigirse en llanuras aluviales. Posteriormente, alrededor del año 1000 d. C., empezaron a construirlas con piedra y adobe en acantilados. Las Casas del Acantilado de Gila en el suroeste de Nuevo México son ejemplo de ello.

MIMBRES

(825 d. C. - 1450 d. C.)

La subcultura mimbres, derivada de los mogollones, se desarrolló en la ribera del río Mimbres en el suroeste de Nuevo México. Destacó por su cerámica blanca con decoración negra. Esta etnia se expandióhastaelnortedeChihuahua.SegúnPíoGamboa,lain昀氀uencia de la alfarería mimbres impactó ampliamente en la región de Casas Grandes en la producción de ollas polícromas. Se cree que algunos de los alfareros mimbres comenzaron un intercambio con lacultura CasasGrandesenelsigloXIIyquesutrabajoin昀氀uyómás tarde en los artí昀椀ces de esta cultura emergente. De acuerdo con Richard D. O’Connor y Walter P. Parks, Juan Quezada respaldó esta teoría.Basándoseensusobservaciones,paraJuanlosprimerospobladoresanterioresaPaquiméeranmimbreños.

(450 A.D. – 1450 A.D.)

Their name in the Pima language means ‘those who left’. The Hohokam were skilled desert farmers who developed an intricate system of irrigation canals to channel river water to their cultivated 昀椀elds where they grew corn, varieties beans, squash, and cotton. They settled in the region that is now Arizona, particularly around the Phoenix area. The most signi昀椀cant remnants of this culture are fragments of beige and brown ceramics decorated with animal iconography, human 昀椀gures, and geometric motifs, painted in red and black tones. Potsherds from neighboring cultures have also been discovered, indicating their interactions and trade with other groups. One of the most important architectural remnants is the Casa Grande site in Arizona.

(200 A.D. – 1450 A.D.)

The Mogollon culture emerged in the mountainous regions of New Mexico, Arizona, Chihuahua, and Sonora. Initially, they were nomadic gatherers, but they gradually transitioned to agriculture, leading to permanent settlements and the construction of extensive irrigation systems. Although their diet was based on the harvest of corn, beans, and squash, they also depended on hunting. Early Mogollon architecture consisted of “Casa Pozos” –partial subterranean houses– built on hilltops. Around 550 A.D., they extended these constructions to alluvial plains, and by 1000 A.D., they erected stone and adobe dwellings on cli昀昀s, such as The Gila Cli昀昀 Houses in southwestern New Mexico.

(825A.D.–1450A.D.)

The Mimbres subculture, derived from the Mogollón people, 昀氀ourished on the banks of the Mimbres River in southwestern New Mexico. They were renowned for their white pottery with black decoration.ThisethnicgroupexpandedtothenorthofChihuahua. According to Pío Gamboa, Mimbres pottery had a signi昀椀cant in昀氀uence on the Casas Grande region, particularly in the production ofpolychromepots.ItisbelievedthatsomeMimbrespottersbegan an exchange with the Casas Grandes culture in the 12th century, in昀氀uencing the local craftsmen and their culture. According to Richard D. O’Connor and Walter P. Parks, Juan Quezada supported thistheory.Basedonhisobservations,the昀椀rstsettlersbeforePaquiméwereMimbrepeople.

CASAS GRANDES

La cultura Casas Grandes prosperó en los territorios que hoy comprenden los estados mexicanos de Sonora y Chihuahua, abarcando también Arizona y Nuevo México en Estados Unidos. Si bien la periodización de esta presenta variaciones en función del autor, Whalen y Minnis (2009) conciben dos periodos de ocupación, nombrados Viejo (700 - 1200 d. C.) y Medio (1200 - 1450 d. C.). Se considera el 1200 d. C. del Periodo Medio Temprano como su etapa de mayor 昀氀orecimiento, al convertirse en el centro de intercambio cultural y comercial de bienes con un valor simbólico, prácticas culturales entre diversas civilizaciones situadas en el suroeste de Estados Unidos y noroeste de México, extendiéndose hasta Mesoamérica.

Estas son las zonas de in昀氀uencia de las subculturas y su ocupación territorial. These are the areas of in昀氀uence of the subcultures and their territorial occupation.

En la arquitectura, se implementó el uso de la piedra. Sus edi昀椀caciones se caracterizaban por su altura, compuestas por hasta cuatro pisos, con puertas `T´ dispuestas alrededor de amplias plazas pavimentadas.

Del sur llegó la práctica del juego de pelota. Manifestaciones como la joyería incorporaron materiales traídos de otras latitudes, como el cobre posiblemente de Michoacán, las conchas del mar de Cortés y la turquesa de Nuevo México y Arizona, misma que fue ampliamente distribuida hacia Oaxaca y el centro de México. Sin embargo, sería su cerámica la que alcanzaría mayor plenitud.

El arqueólogo Jesús Narez apunta que en el Periodo Medio Tardío (1200 d. C. a 1340 d. C.) se percibe decadencia y propone como sus posibles causas factores diversos, como sequías prolongadas, plagas, enfermedades e invasiones.

The Casas Grandes culture thrived in the areas now comprising the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua, as well as parts of Arizona and New Mexico in the United States. The periodization of this culture varies among scholars. Whalen and Minnis (2009) identify two periods: Old (700–1200 A.D.) and Middle (1200–1450 A.D.). The culture reached its peak during the Early Middle Period (1200 A.D.), becoming a center for cultural and commercial exchange with high symbolic value, interacting with various cultures in the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico, extending into Mesoamerica. Their architecture incorporated the use of stone, with buildings up to four stories high featuring ‘T’ shaped doorways arranged around large paved central courtyards.

From the south came the practice of the Mesoamerican ball game. Jewelry incorporated materials from distant regions, such as copper possibly from Michoacán, shells from the Sea of Cortez, and turquoise from New Mexico and Arizona, widely distributed to Oaxaca and central Mexico. However, it was their pottery that reached the highest level of artistic expression.

Archaeologist Jesús Narez notes a decline in the Late MiddlePeriod(1200A.D.–1340A.D.),suggestingpossiblecauses such as prolonged droughts, plagues, diseases, and invasions.

Primeras

exploraciones

First Explorations

En 1884, el antropólogo suizo Adolph Bandelier comenzó «la exploración de un antiguo pueblo que había dejado su impronta por doquier». A Bandelier le precedió Francisco de Ibarra, explorador español que en 1562 lo describió así: «Un lugar con casas de mucha grandeza, altura y fortaleza, de seis a siete pisos, con grandes patios engalanados y bien forti昀椀cados para su amparo y defensa; con grandes piedras que sostienen altos pilares de robusta madera que parecen haber venido de lejos. Profundos fogones en sus casas por temor al frío que de las altas sierras baja, largos caminos y canales empedrados, altos muros colapsando que revelan el deterioro».

In 1884, the Swiss anthropologist Adolph Bandelier began “the exploration of an ancient town that had left its mark everywhere”. BandelierwasprecededbyFranciscodeIbarra,aSpanishexplorer who,in1562,describeditas“Aplacewithhousesofgreatgrandeur, height, and strength, six to seven stories high, with large, decorated andwell-forti昀椀edcourtyardsforshelteranddefense;withlargestones supporting tall pillars of sturdy wood that seem to have come from afar. Deep 昀椀replaces in their houses for fear of the cold that comes down from the high sierras, long cobblestone roads, and canals, high collapsing walls that reveal the deterioration”.

Estas rocas funcionaban como tapas de las jaulas de las guacamayas. These rocks functioned as lids for the macaws’ cages.

Casi 400 años después de Ibarra, el arqueólogo estadounidense Charles Di Peso, en colaboración con Eduardo Contreras (del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia), encabezó la primera expedición de campo, entre 1958 y 1961. Las investigaciones se plasmaron en ocho volúmenes titulados Casas Grandes: un centro comercial caído de la Gran Chichimeca

Uno de los rasgos que ha llamado poderosamente la atención es la existencia de cincuenta y seis jaulas de adobe con sistema de calefacción para mantener confortable a la población de la imponente guacamaya escarlata (Ara macao), así como los restos de casi trescientas aves. Sus plumas iridiscentes amarillas, rojas y azules habían sido veneradas por numerosos grupos mesoamericanos desde 1000 a. C. Para el caso de Paquimé y otros sitios cercanos, un estudio isotópico de oxígeno y carbón realizado a los huesos, publicado en 2010, identi昀椀có que la distribución geográ昀椀ca incluía desde el sur de Tamaulipas –a 500 kilómetros de Paquimé– hasta la zona maya y que habían logrado su traslado, reproducción en cautiverio y alimentación con maíz.

Entre otros numerosos descubrimientos, el equipo halló evidencias con motivos de serpientes emplumadas de origen mesoamericano, mosaicos con múltiples baldosas de turquesa en combinación con otros materiales, como la hematita y el cobre. Destacó una larga pared ondulada con forma de serpiente que culminaba en una cabeza con un prominente cuerno o penacho.

El doctor R. B. Brown, representante del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, a cargo de Paquimé en la década de los 80, describió a Casas Grandes así: «Un rompecabezas tridimensional al que le faltaba 90% de las piezas». Los antropólogos se preguntan qué sucedió con los sobrevivientes que alguna vez habitaron Paquimé. Di Peso sugiere que podrían haberse convertido en los rarámuris (que durante mucho tiempo fueron nombrados tarahumaras), una etnia que ahora reside en distintas latitudes a lo largo de la Sierra Madre. Otros sostienen que los ópatas podrían ser sus descendientes, una sociedad que se encuentra en alto riesgo de desaparición. El misterio persiste.

Almost 400 years after Ibarra, American archaeologist Charles Di Peso, in collaboration with Eduardo Contreras (of the National Institute of Anthropology and History), led the 昀椀rst 昀椀eld expedition, between 1958 and 1961. The research resulted in eight volumes entitled Casas Grandes: A Fallen Commercial Center of the Great Chichimeca.

One remarkable feature of Casas Grandes is the existence of 昀椀fty-six adobe cages with heating systems to keep the tropical scarlet macaws (Ara macao) comfortable, along with the remains of nearly three hundred birds. Their iridescent yellow, red, and blue feathers had been revered by numerous Mesoamerican groups since 1000 B.C and in the case of Paquimé and other nearby sites, an oxygen and carbon isotopic study of the bones, published in 2010, identi昀椀ed that the geographic distribution initiated from the south of Tamaulipas -500 kilometers from Paquimé- to the Mayan area and that they had been transported, bred in captivity and fed with corn.

Among numerous other discoveries, the team found evidence with feathered serpent motifs of Mesoamerican origin, mosaics with multiple turquoise tiles in combination with other materials, such as hematite and copper.

Ofparticularnotewasalongundulatingwallintheshapeof a serpent culminating in a head with a prominent horn or plume.

Dr. R. B. Brown, a representative of the National Institute of Anthropology and History and in charge of Paquimé in the 1980s, described Casas Grandes as follows: “A three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle with 90% of the pieces missing”. Anthropologists wonder what happened to the survivors who once inhabited Paquimé. Di Peso suggests they may have become the Rarámuris (long known as Tarahumara), an ethnic group now residing at di昀昀erent latitudes along the Sierra Madre. Others argue that the Ópatas could be their descendants, a culture currently at high risk of disappearing. The mystery persists.

QUÉ SUCEDIÓ CON LOS SOBREVIVIENTES QUE ALGUNA VEZ HABITARON PAQUIMÉ.

DI PESO SUGIERE QUE PODRÍAN HABERSE CONVERTIDO EN LOS RARÁMURIS.

Anthropologists wonder what happened to the survivors who once inhabited Paquimé. Di Peso suggests they may have become the Rarámuris.

En el centro de la imagen una hilera de muros pequeños, son los restos de las jaulas de las guacamayas. At the center of the image a row of small enclosures; these are the remains of the macaws’ cages.

La olla que tardó quince años

The Pot That Took Fifteen Years

Juan se había obsesionado con hacer una olla. «Una olla», se repetía. La que fuera, sin importar el tiempo que llevara. Desde 1955 y hasta 1970 demoró para lograr algún nivel de satisfacción que, visto a la distancia, aún era bastante rústico. Entre los quince y treinta años de vida, Juan experimentó a ratos, entre un trabajo y otro. Además, cuando en 1964 se casó con Guillermina Olivas Reyes, con quien procreó ocho hijos, sus tiempos libres se vieron menguados.

Coinciden su hijo Noé y su hermana Lidia en que durante esos años, Juan hacía de todo para sobrevivir. Era jornalero y buscaba trabajo en los alrededores, en el corte de frijol, las labores de campo, lo que encontrara. También preparaba dulces, palomitas, jamoncillos, «duros» (frituras de harina). «Y hacía de todo para salir adelante, pero no podía. Entonces se juntaba con dos o tres amigos y “vámonos pa’ Estados Unidos, de mojados”». En el ferrocarril también probó suerte: trabajaba en las obras de modernización realizadas entre Mata Ortiz y Ciudad Juárez. Allí vio que el paisaje y la estratigrafía de los cerros eran parecidos, era la misma sierra. Dedujo que todo lo que necesitaba para

Juan had become obsessed with making a pot. “One pot” he kept repeating to himself –whatever it took, no matter how long. It took him from 1955 until 1970 to achieve some level of satisfaction that, seen from a distance, was still quite rustic. Between the ages of 昀椀fteen and thirty, Juan experimented o昀昀 and on, between one job and another. In addition, in 1964, when he married Guillermina Olivas Reyes, and he had eight children, his free time was further reduced.

His son Noé and his sister Lidia agree that during those years Juan did everything to survive. He was a day laborer and looked for work in the surrounding area, cutting beans, working in the 昀椀elds, whatever he could 昀椀nd. He also made candy, popcorn, milk and sugar sweets, “duros” (fried 昀氀our snacks).

“He did everything he could to get ahead, but he couldn’t,” Noé recalls. “So, he would get together with two or three friends and say, ‘Let’s go to the United States as ‘wetbacks.’” He also tried his luck on the railroad, working on modernization projects between Mata Ortiz and Ciudad Juárez. There, he saw that the landscape and the stratigraphy of the hills were similar, it

El periodo temprano de Juan Quezada, antes de su relación con Spencer, también es motivo de estudio. Piezas de la colección de Richard y Joan O’Connor. Early pre-Spencer pieces are also a subject of study. Pots from the Richard and Joan O’Connor collection.

hacer “esa olla” debía estar en su entorno, tanto los materiales como las herramientas. Sin embargo, ¿por dónde empezar?

Juan «nunca había visto a un alfarero», así es que empezó «experimentando con el barro, la pintura, la quemada, los pinceles». Se regodeaba con el recuerdo: «Tan solo con los pinceles probé con plumas de todas las aves, pelos de todos los animales. Era una guerra que yo “traíba” dentro. Aprendí a dominar el barro, la pulida, la arreglada y todo eso».

El proceso cerámico implica de nueve a diez pasos. Cada uno de ellos conlleva una combinación de materiales y procedimientos hasta conseguir una obra terminada. Un error invisible desde el comienzo, una burbuja de aire o un descuido pueden destruir semanas de trabajo. Finalmente, la cerámica tiene mucho de química y física aplicadas. Juan no sabía nada de eso.

La obsesión iba acompañada de cierta tenacidad, nunca se dio por vencido. Los avances, aun pequeños o insigni昀椀cantes, eran un aliciente. Por ello, compartía equilibradamente el tiempo dedicado a la alfarería con diversas actividades económicas para sostener a su familia.

was the same Sierra. He deduced that everything he needed to make “that pot” had to be in his environment, both the materials and the tools. However, where to start?

Juan “had never seen a potter before”, so he started “experimenting with the clay, the paint, the 昀椀ring, the brushes”. He reveled in the memory: “Just with the brushes I experimented with feathers from all birds, hairs of all animals. It was like a war that stirred within me. I learned to master the clay, the burnishing, the re昀椀ning, and all that”.

The ceramic process involves nine to ten steps. Each step demands a combination of materials and processes until a 昀椀nished work is achieved. An invisible mistake at the beginning, an air bubble, or an oversight can destroy weeks of work. Finally, ceramics has a lot of applied chemistry and physics. Juan knew none of that.

The obsession was paired with a remarkable tenacity; he never gave up. Even the smallest progress served as an incentive. Consequently, he balanced his time between pottery and various economic activities to support his family

A PRUEBA Y ERROR

Trial and Error

Recorramos el camino andado por Juan a través de los recuerdos de Noé, su hijo, y de algunas precisiones del profesor Julián Hernández Chávez, maestro y ceramista autodidacta de la región, quien produjo una obra de divulgación llamada La nueva cerámica de Paquimé, 2009. En ella sintetiza los pasos fundamentales del proceso.

Let us retrace Juan’s journey through the memories of his son Noé, and the insights of Professor Julián Hernández Chávez, a schoolteacher and self-taught ceramist from the region. Professor Hernández Chávez documented the process in his informative work, La nueva cerámica de Paquimé (2009), where he outlines the fundamental steps involved.

El barro, la materia prima del o昀椀cio

Clay: The Raw Material of the Craft

En la naturaleza hay cientos de materiales y minerales por doquier. Identi昀椀car el elemento barro o arcilla representó el primer gran paso de Juan. Son tierras plásticas con diferentes presentaciones, texturas, colores y dureza. El valle del río Casas Grandes y sus a昀氀uentes, como el Palanganas y el Piedras Verdes, son ricos en barreales casi a 昀氀or de tierra o cerca de nacimientos de agua. Buscando el color amarillo o bayo, por ser el más común en las ollas y tepalcates de Paquimé, Juan encontró su primer barro por la ex Hacienda de San Diego, en un arroyo olvidado. Pensó que entre más puro el barro, sería mejor, pero se quebraba. Buscar, hallar y probar varios de diversos colores –gris, rojo, rosa, violáceo y morado, entre otros–, se convirtió en una de sus pasiones. Encontrar un lodo blanco de alta calidad también fue una de sus prioridades para sustituir la necesidad de usar un engobe o recubrimiento de otro color sobre arcilla. Juan había notado que –a sus ojos– las ollas prehispánicas de mayor calidad, decoración y belleza estaban hechas de arcilla blanca. El hecho es que este material no solo es escaso, sino también muy caprichoso por rígido y quebradizo. Dado el efecto dramático del contraste del barro blanco con los diseños negros y rojos, se convirtió en uno de los tonos favoritos no solo de los Quezada, también de los ceramistas del trabajo más 昀椀no. Conseguirlo implicaba un mundo de complicaciones.

In nature, there are hundreds of materials and minerals everywhere. Identifying the element –clay– represented Juan’s 昀椀rst big step. These are plastic clays with di昀昀erent presentations, textures, colors, and hardness. The valley of the Casas Grandes River and its tributaries, such as the Palanganas and Piedras Verdesrivers,arerichinclayeysoils,almostatthesurfaceornearwatersources.Lookingfortheyelloworbaycolor,asitismostcommonly found in the pots and potsherds of Paquimé, Juan found his 昀椀rst clay by the former Hacienda de San Diego, in a forgotten stream. He thought the purer the clay, the better, but it was brittle. Searching, 昀椀nding, and testing various colors –grey, red, pink, violet, and purple, among others– became one of his passions. Finding high-quality white clay was also one of his priorities to avoid the need for a slip or coating of another color on clay.

For Juan, the pre-Hispanic pots of the highest quality, decoration, and beauty were made of white clay. The fact is that this material is not only scarce but also very willful because it is rigid and brittle. Given the dramatic e昀昀ect of the contrast of the white clay with the black and red designs, it became a favorite color not only of the Quezada family but also of the ceramists doing the 昀椀nest work. Achieving it involved a world of complications.

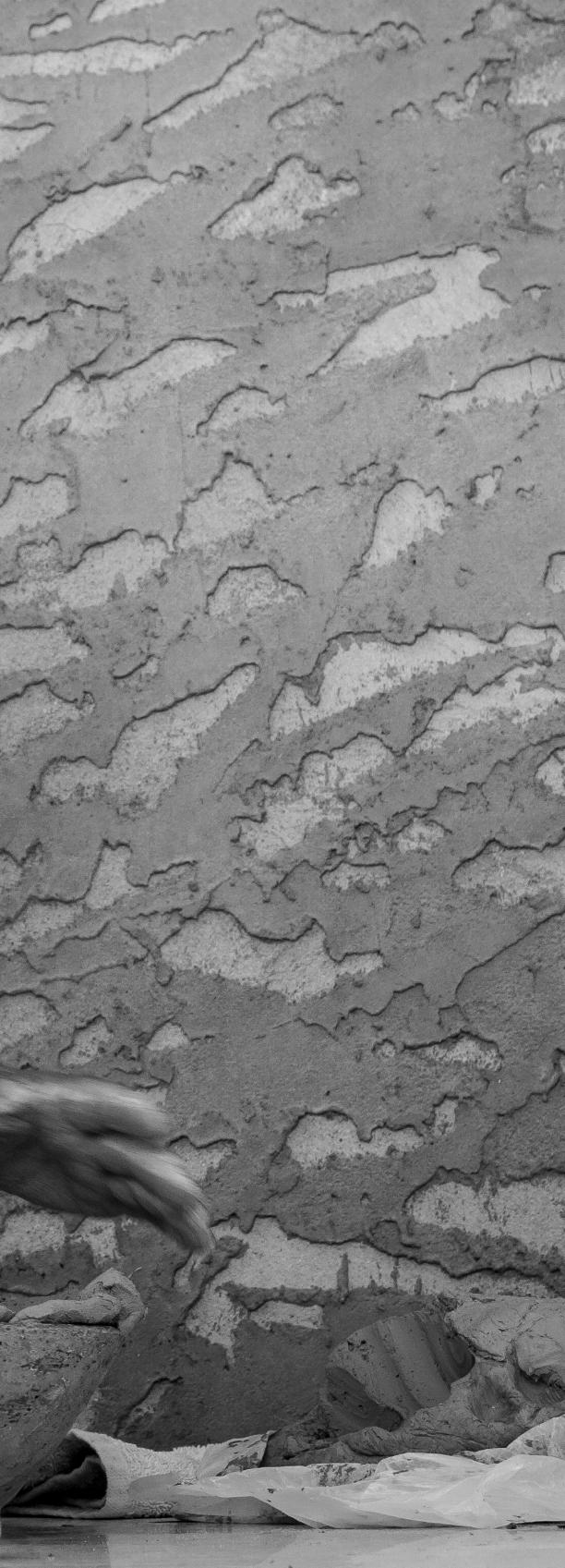

Trabajar la pieza

Working the Piece

Juan Quezada batalló para levantar una vasija. En muchas culturas las piezas se forman con rollos de arcilla. Su mirada se posó sobre diversos cuencos antiguos, que no eran tan planos como un plato ni tan profundos como un tazón, sino más gruesos y sin decoración. Eso sí, pulidos por dentro. Se preguntó si eran una especie de molde. Así fue cómo descubrió lo que se conoce como puki, palabra en idioma téwa que describe una base para moldear. La tortilla amasada se colocaba dentro del molde; sin embargo, para lograr la altura deseada tenía que agregar varios rollos, tirando de la orilla hacia arriba. Debía girarla lentamente para que fuese simétrica. Al utilizar ambas manos, una sostenía la pared y la otra trabajaba en dirección opuesta. Diferentes herramientas, desde una segueta hasta la tapa de una lata, le sirvieron para raspar y alisar la olla por dentro y por fuera, así como para rebajar su grosor. Uno de los aspectos más sorprendentes de las delicadas ollas de Mata Ortiz es su liviandad, resultado de adelgazar la estructura al máximo posible. El profesor Hernández Chávez recuerda que, para 昀椀nalizar esta actividad, es necesario desmoldar la olla del puki y dejarla secar muy bien durante varios días y a la sombra. El clima in昀氀uye bastante: «Hay que tener especial cuidado en el secado, ya que como se dice entre alfareros: “El barro se mueve mucho de mojado a seco”. Hay barros que encogen hasta 15% en este proceso». (Hernández Chávez, 2009, p. 40).

Juan Quezada struggled to hand–build a vessel. In many cultures, the pieces are formed from coils of clay. His gaze rested on several ancient bowls, which were neither as 昀氀at as a plate nor as deep as a bowl; they were thicker and undecorated. They were, however, burnished on the inside. He wondered if they were some kind of mold. That is how he discovered what is known as puki, a word in the Tewa language that describes a base for molding. The kneaded “tortilla” or a 昀氀at, circular piece of clay used as a base to start forming a pot was placed inside the mold; however, to achieve the desired height he had to add several rolls, pulling the edge upwards. He had to turn it slowly so that it was symmetrical. Using both hands, one hand held the wall while the other worked in the opposite direction. Di昀昀erent tools, from a hacksaw to the lid of a tin can, were used to scrape and smooth the inside and outside of the pot, as well as to reduce its thickness. One of the most surprising aspects of Mata Ortiz’s delicate pots is their lightness, the result of thinning the structure as much as possible. Professor Hernández Chávez reminds us that, to 昀椀nish this activity, it is necessary to remove the pot from the puki and let it dry very well for several days in the shade. The climate has a signi昀椀cant in昀氀uence: “Special care must be taken in the drying process, because as they say among potters: ‘The clay moves a lot from wet to dry’. There are clays that shrink up to 15% in this process”.

UNO DE LOS ASPECTOS MÁS SORPRENDENTES DE LAS DELICADAS OLLAS DE MATA ORTIZ ES SU LIVIANDAD, RESULTADO DE ADELGAZAR LA ESTRUCTURA AL MÁXIMO POSIBLE.

One of the most surprising aspects of Mata Ortiz’s delicate pots is their lightness, the result of thinning the structure as much as possible.

Lijar y pulir

Sanding

and Burnishing

En aras de lograr una super昀椀cie más tersa, en Mata Ortiz se realizan dos pasos intermedios que desarrolló Juan: el uso de una o varias lijas 昀椀nas para eliminar la aspereza y el bruñido o pulido con diversos recursos, como piedras ágata, ampliamente utilizadas, o hueso de venado. Estos pasos consumen tiempo y se complementan para ir cerrando los poros y obtener el mayor brillo de la arcilla.

To achieve a smoother surface, in Mata Ortiz two intermediate steps developed by Juan are perfomed: the use of one or more types of 昀椀ne sandpaper to remove the roughness and burnishing withvarioustools,suchasagatestones,widelyused,ordeerbone. These steps are time-consuming and complement each other to close the pores and obtain the highest shine from the clay.

Juan Quezada Celado alcanzó un grado de re昀椀namiento que distaba mucho de las piezas que creaba antes de su relación con Spencer MacCallum. Juan Quezada achieved an incredible degree of re昀椀nement, a true contrast with the pieces he was creating before his relationship with Spencer MacCallum.

La pintura: colores y pinceles

Painting: Colors and Brushes

Desde niño, Juan había encontrado algunos pigmentos y colores para sus tizas. Una vez encaminado en la alfarería siguió experimentando, pues los colores cambiaban y los más dominantes –como el rojo y el negro– representaron retos. Para el rojo, confesó haber probado hasta con sangre animal. Finalmente encontraría el óxido de hierro, conocido también como almagre, muy abundante en la naturaleza. La base del negro sería el óxido de manganeso. Juan no estaba a gusto, pues al quemarlo se convertía en un tono café. Incluso, consideró lograda su primera olla en 1971, cuando con Nicolás, su hermano, combinó el óxido de manganeso con una piedra negra que habían encontrado y así obtuvieron el negro profundo.

La siguiente fase con la que lidió mucho fue hallar el material para los pinceles. Aunque probó con plumas de distintas aves, pelo de jabalí, 昀椀bras de coco y de agave, nada lograba el acabado que él esperaba. Hasta que un día, algo lo sorprendió. Noé, su hijo, lo recuerda perfectamente: «Él acostumbraba a cortarnos el pelo, desde chavalitos; éramos ocho de familia. Una de las veces se le ocurrió ¡hacer un pincel! “¡Esto es lo que necesitaba!”, exclamó. Un pincel de un cabello de niño, ¡y de nosotros! Se puso a experimentar y más o menos funcionó».

¿Por qué Juan habrá batallado tanto? «Cuando ya había logrado formar la pieza como yo la quería, iba ensayando pintar la primeralínea.Nomegustabaparanada.Veíaeltrazodelosantepasados,peroalprincipioyonoteníaelpulso…Laslíneasylosdiseños de ellos eran muy 昀椀rmes, eso fue lo que más me fascinaba. Hasta quepudecontrolarelpincel,dominandoelpulso».

Una vez pintada la vasija, vuelve a pulirse la super昀椀cie de la pintura. Para lograr que quede lisa, se utilizan piedras o materiales duros, se aplican grasas sólidas o aceites como deslizantes y se pule directo sobre la pintura. Este paso puede saltarse cuando se busca un acabado mate.

As a child, Juan discovered pigments and colors for his chalks, which later in昀氀uenced his experimentation in pottery. Applying colors posed challenges, especially with dominant ones like red and black. He even tried using animal blood for red before discovering iron oxide (ochre), which is plentiful in nature. The base for black would be manganese oxide, Juan was not satis昀椀ed, because when 昀椀red, it turned into a brownish tone. In 1971, when he and Nicolás, his brother, combined the manganese oxide with a black stone they had found, and obtained a deep black, he considered he had achieved his 昀椀rst real pot.

Juan also struggled 昀椀nding suitable materials for brushes. Despite trying feathers, wild boar hair, coconut and agave 昀椀bers, none met his expectations. Until one day, something surprised him. Noé, his son, remembers it perfectly:“Since we were kids, he used to cut our hair; there were eight of us in the family. One of the times it occurred to him to make a paintbrush! ‘This is what I needed!’ he exclaimed. A brush from a child’s hair, our hair! He set about experimenting, and it kind of worked.”

Why did Juan struggle so much? “When I managed to shape the piece the way I wanted it, I was rehearsing to paint the 昀椀rst line. I did not like it at all. I saw the line of the ancestors, but at the beginning, I didn’t have a steady hand. Their lines and designs were very 昀椀rm; that was what fascinated me the most.

Until I was able to control the brush, mastering the pulse.”

Once the vessel has been painted, the surface of the paint is burnished again, to achieve smoothness using stones and solid grease or oils, a step sometimes skipped for a matte 昀椀nish.

“DON

JUAN ME DECÍA: ‘NO HAGA

CANTIDAD, HAGA

CALIDAD’. YO A

VECES

ME PONÍA A HACER HASTA SEIS OLLAS. ME DECÍA: ‘¡NO! HAGA MENOS, PERO HÁGALAS BIEN’.”

“Don Juan would tell me, ‘Don’t do quantity, do quality’. At times I would make up to six pots, and he would say, ‘No! Make less and do each one better.’”

LAS QUEMAS

Firing

No queda muy claro cómo Juan se percató de que las ollas pasaban por otro proceso; especialmente por el último, que involucraba el fuego para endurecerlas. De lo que no cabe duda es que fue otro paso frustrante para él. Al no encontrar algún antecedente de horno para quemar la loza, tuvo que realizar quemas al aire libre, buscando formas de crear una cámara de combustión. Llegó a usar una cubeta galvanizada y una maceta de barro invertidas, incluso a rodear la pieza con tepalcates. Juan prefería quemar sus vasijas de una en una. Para el combustible probó primero con diferentes tipos de maderas, pensando que dependía de su calidad. Ninguno le satis昀椀zo. También encontró carbón en la sierra e hizo pruebas. Pasó a la «buñiga» (boñiga, excremento seco de vaca o de caballo) que le funcionó mejor, porque produce un fuego muy parejo. De nuevo, el clima incide en la idoneidad del ambiente para realizar la quema. Los riesgos se incrementan en un día ventoso, en invierno y en época de lluvias, pues la olla puede fracturarse y la pintura ahumarse y desvanecerse; también puede pasarse de calor y, en consecuencia —como decía Spencer—, imprimirle una «nube de fuego».

It is not very clear how Juan realized that the pots needed another process; the last one, which involved 昀椀re to harden them. What is certain is that it was another frustrating step for him. Unable to 昀椀nd the remains of a kiln to 昀椀re the pottery, he had to 昀椀re it in the open-air while looking for ways to create a combustion chamber. He used inverted galvanized buckets and clay pots surrounded by potsherds.

He preferred 昀椀ring one piece at a time, experimenting with various fuels –wood, charcoal, and even dried dung– 昀椀nding dung most e昀昀ective due to its consistent even 昀氀ame. The weather signi昀椀cantly impacts the suitability of the environment for 昀椀ring pottery. On windy days, during winter, and in the rainy season, the risks escalate: pottery can fracture, paint may smoke and fade, and there’s a danger of overheating, which, as Spencer described, can result in a “cloud of 昀椀re”. These conditions highlight the delicate balance and challenges Juan Quezada and other potters faced in achieving successful 昀椀rings outdoors.

Comienza la expansión Expansion Begins

Un caso por demás interesante en la década de los 70 fue el surgimiento de un grupo de ceramistas en el barrio El Porvenir, ubicado al sur de Mata Ortiz, pasando el Río Palanganas. Fue encabezado por Félix Ortiz, quien desarrolló un estilo sin geometría en el que los diseños eran plasmados en las ollas sin un orden particular (Jim Hills, 1999, p. 124). En su experimentación en la construcción de las ollas utilizó varios rollos. Fue pionero en formas zoomorfas e incentivó y enseñó a otros en su barrio. Este movimiento no le era ajeno a Juan Quezada y, a invitación de Félix, iba de visita incluso con su esposa Guillermina. Asíyahabíaunaveintenadeceramistasactivosenelpueblo,lo quecaptólaatencióndealgunoscompradoresdeCasasGrandesy Nuevo Casas Grandes. No todos estaban interesados en fomentar la expresión individual. Llevando libros y fotos, algunos visitantes solicitaban reproducciones de ollas mimbres y Casas Grandes, entre otras, que posteriormente intervenían para simular piezas prehispánicas. Durante un tiempo, ese mercado les representó grandes bene昀椀cios económicos; sin embargo, las estrictas leyes de protección del patrimonio cultural decretadas en México en 1972 propiciaronel昀椀ndeestapráctica.

In the 1970s, a signi昀椀cant development took place in the Barrio de El Porvenir, south of Mata Ortiz and across the Palanganas River, led by Félix Ortiz. Félix pioneered a style of pottery that departed from traditional geometric patterns, instead embracing designs captured on pots without a set order. He experimented with coil construction and introduced zoomorphic forms, becoming a mentor to others in his community. Juan Quezada was no stranger to this movement and, at the invitation of Félix, would even visit him with his wife Guillermina.

This artistic movement attracted attention, and by this time, there werearoundtwentyactivepottersinMataOrtiz.Somebuyersfrom Casas Grandes and Nuevo Casas Grandes took notice, though not allwereinterestedinpromotingindividualartisticexpression.Some visitorsbroughtbooksandphotographs,requestingreproductions of Mimbres and Casas Grandes pottery, which the traders then altered to simulate pre-Hispanic pieces. While this market initially brought economic bene昀椀ts, Mexico’s introduction of stringent laws in1972toprotectculturalheritagee昀昀ectivelyendedthispractice.

Santos Heder Ortiz López, del barrio El Porvenir, es uno de los artistas que incorpora bajorrelieves en sus ollas. Santos Heder Ortiz López from Barrio El Porvenir, is an artist who incorporates basreliefs into his work.

El contexto regional

The Regional Context

Desde 2004, los 35 kilómetros de camino que unen el pueblo de Mata Ortiz con la cabecera municipal –Casas Grandes– está pavimentado, pero termina abruptamente. El acceso a la calle principal de terracería continúa con una ligera pendiente. Bajando y girando hacia la derecha es inevitable ver una centenaria estación de ferrocarril, antes color verde botella y recientemente repintada en el color nude de moda, con algunos diseños paquimeños plasmados en la fachada. Un tramo de vías semienterradas es señal de desuso. El letrero original “Estación Mata Ortiz” aún cuelga bajo el alero que indica a su izquierda: Kilómetros a Cd. Juárez 270.6, y a la derecha: Kilómetros a La Junta 301.4.

Since2004,the35kilometersofroadconnectingthetownofMata Ortiz with the county seat of Casas Grandes has been paved, yet it ends abruptly. The main dirt road continues with a slight slope. Descending and turning to the right, one cannot miss the century-old railroad station, once bottle green and now repainted in a fashionable nude color, with some Paquimé designs adorning the façade. A stretch of half-buried tracks signals to its abandonment. The original sign “Estación Mata Ortiz” still hangs under the eaves, indicating distances 270.6 kilometers to Cd. Juárez, on the left and 301.4kilometerstoLaJuntaontheright.

El desarrollo ferroviario de la región noroeste de Chihuahua sucedió a partir de diversos proyectos que fueron entrelazándose en distintas épocas y que revolucionaron la economía.

En la vida del pueblo, el ferrocarril se fue apagando por más que en 1928 Roy Hoard había establecido una base en Mata Ortiz para reparar y dar mantenimiento a máquinas de vapor y vías.

Nombrada La Redonda, por su forma, cerraría en 1956 cuando las máquinas de diésel reemplazaron a las de vapor.

Por otra parte, la propiedad de la tierra y la llegada de grupos religiosos buscando libertad de culto también impactaron de modo importante en la región y en el pueblo. Los miembros de la Iglesia de los Santos de los Últimos Días (antes mormones) lograron adquirir tierras y permiso para establecerse en Chihuahua desde 1885. Fundaron seis colonias, entre otras, Dublán, cerca de Nuevo Casas Grandes, y Juárez, en el camino hacia Mata Ortiz. Se especializaron en huertos frutícolas, empacadoras y comercializadoras. De igual manera se instalaron los menonitas,aquienesÁlvaroObregónveríaconbuenosojospor su capacidad de trabajo en el campo, otorgándoles un privilegio (privilegium, un documento de garantías) y ciertas libertades. Estos dos grupos vienen a cuento dado que los habitantes de Mata Ortiz siempre han contado con la posibilidad de trabajar como jornaleros en sus tierras y huertos, en particular al ir cerrándose las actividades ferroviarias. La opción de pasar «al otro lado» como jornalero durante el siglo XX se dio legalmente con el programa Bracero, del que don José Quezada y el propio Juan fueron bene昀椀ciarios. Después,cuandonoseotorgabanlospermisos,Juan y sus amigos ingresaban de manera ilegal, siempre con la intención deenviardineroacasayregresar.

Academia Juárez fundada por la comunidad mormona de Chihuahua, Juárez. Academy Juárez, founded by the Mormon community of Chihuahua.

The railroad development of the northwestern region of Chihuahua resulted from various projects that intertwined over time, revolutionizing the local economy. Regretfully, the magnitude of the railroad gradually faded away despite Roy Hoard establishing a base in Mata Ortiz in 1928 to repair and maintain steam engines and tracks. Named La Redonda, due to its shape, it closed in 1956 whendieselenginesreplacedsteamengines.

Land ownership and the arrival of religious groups seeking freedom of worship also signi昀椀cantly impacted the region and its people. Members of the Church of the Latter-Day Saints (formerly Mormons) began acquiring land and permission to settle in Chihuahua as early as 1885. They founded six colonies, including, Dublán, near Nuevo Casas Grandes, and Juárez, on the road to Mata Ortiz, specializing in fruit orchards, packing, and marketing. The Mennonites, favored by Álvaro Obregón for their agricultural skills, were granted a Privilege (Privilegium, a document of guarantees) and rights to settle in the area.

These two groups are relevant as the inhabitants of Mata Ortiz have long had the option of working as day laborers on their lands and orchards, particularly as the railroads shut down.

The legal option of going “to the other side” as day laborer during the 20th century was facilitated with the Bracero program, of which Don José Quezada and Juan himself were bene昀椀ciaries. Later, when permits were no longer granted, Juan and his friends entered illegally, always with the intention of sending money home and eventually returning.

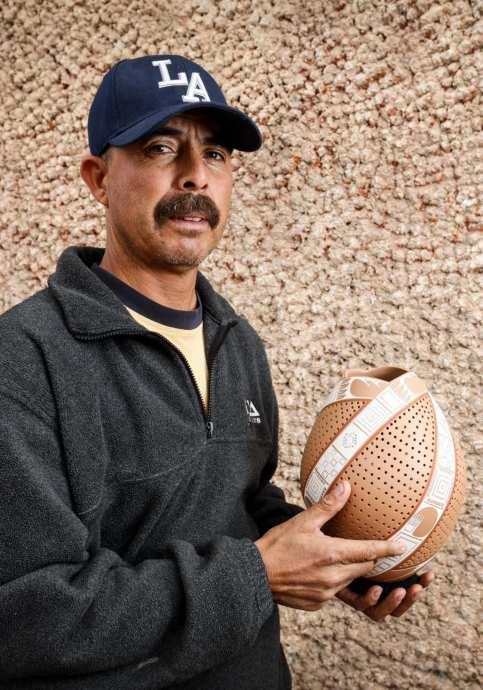

José Quezada, sobrino de Juan, ha forjado su propia propuesta dentro del llamado estilo Quezada. José Quezada, Juan’s nephew, has created his own approach within the Quezada Style.

Spencer y Juan, junto al legendario Datsun en el cual recorrieron muchos kilómetros. Spencer and Juan, next to the legendary Datsun, where they traveled many miles.

Foto: John Malmin, 1977.

DOS CAMINOS, UN DESTINO

Two Roads, One Destiny

Fotos provistas por The Museum of Us.