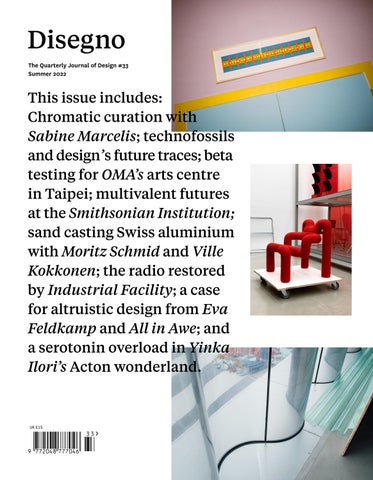

The Quarterly Journal of Design #33 Summer 2022

This issue includes: Chromatic curation with Sabine Marcelis; technofossils and design’s future traces; beta testing for OMA’s arts centre in Taipei; multivalent futures at the Smithsonian Institution; sand casting Swiss aluminium with Moritz Schmid and Ville Kokkonen; the radio restored by Industrial Facility; a case for altruistic design from Eva Feldkamp and All in Awe; and a serotonin overload in Yinka Ilori’s Acton wonderland.

UK £15