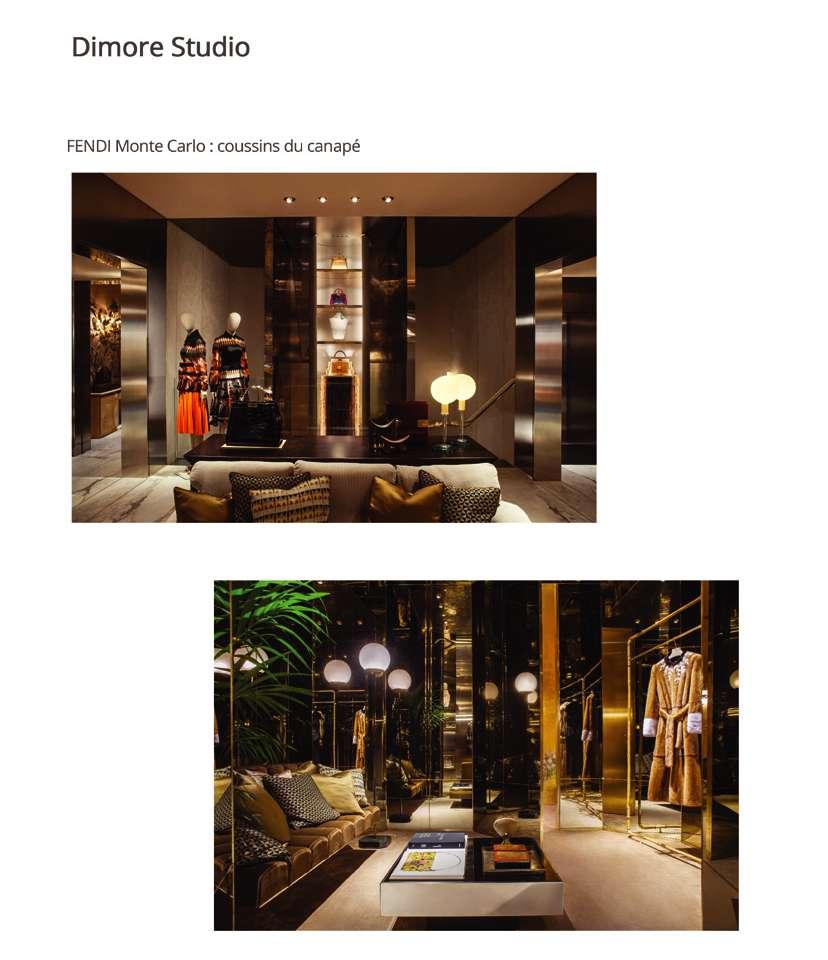

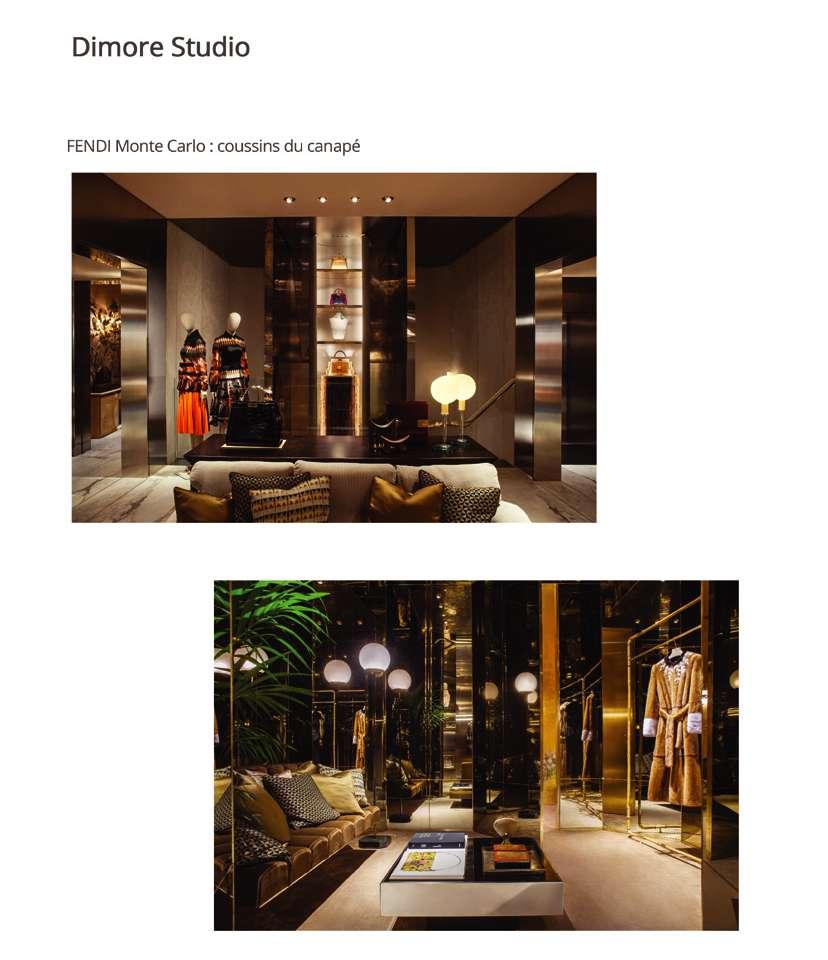

Boutique DIOR Saint-Tropez, Réalisation paravant, fauteuils et revetement mural en collaboration avec Dimore studio

Tissus réalisés pour les fauteuils Publication dans Elle décoration n°287, Avril 2021

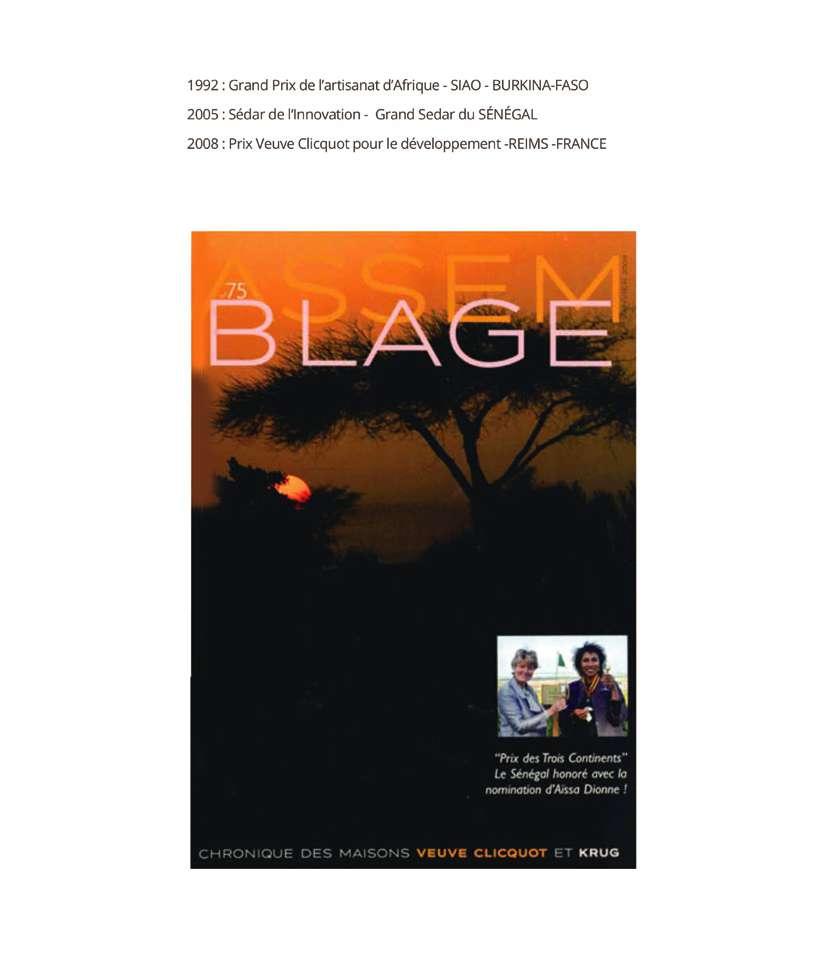

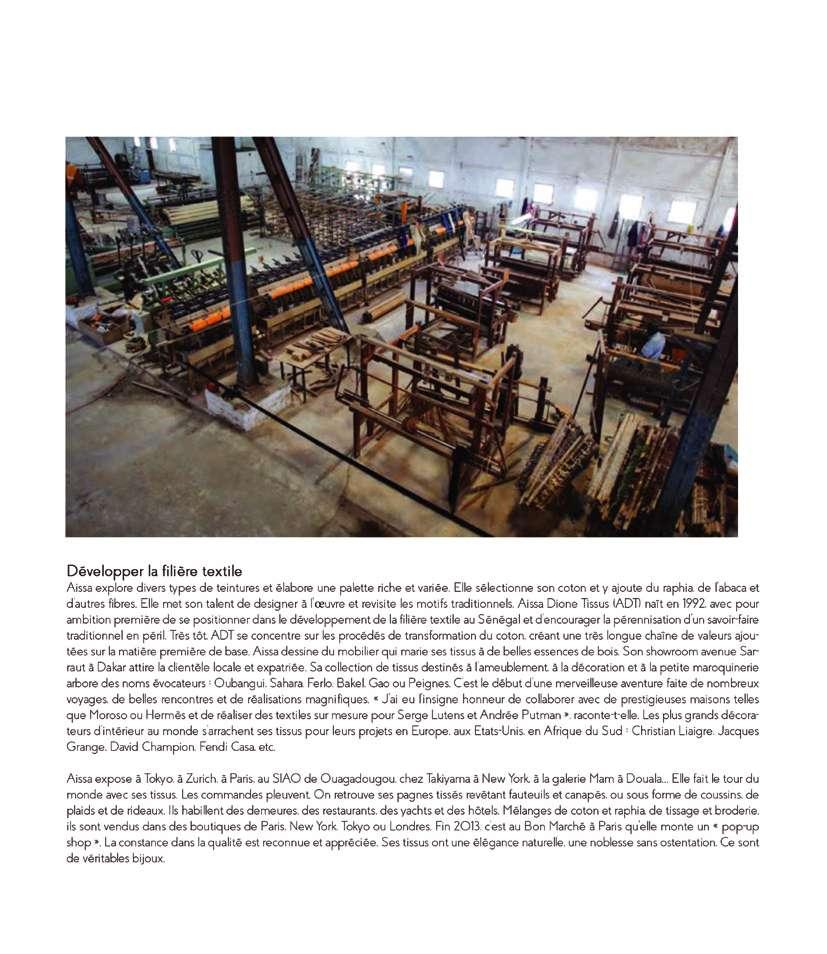

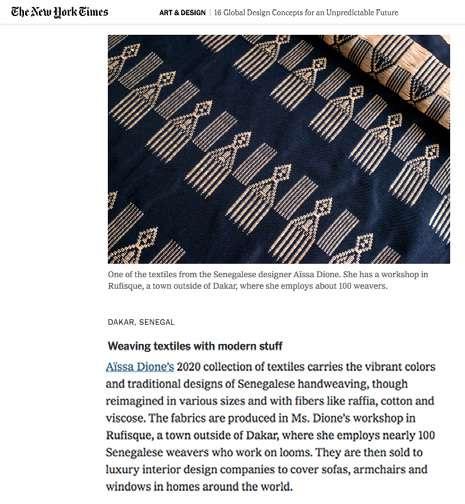

Senegal’s artisan-textile industry might easily have sunk without trace but for the persistence of one Aïssa Dione. Fearing for its future, the artist and fabric designer set

about saving it from the threat posed by cheap imports. Thanks to her, there’s now a buoyant market in chic manjak, the country’s traditional cloth, and a corner of a city near Dakar is alive once more with the clatter of looms. Text: Jareh Das.

Photography: Maciek Po�oga

Ghana has its woven cloth known as kente. In Nigeria, it is adire, an indigo resist-dye cloth. Dida is Ivory Coast’s raffia material. Bogolan, popular in Mali, is dyed with fermented mud. Hand-woven designs of traditional African textiles are as diverse as the ethnicities spread across the continent. Every location has its own tradition.

For Senegal, it is manjak, a woven cloth that originates in Guinea-Bissau but also springs up throughout Gambia and Cape Verde. Textiles on this huge continent are not only central to personal adornment; they are also revealing and vital aspects of communication, signifying economic worth and class status, as well as being key to ceremonies, from births and deaths to

weddings. Passed down from one generation to the next, the customs involved in creating them are crucial to the continuity and future of African textiles.

In the capital city of Dakar, French/ Senegalese artist and textile designer Aïssa Dione has spent three decades reviving and reinventing the country’s traditional cloth. She founded her company, Aïssa Dione Tissus, in ���� with the long-term goal of keeping fabric weaving there alive and creating new markets both locally and internationally. Central to her approach is an emphasis on a ‘slow’ industry and making a long-established product relevant for modern tastes. Its sustainability can also serve as a template for other African nations, where indigenous crafts struggle to

survive in the face of cheap imported fabrics and a lack of government investment. Working out of a factory located in Rufisque, near Dakar, Dione oversees more than ��� employees who use traditional looms, as well as restored mechanised ones bought from abandoned factories, to create luxurious pieces from African cotton and centuries-old manjak.

‘I arrived in Senegal in my twenties having trained as a painter in France,’ she explains over the telephone. ‘I began looking at batik [wax-resist dyeing] initially to make clothing. That then led to looking at traditional Senegalese textiles, which are dominated by hand-weaving, specifically manjak, which is male-led. My interest is fabrics for interiors and I thought, well,

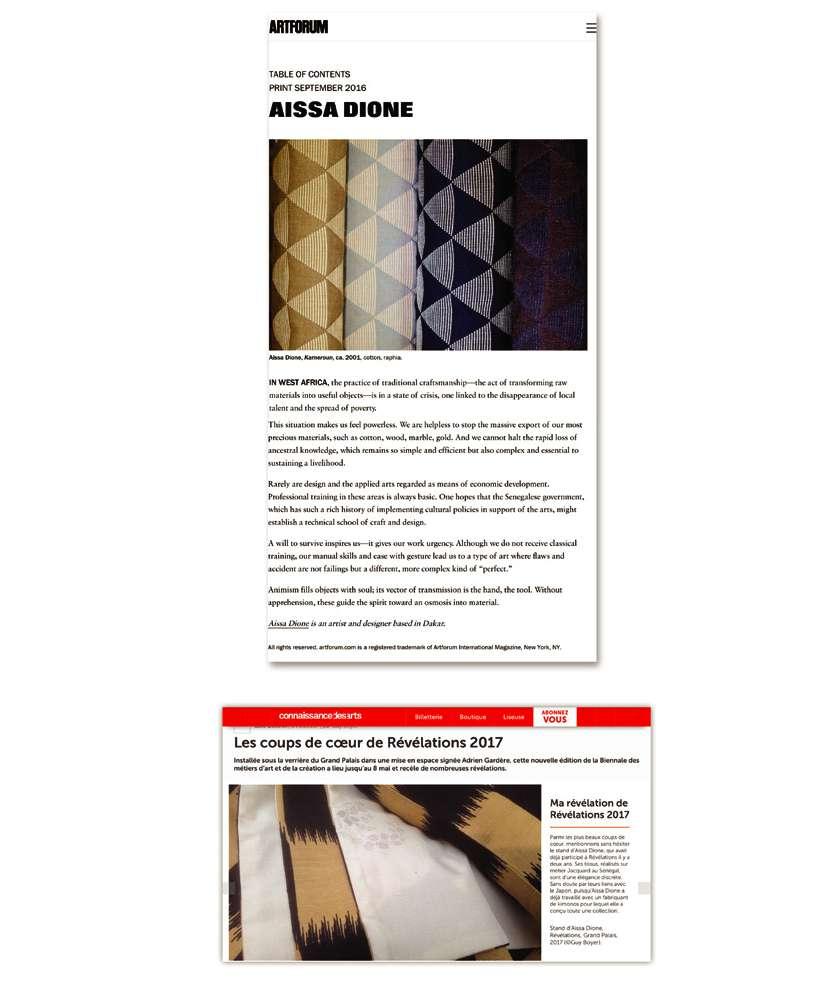

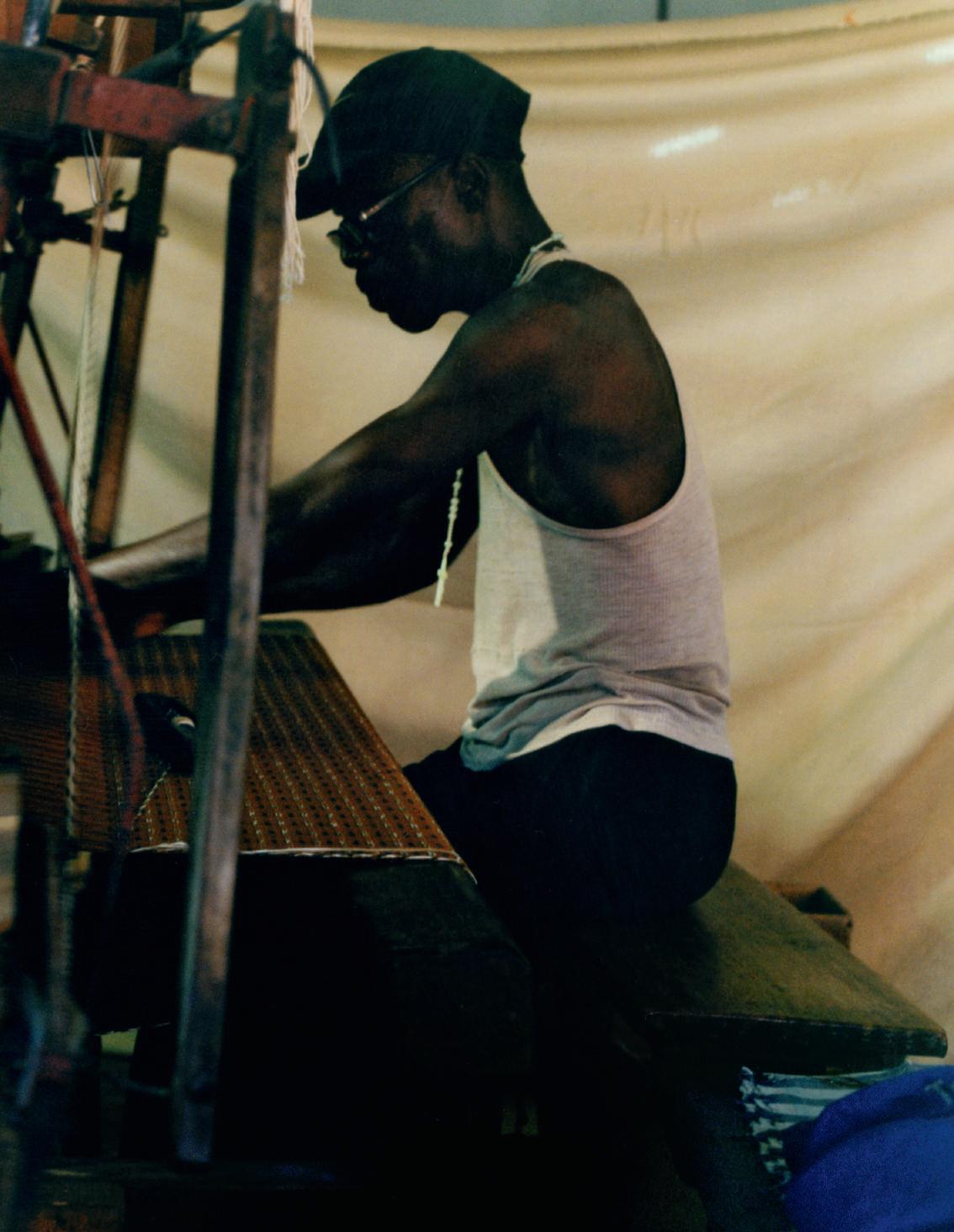

Previous pages: Edouard Sanga, an employee at Aïssa Dione’s factory in the port city of Rufisque, operates one of several looms acquired from redundant mills over the years. Some of these have been adapted to allow wider runs of fabric than normal to be made. Top: cotton is spun into yarn ready for weaving. Opposite: modern geometric designs adorn these cloths, which are a blend of cotton, raffia and silk

rather than fabricating with imported textiles, let’s create fabrics ��� per cent made here in Senegal as we have access to cotton and traditional weavers.’

Unsurprisingly perhaps, she’s had challenges to overcome. One client requested upholstered furniture and curtains, which initially posed a problem. ‘Manjak weaving is spun on looms ranging between ��cm and ��cm,’ says Dione, ‘which for interior fabrics just isn’t wide enough. So we had to innovate. Working with the weavers, we increased the width of the textile to ��–���cm to make it commercially viable.’

Minimal, distinct geometric patterns are a feature of Dione’s fabrics, while motifs spun from locally sourced raffia, silk and cotton draw on Kuban, Congolese,

Manjak and Gambian culture. ‘Indigenous crafts made on the continent need to be elevated to luxury products,’ she says. With that comes a higher aesthetic and economic value – and the result is a company basking in a certain renown. Clients include Hermès, Fendi, Liaigre, Peter Marino and Alara Lagos. She’s also worked with Yinka Shonibare and India Mahdavi on Sketch in London, while Aïssa Dione for Okujun is a long-term collaboration producing interior textiles, including plains, ikats and prints, that bring together both African and Japanese techniques.

‘It makes no sense whatsoever that cotton sheets are imported when cotton grows all across this continent,’ Dione says. ‘From weaving to pottery to

basket-weaving, there’s so much scope to scale this for export while tackling production locally to solve issues around importation and job creation.’

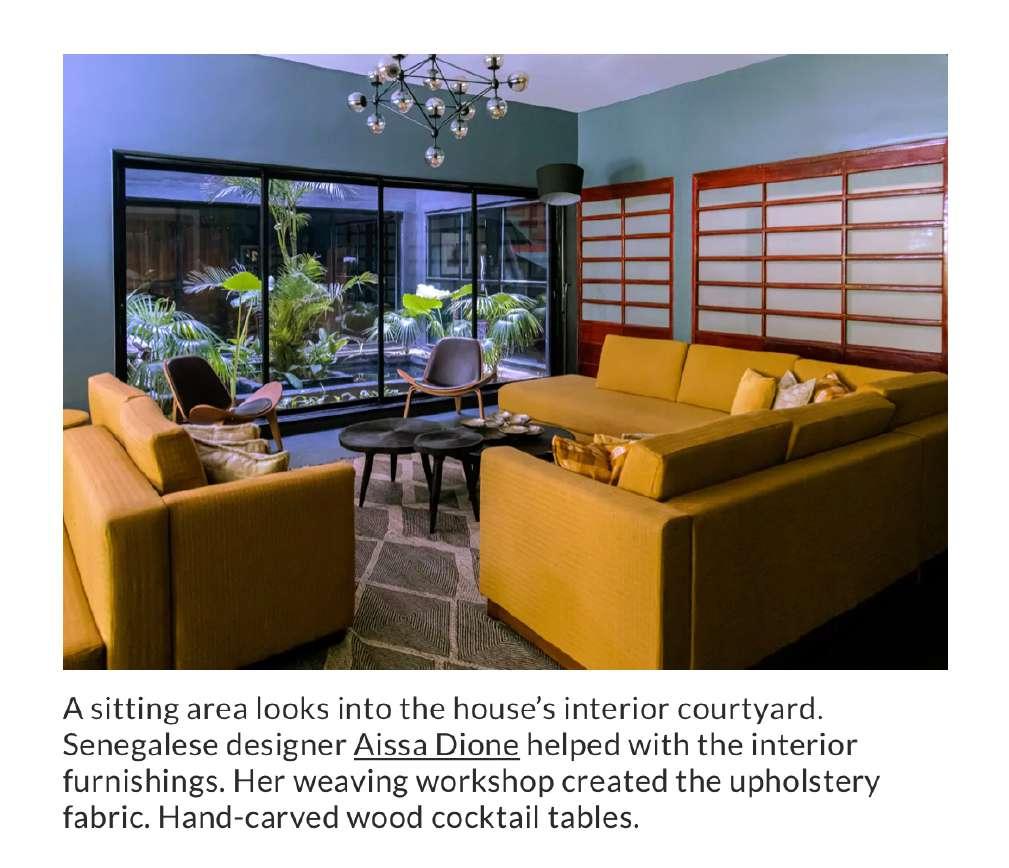

To this end, Dione has expanded her operation to produce a concise range of furniture, from upholstered sofas and chairs to tables and lamps, all crafted from indigenous woods. By supporting carpentry, upholstery, metalwork and other skills, the workshops enable an end-toend design and production process that is proudly Made in Africa.

While passionate about protecting time-honoured traditions, Dione is also alert to the very pressing need to nurture a younger generation of artisanal workers, chiefly through fair pay

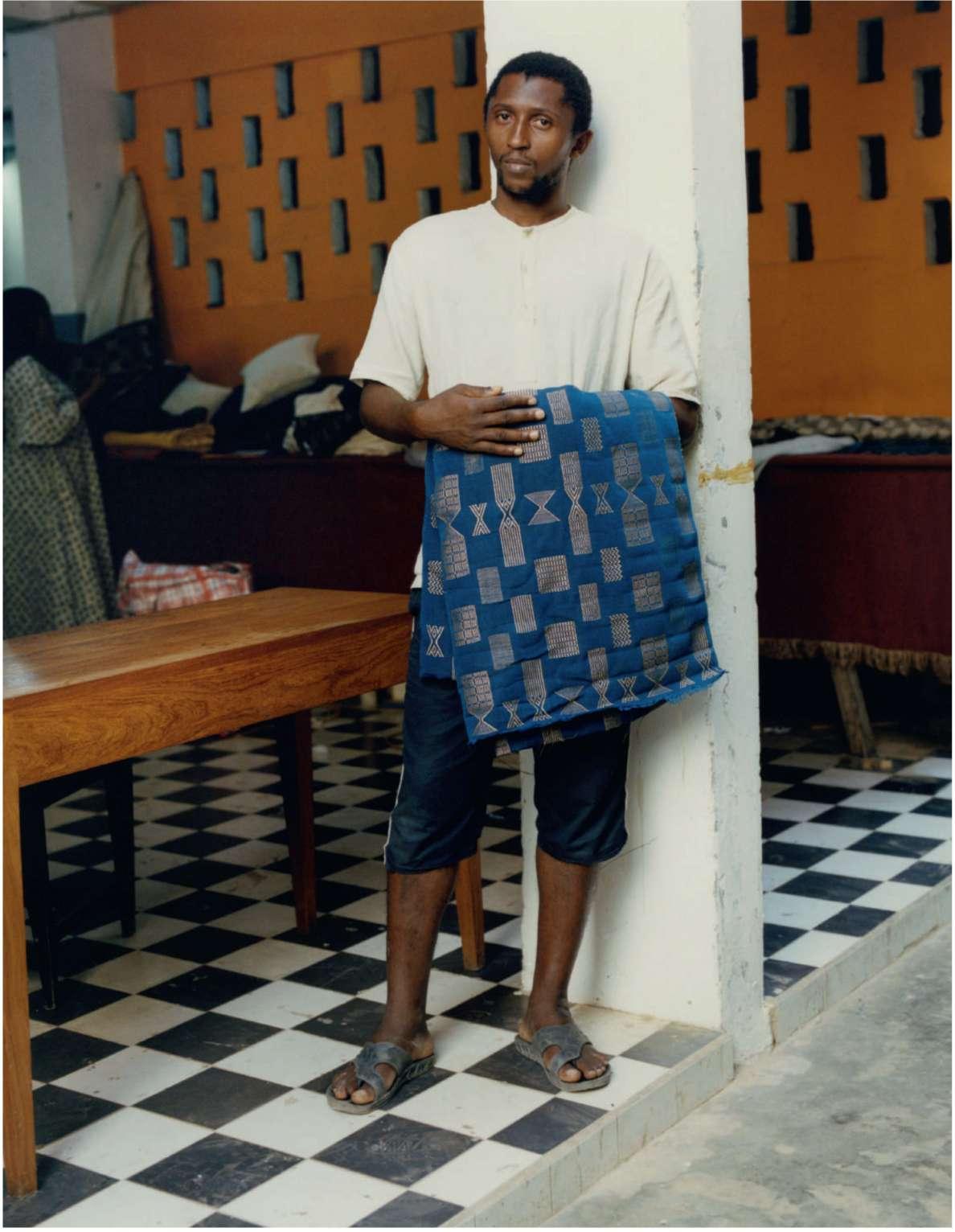

Opposite: Tidiane Barry, a weaver at the Aïssa Dione Tissus factory, holds a thoroughly modern take on ‘manjak’, Senegal’s traditional cloth. This page, top: all of the firm’s fabrics take their names from African places or legend. Here ‘Ibadan’ (after the Nigerian city) covers a pair of ‘Yuki’ slipper chairs from Dione’s ‘Weaving Art Objects’ furniture line. The hand-carved table is from the same collection

and employee benefits. Visit her gallery, Galerie Atiss Dakar, and you will also see that Dione has also been busy exploring the coming together of art and textiles. Exhibitions there have highlighted how contemporary African artists are using traditions to illuminate connections and continuities. A recent show, Art and Textiles Stories, is a good example. The roster included Aboubakar Fofana from Mali, who reinvigorates and redefines West African indigo dyeing techniques, and Nigerian fashion designer Bubu Ogisi,

whose pieces imaginatively reuse natural and non-natural materials, including crochet made from recycled plastic and fibre from agricultural waste. Fatim Soumar� , from Senegal, exploits the Falé tradition of transforming cotton into thread by hand, while Cedric Mizero collaborates with communities across his country, Rwanda, engaging them in conversations about indigenous practice. He sees this as a means of effecting collective healing. Showcasing textiles and fibre-making across borders and timelines is shining a

fresh light on histories and their meaning for the present.

By forging closer bonds between art and industry, Dione is proving that textile manufacturing across Africa, in all its dazzling forms, can be both innovative and sustainable. Materials, techniques and aesthetics combine to produce items of artistic and commercial value. It’s vital this goes on: for jobs, market demand and the preservation and spread of culture ª Aïssa Dione. Visit aissadionetissus.com. Galerie Atiss Dakar. Visit galerieatissdakar.com

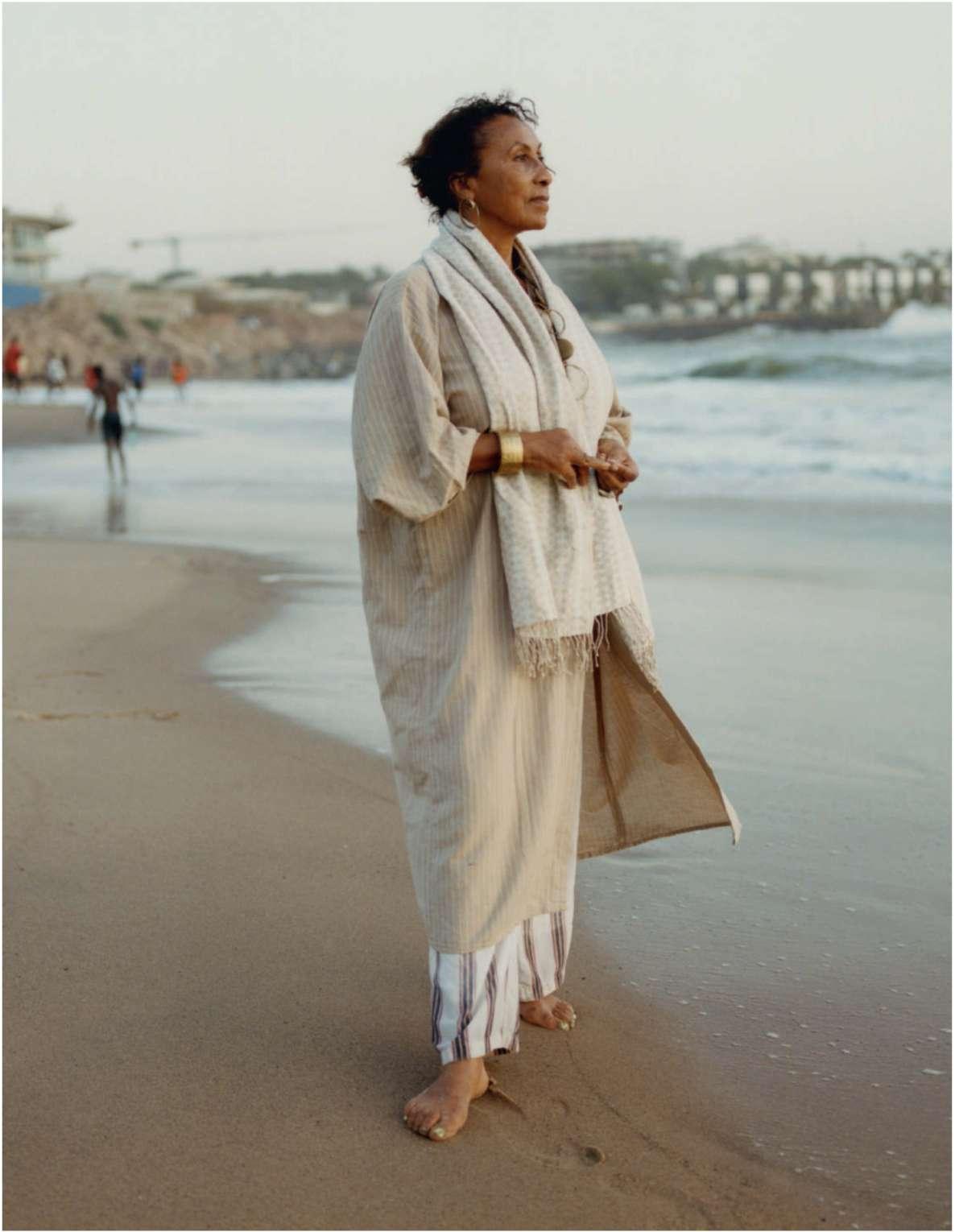

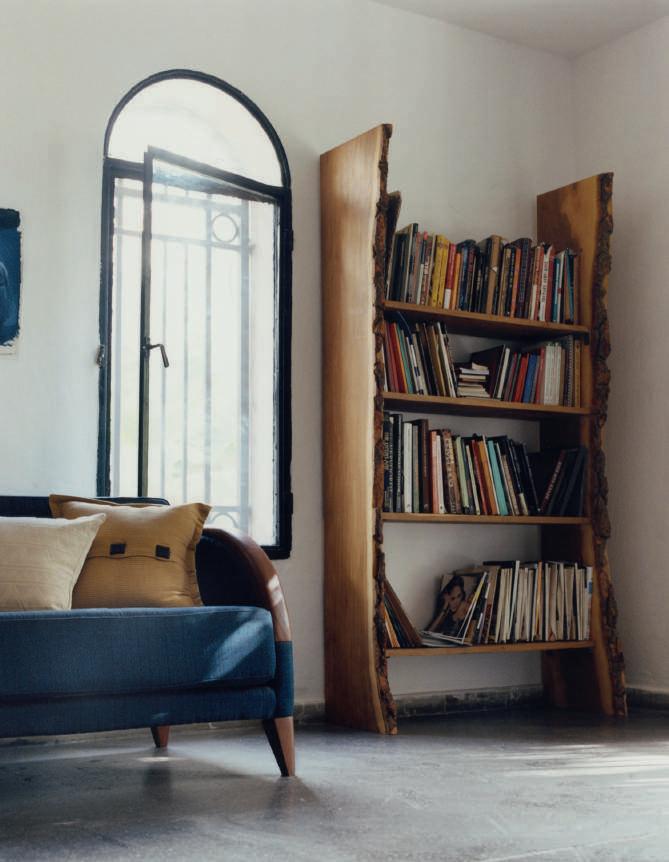

Top: like all of the furniture in Dione’s range, this bookcase is made from locally sourced wood. Opposite: dressed head to toe in textiles produced by her brand, the designer herself looks out on to Mermoz beach, a popular resort close to her home in the Senegalese capital