Village

The Countryside as a City

Dimitris Venizelos and PG Smit

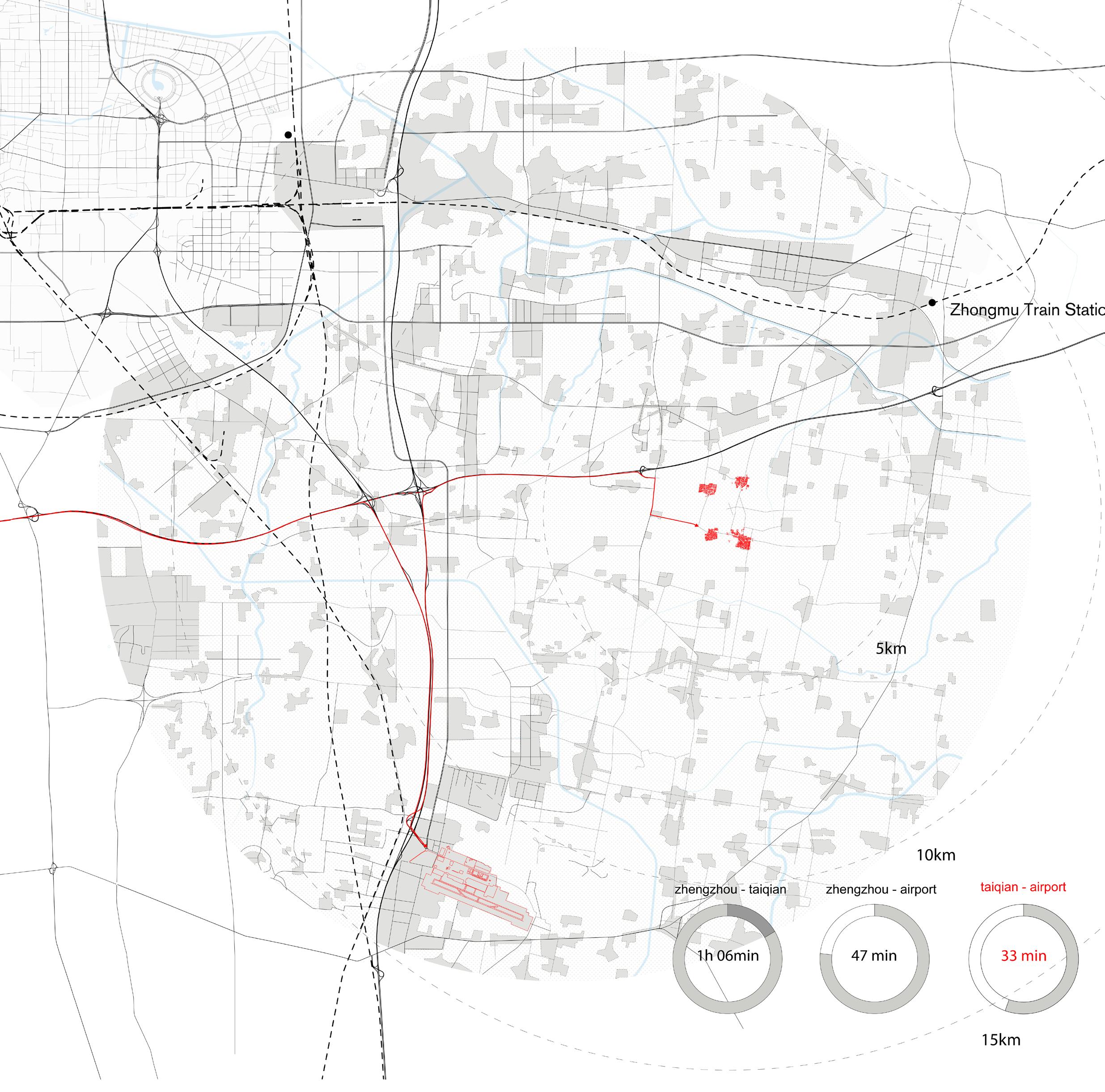

Location : Taiqian, Dongzhao, Yantai and HeinizhangHenan Province, China.

[AECOM / HARVARD GSD] Common Framework:

Rethinking the Developmental City in China, Part 3Chris Lee, Simon Whittle 2015

The Chinese countryside is rapidly changing due to rampant industrialization and urban migration. The shift from agriculture to migrant working has erod ed living conditions and strained family structure in ru ral villages.

The government seeks to alleviate the inequali ty associated with rural conditions, stimulate the econo my and optimise land use through the amalgamation of villages into New Agricultural Towns. The villages of Taiqian, Dongzhao, Yantai and Heinizhang, at the outskirts of Zhengzhou will undergo this process. While we agree that significant investment restructuring of the villages is required in order to im prove living standards in the villages and stem migration towards cities, we question the wholesale demolition and relocation of the villages.

Consolidation will erase a built environment and way of life that has persistedfor generations. The character of village life will change forever and will lead to a gradual homogenisation of cultural difference. We believe new towns not only offer little in terms of real economic opportunity but actually inhibit econom ic growth which we believe is crucial to the long term sustainability of the village. In addition, we believe the existing villages offer a key for their own growth by util ising their spatial, cultural and economic uniqueness. What if we could maintain the dispersed nature of the villages?

Could we improve living conditions through ad aptation and insertion rather than wholesale erasure and replacement?

Could we rethink the village as a position of privilege thereby creating an attraction that could estab lish a counter-flow of people to the countryside?

Could we optimise land through hybrid pro gramming, diversified economic activity and value ed commodities, thereby creating greater revenue and employment opportunities within the village?

Agricultural Innovation Area

THOUGHTS ON CURRENT PRACTICES

Taiqian, Dongzhao, Yantai and Heinizhang - currently undergoing the process of consolidation – found themselves in a temporary simultaneity of conflicting conditions; On the one hand the looming threat of top-down obliterating policies, immense investment in transportation infrastructure already at place dominating an agrarian landscape and new urban architecture for new villages. On the other hand a traditional lifestyle foreign to the marching modernizing vision, a common life shared in relation to agricultural practices and villages slowly but surely approaching the end of their existence.

In China, the relationship between location of residence and way of life governs the social and spatial qualities that discern the rural from the urban. ‘Rural citizenship entails self-responsibility in food supply, housing, employment, and income, and lacks most of the welfare benefits enjoyed by urban residents.’[1] The rural status of village dwellers allows them to own land as part of a collective, and to earn a livelihood through agriculture. The advent of rural urbanization dissolves the definition of what it means to be a villager, and this comes with forms of disposession and alienation: ‘loss of land, livelihood, social networks and collective identity.’[2]

Within the government’s plan for consolidation, there exists a concern for the preservation of agricultural land. However, there is less of a concern for the preservation of cultural traditions and the way of rural life. In the existing villages, the engagement with agricultural practice is not only means of livelihood but also an activity that builds community. The drying and processing of corn becomes an enterprise that engages the entire community and activates the spaces of the entire village.

The cultural function of what is perceived as a non-competitive economic enterprise, is not considered as a priority in the design of these new towns. Rather, what is pursued is a process of modernization that replicates western paradigms and promotes a consumption culture, until now alien to the countryside. The Chinese government’s ideals are ‘[...] looking to maximize efficiency and livability, to modernize archaic portions of the urban fabric, once so uniquely suited to earlier patterns of technology and social organization in order to adapt them to the convergent needs of the 21st century.’ [3]

But can a town be designed without concern for identity and culture and deprived of its ability to change in a sustainable way?

[1] Hsing, You-tie, The Great Urban Transformation: Politics of Land and Property in China. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2013. 2010 p. 195.

[2] ibid p. 185.

[3] Abu-Lughold, Janet, ‘The Planners’ Dilemma: What to Do with a Historic Heritage,’ Design Book Review no. 29/30. 1993. pp. 26-31.

This project questions the wholesale demolition and relocation of the villages proposing instead to maintain their dispersed nature by augmenting the existing communities through a process of selective erasure and strategic insertion.

Rural villages weave together agricultural tradition and social life in co-mmon spaces. This condition manifests spatially through the employment of every available surface, from bedrooms and courtyards to pavements and streets, as part of agricultural production and processing. These activities penetrate all strata of privacy, from residential interior to public street. The streets are spaces of social activity and constitute the primary form of public space in the village

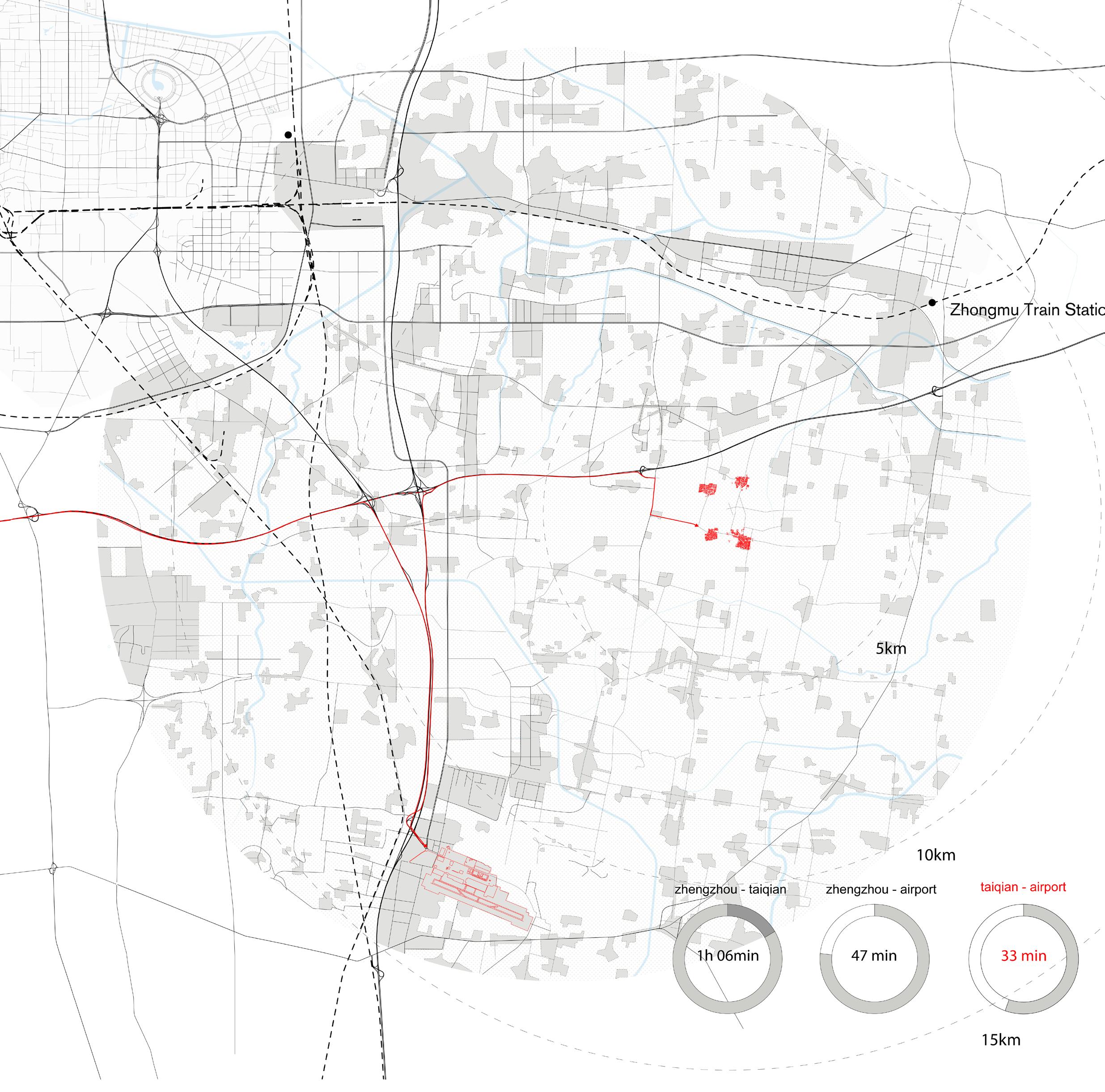

Large parts of the village are abandoned and underutilized and need to be cleared or renovated, repurposed and restructured. The existing fabric is comprised of an orthogonal grid that delineates strips of housing. The blocks are elongated to such an extend that they read as bands of fabric. Based on this ribbon structure, the project proposes a selective erasure of buildings along a single street to free land for development. The strips of liberated land are restructured through the insertion of new program; on the edges of the bands are buildings with a reduced footprint, and to the center are strips of agricultural land.

The plan consists of two primary elements: (1) the bands of erased fabric that become horizontal strips of new

development and (2) staggered perforations of the preserved fabric in between the bands that create a secondary circulation system.

The bands layer three components: new rental housing; productive and recreational landscapes (fields, community gardens, playgrounds, gathering spaces, and large surfaces for drying and processing); and new small-scale artisanal production and exhibition spaces. The bands not only create much-needed production and social spaces for the villages but also offer a platform for visitors to engage with the production processes first hand.

New infrastructure, housing, amenities, and production spaces become the foundation for diversified economic activity centered around ecotourism: marketing the experience of the villages, advancing agricultural production, and promoting value-added products. An overlay of light manufacturing works in tandem with organic show gardens for passive recreation. The gardens, which can be rented by visitors, are used to grow fresh organic food, herbs, flowers, and seeds.

The bands suggest an alternative reading of the village. Horizontally the bands draw landscape in and frame the villages through the lens of landscape. Vertically, the village is perceived as an alternating sequence of old and new, with the new buildings serving as filters for this transition. In order to increase permeability of the fabric, as well as access to the bands, the existing village blocks are perforated by passages that use vacant or underutilized lots. These passages create a secondary circulation system along which are located points of interest such as recreational spaces.

Within the bands, the new housing units are arranged in a sawtooth structure. Pockets of open space on alternate sides are shaped by the building’s geometry, forming an elongated version of the traditional courtyard house. These are either private courtyards facing the agricultural land or small public open spaces facing the street, serving as extensions to it. Rich and diversified spaces and experiences flow into each other throughout.

This proposal aspires to provide an alternative vision for the countryside that preserves the village as cultural and spiritual heart and projects into China’s future a past not forgotten.

Stripping of bands and infill process: relocation of the erased fabric in the voids of the preserved fabric.Preserved sections are densified

Staggered perforations: introduction of new program, amenities and increase of porosity in the N-S direction

Reconstructing Varosha

Dimitris Venizelos, 2013.

National Technical University of Athens

Supervised by Dr Io Carydi and Dr Dimitris Papalexopoulos

In the summer of 1974, Turkey invaded Cyprus. The Greek Cypriot residents of Varosha, the vibrant modern quarter of Famagusta, fled south as the Turkish military advanced. They were told they would be able to return to their homes within days, once the conflict subsided. Four decades later, they still long for that return. Since 1974, Varosha has remained inaccessible, a fenced-off, militarized area gradually decaying and surrendering to nature.

Over the intervening decades, this enclosed town has become a powerful symbol of occupation. Both people and the state have worked to keep the memory of Varosha alive, an effort that has often led to the creation of new ideas and “memories” of the city shaped by nostalgia and idealization. Generations of Cypriots born after the invasion paradoxically “remember” Varosha through images, testimonies, and stories from displaced residents. These references have changed over time, creating a myth of Varosha that has drifted from its physical reality.

This project proposes a method for reconstructing Varosha with two primary aims:

1. Aligning Myth with Reality: This involves inscribing the collective memory of Varosha onto its physical landscape through new additions to its urban fabric. This inscription takes the form of new streets and structures that integrate with the existing, now dilapidated grid. Since its establishment, Varosha’s expanding urban fabric has reflected the historical evolution of the town. The project leverages this quality, using the grid as a vessel of collective memory to synchronize the physical form of the quarter with its collective imagination—an imagination that has continued to evolve in exile, creating new “memories” of place. A topological rhizome of memory is overlaid on the existing geometries of the neglected urban fabric, producing an infrastructural palimpsest upon which the city can rebuild itself.

2. Phased Redevelopment to Preserve Ownership: The redesigned urban fabric promotes a phased redevelopment model, allowing displaced owners to retain their land in the face of looming threats of large-scale erasure and redevelopment. This reconstruction model combines ribbon development with small-scale land redistribution and follows a phased approach. Parcel-by-parcel organic reconstruction, led by displaced owners, challenges wholesale master planning methods that risk introducing market-driven forms of dispossession and displacement. This phased approach is tested by introducing a dispersed university campus as a regenerative anchor within Varosha’s urban system, providing an economic driver to initiate its redevelopment

URBAN FABRIC: A REGISTER OF HISTORY AND MEMORY

Since its birth in 1573, Varosha developed in a radial pattern across nearly five centuries. Its spatial history is layered like an onion: starting from the medieval core and extending toward the coast, one can walk through time, moving from the 1600s urban cluster bounded by Ermou and Tefkrou streets to the modernist high-rises of the 1960s and 70s along Kennedy and Ippokratous Avenue.

ASYNCRONY

No longer a product of spatial experience, the act of membering” has become a process of active “building” an augmented reality for Varosha: new “memories” have been constructed in exile although not even a single brick has been moved on the actual site. This “construct ed reality” can be understood as the result of nostalgia and idealization, precisely because of its inaccessibility.

Post-war generations paradoxically “remember” their own version of Varosha, reconstructed through narra tions, press, school classes and literature, admittedly flated and idealized or even skewed.

Each phase of Varosha’s expansion is formally distinct, adding unique typological layers to the evolving urban grid, with each addition separated from the previous by a main street that had marked the thenedge of the city’s fabric. Varosha’s streets thus serve as markers of the city’s historical periods, forming a spatial timeline that embeds a collective memory of the city.

In today’s deteriorated environment, these street traces endure as the most resilient connections between space and time, as many buildings and monuments have been irreversibly damaged. In this project, the street is proposed as a tool for reconstruction, serving both as a framework for rebuilding and as a bridge connecting the present landscape with an imagined city that has continued to evolve in exile.

Each consecutive expansion of Varosha’s fabric is formally manifested as a distinctive addition to its accumulative urban grid separated from previous ones by a main street that was up to that point a circumference of the suburb. Such streets serve as demarcations of historic periods in the city’s life, a spatial timeline. In the decant environment of Varosha, traces of the grid are the most resilient and reliable links between space and timesince buildings and monuments have taken a rather irreversible course to destruction.

ATTUNEMENT

Recognizing the need for extensive repairs of infrastruc ture for the purpose of reconstruction, the project utiliz es the streets compositional capacity to organize space and orient it in time; besides the obvious functional the street is used in order to project post-74 collective urban imaginaries of Varosha on its real fabric, attuning

ATTUNED (PROPOSED) FABRIC

for

Syncronization

Interviews with young Cypriots, who have no personal memory of the town, are conducted to uncover what is ‘remembered’ of Varosha. These recollections often draw from pre-1974 photographs and, just as significantly, from stories passed down as oral histories across generations. These memories are mapped as points, with their frequency of occurrence weighted to create a unique spatial footprint. A generative algorithm then interprets these weights, producing a topological “rhizome of memory”—a myth for Varosha, inscribed through newly marked traces on the ground. These traces outline areas, each anchored to a significant landmark embedded in the collective memory. The boundaries of these areas transform into new streets, forming a mental map of the imagined city. This new grid, overlaid upon and integrated with Varosha’s existing street network, creates an evolving urban palimpsest. It merges the pre-1974 urban fabric with the aspirations of a post-1974, contemporary Varosha. These streets serve a dual purpose: perceptually, they delineate spaces of collective memory within the real landscape; technically, they form a foundational infrastructural network, spanning the entire site. This network supplies electricity, gas, water, and telecommunications—essential utilities that support the process of reconstruction.

points of collective memory that operate as new centers for the reconsructed city

network of new traces

The generic rule preconditions that every new construction cell is neighboring with at least one cell of preserved fabric : this decision accomodates both the potential of contemporary development as well as the presence of Varosha’s legacy.

These generative rules give birth to a new urban typology: the once “figure” (pre-1974 fabric) now becomes an active “open ground” allowing for a broad spectrum of re-appropriation and retrofitting to new functions that can be described as open urban space: urban green, outdoor theaters, openair cinemas, storage infrastructure, urban agriculture, gardens, galleries, parking lots, open-air theaters, performance spaces, playgrounds, urban ventilation corridors. The rest is scraped off to release ground for the city’s new developments.

Reconstruction will be gradually achieved through a land-managemen pattern that prescribes a pattern of absolute preservation of the exisitng ruinous landscape and of erasure that will give ground to new spaces. An algorthm stipulates the relation of presevration and erasure: every erased and reconstructed part of the town must be neighboring with at least one area of preserved ruinous landscape. This fundamental decision accomodates both the potential of development as well as the presence of Varosha’s legacy.

The preserved (pre-1974) derelict fabric is envisioned as an active “open ground,” a landscape that allows for a broad spectrum of re-appropriations and new functions: urban green, outdoor theaters, openair theaters, storage infrastructure, urban agriculture, gardens, galleries, parking lots, playgrounds, urban ventilation corridors, sustainable urban draining systems. The rest of the ground is free to absorb new development.

PHASED REDEVELOPMENT

the urban algorithm for reconstruction is tested for the development of a university campus, proposed as an economic engine that can subsidize the reconstruction of the quarter.

Courtyards

Housing design competition entry, the Cyprus Land Development Corporation. Lead architect: Dimitris Venizelos, 2013. Design Team: Aigli Patsalidou, Aristofanis Hadjicharalambous, Panayiotis Liasi

The proposal inestigates the potential of offering spaces for communal life in the context a of a ‘social housing’ project which is pre-empted by the development process as a collection of individualistic and fragmentated insular housing units.

We approach communal space as an architectural type that is situated between the domestic interior and the public outdoors. This ‘in-between’ space draws precedence from the archetypes of the hut, the garden and the courtyard that have defined the traditional forms of habitation on the island.

We creatively appropriate these archetypes to reclaim space a use-value, and to remind that life in the Mediterranean takes place outdoors, and most importantly, that it is a life shared with the community.

House 01

Status: Completed (2023)

Location: Paphos - Cyprus

Architect: Dimitris Venizelos

Design Consultants: Lefteris Siamopoulos, Constantinos Marcou

Structural Engineer: Domostatica Engineering

Mechanical Engineer: Anna Antoniou

Electrical Engineer: Marios Nikolaou

Photography: Dimitris Venizelos

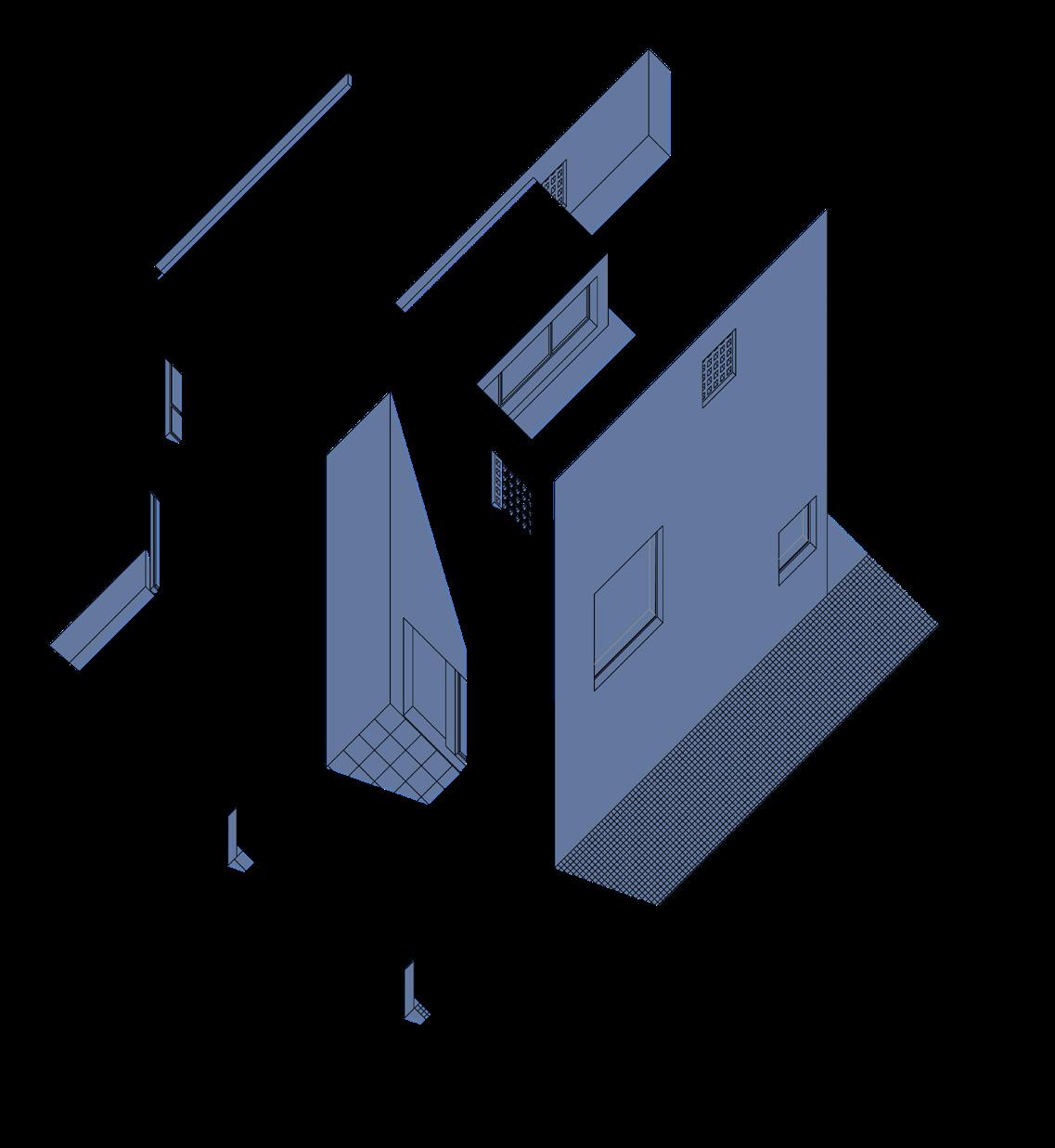

House 01 is crafted around two core objectives. The first, centered on the clients’ needs, is to create a fully finished, functional home of 165 square meters for a family of four, occupying only a quarter of the available plot and staying within a budget of €300,000. This compact design emphasizes efficient use of space without compromising on the enjoyment of space.

The second objective, focused on the architectural discipline and its role in the housing industry, is an exploration into reclaiming architectural qualities that are lost within a market-driven housing model. The challenge lies in preserving the open, convivial spirit of Mediterranean living within the constraints of minimal space. This approach prioritizes both a sense of generosity and a connection to the surrounding environment, aiming to bring the pleasures of Mediterranean lifestyle into a practical and compact architectural form.

Curation of Live Performance

Kouza

Artist: PASHIAS

Organised by High Commission of Cyprus - UK

Curated by Dimitris Venizelos

Fitzwilliam Museum / Cambridge - UK

March, 2024 / Duration: 45’

The Social, Historical and Material Body of the Artist

Why do we use metaphors of our body such as ‘legs’ and ‘ears’ to describe parts of a clay pot? Why do we indulge in language games that conflate the amphora with a human head, as the word ‘kuza’ in the Cypriot dialect denotes? PASHIAS very literally asks this question by replacing his own head with a fragment of a ceramic pot recently crafted in Cyprus and transported to the Fitzwilliam Museum. PASHIAS’ figure, part-human and part-clay, engages in a dialogue with ceramics exhibited in the museum, which were fashioned from Cyprus’ earth millennia ago. Archaeologists have put forth various theories regarding the origins of anthropomorphism in pottery: cultural symbolism, religious significance, practical needs of daily life drawing inspiration from our own bodily forms, or, alternatively, the metaphor could be seen as reflecting a universal aspect of human cognition rather than specific cultural or religious beliefs.

PASHIAS’ previous work, such as the “Temple-boy” (2017), has explored these speculations. In “Temple-boy” the artist investigates the representation of the human body in a 5th c BC figurine through the notion of metabolism and by linking the ritualistic character of the anthropomorphic artifact with the physiological processes of the human body. However, the current piece suggests a different direction in the artist’s exploration of the topic. In contrast to the 5th c BC figurine which represents in a realistic way the human body, the ‘kuza’ is only its abstraction.

It is suggested here that there is something profoundly relatable in the shape and mate-

riality of the amphora that transcends mere resemblance to the human body.

The figure of the artist is a direct reference to this deep material connection of our body to a materialist history, to historic time, to what we coin as ‘heritage.’ What the human/ kuza figure alongside the displayed archaeological findings suggests is that our relationship with history and time is not abstract but material, it is recollected as a ‘thing’.

This is as a reminder - and how timely this is - that our lives are intertwined with those of others, our contemporaries, predecessors and successors through universal and enduring human needs that remain unchanged over the course of history. All humans suffer the same in the face of thirst, in the face of hunger. The amphorae were made to carry and distribute goods to satisfy these universal needs. In holding the amphora over his head with a gesture of a loving cuddle that surrounds his head/kuza, the artist holds simultaneously the universal head of humanity. With references to Saint Simon’s revolutionary ideas the artist assumes the responsibility to influence and shape society. This theme was addressed in earlier works of PASHIAS such as the “Metaphora” (2019), where the artist’s body assumes the structural role of an architectural element to support a (social) structure, or even in “A.B.S. (Training for performance #7)” (2016) where the artist, as a new Titan lifts the weight of the world on his shoulders. From a different perspective, the figure of the artist/kuza represents humanity as a continuous material presence in our world, extending beyond our individual lifespans.

The artifact provides evidence of this continuity in a tangible manner, as one can still discern human fingerprints left by the makers of ancient pottery. Their life’s work and labour are quite literally handed down to us

in the form of clay. This material evidence of continuity serves as a comforting reassurance that our fleeting existence as individuals is not a futile singularity, but part of a diachronic human body which leaves lasting signs of presence in the span of history. This is a soothing reflection that alleviates the hardships of our everyday life, the loss, and the despair that accompany the contradictions inherent in the human condition.

The direct connection with the artist - whether it be the distant human of the past who left their fingerprints on the amphora, or PASHIAS who situates himself amidst the museum's visitors - encourages us to move beyond considerations of time. The artist's invitation to the visitors of the Cypriot Collection in the museum is to experience in an embodied way the potential of these objects to facilitate meaningful human connections. The interactions between the audience and the artist bear witness to this capacity of the artifact to mediate social relations here and now. These interactions may range from a dynamic of spectator and spectacle to a more intimate gesture of embrace; from an acknowledgment of the artist's contribution to the human experience to simply a reawakening of an uncritical curiosity that we often bury in our adulthood.

Isn't this rediscovery of our connection to materiality and to our fellow humans the essence of overcoming alienation, and of recognizing ourselves within the objective world we construct?

Dimitris Venizelos

The article was published in Greek in Newspaper Kathimerini, Cyprus, 31/03/24 https://www.kathimerini.com.cy/gr/politismos/eikastika/1-i-sxesi-toy-anthrwpoy-me-tin-ylikotita

Towers on a Golden Coast

Competing Visions of Development on Famagusta’s Beach

by Panayiota Pyla and Dimitris Venizelos

Published in Coastal Architectures and Politics of Tourism (2023).

Abstract

Famagusta’s coastline was the center of a booming 1960s tourism industry advanced by the young state of Cyprus as a tool of national modernization and decolonization. Behind the celebrated branding of that coast as a “Mini-Miami in the Middle East” there is a complex history of concurrent inputs from United Nations and Republic of France experts, who advanced competing development strategies that resonated with Marshall Plan geopolitics and European narratives on the social and spatial potentials of leisure. This essay traces the influence of these divergent development models that promised the industrialization of leisure and urbanization of the island, and which were in turn metabolized by an intricate socio-political landscape: a looming intercommunal conflict between the Greek- and Turkish-Cypriot communities, speculative development, land ownership patterns, and state-sponsored policies. The resulting combination of modernist tower hotels with low-density distributions of tourist accommodations reshaped the relationship of the waterfront to the city fabric and also embodied the ideological and formal contradictions of that era’s tourism development. Seen in retrospect, long after the halt of Famagusta’s development as a result of the island’s division, the complex entwinements of international expertise, market pressures, and the state’s mediating tactics foreshadowed future paradigms of tourism-induced commodification of culture and nature. Research - Book Chapter

Politics in Concrete

The Case of Bafra’s Casino Resorts

Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy King’s College London

Faculty of Social Science and Public Policy

Department of Geography London, 2024

Abstract

In 2003, the administration of the ‘Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus’ opened checkpoints along the United Nations Buffer Zone -also known as the ‘Green Line’- that divides the island of Cyprus in an occupied by Turkey north, and a controlled by the Republic of Cyprus south. For many displaced Greek Cypriots this gesture of political hospitality was an opportunity to visit their dispossessed land and homes in the north. At the same time, it was an open door to an extensive landscape of hotel-casino resorts, the development of which took an unprecedented pace and scale in the early 2000s. Bafra’s Tourist Investment Zone is the flagship project of this emergent tourist landscape and an iconic manifestation of Turkey’s vision to turn the occupied territories of Cyprus into a ‘Riviera of the Mediterranean.’ With the checkpoints open, the Turkish patrons of Bafra’s Kaya Artemis Resort and Casino invited ‘Greeks’ and ‘Turks’ to visit and enjoy their ‘dream world’ which opened to the public in 2006, extending a hospitality of a dual nature: an invitation to take part in tourist consumption, but also an opportunity for political rapprochement between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. In their rhetoric, the resort was a site for peace-making on the level of civilians, through conviviality and the tourist consumption of space. This perhaps sounded appealing at the time, considering the spectacular failure of the UN-authored ‘Annan Plan’ to resolve the protracted Cyprus Problem on the level of state politics in 2004.

This dissertation will narrate a different story for Bafra’s tourist development, which offers a reading of the ongoing conflict in Cyprus as a project of alienation that is attached

to the production of space. Far from being a site for reconciliation, the development of Bafra’s Tourism Investment Zone has played an instrumental role in Ankara’s colonial project over Cyprus, especially under the leadership of the Justice and Development Party. State-sponsored strategies that produced Bafra’s tourist enclaves such as financial incentives, the erasure of existing natural landscapes and extensive construction, and the privatization and dispossession of land, have been instrumental in Turkey’s effort to redraw its political territory through spatial development. The geopolitical, however, extends beyond the state-mode of production. The political hospitality promised by the corporate leadership of Kaya Resorts is negotiated by ordinary people and their embodied interactions with the landscape, its materiality, and its representations. It is conditioned by spatial and aesthetic parameters; and is, thus, prone to the aesthetic alienations that transformed spaces like Bafra’s bay into a consumption landscape by pouring concrete on contested ground.

The Constructed and the Unspoiled

Nicosia - Cyprus

In 1962, Cyprus has its picture taken. Urbanist Eugene Beaudouin, architect and urbanist Manuel Baud-Bovy and architect Aristea Rita Tzanos comprise the group of French consultants that extensively photograph the Cypriot landscape. The team was invited by the nascent Republic of Cyprus to produce a report on the island’s future in the emerging industry of tourism. Their photographic lens highlights the island’s “unspoiled”coastal landscape as the quintessential tourist asset.

The pursue of the “unspoiled” as a characteristic of the Mediterranean landscape internalizes a contradiction: If on the one hand an idealized “unspoiled” Mediterranean coastline entailed emancipatory aspirations for the North European urbanite, as it was associated with the qualities of a “pre-urban” and “non-urban” lifestyle; on the other hand, the processes of urbanization unleashed by the pursuit of the “unspoiled” as an asset for the emerging tourist industry, paradoxically eradicated these qualities from the produced landscapes, the latters being shaped instead by processes of relentless real estate speculation.

Famagusta’s leisurescape exemplifies this contradiction. Featuring as one of Cyprus’s unspoiled beaches in the French photographic collection, Famagusta’s Golden Coast becomes, less than a decade later, the country’s

flagship leisurescape, catering to half of the island’s mass-tourism flows.Far from the 1962 Edenic visions captured by the photographic lens of the French team, the pictures of the 1970s Famagusta depict a coastal landscape densely constructed with hotels that offered all the amenities of modern urban life for the European and North American tourist. The remarkable transformations of the Golden Coast during the period of 1960 - 1974 make visible this often-concealed aspect of landscapes of leisure as operational landscapes of a post-Fordist economy. Moreover, and as they increasingly became part of the government’s agendas for economic development during the 1960s and early 70s, these developmental landscapes also embody various forms of politics, inequality and dispossession. Or even, they become spaces of contestation and conflict, despite the iconography of relaxation portrayed in promotion pamphlets and newspaper articles in Cyprus and internationally.

The multimedia exhibit titled “The Constructed and the Unspoiled” curated by the Mesarch Lab team is a reflection on these thoughts. The exhibit attempted a synthesis of photographic content from the two archives mentioned above (the Beaudouin - Baud-Bovy – Tzanos photographic collection hosted at the Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation and the Press Information Office of the Re-

public of Cyprus photo archives of the period 1960-1974) in conversation with other archival material (architectural models and publications). The parallel display of what was envisioned (extrapolating from the perspectives introduced by the French photo archive) and what was constructed until the early 70s (documented in the various photographic collections of the Press Information Office) aimed to highlight precisely this contradictory nature of the landscapes of leisure: as both developmental landscapes and as spaces permeated by utopian aspirations.

Archival Research: Dimitris Venizelos

Curators: Dimitris Venizelos, Panayiota Pyla, Petros Phokaides.

Assistant curator: Michalis Psaras

References:

Gaviria, Mario. “La producción neocolonialista del espacio.” Papers. Revista de Sociologia 3, (July 1, 1974): 201–17.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Oxford, OX, UK; Cambridge, Mass., USA: Blackwell, 1991: chapters 4-6

Lefebvre, Henri. Toward an Architecture of Enjoyment Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014. Lefebvre, Henri. Introduction to Libro negro sobre la autopista de la Costa Blanca, ed. Mario Gaviria (Valencia: Editorial Cosmos, 1973), xiii–xiv. Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Republic of Cyprus, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, French Republic— Eugene Beaudouin, Manuel Baud- Bovy, Aristea Rita Tzanos. Cyprus Study of Tourist Development. 1962. Raymond, Henri. “Le littoral et l’usager.” L’Architecture d’Aujourd’Hui, no. 175 (1974): 28.

Raymond, Henri. Les significations culturelles du littoral français. Institut d’Etudes et de Recherches en Architecture et Urbanisme, 1973.

1. L’Architecture d’Aujourd’Hui, no. 175 (1974): 28

2. Review of foreign and national newspapers on Hotel developments in Cyprus (Mesarch Lab working documents)

3. Original Model of Golden Sands Hotel by Garnett-Cloughley-Blakemore Architects. Donated to Mesarch Lab by Derry Garnett

4. “Microcosms”, Mesarch Lab working documents

5. The Golden Sands hotel Promotional video from Golden Sands hotel opening on 7 July 1973, Patrick Garnett’s archive, Mpeg video, 17:26

6. Photographs of Famagusta’s leisure strip – content from various photographic collections of the Press Information Office of the Republic of Cyprus

7. Photographs of the Beaudouin-Bovy-Tzanos archive, hosted at the Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation.

8. Workshop presentations

9. Discussion area

Bedrooms of New York

3rd Istanbul Design Biennial 22.10-10.11 2016

Galata Greek Primary School, Istanbul -Turkey

The work is accessible here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XDDrszrLxuQ&list=PLuQa3KrjTxnQGltLmjdOYiG_8Aqba78dY&index=183

At the foot of walls that enclose mansions of exorbitant luxury and exclusiveness, a different kind of home exists: informal, anonymous, minimum, ad hoc and unintentional spaces that are the “bedrooms” for thousands of invisible dwellers of New York City. The ones walked by but never actually seen, as if they have never existed at all.

These “Bedrooms” are hollow spaces, doorsteps, empty corners or deep reliefs in marble walls, without ceiling, windows, or furniture. They are random and accidental spaces, yet paradoxically typical in their characteristics: roughly

15 square feet, usually rectilinear portions of residual space right where the wall meets the pavement. Their material often differs from the surroundings, as if rejected by both the wall and the pavement, as if the hand of neglect designed them. They are the spatial manifestation of the city’s failure to satisfy even the most basic needs of some, whilst granting the ultimate desires of others; an inequality constructed and reified by design.

“Bedrooms of New York” are the antitypes to the iconic multimillion-dollar residential towers of New York City’s

skyline. They represent the extreme low in the ever-growing gap of inequality in New York’s housing market. On the top of the skyline, the other extreme; exorbitant trophy-houses, symbols of ostentatious private wealth that elevate themselves higher and higher in Manhattan’s sky. The City conceals a dark symbolism in its celebrated form that challenges our humanity: the higher private wealth finds its place in the skyline, the lower the street is.