SCENE

special edition

Whether fresh or salt, water remains vital to region’s way of life

Whether fresh or salt, water remains vital to region’s way of life

PAGE # 4

Reservoirs running dry

“Running on Empty”

PAGE # 7

LOC Water

“Lakes on the Brink”

PAGE # 10

Desalination

“Boiling Over”

PAGE # 12

Climate change

“Perfect Storm”

PAGE # 13

Lake CC State Park

“Trying to Cope”

PAGE # 14

Bays and Estuaries

PAGE # 16

Aransas County

“Water at the heart of Aeansas Co.”

PAGE # 17

San Antonio River

“Echoes along the San Antonio”

PAGE # 19

Nueces River

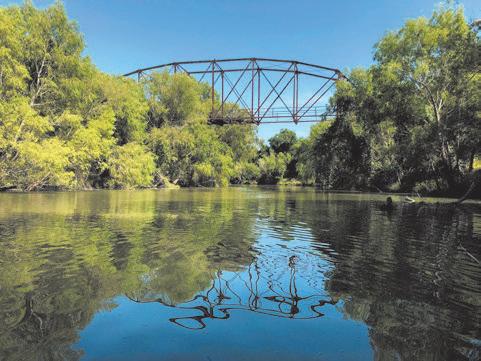

“The River That Remembers”

PAGE # 23

GCGCD Battle in Goliad County

PAGE # 26

Wetlands

“Wonders of wetlands”

By Dennis Wade Publisher, South Texas News

The phrase “water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink” from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner vividly captures the irony of abundance without utility. It describes a ship surrounded by vast, undrinkable seawater – a powerful metaphor for situations where resources abound but remain unusable, like an overload of data with no actionable insights.

In our region, some may argue water is scarce, and that’s a fair perspective – until you gaze upon the boundless Gulf of America. Water surrounds us, yet the challenge remains: how do we harness it effectively? We must act collectively and urgently to develop solutions that deliver potable water when and where it’s needed.

Water is life’s essence, and we, as a united community, hold the power to make change happen. This is not about oversimplifying a complex, pressing issue but about recognizing the need for decisive, impactful action. Too much is at stake to let Obstacles – be they bureaucratic, political, or otherwis – derail progress. The water crisis demands tactful yet resolute solutions.

This issue of South Texas SCENE explores the challenges and opportunities surrounding our water future. We hope it informs, inspires, and galvanizes action on this critical matter.

South Texas’ two lifeline reservoirs nearing historic lows as region heads toward water emergency.

By Coy Slavik cslavik@southtexasnews.com

Two reservoirs that have long sustained water for South Texas –Choke Canyon and Lake Corpus Christi – are now front and center in a deepening water crisis.

As drought tightens its grip, industrial demand surges and long‐planned safeguards stall, the region is confronting uncommonly high stakes and few good options.

Choke Canyon Reservoir and Lake Corpus Christi are the twin anchors of surface-water supply for much of South Texas. But they are now draining toward levels rarely seen in living memory.

According to Water Data For Texas, as of the middle of October, Choke Canyon stood at just 11.1 percent of its conservation capacity, with a water level of 182.70 feet – some 37.8 feet below the conservation pool. Lake Corpus Christi was measured at 14.1 percent full, with its surface at 77.41 feet, or 16.6 feet below the designated conservation elevation.

Those figures underscore a dire trend: in mid-2025, the combined level for both reservoirs had dipped under 20 percent, prompting the City of Corpus Christi and other municipalities to enter “urgent” drought Stage 3 water restrictions. Some, like Beeville, have even enetered into “emergency” Stage 4 water restrictions.

Historically, Choke Canyon has been the deeper, higher-volume reservoir, impounding up to 695,000 acre-feet of water. But its capacity advantage means little if it is largely empty. Lake Corpus

Christi, whose conservation pool sits at about 256,062 acre-feet, according to Water Data for Texas, has lost much of its buffer under sustained drawdown.

The drop in reservoir levels has revealed eerie glimpses of the past: old bridges, boathouses and roadbeds long submerged have re-emerged along the receding shorelines of Lake Corpus Christi. These relics are visual reminders of how far water has retreated.

The two reservoirs collect inflows from the Nueces River system (and its upstream tributaries) and regulate downstream release via the Nueces River and Rincon Bayou toward Nueces Bay, Corpus Christi Bay and connected estuarine systems. They function as “collector points” for the watershed feeding those bays.

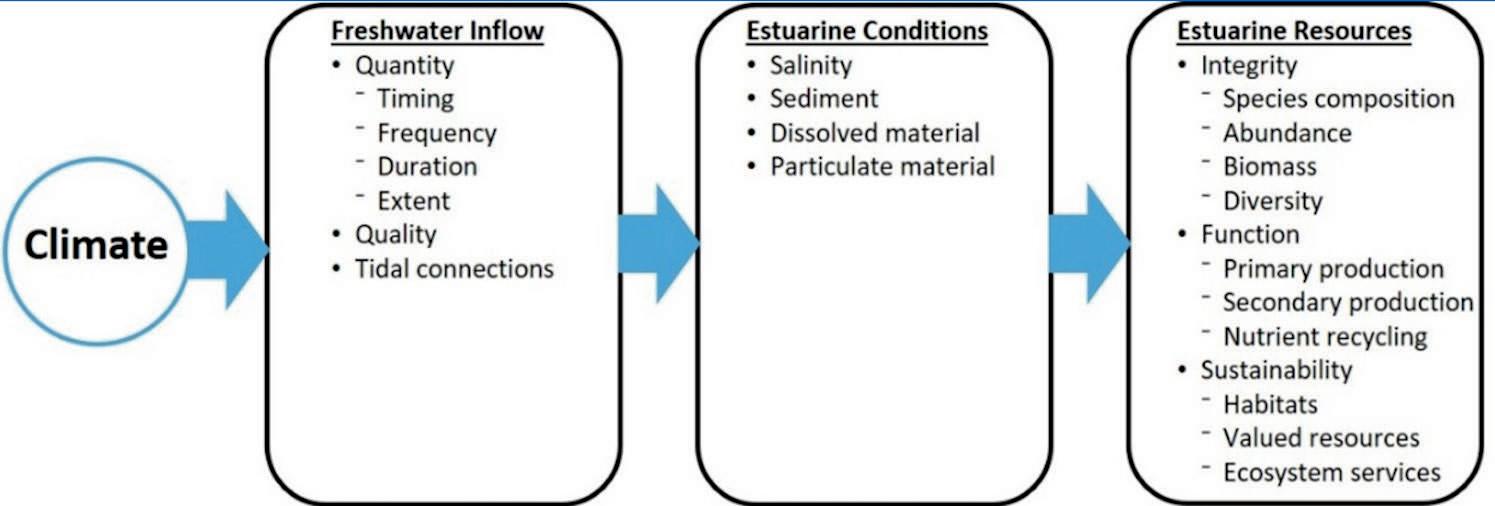

Estuaries along Texas’ Gulf Coast are dependent on freshwater inflows to moderate salinity, supply sediments and nutrients, flush pollutants, provide habitat transitions, and maintain ecological productivity.

In relatively low-exchange systems where tidal flushing is limited, the balance between freshwater input and evaporation/mixing is delicate. In the Corpus Christi Bay region, that balance is especially tenuous, according to the Harte Research Institute. When reservoir levels decline and downstream releases shrink, the coastal bays bear the consequences.

One of the most direct effects concerning experts is rising salinity in bays and estuaries. With diminished freshwater outflow, seawater intrusion or saltwater mixing becomes more dominant. That leads to elevated salt concentrations, which stress or exclude species that thrive in lower salinity conditions.

As salinity strays from ideal ranges,

certain species (juvenile fish, shrimp, oysters, sensitive invertebrates) lose competitive ground. The loss of such species can cascade through food webs.

Reduced freshwater inputs hinder the maintenance of coastal marshes, wetlands, mangroves, and deltaic systems, which rely on periodic inundation, sediment delivery, and freshwater pulses to sustain vegetative health, reduce salinity stress and suppress encroachment by more salt-tolerant species.

Researchers warn that the ecological impacts can translate into the following economic and social consequences:

• Shrimp, oysters, and crabs, which depend on nursery habitat in brackish zones, can suffer recruitment losses if salinity becomes unfavorable or habitats degrade.

• Commercial and recreational fishing yields may decline.

• Loss of estuarine habitat translates to diminished ecosystem services: less filtration, fewer buffer zones, less carbon sequestration, lower resilience to storms, reduced habitat for migratory and shore bird species.

• The health of coastal tourism, wildlife viewing, habitat conservation, and associated industries may decline.

With less flushing, tidal interchange, or freshwater cleansing, water quality can worsen. According to the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, reduced inflow exacerbates acidification

risks, as the chemical balance of estuarine waters shifts. NOAA’s coastal science programs note that low freshwater inflow is a stressor compounding acidification, nutrient loading, and hypoxia.

Part of the pressure on these reservoirs stems from how surface water was allocated in recent years. The City of Corpus Christi committed large volumes of municipal water to industrial projects even as drought pressures grew, according to the Texas Tribune.

Over time, municipal and industrial users drew heavily on the reservoirs, leaving little slack.

When the Corpus Christi City Council in September canceled the Inner Harbor desalination contract, Eric Cantu, a council member who opposed the plan, said:

“We need to find other projects to get the refineries water. This project has gotten so political, so nasty. Threats. It’s just unbelievable.”

At the same meeting, Kara Rivas, spokesperson for Flint Hills Resources, responded:

“This would force the shutdown of at least some aspects of our operations,” she said. “Industry simply cannot compete long-term without reliable water resources.”

Another industrial representative, Robert Landeg of ExxonMobil, warned of exodus from the region:

“I’m going to tell my boss, ‘Hey, transfer me out.’ I’m going to sell my house, because it’s going to come,” he said.

With reservoir levels dangerously low, city officials throughout South Texas have shifted into crisis mode, pressing interim measures even as longer-term options languish.

Much of South Texas is phasing in severe conservation and usage restrictions. As the reservoirs declined, outdoor watering bans, tighter daily limits and escalated drought stages have taken hold.

On the longer horizon loomed the Inner Harbor seawater desalination plant, first proposed years earlier. The original concept would draw Gulf of Mexico water, remove salt, and supplement downstream supply to relieve pressure on Choke Canyon and Lake Corpus Christi. But according to the Texas Tribine, the cost escalated dramatically – from initial $160 million in 2019 to $1.2 billion by 2025 – and the City of Corpus Christi ultimately scrapped the contract.

In that context, environmental and permitting hurdles had long delayed the project. The Tribune reported that the U.S. EPA flagged issues with the state permit, questioning its compliance with the Clean Water Act and protections for aquatic life.

According to experts in the field of hydrology, the predicament at Choke Canyon and Lake Corpus Christi carries ripple effects across ecology, industry, municipal reliability and regional planning.

Officials estimate that without new supply sources, the region could face an emergency by December 2026 – one that might force a 25% reduction in industrial water allocations. In a region dependent on petrochemical, plastics and refining op-

erations, such cuts could have sweeping consequences. With reservoir releases to coastal bays largely halted, estuarine systems may be deprived of fresh inflows needed to flush salinity and support marsh habitat. Over time, this may erode biodiversity, fish nurseries and the natural resiliency of coastal ecosystems.

Also industrial scale is central to the South Texas economy. If water risk becomes a disqualifier, new investments might be deterred. Already, some industry leaders have hinted at relocation or contraction, warning that unreliable supply undermines competitiveness.

Ordinary consumers face watering bans, rate hikes and the possibility of more stringent rationing.

Experts say relying on Choke Canyon and Lake Corpus Christi alone is no longer viable. Possible options proposed include:

•Smaller, modular seawater desalination units rather than one large facility.

•Expanded brackish groundwater treatment systems inland.

•Advanced water reuse/potable recycling programs.

•Interbasin transfers or supplemental pipeline imports.

The reservoirs’ decline shows no near reversal, and some recent reporting from climatologists suggests that by year’s end, Choke Canyon and Lake Corpus Christi may fall toward 10 percent capacity, leaving city officials and residents downstream wondering where relief will come from – rain, reform, or nearby saltwater?

Worsening water crisis takes its toll on towns, tourism, and hope.

By Dr. Janet Cunningham theprogress@southtexasnews.com

Live Oak and McMullen counties continue to experience a severe and prolonged drought that has drastically lowered water levels in both Choke Canyon Reservoir and Lake Corpus Christi.

Without significant rainfall, experts warn that Choke Canyon could be nearly empty within 14 months, with Lake Corpus Christi not far behind.

Businesses, tourism suffer as lakes shrink

Choke Canyon’s water level has fallen well below historical averages. In October 2024, the reservoir was at 18.2% capacity; one year later, it has dropped to just 11.2%. Choke Canyon State Park officials and longtime residents recall when the waterline supported vibrant fishing and recreation.

Choke Canyon’s low lake levels have severely impacted camping reservations. (Photo by Dr.

Now, boat ramps are closed, docks no longer reach the water, and requests for camping spots have diminished.

Pamela Varnon and her husband, Jeffrey Lothringer, own Arrowhead RV Park in Calliham near the state park entrance.

“Everything has been affected,” said Varnon. “Our business is down at least 70 percent since the fishing tournaments and Audubon Society visits for wildlife viewing have stopped.”

Residents who once worked in lake-related jobs have moved away, and the updated Calliham Store and Restaurant never opened.

The drought’s impact extends to surrounding towns and small businesses. Angie Ponce, executive director of the Three Rivers Chamber of Commerce, said, “The low lake levels have definitely impacted our community here in Three Rivers. Local businesses that rely on tourism – such as restaurants, lodging, and outdoor recreation – have seen a noticeable slowdown. At the same time, our business owners are resilient and continue to support one another as we all hope for much-needed rain to restore the lake and bring visitors back.”

Water restrictions tighten across region

The City of Corpus Christi, which uses Choke Canyon and Lake Corpus Christi for its municipal water supply, has modeled scenarios predicting possible water emergencies if the drought persists.

The Western Reservoir System, which includes both lakes, could reach critical levels by next month, and Choke Canyon may be empty by January 2027 without substantial rainfall.

Local governments have responded with new ordinances and restrictions.

Three Rivers, which draws most of its water from Choke Canyon, has implemented Stage 4 Critical Water Shortage Conditions, prohibiting residents from watering lawns, washing cars, or filling swimming pools. While residents are not in immediate danger of losing access to drinking water, officials urge strict conservation.

City Administrator Thomas Salazar explained, “The City of Corpus Christi is required by the State of Texas to release water that is naturally flowing.”

This means up to 30 cubic feet per second can be released for Three Rivers. Salazar said the city is also operating pumps and can rely on wells if surface water runs dry.

For some, the drought has been devastating.

Wayne Curry, owner of Curry’s Nursery in Three Rivers, said, “This is the slowest late summer and fall that we’ve had in over 40 years in business.”

Although floral sales are keeping the business afloat, tree and bedding plant sales have nearly stopped.

“We’re keeping plants alive with watering cans because sprinklers aren’t allowed,” he said.

A summer of below-average rainfall and triple-digit heat has worsened conditions. Even with heavy rains in the Uvalde area earlier this summer, local creeks and feeder streams that normally replenish the reservoir have slowed to a trickle. Without a sustained rain system or a tropical disturbance in the Gulf, the outlook remains grim. Hydrologists caution that only months of consistent

rainfall, not isolated storms, will restore the lakes to healthy levels.

Stephen Emerson, Water Reservoir Supervisor for the City of Corpus Christi, said the last time the lake was full was in 2007, and it has steadily declined ever since, now reaching its lowest point on record. Old-timers recall that Choke Canyon Reservoir, constructed between 1976 and 1982, never quite met expectations.

The Frio River, originating in Real County within the Edwards Aquifer drainage area, feeds the reservoir, but much of that water is absorbed before reaching the lake. Then the Frio, Atascosa, and Nueces rivers converge at Three Rivers before flowing into Lake Corpus Christi.

The situation is beginning to take its toll on the community. “Everything is dying – trees, plants, and even the grass. Where there is grass, it’s crunchy. I look at the weather forecast, and there’s no significant rain in sight,” said one local resident.

Adding to the discouraging outlook, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center forecasts a “La Niña” winter, typically bringing above-average temperatures and drier conditions across Texas.

With no end to the drought in sight, communities across Live Oak and McMullen counties are doing what they can: conserving water, adjusting to changing conditions, and, as many residents say, continuing to “pray for rain.”

City of Corpus Christi halts

$1.2 billion Inner Harbor desalination project as South Texas cities weigh costly options to fight water scarcity.

By: Landan Kuhlmann, Editor

thenewsofsanpatricio@southtexasnews.com

As South Texas and the Coastal Bend continue to undergo severe drought conditions, the question of where viable water will come from persists as the largest uncertainty amid a host of challenges.

Many areas of South Texas are under severe drought, sparking debate about how best to preserve and produce the water residents need for daily life — one leading proposal being desalination.

The topic of desalination has long been contentious. Environmental groups have opposed proposed plants on multiple fronts, citing concerns about brine discharge, energy consumption, and ecological effects.

Supporters, however, argue it remains one of the most promising long-term solutions to the region’s growing water scarcity.

council halts

That debate reached a turning point in early September. During a Corpus Christi City Council meeting on Sept. 2, council members voted 6-3 against an amendment that would have allowed Kiewit Offshore Services in Ingleside to begin building a $1.2 billion desalination plant in the Inner Harbor — a project years in development.

The measure would have authorized Kiewit to proceed with design and construction services up to 60% completion, but following hours of heated debate, the majority vote effectively put the project on hold and froze funding that had been raised over recent years.

Despite the setback, Corpus Christi officials continue exploring desalination as a critical water supply option. Accord-

ing to an Oct. 13 report from KIII-TV, city leaders met with the Nueces River Authority (NRA) to discuss potential alternatives.

One proposal involves purchasing the Corpus Christi Polymers desalination plant for roughly $650 million.

Another would require the city to pay a $2.7 million non-refundable service fee to secure water from the NRA’s Harbor Island desalination plant.

Both options remain under negotiation, according to local reports.

New proposal emerges for La Quinta Channel Project

Following the council’s decision on the Inner Harbor Project, San Patricio County Municipal Water District (SPMWD) General Manager Brian Williams sent a letter to Corpus Christi City Manager Peter Zanoni requesting negotiations to transfer rights to the La Quinta Channel Desalination Project — another facility developed alongside the Inner Harbor project — from the city to the water district.

La Niña, thirstier atmosphere predicted to extend into 2026.

By Coy Slavik cslavik@southtexasnews.com

Thealarming descent of lakes, reservoirs, rivers, and creeks are a stark sign of how the South Texas drought has deepened under the twin pressures of prolonged rain deficits and intensifying heat.

The drought gripping South Texas is not simply a shortfall of rain. Climatologists point to a confluence of factors: a developing La Niña in the Pacific, a “thirsty” atmosphere amplified by warming, and weaker runoff from upstream watersheds already strained by historic dryness.

Historically, La Niña phases tend to suppress winter rainfall over Texas, and this one is expected to linger into early 2026, reducing the chances of meaningful recharge during the cooler months.

Expert insight: climate change tightens the grip

The climate change South Texas is experiencing was foreseen by experts years ago.

“From here on out, it’s going to be very unusual that we ever have a year as mild as a typical year during the 20th century,” Texas State Climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon told the Texas Tribune in 2021. “Just about all of them are going to be warmer.”

Across the southern reaches of the state, the Evaporative Demand Drought Index (EDDI) has registered higher-than-normal values for

much of 2025, indicating that the atmosphere is pulling moisture from soils and open water faster than in previous years. That accelerates reservoir drawdowns as larger proportions of inflow are lost to evaporation.

Meanwhile, downstream river gauges in the Nueces and San Antonio basins show suppressed flows, with some estuary sections turning saltier and drier.

The Corpus-Choke system rests within the larger San Antonio-Nueces basin, and tributaries like the Frio, Atascosa and Nueces rivers have delivered only sparse runoff during major rainfall events. Any excess rainfall is often lost to intense heat or trapped in parched soils before it can flow downstream. Seasonal rains in 2025 have been erratic and spotty, failing to deliver widespread, sustained wetting across headwaters.

Climate change amplifies natural extremes

While climate change does not “cause” every drought, scientists say it has amplified the natural swing. Nielsen-Gammon and others argue the extra heat “loads the dice” – making extreme droughts more frequent, more intense, and slower to recover from.

Texas’ rising trend in 100-degree days and seasonally warmer averages means more water is lost even when precipitation resumes. Utilities and state water resources agencies now routinely factor evaporation and soil moisture stress into longer-range planning.

Looking ahead to 2026, climatologists outline two broad scenarios.

The more probable, and less hopeful, path, according to climatologists, is one in which

La Niña holds through the winter and fades to an ENSO-neutral pattern by spring. Under that scenario, South Texas would likely see warm and dry to near-normal winter conditions, with only modest inflows into the reservoirs. Recovery would be slow, and the risk of persistent water stress would remain high.

In a more favorable but less likely scenario, late-season Gulf moisture surges or strong cold front systems could push across South Texas, delivering slow-moving, soaking rains that bolster upstream flows. But even in that case, such episodic events may only stabilize the decline rather than reverse it completely. Planners caution against relying on rare deluges in a warming climate.

Climatologists note that even when precipitation returns, the system’s deficit is so large that it would take many weeks of above-average rain to fully recover. He stresses that partial rebound will likely be the norm; full recovery to pre-drought levels could require multiple seasons of favorable patterns.

Meanwhile, municipalities, agricultural interests and environmental stakeholders must manage within tighter margins.

In short, South Texas has entered a phase where it will not be enough just to “wait for rain.”

“Reducing climate change is a global problem, but dealing with climate change is a local problem,” Nielsen-Gammon said in a 2024 climatology report.

Subhead: Lake Corpus Christi’s receding shoreline leaves boat ramps dry, campsites empty, and tourism struggling to stay afloat.

By Landan Kuhlmann

thenewsofsanpatricio@southtexasnews.com

Muchhas been made of the water crisis and drought condition currently plaguing the majority of South Texas and the Coastal Bend. But it effects go beyond the simple need for water, including the operations and methods of a regional state park in Mathis.

Lake Corpus Christi State Park sits on the 21,000-acre Lake Corpus Christi, and typically brings in hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. Typically, park general manager Kelly Malkowski said the park’s busiest times are between Easter and Labor Day, with traffic slowing down outside that period.

Even relative to that, however, she said the drought’s effects have been felt by the park in more ways than one due to the lowered volume of Lake Corpus Christi. According to Water Data For Texas, Lake Corpus Christi was measured at 14.1 percent full, with its surface at 77.41 feet - or 16.6 feet below the designated conservation elevation - as of the middle of October.

Subsequently, Malkowski said the park has seen a slowdown of approximately 50,000 visitors as drought conditions have worsened. That said, Malkowski said there has been a small ancillary benefit to fewer visitors, as it has allowed the park to focus on improvements such as updates to its boat access ramps and more for when another uptick comes.

She said there have also been more frequent sightings of the park’s wildlife with fewer visitors.

“With lower lake levels we have seen a decrease in park visitation, but we have seen a

large increase in wildlife viewing,” she said. “With fewer people in the park it is more quiet, so sighting of deer, bobcats, and so many birds are happening more regularly.”

Wildlife affected

That wildlife and other animals supported by Lake Corpus Christi and the park’s ecosystem is another factor that has needed to be taken into account, according to Malkowski. According to the park’s website, Lake Corpus Christi State Park supports birds such as the black-bellied whistling duck, purple gallinule, white-winged dove, pauraque, long-billed thrasher, white-eyed vireo, pyrrhuloxia, and black-throated sparrow. There are also species of animals such as javelinas, white-tailed deer, bobcats, and more which depend on the land and river to help survive.

tinue to do so. Lake Corpus Christi, whose conservation pool sits at about 256,062 acrefeet, according to Water Data for Texas, has lost much of its buffer under sustained drawdown.

“Because the water is low, we have adjusted how we mow and maintain some sections of the park to provide more cover and routes that wildlife can safely make it to the waters edge,” she said.

Making the best of the situation

So even though the park has seen fewer visitors, it appears as though the park is attempting to make the best of the current conditions - for both its visitors and resident animals - until improvements can be made, with the hope to hit the ground running when it returns.

Lake

(Photos courtesy of Texas Parks & Wildlife Department)

For more information about Lake Corpus Christi State Park, visit the park’s website at tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/lake-corpus-christi.

Estuaries are turning saltier, hotter, and less alive as drought grips Texas coast

By Coy Slavik cslavik@southtexasnews.com

As drought grips South Texas, its potentially devastating reach extends all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, where bays and estuaries – “the nurseries of the coast” – are struggling to survive a cascade of ecological stress.

Dr. Paul A. Montagna, endowed chair for hydroecology at the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M-Corpus Christi, said the shortage of freshwater inflow from rivers emptying into bays due to the current drought conditions creates a deadly imbalance.

“The thing that happens the most is the salinity goes up,” Montagna said. “And there’s another interesting problem, and that is particularly in the summer, because the water is warmer. The solubility of oxygen in water is a function of salinity and temperature. So as the water, particularly in the summer, gets saltier and hotter, it holds less oxygen.”

Montagna said the combi-

nation has created growing areas of hypoxia – low-oxygen zones where fish and invertebrates struggle to survive.

“We’ve seen it in Corpus Christi Bay for a really long time,” he said. “We’re now starting to see it in other bay systems like Aransas Bay as well. So it’s becoming a pretty common problem.”

Salinity, oxygen, and chemistry of decline

Montagna, who has spent nearly four decades studying Texas estuaries, said drought drives a chain reaction that goes far beyond higher salinity levels.

“It’s not just the salinity itself,” he said. “It’s the combination of salinity and the high temperatures, particularly in summer. When the salinity and the temperature go up like that, it also changes the pH, and the bay actually becomes more acidic. That affects organisms that make hard shells out of carbonate –for example, oysters and blue crabs.”

Perhaps the most alarming consequence, Montagna said, is the breakdown of the estuaries’ “nursery function,” where young shrimp, fish and

crabs once found refuge and food in brackish waters.

“It’s real common for coastal organisms to have what we call an estuary-dependent life cycle,” he said. “They spawn offshore or right in the pass, and then the babies migrate in at the tides. They like to go to the upper reaches of the bay, closer to the river mouth, where salinities are lower.”

Those upper reaches, which were once rich in nutrients from the inflow, are becoming too salty and inhospitable.

“When you have lower salinities, you usually have more nutrients, because the river water is carrying the nutrients,” Montagna said. “The nutrients promote plant growth. So you have more plankton in the water – you’ve got food – and the plants and the marsh areas provide a place to hide out. So you’re less likely to get eaten by a bigger fish if you’re a little fish or a little shrimp.”

Without freshwater inflow, that protective nursery breaks down.

“That nursery function starts to break down as well during droughts,” he said.

Droughts disrupt the reproductive cycle

According to Montagna, the drought’s reach extends into the reproductive cycles of key species.

“A lot of organisms require a low salinity range in order to reproduce or to trigger reproduction,” Montagna said. “It’s real common after we get a flood event and the salinities go down real low, that triggers a lot of organisms to reproduce, particularly oysters. Nearly all the clams in the bay do this, by the way.

“When the pH is getting lower, it’s harder for a baby oyster to build its shell. There’s less food in the water, because there are fewer nutrients creating the phytoplankton that they eat. It’s real common to lose a whole year class of oysters during a drought, particularly if there’s a strong one in the fall.”

‘The bays will green up again’

Yet, Montagna says nature’s resilience remains remarkable if given time and freshwater.

“Here’s the good news,” he said. “The weather changes. It will rain again someday.

“I’ve been doing long-term

studies in our area going way back to 1986 – that’s 39 years

and I can tell you that sometimes it takes six months, sometimes it takes a year, sometimes it takes two years, but things all come back. As long as we don’t kill the bays, they will come back. It’s kind of like your lawn after a rainfall – the bays will do the same thing. The bays will green up, literally.

“When it does rain, it’ll bring in new nutrients that fuel the food web, build more plant life, particularly the phytoplankton in the water column as the main fuel for most of the organisms. And things will come back.”

Montagna pointed to recovery after Hurricane Harvey in 2017 as proof.

“Right after the storm, it really devastated the bay,” he said. “Everything I wanted to measure was zero or gone. Things got killed or swept out of the bays by the huge floods. But by the next April or May, we saw a huge bloom. So some will come back as long as we don’t kill the bays.”

However, Montagna cautioned that not all systems can bounce back.

“I do believe you can kill a bay, particularly the secondary bays, the ones close to the river mouths,” he said. “That is something to worry about.”

Montagna cited Baffin Bay as an example of a system in trouble.

“Baffin Bay is commonly hypersaline now,” he said. “Hypersaline means saltier than seawater. All the coastal organisms are adapted to live in what we call brackish waters – where the water ranges from fresh to ocean salinities. But when things start living above ocean salinities, there are very few things that can tolerate those kinds of conditions.”

Montagna said the historic loss of oysters in the Nueces Bay system stands as a warning.

“In the early 1900s, Nueces Bay was the biggest oyster producer in the state of

Texas,” Montagna said. “The salinities were just right – before we had any dams or water diversion projects on the Nueces River. And today, of course, it can’t produce oysters at all. That’s a good example of how we can kill a bay.”

To prevent that fate elsewhere, Montagna has promoted a management strategy focused on keeping at least part of a bay system alive during drought.

“I’ve been promoting this idea over the last few years of trying to move toward what I would call a focused flow management strategy,” he said. “We try to keep those estuary areas of the bays a little wet during the droughts so that when it does rain again, or average conditions come back, they can quickly repopulate.”

Montagna explained that maintaining minimal flows near river mouths can sustain resident populations without trying to dilute the salinity of entire bays.

“If you think about it, that would take a lot less water than trying to dilute the salinity in all of Corpus Christi Bay,” Montagna said.

‘An unprecedented era’

Still, Montagna admits the present drought is different.

“The reservoirs have never been as low as they are right now,” he said. “I’m really not aware that we’ve ever come out of an El Niño–La Niña period where the reservoirs didn’t increase their elevation. It’s just remarkable.

“There’s no reason to think we’re going to have average rainfall next year. So certainly over the next nine months, that sounds scary to me.”

Despite the uncertainty, Montagna keeps hope in the Gulf’s resilience.

“We live on the Gulf Coast. We live in Texas,” he said. “We’ll probably have to wait until next spring to recover.

Hopefully we get good spring rains this year – maybe the next fall – but we’re really in an unprecedented era.”

This map shows the major estuaries along the Texas Gulf Coast.

About Dr. Paul A. Montagna

* Title: Endowed Chair for Hydroecology, Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies, Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi

* Focus: Estuarine ecology, freshwater inflows, and long-term monitoring of Texas bay systems

* Publication: Freshwater Inflow to Texas Bays and Estuaries (Open Access, 2025)

Experts warn that protecting freshwater inflows and bay health is critical to the county’s economy, environment, and future prosperity.

By Walter Perry rockport@southtexasnews.com

From the calm waters of Little Bay to the open Gulf of Mexico, water remains central to Aransas County’s identity and livelihood.

The bays, estuaries, and marshes that surround the community sustain tourism, commercial fishing, and recreation — the foundation of the local economy.

But as drought intensifies across South Texas and upstream water demands continue to grow, scientists warn that the region’s most valuable natural resource is under increasing strain.

“Our economy is built on the health of our bays and estuaries,” said Dr. Lucas Gregory, an environmental scientist with the Texas Water Resources Institute who studies Texas water systems. “You’re killing the shrimp industry. You’re killing the oyster industry. You’re killing all of the seafood industry, essentially.”

Billions of dollars in tourism, fishing, and seafood production depend on the delicate balance between fresh and salt water. Gregory and other experts say that protecting the quality and consistency of that freshwater

supply is now a matter of both economic survival and environmental stewardship.

Environmental challenges are already visible close to home. Little Bay — a small, man-made embayment at the heart of Rockport’s tourism corridor — has faced recurring problems with water quality, runoff, and limited circulation. Scientists have linked those conditions to stormwater drainage from surrounding neighborhoods and businesses.

Gregory said the issues in Little Bay mirror a broader statewide struggle: managing how urban development and stormwater systems affect natural waterways.

“Those storm events generate a lot of runoff, and they wash a lot of contamination into the waterways,” he said. “It’s a diffuse-source problem — it doesn’t come from one single pipe but from countless small actions across the community.”

Local leaders say tackling the problem will require openness, collaboration, and long-term planning.

“An informed community is an empowered community,” Gregory said. “Transparency and science-based solutions are essential.”

As Texas’ population continues to grow, the competition for water has become more intense. Mu-

nicipal and industrial development in South Texas now draws heavily on rivers that ultimately feed the coastal estuaries.

Gregory cautioned that “nobody’s bringing any more water with them when they show up to the state.” That reality, he said, underscores the importance of coordinated water planning that includes the coast.

“When you cut off the inflow, you’re cutting off the life support system of the bays,” Gregory said.

Aransas County officials and conservation groups have urged the state to weigh the needs of coastal ecosystems when allocating water rights upstream. Without adequate flows, experts warn, both marine life and the businesses that depend on it will suffer.

For Gregory, the story of water is not confined to lakes and bays — it’s a part of everything people use and consume. “Water is the backbone of our civilization as a whole,” he said. “And to be frank, we’ve abused the heck out of it over the years and don’t respect it to the point that we need to.”

From agriculture to manufacturing, water is a hidden ingredient in nearly every product. The water used to grow feed for cattle, process meat, or cultivate cotton for denim is immense. Gregory

calls it “embedded water,” meaning that every burger, pair of jeans, or vehicle represents thousands of gallons of water consumed in its production.

“The biggest challenge we have is just people’s general knowledge and awareness and understanding of the importance of our water resources,” he said.

That awareness, Gregory added, is key to meaningful change. Reducing household waste, repairing leaks, and using water-efficient landscaping can conserve thousands of gallons over time — easing pressure on local systems and helping sustain bay health.

A call for conservation, community action

Local experts say the path forward will require a shared commitment to conservation and advocacy. Measures such as drought-tolerant landscaping, improved stormwater infrastructure, and public education on runoff management are already being discussed at local and regional levels.

Residents are also being urged to participate in state water-planning meetings to ensure coastal interests are represented.

“The water that surrounds us is not just a scenic backdrop; it’s our past, present, and future,” Gregory said. “Our prosperity and identity are inextricably linked to the health of our water.”

faith, struggle, and renewal, the river has remained the enduring lifeline of Goliad and Karnes counties.

By Dylan Dozier dylan@southtexasnews.com

TheSan Antonio River is, and always has been, the

quiet thread of continuity con necting millennia of human history across what is now Bexar, Wilson, Karnes, and Goliad counties.

It has quenched thirst, nourished crops, anchored settlements, and carried the stories of every civilization that has risen along its banks. In Karnes and Goliad counties especially, the

plains of South Texas. Along its banks, early hunter-gatherers camped near the headwaters, now located on the campus of the University of the Incarnate Word. Those first inhabitants believed the San Antonio Springs were sacred – a portal to the underworld.

mere

geography but of endurance – of how a body of water continues to shape culture, economy, and identity across the centuries.

Twelve thousand years ago, the river flowed broad and clear – a 200-foot-wide ribbon of motion cutting through the semi-arid

“The springs were sacred, and the springs fed the river,” says Dr. Harry Shafer, curator of archeology at the Witte Museum. “And the river was a source of life, a source of resources – fish, water – and it also attracted game.”

Centuries later, Spanish explorers were drawn to the same waters. They recognized what Native people already knew –that life along the river meant survival. Between 1718 and 1731, the Spanish built five missions along the San Antonio River, linking the sacred and the practical through an elaborate system of acequias. These irrigation

SAN ANTONIO | continued on page 18

channels, inspired by those in southern Spain, brought the river’s life-giving water to fields and communities for more than 150 years.

By the late 19th century, the relationship between the city and its river began to change. Artesian wells drilled into the Edwards Aquifer shifted San Antonio’s water reliance underground, and the river’s flow diminished to a trickle. Then, in 1921, a catastrophic flood reminded the city of its dependence on – and vulnerability to – the river.

The San Antonio River swelled 12 feet over downtown streets, devastating the community but also inspiring modern flood control and a new era of civic imagination. What began as a practical concern evolved into one of the state’s most ambitious examples of river restoration and urban design: the San Antonio River Walk.

But downstream, the story unfolded differently.

Goliad and Karnes: Where history runs deep

In Goliad County, the San Antonio River’s history is written in stone and blood. It was along this river that Presidio La Bahía was established, anchoring Spanish settlement in the region and serving as the stage for one of the Texas Revolution’s most tragic events – the 1836 Goliad Massacre.

The river that had sustained centuries of life also bore witness to profound sacrifice. Today, its banks near Goliad State Park and Historic Site are quieter, shaded by oak and pecan trees, with canoes and kayaks gliding where soldiers once stood. The six-mile Goliad Paddling Trail offers modern visitors a peaceful way to engage with this storied waterway – a journey through both nature and history.

Farther upstream in Karnes County, the river winds through the brush country, feeding farms, supporting wildlife, and under-

pinning local economies. In the mid-20th century, Karnes and Goliad became integral to the San Antonio River Authority’s mission of conservation and flood control. When the River Authority expanded its jurisdiction in 1961, it did so with the understanding that protecting the river’s upper reaches meant little if its lower basin was left behind.

Thirteen flood control dams were eventually constructed in Karnes County alone, helping

Recreational spaces such as the Goliad Paddling Trail and Branch River Park transformed the area from historic landmark to living ecosystem.

By the early 2000s, the river’s role had evolved once again. The San Antonio River Improvements Project (SARIP) – a massive restoration initiative – reimagined the river not just as a utility but as a living corridor connecting urban and rural Texas. In Karnes and Goliad, the River Authority continued expanding access and

The River Authority’s work through the 1970s and beyond brought not just infrastructure but stewardship. In the decades that followed, scientific studies, water quality initiatives, and park developments took root.

Goliad State Park saw new facilities built in partnership with the River Authority and Texas Parks and Wildlife.

tivity, and wastewater concerns forced the River Authority to take on a new role: environmental guardian. Monitoring programs were established along Highway 72 and throughout the basin to track changes in water quality. Educational workshops and ordinances helped local communities manage growth without compromising the river’s health.

In many ways, this era mirrored the old tension – between using the river and protecting it.

Yet even amid industrial development, the river has continued to flourish as a place of recreation, restoration, and reflection. In recent years, projects like the Saspamco Paddling Trail, park developments in Wilson and Goliad counties, and ongoing watershed partnerships have reinforced a truth that’s as old as the river itself: water connects everything.

The future of the San Antonio River – especially in its lower basin – depends on the choices made today. The River Authority’s sustainability initiatives, from stormwater improvements to rain gardens and erosion control projects, aim to ensure that clean water continues to flow through Karnes and Goliad counties for generations to come.

Low-impact development practices and watershed protection plans are redefining how communities grow, blending technology with tradition.

San Antonio River Nature Park in Wilson County to paddling trails and water monitoring programs that stretch through the lower basin.

New challenges, new currents

Then came the oil boom. The rise of the Eagle Ford Shale in the 2000s brought both prosperity and pressure to the watershed. Pipeline crossings, drilling ac-

The river that once sustained nomadic tribes now supports modern towns. It has survived droughts, floods, and the shifting priorities of civilizations. Through every era – sacred, colonial, industrial, and modern – it has remained a symbol of resilience.

Standing along the banks near Goliad, where sunlight glints off the slow-moving current, it’s easy to feel the continuity. The river is still here. Still flowing. Still teaching.

The San Antonio River has always been more than water. It is time itself – flowing through the heart of South Texas, carrying the stories of those who came before and whispering to those yet to come.

Tquietly,high in the limestone hills of the Edwards Plateau, where trickling springs and hidden canyons feed a current that will wind more than 300 miles before it reaches Nueces Bay. To those who live along its lower stretches – in McMullen, Live Oak, and San Patricio counties – the river is not merely a feature of the landscape but a living thread, one that ties together centuries of conflict, survival, and renewal in the South Texas brush country.

For as long as people have lived here, the river has shaped their way of life. Long before Spanish explorers arrived and called it the Río de las Nueces – the River of Nuts, for the wild pecan trees that shaded its bends – the stream served as a lifeline for Indigenous communities. They followed its meandering course across the semi-arid plains, leaving behind the traces of trails that would one day guide Spanish soldiers, Mexican settlers, and Anglo ranchers. The river’s bends and crossings became the earliest roads through this coun-

Mexico. Even after the bound ary was pushed south to the Rio Grande, the “Nueces Strip” remained contested land, a rough expanse that demanded resilience from anyone who tried to tame it.

The river’s legacy is also written in blood. In August 1862, as the Civil War tore through the South, a band of German Texans opposed to the Confederacy tried to flee to Mexico along the Nueces. Confederate forces intercepted them, killing 19 in what became known as the Nueces Massacre. The tragedy still lingers in Texas memory, its victims memorialized by the Treue der Union monument – one of the first Civil War memorials in the state – a reminder that even in remote corners of the river valley, history’s currents ran deep. In the 20th century, the Nueces again proved both generous and cruel. When oil and gas were discovered along its banks, the little town of Calliham in Live Oak County sprang up almost overnight, its fate tied to the riv-

through the mesquite and brush, feeding into the river when rains come, only to vanish again under the heat of a South Texas summer. The river’s flow depends on the land’s generosity – a reminder that in this country, water has always meant power, survival, and the promise of renewal.

Farther downstream, in San Patricio County, the Nueces becomes something else entirely – a river of memory. Along its lower banks, Irish settlers established the town of San Patricio de Hibernia in 1831, bringing with them the hopes of a new colony. Only a few years later, during the Texas Revolution, the Battle of Lipantitlán raged along its shores, where Texian forces clashed with Mexican troops and claimed a key victory for independence. The same waters that had nourished the Irish colony would later carry soldiers, wagons, and stagecoaches along the San Patricio Trail, linking Corpus Christi to San Antonio – a vital artery for trade, travel, and war.

The river endures

The river has long demanded respect, and institutions rose to meet that challenge. In 1935, the Texas Legislature created the Nueces River Authority, grant ing it wide power to protect and manage the basin’s water re sources. With offices in Uvalde and Corpus Christi, the author ity now oversees flood control, wastewater management, and conservation projects across 22 South Texas counties. Its work –from maintaining Choke Canyon Reservoir to monitoring water quality under the Texas Clean Rivers Program – reflects an evolving understanding of what the river means today: not just a boundary or a resource, but a shared inheritance.

Even now, as droughts intensify and growth pressures the land, the Nueces remains the quiet heartbeat of the region. In McMullen, Live Oak, and San Patricio counties, its waters still feed pastures, sustain wildlife, and mirror the wide sky. It carries the memory of those who fought, farmed, and prayed along its banks – from Native trails to Spanish missions, from the oil rigs of Calliham to the fishermen

aerial view shows the marshes surrounding Nueces Bay, where the freshwater of the Nueces River converges with the Gulf of Mexico. This estuarine ecosystem supports diverse wildlife and is vital for local fisheries.

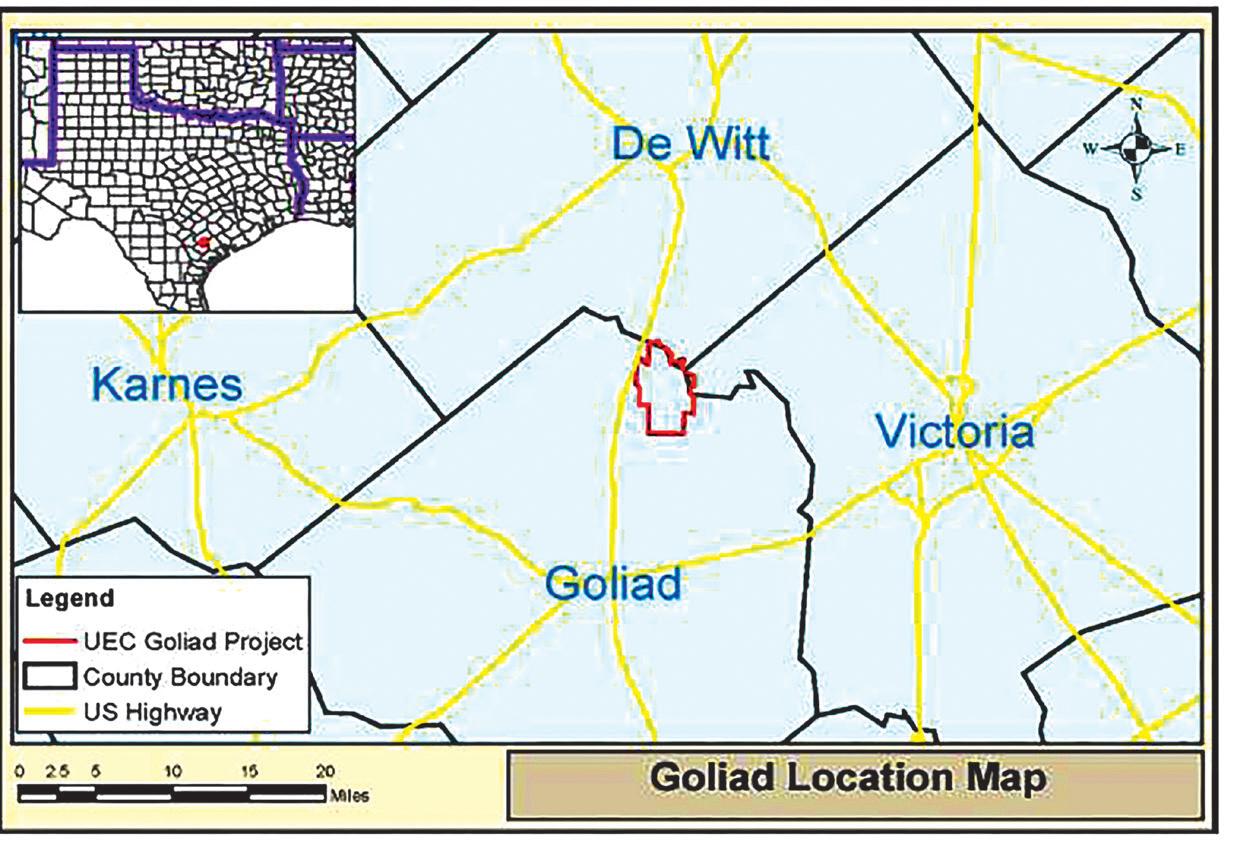

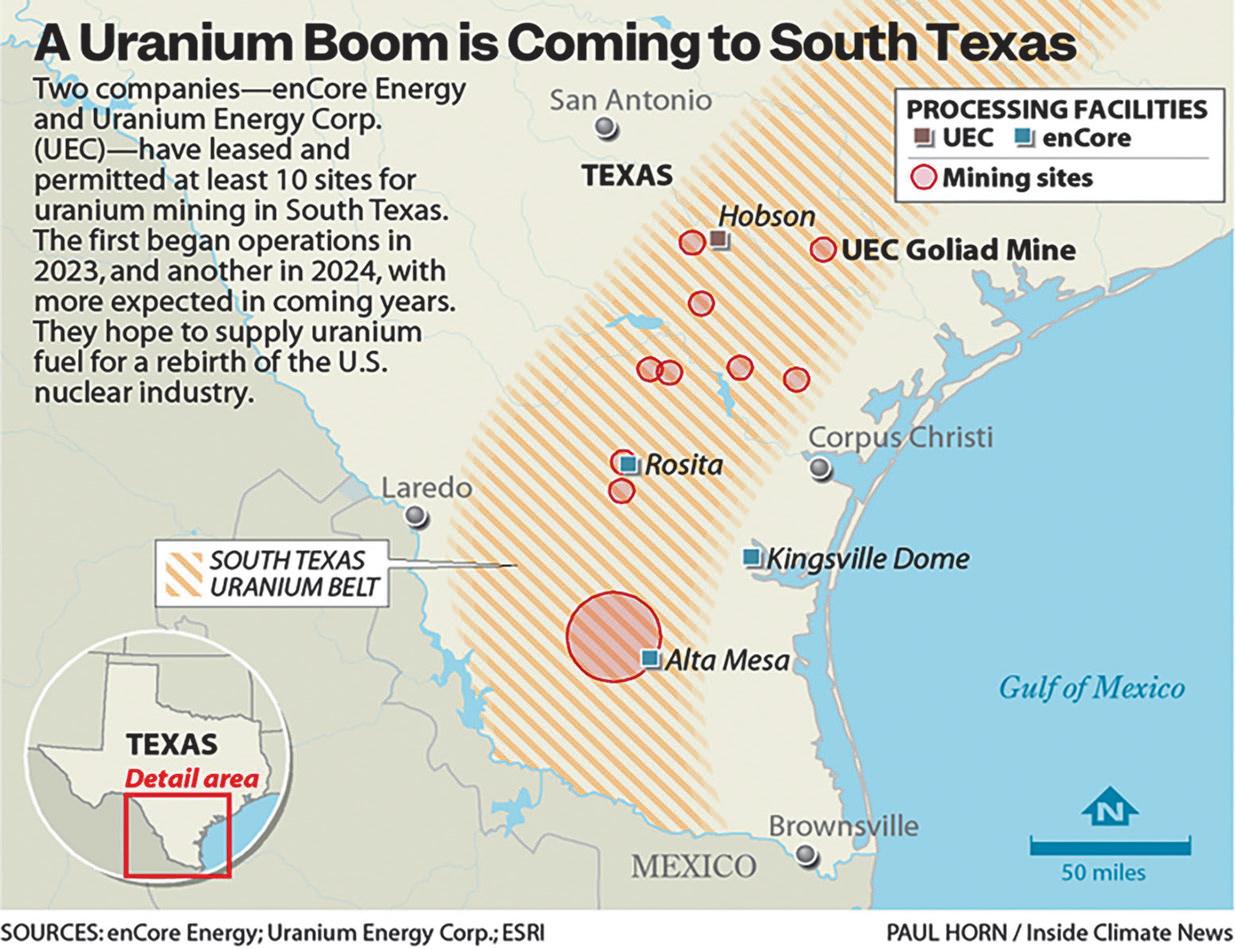

Groundwater district continues attempts to block uranium mining.

By Coy Slavik cslavik@southtexasnews.com

Inthe pastures of Goliad County, where live oaks shade cattle and creeks meander through the landscape, a longtime fight over groundwater is intensifying.

For nearly two decades, the Goliad County Groundwater Con-

servation District (GCGCD) has waged a slow, grinding battle to keep uranium mining company Uranium Energy Corp. (UEC) from injecting chemicals into underground aquifers.

“It’s all about water,” said Wilfred Korth, president of the groundwater district. “It’s about the importance of water, how scarce it’s become, how it’s always been a political issue. And how dire of a situation a lot of counties find themselves in.”

Now, with a new Texas Com-

mission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) filing in hand, the district is bracing for yet another round of hearings and possible court fights.

Two permits, two fronts

The current dispute between the GCGCD and UEC involves two separate permits. The first, a Class I injection well permit, covers the disposal of liquid waste from mining. The second, a Class III injection well permit, authorizes in-situ uranium mining itself – a process that injects an oxygenated solution (called a lixiviant) into uranium-bearing rock, mobilizes the uranium and pumps it to the surface.

The district has already challenged the Class I waste-disposal permit in court after TCEQ granted it over local objections. Now attention has shifted to the Class III mining permit. According to Korth, the district and five nearby landowners have been granted “affected person” status, giving them the right to a contested case hearing before state administrative judges.

UEC’s 1,421-acre project is located about 13.5 miles north of the city of Goliad, near U.S. Highway 183. Although UEC obtained its

original mining permit in 2011, it has not yet begun mining, TCEQ records show.

What the new TCEQ filing reveals

A July 28 document from the TCEQ lays out the latest procedural turn. In the filing, TCEQ Executive Director Kelly Keel recommends that the commission:

• Recognize GCGCD and several nearby families as “affected persons.”

• Deny requests from others judged to be too distant or lacking direct interests.

• Refer eight key disputed issues to the State Office of Administrative Hearings (SOAH) for a six-month contested case hearing.

Those issues include whether UEC’s application provides adequate geological characterization, whether pre-mining groundwater data are sufficient, whether the proposal protects livestock and wildlife, and whether the operation is “in the public interest.”

The executive director’s response also recounts how UEC

THE RIVER | continued on page 25

amended its application in August 2024 to change water-quality parameters by replacing total dissolved solids with alkalinity and adding sulfate and uranium as indicators. These revisions are likely to become focal points in the hearings.

The local district’s objections are not just procedural. Korth said the uranium deposit lies in a fault-ridden section of the Goliad Formation, a series of sand and clay layers that supply water to ranches, homes and small towns.

“Some of those fault lines run through all of our aquifers,” he said. “When they start injecting things into the ground under pressure, are they going to push out that contaminated water into other aquifers that the citizens of Goliad use?”

Hydrologists note that the multiple aquifers in the Ander-Weser area flow toward Victoria County, meaning any contamination could spread beyond Goliad since waterways and aquifers are closely linked.

The TCEQ document confirms that uranium would be mined at depths from roughly 200 feet above sea level to 155 feet below, and that injection could occur only within a production zone designated an “exempted aquifer.”

But Korth disputes that designation.

“We already had people in that aquifer drinking water,” he said.

Uranium, arsenic, and other risks

Health concerns are central to the district’s resistance. The district says uranium and arsenic are the chief contaminants at issue.

“Once it’s contaminated, it’s always contaminated,” Korth said.

TCEQ officials have said the company would be required to clean up any spill, but Korth said no comparable Texas operation has ever restored an aquifer.

“Every situation like this where a company has messed things up, they’ve never got it cleaned up,” he said.

Already, one Goliad County church downstream from the site has drilled a deeper well to avoid arsenic problem, according to Korth, whi said surrounding private wells currently meet standards, but the district cannot test

inside UEC’s lease area.

Layers of law and procedure

The new TCEQ filing underscores how heavily this conflict depends on regulatory law. It details what qualifies as an “affected person,” how hearings are initiated, and which issues can be sent to SOAH.

The commission is poised to refer eight specific issues, including whether operations would protect groundwater and whether monitoring will be adequate. Issues outside TCEQ jurisdiction — such as property takings or total water use — were excluded.

According to Korth, this procedural maze slows public action.

members – all unpaid – have spent hundreds of volunteer hours pursuing the case. Yet public engagement remains thin. A recent meeting drew just 15 residents, most of them over 60.

“It is extremely frustrating,” Korth said. “People think, ‘Well, it’s not in my backyard. I don’t have to worry about it.’ But potentially, it could have a lot of impact.”

The district warns that widespread contamination could force ranchers and homeowners to abandon private wells and pay for costly treatment or hookups. That risk, Korth said, contradicts state leaders’ stated goal of securing future water supplies.

“Everything is so slow,” he said, adding that court dates are rarely prompt and legal fees strain the district’s modest tax base.

Korth said the district’s board

Private property rights complicate the debate. The GCGCD stresses that groundwater knows no fence lines and one owner’s choice could endanger neighbors miles away.

There’s also fear of a domino effect. Another exploration company is reportedly studying uranium deposits in the county.

“If they get willing landowners to lease their land, we could have multiple uranium mines,” Korth said.

With limited resources, Korth said the legal marathon is daunting.

“It all boils down to money, always, in these fights,” Korth said.

The district’s attorney estimates it will cost about $175,000 to contest the mining permit – funds that must come from taxes or donations. Without continued funding, Korth said, the TCEQ could simply issue the permit.

Looking ahead: six-month hearing, then civil court

If the TCEQ follows its executive director’s recommendation, the permit will go to SOAH for a six-month contested case hearing. The commission may also consider mediation, though similar efforts have failed before.

Separately, the district is preparing a civil lawsuit to overturn TCEQ’s earlier approval of UEC’s waste-disposal permit. No trial date has been set. UEC has not yet begun mining, having installed only monitoring wells.

No signs of giving up

In August 2024, the Goliad County Commissioners Court unanimously adopted a resolution opposing uranium mining.

“We’ll all be dead and gone by the time it moves 400 feet to the sample well, but it could be there,” Commissioner Kenneth Edwards said. “Once it’s in there, it’s in there. And I think the best solution is don’t let them do it.”

Despite long odds, Korth says surrender is not an option.

“We’ll keep at it,” he said.

The fight that began in 2006 shows no sign of ending soon.

“It’s just the frustration of knowing you’re doing the right thing, but there’s not any guarantee that any good will come of it,” Korth said.

Yet Korth said he and fellow board members remain determined, volunteering their time “because we’re passionate about protecting the water community.”

UEC did not respond to requests for comment.

Vital to flood control, drought prevention, and wildlife habitat, wetlands face growing threats.

Contributed story by the San Antoni River Authority

Among the most productive ecosystems on Earth, wetlands provide numerous essential functions.

From acting as a buffer for flood and drought to providing habitat to countless species, they have an irreplaceable role in the ecology of the

San Antonio River watershed. Unfortunately, the rapid loss of wetland habitats has had devastating consequences that often go unacknowledged.

What is a wetland?

Wetlands are the transitional areas between deepwater ecosystems – like rivers, bays, estuaries – and dry land. Covered by a shallow layer of water, wetland soil is completely saturated, either permanently or seasonally.

Wetlands, which include marshes, bogs, and swamps, don’t just occur near the coast.

Inland wetlands combine with small streams in the upper parts of our watershed, far from San Antonio Bay, to influence the character and quality of life downstream. This provides the ideal habitat for countless amphibians, insects, shellfish and other semi-aquatic creatures. These critters attract larger predators and migratory birds, increasing the biodiversity of the ecosystems.

Wetlands are an essential, irreplaceable part of our ecosystem, playing a huge role in drought prevention, flood mitigation, and water filtration! Think of a wetland like a sponge –during heavy rain events, they swell, collecting excess runoff.

Wetlands store this water much like a natural reservoir. Wetland water storage is crucial for drought prevention, as the reservoir slowly releases water into the environment, providing life to the ecosystem for a longer period.

Additionally, while the water is being stored, plants filter the stormwater runoff by taking up excess nutrients that would otherwise flow into our creeks and rivers. When wetlands are lost, we also lose a natural buffer to flood, drought, and water pollution.

Wetlands also provide an ideal habitat for an array of animals. They supply a biodiverse, nutrient-rich, protected home for aquatic and semiaquatic animals who are raising their young. This biodiversity attracts migratory birds that depend on wetlands for food and shelter.

For example, critically endangered whooping cranes rely on the wetland habitat of the San Antonio Bay, where the San Antonio River meets the Gulf. After a long migration from Canada, Whooping Cranes depend on the wetland’s fresh water to provide them with food and refuge before their journey back to their nesting grounds up north.

In urban areas, wetlands play an important role in reducing the urban heat island (UHI) effect – a phenomenon where urban areas become warmer because of human activities and lack of vegetation. Urban wetlands can reduce UHIs through evapotranspiration – the combination of evaporation of water from the wetland, and the transpiration of water vapor from plants.

As the water makes its way from the surface of the earth into the atmosphere, the surrounding area cools. Wetlands can also absorb heat, and their plants provide shade, reducing the UHI effect further.

Wetlands have been disappearing rapidly around the world. Factors like urbanization, climate change, and agricultural development have led to the loss of many wetlands in America. With the loss of these wetlands comes an increase in flooding, and less habitat for species that rely on wetlands for food and shelter. However, all hope is not lost! The River Authority works hard to protect our wetlands, and you can too.

Here at the River Authority, we strive to restore, maintain, and protect the San Antonio River Watershed, including many inland wetland habitats at risk of development.

You can help protect local wetlands, too! to aid in the protection of local wetlands through litter cleanups and habitat restoration projects. The San Antonio River watershed takes care of us, so let’s step up and take care of it.

South Texas News area provides variety of world-class angling from

By Coy Slavik cslavik@southtexasnews.com

From rebuilt piers to remote reservoirs, resident and visiting anglers in the South Texas News area have numerous opportunities to enjoy a mix of saltwater serenity and freshwater adventure.

Along the Coastal Bend and even deeper into the Brush Country, fishing isn’t just a pastime – it’s part of the region’s identity. Whether you’re chasing redfish under the moonlight or bass at dawn, here are 10 fishing destinations that define the region’s outdoor spirit.

Fulton Fishing Pier – A revitalized landmark

After being destroyed by Hurricane Harvey, the Fulton Fishing Pier has made a stunning comeback. Located at 402 N. Fulton Beach Road,

the new pier glows with LED lights that illuminate the waters of Aransas Bay for latenight anglers. Open 24 hours a day, it welcomes families, visitors, and serious fishers alike for a $5-per-rod fee.

The pier’s ADA-accessible design, on-site attendant, and snack stand make it both functional and welcoming.

Rebuilt with FEMA assistance and community donations, it stands as a symbol of recovery – and a key piece of Fulton’s coastal economy.

Choke Canyon Reservoir –Where the big ones bite

Located between Three Rivers and Tilden, Choke Canyon is legendary among anglers for its trophy bass. Reports of 10-pound-plus largemouths are common, and the reservoir also supports a robust population of blue and flathead catfish, white bass, and alligator gar.

The Calliham Unit of Choke Canyon State Park provides boat ramps, campgrounds, and access to detailed fishing maps. With special regulations in place to sustain the

ecosystem, it remains one of Texas’ premier freshwater fisheries.

Goose Island State Park Fishing Pier – The coastal classic

Stretching 1,620 feet into the bays of St. Charles and Aransas, the park’s pier gives anglers access to trout, redfish, drum, and flounder. No license is required when fishing from the park’s shoreline or pier.

The Tackle Loaner Program ensures that even first-timers can join in. With a boat and kayak launch, fish-cleaning stations, and campsites nearby, Goose Island blends convenience with natural beauty. The long pier is ideal for quiet sunrise fishing or nighttime casting under the stars.

Rockport Beach Break water Pier – Calm waters, big rewards

Nearby bait shops and gear rentals add to its accessibility. The pier is part of Texas’ first Blue Wave-certified beach, recognized for its cleanliness and environmental stewardship – an ideal place to fish and relax.

Coleto Creek Reservoir –Freshwater escape in Goliad County

Managed by the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority, Coleto Creek’s 200-foot lighted pier draws freshwater anglers after dusk. The reservoir offers opportunities for largemouth bass, catfish, crappie, and sunfish, while the park’s amenities — boat ramps, campsites, cabins, and picnic areas — make it a favorite for weekend trips.

An entrance fee is required, but the peaceful setting southwest of Victoria rewards visitors with quiet mornings, wildlife sightings, and plenty of fish.

Indian Point Pier –Portland’s coastal gem

A gem in the heart of Rockport Beach, the Breakwater Pier is prized for its calm waters and abundant species. Common catches include flounder, sheepshead, and trout, while benches and shaded seating make it a comfortable stop for families.

The Indian Point Pavilion and Pier in Portland has been completely revitalized. Visitors now enjoy a shaded pavilion, green fishing lights, upgraded railings, and enhanced accessibility features.

The park is open 24/7 year-round with no admission fee, making it one of the most popular community fishing spots in the Coastal Bend. With nearby food truck spaces and scenic waterfront views, Indian Point has become a social hub for anglers and families alike.

Conn Brown HarborPoint Park – Working harbor turned angler haven

Conn Brown Harbor Point Park is located in Aransas Pass, Texas, near the Intracoastal Waterway. It offers amenities for fishing, like a pier and fish cleaning tables, as well as picnic shelters and restrooms.

Lake Corpus Christi — A reservoir rich in opportunity

Covering 18,256 acres and spanning three counties, Lake Corpus Christi near Mathis is known for its diverse fishery and scenic shoreline. Anglers can expect bass, crappie, and catfish in abundance, particularly during the spring and fall.

The lake’s fluctuating levels and varied vegetation create perfect habitats for sportfish. Managed by the City of Corpus Christi, the lake includes boat ramps, campgrounds, and marinas — making it a full-service destination for families and serious anglers alike.

Cove Park, Ingleside – A family-friendly waterfront

Set along 1319 Ocean Drive, Cove Park offers both relaxation and recreation. Two lighted boat ramps, a small fishing pier, and picnic areas with grills make it a convenient choice for locals.

The park also includes a short hikeand-bike trail, playground, and large open field for sports. Overlooking Corpus Christi Bay, it’s a scenic spot to end the day – especially when the sun sets over the water.

Copano Bay State Fishing Pier – History on the water

The remnants of the old Copano Causeway are no longer accessible, thanks to Hurricane Harvey. But the fishing at the boat ramp and underneath the causeway still provides a chance at reeling in large redfish, black drum, and speckled trout.

Coastal Bend Distilling Co., a hidden gem nestled in the heart of Texas, is making waves in the world of craft spirits with their exceptional range of products. Recently, the distillery garnered well-deserved recognition and accolades for their gin and vodka, solidifying its position as a rising star in the industry.

Coastal Bend Distilling Co., founded by Kenneth and Eveline Bethune, has been quietly perfecting their craft over the years, and their hard work has not gone unnoticed. Despite being a relatively small operation, they have managed to stand out from the crowd and impress seasoned judges and connoisseurs alike.

Coastal Bend Distilling Co. seized 2024 Best Distillery in Best in Bee and the Local’s List for the Coastal Bend. Their commitment to using only the finest ingredients and traditional vapor infused distillation methods set them apart from the competition. Coastal Bend Distilling Co.’s Lucky Star Gin has previously brought home other awards, including a silver taste award at the 2020 John Barleycorn contest, a bronze medal in 2021 from the American Craft Spirits Association, and a tasting score of 90 from the 2020 Ultimate Spirits Challenge. The distillery’s owner & managing proprietor, Kenneth Bethune, credits the gin’s success to its unique flavor profile that emphasizes citrus peel botanicals and scales back on the often polarizing juniper berry.

The distillery’s foremost spirit, Live Oak Vodka, has also brought home numerous awards. Most recently, Live Oak Vodka received a score of 91, or “Highly Recommended” from the Ultimate Spirits Challenge. Judges described the vodka as “remarkably clean, with soft expressions of wet stone and rainwater. Light whispers of Douglas Fir and American Oak are distinct, enjoyable, and very subtle.” The vodka’s previous awards also include a 2020 silver medal for taste at the John Barleycorn Awards and a double gold that same year for unique label design.

Bethune and Coastal Bend Distilling Co.’s head distiller, Craig Olson, expressed gratitude for the awards. “We are humbled and thrilled to receive such recognition for our craft.” Said Olson, “It’s a testament to the hard work of our team and our passion for producing exceptional spirits that embody the true essence of Texas.”

The awards have also sparked increased interest in Coastal Bend Distilling Co.’s tasting room, where visitors can experience their award-winning spirits first-hand. With the charming ambiance of Beeville and the warmth of Texan hospitality, it’s no wonder enthusiasts and tourists are flocking to sample the distillery’s offerings. Open on a limited basis, the tasting room serves craft cocktails featuring the distillery’s array of spirits: Live Oak Vodka, Lucky Star Gin, Colonel Fannin’s Whiskey, and La Lechuza Agave Spirit.

Coastal Bend Distilling Co. continues to create a buzz in the spirits community, and their future appears to be as bright as the Texas sun. As word spreads about their exceptional products and commitment to quality, it’s likely that this once-hidden gem will become a shining star in the world of craft distilling.

The distillery’s spirits can now be found across Texas with a significant presence in the Coastal Bend, as well as in the San Antonio and Austin metroplex areas. New distribution growth has been established in Houston and Dallas markets, and the distillery’s General Manager, Robert J. Nollen, II, says that distribution has more than doubled in 2023.

For those eager to savor the flavors that have captured the hearts of judges and locals alike, a visit to Coastal Bend Distilling Co. in Beeville, Texas, promises an unforgettable experience. For those unable to visit the tasting room, the distillery’s website offers an interactive map where you can search products available at bars, restaurants, liquor stores and more nearby.

PROUDLY PROUDLY DISTILLEDHERE DISTILLEDHERE INBEEVILLE, INBEEVILLE, SOUTHTEXAS SOUTHTEXAS