The 31 day Twitter educational event compilation

Brought to you by @dastrainees, @Vapourologist and #DASeducation

Editors

Helen Aoife Iliff

Tom Lawson

Contributors

Tom Lawson Helen Aoife Iliff Imran Ahmad Alistair Baxter

Tim Cook Adam Donne Kariem El-Boghdadly Luke Flower

Alice Humphreys Kamila Kamaruddin Sadie Khwaja Fiona Kelly

Nuala Lucas Moon-Moon Majumdar Cameron Maxwell Brendan McGrath

Barry McGuire Andrew McKechnie Alistair McNarry Sarah Muldoon

Anil Patel Elizabeth Ross Natalie Silvey

The large majority of graphics and illustrations are by Tom Lawson or Helen Aoife Iliff. Some have been adjusted from the original Twitter content in an effort to prevent any potential copyright infringements in this compilation. Original images sources can be found in the further reading. We thank all image contributors. Some images have been reproduced in good faith, for educational purposes only. Where possible permissions have been sought. If any copyright holders have any issues please contact us at trainee@das.uk.com and the content will be withdrawn.

We thank and acknowledge all those who contributed to the #JanuAIRWAY content, both for the original twitter event and this compilation.

We thank the Difficult Airway Society (DAS), Society for Obesity and Bariatric Anaesthesia (SOBA) and British Association of Otorhinolaryngology (ENT-UK) for their direct or member support and engagement in this work.

We thank Imran Ahmad, Alistair Baxter, Ravi Bhagrath, Abhijoy Chakladar, Tim Cook, Adam Donne, Gunjeet Dua, Kariem El-Boghdadly, Luke Flower, Alice Humphreys, Craig Johnstone, Kamila Kamaruddin, Sadie Khwaja, Fiona Kelly, Nuala Lucas, MoonMoon Majumdar, Cameron Maxwell, Brendan McGrath, Barry McGuire, Andrew McKechnie, Alistair McNarry, Fauzia Mir, Sarah Muldoon, Achuthan Sajayan, Ellen O’Sullivan, Anil Patel, James Peyton, Elizabeth Ross, Natalie Silvey and Sarah Tian for their review of the content.

We offer particular thanks to Jeff Gadsden for the inspiration.

This is the compilation of tweetorial content from #JanuAIRWAY. Every effort has been made to ensure the content is factually correct and up to date. It is not intended to replace other existing educational materials. If you identify any errors please notify us at trainee@das.uk.com

This is intended to be a learning resource - it is not a guideline. For all DAS Guidelines please refer to the peer reviewed publications.

Inclusion of content (equipment, techniques and scoring systems etc.) in #JanuAIRWAY does not constitute DAS endorsement.

Some images have been reproduced in good faith, for educational purposes only. Where possible permissions have been sought. If any copyright holders have any issues please contact us at trainee@das.uk.com and the content will be withdrawn.

The DAS Education team are passionate about delivering good quality learning resources. Our Educations Co-leads work closely with our Trainee Reps to put together material and events we hope our members will benefit from.

Details on how to become a DAS member are available here

| on behalf of the Difficult Airway Society |

DAS is mostly known for its airway management guidelines, Annual Scientific Meetings and airway courses. However, this year we decided to try something new, something that is beyond the traditional scope of DAS. The brain child of one of our Education leads with help from the current DAS Trainees DAS took on #JanuAIRWAY - a month of daily educational tweets covering all matters airway! An immense amount of work has been involved in putting this educational material together and we feel it has been a huge success. Many congratulations to the team involved, in particular Tom Lawson and Helen Iliff, who have given a huge amount of time to the preparation and delivery of this project! The overwhelmingly positive response, excellent feedback and huge twitter engagement has encouraged us to put together this compilation. We hope you enjoy the content and will share this free and valuable educational resource.

- Imran Ahmad, DAS President

All the best ideas are stolen. #JanuAIRWAY was no different. Dr Jeff Gadsden’s #Blocktober, 31 days of regional anaesthesia content; each day highlighting a different block, provided the inspiration. A programme of airway-related teaching materials (with a suitable month pun name) was created covering a broad range of airway management topics, that could appeal to the widest audience, from the novice to the experienced. With the help of an amazing team (thanks to our contributors, but special thanks to the DAS trainee representatives; Natalie Silvey, Moon-Moon Majumdar and especially, Helen Iliff), over the last year, the project has evolved from those amateurish beginnings into something far greater than I could’ve hoped for alone. I hope that #JanuAIRWAY and this compilation will become an evolving airway training resource that is used by practitioners across the globe for many years to come.

- Tom Lawson, DAS Education Co-lead & Creator of #JanuAIRWAY

Natalie, Moon-moon and I have thoroughly enjoyed working with Tom to bring you #JanuAIRWAY 2022. We hope those on twitter have enjoyed not just the content, but also engaging with DAS in a less traditional form. For those not on twitter I hope you find the compilation an interesting read and useful educational resource - and perhaps it may convince you to join us in the twittersphere @dastrainees for #JanuAIRWAY in 2023!

-Helen Aoife Iliff, Trainee Rep

If anyone has any feedback please feel free to contact us at either trainee@das.uk.com or ezine@das.uk.com

2022 Edition - Day and Theme

1st Oxygen Physiology

2nd Airway Assessment

3rd Defining the Difficult Airway

4th Airway Investigation, Lung Function Tests and Airway Ultrasound

5th Airway Strategy/Planning

6th Basic Airway Equipment

7th Airway Laryngoscopy

8th Capnography & Oesophageal Intubation

9th High Flow Nasal Oxygen (HFNO)

10th Cook Airway Exchange Catheter

11th Aintree Intubation Catheter

12th Awake Tracheal Intubation (ATI)

13th Jet Ventilation

14th One Lung Ventilation

15th Tracheostomies and Laryngectomies

16th eFONA: Cannula Techniques

17th eFONA: Scalpel Techniques

18th Extra eFONA equipment

19th The Obstructed Airway: Nasal / Oral

20th The Obstructed Airway: Larynx / Laryngopharyngeal

21st The Obstructed Airway: Larynx / Extrathoracic Trachea

22nd The Obstructed Airway: Intrathoracic

23rd Malacias; Bleeding & SVC Obstruction

Day and Theme

24th The Paediatric Airway

25th The Obstetric Airway

26th The Traumatic Airway

27th The Neurosurgical Airway

28th The Bariatric Airway

29th Extubation & Cook Staged Extubation Set

30th Guidelines, Guidelines, Guidelines

31st Difficult Airway Conditions

2024 Edition (New content)

1st Transgender Airway

3rd Gastric Ultrasound

5th Pulmonary Aspiration

9th Face Mask Ventilation

11th Retrograde Intubation

16th Dental Trauma

18th Laryngospasm

22nd ECMO and Difficult Airways

23rd The Bleeding Airway

25th Submental Intubation

26th VL-Assisted Tracheal Tube Exchange

30th Human Factors in Airway Management

Further Reading

“Here’s the rule: no one’s expected to have all the answers. If you are asked a question, and do not know the answer, just say, “I don’t know, but I’ll find out.” And when you do, never fail to pass along the correct information. You can never tell who the elephant in the room may be –because elephants just don’t forget.”

- Marty Sklar, Imagineer| Always. Be. Oxygenating! |

The meaningful delivery of adequate oxygen is the fundamental aim of all airway management. Think A.B.O. – Always. Be. Oxygenating. Knowledge of the three basic equations for oxygen physiology is essential:

1. Arterial Oxygen Content

2. Oxygen Delivery

3. Oxygen Consumption

They can steer us towards various physiological parameters that we can manipulate to treat (failure of tissue oxygenation)/hypoxaemia (a low concentration of oxygen in arterial blood).

The oxygen cascade shows levels and processes involved and differentials for hypoxaemic hypoxia:

1. Decreased inspired partial pressure of oxygen (e.g. altitude or low FiO2)

2. Alveolar gas mixture - dilution with CO2 (hypoventilation – for example excess opiate)

3. Diffusion (e.g. pulmonary fibrosis)

4. Shunt, V/Q mismatch (e.g. pneumonia, pulmonary oedema)

5. Increased O2 demand/use (e.g. sepsis, malignant hyperthermia)

Other causes of hypoxia include anaemic hypoxia (e.g. anaemia, carbon monoxide poisoning), stagnant or ischaemic hypoxia (e.g. cardiogenic shock), and rarely – histotoxic hypoxia (e.g. cyanide toxicity).

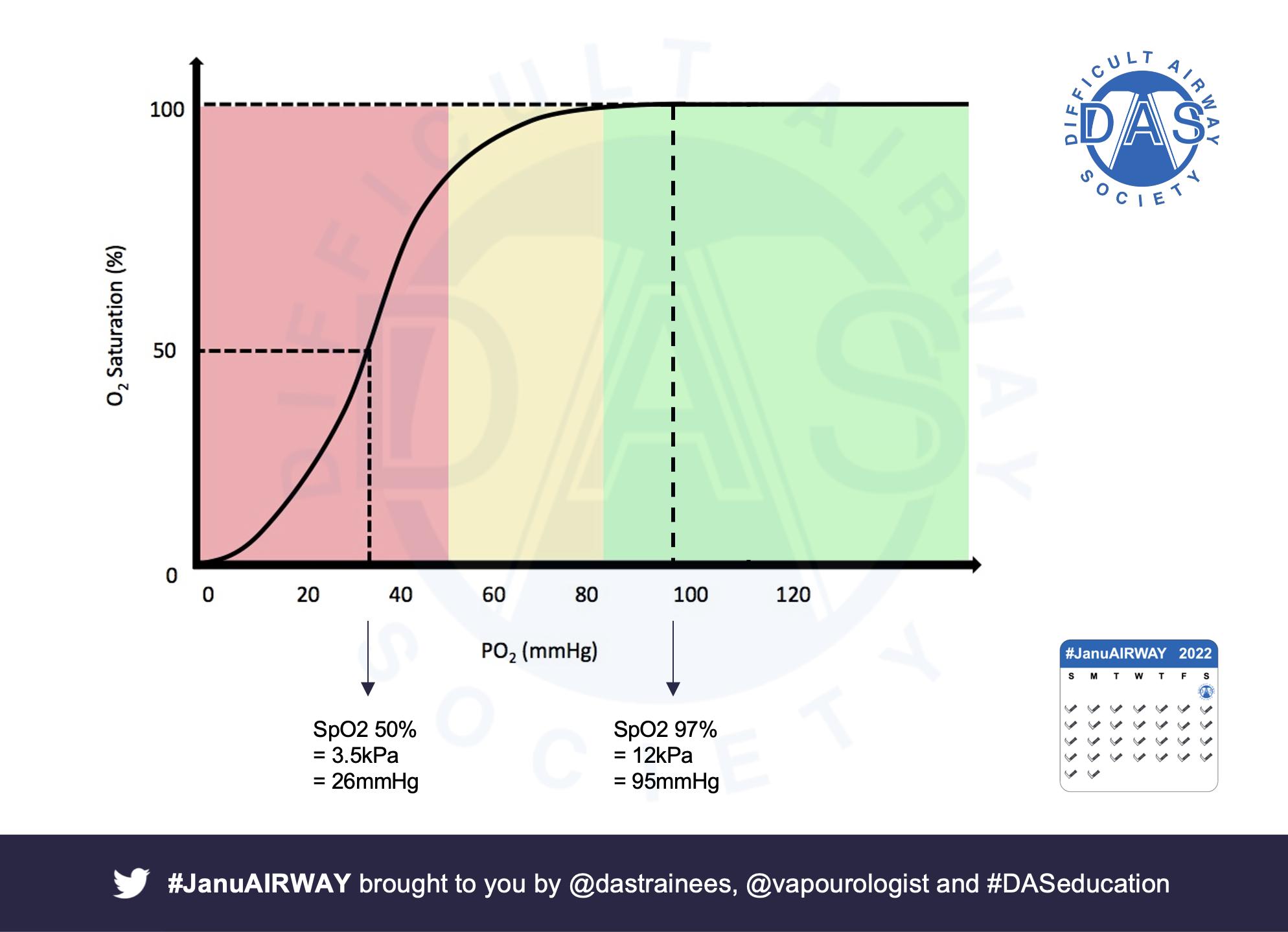

The Oxy-Hb curve shows why the focus in desaturation must be getting oxygen in. When the SpO2 starts to fall, it’s slow initially but then precipitous. The benefit is, often a little oxygen going back in, in general means a rapid rise back to safety.

Pre/apnoeic oxygenation are key weapons, but must be done well. Patience, vital capacity breaths +/- high flow nasal oxygen are key. They are of particular importance in patients with obesity, who may have a smaller functional residual capacity and be more difficult to facemask ventilate.

Here are some articles that might be of interest:

a. Patel A, Nouraei SA. Transnasal Humidified Rapid-Insufflation Ventilatory Exchange (THRIVE): a physiological method of increasing apnoea time in patients with difficult airways. Anaesthesia. 2015; 70: 323-9

b. McNamara MJ, Hardman JG. Hypoxaemia during open-airway apnoea: a computational modelling analysis. Anaesthesia. 2005; 60: 741-6

c. Levitan R. NO DESAT! Emergency Physicians Monthly. 2010 (online)

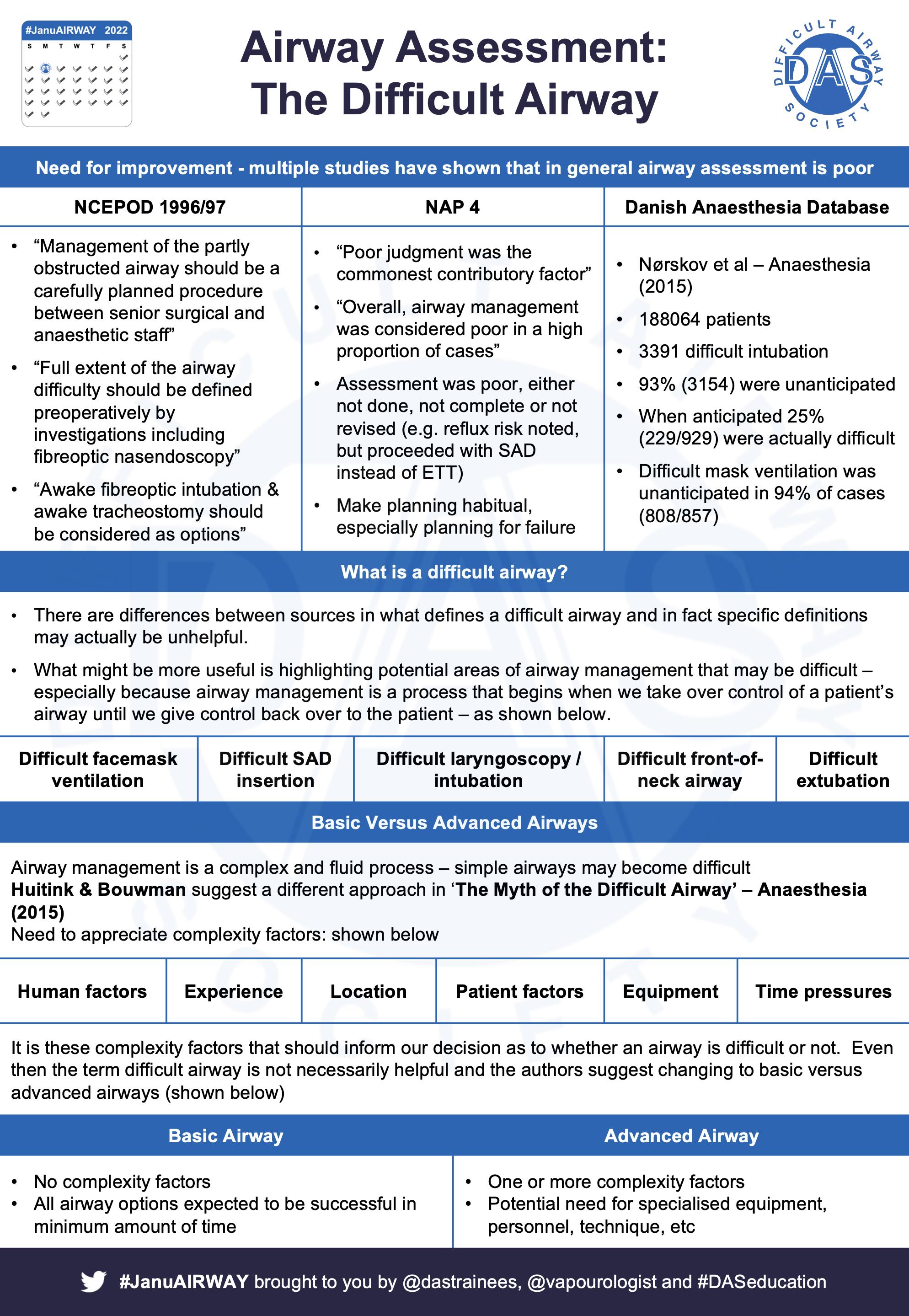

NAP4 showed poor airway assessment contributes to poor outcomes. Thorough assessment is essential. There are a number of bedside tests available to help assess for potential difficult airway management

Airway Assessment should be holistic & comprised of three basic parts:

1. History - including review of previous management (if possible)

2. Examination - visual examination and bedside tests

3. Investigations

NAP4 gives us a structure to focus our examination on anatomical/procedural difficulty:

1. Difficult bag mask ventilation

2. Difficult Supraglottic Airway Device (SAD) insertion

3. Difficult laryngoscopy

4. Difficult tracheal intubation

5. Difficult Front of Neck Airway (FONA)

6. Difficult tracheal extubation

The problem is that individually, none of these are perfect, with widely variable sensitivity & specificity; possibly improved when combined. But many unanticipated difficult airways are still missed - see this 2018 Cochrane review.

A thought-provoking finding of Norskov et al's Danish Airway Database cohort study was that difficult mask ventilation was unanticipated in 94% of cases (808/857). This is why airway assessment needs to be holistic.

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Langeron O, Masso E, Huraux C, Guggiari M, Bianchi A, Coriat P, Riou B. Prediction of difficult mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2000; 92:1229-36

b. Kheterpal S, Martin L, Shanks AM, Tremper KK. Prediction and outcomes of impossible mask ventilation: a review of 50,000 anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2009; 110: 891-7

c. Reed MJ, Dunn MJ, McKeown DW. Can an airway assessment score predict difficulty at intubation in the emergency department? Emergency Medicine Journal. 2005; 22: 99-102

d. Detsky ME, Jivraj N, Adhikari NK, et al. Will This Patient Be Difficult to Intubate? The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA. 2019; 321: 493–503

| It’s complicated |

The term “Difficult Airway” has definitions. NAP4 has a procedural framework - useful but not the whole picture. Hans Huitink and Bouwan’s introduce “complexity factors” in their 2015 editorial on “The myth of the difficult airway:airway management revisited”

Complexity factors make easy things difficult e.g. operator experience, location, time pressures. They have to be considered. Huitink also suggests ditching the term ‘difficult’ in favour of ‘basic and advanced’.

Our airway assessment aims to determine difficulty of management. We want to use our holistic assessment (history, examination and investigations) to answer several questions.

As well as consideration of complexity factors we also need situational awareness. We like to imagine concentrating ‘thinking zones’ emanating from the patient.

1. Patient (anatomy, physiology)

2. Airway manager (experience, fatigue, stress)

3. Team (experience, number)

4. Environment (time, familiarity, safety)

When we want to integrate our assessment info and situational awareness, the Cynefin framework (by Dave Snowden) and the Johari window can help our mental model for decision-making in ‘difficult airways’.

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. The Royal College of Anaesthetists and The Difficult Airway Society. 4th National Audit Project: Major complications of airway management in the United Kingdom. 2011 (online)

b. Grey AJG, Hoile RW, Ingram GS, Sherry KM. The Report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths 1996/1997. 1998 (online)

c. Nørskov AK, Rosenstock CV, Wetterslev J, Astrup G, Afshari A, Lundstrøm LH. Diagnostic accuracy of anaesthesiologists' prediction of difficult airway management in daily clinical practice: a cohort study of 188 064 patients registered in the Danish Anaesthesia Database. Anaesthesia. 2015; 70: 272-81

| Physiology and physics in action |

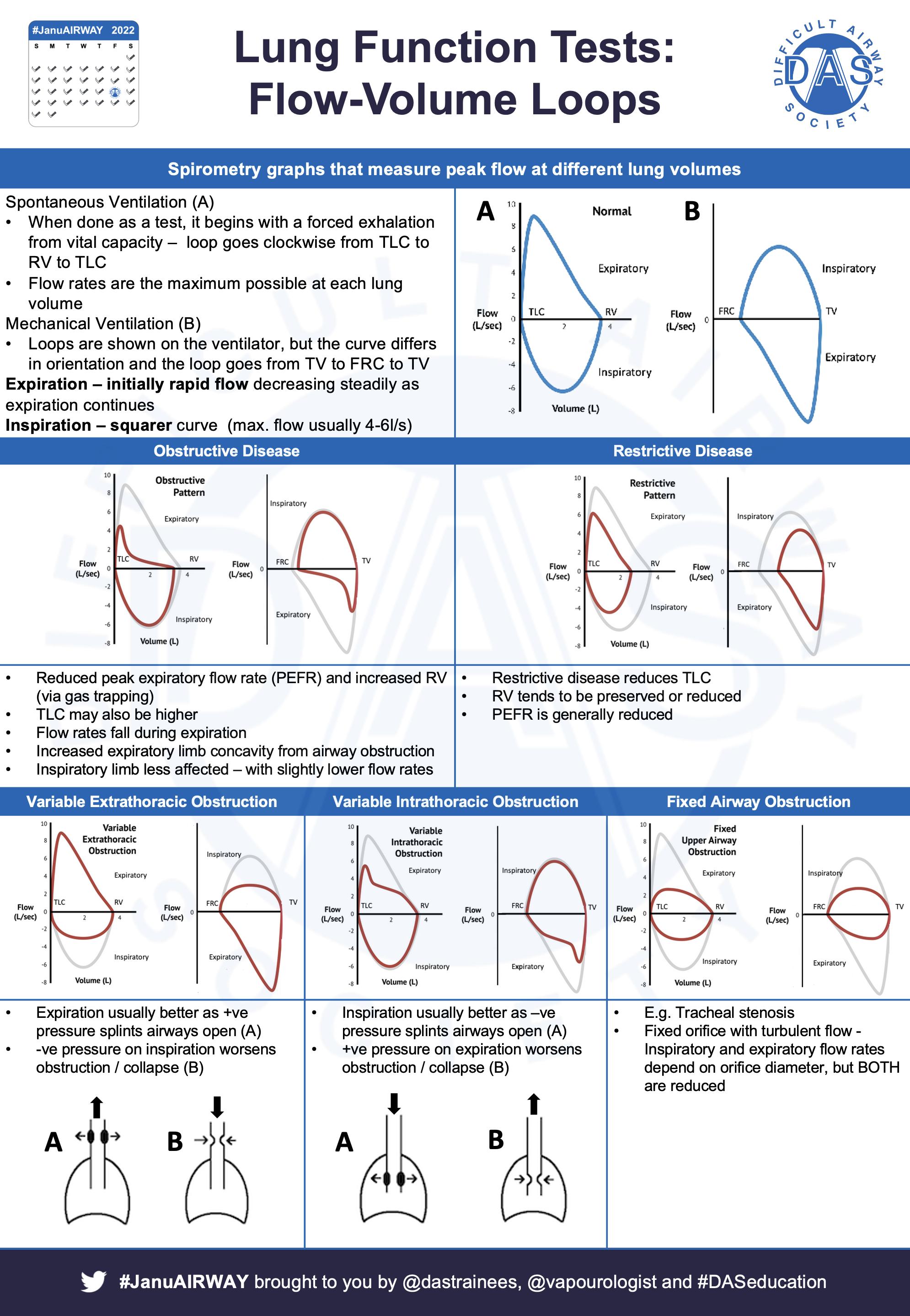

2 broad categories we can use to round out our airway assessment; flow/volume-based lung function tests & imaging techniques. They vary in their usage and usefulness.

Spirometry (literally ‘measuring breath’) and flow-volume loops give us information on the mechanics of ventilation. They can be helpful in a more global assessment of respiratory function, but are less helpful in acute airway management.

Diffusing Capacity / Transfer factor can augment lung function tests and give us info about alveolar diffusion and alveolar thickness. Again, helpful in global assessment, but less helpful acutely.

Imaging techniques – these can be incredibly useful in peri-operative management. Two main types: radiological (CT, MRI and/or USS) and endoscopic techniques. The key information you want is:

1. Is an airway abnormality present?

2. If so what kind – usually compression / stenosis

a. Lesion location and extent?

b. Maximal airway diameter?

c. Airway displacement?

d. Other structures involved / in the way (e.g. blood vessels)?

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Crawley SM and Dalton AJ. Predicting the difficult airway, British Journal of Anaesthesia Education, 2015; 15: 253–7

b. Ahmad I, Millhoff B, John M, Andi K, Oakley R. Virtual endoscopy--a new assessment tool in difficult airway management. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2015; 27: 508-13

c. Zhou Z, Zhao X, Zhang C, Yao W. Preoperative four-dimensional computed tomography imaging and simulation of a fibreoptic route for awake intubation in a patient with an epiglottic mass. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2020;125: e290-2

What about Airway Ultrasound? It’s a useful, yet simple, skill to support safe airway management. Check out Michael Seltz Kristensen's work – undisputed master of airway ultrasound.

Indications?

Scan to locate:

• Cricoid cartilage for cricoid pressure

• Cricothyroid membrane if at risk of cricothyroidotomy

• Tracheal rings for tracheostomy

• Superior laryngeal nerve for regional anaesthesia

(For point-of-care gastric USS check out this summary by El-Boghdadly, Wojcikiewicz and Perlas - here.)

Here we focus on the transverse views for cricothyroidotomy. Start by getting the patient in the position, in which you would perform a tracheostomy – consider a bag of fluid under the shoulders.

Linear probe / transverse orientation. Start with the probe on the neck under the chin. Scan caudally until you see the thyroid cartilage – triangular or inverted V-appearance between strap muscles (angle of the thyroid cartilage is more acute in males).

Scan caudally looking for the air-mucosa interface - a bright hyperechoic white line - represents the beginning of the tracheal lumen below the cricothyroid membrane– hence a target for cricothyroidotomy (reverberation artefact is below in tracheal lumen beneath).

You can mark the position of the cricothyroid membrane at this level with a pen on either side of the probe (left and right, top and bottom).

Continuing caudally the cricoid cartilage comes into view as a hypoechoic inverted U or horseshoe shape with the Air-Mucosa Interface below.

The tracheal rings will come into view as hypoechoic ring-like shapes with air-muscosa interface below and thyroid gland above and to either side – useful to know its location and vascularity before percutaneous tracheostomy.

Longitudinal/parasagittal views along trachea, air-mucosa interface = long white line, cartilages appear as hypoechoic ovals – sometimes called a ‘string of pearls’ – they look a bit like coffee beans! You can use any needle or cannula in a transverse orientation to identify the level.

Here are some papers/links that you might find interesting:

a. Kristensen MS, Teoh WH, Rudolph SS. Ultrasonographic identification of the cricothyroid membrane: best evidence, techniques, and clinical impact. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2016; 117: i39-i48

b. Elliott DS, Baker PA, Scott MR, Birch CW, Thompson JM. Accuracy of surface landmark identification for cannula cricothyroidotomy. Anaesthesia. 2010; 65: 889-94

c. Dinsmore J, Heard AM, Green RJ. The use of ultrasound to guide time-critical cannula tracheotomy when anterior neck airway anatomy is unidentifiable. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2011; 28: 506-10

d. El-Boghdadly K, Wojcikiewicz T, Perlas A. Perioperative point-of-care gastric ultrasound. British Journal of Anaesthesia Education. 2019; 19: 219-26

e. Identification of the cricothyroid membrane with ultrasonography Longitudinal "string of pearls" approach - video (online)

| Strategies are essential (NOT just plans) |

Decision making, an important non-technical skill, is a key aspect of safeairway management, and something that is often not well in training curricula. NAP4 showed that poor judgement was implicated in many airway complications. This is an issue because we encounter difficult airways relatively infrequently, and complications are rarer still. We know that low exposure leads to higher anxiety. Add in multiple options Huitink & Bouwman suggest more than 1,000,000 combinations of options to oxygenate and things can get complicated. More options can mean more anxiety; in an emergency, more options are not always useful.

Cognitive load can lead to decision fatigue & increasing bias & poorer decisions. Chew et al came up with the TWED checklist which can help:

T Threat – define problem

W Wrong? What if I’m wrong? What else could it be?

E Evidence to confirm / exclude

D Dispositional factors – environment, hunger, fatigue

The Elaine Bromiley & Gordon Ewing cases are essential reading for people that manage airways. Both highlight competing problems with task fixation and failure to accept safe (but not necessarily desirably situations). Here are the key issues & a decision cycle as a way of combating both.

Situational awareness is key. Notices whats going on around you, take time to Understand it, Think Ahead (NUTA). @Vapourologist (Tom Lawson) uses this four step approach (below left) with ADEPT mnemonic.

You’re not alone in having airway skills – remember our surgical colleagues. Involve them early. BUT remember not all surgeons are equal (same as anaesthetists!) – we all have subspecialty interests – a rhinologist might not be comfortable performing an eFONA either!

Putting it all together – consider an airway strategy sheet to define problems / limits up front, involve ENT early, define plans A, B, C & D – consider all options, but decide on a few.

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. The Royal College of Anaesthetists and The Difficult Airway Society. 4th National Audit Project: Major complications of airway management in the United Kingdom. 2011 (online)

b. Chrimes N, Fritz P. The Vortex Approach to airway management (online)

Knowledge of what drugs we can use and how we use them in airway management is indispensable – especially where planning is concerned. Drugs affect the airway in one of three ways:

a. Direct action e.g. local anaesthetics or bronchodilators

b. Indirect action e.g. volatile anaesthetics or respiratory stimulants

c. Adverse reaction e.g. as a result of anaphylaxis

The three main effects drugs have on the airway are be changing:

a. Airway patency – usually by reducing muscle tone

b. Airway reactivity – airways can be irritated either by central or local effects

c. Aspiration protection – may be reduced (e.g. drugs that reduce conscious level) or improved (e.g. PPI)

Drug controversies in difficult airways:

• To paralyse or not

• Spontaneous Ventilation or IPPV during induction of anaesthesia

Key points:

- Paralysis can be reversible – have a plan

- Maintaining spontaneous ventilation can be inconsistent

2 simple rules for drugs:

1. Use drugs that are easily titratable & reversible

2. Plan for failure

Some people use a ‘wake up tray’ with NRDS drugs drawn up and ready to go

N – Naloxone

R – Reversal (Glyc/Neostig)

D – Doxapram

S – Sugammadex (if applicable)

2 main drugs:

1. Sedatives

2. Local anaesthetics

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=epGFFQcwjBA

Key is that local anaesthetic needs to be in the right place. If it is you don’t need much. This is @vapourologist after gargling 10ml instilagel with 10ml water for 2 mins.

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Consilvio C, Kuschner WG, Lighthall GK. The pharmacology of airway management in critical care. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 2012; 27: 298-305

b. Royal Free Anaesthesia. How to topicalise the airway for awake fiberoptic intubation (AFOI) - video (online)

c. Johnston KD, Rai MR. Conscious sedation for awake fibreoptic intubation: a review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2013; 60: 584-99

| Good workers know their tools |

Good workers know their tools – knowing our equipment is essential! See the #OnePagers for the fundamentals of masks, NP/OPs, SADs, ETTs and Frova intubating introducer.

Specific airway devices such as Cook airway exchange catheters, Aintree Intubation Catheters, Staged Extubation Kits, OLV equipment, Tracheostomies, are covered later in the compilation.

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Laurie A, Macdonand J. Equipment for airway management. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine. 2018; 19: 389-96

b. Bjurström MF, Bodelsson M, Sturesson LW. The Difficult Airway Trolley: A Narrative Review and Practical Guide. Anesthesiology Research and Practice. 2019

c. Chishti K. Setting up a Difficult Airway Trolley. 2015 (online)

d. Gibbins M, Kelly FE, Cook TM. Airway management equipment and practice: time to optimise institutional, team, and personal preparedness. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2020; 125: 221-4

| DL, VL or Combined FB:VL? |

Laryngoscopy, as a prelude to tracheal intubation, is an essential skill for airway managers. There is a wide array of laryngoscope types and approaches used to achieve this view of the glottis.

Broadly speaking, laryngoscopy can be direct (DL) or indirect (VL) and can involve a rigid or a flexible device. All devices and approaches require specific skills and may require additional intubation aids, such as a stylet. The term ‘videolaryngoscopy’ has now been adopted for all rigid laryngoscopes that deliver an indirect view of the glottis. Innovators will develop new techniques, such as combining videolaryngoscopy and flexible bronchoscopy, to overcome difficulty.

It is important to understand the Cormack and Lehane classification, universally adopted for grading of direct laryngoscopy view. This becomes less relevant with indirect laryngoscopy, where there is no agreed classification system. The Video Classification of Intubation (VCI) score is a potential model (*inclusion in this material does not constitute DAS endorsement).

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Jackson, C. The technique of insertion of intratracheal insufflation tubes. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1913; 17: 507-9

b. Knill RL. Difficult laryngoscopy made easy with a "BURP". Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia 1993; 40: 279-82

c. Chaggar RS, Shah SN, Berry M, Saini R, Soni S, Vaughan D. The Video Classification of Intubation (VCI) score: a new description tool for tracheal intubation using videolaryngoscopy: A pilot study. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2021; 38: 324-6

d. Lewis SR, Butler AR, Parker J, Cook TM, Schofield-Robinson OJ, Smith AF. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for adult patients requiring tracheal intubation: a Cochrane Systematic Review. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017; 119: 369-83

| with thanks to Tim Cook and Barry McGuire for their expert contributions |

This is one of the most essential pieces of monitoring equipment needed during airway management. But its presence isn’t enough, correct interpretation is vital. Capnography is primarily an AIRWAY monitor.

Oesophageal intubation still occurs & EtCO2 is a key tool to help prevent avoidable deaths such as Glenda Logsdail’s. Key message is that flat or no trace indicates oesophageal intubation until proven otherwise.

This thread by Professor Tim Cook is fantastic and we recommend everyone read it! He also has an article in FICM’s Critical Eye

The Royal College of Anaesthetists and DAS video “Capnography: No Trace = Wrong Place” is essential viewing for all airway managers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t97G65bignQ&t=8s

The RCoA have a number of other videos available on their website on a page dedicated to the prevention of future deaths

We also recommend all airway managers read this DAS ezine article by Barry McGuire Imran Ahmad, Alistair McNarry, Abhijoy Chakladar and Lewys Richmond.

Another reported case in Australia has further emphasised this is not just a UK problem, it is a global issue. But as Professors Ellen O’Sullivan and Tim Cook have pointed out there is an almost 100% “Capnography Gap” in LIC (audits completed in Malawi & Uganda) which must be addressed

See this recent series from Anaesthesia Journal on unrecognised oesophageal intubation

• Editorial

• Broadcast

• Podcast

Here are some other papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Cook, T.M., Kelly, F.E. and Goswami, A. ‘Hats and caps’ capnography training on intensive care. Anaesthesia, 2013; 68: 421

b. Joy P, Kelly FE. Unrecognised Oesophageal Intubation. Anaesthesia News. 2022 (online)

c. Cook TM, Harrop-Griffiths W. Capnography prevents avoidable deaths. British Medical Journal. 2019; 364: l439

d. CORONERS COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES Inquest into the death of Emiliana Obusan. 2021 (online)

e. MILTON KEYNES CORONER’S COURT Inquest into the death of Glenda May Logsdail REGULATION 28: REPORT TO PREVENT FUTURE DEATHS

f. Foy KE, Mew E, Cook TM, Bower J, Knight P, Dean S, Herneman K, Marden B, Kelly FE. Paediatric intensive care and neonatal intensive care airway management in the United Kingdom: the PIC-NIC survey. Anaesthesia. 2018; 73:1337-44

g. Collins J, Ní Eochagáin A, O'Sullivan EP. A recurring case of 'no trace, right place' during emergency tracheal intubations in the critical care setting. Anaesthesia. 2021; 76 :1671

| with thanks to Anil Patel for his expert contributions |

This has been a game-changer in recent years. Thank you Professor Anil Patel and S Nouraei for your amazing landmark paper on THRIVEl!

Oxygen consumption continues during apnoea, gradual loss of alveolar volume/reduction in pressure. If upper airway remains patent, gas can be drawn into lower airways and oxygenation can continue and delay desaturation.

HFNO / THRIVE works by a combination of the delivery of humidified and warmed high flow air / oxygen, generation of positive airway pressure, improved respiratory mechanics, pharyngeal deadspace washout, apnoea oxygenation and ventilation.

Limitations:

1. Airway must be patent but can be significantly reduced

2. Secretions can accumulate

3. Morbid Obesity – shorter duration of apnoea before desaturation, more rapid desaturation

4. CO2 accumulation – without hypoxia / raised ICP

5. Epistaxis and skull fractures with the potential risk of airway soiling and pneumocephalus

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Patel A, Nouraei SA. Transnasal Humidified Rapid-Insufflation Ventilatory Exchange (THRIVE): a physiological method of increasing apnoea time in patients with difficult airways. Anaesthesia. 2015; 70: 323-9

b. Hermez LA, Spence CJ, Payton MJ, Nouraei SAR, Patel A, Barnes TH. A physiological study to determine the mechanism of carbon dioxide clearance during apnoea when using transnasal humidified rapid insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE). Anaesthesia. 2019; 74: 441–9

c. Mir F, Patel A, Iqbal R, Cecconi M, Nouraei SAR. A randomised controlled trial comparing transnasal humidified rapid insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE) pre-oxygenation with facemask pre-oxygenation in patients undergoing rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2017; 72: 439–43

d. Humphreys S, Lee-Archer P, Reyne G, Long D, Williams T, Schibler A. Transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE) in children: a randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017; 118: 232–8

e. Lodenius å., Piehl J, Östlund A, Ullman J, Jonsson Fagerlund M. Transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE) vs. facemask breathing pre-oxygenation for rapid sequence induction in adults: a prospective randomised non-blinded clinical trial. Anaesthesia. 2018; 73: 564–71

f. Patel A, El‐Boghdadly K. Apnoeic oxygenation and ventilation: go with the flow. Anaesthesia. 2020; 75: 1002–5

g. Sud A, Patel A. THRIVE: five years on and into the COVID-19 era. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2021;126: 768-73

h. Patel A, El-Boghdadly K. Facemask or high-flow nasal oxygenation: time to switch? Anaesthesia. 2022; 77: 7-11

i. Rummens N, Ball DR. Failure to THRIVE. Anaesthesia. 2015. (epub)

j. Levitan R. NO DESAT! Emergency Physicians Monthly. 2010 (online)

| Useful but use with caution - know its limitations and dangers! |

A useful piece of equipment, but one not everyone will be familiar with. Main function is as a stopgap to maintain tracheal access & facilitate ETT exchange. They are long, hollow, radiopaque, soft-tipped tubes – types for use with single / double lumen tubes.

There are different sizes for different functions (see chart). All users MUST be trained & knowledgeable of how to use such devices together with their limitations and dangers. The Gordon Ewing case makes for tragic reading – but highlights this point. Essential reading for airway practitioners.

NEVER insert beyond 26cm and NEVER insufflate with an oxygen flow >2L/min. (or just NEVER insufflate with oxygen)

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Sheriffdom of Glasgow and Strathkelvin. Determination of Sheriff Linda Margaret Ruxton in Fatal Accident Inquiry in the Death of Gordon Ewing. 2010 FAI 15 (online)

b. Benumof JL. Airway exchange catheters: simple concept, potentially great danger. Anesthesiology. 1999; 91: 342-4

c. Moyers G, McDougle L. Use of the Cook airway exchange catheter in "bridging" the potentially difficult extubation: a case report. AANA Journal. 2002; 70: 275-8

d. A dangerous tracheal tube exchange from AOD. 2016 - video (online)

e. Change of Endotracheal tube over tube exchanger. 2019 - video (online)

| So useful, but know its limitations! |

An amazingly useful piece of equipment – every airway practitioner should be familiar with. Main function of the Aintree Intubation Catheter is to facilitate intubation through a supraglotttic airway device because it is designed to fit over a 4mm flexible bronchoscope. It is a long, 56cm, hollow, semi-rigid, powder blue, polyurethane catheters which accommodates an ETT 7mm or larger.

NEVER insert beyond 26cm and NEVER insufflate with an oxygen flow >2l/min (..or just NEVER insufflate)

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Padmanabhan R, McGuire B, Morris A. Fibreoptic guided tracheal intubation through supraglottic airway device (SAD) using aintree intubation catheter. 2011 (online)

b. Gruenbaum SE, Gruenbaum BF, Tsaregorodtsev S, Dubilet M, Melamed I, Zlotnik A. Novel use of an exchange catheter to facilitate intubation with an Aintree catheter in a tall patient with a predicted difficult airway: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2012; 13:108

c. Phipps S, Malpas G, Hung O. A technique for securing the Aintree Intubation Catheter™ to a flexible bronchoscope. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018; 65: 329-30

d. Cook Medical. Aintree Intubation Catheter (online)

e. Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Fibreoptic Guided Intubation through SGA using Aintree Intubation Catheter - video (online)

| with thanks to Imran Ahmad for his expert contributions |

Awake Techniques – there are key skill for an airway manager.

Topicalization is key (if right, may not need sedation). Top tips:

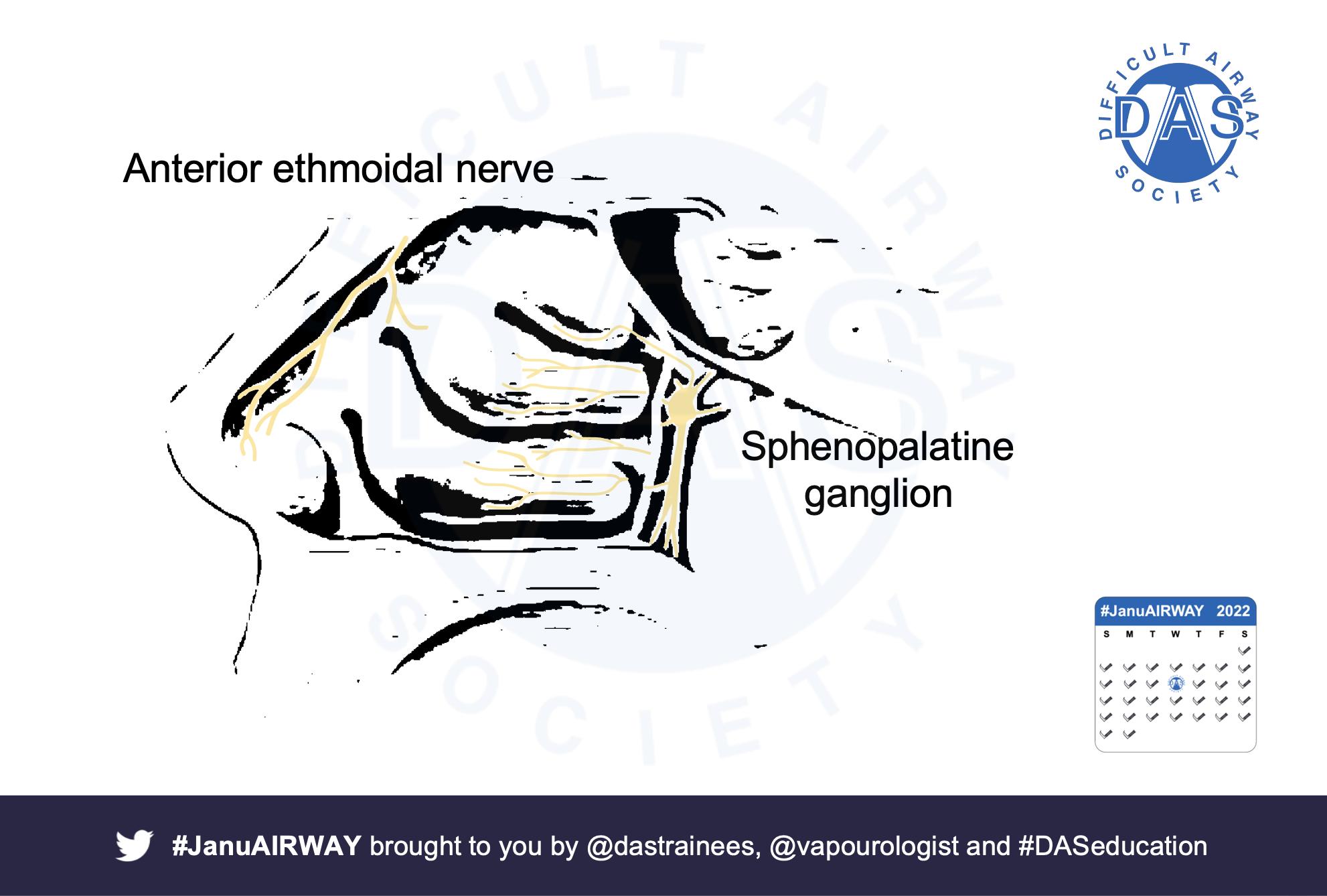

• Know nerve supply – CN V, IX & X.

• Block Ant.ethmoidal AND Sphenopalatine ganglion supply nasal septum

• Often you don’t need high dose LA if in right spot – this video is Tom Lawson after only gargling instilagel.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pzo_1TJZSEY

Fibreoptic scopes have advanced in recent years. It is important for airway managers to be familiar with and have knowledge of the ergonomics and the basics of the flexible bronchoscope.

• Know your equipment – set-up, usage and limitations

• Two positions for scope handling – Bazooka (facing patient) or Statue of Liberty (standing at head end)

Ancillary equipment can make or break an awake intubation. These can be broken down into 3 main types:

• Those which aid oxygen delivery

• Those which aid drug delivery

• Those which aid scope delivery (oral airways)

There are many different recipes for ATI. It is worth being familiar with the different drugs that can be used and recommend using the DAS approach to ATI.

There are a lot of potential problems that can be encountered during ATI – these need to be planned for. Be familiar with the basics of troubleshooting, complications and how to manage unsuccessful ATI.

Remember HFNO can help and a good knowledge of airway pharmacology is essential for awake techniques.

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Ahmad I, El-Boghdadly K, Bhagrath R, Hodzovic I, McNarry AF, Mir F, O'Sullivan EP, Patel A, Stacey M, Vaughan D. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for awake tracheal intubation (ATI) in adults. Anaesthesia. 2020; 75: 509-28

b. Royal Free Anaesthesia. How to topicalise the airway for awake fiberoptic intubation (AFOI) - video (online)

c. Bailin S. Awake Tracheal Intubation - video (online)

d. Awake Airway Management. Videolaryngoscopic awake tracheal intubation, no sedationvideo (online)

| niche anaesthesia, but fascinating |

This is a bit more niche in anaesthesia / airway management, but fascinating. There are 2 modes of jet ventilation:

• Low Frequency (<60 jets/min) &

• High Frequency (>60).

Frequency determines device. 2 commonly used devices are the Manujet (modified hand operated Sanders injector) or Monsoon (specialised jet ventilator).

There are several different potential mechanisms to apnoic oxygenation during High Frequency Jet Ventilation, including:

• Bulk flow

• Laminar flow

• Taylor dispersion

• Pendelluft

• Molecular diffusion

• Cardiogenic mixing

Key clinical pearl is the critical airway diameter for exhalation. Dworkin et al showed that jetting across a glottis <4.0 - 4.5mm in diameter leads to gas trapping, independent of jet ventilator settings. There MUST be a path for exhalation.

3 route for jet ventilation:

• Supraglottic – attached to a surgical laryngoscope

• Subglottic – using a specialised jet ventilation catheter

• Transtracheal – using a cannula via the cricothyroid membrane

Increasingly jet ventilation is being used outside of ENT, in interventional radiology and cardiac catheter labs to improve image quality.

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Pearson KL, McGuire BE. Anaesthesia for laryngo-tracheal surgery, including tubeless field techniques. British Journal of Anaesthesia Education. 2017; 17: 242-8

b. Patel C. Chet Patel describes the anaesthetic technique of jet ventilation - video (online)

c. Anaesthesia Galway. Manujet Ventilator - video (online)

d. Sivasambu B, et al. Initiation of a High-Frequency Jet Ventilation Strategy for Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation: Safety and Outcomes Data. JACC Clinical Electrophysiology. 2018; 4: 1519-25

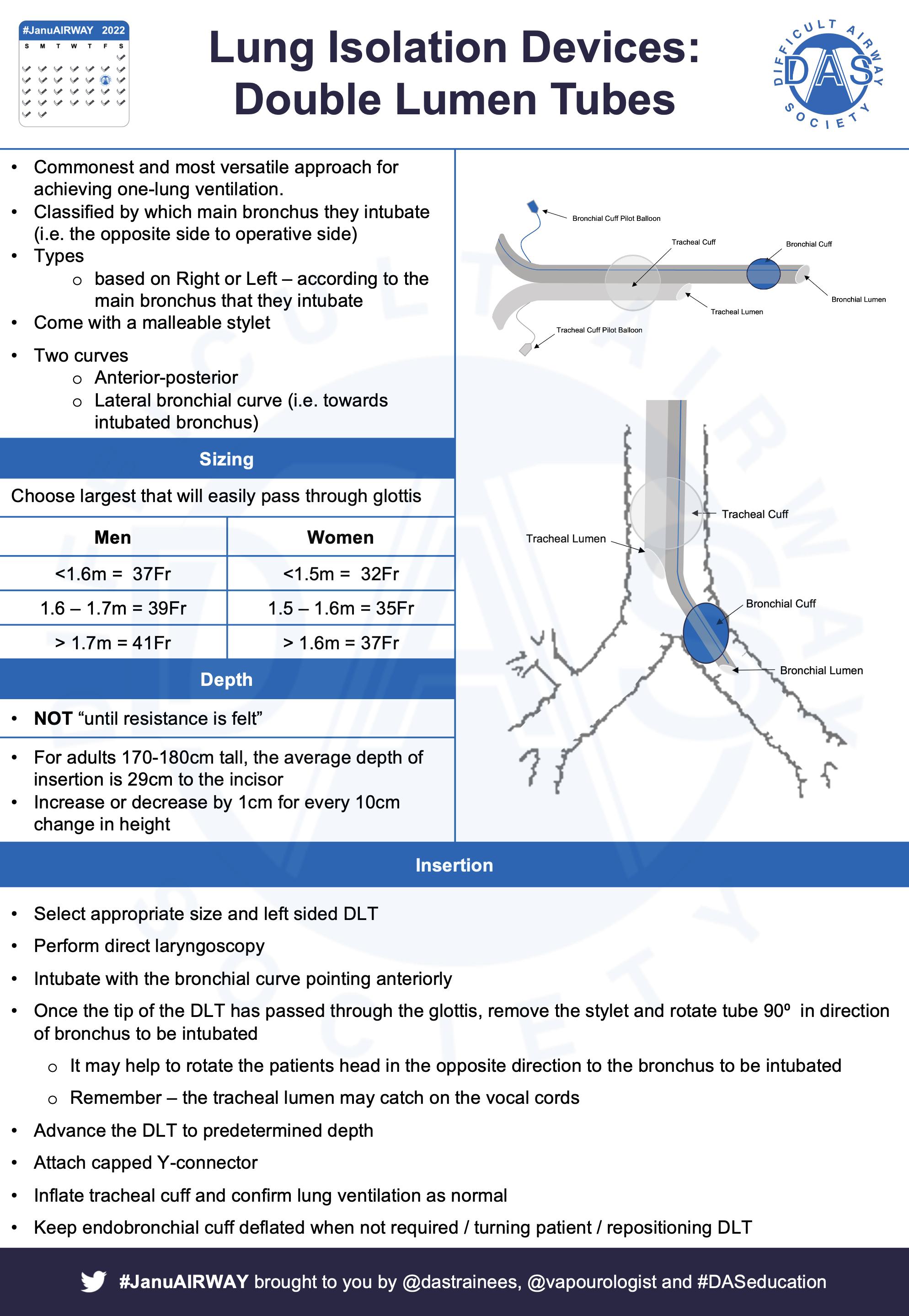

There are several indications for One Lung Ventilation (OLV). The commonest are thoracic surgery & some oesophagectomies. There are essentially three ways to achieve OLV:

• Use of a double lumen tube

• Use of a bronchial blocker

• Elective endobronchial intubation

The key physiological change is the creation of a large shunt – deoxygenated blood (which would normally be oxygenated), returns to the left heart resulting in hypoxaemia.

Often OLV is done in the lateral decubitus position. This has several effects on V/Q relations. As we can see in this diagram.

Evolution is amazing, because we have a friend to help us deal with shunt – hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. The bottom line is the mechanism is complicated - it’s biphasic, aims to decrease shunt to non-ventilated lung and can be influenced by several factors.

• Choose your airway wisely – get it right first time – use a fiberoptic scope

• If using bronchial blocker – consider going outside ETT.

• Be aware of physiological interplay

• Plan to deal with hypoxaemia

A knowledge of bronchoscopic anatomy is incredibly useful in anaesthesia / critical care –especially when performing OLV.

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Ashok V, Francis J. A practical approach to adult one-lung ventilation. British Journal of Anaesthesia Education. 2018; 18: 69-74

b. Bronchoscopy Simulator (online)

c. Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Double Lumen Tube Training video. 2020 - video (online)

d. Bronchial Blocker Insertion. 2012 - video (online)

e. Bronchial Blockers: EZ-Blocker. 2016 - video (online)

| with thanks to Brendan McGrath for his expert contributions |

More than just an ETT through the neck. Tracheostomies have potentially been performed since ancient Egypt. The first nonemergency tracheostomy was thought to be performed by Asclepiades. He was also a proponent of music therapy – might be of interest to Veena.

There are 4 basic indications for tracheostomy:

1. Facilitate prolonged (or weaning from) mechanical ventilatory support.

2. Provide a patent airway in cases of actual or threatened upper airway obstruction.

3. Provide a degree of airway protection, usually associated with central neurological or bulbar neuromuscular conditions.

4. Facilitate clearance of pulmonary secretions where coughing is inadequate. What physiological changes are associated with tracheostomies?

1. Upper airway natural humidification is completely or at least partially bypassed –additional humidification is essential

2. Reduced dead space – may help with work of breathing

3. Difficult or impossible vocalisation without dedicated strategies

4. Impaired swallowing

Tracheostomies can be performed using either a surgical or percutaneous technique. There are 3 main surgical techniques:

• Surgical window

• Slit type

• Björk flap - There are 2 reasons to mention Björk flaps really – 1 they often have a confusing anterior suture which needs to be noted on the bedhead sign; and the Swedish cardiothoracic surgeon who described them has one of the best names in medicine: Viking Björk!

An important difference is time for tract maturity:

• Percutaneous = 7 - 10 days

• Surgical = 2 - 4 days

Also important in decannulation as a false tract can occur if re-inserting before tract maturity!

MUST establish whether upper airway is present – i.e. tracheostomy or laryngectomy (neck-only breather). All patients with a tracheostomy or laryngectomy should have the appropriate bed head sign indicating type, size and date of insertion. NTSP have great resources available on their website to support this.

NAP4 & NCEPOD show poor outcomes still occur. NTSP has fantastic algorithms for both emergency tracheostomy and laryngectomy management.

There’s a lot of important aspects to tracheostomy care – check out this amazing resource from Portsmouth Intensive Care Unit.

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. McGrath BA, Bates L, Atkinson D, Moore JA; National Tracheostomy Safety Project. Multidisciplinary guidelines for the management of tracheostomy and laryngectomy airway emergencies. Anaesthesia. 2012; 67: 1025-41

b. National Tracheostomy Safety Project (NTSP) resources (online)

c. Lewith H, Athanassoglou V. Update on management of tracheostomy. British Journal of Anaesthesia Education. 2019; 19: 370-376

d. Paulich S, Kelly FE, Cook TM. 'Neck breather' or 'neck-only breather': terminology in tracheostomy emergencies algorithms. Anaesthesia. 2019; 74: 947

e. Pracy JP, Brennan L, Cook TM, Hartle AJ, Marks RJ, McGrath BA, Narula A, Patel A. Surgical intervention during a Can't intubate Can't Oxygenate (CICO) Event: Emergency Front-of-neck Airway (FONA)? British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2016; 117: 426-8

f. El-Wajeh Y, Varley I, Raithatha A, Glossop A, Smith A, Mohammed-Ali R. Opening Pandora's box: surgical tracheostomy in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2020; 125: e373-5

| with thanks to Alistair McNarry for his expert contributions |

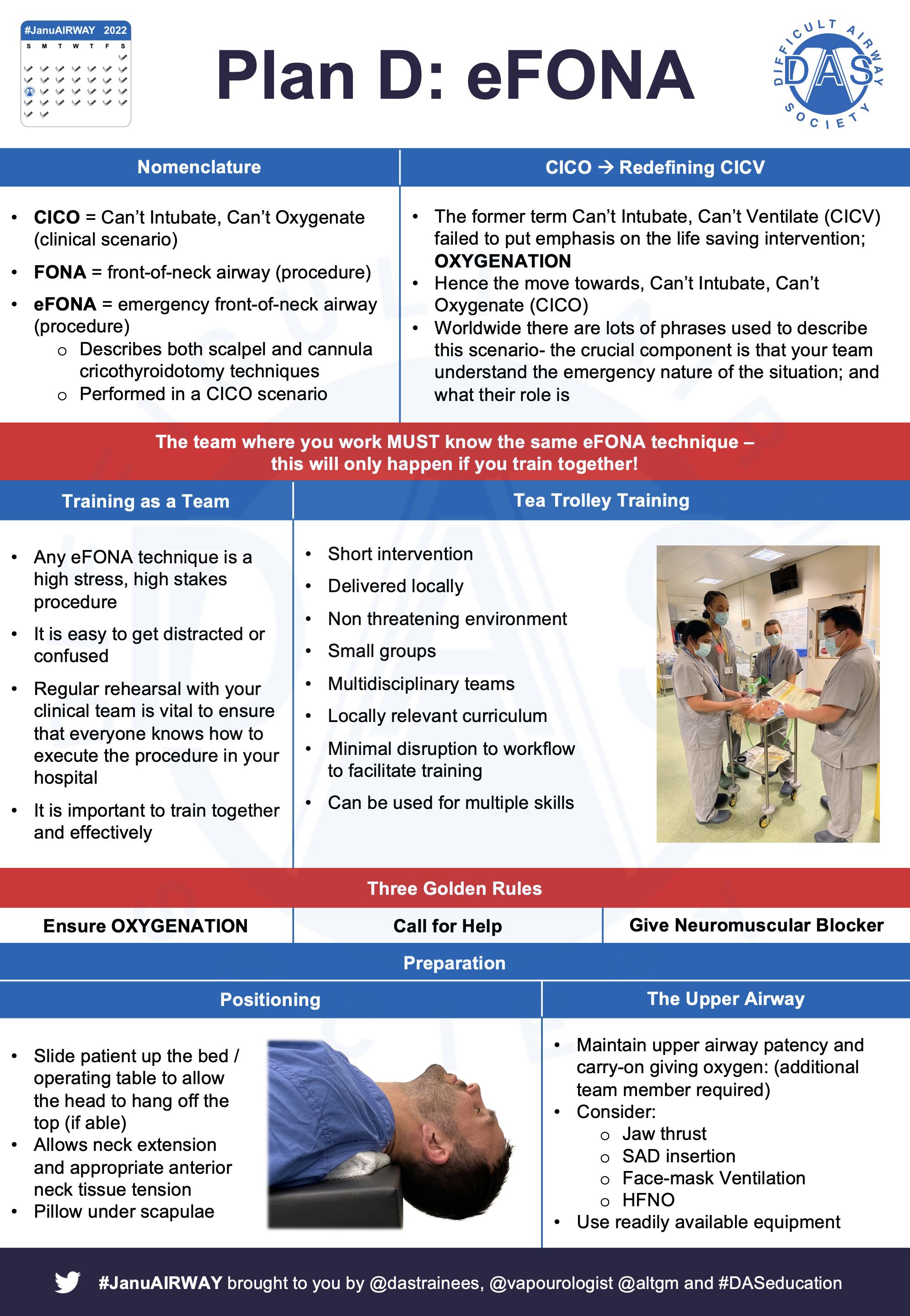

Language around this scenario is continually evolving. Whether its referred to as CICO - Can’t intubate, Cant Oxygenate or CICV - Cant Intubate, Cant Ventilate; it is important to recognise this is a scenario. They all describe the scenario where all other attempts at airway management and oxygen delivery have failed. Whereas eFONA (emergency front-of-neck airway) is a procedure carried out in response to a CICO scenario.

This is a rare event and raises a dichotomy.

i. If when conducting an airway assessment you feel an eFONA might be required, STOP, get help and consider an airway management plan that avoids this requirement (eg an awake technique - see section on awake tracheal intubation)

ii. However, if you are managing a patient’s airway and all other attempts at oxygenation have failed then you must PROCEED to eFONA without delay.

Before commencing an eFONA technique ensure that a large dose of neuromuscular blocking agent has been given (treats laryngospasm and paralyses the patient).

Know your technique before you are ever required to do it, rehearse it mentally

i. where would you stand

ii. who would you send for equipment

iii. how would you extend the neck etc

In adults DAS guidelines recommend scalpel eFONA techniques (final common pathway of CICO), however cannula technique is advocated in children between 1 and 8 years in a Can’t Intubate Can’t Oxygenate scenario (see the DAS APA guidelines). For more on the cannula technique check out Dr Andy Heard’s work at the Perth ‘wet’ lab

There are 2 anatomical scenarios for eFONA – palpable and impalpable anatomy.

DAS guidelines recommend everyone should know scalpel eFONA techniques (scalpel bougie tube (palpable anatomy), scalpel finger bougie tube (impalpable anatomy).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B8I1t1HlUac

The most difficult part of the process is making the decision to pick up the scalpel. Mental models and thinking tools like the Vortex can be useful. Check out Nicholas Chrimes & Peter Fritz's work

Remember you’re not alone in having airway skills. Remember your surgical colleagues & involve them early. But also remember not all surgeons will feel comfortable in performing an eFONA - in that it case it will have to be YOU!

Training in eFONA is vital - not just for you. Train everyone who might be involved in an eFONA event - nursing staff, anaesthetic assistants, scrub nurses (they are always there when you are doing an operation regardless of the time of the day).

Training MUST use the locally available equipment - please make sure that your plan for eFONA is deliverable where you work (and remember that can change from hospital to hospital).

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, Mendonca C, Bhagrath R, Patel A, O'Sullivan EP, Woodall NM, Ahmad I; Difficult Airway Society intubation guidelines working group. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2015; 115: 827-48

b. Higgs A, McGrath BA, Goddard C, Rangasami J, Suntharalingam G, Gale R, Cook TM; Difficult Airway Society; Intensive Care Society; Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine; Royal College of Anaesthetists. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018; 120: 323-52

c. Cook TM, El-Boghdadly K, McGuire B, McNarry AF, Patel A, Higgs A. Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: Guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2020; 75: 785-99

d. Heard A, Dinsmore J, Douglas S, Lacquiere D. Plan D: cannula first, or scalpel only? British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2016; 117: 533-5

e. Mann CM, Baker PA, Sainsbury DM, Taylor R. A comparison of cannula insufflation device performance for emergency front of neck airway. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2021; 31: 482-90

f. Chrimes N, Fritz P. The Vortex Approach to airway management (online)

g. Heard AM. DrAMBHeardAirway YouTube Channel (online)

| with thanks to Anil Patel, Elizabeth Ross, Sadie Khwaja and Adam Donne |

| for their expert contributions |

The Obstructed Airway - think: NOLIMBS

• Nose, Nasal Cavity and Nasopharynx

• Oral Cavity and Oropharynx

• Larynx, Laryngopharynx and Extra-thoracic (subglottic) Trachea

• Intra-thoracic

• Malacias

• Bleeding

• SVC Obstruction

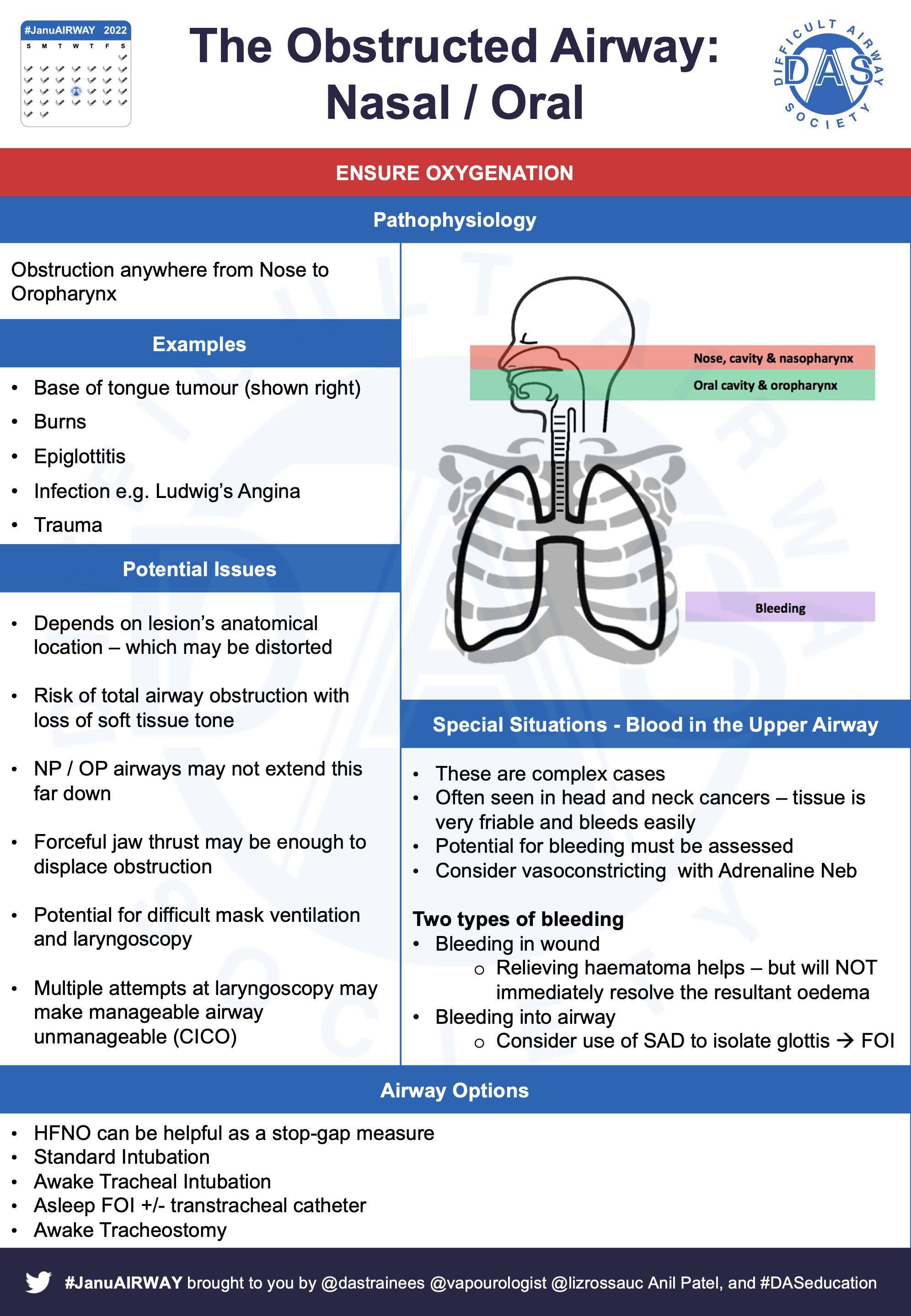

Nasopharyngeal and Oropharyngeal Airway Obstruction

Possible issues:

• Risk of total obstruction with low tone

• Distorted anatomy and/or trismus

• Nasopharyngeal/Oropharyngeal airway too short?

• Strong jaw thrust may/may not relieve obstruction

• Difficult mask ventilation and/or laryngoscopy

• Repeated laryngoscopy may make a manageable airway unmanageable.

Planning in airway obstruction is key. Nasendoscopy can save lives here! ASSESSMENT informs STRATEGY. Remember the decision-making process is multifactorial and it is important to maintain situational awareness.

In severe Nasal/Oral and Naso-Oro-Pharyngeal obstruction an awake technique may be advantageous. Options may include:

• HFNO as a helpful stop-gap measure

• Standard Intubation

• ATI/AFOI

• Awake/asleep FOI +/- transtracheal catheter

• Awake/asleep tracheostomy

Laryngeal / Laryngopharyngeal Airway Obstruction (Periglottic)

Often the most challenging for the general anaesthetist. Issues:

• Must discuss with ENT colleagues

• Preoperative nasendoscopy by experienced nasendoscopist is very helpful

• AFOI may worsen obstruction – cork in bottle

• Inhalational induction will be difficult

Key Q's

• Is the obstruction static or dynamic?

• Can an ETT be passed through the airway?

Options:

• May be able to pass ETT depending on narrowing - consider using a micro laryngeal tube or jet ventilation catheter.

• Apnoeic (HFNO) or intermittent oxygenation/intubation technique – depending on type of surgery (elective/emergent)

• Awake Tracheal Intubation

• Transtracheal catheter (+/- subsequent jet ventilation)

• Awake tracheostomy

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Ahmad I, El-Boghdadly K, Bhagrath R, Hodzovic I, McNarry AF, Mir F, O'Sullivan EP, Patel A, Stacey M, Vaughan D. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for awake tracheal intubation (ATI) in adults. Anaesthesia. 2020; 75: 509-28

b. Lynch J. Crawley SM. Management of airway obstruction. British Journal of Anaesthesia Education. 2017; 18: 46-51

c. Bryant H. Batuwitage B. Management of the Obstructed Airway. Anaesthesiology: Tutorial of the Week. 2016 (online)

d. Bruce IA, Rothera MP. Upper airway obstruction in children. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2009; 19(S1): 88-99

e. McAvoy J, Ewing T, Nekhendzy V. The value of preoperative endoscopic airway examination in complex airway management of a patient with supraglottic cancer. Journal of Head & Neck Anesthesia. 2019; 3: e19

Larynx and Extrathoracic Tracheal Airway Obstruction

Presents a unique set of challenges. Physiology:

• In theory a fixed obstructive lesion (eg tracheal stenosis) is unaffected by the respiratory cycle or anaesthesia induction

• Extrathoracic lesions tend to be better in expiration as positive pressure splints the airway open

Issues:

• Laryngoscopy likely to be uneventful – however the major concern is the inability to pass an ETT atraumatically beyond the level of obstruction

• Nasendoscopy can be useful to view lesion

• AFOI may cause ‘cork in bottle’ effect depending on lesion size and location of the obstruction or stenosis

• Consider use of tubeless techniques for airway intervention where possible eg foreign body removal or tumour debulking

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Nouraei SAR, Girgis M, Shorthouse J, El-Boghdadly K, Ahmad I. A multidisciplinary approach for managing the infraglottic difficult airway in the setting of the Coronavirus pandemic. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 2020; 31: 128-37

b. Scholz A, Srinivas K, Stacey MR, Clyburn P. Subglottic stenosis in pregnancy. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2008; 100: 385-8

c. Ellis H, Iliff HA, Lahloub FMF, Smith DRK, Rees GJ. Unexpected difficult tracheal intubation secondary to subglottic stenosis leading to emergency front-of-neck airway. Anaesthesia Reports. 2021; 9: 90-94

d. Phillips JJ, Sansome AJ. Acute infective airway obstruction associated with subglottic stenosis. Anaesthesia. 1990; 45: 34-5

e. Bulbulia BA, Ahmed R. Anaesthesia and subglottic airway obstruction. South African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 2011; 17: 182-4

f. Venugopal N, Youssef M, Nortcliffe S. Airway management in a case of critical sub-glottic stenosis: The use of a preformed tracheal tube. The Internet Journal of Anesthesiology 2007; 15:

Intrathoracic Airway Obstruction

Again, presents its own set of challenges. Issues:

• Upper and mid lesions are usually considered lower risk – due to potential to pass reinforced ETT beyond the level of obstruction

• Lower tracheal / Bronchial lesions are high risk and best managed in specialist centres due to increased difficulty siting an endobronchial tube and rigid bronchoscope as a rescue manoeuvre beyond level of obstruction

• A CT scan is mandatory (except in life-threatening scenarios)

• Sudden obstruction can occur at ANY time

• Remember there is potential for compression of the heart or great vessels

Severe Obstruction Considerations:

• Maintain the patient’s preferred position

• Spontaneous ventilation may beneficial - negative intrapleural pressure helps splint airway open and IPPV may cause airway collapse

• Many centres use IV induction techniques

• Ketamine - preserves chest wall tone and FRC

• Have a back up plan

Potential rescue manoeuvres:

In an emergency – consider passing an ETT tube & then placing a jet catheter (e.g. Cook or Aintree) beyond obstruction. Alternatively, most MLTs are long enough to reach the carina and should be available when managing patients with airway obstruction.

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Kapnadak SG, Kreit JW. Stay in the loop! Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2013; 10: 166-71

b. Nakajima A, Saraya T, Takata S, Ishii H, Nakazato Y, Takei H, Takizawa H, Goto H. The sawtooth sign as a clinical clue for intrathoracic central airway obstruction. BMC Research Notes. 2012; 5: 388

c. Ahuja S, Cohen B, Hinkelbein J, Diemunsch P, Ruetzler K. Practical anesthetic considerations in patients undergoing tracheobronchial surgeries: a clinical review of current literature. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2016; 8: 3431-41

Malacias

Malacias are a cause of rare dynamic airway obstruction (congenital or acquired) due to loss of support (by widening of both the cartilaginous arch and the membranous trachealis)

• Decreased intratracheal pressure + increased intrathoracic pressure lead to airway compression

• Severity is proportional to expiratory force

• Intrathoracic and extrathoracic malacia may collapse at different points in the respiratory cycle

Issues:

• Obstruction can occur even in asymptomatic patients

• Aim to maintain spontaneous ventilation

• Emergency management = Positive pressure (to splint airways open) or bypassing obstruction

• Surgery depends on the anatomical location and extent

• Consider extubating deep (to avoid coughing) or directly to CPAP or HFNO

Bleeding & Airways

Need to consider “WHERE” the bleeding is coming from. In general there are 3 possibilities:

• Above (Nasal Cavity / Nasopharynx / Oral Cavity / Oral Cavity / Laryngopharynx)

• Below (Tracheal / Lung / Oesophagus / GI)

• Around airway (consider full circumference of airway - any haematoma in the airway can cause localised airway oedema and/or airway compression)

Airway obstruction due to neck haematoma:

• Can be fatal

• Is normally due to laryngeal oedema NOT tracheal compression

• Need to open wound immediately and manually evacuate haematoma to relieve pressure –think SCOOP

See guidelines from DAS, BAETS and ENT-UK.

SVC Obstruction

Obstruction below the thoracic inlet (cancer / vascular / infection / thrombosis).

• Pemberton’s sign useful (face flushing on raising arms)

• Valsalva challenge - syncope indicates a risk of complete vascular obstruction

• Severe cases need treatment (intravascular stenting by interventional radiology) BEFORE general anaesthesia

Airway Options

• Depend on level and degree of obstruction

• If the obstruction is at or above thoracic inlet standard laryngoscopy, jet ventilation or rigid bronchoscopy tend to suffice

• If the obstruction is below the thoracic inlet - awake techniques, jet ventilation or rigid bronchoscopy may be preferred.

If the patient cannot be treated preoperatively

• Keep the patient sat up

• High flow O2 or HFNO

• Vascular Access:

✦ Large bore, lower limb IV access – consider Rapid Infusion Catheter or Swann Introducer

✦ Arterial line - consider lower limb also

• Smooth IV induction to avoid coughing (may be slow)

• There is potential for cerebral oedema which may lead to slow wakening and/or recovery

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

1. Austin J, Ali T. Tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia in children: pathophysiology, assessment, treatment and anaesthesia management. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2003; 13: 3-11

2. Findlay JM, Sadler GP, Bridge H, Mihai R. Post-thyroidectomy tracheomalacia: minimal risk despite significant tracheal compression. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2011; 106: 903-6

3. Sajid B, Rekha K. Airway Management in Patients with Tracheal Compression Undergoing Thyroidectomy: A Retrospective Analysis. Anesthesia Essays Researches. 2017; 11: 110-6

4. Chaudhary K, Gupta A, Wadhawan S, Jain D, Bhadoria P. Anesthetic management of superior vena cava syndrome due to anterior mediastinal mass. Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology. 2012; 28: 242-6

5. Kristensen MS, McGuire B. Managing and securing the bleeding upper airway: a narrative review. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2020; 67: 128-140

| with thanks to Alistair Baxter and Adam Donne for their expert contributions |

The difficult paediatric airway = #SCARY but rare! Upper airway obstruction in children – broad range of presentations, three important diagnoses; Croup, Epiglottitis and Inhaled Foreign Body.

Remember 2 types of airway obstruction- anatomical and physiological.

Top tip from Alistair Baxter: Remember that a Macintosh blade is in effect a hyperangulated blade in an infant and requires an intubation stylet shaped to match the curve of the blade.

TIVA is ever increasing in popularity as is “O”s up the nose and HFNO which is generally well tolerated, allows a true tubeless field, and can buy time during a difficult intubation.

Videolaryngoscopy as a first choice is evidently a better technique in children of all ages - see PeDI registry data

Fibreoptic intubation is an advanced technique that requires attention to detail and practice to understand all the steps involved. Intubation via a SAD is a nice technique and evidence is increasing that it can be used in children of all ages as a second choice technique.

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Humphreys S, Lee-Archer P, Reyne G, Long D, Williams T, Schibler A. Transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE) in children: a randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017; 118: 232-8

b. Bagshaw O, McCormack J, Brooks P, Marriott D, Baxter A. The safety profile and effectiveness of propofol-remifentanil mixtures for total intravenous anesthesia in children. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2020; 30: 1331-9

c. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. Clinical Practice Guidelines (online)

d. Von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Boda K, Chambers NA, Rebmann C, Johnson C, Sly PD, Habre W. Risk assessment for respiratory complications in paediatric anaesthesia: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2010; 376: 773-83

e. Difficult Airway Society and Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists. Paediatric Difficult Airway Guidelines (online)

f. Engelhardt T, Virag K, Veyckemans F, Habre W; APRICOT Group of the European Society of Anaesthesiology Clinical Trial Network. Airway management in paediatric anaesthesia in Europe-insights from APRICOT (Anaesthesia Practice In Children Observational Trial): a prospective multicentre observational study in 261 hospitals in Europe. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018; 121: 66-75

g. Jagannathan N, Sohn L, Fiadjoe JE. Paediatric difficult airway management: what every anaesthetist should know! British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2016; 117: i3-5

h. Walas W, Aleksandrowicz D, Kornacka M, Gaszyński T, Helwich E, Migdał M, Piotrowski A, Siejka G, Szczapa T, Bartkowska-Śniatkowska A, Halaba ZP. The management of unanticipated difficult airways in children of all age groups in anaesthetic practice - the position paper of an expert panel. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 2019; 27: 87

i. King MR, Jagannathan N. Best practice recommendations for difficult airway management in children-is it time for an update? British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018; 121: 4-7

j. Sun Y, Lu Y, Huang Y, Jiang H. Pediatric video laryngoscope versus direct laryngoscope: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2014; 24: 1056-65

k. Klabusayová E, Klučka J, Kosinová M, Ťoukálková M, Štoudek R, Kratochvíl M, Mareček L, Svoboda M, Jabandžiev P, Urík M, Štourač P. Videolaryngoscopy vs. Direct Laryngoscopy for Elective Airway Management in Paediatric Anaesthesia: A prospective randomised controlled trial. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2021; 38: 1187-93

l. Fiadjoe JE, Nishisaki A, Jagannathan N, Hunyady AI, Greenberg RS, Reynolds PI, Matuszczak ME, Rehman MA, Polaner DM, Szmuk P, Nadkarni VM, McGowan FX Jr, Litman RS, Kovatsis PG. Airway management complications in children with difficult tracheal intubation from the Pediatric Difficult Intubation (PeDI) registry: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2016; 4: 37-48

m. Gupta A, Sharma R, Gupta N. Evolution of videolaryngoscopy in pediatric population. Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology. 2021; 37: 14-27

n. Anderson BJ, Bagshaw O; Practicalities of Total Intravenous Anesthesia and Targetcontrolled Infusion in Children. Anesthesiology. 2019; 131: 164–185.

| with thanks to Nuala Lucas for her expert contributions |

Let’s start with some decision tools from a great review article

Failed intubation requires a different approach in Obstetrics. The 2015 OAA/DAS guidelines are really helpful for this! Covering planning to maximise safety for obstetric GA and the management of failed intubation.

The 2015 OAA/DAS guidelines also cover decision making – when to bail out / when to proceed and aftercare – which mustn’t be overlooked!

Here are some other papers / links that you might find useful:

a. Bonnet MP, Mercier FJ, Vicaut E, Galand A, Keita H, Baillard C; CAESAR working group. Incidence and risk factors for maternal hypoxaemia during induction of general anaesthesia for non-elective Caesarean section: a prospective multicentre study. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2020; 125: e81-7

b. Howle R, Onwochei D, Harrison SL, Desai N. Comparison of videolaryngoscopy and direct laryngoscopy for tracheal intubation in obstetrics: a mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2021; 68: 546-65

c. Odor PM, Bampoe S, Moonesinghe SR, Andrade J, Pandit JJ, Lucas DN; Pan-London Perioperative Audit and Research Network (PLAN), for the DREAMY Investigators Group. General anaesthetic and airway management practice for obstetric surgery in England: a prospective, multicentre observational study. Anaesthesia. 2021; 76: 460-71

d. McGuire B, Lucas DN. Planning the obstetric airway. Anaesthesia. 2020; 75: 852-5

| One part of a wider critically ill patient |

These can be particularly stressful airways to manage. It is important to remember they are one part of a wider critically ill patient. The principles of treatment/management are:

• Beware the isolated environment

• Plan for uncooperative patient

• Prevent aspiration

• Protect C-spine

• Plan for difficult airway

Define type of trauma early – blunt vs penetrating (neck divided into 3 zones), and assess for:

• Distorted anatomy

• Bleeding

• Subcutaneous Emphysema –injury to gas containing structure

• Other traumatic injury – e.g. head, thorax, abdomen, etc

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Jain U, McCunn M, Smith CE, Pittet JF. Management of the Traumatized Airway. Anesthesiology. 2016; 124: 199-206

b. Brown CVR, Inaba K, Shatz DV, Moore EE, Ciesla D, Sava JA, Alam HB, Brasel K, Vercruysse G, Sperry JL, Rizzo AG, Martin M. Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: airway management in adult trauma patients. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open. 2020; 5: e000539

c. Mercer SJ, Jones CP, Bridge M, Clitheroe E, Morton B, Groom P. Systematic review of the anaesthetic management of non-iatrogenic acute adult airway trauma. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2016; 117: i49-59

d. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Quality Statement 1: Airway Management. In: Trauma Quality Standard [QS166]. 2018 (online)

e. Crewdson K, Lockey D, Voelckel W, Temesvari P, Lossius HM; EHAC Medical Working Group. Best practice advice on pre-hospital emergency anaesthesia & advanced airway management. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 2019; 27: 6

f. Higgs A, McGrath BA, Goddard C, Rangasami J, Suntharalingam G, Gale R, Cook TM; Difficult Airway Society; Intensive Care Society; Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine; Royal College of Anaesthetists. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018; 120: 323-52

g. Wiles MD. Manual in-line stabilisation during tracheal intubation: effective protection or harmful dogma? Anaesthesia. 2021; 76: 850-3

| with thanks to Sarah Muldoon for her expert contributions |

Head Vs Spine. Elective Vs Emergency, So many points of interest for airway managers.

Key principles:

• Prevent rises in ICP

• Avoid hypoxia & low BP

• Consider potential for c-spine injury

• Be aware of positioning

• Beware potential difficult airway in neurosurgical pathology

• Beware of post-op issues e.g. haematoma post-ACDF

We can, in general, divide acute / emergency patients into 2 groups:

1. Cooperative – awake techniques may be the best option in anticipated difficulty

2. Uncooperative – asleep laryngoscopy or asleep FOI (consider LMA conduit)

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Elwishi M, Dinsmore J. Monitoring the brain. British Journal of Anaesthesia Education. 2019; 19: 54-9

b. Perelló-Cerdà L, Fàbregas N, López AM, Rios J, Tercero J, Carrero E, Hurtado P, Hervías A, Gracia I, Caral L, de Riva N, Valero R. ProSeal Laryngeal Mask Airway Attenuates Systemic and Cerebral Hemodynamic Response During Awakening of Neurosurgical Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology. 2015; 27: 194-202

c. Lockey DJ, Wilson M. Early airway management of patients with severe head injury: opportunities missed? Anaesthesia. 2020; 75: 7-10

d. McCredie VA, Ferguson ND, Pinto RL, Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Chapman MG, Burrell A, Baker AJ, Cook DJ, Meade MO, Scales DC; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Airway Management Strategies for Brain-injured Patients Meeting Standard Criteria to Consider Extubation. A Prospective Cohort Study. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2017; 14: 85-93

e. Langford RA, Leslie K. Awake fibreoptic intubation in neurosurgery. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2009; 16: 366-72

f. Yi P, Li Q, Yang Z, Cao L, Hu X, Gu H. High-flow nasal cannula improves clinical efficacy of airway management in patients undergoing awake craniotomy. BMC Anesthesiology. 2020; 20: 156

| with thanks to Andrew McKechnie and SOBA for their expert contributions |

Key principles:

• Ensure good positioning & adequate logistics

• Good preoxygenation with tight seal is essential

• Timely ETT placement

• Beware of extubation - risk of hypoxia /airway obstruction – minimise PEEP loss

Patients living with obesity frequently suffer from obstructive sleep apnoea. A sound understanding of its pathophysiology, investigation, diagnosis and perioperative management is really helpful

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Society for Obesity and Bariatric Anaesthesia. Anaesthesia of the Obese Patient. 2020 (online)

b. Lundstrøm LH, Møller AM, Rosenstock C, Astrup G, Wetterslev J. High body mass index is a weak predictor for difficult and failed tracheal intubation: a cohort study of 91,332 consecutive patients scheduled for direct laryngoscopy registered in the Danish Anesthesia Database. Anesthesiology. 2009; 110: 266-74

c. Kheterpal S, Martin L, Shanks AM, Tremper KK. Prediction and outcomes of impossible mask ventilation: a review of 50,000 anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2009; 110: 891-7

d. Association of Anaesthetists and Society for Obesity and Bariatric Anaesthesia. Perioperative management of the obese surgical patient. 2015 (online)

e. Hashim MM, Ismail MA, Esmat AM, Adeel S. Difficult tracheal intubation in bariatric surgery patients, a myth or reality? British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2016; 116: 557-8

f. Fox WT, Harris S, Kennedy NJ. Prevalence of difficult intubation in a bariatric population, using the beach chair position. Anaesthesia. 2008; 63: 1339-42

g. Moon TS, Fox PE, Somasundaram A, Minhajuddin A, Gonzales MX, Pak TJ, Ogunnaike B. The influence of morbid obesity on difficult intubation and difficult mask ventilation. Journal of Anesthesia. 2019; 33: 96-102

| don’t take off if you haven’t considered how to land the plane |

Needs planning, just like intubation.

Key principles:

• Most airway complications occur during extubation

• Extubation = elective event

• Get it right first time

• Consider risk factors for difficult extubation AND difficult re-intubation

See the DAS extubation guidelines

Pre-extubation risk assessment can include:

• Arterial blood gas - to assess adequacy of gas exchange, if in doubt

• Direct laryngoscopy or fiberoptic examination of laryngopharynx +/- other structures

• Leak test

Potential options for difficult extubation:

• Extubation directly onto HFNO or CPAP

• Airway exchange catheter / staged extubation catheter

• Switch to Supraglottic Airway Device under GA

• Remifentanil technique

• Prolonged intubation and sedation

• Tracheostomy

Looking specifically at the Cook Staged Extubation Set: An excellent, but maybe underknown piece of equipment. Consider in patients that may have:

• Inability to tolerate extubation / need for reintubation – e.g. obstruction, poor ventilation/ oxygenation, unable to protect airway

• Difficulty in re-establishing airway – known difficulty with intubation, injury, emergency, etc

Set consists of a wire, placed pre-extubation, & left in-situ post-extubation (usually well-tolerated) allows for rapid re-intubation via tapered catheter. Check out this video

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iuICquziUM8

Here are some papers / links that you might find interesting:

a. Batuwitage B, Charters P. Postoperative management of the difficult airway. British Journal of Anaesthesia Education. 2017; 17: 235-41

b. Parotto M, Cooper RM, Behringer EC. Extubation of the Challenging or Difficult Airway. Curr ent Anesthesiology Reports. 2020; 10: 334-40

c. Hagberg CA, Artime CA. Extubation of the perioperative patient with a difficult airway. Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology. 2014; 42: 295-301

d. Cavallone LF, Vannucci A. Review article: Extubation of the difficult airway and extubation failure. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2013; 116: 368-83

e. D'Silva DF, McCulloch TJ, Lim JS, Smith SS, Carayannis D. Extubation of patients with COVID-19. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2020; 125: e192-5

f. Furyk C, Walsh ML, Kaliaperumal I, Bentley S, Hattingh C. Assessment of the reliability of intubation and ease of use of the Cook Staged Extubation Set-an observational study. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 2017; 45: 695-9

g. McManus S, Jones L, Anstey C, Senthuran S. An assessment of the tolerability of the Cook staged extubation wire in patients with known or suspected difficult airways extubated in intensive care. Anaesthesia. 2018; 73: 587-93

h. Corso RM, Sorbello M, Mecugni D, Seligardi M, Piraccini E, Agnoletti V, Gamberini E, Maitan S, Petitti T, Cataldo R. Safety and efficacy of Staged Extubation Set in patients with difficult airway: a prospective multicenter study. Minerva Anestesiologica. 2020; 86: 827-34

i. Gentek Medical. Staged Extubaiton Set - video (online)

| “Guidelines are like toothbrushes. They are also like floss” | | @GongGasGirl #GAMC2021 |

DAS are probably best known for our guidelines. Recently, we have updated our methodology to ensure all guidelines documents are of sufficient rigour to include best evidence and the most clinically relevant recommendations. However, it is important to recognise they are just that –recommendations and guidelines. Guidelines are not intended to represent a minimum standard of practice, nor are they to be regarded as a substitute for good clinical judgement. They present key principles and suggested strategies for the management of certain clinical scenarios. They are intended to guide appropriately trained healthcare professionals. We have many DAS guidelines and have contributed to many others in partnership with other organisations, here are links to some:

a. Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, Mendonca C, Bhagrath R, Patel A, O'Sullivan EP, Woodall NM, Ahmad I; Difficult Airway Society intubation guidelines working group. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2015; 115: 827-48

b. Higgs A, McGrath BA, Goddard C, Rangasami J, Suntharalingam G, Gale R, Cook TM; Difficult Airway Society; Intensive Care Society; Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine; Royal College of Anaesthetists. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018; 120: 323-52

c. Difficult Airway Society Extubation Guidelines Group, Popat M, Mitchell V, Dravid R, Patel A, Swampillai C, Higgs A. Difficult Airway Society Guidelines for the management of tracheal extubation. Anaesthesia. 2012; 67: 318-40

d. Ahmad I, El-Boghdadly K, Bhagrath R, Hodzovic I, McNarry AF, Mir F, O'Sullivan EP, Patel A, Stacey M, Vaughan D. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for awake tracheal intubation (ATI) in adults. Anaesthesia. 2020; 75: 509-28

e. Mushambi MC, Kinsella SM, Popat M, Swales H, Ramaswamy KK, Winton AL, Quinn AC; Obstetric Anaesthetists' Association; Difficult Airway Society. Obstetric Anaesthetists' Association and Difficult Airway Society guidelines for the management of difficult and failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 2015; 70: 1286-306

f. Difficult Airway Society and Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists. Paediatric Difficult Airway Guidelines (online)

g. Iliff HA, El-Boghdadly K, Ahmad I, Davis J, Harris A, Khan S, Lan-Pak-Kee V, O'Connor J, Powell L, Rees G, Tatla TS. Management of haematoma after thyroid surgery: systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons and the British Association of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. Anaesthesia. 2022; 77: 82-95

h. McGrath BA, Bates L, Atkinson D, Moore JA; National Tracheostomy Safety Project. Multidisciplinary guidelines for the management of tracheostomy and laryngectomy airway emergencies. Anaesthesia. 2012; 67: 1025-41

Our guidelines have also been adapted to guide management of patients with COVID-19:

a. Cook TM, El-Boghdadly K, McGuire B, McNarry AF, Patel A, Higgs A. Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: Guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2020; 75: 785-99

Other airway organisations also have their own guidelines. Here are just a few from America, Canada and Australia and New Zealand (there are many more).

a. Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Connis RT, Abdelmalak BB, Agarkar M, Dutton RP, Fiadjoe JE, Greif R, Klock PA, Mercier D, Myatra SN, O'Sullivan EP, Rosenblatt WH, Sorbello M, Tung A. 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2022; 136: 31-81

b. Law JA, Broemling N, Cooper RM, Drolet P, Duggan LV, Griesdale DE, Hung OR, Jones PM, Kovacs G, Massey S, Morris IR, Mullen T, Murphy MF, Preston R, Naik VN, Scott J, Stacey S, Turkstra TP, Wong DT; Canadian Airway Focus Group. The difficult airway with recommendations for management--part 1--difficult tracheal intubation encountered in an unconscious/induced patient. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2013; 60: 1089-118

c. Law JA, Broemling N, Cooper RM, Drolet P, Duggan LV, Griesdale DE, Hung OR, Jones PM, Kovacs G, Massey S, Morris IR, Mullen T, Murphy MF, Preston R, Naik VN, Scott J, Stacey S, Turkstra TP, Wong DT; Canadian Airway Focus Group. The difficult airway with recommendations for management--part 2--the anticipated difficult airway. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2013; 60: 1119-38

d. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthesia & Faculty of Pain Medicine. Guideline for the management of evolving airway obstruction: transition to the Can’t Intubate Can’t Oxygenate airway emergency. 2017 (online)

Note: we have not provided the one pagers for this tweetorial as they are all freely available from the hyperlinks previous and are best viewed with the accompanying text.

| there are LOADS! |

The following pages do not form a definitive list.

Here are some papers / links on some lesser known eponymous syndromes that you might find interesting: