In 2024, analysis of routine data revealed that some of South Africa’s gains in child development and wellbeing are stalling, and may be starting to reverse. Young children are now more likely to live in poverty, suffer from food insecurity and malnutrition, and die before their fifth birthday than they were before the Covid-19 pandemic. In addition, the Thrive by Five Index found that fewer than half of 4-5-year-olds are developmentally on track.

This learning brief examines existing data on child development and wellbeing and what it signifies, and why we need accelerated action for children to turn the tide. It draws from two consolidated pieces of research released in 2024 by key partners, namely the South African Early Childhood Review and the Child Gauge.

South Africa’s National Development Plan (NDP) endorses two years of mandatory preschool education (Grade R and pre-Grade R), recognising early childhood development (ECD) as a critical driver of socio-economic transformation.1 The 2015 National Integrated Early Childhood Development Policy (NIECDP) outlines the government's commitment to guaranteeing equitable access to a full range of ECD services by 2030, and recognises that ECD is a universal right.2

Government has also made significant investments in the wellbeing of mothers and young children, including the provision of free healthcare for pregnant women and children under six years, the expansion of the Child Support Grant (CSG), and almost universal access to Grade R, providing a stable base on which families can build future health and prosperity.3

However, in the years following the Covid-19 pandemic, families and government departments have come under increasing pressure as rising poverty and poor economic prospects threaten young children’s health, survival and development.

“The Covid-19 pandemic erased gains made for young children in South Africa, presenting a massive setback we have not fully recovered from.”

– Dr Katharine Hall, Senior Researcher

at the Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town (UCT)4

The early years of a child’s life form the foundation for future success. Without the necessary support during this critical period, children are less likely to secure employment as adults and contribute meaningfully to the economy. According to the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund Child Poverty Study: “Although the direct cost of child poverty is significant,

around 10% of GDP, the loss of economic potential is an even greater cost. It is estimated that foregone earnings are around R1.3 trillion – or 18% of South Africa’s GDP.”5

In this brief, we synthesise findings contained in the South African Child Gauge 2024 and the South African Early Childhood Review (SAECR) 2024 – two important contributions to our understanding of child development in this country. The data, findings and much of the analysis are based on the work of the researchers, academics, experts and civil society partners who have contributed to these two reports. Both documents emphasise the need to strengthen our commitment to young children if we want to change our future. As the World Bank points out, strategic investments in early childhood development (ECD) yield the greatest returns in terms of reducing poverty, increasing prosperity, and creating “the human capital needed for economies to diversify and grow”.6

The SAECR 2024 consolidates data sources for the ‘Essential Package’ of ECD services and tracks the country’s progress toward established goals across various programmes and policy documents. The Essential Package supports children from conception to the age of six and includes five crucial interrelated components essential for all children:

Maternal and child health services;

Nutritional support;

Stimulation for early learning;

Support for primary caregivers; and Social services and protection.

1 Republic of South Africa. 2012. National Development Plan 2030: Our Future – make it work. Sherino Printers

2 Republic of South Africa. 2015. National Integrated Early Childhood Development Policy. Government Printers.

3 Slemming W, Biersteker L, Lake L. 2024. Invest early to drive national development. [Policy brief] Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town.

4 Ilifa Labantwana 2024. The South African Early Childhood Review 2024 shows that the situation of young children has worsened. There is now an important window to change course Accessed here: https://ilifalabantwana.co.za/sa-early-childhood-review-2024-press-release-2/

5 Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund. 2024. NMCF Child Poverty Study. Accessed here: https://www.nelsonmandelachildrensfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/ Nelson-Mandela-Children-report-FINAL-011124-2.pdf

6 World Bank. 2024 Early Childhood Development. Accessed here: https://tinyurl.com/3aybpk2r

South Africa has approximately seven million children under six years of age, and over a quarter of the country’s households include children in this demographic.7 Most of these children live in poor households, below the official “upper-bound” poverty line, and nearly 40% live in homes that do not have enough income to provide for basic nutritional needs.8 High household poverty rates make it essential for young children to have access to the Essential Package.

South Africa’s population is becoming increasingly urban, as a result of increasing urban births and migration.9 However, the country’s child population remains less urban than the adult population, partly because some urban settings such as informal settlements are not suitable environments in which to raise children, being under-serviced and often unsafe.10 The lack of available and affordable early learning programmes in urban areas also makes raising young children difficult, leading some parents to decide that their children should instead be cared for by family in rural areas.11

The pandemic and the associated lockdowns exacerbated unemployment rates and led to rising rates of child poverty. In an economy marked by slow development and a labour market that does not offer enough jobs for the country’s roughly 32 million working-age adults, unemployment remains high.12

8 Ibid.

9

10

11

12

of children under six live in households below the upper-bound poverty line.

POPULATION:

Nearly seven million children under six years of age.

POVERTY:

56% of children under the age of six lived in households below the upper-bound poverty line in 2019, now this has increased to seven out of 10 children.

39% live in households below the food poverty line (i.e. unable to meet basic nutritional needs).

WATER AND SANITATION:

29% of children under six live without piped water on site.

22% do not have access to a flush toilet or ventilated pit latrine.

URBAN AND RURAL DISTRIBUTION:

Nationally, 40% of young children live in rural areas; in Limpopo over 80% of young children live in rural households.

Simultaneously, there is a rise in the young urban population, and urban poverty and food insecurity are a growing concern.

COVID-19 IMPACT:

In Q4 2022, unemployment was at 33% (official) and 43% (broad).

57% of infants under one were in poverty in 2019, increasing to 72% in 2022

Source: SAECR 2024

Nearly 90% of children under the age of six in South Africa rely on the public health system. Key indicators of the quality of health service coverage and health outcomes for children include the neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality rates.13 Preliminary estimates for 2022 reveal that 30 out of every 1 000 live-born infants did not survive to their first birthday. The under-five mortality rate also rose sharply, from 29 per 1 000 live births in 2020 to 40 in 2022. This marks a troubling reversal of the steady decline in infant and under-five mortality rates observed in the decade preceding the pandemic.14

Antenatal care (ANC) provides a comprehensive range of health services for pregnant women, aiming to ensure safe pregnancies and births, improve nutrition for both mother and child, and offer counselling and support to help women have positive pregnancy experiences and prepare for childbirth.15 ANC access improved between 2016 and 2019, but Covid-19 led to a decline in early bookings for services across most provinces.

Vaccination coverage is a critical indicator of the health system's performance, and serves as a gateway to primary healthcare services, including growth monitoring, deworming, vitamin A supplementation, and appropriate care for ill children, as outlined in the Essential Package. While vaccination rates declined during the pandemic, they rebounded to 86% in 2021/22, nearing the Global Vaccine Action Plan target of 90%.16

“Antenatal attendance, postnatal follow up and immunisation rates all dropped during the pandemic. These health services had mostly recovered or even improved by 2022, but we need to ensure that there is continuity in maternal and child health services even in times of crisis.”

– Dr Colin Almeleh, Director at Ilifa Labantwana17

of children under six rely on public health services, with significant disparities in access and outcomes across provinces.

BUDGET AND HEALTH EXPENDITURE:

Health budget increased from R216 billion in 2019/20 to R237 billion in 2020/21.

IMMUNISATION:

Coverage rate recovered to 86% in 2021/22, nearing the target of 90%.

MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH INDICATORS:

Early antenatal care booking rates varied significantly across provinces post-pandemic.

79% of mothers attended postnatal visits within six days of giving birth in 2021/22.

MORTALITY RATES:

Infant Mortality Rate (IMR): Increased to 30 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2022, the highest since 2010.

Under-five Mortality Rate (U5MR): Increased from 29 per 1 000 live births in 2020 to 40 in 2022.

Neonatal Mortality Rate (NMR): Slightly increased during the pandemic, highlighting the need for improved neonatal care.

Source: SAECR 2024 13

15

16

Good nutrition, especially in the first 1 000 days of life, is vital for physical and cognitive development. Proper nutrition can help break intergenerational cycles of poverty and increase South Africa's GDP per capita by approximately 9%, highlighting its importance not only for children's wellbeing but also for national interests.18

Early in 2023, food inflation surpassed 14%, the greatest level since the global recession of 2008, and more than double the top inflation target limit.19 A rise in food poverty rates and food insecurity means children are more at risk of severe acute malnutrition.20 Stunting is the most common form of child malnutrition in South Africa.21 Results from the recent National Food and Nutrition Security Survey (NFNSS) conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) suggest that the under-five stunting rate has not shown any significant decline over the past eight years.22

Children are stunted if they are too short for their age – more than two standard deviations below the median, as defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Stunting usually occurs because of chronic undernutrition during pregnancy and in the first 1 000 days of life. It is influenced by the quantity, quality, and diversity of food; hygiene, water, and sanitation; recurrent infections and access to quality primary care; and other elements such as poverty and low maternal education.23

Stunting affects both physical and cognitive development. Stunted children are more likely to start school with developmental delays, perform poorly at school, be unemployed when they grow up, and suffer from chronic conditions such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes in adulthood.24

of children under the age of five are stunted (over 1.5 million children).

Incidence increased by 33% between 2020/21 and 2021/22.

15 000 children hospitalised due to SAM in 2022/23.

FOOD INSECURITY:

In 2022, 20% of children under six lived in households that ran out of food during the month due to lack of money.

26% of children under six lived in households that had to reduce their food range due to lack of money.

44% of infants exclusively breastfed at 14 weeks in 2021/22, down from 49% in 2019/20.

Source: SAECR 2024

17 Ibid.

18 Galasso E, Wagstaff A. 2019. The aggregate income losses from childhood stunting and the returns to a nutrition intervention aimed at reducing stunting. Economics & Human Biology. 34, 225-38.

19 Hall K, et al. SAECR 2024.

20 According to the World Health Organization, severe acute malnutrition in children aged 6–59 months is defined by extremely low weight-for-height/weight-for-length, the presence of bilateral pitting oedema, or a very low mid-upper arm circumference. Globally, severe acute malnutrition affects an estimated 19 million children under the age of five and is responsible for approximately 400 000 child deaths annually. https://www.who.int/tools/elena/interventions/sam-identification-inpatient

21 National Department of Health (NDoH), Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), and ICF. 2019. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016 [Edited by Stats SA].

22 Simelane T, Mutanga SS, Hongoro C, Parker W, Mjimba V, Zuma K, Kajombo R, Ngidi M, Masamha B, Mokhele T, Managa R, Ngungu M, Sinyolo S, Tshililo F, Ubisi N, Skhosana, Ndinda C, Sithole M, Muthige M, Lunga W, Tshitangano F, Dukhi NF, Sewpaul R, Mkhongi A, Marinda E. 2023. National Food and Nutrition Security Survey: National Report HSRC: Pretoria.

23 Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, et al. 2013. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 382, 427–451

24 Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Blössner M, Black RE. 2004. Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 80, 193–198.

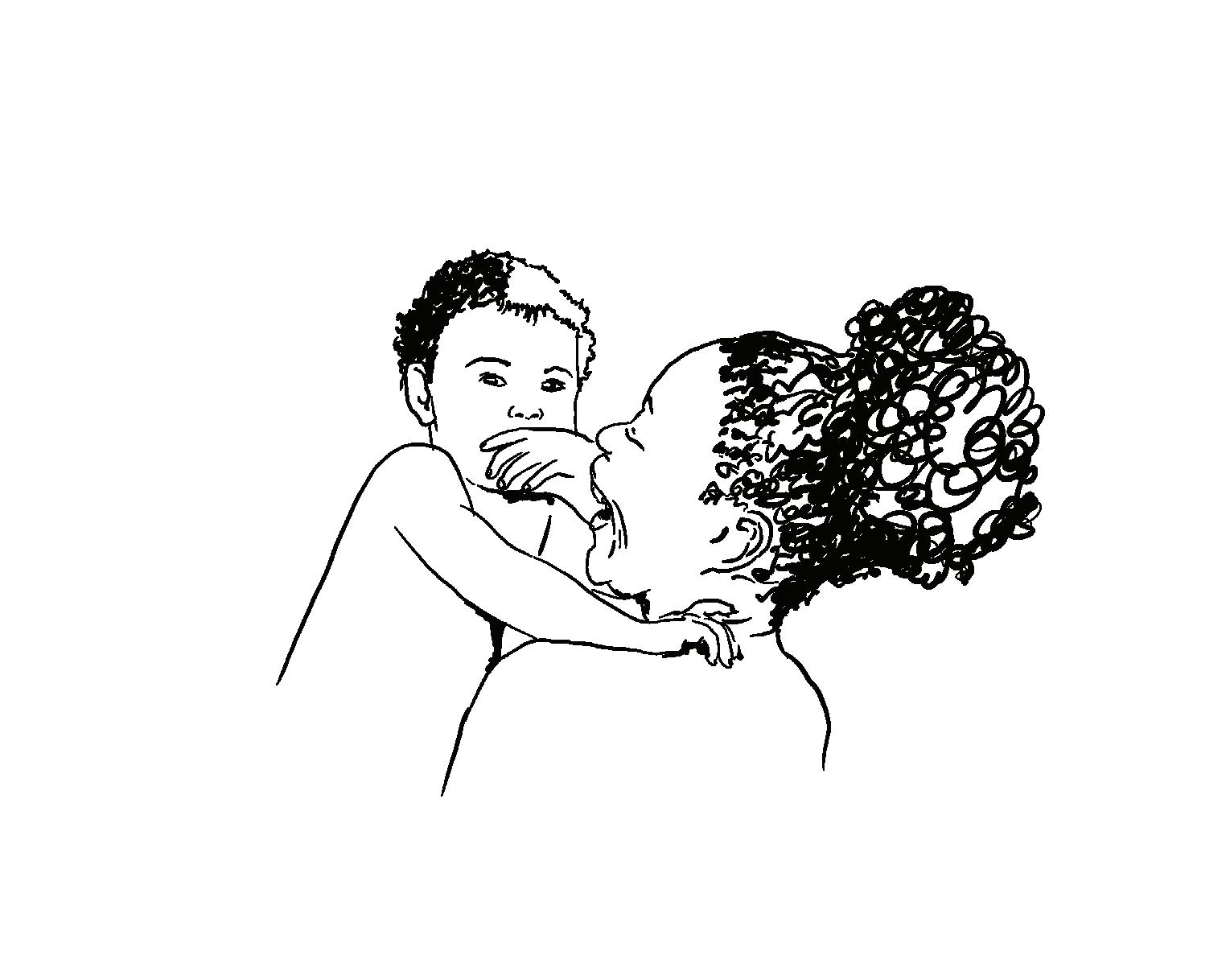

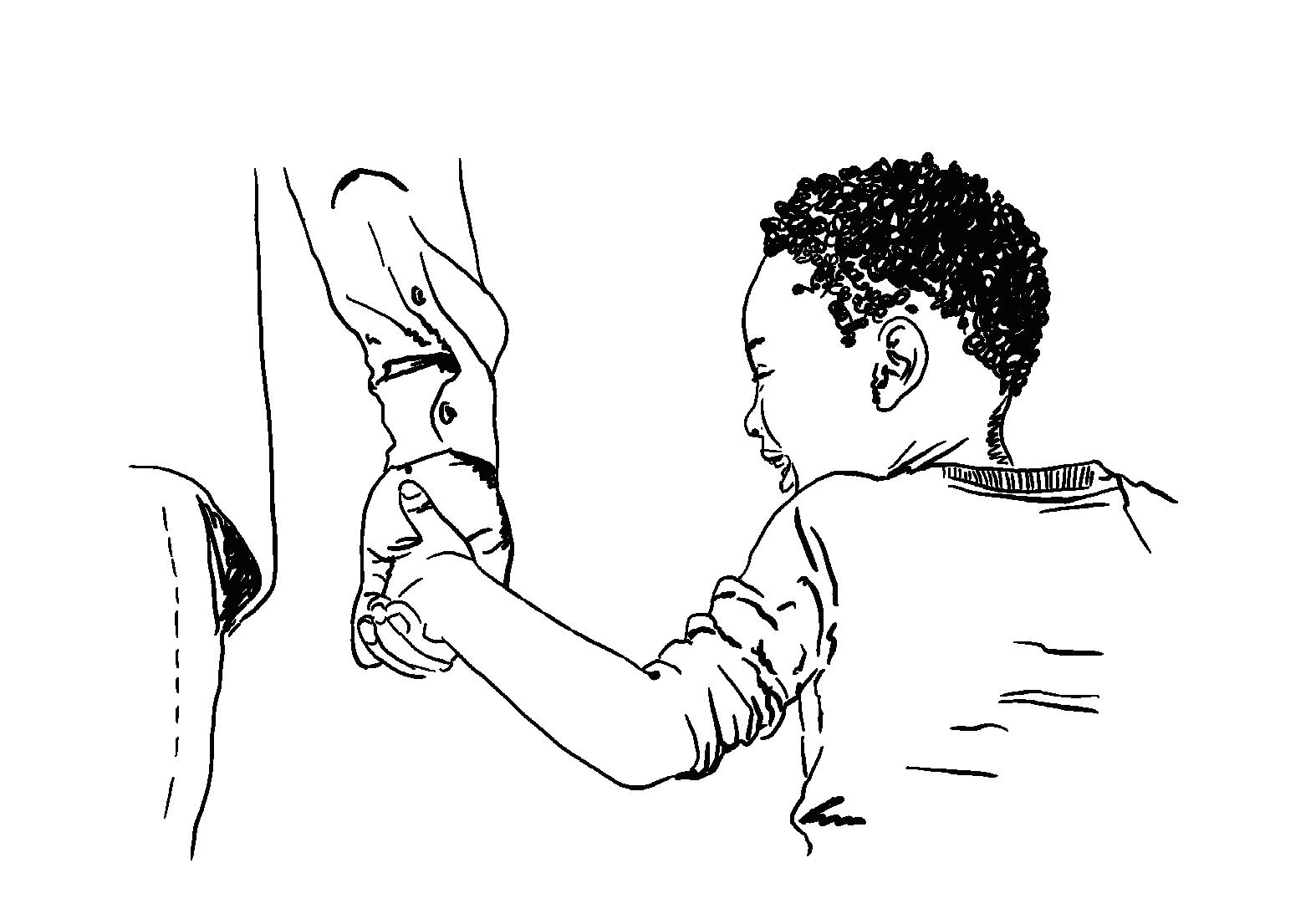

Early learning, especially during the first two years of life, is greatly influenced by the home environment. It's crucial to provide support for parents and other caregivers during these early years to improve care and education in the home, particularly in households with vulnerable members.25 Working parents also need access to safe and nurturing childcare services.26

Participation in early learning programs (ELPs), such as preschools or ECD centres, is highly recommended to provide children aged three and older with structured learning opportunities that support their development.27 In 2024, amid rising living costs, the ECD subsidy remained fixed at R17 per child per day for the sixth consecutive year. This placed significant strain on approximately 11 500 ECD programmes that depend on these subsidies as their primary income.28 The decision not to increase the ECD subsidy reduces its real value to R13 (compared to its original value of R17 in 2019) and may exacerbate the exclusion of the poorest children from quality ECD services.

The Thrive by Five Index found that only 46% of four-yearolds attending an ELP were developmentally on track for their age.29 Children who attend at least two years of highquality early learning programmes (ELPs) are more likely to develop the cognitive, social, and emotional skills needed to successfully navigate the demands of the Foundation Phase curriculum and transition to formal schooling.30

A three-year-old child in the wealthiest quintile is 1.6 times more likely to attend an ELP than their peer in the poorest quintile.31 The quality of early learning at some sites is also of concern because many ELPs lack the necessary resources to deliver effective programmes.

25 Hall K, et al. SAECR 2024.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Ilifa Labantwana. 2024. ECD Budget Review: 2024 Budget. Accessed here: https://ilifalabantwana.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Ilifa-LabantwanaNational-Budget-2024-Review-FINAL.pdf

29 https://thrivebyfive.co.za/

30 Yoshikawa, H, Weiland, C, Brooks-Gunn, J, Burchinal, MR, Espinosa, LM, et al. 2013. Investing in our future: The evidence base on preschool education. Society for Research in Child Development. Accessed here: https://www.fcd-us.org/ assets/2016/04/Evidence-Base-on-Preschool-Education-FINAL. pdf.

31 Hall K, et al. SAECR 2024.

of children attended a group learning programme.

REPORTED ATTENDANCE RATES FOR CHILDREN AGED 3-5:

45% attended ECD centres, crèches, and playgroups. 23% attended primary school (typically Grade R).

ENROLMENT RATES 2021/2022:

Enrolment rates of 34% for children aged 3-5 (excluding Grade R).

PERCENTAGE OF CHILDREN ON TRACK IN 2021:

46% of children aged four years could perform ageappropriate learning tasks.

Only 30% were on track for fine motor coordination and visual motor integration.

Over 50% were on track for emergent literacy and language.

ECONOMIC DISPARITIES:

84% of parents whose children attend an ELP say they pay fees.

Only one-third of ELPs receive a government subsidy.

Source: SAECR 2024

Young children need nurturing care to flourish and reach their full potential. Nurturing care is responsive, encourages early learning, and is emotionally supportive.32 The World Health Organisation’s Nurturing Care Framework for ECD is mirrored in South Africa’s National Integrated ECD Policy. These and other relevant frameworks and policies tend to position the child as the main focus of service delivery, perhaps overlooking the crucial role of parents and caregivers.33

A purely child-centred approach ignores the fact that children experience and engage with their environment primarily through their caregivers. Parents and caregivers need an enabling atmosphere of support that prioritises their needs to build a nurturing home environment.34

Perinatal depression and anxiety can have intergenerational effects associated with pre-term birth, low birth weight, malnutrition and suicide. In South Africa, the rate of perinatal depression is approximately 40%, jeopardising the health and wellbeing of the mother, infant and family.35

Women continue to shoulder a significant portion of caregiving responsibilities and the related financial burdens for children. According to the General Household Survey (GHS) 2022, 84% of children under six lived with their biological mothers, while only 38% resided with their biological fathers. Additionally, over 90% of adult recipients of the Child Support Grant were women.36 Despite advancements in women's workforce participation over recent decades, the Covid-19 pandemic reversed many of these gains, resulting in higher unemployment rates and increased childcare responsibilities for women, who have experienced a slower recovery compared to men.37

of children under six lived with their biological mothers.

An estimated 40% of women in South Africa experience perinatal depression.

The CSG is R530 per month in 2024, substantially below the food poverty line

The share of children under six living in food-poor households increased from 33% in 2018 to 39% in 2022.

The share of children under six living in a home where no adults are employed increased from 29% in 2018 to 32% in 2022.

CO-RESIDENCE WITH PARENTS:

32 World Health Organisation, United Nations Children’s Fund, World Bank Group. 2018. Nurturing care for early childhood development: A framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. Geneva: World Health Organisation. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

33 Hall K, et al. SAECR 2024. Page 39

34 Ibid.

35 Marsay C, Manderson L, Subramaney U. 2017. Validation of the Whooley questions for antenatal depression and anxiety among low-income women in urban South Africa. South African Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;23(0), a1013. Accessed here: https://sajp.org.za/index. php/sajp/article/view/1013

36 South Africa Social Security Agency. 2023. Twelfth SASSA statistical report: Social Assistance, March 2023

37 Casale D & Shepherd D. 2021. The gendered effects of the COVID-19 crisis and ongoing lockdown in South Africa: Evidence from NIDS-CRAM Waves 1-5.

Social grants are widely regarded as South Africa’s most successful poverty mitigation strategy. The child support grant is effectively targeted at low-income families, and extensive evidence highlights its positive impacts on children, even though its value remains modest.

Although the CSG uptake among infants has remained stubbornly low compared to children over the age of one, there was some improvement in early uptake during the decade leading up to the Covid-19 pandemic and resultant lockdowns.

A study commissioned by UNICEF estimated that around 2.2 million eligible children were not receiving the grant, with those in the 0-1 and 15-17 age groups disproportionately impacted. Many infants are excluded because of birth registration delays and late enrolment onto the grant.38 For instance, the number of unregistered infants increased from 190 000 in 2019/20 to 255 000 in 2020/2021.39

“The Child Support Grant has received annual increases that have not kept pace with food inflation and [it] is no longer able to cover the minimum cost of feeding and clothing a child … Worryingly, we have seen a real decrease in the grant take-up among infants.”

– Dr Katharine Hall, Children’s Institute at UCT40

statement-sa-early-childhood-review-2024.pdf

were not registered within their first year in 2020/2021.

Reaches over 13 million children monthly, including 4.2 million under six.

Since 2020, the number of infants receiving the CSG has declined.

For the past decade, around 200 000 of the approximately 1.1 million children born each year were not registered within a year of their birth. 54 800 children without birth certificates and 10 600 caregivers without identity documents were accessing social grants in 2023. (This is possible in terms of Regulation 13(1) of the Social Assistance Act, but few

“Harnessing the potential of ECD interventions to ameliorate poverty and inequality, and curb complex societal challenges such as violence, gender discrimination, and child maltreatment is critical for pursuing a just, equal and sustainable society,” explains Associate Professor Wiedaad Slemming, lead editor of the South African Child Gauge 2024, and Director of the Children’s Institute at the University of Cape Town.41

Investing in early childhood is essential to maximise lifelong health and development. The following interventions are recommended by the Child Gauge and SAECR for each component of the Essential Package.

Protecting and nurturing maternal and child health forms the foundation for many critical child development milestones and long-term gains. The SAECR highlights that South Africa has improved child health service coverage, but more efforts are needed for children to thrive. To improve outcomes, we need:

Coordinated service delivery: The primary healthcare system arguably provides the best infrastructure to deliver the majority of the Essential Package components, thanks to its extensive network of clinics and community health workers.42 But doing so calls for both coordinated care delivery and a shift in the system's focus from "survive" to "survive and thrive."

Improved data collection: The District Health Information System (DHIS) tracks numerous health indicators but lacks individual-level data, impacting the ability to assess the quality of care. Improved data collection and monitoring systems are needed for better health outcomes.

Child nutrition in South Africa is in a critical state with food poverty, household food insecurity and an increase in stunting. The CSG alone does not provide sufficient income support for caregivers to meet all their children's needs, address the risks of stunting, and enable them to thrive. The value of the CSG is very low (R530 per month in 2024), and its value has decreased in real terms over time, as annual increases in the grant amount have failed to keep pace with food inflation.

There is an urgent need for comprehensive and multi-sectoral intervention to address malnutrition effectively. We need to:

Increase the CSG: The CSG is considerably below the food poverty line (R760 per month in 2023). This means that it is not enough to feed a child. Restoring the CSG to the food poverty line would be an effective way of improving nutrition for young children because it places money directly in the hands of their caregivers.43

Strengthen nutrition programmes: Now that the Department of Basic Education is responsible for coordinating early childhood development, there is a chance to reduce malnutrition in young children by strengthening the nutrition programmes offered in ELPs. There is no comparable nationally coordinated nutrition programme in ELPs, but the ECD subsidy is intended to facilitate the provision of nutrition to young children who attend these programmes.44

Expand home-based community health services: Monitoring children’s growth can be expanded through community health workers (CHWs) by conducting assessments in children’s homes, reducing the burden on primary healthcare facilities.

Income support for pregnant women: Women of reproductive age need access to good nutrition for a healthy pregnancy and to be able to breastfeed. A maternity support grant (MSG) for pregnant women has been put forward as a feasible and effective intervention that could be implemented within existing social support programmes, to support the nutrition of pregnant women.45 46 The MSG would increase food and income

41 https://ci.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/media/documents/ci_uct_ac_za/533/pressstatement-sa-child-gauge-2024.pdf

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Chersich MF, Luchters S, Blaauw D, Scorgie F, Van den Heever A, Rees H, Peach E, Kharadi S & Fonn S. 2016. Safeguarding maternal and child health in South Africa by starting the Child Support Grant before birth: Design lessons from pregnancy support programmes in 27 countries. South African Medical Journal Vol. 106, No. 12

46 Moolla A, Mdewa W, Erzse A, Hofman K, Thsehla E, Goldstein S, Kohli-Lynch C. 2024. A cost-effectiveness analysis of a South African pregnancy support grant PLOS Glob Public Health. 2024 Feb 8;4(2) .

security during pregnancy and immediately following birth; both of these are critical times for safeguarding maternal nutrition and mental health. Many infants struggle to access the CSG because of birth registration delays and late enrolment onto the grant. This has a significant impact because the most crucial time to address stunting is very early in a child’s life. The delays could be resolved by extending the grant into the prenatal period.47

Make nutritious food affordable: The food affordability crisis is not solely the government’s responsibility. It is a societal challenge that demands immediate collective action from the public, civil society, government, and business. The DG Murray Trust and Grow Great are advocating for the double-discounting of 10 protein-rich foods. The proposal requires government, business and civil society to work together to reduce the price of these nutritious foods.48

Babies are ready to learn from the moment they are born, and parents and caregivers are – and remain – a child’s first and most important teachers. South Africa has made significant strides toward achieving two years of pre-primary education by 2030, with near-universal attendance in Grade R. However, ELPs are not state-run and lack sufficient government support. This inadequate investment in ELPs compromises both access and quality, particularly for children from low-income households.

The SAECR points out that poor outcomes for poor children are not inevitable.49 High-quality programmes can and do significantly improve early learning outcomes for poor children in South Africa.50

Achieving access to quality at scale will require greater investment in material and human resources. Only 23% of all teaching staff at ELPs have completed education beyond secondary school.51 Nine out of 10 practitioners report earnings below the minimum wage, with more than half receiving less than R1 000 monthly.52

47 Hall K. et al. SAECR 2024.

48 DGMT. 2024. Double-discounted list of 10 budget-friendly food items. DG Murray Trust website. Accessed here: https://dgmt.co.za/double-discounted-list-of-10budget-friendly-food-items/

49 Henry J, & Giese S. 2023. The Early Learning Positive Deviance Initiative - Summary report of quantitative and qualitative findings. Cape Town, DataDrive2030. Accessed here: https://datadrive2030.co.za/resources/the-early-learning-positive- devianceinitiative

50 Dawes A, Biersteker L, Girdwood L, Snelling M & Horler J. (2020). The Early Learning Programme Outcomes Study. Technical Report. Claremont, Cape Town: Innovation Edge and Ilifa Labantwana. Accessed here: https://datadrive2030.co.za/resources/ the-early-learning-programme-outcomes-elpo-study/

51 Hall K. et al. SAECR 2024.

52 Department of Basic Education. 2022. Baseline Assessment: Technical Report Department of Basic Education. Pretoria.

To improve early learning outcomes, it is essential to:

First ensure that children are living in a safe environment;

Provide information to develop caregivers’ understanding of how to stimulate early learning at each stage of their child’s development;

Increase the value of the ECD subsidy to improve quality and learning outcomes (an estimated R34 per child per day);

Simplify and speed up the registration process to help more ELPs and children to benefit from the ECD subsidy;

Support the education, training and professionalisation of ECD practitioners and centre managers (including their conditions of service and career paths); and

Monitor and support ELPs to improve quality and child outcomes.53

All children require nurturing care, but parents and caregivers often face challenges beyond their control that hinder their ability to support healthy child development. These challenges include the impact of insufficient resources and support on caregivers' physical and mental health, as well as the disproportionate caregiving burden placed on women.

It is therefore critical to extend our efforts beyond parenting programmes to address the social and structural barriers to nurturing care, by:

Encouraging and supporting men to play an active role in the care of young children;

Providing maternity and parental leave and affordable childcare to allow women to return to work;

Providing income support to lessen stress and meet the costs of raising a child; and

Leveraging community networks and faith-based organisations to help strengthen natural support systems, enabling parents to share experiences and support one another in addressing common challenges.54

53 Slemming W, Biersteker L, Lake L. Invest early to drive national development [Policy brief] Cape Town: Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town. 2024. 54 Ibid.

“To maximise the developmental impacts of the CSG, it is critical to ensure early uptake among infants and continuous access to the grant, especially in the early years.”

To fully maximise the developmental benefits of the CSG, such as improved nutrition and health outcomes, eligible children must receive it from birth. Achieving this will require stronger linkages between health facilities (where 83% of births occur), the Department of Home Affairs, and the South African Social Security Agency.

Government alone cannot address the full scope of the challenges children face, as many of their vulnerabilities stem from conditions within their communities and households. The various places where child development happens – in the home, communities, and health and educational facilities – require a whole-of-society approach. This is why we need to get behind a set of national priorities that will, if fully implemented, fundamentally change the lives of our children and the future of our country. Presently, these priorities are contained in government’s National Strategy to Accelerate Action for Children (NSAAC), a culmination of a year’s worth of work by technical teams and civil society that was coordinated by the Presidency. In his 2025 State of the Nation Address, President Cyril Ramaphosa said that government would adopt the NSAAC to protect the gains that the country has made over the past 30 years in advancing children's rights. We need a high degree of collaboration between government, civil society and the private sector to support the implementation of these national priorities, particularly those that do not fit neatly into a single department’s mandate.

This learning brief drew on the South African Child Gauge 2024 (published by the Children’s Institute UCT), and the Early Childhood Review 2024 (published by the Children’s Institute and Ilifa Labantwana). It was written by Daniella Horwitz and

This is the learning experience of: