ONE OF THE THINGS I FOUND FUNNY

when I first entered the Industrial Design program at ASU was how everyone I met had transferred from somewhere else.

I met art students who wanted to work on something more practical, engineering students who wanted to be more creative, business students who wanted to be closer to the action, and psychology students who wanted to apply their knowledge. The great thing about Industrial Design is that it is broad enough of a field to accommodate all of these backgrounds.

There is an overwhelming amount of skill sets to learn and product categories to explore. I entered the program with a large group of engineering transfers; after spending my entire life thinking engineering was the career for me, it only took one year of Mechanical Engineering classes for me to realize it wasn’t what I wanted to do. I had a passion for making things and a strong desire to solve the world’s problems, but I was met with the reality that engineering school was more about learning theory and looking at spreadsheets than working on real-world project projects. Industrial Design was my way out of the technical mindset of engineering, a way I could create and help solve problems without pulling my hair out over Calculus. The first year of design school was exhilarating for me, learning how to sketch, build models, and follow the design process was some of the most fun I’ve had as a student. Going into the second year of design school I was excited to hear that on of our first real design projects would be designing a chair! This was my chance to make my mark as a designer and respond to all the amazing chair designs that inspired me growing up.

Easy right?

I didn’t realize then how hard this project would be for me.

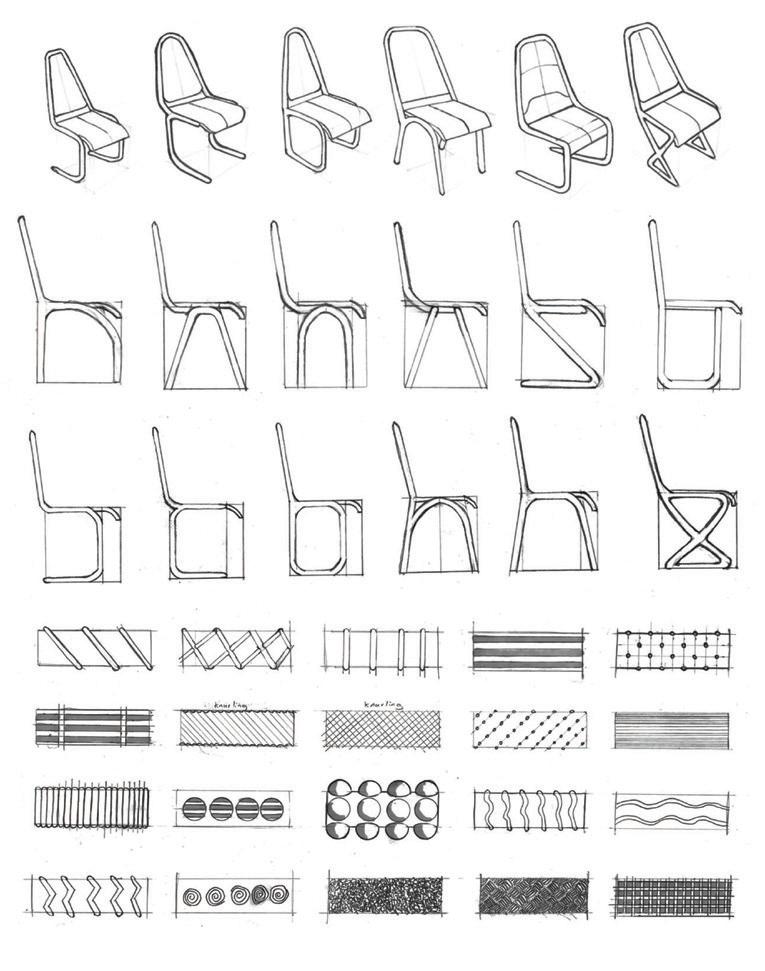

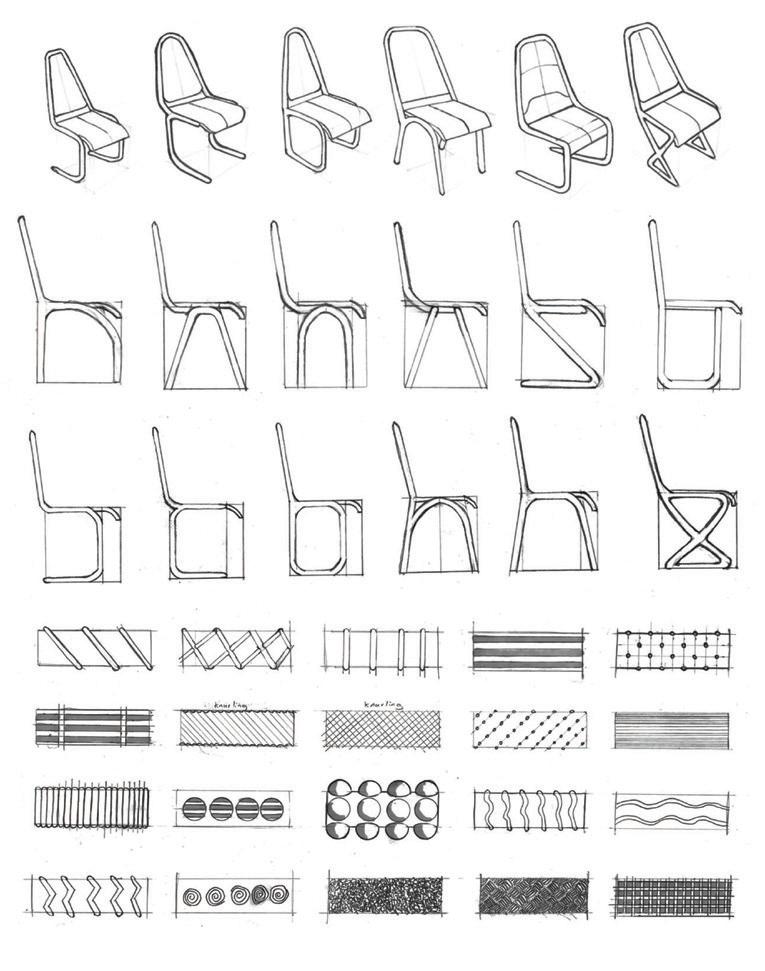

Up to that point, I had spent my entire life training myself to think like an engineer, to work from a problem through to a solution systematically. On the other hand, designing a chair was all about developing form. Ideating creative forms was new territory for me and a hallmark struggle for people who switched from engineering to design. The priority with an engineering project is always function so when it comes to developing forms our brains tend to get locked in on whatever the most obvious solution is. Focusing on the technical aspects of how a product will work means there is less creative exploration, and forms that are unrefined. My designs were no exception, and after weeks of aimlessly drawing some shockingly unoriginal chairs, something needed to change. My problem was the prompt was too vague, with the only guidance being to design a chair, my head was spinning over how many types of chairs were even possible. Did I want a lounge chair? A seat for the dining room table? What about an ergonomic office chair? Maybe a sofa or loveseat? What about a new take on a beanbag?

Even after deciding what kind of chair I wanted to create, how was I supposed to come up with something new and interesting? Without a defined problem to solve, there was no way for my brain to determine whether or not I was moving in the right direction. I was completely lost.

I went searching for a problem to design around. I looked into every niche use case for a chair I could think of, barbershop chairs, market stools, camping chairs, and baby highchairs, when my sister mentioned how her ADHD caused her to struggle to focus while sitting in the uncomfortable, hard plastic chairs standard for elementary schools. My interest was sparked, and remembering the various active chair solutions I remember seeing as a kid like yoga balls and foot swings meant to improve focus, I dove into researching the problem.

I looked into active chair solutions used within classrooms and offices, fidget toys and their effectiveness (to no surprise, fidget spinners helped no one), and even learned some crazy statistics about classroom chairs in general. The core problem I found was the conflict between the needs of the school and the needs of the students. Schools need chairs that are cheap, durable, easy to clean, and stackable for convenient transportation and storage, which all lead to a very rigid chair system. In opposition to this, students want something adjustable to them.

THE MOST SHOCKING THING I LEARNED WAS THAT 70%-80% OF KIDS

WERE THE WRONG SIZE FOR THE CHAIRS THEY WERE FORCED TO SIT IN.

At a time when humans undergo the most variance and growth, we expect them to all fit within a chair that can strictly be bought in just 5 sizes and is distributed depending on class year instead of best fit.

Now this is the kind of thing I could work with, finding the balance between two conflicting sets of needs. It was at that moment I learned about the value of constraints within design.

The current design for school chairs is a direct response to the school’s list of constraints, the form affords the ability for the chairs to stack, the materials allow it to be affordable yet strong, and the lack of cushioning contributes to the durability and makes it easy to clean. All I needed to do was add the needs of students into the mix. The biggest design challenge was how to make the chair adjustable while maintaining its ability to stack. Within chair ergonomics, there are two major points of adjustability. The seat height and seat depth. I decided that the height of the chair was out of my control as it was dependent on the height of the desk, so I focused on seat depth. It was easy enough to make the seat slide back and forth, but if I tried to stack the chairs nothing was stopping the seat from colliding with the chair below it.

My breakthrough was to make the back fold down so that it no longer mattered where the seat was positioned when you stacked it. I also added fidget rollers to the sides of the chair, the important thing I noted in my research was that for fidgets to be useful they have to require direct input. For this reason, I chose to not put bearings on the rollers, the resistance means they cannot be spun like a fidget spinner but can be slowly rotated with your hand. With this final detail, I had my design. The result is something I’m still proud of, it was the first time I felt like a real Industrial Designer.

THE PROJECT HAD STARTED WITH ME FEELING LIKE I WAS INCAPABLE OF BEING CREATIVE, OF COMING UP WITH SOMETHING NEW, BUT BY THE END OF IT, I HAD DONE SOME CREATIVE PROBLEM-SOLVING ON A COMPLEX ISSUE.

My design wasn’t iconic by any means and I still had a long way to go when it came to developing interesting forms but it was something that I could stand by.

A year later, during a welding class, I would get another opportunity to design a chair. This was my chance to improve upon my first attempt and focus on creating a chair with an iconic form, something I felt I had failed to do with my school chair. The excitement was real, I had grown a lot as a designer over the previous year, plus I was going to end up with an actual chair by the end of it! That being said when I started the project I found myself dealing with the same struggle. For the first chair project I relied on the problem statement to guide my creativity, and I had to turn the project into an engineering problem to get anywhere. This time around I wasn’t going to have that luxury.

I entered into a similar cycle of aimlessly sketching chairs over and over, but with deadlines looming, the important thing I realized was that there were other ways to apply constraints to a project. With this chair, the materials and tools available to me acted as a design constraint. I knew I didn’t have the tools available to do tight bends. I knew that I had missed the ordering deadline for materials so I could only use the sheet metal, bar stock, and steel rods that were already readily available to me. I knew I wanted the chair to be a lounge chair for my room so that I could sit and read. These constraints guided my design process and gave me a place to play.

But beyond that, I realized sometimes a constraint could be as simple as taking something and asking “WHAT IF?”

For this chair I was inspired by a bent plywood chair design I saw online with a similar seat called the Roxy Chair. I love the way the seat bent its way into the armrests and I asked myself, what if I tried to make the back really tall? What if it was short instead? What if I put the legs here instead of there? What if I tried to make it all look like one piece of material? Most of these constraints were completely arbitrary, but in placing these hoops for myself my brain was forced to think in creative ways to jump through them and that took the design to interesting places.

The end result was a chair that was super trippy to make, the leg position makes it look both too tall and too short in an intriguing way. It has a retro look to it that feels like something straight out of Star Trek but it is also distinctly me. The weeks of work I put into it lead to an end result that I’m really proud of, and the chair proudly sits in the corner of my room, having quickly been claimed by my cat.

Featuring the Masochist Teapot. We <3 Don Norman.

Materials!

Plastic Adhesion Primer

Sandable Filler Primer

Bondo Glazing & Spot Putty

Sandpaper (220-1000 grit)

Spray Paint

Step 1:

3D Print

3D printing with a lower layer height will produce a higher quality print, which can save time on finishing. Types of printers change quality too.

Step 2: Sandable Filler Primer

To remove layer lines, spray multiple coats of filler primer, sanding in-between. You may need to use plastic adhesion primer to prep your part.

Step 3: Spot Putty Bondo

For areas that need more drastic filling, smear on some Bondo Glazing and Spot Putty with a glove and sand it down.

Step 4: Repeat

Continue to apply Filler Primer and Bondo until the part is smooth. Use increasingly higher grid sandpaper for a nice finish.

Step 5: Spray Paint

Spray multiple thin coats of spray paint in sweeping motions until coated. You can use a clear coat to further protect the paint.

Initial Print

After Filler Primer

After Bondo

Smoothed Print

An Interview With Carlos Terminal conducted by Savaughna Yohannes + Jasmin Lily

When we arrived at Whipsaw’s San Francisco office, Carlos Terminel welcomed us warmly while the team prepared for an evening mixer. We sat on a leather couch, positioned in the center of the open floor office space. The walls were lined with display cases chronicling Whipsaw’s 25 years of product creation and innovation.

Carlos, a graduate of Arizona State University with both a master’s and a bachelor’s degree in industrial design, has had an impressive career (though he is too humble to describe it like that). Prior to his role at Whipsaw, he worked in Google’s Advanced Technology and Projects group.

Over the hour long conversation, Carlos he shared practical insights on building a professional network, meeting portfolio requirements, and navigating the delicate balance of selfcritique. Join us as we explore his journey and the valuable lessons he’s learned along the way. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is the biggest difference between the educational design process and the professional design process?

Hugely different. Schools are limited by professors having to look at the work of 10, 20, 30 students and try and judge them equally. They’re resource constrained and that’s challenging. What I have seen in school is that it is a very linear process. In the beginning of the semester you pick a problem, research that problem and you sketch a few solutions and you pick one solution. Up until here, totally fine. And then you take that solution and you do The 3D model, you do the set of renderings and maybe you’ll make a model and then you present it, and that’s it.

In reality, especially in a professional setting like a design firm, you’re doing a lot of iterations. When you’re exploring concepts early on you’re doing upwards of a dozen concepts in a week just to explore things and then you make 3D models and renderings of each of them, and then you figure out what’s going to achieve the goal and what misses the mark. You continue to iterate on the things that are working. You might go through 15 or 20 iterations of a design before you settle on what will get detailed into DFM.

When you’re in school, there isn’t the bandwidth for that. Most schools don’t prepare students to iterate on their work over and over again.

So that is a big piece of advice particular for personal projects where you have more agency on your time management, do a lot of iterations and show them in your portfolio.

Show all your concepts, even if they’re not all the way developed or detailed, if you’re doing a bunch of form studies, show me that you did a CAD model on all of those different form studies because sketches lie. Show them to me in a grid, in a simple layout.

What should you be delivering if you’re given a week-long timeline? What are the top priorities you would want to see from a passion side project?

Before I answer the question, I do want to address what you just said– you graduate school and you look at your portfolio and you realize it’s not competitive– that is a problem with the curriculum. Not to imply there isn’t agency when you’re in school to push yourself, but the fact that it seems to be a consensus amongst almost all working professionals that if you do all that your instructors have asked you to do and put it in your portfolio and it’s not enough– that is a failure of the curriculum. I’ve got a lot of opinions on curriculum and stuff I would like to change, it’s not the topic but rather the important context for all of this.

Setting yourself a deadline for a project is important. A week can be very aggressive depending on what you have going on.

If you’re doing school full time, oh my god, a week is insane. I would give myself a minimum two weeks, give yourself a little bit more grace. You don’t need to have like 12 projects in your portfolio, 4 or 5 projects is excellent. I don’t want to go through more than that. Even in some cases you can get away with three really good projects, but I would strive for 4 or 5.

It’s all about scope and scale. It’s all about how much you wanna show and how much you wanna do for it. If you give yourself a short timeline, it’ll have to be a simple product, very simple form in order to actually do its due diligence in form exploration. There isn’t a ton of time to do a lot of detailing. 2 weeks is a good timeline if you’re on summer break and don’t have a full class load.

There is something that every project should have. Set of sketches, a couple of different CAD models (3-5 simple form explorations that highlight the chosen direction), a few renderings that showcase the more detailed direction, CMF. For these side projects, the focus more than anything else should be about refining your skills.

Do not pick a heavy research based project if that’s not something you need to work on.

Do a quick bit of research if it’s relevant, then get to form development through sketching, CAD (and iterate on it), then quickly refine and render it. Keep in mind that you’re telling a story– if the intention behind whatever you’re designing is that you can model a really beautiful sculptural piece, show me that really nice sculptural piece that highlights the surfaces and maybe an in context shot that shows it at scale in the room.

If you’re assembling it in a very particular way, show me an exploded view so I get a sense of what the assembly process looks like. They don’t need to be absolutely perfect, just because they have a place in your portfolio now, doesn’t mean they will in 6 months. Also, every project will be different.

This is something you’ll realize eventually, there is no such thing as a single design process. Every design process varies depending on the requirements of the project itself.

As far as curriculum is concerned, what should prospective students be looking for?

You’re not going to be in control of the curriculum. Understand that, accept it, it’s fine. What I mean by that is that you will be beholden to a certain curriculum in order to earn the grades and get your degree. But what you choose to do with your portfolio is completely up to you. You can scrap everything, or include everything if you want, but I probably wouldn’t do that – be sure that your portfolio doesn’t look identical to your classmates.

I wouldn’t focus too much on what the curriculum is going to require of you, I would focus on what it is that you want to include in your portfolio. That could be in the form of deciding the kinds of projects you want to do. Make sure the projects you include in your portfolio reflect the work you want to do.

I think the most important thing is to think through constraints and deadlines and not just think through them, but hold yourself accountable to them.

I say this when it comes to putting together a portfolio that you’re going to send out to somebody– especially when you’re trying to get an internship or a job. That’s normally when I advise people to start doing personal projects, creating and abiding by deadlines, and adding them into your portfolio.

A lot of the personal projects I did when I graduated had to do with proper surfacing with all the right continuity. Projects where the goal was to figure out how to render things really nicely, figuring out how to use Keyshot very effectively.

What does using Keyshot effectively look like?

1. There’s the really pretty, in context shots that are used for marketing we don’t normally use that to sell our clients on a concept.

2. There’s a more streamlined utilitarian use of Keyshot. You’re gonna make it photorealistic but it’s going to live in a void. You’re doing all your renderings from the same camera angle so you can compare and contrast Concept A from Concept B.

3. Then there’s the storytelling aspect of using Keyshot. Showcasing the steps of using the product or how its assembled that give a little more context of what the product is not just seeing it static in one image.

There’s just different goals. So when I’m talking about a portfolio project, it’s more about how do you tell the story of how this one product is gonna be used, what it looks like in the environment, and what scale it is and all of that. I think it’s important when setting up a side project to have an understanding of how you want to develop your skills.

When I say ‘doing renderings effectively,’ I mean making sure that the materials look good and right and proper, getting the lighting to look good and photorealism mapping, labeling things correctly, stuff like that. When I talk about surfacing, I’m talking about how you make all the surfaces flow into each other that feels clean and intentional and not haphazardly.

Understanding what goals you have for the outcome of the project is the big defining north star of how you set it up.

How do you manage self criticism?

I think this is a really hard balance to strike because we are also critical of ourselves. I am guilty of that as well, I view my work very critically and I think it’s within our nature as designers to focus on the problems on what we design.

So first, strive to give yourself a little bit of grace because no design is perfect the first time around.

There is always something that needs to be changed. Understanding that from the get go is very helpful.

Aside from that, I think you have to have a realistic view of where your skills are and where they are relative to other people in the industry/roughly at your level. When we are in school we judge the

because no design is perfect the first time around. There is always something that needs to be changed. Understanding that from the get go is very helpful.

Aside from that, I think you have to have a realistic view of where your skills are and where they are relative to other people in the industry/roughly at your level. When we are in school we judge the quality of your work based on the best work in the class. We think of that as the competition when in reality, that’s not the competition. The real competition is everybody in the industry who is gunning for that job. It’s a much, much bigger scale and that can be very daunting.

How did you start to build that intuition?

A lot of my insights and my experience will come from striving to be the worst musician in the band. Don’t get so bogged down in all of the flaws in your designs. Identify that those are areas that need work and those are areas in yourself that need work.

Start to identify people around you who have those skills and instead of resenting them for it– I’ve fallen into that trap a lot. Start to figure out how you can learn from them because chances are, you have some skills that they could learn from you too. A collaborative and communal exchange of skills and knowledge is incredibly important. Especially in school you have a network of people you can very easily look over their shoulder and pull information from.

Changing your perspective from ‘oh my god my work is awful’ and instead pivoting to ‘this is an area where I need more experience in’ and reaching out to those who you can learn from and giving yourself grace during that perspective shift. I’ll be the first to tell you it’s not easy.

When I graduated from undergrad, my portfolio was not great. I got into grad school and started to do more projects and started to look better. When I was in grad school, a lot of what I did that helped me was mentoring some of my classmates. Some of them didn’t have a background in industrial design at all and at that point I had four years of schooling and an internship and I could at least help guide them when it came to 3D modeling and keyshot. Helping mentor people’s skills there helped further define and refine my skills.

Have you ever contemplated leaving the design world? When have you felt the most doubtful and what willed you to stay?

I think everyone goes through that at some point. I certainly have. There’s a lot of different areas in the design world you can go into so I don’t think I would ever leave it all together.

One thing that you’re not very prepared for in school is that burnout is very real. I know a lot of people who were very passionate about design but got burnt out and decided to leave the industry altogether or go into a more niche part.

Imean it happens, especially when you’re working at a design firm where the work is very demanding and work life balance is a hard thing to strike especially earlier on in your career– it can take over your life in ways that are very unhealthy. There have been times where I have thought, “would my life be easier if my job wasn’t so creatively demanding?” but I think ultimately, like most designers, we find a lot of identity in the work that we do. It’s just a big part of who I am, I don’t think I would want to leave it any time soon.

It’s always the people that keep me here, good creative collaborators are everything in design. There are people who can do good creative work on their own and that’s great, but collaboration is so important and being surrounded by people you enjoy spending time with everyday is huge.

I am very fortunate and privileged to be surrounded by people at Whipsaw who are the best of the best– truly incredible people. There are days that I come to work when I think to myself, ‘how did I even land this?’ because I am surrounded by people who are so incredible at what we do. I think that’s a big part of what has kept me here; being a part of this community.

With your experience at Google and Whipsaw, how do you build a creative community, especially when you’re first starting?

When you’re first starting, I actually feel like it’s easier to do that because you’re so inexperienced and everyone can be a huge resource to you. I remember hearing this really good analogy that’s stuck with me – you should always strive to be the worst player in the band.

You’re good enough to be in the band, you’re playing alongside everybody, but you’re learning from everyone else and you’ll be in a much better position for it. Same thing here, you want to be surrounded by people who are better than you. Not to get caught up in the thought cycle of ‘oh everyone is so much better at this than me’ and instead to see it as an opportunity of growth and to learn.

Take the initiative to see other people as resources, especially when you’re first getting into the industry. Young designers and students would be very surprised to know how willing and able people are to help.

I’ve been in this industry for a number of years and people have begun to reach out to me and when they do that I see it as an opportunity to build bridges and grow a network. It’s not transactional either, it’s very important to not to see it as a way to get on someone’s good side. This is a small industry, people know people or their reputations and it’s certainly important not to burn bridges. Beyond that, your network is a part of your success. Identifying people who can help you grow in the right ways is very important and genuinely befriending them is immensely important.

Identifying people who can help you grow in the right ways is very important and genuinely befriending them is immensely important. “ ”