OMM thanks Omomola Iyabunmi for her collaborative efforts in this issue. And, we give a special thanks to Shayna Bayard, Damon “Mr. Dizzy Fingers” Bennett and Adeyemi Odara for their help in making this issue possible!

Advertising opportunities are available. Please send inquiries to s2ndrising@yahoo.com

C. Chekejai Coley

Tina Marie Coley

Tamara De Silva

Crystal Barrow

Lauren Truitt

Nile-Indigo Coley

Kenya Coley, Ph.D.

Michele Coley-Turner

Jennifer B. Davis

Selena P. Johnson

Deborah Coley Sue Christmas

Creative Director

Issue Advisor, Editor, & Researcher

Researcher

Contributor, Photographer

Graphic Design & Creative Contributor

Creative Contributor

Social Consultant

Social Consultant

Social Consultant

Social Consultant

Contributor & Consultant Socio-Cultural Consultant

Black women have not received the sense of protection that women of other hues have. Who stands up for Black women and girls? Read along to discover who will ultimately have to and how that work can begin.

Culture & Life/Life & Culture

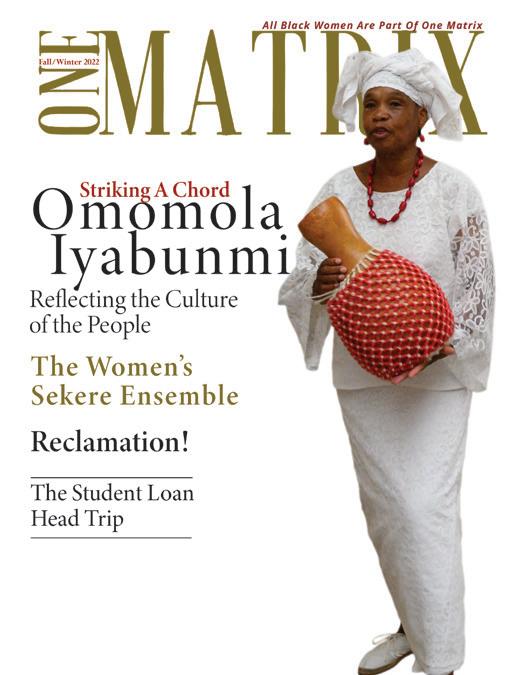

In this interview with Philadelphia-based musician and cultural icon, Omomola Iyabunmi, shares her spiritual and cultural journeys as well as the origin of the Women’s Sekere Ensemble.

Pomegranates are antioxidant-rich fruits to enjoy in the fall. In this article (by Brandpoint Media), we offer ways to enjoy the healthy and delicious source of vitamins C, B-complex as well as minerals such as iron, calcium and potassium. Get your scoop!

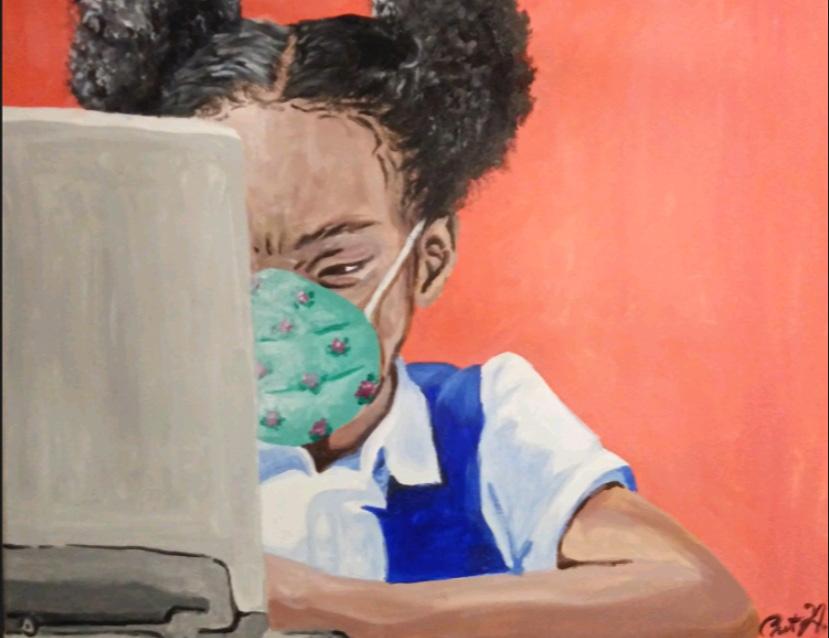

How is student debt created? How does usury play a role in debt (anstress levels) in this country? In this piece, we examine the thoughts around student loan debt and how and why we should change our minds about who is responsible for it.

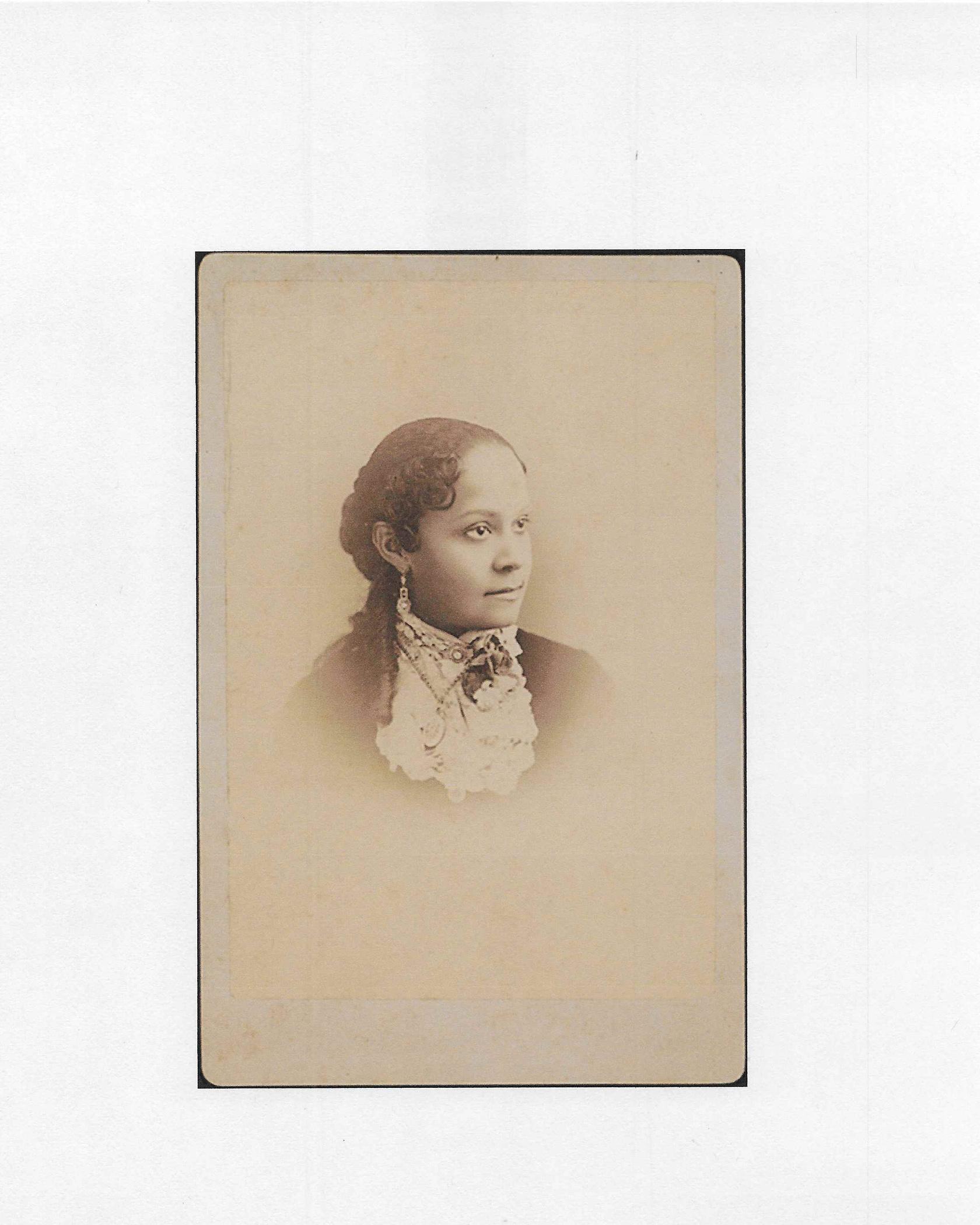

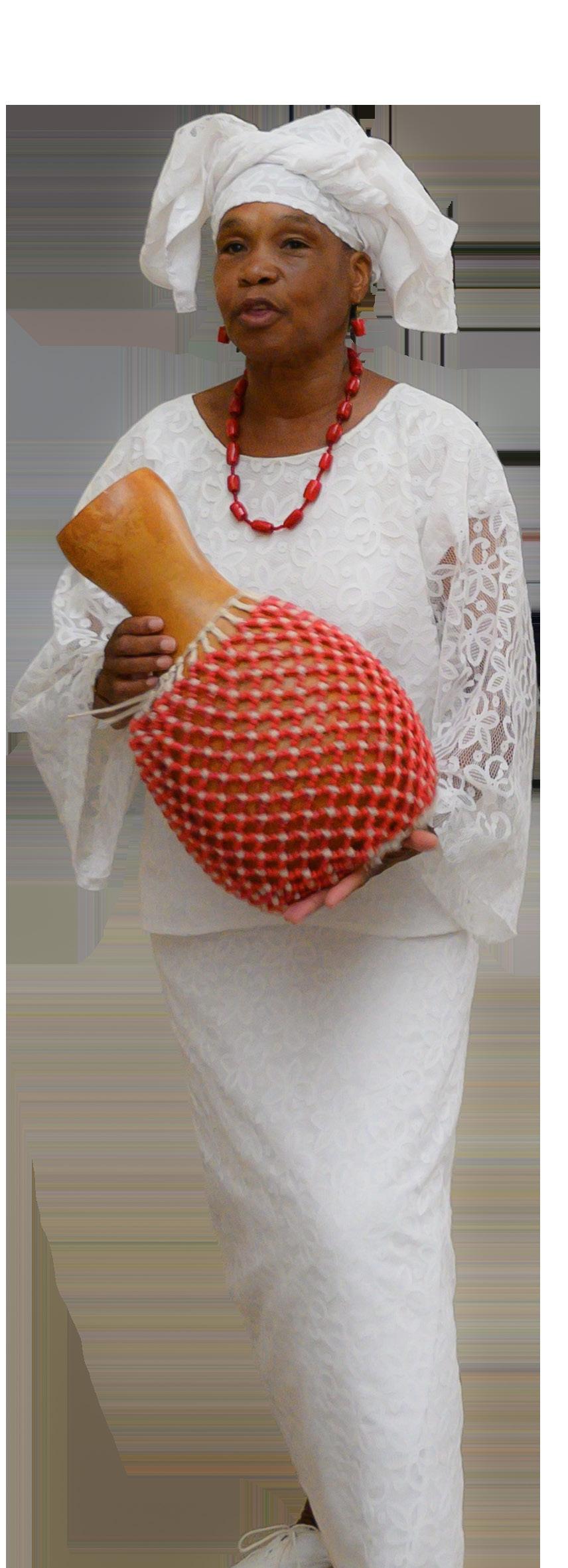

Gracing our cover is Omomola Iyabunmi, musician, cultural educator and director of the Women’s Sekere Ensemble of Philadelphia, Pa.

All images in this issue are public domain or used by expressed permission of the mage owner.

Consider making a donation to OMM. We could use your support to continue to feature Black women who have done remarkable work to keep the culture alive in our communities. OMM thanks you!

Empowerment.

Image courtesy of PCADV. / PCADV.org

Ihave an aunt who often says, “You better save yourself!” in that rhythmic, reverent way that Black woman speak when they speak directly to the soul of someone. No sass. Her words of wisdom informed us of her concern for us. And, her words said, “I’m rooting for you, root for yourself, too.” Besides myself, she echoed this to her daughters, her nieces, my cousins, her six sisters and maybe to her women-friends. It had, and continues to have, a great deal of resonance. I hear it when challenges come and I need to make a choice that will not compromise me or require that I negate myself. We have also begin to pass the message along to our daughters as well.

There is evidence of her statement of truth everywhere for many. She had a ton of challenging experiences in life — as Black women often do. Those experiences range from losing children to health conditions to dealing with an abusive man and from levels of financial struggles to raising children alone. She knew what it was to not have support from others although there were a bunch of us — family members — around. Despite so many of us being in her presence, we never quite knew how to support her. It’s a similar phenomenon with most Black women. We didn’t have much of a consciousness about how to support and believe in each other. The assumption was that Black women were super in some way and could do it all in a couple of leaps if not a single bound. And, apparently Black women could never really feel pain so there was no need for her to heal from anything. Many of us didn’t provide comfort in those times. Alternately, we didn’t receive any in our more challenging and painful moments. We went at it alone and oftentimes, unanchored. Now, we know better and if nothing else, we listen, we hear, and we find ways to be there.

OMM is about finding our way to each other, seeing each other and most importantly recognizing each other as counterparts. After all, we are a part of One Matrix. And, when we see each other, we can begin to pour into each other — filling our cups. It’s one of the best feelings on the planet. It’s the healthy heartbeat that we can all feel. We are our sisters’ keepers especially since no one else has committed to honor us in the way that we see it happening with women in other communities who get support, encouragement, and protection. So, since these things were not bestowed upon us, we must provide for ourselves and, for each other.

Where do we begin to tap into this power? We simply acknowledge each other. Look at each other and say, “hello!” Trust me it will help us to build more compassion for each other and ourselves. And, most importantly, to consider each other. That is our starting point. We grow from there to begin to build better relationships. So the next time you see another Black women — a sista — simply say hello. Once we begin to acknowledge each other, we bring each other (and ourselves) into the present.

Enjoy this issue of OMM. We speak with Omomlala Iyabunmi, the director of the Women’s Sekere Ensemble (WSE) of Philadelphia about her 50 plus years of cultural work and the founding of the WSE — a cultural institution in the city born out of a richness of culture in the late 1980s. Read our article on student loan debt and discover how we can begin to shift our thoughts around them for much needed relief.

Let us now step forward together into a more cohesive sisterhood, a collective. OMM will start the work, “Hey gurl! Hey!” Light for the journey, Chekejai

Omomola Iyabunmi is a Philly-born, Philly-based musician, educator, crafts artist, performer and composer in the West African tradition. She has been performing and teaching sekere for over 35 years. Iyabunmi is the director of the Women’s Sekere Ensemble (WSE), a musical society that she formed in the late 80s. The WSE has since been instrumental (no pun intended, but, maybe) in helping to spread and preserve African diasporic culture and education through music and lecture.

Iyabunmi believes that African music is a social institution that reflects the culture of a people. She has conducted workshops and classes on how to make and play the sekere.

Through her performances, classes, lectures, demonstrations and workshops, Omomola Iyabunmi continues to promote, enhance and preserve African culture.

A beaded guord instrument - found in Nigeria, West Africa

The Sèkèrè is called a xequerê in Brazil. It is called by different names in different countries in Africa. The term, “sèkèrè” is specific to the Yoruba people of Nigeria.

Quick Note(s): The language in this interview — in some ways — follows dialect and language patterns. OMM likes to catch the richness of the way that we speak. We use “sista” instead of “sister” and “brotha” instead of “brother”. “...we women” simply put means “us”.

There is a festival mentioned in the interview called, The Africamericas Festival. Yes, Africa and America is used as one word and title. Creative, right?

OMM: You have done an immense amount of cultural work in Philadelphia — especially in the area of music. And, you have done a lot to bring women into the fold of West African percussion music. Tell us about yourself. Where are you from and, how did you come to do the work that you do in Philly?

OI: I’m from Philadelphia and I am a woman of the 60s. Coming from that era means that I came from a time of enlightenment. It was an era of awakening. We were also rebellious, which happens once you learn the truth. You get excited!

OMM: What was that truth?

OI: We learned to feel good about who we were as descendants from the continent. We came to know that we were good people who should be proud of who we are and where we came from.

OMM: Was there a significant moment or turning point?

OI: I was sitting in Rittenhouse Square — a park in Philadelphia — with some friends and I met a brother named Bamba Ra. He transitioned not too long ago. He came over and he introduced himself to us. At that time, my hair was straight. I think I might have had a little make up on. He was telling us how beautiful we women were. There were some brothas there and Bamba Ra was talking to us about being proud of who we are and where we came from. It just struck a chord. I had never heard anything like that before. I was unaware of anything African being a positive thing. We had a lot of the wrong information about ourselves. We saw Tarzan — a white guy — running around and hurting us. We were asleep. His conversation was an awakening to the fact that we didn’t have self-worth. We lacked that. That night I went home and washed my hair and that’s when I got my natural — hair in its natural state.

OMM: That self-embrace represents a turning point for many Black women. It’s a part of growing in self-love. You have done a lot of transforming in this journey and, the 60s was such a pivotal time. Did you get involved in any of the social or racial justice movements of the time?

OI: I started going to Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC [“snick”]) meetings. They had meetings down near Rittenhouse Square. One of the organizers —

his name was Kwame Ture (Stockely Carmicheal). He was a part of that. I started going to the meetings and I started buying books by Black writers —books like, Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver and Sex and Race by J.A. Rogers. I became empowered as to who I am through that part of the journey.

OMM: How did you come into the cultural space?

OI: My involvement with racial justice and social movements got me on a course. Tony Jenright was a good friend of mine who had moved to Harlem in New York. Harlem seemed to be the Mecca of all kinds of things then. Myself, and a couple of friends —Terry Rice and Jackie Holland — went up there to visit him. He took us on a tour

of Harlem and we ended up at this place called the Yoruba Marketplace. It was like a temple. It was a spiritual center as well as an educational center.

I looked in a window of the marketplace and I saw some brothas and sistas — they were dressed in African clothing. We went in there and spoke to the people. The man who was in charge, his name was Oba Oseijeman Adefunmi. He was a priest in the old spiritual tradition of the Yoruba people. He was saying that we should be proud that we were African and that we had to embrace some ethnic group. We come from a bloodline that has been broken — so we don’t know our bloodlines — but we need to embrace something African and do it thoroughly.

I ended up moving to New York for a few years in the late 60s with a few sistas from Philly and we kept going back to the marketplace and talking to the people, and talking with the Oba. We were learning about the Yoruba –who they are, what they do and why they do it.

OMM: It sounds like it was a profound time of discovery.

OI: We were excited because we were in a revolutionary mode. We were ready! We were revolting, rebelling, and reclaiming the best that we knew how. Back then we were

“Her name was Olabumni Adefumi and she was playing at a religious ceremony. The sound was really beautiful... I heard the melody of the sekere...”

tryna (trying to) get rid of stuff that was a baggage to us — stuff that lied to us about who we are and where we came from and getting rid of the (European) name was a part of it.

OMM: Is that when you received your name?

OI: In that time, Oba guided us. He was helping us find our way back to our source. He gave me my name, “Omomola which means, ‘Child that knows tomorrow’ and Iyabumni which means, ‘God’s gift to the mother’.”

OMM : What drew you to the sekere?

OI: I saw a woman play the sekere during that time. Her name was Olabumni Adefumi and she was playing at a religious ceremony. I loved how it worked. The sound was really beautiful. I heard the melody of the sekere and I really got into it. At ceremonies, I would see her playing. I just loved how it worked. I never got a chance to get her to teach me.

OMM: So, she was your inspiration. Even though she didn’t teach you to play, you encountered this instrument in a spiritual space and it really touched you. You are about 50 years in now, which is a remarkable journey. How did you ultimately come to play it?

OI: It was in the 70s that I really got into the study of the instrument. Each year I learn more. Leonard “Doc” Gibbs was a musician — a percussionist from Philly who was in New York at the time. He also recently transitioned. I met him through some friends. We would sit down and talk to him. When I returned to Philly in the 70s, I looked him up and he began to take time and teach me how to play the sekere with the drums.

I studied with Baba Robert Crowder who was the founder and director of the oldest African diasporic cultural institution in Philadelphia, Kulu Mele. [Kulu Mele means, “speaking for our ancestors.”] Baba Crowder asked me to join them and that was a fantastic experience. Baba Crowder taught me the technique of handling and playing the instrument.

Greg “Peachy” Jarmon, who also played with Kulu Mele, helped in my understanding of how the instrument is supposed to sound along with Baba Crowder.

Baba Ishangi [Razak] — a musician, dancer and a traditionalist in the African system who was from Philly but living in New York, was giving sekere and cultural classes at Ile Ife Center, which was in the Germantown section of Philadelphia. Ile Ife was started by Arthur Hall in Philly. I began taking classes with Baba Ishangi in Philly and in New York.

OMM: How did the Women’s Sekere Ensemble begin?

OI: It was interesting what happened. So, I was in a car accident in 1989 and I was at home recovering. One day Kofi Asante — he’s the one that had the Africaamericans Festival back in the 80s which went for years down Broad

Street — came over to see me. He said when you get better I want you to train ten women to be a part of the African American festival. So, in the next month, I got myself together. He got me a place to teach. It was a wonderful time. Some women had started coming to my class. Before the festival, I called around and sent out the word that I was looking for some women to teach them how to play to sekere for the festival. Ten women came through so that we could participate in the parade. Not long after, we did a performance in Atlantic City. There were five of us who performed and that’s how the Women’s Sekere Ensemble began.

OMM: So, the Women’s Sekere Ensemble, which now has a 30-plus year history, came at a time of your recovery. Do you still continue to do the work?

OI: Yeah, we get some we get some work you know. Things have been you know off because of the pandemic but we’re still working.

OMM: How many women would you say that you have worked with throughout the course of the past three-plus decades?

OI: Maybe eight women.

OMM: What motivates you to continue the work with women? Was there something in that development that said this is the right thing to do?

OI: Well, I love African music and I love the sekere. I want people to hear the beauty of it and I enjoyed what we were able to do. In my mind is, this is African, and I’m so honored that I was able to move in it. And, it just happened that way. It was nothing I’ve planned —like my whole thing about where I am today wasn’t planned.

OMM: What would you say is the greatest gift that you have received from your experience in New York and the embarking on the sekere?

OI: This whole thing is about me reclaiming who I am. All of this is about that. I was already a revolutionary as they call it. Once you become aware, you move towards something. Mine was getting back what was taken. It was culture. It doesn’t mean [just] singing and dancing It means understanding the concept of the African mind. It came my way so I began to do more research about the Yoruba people. We have a whole system. A culture is a whole system. It’s more than just singing and dancing.

OMM: Your journey with the sekere has been very sacred to you and you have flowed with the Spirit.

OI: Yes, I was led. [I had] no idea that I was gonna love the instrument so much and I was gonna get into it. I’m just showing up. I’m just here letting the Spirit guide me.

“It just struck a cord.”

Some of the Past & Current Members

Benita Binta Brown-Danquah. (1994, August). Phil adelphia Folklore Project WORKING-PAPERS #10 AFRICAN DIASPORA MOVEMENT ARTS IN PHILA DELPHIA: A BEGINNING RESOURCE Philadelphia Folklore Project.

De Silva, T. D. S. (2006). Symbols and Rituals: The Socio-Religious Role of the Igbin Drum Family University of Maryland.

African Continuance, The. (1991). Scribe Video Center. https://scribe.org/catalogue/african-continuance (O. Iyabunmi, Bio C. 2006)

Once you become aware, you move towards something. Mine was getting back what was taken. It was culture. ...A culture is a whole system.”

“

(BPT) - From Mesopotamia to the Renaissance to modernday California - artists, civilizations and scientists have had a fascinating love affair with pomegranates. While pomegranates originated in Iran and surrounding countries, 90% of today’s pomegranates in the United States come from California.

In fact, throughout the past 20 years, POM Wonderful has become the world’s largest grower of Wonderful variety pomegranates and the No. 1 supplier of the nation’s fresh pomegranates. Based in Central California, POM Wonderful pomegranates are hand-picked at their peak freshness while in season from October through January.

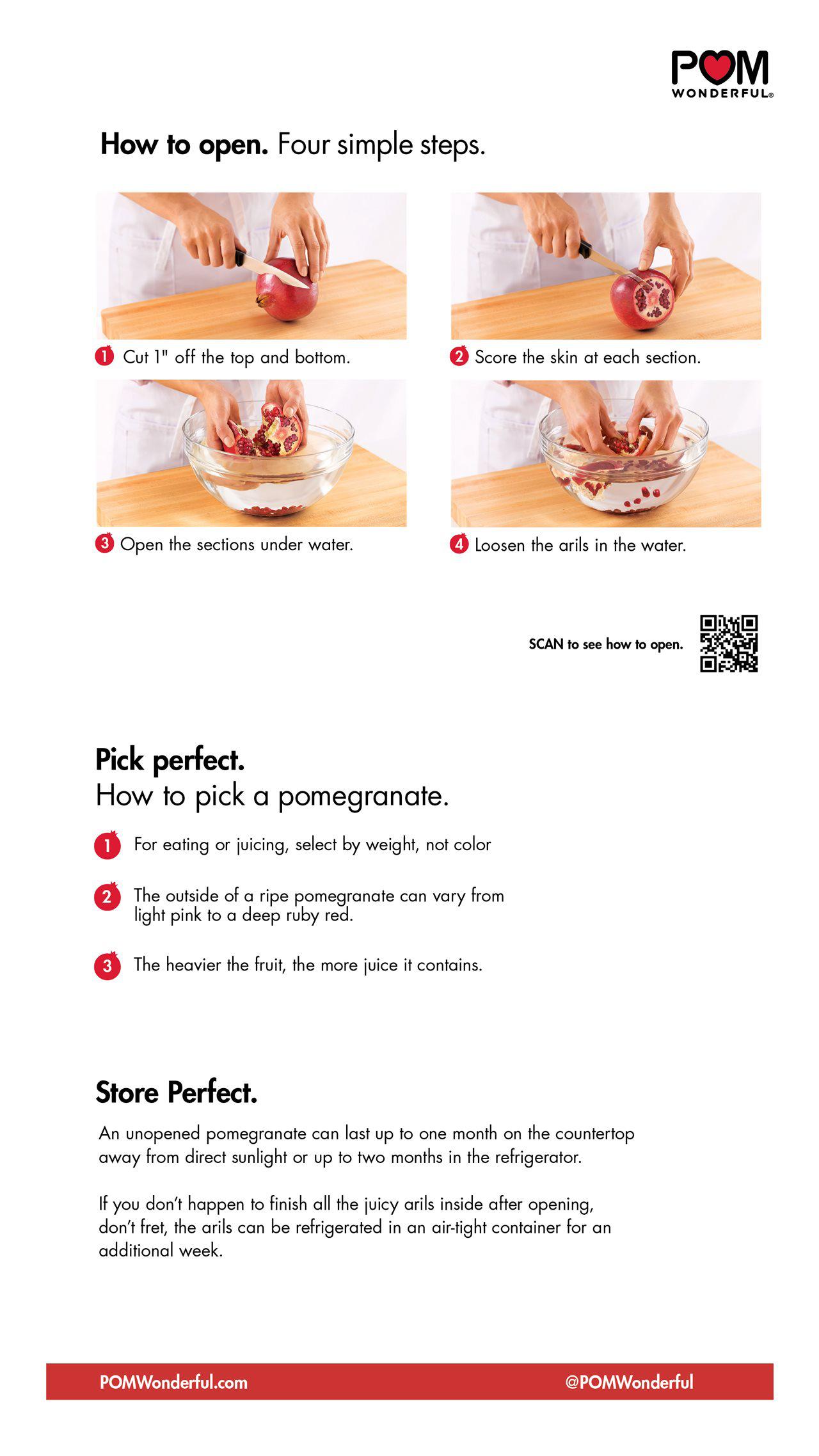

Check out the below tips to help you enjoy the sweet yet tart winter fruit according to POM Wonderful. How to select a pomegranate

When choosing a pomegranate, it is best to select the fruit by weight, not color. The heavier the pomegranate is, the

juicer the arils (seeds) will be. The rind doesn’t have to look perfect to be filled with the most beautiful, juicy arils. The outside of a ripe pomegranate can vary from a deep ruby red to a deep pink.

For those who have never opened a pomegranate before, it may seem intimidating. However, the water method makes opening everyone’s favorite winter fruit simple and messfree with four easy steps. See below for POM Wonderful’s preferred method to open a pomegranate.

Step 1: Cut. Take your pomegranate and cut off the top, about half an inch below the crown.

Step 2: Score. Once you remove the top, you’ll see four to six pomegranate sections divided by a white membrane. Score

the skin along each section.

Step 3: Open. Carefully pull the pomegranate apart in a bowl of water.

Step 4: Loosen. Gently pry the arils loose using your thumbs. The plump, juicy seeds will sink to the bottom. Scoop away everything that floats to the top.

Voila! Now you can enjoy a fresh pomegranate with minimal hassle.

An unopened Wonderful variety pomegranate can last up to one month on the countertop away from direct sunlight or up to two months in the refrigerator. If you don’t happen to finish all the juicy arils inside after opening, don’t fret, the arils can be refrigerated in an airtight container for an additional week!

Sometimes you may want a pomegranate but don’t have time to pick and prepare one properly. In these cases, you can pick up POM Pomegranate Fresh Arils. Conveniently packaged and ready to eat, these arils come from fresh pomegranates and are a good source of fiber, plus, they are known for their antioxidant goodness.

Pick up an 8-ounce package of POM Pomegranate Fresh Arils to elevate your favorite recipes with a brilliant ruby red pop of color and a sweet burst of flavor. Or find a 4-ounce, single-serving package of arils for easy snacking.

Using these tips, you can enjoy the sweet yet tart taste of pomegranates at home or on-the-go by incorporating them into salads, smoothies, yogurt and oatmeal, or a festive garnish for cocktails and mocktails. You can also enjoy this superfruit yearround with POM Wonderful 100% Pomegranate Juice. To find out how you can incorporate pomegranates into your cooking and baking this holiday season, visit POMWonderful.com

Image Credit: Rodnae Productions

Image Credit: Rodnae Productions

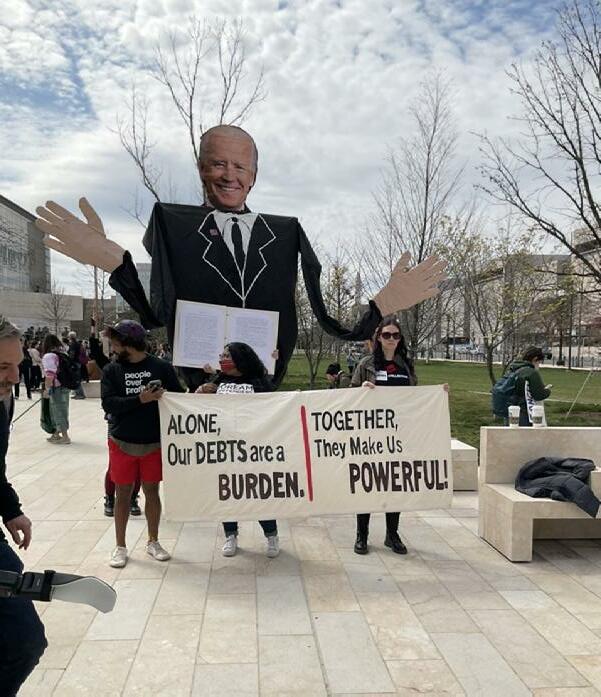

In late August of this year, President Biden announced that a portion of student loans have been canceled for millions of people who borrowed federal money to finance school. It was a relief on some level to many -- a starting point for some with hundreds of thousands in student loan debt. It’s more significant for others with less loan debt. It was a victory for proponents of a full waiver of the burden of student loans for everyone. Yet, there are some who feel that anyone who received inflating student loans should still be accountable for loans that have grown increasingly out-of-control. And, since then, a few states have even gone so far as to take the matter to court to block the waivers. Those people are convinced that student loan debt cancellation will be the end of us all, economically —that the cancellation will cause some sort of financial upheaval for the country. They believe that maybe, if, the people who took out student loans (at age 18 and/or years before working), “would just be more responsible and pay those hundreds of thousands in loans back”, everything would be honky-dory! Business as usual, right? They seldom think about the upheaval that the loan system caused in the first place. And that eliminating student loans would not actually hurt the economy — it would adjust our thinking about it. So, allow me to disabuse certain notions.

To offer a shift in the paradigm (and the paradox that is student loans), students who cannot pay absorbent and outrageous debt is different from being irresponsible. Students have gone to school in hopes of a better life — and, to be financially responsible — only to come out and

be further behind financially than the generation before. It was, however, irresponsible (and greedy) for lenders and the government to lend money to millions of students who are in immediate debt years before they understand it or have an honest repayment plan the moment that they enter school.

Student loans — like all loans — are based on a system of usury. Even though student loans come from taxes, opposed to the creation of money, they operate like every other system of credit. Student loans, again, like all loans, are interest-based/bearing debt — you will repay much more than you ever owed because of interest. For some students, the loans (unsubsidized) will not accrue interest until after school. For some, the (subsidized) loans accrue immediately. For all, the interest accrues

“Birds will stay in flight. Day will follow night.”

daily beginning when school is over whether you graduate with a shiny piece of paper or not. All the debt is compounded (doubled, tripled, quadrupled, and whatever the word for 5 times more is) by interest. Still interested in student loans? I have about 80,000 in loans. According to the interest, I will have to pay back almost 300,000 before all is said and done. Wtf? The truth of the matter is, the –ish is outrageous.

Since many students are not able to pay for school, they, of course, take out loans in hopes of a better financial future. That “better future” is a part of a promise. Most of those students come in with a severe lack of a financial education since comprehensice financial education isn’t a part of most middle or high school curriculums. Very few are grounded enough financially to understand what they are getting into when they take out student loans. Most only know that they are going to school and that someday, when they get a high paying job in their field (eh-hm... let me clear my throat), they will be able to pay back those loans in “easy, low, monthly installments.” So, that never happened — not for most. And to think, we are told that it’s a simple repayment process.

The deep thing about student loans is that they do not have a statute of limitations — like most debt. The loans stay with you -- on your credit report — for as long as it takes to pay them down or until you exit the planet. And, from the time that you leave school, your credit is being impacted. The fallout is tremendous. They impact your credit so the marginalization and, the credit discrimination is real! They impact where you can live, interest rates on cars, lines of credit — even secure credit cards.

The loans even impact where you work despite your educational attainment. In short, they create social economic issues and put people into holes that take quite a bit to get up and out from, if ever.

The toll that loans take on lives is astronomical. They create stress and anxiety for many. So, yeah, it’s the definition of an existential crisis for millions of people in the US; it’s a much more universal crisis that often exists

in feudal systems. It is the perfect storm for stressed people and communities.

The creation of student loan debt equates to the continuation of poverty. Even if my personaal debt does not get passed along to my children, my inability to create a better life is based on credit so, in real time, the next generation is impacted.

Widespread financial healing is a global gain and canceling loan debt is the beginning of a greater economic enlightenment. The earth will not end because debt is eliminated. *“Birds will stay in flight. Day will follow night.” No bank will crumble and no taxpayer would have been robbed as a result. Recent graduates who enter the workforce begin to pay into our tax system immediately. Loan companies — that distribute the funds (from taxes) — expect students to pay the loan debt off. That sounds unreasonable, faulty, and suspect. I digress but not really. Canceling student debt will enrich lives in a significantly more sincere way than attempting to hold people to debt that they can not actually pay. Considering all of the woes that debt creates, canceling them might not just provide relief, it might just save some lives — for generations.

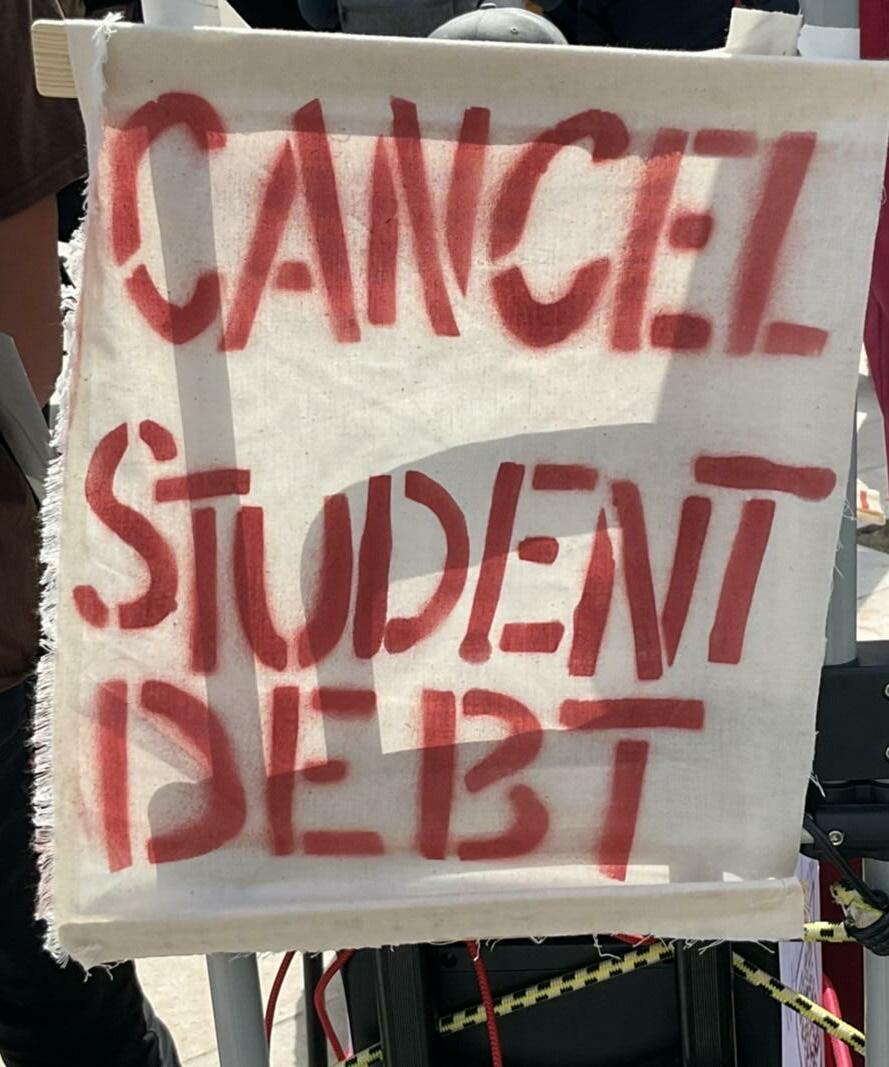

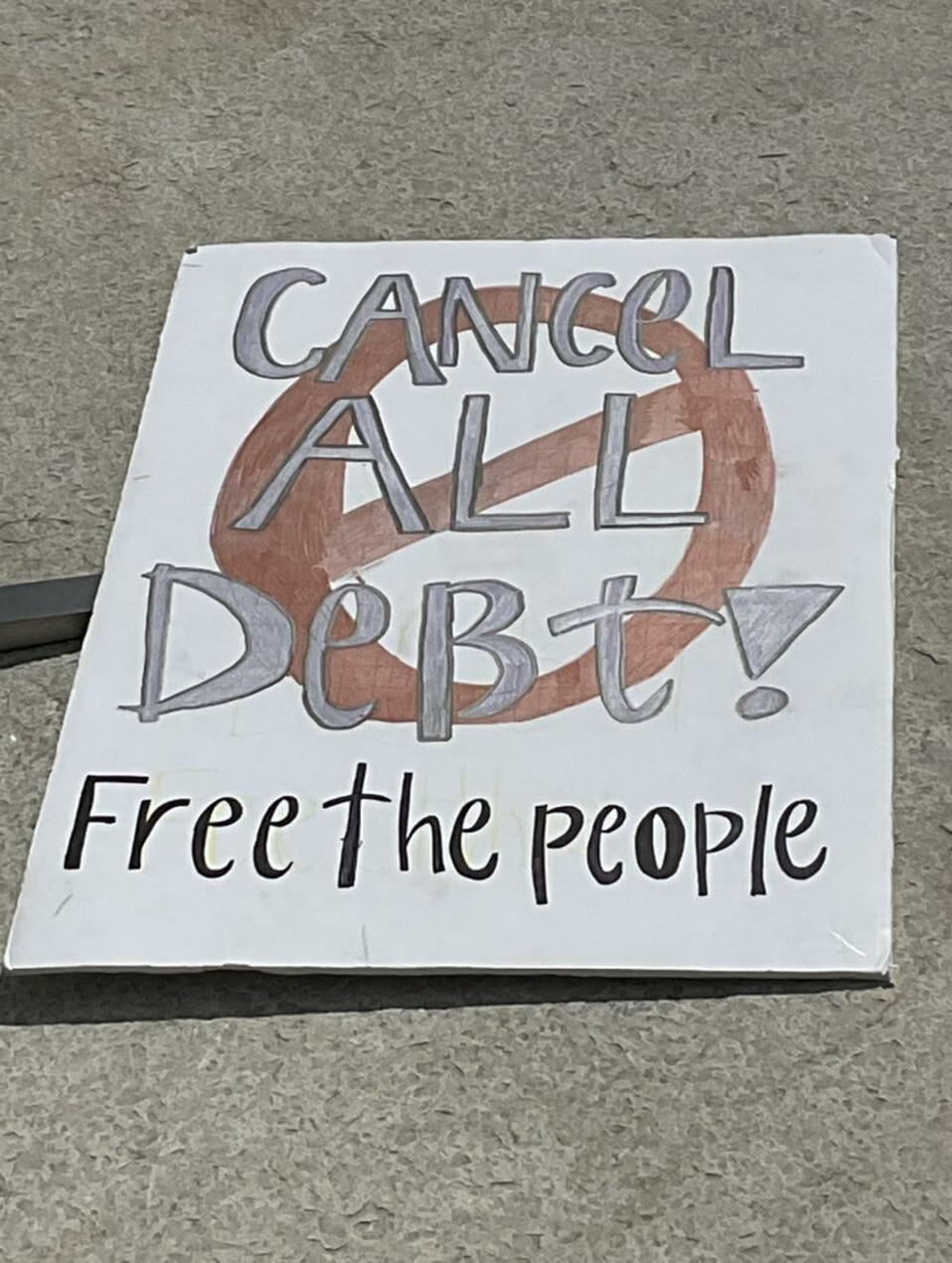

“...eliminating student loans would not actually hurt the economy – it would adjust our thinking about it.”*Rolling Down a Mountainside by The Main Ingredient The images in this article as well as the red fabric pins created by The Debt Collective are from the September 4, 2022 student loan debt protest which was held at the US Department of Education in Washington, DC. Image Credit, C. Chekejai Coley