Design for Neighbourhoods A design agenda for the new government

Quality with quantity: ten ways to design and deliver better neighbourhoods for Britain

Quality with quantity: ten ways to design and deliver better neighbourhoods for Britain

I grew up in Washington, a 1964 new town eight miles from Sunderland. Washington had a vision; bright new homes with central heating, improved insulation standards, and ample space. There were kids everywhere playing from dawn until dusk and brand-new, state-of-the-art schools that were only a 15-minute walk away.

Of course, people are often nostalgic about their childhood and their hometown, but I know that my family, and many others, benefitted from the innovative thinking of the talented designers who created Washington, and the continued stewardship of the Washington Development Corporation.

As the Labour government embarks on the most ambitious national house building agenda for decades, I’m delighted that the Design Council Homes Taskforce has published this inspiring and essential report. In Washington they didn’t just design homes, they designed a neighbourhood. By implementing the policy recommendations of this report, the government could too.

The UK faces a generational opportunity to deliver affordable, sustainable, and high-quality housing while meeting legally binding climate commitments. The Labour government’s ambitious plan to build 1.5 million homes over the next Parliament is the largest housing initiative in decades, requiring an unprecedented scale of development that balances quantity, quality, and environmental responsibility.

However, delivering this ambition is starting from a low base. Too many recent homes fail to meet acceptable standards, with 74% rated as mediocre or poor1, the construction

sector accounting for 62% of UK waste2 and the built environment responsible for 25% of UK greenhouse gas emissions3. Delivering these homes within the 1.5°C climate threshold requires transforming how housing is planned and delivered.

The Design Council convened this Taskforce of industry experts from across the built-environment sector to support the government’s aspirations. Part one of this report presents emergent policy recommendations and propositions aimed at improving the systemic conditions for realising great housing.

62% of UK waste can be accounted to the construction sector

74% of recently built homes are considered mediocre or poor

25% of UK greenhouse gas emissions come from the built environment

This challenge requires a shift towards a whole systems approach and a move away from focusing on the delivery of housing units. Creating great sustainable neighbourhoods demands holistic decisionmaking about infrastructure, public spaces, and land use, ensuring everything works together strategically.

Creating additional homes is equally about refurbishing and repurposing existing buildings to be part of that supply. This optimises using existing infrastructure, maximises resource efficiency and reduces emissions though recognising embedded carbon.

The creation of Mayoral Strategic Neighbourhood Design teams and the establishment of a National Design Review Framework are crucial steps in building regional and national design oversight. They will ensure quality and sustainability remain central to planning and delivery while reducing the risk of poor outcomes and increasing public trust in new developments.

Curating long term value is essential. Investing for the medium to long term in placemaking means creating a master developer role for leading large-scale, highquality housing projects and investing in longer term management and maintenance. Smaller developments should be facilitated by more flexible procurement rules to invite a greater variety of innovative SMEs to develop high quality propositions.

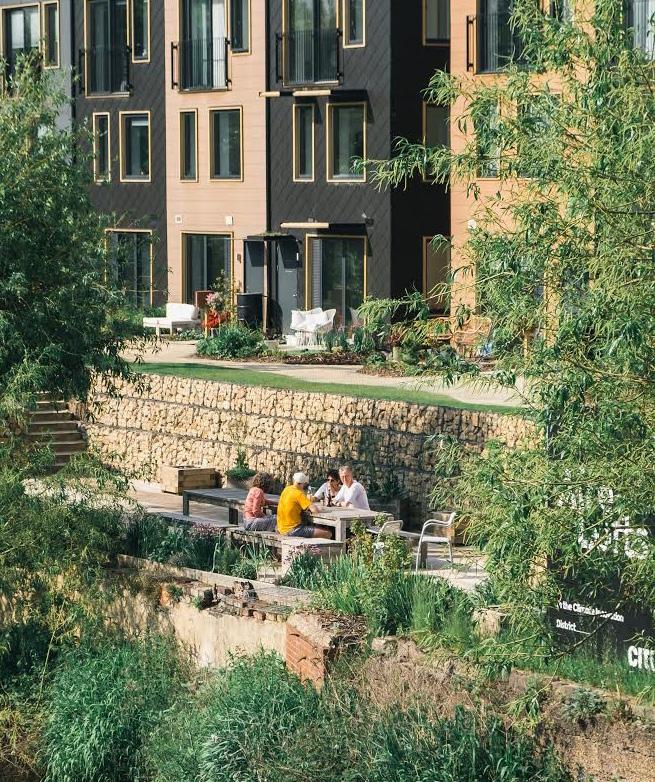

Good neighbourhoods thrive on the quality of their connections so purposely design opportunities to generate these: between neighbours, between generations, with great transport links and living closer to nature.

New Towns can be a beacon for innovative zero carbon development and should be located to reduce car dependency. Planning can be made faster and more efficient, but innovation capability needs to be prioritised across the supply chain. New materials and construction techniques need fast credible certification to satisfy insurers and propel industry uptake.

Part two presents five big questions about the demands and expectations of housing that, if addressed, could ensure that the government’s housing agenda delivers sustainable change for people and planet.

Delivering 1.5 million homes within the 1.5°C climate threshold is a profound challenge that requires a whole systems approach and a shift toward creating sustainable, thriving neighbourhoods.

It requires cross sector collaboration from all stakeholders and already there is a consensus on the importance of systemic capability building and design skills emerging from the multiple contributions to the Taskforce. It is a focus which resonates with the Design Council’s expertise and experience supporting organisations to evolve their effectiveness through using design. By embedding good design thinking and decision-making at every level, the UK can balance quality, sustainability, and resilience within the scale of development.

Delivering 1.5 million homes within the 1.5°C climate threshold is a profound challenge that requires a whole systems approach and a shift toward creating sustainable, thriving neighbourhoods.

1

Adopt a ‘Whole Stock’ housing strategy, maximising the contribution of existing buildings to housing supply through retrofit and refurbishment

▶ Create a percentage target for homes brought back into use as part of overall housing delivery targets.

▶ Invest in refurbishment, sustainable building, and green design skills.

2

Target the upfront ‘embodied’ environmental impacts of construction by setting whole life carbon targets

▶ Implement ‘Part Z’ embodied carbon standards into building regulations.

3

Improve quality outcomes with a National Design Review Framework

▶ Create a National Design Review Framework, extending Design Review across England and Wales.

▶ Mandate Compulsory Design Review for all public sector developments, large private sector developments and all developments built on public land.

4

Enable informed and empowered decision making

▶ Establish Mayoral Strategic Neighbourhood Design teams with capacity and capability to set relevant local design guidance.

5

Agree a Strategic Housing Finance Settlement to accelerate local authority delivery of high-quality, affordable housing projects

▶ Agree a long-term Strategic Housing Finance Settlement, simplifying and strengthening legacy funding mechanisms.

▶ Link good design to public funding, such as through Design Review.

6

Take a ‘Mission-led’ approach to support public sector, SME and community-led development.

▶ Empower public sector-led master developments to spearhead large-scale, high-quality housing projects.

▶ Encourage mission-led procurement, emphasising design quality over cost, for smaller developments.

7

Implement design policies to promote community cohesion and tackle the most remedial neighbourhood design offenders

▶ Tackle lonely corridors and enable outdoor play by legislating the design of shared circulation spaces.

▶ Reduce single use inflexible buildings, requiring developments to accommodate a mix of uses.

▶ Set limits for land that can be used for parking or road space in new developments.

8 Appoint a neighbourhood design advisor

▶ Appoint a Neighbourhood Design Advisor to help co-chair quarterly design and placemaking Steering Boards with the Secretary of State.

9 Develop Zero Carbon New Towns

▶ Assess new town site allocation on ‘triple viability’: social, economic and ecological.

▶ Build social and physical infrastructure before new housing.

▶ Explore ‘strings’ of new neighbourhoods along railways, prioritising connectivity to transport networks.

▶ Create a Zero Carbon New Towns Code to steer the design and construction of all new towns.

▶ Embed senior design leadership in development corporations.

10

Support Construction and Architectural Innovation, removing barriers to low-carbon construction and positioning Britain as a global leader in green innovation

▶ Establish a Regenerative Design and Construction Innovation Centre, prioritising expansion of biobased material innovation.

▶ Support the Building Research Establishment’s functions to enable acceleration of low-carbon material certification.

Launched after the Labour government announced its housing agenda, the Design Council Homes Taskforce is led by key industry figures including dRMM Co-founder and National Infrastructure Commissioner Sadie Morgan OBE, Liverpool City Region Design Champion Paul Monaghan, CBRE Executive Director for Development Louise Wyman, former president of the RIBA Sunand Prasad OBE, Chair of the UCL Bartlett Real Estate Yolande Barnes and others.

In the months since the election, the Taskforce has convened a series of roundtables and site visits to exemplar housing schemes bringing together a broad range of industry experts from across landscape, planning, architecture, engineering, academia, sustainable design, property development and policy making with MPs and elected leaders. The Taskforce used the roundtables to explore diverse policy ideas which could support the delivery of 1.5 million homes within the UK’s 1.5°C climate commitments.

The Taskforce examined how design outcomes and environmental credentials of new homes are influenced by every stage of the UK housing development

and refurbishment system from regulatory frameworks and strategic planning processes to land valuation and procurement. From this process of industry engagement, the Taskforce has identified opportunities for policy intervention across the housing development and refurbishment pipeline where the government could act to enable the delivery of more high quality, well designed, environmentally sound homes.

The report foregrounds four areas of policy reform which the Taskforce recommends could make significant change in delivering sustainable, quality neighbourhoods. The further six propositions are broader areas for reform which emerged through the Taskforce enquiry.

Together the ten opportunities, outlined in Part one, form a strong platform centred on vision-led design for neighbourhoods. The five questions, in Part two, present an invitation for wider engagement of communities from policy makers, researchers and innovative practitioners to address the broader challenges identified through the Taskforce process. The appendix lists all participants who have contributed to developing this report.

Amandeep Singh Kalra, Edward Hobson Louise Wyman, Minnie Moll, Paul Monaghan, Phineas Harper, Sadie Morgan OBE, Sunand Prasad OBE, Yolande Barnes.

Great neighbourhoods do not exist by chance. They are created by numerous deliberate decisions – sometimes taken by many individuals over long periods of time, such as in the evolution of a successful historic town. Sometimes a single client and design team create a major new development whose design will help it quickly to become a great neighbourhood. Whether designed incrementally or in one process, great neighbourhoods are the lifeblood of thriving communities, mixing a variety of people, activities, amenities and public spaces within a characterful and sustainable place. Well-designed neighbourhoods enable and encourage a variety of households to get around cheaply and easily, meeting and forming social bonds in their area. They support a mix of businesses to start, grow and prosper, and enable a diverse cultural life for residents and visitors alike. There is no great housing without great neighbourhoods.

In recent years Britain has suffered from a significant volume of poorly designed new neighbourhoods which are struggling to thrive. 74% of all new UK housing produced since 2007 has been poor or mediocre in quality4 , often badly built5 from high carbon materials6 and car dominated7, failing to promote community cohesion or sustainable lifestyles. Poorly designed homes are a waste of public money. While exceptional housing schemes are realised in the UK, though more frequently

still in comparable European economies, the standard of most mainstream British development is not good enough.

Britain is also experiencing declining neighbourliness driven in part by poor neighbourhood design. Longitudinal studies by the University of Essex found that trust in neighbours dropped from 70% in 2011/12 to 56% in 20208. Research by Laurus Homes indicated a significant decline in the number of people feeling a sense of belonging in their neighbourhoods, dropping from 72% in 2014 to 47% in 20209. Great neighbourhood design practices which can foster successful community interactions exist but are rarely followed under conventional development models.

However, numerous opportunities exist to significantly improve everyday contemporary UK development and refurbishment practices. By learning from the best of European urban development models and from successful UK projects, and by investing in innovation and public sector skills, British housing design could be dramatically improved. With the right combination of policy adjustments across the pipeline of housing design, delivery and maintenance, a much higher proportion of UK homes could meet the government’s ambitions for “high quality, well-designed, and sustainable homes”10 .

Design for neighbourhoods should be the cornerstone of the Government’s housing policy. The design of their constituent neighbourhoods is central to the success or failure of urban developments of all scales. Whether building wholly new neighbourhoods, or strengthening existing ones, design policy should focus on creating better neighbourhoods, where a diverse mix of people can get around easily, live, work, study, travel, play, rest and take part in cultural life in a way that supports wellbeing and is sustainable.

Neighbourhoods are also the scale at which the climate transition needs to happen. Civic Square’s work demonstrates a pathway for a civic-led climate transition that is firmly rooted at the neighbourhood scale11

Landscape architecture practice Planit has worked with Sheffield Council to propose a framework for Living Neighbourhoods12working through the tangible convergence of people, resources, energy and ideas on a neighbourhood scale.

To create climate-resilient places and solve the housing crisis, the government must focus on building high quality neighbourhoods. The industry has shown how to do this—there are highly replicable examples of excellent developments across the UK. We have learnt a lot about the ‘what’ of good design in the last two decades. It is widely understood and enshrined in documents like the National Design Guide. The focus needs to be on the ‘how’ of delivering quality on a mass

scale, ensuring that every one of the 1.5 million homes built is an asset to the nation. The following ten opportunities address the underlying conditions that influence the design decisions shaping the success of neighbourhoods. Driving up design quality and driving down construction emissions is not just about setting higher design standards for homes, but creating the enabling systems – across finance, development practice and procurement – that consistently produce better outcomes.

The focus needs to be on the ‘how’ of delivering quality on a mass scale, ensuring that every one of the 1.5 million homes built is an asset to the nation.

A quarter of UK emissions are attributable to the built environment, this figure rising to around 40% when you include surface transport13. While operational carbon relating to buildings has reduced by 18% since 2018, embodied carbon has only fallen by 4%14 Taking account of this, embodied carbon has become increasingly important to achieving net zero.

In the context of the UK’s legally binding climate commitments, it is critical that building regulations, and related policies, are brought up to date to ensure all new buildings, especially new homes, make a positive contribution to the UK’s sustainability targets.

To address the need for housing and decarbonisation together, the government’s long term housing strategy15 should take a Whole Stock approach to addressing housing need. Bringing good quality, welldesigned homes into use in Britain, whether in the private or public sector, can be achieved most efficiently and sustainably by utilising a combination of new development and refurbishment – upgrading, retrofitting and converting existing buildings alongside adding entirely new stock.

While it is tempting to treat new build and retrofit as separate issues, in practice they are part of the same system. For example, housing associations are re-allocating resources from new development to

upgrading their existing stock to meet safety and sustainability needs16. Likewise, while the government has made positive steps towards abolishing Right to Buy for newly built council homes, the ongoing sell-off of historic council homes grows the need for new social rent homes. As part of a Whole Stock approach new builds, fair allocation of housing stock, and homes upgrades must be planned as a connected system.

A whole stock approach would create a strategy to maximise the contribution of existing buildings alongside creating the new homes that the UK needs.

Historic England calculates that textile mills in Yorkshire and Lancashire alone could create around 42,000 redeveloped homes

1Maximise the contribution of existing buildings to housing supply through a ‘Whole Stock’ Housing Strategy

To address the need for housing and decarbonisation together, the government’s long term housing strategy17 should take a Whole Stock approach to maximise the contribution of upgrading, retrofitting and converting existing buildings alongside creating the new homes that the UK needs.

The UK has a large volume of disused buildings often in desirable locations and public ownership, and hundreds of thousands of homes are long term vacant; neither second homes nor holiday lets18 . Only by bringing empty stock back into use alongside supporting new build can the government deliver the highest possible windfall of habitable homes entering, and reentering, the market within its carbon budget.

Abandoned and under-used commercial buildings should not be wasted - offering valuable opportunities for high-quality and resource-efficient redevelopment. Historic England calculates that textile mills in

Yorkshire and Lancashire alone could create around 42,000 redeveloped homes19. Coastal towns and cities across the North East have clear opportunities for refurbishmentled housing development to contribute a significant number of units to the UK’s overall housing targets within existing urban areas with minimal planning, local opposition or land acquisition obstacles.

With appropriate design quality standards in place, upgrading the nation’s homes is one of the biggest opportunities for the UK to reduce carbon emissions whilst tackling the cost-of-living crisis, energy security and improving workforce skills20. This could see MHCLG and DESNZ pursuing a combined strategy to address the need for new housing, repurposing of underused and empty housing, and upgrading existing housing with long term sustainability standards.

The Taskforce recommends:

A proportion of the government’s 1.5 million homes delivery target should be for existing, but not-in-use buildings which could be brought into use through refurbishment and renewal. The Taskforce recommends setting a percentage target for homes and buildings brought back into use as part of overall housing delivery targets.

A Whole Stock housing strategy, with increased need for retrofit and sustainable construction, requires new ‘frontline’ green skills. Foundational built environment training must evolve, and existing construction workers should be supported to develop their skills in refurbishment, insulation installation, and sustainable building techniques to improve housing quality. Designers also need upskilling to create new and upgraded homes and neighbourhoods. The Design Council has announced an ambition to upskill 1 million designers for the green transition by 203021. Skills England and the Office for Clean Energy should prioritise creating a skills roadmap in collaboration with the sector.

2Target the upfront ‘embodied’ environmental impacts of construction

While decarbonising the electricity grid and phasing out burning of fossil fuels in homes is the path to reducing operational carbon emissions relatively quickly, lowering emissions from embodied carbon requires alternative strategies. The average embodied carbon in a new home is 1200 kgCO2e per square metre of floor area; current industryset good practice is closer to 500kg CO2e per square metre22. But even with this reduction in embodied carbon factored in, building over 300,000 new homes a year, as well as maintaining and refurbishing similar numbers of existing homes within the carbon budget is a big challenge.

Britain already has brilliant industry-led tools

like the LETI guides and the UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard; progressive planning policies to replicate like Westminster City Council’s City Plan23; and practical demonstrators of both individual buildings and masterplans that minimise embodied carbon, from large-scale refurbishment like Park Hill in Sheffield to Citu’s timberframed new housing in Leeds. However, despite these strong precedents, delivering consistently low-carbon homes at scale remains uncommon.

Building regulations also have a critical role to play. Embodied carbon currently falls outside of UK regulation - a risky policy gap that must be addressed.

The Taskforce recommends:

The UK should lead sustainable development practice in setting whole life carbon targets as part of building regulations. Successful pilots in the Netherlands, France and Sweden show this approach is viable. Embodied ‘upfront’ carbon currently falls outside of any building regulations. The ‘part Z’ proposal to regulate embodied carbon is widely backed by industry and would govern the embodied emissions of construction materials and processes24 .

3 Improve quality outcomes with a National Design Review Framework

Independent Design Review processes have proved themselves to be a successful and cost-effective way for local authorities to safeguard better standards of design in developments of all scales. Subjecting proposed designs to scrutiny by independent design experts with local knowledge can improve designs and catch design flaws before they are built, promoting rigorous and efficient design development and more

successful build outcomes for communities. This can be particularly valuable in those areas subject to more intense development pressures, especially on the urban fringe.

Design Review is now well-established as a constructive aid to the planning process, though coverage across England is patchy and performance, representation and impact is inconsistent. All of that can be fixed and it

offers a low-cost method for ensuring that we build a genuine legacy out of 1.5 million homes.

First, there must be equal and consistent access to design review across the country. Many councils still do not benefit from any kind of design review process.

Second, the quality and effectiveness of design reviews must be made consistent. Design review advice should be sought

earlier in the process, from panellists with a breadth of place-based expertise. Clarifying expectations for place quality and sustainability throughout the application process will help deliver more efficient, effective consents.

The Taskforce recommends:

Government should appoint a partner organisation to help to a) co-create a Design Review Framework and b) fully extend Design Review across England and Wales. Where design review is not in place, the partner organisation would support local authorities with training and guidance to recruit and manage independent design review panels for their area, or work with existing design review providers. The partner would ensure all design review panels are working to a common co-created framework with clear outcomes-based evaluation criteria and terms of engagement. Independent panels would be accredited to give developers confidence that the service is high-quality.

The government should set a clear expectation for Design Review for all public sector developments, large private sector developments, all developments that receive public funding and all developments built on public land. There is much to be learnt from the previous Labour government’s ambitious Building Schools for the Future (BSF) programme which required a Design Review ‘pass’ before government funding for development was unlocked. A similar approach should be taken to embed good design and sustainability conditionalities in Homes England and Affordable Housing funding.

Together, the Planning and Infrastructure Bill and Devolution Bill offer an opportunity to improve how urban plan-making works in the UK. This has the potential to enable more high-quality strategic, regionally-informed neighbourhood design. All English regions will have a directly elected mayor under plans being drawn up by the government. Mayors, with a wider regional remit than local authorities, are well placed to support the development of strong strategic plans covering combined authority areas, with local plans focused on managing specific areas of change. They could also build strong specialist teams to produce sub-regional design guides, manage Design Review processes, and sustainability policies.

The success of Public Practice and recent efforts to recruit built environment practitioners by local authorities has proven the potential of strengthening in-house design and development expertise in the public sector. The Design Council Homes Taskforce sees a significant opportunity in mayoral teams to build further public sector expertise, moving authority for strategic, large-scale urban design ‘up’ to combined authority level.

The Taskforce recommends:

Create Strategic Neighbourhood Design teams in every mayoral combined authority with in-house planning powers for elected mayors and sub regional leaders. Mayors should have the power to set relevant design guidance for their area and the power to engage communities through meaningful participatory planning processes. With stronger powers and in-house expertise, mayors will be able to pioneer mission-led master development and procurement, supporting local economies and SMEs, and run streamlined design competitions and Design Reviews for strategic developments.

Building more high-quality, well-designed, sustainable homes requires investment. Today the majority of new homes in England are delivered through what the Competition and Markets Authority calls the “speculative model” of private sector-led housebuilding (over 60% in 2021/22)25. However, the number of homes delivered by the private sector has not exceeded 200,000 homes a

year since 196826. The last time an average of over 350,000 homes were delivered in a year, as much as half were built with direct public sector funding27. Today limited direct delivery capacity in the public sector compounded by high construction costs make house building at scale even more challenging.

The number of homes delivered by the private sector has not exceeded 200,000 homes a year since 1968.

To not just replicate the scale of historic housing delivery but exceed it with welldesigned sustainable homes will require proactive delivery by local authorities underpinned by a comprehensive Strategic Housing Finance Settlement. Without this settlement, housing quantity, design quality and sustainability are all unlikely to be delivered in line with the government’s commitment ambitions. More direct funding in the form of loans and grants to local authorities, in particular to build affordable housing, is most likely to enable the highestquality development.

The Taskforce proposes:

This Settlement should simplify and strengthen legacy funding mechanisms. This includes: increasing the Affordable Homes Programme grant; a long-term social rent settlement; long-term extension of the discounted Public Works Loan Board Housing Revenue Account lending rate; further reforming viability calculations and land value capture; and updating s106 and Community Infrastructure Levy to deliver better public value.

The government should go a step further by linking public funding to good design. For example, Building Schools for the Future in the 2000s required a Design Review ‘pass’ before government funding for development was unlocked. A similar approach should be taken to embed good design and sustainability conditionalities in Homes England and Affordable Housing funding.

Ensuring all new housing development is mission-driven is central to realising a higher quality of design and delivery of successful neighbourhoods. The government should intervene in development processes where it can have a positive impact.

Currently Britain’s development and procurement practices can often result in poor quality outcomes and low value for money. For example, a much smaller proportion of UK housing is delivered by public bodies, SMEs and community-owned agencies28 than in the healthier mixed development markets seen in European economies. In recent years the largest ten housing firms built almost half of

Britain’s new homes29 which limits supply30 and impacts on design and quality31 .

Industry leaders have told us that there are two main ways the government and the public sector can make the biggest difference. First, for large schemes, establishing a public Master Developer vehicle to support regionally-led development corporations to deliver high-quality sustainable neighbourhoods effectively. Second, for smaller schemes, to update procurement practice so that high-quality design is valued appropriately, and SMEs are encouraged and supported to participate.

The Taskforce proposes:

The government should empower Homes England to mobilise its publicly-owned master developer function and use its powers to proactively intervene in the land and development markets. As set out by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Homes England has the potential to intervene as a master developer, though its power is currently constrained32. By working in partnership with local and regional authoritiesalongside private developers - Homes England could drive up the design quality of new neighbourhoods while diversifying delivery approaches and unlocking additionality in supply.

Individual sites with high growth potential and public land ownership (existing or established) should be managed by Mayoral, or Local Public Development Corporations. There are useful precedents in Europe, where models of publicly led development are commonplace. In France, Local Public Development Companies appoint a design team to create a masterplan33. Developers then work with architects to bid for plots, competing on quality not price. The approach is similar in Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands, led by powerful regional governments. The approach also supports delivery on complex sites, like brownfield land which needs remediation and upfront infrastructure investment.

In the UK, such an approach could be led through expanding and improving the role of Mayoral Development Corporations. An explicit purpose of the Master Development Corporations should be to diversify delivery, proactively enabling SME developers and community-led housing providers to deliver housing on suitable sites. Reserved plots could be assigned, or a minimum delivery percentage by SMEs and community-led housing providers could be set for large sites with multiple development plots.

For medium-size sites where a Master Developer role is not constructive, the government should encourage mission-led procurement. By using mission-led procurement, the public sector can seize the critical strategic role that commissioning plays in shaping markets that align with government policy goals.

In Germany, Sweden and other comparable European economies public sector land disposal is procured on quality rather than price. Public landowners set a fixed benchmark price for parcels of land and invite property developers to submit bids, assessing potential purchasers on the quality of their proposals including design, social and environmental stewardship. By fixing a benchmark land price, developers receive more certainty and therefore lower risk while incentivising the best design for a reasonable price. The government should support local authorities in the process of land disposal by issuing template guidance on procurement processes that weigh bids on quality.

Additionally, many of the best housing schemes realised in the UK in recent years, such as the Stirling Prize-winning social housing Goldsmith Street development in Norwich, Barking and Dagenham’s House for Artists, or the multiple phases of the Park Hill Estate refurbishment in Sheffield have been the result of design competitions. However, in the UK, many housing developments employ no competitive process to select designers, resulting in repetitive and poorly designed developments that are often opposed by local residents who resent the addition of generic “boxy” homes in their region. Homes England should encourage a higher proportion of housing developments to use well-run design competitions, working with the sector to define guidelines.

Implement design policies to promote community cohesion and tackle the most remedial neighbourhood design offenders

New UK housing frequently suffers from a known set of specific design failures which together contribute to rising social isolation, loneliness and unsustainable lifestyles. By directly targeting the prevalence of these common “low hanging fruit” bad design practices, the government could significantly improve the design and success of new neighbourhoods.

While this report predominantly focuses on the ‘how’ of delivering design quality at scale, through the Taskforce inquiry we heard inspiring ideas for improving the design quality of our homes. Drawing from this, the following propositions are not an exhaustive list but rather a glimpse of the many options for ensuring our homes and neighbourhoods are designed to a high standard.

The Taskforce proposes:

British newbuild housing often suffers from long windowless corridors which have become standard in many new blocks of flats. These lifeless, inefficient spaces damage community cohesion and promote social isolation by discouraging neighbour interactions. The government could introduce standards to improve the quality of shared circulation areas in blocks of flats to ensure all homes provide decent space for neighbours to stop and chat. Shared circulation areas should meet at least one of the following conditions as a minimum for enabling neighbour interaction: have a daylight factor of at least 1%; be external; have a direct line of sight between front doors and the stair and lift.35

A significant barrier to neighbourhood cohesion is the dramatic decline in children playing outdoors and associated interactions between parents. An important, but often overlooked, contributing factor to declining outdoor play is housing block design which frequently inhibits residents from moving easily from outdoors to their own home with muddy shoes. The government could introduce expectations that all shared circulation spaces must have washable, external grade floor surfaces to enable more children living in housing blocks to play outside easily.36

Unlike traditional British urbanism which is marked by a mix of uses (such as housing above retail or pubs on domestic street corners) and flexible buildings which can be converted to new uses over time, many contemporary developments predominantly feature inflexible single-use buildings. Inflexible architecture is a significant contributor to the overall emissions of the built environment as buildings that cannot be converted to new uses easily are more likely to be demolished soon after they are completed, wasting the embodied emissions created during their construction. In the Netherlands developers like SOLID are embracing long-life flexible design, creating buildings specified to last for over 100 years which can accommodate a changing mix of uses during their lifespan.

Government could address an overreliance on single-use inflexible buildings by setting a requirement for large developments to include a minimum percentage of buildings which can accommodate a mix of uses, and a minimum percentage for buildings which can be converted to another use.

The “vision-led” approach to transport, set out in the latest NPPF, encourages planning for positive travel patterns. Excessive traffic infrastructure such as requiring overprovision of car parking spaces for a small development is not just environmentally damaging but also severs neighbourhoods and inhibits the design flexibility and economic viability of schemes.

Research from Create Streets shows how the 7,500 Chippenham urban extension could be redesigned on a denser masterplan using 40% less land, with 39% less car parking and re-allocating the £75m public investment in a new road to public transport, active travel and social infrastructure . Research from UKGBC has also demonstrated the significant upfront embodied carbon savings that can be made by limited road infrastructure.37 Based on Trumpington South, a 750-home scheme, roads, parking and kerbs make up 88% of the masterplan’s total embodied carbon – equivalent to building 70 terrace houses. By reducing parking areas and switching from asphalt to permeable paving on tertiary roads, significant embodied carbon savings could be made allowing more homes to be constructed elsewhere within the same carbon budget38

Government could address the over-provision of road space, for instance by setting a percentage limit on the amount of land in any development which can be used for roads and parking, or by supporting Local Planning Authorities to introduce more flexible minimum parking allowances.

The Design Council Homes Taskforce welcomes the government’s announcement of new “quarterly Steering Boards on design and placemaking” to help ensure relevant professional and practical expertise is at the heart of housing development and

refurbishment. It is essential to the success of these steering boards that they are convened and led by an appointee with strong knowledge and networks across the design sector and vision for 21st century neighbourhood design.

The Taskforce proposes:

Government should appoint a Neighbourhood Design Advisor to help co-chair the quarterly design and placemaking Steering Boards with the Secretary of State.

Creating new neighbourhoods at scale is central to new government policy. New towns, urban extensions, and large-scale brownfield development are all exciting opportunities for innovation and great design which, if delivered well, could create pioneering sustainable neighbourhoods.

Large scale new development also brings risks. The embodied carbon of new construction is significant, with new developments needing not just housing but also transport, industrial, energy, and water infrastructure to support them. While earlier new town creation programmes have led to many successes, there are also examples of new towns that have not been economically self-sustaining,

becoming dormitory towns that fail to support nearby jobs, mixed communities or local cultural life.

The Design Council Homes Taskforce welcomes the creation of the New Towns Taskforce and looks forward to working in concert to create an ambitious design approach and codes for new urban development. It is important that site selection creates the enabling conditions for good neighbourhood design. Poor site selection often cannot be ‘designed out’, dooming a development to fail from day one. Proximity to existing infrastructure, particularly railways as the UK’s main sustainable transport infrastructure, is a key consideration.

The Taskforce proposes:

New town sites could be selected based on their social, economic and ecological viability. The New Towns Taskforce could establish a set of indicators, including proximity to established infrastructure, ecological impacts, projected embodied carbon of new construction, as well as the ability to create 40% affordable housing on each site. This would steer development towards locations most likely to produce successful, prosperous, sustainable communities.

Where new towns have struggled in the past it has often been due to poor development sequencing. For example, in Thamesmead, a new town straddling the London boroughs of Greenwich and Bexley, the decision to erect large quantities of housing years before rail connections were built was a serious error which stymied the success of the town and has contributed to the enormous costs of ongoing regeneration. Where new towns are to be built “from scratch” no new housing should be built before essential amenities, social and physical infrastructure are in place.

Network Rail manages more than 2,500 train stations, some of which are within a short travel distance to the country’s largest towns and cities making them perfect locations for people who want both a rural lifestyle and easy access to all the amenities large cities offer. Architect and urban researcher Russell Curtis has estimated there is potential in England alone for the construction over one million homes within ten minutes walk of rural train stations using less than 1% of the country’s green/grey belt land while delivering good densities of 50 homes per hectare40. The New Towns Taskforce should prioritise developments within ten minutes walk of rural train stations creating strings of connected adjacent new neighbourhoods sharing local social and physical infrastructure while also within reach of larger towns and urban centres.

Developing a master New Towns Code to steer the design and construction of all Britain’s new towns, whether urban extensions or entirely new. In writing this code, the Design Council Homes Taskforce recommends learning from the best examples of existing development frameworks created by industry. Property developers Human Nature have, for example, identified a set of development principles which govern their housebuilding, baking in social, economic and environmental sustainability41 .

A clear lesson to be learned from past new towns in the UK and beyond it is that leadership matters. The most successful new towns and large urban developments here and elsewhere have benefited from strong leaders who are able to hold the many competing pressures on contemporary urban development in balance while retaining the core vision needed to ensure the quality of the overall project is not compromised. Where development corporations are formed to deliver new towns and new urban extensions, government and the New Towns Taskforce should take steps to appoint CEOs with strong design vision. No New Towns should be undertaken without senior design leadership in place at board level to ensure good design is prominent and accountable alongside other issues

British construction was once rightly seen as pioneering, a centre of design innovation, materials R&D, and new construction methods. However, today many contemporary developments in the UK are no longer innovative, still using 20th century design approaches and high carbon construction materials as the default for making new buildings, roads and infrastructure. This reliance on “old tech” in construction makes delivering low carbon development significantly harder and stifles the country’s economic and scientific potential to lead the world in green innovation. There is little incentive for new materials manufacturers to bring innovative lower carbon construction materials to market as the regime of testing, warranties and insurances required to launch

new materials are onerous and prohibitive without greater support for R&D.

To support private and public sector housebuilders to deliver sustainable homes, the government should do more to support low carbon design, construction and material innovation. In particular, the funding of biomaterials - from invention to adoption - is critical.

The Taskforce proposes:

Construction and architectural innovation are currently under-profiled in UKRI investment, despite its importance to the nation. While there are some large construction material producers with R&D functions, much everyday innovation happens on individual schemes by small firms and the public sector. A new, publicly funded Innovation Centre, potentially created as part of the Catapult network, is needed to grow architectural innovation capacity.

An early priority should be the significant expansion of biobased material innovation and production which could drive low carbon housing delivery. Research by Materials Cultures, an agency testing the potential of low carbon construction materials, suggests that supporting a biobased industry in the North East of England and Yorkshire would significantly bolster the regional economy42. Fostering local, independent, applied innovation43 alongside corporate and academic R&D is essential to reviving the UK’s construction sector innovation economy in ways that will deliver real benefits for more people while boosting housing supply.

Britain needs an independent centre for testing and accrediting building products. Without this, barriers to innovation will remain too high for SMEs to develop and launch the low carbon materials and products the construction sector needs to transition away from fossil-fuel dependent development practices. The government should explore options for how existing organisations such as the Building Research Establishment might better ensure that vital new low carbon materials are robustly and efficiently certified. Regional testing hubs could be a source of income for local authorities, promoting the growth of innovation sectors and manufacturing industries, and contributing to the local economy and international export markets. The Design Council Homes Taskforce further supports the Grenfell Tower Inquiry’s recommendation that these functions, alongside others, into a single construction regulator reporting to the Secretary of State44

Investing in the current R&D infrastructure is vital to ensure the industries delivering change can confidently rely on available and newly emerging resources and practices. The ability to bridge research and practice, to synthesise and ensure an accessible and responsive circulation of questions and answers, is a vital area for UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the relevant Research Councils to address.

This liminal space where the questions and answers are as yet unresolved is a further area for innovation and improving the interaction between research and practice. Part two addresses these and highlights where the Taskforce enquiry raised a number of broader socio-economic questions which form an important agenda, though beyond the scope of this work to answer.

Creating 1.5 million genuinely “high-quality, well-designed, sustainable homes”46 in the next five years is a generation-defining mission for the built environment industries. It will require a herculean effort, but it is possible.

Despite the tangible propositions outlined in Part one, the Taskforce enquiry raised many unknowns. While the urgency of delivering more and better housing remains, the government must also plan carefully to ensure the right quantity and kind of housing is delivered, aligning supply and demand over the long term.

To deliver this, the UK may need greater capacity to deliver independent, high-quality, responsive and policy-relevant research, providing a robust evidence base for policy for housing and placemaking. There is a wealth of research activity undertaken but there is no obvious home for those outputs. For instance, there is no dedicated National Housing Commission or Place Quality Commission in contrast with some other priority areas, for example the Climate Change Committee or National Infrastructure Commission.

If such a body existed, it might go beyond assessing the government’s housing delivery,

There is clearly a need for longitudinal thinking, for imagining a roadmap to 2050 aligning housing delivery with demographic, economic and climate change.

supporting the government to scan the horizon and think beyond a parliamentary term.

In the absence of one dedicated body to review the success of UK housing delivery, and the extent to which it is meeting citizens’ and the country’s housing needs, there were a number of questions raised which go to the fundamentals of the government’s housing challenge. Presenting these here is intended to mobilise a wider conversation to address the evidence base for longer-term planning and to outline an emerging strategic research agenda.

1How many new homes are possible to build within the UK’s carbon budget?

2What spare capacity is there in the existing housing stock?

Construction is carbon intensive. Even with the innovations and design improvements proposed in this report, building any development will create significant greenhouse gas emissions. The Design Council Homes Taskforce recommends that the Government commission research answering the question of how many new homes can be delivered within the UK’s carbon budget across various delivery scenarios.

A critical question in delivering more construction while staying within the UK’s climate budget is how many new homes can be delivered without breaking British emissions obligations. This research must map the dependencies between the retrofit of the existing housing stock, new builds and the repurposing of empty buildings according to different decarbonisation scenarios and compare business-as-usual high carbon construction with the delivery potential of shifting to low carbon construction techniques. Building with the most sustainable techniques will mean the UK can maximise its housing delivery, but exactly what the tradeoff between quality of sustainable design and construction vs the total number of homes achievable within Britain’s carbon budget is not yet clear.

Data shows that the UK’s housing stock is used inefficiently. According to the English Housing Survey, about 52% of owneroccupied homes and 39% of all homes in England have at least two spare bedrooms . This surplus amounts to over 20 million underused bedrooms across the UK, far exceeding the number of people experiencing homelessness. But the data paints a complex picture. On the one hand there seems to be a high number of empty homes and bedrooms but many younger people are increasingly living with their parents into their twenties and thirties. Further research could help the government to identify where spare capacity exists, and how it can be unlocked to contribute to overall housing supply.

What kind of housing do we need?

How many repurposable empty homes and buildings are there in the UK? Where are they? What could they contribute to housing need?

What types of homes, at what price points, what tenures, and in what locations does Britain need? As household compositions change with social norms, the typical set of standard newbuild home designs, sizes and tenures do not allow for the full spectrum of diverse UK communities. Considering demographic projections, it is important the government focuses construction where it will most effectively meet housing need. Delivering an oversupply of luxury housing while realising an undersupply of affordable homes will fail to increase overall affordability and connected social benefits.

Many UK councils are also facing financial crises driven by meeting the cost of temporary accommodation on depleted social housing stocks. Research is needed to determine how much social housing is actually needed to enable councils to effectively manage temporary accommodation demands affordably.

Britain has a large number of empty homes and repurposable buildings which, if refurbished sustainably, could provide a significant number of high-quality homes to meet housing demand. However, precise numbers on the scale and geographic spread of the UK’s many vacant homes can vary depending on data sources and definitions of “empty” or “repurposable”. These properties represent a significant potential resource for addressing housing shortages. For example, Shelter’s 10-City Plan proposes the conversion of 10,500 empty homes as a fast, affordable, and sustainable approach to delivering social rent homes . The Taskforce recommends urgent research mapping the quantity, quality and geographic spread of empty properties to accurately assess the contribution retrofit can make to releasing refurbished homes into housing supply.

5What do long-term population changes mean for housebuilding? Should we predict a contraction of demand and over-supply of housing as fertility rates fall?

Long-term population changes, particularly declining fertility rates, an aging population, affordability and migration may significantly shift housing demand in future decades. Determining what types of home Britain should build, and where, to meet these looming demographic changes is a complex challenge dependent on several interacting factors. In many developed countries including the UK, falling fertility rates and aging populations suggest that population growth could slow, plateau, or even decline. This might reduce the overall demand for housing in the long term. However, these trends will be uneven – some areas may continue to see housing demand rise due to internal migration even if national housing demand declines. Detailed demographic modelling is needed to help to build a clearer picture of the likely characteristics of Britain’s future housing demand.

New Towns

15 October 2024, Portcullis House, Westminster.

Thanks to Emily Darlington MP for hosting.

Urban Extensions

8 November 2024, Greenwich Millenium Village.

Thanks to Design District for hosting.

Urban Regeneration

13 November 2024, Park Hill, Sheffield.

Thanks to The Pearl at Park Hill for hosting.

Amy Burbidge. Head of Design and Master Development at Homes England, member of Cambridge Quality Panel, and Design Action Manager for North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit

Andy Roberts. Director of Urban Design for Planit, member of Sheffield Design Panel, member of Cheshire West and Chester Design Review Panel, and Design Council Expert

Anna Rose. Head of Planning Advisory Service and Chair of Public Practice

Annalie Riches. Founding Director of Mikhail Riches, external examiner for Westminster University, and visiting professor for Sheffield University

Astrid Smitham. Founding Director of Apparata, lecturer at Kingston School of Art and guest professor of housing design at TU Vienna University

Becci Taylor. Director of ARUP, Homes and Housing Advisory Board Member for the Connected Places Catapult, and Design Council Expert

Charlie Edmonds. Neighbourhood Transitions Co-lead for Civic Square, lecturer for London School of Architecture, and Co-founder of Future Architects Front

Chris Vince. Member of Parliament for Harlow

Claire Bennie. Director of Municipal, Mayor of London Design Advocate, Chair of Design Advisory Group for Enfield Council’s Meridian Water Scheme, panel member for Design South East including Chair of Brighton and Hove DesignPLACE Panel and Kingston Placemaking Panel

David Bickle. Creative Director of Hawkins\ Brown, Trustee for S1 Artspace, and Chair of Tannery Arts Ltd Board of Trustees

David Rudlin. Urban Design Director at BDP, principal author of the National Model Design Code, and columnist for Building Design Magazine

Deb Upadhyaya. Director of AtkinsRéalis, Board Director for the Academy of Urbanism, external examiner for Manchester School of Architecture, panel member for Sheffield City Council and Greater Cambridge Design Panels, fellow of Royal Society of the Arts, Committee Member for Urban Land Institute, and Design Council Expert

Deborah Nagan. Director of Deb Nagan Studio, Mayor of London Design Advocate, Trustee of the Landscape Institute, Editorial Board Member for Unlock Net Zero, and Design Council Expert

Emily Darlington. Member of Parliament for Milton Keynes

Farshid Moussavi OBE. Founding Director of Farshid Moussavi Architects, Mayor of London Design Advocate, Professor for Harvard Graduate School of Design, Professor of Architecture for Royal Academy of Arts, Trustee for Norman Foster Foundation London, and Trustee for New Architecture Writers,

George Clarke. Founder of Amazing Productions, Television Presenter for Channel 4, visiting lecturer at Nottingham University, Founder of Ministry of Building Innovation and Education, Patron of Civic Trust Awards, Ambassador for Shelter, Building Community Ambassador for the Princes Foundation,

Gideon Amos OBE. Member of Parliament for Taunton and Wellington

Graham Thomas. Head of Planning and Sustainable Development at Essex County Council and Chair of Essex Planning Officers Association

Hanif Kara OBE. Design Director and CoFounder of AKT II, Professor at Harvard Graduate Design School, Board Member for the Zaha Hadid Foundation, Advisor for the Aga Khan Development Network, Panel Member for the National Infrastructure Commission Design Group, and Design Council Ambassador.

Holly Lewis. Co-founding Partner of We Made That, Mayor of London Design Advocate, Town Architect for the London Borough of Hackney, Chair of Croydon Design Review Panel, member of Thanet Design Review Panel, external examiner for the Bartlett School of Architecture, and Design Council Expert

James Binning. Co-Founder of Assemble, visiting professor at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, and Board Member for Collective Act

Jonathan Smales. Executive Chairman of Human Nature

Jonathan Wilson. Managing Director of Citu, and Trustee for Tiger 11 Development Trust

Jonathan Falkingham MBE. Founding Director of Urban Splash, Founding Director of shedkm, and Design Council Ambassador

Julie Godefroy. Head of Net Zero at the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers and Sustainability Consultant.

Kathryn Firth. Director of Cities Planning and Design for ARUP, Co-chair of the UK Infrastructure & Urban Development Council for the Urban Land Institute, Professor at Harvard Graduate School of Design, Chair

of Ealing Design Review Panel, and Design Council Expert

Leanne Cloudsdale. Founder of Concrete Communities and resident of Park Hill, Sheffield

Luke Tozer. Founding Director of Pitman Tozer Architects and Founder of Architects Action for Affordable Housing

Mark Latham. Regeneration Director at Urban Splash

Matt Hawkins. Chief Executive of Knight Dragon

Nick Raynsford. member of the New Towns Taskforce, former Member of Parliament and Minister of State

Oliver Coppard. Mayor of South Yorkshire

Paul Monaghan. Executive Director of AHMM, Design Champion for Liverpool City Region, visiting professor at the Bartlett School of Architecture and Sheffield School of Architecture, Client Design Advisor for the Royal Institute of British Architects, Town architect for the London Borough of Croydon, Design Council Trustee and Ambassador

Peter Barber OBE. Founding Director of Peter Barber Architects, reader and lecturer at the University of Westminster, and Royal Academian

Peter Bill. Freelance author and Journalist

Peter Lamb. Member of Parliament for Crawley

Peter Maxwell. Director of Design for the London Legacy Corporation, member of the National Infrastructure Commission Design Group, Chair of Harlow and Gilston Garden

Town Quality Review Panel, member of HS2 Independent Design Panel, and Design Council Expert

Roger Madelin CBE. Joint Head of Canada Water Development for British Land

Russell Curtis. Founding director of RCKa, Founding Director of Common Home CIC, Chair of Barnet Council Quality Review Panel, member of London Borough of Newham Design Review Panel, and founding member of London Practice Forum

Ruth Lang. Programme lead at the London School of Architecture, Architectural Consultant for StudioARG, and Design Council Expert.

Professor Sadie Morgan OBE. Founding Director of dRMM, founder of Quality of Life Foundation, National Infrastructure Commissioner, Board member for Homes England, Senior Advisor for New London Architecture, Mayor of London’s Design Advocate, Non-Executive Director of the Major Projects Association, Commissioner for the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission, member of the Net Zero Buildings Council, Design Chair of HS2, Professor at the University of Westminster, and Design Council Ambassador

Selina Mason. Director of Masterplanning and Strategic Design for Lendlease, Chair of Havering Design Review Panel, member of National Highways Strategic Design Panel, and Design Council Ambassador

Simeon Shtebunaev. Senior Researcher at Social Life, Founder of Urban Imaginarium, Board member for the Royal Town Planning Institute, Chair of West Midlands Combined Authority Social Infrastructure and Investment Sub-Group, visiting lecturer at Leeds Beckett University, and Design Council Expert

Sowmya Parthasarathy. Director of Integrated City Planning at ARUP, member of New Towns Taskforce, member of London Place Review Group, and Design Council Ambassador

Summer Islam. Founding Director of Material Cultures, associate lecturer at University of the Arts London, and guest lecturer at ETH Zurich,

Sunand Prasad OBE. Principal at Perkins and Will, Chair of UK Green Building Council, Chair of Journal of Architecture Editorial Board, Former President of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and Design Council Ambassador

Tom Copley. Deputy Mayor of London for Housing

Councillor Tom Hunt. Leader of Sheffield City Council

Vicky Spratt. Housing Correspondent for the Independent

Yemi Aladerun. Head of Meridian Water Development for Enfield Council, Board Member for the Quality of Life Foundation, Non-Executive Board Member for Women’s Pioneer Housing, member of Kingston Design Review Panel, and Architects Benevolent Society Ambassador

Yolande Barnes. Chair of the Bartlett Real Estate Institute at UCL, Non-Executive Director of Space Syntax, and Design Council Ambassador

Adam Allnutt. Recruitment Director for Percival and member of Labour Yimby Andrea Charlson. Managing Director of Madaste

Anna Woodeson. Sustainability Director of Buro Happold and Director of Power Up North London

Lord Best OBE. Member of the House of Lords, Chair of Hanover Housing Association, Vice-Chairman of the All Party Parliamentary Group on Urban Development, and Hon Treasurer of the All Party Parliamentary Group on Homelessness and Housing Need

Cat Drew. Chief Design Officer at the Design Council

Charlotte Watson. Senior Policy Advisor at the Royal Institute of British Architects

Chloe Phelps. Chief Executive Officer of Grounded, Steering Group member for Architect’s Action for Affordable Housing, Chair of Thanet Design Review Panel, ViceChair of Camden Design Review Panel and Ebbsfleet Design Forum

Flora Newbigin. Head of Partnerships at the Design Council

Frederick Weissenborn. Programme Lead at the Design Council, guest lecturer at the Bartlett School of Architecture

Hugh Ellis. Director of Policy at the Town and Country Planning Association and Honorary Professor at the University of Belfast

Jay Morton. Director of Bell Phillips Architects, member of Architects Action for Affordable Housing, member of Islington

Design Review Panel, Ealing Design Review Panel and Croydon Design Review Panel

Kirsty Girvan. Policy Advisor for UK Green Building Council

Leanne Tritton. Co-Founder of ING Media, Co-Founder of Don’t Waste Buildings, Chair of the London Society, and Design Council Ambassador

Matt Bell. Strategic Communications Director of Heatherwick Studio

Matt Mahony. Policy and Public Affairs Manager at the Construction Industry Council

Nell Brown. Senior Public Affairs Officer at the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors

Owen Wainhouse. Head of Delivery at the Design Council

Paul Dodd. Director of OUTDesign, Co-chair of Lambeth Design Review Panel, Deputy Chair of Lewisham Design Review Panel, member of Hertfordshire County Council’s Design Review Panel and Design Council Expert

Paul Miner. Head of Policy and Planning for CPRE

Penelope Tollit. Director of Making Places Together, visiting lecturer at UCL, Chairman of BOBMK Urban Design Network, Policy Council Member for the Town and Country Planning Association, and Design Council Expert

Richard Nelson. Chair of Institute of Directors Property and Built Environment Group, Founder and Managing Director of Abyss Global, and Co-Founder of Don’t Waste Buildings

Roland Karthaus. Managing Consultant for Inner Circle Consulting and Associate Professor for Architecture for the University of East London.

Seb Klier. Head of Public Affairs at Shelter

Simon Sturgis. Founder of Targeting Zero

Trevor Macfarlane. Founding Director of Culture Commons

1 Place Alliance (2021), Housing Design Audit for England (https://placealliance.org.uk)

2 Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2024), Official statistics: UK statistics on waste (www.gov.uk)

3 Environmental Audit Committee (2022), Building to net zero: costing carbon in construction (https:// publications.parliament.uk)

4 Place Alliance (2021), Housing Design Audit for England (https://placealliance.org.uk)

5 The Guardian (2023), Cracked tiles, wonky gutters, leaning walls - why are Britain’s new homes so rubbish? (https://www.theguardian.com)

6 UCL Engineering (n.d.), Refurbishment and demolition of housing. Embodied carbon factsheet (https://www.ucl.ac.uk)

7 New Economics Foundation (2024), New housing developments forcing people to rely on cars (https://neweconomics.org)

10 The Labour Party (2024), Change, Labour Party Manifesto 2024 (https://labour.org.uk

13 UKGBC (2021), Net Zero Whole Life Carbon Roadmap (https://ukgbc.org

14 UKGBC (2023), Net Zero Whole Life Carbon Roadmap Progress Report (https://ukgbc.org)

Vicky Payne. Associate at Jas Bhalla Architects, Chair of the Royal Town Planning Institute Urban Design Network, and member of Places Matter Design Review Panel

Will Arnold. Head of Climate Action at the Institute of Structural Engineers and visiting research fellow at the University of Bath

Will Hurst. Managing Editor at The Architects’ Journal and Co-Founder of Don’t Waste

Buildings

15 Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government (2024), Letter from the Housing Minister - Building the homes we need (https://assets. publishing.service.gov.uk)

16 Housing Today (2024), Notting Hill Genesis confirms £90m deficit in overdue financial accounts (https://www.housingtoday.co.uk)

17 Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government (2024), Letter from the Housing Minister - Building the homes we need (https://assets. publishing.service.gov.uk)

18 Action on Empty Homes (n.d.), Empty Homes Data (https://www.actiononemptyhomes.org)

19 Historic England (2024), Heritage Works for Housing (https://historicengland.org.uk

20 UK Green Building Council (2024), Facilitating Retrofit: A comprehensive sectoral analysis (https:// ukgbc.org)

21 Design Council (2024), Design Council to lead a mission to upskill 1 million designers for the green transition (https://www.designcouncil.org.uk)

22 UKGBC (2022), Building the Case for Net Zero: Closing the gap towards net zero new-build homes (https://ukgbc.org)

23 Westminster City Council (2021), City Plan 20192040 (https://www.westminster.gov.uk)

24 Part Z (2024), An industry-proposed amendment to The Building Regulations 2010 (https://part-z.uk

25 Competitions & Markets Authority (2024), Housebuilding market study final report (https://assets. publishing.service.gov.uk)

26 House of Commons Library (2023), Research briefing: Tackling the under supply of housing in England (https://researchbriefings.files.parliament. uk)

27 New Economics Foundation (2024), Building the homes we need (https://neweconomics.org)

28 UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (2023), Why have the volume housebuilders been so profitable? (https://housingevidence.ac.uk)

29 Architecture 00 (2011), A Right to Build (https:// www.architecture00.net)

30 Competitions & Markets Authority (2024), Housebuilding market study final report (https://assets. publishing.service.gov.uk)

31 At a Design Council roundtable held on Tuesday 15 October at Portcullis House, participants discussed how the highly praised Kings Cross development in central London would not have been so successful if the project had been led by a publicly traded company

32 Joseph Roundtree Foundation (2023), The missing piece - the case for a public sector master developer (https://www.jrf.org.uk)

33 At a Design Council roundtable held on Friday 8 November in Greenwich, Farshid Moussavi presented a development model used in France

34 Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (2024), Mission-led procurement and market-shaping: Lessons from Camden Council (https://www.ucl.ac.uk)

35 This rule was originally proposed by Astrid Smithman of architecture studio APPARATA. It is designed primarily for people living in higher-density housing - in particular blocks of flats.

36 This rule was originally proposed by Astrid Smithman of architecture studio APPARATA. It is designed primarily for people living in higher-density housing - in particular blocks of flats.

37 Create Streets and Sustrans (2024), Stepping off the road to nowhere (https://www.createstreets. com)

38 UK Green Building Council (2022), Building the Case for Net Zero: A case study for low carbon residential developments (https://ukgbc.org)

39 Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2024), Written Statement from the Housing Minister November 12 2024, Housing and Design Quality (https://questions-statements. parliament.uk)

40 Russell Curtis (2023), Housing Capacity around Rural Stations (https://ruralstations.russellcurtis. co.uk)

41 Human Nature (https://www.humannature-places. com)

42 Material Cultures (2021), Circular Biobased Construction in the North East and Yorkshire (https:// materialcultures.org)

43 Promising Trouble (2024) What is good innovation if it doesn’t work for everyone? (https://www.promisingtrouble.net)

44 Grenfell Tower Enquiry (2024), Grenfell Tower Enquiry: Phase 2 Report Overview (https://www. grenfelltowerinquiry.org.uk)

45 Student collaborators: Nikola Endres, Anna Hess, Elina Leuba, Annick Bächle, Maximilian Bächli, Manuel Scherrer, Senga Grossmann, Antoine Hansen, Caspar Trueb, Luca Bolfing, Pascal Hiestand, Carla Waeber, Arianna Charbon, Moritz Hahn, Andrej Harnist, Stan Bezencon, Philippe Jenny, Dominik Koch, Anton Krebs, Aurelia Perschel, Giacomo Rossi, Ella Bacchetta, Léna Grossenbacher, Elisa Nadas, Anna Caviezel, Chiara Hergenröder, Jamila Scotoni

46 The Labour Party (2024), Labour Party Manifesto 2024 (https://labour.org.uk)

47 Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (2020), English Housing Survey (https:// assets.publishing.service.gov.uk)

48 Shelter (2024), Home Again: A 10-City Plan to rapidly convert empty homes into social rent homes (https://england.shelter.org.uk)

Phineas Harper and Matilda Agace

With thanks to and Edward Hobson, Flora Newbigin and Josephine Ryan Gill.

The Design Council is the UK’s national strategic advisor for design, championing design and its ability to make life better for all. It is an independent and not for profit organisation incorporated by Royal Charter. It was merged with the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) in 2011. The Design Council uniquely works across all design sectors and delivers programmes with business, government, public bodies and the third sector. The work encompasses thought leadership, tools and resources, showcasing excellence and research to evidence the value of design and influence policy. Its Design for Planet mission was introduced in 2021 to galvanise and support the 1.97 million people who work in the UK’s design economy to help achieve net zero and beyond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-sa/4.0/