Inspired by our heritage, designed for the modern bedroom. The Iconic Collection features floating beds with unparalleled comfort and exclusive fabrics. Handmade in Sweden

There’s a lot of buzz about design for wellbeing in 2025. Commissioned research, panel talks, podcasts, products – so many in the design world are talking about it, selling it or advocating for it. At Design Anthology UK, we think of it simply as human experience framed by the spaces, objects and rituals that help us feel whole. Post-pandemic, we found a renewed connection with others and ourselves. We vowed never to lose it. But of course, life is full of stops and starts, triumphs and tribulations, giving and taking – each one of us has our own journey towards wellbeing. What does wholeness mean to you? What do you need around you to find it?

For me, it means keeping a solid footing in the present. Despite the depressing state of the world, there is simple joy in everyday tasks at home, or meeting friends in stimulating spaces designed to bring people together, underpinned by the expertise of designers and architects who think a lot about what it means to be human. So while there is a fair bit of eye-rolling at the mention of wellbeing and design, I am also hugely encouraged by how many people are grappling with these ideas. Not on the surface – although that’s happening, for sure – but truthfully, in a way that has lasting impact on our lives.

With that said, welcome to our wellbeing issue, written by some brilliant storytellers who are insightful, imaginative and willing to dive below surface level. We’ve stretched the idea of wellbeing waaay beyond wellness and spa spaces, although you’ll still find those here, from healing hospitality design (p38) to a contrast-therapy facility where you can shift between saunas, cold plunges, and party spaces that wouldn’t look out of place in a nightclub (p30).

We explored other facets of wellbeing in our orbit, too: designing for death and remembrance (p34); rewilding land on a grand Yorkshire estate (p60); Ukrainian craft and symbolism that links past to present (p134); a foodproducing social enterprise in North London (p146); ‘design for democracy’ in the American South (p140); homes that make inhabitants feel cared for and connected to the planet (starting on p76); and fashion labels that promote self expression while caring for the hands of the makers (p152).

We hope you find what you need.

Until next time,

Elizabeth Choppin Editor-in-Chief

London Flagship Store

83-85 Wigmore Street

W1U1DL London

london@rimadesio.co.uk

+44 020 74862193

21

September 2025

Subscribe Invest in an annual subscription to receive two issues, anywhere in the world. Visit designanthologyuk.com/ subscribe

Co-publisher & Editor-in-Chief

Elizabeth Choppin elizabeth@designanthologyuk.com

Co-publisher & Business

Development Director

Kerstin Zumstein kerstin@designanthologyuk.com

Art Director

Shazia Chaudhry shazia@designanthologyuk.com

Sub Editor Emily Brooks emily@designanthologyuk.com

Editorial Assistant Ciéra Cree events@designanthologyuk.com

Editorial Concept Design

Frankie Yuen, Blackhill Studio

Words

Charlotte Abrahams, Alia Akkam, Timothy Anscombe-Bell, Jonathan Bell, Holly Black, Emily Brooks, Sujata Burman, Mandi Keighran, Joe Lloyd, Dominic Lutyens, Karine Monié, Riya Patel, Debika Ray, Nicola Leigh Stewart, Henrietta Thompson

Images

Ben Anders, Iwan Baan, Lucy Franks, José Hevia, Henri Kisielewski, Sean Knott, Salva López, Matthew Millman, Luke O’Donovan, Felix Speller, Henry Wolde

Design Anthology UK is published biannually by Astrid Media Ltd hello@astridmedia.co.uk astridmedia.co.uk

Media Sales, Global Elisabetta Gardini elisabetta@designanthologyuk.com

Printer Park Communications Alpine Way London E6 6LA United Kingdom

Reprographics Rhapsody Media 109-123 Clifton Street London EC2A 4LD United Kingdom

Distributors UK newsstand MMS Ltd. Europe / US newsstand Seymour UK / EU complimentary Global Media Hub

designanthologyuk.com hello@designanthologyuk.com instagram.com/designanthology_uk facebook.com/designanthology_uk

Front cover

A villa in Es Cubells, Ibiza, designed by K-Studio. Image by Salva López. See p76

Collections and collaborations of note

28 Read

Delve into a selection of books on design, architecture and interiors

30 Q&A

London architecture practice Cake talks about a hedonistic therapy space

34 Remembrance

How designers are rethinking the universal human experience of grief

38 Wellbeing

Immerse yourself in cutting-edge design that heals mind, body and soul

46 Haptic design

The sensory technology incorporated into Land Rover’s latest Defender

Cake

“We’re fascinated by how different functions can come together”: read an interview with the architects of a social sauna on p30

New design-centric destinations to explore across the globe

The English country house stay redefining luxury – gifting the space and time to reconnect with yourself

Uzbekistan’s layered past and rich culture, from Tashkent to Nukus

A clifftop finca reinvented by K-Studio as a place where time stands still

Minimalist design fosters peace and connection to a magnificent landscape

100 Barcelona

Inclined to impress: an earthy hillside house by Raúl Sánchez Architects 112 London

Layered with texture and tone, a period townhouse reborn as an inviting retreat

124 Diary

The most compelling art and design events for the coming months

134 Ukraine

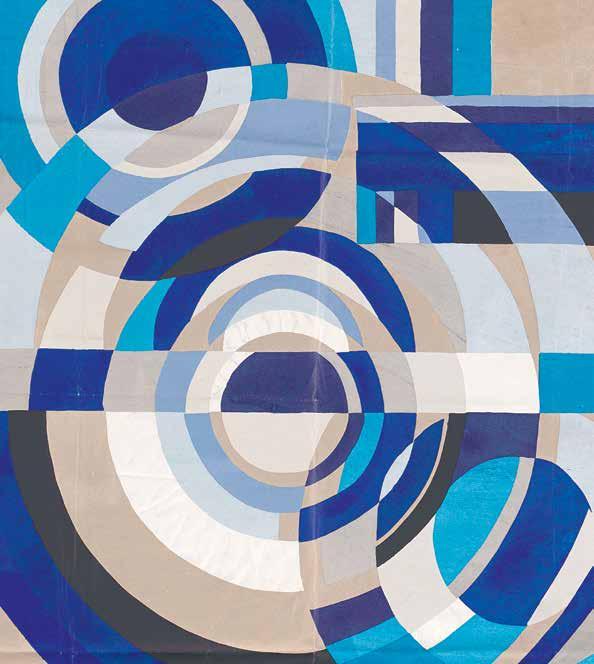

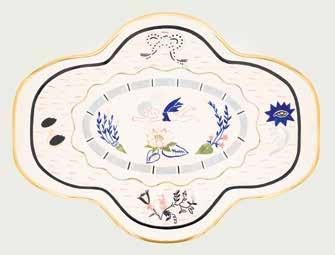

Gunia Project’s ceramics take small steps to reconnect Ukraine with its rich history of decorative arts

Architecture

140 Profile How New Orleans practice Trahan Architects designs for democracy

146 London

Co-designed and built by locals, a foodgrowing centre that’s a blueprint for healthier urban communities

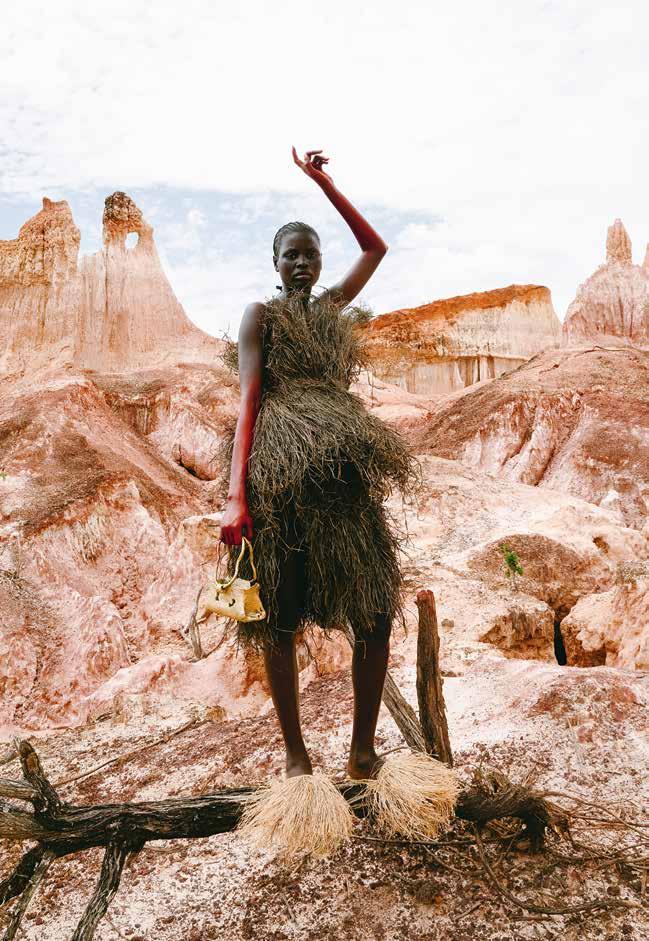

152 Most wanted A compilation of clothing, self-care and accessories that are beautiful, thoughtful and good

160 Amechi Mandi D/A UK asks its favourite tastemakers how they like to spend their downtime, from food to travel

Dirty Looks

Barbican Art Gallery explores fashionable decay for its upcoming autumn show –from rust to slime mould. See p124

Eynsham Baths at Estelle Manor. Read the full story on p38

For centuries, rugs have been used beyond the floor, whether as wall art, table coverings or draughtexcluding door hangings. Sydney-based furniture designer Tom Fereday has now added his own take, in a collaboration with fellow Australian brand Armadillo. The latter’s natural-fibre rugs have been incorporated into his furniture; the pieces (including a chair, bench and footstool) create a lovely exploration of contrasts – smooth and soft, timber and wool, softness and structure.

armadillo-co.com

US architecture and design studio Workstead’s offshoot lighting collection always seems to bring to the fore the essence of any material, from blown glass to metal and glossy lacquer. Its latest Lantern collection takes things to an opulent new level, with shades made from raw dupion silk and a handfinished silk tassel that adds a final flourish, leaning into the lights’ oriental inspiration. It comes in two sizes of pendant – the largest more than 90cm across – plus a half-dome-shaped wall light.

workstead.com

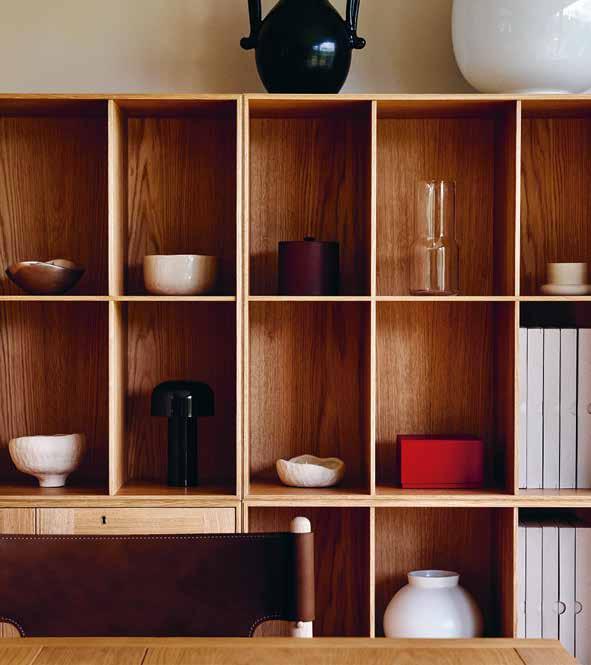

This oak MK shelving system, recently reissued by Fredericia, is a tribute to the timeless aesthetic of the 20th-century Danish masters. Clocking in at nearly a century old, its design was first conceived in 1928 by architect and academic Mogens Koch for his own home: he then spent the next 30 years

refining it so it could adapt to any space. It has just three modular components – square and rectangular open shelving, divided into equal compartments, plus a cabinet module with double panelled doors.

fredericia.com

Colder metallics such as aluminium are rapidly surpassing warmer brass and bronze, at least when it comes to the top Italian design houses. It’s not just about ringing the changes for the sake of it, though: part of the appeal is aluminium’s sustainable credentials, since it is infinitely recyclable. These

Arch side tables by Gallotti&Radice sum up the new mood. Futuristic and monolithic, they’re the work of Lebanese duo David/Nicolas, and come in four different heights ranging from 25cm to 40cm. gallottiradice.it

Named after the Italian word for ‘jewel’, Gioiello is a family of lights that are a collaboration between designer Marine Breynaert and architecture studio Hauvette & Madani. The collection of two wall lights and a table lamp combines a solid steel base with thick rings of Murano-made glass in a delicate palette, from clear to pale pink and sunny yellow; bubbles captured with the glass create a sparkling light with subtle reflections.

hauvette-madani.com / marinebreynaert.com

No one does a sun-soaked, laid-back aesthetic better than Lrnce, the Moroccan brand founded by Belgian artist and designer Laurence Leenaert and her partner Ayoub Boualam. All of its products promote Moroccan artisan skills, including this Hydria wrought-iron chair, which comes in a choice of four fabrics for its seat pad. Mix and match it with other chairs in the same family featuring motifs that include crabs, serpents and stars, all in the same charming illustrative style.

lrnce.com

The Plessy mirror is new from Novocastrian, the Tyne and Wear-based brand that takes its design cues from the industrial landscape of the northeast, with a focus on metalwork. Its slim frame features alternating stripes in various finishes, including light and dark brass, stainless steel and blackened steel. The design’s rhythm and repetition were inspired by the Victorian railway viaducts built across the region, which still stand as supreme (and beautiful) examples of engineering.

novocastrian.co

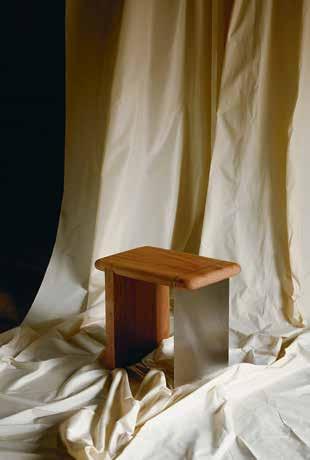

Interior designer Tabitha Isobel has released Ferro, a debut homeware collection made in collaboration with artist and maker Dom Callaghan. Each piece explores contrasts, such as this side table with its London plane top sliced through by a slim stainless steel leg. Everything is made by Callaghan in his Dartmoor workshop: “I like the idea that function can feel poetic,” he says. “When you pare something back to its essentials, every line and surface must carry weight and meaning.”

tabithaisobel.co.uk

Known for its cheeky attitude to fashion, Shrimps has paired up with rug and homewares brand Pelican House for a capsule collection for the floor. Called Vesta, its three rugs were inspired by patterns from the Shrimps archive, including Royal Garden, which features a repeating floral motif; while

flatweave runner Marlowe is named after Shrimps’ founder Hannah Weiland’s son. Everything is made in India and the rugs come in two sizes as standard, but can be custom made to order in any size.

pelican-house.com

PORRO @ LONDON DESIGN FESTIVAL 13-21/09/2025

Porro London

The Coal Office

T. +44 (0)7951865944

T. +39 3461109701 porrolondon@porro.com

Porro London

The Coal Office

1 Bagley Walk Kings Cross N1C 4PQ London

T. +44 (0)7951865944 porrolondon@porro.com

Porro X West Out East New York Flagship

31 East 31st Street @ Madison Avenue

10016, New York, NY

T + 1 212.837.2970 contact@porro-ny.com

Agent for UK:

Clemente Cavigioli W10 6BS London T. +44 207 7922522 clemente@cavigioli.com

Agent for US:

Kelly Design Agency T. +1 9172910235 shawn.kelly@porro.com

Mapa de Suelos (‘soil map’) is a series of stone tables by Lima-based art and architecture practice RF Studio. Their stratified appearance is based on aerial views and geological studies of the Andes and Amazon, with the landscapes translated into furniture by master stonemason Roberto Román using Peruvian marble, travertine and onyx. A large dining table for Lima’s Central restaurant is the most ambitious iteration to date, while three designs are available exclusively via design gallery Philia.

rfstudioperu.com

Dutch artist Rop van Mierlo’s signature technique is ‘wet on wet’ painting: watercolour brushed on to wet paper to create beguilingly splotchy forms. Now, he’s teamed up with CC-Tapis to translate his work into rugs, in a collection called Grandma Patterns. Van Mierlo’s brushstroke grids – a blurry take on plaids that “celebrate the cosy, cocooned world of grandmothers” – are faithfully translated into the soft, shaggy wool rugs, where mustard clashes with red and turquoise meets baby pink.

cc-tapis.com

The need for more flexible living spaces has given an unexpected boost to the popularity of the screen –they’re handy as room dividers, for subtly guiding the way or for disguising something unsightlybut-necessary in a corner, while also adding an arresting decorative flourish. Pinch’s Lecht screen does all of the above: with a European white oak frame, its infill panels come with plant-fibre inserts (in natural or black), or Pinch can also recommend alternative fabric options to suit.

pinchdesign.com

Design meets performance to offer an unparalleled Pilates experience developed with top instructors from around the world. Whether at home or in studios, Technogym Reform offers smooth, fluid movements and seamless training. Unlock exclusive on-demand workouts on the Technogym App.

Call (646) 578-8001 (US)

+44 20 3907 5000 (UK)

+39 0547 650111 (Rest of the world) or visit technogym.com

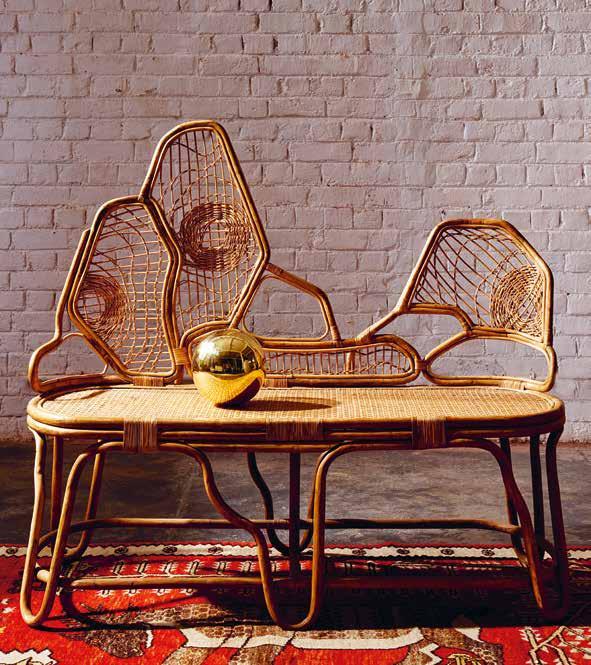

The New Delhi-based designer Vikram Goyal has devised a new, highly expressive language for cane furniture under his lifestyle brand Viya. The Chakra collection features sofas, chairs, stools, consoles and mirrors in natural or black cane, which have been woven and knotted into irregular, asymmetrical

forms. Further products include the Majuli floor lamp, with its cane shade atop a branch-like brass base, and ice and champagne buckets made from beaten brass cradled in an outer shell of canework.

viyadesign.com

Milan- and Paris-based Marta Sala works with leading design and architecture studios to create her furniture, with the Swiss practice Herzog & de Meuron the latest to collaborate. The architects have created a collection with its origins in real-life projects and a strong focus on wood. It includes this Armory dining table, a version of which was created for the historic New York events venue of the same name; and a pentagonal-seated upholstered chair first designed for Basel hotel Les Trois Rois.

martasalaeditions.it

Pierre Paulin’s F300 chair is the latest archive classic to be re-released by Gubi. With its quadrant of upholstery on a moulded base – and no flat surfaces to be seen – its is the epitome of late-1960s retrofuturistic style, designed by Paulin to invite multiple sitting positions. With an eye on sustainability, Gubi has upgraded the frame material from the original fibreglass/polyurethane to an engineered polymer made from waste industrial plastic, and a companion side table is also back in production.

gubi.com

The colour sense of 20th-century American artist Ellsworth Kelly has loosely inspired Moroccan brand Beni Rugs’ Chroma collection. The 11 striped rugs are intended as a study of the effect of juxtaposed colour on our perceptions, with fine shading, subtle variation of light and shade, and a

sun-soaked, earthy palette. They’re made from wool in Morocco using Beni’s Zahara technique, with a flat weave that feels wonderful underfoot; a second collection will follow, this time with knotted rugs.

www.benirugs.com

This Foyer bench has its roots in Copenhagen’s Radiohuset, the functionalist concert hall designed in the 1940s by architect Vilhelm Lauritzen. Lauritzen designed furniture for the interiors, too, which Carl Hansen & Søn re-released in 2022 as the Foyer collection: the new bench is an offshoot, a more compact version of the original that’s more suitable for domestic applications, from hallways to kitchen-diners. It has an oak frame and handstitched upholstery with piping cord and buttons. carlhansen.com

A cultural melting-pot goes into Racha Gutierrez and Dahlia Hojeij Deleuze’s products for Ebur, with the pair growing up together in Côte d’Ivoire, spending summers in Lebanon and studying architecture in Paris. Their third and latest collection has a strong focus on lighting and includes this Samarcande pendant, made in Italy, whose influences are part oriental, part Mediterranean palace. It comes in two sizes and is made from a Pierre Frey silk with a tassel from Samuel & Sons.

studioebur.com

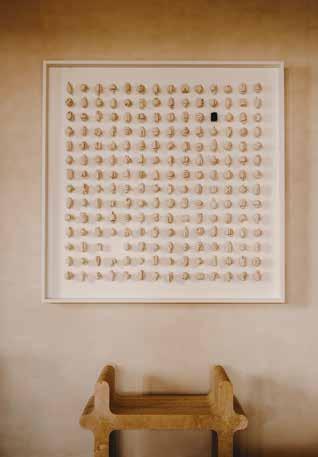

by Anne-Emmanuelle Thion and Thierry Grundman (Beta-Plus)

The Japanese concept of wabi-sabi – finding the beauty in imperfection, especially when it has developed over time – has been a major manifesto for interiors, architecture and gardens recently. This book both laments how it has been marketed as another lifestyle trend, and seeks its authentic essence. Architect Kengo Kuma writes a learned foreword about wabi-sabi’s roots in 15th-century Japan, and how its ideas of recycling and reusing old materials make it “shine with new relevance and vitality” today; and its authors cross continents to illustrate – with poetic beauty, of course – some of its contemporary custodians.

by Spencer Bailey (Phaidon)

This global exploration of hospitality hotspots features places that sit under the umbrella of Leading Hotels of the World, an initiative that represents more than 400 properties worldwide. It looks at them through a cultural lens, honing in on the local distinctiveness that make them special. Arranged geographically, the hotels within its pages include Brown’s in London (accompanied by a conversation between designer Tom Dixon and jeweller Solange Azagury-Partridge), Le Negresco in Nice and the five-star tented retreats of Capella Ubud in Bali – all of them defining luxury and promoting culture in their own unique way.

edited by Derek Lamberton (Blue Crow Media)

Many brutalist architectural projects were intended to be considered as a whole, with interiors that are just as radical and expressive as their exteriors. This book steps over the threshold and takes a look inside, via a series of essays illustrated by photography from names such as Iwan Baan and Simon Phipps. Uncompromising concrete abounds here – like Paulo Mendes da Rocha’s mid-1960s home in São Paolo – but brutalist architects also explored a playful side indoors with that same material, embracing bold-scaled geometry and manipulating light and space in the most dramatic and astonishing ways.

by Marta de la Rica (Mestiza Paris)

Interior designer Marta de la Rica’s love letter to Biarritz (where she spends her summers) is like walking through her sacred memories. Sat between the Bay of Biscay and the mountains, the city is a romantic place, and de la Rica captures all of that and more: from low-tide rocks to whimsical interiors and plates of food, this is a visual diary of the author’s life. Fullpage photography in vivid colour is broken up by a section in black and white featuring a stilllife ‘vocabulary of objects’, and there’s even a playlist and some pages dedicated to 100 pieces of advice for her children (“remember birthdays”; “learn to enjoy silence”).

As told to Elizabeth Choppin

Images Henri Kisielewski/ Felix Speller

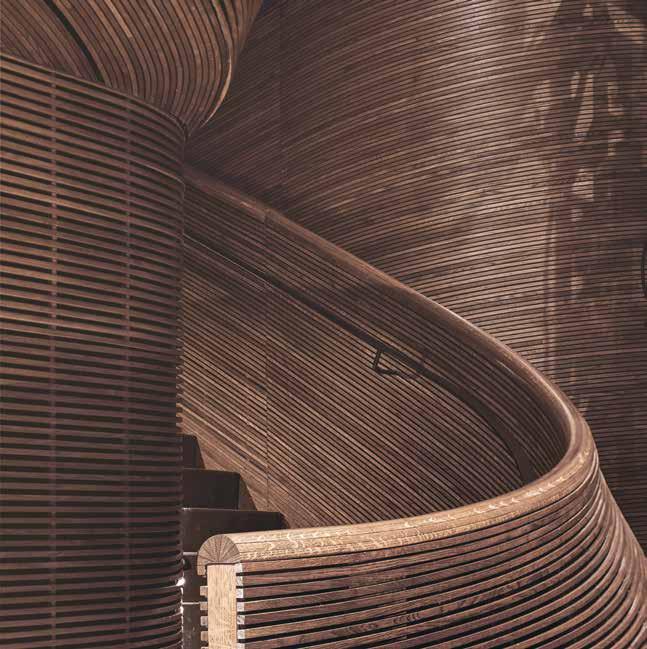

Hugh Scott Moncrieff, one half of London’s most sweetly monikered architecture practice, talks about a hedonistic new therapy space that promotes a communal high

What is your launch story and how did Cake’s founders cross paths?

Oliver and I met over drinks. A mutual friend introduced us, recognising our shared passions and complementary skill sets. It all started organically. I was working in Basel at the time, while Oliver was based in London. During Covid, we began collaborating remotely, which led to our first live project together, Soma Soho. The success of that project gave us the confidence to keep going, eventually leading me to move back to the UK and set up shop in March 2022. Since summer 2023, we’ve been in east London. Our team has grown from two to four to five, and now we often have seven or eight people around the table.

Why the name Cake?

Cake is delicious. It’s a mix of ingredients, a blend of flavours. It’s built in layers. Everyone loves cake.

What are your values as a studio? What’s your philosophy?

We believe in collaboration, radical design thinking, iteration, reference, irreverence and most importantly, having fun. We focus on how spaces feel and the impact they have on mood. We think both in architecture and interiors, often blurring the lines between disciplines. We like exploring contrasts and

contradictions in design, looking for the tension – the ‘rub’. We’re curious about what happens when different functions collide and how that friction creates something fresh and new. We’re interested in what’s on the other side. We have little interest in the black box of architecture/design. Although I often wear black clothes…

How do those values feed across your varying projects, from restaurants to giant saunas? We look for distinct moods and atmospheres in every project. We aim to create spaces that feel elemental, without distinguishing between architecture and interiors. We’re fascinated by how different functions can come together and how their tension sparks something innovative. We’re exploring how atmosphere shapes structure and tectonics. We’re interested in finding and celebrating those contradictions, looking for the ‘salt’ that gives the project a specific quality.

Can you tell us about Arc, the ‘contrast therapy’ space you recently completed in London’s Canary Wharf? What exactly is contrast therapy?

Arc is a wellness space that blends ancient rituals with contemporary science. The design carves out areas for connection, engagement and transcendence, offering a fluid sequence of

experiences and atmospheric conditions built on contrasts: hot versus cold, open versus closed, natural versus man-made, light versus dark. The team at Arc is experimenting with social wellness in new ways, blending music, party and play into the experience of contrast therapy itself.

How is this different from other wellness spas and programmes? What was the brief?

The brief was distinctly anti-spa; instead, it focused more on community and the physical/ emotional experience of contrast therapy. We looked to ancient examples of social wellness, like the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, built in the second century, but also explored more conceptual ideas about how society can gather in new forms of hearth and home.

Why was your studio chosen for Arc? You seem to have a knack for bagging unique commissions.

Our portfolio is diverse, and the aesthetic of cold-water therapy spaces was still relatively unexplored, so there was room to start from scratch. I think we’re good at that – taking a fresh approach. We also have a strong interest in nightlife and community culture. Parties are creative spaces for self-expression and discovery, and we’ve started weaving those ideas into our projects, just by being part of those communities, making friends and talking about what’s next.

Do you apply different principles to each project, or is there a baseline?

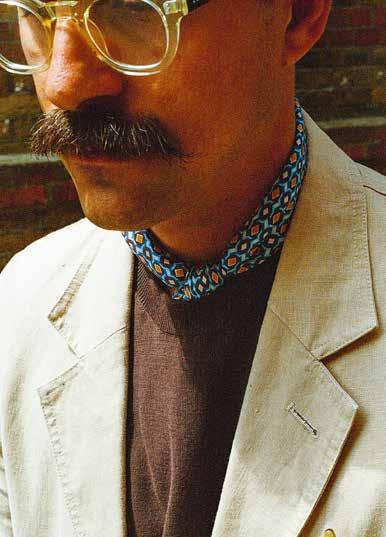

We treat every project as unique, but yes, we do

have a baseline of principles: collaboration, iteration and curiosity. When we start a project, we look for a hook – a conceptual anchor that guides us through the design process. It could be anything: an image, a song, a texture, a feeling. Our reference pool is constantly evolving, which keeps things exciting.

What’s the most fun for you? Designing restaurants like Kricket, clubs or private residences? What are the challenges?

All cakes are delicious. Every project is equal but some are just more equal than others…

Where are you based? Does this affect your perspective, or not so much?

Our studio is in Dalston, on the top floor of one of the Bootstrap buildings, surrounded by

spots like Cafe Oto, 40FT Brewery, The Dusty Knuckle and A Bar With Shapes For A Name. A lot of these places have become both friends and clients. The environment definitely impacts how we work. It’s easy to step out for a coffee or a lunch meeting in one of these places. They feel like an extension of the studio, helping keep the day-to-day dynamic and fun.

What’s next for Cake?

We’re deeply interested in the future of nightlife, and how clubbing and rave culture will evolve into new forms of space. We’re also working with clients in wellness and sports and are eager to see where these conversations lead. On top of that, we’re planning to launch our own nightlife initiative that blends music, food and art. More to come on that soon!

Left to

Arc’s sauna, which holds 60 people; the changing area, which repeats Arc’s wider palette of clay and timber

Two initiatives that harness design to rethink the universal human experiences of grief and honouring the departed

Deathis one of life’s few certainties and grief is a universal experience – yet the ways we deal with grief in the Western world remain surprisingly narrow, with mourning all too often treated as a period to move through discreetly and quickly. In recent years, however, the design world has begun to reckon with the rituals of death and the ways we remember those we have lost.

At this year’s Milan Design Week, Italian design powerhouse Alessi invited architects and designers, including Philippe Starck and Daniel Libeskind, to redefine the urn. Meanwhile, at the 2025 London Design Biennale, the medal for the most outstanding overall contribution was awarded to Malta, for a 1.8m-diameter monolithic limestone urn that can be added to over time to enshrine multiple family members.

While many of the projects tackling the taboo of death and grief are speculative in nature –more conversation-starters than real-world solutions – UK start-up Urn Studios is poetically reimagining the way we mark death. Founded in 2024 by Jonathan Hancock and Merel Swart, Urn Studios was born out of personal frustration with the status quo. When Hancock lost his grandmother, he was confronted with a sea of generic, often kitsch urns – none of which seemed to speak to the person she was. “I assumed there must be better options out there, something with more personality or artistic expression, but I couldn’t find anything,” he says. “I realised others must be facing the same situation.”

That absence sparked the idea for Urn Studios, a curated collection of handcrafted urns by

artists and makers. Each one is a personal artistic expression intended to be proudly displayed in the home rather than hidden away, challenging the stigma around visible mourning. “People’s personalities are so diverse, and this deserves to be reflected in their remembrance,” says Swart. “Grief isn’t black and white, so we don’t think the design surrounding it should be either.”

Some pieces are sculptural, others minimal, poetic or even playful. All are handmade with an emphasis on materiality and craftsmanship. British silversmith Marcus Steel has created a series of gilded and patinated silver ‘Treasure House’ urns; London-based ceramicist Milo Gibson has designed an urn set that includes a dish to display mementos; and woodworker Phil Irons has crafted a hand-turned ash timber urn with a lid made from an oak spoke that once supported St Paul’s Cathedral’s bellringing ropes. This tactile, human quality, often absent in the mass-market funeral industry, is a way to offer comfort and connection in life’s most difficult moments. The duo have also recently launched a collection of pet urns to honour the lives of animal companions.

Beyond their artistry and craftsmanship, what unites all the pieces in Urn Studios’ collection is the fact that these urns don’t attempt to hide or simplify loss. Instead, they offer a way to live alongside it. “Our loved ones don’t disappear when they die,” says Swart. “They remain part of our lives for as long as we remember them. Being able to help people honour their memories in a way that truly feels right is a privilege we don’t take lightly. While the topic might be difficult, the need is very real and design can play a powerful role.”

Words Mandi Keighran

Facing page

Clockwise from top left: Jo Taylor’s Urn i, clad in moulded clay shells; Keith Jaques’ Teardrop urn; Roselind Hunsel’s Kumba Konfo 1 (whose name translates as ‘gut creature’); Milo Gibson’s stoneware urn, which includes a memento dish. All by Urn Studios

Facing page

From healing spas to talismanic objects, immerse yourself in cutting-edge wellness design

Words / Henrietta Thompson

The room is buzzing. Not in the way that phrase usually conjures – it’s not full of excitable people, and there are no pulsing beats on the sound system. But the energy in this west London creative studio is palpable – in the multi-faceted sculptures, the giant crystal assemblages and the way sparkling sunlight catches every reflective surface.

This is the workshop of Balland-Galante, run by set designer and artistic director Juliette Balland, and jewellery designer and bioenergy therapist Claudia Galante. The pair’s work is certainly a vibe, and includes mixed-media, large-scale sculptural installations, illuminated ‘wall charms’ and talismanic home jewellery. These are creations that are magnetic in all the right ways: designed to be seen, but also felt.

They’re part of a wider shift as wellness evolves from a lifestyle category to a cultural ethos. Designers and architects embracing wellbeingled spaces are taking cues from many disciplines including neuroscience, spirituality and ancient material knowledge. They’re partnering with healers, movement experts and longevity specialists, often with potent results. Colours are chosen to calm the nervous system. Shapes are sculpted to soften the mood. Lighting is tuned to circadian rhythms.

At the leading edge of this movement is hospitality. The ‘healing hotel’ is a new typology in which wellbeing is the central narrative. Guests want to leave feeling and looking better than when they arrived – and putting the spa discreetly in the basement no longer cuts it. Instead, you should expect an entire wellness floor boasting the best views in the building. Design, of course, is key.

At Surrenne, the wellness brand developed by luxury hotel group Maybourne and conceived by its global head of design Michelle Wu, that narrative unfolds across three serene floors of soft travertine, watery blues and light-filled ritual. The latest outpost, perched above the sea at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, brings together longevity experts, skincare specialists and movement therapists in a space inspired by the coastline and the curative power of water.

“When we began designing Surrenne Riviera, we were deeply influenced by the natural setting,” says Wu. “From the start, we wanted to create a feeling of being suspended between sea and sky – as if you were floating. That sense of lightness was important not just physically, but emotionally, because healing isn’t only about the body; it’s about emotional resonance and nervous system regulation.”

Wu drew inspiration from water not just as a motif, but as a state of mind. “Water has both serenity and energy,” she says. “The word spa originates from salus per aquam – healing through water. The spa at Riviera is designed to immerse you in that effect. The walls gently undulate, the light is fluid.” Proximity to the sea is also prioritised, with studios that open on to glass-balustraded terraces that dissolve the barrier between land and water.

The phrase ‘blue mind’, which was coined by marine biologist Wallace J Nichols, describes the mildly meditative, calming state we enter when we are near or even just thinking about water. “Quite simply, water makes us happy,” says Wu. “It reduces cortisol levels, enhances emotional processing and activates parts of the brain associated with calm and self-reflection.”

Other new-wave hotel sanctuaries include Janu Tokyo, the younger, more vibrant sibling of Aman, where wellness is reframed as social connection as much as fitness and renewal; and Eynsham Baths, the Oxfordshire destination from the Estelle Manor team, which reimagines the classical bathhouse as a site of collective healing, with domed treatment rooms and cold plunge pools bathed in light.

Also in the UK, the Bothy at Heckfield Place in Hampshire and more recently west London’s The Grounding at Maison & Fifth are further examples of spas offering a more profound experience than a quick dip and back rub. Instead, they encourage guests to disconnect, and then reconnect with a version of self that they may have misplaced.

According to research in neuroaesthetics, the built environment can influence everything

Previous page Eynsham Baths, the Romaninspired spa at Oxfordshire’s Estelle Manor

Facing page Studios are open to seafront terraces at Surrenne Riviera

from heart rate to hormone levels. Curved edges reduce stress responses in the amygdala. Blue tones, like those used at Surrenne, are linked with lower blood pressure and a sense of calm. Tactile materials – wood, stone, linen –tether the senses to the present.

Beyond the spa, a new category is emerging: the social wellness club. Designed for self-care without the solitude, they respond to the idea that – in the age of smartphone overstimulation – more community and communion may be what we really need.

In North America, clubs like Remedy Place, Othership and The Well offer breathwork lounges, hyperbaric chambers, contrast bathing rituals and chef-led nutritional menus – and London, too, just got its own contrast bathing venue, Arc (see p30). They are all framed by rich textures, considered lighting and a soothing palette. The design, as much as the programming, is part of the treatment.

In the UK and Europe, the idea has found a softer, nature-led expression. River Arts Club in Buckinghamshire, 42 Acres in Somerset and Fritton Lake in Norfolk have all transformed historic properties into wellness-minded retreats rooted in regenerative principles. Interiors are poetic – stripped-back, lightflooded and deeply connected to the land. Meditation happens in barns and outhouses, cold plunges in lakes and rivers, and seasonal food is grown metres from the table.

Designer Francis Sultana is fluent in how the language of wellness is being translated into private homes. A meditation room has been a must for a while, but lately, he says, clients are requesting other wellbeing-led spaces. “In the past we’ve done contemplation rooms or spas,” he says. “Now it’s becoming the norm – not just a gym, but rooms designed for restoration and longevity.” His interiors lean on ancient materials such as terracotta, lime plaster and unbleached linen, and often integrate gardens for their emotional and physiological benefits. “Many of my clients now consider the garden essential to their wellbeing; some have even taken up gardening,” he says.

For those without green fingers, meditative art installations are an alternative. American artist James Turrell is the original reference point in this space, pioneering work at the intersection of perception and transcendence. His Skyspace rooms, open to the elements, and other light installations ask viewers to become still, to dissolve into colour and sensation. Chris Levine, too, uses light and frequency to invite altered states: his Stillness at the Speed of Light photography series has been shown at wellness summits as well as art fairs. These are works that hum, that pulse, that breathe.

It’s in this context – at the meeting point of art, interior and energy – that we circle back to Balland-Galante. A recent commission for a private club in Porto was originally meant for a lounge. But once the cascade of crystal, chain, mirror mosaic and copper was installed, the room was transformed. Furniture was removed, and the client reimagined the space as a sanctuary for stillness.

Balland and Galante describe their pieces as collaborative acts – not just with each other, but with the materials and the energetic quality of the space. The works are never quite finished. Light moves, a crystal is replaced, a form is rebalanced. “We’re following some kind of instruction,” says Claudia Galante, “but it doesn’t come from the head. It comes from intuition. From listening.” Many pieces include volcanic stone, copper or mirrored steel, chosen for their conductive properties. Others carry symbolism: the eye, the hand, the wing.

“Everything we do is about creating a space of peace – a place where people can feel something,” says Balland. “We choose materials for the ways they interact with the body’s magnetic field. We’re magnetic beings, after all.” They’re careful not to describe the pieces as healing objects. “We don’t like to use those words,” says Galante. “But they support the body and spirit. They help people feel good, to feel themselves again.”

Ultimately, agrees Balland, you don’t have to believe in anything. “It’s about how you feel. That’s it. That’s the work.”

Facing page Balland-Galante’s Wheel of Life sculpture, which incorporates pearls and semiprecious stones

A Glastonbury-bound Land Rover Defender delivers enhanced wellbeing, thanks to technology that allows travellers to ‘feel’ the sound

‘Sit back and relax’ may be a familiar phrase when it comes to driving, but this experience has been elevated to a whole new level with the Land Rover Defender Octa and its Body and Soul Seat (BASS). Creating a sense of sanctuary through new innovative haptic technology, BASS is making the journey just as valuable as the destination itself.

While the Octa is made for high-performance and off-road driving, inside, BASS allows its occupants to design an immersive multisensory world, created to regulate human feeling, hidden from the adventure outside. The new feature has the ability to alter the mood, using a seamlessly integrated system of sound and movement. Step in, enable your setting and see how your seat starts to vibrate via the tactile audio system from Subpac, a technology that

makes a “physical dimension of sound”. Subpac uses AI-optimising software, which together with haptic transducers generating highfidelity audio vibrations, creates a sensation where you can ‘feel’ the sound.

For this particular journey, the destination is Glastonbury Festival. After buckling up, a decision is made about whether to turn the tempo up or down. Do we want an aura of calm en route to Worthy Farm? There is an option to play your own tunes or, alternatively, turn the focus to the integrated wellness programme for a total energy shift. This ability to choose is all part of Defender’s approach: you get to pick how you feel.

The multi-sensory wellness programme was established to influence heart rate variability

and was formed in collaboration with Coventry University’s National Transport Design Centre and the School of Media and Performing Arts, which tested the haptic technology and recorded positive effects on driver alertness and reduced stress. The powerful vibrating seat has proven effects on the skin through to muscle and bone, adding further dimensions to moving with the beat of the music.

“It’s a sense of escapism,” says Mark Cameron, managing director of Defender. “There are six wellness programmes to choose from – Poise, Soothe, Serene, Cool, Tonic and Glow. All of them are designed to enhance mental and physiological wellbeing, reduce anxiety and improve cognitive responses.”

Passengers can navigate these settings from slow to invigorating, taking the intensity up or down with ambient sounds that are matched to each moment. The technology creates an encompassing feeling where sound can ease the fatigue of a long drive, or get you in the mood for where you are heading.

Having arrived at Glastonbury relaxed and ready, this is usually the moment when the vibe is turned upside down, but the essence of the BASS movement was also integrated into the dedicated Defender campsite. Heavy bass and beats were paired with a sense of refuge, including a Bamford Spa area where guests could unwind after a long day at the festival. “It is the perfect balance of enjoying the very best music and wellness escapism,” says Cameron of the experience, from the sauna and cold plunge to a peaceful moment with a massage or facial and nourishing plates courtesy of chef Simon Stallard. Leaving the festival and climbing back into the Octa, the mind, body and soul continue to restore.

Rimadesio debuts sleek, sculptural furniture with its refined Modernity Flow collection

Rimadesio is well known in the design world for contemporary storage solutions, modular systems and sliding doors. However, Modernity Flow, the Italian furniture brand’s latest collection, marks its first foray into seating for the home (with the addition of an elegant coffee table), highlighting a skilful interplay between form and function.

Designed by Giuseppe Bavuso, the six new pieces combine sleek silhouettes with opulent materials including timber, leather and refined upholstery. They strike an equilibrium between aerodynamic visuals and durable comfort: the Lambda table, for example, creates fluid lines and a sculptural profile reminiscent of the Greek letter that gives the table its name. It is crafted from veined marble and wood with Rimadesio’s new terrae finish (which has a brushed effect), or a lacquered glass top and choice of base colour. Lambda holds its own,

but is understated enough to coexist within the family of pieces that make up Modernity Flow.

Sinua, available as both a chair and an armchair, is defined by a timber frame that seamlessly holds both the seat shell in the centre and the rear supports. It works in tandem with the more minimalistic Wabi chair, whose appearance is something akin to a line drawing in furniture form: it’s lightweight, yet sturdy enough for frequent use. The Sophis chair draws parallels with Wabi, but its structure widens in the back, creating a feature of the backrest – a showcase of expert craftsmanship. Finally, the Nest swivel armchair is a crowdpleaser, with its sinuous body and blend of premium materials – a sophisticated balance of comfort and versatility.

Find Modernity Flow on show at Rimadesio’s flagship store in London.

Words Ciéra Cree

Images c/o Rimadesio

Above

Rimadesio’s Sinua armchair, with its timber frame and refined upholstery

Facing page

Two more pieces from the Modernity Flow collection: the Lambda table and Sophis chair

Hotel Wren, California. Read the full story on p56

Unique places to stay, in destinations of note

Rome itself helped inform the design of Nomos Hotel, housed in a former 18th-century Franciscan monastery in the city’s Regola neighbourhood. Henry Timi restored the property under the guidance of architect Angelo Zampolini, including bringing the courtyard fountain back to life, and looked to the historic beauty of the Eternal City to dress the 31 rooms. Classic travertine, timber and linen sit against an austere palette of clay, beige and greige, blending with the patina of the building and showcasing Henry Timi’s signature “material minimalist” style. The sober design continues in the bar and restaurant, while underground there’s a collection of relaxation and fitness rooms.

nomoshotel.com

Orient Express La Minerva, Italy

Having pioneered slow travel since 1883, the iconic train brand Orient Express has put down some more permanent roots in Rome with the opening of its first hotel, La Minerva. Originally built in 1620 as a private palazzo, the property became a hotel in 1811 and was a hotspot for writers such as George Sand, Stendhal and Herman Melville. It’s now been revived by designer Hugo Toro, who has blended

original features with a more contemporary art deco-influenced style and rich, tactile fabrics such as Italian linens, braided leather and, in the bathrooms, marble shell basins. Downstairs, the bar still sports its historic skylight, while the rooftop restaurant has sweeping views of the Roman skyline.

laminerva.orient-express.com

Tella Thera, Greece

With its geometric villas stacked in layers on a hill of olive trees, Crete’s Tella Thera looks more like a small village than a hotel. Each of its suites has been designed with sustainability in mind, from rooftop planting to help control indoor temperatures to a collaboration with local artisans to source materials responsibly and highlight Cretan craftsmanship. Inside, the earthy tones and minimalist, natural

furnishings relax and soothe, as do the panoramic Aegean views from the distinctive curved windows. A sustainable ethos also underpins the Anemoia Restaurant, which champions seasonal Cretan ingredients, while in the spa, treatments relax and rejuvenate with homemade botanical oils.

tellathera.com

Hotel Wren, USA

Sitting by Joshua Tree’s north entrance, Hotel Wren is a former 1940s roadside motel reimagined as the latest boutique hotel in California’s Twentynine Palms. Jessica Pell of LA-based Manola Studio worked with the building’s original layout and steel casement windows to create 12 guest rooms inspired by the natural landscape. Shades of sand, sage, rust and ochre mirror the changing hues of the desert

and have been paired with Saltillo tiles and plaster walls for a distinctly Californian feel. In the lobbyslash-living-room, a feature fireplace is surrounded by hand-carved shelves and frescoed walls depicting the natural landscape, with a large circular window looking out across the desert views.

hotelwren29.com

La Fondation, France

Paris’ 17th arrondissement isn’t usually somewhere tourists venture, but the increasing popularity of the Batignolles neighbourhood, and now the opening of La Fondation, might well encourage them to reconsider. The hotel’s (very un-Parisian) brutalistinspired exposed-concrete facade was created by Philippe Chiambaretta Architecte, and the interiors are by New York studio Roman and Williams.

Rooms feature light wood panelling and furnishings, with walls finished in white or deep blue, and covered with artworks curated by gallerist Amélie du Chalard. Facilities include two restaurants, a rooftop, a floating garden, a sports club and even a climbing wall and a semi-Olympic swimming pool.

lafondationhotel.com

For The Hoxton’s second Italian location, the brand has taken over a pair of architecturally significant city-centre buildings, a 16th-century palazzo and the 1980s Andrea Branzi-designed structure next door. Aime Studios has retained original elements such as the Renaissance limewashed walls and frescoes, as well as Branzi’s contemporary timber slatted facade, and designed the rooms according to

which building they sit in. A cheerful colour palette has been paired with Renaissance-style pink headboards (or graphic prints, in Branzi’s building), and finished with a mix of bespoke and vintage pieces to champion Italian craftsmanship and showcase the rich evolution of Florentine design.

thehoxton.com

Hotel Sant Ignasi, Spain

Originally a holiday home belonging to Menorca’s 18th-century aristocracy, Hotel Sant Ignasi has been revived by owner and local Menorcan Juana Vilafranca to embody the spirit and lifestyle of the island. Materials such as local limestone and marés sandstone from the Balearic islands, along with the olive-green window shutters that can be found across the island, respect vernacular architecture;

inside, neutral-hued rooms – some with private terraces – showcase locally crafted furnishings, ceramics and layers of natural materials. Facilities include a seasonal farm-to-table restaurant, plus yoga classes and massages in the art-filled gardens and surrounding oak forest.

santignasi.com

Words

Denton Hall aims to do nothing less than rethink the English country house stay, via rewilding, positive environmental impact and reconnecting with nature

Debika Ray

Images Lucy Franks/ Sean Knott

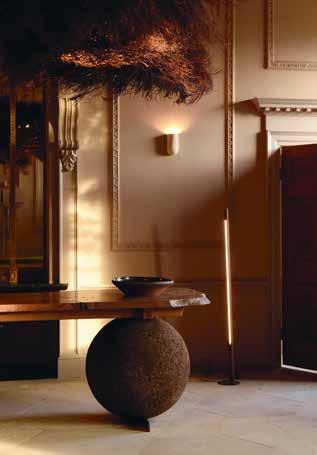

“Our task was to redefine rural luxury,” says Lou Davies, co-founder of architecture and design studio Box 9. The context: Denton Hall, a grand Grade I-listed Georgian home at the centre of a 2,500-acre reserve bordering the Yorkshire Dales, which since 2022 the practice has been transforming into a property available for exclusive hire.

It’s no mean feat to rethink the English country house: for centuries, these estates have epitomised elite living. “In the classic way, this building was filled with riches and rarities –stuff everywhere you looked – that would likely have been selected based on how expensive they were,” says Davies. But in our fast-paced, distraction-filled, environmentally damaged, digitally addled times, opulence is no longer synonymous with the good life. “For me, wellness and luxury are about having the space and time to reconnect with yourself – it’s about rest and peace,” says Davies. This ethos guided Box 9’s vision for Denton.

The home itself was at the heart of this, but in a way that was intrinsically connected to the landscape. The latter has been undergoing a wider restoration and rewilding project: removing chemicals from soil, slowing water flow to reduce carbon loss, reducing sheep grazing to boost biodiversity and introducing native species like Tamworth pigs and White Park deer. The idea is for nature to thrive and for visitors to benefit from its restorative power.

For the interiors, the designers took their cue from these glorious surroundings. “We wanted people to simply stop and bathe in this incredible space,” says Davies. “To fall back in

love with nature and become custodians of their wellbeing and the planet.”

The Grade I listing prevented any major changes to the layout, so creativity was crucial in transforming restrictions into opportunities. For example, what was once a bedroom could be a lavishly large bathroom, with a giant shower in the middle of the room taking in the view. “You can stand in the middle of the room and feel like a bird in nature,” says Davies.

The starting point was clearing the clutter: gilding and Wedgwood gave way to earthy hues and soft textures chosen for calm, and Davies explains how “a quieter palette turned the hall’s historic details into a vast clay sculpture.” Every new addition faced a rigorous criterion: “No material, maker or design approach was allowed to re-enter the hall unless it would have a positive impact – neutral wasn’t good enough; negative definitely wasn’t allowed; positive impact was the baseline.” The objects that made the cut are crafted pieces by skilled makers who may not otherwise be showcased in buildings such as these.

Among them are pieces that bring nature and the wild into the heart of the building: in the reception is a four-metre imposing lighting feature by East Sussex-based Studio Amos –run by craft duo Annemarie O’Sullivan and Tom McWalter – made from heather foraged from the nearby moors. Elsewhere is a large reception table made from a piece of timber from a fallen oak tree, supported on a sphere made of cork, which was designed by Box 9 themselves in collaboration with West Sussex furniture maker Ted Jefferis of TedWood.

Other pieces are more experimental, bringing a sense of the unexpected into this historic context – including Welsh materials studio Smile Plastics’ cabinetry, and desks made from solid wool by Jason Posnot of environmentally conscious design practice Or This.

The underlying intention is to restore people’s mental and physical health, says Davies, pointing to some of the interventions that allow this. “What traditionally would have been a poker room we’ve called the ‘stillness room’, and it’s for meditating, yoga and mindfulness. And the design itself encourages people to go outside: there isn’t a gym inside –it’s out there when you are running, cycling, exploring, climbing and swimming.”

More ambitiously, the intention is to upturn people’s relationships with buildings like this – an inherent challenge when luxury is almost by definition an exclusive commodity. There

are public walking trails that anyone can enjoy, with plans to make the offering more diverse over time: “The hall won’t be affordable for everyone, but there will also be little cabins on the moors and farmhouses of different scales, so there is a spectrum of properties that people can access and have the same experience,” says Davies. Box 9 has also worked on the design of the estate’s village inn, The Penny Bun, which has five rooms, while The Coach House houses six smaller lodges; a farmhouse and barn are set to launch in late 2025.

The ultimate goal, says Davies, is a new vision for the stately home. “We wanted to ask how we stop the damage that, historically, a lot of these kinds of estates would have caused to the planet, landscape and local community by trying to create an exclusive, private, high-end escape that only the very privileged few could afford to stay at. Our intention was to set a new path for them that was inclusive for anyone.”

“A

quieter palette turned the hall’s historic details into a vast clay sculpture”

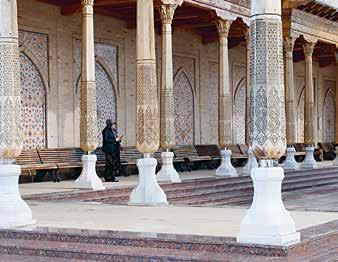

Journeying from Tashkent to Nukus, discover Uzbekistan’s layered history, and a country that’s rich in culture, craft – and resilience

ItPrevious page

Shilpiq Qala in Karakalpakstan, a former Zoroastrian Tower of Silence

Above

Traditional Islamic architecture at Suzuk-Ota Mosque

Facing page

Top to bottom: Nukus’ State Museum of Arts; Madina Kasimbaeva at work; the modernist lobby of the State

Philharmonic Society of Uzbekistan

Turkestan Palace of Arts

was no ordinary night in Nukus. Pianist Kirill Richter and the National Symphony Orchestra of Uzbekistan took to the stage in the desert south-east of the city, close to the border with Turkmenistan. They played before the Shilpiq Qala – a former Zoroastrian Tower of Silence, where corpses were once left to be eaten by carrion birds – which was illuminated by red and white lights. After the concert, families in traditional dress offered visitors into their yurts for tea and local pastries. It proved a fitting end to a trip across Uzbekistan that was characterised by collisions between the past and present, as well as an ever-present sense of local hospitality.

I started off in Tashkent, the country’s capital, a city in constant movement. The roads are surrounded by lush green borders and the pathways are kept immaculately clean by gangs of broom-wielding masked workers. There is a new commercial and business district that is one-part Dubai glass-and-steel and one-part neoclassical historicist blocks, filling up at ground level with luxury shops and coffee bars.

An earthquake in 1966 devastated much of the city, which gave Soviet planners carte blanche to rebuild. Consequently, Tashkent is strewn with astonishing architectural marvels. The most photographed is Hotel Uzbekistan, a

brutalist hulk with an intricately latticed facade. The city’s Metro has a grandeur that rivals its Moscow analogue. The State Museum is clad in marble reinterpretations of traditional panjara panels used to screen the sun. Chorsu Bazaar, a gargantuan market selling everything from pig legs to silk scarves, sits under a vast blue ceramic dome. Post-Soviet regimes have added their own grand projects, such as the fortress-like Turkiston Palace. Strikingly, even the city’s humbler housing buildings often integrate historical Uzbek motifs.

There are still traces of pre-Soviet history in Tashkent. One elegant Russian Empire-era mansion now houses the Republican Children’s Library, which was opened in 2023 after a redesign by St Petersburg-based practice Ludi Architects. The Hazrati Imam complex contains what might be the oldest Qur’an in the world, dating from the seventh century. Nearby there remains a dense network of courtyard houses. One of these, a former madrasah, houses an artist’s residency space run by the Centre for Contemporary Art. Opened last October after a restoration by Paris-based Studio KO, it allows four residents to live, work and exhibit in the same quarters.

Craft heritage is also alive. At Rakhimov Ceramics, Akbar Rakhimov and his son Alisher forge works that build on historical precedent. Rakhimov senior’s father Mukhitdin wrote the book on Uzbek ceramics, preserving its patterns during an era hostile towards local craft. Elsewhere in the city there is an entire craft district. Craftspeople are invited to live in contemporary courtyard houses. The most celebrated resident Madina Kasimbaeva has helped to revive suzani, a distinct type of embroidered textile used as tapestries. Kasimbaeva has adapted them into garments, and a museum dedicated to her work is currently under construction.

From Tashkent, it is about a two-hour flight to Nukus. But the two cities feel worlds apart. I was there for the inaugural Aral Cultural Summit, housed in a vast reinterpretation of a yurt on the city’s southern edge. This two-day gathering brought together an international

cohort of architects, artists, designers, environmentalists and others to discuss the future of the region once fed by the Aral Sea. This was once the world’s third-largest lake, before Soviet irrigation schemes turned much of it into desert. ‘Disaster tourists’ fly north from Nukus to Moynaq, a former port town where abandoned ships rise out of the sand.

Nukus is the sixth-largest city in Uzbekistan and the capital of the autonomous community of Karakalpakstan, which is an ethnically and linguistically distinct region. It may cover about a third of the country but has only a twentieth of the population. In ancient times it was a thriving agricultural centre, and during the 1960s and 1970s experienced a period of flourishing due to the irrigation of the Amu Darya river, a tributary of the Aral Sea. Today, the river has been diverted elsewhere. This and rising temperatures have led to drought. The wind carries the toxic remains of Soviet-era pesticides and microbes from biological

A curated guide to Tashkent’s cultural

WHERE TO HEAR MUSIC

Alisher Navoiy Theatre gabt.uz

WHERE TO SEE ART CCA Tashkent ccat.uz

Museum Of Applied Art artmuseum.uz

WHERE TO SHOP

Kanishka kanishkaspb.ru

Moona moona.shop

Chorsu Bazaar

Tafakkur ko'chasi 57 (no website)

WHERE TO DINE

Lali

familygarden.su/lali

Caravan caravangroup.uz

Central Asian Plov Centre

1 Iftixor ko'chasi (no website)

weapons testing. On my last night in the city, a salty storm covered its wide boulevards and empty squares in an ominous fuzz.

In 2022, Karakalpakstan erupted in protest over plans to remove its autonomous status. Since then, ongoing attempts to revitalise the region have redoubled. Sometimes this seems a long way off. One morning, I visited Istiklal Park, a dilapidated amusement park with all the cliches of post-Soviet decrepitude: cracked pavements, dust-covered bumper cars, a pack of wild dogs. Ludi Architects, tasked with its reconstruction as well as the creation of a new children’s library, has its work cut out.

Tourism is one route. Since Uzbekistan allowed visa-free travel in 2018, visitors to the country have begun to increase. The majority head to the heritage sites associated with the silk roads: Bukhara, Khiva and most of all Samarkand, whose neoclassical sprawl is punctuated by the jewels of Timurid architecture, when it was the capital of a continent-spanning empire. Nukus will be the gateway to the desert and its Khorezm fortresses and necropolises.

Above Chorsu Bazaar in Tashkent, with its distinctive blue ceramic dome

Facing page

Top to bottom: The Centre for Contemporary Art runs residencies at this former madrasah; Hotel Uzbekistan, an architectural icon from the Soviet era

The city itself also boasts one truly extraordinary sight, the cumbersomely named State Museum of Arts of the Republic of Karakalpakstan Named After IV Savitsky. Forget Abu Dhabi: this is where you’ll find a more authentic Louvre in the Desert. It emerged from the extraordinary endeavours of Savitsky, a Kyivborn artist, archaeologist and electrician who visited Karakalpakstan on an archaeological expedition in 1950. Eight years later, he moved to Nukus. Here, he collected and collected. First came Karakalpak garments, jewellery and textiles. Then he began acquiring works of the Central Asian and Russian avant-garde. Thousands of works that might have been purged found a new home, far from the eyes of both Tashkent and Moscow. It is now the second largest repository of Soviet avant-garde art in the world. If you ever feel jaded by the fungibility of many art collections, this is the antidote. The museum displays masterpiece after masterpiece by a coterie of artists rarely encountered anywhere else. It alone makes the journey to the desert worth it.

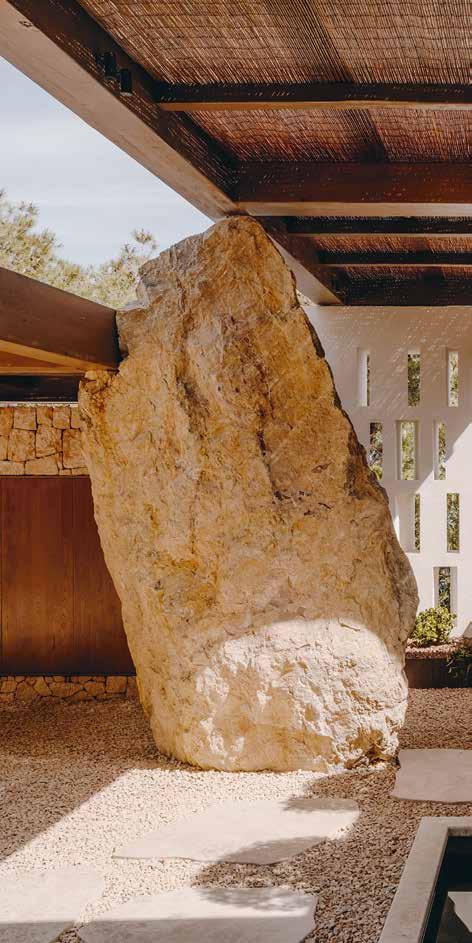

An Ibizan finca reinvented as a place where time stands still

Words / Charlotte Abrahams

Images / Salva López

“Sometimes you have to go back in order to go forward,” says Dimitris Karampatakis, co-founder of Athens-based architecture and design practice K-Studio. He is talking about the recent renovation of a traditional finca on Ibiza’s rocky southern coast. His clients, a young couple, had owned the property for some time and it had been altered on several occasions over the years, but they came to K-Studio seeking a major reinvention. They envisaged a holiday haven in which they and their multi-generational family could both retreat from the world and socialise with their frequent guests; a place that spoke of them and their love of art and craftsmanship that was also imbued with a sense of place and history.

“We felt we had a responsibility to make sure the house had a clear link to where it comes from and what it used to be,” says Karampatakis of the project, which is named Villa Infinity. “Many of the traditional features had gone but you could see the palimpsest of the original in the dimensions and the scale of the building. Rather than working with a preservation mindset, it was more about making anew in a way that captured the beautiful rhythm, depth and sequence of these old fincas.”

They began with the layout. Out went the fragmented social spaces, replaced by a harmonious grouping of gathering places, each one spilling into open-air lounges such as the

spacious lawned area around the pool that stretches out invitingly from the pergolaframed dining room. The more intimate spaces – five ensuite guest bedrooms, a large children’s room furnished with a pair of custom-made bunk beds roomy enough for both climbing and sleepovers, and a series of smaller terraces for reading or quiet conversations – are secreted across the ground and first floors.

Right at the top is the master suite, a series of indoor and outdoor zones that combine privacy with expansive views. The bedroom itself, cocooned in a soft palette of creams and browns, features K-Studio’s custom-made bed positioned to look across the cactus roof garden to the sea, while on the other side of the metalframed doors are a secluded terrace (furnished with armchairs by Espasso and loungers by Atelier Malak), and a sumptuous outdoor sitting room made for private stargazing.

K-Studio also used the past as inspiration for the palette of materials. Local stone, cut in irregular shapes by master masons to echo the vernacular architecture, clads both exterior and interior walls; traditional flagstones on garden paths and some of the interior floors blur the separation between outside and in, and wood is everywhere, from the oak cabinetry and Burma teak furniture to the chestnut ceiling beams suggestive of age and time. In the lounge, master bedroom and on the canopies of many

Previous page Villa Infinity’s dramatic entrance, shaded beneath a timber pergola

Facing page

Pivoting doors dissolve the boundary between inside and out

“We felt we had a responsibility to make sure the house had a clear link to where it comes from and what it used to be”

of the pergolas, these beams are paired with wicker – not, Karampatakis accepts, an original feature, but very much in the spirit of a traditional finca.

And here at Villa Infinity, spirit is all. “Often as designers you get a brief that quantifies lots of things – how many bedrooms and bathrooms are needed, etc,” says Karampatakis, “but with this project the discussions were driven more by how the clients wanted to feel in the house. That was exciting for us because it meant that form could follow experience.”

This approach applied even when the client’s brief was more prescriptive. Asked to provide a ground-floor space for late-night conversation, the studio created a large sofa pit. Comfortable and self-contained, its form makes talking easy. (It is also a neat reference to the 1970s, a recurring theme throughout that speaks both to the couple’s love of the period and the decade in which Ibiza became cool.)

The most important experience that this house provides is the chance to slow down and get into a mood of rest and relaxation. Every detail has been created with that in mind, starting with the entrance, which has been reimagined as a shaded garden framed beneath a wooden pergola. “Entering a place is very important,” says Karampatakis. “It gives you the start of the story. This villa’s story is a holiday way of life so

we wanted the entrance to be deep enough to allow time to transition into that mood.”

Not only does the entrance garden slow you down – it also sets out the palette of what’s to come in terms of colour, material and form. By the time you reach the line of heavy pivot doors that subtly marks the transition from outside to in, you have walked on stone, beneath wood and wicker and past the sculpted niches that subtly ornament many of the interior walls. Out here on the lime plaster wall, these niches have been left empty; inside they are often used to display precious objects the owners have collected over the years.

This is a house that wears its drama quietly, so the vast concrete and lime plaster staircase that sweeps in a sinuous curve through its centre comes as a surprise. It is a thing of sculptural beauty that brings a sense of movement and energy to the interior but it is also another slow-living intervention. “From a functional perspective, it would have been better to have a straight line,” says Karampatakis, “but we were designing with a holiday mindset. We wanted people to have time to touch the staircase and make the mundane activity of going up and down stairs a sensual experience.” Time to appreciate the beauty of a staircase is a rare luxury in our too-busy world. K-Studio’s triumph here is to have made a home where time seems to be infinite.

Facing page A ceramic piece by Olivia Cognet hangs in the living space – a room full of references to Ibiza’s 1970s bohemian heyday

Facing page

This house is full of spaces to gather – perhaps none of them more friendly that the ground-floor conversation pit

The staircase has been remodelled in concrete and lime plaster to create a more prominent sculptural feature

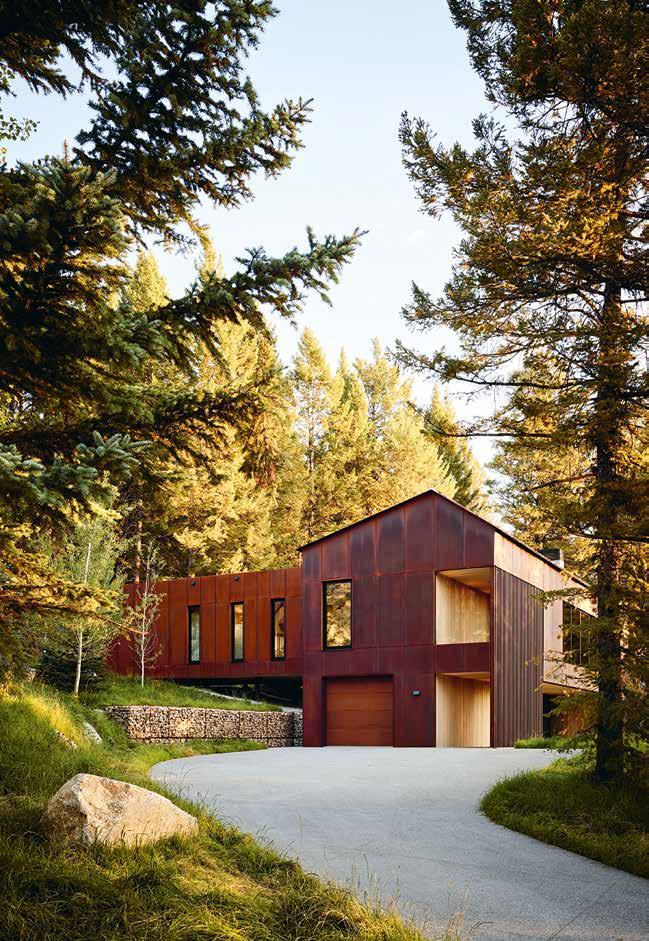

The minimalist design of a home in Wyoming fosters peace and connection to the surrounding landscape

InWyoming, home of the iconic Yellowstone National Park, nature reigns supreme. Here, panoramas are nothing short of magnificent and wildlife doesn’t just exist – it thrives. Far from the hustle and bustle of urban life, the calm of the breathtaking landscape sets a slower pace. For those lucky enough to call this place home, it is a true privilege. The owners of this property – a young family who spend most of the year in Miami – have a deep appreciation for the outdoors and are acutely aware of the magic of this place. This is precisely why they decided to build their holiday home here.

Heavily forested and dotted with boulders, their plot is located adjacent to a ski area, on a slope that rises up in the majestic Teton Range, providing views of the Snake River Valley and surrounding mountains. The brief from the homeowners was clear from the start: create a simple design. This immediately resonated with their architects CLB, a practice also based in Wyoming. As practice partner Eric Logan says, the intention was to craft “a home designed for the essentials rather than excess.”

With a light approach on the land, the twostorey, four-bedroom house, which spreads over 260 sqm, is organised in two simple volumes at right angles to each other. “The goal was to create something humble that was grounded in the principle of living simply,” says Andy Ankeny, also a partner at the practice. “It was to be nestled into the mountain environment with a rustic, durable shell.” CLB’s design philosophy is “inspired by place,” and the project closely adheres to that ethos.

With most houses in the neighbourhood being traditional in design, CLB’s vision to shape a very contemporary structure was challenged, but the architects were willing to push through. “We were very aligned with the client, but with the local homeowners’ association, it was a battle to receive approval, with multiple rounds of discussions,” says Logan. “We had to change the overhang and roof design to separate the vertical wall plane from the roof. We also had to modify the materiality. However, it ended up being positive change.”

The rugged topography guided many of the decisions and required the team to follow a sensitive creative concept to adapt the project to the site. “The boulder adjacent to the entry is the tip of the iceberg – almost literally,” says Logan. “There is so much rock mass below that is not exposed. During excavation that boulder could not be moved, so the configuration of the

Previous page

A pair of rightangled volumes follow the site’s topography

Above

A generous steel deck nestles into the treetops

Facing page

The rusted exterior gave the house its name, Caju –an orange fruit

house had to be reoriented. It became a driving force for where the house was located.”

At the heart of the programme, the materials were carefully chosen to be robust while having their own strong identity. As such, the home’s weathered Corten steel exterior is particularly convenient for its low-maintenance qualities. It also inspired the name of the house, Caju, which is borrowed from a Brazilian fruit with an orange shell (it’s a nod to the family’s Brazilian roots, too). The metal screening completes the simple yet powerful form of the structure while subtly creating pattern and shadow. In the interior spaces, concrete, stainless steel and wood combine in complete harmony, finding balance between warmth and rawness. “It is a home where simplicity and honesty of materials are derived from the belief that there is beauty in functionality,” says Ankeny. “This house is about material restraint and efficient space planning.”

The main living areas – an open-plan living, dining and kitchen area along with four bedrooms – are strategically positioned on the upper floor to maximise the views. Meanwhile, the lower level is dedicated to more practical spaces, including the garage, mudroom and gym. A sculptural staircase built along the wall is the first thing you see when you come in, its perforated stainless-steel structure creating a veil, allowing light to filter through.

“When you are in the home, you are really connected to the place,” explains Logan. “It feels like living in the treetops, with long

perspectives and the courtyard that allow you to be in the landscape.” To minimise the building’s footprint, the elevated bedroom wing is supported by slender columns that touch the hillside lightly. Similarly, the rear deck, which is another invitation to enjoy the area’s natural splendour, is supported by a system of concrete piers and steel elements that allow it to hover above the site.

CLB’s ethos is that the interiors should be an extension of the architecture, with no obvious line where one ends and the other begins. Very few pieces of furniture adorn the minimal interiors: with the exception of two chairs, a coffee table, a sofa and a dining set, everything is built in, and seems to almost grow from the larch internal walls. “The architecture is the furniture,” says Logan. “There is only one art piece in the house. This is intentional. As the owner aptly said: ‘The architecture is the art.’”

Previous page

The main living areas are on the upper floors, to maximise the view

Facing page

A steel mesh balustrade veils the staircase

Above

The interiors are wrapped in larch, connecting to their surroundings

“It is a home where simplicity and honesty of materials are derived from the belief that there is beauty in functionality”

a

a

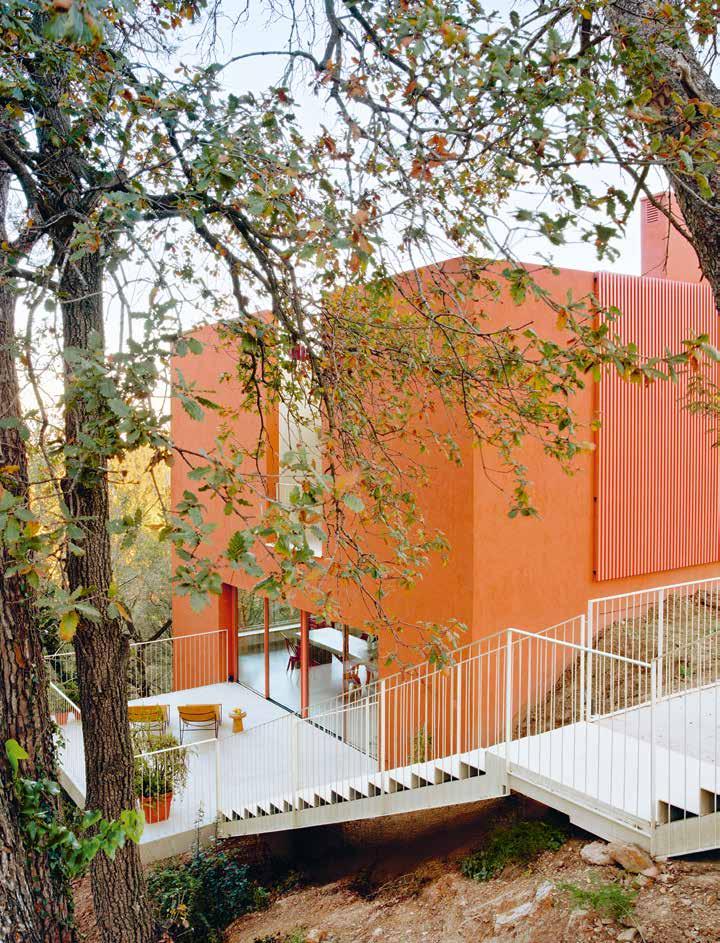

Perched on a hillside on the outskirts of Barcelona and intimately connected to the land, Raúl Sánchez Architects’ new-build house is inclined to impress

Words / Jonathan Bell

Images / José Hevia

Topography is the creative architect’s friend. Set on a steeply sloping site in Sant Cugat del Vallès, just north of Barcelona, this new house by Raúl Sánchez Architects makes full use of uneven terrain to enhance the drama and scope of the living experience, while simultaneously preserving as much of the landscape as possible.

The clients tasked Sánchez with creating a modest 175 sqm family house on a relatively unprepossessing plot in a hillside housing subdivision. Hard stony ground falls away steeply from the access road at the upper part of the site, inviting a new configuration and architectural approach. Sánchez explains that the location was a combination of design intention and local rules. “The house had to be five metres from the site boundary; at that distance, the ground is already descending,” he says. “The idea was to make the house appear as a compact single-storey volume at street level, then expand it down the slope. In addition, the best views are towards the valley.”

The solution was to perch the new house above the landscape, mounted between two concrete screens that serve to bracket the structure and the floor slabs. These slabs were designed to be as thin as possible – just 20cm – and all structural elements are completely contained within the frame of the house, leaving the interior as a seamless open space.

Rather than appropriating the architectural language of the floating, cantilevered dream house of Californian legend, Casa Magarola makes a bold connection with the landscape, with structural elements given an earthy hue that tones with the reddish soil, even if it doesn’t match it exactly. The colour “claims its own identity but also creates a strange familiarity,” says Sánchez. “This is something I found in the work of Michelangelo: in everything he did, you can recognise something familiar, but at the same time it was as if you had never seen it before.” In contrast, a light yellow, almost sand-like tone has been used for the principal facade and referenced in internal cabinetry and window frames.

Site conditions also shaped the arrangement of the interior, given that access necessarily comes from the upper levels of the site. Visitors step down a cantilevered staircase to a terrace formed from an extension of the primary floor slab. From here, sliding doors provide direct access into the main living space, a kitchen/ dining room and living area arranged around a central service core. The north-facing facade is entirely glazed, and a centrally placed steel spiral staircase leads up to the bedrooms.

This ‘upper’ level is more cellular, carefully planned around the double-height staircase void and twin terraces facing east and west that create a view through the interior of the house

Previous page

Stairs descend from the road to a welcoming terrace

Facing page

Clockwise from top left: Openings are protected from the sun by latticed screens; the house’s slim concrete supports; the main entrance is via sliding glass doors into the kitchen; greenery surrounds the site

from the landing. Two double bedrooms share the glazed north facade, while a smaller bedroom is tucked into the south facade. Two bathrooms – one of which has direct access on to the west terrace – are joined by storage, with an arrangement of sliding doors that allow one half of the floorplan to be given over to a primary ensuite bedroom if needed.

Because the living and sleeping spaces have been raised above the landscape, existing trees and vegetation have been preserved (only two out of the 40-plus trees that were on the site were felled). This allows branches to brush right up against the facade, giving the house another connection with the environment. The structure is topped by a roof terrace, accessed via the spiral stair, with views of mountains and valleys; the geometric precision of the plan is playfully offset by a stair access turret set at 45 degrees to the rest of the structure.

Despite the modest scale and budget, a rich simplicity pervades the house, down to the material finishes, with key components picked out in high-quality materials, as well as playful elements, like the local rock that forms the

“first step of the house”. This is Sánchez’s nod to the work of 20th-century Italian architect Carlo Scarpa and the acknowledgement of the primacy of landscape, as well as the staircase’s role as an “invitation to ascend”.

The freedom afforded by the structural configuration has allowed Sánchez and his team to create precise geometrical alignments. Through meticulous planning, the arrangement of facades and floorplans, as well as the placement of partitions and openings, conform to a mathematically precise grid derived from the naturally harmonious golden ratio.

The orientation of the house and the arrangement of balconies and windows aid cross-ventilation, while rooftop solar, radiant floor heating, and rainwater collection and reuse help keep a lid on the house’s energy consumption. For Sánchez, the design and construction process is not remembered as a series of individual challenges, but as a “sequence of thoughts, all related, and all directed towards a common goal”. The end result is a house that is both a part of its landscape and a distinctive architectural form.

Previous page

The kitchen features a huge island dining table in concrete and ceppo di gré stone

Facing page