He wanted badly to vote to acquit the president — it would be so much easier.

HOW MITT ROMNEY’S FAITH DEFINED HIS POLITICAL CAREER — AND BROUGHT IT TO AN END. by m c kay coppins

The Lift Clinic has a non-surgical, non-invasive treatment that can provide instant relief from chronic pain such as: • TMJ • Sleep Apnea • Neck Pain • Migraine Headaches

Free assessment with imaging included, schedule your consultation now!

“This is not an Oregon problem. It’s occurring throughout the country.”

Born and raised in Mexico, Escamilla is the first Latina elected to the Utah Senate, where she is minority leader. She was the first director of Utah’s State Office of Ethnic Affairs in 2005. A past vice president of Zions Bank, she is co-founder and managing partner of ESCATEC Solutions. Her commentary on the importance of civic engagement is on page 13.

Coppins is a staff writer at The Atlantic. He’s the author of “The Wilderness,” a book about the battle over the future of the Republican Party. His work has been published in The New York Times, The Washington Post and Newsweek. An excerpt from his latest book, “Romney: A Reckoning,” a political biography of Sen. Mitt Romney, is on page 34.

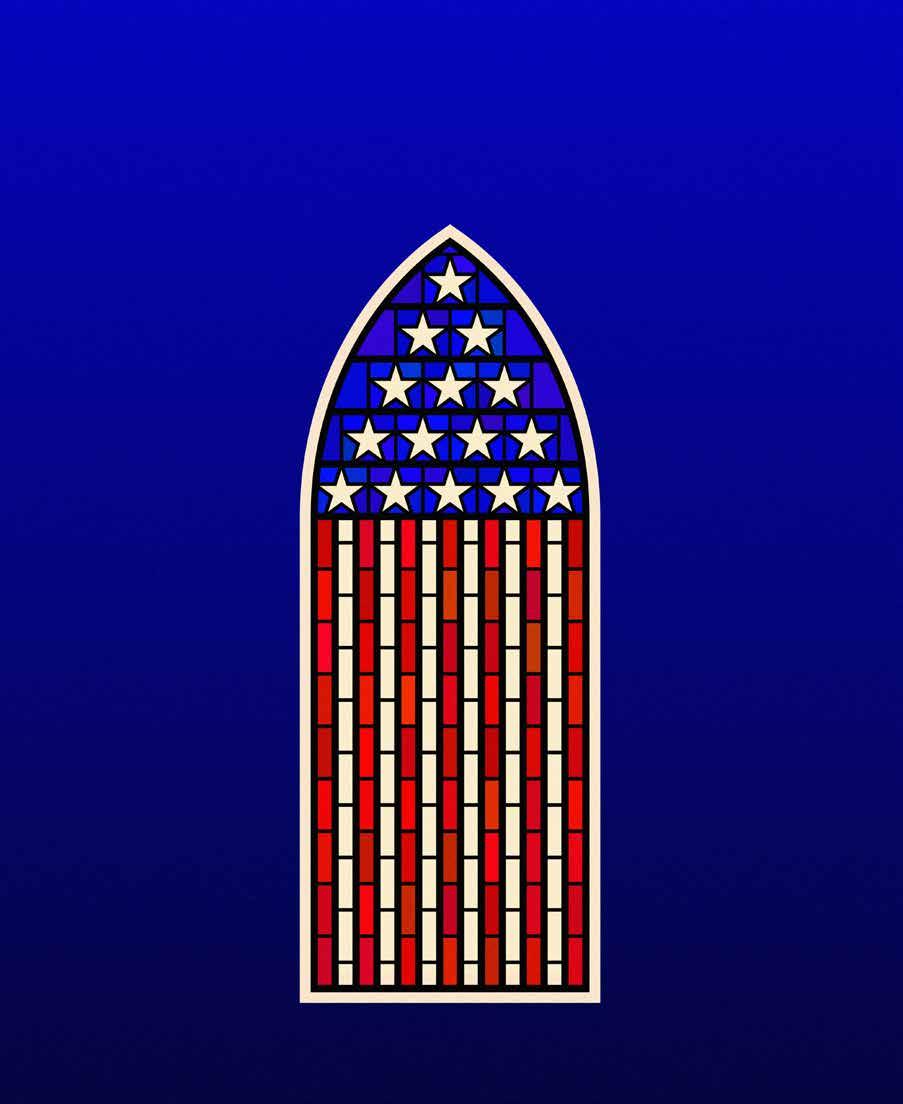

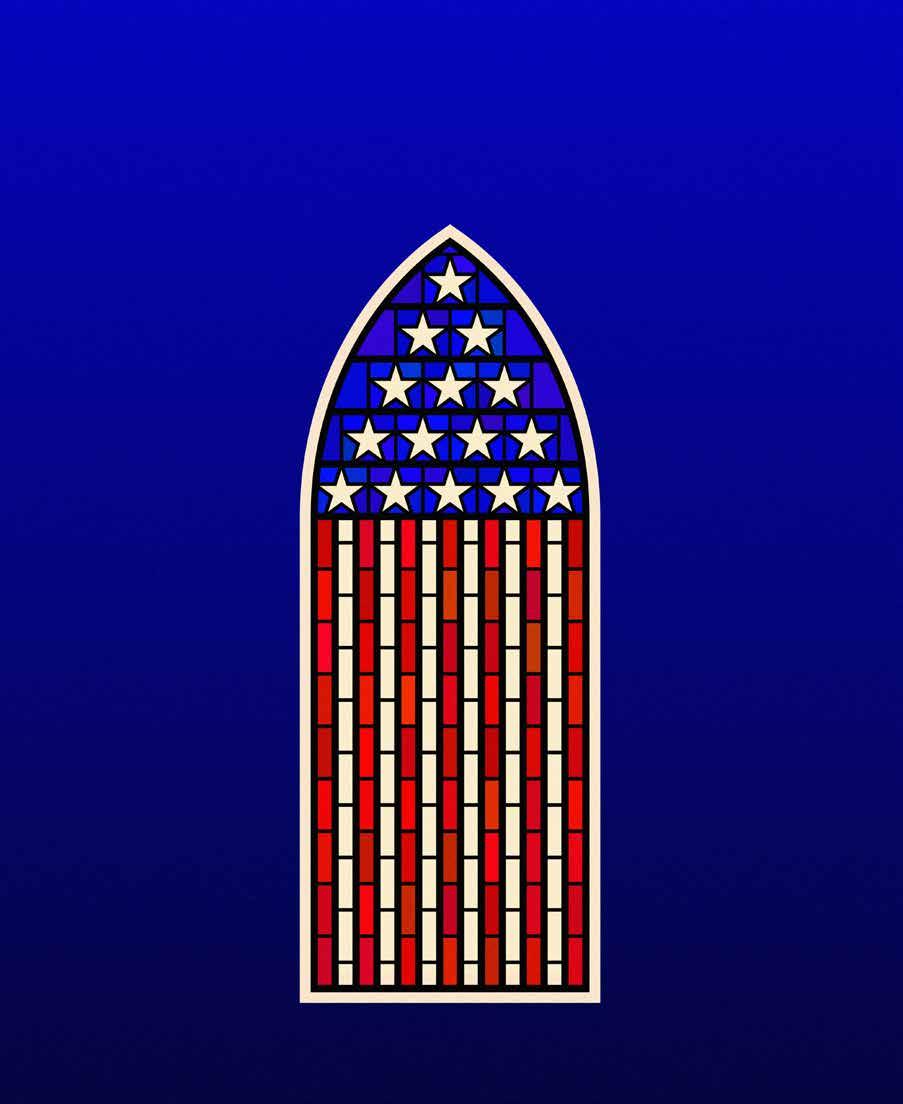

Nibbelink is a CanadianAmerican freelance illustrator based in California. She works with editorial, publishing and advertising clients around the world. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Reader’s Digest, NPR, The Boston Globe, Scientific American and Christianity Today. Her work appears on page 14.

Sadi is a former art director turned illustrator based in France. His digital creations explore the world of infographics, flat design, line works and digital lettering. Also known as blindSalida, his work has been published in Foreign Policy, Harvard Business Review, The National Law Journal, AdWeek and the Daily Telegraph. His illustration appears on page 42.

Kofoed is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville and a research fellow at the Institute of Labor Economics. His work has been published in the American Economic Review: Insights and the Journal of Public Economics, among other journals. His essay on controlling government spending is on page 68.

Gale is a photographer based in Portland, Oregon. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, The Atlantic and New York Magazine, and has been recognized by organizations such as The VII Foundation and The Alexia Foundation. His photographs exploring the impact of failed drug policies in Portland can be found on page 22.

Imet Mitt Romney for the first time last year in his Senate office in Washington. I had come to D.C. to meet with Utah’s congressional delegation, partly to introduce our new magazine, and partly to hear directly from them on the issues that concerned them most, both in the West and nationally.

After some small talk, Romney pointed to a map that hung on his wall, from floor to ceiling, as I recall. The map charted the rise and fall of the world’s most powerful civilizations. What was most remarkable about the map, Romney told me, is how for most of human history we have been ruled by tyrants. Democracy barely makes a blip.

I didn’t realize Romney often gave visitors to his office a version of this same speech until I read McKay Coppins’ new biography, “Romney: A Reckoning.” That’s how I learned that Romney became obsessed with the map after January 6. “More than once, he found himself staring at it alone in his office at night,” Coppins writes. “The Egyptian empire had reigned for some 900 years before it was overtaken by the Assyrians. Then the Persians, the Romans, the Mongolians, the Turks — each civilization had its turn, and eventually collapsed in on itself.” Democracy, in some ways, “is fighting against human nature,” Romney said.

When Romney voted to impeach President Donald Trump, he knew it would make him a pariah in his own party. As detailed in an exclusive excerpt from Coppins’ book (“The Making of Mitt Romney,” page 34) Romney wrote in his journal that not only would his party turn on him, but he would lose friends and find it hard to go anywhere without facing verbal abuse. He even worried about his family’s physical safety, eventually spending $5,000 a day to protect them — and himself.

And yet, Romney felt like he had to take a stand. It’s what his conscience demanded of him, Coppins writes, and what he felt his faith demanded. At the time, I hoped that even those who disagreed with

his vote would at the least admire someone for standing for their beliefs and principles, even if it cost him votes. But it seems to have cost him more, including his office. In September, he announced that he will not seek a second term. He has considered another presidential run as an independent or even creating a third party, but for now, those ambitions seem to be shelved. His future in politics, if there is one, is unclear.

This month marks one year until we elect our next president. At the magazine, we discussed what we could bring to the national conversation. With that in mind, staff writers Ethan Bauer and Natalia Galicza explore the ways faith animates the lives of the candidates, and how it might factor into policy decisions they would make in office (“Faith of the Candidates,” page 50). Luz Escamilla, Utah’s Senate minority leader, writes about how to improve civic engagement among minority voters (“Terms of Engagement,” page 13) and Chris Cillizza openly wonders why this will likely be yet another race between two candidates who don’t excite most voters (“Race to the Bottom,” page 72). We will of course continue to cover the presidential race in 2024, but consider this a primer.

I’ve thought often of that visit to Romney’s office, and his warning that America’s experiment in self-rule is an historical anomaly. I admire his stand and wish more politicians would act accordingly. But I’ve also come to understand that his vote was seen as a betrayal by party faithful. Many of my family members no longer see him as a real Republican and would have gleefully voted him out of office had he sought reelection.

What I hope we can agree on, however, is that democracy and the freedoms associated with it are both fragile and what has made America so special since its founding. And I hope the principles that undergird it — liberalism, pluralism, and an ability to respectfully disagree — will survive and even flourish.

EXECUTIVE EDITOR HAL BOYD

EDITOR JESSE HYDE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR ERIC GILLETT

MANAGING EDITOR MATTHEW BROWN

DEPUTY EDITOR CHAD NIELSEN

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

JAMES R. GARDNER, LAUREN STEELE

POLITICS EDITOR SUZANNE BATES

EDITOR-AT-LARGE DOUG WILKS

STAFF WRITERS

ETHAN BAUER, NATALIA GALICZA

WRITER-AT-LARGE

MICHAEL J. MOONEY

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

LOIS M. COLLINS, KELSEY DALLAS, KYLE DUNPHEY, JENNIFER GRAHAM

ART DIRECTORS

IAN SULLIVAN, BRENNA VATERLAUS

COPY EDITORS SARAH HARRIS, VALERIE JONES, LOREN JORGENSEN, CHRIS MILLER, TYLER NELSON

DESERET MAGAZINE, VOLUME 3, ISSUE 29, ISSN PP325, IS PUBLISHED 10 TIMES A YEAR BY DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO., WITH DOUBLE ISSUES IN JAN/FEB AND JULY/AUGUST. SUBSCRIPTIONS ARE $29 A YEAR. VISIT DESERET.COM/SUBSCRIBE.

PUBLISHER BURKE OLSEN

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER

DAVID STEINBACH

VICE PRESIDENT MARKETING

DANIEL FRANCISCO

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT SALES TRENT EYRE

VICE PRESIDENT SALES SALLY STEED

PRODUCTION MANAGER MEGAN DONIO

OPERATIONS MANAGER

BRITTANY M C CREADY

DIRECTOR OF CIRCULATION SYLVIA HANSEN

THE DESERET NEWS’ PRINCIPAL OFFICE IS 55 N. 300 WEST, STE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. COPYRIGHT 2023, DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA.

PROPOSED AS A STATE IN 1849, DESERET SPANNED FROM THE SIERRAS IN CALIFORNIA TO THE ROCKIES IN COLORADO, AND FROM THE BORDER OF MEXICO NORTH TO OREGON, IDAHO AND WYOMING. INFORMED BY OUR HERITAGE AND VALUES, DESERET MAGAZINE COVERS THE PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF THAT TERRITORY AND ITS INTERSECTION WITH THE BROADER WORLD.

The SEPTEMBER issue examined the costs, quality, graduation rates and benefits of a higher education, revealing the challenges and solutions for an opportunity that has become out of reach for many (“Restoring the Promise of American Education”). Several essays explained what religious colleges and universities bring to the table in providing incentives for students to complete an affordable education that opens doors to the future. “It is important for other universities to understand the efforts of religious universities, not only because there are so many important innovations happening, but also because it validates religious mission as a recognized organization structure in higher education,” tweeted the American Council on Education, whose scholars contributed several pieces to the issue. Readers took a particular interest in how to cover the cost of a college education and who should pay for it. Dan Creamer argued for a free education. “There are some things that a progressive, fair and just society should never monetize and that includes education, justice and health care. To make profit centers of any of these basic needs is to invite the discord the profit motive causes when it becomes the priority.” But Jack Beckman responded that a no-cost education also invites trouble. “Your claim that a ‘progressive, fair and just society’ shouldn’t monetize education, but do we want a progressive, fair and just society? Who defines what that is? Such are not clearly defined, and therefore dangerously changeable at the whim of whoever has the levers of power at the time.” Writer Tad Walch and photographer Spenser Heaps traveled to Kenya to report on the impact of a program that brings education to remote areas of the world (“The Pathway”). Readers who have been involved in the BYU Pathways program praised the story for reminding them of their experiences as Pathways teachers and students. “It has given hope of higher education to many intelligent students barred from achieving their potential due to financial instability,” Nicholas Sadaka, now enrolled in BYU-Idaho, shared on Facebook. Alexandra Rain wrote about the mentorship and personal care secondary schools provide students living in poverty (“The Safety Net of School”). Salt Lake City school board member Bryan Jensen said it is important to make communities aware of “successes experienced by ‘doing something.’ Our public schools are faced with incredible challenges, and it is wonderful to recognize what students, teachers, parents, volunteers, administrators and community leaders are accomplishing.” Lois Collins’ interview with Galena Rhoades, director of the University of Denver’s Family Research Center, found common ground with reader Robert Goodrich on the idea that the key to a successful relationship is commitment. Reflecting on his courtship, marriage and the little money he and his wife had to live on, he wrote, “but the real secret to happiness is I was with her. After 55 years she still amazes me.”

“There are some things that a progressive, fair and just society should never monetize and that includes education, justice and health care.”

We have 11 perfect venues for your event.

BY LUZ ESCAMILLA

As we approach Election Day this November and another presidential election year, let’s take a moment to think about civic engagement and the profound impact it has on our nation’s economy, social fabric and future position in the world.

The definitions of civic engagement are many, but we can all agree that a healthy democracy needs all individuals to have a basic understanding of how government works and how to access information on policy and other issues that affect them, their loved ones and their neighborhoods. We have an obligation to ensure our democratic processes and necessary resources and information are fully accessible for all to participate in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner.

Civic engagement is the fundamental machine that facilitates healthy, two-way communication between citizens and their elected leaders who oversee our government. The reciprocal dialogue grown out of civic engagement allows for inclusive and indispensable public discourse on policy issues across the board.

Civic engagement during an electoral process may look different at an individual level versus a group level. For example, casting a vote, placing a bumper sticker on your car, planting a yard sign or volunteering on a campaign are some of the different ways individuals engage during elections. At the group-level, engagement takes a different shape as forces assemble for “collective action” on a particular issue or candidate. All these forms of participation encourage a healthy electoral system, democracy and a nationwide exchange of goals, concepts and dreams for the future.

But what happens when a portion of the electorate doesn’t engage, and what can we do to change that? Talking about civic engagement at a basic level requires a short trip through time to remember the evolution of voter participation in our nation’s history,

including the disenfranchisement of Black Americans and other minority groups and intentional decisions to suppress the vote.

In 1870, the 15th Amendment to the Constitution guaranteed that the right to vote could not be denied based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This amendment complemented the 13th and 14th amendments, which abolished slavery and guaranteed citizenship to Black Americans, respectively. Women finally received the right to vote with the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 historically expanded voter registration and voter participation. The fight is not over. Many are the battles to get us closer to true representation; one of those battles was won this summer with the Supreme Court decision in favor of Black voters in a congressional redistricting case in Alabama.

When minority communities engage and participate in electoral politics, the bones of our democracy get stronger through more comprehensive representation in government. Diverse input helps us better confront our unique challenges through policies that embrace inclusion and our shared ideals of prosperity. Who better to advance policy decisions on issues rooted in systemic inequality than people who have been disproportionately impacted by them? As our demographics continue to shift, civic engagement fosters representation for our children by leadership they can identify with and who make them feel like it’s possible to dream.

A fully engaged community is a fully vested community. Empowering people to participate in the processes that decide who represents them gives them a sense of belonging and hope. Minority voices and communities have developed an incredible resilience but currently struggle to find optimism amid a divided nation that, in many instances, attacks the very sense of who they are. Carrying the disproportionate weight of poverty, homelessness, negative physical and mental health outcomes, environmental hazards and other social determinants of health are structural burdens that do not encourage confidence and trust in the value of civic engagement.

More and more of our population identifies as a racial and ethnic minority community. They will be the future workforce and leaders of our nation. It is in the best interest of ALL to create a space where they can fully participate in our democratic system. Let’s address the issues that matter to them, include them culturally and linguistically in healthy two-way communication of civic engagement and remove barriers for them to participate, which will strengthen our democracy with true representation.

As stated by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” Our democracy awaits ALL to participate, and it is up to us to speak up when barriers are constructed to prevent that.

SEN. LUZ ESCAMILLA IS MINORITY LEADER IN THE UTAH SENATE AND PAST DIRECTOR OF THE STATE OFFICE OF ETHNIC AFFAIRS.

MORE THAN HALF a century has passed since a candidate from outside the Republican or Democratic parties has won a single state in a presidential election (George Wallace in 1968). And yet, according to recent Gallup polling, dissatisfaction with America’s two-party system is at an all-time high. Could an alternative be the answer to our gridlocked and hyperpartisan era? Political scientist Lee Drutman thinks so. In his book “Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop,” Drutman argues that for most of our history the two parties had significant ideological overlap, which worked well in “our compromise oriented political institutions.” Over time, however, the two parties have come to represent distinct and warring visions of American identity, with each claiming to represent the majority. How did we get here? And would an alternative to the two-party system be better for democracy?

—Jesse Hyde

The founders were suspicious of political parties, favoring instead a government run by elites. In fact, George Washington was so alarmed by the rise of parties during his second term (Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists and Thomas Jefferson’s Republicans) that he dedicated part of his

farewell address to condemning them as a path to despotism. John Adams went even further, arguing that “a division of the republic into two great parties … is to be dreaded as the greatest political evil.” Today, Washington’s warning of factions seeking to dominate the other seems prophetic.

By 1824, this view had shifted and political parties were seen as vital to giving voice to the people. The rise of political parties resulted in a far higher level of engagement in politics: In 1824, only 26 percent of eligible voters (property-owning white men) voted. By 1840, the turnout was 80 percent (owning property was eliminated as a requirement to vote in

1828). And yet it wasn’t until the 20th century that the parties began to resemble what we know them as today.

While the founders may have been suspicious of political parties, the general consensus today is that they are essential institutions of democracy. As former Brigham Young University political science professor David

Magleby has argued, political parties organize democracy in that they recruit and nominate candidates and stand for a particular view of the role of government. Research has also shown that those most involved in political parties are also best informed on issues affecting their communities and nations.

The most successful third-party nominee was Theodore Roosevelt. Disillusioned with his successor, Howard Taft, he ran against him for the Republican nomination in 1912. While Roosevelt won more votes in the primary, Taft already secured enough delegates in the South to win the nomination. Roosevelt formed the breakaway Progressive Party, and eventually carried six states and nearly 30 percent of the popular vote, becoming the only third-party candidate to finish second in a presidential election. Ross Perot got almost one-fifth of the popular vote in 1992, preventing Bill Clinton and George Bush from winning a majority in any state except Arkansas.

One solution, even in a two-party system, is ranked choice voting. Countries like Ireland and Australia have used it for years and it’s recently gained popularity in the U.S., where it has been adopted for some elections in 18 states, including Utah. Unlike the winner-take-all method of our current system, ranked choice voting allows voters to select candidates in order of preference. Proponents of ranked choice voting say it can reduce polarization: Rather than promoting extremes and ideologues as our current primary system often does, it favors consensus candidates. This, in turn, could lead to more civil elections because candidates are encouraged to form coalitions.

“THE ALTERNATE DOMINATION OF ONE FACTION OVER ANOTHER, SHARPENED BY THE SPIRIT OF REVENGE NATURAL TO PARTY DISSENSION … IS ITSELF A FRIGHTFUL DESPOTISM.”

GEORGE WASHINGTON, FAREWELL ADDRESS, 1796

With just two main parties and a “firstpast-the-post” (single winner plurality), the United States is a global outlier. Most of the world’s democracies are multiparty, and most hold elections using proportional representation. Advocates of the multiparty system say it’s more likely to result in higher voter

turnout and better representation of political and ethnic minorities. “In multiparty democracies, parties do not claim to represent true majorities,” Drutman writes. “They promise to represent and bargain on behalf of the different voters and issues they represent.”

Denmark has over a dozen political parties in the Danish Parliament — from The New Right to the Green Left. Brazil has over 30 parties in its National Congress. The Netherlands has a party called 50Plus, which caters to pensioners. Proponents of a multiparty system say that because no two parties are likely to win an election with so many choices, elected representatives must rely on coalitions to gain a majority. This encourages parties to work together and typically brings them closer to the center.

The biggest strength of a multiparty system — diversity of representation — is also one of its greatest weaknesses because it gives small factions disproportionate influence and a path to enter the mainstream. In France, the far-right National Rally went from six to 89 seats in the most recent parliamentary election, making it the most unified opposition to President Emmanuel Macron. For every party that caters to environmentalists or libertarianism, there’s a party with extremists who want to put an end to democracy in favor of fascism.

AMERICA HAS ALWAYS had a tortuous relationship with the media. “Our liberty depends on the freedom of the press,” Thomas Jefferson observed. But later, he also wrote that “nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper.” In 2020, a Gallup/Knight Foundation poll found that 81 percent of Americans believe the media is “critical” or “very important” to democracy. That doesn’t mean they trust the reporting. Skepticism is especially pronounced among conservatives: Pew Research Center found that Republicans’ trust in national news organizations collapsed from 70 percent in 2016 to just 35 percent in 2021. Many cite a liberal bias, echoing certain campaign slogans. Are their suspicions well founded? Or is something else going on here? —Ethan Bauer

The media’s liberal bias is self-evident to conservative observers. They coddle Democrats and endorse liberal ideas but target Republican politicians and conservative values with unfair and unbalanced scrutiny. Driven by both personal beliefs and profit motive, the media seems to be taking one side and vilifying the other.

Consider the industry’s political makeup. Journalists are four times more likely to be registered Democrats than Republicans, and multiple studies have found them more likely to donate to Democrats. “Even reporters and editors who imagine themselves to be fair,” columnist Mike Rosen of Colorado wrote in February, “see the world through their subjective lens.”

But news is a business, and nothing sells online like outrage. So mainstream outlets lean into reliable tropes like “wicked right-wingers getting their just desserts or the plights of innocents suffering because of right-wingers’ behavior,” wrote former Fox News political editor Chris Stirewalt in Deseret Magazine last November. Examples include vaccine critics catching Covid-19 and ending up on ventilators or immigrant children separated from their families under the Trump administration. “The path to profitability and survival for much of the news business now relies on products that are mostly either superficial fluff or distortions that exploit and deepen our country’s worsening political alienation.”

Many conservatives cite the research of economists Tim Groseclose and Jeff Milyo — now at George Mason University and the Cato Institute, respectively — who in 2003 found evidence of liberal bias by tracking media citations of left and right-leaning think tanks. Even moderates like Sen. Mitt Romney have had verbal missteps taken out of context and pilloried, especially during his 2012 presidential campaign. “It just shows the level of amplification, of blowing certain things out of proportion,” says conservative commentator Evan Siegfried.

One study published in 2022 focused on 25 conservatives and found that while the group was generally hostile toward the press, “they were not primarily upset that the media get facts wrong, nor even that journalists push a liberal policy agenda,” the study’s co-authors observed in The Conversation. “Their anger was about their deeper belief that the American press blames, shames and ostracizes conservatives.”

Liberal bias in the news is a myth. But reporters face very real hostility that arises from misunderstandings about the industry and misguided expectations, used as levers by political operators and even some media outlets.

Reporters aren’t autonomous actors, but part of a system populated with editors, publishers, lawyers, shareholders and advertisers. Their work is scrutinized for factual accuracy, legal liability and reach. Each story represents an investment, expected to yield certain results. A story is deemed “newsworthy” based on its relevance to society, human interest or draw for readers. Editors and producers manage the overall mix, while corporate owners determine an outlet’s market position.

That leaves little room for journalists to plant flags. A 2020 study co-authored by BYU-Idaho political science professor Matt Miles found that “journalists’ individual ideological leanings have unexpectedly little effect on the … early stage of political news generation,” where story subjects are selected. Instead, he concluded, the perception of partiality arises from readers’ own biases and disappointment when their beliefs are not confirmed. “They’re calling (stories) liberal and conservative, when really, it’s just that this story isn’t talking about the people I like in the way that I like.”

Perhaps Americans have grown accustomed to a new kind of news. Deregulation allowed outlets like MSNBC to take up partisan positions — a strategy pioneered by Fox News, a standard-bearer for claiming “liberal bias.” This may be a brand strategy, but it also shapes the audience. According to Lehigh University political science professor Anthony DiMaggio, a combination of national surveys showed that “the strongest evidence of indoctrination was observed among consumers of conservative media,” with Fox News watchers hewing to the party line more than the audiences of CNN or MSNBC

Politicians can find such claims useful. “If you can get people to believe that your side is not biased, only the other side is biased, because they’re the ones who are wrong,” DiMaggio writes, “then you’ve won the rhetorical game.” What’s clear is that Americans need to boost their media literacy to navigate an increasingly complex landscape, perhaps by starting with a walk on the other side.

BY NATALIA GALICZA

Shalon Irving tried to do everything right. She didn’t miss a single doctor’s appointment during her pregnancy. She ruminated for days on a birthing plan to account for every conceivable variable: the music that’d play during childbirth, the guests allowed in the delivery room, the conversations they could and could not have in that space. She’d even tasked her mother with preemptively sterilizing the already sterile hospital room — just to err on the side of caution.

Irving understood that even the smallest of details could drastically alter health outcomes. She served as an epidemiologist for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and, prior to that role, as lieutenant commander for the U.S. Public Health Service. Her work focused on invisible dangers, like structural inequality and trauma, and their impact on patients’ well-being. So holding her daughter Soleil in her arms on January 3, 2017, against all odds, perceptible and otherwise, became what she considered her greatest accomplishment.

But exactly three weeks after she gave birth, Irving suffered a cardiac arrest. She’d been experiencing high blood pressure, weight gain, swelling and other symptoms — all of which she relayed to her health care providers over numerous appointments. Her last doctor’s visit took place hours before her heart attack. Irving tested negative

for blood clots and preeclampsia, so she was sent home with blood pressure medication despite her insistence that something remained wrong. She turned out to be right. Emergency responders brought her to a local hospital after Irving collapsed to place her on life support. She died four days later.

Despite her caution, education and excellent insurance, Irving fell victim to a statistical pitfall that has long plagued the American health care system. More mothers die of complications related to pregnancy in the United States than any other high-income

“WE KNOW EXACTLY HOW THIS COULD HAPPEN, BECAUSE IT’S BEEN HAPPENING TO SO MANY FAMILIES AROUND THE COUNTRY FOR DECADES, AND IT’S UNACCEPTABLE.”

country in the world. Most of those deaths occur anywhere from a week to a year after birth. And they’re growing more frequent. The CDC published a report earlier this year with data that places the maternal mortality rate — the number of maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births — at 32.9 as of 2021. The number is up from 23.8 the year

before and 20.1 two years prior. For Black women like Irving, the current rate more than doubles at 69.9 deaths.

A confluence of ailments is behind the lapse in maternal care for Black women. An estimated 36 percent of all counties in the U.S. are areas with little to no access to maternal care — two-thirds of which comprise rural counties. Higher rates of predisposition to conditions like hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity also account for some of the disparity. Though more prevalent and nebulous are the social issues at play. New research points to how chronic stress caused by exposure to discrimination or racism, generational inequities that lead to a lack of health care access and implicit bias imposed by health care practitioners can widen the gap for Black mothers. A version of that disparity had already been documented at the time of Irving’s death six years ago, though with far less public understanding. “Shalon’s death was devastating. I remember going to her funeral, and the director of the CDC came and said, ‘We don’t know how this could happen,’” says Congresswoman Lauren Underwood, a Democrat from Illinois and a friend of Irving’s from graduate school. “We know exactly how this could happen, because it’s been happening to so many families around the country for decades, and it’s unacceptable.”

Two years after the funeral encounter, Underwood co-founded the Black Maternal Health Caucus with North Carolina Rep. Alma Adams and then-Sen. Kamala Harris, both Democrats. It’s since grown into one of the largest bipartisan caucuses in Congress and has led to the introduction of the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, a package of 13 bills proposed in both the House of Representatives and Senate that aims to end America’s maternal mortality crisis. And while it’s gained little traction since its debut in 2020, a perfect storm of restored national attention, newly dismal data points and the act’s formal reintroduction in May could help prompt a new trajectory for nationwide maternal care. One where invisible dangers, much like what Irving devoted and lost her life to, no longer take hold of health outcomes. “This is not a partisan issue,” Underwood says. “This is about taking action to save moms’ lives.”

MID-19TH CENTURY MEDICAL journals and Southern hospitals where doctors treated enslaved people proved foundational to establishing a sense of otherness between Black and white patients. Deirdre Cooper Owens writes in her book “Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology” that “physicians’ medical writings … modeled how to treat and think about black and white women and their perceived differences based on biology and race.” This included the belief that Black women had heightened fertility and an abnormally heightened pain tolerance, justifications used to exploit enslaved women as so-called “breeders” and subjects for medical experiments without anesthesia.

The men behind those experiments included James Marion Sims, dubbed the father of gynecology. And the same sentiments that propelled them persist even after hundreds of years. A 2016 study from the University of Virginia found a majority of more than 200 surveyed medical students believed Black Americans have thicker skin than whites, and a minority even

believed Black Americans’ nerve endings are less sensitive.

These responses influence the future doctors’ likelihood to offer a patient treatment, which correlates with the 40 percent of Black adults surveyed by Pew Research Center last year who say they’ve had to speak up to receive proper care — the most cited negative experience in the survey. “We’ve got to start listening to folks that tell you that something is not right,” says Kay Matthews, founder of Shades of Blue, a nonprofit focused on providing mental health resources for Black mothers. Matthews began her work after she experienced a lack of medical support as she suffered postpartum depression after losing her daughter to a stillbirth. “I went way too long without being able to get assistance and care because it was something that people were unfamiliar with,” she says. “We deserve to deliver our babies and go home and continue our lives and it’s just not happening.” Matthews’ organization co-sponsored the Moms Matter bill in the Momnibus act, focused on mental health equity.

They also illustrate why the Momnibus act places emphasis on addressing social determinants of health through research of disparities and tailored training for incoming health practitioners. Certain biases that may be embedded into the origins of present health care systems can appear innocuous or outdated while still posing centuries worth of harm. “When we think about the workforce and who is entering the health care sector, these are the people that are delivering the care for women that are having babies,” says Anuli Njoku, lead author of the academic paper “Listen to the Whispers before They Become Screams: Addressing Black Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in the United States,” published in February. “Having more curriculum about these issues of implicit bias and how to improve cultural humility could be one way to address unconscious bias.”

Medical programs that offer students specialized training to understand social determinants of health for minority groups and how to respond with equitable care

already exist and show progress. But there’s a demand for more. A joint effort by the American Public Health Association and the Council on Education for Public Health in 2021 echoes the need for increased research on not just quantifying disparity but reducing its harm, as outlined in the Momnibus bills. The study concluded “more research is needed to document how to educate public health students on the roots of the health issues they will address in their careers.” Especially when so much can compound to produce said harm in the first place. “There are nonmedical factors that are ingrained in society,” Njoku says. “Structural racism is a driver of those factors that affect one’s access to education, to housing, income, and how those factors really play a role in where these women may be.”

Which speaks to why the bulk of the Momnibus package includes pieces of legislation to not only fund training and data, but community-based organizations, a diversified maternal care workforce, mental health resources, accessible telehealth models for all appointments, promoting vaccination awareness, and more. One bill that previously comprised that package, the Protecting Moms Who Served Act, was signed into law by President Joe Biden two years ago. The act ensures the Department of Veteran Affairs maintains a coordination program to connect veterans seeking external pregnancy or postpartum care with providers. “Whether we’re talking about challenges and gaps in rural health care, disparities that are seen in a variety of racial and ethnic groups, there’s resources in the Momnibus that help all moms have better pregnancy outcomes,” Underwood says. States like California have also passed Momnibus legislation in recent years, but the goal of enacting the entire framework on a federal level remains unmet. At least for the time being. And as more high-profile athletes, celebrities and public figures come forward about their close calls, as more years inch by since Irving’s fatal collapse, all the more light is shed on solutions. A steady burn, almost as if to rival her daughter Soleil’s namesake.

In the mind of a child with autism, conversation can be overwhelming. But at Brigham Young University, students use an animated social skills coach to help kids, like Scout, find their strengths and have meaningful interactions that build their confidence.

Learning by study, by faith, and by experience, we strive to be among the exceptional universities in the world and an essential university for the world.

BY ETHAN BAUER

Wherever he goes, Jordan Gale sees photographs. It’s his life’s work, after all, to capture compelling moments through the lens of a camera. So as the blue city bus rolls across Portland, Oregon, his eye catches details that tell stories. The yoga studios and hipster markets of his neighborhood embody the local stereotype. Stretches of blocky apartments and neon-sign restaurants reflect growth and prosperity. But when the bus turns, the scenes get a little more bleak. Broken-down RVs, off-brand motels and clusters of tents along 82nd Avenue speak of a city in crisis.

Portland is not alone, particularly in the West. An epidemic is raging from Seattle to Los Angeles, Las Vegas to Denver. Cities are overwhelmed with homelessness and addiction, which can overlap visibly on the streets. When authorities take down one colony in Salt Lake, another pops up nearby, in a public park or on a hillside. Nobody has found the answer, but Portland’s troubles are particularly complex, and seem to be getting worse. While Oregon ranks fourth in the nation in homelessness, overdose deaths have spiked in the City of Roses, from 90 in 2020 to 159 in 2022 and forecasts of 300 by the end of this year.

Gale moved here in 2021 from New York, where he’d grown tired of covering bike theft and mayoral campaigns for local metro sections. Maybe he could take on heftier

issues out west, in a city with less competition. He’d grown up in Iowa but wasn’t what you’d call sheltered. Still, what he saw here outstripped anything he’d ever seen. “It was shocking,” he says. He has thick brown hair, a stubbly mustache and a smattering of tattoos. “You could walk down any street and there’s tents and encampments and people smoking fentanyl off tin foil. You can’t ignore that.”

So he shouldered a camera bag and headed across town. Soon he was making this

TODAY, OREGON TREATS LOW-LEVEL DRUG POSSESSION AS A VIOLATION THAT CARRIES A $100 FINE, NOT UNLIKE A TRAFFIC TICKET. FINES CAN BE WAIVED WITH A PHONE CALL.

20-minute bus ride several times a week, spending upward of 15 hours a day along 82nd Avenue. It was grueling, emotional work, building relationships with people living on the streets and the organizations trying to help them. He built up a striking body of work, black-and-white photographs of homeless folks and their neighbors, police, EMTs and drug users. Today, that work has appeared in The Nation, The Atlantic and The New York Times, drawing national

attention to an intractable problem and the legal change that seems to be making matters worse. Now the bus hisses to a stop, and he steps back into the fray.

AS GALE WRESTLED with tragic scenes of overdoses and desperate people, he also tried to understand what was behind it. His research led him to Ballot Measure 110, passed in 2020 by 58 percent of Oregon voters. The measure decriminalized possession of small amounts of illicit drugs and directed $100 million per year in tax revenue from the cannabis industry to addiction recovery programs. Supporters hoped this would get more users into treatment, curtailing crimes of desperation and reducing the burdensome costs of incarceration. Instead, the streets are overwhelmed.

Oregon was not the first to try a similar approach. The Biden administration has adopted a philosophy of harm reduction, treating drug addiction as a public health problem rather than a criminal issue. Even conservative Utah passed HB348 in 2015 to try funneling convicted drug users into rehabilitation rather than jail. Internationally, Portugal pioneered the idea, decriminalizing heroin amid a severe wave of abuse in 2000, part of a broader effort. Measure 110 followed that model, but went further than any similar American law.

Today, Oregon treats low-level drug

FIRST RESPONDERS CHECK THE VITALS OF AN INDIVIDUAL WHO RECEIVED NARCAN TO COUNTERACT A SUSPECTED FENTANYL OVERDOSE.

CORRY JOHNSON WAITS AS FIRST RESPONDERS TEND TO HER FRIEND SUFFERING FROM A SUSPECTED FENTANYL OVERDOSE.

MEMBERS OF THE CENTRAL CITY CONCERN OUTREACH TEAM PASS OUT NARCAN WHILE MAKING THEIR MORNING ROUNDS IN THE OLD TOWN DISTRICT.

“THE BASIC IMPULSE TO TRY TO FIND WAYS OTHER THAN INCARCERATION TO MOTIVATE CHANGE, I THINK IS A GOOD ONE. BUT LIKE ANYTHING ELSE, YOU CAN GO TOO FAR.”

possession as a violation that carries a $100 fine, not unlike a traffic ticket. Fines can be waived with a call to the state’s treatment referral hotline. This hard left turn highlights a confusing trend across the country, as more states legalize marijuana and other substances or soften their stances. Meanwhile, the federal war on drugs continues and the minimum mandatory prison sentences introduced in the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 remain largely intact. With three times more drug arrests in 2019 than 1980, it’s hard to say that problem is going away.

The opioid crisis, specifically, is still getting worse, six years after the federal government declared it a public health emergency. The news cycle has moved on to lawsuits and settlements with opioid manufacturers, distributors and drug store chains, more typical of an issue reaching its resolution. Netflix has released a series called “Painkiller,” inspired by the Sackler family, whose company created OxyContin. But drug overdose deaths increased by 14 percent from 2020 to 2021. Three-fourths of those deaths involved opioids, 88 percent of which were synthetic, like fentanyl.

No photographer could change any of that, so Gale set out to put a human face on a dire situation, to inspire empathy and perhaps command attention as the problem kept getting worse.

THE BUS RUMBLES away, leaving Gale on a sidewalk near a kaleidoscope of tents. A crowd is gathering outside the Saints Peter and Paul Episcopal Church, in a parking lot tucked between two modest structures with slate blue siding and triangular rooflines, across 82nd Avenue from a strip mall and a used car lot. Every Sunday, the Rev. Sara Fischer hosts a dinner for the community, hoping to make the parish “a dynamic bridge between two parts of Portland”

— presumably the part that lives on the street, and the part that doesn’t.

Gale knew he had to earn the trust of the streets. Vulnerable as their lives are, homeless folks tend to be wary. Some had felt burned by others with cameras, social media types looking for salacious stories that could go viral. Some feared he would shoot without their permission and invade their privacy — a sticky question when one lives in a public place. He even had to get vetted by drug traffickers who work in the area. But many others welcomed him warmly. Some of them frequent this dinner, a rare social gathering for this particular demographic.

On a balmy night in August, fare consists of pizza, soda and bottled water. People come and go, but more appear to be homeless than typical congregants. Gale had come up against addiction before, on a yearslong project documenting his own roots. In Iowa, towns are more spread out, the crisis hidden in homes, basements and cars. So he learned to develop relationships with potential subjects.

That means people like “Coach,” a 52-year-old man in a well-worn track suit, homeless since a “bad divorce” six years ago. He could no longer make rent on his wages at the Montavilla Community Center, where he’d worked for 20 years, so he stays out here with a white terrier mix named Uno. The trouble with living among addicts, he says, is their desperation leads to fights and muggings. He’s lost his motorcycle, his bicycle and his Chevy Silverado — bought with the last of his savings — all stolen or confiscated. “People will steal from you, even if they’ve known you your whole life,” he says. “Fentanyl made it even worse.”

THROUGH THE VIEWFINDER of Gale’s Fujifilm DSLR, a slender man named Noah, with

shaggy black hair and a gray-flecked beard, presses the flame of a handheld torch up against a thin, straw-like tube — a fentanyl pipe undergoing a cleaning. Gale snaps a photo. The man tells him he wanted to be an English teacher, until an adolescent addiction to OxyContin spun him off into years of struggles with heroin and trauma. He relapsed during the pandemic and turned to fentanyl when he couldn’t find heroin. Now he lives in fear of that drug’s gut-wrenching withdrawals. “Someone is going to do whatever it takes to make that (feeling) go away,” he says.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid, similar to OxyContin, but exponentially more potent — 100 times more than morphine and 50 times more than heroin. Developed as an anesthetic in 1959, it’s still used in clinical settings, including some epidurals administered to mothers in labor. But around 2011, amid measures intended to combat opioid abuse, the Drug Enforcement Administration tracked an uptick in illicit fentanyl. First it was stolen or manufactured in small labs that law enforcement quickly shut down. Later it surfaced for sale on the dark web, shipped in small packages

directly from Chinese factories. That was before Mexican cartels moved in as highly efficient bulk intermediaries.

By 2020, Portland was flooded with familiar pills at cut-rate prices. “And what turned out was they no longer contained oxycodone,” says Joe Bazeghi, director of engagement at Recovery Works NW “These were just fentanyl with binding agents pressed to look like oxycodone.”

At first, users didn’t know what they were getting, but by the time Measure 110 rolled out, fentanyl had obliterated the competition. Suddenly, it was the only opioid on the street. Its supercharged high wears off sooner and creates a stronger dependency so users typically need another dose every two hours just to avoid withdrawals, which are harder to treat.

“Our old tools are significantly less effective, and people are dying at rates that we’ve never seen before,” Bazeghi says.

Funded by Measure 110, Recovery Works

NW is the first facility in Oregon to specialize in treating fentanyl withdrawals. With room to treat up to 1,200 cases per year, it represents an 18 percent increase in the city’s capacity. Time will tell whether that is enough, in Portland or elsewhere, because fentanyl “is not an Oregon problem,” Bazeghi says. “It’s occurring throughout the country.”

Nationwide, the number of overdose deaths each year has risen by 40,000 since 2019, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, driven largely by fentanyl. Its lethal concentration in small packages has also made it harder for law enforcement to detect. “All the illicit fentanyl Americans consume in a year,” says Keith Humphreys, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral science at Stanford, “would fit on one truck.”

AFTER POLICE SWEEP his encampment,

Noah gathers what he can carry and walks. Gale finds him on a residential street and lines up a perfect shot. But as he adjusts the camera settings, a woman opens a nearby door. “You’d better not be setting up your camp right there,” she says. “We paid too much money for these houses for you to ruin the value.” This is the kind of attitude Gale hopes to change with his work. Policy is another world.

Critics say Measure 110 lacks sufficient incentives or deterrents to push people into treatment. Law enforcement leaders call the citation system useless. Even rehab professionals who value the increased funding (Oregon ranks last in the nation in access to drug treatment) say something is missing. “Instead of harm reduction, it should be health promotion,” says Jerrod Murray, executive director of Painted Horse Recovery. Saying “we’re just gonna give you some bubble pipes, and we’re gonna give

you clean needles, and everything’s gonna be just fine,” he says, makes recovery even more difficult.

Humphreys agrees. “The basic impulse to try to find ways other than incarceration to motivate change, and to try to not make the punishments for drug abuse worse than drug use, I think is a good one,” he says. “But like anything else, you can go too far.” Measure 110 lacks an enforcement mechanism analogous to Portugal’s dissuasion commissions, which can push people into treatment using creative discipline, like suspending their license to practice a trade. Oregon “left that out,” Humphreys adds, “so it’s not surprising they got the results that they did.”

In these debates, Gale worries that frustration can spiral into cruelty, while addiction and homelessness devolve into abstract concepts. But on 82nd Avenue, they’re concrete realities, alongside the

scourge of mental illness and the cycle of rehab and relapse. But life here is also more complex than that, and human. “There’s so many layers to it,” Noah says. “There’s still people falling in love. There’s still people trying to survive.”

It’s dark when the photographer steps back on the bus, his memory cards loaded with images to process and edit, faces he wants you to see. Gale calls this “the hardest part,” trudging past the galleries and cafes of his neighborhood, “going back to my comfortable living situation.” Some nights, unable to rest, he sits on his stoop and thinks about some incident he’s witnessed, some burden he cannot share. Sometimes he feels guilty, as if he were taking advantage. Sometimes he thinks about the law and the inhumanity of public discourse. “I think we naturally just choose to simplify things,” he says. “And you’ve gotta tell yourself that that’s not the case.”

“THIS IS NOT AN OREGON PROBLEM. IT’S OCCURRING THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY.”

BY LAUREN STEELE

When missionaries, settlers and pioneers pushed West, the mountains, valleys, rivers and peaks became subject to their sentiments. Names given by Native American tribes were forgotten or never learned, and trying experiences were distilled into lamenting designations. Such was Disappointment Creek.

The creek has promising beginnings atop the peak of Lone Cone in the San Juan Mountains, an extinct volcano that soars over 12,000 feet into the Colorado sky. Its headwaters chase the sun westward for 40 miles. Along the way, the arid ground siphons it, and what’s left is spoiled with alkali and other contaminants, according to author Wilma Crisp Bankston. “In summer and fall, before the water reaches the lower valley, it is often bitter and yellow,” she wrote in the 1987 book, “Where the Eagles Winter.” That is, if it reaches the lower valley. Bankston’s research into the oral folklore of the area found that the creek’s name is said to have come from a party of early surveyors who were tasked with mapping that lower valley. The day was hot — late summer in the high desert — and the crew had run out of water. Following the wisdom of aspen and spruce trees to the banks, they expected to find a long, cool drink. But they found the creek as dry as a bone.

Most years, Disappointment Creek doesn’t make it very far. But when it does,

it intersects with a river, one once called El Rio de Nuestra Señora de Dolores by Spanish friars in the 1700s. That Spanish name translates to The River of Our Lady of Sorrows. But today, we simply know it as the Dolores. “The Dolores River is much beloved in this area, but it’s also kind of a tragic story because in times of drought,

THE WASATCH RANGE IN UTAH RECEIVED OVER 900 INCHES THIS WINTER. THE SIERRAS WELCOMED BACK LONG-LOST LAKES. NEVADA’S BASIN AND RANGE REGION SAW RECORD SNOWPACK. EVEN AREAS OF ARIZONA REACHED ABOVE-AVERAGE FOR THE YEAR.

it frequently runs virtually dry,” says Teal Lehto, a river guide and the water rights activist behind the Western Water Girl platform. “It only runs once every two or three years. Sometimes it’s up to a decade between runs.”

The Disappointment Valley and the Dolores River’s annual ritual of scarcity have served as a visible barometer for the

West’s water shortages in recent years. It has exemplified the shriveling of natural resources, the suffocation of agricultural livelihoods and rural communities, the overextension of demands and the breaking point of supply. But this summer, as a historic snowpack melted across the West and water roared 6,000 feet down from Lone Cone into the Dolores River Canyon and flooded forgotten banks, it became an emblem of deliverance from drought; of a season that could save.

“Parts of the San Juan Mountains in southwestern Colorado saw record snowpack — most notably the Dolores River Basin. The San Juan Mountains in the Four Corners region has been the epicenter of the megadrought since 2000, and the Dolores River Basin is one of the rivers that’s seen the most significant impacts from drought over the last 23 years,” says Seth Arens, research scientist at Western Water Assessment, the University of Colorado-CIRES and the University of Utah-GCSC. “We had this really impressive line of atmospheric rivers coming onto the coast of California, and they were strong enough that they pushed inland and dumped tremendous amounts of snow.”

Those storms delivered relief nearly everywhere in the West. The Wasatch range in Utah received over 900 inches this winter, and the state reached a snowpack

that clocked in at 201 percent of normal, according to the Department of Natural Resources. The Sierras welcomed back long-lost lakes, and California’s statewide snowpack peaked close to 300 percent of the average level. Pockets of Nevada’s Basin and Range region also saw record levels. Idaho, Wyoming and even areas of Arizona reached above-average snowpack for the year. For the first time in decades, snow piled up to six feet and above at lower elevations around 6,000 feet, allowing the ground to be adequately quenched by the time spring runoff began flowing toward the valleys.

The snow kept falling, and hopes for drought relief rose with the stacking snow. In the spring, the National Integrated Drought Information System’s Special Edition Drought Status Update for the Western United States declared a 50 percent

reduction in drought coverage since the start of the water year.

“This wasn’t the kind of year that was anticipated,” says Arens.

LOOKING AT THE West’s most recent annual water reports is like looking at a rap sheet. The redundant bad years string together — 2018, 2020, 2021, 2022. The summer of 2020 was especially bad. “We had near average snowpack but it ended up getting a 35 percent average runoff” that translated to streamflow, Arens says. Watersheds and reservoirs were depleted, wildfires raged, and the West’s lack was on full display as the “foreseeable future.”

This season’s precipitation snuck in under many scientists’ radars. At the end of 2022, the Western Hemisphere was still considered to be in a moderate La Niña climate pattern, which typically

brings drier and warmer conditions to the Southwest and wetter and cooler conditions to the Northwest in the U.S. But that’s not what played out over the course of the winter. Instead, there was widespread above-average precipitation from southern Oregon and Idaho, all the way to the Mexican border. The season stayed cold, so there was little water lost to midseason melts, and the precipitation piled up. A spring monsoon season brought cooler temperatures and enough moisture to rehydrate soils and accommodate more efficient runoff. Water, for the first time in a long time, became abundant. “The thing that makes this year truly remarkable for me is that it’s so widespread in terms of how much water came in throughout the western U.S.,” says Arens.

When the reservoirs filled and allocations were guaranteed, the memory that just one

year ago, Utah — one of the states with the largest snowpacks in recorded American history — was 80 percent covered in extreme or significant drought, faded. At the time of publishing, just 6.9 percent of the state is considered to be in a condition of drought. “It is undeniably a good thing that we had such a big winter,” he adds. “These are some of the lowest levels of drought we’ve seen in quite a few years.”

California has been engulfed in the intense repercussions of severe drought for years — towns like Mendocino Village running out of water, historic deadly wildfires like the Camp Fire in 2018, and bodies of water like Tulare Lake and the Salton Sea drying up into toxic dust beds and taking local economies with them. But this year, the state experienced a turnaround, most notably for the southern area of the state, which, in the spring, actually had to release freshwater into the ocean because there was simply too much. “When we peaked with our snowpack, it was close to 300 percent of average, which is absolutely insane. And a lot of that came from southern parts of the state where we’ve been really needing that water,” says Andrew Schwartz, the lead scientist and manager of the University of California, Berkeley, Central Sierra Snow Lab. “For the first time since 2006, California has met 100 percent of its water allocations. That’s how big this year is.”

This year was even bigger than other big years, like 1983. That year, the snow water equivalent from the snowpack was recorded around 26 inches in Utah. This year was an extraordinary 29 inches. But somehow, this season didn’t bring widely destructive flooding in states like Utah, as was anticipated. “This year was the perfect scenario for not causing damage,” says Arens. “We didn’t flood because it would warm up and then it would storm or cool down. That cycle of warming up and cooling down makes for a less efficient runoff but in the case of having so much snow it makes it safer from a hazard viewpoint.” Melt cycles, temperature variability, water loss to ground absorption and evaporation, dust on snow events,

and snow sublimation (the vaporization of snow) all contribute to how one historic year can look wildly different from the next when you start crunching numbers. As conditions and climate qualities change, so will our water cycle and weather patterns. And so will our averages.

A common misunderstanding about what “100 percent snowpack” means is that it translates to 100 percent of that area’s historic average. But, it doesn’t. In fact, “100 percent snowpack” is a measurement that changes every few decades, adjusting to the average of the most recent 30-year period. According to the Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, April snowpack declined at 93 percent of the snow telemetry network sites

AS THE RESERVOIRS FILLED AND ALLOCATIONS WERE GUARANTEED, THE MEMORY THAT JUST ONE YEAR AGO, MOST OF THE WEST WAS COVERED IN EXTREME OR SIGNIFICANT DROUGHT, FADED.

that were measured, with the average decline across all sites amounting to nearly 23 percent between 1955 and 2022. Although we are meeting “100 percent snowpack” measurements and beyond some winters, what actually measures as 100 percent is declining. As our target numbers for averages shrink and our water demands and populations grow, operating at an annual deficit becomes the norm. “We use so much water every year that an above-average snowpack is really just like the amount of water that we need to actually fulfill the allocations that we’ve made within the basin,” says Lehto. “Because that’s how big of a deficit we’re running on.”

When you set that stage, it becomes more sobering to understand how California and

other states met their water allocations this year. Meeting 100 percent of a state’s annual water allocations now requires Biblical winters that settle in with a historic 200-300 percent of a region’s annual snowpack.

“If we had ‘average’ years before this, we might’ve gotten away with 100 percent or 150 or 200 percent — it just depends,” says Schwartz. “But because our reservoirs were so low, 300 percent of average snowpack means that we’re fulfilling 100 percent of our allocations for water statewide for the first time since 2006. So it’s taken us (nearly) two decades. But this doesn’t put us ahead for the future. … And probably because of the big winter we had people have lessened their conservation efforts.”

These “new normals” not feeling abnormal is a matter of shifting baselines — defined in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment as “a gradual change in the accepted norms for the condition of the natural environment” due to lack of information or lack of experience. As our seasons change, it can be difficult to discern what is “average” and what is ideal for our needs. “This summer it felt cooler, but if you actually look at the numbers, it’s still running a couple of degrees above the 30-year average,” says Arens. “By looking at historical numbers, it’s still been a hot summer. But because of our recollection as humans, we’re thinking more of the last couple, five, maybe 10 years … our perspective is skewed.” Even record-breaking snowpacks can’t stop our winter average snow from declining and our summer heat from rising.

ONE OF THE lessons of old cowboy wisdom is that you can’t find the holes unless you check the fence line. A water year like this makes the gaps obvious — if we have any after record-breaking abundance, it’s up to us to fix them, not Mother Nature.

We’ve been here before. Both 2017 and 2019 were above-average for snowpack and snow water equivalent content, and yet we still wound up in the deepest drought on human record; with the Great Salt Lake at risk of drying up, Glen Canyon Dam

A COMMON MISUNDERSTANDING ABOUT WHAT “100 PERCENT SNOWPACK” MEANS IS THAT IT TRANSLATES TO 100 PERCENT OF THAT AREA’S HISTORIC AVERAGE. BUT, IT DOESN’T.

nearly falling below power pool levels, and entire communities — namely on Native American reservations — without water. Any lack of action on developing further water solutions serves as two steps back instead of three steps forward when we do have above-average water years. “When we have many dry years, like will eventually happen, we’re gonna go back to that same deficit,” says Schwartz. “We still need to really focus on solutions to our water crisis because, though we’ve had one good year, it’s just delaying the further troubles that we’re going to have when we don’t have that precipitation.”

Experts are skeptical of solutions that haven’t proven to be environmentally or economically beneficial in the past, like building more dams and reservoirs across the West, which aren’t necessarily feasible. Even with additional storage, spreading out the water that you’re getting between more dams means less water in each, causing issues similar to what’s playing out on a large scale in Glen Canyon/Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

As of August, total storage for both Lake Powell and Lake Mead was under 35 percent. If you were to combine both reservoirs’ storage into Lake Mead, that reservoir wouldn’t have reached 70 percent. “Even I was surprised that it wasn’t more,” says Eric Balken, executive director of the Glen Canyon Institute. “Clearly, even after decade-high runoff, if we can’t get close to half-full, that should be an eye-opener for everybody in the basin.”

Water retention is one challenge, but allocation is another. In many Western states, the idea of watersheds and ecosystems themselves having a right to water is a relatively new political idea. In Utah, a water banking statute — 73-31-101 — was adopted during the 2020 general session to help protect the Great Salt Lake’s elevation and HB130 was passed, allowing appropriated water returned to its watershed to finally be considered a “beneficial use” of that water. Since, private water donations have been made to set an example for legislation to make significant impacts for watersheds.

Earlier this year, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints donated over 5,700 water shares in the North Point Consolidated Irrigation Company to the state of Utah for the Great Salt Lake. Following that, Salt Lake City Mayor Erin Mendenhall also formally submitted a request to the City Council to authorize the Public Utilities Department to file the necessary water right documentation amounting to an annual contribution of nearly 13 billion gallons.

Nevada, a notoriously progressive state when it comes to legislation around water conservation, is able to pass water conservation measures with relative ease because of the lack of a large and powerful agricultural lobbying group. Earlier this summer, the state passed a $63 billion initiative to fund 13 water conservation projects and became the first state in the country to give a local water agency the power to limit individual home water use and protect Lake Mead.

“In Colorado, we really don’t prioritize ecosystem needs at all,” says Lehto. “We didn’t legislate the ability to assign water rights to ecosystem needs until the 1970s. Considering water rights have a chronological priority dating, a lot of those rights really don’t materialize when the ecosystem needs them most. … The legal infrastructure that (reservoir managers are) operating under requires them to prioritize the senior water rights holders that they provide water to.”

The politics of senior water rights have gotten thornier in recent years, but they reached a new level this summer. Even when there’s enough water to go around, many communities are still coming up empty-handed. Additional roadblocks for tribes trying to settle their water rights have reared up, such as the 1908 Winters Doctrine. The Supreme Court ruling requires that the United States provide enough water on every treaty for the entire population of a reservation to survive, but these particular rights were not considered during the creation of the Colorado River Compact in 1922. Now, many tribal communities of the Colorado River Basin have to settle for water from the allocation that’s already been

given to that state through the compact, without any access to their own independent rights.

AROUND 100 MILES from the Disappointment Valley, Lake Nighthorse sits full to the brim, its glassy surface reflecting the broad ridgelines of nearby Basin Mountain. Built by the Bureau of Reclamation in 2003 as part of the Animas-La Plata Project, the reservoir is filled by pumps carrying water two miles uphill from the shallow Animas River. Built to the tune of $500 million, Lake Nighthorse’s water is allocated to members of the Southern Ute tribe, the Ute Mountain Ute tribe and the Navajo Nation. However, it’s currently jointly managed by the Bureau of Reclamation and the City of Durango, and none of the tribes have accessed the water. During planning and upon completion, the federal government didn’t provide infrastructure for the delivery of the water. Because of that lack of framework, as soon as any tribe accesses the Nighthorse water they have to start paying back the federal government for the maintenance and operation costs of building the reservoir. So the reservoir sits, mostly untapped, right outside the city of Durango, using nearly as much power as the city itself uses just to pump the water. “I think it’s a good example of the boondoggle of complicated water rights we’ve created for Native Americans in this area,” says Lehto. “How many of them have water rights on paper that they are not actually able to access? Tribes legally could be entitled to (nearly) a third of the water in the Colorado River Basin. In my opinion, any plan going forward needs to acknowledge the very real possibility of the tribes actually using all of their water rights.”

Instead, stand-up paddleboarders float across the surface of Nighthorse, and an inflatable water park bobbles near the shoreline. The reservoir remains full, while the last drops of this season’s version of the Dolores River trickle westward toward Utah, determined to make it to the confluence of the Colorado River.

This year, for the first time in many, this

beneficiary of Disappointment Creek had 55 days of boatable flows. Normally, the Dolores runs between 100-500 cubic feet per second (cfs) when reservoir managers release annual flows. But this year, it roared at 5,000 cfs. The waters flooded beaches and washed away invasive plants. It watered thousands of acres, offering full allotments for farmers. People from the nooks and crannies of the West came to witness the Dolores in this kind of glory. And to enjoy it. Rowing on through this rarely-seen canyon on waters that no one’s ran in over a decade, spirits were high. But for Lehto, being on her boat was bittersweet. “One year of solid snowpack does not negate the consistent deficit we have and how we allocate water in this area,” she says. “I am really happy that this winter provided some relief and some leeway for negotiations, but I’m also a little wary that it gives a false sense of security.”

This season was one of deliverance, even if that simply means having a chance to save ourselves by leveraging this leeway to look ahead and create a better future. “We as humans have short-term memory — especially with things that are a little bit positive,” says Schwartz. “We’ve got some time, but we need to focus on long-term solutions. You can’t just hope water into existence.”

ARTIST BILLY FEFER PAINTED A MURAL ON THE SIDE OF A ROADSIDE STAND WHERE LOCALS SELL ITEMS ON THE NAVAJO RESERVATION NEAR CAMERON, ARIZONA. IN THE MURAL, A YOUNG CHILD REACHES OUT TO TOUCH A FALLING RAIN DROP. MOST OF NAVAJO NATION HAS LIVED WITH DROUGHT FOR THE PAST FEW DECADES.

AS MUCH AS ANY POLITICAL FIGURE IN RECENT MEMORY, MITT ROMNEY ’S FAITH HAS DEFINED HIM IN AN EXCLUSIVE EXCERPT FROM A NEW BIOGRAPHY, Mc KAY COPPINS REVEALS HOW ROMNEY ’S ADHERENCE TO HIS FAITH DEFINED HIS POLITICAL CAREER — AND MAY HAVE BROUGHT IT TO AN END

BY McK AY COPPINS

AS A KID, MITT ROMNEY GLIDED THROUGH GRADE SCHOOL WITH AN IMPISH SENSE OF HUMOR THAT BOTH CHARMED AND EXASPERATED HIS TEACHERS.

There was George, who delivered a belligerent speech at the 1964 Republican convention opposing his party’s nomination of Barry Goldwater. There was Gaskell, who sued the Mexican government — and won — after losing his home during the revolution, and Rey, who flouted laws against foreign proselytizing and turned up in Chihuahua passing out Spanish copies of the Book of Mormon.

the Atlantic and walked across the American Plains to join his fellow Saints in building their desert Zion.

EDITOR’S NOTE: THE HOUSE STYLE OF DESERET MAGAZINE IS TO REFER TO MEMBERS OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS BY THE NAME OF THE CHURCH. THE BOOK, AS EXCERPTED HERE, REFERS TO MEMBERS OF THE CHURCH AS MORMONS.

This story began with Miles Romney, a 19th-century British carpenter who, upon hearing Mormon missionaries preach in a town square, renounced the Church of England, converted to Mormonism, crossed

Charged with designing a tabernacle in the southern Utah settlement of St. George, Miles became fixated on erecting a grand spiral staircase that would lead up to the second-story dais. When the Mormon prophet, Brigham Young, saw the plans, he concluded that the podium would be too high and instructed Miles to cut down the staircase. Miles balked. The prophet insisted. A standoff ensued, and nearly 200 years later the St. George Tabernacle — with its grand spiral staircase that

rises majestically to the building’s second story before awkwardly descending 10 feet to the dais — stands as a testament to the lengths a Romney man will go when he believes he is right about something.

Romneys were not descended like other humans, the family saying goes. We descended from the mule

and Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King.” But the calls to greatness fell flat. Mitt loved his parents, but he felt little drive to rise to their expectations.

When he was 12, he entered Cranbrook, the private boarding school to which Michigan’s ruling class sent its children, and quickly learned that he wouldn’t make it as a jock. The football team cut him at tryouts, and he spent his brief wrestling career getting his limbs bent in ways they were not meant to bend by boys much stronger than he was. Even track, that last refuge of the unathletic teenager, was ruled out after he discovered by way of the presidential fitness exam that he ran the slowest 50-yard dash in his class. He spent time in the yearbook office and the glee club, and one year his mother even urged him — as a kind of Mormon rumspringa — to join the “smoking club.”

“If he wants to smoke,” she insisted, “he can smoke.” Mitt did not want to smoke, but he enrolled in the club anyway to appease his mom and never attended a meeting.

followed, as well as regular nightly phone calls between dorms, but as Mitt became more infatuated she remained standoffish.

Shortly after they began dating, Mitt had to spend a few days in the hospital with appendicitis, during which time, he learned, Ann went on a date with another boy. When Mitt confronted her, expecting a sheepish apology, Ann was defiant. “Do you think you own me or something?” she demanded. “I’ve gone out with you a few times, that means I can’t go out with someone else? I’m supposed to clear that with you?” Mitt was in love.

Ann eventually fell in love, too, but she had other things on her mind. One night, after a date, Mitt parked on a quiet hill near his family’s house and leaned in to kiss her. She stopped him with a decidedly unsexy question: “What do Mormons believe?”

This was not a subject he was interested in discussing right at that moment, but he dutifully searched his mind for an answer. He recited the church’s first Article of Faith: “We believe in God, the Eternal Father, and

IT WAS NOT at first clear that Mitt Romney had inherited his forefathers’ stubbornness. As a kid, he didn’t seem to hold many strong convictions at all. Skinny and good-looking, with an impish sense of humor, he glided through grade school charming and exasperating his teachers.

His parents had high hopes for their precocious youngest son. They saw his potential, and in some ways, they saw themselves in him. His father George delighted in arguing with Mitt, their debates often dominating the family dinner table until both were laughing and gasping for breath. On road trips, his mother Lenore read aloud from the poetry of Sam Walter Foss — “Bring me men to match my mountains”

His true extracurricular passion was pranks. At Cranbrook, he was the kid who filled dorm rooms with shaving cream and blared obnoxious ooga horns during slow dances. He liked to dress up as a firefighter and run into stores pulling a hose and shouting, “This place is gonna blow!” After acquiring a siren and some blue lighting gels from the campus auditorium, he drove around town posing as a police officer and “pulling over” his friends. He carried himself with a rich-kid carelessness — the untroubled air of someone who knew he could get away with anything.

Then he met Ann Davies. He saw her for the first time at a party. She was beautiful and wholesome and slightly reserved in a way that intrigued him, not bubbly and loud like other girls. She was also 15, a sophomore at Cranbrook’s sister school, which suggested to Mitt that she’d be easy to impress. For their first date, he took her out to dinner at the Detroit Athletic Club, where his dad was a member, and then to a screening of “The Sound of Music.” More dates

HIS MORMON FAITH NO LONGER FELT TO HIM LIKE JUST A PART OF HIS HERITAGE, AN INTERESTING HEIRLOOM PASSED DOWN BY HIS FATHERS. IT WAS EXPANDING, GAINING TEXTURE, ATTACHING ITSELF TO EVERY PART OF HIM.

in His Son Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Ghost.” To Mitt’s alarm, this led to a theological conversation about the nature of God. The subject had been bothering Ann ever since her Episcopal priest suggested to her that he didn’t believe in a divine being so much as a general presence of good in the world — an abstract notion that had left Ann cold and searching. Now, as she listened to Mitt describe his church’s teaching that God is a person, a literal heavenly father who knows and cares about each of his children, she was overwhelmed with emotion and began to cry. With the prospect of romance now fully evaporated, Mitt spent the rest of the evening reciting other passages of Mormon scripture to his intensely fascinated girlfriend.

Mitt took Ann to prom later that year and told her that he wanted to marry her one day. She said she felt the same way. But when he suggested that he might skip his Mormon mission so that they could start their lives together sooner, she balked. Somehow, she knew better than he did how important his faith would become to him.

“You’ll resent me for the rest of your life,” she told him. “You have to go.”

he stopped at Romney’s name and said, “That’s the wrong mission. He’s supposed to go to France.”

Mitt arrived in the country a few months later, and was assigned to serve in Le Havre, a working-class port city in Normandy that was still recovering from its decimation during the war two decades earlier. The city had a haunted quality to it; according to mission lore, the last missionaries sent to Le Havre were never heard from again.