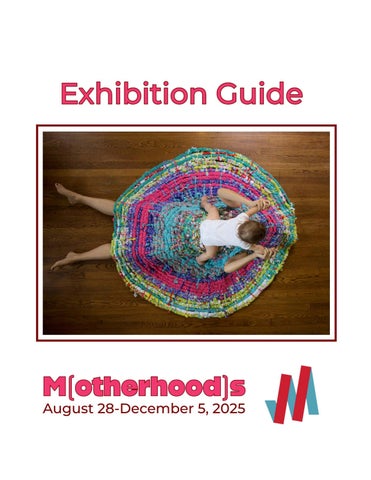

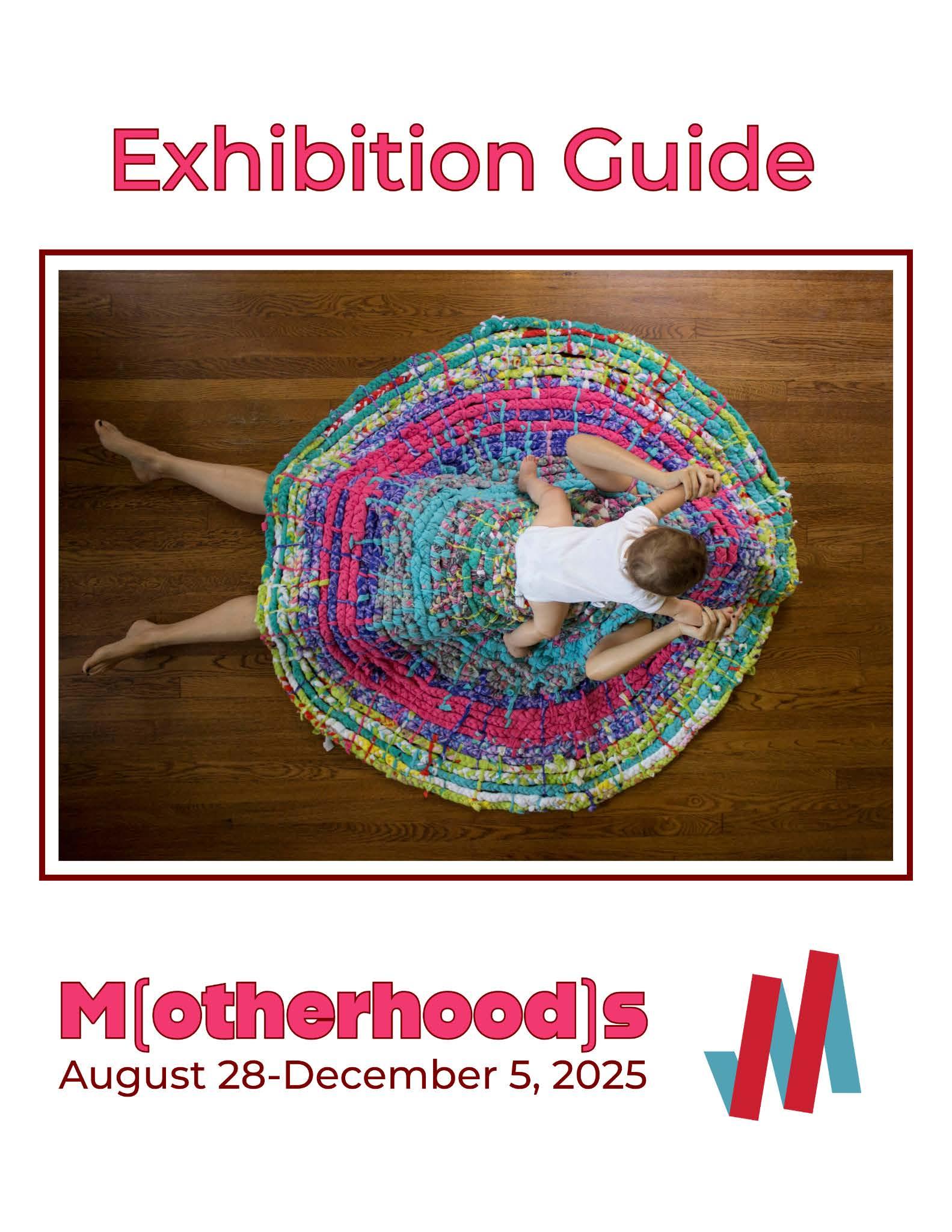

M(otherhood)s

Aug 28-Dec 5, 2025

M(otherhood)s brings together more than a millennia of art, poetry, and film to explore the many ways mothering—by birth, by choice, by circumstance, and by community—takes form across cultures and generations. From the ancient Indian sculpture The Goddess Lajja Gauri and the Renaissance vision of the Holy Family to bold contemporary works by LaToya Ruby Frazier, Judy Chicago, Tracey Emin, and Titus Kaphar, the exhibition invites reflection on care, identity, resilience, and the complicated realities that live alongside love. The works span painting, photography, print, sculpture, video, and the written word, creating a conversation between the intimate and the political, the historical and the now.

Rooted in the museum’s teaching mission, M(otherhood)s is shaped in collaboration with Denison faculty and students across history, literature, psychology, education, gender studies, and the arts. Visitors will encounter an expanded view of motherhood not as a biological role but as a broader experience—one that includes stories of chosen family and caregiving networks, and those who mother in ways often overlooked. The exhibition holds space for joy, struggle, absence, dissent, and deep connection.

Alongside the exhibition, a season of programs—including author talks, poetry readings, film screenings, and community dialogues—offers opportunities to engage these themes with a fresh perspective. Whether you come for the art, the stories, or the conversations, M(otherhood)s invites you to reflect on the timeliness and timelessness of this topic.

Thank you to the many artists and groups that made this exhibition possible.

Ellen Bass

Traci Brimhall

Jessamine Chan

Victoria Chang

Kai Coggin

College of Wooster Art Museum

Ajanae Dawkins

Kendra Decolo

Jess Dugan

Tracey Emin

Stephen Friedman Gallery

Gagosian

Kelly Grace Thomas

The Gund at Kenyon College

Joy Harjo

Hope College, Kruizenga Art Museum

Xavier Hufkens

Titus Kaphar

Kennedy Museum of Art, Ohio University

Julia Kolchinsky

Hyejung Kook

Keetje Kuipers

Danusha Lameris

Laura Larson

Library of Congress

Ada Limon

Erika Meitner

Luisa Muradyan

Kaitlynn Redell

Sheilah and Dani ReStack

Favianna Rodriguez

Miriam Schaer

Therese Shechter

Maggie Smith

Caroline Walker

Annie Wang

Carmen Winant

Special Thanks to the following members of the Denison Community

Beck Series

Amy Butcher

Melissa Huerta

Clare Jen

Min Ji Kang

Julia Kolchinsky

Lisska Center for Intellectual Engagement

Andrea Lourie

Sheilah ReStack

Jack Shuler

Table

Joy Harjo, Remember 6

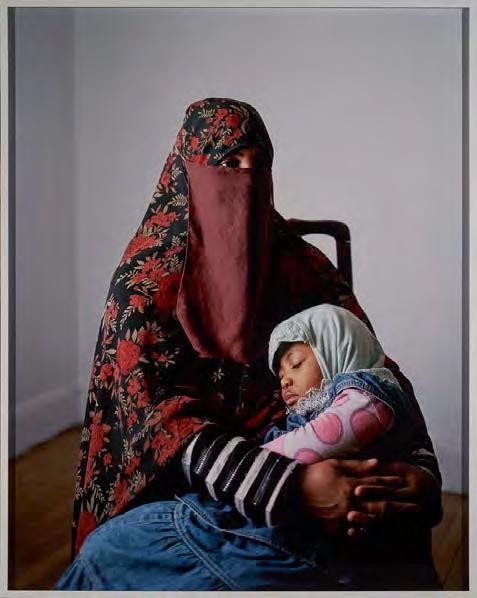

Claire Beckett, April and her daughter Sarah

Domenico Beccafumi, The Holy Family 8

Julia Kolchinsky For War and Water 9

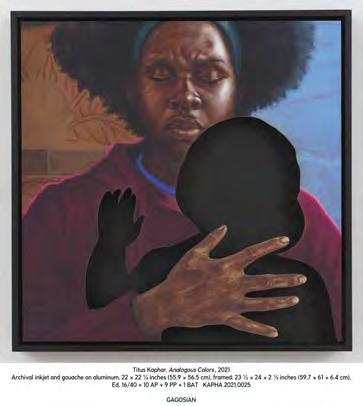

Titus Kaphar, Analogous Colors 10

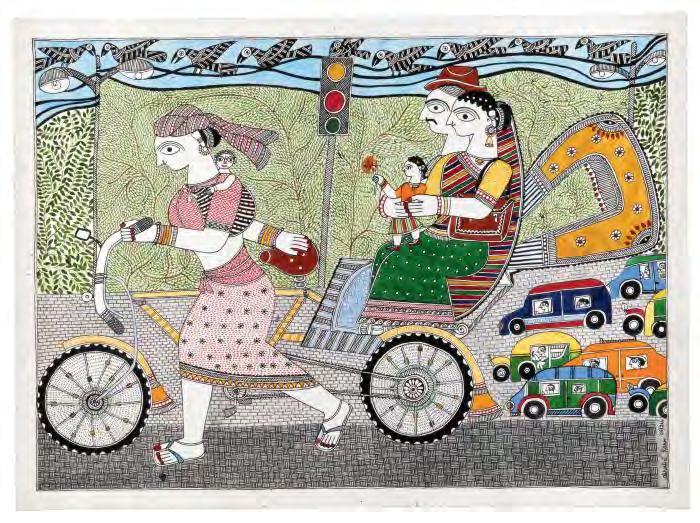

Shalini Karn, Family in a Rickshaw 11

Jessamine Chan, The School for Good Mothers 11

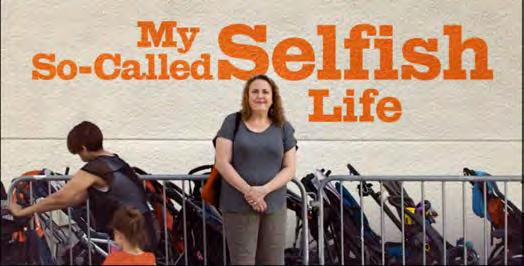

Therese Shechter, My So-Called Selfish Life 12

Annie Wang, Mother as creator 13

Julia Kolchinsky, Tell me it gets easier 14

Caroline Walker, Sensory Play 1 15

Julia Kolchinsky , Other women don’t tell you 16

Kaitlynn Redell, not her(e): (rug), (stuffed animal), (table) 17

Artists Unknown, Collection “hidden mother” photographs, Tintypes 18

Mary Cassatt Quietude 19

Kai Coggin, It’s Not That I Can’t Have Children 20

Miriam Schaer, Babies (Not) on Board: The Last Prejudice? 21

Ada Limón, The Raincoat 23

Dorothea Lange, Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children24 7

Keetje Kuipers, Getting the Baby to Sleep 25

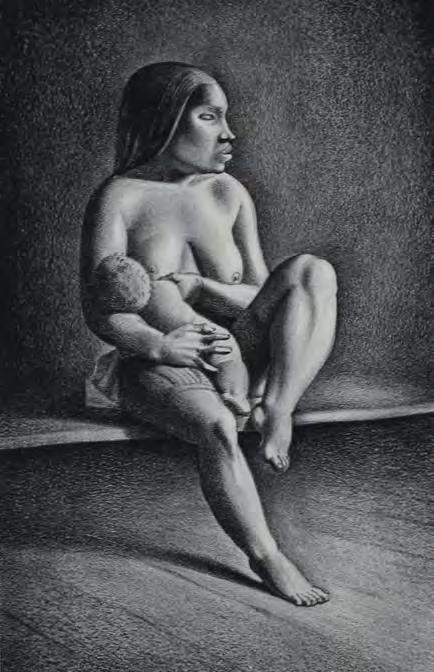

Rockwell Kent, Greenland Mother Nursing Child 26

Donna Ferrato, By leaving her husband, Mary empowered her four daughters… 27

Maggie Smith, The Mother 28

Inuit (Canadian), Woman and Child 29

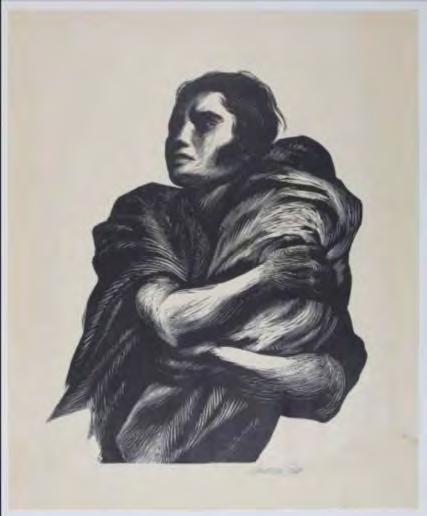

Andrea Gómez y Mendoza, Mother Against War 29

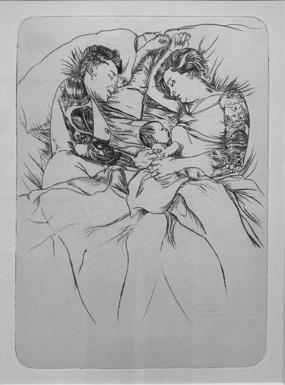

Emily Lombardo, Tests to Stay, 9:54 PM, Send Pics, They can never tear us apart 30

Kendra DeColo, Why in Some Hospitals They Don’t Let You Hold Hands During Labor 31

Jess Dugan, Letter to My Daughter 33

Erika Meitner, My List of True Facts 34

Lamidi Fakeye, Figure of a Kneeling Woman with Child and Covered Bowl (Olumeye) 36

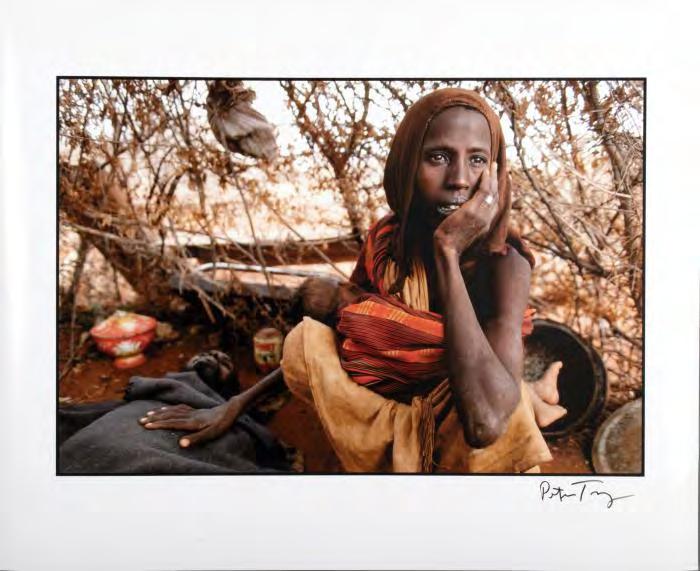

Peter Turnley, Famine crisis, Baidoa, Somalia 37

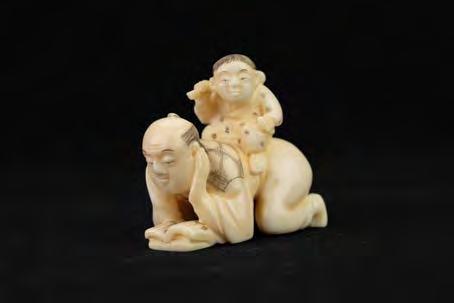

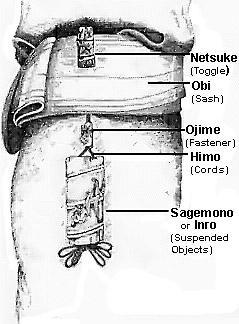

Netsuke 38

Japanese, Mother with Children 39

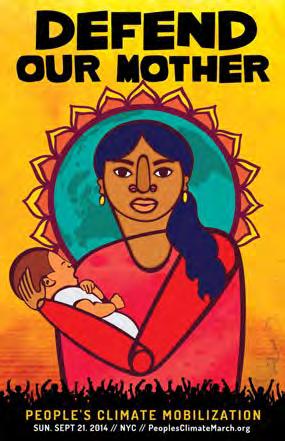

Favianna Rodriquez, People's Climate March 39

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Grandma Ruby Smoking Pall Malls 40

Victoria Chang, How Alone Barbie Chang’s Mother 41

Indian (Indian), The Goddess Lajja Gauri 42

Judy Chicago, The Crowning 43

Ajanaé Dawkins, How to Witness a Miracle Without Converting 44

Lalita Devi, Quickening the Fetus (Pumsavana samskara) 45

Luisa Muradyan, Poem for the Women Who Help You Go to the Bathroom Hours

After You’ve Given Birth 46

Moyra Davey, After Francesca (Mother) 47

Keetje Kuipers, Pregnant Girl Creek 48

Ida Applebroog, So? 50

Julia Kolchinsky, Nature must be a mother 51

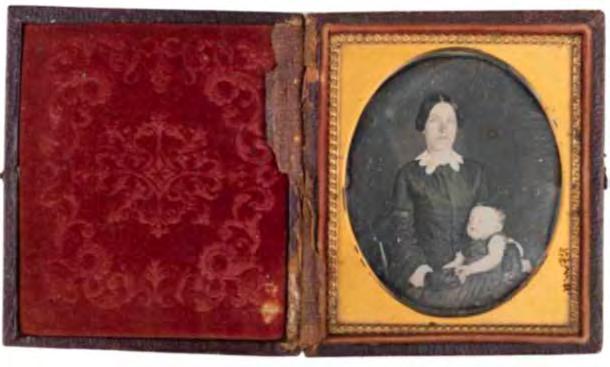

Artist Unknown, Portrait of a Mother Holding Her Deceased Infant 52

Jessamine Chan, The School for Good Mothers 52

Traci Brimhall, Stillborn Elegy 53

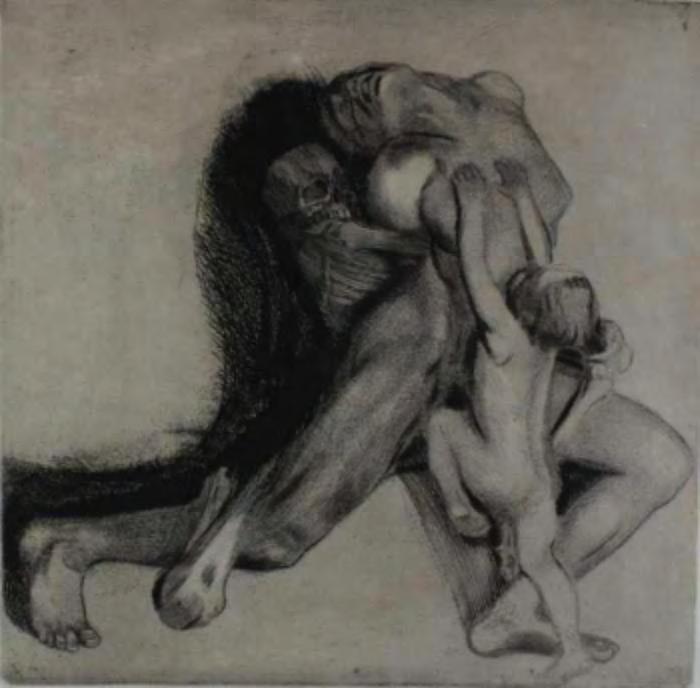

Käthe Kollwitz, Tod und Frau (Death and the Woman) 54

Ellen Bass, Black Coffee 55

Tracey Emin, How it feels 56

Danusha Laméris, DAUGHTER 57

Carmen Winant, My mother and eye 59

Kelly Grace Thomas, What I Know to Be True 60 of recognition (for SER) 61

Sheilah Restack and Dani ReStack, May you choose your own form

Hyejung Kook, The End of October 62

Joy Harjo

Remember the sky that you were born under, know each of the star’s stories. Remember the moon, know who she is. Remember the sun’s birth at dawn, that is the strongest point of time. Remember sundown and the giving away to night. Remember your birth, how your mother struggled to give you form and breath. You are evidence of her life, and her mother’s, and hers.

Remember your father. He is your life, also. Remember the earth whose skin you are: red earth, black earth, yellow earth, white earth brown earth, we are earth. Remember the plants, trees, animal life who all have their tribes, their families, their histories, too. Talk to them, listen to them. They are alive poems. Remember the wind. Remember her voice. She knows the origin of this universe. Remember you are all people and all people are you.

Remember you are this universe and this universe is you. Remember all is in motion, is growing, is you. Remember language comes from this. Remember the dance language is, that life is. Remember.

“Remember.” Copyright © 1983 by Joy Harjo from She Had Some Horses by Joy Harjo.

Claire Beckett (American, 1978 - )

April and her daughter, Sarah, 2013 archival pigment print, 40 x 32 in. (101.6 x 81.3 cm),

Courtesy of The Gund at Kenyon College; Purchased with funds provided by Mr. and Mrs. Graham Gund '63. 2017.1.1

In her series Converts, Claire Beckett takes documentary-style portraits of Americans who have or are in the process of converting to Islam. April gently cradles Sarah on her lap, mimicking the depiction of the Madonna and Child in Italian Renaissance paintings. In Christianity, the Virgin Mary is the pinnacle of white womanhood, the ideal mother. Beckett’s representation of a black Muslim woman in this pose complicates the concept of the Madonna. Beckett’s new envisioning of the Madonna calls attention to the double standard of the veil, in which the niqab worn by April and other Muslim women is viewed from a Western perspective as oppressive, whereas the Virgin Mary’s blue veil is celebrated by Christians as a sign of modesty and purity. The opposition between Christianity and Islam is a current that runs deeply throughout history, most infamously with violent confrontation in the medieval Crusades and more contemporarily in the prevalent stereotyping of Muslims as terrorists based on a few extremist sects. Beckett’s intimate portrait quietly and sweetly bridges this longstanding divide.

Erica Littlejohn ‘19 and Harlee Mollenkopf ‘17 Gund Gallery

Beccafumi, Domenico (Italian, 1486 -1551)

The Holy Family, 1545 Oil on panel, 49 7/16 x 40 3/16 x 2 ¾ in.

Gift of Edmund G. Burke, DU1949.1

Domenico di Pace Becccafumi (1486-1551) was an Italian Renaissance-Mannerist painter of the early 16th Century, best known for large-scale panels. As a Mannerist, he went beyond the classical tradition observed by Michelangelo and Raphael to produce works that explode from the surface. In spite of his explorations, he still respects and relies on the work of his two better-known contemporaries, as this work shows. Beccafumi is the last Sienese painter of importance. He was influenced by the works of Michaelangelo and Raphael, but the emotional content of his paintings mark his very personal style. He worked principally in Siena and the surrounding regions. The work of Beccafumi is related to the mannerist painters of the early sixteenth century.

Description from The Inaugural Exhibition catalogue (1973).

Julia Kolchinsky

Everyone is having boys, my mother says. That means war is coming. The way it came in the old country—boys rising out of the ice and cold potato fields, boys laying bricks and digging, wells and trenches and bodies—boys out of other boys like my boy, born the year before cops killed even more black boys and more boys killed other boys for loving boys and more swastikas showed up on walls and more walls went up, invisible, where once ran rivers. But a river is not a boy. A river can either run dry or bleed and everyone will blame someone darker or an animal, that gorilla who dragged away the little boy or the gator who stole another. But in the water, they seem so strong, resilient even, these boys born months apart, these boys who suck the water down, who beat it with their tiny fists and kick as though they’re running, these boys who grow not knowing they were born for war and that it’s everywhere and there is no outrunning water.

Titus Kaphar (American, 1976-)

Analogous Colors, 2021

Archival inkjet and gouache on aluminum, 22 x 22 1/4 inches 55.9 x 56.5 cm, Ed. 16/40 + 10 AP + 9 PP + 1 BAT, KAPHA 2021.0025 Courtesy the Artist and Gagosian

Analogous Colors (2020), which was first shown in the exhibition From a Tropical Space at Gagosian, New York, in 2020. In the painting, the profile of a child is excised from the image, missing from the mother’s grasp. The painting was featured on the cover of the June 15, 2020, issue of Time magazine, which included a report on the protests sparked by George Floyd’s killing at the hands of Minneapolis police. “In her expression, I see the Black mothers who are unseen, and rendered helpless in this fury against their babies,” wrote Kaphar. “As I listlessly wade through another cycle of violence against black people, I paint a black mother. . . . eyes closed, furrowed brow, holding the contour of her loss.” Gagosian

About Titus Kaphar

Titus Kaphar was born in 1976 in Kalamazoo, Michigan. He currently lives and works between New York and Connecticut, USA. His artworks interact with the history of art by appropriating its styles and mediums. Kaphar cuts, bends, sculpts and mixes the work of Classic and Renaissance painters, creating formal games and new tales between fiction and quotation.

https://omart.org/artwork/analogous-colors/

Shalini Karn (Indian, 1990 -)

Family in a Rickshaw, 2019 ink and pigments on paper, 19 ⅞ x 27 ⅞ in,

Courtesy of Hope College, Kruizenga Art Museum, purchased with funds bequeathed by Roberta VanGilder 2024.7.2

This painting of a young mother operating her own pedal rickshaw business celebrates the increasing independence of many Indian women and the important economic contributions they make to their families. As is typical of Mithila paintings, the image features a densely patterned design created using colored pens and pigments. The materials of Mithila painting make it very difficult to correct mistakes, so the images must be carefully planned in advance and executed with meticulous care.

Kruizenga Art Museum website

“What she can’t explain, what she doesn’t want to admit, what she’s not sure she remembers correctly: how she felt a sudden pleasure when she shut the door and got in the car that took her away from her mind and body and house and child.”

Jessamine Chan, The School for Good Mothers

Therese Shechter (Canadian 1962 - )

My So-Called Selfish Life, 2022 Documentary trailer 2 minutes and 16 seconds. Courtesy of the filmmaker

A revolutionary documentary about reproductive freedom and one of our greatest social taboos: choosing not to become a mother. My So-Called Selfish Life has become a powerful tool for fostering conversations about reproductive autonomy in this post-Roe v Wade era. This entertaining and sharp film delves into the societal pressures women face around motherhood, the oddly intense judgment they often endure, and how the growing childfree community is reshaping what it means to live a fulfilling life.

Titled after one of the myths it gleefully dismantles, the film draws on pop culture, science, and history to amplify the voices of those saying "no thanks" to parenthood—and the determined forces that work to marginalize them in society.

This film arrives precisely when women are questioning long-held beliefs about womanhood, family, and identity. With refreshing irreverence, it exposes how pronatalism doesn't just meddle in politics—it's been rifling through our personal lives uninvited, whether we have children or not.

Trixie Films website

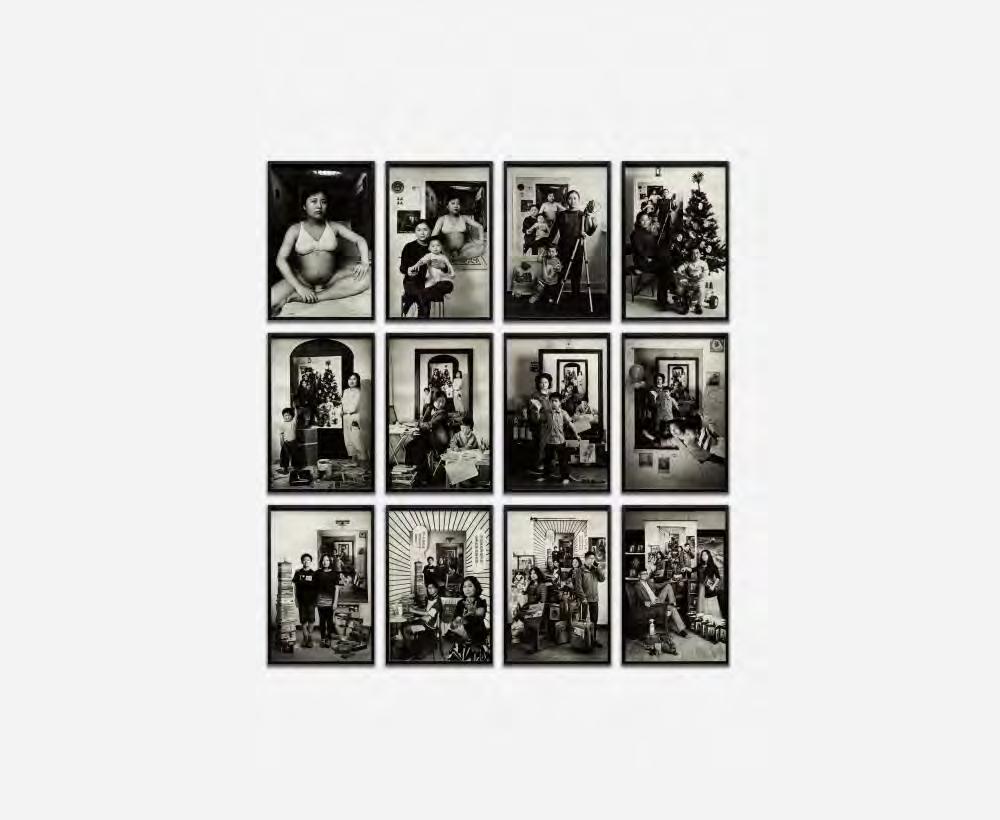

Annie Wang (Taiwanese 1972-)

Mother as creator, Photograph,No 1-12, inkjet print, Courtesy of the artist.

The Mother as creator is the personal project of Taiwanese artist Annie Wang who talks about motherhood and fights stereotypes.

The woman is identified and classified as a mother, condemned inside the limits and identity imposed by society: every year Annie takes pictures of herself and her son, demonstrating how all the elements of her life are important to create always new points of view from which to observe the experience of motherhood. The entire work documents the change and various stages of growth, creating a “layered mother-child dialogue” for seventeen years.

Artist's website

::Tell me it gets easier::

Julia Kolchinsky

every new parent asks, It doesn’t, I say bluntly & something inside us shatters a little, not hope, too large, uncontainable in the body, like sky or the layers of ocean my son knows are named sunlight, twilight, midnight, abyss, & trenches, the further down the closer to war. Tell me it gets easier , they ask to hear difficulty or darkness are temporary, but the depths are endless not because they do not end but because we’ve never reached the bottom.

In water, the difference between float / sink / swim / drown are matters of breath & motion, little to do with light & everything with ease.

Endurance a resistance all its own.

It doesn’t , I say again, my face reflected in the shallow sink that just won’t drain. It never gets easier, I exhale. We just grow used to bearing difficulty. We hold our breaths long enough to reach the surface.

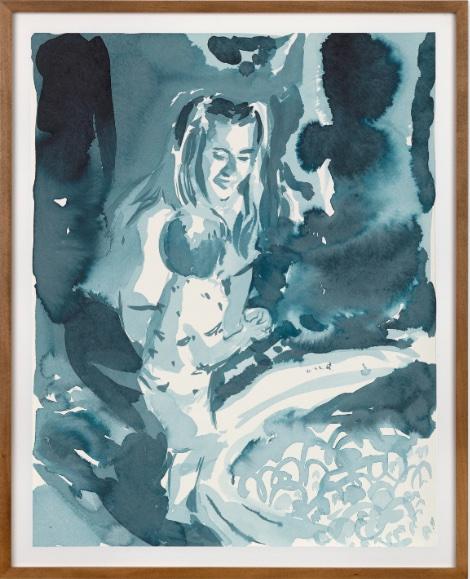

Caroline Walker (Scottish 1982-)

Sensory Play 1, 2024 Ink on Paper, 47.5 x 37 cm (18 ¾ x 14 ⅝ in),

Framed : 53.3 x 39.4 cm (21 x 15 ½ in), (WALKER 94)

Copyright Caroline Walker. Courtesy the artist; Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York; GRIMM, Amsterdam / New York / London; and Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh. Photo by Peter Mallet.

“Walker's ink drawing Sensory Play I, an expressive piece that shows an early-years teacher encouraging a child to interact with a ball pit. Both subjects appear seemingly unaware of the viewer’s presence; the adult is engaged, while the child engages in jubilant play.”

Stephen Friedman Gallery website

Other women don’t tell you

Julia Kolchinsky

it’s a battle for the body, for every part of it, he’s all you, some say, he has your eyes, and others, he has your hair, look at those curls, and you let them twist around your finger, vine tendrils more plant than boy, more wild than will, more him than you, but it’s a battle for ownership, for claiming the body you left him with as yours, and when you tell your mom he rode the escalator up and down, repeating “Whoaaaaa” in fascination at each descent away from the flourescence until the lights of Gucci and Versace drew him towards their dazzle, He has good taste, your mother says, then adds, You used to have taste too So now you lack the parts of you you’ve given him, your eyes are likely gone as well. You’re chasing a toddler, blind through the shopping mall, you’re Tiresias, prophet, between earth and myth, god and manlike thing, you’ve given everything away to own these parts of him, his eyes and hair, the certainty that they are yours, or so they tell you. So you are blind and bald and he is full of sight and mane and beautiful, and soon, your mother tells you, she won’t know how to talk to you, but also that he doesn’t have your mouth, his nose, she’s said, is undecided still, unclear if he will wear your history of bones, dead noses piling up, all yours yours yours, but maybe, not his, maybe, other women tell you he looks just like his dad, and you see it in his cheeks and jaw line, in the flatness of his feet, the ankles caving in, and in the dips from waist to hind, as though some god or ghost has left their thumbprints to remind you how his body isn’t yours at all.

Kaitlynn Redell (American 1985- )

Upper Left - not her(e) (rug)

Center- (stuffed animal)

Upper Right- (table)

Digital c-print, 2016, 24x36

Courtesy of the artist.

“not her(e) explores how life as a caregiver is about being used as well as being invisible. Throughout this series, Redell becomes camouflaged and a part of the furniture while performing everyday acts of care for her daughter. She is interested in how structures of power are set up to produce this particular dynamic of childcare.”

artist’s website

Artists Unknown, Collection of eleven 19th - 20th century “hidden mother” photographs, Tintypes, gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Laura Larson’s private collection.

Because exposure times for early photographs were much longer, sitters often had to remain still for up to a minute. When photographing children, mothers frequently acted as both props and support, helping their children stay steady. Laura Larson, author of the 2016 book Hidden Mothers, has compiled a collection of tintype portraits of young children held by their mothers, whose faces were intentionally obscured through staging or post-production editing. These images invite viewers to consider the visibility and expectations of motherhood within the early language of photography.

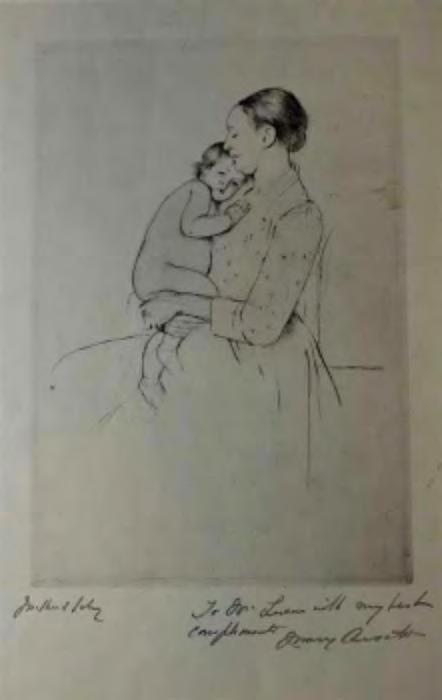

Mary Cassatt (American 1844-1926)

Quietude, 1891 Drypoint, 13 x 16 15/16 in.

Denison Museum, Gift of Frank Flagg Taylor DU1944.33

Mary Cassatt, the only American artist among the French Impressionists—and the only woman in their circle—was renowned for her intimate depictions of women in everyday life, from social gatherings to moments of quiet domesticity. Her frequent portrayals of mothers and children reflect both personal access and social reality: as a woman, her entry into the public and professional spaces her male counterparts painted was limited, while the home was considered the natural domain of women. By focusing on the relationships within these private spaces, Cassatt brought depth and complexity to subjects often dismissed as “feminine,” navigating the double standard of a Parisian art world that both valued and marginalized her perspective.

It’s Not That I Can’t Have Children

Kai Coggin

It’s not that I can’t have children that my body is not a house— it’s just that my life never had the chance to make room, did not open in a way to make itself a womb, the timing of years between my lover and mine, the age of different periods of mothering inclining and declining at the same time,

there just was never the solid enough ground of myself or the chance even, a man was not in the cards and I never even played from that deck, so it never really became a possibility, and I am almost at the apex of this want, this deep yearning to hold a child of my own flesh and bone, to make my body a home—

but perhaps that proverbial ship has sailed, and the life that I have created is the life I have the life I love. Perhaps my womb has turned outwards somehow, and my heart is fertility itself.

Perhaps I have always been a mother without a human child, searching for my children in the trees, in the understory of ancient forests, hidden under smooth stones, in warm fur-covered bodies, in wing tuft and claw, in the exoskeletons of nymphs, phylums that lack a sort of mothering I can give, and so I tend to the wild ones, I mother other kingdoms, rock every other species to sleep— the green and howl and pulse and bloom.

It’s not that I can’t have children, it’s that I already do.

From Mother of Other Kingdoms (Harbor Editions, 2024) by Kai Coggin.

Miriam Schaer (American 1956-)

Babies (Not) on Board: The Last Prejudice? Courtesy of the Artist.

(top row, left)

Babies (Not) On Board 2. Childless women lack an essential humanity. Hand embroidery on Baby Dress.16 x 15, 2010

(top row, center)

Babies (Not) On Board 5. Your decision not to have children is a rebellion against God’s will.

Hand embroidery on Baby Dress 13 x 18, 2011

(top row, right)

Babies (Not) On Board 15. Yes, you’re married, but without kids, you are not a family. So no one really knows what to make of you and your spouse.

Hand embroidery on Baby Romper 14 x 18 2012

(middle row, left)

Babies (Not) On Board 4.

Much as I like to trumpet the importance of a woman’s right to choose all things at all time, there is one choice I simply cannot understand the choice of an otherwise healthy and sane woman not to have children.

Hand embroidery on Baby Dress 18.5 x 22, 2011

(middle row, center)

Babies (Not) On Board 13.

You are not a real parent if you only have one child

Hand embroidery on Baby Romper. 19 x 16 2012

(middle row, right)

Babies (Not) On Board 6. You still have time; maybe you’ll change your mind. You can adopt.

Hand embroidery on Baby Dress. 14 x 20, 2010

(bottom row, left)

Babies (Not) On Board 9. Your child is the best art you have ever made. You don’t need to make any other artwork. Hand embroidery on Baby Romper 19 x 15, 2012

(bottom row, center)

Babies (Not) On Board 1. Your not having children was the biggest disappointment of our life.

Hand embroidery on Baby Dress.15 x 19, 2010

(bottom row, right)

Babies (Not) On Board 3. It is the childless woman who is regarded as cold and odd.

Hand embroidery on Baby Dress 21 x 24, 2010

“Gathered from interviews with childless women, online research, and personal experience, the statements taunt and accuse, and are typical of a relentless flow of critical statements that seem to be growing bolder even as non-traditional families gain greater acceptance.”

Artist’s website

Ada Limón

When the doctor suggested surgery and a brace for all my youngest years, my parents scrambled to take me to massage therapy, deep tissue work, osteopathy, and soon my crooked spine unspooled a bit, I could breathe again, and move more in a body unclouded by pain. My mom would tell me to sing songs to her the whole forty-five minute drive to Middle Two Rock Road and fortyfive minutes back from physical therapy. She’d say, even my voice sounded unfettered by my spine afterward. So I sang and sang, because I thought she liked it. I never asked her what she gave up to drive me, or how her day was before this chore. Today, at her age, I was driving myself home from yet another spine appointment, singing along to some maudlin but solid song on the radio, and I saw a mom take her raincoat off and give it to her young daughter when a storm took over the afternoon. My god, I thought, my whole life I’ve been under her raincoat thinking it was somehow a marvel that I never got wet.

From The Carrying (Milkweed Editions, 2018) by Ada Limón. Copyright © 2018 by Ada Limón.

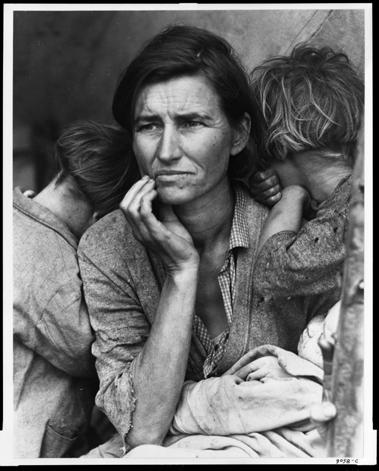

Dorothea Lange (American 1895-1965)

Farm Security Administration: Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children, 1936 (upper right) Photograph, 5 ⅝ x 9 ⅝ inches,

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

This is among the Library of Congress’s most requested images. In Nipomo, California, Dorothea Lange, who worked for the Resettlement Administration (a New Deal program created to assist low-income families), came upon a family whose car had stalled outside of a pea pickers camp. Lange approached the stranded woman in a tent surrounded by some of her seven children and took six exposures. Lange’s later director, Roy Stryker, referred to the Migrant Mother as the “ultimate photo of the Depression Era.” In subsequent decades, artists have copied the mother and children but given them the features of other ethnicities, making the mother’s burdens universal. Florence Owens Thompson, the original Migrant Mother, was Native American.

Library of Congress

The photograph that has become known as "Migrant Mother" is one of a series of photographs that Dorothea Lange made of Florence Owens Thompson and her children in March of 1936 in Nipomo, California. Lange was concluding a month's trip photographing migratory farm labor around the state for what was then the Resettlement Administration. In 1960, Lange gave this account of the experience: I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that leanto tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it. (From: Lange's "The Assignment I'll Never Forget: Migrant Mother," Popular Photography, Feb. 1960).

The images were made using a Graflex camera. The original negatives are 4x5" film. Library of Congress https://guides.loc.gov/migrant-mother

Getting the Baby to Sleep

Keetje Kuipers

Sometimes the baby can’t reconcile the self with the self: too hungry to eat, too tired to sleep. I know the feeling. O, America, on those nights when you are too beautiful for me to continue to forgive you any longer— for allowing us to kill each other with your graceless bullets, or exile our neighbors across your fictitious border, or argue over the ownership of each young girl’s body as if its freedom is a lie she must stop telling herself—

I go out into your radiant embrace. The baby and I drive through your streets, over the bridge and its light-chipped

waters, under a moon so big, so full of itself that though I know it belongs to the world, it can’t be anything but

American. I hang my arm out the window and skim the air like touching skin. I breathe you in, and the baby sleeps.

Rockwell

Kent ( American 1882-1971) Lower Left

Greenland Mother Nursing Child, 20th century Lithograph, 15 ¾ x 11 ¼ in, Denison Museum, Gift of Emma Martin. DU1946.106

Rockwell Kent spent several years in Greenland, photographing and portraying Greenlanders in their daily lives. He documented a wide range of scenes, from community gatherings to moments of quiet domesticity. In his book N by E, Kent reflects on his depiction of a nursing mother with an accompanying poem:

“Little whimpering babe, little suckling babe nestle against mother. How she burns, how she burns, straddling, she makes warm my arm and my hands. Down there is the black-bluish spot which will never come off however much I lick her tender little loins. How she whimpers, how she begs little troublesome girl of mine.”

N by E by Rockwell Kent

Donna Ferrato (American 1949 -)

By leaving her husband, Mary empowered her four daughters to never tolerate abuse. St. Paul, Minnesota, 1985, Gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 in (50.8 x 60.96 cm),

Courtesy of Hope College, Kruizenga Art Museum, gift of Scott Tannen. 2019.91.6

Documentary photographer Donna Ferrato has earned an international reputation for her decades-long effort to highlight the problem of domestic violence. This photograph was taken as part of a project Ferrato began in the 1980s to document the lives of women who survived and escaped abusive relationships. The narrative title identifies the survivor and briefly encapsulates her story. The photograph was published in Ferrato's 1991 book Living with the Enemy

Kruizenga Art Museum website

Maggie Smith

The mother is a weapon you load yourself into, little bullet.

The mother is glass through which you see, in excruciating detail, yourself.

The mother is landscape.

See how she thinks of a tree and fills a forest with the repeated thought.

Before the invention of cursive the mother is manuscript.

The mother is sky.

See how she wears a shawl of starlings, how she pulls the thrumming around her shoulders.

The mother is a prism.

The mother is a gun.

See how light passes through her.

See how she fires.

Inuit (Canadian) Woman and Child

stone,

Courtesy of Hope College, Kruizenga Art Museum, Gift of Roberta V. Kaye. 2016.38.21

The inuit woman depicted here is wearing an Amauti (ah-MAH-tee), a parka with a hood specially designed to carry infants or young children. The name of the hood varies by region as does the style of Amauti but this garment is a mainstay of the northern inuit people. Designed to allow the mother’s hands freedom as she carries her child. This allowed for children to accompany their mother on errands, giving the child an opportunity to watch and learn the daily tasks and allowing the mother to move unencumbered.

Andrea Gómez y Mendoza (Mexican, 1926 – 2012)

Mother Against War, 1965 Linotype, 20 x 16.9 in. (50.8 x 43.02 cm)

Courtesy of Hope College, Kruizenga Art Museum. 2016.48.2

“Trained as a painter and printmaker, Andrea Gomez y Mendoza joined the Mexico City-based People’s Graphic Workshop in the early 1950s. She created this image of a woman striking a defiant yet protective pose with her child in 1956 as a protest against the global threat of nuclear war. The print won international acclaim and earned Gomez invitations to visit Cuba, China, the Soviet Union and multiple countries in Eastern Europe during the late 1950s and 60s.”

Kruizenga Art Museum

Emily Lombardo (American, 1977-)

(upper left)

Tests to Stay, 2022

Drypoint

(upper right)

Send Pics, 2022

Drypoint 9×12 IN. 12 × 9 IN

(lower left)

Drypoint,

(lower right)

They can never tear us 9:54 PM, 2022 apart (on repeat), 2022

Drypoint 12 × 8 IN 6×8IN.

Courtesy of the College of Wooster Art Museum.

“E. Lombardo's new series of works, Soft Butch Blues, explores the artist and her wife's journey to parenthood. The series of fourteen drypoint prints documents the intimate process from trigger shots to birth to acclimating as a family of three. Addressing reproductive rights, body autonomy, fear, anxiety, and more, Soft Butch Blues navigates difficult subjects with joy, warmth, and refreshing frankness.

Lombardo's new prints are an autobiographical resistance against society's tendency towards lesbian erasure. They record both the extraordinary and mundane events associated with birth and parenthood through a lesbian-centric lens, capturing a unique yet familiar perspective on family. Executed in fine intricate colorful lines on varied papers, the prints in Soft Butch Blues display the exuberance, worry, and fragility of the family's experience.

Lombardo and her wife's identities as working-class queer women in New York City are central to how their distinct yet recognizable narrative unfolds. Trigger intimately records an integral part of the IUI process, with a closeup image of Lombardo giving a hormone injection to her wife. Tests to Stay addresses the anxieties of trying to conceive during Covid – an ovulation test is seen amongst rapid tests and various objects symbolizing fertility, courage, and extinction. Later prints document Lombardo's wife's changing body and the physical and mental toll of pregnancy upon her person. 9:54 PM celebrates the much-awaited arrival of their daughter.

The completion of the Soft Butch Blues series and its exhibition at Childs Gallery comes at a tumultuous time within the United States, as the country sees the potential unfolding of a dangerous reversal in equality and human rights. In this environment, the amplification of queer narratives is crucial.”

Childs Gallery

Why in Some Hospitals They Don’t Let You Hold Hands During Labor

Kendra DeColo

Consider the perineum stretched like cheap nylons

each night, two fingers then three dipped in oil

opening the taint’s buttery seam. Consider the bloody asterisk of mucus plug, amniotic sac that refused to break

until I unhooked from the saline drip

and danced until I pissed myself, urine streaming pink

down my legs. Consider the wedding band

my husband removed before I crushed

his hand at ten centimeters, bit his knuckle as if excavating

myself from a wreck; excrement and buckets of ice,

the mirror someone placed between my legs until I understood

I didn’t need it, closed my eyes and orchestrated my own

resurrection, cupping the dark oil of my daughter’s hair

as she emerged. Yes, I would have pulled my husband into the abyss with me,

tearing open in every direction like a star. I would have cracked

his carpals like a piano’s brittle keys like snapping the neck of a dove.

I would have burned the whole place down to get where I needed to go.

I Am Not

From

Trying to Hide My Hungers From the World (BOA Editions, 2021) by Kendra DeColo.

Jess Dugan (American, 1986-)

Letter to My Daughter, 2023 (center) Video, 16 minutes

Courtesy of the artist

“Letter to My Daughter is an autobiographical video directed to my five-year-old daughter, Elinor, that centers around my experience with parenthood throughout the first five years of her life. The audio soundtrack is my voice reading a letter to Elinor, and the images are from my personal archive and include snapshots, ultrasound images, and photographs from Family Pictures. The letter is highly personal and addresses a variety of topics, including my expectations around parenthood, the long and circuitous journey of trying to have a child with both known and anonymous sperm donors, the experiences of miscarriage and loss, and my adjustment to parenthood as a queer and nonbinary person. Perhaps most importantly, it tries to put into words the intensity of love between a parent and child as well as the significant personal growth parenthood both inspires and requires.

Letter to My Daughter is part of my larger exploration of family. It is in dialogue with my 2017 video, Letter to My Father, which explores my estranged relationship with my father, as well as my long-term series of photographs Family Pictures (2012-present), which focuses on the intimacy of familial relationships, aging, and the passage of time through an extended look at three generations of my family.”

Artist’s website

Erika Meitner

I am 43 and I just drove to CVS at 9:30 p.m. on a Sunday to buy a store-brand pregnancy test two sticks in a box rung up by a clerk who looked like the human embodiment of a Ken doll with his coiffed blond hair and red smock even though I wished there was a tired older woman at the register this once even though I am sure I am not pregnant this missing my period is almost definitely another trick of perimenopause along with the inexplicable rage at all humans the insane sex drive and the blood that when it comes overwhelms everything with two sons already what would I do with a baby now even though I spent four long years trying to have another I am done have given away all the small clothes and plastic devices that make noise just looking at toddlers leaves me exhausted this would be a particularly cruel trick of nature the CVS was empty there was no one in cosmetics or any aisle including family planning which is mostly lube and condoms I didn’t know Naturalamb was a thing “real skin-to-skin intimacy” there’s just one small half of one shelf of pregnancy tests and some say no/yes in case you don’t think you can read blue or pink lines appearing in a circle my grandmother was a nurse-midwife during the war in the Sosnowiec ghetto her brother ten years younger a change-of-life child she called him when she told me finally she had a brother when the archivists came around for her testimony years after her brother was gassed alongside her mother in Auschwitz years after my grandmother euthanized her own daughter whom I was named for because the SS were tossing babies from the windows of cattle cars change-of-life child the name for a baby born to an older mother past forty I peed on so many sticks over so many years gave myself scores of injections took pills went under anesthesia and knives since there’s an unspoken mandate to procreate when all your people your family were actually slaughtered I gave one son my grandmother’s brother’s name and the other was called King Myson by his birth mother on the page of notes we got that she filled out before she gave him up it took me an hour of staring at the form

before I realized it was my son she was claiming him before she let him go and I think the morning will bring nothing just one blue line but right now it is still night and I am sitting in my car under the parking lot lights which are bright and static like me and beyond them there’s the clerk in the red smock locking the doors

Lamidi Fakeye (Nigerian, 1925-2009)

Figure of a Kneeling Woman with Child and Covered Bowl (Olumeye), 1990 . iroko wood, 12 ¾ x 2 ¾ x 4 ¾ in (32.38 x 6.99 x 12.07 cm)

Courtesy of Hope College, Kruizenga Art Museum, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Bruce Haight. 2017.60.6

The covered bowl held by this female figure represents a container of kola nuts. Kola nuts come from trees of the Cola genus that is native to West Africa. They contain caffeine and were traditionally enjoyed as a mild stimulant at social gatherings, as an aid to digestion at ceremonial feasts, and as the currency of conversation among hosts and their guests. Kola nuts were also used as offerings to the gods, so this figure of a kneeling woman with child—representing fertility and humility—would have been suitable for use in the houses of affluent families or on shrines dedicated to many different deities.

Kruizenga Art Museum website

Peter Turnley (American 1955-)

Famine crisis, Baidoa, Somalia, 1992

archival pigment print, 13 ½ x 20 in ( 34.29 x 50.8 cm)

Courtesy of Hope College, Kruizenga Art Museum. 2019.93.5

In January 1991, the long-time dictatorial ruler of Somalia, President Mohammed Siad Barre, was overthrown by a coalition of rebel armies that soon began fighting amongst themselves for control of the country. The ensuing civil war destroyed the nation's agricultural and commercial economies and created a severe famine that killed an estimated 300,000 people over the next eighteen months. The fighting and the famine also forced millions of Somalis to leave their homes and seek safety and sustenance in refugee camps run by various international agencies. This image by photojournalist Peter Turnley depicts an exhausted-looking Somali mother and child sitting under a rudimentary shelter at a refugee camp near the city of Baidoa in southwestern Somalia.

Kruizenga Art Museum website

Netsuke

Carved ivory with pigment 1 ¾ x 1 11/16 x 1 in Denison Museum, DU1987.175

Netsuke

Carved ivory with pigment 1 ½ x 1 x 1 in. Denison Museum, DU1987.102

Netsuke first appeared in Japan during the Edo period (1603–1867) as functional accessories for kimonos. Since men’s kimonos lacked pockets, small items like pipes or tobacco pouches were suspended from a silk cord tucked under the sash, with a netsuke acting as a weight to keep the cord in place.

Often carved from ivory—a durable and highly valued material—netsuke featured designs ranging from nature and zodiac animals to humorous or satirical imagery. Because strict social codes limited personal adornment, especially for those below the samurai class, netsuke became a subtle means of self-expression and, for some, a quiet display of wealth.

By the mid-19th century, as Western clothing replaced the kimono in public life, netsuke shifted from everyday accessories to collectible works of art. Today, artists continue to experiment with new materials and designs, blending tradition with contemporary creativity.

In both size and subject, these pieces evoke the small but profound moments of daily life. How does their intimate scale shape your interpretation of these scenes?

Japanese

Mother with Children, 19th century

Bronze, shakudo, gilding

2 ¼ x 1 ½ in. (5.72 x 3.81 cm)

Courtesy of Hope College, Kruizenga Art Museum, gift of David Kamansky and Gerald Wheaton. 20234.13.101

Favianna Rodriquez (American 1978-)

People's Climate March, 2014 offset ,18 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the Artist.

This piece was originally commissioned by the People's Climate March in New York City. It was one of a series of posters commissioned by 350.org and the Climate March to mobilize people across North America for the event. It quickly became the most widely shared image for the historic march and we even developed it into puppets.

I created this piece to represent a woman of color and her child at the frontlines of the fight against the climate crisis. I believe that most visual imagery about climate change does a poor job of speaking to communities of color, communities who are the most affected by environmental destruction and ecological disruption. This piece shows a fierce mama standing up for our mother, Pachamama, and defending her family and her home.

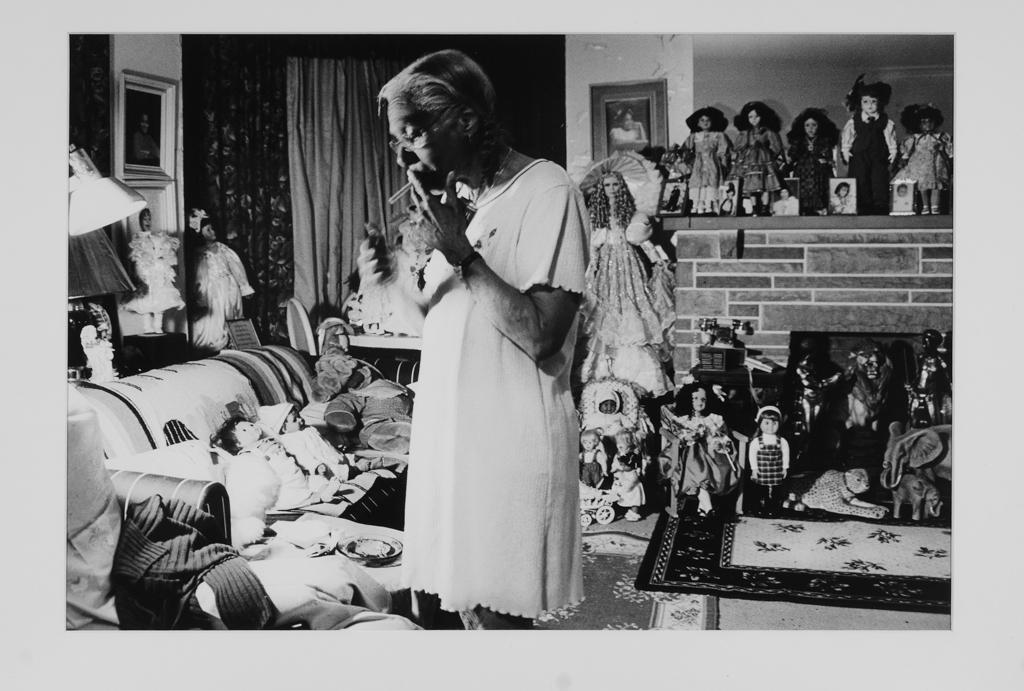

LaToya Ruby Frazier (American 1982 – ) Grandma Ruby Smoking Pall Malls, 2002 gelatin silver print 24 x 28 in. (60.96 x 71.12 cm)

Collection of The Gund at Kenyon College; Gift of David Horvitz '74 and Francie Bishop Good. 2023.2.2

LaToya Ruby Frazier takes a documentary-style approach in revealing the destruction of family life through the detrimental effects of capitalism and environmental injustice. This photo is part of Frazier's "The Notion Of Family" (2001–2014) series, which reveals the socio-economic decline and pollution caused by the closure of the steel mills that originally brought prosperity to her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. This photograph reveals both the love and dysfunction of Frazier’s childhood homelife in this honest portrait of her grandmother, cigarette in mouth, surrounded by a collection of predominantly white, elaborately dressed, vintage dolls. How does Frazier invite outsiders into her home to reflect on intergenerational traumas? Does the portrait of her grandmother still demonstrate the deep love and care that she felt, even with a fractured family? "The Notion of Family" series reflects on familial disruption, exposing the societal damage that structural racial inequity brings, while also portraying the strength and perseverance of families on the margins of society.

The Gund Gallery

How Alone Barbie Chang’s Mother

Victoria Chang

How alone Barbie Chang’s mother must have felt doing

nothing but dying her mother actually stopped dying her hair

in January stopped being an actuary for her money she

must have known her time was limited did the diseased birch

tree know they were going to cut it down how quickly the air

around it filled in the space it does no good to know a mother’s

face who would have known that a mother’s face could

be erased too at some point we are all eliminated from this

earth at some point most of us give birth at some point we lose

a mother at some point we are all disappointments who

can’t possibly care for others when our mothers die we

are all lost and there are no words for it some want to

name us as grieving others wrongly name us heroes

From Barbie Chang (Copper Canyon Press, 2017). Copyright © 2017 by Victoria Chang.

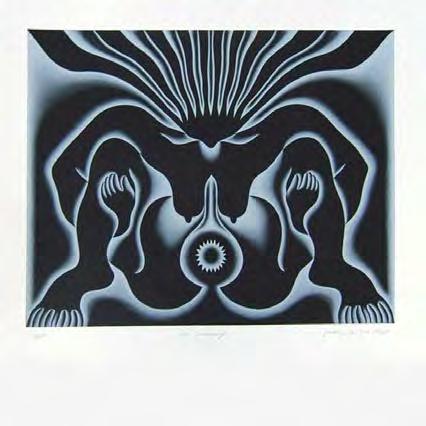

Indian

The Goddess Lajja Gauri, circa 6th-9th century

Stone, 3 ¼ x 5 ¼ in (8.25 x 13.34 cm)

Courtesy of Hope College, Kruizenga

Art Museum, gift of David Kamansky and Gerald Wheaton. 2024.13.185

“Lajja Gauri is shown in a birthing posture but does not display the swollen belly of one about to give birth, which suggests that the image is of sexual fecundity. The lotus flower in place of her head makes this association with fertility explicit. This expression of the concept of the female body as the embodiment of life-affirming forces is perhaps the most extreme in Indian iconography.”

The Met website

Judy Chicago (American, 1939), The Crowning (from A Retrospective in a Box), 2009, Lithograph. 24 × 24 in, Edition: ed. 50, Courtesy of the Kennedy Museum of Art, Ohio University. 2018.03.06

“This image by Judy Chicago is part of her Birth Project, a series of works in which Chicago renders the heroic and underrepresented imagery associated with giving birth.”

Turner Carrol Gallery

How to Witness a Miracle Without Converting

Ajanaé Dawkins

My mother swapped prayer for sharp screams when my sister crowned. The epidural settled on one side until the nerves in her left hip became stars, dying down the dark of her thigh. At 17, I watched a girlchild emerge covered in only-God-canname. Maybe, blood-light. Star-vein. Watersky. A boneless sea creature who knows something about the universe sitting next to ours. I don’t want to go back nor do I want to die this way—making daughters. My body has a tenure of chaos and blood. It’s clotting and ache began at the edge of girlhood. I see no way out.

Lalita Devi (Indian, 1945 - )

Quickening the Fetus (Pumsavana samskara), 1981

pigment on paper, 22 x 30 in (55.88 x 76.2 cm)

Courtesy of the Kruizenga Art Museum, purchased with funds bequeathed by Roberta VanGlider. 2020.14.1

“Ancient Hindu medical texts assumed that the gender of the fetus was not determined until the fourth or fifth month. Therefore, an additional samskara (ceremony) to ensure a male fetus was prescribed for the third or fourth month of pregnancy before the quickening of the fetus. Performed when the moon is in a male constellation, this ritual, known as pumsavana, is meant to stimulate, consecrate, and influence the fetus bringing about a male child.”

The Hindu World, Ch 15, pg 430

Poem for the Women Who Help You Go to the Bathroom Hours After You’ve Given Birth

Luisa Muradyan

Everyone thought that the bird who fell out of the sky was dead from exhaustion. She could no longer do the thing that she was born to do. It’s like that, except minutes before the fall when the wind made her empty body weightless.

Moyra Davey (Canadian 1958-)

After Francesca (Mother), 2023 Photograph Courtesy of Sheliah ReStack.

Inspired by the work of photographer Francesca Woodman, the site of this photograph is a gravestone marked “Mother”. This piece discusses how motherhood severs parts of your identity into a multiplicity of lives. Making the parts of yourself that exist outside of that role blurry and undefined. The subject sits on the grave of a mother but exists after Francesca, begging the question who is she now?

Pregnant Girl Creek

Keetje Kuipers

There’s a girl leaned back against the chains of the bridge, clutching her belly

through the thin rayon of her dress like it’s covering the underside of the sun

while her friend tells her to tilt her head right or left for the photos

she’s taking with a phone, each turn making a stripe of pink

bangs flash across the girl’s face like the fan of a bird’s fragile wing,

and what I mean is that she doesn’t have much money, and also

that I know her, which isn’t possible since the girl I know is gone,

her children born and half-grown already, nothing of her own shimmering

left in this light-sieved moment but the memory of her sweetness, which was true as this creek is cold, even at the end when she’d lost her kids and was ashamed

of herself, and I think about how careless people like to say that it doesn’t cost

anything to be kind, but that some of us know the truth, which is that the price

of cracking yourself open to the world long enough to feel love for a stranger,

which is the same as feeling love for yourself, is dear, so that it hurts

more than a little to lean in as I pass by and spend it all on this girl, telling her how pretty those pictures are going to be.

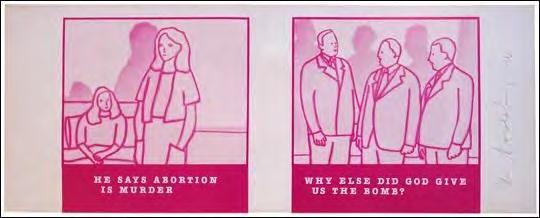

Ida Applebroog (American 1929- 2023)

So?, 1983

photolithograph diptych, offset-printed monochrome, 27.9 x 71.1 cm.,

Courtesy of the College of Wooster Art Museum

In So?, Ida Applebroog confronts anti-abortion rhetoric by placing it alongside language used to justify acts of mass violence. Using the visual simplicity of a comic strip, she exposes the contradictions in declaring “abortion is murder” while culturally rationalizing the devastation caused by the atomic bomb.

Divided into two panels, the work contrasts women stating, “he says abortion is murder,” with men in business suits replying, “why else did God give us the bomb.” Through this stark juxtaposition, Applebroog critiques the hypocrisy and power dynamics shaping political and personal narratives around life, death, and control.

Nature

be a mother

Julia Kolchinsky to pour : thunder : punch through potholes : hoping this will make something : anything : grow : she must be moths : mouth wide : wings panting for lightning : who else would strike herself : flame veining the air? who else would bear children to rise in spring : only to feel them cut months later? the moth’s charred outline on a log : the double wound : her children’s heads sinking : left to dry on another mother’s windowsill : who else would ask for such a violence?

Portrait of a Mother Holding Her Deceased Infant, Artist unknown (American) 1850s, Daguerreotype Image : 2 7/8 x 2 3/8 in. (7.3 x 6.03 cm)

Courtesy of Hope College, Kruizenga Art Museum. 2022.54

Death portraits came into existence during a period of high infant and child mortality and the increasingly less expensive technology of daguerreotypes was being perfected. Never before had so many people had the means to capture the likeness of their deceased loved one to mourn. Death portraits could be made for any kind of loved one, but they were especially popular for deceased children as these photos would be the only opportunity to preserve the likeness of the child.

“At dinner parties, she wanted to touch their throats and play with their long, tangled hair, wondered what it was like to wear sadness so close to the skin and be loved for it.”

Jessamine Chan, The School for Good Mothers

Traci Brimhall

We can't remember her name, but we remember where we buried her. In a blanket the color of a sky that refuses birds.

The illiterate owls interrogate us from the trees, and we answer, We don't know. Maybe we named her Dolores, for our grandmother,

meaning sadness, meaning the mild kisses of a priest. Maybe we called her Ruth, after the missionary who gave us

a rifle and counterfeit wine. We blindfolded our sister and tied her hands because she groped the fence looking for the rabid fox

we nailed to a post. Katydids sang with insistent summer urge and the cavalier moon grew more slender. In the coyote hour,

we offered benedictions for a child we may have named Aja, meaning unborn, meaning the stillness that entered us,

which is the stillness inside the burnt piano, which is also the woman we untie, who is the mother of stillness.

Copyright Credit: Traci Brimhall, "Stillborn Elegy" from Our Lady of the Ruins. Copyright © 2012 by Traci Brimhall. Reprinted by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Käthe Kollwitz (German 1867-1945)

Tod und Frau (Death and the Woman), 1910 Drypoint, 22 15/16 x 22 15/16 in.

Gift of Dean Hansell, Denison University Class of 1974.

DU2006.2.32

“Käthe Kollwitz creates a poignant depiction of a woman caught between the grip of death and her child. By her command of line and space, Kollwitz conveys an entire narrative in a compact composition. The arched shape of the woman’s body reflects the struggle she faces to stay alive. The dark shadow behind the skeleton underscores the unknown fate of death. At the same time, her child, climbing onto and grasping the mother, fights to not lose a loved one. The intense scene represents the painful grief of watching someone slip through your fingers.”

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth website

Ellen Bass

I didn’t know that when my mother died, her grave would be dug in my body. And when I weaken, she is here, dressing behind the closet door, hooking up her long-line cotton bra, then sliding the cups around to the front, leaning over and harnessing each heavy breast, setting the straps in the grooves on her shoulders, reins for the journey. She’s slicking her lips with Fire & Ice. She’s shoveling the car out of the snow. How many pints of Four Roses did she slide into exactly sized brown bags? How many cases of Pabst Blue Ribbon did she sling onto the counter? All the crumpled bills, steeped in the smells of the lives who’d handled them—their sweat, onions and grease, lumber and bleach—she opened her palm and smoothed each one. Then stacked them precisely, restoring order. And at ten, after the change fund was counted, the doors locked, she uncinched the girth, unbuckled the bridle. Cooked Cream of Wheat for my father, mixed a milkshake with Hershey’s syrup for me, and poured herself a single highball, placed on a yellow paper napkin. Years later, when I needed the nightly highball too, she gave me this story. She’d left my father in the hospital— this time they didn’t know if he’d live, but she had to get back to the store. Halfway she stopped at a diner and ordered coffee. She sat in the booth with her coat still on, crying, silently, just the tears rolling down, and the waitress never said a word, just kept refilling her cup.

Tracey Emin (English 1963 -)

How it feels, 1996

Single channel video (shot on Super 8), 22 min, 33 sec, (EMIN21144)

Courtesy of the Artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

“Arguably Emin’s most personal video work, How it Feels (1996) addresses the artist’s experience with her abortion. The film begins outside her doctor’s office in an old church in London, where Emin underwent the procedure six years prior. The off-camera voice prompts her with questions, as she talks openly to the viewer about her story. Emin describes her male doctor, who initially refused her permission to terminate the pregnancy. She speaks of her anger, moral confusion, heartbreak and guilt following the abortion. Walking through the city, she recollects the reasons for taking the decision, such as her basic need for survival and the reality of life as a struggling young artist. The film gives a difficult, yet empowering account of the physical and psychological dimensions of refusing motherhood.”

Xavier Hufkens Gallery website

Danusha Laméris

I always wanted a daughter, which is to say, I wanted a better self, flicked from my marrow — made flesh. I wanted this bone-of-my-bones to move in the world, exceptional and unharmed. Not this world. But a world almost exactly unlike it. Same paved streets and street cafés, same slow

unfurl of spring. Only in that world, the green of field and orchard is still wanton

Get Jane Edberg’s stories in your inbox Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

Enter your email Subscribe with winged things, their bellies powdered with the flowers’ gold dust.

“Daughter,” I say, and I mean a list of what ifs, a cacophony of sorrows.

I imagine her tall, lithe as willows. When I say Daughter,

I mean a match, ready to strike herself against the world that isn’t

this one. I mean luck. I mean a river empty of drowning. I mean an arrow aimed at an unnamed star. Who said a daughter is a needle in the heart?

I would take that needle, sew her a dress of yarrow and blood.

In the world not this one, I have a daughter. She is a long braid, a memory of fire. She goes before me, shining darkly, into a city — of gold, of salt — that I will never see.

Carmen Winant (American, 1983-)

My mother and eye, 2023

Courtesy of the artist.

For her notably personal project My Mother and Eye, Carmen Winant assembled hundreds of stills from films that the artist and her mother each made as teenagers driving across the US. In 1969, Winant’s mother traveled far from her family home for the first time, documenting her trip from Los Angeles to Niagara Falls on Super 8 film. In 2001, with a 35mm camera in hand, Winant chronicled her own reverse journey from Philadelphia to Los Angeles. The composition shows a different exploration of recognizable landmarks, interwoven narratives, and the horizon line. The resulting montage collapse the two journeys across time and landscapes, unfolding individual experiences of newfound freedom, buoyancy, and the power of self representation.

Public Art Fund

Kelly Grace Thomas

A gallon of water weighs 8.3 pounds. Seagulls are always hungry. My daughter’s name is Nova. I am a mother. I’ve lost a mother.

It happened so slow: she became less and less as the red of chemo ran through her blood.

It happened so fast: chosen by the birth parents a month after paperwork. The blinkless doctor saying Stage Four.

Then the moments that hover—fog over the gray Pacific: My mother’s hands, liver-spotted against the pink ocean of Nova’s newborn skin. Her voice caught in the last chorus of Row, Row, Row Your Boat. I’m not sure I’ll ever forgive.

My mother kept a gallon of water next to her bed. On good days she practiced picking it up. One day, she said,

I’ll be strong enough to lift her.

Sheilah Restack (Canadian, 1975-) and Dani ReStack (American, 1972-)

May you choose your own form of recognition (for SER), 2022 174 gold-leafed polaroids, Angle iron, Drawing by Dani ReStack. Courtesy of The Blue Building Gallery.

174 gold leafed polaroids containing the image of a little girl we have been a foster family for since 2021. We cannot show her image but want to make connection in the ways that we know to show love in the materials of our practice, to offer a document that is photographic and protective, to share a wish for her to choose her own form of recognition. Each polaroid is hand gold leafed, and drawn on by Dani ReStack.

Bomb Magazine

Hyejung Kook

Dark mares of the moon—foaming, cold, nectar, tranquility facing crises, fecundity—you are clearest at first quarter, half-lit, songpyeon-shaped. Tonight again the baby cried for the sight of you—he is always crying for the moon or horses or apples— fighting sleep, craning his neck up to stare and stare, unblinking, little hands pressed against the cold windowpane, but you were invisible behind clouds and light rain. Halfway between Sanggang, the fall of frost, and Ipdong, the onset of winter— the harvest is done, the trees and grass yellowing. I have no chrysanthemum wine, but the baby left half an apple, the flesh still crisp and white. Tonight at least I’ll sleep with sweetness in my mouth.