Introduction: A Two-Man Research Machine

Abstract Having become acquainted during legal internships in Versailles, during their nine months travel in America (1830/31) the friendship of Tocqueville and Beaumont metamorphosed effectively into a two-man ‘research machine’ concerned with the question of what the emergence of modern democracy in America entailed for France, Europe and beyond. Their joint trip to America was only the beginning; other travels would follow, to England and Ireland, and later to Algeria. Tocqueville’s and Beaumont’s lives became entwined, not just by travelling but also by writing together, by discussing each other’s work and by ‘politicking’ jointly in the French National Assembly – and after 1848 in the Constituent Assembly. There was an agreed division of labour and joint undertakings, both showing consistent overlapping interests and concerns but also different emphases in their work despite the many commonalities. Tocqueville looked at the whole and aimed at grand-scale comparisons. Beaumont was impressed with his friend’s ability to look at the wider context but appeared to be more focused and able to concentrate on specific themes; he was also in many ways the darker shadow of Tocqueville, concerned with those who had been left behind by the emergence of modern democracy.

Keywords American and French democracies • Democratic revolution • Aristocratic liberalism • Tocqueville • Beaumont

© The Author(s) 2018

A. Hess, Tocqueville and Beaumont, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69667-6_1

The main aim of this book is to understand the birth pangs of modern democracy after the ‘Democratic Revolutions’ (R. R. Palmer) – in essence the American and the French Revolutions – whose reverberations, knockon effects and unresolved problems could be felt for much of the nineteenth century and beyond, in many countries. I maintain that the work and political careers of Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont are a fascinating lens through which those democratic revolutions and their consequences, contradictions, problems and unfulfilled promises can be studied.1

There exist numerous studies dealing with Tocqueville (1805–59) and his work: two long biographies (De Jardin 1988; Brogan 2006), many monographs and even more articles that discuss Tocqueville’s Democracy in America or his Ancien Régime in great detail, not to speak of the many titles that address other aspects of Tocqueville’s work or that relate to themes and topics addressed in Tocqueville’s pioneering studies (see, for example, the various contributions gathered in The Cambridge Companion to Tocqueville (2006) or The Tocqueville Review (1979–)).

Considerably less has been published about the contributions of Tocqueville’s friend, co-traveller, co-writer and life-long friend, Gustave de Beaumont (1802–66), and even less about their collaboration. A recent collection of Tocqueville and Beaumont’s writings on America (Tocqueville and Beaumont 2010) attempts to examine their joint efforts in studying the emerging American democracy. It gathers some of the central texts of the two friends in one volume. However, while the publication makes their joint output more easily available, it is rather disappointing in terms of the interpretation of the nature of the collaboration between the two men. Once again, the focus is, if at all, on their differences, despite the overwhelming evidence of shared preoccupations and work almost through their entire lives. Such insistence on the differences instead of the similarities and overlaps neglects the arguments made in the pioneering work of Drescher (1964, 1968), and more recently reasserted in Drolet (2003), Garvin and Hess (2006, 2009) and Hess (2009), all of whom have pointed out that the commonalities and collaboration between the two friends need to be taken more seriously and studied in greater detail. Such emphasis does of course not neglect the real differences between the two writers; it just serves as a reminder to give credit to joint efforts where credit is due.

The Case for a JoinT sTudy

If this description has any validity – and I maintain throughout this book that it does – it makes little sense to celebrate Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835/1840) without considering Beaumont’s darker and more sceptical pendant Marie, Or, Slavery in the United States (1835) or giving his Ireland study (1839) its due. As shown in the three-volume correspondence of Tocqueville and Beaumont in the former’s Oeuvres Complètes (1967, in translation partly available in Tocqueville 1985 and 2006 and Tocqueville and Beaumont 2010), every sentence, every paragraph of any of the books Tocqueville and Beaumont ever wrote, be it as sole author or together (as was the case in the Penitentiary study), was read by the other and discussed between the two friends. The same applies to their cooperation as members of the French National Assembly where they worked together on several issues, ranging from the abolition of slavery, through debates relating to colonial and imperial policies to matters of social reform. Similar synergies are detectable when Tocqueville and Beaumont worked in the Constitutional Commission after the 1848 Revolution and later when Tocqueville became foreign minister and Beaumont French ambassador to London and Vienna. After their enforced retirement following Louis Napoleon’s coup d’état in 1851 they remained in close contact. When Tocqueville was struggling with tuberculosis Beaumont joined him in Cannes and took care of him. And even after Tocqueville’s death Beaumont remained deeply committed to their friendship: he wrote the first memoir of Tocqueville and also edited the collected works of his deceased friend (Tocqueville 1862).

This text is the first concise attempt to see Tocqueville and Beaumont as partners in their attempt to study the birth pangs of modern democracy and to point out each other’s qualities and strengths while also addressing some of their different emphases. Albeit relatively short and in conformity with the format of the Pivot Series in which it appears, this is, at least as far as I am aware, the first study that attempts to give full credit to the collaborative nature of the extraordinary two-man ‘research machine’ (Tocqueville 2010: 29). It tries to de-mystify and debunk the role of Tocqueville as the ‘sole genius’ by paying due respect to Beaumont’s contribution or to Beaumont as a listener, correspondent, or sometimes just simply as a sounding board for ideas. It is, to put it differently, about getting the balance right rather than prolonging the myth of the solitary ‘democratic sphynx’.

This book intends, first, to argue in favour of the potential interpretative benefits when Tocqueville and Beaumont are seen in context and in their interaction. Second, it tries to reap the advantages from such a vantage point, particularly when discussing the problems, contradictions and hopes associated with the development of modern democracy. What will hopefully become clear in the context is that Beaumont’s efforts and writings function as a kind of corrective mechanism, able to throw light onto Tocqueville’s occasional blind spots and silences. This latter point is no arbitrary postfactum construction or a reprojection; it simply takes seriously the division of labour on which Tocqueville and Beaumont agreed from an early stage. The two friends knew about their similarities and differences; that’s why they agreed on both collaboration and their division of labour.

However, before delving into the past one concern or objection should perhaps be dealt with and answered right from the start. Tocqueville knew not only Beaumont but had other friends and acquaintances with whom he was in regular contact, for example Louis de Kergorlay, John Stuart Mill and William Nassau Senior. So why focus just on the relationship between Tocqueville and Beaumont? The answer is that it was Beaumont, and only Beaumont, with whom Tocqueville not only shared some crucial experiences such as their joint travels to America, England and Ireland, and later Algeria but also the experiences of a legal apprenticeship at Versailles, an important joint publication (the Penitentiary book about American prisons), a simultaneous rise to fame (both were awarded the Montyon Prize for their publications, and both were later appointed to the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques); furthermore, both had political careers in the French Assembly and later in the Constituent Assembly, both entered the diplomatic service (Tocqueville as Foreign Minister and Beaumont as ambassador, first to London and later to Vienna), and both withdrew simultaneously from politics and public life in 1851. After Tocqueville’s death Beaumont would become the first editor of Tocqueville’s collected writings, an indicator of their intellectual proximity, their joint work and their shared interests. Finally, there is the lifelong exchange of ideas and letters as testified by the already mentioned three volumes of correspondence between Beaumont and Tocqueville (now part of the Gallimard edition of Tocqueville’s collected writings and also partly available in translation in various editions).

In their letters, each showed admiration for the other. On board the vessel that took the two friends to America Beaumont wrote to his father about his travel companion: “There is great loftiness in his ideas and great

nobility in his soul. The better I know him, the more I like him. Our lives are now joined together. It is clear that our destinies are and will always be linked. This tie enlivens our friendship and brings us closer together.” And in anticipation of what was to come he notes “we are meditating ambitious projects” (both quotes in Tocqueville 2010: 6). Reflecting about their common experiences and their differences in terms of passions and interests and how, related to that, their minds worked, Tocqueville commented in a letter to Beaumont written many years later, in 1839, at a time when Tocqueville had put the finishing touches on the second volume of Democracy and Beaumont had just finished his Ireland book: “Your mind is indivisible. You must not pity yourself too much for this, because it is a sign of strength. You are always ablaze, but you catch fire for only one thing at a time, and you do not have any curiosity or interest in anything else. It is for that reason that within the greatest intimacy, we have always had points at which we did not touch and never reached each other. I have an insatiable, ardent curiosity, which is always carrying me to the right and to the left of my way. Yours leads you just as impetuously, but always toward a single object.” A few lines further down Tocqueville asks, clearly puzzled by the conundrum of their joint efforts but also their different approaches: “Which of us is right in the way he conducts his mind? In truth, I have no idea.” He concludes: “I believe that the result will always be that you will know better than I, and I more than you” (in Tocqueville 1985: 130f).

The friendship seemed to have been clouded over only once, and then only for a few weeks, in 1844. The disagreement developed over an education bill, which Tocqueville had opposed in the French Assembly, a stance which he expected Beaumont to follow publicly. Beaumont did in fact support Tocqueville’s position but also tried to remain faithful to the editorial line of his paper Le Siècle, which took a different line than Le Commerce, the paper Tocqueville had used as an outlet. Through the intervention of various friends and acquaintances the two were soon reconciled. Each acknowledged afterwards that the dispute had taken them too far in their passions; the disagreement ended with both asking each other for understanding and forgiveness.

There was simply nobody else in Tocqueville’s life who would have had the same kind of influence and sense of friendship or would have had that kind of sustained joined experience and exchange, and perhaps most importantly, mutual trust. This, to repeat, does not mean that there weren’t also some differences on occasion, as for example acknowledged in the letters mentioned above. However, the point is that hinting at such INTRODUCTION:

differences in terms of temperament, talent or opinion only makes sense when one also takes into consideration the many bonds and common interests between the two friends.

a Brief overview: Parallel lives, differenT Passions

Gustave de Beaumont de Bonninière was born 6 February 1802, at Beaumont-la-Chartre in the Sarthe. Beaumont’s parents were both of French aristocratic background and the family had always been linked to the more enlightened circles of the French upper class. Indeed, Lafayette, the famous aristocratic soldier who had fought alongside Washington against the British during the American War of Independence, was Beaumont’s grandfather, and therefore an early American connection. Not much is known of how Beaumont spent his childhood. His first appearance in the historical record as an adult is as a juge auditeur and then as a deputy public prosecutor at the court of Versailles. It was also at Versailles that Beaumont first met Alexis de Tocqueville (born 1805), a fellow student who had been pursuing a similar legal career. The two young men shared more than just the fact that both came from aristocratic backgrounds and were aspirant lawyers. They clicked personally, intellectually and politically; a friendship soon developed between Alexis and Gustave and in the following years the two developed their fabled habit of reading and studying together. Both had an interest in political economy and were particularly taken by the theories of Jean-Baptiste Say. Again, both attended the history lectures of François Guizot, a well-known liberal historian. They were particularly influenced by Guizot’s arguments concerning the history and course of French civilisation.

The July Revolution (1830) brought an end to the reign of Charles X, and both young men were faced with tough decisions. All officials were required to take an oath of loyalty to the new regime of Louis-Philippe and after much soul-searching the two friends finally decided to take the oath to secure their legal careers. Since Tocqueville and Beaumont were deeply worried about the possible intentions of the new regime they also began to make contingency plans. Part of their plan was, quite simply, to take some time out by getting away from France. Beaumont had already sketched a short proposal for studying the French prison system in which he had adumbrated a further, more detailed investigation from a comparative perspective. A short while later, the two friends received the green light for their project. The pair were commissioned to travel together to

America with the purpose of investigating the new prison systems of the United States to find out to what extent they resembled or differed from the French system and if there were any innovations which the French authorities might profitably study. In April 1831, the two friends left Le Havre for America where they were to stay until February 1832. They first arrived in New York and spent a few weeks in the city and its environs. From New York they went to Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington before returning to New York. Two further excursions were also part of the trip, one to the Northwest and Canada, and another down the Mississippi river to New Orleans.

The trip turned out to be a success in more than one respect. The two friends managed to gather plenty of information about prisons and the American penitentiary systems. However, the most important result of their journey was the discovery that the comparison of prison systems not only provided the organisational pretext for but also some insights into the new, democratic ‘philosophy’ and its practices. They argued that the way a penitentiary system treats its prisoners reveals how a regime treats its individual citizens or subjects in general. American prisons apparently didn’t simply let their prisoners rot in their cells but attempted to improve their character through various means, either by putting them to work or by isolating them. Although far from perfect from today’s perspective, this new ‘enlightened’ attitude was the true revelation of the New World in the eyes of the two Frenchmen. Yet it was in the end less the prison environment than their observations of American civil society, the political institutions, American mores and attitudes, and the society’s new democratic and egalitarian approach to social relations that showed France (and perhaps Europe) its hoped-for future.

On their return to France in the spring of 1832 Beaumont immediately started writing their joint report. Tocqueville at first found himself unable to put his own thoughts into writing; he only contributed at the final stages of the draft and supplied statistics and other useful data. In the meantime, news had spread to their superiors and the new regime, that the pair were suffering from an apparently incurable new spiritual disease: love of democracy. Both found themselves peremptorily dismissed from their duties as public judges. However, since both remained registered at the bar this decision does not seem to have threatened their career prospects in any major way. As it turned out, the dismissal did no harm to their political careers.

Early in 1833 their report was finally published. The Penitentiary System of the United States and its Application to France proved to be an immediate success. The study was widely discussed and was awarded the prestigious Montyon prize. Second and third editions followed in 1836 and 1844. Furthermore, the book soon appeared in translations; it was particularly widely read and appreciated in America and Germany. The success of The Penitentiary System created a snowball effect that prompted the two friends to carry their original intentions and pursuits further, i.e., to write about what could be learned from the American experiment with democracy. While Beaumont embarked on a new project, a kind of sociologically-inspired novel about the more tragic aspects of their American experiences such as slavery and the fate of its indigenous people, Tocqueville wrote the first part of his monumental book, which focussed more on the larger picture of American democracy, that is, its institutions and habits of the heart.

In retrospect, it seems that the year 1835 saw a breakthrough for the two friends. Earlier, in the summer of 1833, Tocqueville had travelled to England for the first time. He had hoped that England, the mother country of America, would provide further insight and perhaps some intellectual key to an understanding of how the young American republic had been shaped; but no clear clues seemed to have emerged during his first trip across the Channel. Furthermore, he was apparently treated like a nobody. However, two years later, Tocqueville was received very differently; the first instalment of Democracy in America had appeared in France and an English translation was imminent. In London, Tocqueville and Beaumont met the translator of Democracy, Henry Reeve. Other contacts proved to be equally crucial for getting to know English society and its political system; in particular the help and advice of two eminent political economists, John Stuart Mill and Nassau William Senior, were central.

On this occasion Tocqueville and Beaumont continued their travels and went as far as Ireland, where they toured for six weeks. The two friends used Dublin as a base and stayed in the city for a few days before starting on a round-trip (but leaving out Ulster). While travelling together, they also talked about their publication plans, just as they had done earlier in America and afterwards in France. The difference this time was that they were both published authors. Now they had greater experience, and they agreed on two things. First, they established that they would respect each other’s publication plans and individual research interests. Beaumont would write on the unfulfilled promises of American democracy, the plight of African

Americans and American Indians, and the colonial relationship between England and Ireland, while Tocqueville would focus mainly on America’s political system and the prospects for both American and European democracy. Second, to prevent possible misunderstandings, overlapping of research effort or any intellectual turf war they decided also that they would make a point of showing each other their work before publication.

As pointed out above, the year 1835 not only saw Tocqueville’s publication of the first volume of Democracy in America but also the publication of Beaumont’s Marie, or Slavery in the United States. While Democracy looked mainly at America’s political system, Marie was an attempt to take a closer look at the seamier side of American society. The two books must be read as companion volumes to make complete sense of America and to grasp the two men’s joint understanding of the country. Marie, like Democracy in America, was an enormous success and was reprinted numerous times in French over the following decades. However, Marie was mainly a French phenomenon. In America, it remained unpublished for over a century; American slavery was apparently a more popular topic in France (and Europe) and, to put it very gently, the book did perhaps not harmonise well with American tendencies toward self-congratulation. The two books paid off in career terms; Tocqueville’s tome got him elected to the French Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, thus emulating Beaumont’s Montyon prize. Their publishing triumphs were also accompanied by personal fulfilment; Beaumont married his second cousin Clémentine de Lafayette, the granddaughter of General Lafayette, while Tocqueville married an Englishwoman, Mary Motley. The two friends also made a promising start to their political careers by being elected to the French Assembly.

During the summer of 1837 Beaumont paid a second visit to England and Ireland, this time on his own, to gather material for his Ireland project. Two years later L’Irlande finally appeared as a two-volume study. William Taylor’s translation of the book into English was published later that year. It turned out to be an intellectual tour de force and proved to be even more of a hit than the prison and the slavery book. During the author’s own life time the book saw seven French reprints, and once again he was awarded the Montyon prize on the basis of his new book. He also became a member of the French Academy of Moral and Political Sciences.

On top of their publishing record and their academic achievements, but quite separate from these in terms of responsible public activities, Tocqueville and Beaumont remained liberal aristocrats dedicated to defending liberty. They retained a social conscience, yet without committing themselves to a

new ideology or Weltanschauung. Unlike many other liberals they also remained internationalist in outlook; their opinions were not confined to internal French issues – though of course France’s public affairs and interests would always remain core concerns.

By now the friends had perfected their division of labour, by which they acted as a two-man machine, complementing and supporting each other’s efforts. Thus, for example, Tocqueville presented a report on the abolition of slavery to Parliament while Beaumont simultaneously presented a petition to the Chamber on behalf of the French Abolitionist Society. In 1841, they travelled together to Algeria, again an experience that would lead to both looking for more coherent French policies in North Africa. Tocqueville and Beaumont were later to become members of the Parliamentary Commission on Algeria and they always remained interested in the subject as long as their political careers lasted. Their unique personal and intellectual friendship continued.

The Revolution of 1848 ushered in the Second Republic. Tocqueville and Beaumont became members of the new Constituent Assembly and both were selected to join its Constitutional Commission. In the following year Tocqueville became France’s Minister for Foreign Affairs while Beaumont was appointed as ambassador first to London then to Vienna. Yet, neither Tocqueville’s increased self-esteem derived from the elevation in political status, nor his achievements in a relatively brief period as Foreign Minister, seemed to have been of lasting value – at least not in terms of his notorious insecurities and inclination to self-doubt. However, after having been dismissed from his post due to the so-called Rome crisis and it repercussion back in France, Tocqueville (less so Beaumont) seemed to have harboured the idea that despite the resignation he could still have the Prime Minister’s ear and influence him. This turned out to be an illusion. Tocqueville and Beaumont were arrested and briefly imprisoned for opposing Louis Napoleon’s coup against the Second Republic. Their arrest, and their prompt release, marked their withdrawal from public affairs and the ‘official’ end of two remarkable political careers.

Tocqueville retreated to his home in the countryside and continued his intellectual reflections, Souvenirs (written 1850–51, published only posthumously in 1893) and L’Ancien Régime (1856) being the results. Beaumont was less fortunate and found that he could not devote all his time to writing. He had to attend to financial matters out of economic necessity connected with a legally encumbered inheritance. Only occasionally could Beaumont manage to surface from his retreat, to appear, for example, in the Académie de Sciences Morales et Politiques.

After Tocqueville’s death in January 1859, Beaumont began editing his friend’s published and unpublished writings. The first two volumes, a selection of Tocqueville’s unpublished letters and manuscripts, became later part of a six-volume set which appeared between 1861 and 1866. They provided the foundation on which Tocqueville’s later fame would come to rest. In contrast, Beaumont never achieved the same prominent status as his friend and soon his name became forgotten. Today we can read Tocqueville’s and Beaumont’s works in tandem and dissect in fascinating detail how, even though both addressed the birth pangs of modern democracy, they revealed fine nuances and different emphases in relation to those developments. In this concise book, I will try to show that Tocqueville leans more to an interpretation of the main structures of emerging democratic societies, dealing principally with the most important institutional features, ‘psychological’ and cultural conditions, and the legal systems that new democracies require. Tocqueville was also interested in drawing attention to the new inherent dangers of democracy such as the tyranny of the majority. In contrast, Beaumont looked at those features that were not (yet) contained in, or were excluded from democracy’s emergence and take-off: women, American Natives, Blacks, the Irish, the underclass – or any mix thereof. Taken together, both give us an idea of the complicated processes of democratic formation.

a revisionisT aPProaCh To arisToCraTiC liBeralism

Before discussing the material at hand, I would like to elaborate briefly on the epistemological context of this study. As the German historian Reinhard Koselleck has pointed out, Tocqueville – and by extension we must add Beaumont – were prime examples of a liberal conscience at work in a time of radical change.2 Koselleck also noted that “Tocqueville diagnosed liberalism as [an expression of] a time of transition, whose problems he saw more succinctly, because he didn’t interpret this time as being [per se] progressive.” Tocqueville’s unique understanding of liberalism stands out today because “he did not join sides, he did not confuse wishful thinking with historical analysis and political diagnosis. He looked at long-term trends such as the administrative state and industrial society, which pointed beyond his own life span. He undertook the study of institutions and customs, societies and religious behaviour, economic necessities, the means of staying in power, the formation of parties and constitutional architectures, including their manifold functional dependencies, yet without mixing

them with personal and openly declared hopes. For this very reason, he could come up with alternative prognoses for [historical] conditions, which because they avoided the confusion of wishful thinking with possibilities, had the potential to stimulate action. It was critical distance which made his lasting and fascinating epistemological surplus thinking possible and which guided his judgement. Furthermore, Tocqueville also used anticipation and hypothesis, which made the consecutive processes of democratisation empirically verifiable…The main contribution, however, consisted of having left behind the interest-led dogmatism of progress in order to develop a theory of modern history, which pays dues to the complexity of our modern times”. In that sense, Koselleck concluded, Tocqueville clearly “surpassed other political expressions of classical liberalism” (both quotes in Koselleck 2010: 222–223; translation and additional square brackets added for clarification by AH).

It is worthwhile noting that liberalism thus understood was not necessarily a triumphant political force; rather, Koselleck sees the history of liberalism as “a history of self-consumption”, as “a prize without which its success could not be had”. He points out that “to the extent to which liberal demands prevailed, liberalism lost out as a political movement in terms of force, power, and influence” (ibid: 208). Thus, Tocqueville became a paradigmatic and to a certain extent even exceptional thinker because he found himself, apart from one short period in 1848, never on the victorious side but always on the losing side of history. Tocqueville’s name became synonymous with a new type of intellectual reflection: the critical observer as historical ‘loser’, a person who saw himself as having been rolled over and been made redundant by the new times and conditions but who nevertheless tried to understand what had happened in order to draw lessons for the present and, perhaps, the future. This is, according to Koselleck, the very reason we read Tocqueville today with such benefit: “While in the short run history may have been made by victors, in the long run the historical-epistemological surplus stems from the defeated” (Koselleck 2000: 68).

Despite his own personal insecurities and re-occurring self-doubts3 Tocqueville had good antennae for what was new in his time and what his potential role was within it. His travelling experiences in America, Britain and beyond had not only facilitated a comparative view of emerging democracies and their progress of formation but also a sense of sharp insight in terms of what was possible for someone who belonged to a defeated and redundant class (by extension the same characterisation also applied to Beaumont). In a letter to Henry Reeve, his English translator, he revealed his motivations and what drove him: “People attribute either democratic or

aristocratic prejudices to me. I might have had either had I been born in another century and another country. But the accident of my birth made it quite easy for me to avoid both. I came into the world at the end of a long revolution, which, after destroying the old state, created nothing durable in its place. Aristocracy was already dead when my life began, and democracy did not yet exist. Instinct could not therefore impel me blindly toward one or the other. I lived in a country that for forty years had tried a bit of everything without settling definitely on anything; hence, I did not easily succumb to political illusions. Since I belonged to the old aristocracy of my country, I felt no hatred toward or natural jealousy of the aristocracy, and since that aristocracy had been destroyed, I felt no natural love for it either, because one forms strong attachments only to the living. I was therefore close enough to know it well yet distant enough to judge it dispassionately. I would say as much about the democratic element. No family memory or personal interest gave me a natural or necessary inclination toward democracy, but I had suffered no personal injury from it. I had no particular grounds to love or hate it apart from those provided by reason. In short, I was so perfectly balanced between past and future that I did not feel naturally and instinctively drawn toward either, and it took no great effort for me to contemplate both in tranquility” (Tocqueville 2010: 573).

While such a statement shows some remarkable capacity for critical selfreflexion, the image of equal distance between inherited class and future democratic prospect threatens to paint over some of the finer points of Tocqueville’s existential condition and the liberal views which emerged from it. This begs the question of how can one explain his unique standpoint?

It was the French historian François Furet who first pointed out that there were basically two approaches to looking at the intellectual origins of Tocqueville’s – and, again by extension, Beaumont’s – thought: one was to study the influences of his/their thought and see how much he/ they made use of them and find out whether they are detectable and how much he/they modified or dissented from them, if at all. The second approach was to ask what kind of problems did Tocqueville (and Beaumont) face and how did they try to solve them (Furet 1985/86, reprinted in Laurence Guellec, ed. 2005: 121–140).

However, Furet also stressed that the two approaches were not mutually exclusive. He actually argued strongly in favour of a combination of the two, with the main focus on the second approach and the first approach becoming subservient to the second. The reasons given were that Tocqueville had been exposed to and trained in a traditional scholarly INTRODUCTION: A TWO-MAN

manner, and that influences of Rousseau, Montesquieu, Pascal and Jansenism, and more contemporary writers such as Guizot, Madame de Stael and others were detectable throughout his work. At the same time Furet pointed out that while Tocqueville made use of these thinkers or engaged with their work, he always remained reluctant to acknowledge or to reveal his sources fully. The reason for this, argued Furet, was that he was not interested in writing simply a scholarly work. His energy was reserved for something else: as a ‘late’ aristocrat who had been born into a new age in which democratic aspirations and hopes were omnipresent, and as somebody whose own family had been terrorised and had suffered badly under the French Revolution, his aim was first and foremost to address the big existential question of his time: how could liberty be preserved at a time of inevitable democratic claims, including demands for greater equality? Furet concluded: “[Tocqueville] thought in sociological rather than historical terms. Accordingly, his two principles of social organisation, the aristocratic and the democratic, encompassed and coloured all aspects of society, the political as well as the social” (ibid: 134).4 Tocqueville clearly realised, and to a certain extent accepted, the inevitable rise of democracy and its claims; yet he also observed that with the rise of democracy came not only claims about equality and standing but also the dangers of diminished liberty through a new Weltanschauung, which in its more radical variant took on the form of socialist ideas, intended to invent society anew.

In what follows I will try to take Furet’s advice seriously: I will make use of and discuss some of the intellectual influences, but my main focus will remain predominantly on the existential motives and dimensions, and that means in the first instance the possibilities and limitations of both Tocqueville’s and Beaumont’s aristocratic liberalism: the search for how liberty can be defended and maintained under democratic conditions and the latter’s pressing demands for more equality. However, I also maintain at the same time that there are two underdeveloped points in Furet’s argumentation, which need to be addressed in order fully to appreciate his original ‘existentialist’ claim: first, there is no reason to think that the argument about Tocqueville’s aristocratic liberalism wouldn’t apply to Beaumont as well. It may be harder to detect due perhaps to a variation in emphasis in Beaumont’s case. Compared to his friend he seemed to have had a different, more open personality, and showed more passion about those who had been excluded from the democratic process. Being passionate about the excluded was perhaps not an obvious aristocratic habit or trait but, as the joint discussions between the two friends show, it was there nevertheless.

Second, and in relation to Furet’s observation of major differences between Tocqueville as the young author who wrote Democracy in America and the later author who wrote L’Ancien Régime, 5 I think that his argument somewhat overstates the differences between the two, instead of seeing that long learning curve that Tocqueville’s and Beaumont’s existential notion had been subject to and that responded to the finer aspects of the new conditions and unique constellations that they encountered, a learning curve that finds perhaps its most dramatic expression in Tocqueville’s Recollections. In line with such a perception I argue in this book that Tocqueville’s and Beaumont’s aristocratic liberalism does not amount to any grand gesture, theory, scheme, or elaborated world view, that emerges or manifests itself at one point and is then maintained without modifications or changes. What Tocqueville and Beaumont defended and advocated was in its simplest form a non-utilitarian notion of liberty, which more often than not revealed itself in opposition to certain movements, people and positions some individuals held. This means that only by looking at the various constellations and periods will the observer be able to identify what Tocqueville and Beaumont meant by holding on to non-utilitarian notions of liberty.6 I will come back to this point in each of the following chapters and will also reflect on it in the conclusion.

Most important perhaps, and here I return once again to the point made earlier by referring to Koselleck, we must realise that during their lifetimes Tocqueville and Beaumont were actually never on the winning side of history. Starting with the French Revolution, through the first Empire, the Restoration, the Second Republic and, finally, the Second Empire they were never fully in charge or on the side of the victors, apart perhaps from a relatively brief period which lasted just a few months during the events of 1848, and during which both confessed that they had become republicans out of necessity. This ‘losing’ aspect is part of Tocqueville’s and Beaumont’s existential condition and journey. It is exactly the realisation and the insights stemming from historical defeat that make Tocqueville’s and Beaumont’s writings such an intellectually enriching and stimulating read, particularly considering the added benefit of looking at their joint work in context. History, as Koselleck has correctly stressed, is often written by the winners or the powerful; however, the critical insights and lessons stem mostly from those who have been defeated. Tocqueville’s and Beaumont’s study of the birth pangs of modern democracy seems to be proof of that.7

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

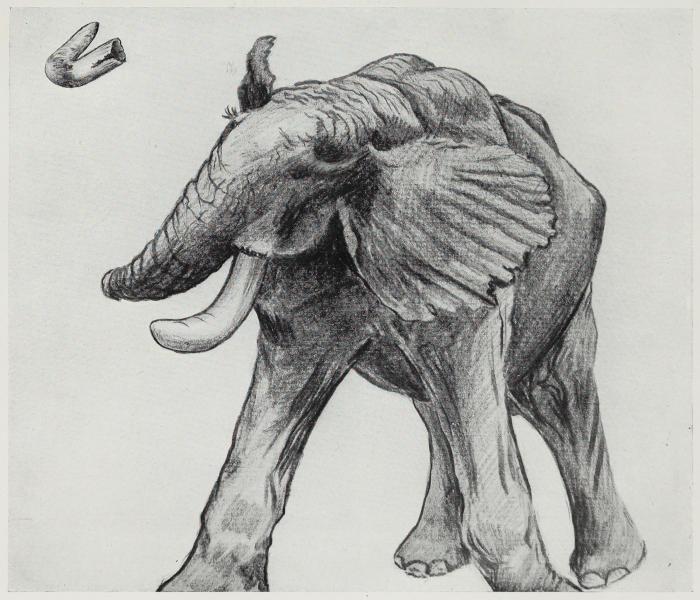

THE POSITION OF THE BRAIN WHEN THE HEAD IS VIEWED FROM THE FRONT

LOCATING THE BRAIN WITH THE SIDE OF THE HEAD TO THE SPORTSMAN

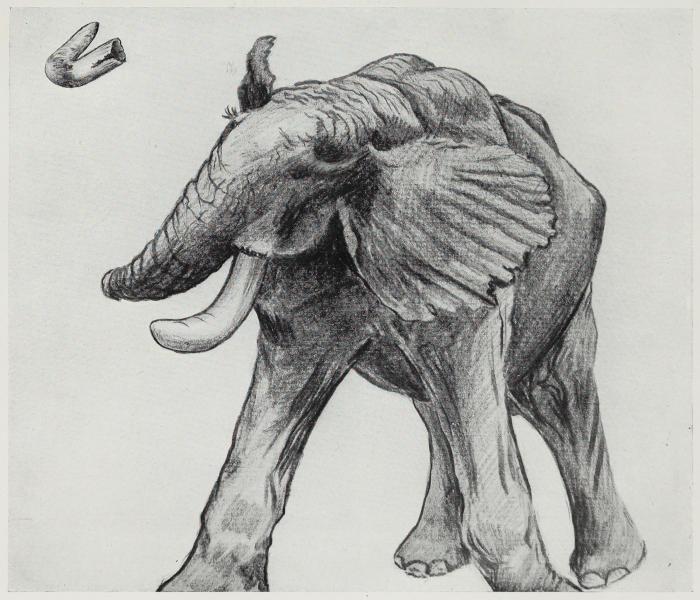

THE ELEPHANT, AFTER THE BRAIN SHOT, DIES QUIETLY AND THE OTHERS DO NOT TAKE ALARM

The greatest disadvantage the brain shot has is the difficulty of locating the comparatively small brain in the enormous head. The best way is, of course, to kill an elephant by the heart shot and very carefully to dissect the head, thereby finding out the position of the brain in relation to the prominent points or marks on the head, such as the eyes and ear holes. Unfortunately for this scheme, the head is never in the same position when the animal is dead as when alive, as an elephant hardly ever dies kneeling when a body shot has been given him.

The experienced elephant shot can reach the brain from almost any angle, and with the head in almost any position. But the novice will be well advised to try the broadside shot only Having mastered this and studied the frontal shot, he may then try it. When successful with the above two shots he may be able to reach the zenith of the elephant hunter’s ambition, i.e., to kill instantaneously any of these huge pachyderms with one tiny nickel pencil-like bullet when moving or stationary and from any angle.

From the point of view of danger to the hunter, should a miss occur, an ineffective shot in the head does not appear to have the enraging effect a body shot elsewhere than in the vitals sometimes has. Should the bullet miss the brain, but still pass sufficiently close to it to stun the animal, he will drop to every appearance dead. If no convulsive jerking of the limbs is noticed he is only stunned, and should be given another shot, as otherwise he will soon get up and make off as if nothing had touched him.

IV

AFRICAN “MEDICINE” OR WITCHCRAFT AND ITS BEARING ON SPORT

The ruling factor in the pagan African’s life is witchcraft, generally called throughout the continent “medicine.” All his doings are ruled by it. No venture can be undertaken without it. Should he be going into the bush on some trivial project he will pick up a stone and deposit it on what has through years become a huge pile. This is to propitiate some spirit. But this apparently does not fully ensure the success of the expedition, for should a certain species of bird call on the wrong side of the road the whole affair is off and he returns to his village to wait until another day when the omens are good.

In illness he recognises no natural laws; all is ascribed to medicine on the part of some enemy. Should his wife fail to produce the yearly baby, someone is making medicine against him through her. Hunting or raiding ventures are never launched without weeks of medicine making. The regular practitioners of this medicine are called “medicine men” or witch doctors. Their power is enormous and is hardly fully realised even by the European administrations, although several African penal codes now contain legislative efforts to curtail the practice of the evil eye and the black arts. These medicine men have always appeared to me to be extremely shrewd and cunning men who yet really believed in their powers. While all goes well their lot is an enviable one. Gifts of food are showered upon them. I suspect that they secretly eat the fowls and goats which are brought as sacrifices to propitiate the spirits: at any rate, these seem to disappear in a mysterious manner. Beer and women are theirs for the asking as long as all goes well. But, should the medicine man have a run of ill luck in his practice and be not too firmly established, he sometimes comes to grief. The most frequent cause of their downfall appears to occur in the foretelling of rain. Supposing a dry year happens to come along, as it so frequently does in Africa, everyone to save his crops resorts to the medicine man. They take to him paltry presents to begin with. No rain. They give him fowls, sheep and goats. Still no rain. They discuss it among themselves and conclude that he is not yet satisfied. More presents are given to him and, maybe, he is asked why he has not yet made the rain come. Never at a loss, he explains that there is a strong combination up against him, a very strong one, with which he is battling day and night. If he only had a bullock to sacrifice to such and such a spirit he might be able to overcome the

opposition. And so it goes on. Cases are known among rich tribes where the medicine man has enriched himself with dozens of head of cattle and women. At this stage should rain appear all is well, and the medicine man is acclaimed the best of fellows and the greatest of the fraternity. But should its appearance be so tardy that the crops fail, then that medicine man has lost his job and has to flee to some far tribe. If he be caught he will, most probably, be stoned or clubbed to death.

To the elephant hunter the medicine man can sometimes be of great assistance. I once consulted a medicine man about a plague of honey-guides. These are African birds about the size of a yellowhammer, which have the extraordinary habit of locating wild bees’ nests and leading man to them by fluttering along in front of him, at the same time keeping up a continuous and penetrating twittering until the particular tree in which the nest is situated is reached. After the native has robbed the nest of its honey, by the aid of smoke and fire, he throws on the ground a portion—sometimes very small—of the grub-filled comb as a reward for the bird.

My experience occurred just after the big bush fires, when elephant are so easily tracked, their spoor standing out grey on the blackened earth. At this season, too, the bees’ nests contain honey and grubs. Hundreds of natives roam the bush and the honey-guides are at their busiest. Elephants were numerous, and for sixteen days I tracked them down and either saw or heard them stampede, warned of our presence by honey-guides, without the chance of a shot. Towards the end of this ghastly period my trackers were completely discouraged. They urged me to consult the medicine man, and I agreed to do so, thinking that at any rate my doing so would imbue the boys with fresh hope. Arrived at the village, in due course I visited the great man. His first remark was that he knew that I was coming to consult him, and that he also knew the reason of my visit. By this he thought to impress me, I suppose, but, of course, he had heard all about the honey-guides from my boys, although they stoutly denied it when I asked them after the interview was over. Yes, I said, I had come to see him about those infernal birds. And I told him he could have all the meat of the first elephant I killed if he could bring about that desirable end to my long hunt. He said he would fix it up. And so he did, and the very next day, too.

In the evening of the day upon which I had my consultation I was strolling about the village while my boys got food, prepared for another trip in the bush. Besides these preparations I noticed a lot of basket mending and sharpening of knives. One woman I questioned said she was coming with us on the morrow to get some elephant meat. I spoke to two or three others. They were all preparing to smoke and dry large quantities of meat, and they were all going with us. Great optimism prevailed everywhere. Even I began to feel that

the turning in the lane was in sight. Late that night one of my trackers came to say that the medicine man wished me to stay in camp in the morning and not to proceed as I had intended. I asked the reason of this and he simply said that the medicine man was finding elephant for me and that when the sun was about so high (9 o’clock) I should hear some news.

ELEPHANT SLINKING AWAY, WARNED OF THE APPROACH OF MAN BY HONEY-GUIDES

MEDICINE INDEED!

Soon after daybreak natives from the village began to arrive in camp. All seemed in great spirit, and everyone came with knives, hatchets, baskets and skin bags of food. They sat about in groups laughing and joking among themselves. Breakfast finished, the boys got everything ready for the march. What beat me was that everyone—my people included—seemed certain they were going somewhere. About 9.30 a native glistening with sweat arrived. He had seen elephant. How many? Three! Big ones? Yes! Hurriedly telling the chief to keep his people well in the rear, off we set at a terrific pace straight through the bush until our guide stopped by a tree. There he had left his companion watching the elephants. Two or three hundred yards further on we came to their tracks. Everywhere were the welcome signs of their having fed as they went. But, strangest thing of all, not a single honey-guide appeared. Off again as hard as we could go, the tracks running on ahead clear and distinct, light grey patches on a burnt ground with the little grey footmarks of the native ahead of us. In an hour or so we spotted him in a tree, and as we drew near we caught the grey glint of elephant. Still no honey-guides; blessings on the medicine man! Wind right, bush fairly open, it only remained to see if they were warrantable. That they were large bulls we already knew from their tracks. Leaving the boys, I was soon close behind the big sterns as they wandered gently along. In a few seconds I had seen their ivory sufficiently to know that one was really good and the other two quite shootable beasts. Now for the brain shot. Of all thrills in the world give me the standing

within 20 yds. of good elephant, waiting for a head to turn to send a tiny nickel bullet straight to the brain. From toenail to top of back they were all a good 11 ft. Stepping a few yards to the left and keeping parallel with them I saw that the way to bag the lot was to shoot the leader first, although he was not the biggest. Letting pass one or two chances at the middle and rearmost beasts, I finally got a bullet straight into the leader’s brain. The middle one turned towards the shot and the nearest turned away from it, so that they both presented chances at their brains: the former an easy broadside standing, the latter a behind the ear shot and running. So hard did this one come down on his tusks that one of them was loose in its socket and could be drawn straight out. Almost immediately one could hear a kind of rush coming through the bush. The chief and his people were arriving. There seemed to be hundreds of them. And the noise and rejoicings! I put guards on the medicine man’s beast. From first to last no honey-guide had appeared. The reader must judge for himself whether there was any magic in the affair or not. What I think happened was this: knowing that the medicine man was taking the affair in hand and that he had promised elephant, the natives believed that elephant would be killed Believing that, they were willing to look industriously for them in the bush. Great numbers of them scattered through the bush had the effect of splitting up and scattering the honey-guides, besides increasing the chances of finding elephant. The fact that we did not hear a single bird must have been mere chance, I think. But you could not convince an African of that. Natural causes and their effects have not a place in his mind. I remember once an elephant I had hit in the heart shook his head violently in his death throes. I was astounded to see one of his tusks fly out and land twelve paces away. The boys were awe-stricken when they saw what had happened. After ten minutes’ silence they started whispering to each other and then my gunbearer came to speak to me. He solemnly warned me with emotion in his voice never to go near another elephant. If I did it would certainly kill me after what had occurred. It was quite useless my pointing out that the discarded tusk was badly diseased, and that it would have probably fallen out in a short time anyhow. No! No! Bwana, it is medicine! said they

HE SHOOK HIS HEAD SO VIOLENTLY IN THE DEATH THROES THAT A TUSK FLEW OUT AND LANDED TWELVE PACES AWAY

A M’BONI VILLAGE.

Perhaps twenty grass shelters are dotted here and there under the trees.

Some few years ago I was hunting in the Wa Boni country in British East Africa. The Wa Boni form an offshoot of the Sanya tribe and are purely hunters, having no fixed abode and never undertaking cultivation of any kind. They will not even own stock of any sort, holding that such ownership leads to trouble in the form of—in the old days—raids, and now taxation. Living entirely on the products of the chase, honey, bush fruits and vegetables, they are perhaps the most independent people in the world. They are under no necessity to combine for purposes of defence, having nothing to defend. Owning no plantations, they are independent of droughts. The limitless bush provides everything they want. Skins for wearing apparel, meat for eating, fibres of great strength for making string and ropes for snares, sinew for bowstrings, strong and tough wood for bows, clay for pottery, grass for shelter, water-tubers for drinking when water is scarce, fruit foods of all sorts; and all these for the gathering. No wonder they are reluctant to give up their roving life. I was living in one of the M’Boni villages, if village it could be called. It consisted of, perhaps, twenty grass shelters dotted here and there under the trees. It was the season when honey is plentiful, and there was a great deal of