An Edwardian concert with England’s organ composer

An Edwardian concert with England’s organ composer

The Organ of St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh

(1863–1933)

Organ of St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh

1 Festival Prelude on ‘Ein’ feste Burg’

2 Fantasia

3 Scherzo symphonique concertant

4 Theme (Varied) in E flat

5 Barcarolle in B flat

6 Concert Overture in E flat

7 Mélodie in F Anton Rubinstein (1829–1894), arr. Faulkes

8 Fantasia on Old Welsh Airs

9 Légende and Finale

playing time

Tracks 2–9 are premiere recordings

Recorded on 28-29 May and 10-11

October 2014 in St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh by kind

permission of the Provost

Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing & mastering: Paul Baxter

Design: Drew Padrutt

Booklet editor: Henry Howard

Photography © Dr Raymond Parks

Photograph of Duncan Ferguson

© Susan Torkington

Delphian Records Ltd–Edinburgh–UK www.delphianrecords.co.uk

Amid all the dry and uninteresting hours that must be devoted to purely technical matters how refreshing it is both to teacher and pupil to rest for a moment upon one of the simpler little truly organistic compositions of William Faulkes; and when years of effort have been crowned by a smooth technical proficiency and the student has not yet lost his love of pure musical beauties how delightful it is to open a recital with Concert Overture in E flat by William Faulkes: between the two periods lies a wealth of practical organ music that is hardly excelled by any one composer.

Join the Delphian mailing list: www.delphianrecords.co.uk/join

Like us on Facebook: www.facebook.com/delphianrecords

Follow us on Twitter: @delphianrecords

Many organists today do not recognise the name William Faulkes, nor are they aware of the high regard that existed for his music during his lifetime, as demonstrated by this quotation from the July 1919 edition of The American Organist – the first time the journal had presented a biography of a non-American organist. While Faulkes’s name does appear in recent studies of organ music from the late Victorian and Edwardian period, mentioned alongside his contemporaries Lemare, Hollins, and Wolstenholme, today his name is unknown even in the church where he spent most of his career, St Margaret’s, Anfield. Comfortably England’s most prolific organ composer of all time – with over five hundred published organ works and several hundred more in manuscript – Faulkes was one of the leading figures in a generation of organists and organ composers whose style of composition went out of fashion, but has recently been undergoing something of a resurgence.

The organ music of the time is increasingly being accepted, if not necessarily as a forgotten contribution to the canon of musical masterworks, then at the very least as music that epitomised or even helped define the age in which it was created. It is melodious, spirited, uplifting music that speaks of a period of (apparent) great national confidence, and one moreover in which the organ concert had come to be enjoyed by the masses to an unprecedented extent. Organists of relatively insignificant churches became national and even international celebrities as virtuosos. The organ became an out-and-out orchestral instrument thanks to its place in the town and concert hall, and even the theatre and cinema, at a time when orchestras themselves rarely went on tour and orchestral performances were far less frequent than weekly or even daily organ recitals. That organs were planned for the liner Britannic (and possibly Titanic, built in Faulkes’s home town of Liverpool) is testimony to the great popularity of the instrument among all classes, and its seemingly unending possibilities for recreating the sounds of the full concert orchestra. Composers responded, with record amounts of new music being written, while organ builders produced the instruments to play it. The most inexhaustible composer of all was William Faulkes, who wrote for concert hall, church and even the home, for the beginner to the accomplished recitalist. As such he has some claim to being ‘England’s organ composer’, whose music, still almost entirely neglected, calls for reassessment.

George William Henry Faulkes was born in Liverpool on 4 November 1863. From 1882 to 1886 he was Organist at St John the Baptist, Tuebrook, before moving just half a mile along the road to become Organist and Choirmaster of St Margaret’s Church, Anfield, a position he retained until his death in January 1933. Both churches contained organs built by William Hill, arguably the leading English organ builder of the late nineteenth century. St Margaret’s was of considerable proportions, one of the most important brick churches erected during the era of the Gothic revival. The church burnt down in 1961, and with it the organ that Faulkes had played for much of his life was destroyed. Faulkes wrote a number of pieces for the choir at St Margaret’s, as well as his organ, orchestral and chamber music. His home in Priory Road, Liverpool was visited by Fulton B. Karr in the summer of 1911, who described Faulkes as being ‘a most interesting as well as a very lovable man … Tall, distinguished of appearance, and quite genial, he left me with a strong and lasting impression.’

There was no greater centre for organ concerts in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain than Faulkes’s home city of Liverpool. St George’s Hall was ‘a Mecca for music lovers’. The organist for the last decades of the nineteenth century was W.T. Best, described by Sir Henry Wood as ‘the world’s leading solo organist’. Best was the chief instigator in pushing the cause of the organ as orchestral concert

instrument, and largely responsible for the tradition of which Faulkes became so important a part. Afternoon concerts in St George’s Hall were chiefly for organ enthusiasts, while evening ones (priced at one penny) were for the general public, the Hall full to capacity. Best was notoriously discerning when it came to the music of contemporary composers, which makes his known endorsement of Faulkes’s music particularly significant. Faulkes seems to have had acted as a regular deputy at St George’s Hall, while his music featured frequently in the recitals of others. At a benefit concert on 4 July 1912, for instance, Edwin Lemare played a programme of Hollins, Dubois, Gounod, Mendelssohn and Faulkes, as well as several of his own arrangements of Wagner pieces. Being placed in the company of such composers was not a result of local loyalty or favouritism (although there was doubtless a degree of Liverpudlian pride in the city’s music making): a glance at recital programmes from the period across the country reveals countless performances of his music. Faulkes’s popularity was not restricted to England, with his music regularly forming part of Professor Samuel A. Baldwin’s series of recitals in the Great Hall of City College in New York. In the 1908-9 season, for instance – attended, we are told, by an aggregate of ‘not less than seventy thousand’ – four pieces by Faulkes were performed, the same number as by Reger. When German-American enterprise developed Welte Philharmonic organs (which enabled recording

rolls to be made by famous performers of the time), Faulkes was one of the organists asked to record for the company. Many of his works also featured in the recordings made by others, with his music seen as highly marketable both in England and America and his reputation already well established as a leading organ composer of the age on both sides of the Atlantic. Liverpool’s status as a port may well have done no harm in promoting the city’s music in New York and beyond.

No one piece of Faulkes’s colossal output more perfectly encapsulates the spirit of the concert hall than his Concert Overture in E flat. The concert overture had grown into a stand-alone genre of composition. It is typical of the period that a form of composition associated with orchestral performance became transferred to the organ. The piece is dedicated to Alfred Hollins, a contemporary of Faulkes, who told the story of how the piece came into being in his autobiography, A Blind Musician Looks Back:

William Faulkes was one of those I met then for the first time. Hardly thinking he would take the question seriously, I asked him whether he would write for me a concert overture with a part which would show off a fine Tuba. The result was his brilliant Concert Overture in E flat, dedicated to me.

Hollins goes on to tell an amusing anecdote about the first performance:

I played it for the first time one of my Sundays at the Albert Hall, and when I went to rehearse on the Saturday I took the copy in case there were any points I wanted to make sure of … When my wife and I got home, to my dismay it was missing. I felt glad it was a printed copy and not Faulkes’s manuscript (which he had also given me), but I was distressed by the loss. Fortunately, when we returned to the Hall on Sunday the missing copy was lying on the table in the console enclosure and on it was written: ‘Found outside the Albert Hall.’

The Concert Overture in E flat is Faulkes’s most-performed work today, probably because of its association with Hollins, and it is clear that the piece soon made an impact on organists and audiences alike. It features as a regular concert opener in programmes from the time, including 14 October 1908 at City College, New York in one of Baldwin’s recitals, whose programme notes describe it as ‘a brilliant concert piece well designed to display the resources of a large modern organ’. Much the same can be said of Scherzo symphonique concertant, a piece that is rather more pianistic in use of octaves and staccato and yet still firmly orchestral in character and which one commentator, Peter Hardwick, likens to the third movement, say, of a nineteenth-century British symphony.

Faulkes wrote many pieces based on religious themes such as carols and hymn-tunes, the shorter ones obviously intended for church use as organ voluntaries. Nevertheless, despite their subject matter, larger ‘sacred’

compositions were still composed with the concert hall in mind. The Festival Prelude on ‘Ein’ feste Burg’ is Faulkes’s most significant work based on a pre-existing melody. The Lutheran hymn (sung to the English words ‘A mighty fortress is our God’) was well known to church and concert audiences alike, and had served as musical theme to works by many composers over the centuries (most significantly Reger in his Op. 27). Faulkes’s setting is typical of his treatment of themes, be they pre-existing or original ones, with different sections allowing plenty of variation in texture and colour. The work is dedicated to his concert organist and composer colleague Edwin Lemare, another keen advocate of Faulkes’s music. Fulton B. Karr, referred to earlier concerning his visit to Faulkes’s home, commented that the house was adorned with photos of many famous organists, and the dedicatees of his pieces reads like a Who’s Who of early twentieth century organists.

Not least among them was the French organistcomposer Alexandre Guilmant, to whom the Fantasia is dedicated. Guilmant, who had played at the opening recital of the organ at Notre-Dame, Paris, was the first French concert organist to tour America, and gave a particularly large number of recitals in England. His influence on English organists as performer and composer was strong, and his use of Handelian themes gave rise to many similar interpretations from the English composers.

Faulkes’s offering, which was written just a few years before Guilmant’s death in 1911, the same year as the Fantasia was published, demonstrates an appreciation of the French style, with a dreamy beginning and end, interrupted by a quicker and more forthright middle section.

The barcarolle was a popular genre for composers of the period and Faulkes wrote several. The Barcarolle in B flat was first performed by Baldwin in New York on 25 November 1908, described in the programme notes as ‘a charming bit, in which the varied tone colors of the instrument are well brought out’. The Theme (Varied) in E flat is a short and rather undeveloped piece, yet offers a wide range of tonal contrast, while Légende and Finale is on a much grander scale. A melody in E flat minor from the solo orchestral oboe contrasts with major sections on the swell strings and flute solo, before the rousing finale on full organ.

The Fantasia on Old Welsh Airs uses a number of popular melodies (Of Noble Race was Shenkin, Jenny Jones, Men of Harlech, All Through the Night, and The Ash Grove), all of which would have been well known to an Edwardian audience. W.T. Best had previously written his own Fantasia on a Welsh March.

chamber, and even piano music for the organ (Anton Rubinstein’s Mélodie in F being a particularly famous example of the latter) as they were for original compositions. This was not without some controversy, with a number of ‘purists’ feeling that such arrangements detracted from the important business of adding to the canon of organ-specific repertory.

market for organ music making and listening at all levels. He had indeed belonged to and helped shape a golden age.

Organ recitals of the period were notable just as much for arrangements of orchestral,

Sir Walter Parratt, organist of St George’s Chapel and later Master of the Queen’s Music, considered transcriptions to be examples of a ‘misapplied skill’. Yet such arrangements were hugely popular and continued despite the growing number of concert overtures, suites, sonatas and so forth that composers were writing for the concert organ. By the time of Faulkes’s death in 1933, the organ concert remained highly important, with the recent development of the cinema organ further popularising the role of the organ in society. Yet change was not far away. The organ reform movement, which began in Germany particularly as a result of the studies of Albert Schweitzer, led to an interest in different organs, earlier music and performing styles. The works of Faulkes and his English contemporaries seemed a world away, and rather quickly drifted out of fashion. Meanwhile, tours by orchestras to the provinces became more common, reducing the need for the organ to be the orchestral concert instrument that had attracted the masses at the beginning of the century. Faulkes’s best music epitomises this tradition at its most popular and glorious, while his hundreds of works supplied a mass

The organ of St Mary’s Cathedral was built in 1879 by ‘Father’ Willis. Though built for cathedral rather than concert hall, and having had various rebuilds and modifications since Harrison & Harrison took care of the instrument from 1931, its characteristic warmth and depth of tone has been retained, and would have sounded familiar to William Faulkes and his contemporaries. There have been several sympathetic additions to the organ over the years (1931, 1959, 1979, and 1995 respectively), and in this recording I have made some use of these stops where it seemed to be of benefit to the music. Most of the registrations selected, however, could have been used by anyone performing this music on the St Mary’s organ at the beginning of the twentieth century. Unlike many smaller church organs of the period, St Mary’s was blessed with a strong Great 2’ (Faulkes’s most common registration instruction is ‘Great to Fifteenth’), and a well-balanced Great Mixture, both usefully adding brightness to a work such as the Scherzo symphonique concertant. The warm diapason sound at 8’ and 16’ is complemented by the reeds that add colour on the one hand (the swell 16’ oboe being the first of its kind anywhere) and power on the other, ideal for music of this period.

© 2014 Duncan Ferguson

Duncan Ferguson

Duncan Ferguson was appointed Organist and Master of the Music at St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh in April 2008 while still in his mid-twenties. He has responsibility for the musical life of St Mary’s, and in particular for recruiting, training, and directing the Cathedral Choir. Immediately prior to his appointment he was Assistant Organist at St Mary’s, playing the organ for the daily services, concerts, and broadcasts. As an undergraduate he held the organ scholarship at Magdalen College, Oxford, where special events included various live broadcasts, recordings, and accompanying the premiere of an oratorio written by Sir Paul McCartney. He gained a distinction for his Master of Studies degree, researching the role of music at St Margaret’s Church, Westminster during the Reformation. From 2003 to 2005 he was Organ Scholar of St Paul’s Cathedral, where duties included regular recitals,

accompanying and directing the Cathedral Choir, and playing the organ at diocesan and national services. He was also a Tutor at King’s College London.

Recent solo work has included recitals at St Davids Cathedral in Wales and at St Mary’s Metropolitan Cathedral, Edinburgh, workshops for the Royal College of Organists and the Royal Schools of Church Music, and various performances during the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.

Under Duncan, the choir of St Mary’s has made four highly acclaimed recordings with Delphian, of music by Taverner (DCD34023), Bruckner (DCD34071), Gabriel Jackson (DCD34106) and most recently Sheppard (DCD34123); of the first of these, The Times wrote: ‘Duncan Ferguson is plainly a wizard,’ while the latter three were all honoured with Gramophone’s prestigious ‘Editor’s Choice’ accolade.

Organ music on Delphian

The Usher Hall Organ Vol II

John Kitchen DCD34132

The Usher Hall’s monumental organ celebrated its 100th birthday in 2014. Delphian artist and Edinburgh City Organist John Kitchen has established a hugely popular series of concerts at the Hall, and draws on its repertoire to follow up his 2004 recording of the then newly restored instrument with a programme that further represents the vast variety of music that draws in the Edinburgh crowds. Opening with an evocative new work by Cecilia McDowall, the first part of the programme resounds with the theme of bells (including the instrument’s extraordinary carillon). Jeremy Cull’s compelling transcription of Hamish MacCunn’s The Land of the Mountain and the Flood displays all of Kitchen’s virtuosic aplomb, while the Dance Variations on ‘Rudolph the red-nosed reindeer’ are a much delighted-in annual request. A recital of this nature wouldn’t be complete without a major piece of Bach, here dispatched with appropriately Edwardian swagger.

John Kitchen, Duncan Ferguson, Timothy Byram-Wigfield, Michael Bonaventure et al

DCD34100 (4 CDs + book)

Open this full-colour, large-format book and step into a world of glorious architecture and fascinating history. Edinburgh’s churches and concert halls are home to a rich variety of pipe organs, and twenty-two of the most notable are surveyed here, with extensive information on both the instruments and their venues. Meanwhile twelve illustrious players – all with deep-rooted Edinburgh connections – demonstrate the instruments’ full range and versatility on four accompanying CDs. The full gamut of the repertoire is here, and Edinburgh’s organs have the voices to match. Isn’t it time to lift the veil from some of the closest-guarded treasures of one of the world’s great cities? Includes extensive instrument and venue photography, and detailed specifications for all 22 instruments.

‘a masterpiece of publishing’

— International Record Review, January 2011

The Organ in the Church of the Holy Rude, Stirling

John Kitchen DCD34064

Edinburgh’s city organist John Kitchen visits Scotland’s Mither Kirk and the country’s largest organ. Never before heard on disc, the 1939 Rushworth & Dreaper represents the zenith of British organ-building. Kitchen harnesses this king of instruments in a varied recital, revelling in its sheer magnificence. Includes works by Widor, Duruflé and Guilmant, Stanford, Parry and Elgar, and by twentieth-century Dutch composers

Feike Asma and Cor Kee.

‘On this stonking disc, wait till you hear Kitchen unleashed on Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance” March No 1’

— The Herald, May 2008

Alfred Hollins (1865–1942): Organ Works

Timothy Byram-Wigfield

The Organ of Caird Hall, Dundee DCD34044

Designed by the blind organist Alfred Hollins, the Caird Hall instrument is one of the finest recital organs in the UK – as ideal a vehicle for Hollins’ own music as Byram-Wigfield is an exponent of it. Hollins effortlessly combines keyboard pyrotechnics with a quasi-orchestral approach to sonority. These works bristle with vigour, their swaggering confidence leavened with ingenuity and wit.

‘It is impossible to praise the choice of instrument or the performances on this CD too highly … It is made more valuable by being sonically one of the best recordings of an organ I have heard for some time’

— International Record Review, March 2007

Adeste Fideles: Organ music for Christmas

Thomas Laing-Reilly

The Walker Organ of St Cuthbert’s Church, Edinburgh DCD34077

Situated in the shadow of Edinburgh Castle, St Cuthbert’s was the first parish church in Scotland to hold candlelit services on Christmas Eve. The two-thousand-strong congregation was regularly joined by people standing in the aisles! Today, the organ continues to combine its role of supporting the singing with solo performance of varied repertoire. Director of Music Thomas Laing-Reilly has at his hands an instrument seemingly able to speak any language. Its vast colour palette is demonstrated with striking clarity on this disc, in a range of repertory which crosses national borders with disarming ease.

‘Streaks of brilliance … an illuminating experience’

— The Herald, December 2006

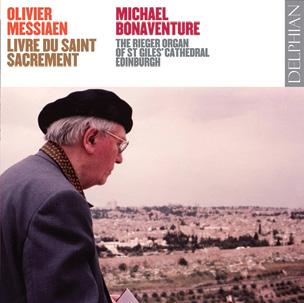

Olivier Messiaen: Organ Works Vol III

Michael Bonaventure

The Rieger Organ of St Giles’ Cathedral, Edinburgh DCD34076

The seeds for Messiaen’s final organ work were sown during an inspirational trip to Israel in 1984. Over the course of the following twelve months, the aging composer found improvisation leading him back to composition as he recovered from the exhausting labours that had produced his opera Saint François d’Assise. The Livre du Saint Sacrement became Messiaen’s grand farewell to his own instrument, and Michael Bonaventure performs it from memory here on the Rieger organ at St Giles’ Cathedral, whose true acoustic preserves the clarity of Messiaen’s lines.

‘uttery compelling’

— BBC Music Magazine, Proms 2008 edition, INSTRUMENTAL CHOICE