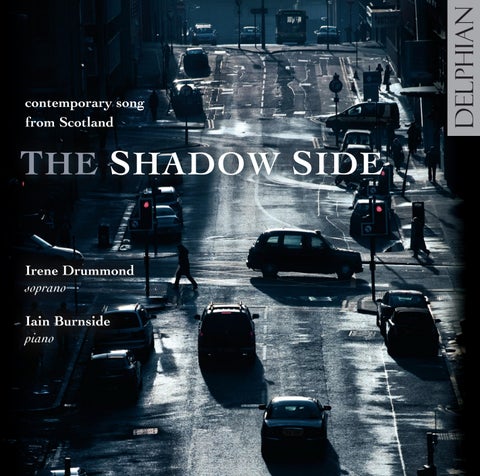

T HE S HADOW S IDE

Irene Drummond soprano

Iain Burnside piano contemporary song from Scotland

contemporary song from Scotland THE SHADOW SIDE

Irene Drummond soprano Iain Burnside piano

1 Three Soutar Settings: Ballad

James MacMillan (b1959)

The Web: Five Love Songs* Edward McGuire (b1948)

2 i. She trembled

3 ii. They sank deep into the yielding tissue

4 iii. He vaguely smiled

5 iv. And, thus they met

6 v. Love brushed by her

7 Three Soutar Settings: The Children

MacMillan

3 Poems of Irina Ratushinskaya*

John McLeod (b1934)

8 i. Where are you, my prince?

9 ii. I will travel through the land

10 iii. No, I’m not afraid

Two songs from Lasses, Love and Life*

arr. John Maxwell Geddes (b1941) 11 Aye Waukin, O!

Delphian Records gratefully acknowledges support from the following that helped make this recording possible:

Creative Scotland

Crear, Argyll

The Hope Scott Trust

The Finzi Trust

The RVW Trust

The Kenneth Leighton Trust

The Balmoral Hotel, Edinburgh

Judith Bingham (b1952) Two songs from Songs: Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect* Lewis Forbes (b1987)

15 The Watergaw [2:10]

16 John Anderson, my Jo [3:10]

Between Eternity and Time Paul Mealor (b1975)

17 i. Come Slowly, Eden [3:29] 18 ii. The Bequest [3:02] 19 iii. The Heart Asks Pleasure First [3:06]

20 A Red, Red Rose* [2:40] arr. Roderick Williams (b1965) Total playing time [69:04]

* denotes first recording

Recorded on 16, 17, 18 November 2010 at Crear, Argyll, Scotland.

Producer & Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing: Adam Binks

24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter

Design: Drew Padrutt

Booklet editor: Henry Howard

Piano: Steinway Model D Grand Piano, 1998, serial no 547113

Piano technician: Alasdair McLean

Photography: © Delphian Records 2011

Photograph editing: xxx xxx xxx

Cover photography: Kevin Smeekens

A great river of song flows from our shores. Since the eighteenth century tribute has been paid to the melodic vocal muse of Scotland, England and Wales. This CD is a timely snapshot from the most recent episode of this happy tale, celebrating Irene Drummond’s career-long commissioning and premièring of new songs. The recording does not just present new melodic angles on revered songs and poems but harnesses the creativity of living poets, too. The gift of hearing Irene’s voice in its wide-ranging expressiveness – from intimate emotional despair to expansive elation – makes a profound impact. I am convinced such a recording will contribute to bringing back the art of solo song to the forefront of British composers’ output.

The array of approaches taken by the composers is wide-ranging: from John Maxwell Geddes, who is closest to the folksong-collecting tradition of Cecil Sharp, through love songs of many hues, to songs from John McLeod and James MacMillan which present messages of profound moral and political significance.

Yet the essence of the ‘love song’ is never far from any of these works. The love song forms the backbone of our romantic traditions – and love can be both fulfilled and celebrated, unrequited or blighted (as in my own song cycle The Web). Indeed the love song is often emotionally ambivalent – sometimes revealing sinister forces at play. This dichotomy, this narrative power, is enhanced by the linking of single songs into cycles, reinforcing the emotional impact of the texts

and creating larger-scale rhapsodic, narrative and dramatic development. Among the songs we find influences ranging from the nineteenth-century use of folk elements as local colour, for example by Scandinavian and Bohemian composers; the ballad tradition; the legacy of the German lied; and French symbolism, as in the mélodie tradition of Fauré and Debussy. The use of Scots in some of the songs reveals a tailoring of melody and inflection to the language similar to that in Janácek and Bartók. Other songs follow the leap into absolute music that came through Schoenberg, Stravinsky and Bartók – a sound world echoed in McLeod’s, MacMillan’s and my own songs.

Key to the creative activity of the composers is their interaction with the poets – in some cases by giving an order to the poems to create the continuity of a song cycle. Coherence can also result from working with a single poet, a unifying topic, mood or other elements that integrate. Songs that are less strongly linked form ‘song collections’ or a ‘set’, where songs are more disparate and can stand as single entities.

Let us not forget the role of the piano on these journeys into the depths of heart and soul. In the hands of Iain Burnside – peerless in this repertoire – it triumphantly shoulders a multitude of tasks! A great range greets the ear: from a beautiful sparseness in the MacMillan songs, the sustained depth of the Paul Mealor cycle, the wit and wonder of Judith Bingham’s ‘mad song’, the emotionally charged,

dramatic outbursts of pianism in the McLeod cycle, the carefully detached counterpoint of Roderick Williams in A Red, Red Rose, to the poignant but charged piano sound I favoured for my own settings. The songs here also span a wide emotional spectrum. The sinister or ‘shadow side’ shows in McLeod’s cycle and in MacMillan’s ‘The Children’. But the compelling touch in this collection is that the violent side is leavened, enveloped with kindness and understanding. Healing is offered by beauty of voice, by resolutions within the compositions, and by the Scots song and old ballad traditions that return us to a more reassuring reality.

In the songs that use Scots, Irene creatively exploits its elements of attack, harder-edged consonants, articulation and pitching. She hones the Scots of Maxwell Geddes’ settings with a classical accuracy. The MacMillan songs employ grace notes with sometimes a slight pitch glissando moving to the main melody note, matching speech intonation. Lewis Forbes’ songs are from a major cycle subtitled (after Robert Burns) ‘Songs: Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect’. Irene thus spans the various genres, from the ancient ballad style, to classical lied, from the romance of the love song to modernism in its many guises – amply showing the power of the folk tradition to stand together with art song old and new. Irene brings them together in a selection which includes five major song cycles, two of which she commissioned and three premièred.

What of the songs themselves? There is a beautiful ordering on the CD – by coincidence almost chronological. The Three Soutar Settings by James MacMillan, interpolated throughout the recording as a recurring refrain, include the earliest of the selection: ‘Scots Song’, composed in 1984, a setting of William Soutar’s poem The Tryst. Speaking of this song, whose melody became a source of inspiration for several of the composer’s works in subsequent years, MacMillan recalled ‘This I sang in folk clubs with my old folk group Broadstone. The composing and performing of this song made a lasting impression on me. It felt as if I had tapped into a deep reservoir of shared tradition, as my setting was quite faithful to the old ballad style.’ Soutar himself created what he termed ‘synthetic Scots’: a blend, for poetic purposes, of Scottish dialects. The album opens with the more recent ‘Ballad’, from 1994. Its beautiful, poignant sparseness is fitting for Soutar’s theme, common in the old ballads, of the tragedy of a lover lost at sea. MacMillan’s hand is guided by his direct experience of the Scots ballad style. By contrast, his social consciousness and his moral and political awareness are brought to bear in his setting of ‘The Children’, a poem – part of his smaller output in standard English – that Soutar wrote during the Spanish Civil War of 1936 to 1939. The poet was aghast when he learned of the suffering in the conflict and this was his heartfelt response. In 1995 MacMillan in turn penned a deeply-felt creation: its poignancy – and sense of impending violence – grows, hangs there, and fades away. Yet symbols of destruction

are used in the poem rather than graphic imagery; likewise the melody notes may be few, but their impact gathers force. Their child-like ‘reflection’ is set against a threatening world portrayed in the piano part, as the song moves to its prophetic declaration ‘The blood of children corrupts the hearts of men’. MacMillan drew inspiration from this material for his acclaimed Inés de Castro for Scottish Opera in 1996: and from that period to the present his vocal settings have blossomed. Irene’s experience of singing in the premières of other MacMillan works, Songs of a Just War (with the New Music Group of Scotland), Catherine’s Lullabies (with the John Currie Singers) and Búsqueda (with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra at the 1992 Edinburgh International Festival) has given her deep insight into the heart of these three short songs.

When Irene commissioned me to write a song cycle for her and the group Ecossaise in 1989, I asked Lesley Siddall to write a set of poems suitable for singing. Born in central Scotland in 1953, Lesley is now working in Geneva where she continues to write poetry. Her five poems were a pleasure to set and we agreed on the resultant title The Web: Five Love Songs. A set of integrated poems without individual titles, they create a dramatic sequence – the essence of a song cycle. The emotional development was compelling, demanding music that subtly and surely wrought severe mood change. The whimsical thrill of love and passion as it first unfolds is the opening ‘play’; but as the songs roll out, doubts, intimate

anxiety and jealousy trap the woman in a ‘web’, with only the wisdom of hindsight providing a more optimistic resolution. Jonathon Brown in the Glasgow Herald summed up its atmosphere in 1990: ‘The words of the poems come like a catalogue of flimsy images and translucent melancholy, and the music is true to this wistful, slightly chilling sadness.’ The original score used flute, guitar, viola and percussion; so I returned to the original short score to produce the piano and voice version heard on this recording.

John McLeod’s 3 Poems of Irina Ratushinskaya also involved Irene in its formative stages. The John Currie Singers commissioned and premièred McLeod’s Songs from the Small Zone – settings of Ratushinskaya’s poems – in 1989, with Irene as soloist. The current song cycle uses two songs from the original work (‘I will travel through the land’ and ‘No, I’m not afraid’) and adds another (‘Where are you, my prince?’) to create a trio of settings that are an important marker for a period of immense historical change: the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Between 1983 and 1986 Ratushinskaya was incarcerated in a Soviet prison, experiencing illness and solitary confinement, but continuing to write poetry (including the second and third in this cycle). The imprisoned poet’s determination to survive in the face of injustice is given full force and life by McLeod’s music. McLeod’s piano accompaniment plays a powerful role, encapsulating the threats around her while also carrying the force of her willpower. Soaring over this is a sung line of tremendous

expressiveness. Often rising and falling in intervals that pack an emotional punch, the music has a continuity, through its family of themes and phrases, that leads us through her journey and eventually lifts us out of her pessimism. These songs are one of many highlights from a career that encompasses over 50 years of writing song cycles and other vocal music.

Glasgow-born John Maxwell Geddes is another composer with an enviable reputation for the orchestral craft. He does however return frequently to the music of his traditions. His 1990 setting A Burns Collection was for Irene and Ecossaise, and one of his early successes was Rune, written in 1973 for the John Currie Singers. Irene sings two of his settings of Scottish poets. Aye Waukin, O! is an old song to which Burns would appear to have made only minor changes. In this 1995 arrangement Geddes enhances the forlorn, sleepless lover’s plight with his characteristic harmonies. The words of The Laird o’ Cockpen are by Carolina Oliphant (Lady Nairne), a Perthshire-born poet and song collector who lived from 1766 to 1845. Her witty text satirises the Laird; a poor woman rejects the advances of this rich man, maintaining her integrity. Geddes sets the text to a traditional jig matching the wit with his chromatic, punchy and sometimes contrary-motion piano part. These two songs, Geddes points out, ‘provide two aspects of women in love’. They are from his cycle Lasses, Love and Life, inspired by the model of Robert Schumann’s Frauenliebe und -leben.

The Shadow Side of Joy Finzi was composed in 2001 to celebrate the centenary year of Gerald Finzi, renowned craftsman of the English art song. Judith Bingham chose extracts from four poems by Gerald’s widow, Joy; the melancholy and the Ophelia-like characteristics that permeate the texts drove her to set the words in a bleak landscape. Hence she felt an apt text to weave between the poems would be parts of the account of the ‘Little Ice Age’ of the seventeenth century in R.D. Blackmore’s Lorna Doone (1869). Another clue to the mood of this song cycle is the subtitle: ‘A Mad Song for Soprano and Piano’. This puts it firmly in the old tradition, as Judith says, of ‘a Purcell mad song with a continuous unfolding psychodrama’. Indeed the finale is marked to be like a Purcell recitative as it anxiously seeks the ultimate meaning of life, love and death. It was given its first performance that year by Irene and Iain, at the Ludlow Festival’s Weekend of English Song. Born in Nottingham in 1952, Judith Bingham is an award-winning composer whose orchestral music has been praised as ‘visionary’. With a style both imaginative and witty, she has composed much vocal music, as well as writing the texts for her own music theatre works.

The newest work – from 2009 – is also by the youngest composer on the CD, Lewis Forbes, who was born in Edinburgh in 1987. Currently studying for a Masters in Composition with Nigel Osborne at the University of Edinburgh, he has already had success with a song cycle, his Seven Songs winning the Tovey Memorial Prize; he

has also been commissioned by the St Magnus Festival. His interest in traditional music has been aroused through his work in the Balkans and on the Silk Road project. The Watergaw is a setting of Hugh MacDiarmid’s first lyric poem, published in 1922. MacDiarmid creates, as Forbes does in music, a personal and haunting experience, carried forward by the rhythm and strangeness of his use of Scots. As in the MacMillan settings, Forbes’ song fuses an older oral ballad style with modernist European innovations, creating a dense, symbolic unity of poetry and music. The title means a broken shaft of rainbow; the shadow of the death of MacDiarmid’s father may also hang over it. The text includes chilling imagery, as in ‘I thocht o’ the last wild look ye gied / Afore ye deed.’ To contrast this we have the romantic gesture of Forbes’ setting of the 1790 Burns poem John Anderson my Jo; in his newly composed melody more of the tenderness of the words is reflected, where ‘Jo’ really does carry its meaning of ‘sweetheart’.

Irene was so inspired by her experience of Copland’s early 1950s settings of Emily Dickinson’s poems that she commissioned Paul Mealor to set three more of his own choice. Between Eternity and Time was the outcome, dedicated to Irene and premièred with pianist Alasdair Beatson in 2008. Dickinson was just turning 30 when she wrote these three poems, between 1860 and 1862. By this time she was, as Thomas H. Johnson points out, ‘no longer a novice but an artist whose strikingly original talent was fully developed’. With their leaps of

imagination, they seem unbounded by time and space – yet are anchored in a touching intimacy. Her three favourite areas of thought are represented here in turn: the splendour of the earth, the pain of love, and the mystery of death. Mealor’s music illuminates the vision of an unpolluted paradise in ‘Come Slowly, Eden!’ He constructs a beautiful flow of melody in ‘Bequest’ and his music soars and floats high in ‘The Heart Asks Pleasure First’. Born in North Wales in 1975, he is currently Reader in Composition at the University of Aberdeen. His composition teachers have included Nicola LeFanu and Hans Abrahamson.

The Wigmore Hall, Purcell Room, Barbican Hall and live radio have all been graced by premières of music by Roderick Williams, while his fame as a baritone has spread worldwide. For the final song on this CD he has transported us back to the eighteenth century with his arrangement of A Red, Red Rose, one of the best-known of all love songs. Williams avoids its associated sentimentalism by setting it in an attractive, non-romantic frame, with his use of a flowing counterpoint in the piano accompaniment.

Edward McGuire

Edward McGuire won a British Composers Award in 2003 and the recording Eddie McGuire – Music for Flute, Guitar and Piano (Delphian DCD34029) was Editor’s Choice in the 2006 Awards Issue of Gramophone Magazine.

1 Three Soutar Settings: Ballad

James MacMillan

O! shairly ye hae seen my love

Doun whaur the waters wind: He walks like ane wha fears nae man And yet his e’en are kind.

O! shairly ye hae seen my love

At the turnin o’ the tide; For then he gethers in the nets Doun be the waterside.

O! lassie I hae seen your love

At the turnin o’ the tide; And he was wi’ the fisher-folk Doun be the waterside.

The fisher-folk were at their trade

No far frae Walnut Grove; They gether’d in their dreepin nets

And fund your ain true love.

William Soutar (1898-1943)

The Web: Five Love Songs

Edward McGuire

2 i.

She trembled –

Waiting for the words

That would lead her to Candle-light, moon-beams, Whispered caresses.

He trembled –

With the words on his lips

That would bring him

Soft breasts, warm skin, Sweet lips, bright eyes.

They trembled –And the words began, Spun by their voices Into the golden threads Of silken dreams

Which floated into the silence Till round them shimmered

The woven strands of A thousand bright tomorrows

And suddenly They were afraid To move or think Lest they shatter Their fragile prison.

3 ii.

They sank deep into the yielding tissue Of soft blind night, Pulling eternity round them Like a blanket.

Sight lay motionless behind their Velvet-lidded eyes

But in the darkness

The colours of his skin

Flashed, vivid, Through her fingers

And the carmine of her lips

Soaked, warm and pungent, Through his flesh.

They were caught on the filaments Of desire, Suspended between ‘Was’ and ‘will be’, And forever pressed Soft against his side As reality stirred beneath her hand.

4 iii.

He vaguely smiled, A few hours, no more, Then he’d be back, He said.

Vague smiles, With vaguer rendez-vous And Crouching, hidden, In her mind, The creature stirred

Scuttling unseen, Weaving tight Thick, corded webs That blocked the light And in that dark,

Chilled by her pain, Her love

Grew pale, But would not die

Though torn by despair Its roots ran deep And clung to a life

Washed colourless by grief.

And, soft as sin, From tissued lair, The beast came close To feed upon her heart.

A few hours, No more, Then he’d be back, He said.

5 iv. And, thus they met.

Wearing their loneliness Like a shroud, Damaged by the shattering Of their brightest dreams, They faced tomorrow like a foe

Till she reached out And pulled the shroud away And he turned back to brush The hard, sharp fragments From her heart.

Then peace fell gently

On the place

Where love had died, Softening the scars

Where passions,

Diamond-bright, Had ripped away; And past hurts, Oystered in their hearts, Washed free And fell away like stones.

Now as sweet contentment

Fills their days like honey, They sit in quiet company

And on the thread of memory

String each present pleasure

As it slips / Like a pearl / Between / The fingers / Of their minds.

6 v.

Love brushed by her, Sweeping her cheek with its wing And she knew it not.

Now, searching, she spins a golden thread That drifts on a wayward breeze And glints under an indifferent sun.

It has brought her many things –The brief, bright butterfly of romance, The soft dark moth of passion, Black, many-legged jealousy, Plump, carapaced companionship

And if love

Ever brushed her cheek

Again She’d know it now.

Lesley Siddall (b1953)

7 Three Soutar Settings: The Children

James MacMillan

Upon the street they lie

Beside the broken stone:

The blood of children stares from the broken stone.

Death came out of the sky

In the bright afternoon:

The darkness slanted over the bright afternoon.

Again the sky is clear

But upon the earth a stain: The earth is darkened with a darkening stain:

A wound which everywhere

Corrupts the hearts of men: The blood of children corrupts the heart of men.

Silence is in the air:

The stars move to their places: Silent and serene the stars move to their places.

William Soutar

But still she spins

3 Poems of Irina Ratushinskaya

John McLeod

To all imprisoned unjustly

8 i.

Where are you, my prince?

On what plank bed?

(No, I won’t cry: I promised, after all!)

My eyes are drier than a fire. This is only the beginning. How are you coping?

(Better than all the others. Oh, to take your hand!)

Winter’s draughty curtain

Drives the winds round in a circle

To the point of despair, The air was too exhausted

To leave its rags on the grille. Are you falling asleep?

It’s late.

I’ll dream of you tonight.

18 December 1981

9 ii.

I will travel through the land –

With my retinue of guards, I will study the eyes of human suffering, I will see what no one has seen –

But will I be able to describe it?

Will I cry how are we able to do this –Walk on partings as on water?

How we begin to look like our husbands –

Our eyes, foreheads, the corners of our mouths. How we remember them – down to each last vein of their skins –

They who have been wrenched away from us for years,

How we write to them: ‘Never mind, You and I are one and the same, Can’t be taken apart!’

And, forged in land, ‘Forever’ sounds in answer –

That most ancient of words

Behind which, without shadow, is the light.

I will trudge with the convoy, And I will remember everything –

By heart! – they won’t be able to take it from me! –

How we breathe –

Each breath outside the law!

What we live by –

Until the morrow.

12 November 1983

10 iii.

No, I’m not afraid: after a year

Of breathing these prison nights I will survive into the sadness

To name which is escape.

The cockerel will weep freedom for me

And here – knee-deep in mire –

My gardens shed their water

And the northern air blows in draughts.

And how am I to carry to an alien planet

What are almost tears, as though towards home…

It isn’t true, I am afraid, my darling!

But make it look as though you haven’t noticed. Irina Ratushinskaya (b1954) translated by David McDuff

11 Aye Waukin’, O! arr. John Maxwell Geddes

Aye waukin’ o! waukin’, ay, an’ wearie; Sleep I can get nane, for thinkin’ o’ my dearie.

Spring’s a pleasant time, floors o’ ilka colour; The birdie builds her nest, an’ I lang for my lover.

Aye waukin’ o! …

When I sleep I dream, when I wake, I’m eerie; Rest I can get nane for thinkin’ o’ my dearie.

Aye waukin’ o! …

Lanely nicht comes on, a’ the lave are sleepin’ I think on my lad an’ bleer my e’en wi’ greetin’.

Aye waukin’ o! …

Robert Burns (1759-1796)

12 The Laird o’ Cockpen arr. John Maxwell Geddes

The Laird o’ Cockpen, he’s proud an’ he’s great, His mind is ta’en up wi’ the things o’ the State; He wanted a wife, his braw hoose to keep, But favour wi’ wooin’ was fashious to seek.

Doon by the dyke-side a Leddy did dwell, At his tableheid he thocht she’d look swell, McCleish’s ae dochter o’ Claversha’ Lea, A penniless lass wi’ a lang pedigree.

His wig was well pouther’d and as guid as when new,

His waistcoat was white, his coat it was blue; He put on a ring, a sword, and cock’d hat, An’ wha could refuse the Laird wi’ a’ that?

He took the grey mare, he rade cannily, And rapp’d at the gate o’ Claversha’ Lea; ‘Gae tell Mistress Jean tae come speedily ben, She’s wanted tae speak wi’ the Laird o’ Cockpen.’

Mistress Jean she was makin’ the elderfloor wine;

‘An’ what brings the Laird at sic a like time?’ She aff wi’ her apron, and on her silk goon, Her mutch wi’ red ribbon, an’ gaed awa’ doon.

An’ when she cam’ ben, she bobbed fu’ low, An’ what was his errand he soon let her know; Amazed was the Laird when the Leddy said ‘Na,’ And wi’ a laigh curtsie she turned awa’.

Dumfoooner’d was he but nae sigh did he gie, He mounted his mare, he rade cannily, An’ aften he thocht, as he rade thro’ the glen, ‘She’s daft tae refuse the Laird o’ Cockpen.’ Carolina Oliphant, Lady Nairne (1766-1845)

13

Three Soutar Settings: Scots Song

James MacMillan

O luely, luely cam she in And luely she lay doun:

I kent her be her caller lips

And her breists sae sma’ and roun’.

A’ thru the nicht we spak nae word Nor sinder’d bane frae bane:

A’ thru the nicht I heard her hert Gang soundin’ wi’ my ain.

It was about the waukrife hour Whan cocks begin to craw: That she smool’d saftly thru the mirk Afore the day wud daw.

Sae luely, luely cam she in Sae luely was she gaen: And wi’ her a’ my simmer days Like they had never been.

William Soutar

14 The Shadow Side of Joy Finzi Poems by Joy Finzi set in a snowy landscape by R.D. Blackmore

Judith Bingham

Coronal

Sweet the lily, Sweet the rose, Sweet my love whom nobody knows.

Stay the cuckoo

Stay the moon

Away my love, the dial’s past noon.

Down to the river

So swift its flow

To show my love the way to go.

Bright the water

Dark the tide

Sharp the wound within my side.

But lo, in the night, such a storm of snow began as never have I heard nor read of. The wind was moaning sadly, and the sky as dark as wood. Song

There was a wound

It would not heal

It was both wide and deep

I sought to bind –It could not be

The waiting earth received the blood.

There was a cry

It would not cease

It echoed throughout sleep.

Where is the balm I sought to find? –

It was snowing harder than it had ever snowed before and the leaden depth of the sky came down. The snow drove in, a great white billow, rolling and curling beneath the violent blast, tufting and combing with rustling swirls. And all the while from the smothering sky came the pelting pitiless arrows, winged with murky white and pointed with barbs of frost.

from In That Place

A world without ending Into a vast similitude withdrawn

This Piercèd Side

O dear heart, Throughout this bright world Immense mystery, our searchings, The darkness and the light, and That end to which we go Imperishable…

Joy Finzi (1907-1991)

Prose extracts from Lorna Doone by R.D. Blackmore (1825-1900)

15 The Watergaw Lewis Forbes Ae weet forenicht i’ the yow trummle I saw yon antrin thing, A watergaw wi’ its chitterin licht Ayont the on-ding; an I thocht o’ the last wild look ye gied Afore ye deed!

There was nae reek i’ the laverock’s hoose That nicht – an nane i’ mine; But I hae thocht o’ that foolish licht Ever sin syne; an’ I think that mebbe at last I ken what your look meant then. Hugh MacDiarmid (1892-1978)

16 John Anderson, my Jo Lewis Forbes

John Anderson, my jo, John, When we were first acquent; Your locks were like the raven, Your bonnie brow was brent; But now your brow is beld, John, Your locks are like the snaw; But blessings on your frosty pow, John Anderson, my jo.

John Anderson, my jo, John, We clamb the hill thegither; And mony a cantie day, John, We’ve had wi’ ane anither: Now we maun totter down, John, And hand in hand we’ll go, And sleep thegither at the foot, John Anderson, my jo. Robert Burns

Between Eternity and Time

Paul Mealor

17 i. Come Slowly, Eden! Come slowly, Eden!

Lips unused to thee, Bashful, sip thy jasmines, As the fainting bee,

Reaching late his flower, Round her chamber hums, Counts his nectars – enters, And is lost in balms!

18 ii. Bequest

You left me, sweet, two legacies, –A legacy of love

A Heavenly Father would content, Had He the offer of;

You left me boundaries of pain Capacious as the sea, Between eternity and time, Your consciousness and me.

19 iii. The Heart Asks Pleasure First

The heart asks pleasure first And then, excuse from pain –And then, those little anodynes That deaden suffering;

And then, to go to sleep; And then, if it should be The will of its Inquisitor, The liberty to die.

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

20 A Red, Red Rose arr. Roderick Williams

O my Luve’s like a red, red rose That’s newly sprung in June; O my Luve’s like a melodie That’s sweetly play’d in tune.

As fair art thou, my bonnie lass, So deep in luve am I:

And I will luve thee still, my Dear, Till a’ the seas gang dry.

Till a’ the seas gang dry, my Dear, And the rocks melt wi’ the sun:

O, and I will luve thee still, my Dear, While the sands of life shall run.

And fare thee weel, my only Luve And fare thee weel, a while!

And I will come again, my Luve, Tho’ it were ten thousand mile.

Robert Burns

Irene Drummond

Soprano Irene Drummond, “one of Scotland’s most attractive exponents of the contemporary repertoire” (The Scotsman), has received considerable critical acclaim throughout her career for her interpretation of new music.

Many leading British composers have written works especially for her – Craig Armstrong, Sally Beamish, Judith Bingham, Lyell Cresswell, Helen Grime, John Hearne, David Horne, Edward McGuire, John McLeod, James MacMillan, Paul Mealor – and she is featured soprano on the CDs Amaterasu: The Music of John Kenny (British Music Label) and The Music of Paul Mealor (Campion Records).

Her varied and interesting career has taken her to many major venues and festivals throughout the UK, Europe and North America, performing mainstream repertoire alongside cutting-edge contemporary works with outstanding chamber musicians such as Martin Beaver, Ian Brown, Andrew Haveron and Maya Iwabuchi.

Since representing Scotland in the BBC Cardiff Singer of the World Competition, highlights of her career have included performances in the Waterfront Hall, Belfast, the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels, the Anhaltisches Theater, Dessau, St John’s Smith Square, London, the Los Angeles Music Center and La Scala, Milan, as well as the Aldeburgh, Edinburgh, Jerusalem, Northlands and Perth Festivals and the Dark Days Festival in Iceland and Speedside

Chamber Music Festival in Toronto. In Scotland she has performed with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, and the Hebrides, Paragon and Scottish Baroque Ensembles.

Broadcast performances have included Dvorák’s Te Deum with the BBCSSO conducted by Sir Alexander Gibson; David Horne’s cantata opera The Lie (commissioned by Radio 3); Handel’s Israel in Egypt for Israeli Television; Edward McGuire’s Loonscapes with the BBCSSO under Odaline de la Martinez; Clara Schumann lieder with American pianist Phillip Bush for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and many recitals for Radio Scotland and Radio 3.

Irene studied in Munich with the great German bass Hans Hotter, at the Britten-Pears School in Aldeburgh with Peter Pears and in London with Rae Woodland. She is also a highly respected singing teacher and voice coach with a busy teaching practice in Edinburgh.

[Sam Sills / Whitedog photography www. samsills.co.uk – positioning to be determined.]

Iain Burnside enjoys a unique reputation as pianist and broadcaster, forged through his commitment to the song repertoire and his collaborations with leading international singers. In recent seasons such artists have included sopranos Rebecca Evans, Galina Gorchakova, Lisa Milne and Ailish Tynan; mezzos Susan Bickley, Sarah Connolly and Ann Murray; tenors

John Mark Ainsley, Andrew Kennedy and Mark Padmore; and baritones Roderick Williams and Bryn Terfel. Through his strong association with the Rosenblatt Recital Series Iain has appeared with outstanding artists such as Lawrence Brownlee, Stephen Costello, Ailyn Perez, Matthew Rose and Ekaterina Siurina.

His recording portfolio reflects his passion for British music. For Signum he has recorded Herbert Hughes (Tynan), FG Scott (Milne/ Williams), Tippett (Ainsley), and Judith Weir (Tynan / Bickley / Kennedy). Naxos CDs include the complete songs of Gerald Finzi (Ainsley / Williams), together with Butterworth, Gurney, Ireland and Vaughan Williams. The NMC Songbook received a Gramophone Award. Other recent acclaimed releases include songs by Beethoven, Korngold and Liszt on Signum, and Richard Rodney Bennett on NMC (Sophie Daneman / Bickley / Williams).

Acclaimed as a programmer, Iain has devised a number of innovative recitals combining music and poetry which have been presented with huge success in Brussels and Barcelona with the collaboration of actors such as Simon

Russell Beale, Fiona Shaw and Harriet Walter.

At the Guildhall School of Music and Drama he holds the position of Research Associate, staging specially-conceived programmes with student singers and pianists. He has given masterclasses throughout Europe, at the Banff Centre, Canada, and at New York’s Juilliard School. Iain’s broadcasting career covers both radio and TV and he has been honoured with a Sony Radio Award.

Eddie McGuire: music for flute, guitar and piano

Nancy Ruffer, Abigail James, Dominic Saunders DCD34029

Over the past 40 years Eddie McGuire, British Composer Award winner and Creative Scotland Award winner, has developed a compositional style that is as eclectic as it is concentrated. This disc surveys a selection of his solo and chamber works, written for his home instruments – flute, guitar, and piano. The writing, whilst embracing tonality, focuses on texture and aspects of colour, drawing on a myriad folk influences. The listener cannot help being drawn in to McGuire’s evocative sound-world, at once bold and playful.

‘… this is quite simply beautiful music … Performances are excellent, the overall playing as expressive as the music itself requires; Delphian’s sound is spot-on … the perfect entrée to his sound-world’

Gramophone Editor’s Choice, Awards issue 2006

Scotland at Night: choral settings of Scottish poetry from Robert Burns to Alexander McCall Smith

Laudibus, Mike Brewer conductor DCD34060

Two collaborations between noted Edinburghians Alexander McCall Smith and Tom Cunningham appear on disc for the first time, in a programme of Scottish poetry set by some of today’s leading composers. From the ethereal tenderness of Cunningham’s ‘Lullaby’ to the muscular angularity of Ronald Stevenson’s A Medieval Scottish Triptych, Laudibus responds with affection and athleticism to the expert direction of UK choral doyen Mike Brewer.

‘… burnished performances ... The throbbing intensity of So Deep, a setting of “My Luve’s like a red, red rose”, and the mystical resonances in The Gallant Weaver are surely among the most treasured and most heartfelt of MacMillan’s works’

The Scotsman, May 2009