Barnaby Brown pipes & vocals

Clare Salaman fiddles & hurdy-gurdy

Bill Taylor lyres & harp

Barnaby Brown pipes & vocals

Clare Salaman fiddles & hurdy-gurdy

Bill Taylor lyres & harp

Barnaby Brown

Highland bagpipe (track 1)

Highland great pipe with Iain Dall chanter by Julian Goodacre

canntaireachd (tracks 3 & 8)

The Gaelic ‘vocabelising’ of bagpipe music, communicating details of fingering and expression vocally

vulture bone flute (track 5)

Vulture bone flute by Jean-Loup Ringot after a 30,000-year-old original found in Isturitz cave, southwest France; made from a Gyps fulvus ulna provided by the Centro de Recuperación de Fauna Silvestre de la Alfranca and Universidad di Valladolid

Bill Taylor

Highland clarsach (tracks 2 & 8)

26-string ‘Rose’ harp by Ardival Harps, strung in brass and silver

wire-strung lyre (track 3)

Lyre (anonymous) after 7th-c. fragments found at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, England; bridge by Simon Chadwick after a 4th-c. BC original found at High Pasture Cave, Skye, Scotland; strung in solid gold, silver, brass and iron

gut-strung lyre (track 6)

Gut-strung lyre by Guy Flockhart after early 8th-c. fragments found under the church of St Severin, Cologne, with bridge based on a mid8th-c. original found in a chieftain’s grave in Broa, Halla, Gotland, Sweden

Salaman

Hardanger fiddle (track 4)

Hardingfele by Gjermund G. Strommen

hurdy-gurdy (track 7)

Hurdy-gurdy with lute back by Chris Eaton

medieval fiddle (track 8)

Waisted vielle by Owen Morse-Brown, after 14th- and 15th-c. iconography

1 Hindorõdin hindodre: One of the Cragich (a ‘rocky’ pibroch) PS 53 [5:03] Ùrlar | A’ Chiad Siubhal S & D | Taoludh Gearr | Crunnludh Fosgailte | Ùrlar

2 Cumha Mhic Leòid (McLeod’s Lament) PS 135 [15:35] Ùrlar | A’ Chiad Siubhal S & D | Ùrlar | Barrludh S & D | Ùrlar

3 Fear Pìoba Meata (The Timid Piper) PS 103 [3:10] Ùrlar | Dùblachadh | Ùrlar

4 Cruinneachadh nan Sutharlanach (The Sutherlands’ Gathering) PS 72 [14:54] Ùrlar | A’ Chiad Siubhal S & D | Ùrlar | Taoludh S & D | Ùrlar

5 Hiorodotra cheredeche (a nameless pibroch) PS 126 [3:47] Ùrlar | A’ Chiad Siubhal S & D | Ùrlar

6 Port na Srian (The Horse’s Bridle Tune) PS 107 [11:19] Ùrlar | Ludh Sleamhuinn S & D | Taoludh Gearr Ùrlar | Crunnludh S & D | Ùrlar | Sruthludh

7 Pìobaireachd na Pàirce (The Park Pibroch) PS 21 [10:59] Ùrlar | A’ Chiad Siubhal | Taoludh S & D | Ùrlar

8 Ceann Drochaid’ Innse-bheiridh (The End of Inchberry Bridge) PS 165 [9:44]

Ùrlar S & D | A’ Chiad Siubhal 1–3 | Ùrlar | An Dara Siubhal 1–10 | Ùrlar

Total playing time [74:37]

All tracks arr. Barnaby Brown from Colin Campbell’s Instrumental Book 1797

This recording is a collaborative project funded by the AHRC research project Bass Culture in Scottish Musical Traditions (www.bassculture.info), European Music Archaeology Project (www.emaproject.eu), the University of Huddersfield (www.hud.ac.uk) and Delphian Records Ltd.

Recorded on 8-10 June 2015 in Phipps Hall, University of Huddersfield

Executive producer: Barnaby Brown

Producers: Barnaby Brown & Rupert Till Engineer: Rupert Till

Assistant engineers: Michael Baldwin, Tadej Droljc, Sebastien Lavoie

24-bit digital editing: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter

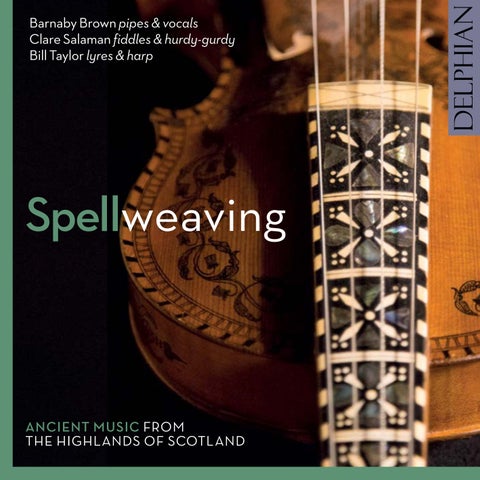

Cover image © Abigail Howkins

Design: John Christ

Booklet editor: John Fallas

Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.delphianrecords.co.uk

Join the Delphian mailing list: www.delphianrecords.co.uk/join

Like us on Facebook: www.facebook.com/delphianrecords

Follow us on Twitter: @delphianrecords

There are several remarkable things about the source of all the music on this disc, Colin Campbell’s Instrumental Book 1797. There is the sheer bulk of it – approximately 25 hours of music. There is its marriage of written and unwritten musical cultures, with only four of the 167 pieces found in earlier sources. There is its unique notation, developed from the syllables used by the MacCrimmons and Rankins to communicate and memorise the music. Above all, Campbell’s repertoire fills a void left by European instrumentalists who chose not to fix their art in musical notation. Perhaps they viewed it as a technology incapable of conveying essential evanescent or fluid subtleties. Or as an act of professional suicide, giving trade secrets away to competitors. Or as undermining a culture of apprenticeship, vital to keeping a venerated inheritance in safe hands. Whatever the reason, surviving notations of instrumental music represent only a fraction of past musical activity. The most exciting thing about Campbell’s book is that it begins to reveal how unrepresentative that fraction is.

A key impetus for this project was to break out of the piping ghetto, initiating a cultural exchange with the wider musical world. This was one of the motivations for using different instruments on each track. Another was the dilemma of what to play when very ancient instruments survive but not the artistry of their performers.

Campbell’s manuscript offers us heavyweight, serious repertoire that is rewarding for players and listeners. We were also driven by curiosity, wondering whether performance solutions on other instruments might help pipers to interpret this music more successfully. Just as Indian classical music is not confined to the sitar, or Bach to the organ, does Campbell’s manuscript provide a window on to a musical culture beyond the pìob mhòr or ‘great pipe’ of Highland culture?

If these experiments enliven debates on the evolution of pibroch, that is a bonus; our goal was to draw out of the shadows the instruments our ancestors loved, giving them a voice worth hearing in contemporary society.

Europe’s most illustrious instrument for over a millennium was the lyre. Six strings were fairly standard, so for track 6 we chose a pibroch with four pitches and tuned two strings in unison (C-D-D-E-G-A), creating a drone resonance like the ‘sister strings’ on a Highland clarsach. Although not required by the melody, the high A string served two expressive purposes: adding weight as an ornament, locally; and warming up the sound by degrees, globally. The return of the ùrlar (the slow theme) is informed by an observation made in 1760 by Joseph MacDonald: in pibrochs ‘which Contain a variety of runnings, they return to the Adagio once or twice. It is usual at the running before the Last to return to the Adagio, after which you proceed to the last which is that of greatest Execution.’

Samuel Johnson’s remark, in 1773, that pibroch goes back ‘beyond all time of memory’ is supported by a systemic confusion over the names of pieces. For example, The Horse’s Bridle Tune was also called ‘Blue Ribbon’ and ‘The Tune of Strife’; and McLeod’s Lament was called ‘Lament for the Tree of Hundreds’ and ‘Lament for the Harp Tree’. Thirty-one of Campbell’s pieces have no name at all, while eight have the enigmatic heading ‘One of the Cragich’. If this means they were creagach, or ‘craggy’, it is unclear whether this was a person, a place, a type of rowing song, or a musical quality. Nameless pibrochs are conventionally identified using the opening notes in Campbell’s notation: Hindorõdin hindodre conveys a precise fingering, just as dha kitatak dhum kitatak tells an Indian tabla player what to play. In 1815, Alexander Campbell described this as ‘the mode by which illiterate men communicate their musical ideas, (being entirely ignorant of notation), to one another’, and referred to ‘those sort of syllables by which Pipers fix in their memory the themes, & variations, of the various compositions performed on the Bag-pipe’. In tracks 3 and 8, I reconstruct this eighteenth-century canntaireachd with guidance on the one hand from field recordings of Hebridean traditionbearers, and on the other from Niel MacLeod of Gesto’s 1828 collection of ‘Pibereach or Pipe Tunes, as taught verbally by the McCrimmen Pipers in Skye to their Apprentices’.

With only nine notes in their musical universe, Highland pipers exercised extreme restraint, leaving plenty of room for surprise and contrast. Joseph MacDonald wrote:

One would think that the Small Compass of the Bag Pipe woud admitt of no Key but one & that same in a very Confind manner; but … it is hard to say if more cultivated Geniuses coud render the Composition of So Small a Compass more expressive.

Given that Europeans have been playing bird bones with three to five finger-holes for 42,000 years, the survival of sixteen virtuoso solos that use only four pitches and a hundred that use five should really come as no surprise. These exemplifications of musical mastery, like the bagpipe, retain some of the apparel of the Middle Ages if not of prehistory. The pitches are organised using structural frames: models that facilitated composition, aided memorisation and recall decades later, and heightened pleasure and delight by generating cultural expectations that allowed artists to tease the anticipation of aficionados. The pibroch frames are equivalent to poetic metres, and this recording presents three. One consists of a pair of question and answer phrases (QA) repeated, often with subtle variation, then developed in a way that creates contrast, excitement and culmination. Like all the conventional pibroch frames, it has four quarters: QA QA BC DE.

This structure permeates Western music and underlies every section of tracks 3, 4 and 5 here. Of outstanding beauty is the slight alteration in The Sutherlands’ Gathering, Ùrlar, 2nd quarter. After toying with three pitches for an entire minute, a fourth is introduced, releasing the built-up tension like a beam of light (see Figure 1). The process continues in the second half with three more pitches unveiled, slowly rising towards a triple climax. Few fifteen-minute solos in Western music have a more masterful shape. Campbell’s pieces regularly display a depth and sophistication lacking in eighteenth-century variation sets. Their calibre and nobility reflect pibroch’s social function – more about elevating the magnificence of a chieftain than pleasing a concert-going crowd.

The other two frames in this programme, unique to pibroch, weave geometrical patterns with a delight in interlace that is as Roman as it is Celtic. Tracks 1 and 8 use a symmetrical ‘woven’ frame (QQAQ AAQA) with equal and opposite halves; and tracks 2, 6 and 7 use an ‘ornate’ hybrid of the other two. The Gaelic term for frame was probably calpa. Other meanings for calpa include the walls of a house, the calf of a leg and the shrouds of a ship (the rigging), common to all of which is the idea of holding something up. Unlike the ùrlar, literally ‘floor’ (the theme that returns after each variation set), the calpa is the frame supporting every

section, often concealed in the ùrlar and more apparent once melodic elaboration has been stripped away. The calpa is defined by cycles of tension and release that flow at multiple rates (e.g. quarter-frame and whole frame), rather like waves on a beach. The siùbhlaichean (variation sets) provide a grander cycle of rising and falling drama, but not one paced like the tide. The majestic climaxes can build up over six minutes, whereas the falls take a matter of seconds.

Only in three places do we depart from Campbell’s 1797 score. In The Sutherlands’ Gathering , we draw on Peter Reid’s 1826 setting (Figure 1), interpreting the substantial differences as evidence of performer autonomy. This creative confidence faded after 1820 as individual renditions were canonised through the authority of printed books. In The Park Pibroch, we fill a gap in the calpa, supplying six bars so that the frame runs through intact, as is the case in tracks 2 and 6. In The End of Inchberry Bridge, we treat the calpa like a twelve-bar blues, using it as the basis for an improvisation. This starts at 6:16 in track 8 and is modelled on a bardic contest: Bill and Clare toss new variations back and forth, showing off what their instruments are capable of while pushing each other’s artistry to the limit. This departure from the score develops Campbell’s extraordinary ‘First Motion’ (see back of booklet), where the conventional four-beat phrases are stretched to five beats before, in

Figure 1. Peter Reid’s setting of The Sutherlands’ Gathering Manuscript produced in Glasgow, 1826; National Library of Scotland, ms 22108, f. 18r www.altpibroch.com/r

the last variation, a mischievous trick mystifies the listener: the Q phrase is reduced to two beats and the A phrase to three, producing the syncopated pattern 2232 3323. The bold tonal contrasts that had previously articulated the structure disappear and the intensity of a variation with only four pitches makes the return of the ùrlar all the more satisfying.

The rules we extrapolated for this improvisation sum up Campbell’s craft: use a frame to build

a larger structure; keep on climbing until you reach a natural peak, then relax with the ùrlar ; if you are tempted to take on a more exhilarating peak, then set off again. Pibroch is an extreme sport. The artist warms up carefully, preparing for a sprint to the summit; that ascent then serves as a warm-up for the next. This largerscale process subsumes the variations under a majestic skyline, testing performers to their physical limits and, if all goes well, giving listeners a taste of bliss.

Figure 2. Angus MacKay’s first setting of The Park Pibroch Manuscript produced in the 1830s; National Library of Scotland, ms 3753, p. 255 www.altpibroch.com/k1

In the Wardlaw Manuscript, compiled 1666–c.1700, we learn how one Highland magnate, Simon Fraser, Master of Lovat, had a wonderful fancy for music, variety of which he had still by him [during an illness in 1640], harp, virginels, base and trible viol in consort. He would say oft that music was an emblem of heaven, besids that it cheered a melancholy mind. Musica mentis medicine mœstis. The trumpet and great Pipe, both most Martiall, he would have a mornings, and vocall musick was his delight, of which he had enugh.

and, surrounded with the country people on all hands, were so hard put to it that Gileaspy Mackdonel, being wounded, gave way, and was defeat, being so hotly persued that most of his men were drowned in the River of Connin, and a considerable slaughter made upon them besids … This conflickt was called ever after Blare ni Pairk

The same manuscript provides an account of the battle commemorated in The Park Pibroch :

The Islanders camped about Contain, near Park, two miles above Braan, and, very numerous, being allarmed with the sight of the country people, got to their arms and made some formidable show …

[Glaisean Gobha ] got the front, et merite, a dareing fellow, instantly made the first breach with bowmen (having also the advantage of the ground) upon the enemy, which confused the Mackdonells, [who,] unacquainted with the country, were at a sad losse,

Although Angus MacKay’s score gives the date 1477 (see Figure 2), charters of the period suggest that Blàr na Pàirce took place in 1491. There is no trace of the pibroch before 1797, but the bewildering conflict between its notations points to a long period in oral transmission. The wider context makes it believable that an ancestor of Campbell’s score was composed in 1491. Payments to ‘una bagepipa pipanti’ are found in the English treasury accounts for 1285–6; ‘Maculin M’Callar murche, piper’ witnessed a property transfer for the Treasurer of Lismor in 1528; a bagpiper is depicted in the 1539 Carta Marina, playing for whalers butchering their catch on the Faroe Isles; and in 1581, Vincentio Galilei wrote:

This instrument is extremely popular with the Gaels; to its sound, these unconquered and fearsome warriors mount their campaigns and encourage one another to feats of valour in the midst of battle; with it, they also accompany their dead to the grave, making sounds so mournful as to invite, nay force the bystanders to weep.

After the defeat at Park, which is just south of Strathpeffer, it seems likely that a Clan Donald piper would have helped to assuage grief by composing a lament. We gave this aristocratic composition to an instrument that, like the pipes, enjoyed elite status in the late Middle Ages. The hurdy-gurdy was pushed to the lowest social classes in the seventeenth century for the same reasons that the bagpipe lost its honour in Germany in the fifteenth century and in Scotland in the eighteenth: a fixed drone was incompatible with the new fashion for a moving bass line. The soul of these instruments – their source of tonal variety for centuries, giving each note in the composer’s palette a different colour – became an impediment to changing key.

© 2016 Barnaby Brown

For further reading, source facsimiles, performing editions and documentation of the rehearsal process, visit www.altpibroch.com/spellweaving

Highland clarsach and great pipe (pìob mhòr ) with chanter copied from an original in lignum vitae played by ‘the Blind Piper of Gairloch’, Iain MhicAoidh, Am Pìobaire Dall (1656–1754)

Vulture bone flute after a 30,000-yearold original found in Isturitz cave, southwest France

Clare’s three fiddles: la vielle à roue (‘wheel fiddle’ or hurdy-gurdy), vielle (medieval fiddle) and hardingfele (Hardanger fiddle)

Lyre bridges in amber (after a mid-8th-c. original found at Broa, Halla, Gotland) and in yew (after a 4th-c. BC original found at High Pasture Cave, Skye)

Barnaby Brown abandoned the bagpipe when he was thirteen to pursue the orchestral flute. Ten years later he saw the light, returned to the classical music of the pipes and settled in seventeenthcentury Scotland. He was in the middle of studying Gaelic when an ancestor of the bagpipe took him back a thousand years and transplanted him to Sardinia. The guitarist Gianluca Dessì found him playing the triplepipe by a Bronze Age fort and was coaxing him back to the twenty-first century when some music archaeologists showed him how many prehistoric instruments were lying in silence.

Between 2006 and 2012, his artistic collaborations included smelting Japanese, Indian and Scottish traditions for the Edinburgh Festivals commission Yatra, composing ‘Scottish Bali’ with Gamelan Naga Mas, developing modules on several programmes at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, and helping design the European Music Archaeology Project. In 2014, his CD with the Choir of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge – In Praise of Saint Columba (Delphian DCD34137) – delighted critics in the Guardian, Times and Financial Times, and was described on BBC Radio 3’s Building a Library

as ‘doing for the music of the ancient Celtic church what Gothic Voices did for Hildegard of Bingen’. In 2015, Sir James MacMillan dedicated Noli Pater to him, a work for choir, organ and triplepipe commissioned by St Albans International Organ Festival. He is currently completing a PhD thesis at the University of Cambridge funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. His thesis has two counterparts – this CD and the website www.altpibroch.com. www.barnabybrown.info

Clare Salaman plays baroque violin, hurdy-gurdy, vielle, nyckelharpa, Hardanger fiddle and accordion. Her love for the sound of horsehair on gut, and her interest in strange and ancient instruments, was sparked by a holiday job cataloguing the musical instrument collection in the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford whilst reading music at Merton College. Two further years of study in baroque violin at the Royal College of Music led to a job in The English Concert and performances, broadcasts and CD recordings with all the leading period instrument ensembles in the UK, including The Dufay Collective and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment.

Working in many contexts outside early music, Clare has collaborated with musicians from Iran, Norway, France, India, Tanzania and Andalusia. She also enjoys teaching at the Royal College of Music and is an occasional presenter of BBC Radio 3’s ‘Early Music Show’. In 2010 she founded The Society of Strange and Ancient Instruments, which gives concerts and provides a forum for those fascinated by the sounds and sights of unusual musical instruments. This is now the main focus of her work.

www.claresalaman.com

Bill Taylor is a specialist in the performance of ancient harp music from Ireland, Scotland and Wales. He investigates these repertoires on medieval gut-strung harps, wirestrung clarsachs and Renaissance harps with buzzing bray pins. He plays in the ‘stopped style’ which used to be the main technique for all European harps. In this, fingernails strike the strings while fingerpads damp selectively, leaving some strings ringing. This contrasts with the modern technique of playing harps with fingerpads only.

For over twenty years, Bill has taught introductory and specialist courses for individuals and groups through Ardival Harps and Fèis Rois. He regularly gives classes and workshops for the Edinburgh International Harp Festival and teaches at the National Centre of Excellence in Traditional Music in Plockton and the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. He performs both as a soloist and with several ensembles, and has recorded over thirty CDs. In Scotland, he accompanies singer Anne Lewis in concerts of historical Scottish songs and airs, and he has worked extensively with early music specialist James Ross and storyteller Bob Pegg. On the Continent, he plays with Graindelavoix, Quadrivium and Sinfonye. Recently he joined the French ensemble Les Musiciens de Saint-Julien in a project recording and performing early Irish music.

www.billtaylor.eu

The European Music Archaeology Project (EMAP) is a five-year collaborative project funded by the EU Culture Programme. Aiming to explore our common European musical heritage by studying the music and sounds of the ancient past, the project involves the reconstruction of ancient instruments, musical performances and the creation of an exhibition. As a co-organising partner in the project, Dr Rupert Till and the University of Huddersfield are working with Delphian Records to create five CDs.

Spellweaving: ancient music from the Highlands of Scotland (EMAP Vol 1) will be followed in 2016 by two further discs – Ice & Longboats: ancient music of Scandinavia (EMAP Vol 2, with Ensemble Mare Balticum) and Dragon Voices: the ancient Celtic music of the Carnyx (EMAP Vol 3, performed by John Kenny) – and in 2017 by Cave Songs: Palaeolithic bone flutes from France and Germany (EMAP Vol 4) and by a fifth and final volume dedicated to ancient Greek and Roman instruments including the aulos, tibia, and water organ.

In Praise of Saint Columba: The Sound-world of the Celtic Church Barnaby Brown triplepipes & lyre, Simon O’Dwyer medieval Irish horn, Choir of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge / Geoffrey Webber DCD34137

Just as the influence of Irish monks extended not only across Scotland but also to mainland Europe, so we imagine our way back down the centuries into 7th-century hermits’ cells, 10th-century Celtic foundations in Switzerland, and the 14th-century world of Inchcolm Abbey, the ‘Iona of the East’ in the Firth of Forth. Silent footprints of musical activity –the evidence of early notation but also of stone carvings, manuscript illuminations, and documents of the early Church – have guided both vocal and instrumental approaches in the choir’s work with Barnaby Brown, an exciting extended collaboration which was further informed by oral traditions from as far afield as Sardinia and the Outer Hebrides.

‘performances of grace … musical conviction and beauty of tone’ — BBC Music Magazine, September 2014, CHORAL & SONG CHOICE

Chorus vel Organa: Music from the lost Palace of Westminster Magnus Williamson organ, Choir of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge / Geoffrey Webber DCD34158

The modern Houses of Parliament conceal a lost royal foundation: the chapel of St Stephen, begun by Edward I and raised into a college by his grandson Edward III. The foundation maintained an outstanding musical tradition for almost exactly two hundred years before the college was dissolved in 1548, when the chapel became the first permanent meeting place of the House of Commons under Edward VI. This recording brings together a repertoire of music that dates from the final years of the college under Henry VIII, and reconstructs both the wide range of singing practices in the great chapels and cathedrals and the hitherto largely unexplored place of organ music in the pre-Reformation period.

New in May 2016

Above. Musical notation for The End of Inchberry Bridge, A’ Chiad Siubhal 2–3 (track 8, starting at 2:25) Under CD tray. Musical notation for Fear Pìoba Meata (track 3)

From Colin Campbell’s Instrumental Book 1797, produced in Ardmaddy, Argyll

National Library of Scotland, ms 3715, p.176 & p. 50 www.altpibroch.com/c2