Missa desheritee

Missa Je suis déshéritée & Motets the Marian consort

emma Walshe soprano

Gwendolen Martin soprano

rory Mccleery countertenor/director ashley turnell tenor

nick Pritchard tenor rupert reid baritone christopher Borrett bass

1 Laudate Dominum EW, GM, RMcC, AT, CB [2:42]

2 Je suis déshéritée [?]Pierre Cadéac EW, RMcC, AT, CB [1:52]

3 Missa Je suis déshéritée – Kyrie EW, RMcC, AT, CB [2:09]

4 Omnes gentes attendite EW, GM, RMcC, AT, CB [4:37]

5 Missa Je suis déshéritée – Gloria EW, RMcC, AT, CB [4:01]

6 Victimae paschali laudes EW, GM, RMcC, AT, CB [7:59]

7 Missa Je suis déshéritée – Credo EW, RMcC, AT, CB [6:41]

8 Ascendo ad Patrem meum EW, GM, AT, NP, CB [4:17]

9 Missa Je suis déshéritée – Sanctus & Benedictus EW, RMcC, AT, CB [5:15]

10 Fratres mei elongaverunt EW, GM, RMcC, AT, NP, CB [4:16]

11 Missa Je suis déshéritée – Agnus Dei EW, GM, RMcC, AT, RR, CB [3:26]

12 Hodie Maria virgo EW, GM, RMcC, AT, NP, CB [3:58]

13 In pace EW, GM, RMcC, NP, RR, CB [5:38]

14 Assumpta est Maria EW, GM, RMcC, AT, NP, CB [4:24]

15 Gaudent in caelis EW, GM, RMcC, AT, NP, RR, CB [4:11]

16 In me transierunt EW, RMcC, AT, CB [4:44]

Total playing time [70:19]

Cover image: Lithograph after French school, 16th century, Catherine de’ Medici, private collection / Ken Welsh / The Bridgeman Art Library

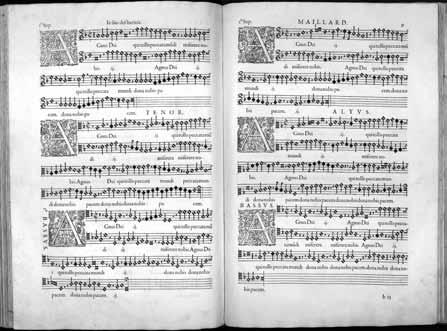

Image, left: Agnus Dei II of Missa Je suis déshéritée, from Missae Tres a Claudio de Sermisy, Ioanne Maillard, Claudio Goudimel, cum quatuor vocibus conditae , Paris: Adrian Le Roy and Robert Ballard, 1558 (Uppsala, Universitetsbibliothek)

Recorded on 7-9 January 2013 in the Chapel of Merton College, Oxford

Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing: Adam Binks

24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter

The Marian Consort photo © Eric Richmond

Design: John Christ

Booklet editor: Henry Howard

Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.delphianrecords.co.uk

With thanks to The Golsoncott Foundation, Professor Alexander McCall Smith, Christopher & Fiona Hodges, The Vernon Ellis Foundation, Frank Hitchman, Martin Swanzy, John & Mary Borrett, Professor Wendy Graham, Patrick & Sonia Bell, Roderick & Clare Newton and all the Friends of The Marian Consort for their generous support

With thanks also to Benjamin Nicholas, the Revd Dr Simon Jones and the Warden and Fellows of the House of Scholars of Merton College, Oxford

Despite being identified as ‘one of the most important French composers of the sixteenth century’ by the renowned musicologist François Lesure nearly half a century ago, Jean Maillard is a figure who remains shrouded in mystery and whose works have rarely been performed in modern times: the present recording is the first dedicated to his music. Much of the blame for this oversight can be attributed to Maillard’s meagre biography, itself a direct result of the paucity of surviving documentary evidence. He is mentioned by his contemporary Pierre de Ronsard as a ‘disciple’ of Josquin des Prez, among such illustrious fellow composers as Adrian Willaert, Clément Janequin, Jean Richafort, Jean Mouton and Jacques Arcadelt, in the French poet’s dedication to his 1560 Livre des Meslanges contenant six vingtz chansons. This collection was published by the Parisian firm of Adrian Le Roy and Robert Ballard, ‘Imprimeurs du Roi’, who were also responsible for three volumes of Maillard’s motets, as well as publishing numerous of his masses, chansons and other works in various anthologies: from this and Maillard’s other Parisian print appearances it can be surmised that he spent at least part of his life as a resident of the city. The only other direct mention of Maillard is in a rather less salubrious context, in a passage of Rabelais’s prologue to Book Four of Pantagruel, where

he again appears in the context of a list of composers, imagined by the author singing bawdy songs ‘in a private garden, under some fine shady trees’. Lesure has speculatively associated him with ‘two men named Jehan Maillart living in Paris in 1541’, but this is very much conjecture, and no concrete record of his musical training, employment history or death, the bedrock of biographies of other composers of this era, survives. From these references, however, coupled with the portrait of the composer as a middle-aged man found in the Modulorum Ioannis Maillardi issued in two volumes by Le Roy and Ballard in 1565 (the largest single collection of his sacred music), we can at least deduce that Maillard must have been born at some time in the first quarter of the sixteenth century.

Several scholars have suggested that the dedicatory preface to the second volume of the Modulorum, together with Maillard’s notable absence from Le Roy and Ballard’s new collections issued after 1571, point to the possibility that the composer harboured Protestant sympathies which may have resulted in his exclusion from the circles of the Catholic royal court, and possibly even his banishment from France. The preface is addressed to the Queen Mother, Catherine de’ Medici, and asks:

Faut il que ce gentil ouvrage

Endure les coups de l’orage

De notre Siecle malheureux?

Qui les graces les mieux polies

Chasse, ou recelle, enseuelies

Dessous un silence poudreux?

Non, non, vous les pouvez reprandre, Comme vostres, & nous les randre,

Et les tirer de tous dangers,

Car ce n’est q’une outrecuidance,

Qui les banist de vostre France,

Pour enrichir les estrangers.

These lines, which make clear reference to the Wars of Religion (‘ les coups de l’orage de notre Siecle malheureux’), can easily be construed as a personal plea for amnesty, with Maillard as one of the ‘graces les mieux polies‘ forced into hiding and exile. The composer’s settings of polemically-charged chansons spirituelles, including ‘Hélas mon Dieu, ton yre’ by the Huguenot poet Guillaume Guéroult and a paraphrase of Psalm 15 by Clément Marot, lend credence to this supposition. Raymond Rosenstock even goes as far as to posit that Maillard may, like his fellow composer Claude Goudimel, have been a victim of the 1572 St Bartholomew’s Day massacres, although there is no evidence to substantiate this theory.

Must this sweet work

Endure the stormy blows

Of our unhappy century,

Which chase away the most refined graces

Or conceal them, buried

Beneath a dusty silence?

No, no, you can reclaim them

As your own, and return them to us

And rescue them from all dangers,

For it is nothing but presumptuousness

That banishes them from your France

To enrich foreigners.

Such pronounced Protestant sympathies seem at odds, however, with the balance of Maillard’s compositional output, which consists largely of Latinate sacred works (eighty-six motets survive), many of which set Marian texts, and also with the particular connection that Maillard appears to have had with arguably the most Catholic of European countries at this time, Spain. The sole extant source for nearly two dozen of the composer’s motets is a Spanish manuscript (Barcelona, Biblioteca de la Disputació, MS 682), and his music is also preserved in the library of Tarazona Cathedral, as well as his In me transierunt appearing arranged as an instrumental work for vihuela and written out in tablature in Book II of El Parnasso, published in Córdoba in 1576.

What is clear is the popularity of Maillard’s music, and not only in Spain: his works were extremely widely disseminated, and survive in manuscripts and prints originating in Germany, France, Poland, the Czech Republic, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium and the UK. Telling also is the number of composers who modelled their own compositions on works by Maillard: this list includes fellow Frenchman Goudimel and also such luminaries as Orlande de Lassus, Jacob Handl and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. Emulation of this type was, as Howard Mayer Brown has observed, a conscious mark of respect, either out of a ‘sense of competition or in order to pay homage to an older master’.

Maillard himself was no stranger to parody composition (as this use of models is known), and no fewer than four of his six surviving masses are based on pre-existent polyphonic musical material: the one presented here takes as its basis the touching, but rather lachrymose miniature Je suis déshéritée. Almost certainly by Pierre Cadéac (in its earliest two surviving printed sources it is given as by ‘Lupus’, but later collections are unanimous in their ascription), this beautiful chanson is his most famous work and forms the basis of a whole group of parody compositions, including masses by Nicolas Gombert, Lassus, Palestrina, Jean Guyon and Nicolas de Marle, and chansons by Pierre Certon and Jacotin Le Bel.

The Missa Je suis déshéritée fits the model for deriving masses from a motet prescribed by the late sixteenth-century theorist Pietro Pontio, who states that

the beginning of its first Kyrie must be similar to the beginnings of the Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and first Agnus Dei Likewise the ends must follow the same theme and ordering as the end of the Kyrie.

Maillard stays particularly close to his exemplar, with relatively little freely-composed material, and the movements are concise, but with sparingly judicious use of particular effects, such as the homophony for ‘Tu solus Altissimus’ in the Gloria and ‘Jesum Christum’ in the Credo. In his setting of the final movements of the mass Maillard demonstrates further parody composition precepts, namely that the composer is at liberty to write ... the ‘Pleni sunt coeli’ and the Benedictus for fewer voices And to conclude their work with greater harmony and greater sonority, composers usually write the last Agnus Dei for more voices, adding one or two parts.

In this instance, Maillard doubles the highest and lowest voices, exploiting the antiphonal possibilities of a six-voice texture with twin Superius and Bassus parts.

indebted to the works of a previous generation of French composers. Although it is unlikely that Ronsard can be taken literally in his assignation of Josquin as Maillard’s teacher, it is obvious that the younger composer was familiar not only with the styles and techniques but also with specific works of his older compatriots: indeed, one of his motets includes an ostinato from Josquin’s chanson Faulte d ’argent.

Maillard’s setting of the Easter sequence Victimae paschali laudes, which includes some remarkable moments of textural and melodic word-painting, is very much in line with the compositional style of his contemporaries in terms of its employment of short melodic motifs in close imitation. However, Maillard uses the plainchant sequence as a source for the motet’s melodic material throughout its two parts, as well as occasionally quoting discrete sections of it in the manner of a cantus firmus, as can be heard at the very opening in the Primus Superius voice and at ‘Mors et vita duello’ in the Contratenor. In so doing, he recalls Josquin’s own four-voice setting of this text, which features plainchant paraphrase in its lower three voices.

the text. After this initial borrowing (and a nearcomplete statement of the first half of the chant in the Primus Superius), the rest of this setting of Psalm 117 appears to be freely composed, affording Maillard the opportunity to display his consummate artistry in creating a model of tightly-knit, finely wrought counterpoint.

Maillard’s motets also reveal traces of compositional borrowing, and are clearly

Maillard employs plainchant paraphrase in a number of his other motets, including the resolutely cheerful Laudate Dominum, for which the ascending triad which begins the fifth psalm tone fits perfectly with the sentiment of

Assumpta est Maria is one of a substantial number of Marian motets included in the second volume of the 1565 Modulorum Ioannis Maillardi, and the first of a pair of six-voice celebratory works for the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin which close the volume. Rosenstock has suggested that the number and placement of these Marian pieces were designed, alongside the inclusion of several motets with conspicuously ‘high’ clef combinations, to flatter the publication’s dedicatee by allusion. Maillard again draws on chant for his opening melodic figure, but seems to employ original material for the remainder of the work, including the initially homophonic figure for ‘habitare facit eam’ which allows for a moment of antiphonal exchange between twin Tenor and Superius parts. The second of these Assumptiontide motets, Hodie Maria virgo, begins with a joyful rising figure, which, coupled with the ‘major’-sounding transposed Ionian mode and the striking ascent of a ninth in the Contratenor at the conclusion of its first phrase, perfectly encapsulates the ebullience of the text. Maillard crafts his music to allow

for palpable text-expression: he withholds any real overall rise in Superius tessitura from the ascending figure for ‘caelos ascendit’ until the very final statement, before giving the Secundus Superius the highest note of the piece for her shout of jubilation on ‘gaudete’.

Maillard’s setting of the Compline responsory

In pace is striking in its similarity to that by his forebear Pierre Moulu. As with Moulu’s work, published in a collection by Parisian printer Pierre Attaingnant in 1535, Maillard composes polyphonic music only for the portions of the chant that would originally have been assigned to a soloist. The setting is therefore tripartite, with the emphasis on longer, more melismatic lines (the first section sets only two words) which help to evoke the soporific overtones of the text, with only the passage at ‘somnum oculis meis’ tending towards Maillard’s more customary text-oriented, short melodic phrases. Equally meditative at its opening is Omnes gentes attendite, the only known setting of this unusual text for the apocryphal feast of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It appears in a number of printed sources and manuscripts, including anonymously in one Scottish source, the ‘Wode Partbooks’, copied by Thomas Wode, vicar of St Andrews, under the patronage of James Stewart, Earl of Moray.

Of all of the motets selected for this recording, the affecting lament Fratres mei

elongaverunt is the one in which Maillard presents the most obvious display of musical heritage and pedigree in the form of the mensuration puzzle canon between its two Tenor parts. The following instruction is found in all three surviving sources: ‘Me oportet minui: Illum autem crescere’ (‘I must decrease: He must increase’, a reference to the Gospel of John). This rubric clarifies the nature of the canon, which requires two resolutions, one in augmentation and one in diminution, so that the second Tenor is realised in note values four times longer than the first, creating a slowmoving cantus firmus. What is particularly masterful is that as the responsory involves a repetition of ‘recesserunt a me’ (‘they have departed from me’), the motet closes with all parts singing the same text.

Ascendo ad Patrem meum, along with In me transierunt and Omnes gentes attendite, is one of Maillard’s most widely disseminated motets, and survives in more than a dozen geographically dispersed sources, including as a textless instrumental piece ascribed to the English composer ‘Dr Tie’ in Robert Dow’s Elizabethan manuscript partbooks. (This version of the piece is recorded by the Rose Consort of Viols on Delphian DCD34115.) This Ascensiontide work begins with the same exuberant triadic figure as Laudate dominum, and is punctuated by recurring Alleluias, each one of which is characterised by a different melodic motif.

As occurs in the other five-voice motets

Victimae paschali laudes and Omnes gentes attendite, the final Alleluia features a direct repeat of musical material, but with the Superius lines interchanged to provide variety. Maillard’s setting is possibly related to that by the later Slovenian composer Jacob Handl: although both works clearly paraphrase the chant associated with the text, there are a number of similarities which suggest that Handl was aware of Maillard’s piece when composing his own.

Only one of Maillard’s motets for four voices, In me transierunt, is presented here: this display of the composer’s meticulous craftsmanship enjoyed the widest circulation of any of his works. As well as being intabulated (as mentioned above), it also appeared as a didactic example in Gallus Dressler’s theoretical treatise, the Practica modorum explicatio of 1561. Like the Missa Je suis déshéritée, it draws its emotional power from subtle variations of texture, as is the case with the stillness of the opening homophony (an effect repeated at the beginning of the final section) and the near-homophonic passage at ’dolor meus’, where note-values are suddenly halved and the Superius tessitura raised. It is certainly no coincidence that the only other setting of this text is by Orlande de Lassus: Lassus enjoyed a special position as a personal friend of the publisher Adrian Le Roy, even staying in his house on a visit to Paris, and a great deal of

his music was issued by Le Roy and Ballard’s press. As such, he would undoubtedly have been familiar with the other composers whose works they published, especially someone who appeared in print as frequently as Maillard. This is confirmed by Gaudent in caelis, with Maillard’s majestic seven-voice motet thought to have been the basis for Lassus’s more modest four-part setting. Maillard’s setting of this text for the Common Commemoration of Saints displays his compositional ability through the combination of chant paraphrase and newly-composed material, aptly capturing both the celebratory mood of the opening and the various changes of emotional colour throughout the motet, most remarkably with the shift to the minor mode at ‘sanguinem suum’. The piece contains a minor textual variant, with the customary final line ‘exsultant sine fine’ replaced by ‘regnant in aeternum’, which Maillard sets to the lengthiest passage of music for a single textual phrase, evoking the eternity of the righteous by dint of repetition, before the various lines coalesce in the glow of the richly scored final chord.

© 2013 Rory McCleery

1 Laudate Dominum

Laudate Dominum, omnes gentes; laudate O praise the Lord, all nations: praise him, eum, omnes populi. Quoniam confirmata all people. For his mercy has been confirmed est super nos misericordia eius, et veritas upon us, and the truth of the Lord endures Domini manet in aeternum. for ever.

Psalm 117 (116)

2 Je suis déshéritée [?]Pierre Cadéac

Je suis déshéritée, I am deprived, Puisque j’ai perdu mon ami. since I lost my friend. Seule si m’a laissée, He has left me so alone, Pleine de pleurs et de souci. full of tears and worry.

Rossignol du bois joli, Nightingale from the beautiful woods, Sans faire demeure, without delay

Va t‘en dire à mon ami go and tell my friend

Que pour lui suis tourmentée. that I’m tormented for his sake.

3 Missa Je suis déshéritée – Kyrie

Kyrie eleison. Lord have mercy. Christe eleison. Christ have mercy. Kyrie eleison. Lord have mercy.

Omnes gentes attendite

Omnes gentes attendite ad tam pulchrum Pay heed, all people, to so a beautiful spectaculum, Deo gratias agite, qui sic dilexit spectacle, give thanks to God who so loved populum, Mariae formam sumite, quae his people, worship the form of Mary who virtutis est spectaculum. Alleluia. is a mirror of virtue. Alleluia.

5 Missa Je suis déshéritée – Gloria

Gloria in excelsis Deo Glory to God in the highest, et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis. and on earth peace to men of good will. Laudamus te. Benedicimus te. We praise you. We bless you.

Adoramus te. Glorificamus te. We worship you. We glorify you.

Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam We give you thanks for gloriam tuam. your great glory.

Domine Deus, Rex caelestis, Lord God, heavenly King, Deus Pater omnipotens. God the Father Almighty.

Domine Fili unigenite, Jesu Christe; Lord, the only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ; Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris. Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father, Qui tollis peccata mundi, who takes away the sins of the world, miserere nobis. have mercy upon us.

Qui tollis peccata mundi, Who takes away the sins of the world, suscipe deprecationem nostram. receive our prayer.

Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, Who sits at the right hand of the Father, miserere nobis. have mercy upon us.

Quoniam tu solus Sanctus, tu solus Dominus, For only you are Holy, only you are Lord, tu solus Altissimus, Jesu Christe. only you are Most High, Jesus Christ.

Cum Sancto Spiritu in gloria With the Holy Spirit in the glory of Dei Patris. Amen. God the Father. Amen.

6 Victimae paschali laudes

Victimae paschali laudes To the paschal victim let Christians Immolant Christiani. dedicate their songs of praise.

Agnus redemit oves: The Lamb has redeemed the sheep: Christus innocens Patri Christ who is without sin

Reconciliavit has reconciled sinners Peccatores. to the Father.

Mors et vita duello Death and life have duelled

Conflixere mirando: in a stupendous conflict; Dux vitae mortuus, The Prince of life was dead, Regnat vivus. but lives and reigns.

Dic nobis Maria, Tell us, Mary, Quid vidisti in via? what did you see on your way?

Sepulcrum Christi viventis, The tomb of Christ, who is alive, Et gloriam vidi resurgentis. and I saw the glory of his rising.

Secunda Pars

Angelicos testes, The angels standing as witnesses, Sudarium et vestes. the shroud and the garments.

Surrexit Christus spes mea: Christ my hope has risen: Praecedet vos in Galilaeam. He goes before you to Galilee.

Credendum est magis soli More trust should be placed

Mariae veraci, in truthful Mary alone quam Judaeorum than in the deceitful Turbae fallaci. crowd of Jews.

Scimus Christum surrexisse Truly, we know that Christ has risen A mortuis vere: from the dead: Tu nobis, victor victorious King, Rex, miserere. have mercy on us. Alleluia. Alleluia.

Sequence for Easter Sunday

7 Missa Je suis déshéritée – Credo

Credo in unum Deum, Patrem omnipotentem, factorem caeli et terrae, visibilium omnium et invisibilium. Et in unum Dominum Jesum Christum, filium Dei unigenitum, et ex Patre natum ante omnia saecula, Deum de Deo, lumen de lumine, Deum verum de Deo vero. Genitum non factum, consubstantialem Patri; per quem omnia facta sunt. Qui propter nos homines et propter nostram salutem descendit de caelis. Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto, ex Maria Virgine; et homo factus est. Crucifixus etiam pro nobis sub Pontio Pilato, passus et sepultus est. Et resurrexit tertia die secundum scripturas, et ascendit in caelum, sedet ad dexteram Patris, et iterum venturus est cum gloria iudicare vivos et mortuos, cuius regni non erit finis. Et in Spiritum Sanctum, Dominum et vivificantem, qui ex Patre Filioque procedit qui cum Patre et Filio simul adoratur et conglorificatur, qui locutus est per prophetas. Et unam sanctam catholicam et apostolicam

I believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all ages. God of God, light of light, true God of true God; begotten, not made; consubstantial with the Father, by whom all things were made. Who for us men, and for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man. He was crucified also for us, suffered under Pontius Pilate, and was buried. On the third day He rose again according to the Scriptures, and ascended into heaven. He sits at the right hand of the Father, and shall come again with glory to judge the living and the dead. And His Kingdom shall have no end. I believe in the Holy Ghost, Lord and giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son, who together with the Father and the Son is worshipped and glorified, who spoke through the prophets. I believe in one holy

ecclesiam. Confiteor unum baptisma in remissionem peccatorum, et expecto resurrectionem mortuorum, et vitam venturi saeculi. Amen.

8 Ascendo ad Patrem meum

catholic and apostolic Church. I confess one baptism for the remission of sins. And I await the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

Ascendo ad Patrem meum et Patrem vestrum, I am ascending to my Father and to your Father, alleluia, Deum meum et Deum vestrum, alleluia, to my God and your God, alleluia. alleluia. Nisi ego abiero, Paracletus non veniet: For if I do not go, the Paraclete will not come et dum assumptus fuero, mittam vobis eum. to you; and when I am taken up, I will send Alleluia. him to you. Alleluia.

Antiphon for the Benediction on Ascension Day (from John 20:17) with an addition used as a verse in the responsory ‘Tempus est’ for the same feast (from John 16:7)

9 Missa Je suis déshéritée – Sanctus & Benedictus

Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus. Holy, Holy, Holy, Dominus Deus Sabaoth: Lord God of Sabaoth. Pleni sunt caeli et terra gloria tua. Heaven and earth are full of your glory. Hosanna in excelsis. Hosanna in the highest. Benedictus qui venit Blessed is he that comes in nomine Domini: in the name of the Lord: Hosanna in excelsis. Hosanna in the highest.

10 Fratres mei elongaverunt

Fratres mei elongaverunt se a me, My brethren distanced themselves from me, et noti mei quasi alieni, recesserunt a me. and my acquaintances have departed from me

Dereliquerunt me proximi mei, like strangers. My friends have forsaken me, et qui me noverunt quasi alieni, and they that knew me have departed from recesserunt a me. me like strangers.

for Palm Sunday

11 Missa Je suis déshéritée – Agnus Dei

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, Lamb of God, who takes away the sins miserere nobis. of the world, have mercy upon us.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, Lamb of God, who takes away the sins miserere nobis. of the world, have mercy upon us.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, Lamb of God, who takes away the sins dona nobis pacem. of the world, grant us peace.

12 Hodie Maria virgo

Hodie Maria virgo caelos ascendit: gaudete, Today the Virgin Mary ascended into heaven; quia cum Christo regnat in aeternum. rejoice, for she reigns with Christ forever. Exaltata est sancta Dei genitrix, super choros The holy mother of God is exalted, above angelorum ad caelestia regna. the choirs of angels into the heavenly kingdom.

Antiphon for Second Vespers of the Assumption ‘Hodie …’ conflated with the versicle and response ‘Exaltata est …’

13 In pace

In pace, in idipsum dormiam et requiescam. In peace and into the same I shall sleep and rest. Si dedero somnum oculis meis, et palpebris If I give slumber to my eyes and to my eyelids meis dormitationem, dormiam et requiescam. drowsiness, I shall sleep and rest. Glory be to Gloria Patri, et Filio, et Spiritui Sancto. the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit.

14 Assumpta est Maria

Assumpta est Maria in caelum: gaudent angeli, Mary is taken up into heaven; the angels laudantes benedicunt Dominum. are rejoicing; praising they bless the Lord. Elegit eam Deus, et praeelegit eam Deus: God has chosen her, and He has set her apart. habitare facit eam in tabernaculo suo. He makes her to dwell in His tabernacle.

Antiphon at Second Vespers for the feast of the Assumption, coupled with the versicle and response for the third nocturn of Matins on Marian feasts

15 Gaudent in caelis

Gaudent in caelis animae sanctorum, The souls of the saints rejoice in heaven, qui Christi vestigia sunt secuti: et quia pro who have followed in the footsteps of Christ; eius amore sanguinem suum fuderunt, and because they shed their blood for love ideo cum Christo regnant in aeternum. of him, they reign with Christ forever.

Magnificat Antiphon for the Common Commemoration of Saints

16 In me transierunt

In me transierunt irae tuae, et terrores Your wrath swept over me, and your terrors tui conturbaverunt me, cor meum have destroyed me. My heart pounds, conturbatum est, dereliquit me virtus mea, my strength fails me, my pain is ever with me. dolor meus in conspectu meo semper: Do not forsake me, O Lord, my God, ne derelinquas me, Domine, Deus meus, be not far away from me. ne discesseris a me.

Taking its name from the Blessed Virgin Mary, a focus of religious devotion in the sacred music of all ages, The Marian Consort is a young, dynamic and internationally-renowned early music vocal ensemble, recognised for its freshness of approach and innovative presentation of a broad range of repertoire. Under its founder and director, Rory McCleery, this ‘astounding’ (The Herald ) ensemble has given concerts throughout the UK and Europe, has been featured on BBC Radio 3’s

The Early Music Show and In Tune, was a finalist in the 2009 York Early Music Festival International Young Artists’ Competition, and is a former ‘Young Artist’ of The Brighton Early Music Festival.

Known for its engaging performances and imaginative programming, the group draws its members from amongst the very best young singers on the early music scene today. They normally sing one to a part (dependent on the repertoire), with smaller vocal forces allowing clarity of texture and subtlety and flexibility of interpretation that illuminate the music for performer and audience alike. The Marian Consort is also committed to inspiring a love of singing in others, and has led participatory educational workshops for a wide range of ages and abilities.

particular focus on the exploration of lesserknown works, often bringing these to the attention of the wider public for the first time.

The Marian Consort is also a proud exponent of contemporary music, juxtaposing latter-day pieces and Renaissance works in concert in order to shed new light on both. As part of this commitment to new music, the group has commissioned several works from leading British choral composers.

The Marian Consort performs across the UK and Europe: recent highlights have included recitals at King’s Place, the Barcelona Early Music Festival and the Festival de Música Antiga Valencia; concerts for the Brighton Early Music Festival and the La Caixa concert series in Girona; and performances at the Wellcome Collection and the British Academy.

stars and the Sunday Times calling it ‘exquisite … the ensemble sings with eloquence and expressive finesse’.

Rory McCleery began his musical career as a chorister at St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh under Timothy Byram-Wigfield and Matthew Owens. He gained a double first in music at Oxford University as both Organ and Domus Academic scholar of St Peter’s College, subsequently completing an MSt in Musicology with Distinction in 2009.

the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow and the Concertgebouw in Bruges.

Its repertoire encompasses the music of the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries with a

The Marian Consort has released two CDs with Delphian Records: the first, of Marian Devotional music of the Spanish Renaissance (O Virgo Benedicta, DCD34086), invited praise from reviewers for its ‘fluent performances’ and ‘flawlessly executed programme’, and was singled out by Andrew McGregor on Radio 3’s CD Review for its ‘attractive and arresting sound’. The second, of English and Continental Renaissance music from the Dow Partbooks ( An Emerald in a Work of Gold , DCD34115), received outstanding reviews in all of the major broadsheets, with The Scotsman giving it five

In addition to directing and performing with The Marian Consort, Rory greatly enjoys working as a soloist and consort singer with specialist early music ensembles including The Monteverdi Choir, The Gabrieli Consort, Contrapunctus, The Dunedin Consort, The Tallis Scholars and The Cardinall’s Musick, under conductors including Sir John Eliot Gardiner, Paul McCreesh, John Butt, and Andrew Carwood.

Recent solo performances have included Bach Magnificat, St John and St Matthew Passions and Cantatas, Handel Messiah, Pärt Passio, Purcell Come ye Sons of Art, Ode to St Cecilia and Welcome to All the Pleasures, Monteverdi Vespers of 1610 , and Britten Abraham and Isaac in venues including the Wigmore Hall,

Rory has appeared as a soloist for broadcasts on Radio France, BBC Radio 3 and German and Italian radio, and collaborates regularly as a soloist with the Rose Consort of Viols. He studies singing with Giles Underwood. Rory is currently completing his doctoral research in the French Renaissance composer Jean Mouton at the University of Oxford, and is a freelance academic consultant for many of the ensembles with whom he performs. Rory is also a firm believer in the importance of vocal and music pedagogy, and is the assistant director of the Oxford Youth Choirs and an academic tutor at Oxford University.

O Virgo Benedicta:

Music of Marian Devotion from Spain’s Century of Gold

The Marian Consort, Rory McCleery director DCD34086

A six-strong Marian Consort makes its Delphian debut in a programme celebrating the rich compositional legacy of the Siglo del Oro’s intensely competitive musical culture. These luminous works – centred on the figure of the Virgin Mary – demand performances of great intelligence and vocal commitment, and the youthful singers respond absolutely, bringing hushed intimacy and bristling excitement to some of the most gorgeously searing lines in the history of European polyphony.

‘Precision of tuning and purity of tone … I gained a great deal of pleasure from listening to this flawlessly executed programme’

John Quinn, MusicWeb International, June 2011

Emerald in a Work of Gold: Music from the Dow Partbooks

The Marian Consort, Rose Consort of Viols

DCD34115

For their second Delphian recording, The Marian Consort have leafed through the beautifully calligraphed pages of the partbooks compiled in Oxford between 1581 and 1588 by the Elizabethan scholar Robert Dow. Sumptuous motets, melancholy consort songs and intricate, harmonically daring viol fantasies are seamlessly interwoven – all brought to life by seven voices and the robust plangency of the Rose Consort of Viols in the chapel of All Souls College, Oxford, where Dow himself was once a Fellow.

‘cleanly and calmly delivered … the concluding Ave Maria by Robert Parsons is superb, the final “Amen” attaining to genuine emotion but without the saccharine reverence that this much-recorded piece can attract’ Gramophone, February 2013

John Taverner: Sacred Choral Music

Choir of St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh / Duncan Ferguson

DCD34023

John Taverner brought the English florid style to its culmination; his music is quite unlike anything written by his continental contemporaries. In his debut recording with the critically acclaimed Edinburgh choir, Duncan Ferguson presents this music with forces akin to those of the sixteenth century – a small number of children and a larger number of men. The singers respond with an emotional authencity born of the daily round of liturgical performance.

‘Treble voices surf high on huge waves of polyphony in the extraordinary Missa Corona Spinea, while smaller items display the same freshness, purity and liturgical glow. Duncan Ferguson, the Master of Music, is plainly a wizard’ The Times, February 2010

William Turner (1651–1740): Sacred Choral Music

Choir of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge; Yorkshire Baroque Soloists

Geoffrey Webber conductor

DCD34028

It is easy to forget that our great English choral tradition was once silenced by act of Parliament. The restoration of the monarchy in 1660 subsequently ushered in one of the finest periods of English music, though the road to recovery for church music was a slow and difficult one. Turner, in 1660 a precocious nine-year-old, went on to become one of the best-known composers and singers of his day. This disc presents a crosssection of his sacred music, often in premiere recordings, ranging from small-scale liturgical works to one of his grandest creations, the Te Deum and Jubilate in D.

‘invigorating and highly persuasive … a reminder of the still unknown riches of English baroque music’

— Gramophone, October 2007