Christmas with the Shepherds

Mouton – Quaeramus cum pastoribus

Morales – Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus

Motets by Mouton, Morales & Stabile

1 Jean Mouton (before 1459–1522) Quaeramus cum pastoribus [5:41]

GM RMcC GC RR

2 Cristóbal de Morales (c.1500–1553) Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus – Kyrie [5:28]

EW RMcC AT RR CB

3 Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus – Gloria [6:30]

EW RMcC AT RR CB

4 Jean Mouton Puer natus est nobis [7:15]

GM RMcC GC RR

5 Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus – Credo [11:31]

EW RMcC AT RR CB

6 Jean Mouton Noe, noe, noe, psallite noe [4:41]

GM RMcC GC RR

Recorded on 13-15 January 2014 in the Chapel of Merton College, Oxford

Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing: Adam Binks

24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter

Cover image: after Raphael (1483–1520), school of, Adoration of the Shepherds, Scuola Nova series, tapestry (Brussels, 1624–1630), Vatican Museums/public domain Photography © Eric Richmond

Design: Drew Padrutt

Booklet editor: Henry Howard

Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.delphianrecords.co.uk

THE MARIAN CONSORT

Emma Walshe soprano

Gwendolen Martin soprano

Rory McCleery countertenor/director

Ashley Turnell tenor

Guy Cutting tenor

Rupert Reid bass

Christopher Borrett bass with Daniel Collins, David Gould countertenors (track 10)

7 Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus – Sanctus & Benedictus [5:52]

EW RMcC AT RR CB

8 Cristóbal de Morales Pastores dicite, quidnam vidistis? [4:02]

GM RMcC GC RR

9 Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus – Agnus Dei [6:26]

EW GM RMcC AT GC RR CB

10 Annibale Stabile (c.1535–1595) Quaeramus cum pastoribus* [5:22]

EW GM DG DC GC AT RR CB

Total playing time [62:55]

*premiere recording

All performing editions prepared by Rory McCleery

Join the Delphian mailing list: www.delphianrecords.co.uk/join

Like us on Facebook: www.facebook.com/delphianrecords

Follow us on Twitter: @delphianrecords

The Marian Consort would particularly like to thank the Golsoncott Foundation, the Vernon Ellis Foundation, the Nicholas Boas Charitable Trust, Chris and Fiona Hodges, Professor Alexander McCall Smith, John and Mary Borrett, Catherine Crowther, Jennifer Harding, Professor Wendy Graham, Jane Dodgson, Sir Roderick and Lady Clare Newton, Sebastian Brock, Patrick and Sonia Bell, Ben and Alex Reid, Dr Leofranc Holford-Strevens and Professor Bonnie Blackburn, Professors Alistair and Alison McCleery and Elizabeth Smyth for their generous support, without which this recording would not have been possible.

Ioannes Mouton Gallus, quem nos vidimus, quemadmodum antea in hoc adeo libro testati sumus, raritatem quandam habuit studio ac industria quaesitam, ut ab aliis, quos hactenus commemoravimus differret, alioqui facili fluentem filo cantum edebat.

Jean Mouton, the Frenchman, whom (as we witnessed earlier in this very book) we met, had a certain rare quality of zeal and industry, such as set him apart from the others whom we have recorded thus far, and in other respects he produced a music that flows in a supple line.

This assessment of the music and character of Jean Mouton by the Swiss music theorist Heinrich Glarean in his Dodecachordon treatise of 1547 has long coloured perceptions of a composer who, while considered worthy, has in more recent times been rather overshadowed by his contemporaries, most notably Josquin des Prez. Mouton’s biography, as far as can be construed from the documentation which survives, is, at least for his formative years, decidedly provincial: he is thought to have been born near Samer in the Pas-de-Calais, but the first record of him is as écolâtre-chantre (singer and teacher of religion) in the collegiate church of Notre Dame in Nesle in 1477, where by 1483 he had risen to the position of maître de chapelle and been ordained. Following a period as singer and music copyist at St Omer Cathedral, he became the maître des enfants at Amiens around the turn of the century, before in September 1501 moving to St André in Grenoble to take up the position of maître de

chapelle. This appointment was not to last long, as by the middle of the following year Mouton had left to become a member of the chapel of Queen Anne of Brittany. He would spend the remainder of his life in royal employment, first as maître de chapelle to Anne, on her death migrating to the chapel of her husband, Louis XII, and latterly that of Louis’s successor, François I.

Mouton’s historical significance as the teacher of the composer Adrian Willaert, who would become director of music of St Mark’s in Venice for thirty-five years, is relatively well established, as is his position as one of the earliest exponents and possible inceptors of the seminal sixteenth-century form of the ‘parody’ or imitatio (where a pre-existing polyphonic musical model provides the basis for a new composition, most notably a mass); but it is only now that the important didactic legacy of his largest body of work, nearly one hundred motets, is being acknowledged. Many of these pieces were widely and extensively disseminated in both print and manuscript form during the sixteenth century and beyond, often intabulated as instrumental transcriptions, and themselves formed the basis for imitatio masses and other compositions by later composers. Of these, none is more important for its lasting influence on several successive generations of composers than the four-part Christmas motet Quaeramus cum pastoribus. Mouton’s most widely travelled work, it survives in twenty-

seven manuscript and printed sources hailing from as far afield as Aberdeen and Guatemala, as well as in a number of Spanish, French and Italian intabulations, and almost certainly originated in the context of the Sistine Chapel in Rome and a tradition of Christmas ‘Noe’ or ‘Noel’ motets encouraged by the music-loving Medici Pope Leo X.

Thomas Schmidt-Beste has theorised that these papal chapel ‘Noe’ pieces formed a part of the repertoire of the motetto a pranza: music to be sung at the pope’s dinner on one of four occasions throughout the year, one of which was Christmas. According to several sources (including Glarean), Mouton was a particular favourite of the Francophile Leo, who awarded him the position of ‘apostolic notary’ following the meeting of the papal and French royal chapels in Bologna in 1515, and it is likely that Mouton wrote his motet Christus vincit in celebration of Leo’s election as pope in 1513. Many of Mouton’s motets are preserved in the music manuscripts of the Sistine Chapel and one such manuscript (Rome, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Cappella Sistina 46) may well be the earliest surviving source for Quaeramus cum pastoribus. That this piece remained in the performing repertoire of the Sistine Chapel for more than a hundred years, an astonishing fact, is evidenced by its recopying from this into another performance manuscript, Cappella Sistina 77, in the first quarter of the seventeenth century. Telling also is the

amendment made to the earlier source which is copied into the later manuscript: in the former, the repeated ‘noe’s have been re-texted in a later hand to the word ‘Alleluia’, possibly to conform with edicts of the Counter-Reformation and the Council of Trent concerning the removal of the secular from church music, and certainly to suit prevailing taste.

Mouton’s motet is a model of formal clarity, concision and melodic beauty, and after a conventionally imitative polyphonic opening sets a series of questioning textual dialogues with wonderfully-crafted antiphonal writing between pairs of voices, a hallmark of the composer’s compositional style. Each section of the motet is punctuated by the repeated ‘noe’ refrain, set always to the same melodic motif, but with each appearance subtly altered, an example of the spirit of inventiveness with which the whole motet is imbued. It is undoubtedly these qualities which made Quaeramus cum pastoribus such an attractive model for later composers: it was selected as the basis for imitatio mass settings by Willaert, Gasparo Alberti and Cristóbal de Morales, and imitatio motets by Thomas Crequillon (for six voices), Pedro de Cristo (for four voices), Giovanni Croce and Annibale Stabile (both for eight voices).

Among the other motets by Mouton in Cappella Sistina 46 are the four-part Noe, noe, noe, psallite noe and Puer natus est nobis,

which can be found grouped together with Quaeramus cum pastoribus on folios 28r–36v of the manuscript. Noe, noe, noe, psallite noe provides the model for at least one imitatio mass, by the composer Jacques Arcadelt, and was also published in intabulated versions by both Venetian and Parisian printers. It may well also have inspired the later setting of the same text by the German composer Gregor Aichinger. Unsurprisingly, given its title, it too falls into the tradition of the ‘Noe’ motet, with a joyous refrain punctuating each line of the text (the latter part of which is drawn from Psalm 24) and again serving to paragraph the musical material. Mouton sets much of the ‘Noe’ material as successive or overlapping pairs of duets, largely reserving the fuller fourpart texture for the interleaved lines of text, once more demonstrating his ability for writing beautifully-crafted, pithy polyphony.

Puer natus est nobis, one of two motets by Mouton with this title, forms part of a separate but related tradition, that of the ‘Christmas song motet’. As identified by Thomas SchmidtBeste and Jennifer Bloxam, this compositional form involves the combination of a number of different liturgical and non-liturgical texts, often with their associated melodies. Mouton chooses to combine a variety of seasonal liturgical texts, including portions of a respond and introit for Christmas day, with the nonliturgical ‘Magnum nomen Domini Emmanuel’, with both halves of the motet ending with the

same brief ‘noe, Alleluia’ coda, albeit heard twice at the conclusion of the second part. Again, the motet is predominantly formed of sequences of antiphonal exchanges between pairs of voices, with each textual phrase concluding with the coalescing of these pairs into a four-part texture for a decisive cadence. This formal design is clearly delineated in both the triple-time first part and the dupletime second part of the motet, with Mouton reproducing the rhythmic qualities, if not the exact pitches, of the ‘Verbum caro factum est’ motif of the former for the ‘per Mariam virginem’ text of the latter. The final phrase before the coda in the second half of the motet is also treated in triple-time, a common compositional device of Mouton and his peers, with this and the displaced homophony between the alto and the other three voices lending the music a distinctly exuberant, unpious quality.

Cristóbal de Morales, a Spaniard and native of Seville who spent a decade of his career between 1535 and 1545 as a singer in the papal chapel, selected motets by Jean Mouton as the basis for three of his seven surviving imitatio masses. His predilection for FrancoFlemish models is perhaps part of the reason, along with his absorption of their compositional style into his own, for his being classified by his fellow countryman Juan Bermudo as a ‘foreign’ composer in the theorist’s El libro llamado declaración de instrumentos musicales

of 1555. Surviving in two Italian prints from the early 1540s, one Roman and one Venetian, it is probable that Morales’ Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus was written for his colleagues in the Sistine Chapel who, like him, would have known and sung Mouton’s motet from MS Cappella Sistina 46. Morales chooses to add an additional bass voice to Mouton’s original four parts, allowing for new textural and sonic possibilities, and while clearly having the deepest respect for Mouton’s work, demonstrates his skill by cleverly reworking the motifs of the model throughout his mass. In so doing, he offers the listener an ingenious array of motivic possibilities and combinations in a wonderfully rich and varied texture which is necessarily, given the volume of text of much of the mass ordinary, on a rather grander scale than the original.

Morales’ compositional prowess is evident from the opening of the Kyrie, where Mouton’s initial figure is combined with the distinctive ‘noe’ refrain melody, and continues to show itself throughout the five movements, although always adhering to the precepts for imitatio composition codified by his younger contemporary Pietro Pontio in his Ragionamento di musica of 1588, which states among other principles that ‘the beginning of its first Kyrie must be similar to the beginnings of the Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and first Agnus Dei’. As is somewhat to be expected, versions of the ‘noe’ refrain serve to mark the imminent arrival of important cadence points and section ends, and Morales also introduces various themes as

ostinatos at points throughout the mass: notably in the reduced-voice ‘et ascendit’ of the Credo, where the soprano sings repeated statements of the ‘Ubi pascas’ melody which begins the second part of Mouton’s motet, and in the second of the three Agnus Deis, where the additional tenor voice, which appears only in this movement, has the opening motif as an ostinato at two different pitches. Striking also is the passage in the final section of the Credo where Morales introduces Mouton’s opening theme, again at two alternating pitches, in dialogue between tenor and basses, with five exact statements appearing in close succession. Morales introduces triple metre for the ‘Hosanna’s of the Sanctus and Benedictus, a device which would become common among his Spanish successors, and following pre-existing convention he reduces his forces to a trio of upper voices for the Benedictus. Again following established patterns, he increases the number of voices for the final Agnus Dei, with the additional soprano voice quoting Mouton’s own soprano line almost exactly until the ‘Dona nobis pacem’.

Morales’ Pastores dicite, quidnam vidistis?, while not directly related to any of Mouton’s Christmas motets, clearly draws its inspiration from them, and displays many of the compositional techniques characteristic of the older composer: after an initial four-voice, fully polyphonic opening, Morales reduces the texture to two pairs of duetting voices at ‘et annuntiate nobis Christi nativitatem’, which repeat the same musical material before

coming together for a final statement of this text. Both parts of the motet conclude with a section of ‘noe’ refrain, and the second part begins with the four voices in homophony to emphasise the importance of the sung text, another technique favoured by composers of Mouton’s generation.

More closely related to its model is Annibale Stabile’s double-choir setting of Quaeramus cum pastoribus, published by Friedrich Lindner in the 1588 Nuremberg collection Continuatio cantionum sacrarum … nuperrime concinnatarum, a print also containing motets by other Roman composers including Felice Anerio, Luca Marenzio and Rinaldo del Mel. Very little biographical information survives concerning Stabile, but what does remain suggests that he spent almost his entire career in Rome: he called himself a pupil of Palestrina, and may well have been a member of the choir of St John Lateran between 1555 and 1560 while the older composer was maestro di cappella. Stabile himself later held various maestro di cappella positions at churches in the city, including at St John Lateran from 1575 to 1578, the German College from 1578 to 1590 and latterly Santa Maria Maggiore from 1591 to 1594, before a fateful move to the employ of King Sigismund III of Poland in 1595: he died in Cracow in April of that year, only two months after taking up the post.

In his eight-voice Quaeramus cum pastoribus, Stabile unites the antiphonal aspect of Mouton’s motet with the polychoral style of late sixteenth-century Rome, emphasising the dialogue of the model through the passing of phrases between the two choirs, who only come together for moments of particular textual importance (‘verbum incarnatum’, ‘Jesum natum de virgine’ and ‘te rogamus, Rex Christe’) and in the final refrain. Stabile’s treatment of the ‘noe’s mirrors Mouton’s, with each successive iteration recognisably similar to the last through the use of the model’s rhythmically distinct ‘noe’ motif, but always differently treated. Stabile also makes use of reworked versions of many of Mouton’s other melodic motifs, particularly for the inquisitive exchanges at the heart of the motet, but just as often invents his own in the same spirit as the original, as at ‘cantemus’, where his rolling melismatic quavers in the first and then second choirs replace Mouton’s soprano melisma in describing the exultant singing of mankind at the news of the birth of the infant Christ.

1/10 Quaeramus cum pastoribus

Quaeramus cum pastoribus verbum incarnatum; cantemus cum hominibus regi saeculorum, noe.

Quem tu vides in stabulo?

Jesum natum de virgine. Quid audis in praesepio?

Angelos cum carmine et pastores dicentes: noe.

Ubi pascas, ubi cubes?

Dic, si ploras, aut si rides: te rogamus, Rex Christe, noe.

Cibus est lac virgineum, lectus durum praesepium, carmina sunt lacrimae, noe.

Let us search with the shepherds for the word made flesh; let us sing with men to the king of all ages, noel.

Whom do you see in the stable? Jesus, born of a virgin. What do you hear in the crib? Angels with their song and shepherds saying ‘noel’.

Where do you eat, where is your bed? Say, if you are crying or if you are smiling: we ask you, King Christ, noel.

My food is a virgin’s milk, my bed a hard crib, my songs are tears, noel.

2

Kyrie eleison.

Christe eleison. Kyrie eleison.

Lord have mercy.

Christ have mercy. Lord have mercy.

© 2014 Rory McCleery

Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus – Kyrie

3

Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus – Gloria

Gloria in excelsis Deo et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis.

Laudamus te. Benedicimus te.

Adoramus te. Glorificamus te.

Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam.

Domine Deus, Rex caelestis, Deus Pater omnipotens.

Domine Fili unigenite, Jesu Christe; Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris. Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostram.

Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis.

Quoniam tu solus Sanctus, tu solus Dominus, tu solus Altissimus, Jesu Christe.

Cum Sancto Spiritu in gloria Dei Patris. Amen.

4 Puer natus est nobis

Puer natus est nobis et filius datus est nobis.

Gloria in excelsis Deo et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis. Verbum caro factum est et habitavit in nobis, Alleluia, noe, noe. Angelus ad pastores ait: annuntio vobis gaudium magnum, hodie natus est Salvator mundi, Alleluia. Magnum nomen Domini Emmanuel, quod annuntiatum est per Gabriel, hodie apparuit in Israel per Mariam virginem et per Joseph, noe, noe, Alleluia.

Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men of good will.

We praise you. We bless you.

We worship you. We glorify you. We give you thanks for your great glory.

Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father Almighty.

Lord, the only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ; Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father: Who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us. Who takes away the sins of the world, receive our prayer. Who sits at the right hand of the Father, have mercy upon us.

For only you are Holy, only you are Lord, only you are Most High, Jesus Christ. With the Holy Spirit in the glory of God the Father. Amen.

A boy is born to us and a son given to us. Glory to God in the highest and on earth peace to men of good will. The word is made flesh and has dwelt among us, Alleluia, noel, noel. The angel said to the shepherds: I bring you news of great joy, this day is born the Saviour of the world, Alleluia. The great name of the Lord, Emmanuel, which was proclaimed through Gabriel, has appeared today in Israel, through Mary the virgin and through Joseph, noel, noel, Alleluia.

Credo in unum Deum, Patrem omnipotentem, factorem caeli et terrae, visibilium omnium et invisibilium. Et in unum Dominum Jesum Christum, filium Dei unigenitum, et ex Patre natum ante omnia saecula, Deum de Deo, lumen de lumine, Deum verum de Deo vero. Genitum non factum, consubstantialem Patri; per quem omnia facta sunt. Qui propter nos homines et propter nostram salutem descendit de caelis. Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto, ex Maria Virgine; et homo factus est. Crucifixus etiam pro nobis sub Pontio Pilato, passus et sepultus est. Et resurrexit tertia die secundum scripturas, et ascendit in caelum, sedet ad dexteram Patris, et iterum venturus est cum gloria iudicare vivos et mortuos, cuius regni non erit finis. Et in Spiritum Sanctum, Dominum et vivificantem, qui ex Patre Filioque procedit, qui cum Patre et Filio simul adoratur et conglorificatur, qui locutus est per prophetas. Et unam sanctam catholicam et apostolicam ecclesiam. Confiteor unum baptisma in remissionem peccatorum, et expecto resurrectionem mortuorum, et vitam venturi saeculi. Amen.

I believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all ages. God of God, light of light, true God of true God; begotten, not made; consubstantial with the Father, by whom all things were made. Who for us men, and for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man. He was crucified also for us, suffered under Pontius Pilate, and was buried. On the third day he rose again according to the Scriptures, and ascended into heaven. He sits at the right hand of the Father, and shall come again with glory to judge the living and the dead. And his Kingdom shall have no end. I believe in the Holy Ghost, Lord and giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son, who together with the Father and the Son is worshipped and glorified, who spoke through the prophets. I believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church. I confess one baptism for the remission of sins. And I await the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

5 Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus – Credo

6

Noe, noe, noe, psallite noe

Noe, noe, noe, psallite noe. Jerusalem, gaude et laetare, quia hodie natus est Salvator mundi. Noe, noe, noe, iacet in praesepio, fulget in caelo. Noe, noe, noe, attollite portas, principes, vestras, et elevamini, portae aeternales, et introibit Rex gloriae. Noe, noe, noe, quis est iste Rex gloriae? Dominus virtutum, ipse est Rex gloriae. Noe, noe, noe.

Noel, noel noel, sing noel. Jerusalem rejoice and be glad, for this day is born the Saviour of the world. Noel, noel noel, he lies in the crib, he shines in heaven. Noel, noel, noel, raise your gates, you princes, and be lifted up, you everlasting gates, and the King of glory will enter. Noel, noel, noel, who is he, this King of glory? The Lord of might and strength, he is the King of glory. Noel, noel, noel.

8 Pastores dicite, quidnam vidistis?

Pastores, dicite, quidnam vidistis? Et annuniate nobis Christi nativitatem, noe, noe. Infantem vidimus pannis involutum, et choros angelorum laudantes Salvatorem, noe, noe.

Shepherds, say, what have you seen? And tell us of the nativity of Christ, noel, noel. We saw the infant wrapped in swaddlingclothes, and choirs of angels praising the Saviour, noel, noel.

Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus.

Dominus Deus Sabaoth: Pleni sunt caeli et terra gloria tua. Hosanna in excelsis.

Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini: Hosanna in excelsis.

Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Sabaoth. Heaven and earth are full of your glory. Hosanna in the highest. Blessed is he that comes in the name of the Lord: Hosanna in the highest.

9 Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus – Agnus Dei

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona nobis pacem.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us. Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us. Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, grant us peace.

7 Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus – Sanctus & Benedictus

Taking its name from the Blessed Virgin Mary, a focus of religious devotion in the sacred music of all ages, The Marian Consort is a young, dynamic and internationally-renowned early music vocal ensemble, recognised for its freshness of approach and innovative presentation of a broad range of repertoire. Under its founder and director, Rory McCleery, this ‘astounding’ (The Herald ) ensemble has given concerts throughout the UK and Europe, features regularly on BBC Radio 3, and is a former ‘Young Artist’ of the Brighton Early Music Festival.

Known for its engaging performances and imaginative programming, the group draws its members from amongst the very best young singers on the early music scene today. They normally sing one to a part (dependent on the repertoire), with smaller vocal forces allowing clarity of texture and subtlety and flexibility of interpretation that illuminate the music for performer and audience alike. The Marian Consort is also committed to inspiring a love of singing in others, and has led participatory educational workshops for a wide range of ages and abilities.

The Marian Consort performs across the UK and Europe: recent highlights have included recitals at King’s Place, the Barcelona Early Music Festival and the A Cappella Festival in Leipzig; concerts for the La Caixa concert series in Girona and the Brighton Early Music Festival,

the latter in collaboration with actor Finbar Lynch; and performances at the Wellcome Collection and the British Academy.

The Marian Consort has released three CDs with Delphian Records: the first, of Marian devotional music of the Spanish Renaissance (O Virgo Benedicta, DCD34086), invited praise from reviewers for its ‘fluent performances’ and ‘flawlessly executed programme’, and was singled out by Andrew McGregor on Radio 3’s CD Review for its ‘attractive and arresting sound’. The second, of English and continental Renaissance music from the Dow partbooks (An Emerald in a Work of Gold, DCD34115) received outstanding reviews in all of the major broadsheets, with The Scotsman giving it five stars and the Sunday Times calling it ‘exquisite … The ensemble sings with eloquence and expressive finesse.’

Their third recording, of music by the Parisian Renaissance composer Jean Maillard (DCD34130), was released in September 2013, attracting praise for its ‘precision and pellucid textures’, with The Guardian noting that ‘The performances are models of discretion and musical taste, every texture clear, every phrase beautifully shaped.’

Rory McCleery began his musical career as a chorister at St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh under Timothy Byram-Wigfield and Matthew Owens. He gained a double first in music at Oxford University as both Organ and Domus Academic scholar of St Peter’s College, subsequently completing an MSt in Musicology with Distinction.

Rory is the founder and musical director of The Marian Consort, with whom he performs across the UK and Europe. He has recorded three highly-lauded CDs with the ensemble for Delphian Records Ltd, and they appear regularly on the radio both in the UK and abroad. Under his direction, The Marian Consort has become renowned for its compelling interpretations of a wide range of repertoire, particularly the music of the Renaissance and early Baroque, but also works by contemporary British composers.

As a countertenor, Rory greatly enjoys working as a soloist and consort singer in concert and recording with ensembles including The Sixteen, Monteverdi Choir, Gabrieli Consort,

Contrapunctus, Dunedin Consort, Tallis Scholars, Le Concert d’Astrée, the Academy of Ancient Music, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and The Cardinall’s Musick.

Recent solo performances have included Bach St John and St Matthew Passions; Handel Messiah, Dixit Dominus and Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne; Pärt Passio; Purcell Come ye Sons of Art, Ode to St Cecilia and Welcome to All the Pleasures; Monteverdi Vespers of 1610; Rameau grands motets; and Britten Abraham and Isaac in venues across the UK and Europe. Rory has appeared as a soloist for broadcasts on Radio France, BBC Radio 3 and German and Italian radio, and collaborates regularly with the Rose Consort of Viols.

Rory is much in demand as a conductor, chorus master and workshop leader, and is a passionate believer in the importance of music education and singing for young people. He is also currently engaged in doctoral research at the University of Oxford, centred on the French Renaissance composer Jean Mouton, and acts as an academic and programming consultant to festivals and many of the ensembles with whom he performs.

O Virgo Benedicta:

Music of Marian Devotion from Spain’s Century of Gold

The Marian Consort, Rory McCleery director DCD34086

A six-strong Marian Consort makes its Delphian debut in a programme celebrating the rich compositional legacy of the Siglo del Oro’s intensely competitive musical culture. These luminous works – centred on the figure of the Virgin Mary – demand performances of great intelligence and vocal commitment, and the youthful singers respond absolutely, bringing hushed intimacy and bristling excitement to some of the most gorgeously searing lines in the history of European polyphony.

‘Precision of tuning and purity of tone … I gained a great deal of pleasure from listening to this flawlessly executed programme’

— John Quinn, MusicWeb International, June 2011

An Emerald in a Work of Gold: Music from the Dow Partbooks

The Marian Consort, Rose Consort of Viols

DCD34115

For their second Delphian recording, The Marian Consort have leafed through the beautifully calligraphed pages of the partbooks compiled in Oxford between 1581 and 1588 by the Elizabethan scholar Robert Dow. Sumptuous motets, melancholy consort songs and intricate, harmonically daring viol fantasies are seamlessly interwoven – all brought to life by seven voices and the robust plangency of the Rose Consort of Viols in the chapel of All Souls College, Oxford, where Dow himself was once a Fellow.

‘cleanly and calmly delivered … the concluding Ave Maria by Robert Parsons is superb, the final “Amen” attaining to genuine emotion but without the saccharine reverence that this much-recorded piece can attract’ — Gramophone, February 2013

Jean Maillard (fl. 1538–70): Missa Je suis déshéritée & Motets

The Marian Consort, Rory McCleery director DCD34130

Jean Maillard’s life is shrouded in mystery, and his music is rarely heard today. Yet in his own time his works were both influential and widely known: indeed, the musicologist François Lesure held him to have been one of the most important French composers of his era. Who better, then, than

The Marian Consort and Rory McCleery, a scholar as well as a performer of rising acclaim, to give this composer’s rich and varied output its first dedicated recording? Their characteristically precise and yet impassioned performances bring out both the network of influence in which Maillard’s music participated – its Josquinian pedigree, and influence on successors including Lassus and Palestrina – and its striking, individual beauty.

‘The performances are models of discretion and musical taste, every texture clear, every phrase beautifully shaped’

The Guardian, October 2013

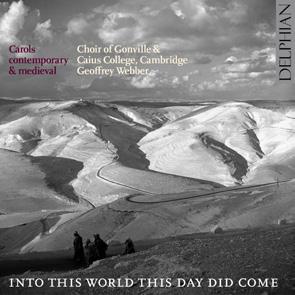

Into this World this Day did come: carols contemporary & medieval Choir of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge / Geoffrey Webber

DCD34075

A characteristically intriguing and unusual programme from Geoffrey Webber’s choir combines English works from the 12th to 16th centuries with medievally-inspired carols by some of our finest living composers.

From the plangent innocence of William Sweeney’s The Innumerable Christ to the shining antiphony of Diana Burrell’s Creator of the Stars of Night, this selection will seduce and enchant. The choir combines polish with verve, and Webber’s meticulous attention to detail is floodlit by the bathing acoustics of St Anne’s Cathedral, Belfast.

‘stunning … an unflinching modern sound with an irresistible spiritual dimension’

Norman Lebrecht, www.scena.org, December 2009