Robert Motherwell Paintings and Collages

a catalogue raisonné, 1941–1991

volume one

essays and references

jack flam, katy rogers, and tim clifford

yale university press, new haven and london

This project was initially organized by Joachim Pissarro.

Publication of the catalogue raisonné has been supported by The Dedalus Foundation, Inc.

Copyright © 2012 by The Dedalus Foundation, Inc., and Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Essays by Jack Flam copyright © Jack Flam. Essays by Katy Rogers copyright © Katy Rogers.

Works by Robert Motherwell copyright © The Dedalus Foundation, Inc., licensed by VAGA, New York.

Designed by Katy Homans

Set in Plantin and Scala sans type by Tina Henderson Printed in Verona, Italy, by Trifolio

3 volumes isBn 978-0-300-14915-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Flam, Jack D.

Robert Motherwell paintings and collages : a catalogue raisonné, 1941–1991 / Jack Flam, Katy Rogers, and Tim Clifford. v. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: 1. Essays and references — isBn 978-0-300-14915-9 (3 hardcover volumes in slipcase : alk. paper) 1. Motherwell, Robert—Catalogues raisonnés. I. Rogers, Katy. II. Clifford, Tim, 1969– III. Motherwell, Robert. IV. Title. N6537.M67A4 2012 759.13—dc22

2010029185

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The paper in this book meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

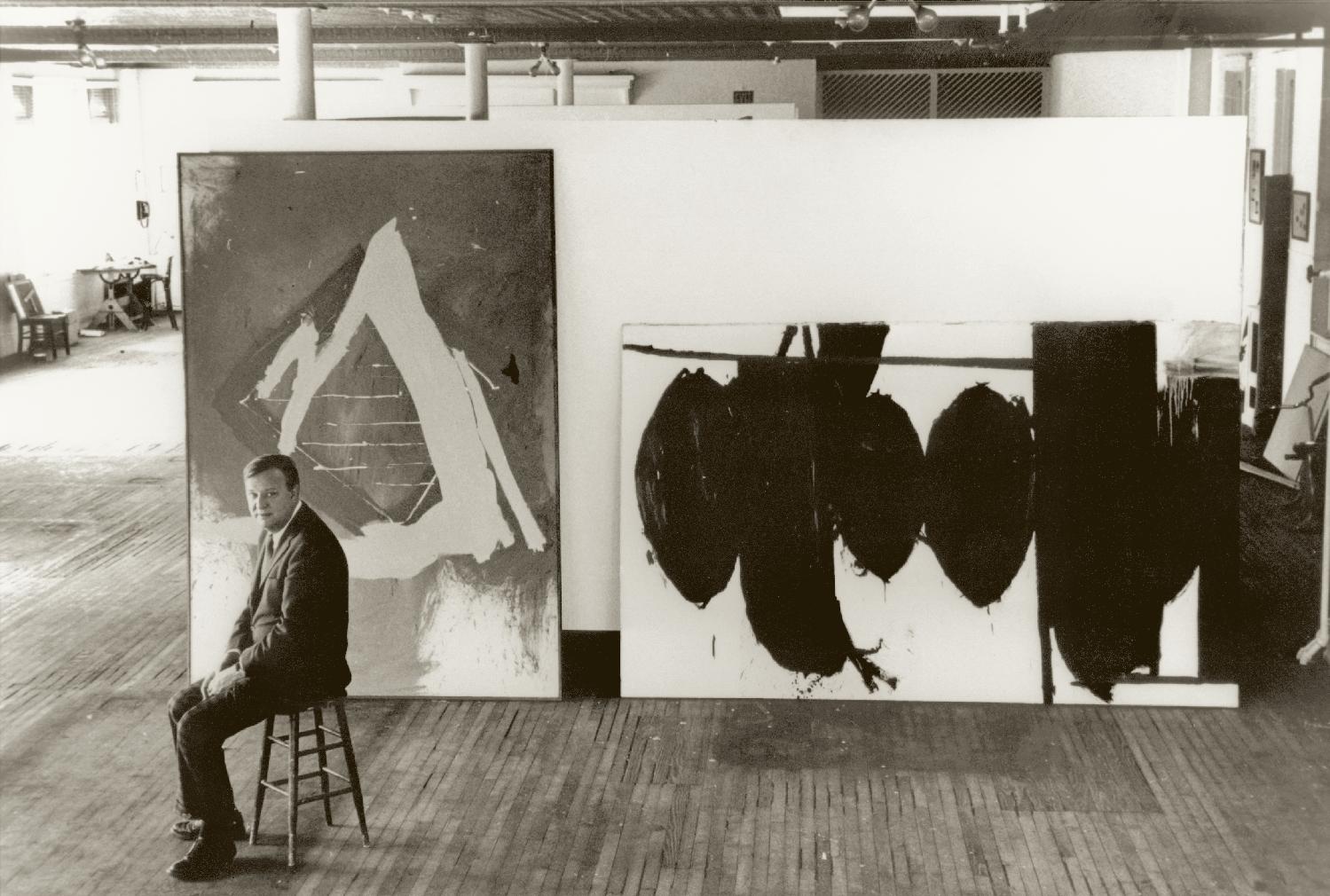

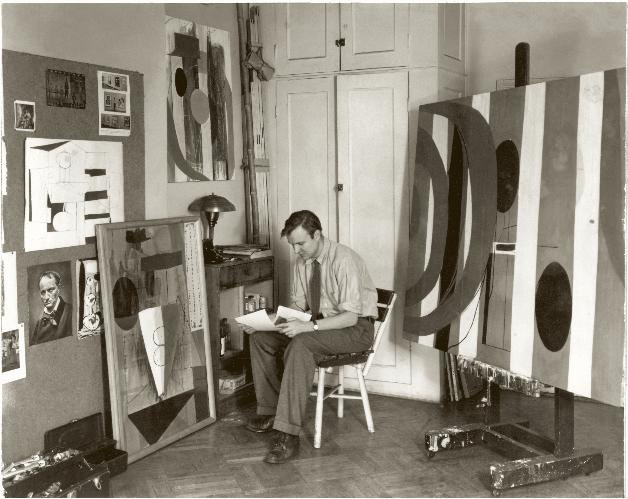

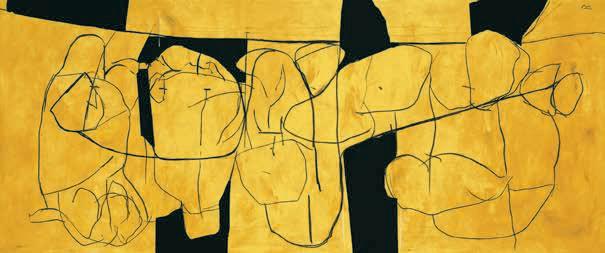

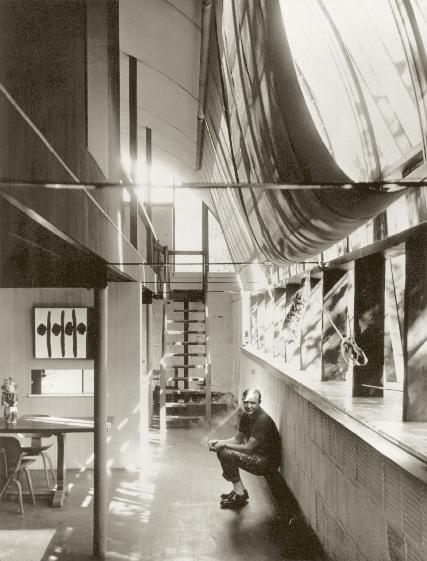

Frontispiece: Robert Motherwell in his studio, ca. 1945 (fig. 32) Slipcase: Details of Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 70 (p220)

volume one

preface | Jack Flam

acknowledgments

introduction Robert Motherwell at Work | Jack Flam

chapter 1 Paintings, 1941–1944: Finding a Voice | Jack Flam

chapter 2 Collages, 1943–1949: A New Medium | Katy Rogers

chapter 3 Paintings, 1944–1948: All That Is Serious and Ambitious | Jack Flam

chapter 4 Paintings, 1948–1958: Elegies to the Spanish Republic | Jack Flam

chapter 5 Collages, 1950–1957: The Tearingness of Collaging | Katy Rogers

chapter 6 Paintings, 1958–1967: Two Figures | Jack Flam

chapter 7 Collages, 1958–1970: Intersections | Katy Rogers

chapter 8 Paintings, 1967–1974: Opens and Signs | Jack Flam

chapter 9 Collages, 1971–1991: Variation and Seriality | Katy Rogers

chapter 10 Paintings, 1975–1991: Inventions and Reinventions | Jack Flam

chronology | Tim Clifford

the making of a motherwell catalogue raisonné | Jack Flam

usage guide to the catalogue entries

early works

list of exhi B itions

Bi B liography, writings B y the artist, and filmography

index of titles and alternative titles

index of owners

index of the chapters, chronology, and catalogue raisonné entry comments

concordance of catalogue raisonné and studio inventory num B ers

photo and text credits

a B out the authors

v ol ume t w o

key to the catalogue entries

Paintings on Canvas and Panel

v ol ume t hree

key to the catalogue entries

Collages

Paintings on Paper and Paperboard

t his B ook is for me the culmination of a direct engagement with r o B ert m otherwell and his work that goes back over thirty years.

I had known and admired Motherwell’s paintings since my student days, when he already had a kind of legendary status as both an artist and a thinker. So when we first arranged to meet, in January 1979, after a mutual friend put us in touch, I expected him to be a rather austere and remote figure.

But the man who met me at the Greenwich train station that cold, sunny day was surprisingly down-to-earth. Tall, slightly stooped, physically awkward in an oddly graceful way, and with an engag ingly open face, he had a very particular way of speaking: calm, measured, with more pauses than most people, but also with a kind of lilting rhythm that was paradoxically both rather flat in tone and extremely animated. After we had greeted each other and started to walk toward his car, I realized that he had skipped the usual small talk and instead we immediately began to discuss a number of subjects of mutual interest: what could be understood about an artist from his writings, the relative virtues of mixed and unmixed colors, the importance of touch in modern painting. He was also disarmingly candid about very personal matters, his professional problems, and problems with his family and his marriage, which he talked about in a most matter-of-fact and unembarrassed way. By the end of the twenty-minute drive from the train station to his studio, I felt as if I’d known him for years.

We soon became close friends and worked together on a number of projects, beginning with the revival of the Documents of Twentieth Century Art, the series of historical anthologies that Motherwell had founded in 1943–44 as the Documents of Modern Art. In all our conversations, he was remarkably straightforward and candid about what was on his mind, and about what was going on in his life. As I got to know him better, I realized that his remarkable openness came from his deeply held belief that we all share the same problems of existence, and so are bound to be open with each other about our anxieties, doubts, and paths to joy.

Motherwell was an exceptional man as well as a great artist. He literally radiated intelligence, but he was also quietly plainspoken—and quite knowledgeable—about an enormous range of subjects. He was also a very special kind of friend—constantly interested in what was happening to you, what you were thinking about, what you were working on, and what you were going to do next. And because he was so judicious, it was only natural that from time to time you would seek his advice. His response to those requests was revealing. Most people love to tell others what they should do. But he did not. Instead, he would listen very carefully to your account of your situation. And then he would begin to tell you something that seemed to have absolutely nothing at all to do with what you had been talking about, but which you would gradually realize was being offered as—not exactly advice, in terms of a specific course of action, but something much more valuable—a sober analysis of your situation, seen clearly, free of illusion and self-delusion. The raw material with which to make your own decision. Sometimes he capped off what he had to tell you with a general principle, always modestly but firmly stated, such as, “One of the things that I’ve learned from psychoanalysis is not to invent false moral conflicts.”

He was one of the most direct and clearheaded people I have ever known, a man who consistently told you what was on his mind, gracefully but in the most forthright way possible. He was also perpetually fascinated by the complexity of events and people. So when he told a story (as when he

gave advice), he loved to go off on long tangents about things that seemed completely unrelated to what he was telling you about. And then, just when you were sure that he had lost the thread—or maybe that there wasn’t any thread to begin with—he would come zooming back to the main point with an intensity and a richness of insight that were positively awe-inspiring. In fact, his digressions were an integral part of what he wanted to convey to you. They allowed you to see not only his conclusions but the complexities behind them; as in his paintings, he wanted you to understand how the process of saying something was an essential aspect of what was being said.

Nothing was simple to him, and nothing was simple for him. He struggled with inner demons all his life, and he made no bones about it. This was the struggle that gave his paintings much of their force, and that gave him the kind of ethical and spiritual weight he had, his unwavering sense of the necessity for right action. Nowhere was this more evident than in his pictures and in the demands that he placed on himself when he worked. Many people who worked with him had the experience of watching him finish something and then, at the last minute, decide that it wasn’t finished after all— sometimes, even, that it had to be started all over again—no matter the cost in time, energy, money. He himself was such an open-minded person, so tolerant of imperfection in the world around him, that it seems odd to say that he was a perfectionist. But he was, especially in his work.

In fact, I think he was a perfectionist in everything that concerned him directly. He wanted to get things exactly right, and he worked at them until he did. One of the most impressive things about him was the absolute consistency between himself as a man and as an artist. Looking at his paintings and talking to him, for example, were continuous experiences. His vision of the world—the level to which he pitched his thoughts and feelings—was consistently on a very high plane, though also always humane, supple, and decent. Although he could make charming small talk when he had to, most of his conversation was something like the opposite of small talk. In his conversation, as in his painting, he concentrated on what really mattered—putting together clear, often basic insights and making them into something rich and profound.

Everyone who knew him well knew that Motherwell had a deep and long-standing preoccupation with death. And this, too, was reflected in his work. In the months just before he died, especially, the imminence of his end seemed to weigh more heavily on him than it had previously. He was too clearsighted for it to be otherwise. Several times, he proposed that we go to his warehouse together so that he could “edit” his earlier works; by which he clearly meant, destroy those that he felt did not rise to the standard he had for himself. (This was an issue on which he was deeply conflicted: there were works that he thought would be best destroyed, but it was very hard for him to destroy any of his work.) The last time he proposed such a warehouse visit was in the late spring of 1991, just a few months before he died. When the visit had to be postponed to the fall because he was not feeling well, he said to me that if something happened to him before the fall, I should go out to the warehouse and edit the work myself. I told him, as he no doubt knew I would, that it would be humanly, professionally, and ethically impossible for me to do that without him. He nodded, but did not say anything. That was the last time I saw him. That day, after he and I had spent the afternoon together in his studio, I asked him how he was feeling. He hesitated for a while, one of those long silences that he often lost himself in when you asked

him about something important. Then, very quietly, he told me that he felt like someone engaged in reading a very long and very absorbing novel in several volumes. And now, he said, he was aware of having picked up the final volume. “As with any book you love, you don’t want it to end,” he said, “but of course it has to.” I was struck by the serenity of his voice, by the even calm that perhaps for the first time implied acceptance. It was a serenity, I think, that was fed by his sense of having been able to work with full concentration right to the very end, and of having created a body of work that counted for something important among human accomplishments.

Certain artists and writers have such active social lives that we marvel at how they got so much work done. Hemingway was like that, and so was Picasso. Motherwell was like that, too. Especially during the years he was in New York, he had a lively and varied social life, and he seemed to know every artist, writer, thinker, and theater person worth knowing. But the reality was that he spent most of his time working; the social events, and the lunches and dinners with friends or professional acquaintances, were respites from the long hours of work. Just how much he worked is made apparent in this catalogue raisonné, which includes almost three thousand individual paintings and collages. If the drawings had been added, the size of the total body of work would have been increased by around 50 percent. If he worked so much, it was because he worked in order to keep alive—in order to keep from going mad or destroying himself. He suffered, but he had an aristocratic reserve about his suffering, as well as about his enthusiasms. At social gatherings, he was surprisingly shy, and people often mistook his shyness for aloofness. And because he had taken on the role of spokesman for his generation as far back as the 1940s, a number of people resented his prestige and what they saw as his power within the politics of the art world. For many years, he was a juror for the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation’s fellowships for artists. After it was known that Motherwell and I were friends, a number of people came up to complain, “Your friend Motherwell didn’t give me a Guggenheim.” More rarely, something like the opposite happened, as when a colleague whose kind of painting Motherwell did not particularly care for told me that he knew Motherwell liked his work because he had received a Guggenheim fellowship. All of these people ignored the fact that the Guggenheim fellowship jury had four other member s on it, who, like Motherwell, were each allowed to cast one vote. (And I can say from my own later experience on that jury that the results of the voting were rigorously followed.) The myth, though, was that from behind the scenes Motherwell controlled everything with which he was in any way involved.

Motherwell was a dedicated teacher. When he was hired by Hunter College in 1951, he founded one of the first graduate programs in modern art in the United States. Even after he retired from Hunter in 1959 in order to paint full time, he continued to lecture, and to support younger artists. He respected, above all, courage in artists. As early as 1951, he wrote a crucial essay about the paintings of Cy Twombly, which helped launch Twombly’s career. And I remember Motherwell expressing admiration for Julian Schnabel during the early 1980s because of the freedom and daring behind the smashed plates in Schnabel’s paintings of the time.

Finally, I would like to recall an anecdote that casts an oblique but interesting light on Motherwell’s artistic procedure. During August 1982, my wife and daughter and I went to Provincetown

for a few days to join Bob and Renate Motherwell for their tenth wedding anniversary. On the last day we were there, we accompanied Renate in one of her favorite pastimes: antiquing. At one of the many shops we visited that afternoon, my four-year-old daughter Laura found a large straw hamper made in Thailand, for which the cover was a highly stylized straw horse’s head with brightly colored marbles for eyes. It was a striking object, at once charming and rather spooky: the marble eyes produced the effect of a strong but vacant stare. Laura loved it for its odd mixture of spookiness and charm—like the image of a semi-tame fairy-tale monster.

As we prepared to leave Provincetown, we went to say good-bye to Bob, who was sitting on the deck behind his house. He walked toward us with a smile on his face, then stopped dead in his tracks, and backed up half a step, as though he had been slapped. He had been caught by the stare of the marble-eyed straw horse. He quickly recovered himself, and we took our leave.

At the end of the summer, when I made my annual visit to the Greenwich studio to see what he had done in Provincetown, I was surprised to find a handful of small paintings of the same straw horse that I had now been living with for a couple of months (see p1055–p1057, c681). His dealer, Bob told me, had recently come by and found these paintings weird, and did not want to show them. Bob rather liked them, though, even though he conceded that they were quite unusual for him. He wondered why that particular image had come to him, and said it was like something that would come to a child, or in dream. “Why, it’s Laura’s straw horse,” I said. “Remember, the one with the marbles for eyes?” He paused for a moment, then replied, “Of course, that’s what it was.”

I recount this story because it indicates how alert Motherwell the artist was to what was going on around him, how open he was to catching experience on the fly, especially if it dealt with a subject that connected to the part of him that was primitive or childlike.

It was a great privilege to have known and worked so closely with Robert Motherwell, and I believe that he would be pleased to know that our collaboration has in a sense been continued beyond his lifetime by my engagement with this catalogue raisonné of his paintings and collages. I also know that he would be greatly pleased to see that the force and complexity of his work have been so well understood by a younger generation of scholars, so well exemplified in the enthusiasm and dedication that my coauthors Katy Rogers and Tim Clifford have brought to every phase of this project.

t he authors would like to acknowledge all the help, support, and cooperation that we have received from so many people and institutions. Foremost is the Dedalus Foundation, which has sponsored the research that went into this publication from the inception of the project. The Dedalus Foundation was created by Robert Motherwell and inherited all of his studio records and per sonal archives, along with almost all the works of art in his possession at the time of his death, and the copyr ight to all of his art and writings. All studio records and personal archives that are referred to in this publication—including studio photographs, datebooks, and studio inventory cards—can be found in the Dedalus Foundation Archives.

The members of the board of directors of the Dedalus Foundation—Dore Ashton, John Elderfield, Jack Flam, Steven R. Howard, David Rosand, Richard Rubin, and Morgan Spangle—have been unflinching in their support of this project. An important role was also played by the members of the Scientific Committee of the Robert Motherwell catalogue raisonné project: Dore Ashton, Tim Clifford, John Elderfield, Jack Flam, Katy Rogers, and David Rosand. During the years since this project was initiated in 2001, a number of people at the Dedalus Foundation made important contributions to the organization and research that the project entailed. Joachim Pissarro was the first director of the catalogue raisonné project and was responsible for the initial organization of the research files and database. Although he was not in any way involved with the final form of this book, and therefore bears no responsibility for any faults it may have, we want to acknowledge the important role he played in the early phases of the project as a whole.

We would like to thank Allison Harding, who played such a capital role during her tenure as project manager, and who visited and documented so many works in European collections. Our thanks also go to Warren Ng, who laid the groundwork for the List of Exhibitions and also played an important part in the creation and editing of many of the catalogue entries. Special thanks go to Kerrigan Kessler, who scanned and corrected the illustrations for this book, and whose outstanding eye has helped to ensure the high quality of the reproductions; to Dalia Azim, who worked so well in many different domains, and who arranged photography sessions all over the world; to Emily Schlemowitz, who gave the final shape to both the Bibliography and the List of Exhibitions, synthesizing a vast amount of information in such an admirable way; and to Mary Fass, who did such excellent work on provenance, among other things. We would also like to express our heartfelt appreciation to a number of other researchers who during their time at the Dedalus Foundation made deeply appreciated contributions to this project: Cynthia Daignault, Vanessa Daou, Stamatina Gregory, Maggie Hansen, Ezra Howard, Mary Keefe, Mark Loiacono, Jon Lutz, Jeremy Melius, Don Meyer, Mariana Mogilevich, David Michael Perez, Jane Simon, and Jaqueline Vojta.

We also want to give warm thanks to Gretchen Opie, the archivist at the Dedalus Foundation, who supplied enormous amounts of information and whose resourcefulness and mastery of digital technology ser ved us so well throughout the course of the project. Michael Mahnke, the foundation’s collections manager, was constantly helpful in making works available to us for study, in providing photog raphy, and in giving us the benefit of his keen eye for the physical attributes of works.

Other members of the foundation staff who have buoyed the project with their support and assistance are Rosanne Casamassima, Jasmine Justice, Olivia Kalin, Tom Long, Sean Meehan, Jason Paradis, and Alice Stock.

Among the many museums and collections that have been so helpful, we want to cite especially the following, with special thanks to the people mentioned in parentheses: Albright-Knox Art Gallery (Laura Fleischmann); Anderson Collection; Archives of American Art (Judy Throm); Art Gallery of Ontario (Greg Humeniuk and Felicia Cukier); Art Institute of Chicago (Barbara Hinde and Nora Riccio); Baltimore Museum of Art (Jay Fischer and Darsie Alexander); Birmingham Museum of Art (Melissa Falkner Mercurio); Brooklyn Museum (Ruth Janson); Carnegie Museum of Art (Laurel Mitchell); Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne (Jean-Paul Ameline and Evelyne Pomey); Cleveland Museum of Art (Marcia Steele and Joan Neubecker); Columbia Museum of Art (Noelle Rice); Corcoran Gallery of Art; Delaware Art Museum (Jennifer Holl); Denver Art Museum (Lewis I. Sharp and Jill Desmond); the Detroit Institute of Fine Arts (Rebecca Hart); Fine Arts Work Center, Provincetown; Fogg Art Museum, Harvard (Jessica Ficken); Frederick R. Weisman Foundation; Fundació Joan Miró; Fundación Juan March (Aida Capa); Getty Archives (the late James M. Wood, David Farneth, Kate Ralston, and Wim de Wit); Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (Ainhoa Sanz); Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington (Judy Sourakli); Hess Collection (Myrtha Steiner); High Museum of Art (Sara Hindmarch); Hood Museum of Art (Kathleen O’Malley); Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts; the Jewish Museum (Karen Levitov and Sari Cohen); John F. Kennedy Federal Building in Boston (Frederick Amey and Janine Kurth); Kunstmuseum Basel; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Elma O’Donoghue); the Lucid Art Foundation (Dr. Fariba Bogzaran); the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Lucy Belloli and Shawn Digney-Peer); the Meyer Schapiro Archive at Columbia University; Milwaukee Art Museum (Melissa Hartley Omholt); Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (Marla Price, Michael Auping, and Wendy Griffiths); the Montclair Art Museum (Gail Stavitsky); Mount Holyoke College Art Museum; Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Museum of Art; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Soledad de Pablo); Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Museum of Modern Art (Milan Hughston, Michelle Elligott, Jim Coddington, and Carrie McGee); Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Wien; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (Jay Krueger and Carlotta Owens); National Gallery of Australia (Christine Dixon); Nelson A. Rockefeller Collection (Cynthia Altman); the Newark Museum (Tricia Laughlin Bloom); Norton Museum of Art (Karol Lurie); Peggy Guggenheim Collection (Philip Rylands and Jasper Sharp); Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts; Philadelphia Museum of Art (Michael Taylor); Phillips Collection (Joe Holbach); Pinakothek der Moderne; Princeton University Art Museum (Calvin Brown); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Seattle Art Museum (Michael Darling); Smith College Museum of Art (Louise Laplante); Smithsonian American Art Museum (James Concha); Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (Francine Snyder); Sprengel Museum Hannover; Staatsgalerie Stuttgart; Tate Modern (Nicholas Serota and Patricia Smithen); Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art; Walker Art Center (Joe King); Whitney Museum of American Art (Adam Weinberg, Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, and Anita Duquette); Wichita Art Museum (Kirk Eck); and Yale University Art Gallery (Susan Greenwalt and Elisabeth Hodermarsky).

Among the many art dealers and galleries that have helped us, we want to single out the significant assistance we received from Knoedler & Company (Melissa de Medeiros); Ameringer McEnery Yohe (Miles McEnery); Carroll Janis and Jeanie Deans at the Sidney Janis Gallery archives; Galerie Lelong (Patrice Cotensin and Nathalie Berghege-Compoint); Bernard Jacobson Gallery (Bernard Jacobson and Janey McAllester); and the Locks Gallery (Sueyen Locks and Philip Mott). We also want to thank the following galleries and dealers for their help and consideration: Acquavella Galleries; John Berggruen Gallery; Mark Borghi Fine Art (Shannon K. McEneaney); the late André Emmerich; Leslie Feeley; Gagosian Gallery (Rose Dergan); James Goodman Gallery (Patsy Tomkins); Richard Gray Gallery (Susanna Hedblom); Greenberg Van Doren Gallery (Courtney Flynn); Bobbie Greenfield; Hackett-Freedman Gallery; Leonard Hutton Gallery (Ingrid Hutton); Bernd Klüser; Margo Leavin Gallery (Wendy Brandow); Meredith Long & Company; Marlborough Fine Art (Tara Reddi); Marlborough Galleria d’Arte (Carla Panicali); Thomas McCormick; David McKee; Jerald Melberg Gallery; David Mirvish; Edward Tyler Nahem (Edward Tyler Nahem and Jamie Katz); Jonathan Novak Contemporary Art (Janelle White); Gerald Peters Gallery; Lawrence Rubin; Leslie Sacks Fine Art (Annie Won); Pascal de Sarthe Fine Art; William Shearburn Gallery (Katherine Rodway and William Shearburn); Manny Silverman Gallery (Manny Silverman and Linda Hooper); and the Waddington Galleries (Clare Preston).

The staff at several auction houses have been very generous with their time and in sharing resources. In particular we wish to thank Christie’s New York (Marley Lewis and Sara Friedlander); Doyle New York (Harold Porcher); and Sotheby’s New York (Mary Ballantyne, Sheila Debrunner, and Johanna Flaum).

We have also benefited from the advice and information given us by a number of enthusiasts, scholars, and collectors of the work of Robert Motherwell, most especially Jon Yard Arnason and Eleanor A. Arnason, Dr. Carmel Friedman, Gregory Gilbert, John McKenzie, Ed Meneeley, Dr. Francis V. O’Connor, Maria Reinshagen, Martica Sawin, Martha Gearhart Schermerhorn, Seán Sweeney, Eugene Victor Thaw, Ulli Willi, Amy Winter, and Jonathan Ziady.

Our thanks also to all our researchers and technical advisers, especially Barbara Rockenbach, for her bibliographical work; Luisa Restrepo, for help with foreign languages; Suzannah Massen, for her research on auctions; Daniel Callahan, for his impressively thorough research regarding the sheet music that Motherwell used in his collages; George Kondogianis, for his color expertise; and Dan Peck, for the exceptional job he did of designing the initial database for the project and of updating it as necessary. Special thanks go to Fronia Simpson, for her alert reading of early drafts of the essays and Chronology, and for her many constructive suggestions.

We have also benefited from the work of photographers all over the world, and in particular from the very fine sustained photographic work of the late Oren Slor, and of Jordan Tinker, who did the bulk of the local photography for us; also Eduardo Calderon, David Carmack, Brian Forrest, Lee Stalworth, Michael Tropea, and John Wilson White.

A number of Robert Motherwell’s personal friends, studio assistants, collaborators, and family members have been extremely generous in sharing their knowledge with us. We want to give special

thanks to Richard Aakre, Ethel Baziotes, the late William Bosschart, E. A. Carmean Jr., Heidi and Claus Colsman-Freyberger, Jane Crawford, John Murray Cuddihy, Betty Fiske, Helen Frankenthaler and her assistant Maureen St. Onge, the late B. H. Friedman and his assistant Jean Reynolds, Milton Gendel, the late Walter K. Helmuth, Barbara Kafka, Dr. Christian Kloyber, Catherine Mosley, Lise and Jeannie Motherwell, the late Arnold Newman, Mel Paskell, the late Philip Pavia and his wife Natalie Edgar, Barbara Poe Levee, Michel Ragon, the late Maria Runyan and her associate Lisa Van Der Sluis, John Scofield, Chloe Scott, the late Charles Seliger, Nina Sundell, the late Yvonne Thomas, Kenneth E. Tyler, the late Dr. Montague A. Ullman, Paul Waring, and Virginia Waring.

We would also like to thank our colleagues at other foundations who have so generously assisted us with advice and information: Charles C. Bergman and Kerri Buitrago at the Pollock-Krasner Foundation; Sanford Hirsch at the Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation; Richard Grant and Andrea Liguori at the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation; Amy Schichtel at the Willem de Kooning Foundation; Alessandra Carnielli at the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation; and Christopher Rothko at the Mark Rothko Foundation.

A project such as this also draws upon the knowledge and skills of a number of specialists. We would like to express our thanks to three scientist-conservators who have made especially important contributions to the study of Robert Motherwell’s work: James Martin of Orion Analytical; Matthew Skopek, senior conservator at the Whitney Museum of American Art; and Dana Cranmer of Dana Cranmer Associates.

Anyone who writes on Robert Motherwell owes a great debt to four scholars who have done important original research on the artist: the late H. H. Arnason; E. A. Carmean Jr.; Robert C. Hobbs; and Robert Mattison.

Finally, we want to give heartfelt thanks to the team of dedicated people at Yale University Press who have contributed so much to the final quality of this book; to Patricia Fidler, publisher, art and architecture, who has been an enthusiastic supporter of this project right from the beginning; to Kate Zanzucchi, senior production editor, art books, and managing editor, special projects, for her patience and attention to detail, and for coordinating the project so seamlessly and with such grace; to Katy Homans, for the intelligence and fine aesthetic sensibility that she brought to the design of this book; to Miranda Ottewell, for her excellent copyediting of the manuscript; and to Ken Wong, production manager, for overseeing the production of the book with such loving care.

a catalogue raisonné entails the examination of everything that an artist leaves B ehind as his body of work. Unlike other comprehensive views of an artist’s production, such as a retrospective exhibition or a monographic book, a catalogue raisonné is not a selection.1 In principle, it leaves nothing out: the artist appears before his public warts and all, in his glorious moments and in his flat spots, with his breakthroughs and his self-deceptions. Because of its inclusiveness, and its relative objectivity, a catalogue raisonné can tell us things about an artist that nothing else can. Thematic currents and leitmotifs beg in to emerge that even the artist himself may not have been conscious of. The works that are gathered together both reinforce and belie some of the artist’s myths about himself. The net effect of the works illustrated in such a book is very different from that produced by the kind of careful editing that informs other kinds of compilations and publications. In a catalogue raisonné the body of facts is too vast to be completely manageable, too unruly or contradictory to be given a single focus. The artist emerges in all his complexity.

As a result, all catalogues raisonnés are full of surprises. Works that were never meant to be seen together—even works that were never meant to be seen at all—are illustrated side by side, page after page, reduced to flattened images of reproducible size. The sheer volume of the imagery and information such a book contains has a kind of built-in distortion, in that it invites us—indeed forces us—to see an artist’s work as it has never been seen before. Such completeness, however, also has the great advantage of allowing us to see how the mind of a great artist works across the whole spectrum of his experiences and possibilities, in the same way as the collected works of a major poet.

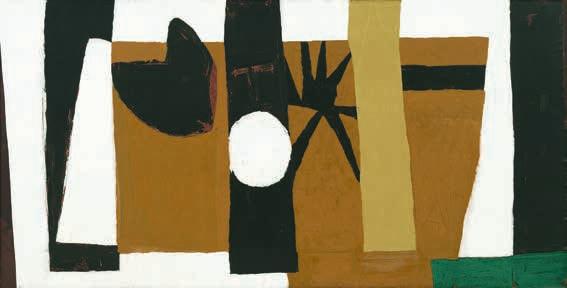

During a career that lasted half a century, Robert Motherwell created a large and powerful body of work. He also realized one of any artist’s most cherished dreams, that of producing significant works right to the very end of his life. As this catalogue raisonné makes clear, Motherwell’s oeuvre is also immensely varied. Unlike most of his colleagues, who came to be known for a single type of image that to some degree became a kind of trademark—Jackson Pollock’s intricate webs of dripped paint; Mark Rothko’s pulsing, stacked fields of color; Barnett Newman’s broad planes punctuated by vertical stripes; Clyfford Still’s jagged curtains of pigment—Motherwell worked with a broad range of imagery, inventing, refining, and reinventing his signature motifs with great force and originality. He created a language of painting—a vocabulary of formal patterns, colors, and gestures—rather than a single, recognizable “image.” As a result, a number of different images are associated with his name, most prominently the Elegies to the Spanish Republic and the Opens. But as this catalogue makes clear, he created a number of other types of images that are among the most profound and inventive works of their time—including the Iberia, Je t’aime, Summertime in Italy, Beside the Sea, Drunk with Turpentine, and Hollow Men paintings—and one of the most important and original collage oeuvres of the twentieth century. His pictures are united not by consistency of image but by a predilection for certain combinations of forms and movements of the hand, a distinctive range of touch and color, and a marked gamut of feeling. He tended to work with small brushes in order to create intensely worked surfaces, and to apply his paint in a way that was at once quite lyrical and slightly awkward. He used carefully chosen combinations of colors, built upon the bedrock of a unifying polarity of blacks and whites—supposed “non-colors” that he invested with an impressive range of chromatic nuance—and a somewhat limited number of hues:

primarily ochres, blues, and reds, but also dusky earth colors and luminous oranges, sometimes punctuated by unexpected passages of brassy yellows, thrilling violets, or oddly unnatural-looking greens.

Motherwell’s imagery has a distinctive visual clarity. His pictures “read” clearly. Their legibility and their emphatic directness give them a remarkable coherence—made all the more impressive by the way their richly worked surfaces and subtle, painterly effects are set in counterpoint to their overall lucidity. Consequently, they are rewarding to look at both when seen from a distance and from close up, and even in reproduction.2 They are also lucid in another sense: even the very darkest ones contain a strong sense of light.

Motherwell’s varied imagery was a product of his complex, anguished inner being, and also an expression of his deeply held convictions about the nature of reality, which he believed to contain not a single truth but many relative truths, which could be only partially revealed and not explained. This is reflected in his fascination with the idea that the ancient Greeks had no word for truth. As he told an interviewer, “Socrates says something and it’s translated, What you say is true Socrates.” But as Motherwell pointed out, the Greek word was aletheia, which meant revealed, or unhidden. “And so a literal translation,” he noted, “would be you’ve unhidden that point, Socrates.”3

“And I love that concept,” Motherwell continued. “In that sense, I wish the word truth didn’t exist. Because one of the reasons I’ve been able to move all over the place is I take that for granted. Everybody has his own revelations, but the mass of the totality has never been revealed to anybody.” It was this hidden element of reality—buried within the unconscious, concealed beneath the flow of time and events, embedded in certain forms and symbols, inherent in certain colors and combinations of colors—that Motherwell pursued throughout his life as an artist. And because he chose to seek and encompass the variety of existence rather than embrace a single ideological stance, his artistic practice was remarkably complex.

This is perhaps the most striking thing that we learn from seeing all of Motherwell’s paintings and collages together: how powerful and how complex his pictures are, how strongly they resist easy categorization, and how deeply involved he was with the physical process of making his art—the laying down of paint stroke by stroke, the tearing of paper, the repeated reworking of individual paintings and collages. The evidence of this process was a major part of his “subject matter.” And his subject matter, as he himself said, was often quite literally painting itself. When one of his large pictures was mistakenly called Painter instead of Painting (p210), he contacted the director of the museum that owned it to ask that the title be corrected, saying, “What is depicted is not a painter but the process of painting.”4 When he went to Haiti in 1960 and saw a voodoo doctor perform a ceremony, he later recalled, his “heart stood still” when the Haitian got down on his hands and knees and began to paint symbols on the ground in ochre and white: “I paint on my hands and knees, using the same colors, using a symbolic language of my own. And I could have gone and kissed this voodoo doctor and cried, ‘I understand what you’re doing much better than I understand somebody painting a portrait!’ ”5

p rocess and c ontent

One aspect of Motherwell’s working procedure that has emerged from this catalogue raisonné has to do with the importance to him not only of painting but also of repainting or revising. Even people very familiar with his work will be surprised by the extraordinary amount of reworking that went into his paintings, and sometimes his collages. “The artistic struggle involves revision,” he wrote in 1977, “new points of attack, pondering, changes of mind, duration, endurance and so on. Traces of this conflict often remain in paintings & collages, like the corpses on a battle-field (and sometimes enrichens them with a terrible beauty).”6

Revision was a long-standing practice for Motherwell. The radical reworking of some of his earliest pictures, such as Wall Painting with Stripes of 1944–45 (see fig. 30), is well documented. In 1947, in one of his early exhibition catalogues, he wrote, “I begin a painting with a series of mistakes. The painting comes out of the correction of mistakes by feeling . . . an X-ray would disclose crimes—layers of consciousness, of willing.”7 More than thirty years later, in one of his most revealing discussions of the way in which the painting process was linked to self-identity, he significantly put his initial emphasis on the process of repainting. He recalled that while he was in a museum standing in front of his large 1975 painting In Black and White No. 2 (see fig. 154), a museumgoer had asked him what it “meant.” Motherwell said that the first thing he thought of was that the picture had “been painted over several times and radically changed, in shape, balances, and weights. At one time it was too black, at one time the rhythm of it was too regular, at one time there was not enough variation in the geometry of the shapes.”8

He then went on to say that seeing the painting again a few years after he had created it led him to realize that “there were about ten thousand brush strokes in it, and that each brush stroke is a decision. It is not only a decision of aesthetics—will this look more beautiful?—but a decision that concerns one’s inner I: is it getting too heavy, or too light? It has to do with one’s sense of sensuality: the surface is getting too coarse, or is not fluid enough. It has to do with one’s sense of life: is it airy enough, or is it leaden? It has to do with one’s own inner sense of weights: I happen to be a heavy, clumsy, awkward man, and if something gets too airy, even though I might admire it very much, it doesn’t feel like my self, my I.” In the end, Motherwell said, “I realize that whatever ‘meaning’ that picture has is just the accumulated ‘meaning’ of ten thousand brush strokes, each one being decided as it was painted. In that sense, to ask ‘what does this painting mean?’ is essentially unanswerable, except as the accumulation of hundreds of decisions with the brush. On a single day, or during a few hours, I might be in a very particular state, and make something much lighter, much heavier, much smaller, much bigger than I normally would. But when you steadily work at something over a period of time, your whole being must emerge.”

On the evidence of this declaration, and of many other statements Motherwell made over the years, we understand that he usually framed his undertaking as an artist in terms of “abstract art,” which for him meant creating visual equivalents for states of being and feeling. Yet as this catalogue raisonné makes evident, throughout his life he was deeply engaged with representation, both in the imagery of his works and in their titles. This was especially true in his early years, when a good deal of his

painted imagery was overtly figurative, as in The Emperor of China (fig. 37), The Homely Protestant (figs. 40, 42), and Man in Grey (p79). But it also runs through a good deal of his later imagery, as in the Pregnant Nude paintings of the early 1950s (p141–p144), the Two Figures paintings of the late 1950s and early 1960s (p174–p175, p207–p208, w34–w42), in works of the mid-1970s such as The Spartan (p796) and The Persian No. 1 (p789), and it continues into his late paintings, such as The Hollow Men (see fig. 163) and related pictures, which he worked on from 1983 until the end of his life.

Moreover, the imagery of his pictures, no matter how abstract they may appear, is almost always tied to something in the world, often to a specific place—albeit an idealized or reimagined one. Mexico, Spain, Italy, France, the bay at Provincetown, Massachusetts, all figure prominently in his work. Sometimes such pictures were done in the place they evoke, as with the Beside the Sea series, painted in Provincetown, and the first Summertime in Italy pictures, done in Alassio on the Ligurian coast. More frequently, as with most of the pictures that have Mexican and Spanish themes, they were done later, the emotion either “recollected in tranquility,” to use William Wordsworth’s phrase, or guided by yearning for a distant but still vital inspiration. Sometimes these places are evoked largely by titles (as with Mexican Window and Little Spanish Prison), or they are referred to in the materials the artist used, such as the magenta paper he associated with Mexico and incorporated into his 1940s collages, or the wrappers from French and German cigarettes that appear in his later collages. Frequently, a sense of place is referred to in the imagery of his work (as in the Iberia paintings with their evocation of Spanish fighting bulls, or in the Beside the Sea pictures, with their sprays of flung paint). A number of Motherwell’s early paintings also refer either directly or indirectly to political situations, as in Recuerdo de Coyoacán (see fig. 12), with its allusion to the assassination of Trotsky, or in Viva (see fig. 26), with its evocation of political graffiti and the Spanish Civil War song “Viva la quinta brigada.” Most famously, he overtly engaged political content in the titles of his Elegy to the Spanish Republic paintings, which sometimes opened him to controversy. After the political significance of the historical events that gave those paintings their titles had changed, Motherwell sometimes found himself open to criticism from both the left and the right.9

Motherwell was aware that for the modern artist direct illustration of political themes almost invariably produced mediocre art. So although his engagement with varied and specific political themes—which for him generally meant resistance to tyrannical authority—persisted in his later works, it did so indirectly, often through references in titles to historic and political events such as the looming troubles in Ireland, as in Dublin 1916, with Black and Tan, 1963–64 (p271) and Irish Elegy, 1965 (p340); tyranny in Africa, as in Uganda, 1975 (p833), and the African Plateau paintings (p834–p837); or the possibility of democracy in Spain, as in Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 108 (The Barcelona Elegy), 1966 (p364), and The Spanish Death, 1975 (fig. 132). Throughout Motherwell’s life, his art remained engaged with the important political and cultural currents of the time, rooted in deeply felt ethical beliefs. For him, aesthetic judgments were inextricably linked to ethical values.

A surprising number of works have also turned out to have strong autobiographical overtones. This is especially true of the collages, which Motherwell described as “a kind of careless, indirect diary.” When he saw them later, he said, they brought back “specific memories, that I had long thought that I

had forgot, like Marcel’s madeleine.”10 The Sea Lion sardine can labels that commemorated his trip to Canada with Helen Frankenthaler in 1959 (c92–c94), the pages of sheet music from German love songs that appeared in his collages around the time of his marriage to Renate Ponsold, and the references to Ponsold in the Baltic Sea Bride collages (c431–c436) are only a few of hundreds of such instances. Sometimes the autobiographical elements are expressed fairly overtly, as in Personage (Autoportrait) of 1943 (see fig. 25), where the artist’s head is represented by a palette shape, but sometimes they appear in unexpected places, privately coded—the sorts of things that are perhaps revealed only by the intense focus of a catalogue raisonné. For example, two tickets from a bullfight that he had seen during his 1958 honeymoon with Helen Frankenthaler, which had such a profound effect on his art—that is, both the bullfight and his first summer with Frankenthaler—are incorporated into two 1974 collages (c448, c453) done three years after their divorce, at once cast off and enshrined by the artist at the very time that he was purging Frankenthaler’s presence from his mind and under taking a new life with Ponsold.

At the same time, however, Motherwell, like most of his colleagues, was careful about not letting the sometimes implicit narrative aspects of his “subjects” become the main focus of his works. (One thinks of the way in which Jackson Pollock would sometimes turn a painting on its side before working further on it, in order to “bury” the figurative elements.)11 One of the basic tenets of much modernist art was resistance to narrative and the embrace of ambiguity—as an aesthetic, ethical, and philosophical value. In Motherwell’s work there is a continuous tension between abstraction and figuration; between his wanting his pictures to have a “subject” other than painting itself and yet wanting that subject not to be too overt, to remain just below the surface, waiting to be “unhidden” by the viewer.

Nonetheless, paradoxically, Motherwell would sometimes be surprisingly specific about the imagery of his work, as with Pancho Villa, Dead and Alive (see fig. 23), which he described in some detail in a Museum of Modern Art questionnaire a couple of years after he made it: “The picture represents Pancho Villa dead, on the left, with bloodstains, bullet holes etc.; & Pancho Villa alive, on the right, with a Mexican ‘wall paper’ behind him, + pink genitals. The personal + topical + symbolic significance are evident to anyone who sees it as I do; I have tried to ‘objectify’ (in Santayana’s sense) these values: i.e., make a picture.”12 Motherwell acknowledged that the picture had been inspired in part by a widely reproduced photograph of Villa riddled with bullet holes, and twenty years later, in a 1965 interview, he was moved to remark that most people had not noticed that one half of this collage “is a figure inside a coffin shape, covered with blood spots, and the other half is a figure with a pink penis hanging down— the penis being alive. Two portraits of Pancho Villa, one dead in the coffin, the other standing there alive!”13 Yet even in such descriptions of his pictures, Motherwell would go only so far. Because the imagery of Pancho Villa, Dead and Alive is quite abstract and he wanted the viewer to grasp its underlying nominal subject, he could not resist commenting on the subject and its sources. But while doing so, he left out what was perhaps the most salient aspect of its conception: that he had created it right after the death of his father.

i nstinct and i ntellect

Throughout his life, Motherwell was swept by conflicting crosscurrents of emotion, which are clearly reflected in his work. He was enamored of and exhilarated by the world and by the human comedy but also made despondent by it. Throughout his life, he expected much from the people he loved, and throughout his life he was disappointed by them—violent parents, unfaithful wives, disloyal friends. But he believed deeply that the existence of art—and especially the creation of it by himself and others— was a way of embracing and yet transcending what William Butler Yeats called “the fury and the mire of human veins.”14 The question was: As an artist, how to be enmeshed in the human experience and yet transcend it? How is it possible to cope with the disastrous aspects of one’s own personal experience and at the same time rise above the suffering that it produces? For Motherwell, the answer lay in his art. He was quite literally kept alive by the act of painting.

Motherwell’s formidable intelligence was both enhanced and resisted by his capacity for deep feeling, and the conflict between intellect and instinct formed one of the deepest undercurrents of his art. He approached the situations of his life and of his art with a remarkable flexibility and fluidity, constantly alert, his thought constantly in motion, his attitudes toward the world around him in a constant state of reappraisal. Although he had a strong inner compass, he also understood life to be contingent on circumstances. He repudiated ideologies and rigidly categorical thinking in every domain. Because he understood life to be complex and inconsistent, the nature of his work would by necessity be based on inconsistency, which he saw as the true dynamic that informed and underlay reality.

And so he worked, probing what it was possible for him to do in painting, as much as a way of exploring himself as to create an oeuvre per se. Painting was a way of finding out who he was. This is why his pictures are so diverse, so full of explorations. It is also why he kept working and reworking them, sometimes over a period of years. For him, the created work was to some degree an artifact, a field of activity that contained a record of feelings that could be revisited, reconsidered, revised.

Motherwell’s paintings and collages are marked by a number of oppositions, the most obvious of which could be characterized as the tension between spontaneity and deliberation, between pictures that appear to have been done with a minimum of planning, simply by letting the hand move, and pictures where the forms appear to have been laid down with great calculation. This tension underlay Motherwell’s compulsive need to rework his pictures, which was a way of readjusting the balances not only between forms but between different kinds of feeling. “The function of the artist is to express reality as felt,” he wrote in his first extended essay. “In saying this,” he added, “we must remember that ideas modify feelings.”15 The spontaneous, liberated, unthinking gesture had to be made, but it also had to be reshaped, modified, molded into an articulate whole. The contrast between signs of intellect and of instinct, between the extremes of severe geometry and irregular, biomorphic forms, is a leitmotif that runs throughout his work.

Motherwell’s artistic maturity coincided with his discovery in 1941 of the visual equivalent of the Surrealist concept of psychic automatism, which had been defined by André Breton as a way of expressing “verbally, or in writing, or in any other manner, the actual functioning of thought. Dictation of thought, in the absence of all control by reason and outside of all aesthetic or moral preoccupations.”16

Motherwell’s espousal of automatism and his insistence on spontaneity were part of a strategy to free himself not only from the constraints of conscious thought but from the sense of psychic suffocation that had characterized his childhood, where he was involved in a constant struggle with his parents to assert his own personality and values in the face of their desire to make him conform to their rigid social values. Brought up by a socially pretentious mother and a detached, indifferent father, he had a difficult and unhappy childhood. Both his parents, he later remembered, were inhibited, unhappy, and violent people who beat him mercilessly. His mother he described as “a certifiable psychopath,” who he said “used to beat me as a child till the blood would run out of my head.”17 He also suffered from asthma, and later recalled the terror induced by his nighttime asthma attacks. Until the end of his life, he preferred to paint at night, often working in his studio until the small hours of the morning in order to ward off the remnants of that terror.

This sense of struggle extended to the social world outside his family. In his youth, he was in constant rebellion against the puritanism of his surroundings, and sought its antidote in trying to open himself up as much as possible to sensual experience. One of the reasons that Europe played such a large role in his imagination was that, like many Americans at the time, he associated European life with greater sensuality and emotional freedom. Having grown up with the puritanical values imposed by his family, he associated creativity with freedom from parochial social norms and with being able to follow one’s own deepest impulses.

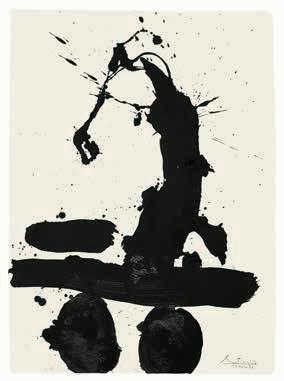

Psychic automatism was an ideal that Motherwell retained until the end of his life. The activity of “doodling,” as he sometimes referred to it, in order to tap into his deepest thoughts and impulses, underlay the creation of many of his paintings and drawings. Throughout his life he continued to rely on automatism to provoke and stimulate his pictorial imagination, and to act as what he called “a plastic weapon with which to invent new forms.”18 Automatism offered him a means both to probe his subconscious and to explore the possibilities of the mediums in which he worked, in ways that would have been otherwise closed to him. By allowing his hand free play, he was able to call forth images and feelings that were buried beneath the practical and logical parts of his consciousness. Pure psychic automatism was a kind of goal, an ideal to be striven toward to create new kinds of form. “What is essential is not that there need not be consciousness,” Motherwell noted, echoing Breton, “but that there be ‘no moral or aesthetic a priori’ prejudices . . . for obvious reasons for anyone who wants to dive into the depths of being.”19 The creation of spontaneous “automatic” imagery was part of the ongoing enterprise that Motherwell referred to as “my deepest painting problem, the bitterest struggle I have ever undertaken: to reject everything I do not feel and believe.”20

In the spring of 1941, just before he left on a life-changing trip to Mexico with the Chilean painter Roberto Matta, Motherwell used automatism to generate forms in some small works in mixed media (see ew.xvi and ew.xvii). His first mature oil painting, La Belle Mexicaine (Maria) (fig. 1), a por trait of Maria Emilia Ferreira y Moyers, who would become his first wife, began as an automatic composition in which the portrait image was painted over the field of abstract forms with which he had started the canvas. “What actually happened in my work,” Motherwell later recounted, “was that I began pictures automatically—the automatism consisting of dabs of paint scraped across the surface

of the canvas with razors or sticks or spatulas . . . but then in my efforts to resolve the picture a great deal of the canvas would slowly be covered over with a more formal, architectonic surface. Actually, in the portrait of Maria, done in Mexico, the primary automation is largely covered over with a portrait with its own structure. But the portrait would have had a different figuration if it were not being worked out also in relation to the primary automatism.”21

Right from the beginning of his mature work, then, Motherwell understood that the instinctive first casting of the image would need to be modified by a more thought-out intervention; that the process of creating a picture would involve moving back and forth between spontaneous forms that came from deep within the psyche and a process of modulation or what he called “correction,” in which the composition of the picture would be reshaped by a more conscious reworking of what had emerged. He often spoke of the process of creation as being like a voyage into the unknown, where the intended results and chance encounters would commingle with and inform each other, depending on the circumstances of creation: his state of mind, his feelings about the subject, the density or liquidity of the paint, the equilibrium he wanted to attain between spontaneity and calculation, or the degree to which he wanted figurative imagery to emerge or be kept at bay. Above all, he sought a balance between these many disparate elements. “The sense of a ‘voyage’ is crucial to the process of such works,” he later said, remarking that his 1952–54 painting Fishes with Red Stripe (w19) was a particularly successful example of this dynamic in that it “involves the void as well as figuration; it also involves both spontaneity and correction in equal measure. In a way, it is closest to what I have been after all my painting life.”22

Although Motherwell’s work and the circumstances in which he worked would change greatly over the next five decades, the basic elements of his general approach to painting remained more or less constant throughout his life. Nor were these two kinds of activities, automatist free association and willful self-awareness, entirely separated from each other. They were reciprocal and often involved alternating between the two kinds of impulses while a picture was being developed. An important notion that emerged from this fluid process of drawing upon unconscious impulses and then “correcting” them was that a picture in principle was not necessarily a fixed and stable object, but something like a by-product: an arena in which the artist acted, and could repeatedly act and react.

Motherwell became aware of this contingent quality of the painting process right at the outset, with his portrait of Maria. He signed and dated the initial state of this painting “14 June 1941” at the upper right, apparently thinking it was then finished. But he reworked the picture over the next couple of months, eventually painting over the June 14 signature and date and signing the picture again—without a date—at the lower left. Right at the beginning of his venture as an artist, he seems to have understood that, for him, a picture was potentially never finished, and if it remained in his possession it could be worked on over and over again, in response to his changing states of being. This Heraclitean attitude, that one can’t step into the same river twice, informed his working process throughout the rest of his life.23

The automatist impulse extended to the way Motherwell gave titles to his pictures, usually after they were completed, in response to a process of free association with their imagery, and also to discourage overtly narrative readings of them. His early paintings contained a Surrealist-inspired blend of abstract forms mixed with suggestions of actual things and figures. As a result, even his most abstract pictures often have some sort of representational overtone, which was frequently enhanced or modified by the titles he gave them. Many of his pictures remained untitled until they left his studio; until then, they were given provisional or “studio titles”—descriptive titles meant to facilitate identification by noting their salient characteristics of form and color. Even after formal titles were assigned, they were sometimes changed, especially if a picture underwent significant revision. “The function of my titles is partly negative,”

Motherwell wrote, “to mark off what can’t be named in the picture.”24 His titles function in various ways. Some direct our attention to a specific aspect of the image, others evoke feelings associated with literary references or allusions to other works of art—both his own and those done by other artists. His titles, like his imagery, are meant to create what he described as an “after-image” in the mind of the viewer, as with Western Air (p47) or The Homely Protestant (fig. 42).25 Such after-images compounded meaning by creating complex networks of references that mix together, in unpredictable and fluid ways, sensations from lived experience, literature, and the subconscious memories of other works of art. Such a strategy has much in common with the dense allusiveness of T. S. Eliot’s poetry, which is openly haunted by imagery from the past, which it uses to both reinforce and resist the main thrust of the poetic line.

Motherwell’s “after-images” function in a similar way, as a means of both resisting and reinforcing the artistic past; of both insisting upon his uniqueness and setting it within a more general historical context. Like Eliot’s use of allusion, this notion of the “after-image” is a symptom of artistic belatedness. Early in the twentieth century, artists such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso had felt that Paul Cézanne and the Post-Impressionists had blocked their way by staking out a new territory and then occupying it completely. In a similar way, for Motherwell and his generation, Matisse and Picasso and other early-twentieth-century modernists seemed to have thoroughly explored all the new paths they had opened, leaving scarce space for future invention. Among the Abstract Expressionist painters, it was Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, and Arshile Gorky who struggled most with this sense of belatedness, because it was they who engaged the European modernists in the most direct and sustained way. The artistic maturity of painters such as Newman, Rothko, and Still, by contrast, was marked by creating a fixed pictorial format or signature image that neutralized the issue of artistic belatedness. Motherwell, de Kooning, and Gorky, on the other hand, became locked in an ongoing struggle with the early moder nists. Each of them, in different but sustained ways, became engaged in a continuous process of both allusion and resistance to the past, and each moved back and forth between figuration and “pure” abstraction in order to confront artistic influences head-on, allowing the “corpses” to show on the battlefield. “The after-image is a key for reading paintings,” Motherwell said in 1957. “There is no key to how good a painting is, but there are keys to what a painting is involved with.” A strong artist, Motherwell asserted, usually has “several after-images together. If one has a strong personality, the after-images ipso facto get transformed. The only way to be original is through intensity. . . . This is what art is for—to enact things as intensely as we feel them.”26

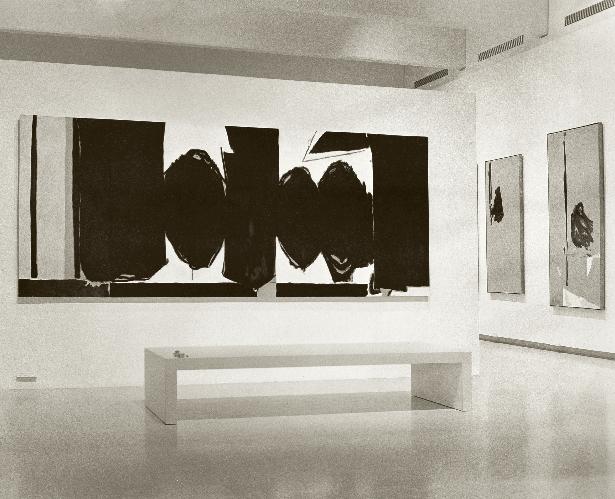

Since Motherwell tried as much as possible to work without preconceived subject matter, to generate imagery and then afterward make verbal associations that would illuminate aspects of that imagery, the act of titling was an extension of the painting process itself, based on a similar mixture of instinctive free association and willfulness. In one striking instance of how this process could operate, he described how after the death of his close friend the sculptor David Smith, he had painted The Forge (p350) as a deliberate memorial to Smith, but had not been satisfied with it. A few years later, when he finished a large, dark Open painting that initially had no association with a specific subject, he realized that that was the painting he had really meant to paint in memory of Smith—but only after the painting was done. Accordingly, he gave it the title Open No. 121: Bolton Landing Elegy (p504), referring to Smith’s studio at Bolton Landing near Lake George. “Commissions, even self-commissions,” he concluded, “work less well than working directly and then discovering what one associates the work with.”27 Motherwell’s desire to balance willfulness and spontaneity is often built right into his painting process. One of the great surprises that emerged in the course of putting together this catalogue raisonné was the degree to which Motherwell went back and “corrected” the spontaneous elements in his works. This is most readily apparent in large, monumental paintings, such as Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 70 (p220), in which he not only painted out a number of the black splash marks on the white ground, but also added splash marks as he modified the balances between the blacks and whites. The balance he sought was more than formal; it also involved a calibration of the visual signs for spontaneity and deliberation. He did something similar in small paintings, even those on paper, such as The Black Sun (fig. 2), which he worked on over a period of several months, painting out some of the black splatter marks while leaving others, and extending the massive black form to the right edge of the picture to give it a monumental effect despite its relatively small physical size. When he made such changes, moreover, Motherwell usually made the modification process itself part of the imagery of the picture; the painted-over blacks remain visible under the white overpainting, and the areas of white overpainting are given enough body to make their brushy presence felt as forms that have been laid in independently of their covering function.

In controlling the signs of spontaneity and deliberation in his paintings, Motherwell was well aware that he was working within a tradition of expressive brushwork that went back to the nineteenth-century modernists. The emphasis that the Impressionists, for example, had placed on the appearance of spontaneity and on working from direct experience was an important part of their claim to authenticity. Certain kinds of mark-making—such as vigorously rendered brushstrokes, drips, and scumbles—were understood to act as signs for improvisation and strong feeling, even if they were in fact executed deliberately to look as if they were spontaneous, as they often were by the Impressionists. Such marks came to stand for an intuitive response to nature, associated during the nineteenth century with the artist’s new role as someone who bears witness to contemporary realities, and with an ethical position in which spontaneity was equated with the virtues of simplicity, sincerity,

and authenticity. These expressive means were transformed into pictorial conventions by early-twentiethcentury artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Matisse, and Joan Miró, each of whom developed a rich pictor ial syntax from the language of apparent facture and expressively visible brushwork that had been created dur ing the previous century.28

The constant tension in Motherwell’s work between spontaneity and calculation—and the different kinds of feeling that they created—interested him throughout his life. (It was like an extension of his longtime involvement in psychoanalysis, which began at a time of crisis after the breakup of his first marriage and continued until his death.) Discussing the variety of his imagery with an interviewer in 1971, Motherwell explained what he thought was one of the impulses behind exploring different kinds of imagery: “I think what happens is that when you hit something that seems a true expression of one’s self, it’s mysterious to one’s self why that particular configuration rather than another one is, and one begins to investigate, mucking around, trying it in different ways, trying to find what one’s own essence is and worry it and worry it and worry it.”29

Throughout his career, Motherwell was aware of treating different kinds of themes in different stylistic modes, and equally aware that his doing so was different from how his colleagues worked.30 As early as 1946, in a letter to Dorothy Miller, curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, he noted that his engagement with “several themes, instead of one, as with most painters, in both subject and formal conception” was confusing to most people. But, he told Miller, who was selecting works for the Fourteen Americans exhibition being organized by the museum, those themes had interested him for a long time, and at different times during a given year he was apt to work on all of them. Since each theme, he wrote, would be clear only if all the pictures that dealt with it were grouped together, he gave her examples of the kinds of pictures that constituted each of the four main groups. The first group, he wrote, was “based on relatively automatic means” and included nearly all of his drawings and watercolors, as well as Joy of Living (see fig. 20) and other collages. The second group consisted of what he called “pure abstractions,” such as Wall Painting with Stripes (see fig. 30). The third group was composed of what he described as “political” works, and characterized (referring to Francisco de Goya) as “a kind of ‘disasters’ series,” which included the watercolors in the Three Personages Shot series (see fig. 9) and works such as Pancho Villa, Dead and Alive (see fig. 23) and The Spanish Prison (Window) (see fig. 8), as well as a Walls of Europe series that was still in progress. The fourth group he described as composed of “intimate pictures,” in the tradition of French interior, figure, and still life paintings, such as Head (p21) and Small Personage (p32). He conceded that these divisions were arbitrary, that there was a certain amount of overlapping between them, and that he could not explain why at a given time he worked “on one rather than another.”31

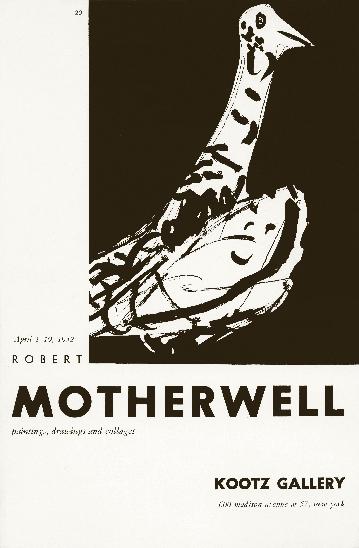

A few years later, in the catalogue for his 1950 solo exhibition at the Samuel M. Kootz Gallery—the first exhibition in which he showed the Elegy paintings as a named group—Motherwell divided his work into four different categories, “in order to point out certain subtle differences among them, a difference in ‘meaning’ that accounts for certain differences in form.” These four categories

were listed as follows: Elegies (to the Spanish Republic), which he characterized as “funeral pictures, laments, dirges, elegies—barbaric and austere”; Capriccios, which he related to the musical capriccio, “a composition in a more or less free form”; Wall Paintings, conceived as different from easel paintings, as “enhancements of a wall”; and “Recent Drawings, 1950,” which included nudes as well as themes from the previous three categories.32

Around the same time, perhaps as a draft for the Kootz Gallery catalogue statement, Motherwell made an important distinction between feeling and emotion, which provides insight into what he seems to have perceived as a unifying principle behind his different kinds of pictures—that they transcend emotion and participate in the world of feeling. Feelings, he wrote, “constitute one’s oneness with the world” and are always objective, “the felt quality of things in perception.” Emotion, by contrast, “is something already in one,” such as anguish. “Pure feeling is invariably harmonious,” he continued, “because it is, in being their felt quality, a oneness with the things of the world. Emotion is usually around the concept of anguish or dread, and separates one from the world, because the emotion gets in the way of feeling the world.”33 The creation of the work of art, he suggests, involves transcending mere emotion and expressing a state of feeling or harmony. (“I think that one’s art is just one’s effort to wed oneself to the universe, to unify oneself through union,” he wrote the following year.)34

In 1966, the year after Motherwell had a major retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, the planning and display of which had given him unprecedented contact with the trajectory of his career, he discussed what he called a number of “turning points” in his work in a letter to the English art historian Joseph Hodin. Now he divided his production into eleven categories, “some of which are capable of being illustrated by many pictures,” which he listed as follows, sometimes giving specific works as examples: 1. collage, as in Collage in Yellow and White, with Torn Elements (c52); 2. “working in close tonality over an essentially single color field,” as in The Homely Protestant (p85); 3. the “Spanish Elegy” series; 4. “the use of ‘automatic’ drawing,” as in Africa (p338); 5. the “use of ‘accidental’ massing of shapes,” as in Chi Ama, Crede (p224); 6. “a white canvas that tends [to] be almost wholly covered over by black,” as in the Iberia paintings; 7. “arbitrary figure constructs (in Lord Russell’s sense of the latter word),” as in The Poet (c42) or Two Figures with Cerulean Blue Stripe (p208); 8. “the emphasis on violent rhythm,” as in Black on White (p219) or the Beside the Sea series; 9. “ ‘line’ or ‘contour’ drawing with a pen,” of which there were “innumerable examples”; 10. “tremendous emphasis on stripes—many examples, from 1941 on”; and 11. “conceiving a picture as a wall,” which he dates from 1947 on, citing the recent New England Elegy (p366). If he had to choose favorites, Motherwell wrote, he “would choose aspect #3, #4, and either #5 or #6 or #11. Because they perhaps represent best my personal contribution as a painter to l’art moderne.”35

Around the time of Motherwell’s 1972 collage exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, his production of collages increased, and he became more absorbed by the differences between the ways his work in different mediums brought out various kinds of expression. When he moved to Greenwich, Connecticut, in 1971, after thirty years in New York, he was able to construct different kinds of studio space and to set up his own printing presses. By the mid-1970s, printmaking had become an important part of his production, in terms of both the time and effort he spent on it and the income it produced.

“Print-making is my hobby, my mistress,” he wrote, affirming his love for paper and for the collaborative process it involved, so different from the solitude of painting. Another important difference between printmaking and painting, he asserted, was that in printmaking, although a great amount of effort goes into making the image, once the edition is printed, no more revisions are possible. “When the edition is finally o.k., and goes to press and you see the first fresh print, it is with ecstasy. All struggle has vanished. There is a virgin birth, fresh and perfect, like Venus arising from the sea. Good prints, properly taken care of, never lose this virgin beauty, no more than medieval stained glass.”36 At the time, the definitive quality of the editioned print represented a kind of liberation. Here, at last, was a medium that would seem to defy the whole idea of revision. (But, as this catalogue raisonné makes clear, even prints did not escape Motherwell’s compulsive restlessness. During the last years of his life, he “revised” them, so to speak, by tearing up edition proofs and using them as the raw material for collages.)

By 1974, Motherwell was painting and making collages in separate studios. In 1977 he described the advantages of this setup in a letter to the French critic Guy Scarpetta. The diverse spaces, he wrote, “help by separating my art problems—if one problem puzzles me, I can leave the work in progress in situ undisturbed in its own ambience, and try my hand in another studio; and in constantly passing through the various studios, I sometimes unexpectedly see out of the corner of my eye the solution to an older problem, a solution that may have come from so completely focusing on another problem in another studio, that I can see the older problem more detachedly, or conversely, am perhaps so psychologically free that the solution is able to rapidly rise to the surface from my unconscious.”37

In this same letter, Motherwell gave perhaps his most concise description of how the various mediums he used served his goals of expression in general. Of all his activities, he said, painting was the one that gave him the most trouble. Since the underlying subject of his painting was “the centre of my being,” he wrote, “there is evidently more tension, more self-consciousness, more desperation, more absolute standards, more self-induced pressure, more anxiety.” When he reached a state of psychological or physical exhaustion with his painting, he said, he often turned to collage. With painting, the artist was always faced initially by the blank canvas, the kind of metaphysical void that the blank sheet of paper presented to the poet Stéphane Mallarmé. But in Motherwell’s collage studio, he told Scarpetta, there were hundreds of pieces of different kinds of paper, and these allowed him to begin “playing with the papers upon the panels.”

By the early 1980s, Motherwell had contemplated the diversity of his production for over forty years and had written extensively about it over nearly that whole time. Yet this did not prevent him from being surprised by certain aspects of his work when, in 1982, he helped choose the pictures for the last comprehensive retrospective exhibition of his work that he would live to see. In the process of selection, he noted, he had been struck by what he called the different spatial concepts in his paintings.38 “I have been conscious,” he said, “of the Oriental concept of a painting representing a void, and that anything that happens on a painting plane is happening against an ultimate, metaphysical void.” Some of his pictures, he said, such as In Beige with Charcoal No. 4 (see fig. 121) and A View No. 1 (p182), were conceived in that way; but others were conceived of as walls, such as Jour La Maison, Nuit La Rue (fig. 61), some of the Elegy paintings, and the ones that were literally called Wall Paintings. Others, he remarked, were