Digital Thinking:

or Thinking as Handwork

Dean Cooke Rare Books Ltd

Digital Thinking: or Thinking as Handwork

In manuscript studies, material features such as binding, spatial arrangement, signs of use and wear are often treated as sources of contextual, historical or bibliographical insight. This project broadens the frame, asking: how do these extra-textual features relate to thinking? Can the physical form of a manuscript extend, influence, or shape cognition; and if it can, are these features manifested in the artefact? Our Elizabethan legal pocketbook (item 7) shows this clearly: its structure funnels from political philosophy to courtroom scripts, moving thought from abstraction into procedural detail. The careful sequencing and pocket format meant that the law was not only recorded, but cognitively rehearsed in the very act of consulting it. To understand how material form may reflect or constitute thinking, we must begin with the assumption that physical features matter and matter differently than the text alone. As such, these physical features are not merely artefactual details; they are cognitive cues to how manuscripts can be handled as tools for thought.

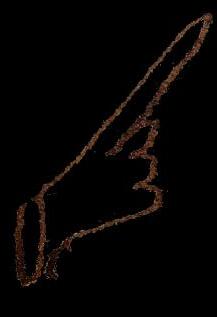

Writing takes the particular form it does because of the dextrous combination of fingers with opposable thumbs, enabling some uniquely human cognitive capacities. Because the mind and hand co-evolved, thought itself is, in many ways, a handwork. Digital Thinking explores how the material and structural features of books and manuscripts beyond their textual content can reflect or even constitute the cognitive processes of their users. Our catalogue brings together examples across this spectrum: some manuscripts serve primarily as records or mirrors of mental work (reflective), while others appear to actively participate in thought itself (formative). By comparing these interactions, this catalogue investigates not just what people thought, but how their thoughts and other mental contents were realised through fingers, thumbs, hands, and expanded through tools and other physical extensions of the body.

Digital Thinking begins with the premise that physical manuscripts (artefacts written or made by hand) contain forms of meaning that digital copies (a series of digits 1 and 0) frequently flatten or obscure. A digital record typically gives no indication or obscures size, weight, texture, or tactile interaction all features that shape how a book or manuscript was used, valued, or navigated. A pocket-sized book, for example, implies portability and habitual consultation, while a large-format volume may indicate reference, ceremony, or display. The Harbin Pocketbook (item 4) exemplifies this: its compact wallet form made it an intimate companion, where fleeting conversations and anecdotes were caught on the fly; its portability shaped the kinds of thought it preserved.

To guide our analysis, we make the following distinction:

Reflective manuscripts, in which extra-textual features layout, structure, annotations, etc reflect cognitive processes. The estate maps, inventories, and aphorisms in the Warly Archive (item 15), for instance, trace Lee Warly’s sensibility of order, filial duty, and prudence, without transforming his reasoning. The three volumes relating to Lady Pakington (item 9) - a printed book, a manuscript miscellany, and a handmade pamphlet –reflect how individuals and groups express their thoughts in public, social, and private spheres, and captures these contrasting expressions in tangible forms. These manuscripts are valuable because they show us how a person thought, learned, or remembered, but may not themselves influence or structure that thinking.

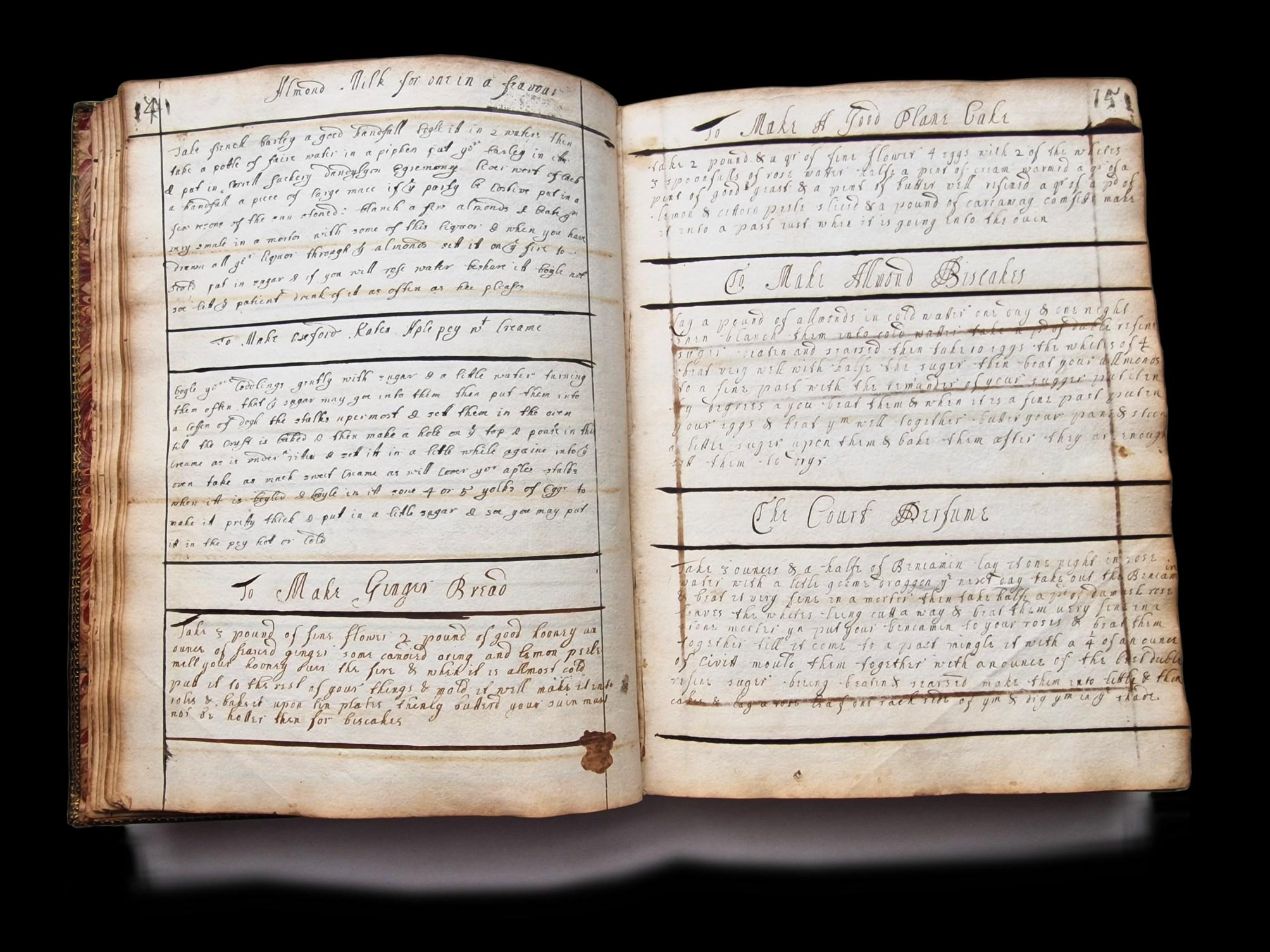

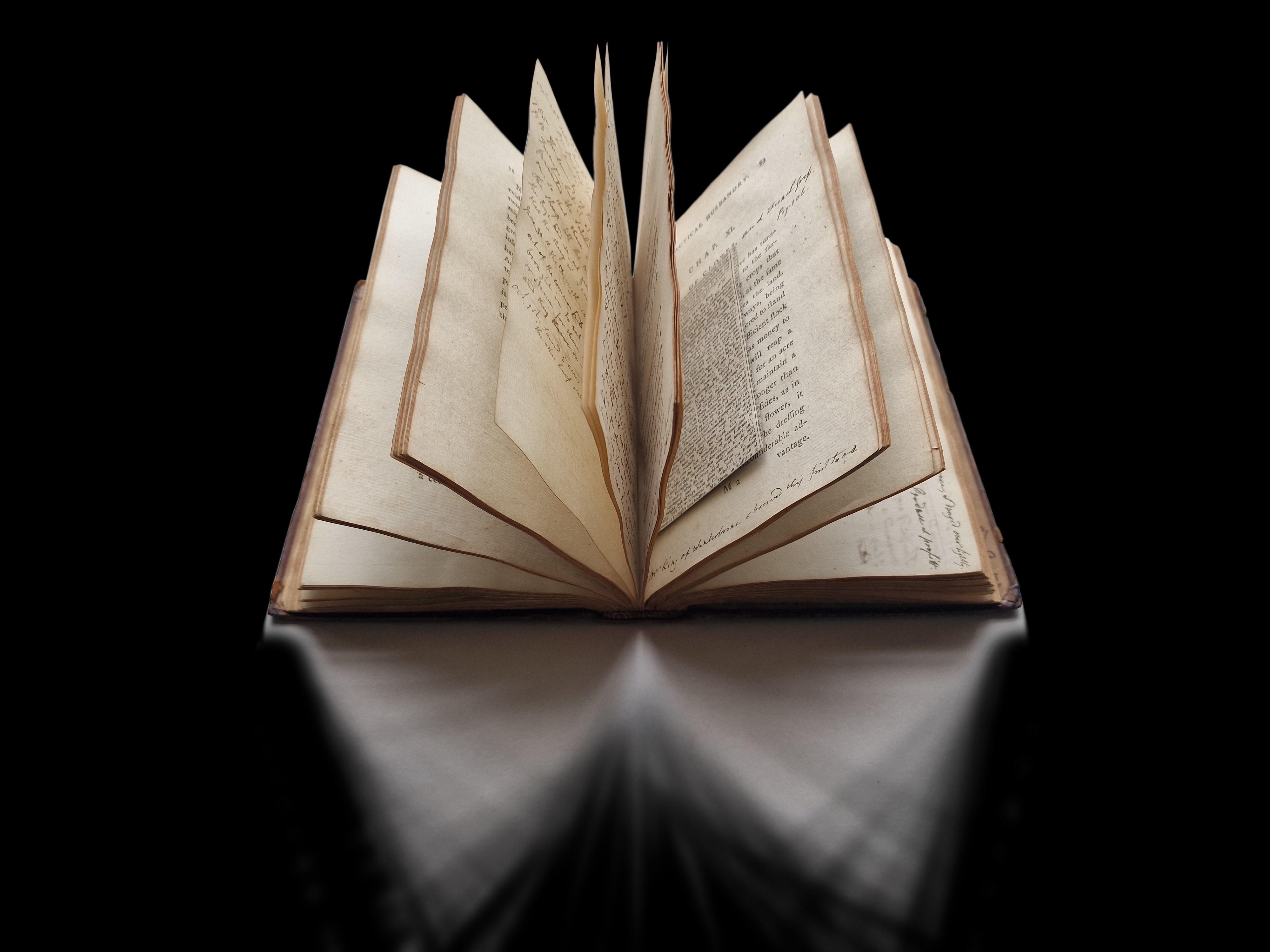

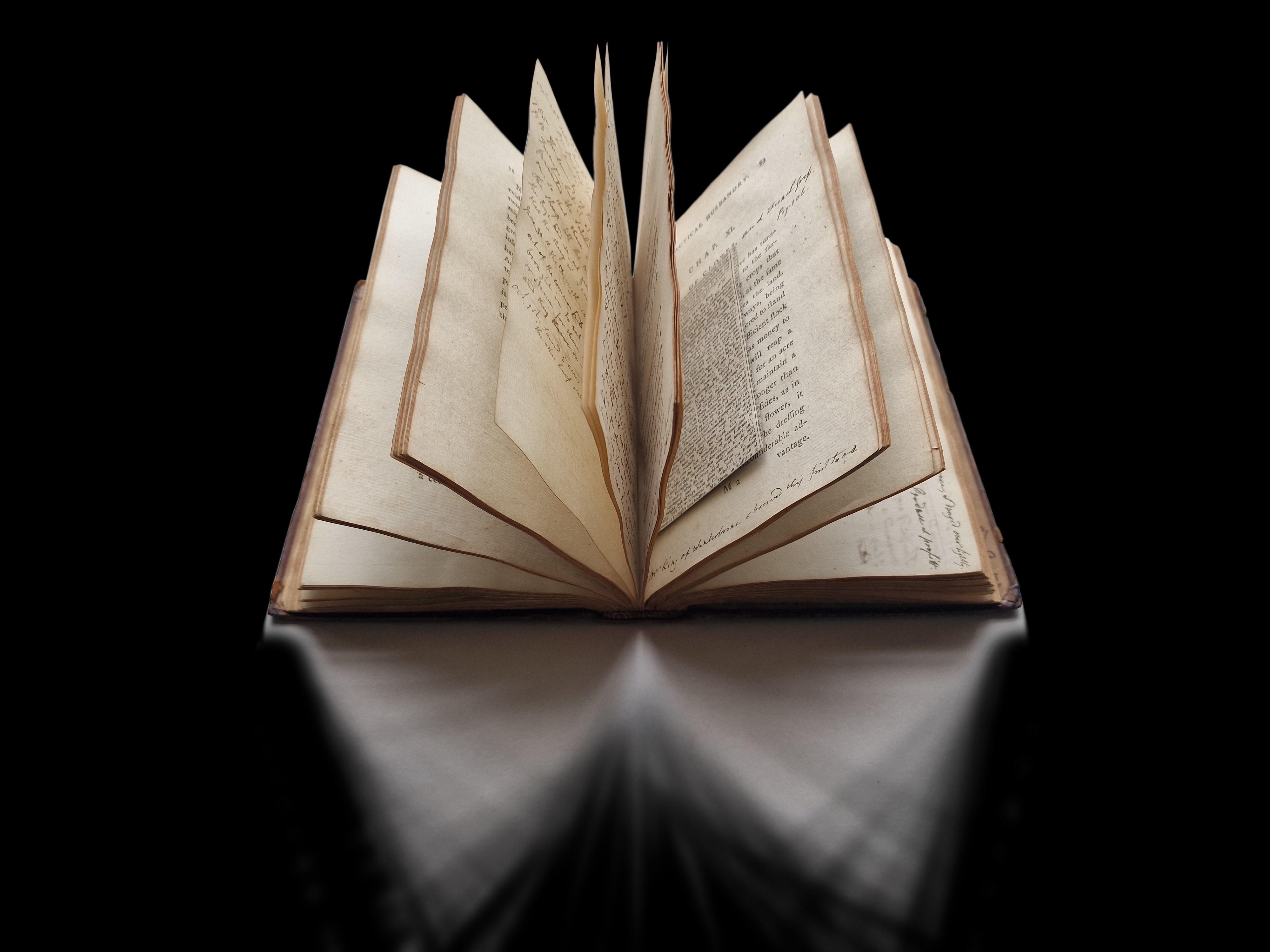

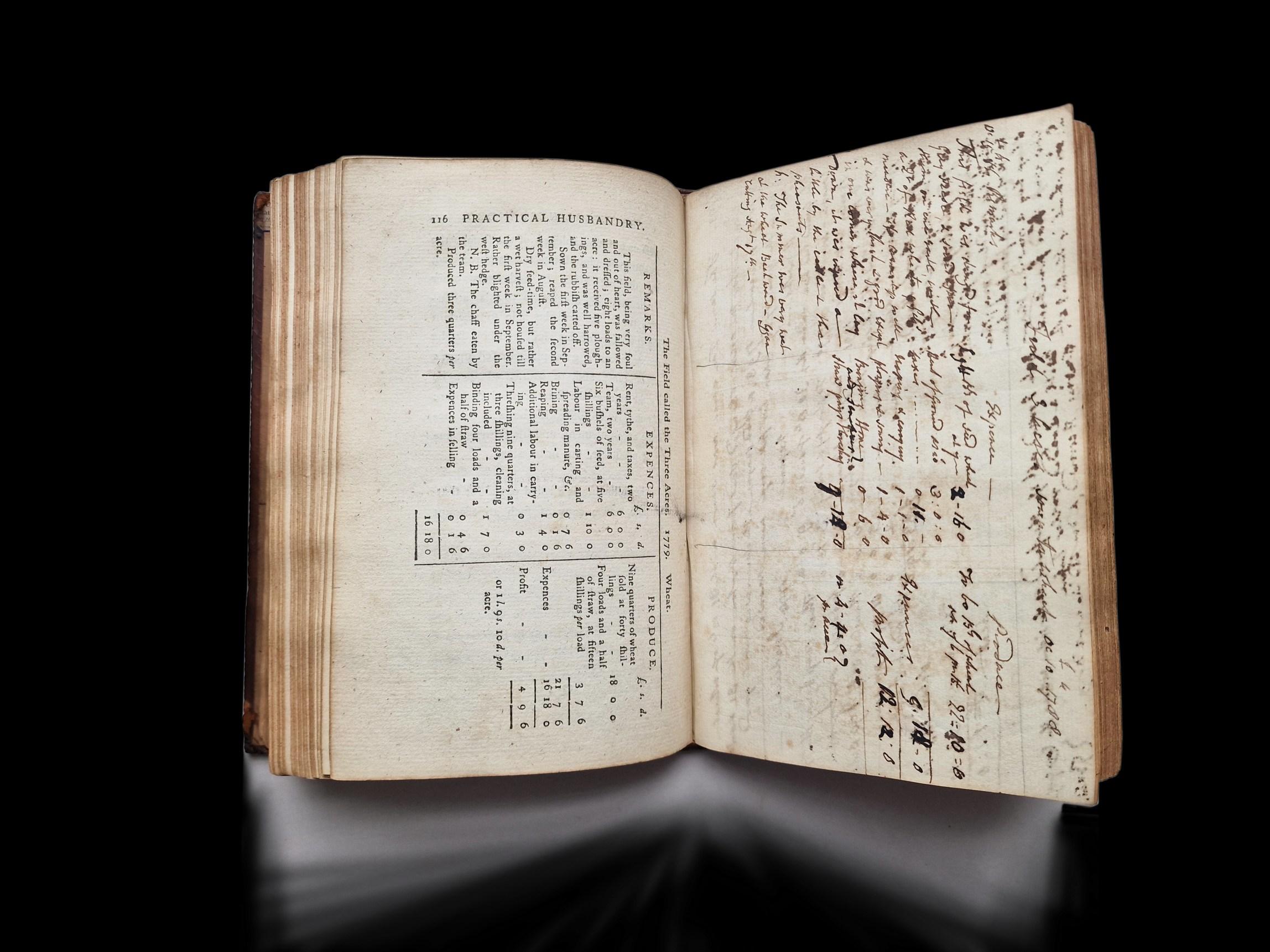

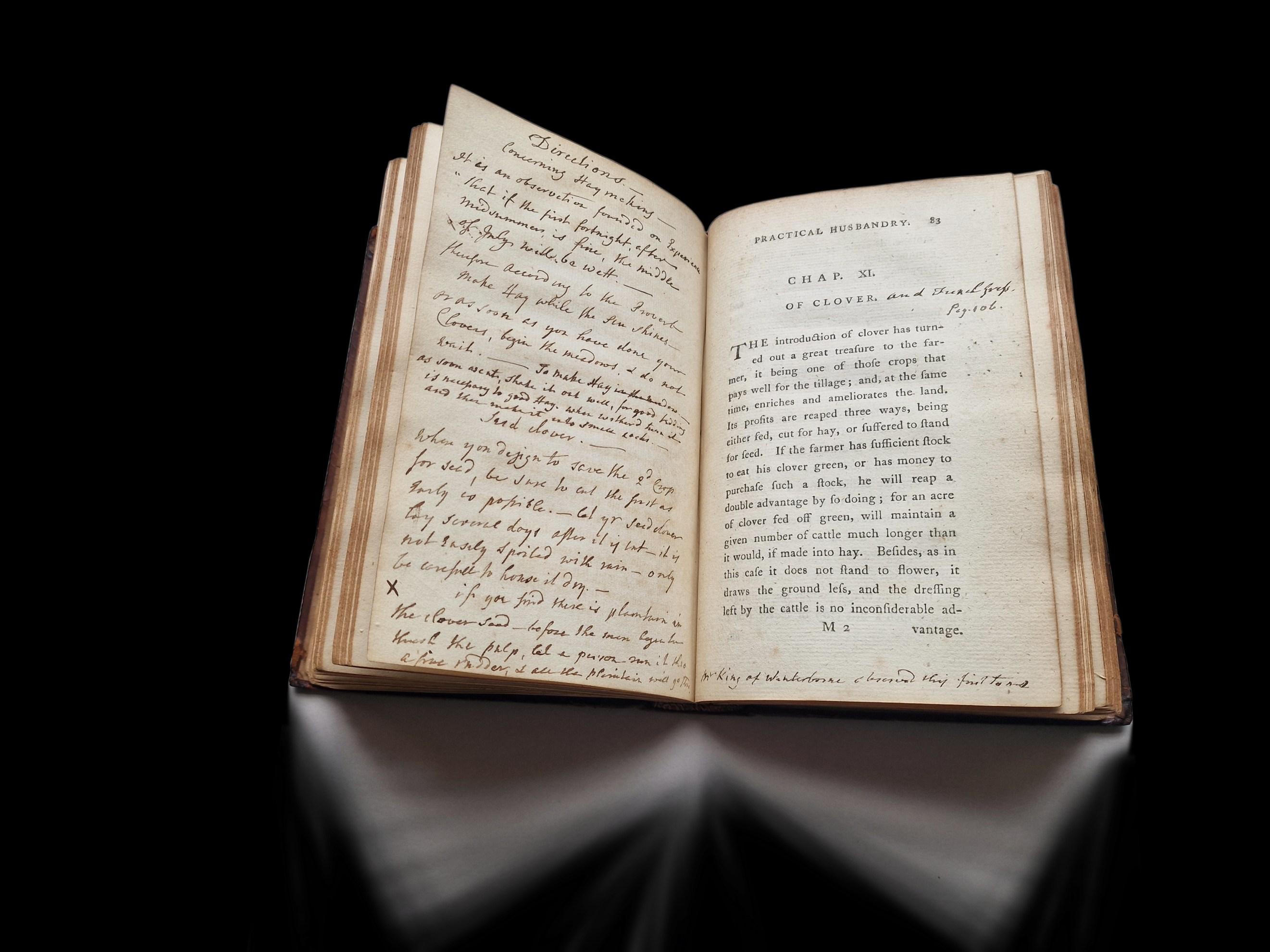

Formative manuscripts, in which extra-textual features compose, scaffold, or transform thought. John Harris’s augmented Practical Husbandry (item 14) is exemplary: writing, pasting, and tabulating, transforms a standard printed text into an active farming companion. John Woods’s System of Arithmetic and the Mathematics (item 1) compiles fragments of printed texts, hand-drawn diagrams, fold-outs, and hand-coloured borders are re-ordered into a personal pedagogical tool. Its recursive, non-linear structure embodies cognition in action. Anne Chester’s Household Receipt Book (item 2) shows how indexing, attributions, and marginal annotations extended memory and scaffolded household reasoning across decades. The structure or visual form of these manuscripts actively enables reasoning, synthesis, or planning.

These categories are not mutually exclusive. A manuscript that constitutes thought will also reflect it, but not all reflective features are formative. Moreover, many manuscripts hover between the two. Household manuscripts, in particular, exemplify this space. The multiple hands, pinned-in slips, and repeated recipes of the late 18th-century Culinary Manuscript (item 10) records communal practice while also structuring the rhythms of domestic life with iterative experimentation; and Catherine Reay’s Household Folio (item 8) knits together recipes, remedies, and attributions, mapping a network of schoolteachers, physicians, and mayors. This reflects social knowledge but, in its careful titling and “experienced” endorsements, also enacts authority and judgment.

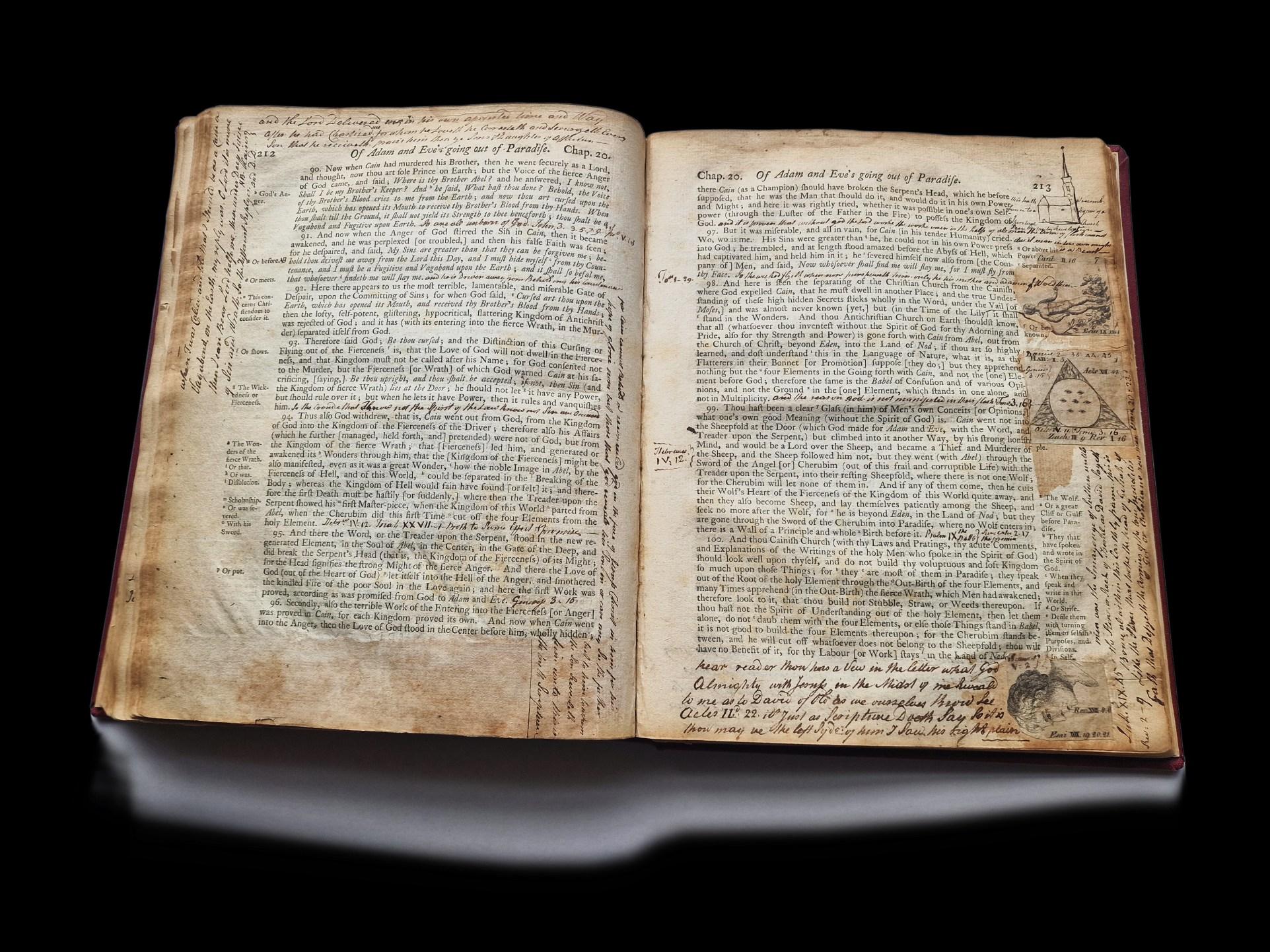

Of course, not all manuscripts are reflective in their extra-textual features; what interests us is the threshold at which form becomes function when structure ceases to be illustrative and starts to be instrumental. David Dunlop’s heavily annotated copy of Jakob Boehme’s Works (item 5) illustrates this liminal space. While the printed volumes reflect Boehme’s visionary theology, Dunlop’s dense mystical marginalia go further, documenting the creation of a “new man”, the persona “Davie Delope”, through the act of annotation itself. Here, reading and writing constitute the creation of a spiritual identity.

We approach this framework with caution. Not every visually engaging or structurally complex manuscript is necessarily formative or strongly reflective, and we are mindful of the risk of over-interpretation. Material features can tempt us toward imaginative readings, and it is important to resist fetishising manuscripts or attributing transformative cognitive effects where none exist. Instead, we focus on instances where the extra-textual features of a manuscript show signs of use to support, organise, or extend cognitive work.

We are conscious of Korzybski’s assertion that “A map is not the territory it represents, but, if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness”.† But a map can reflect the thought processes of the cartographer and potentially influence how they came to understand the territory they were exploring. Manuscripts, in this light, may offer similar cognitive understandings.

This framework encourages close, comparative attention to the physicality of thinking evident in artefacts. By broadening our attention from what manuscripts say (textually) to how they think (manifest meaning), Digital Thinking offers a perspective on the embodied nature of thoughts and actions. The manuscripts we present spanning household recipes, estate maps and accounts, mystical treatises, legal pocketbooks, and more demonstrate the range of ways in which hands, tools, and materials do not merely preserve cognition, but often participate in it.

† Korzybski, Alfred. Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics. (1933). A similar idea is comically explored in Lewis Carroll’s Sylvie and Bruno Concluded. (1889).

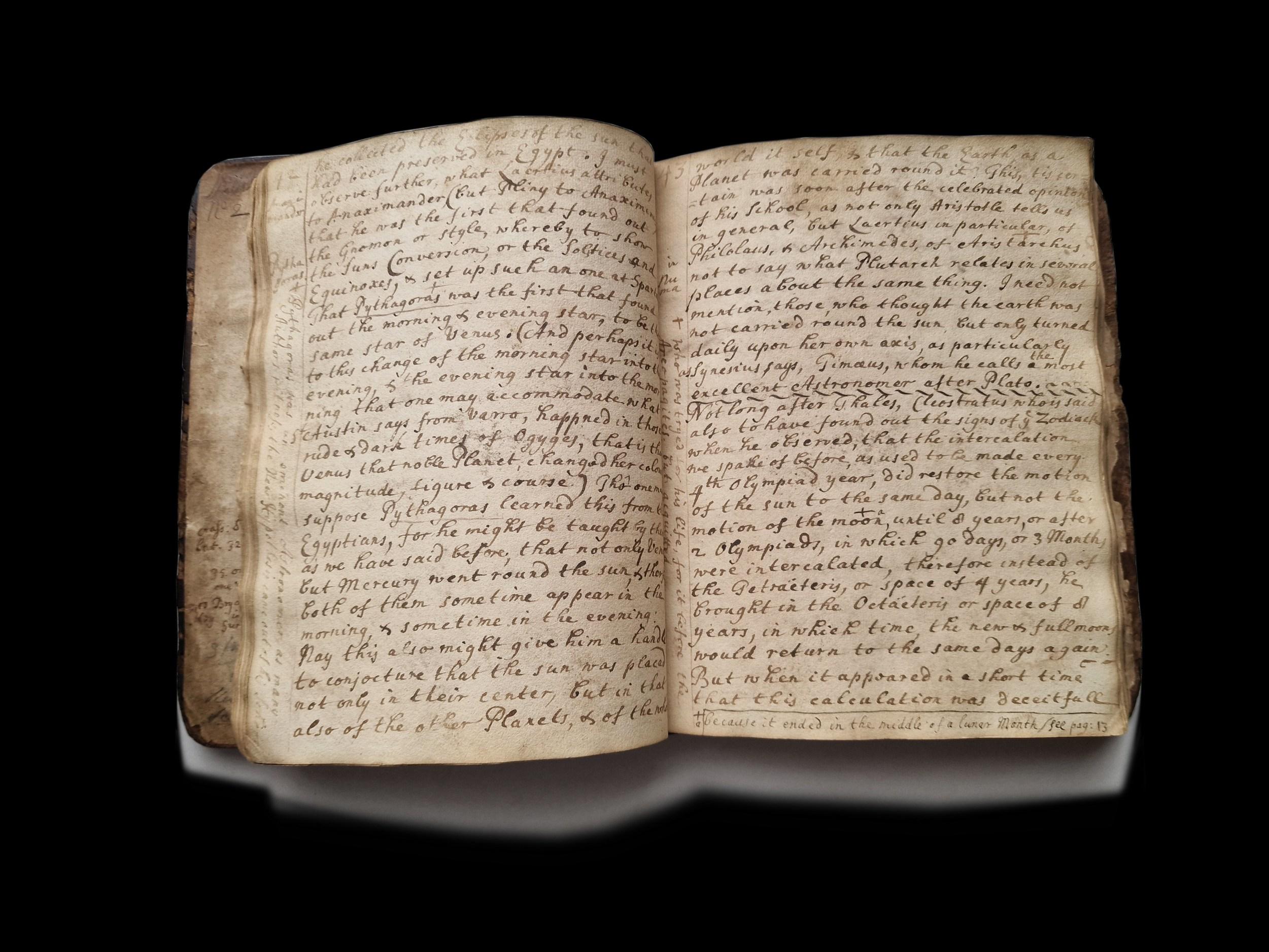

1. CUTTING EDGE

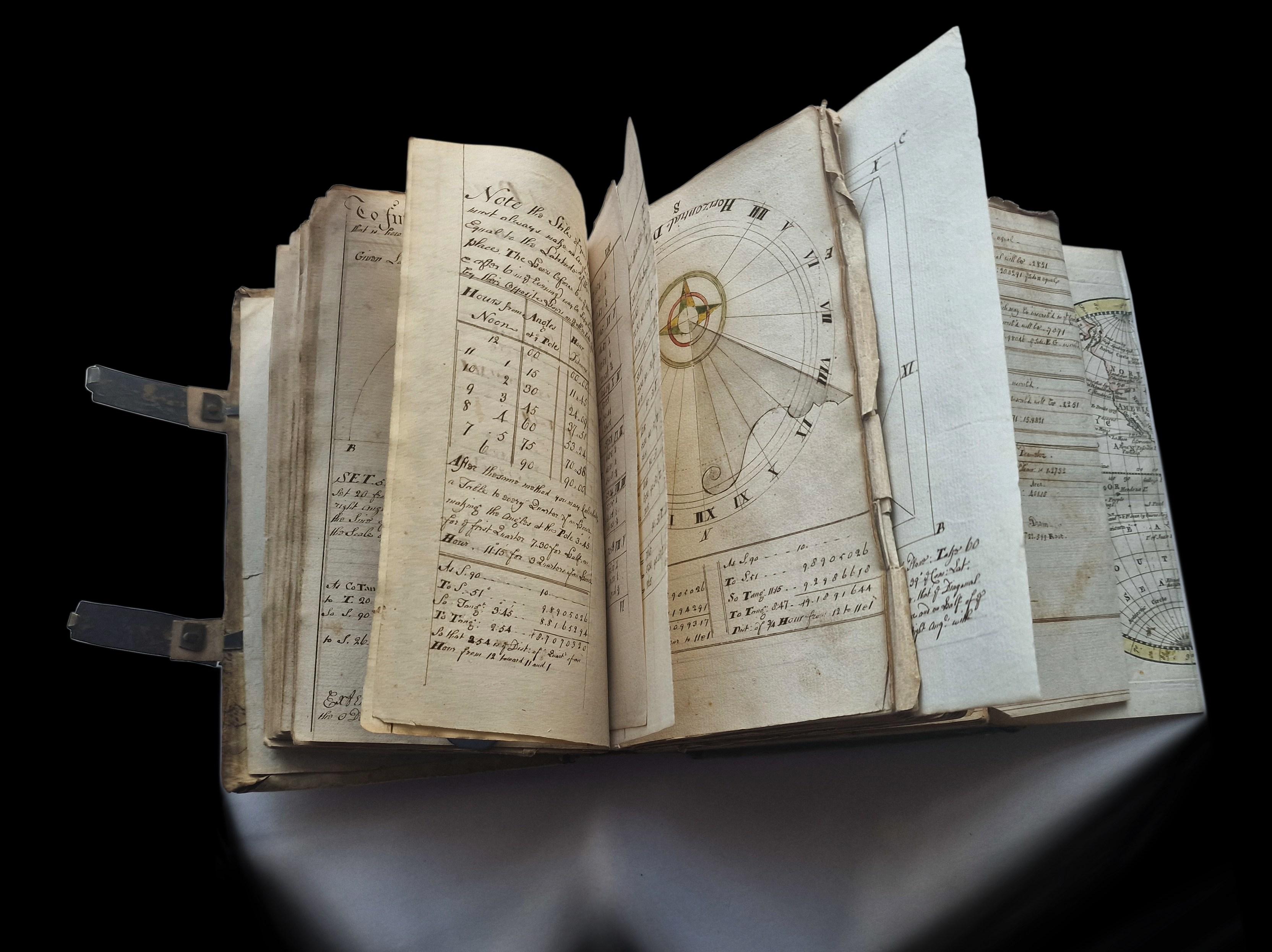

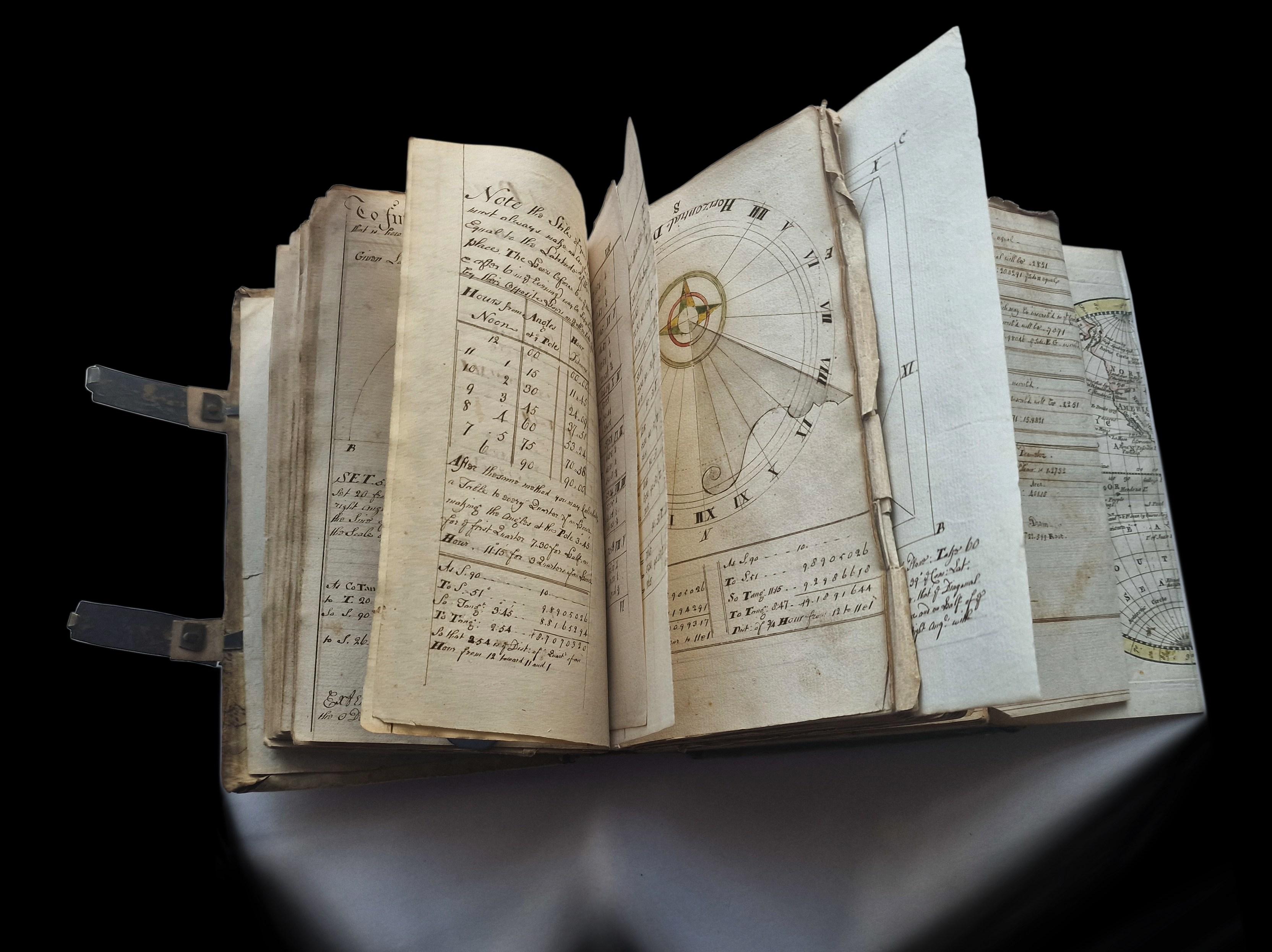

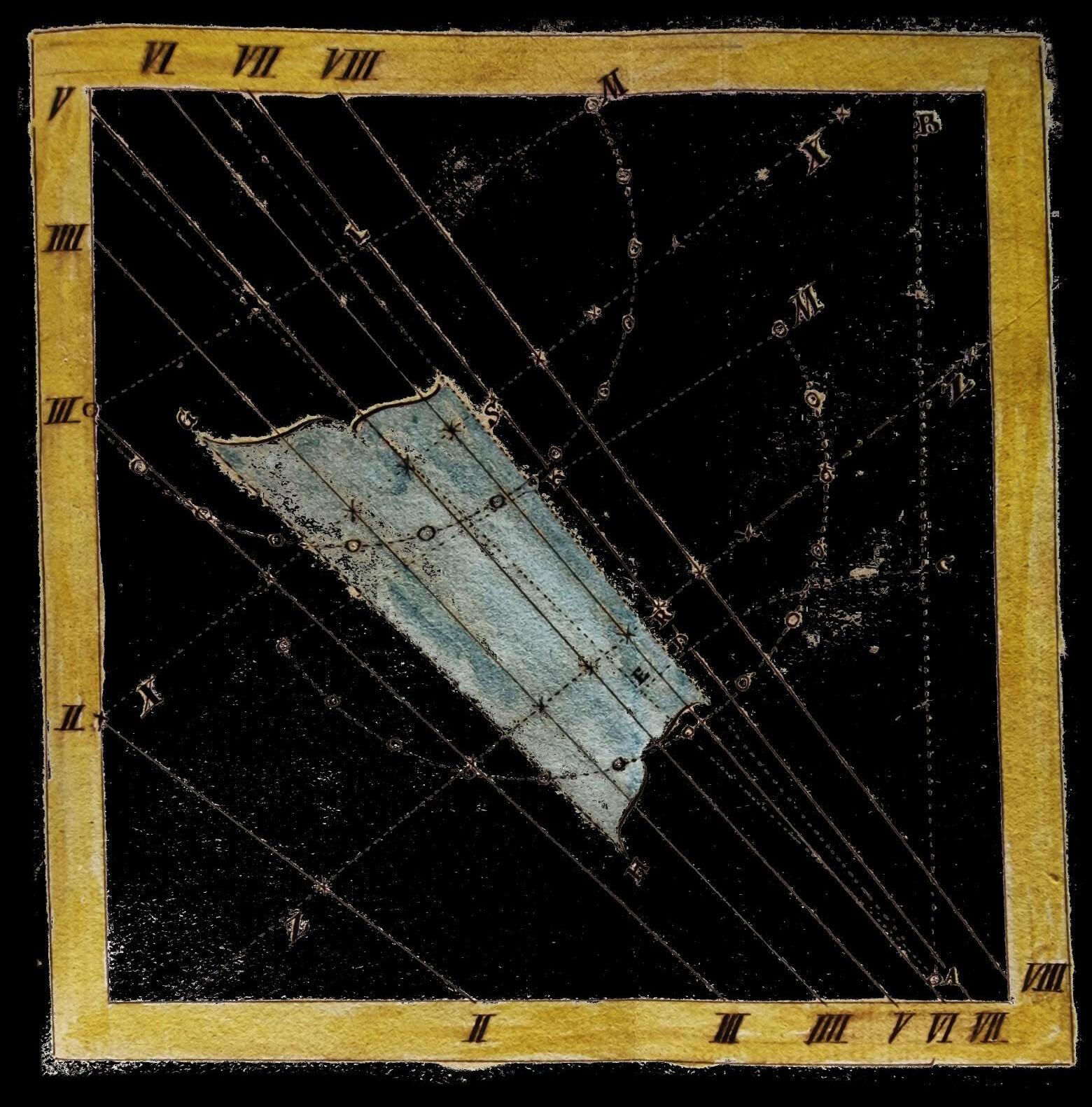

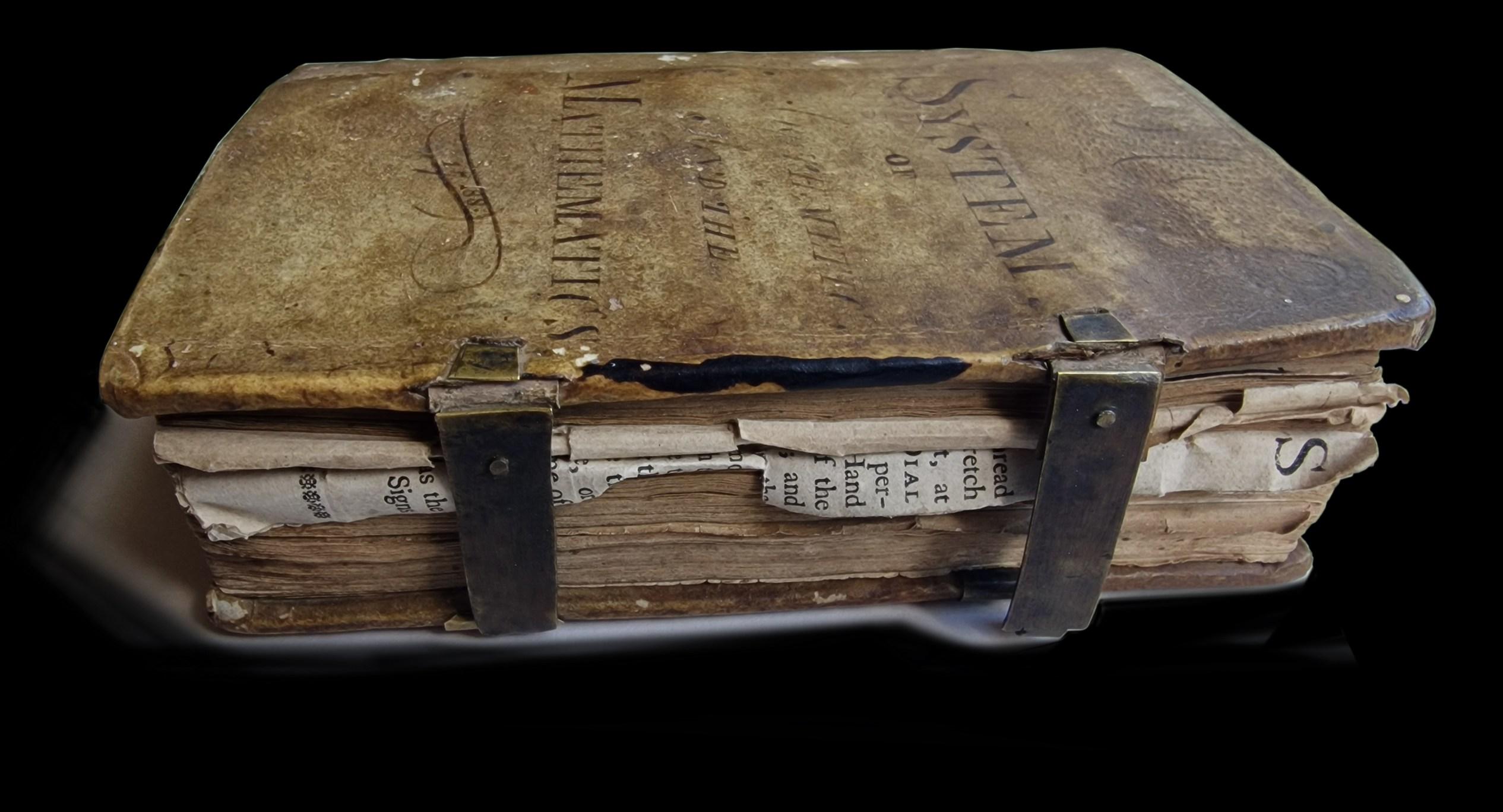

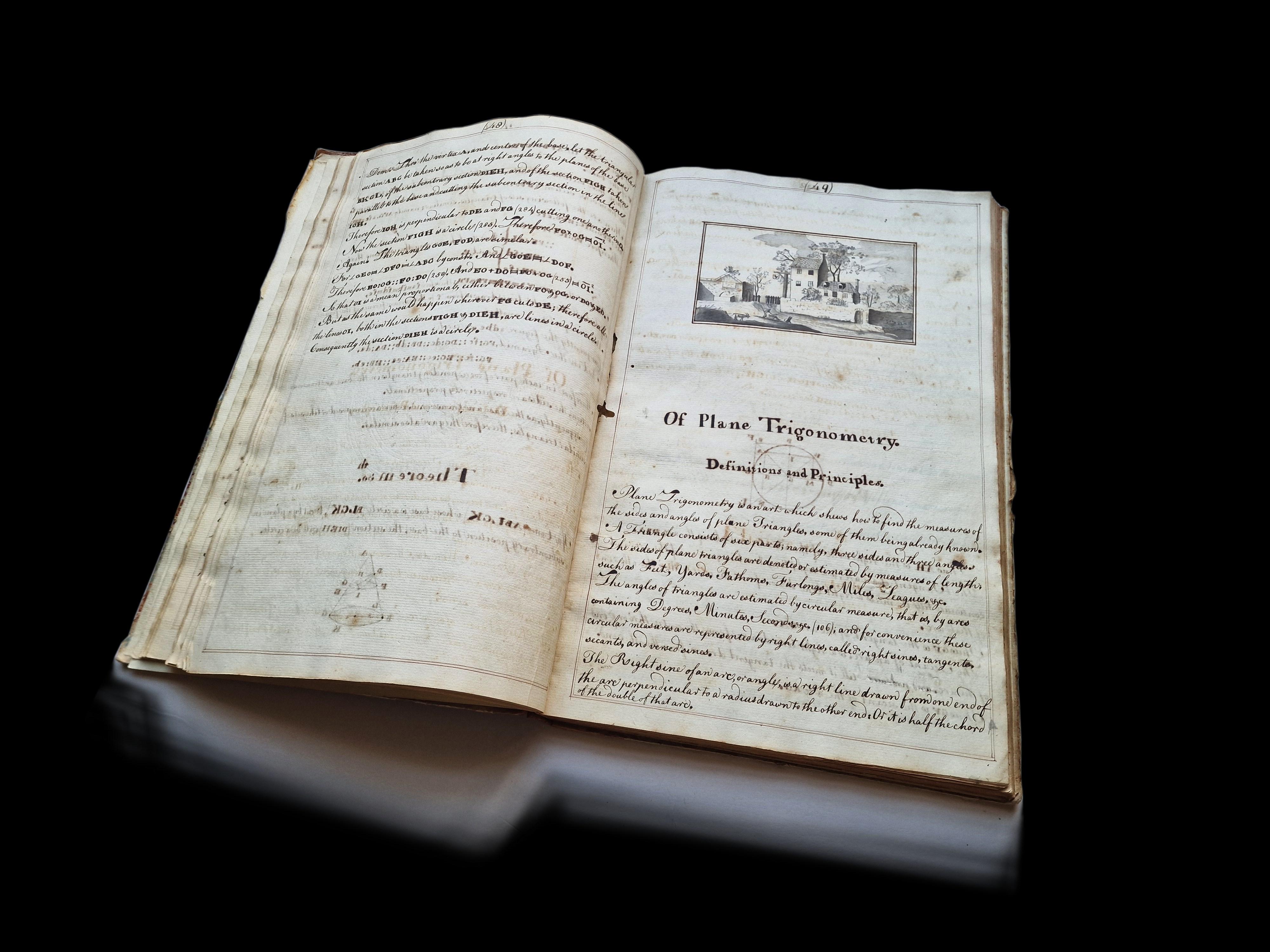

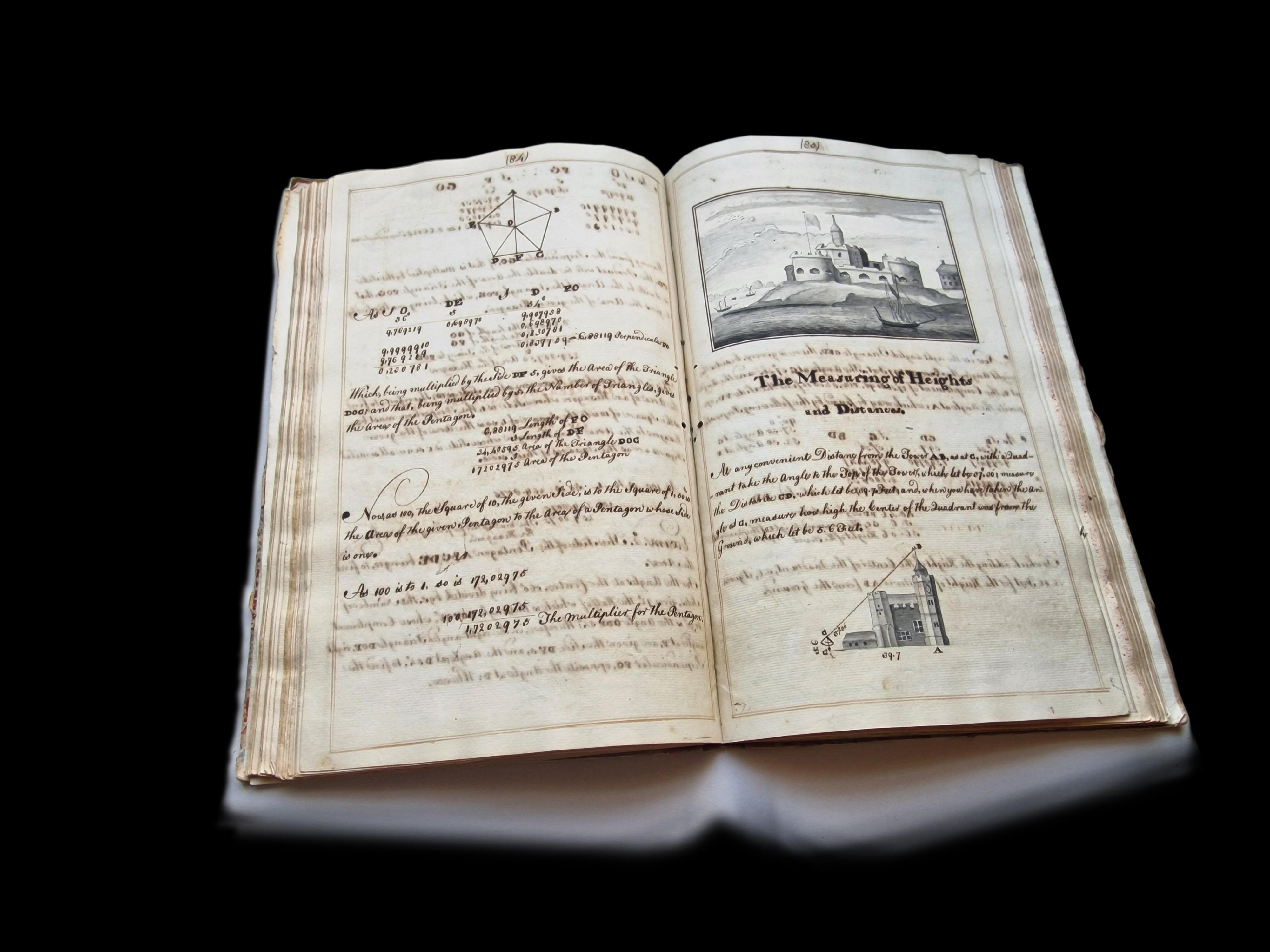

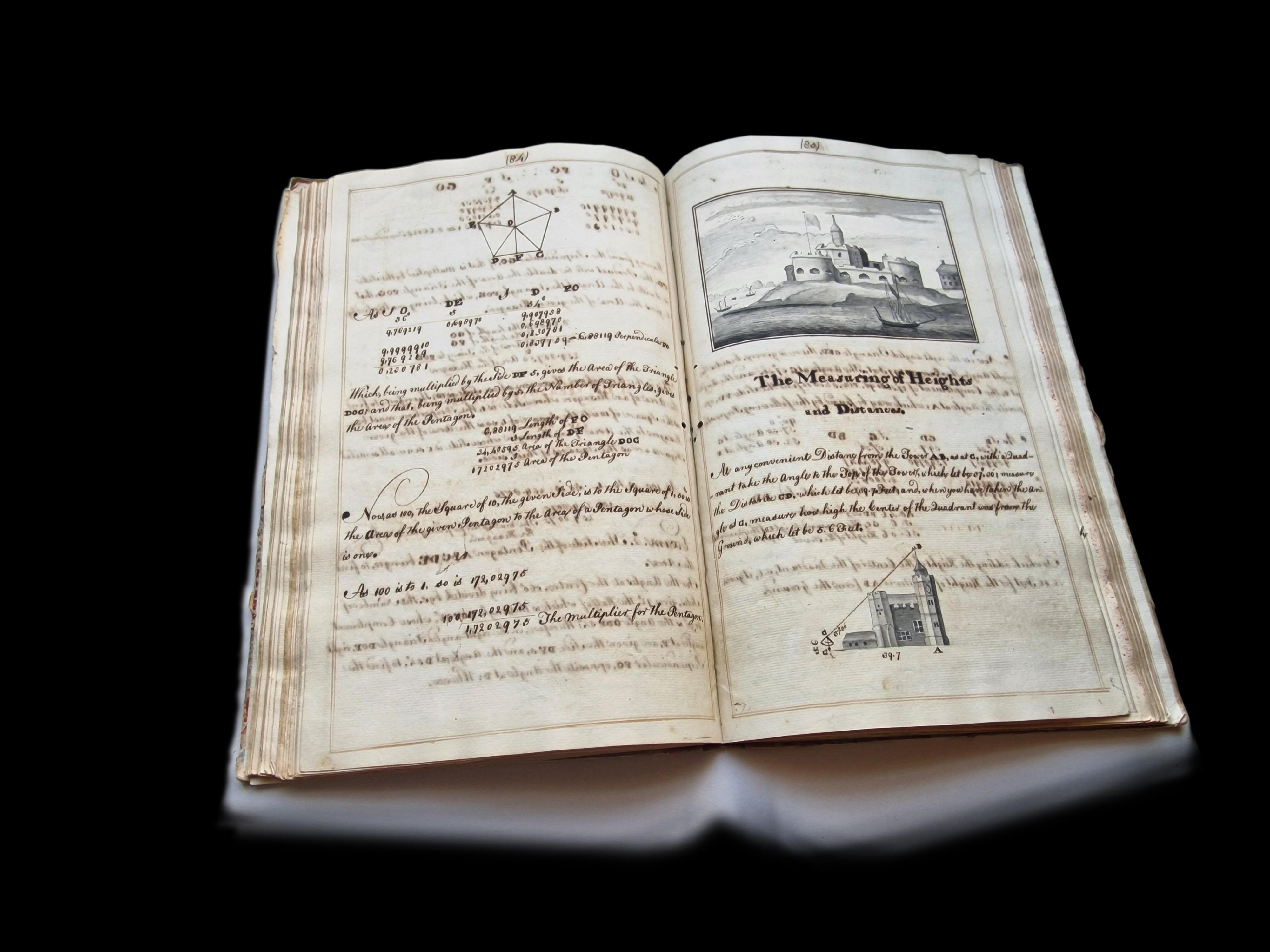

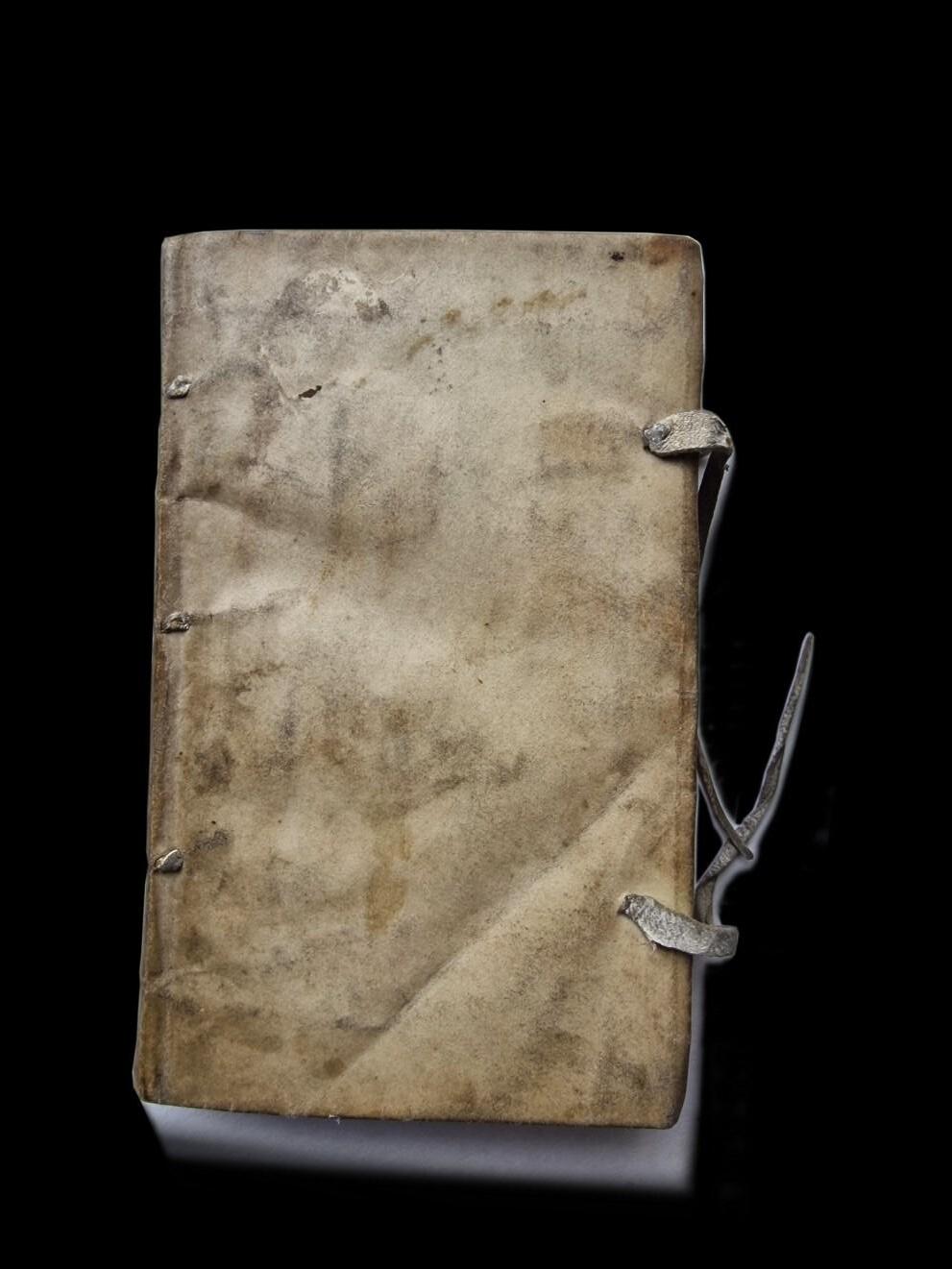

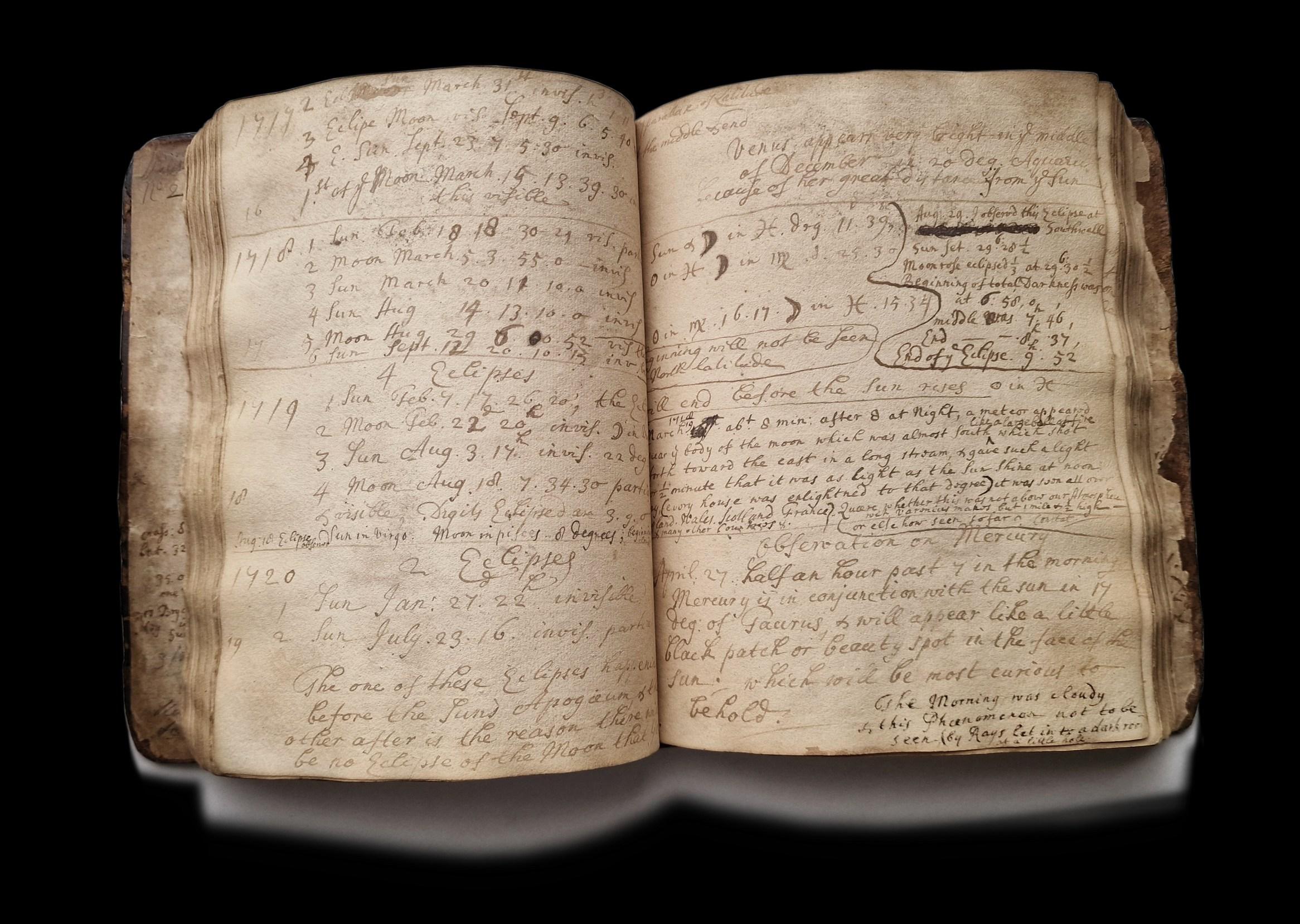

¶ Cutting, copying, writing, and juxtaposing are not merely mechanical acts they are, in effect, material forms of thinking. As such, these acts challenge and complicate conventional ideas of authorship, demonstrating how making can itself be a mode of cognition. Few artefacts capture the material texture of comprehension as vividly as A System of Arithmetic and the Mathematics, compiled by John Woods in the 1780s. More than simply a collection of mathematical texts or a record of knowledge, this volume functions as an instrument of thought: layered, recursive, and intensely physical. Part handbook, part study aid, part intellectual workshop, the manuscript exemplifies what one whose physical form and organisation do not just reflect cognition, but actively

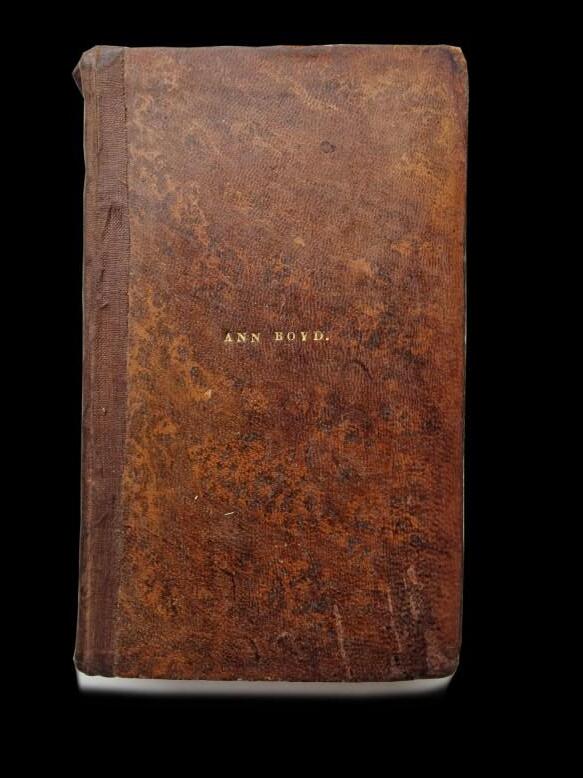

¶ [WOODS, John]. Composite Volume of Manuscript and Printed Elements, entitled [to front board] A’ System of Arithmetic and the Mathematics’. [?Swanmore, Hampshire, England. Compiled, circa 1788]. Octavo (185 x 115 x 45mm).Contemporary vellum.

The handmade clasps barely contain this manuscript’s treasures; the volume is stuffed almost to bursting with inserted fragments, intercut sequences, hand-drawn diagrams, coloured borders, and folded plates. Its structure, at first glance chaotic, reveals itself to be deliberate and crafted, looping through mathematical topics with a rhythm that hints at the author’s own cognitive process. As an object it demands physical engagement, reflecting its maker’s blurring of the line between compiler and author.

CONTENTS AND COMPOSITION

Woods’s volume is a hybrid artefact, combining printed material, transcribed excerpts, hand-drawn diagrams, and manuscript calculations. The result is a dense pedagogical or, more likely, autodidactic tool that bridges formal education, maritime training, and scientific inquiry. Its contents focus on mathematical fields essential to 18thcentury navigational and technical practice arithmetic, trigonometry, astronomy, geometry, surveying, and gauging yet its structure departs radically from any standard textbook format. The contents are drawn from a wide variety of sources ranging from the end of the 17th century through to the middle of the 18th century and are organised in an idiosyncratic manner that makes a survey challenging; we nevertheless present an overview below.

JohnHill’sArithmetick

Woods draws extensively from John Hill’s Arithmetick both in the Theory and Practice (1716 and later editions), incorporating multiple, non-contiguous fragments of it that span foundational and advanced arithmetic. Early in the manuscript, he includes Hill’s introductory definitions (covering fractions, decimals, and prime numbers) alongside unit conversion tables for money, weight, and measure. These appear on several gathered pages (e.g. pp. [1]–8 and 9–16), where Woods weaves in some unidentified material on simple geometry, before resuming Hill’s text. Further excerpts from Hill reappear in several subsequent clusters, including, in order of appearance, pages on arithmetic and geometric progressions (pp. 121–150), use of square and cube roots (pp. 235-238), logarithmic arithmetic (pp. 313-328), extracting square and cube roots (pp. 213-234), and manipulating vulgar fractions (pp. 109 -120). This final section is interspersed with two separate insertions of manuscript pages on the same subject, and many of the printed text pages have been carefully bordered in manuscript.

This breaking apart of Hill’s original order indicates that Woods intended not to reproduce the book but to repurpose it. His restructuring interrupting, skipping, and returning produces a rhythm of its own, in which sections loop back to reinforce and strengthen key concepts while setting them in dialogue with other sources and examples. The effect is one of active recomposition, shaping Hill’s content into something newly synthetic and personally meaningful.

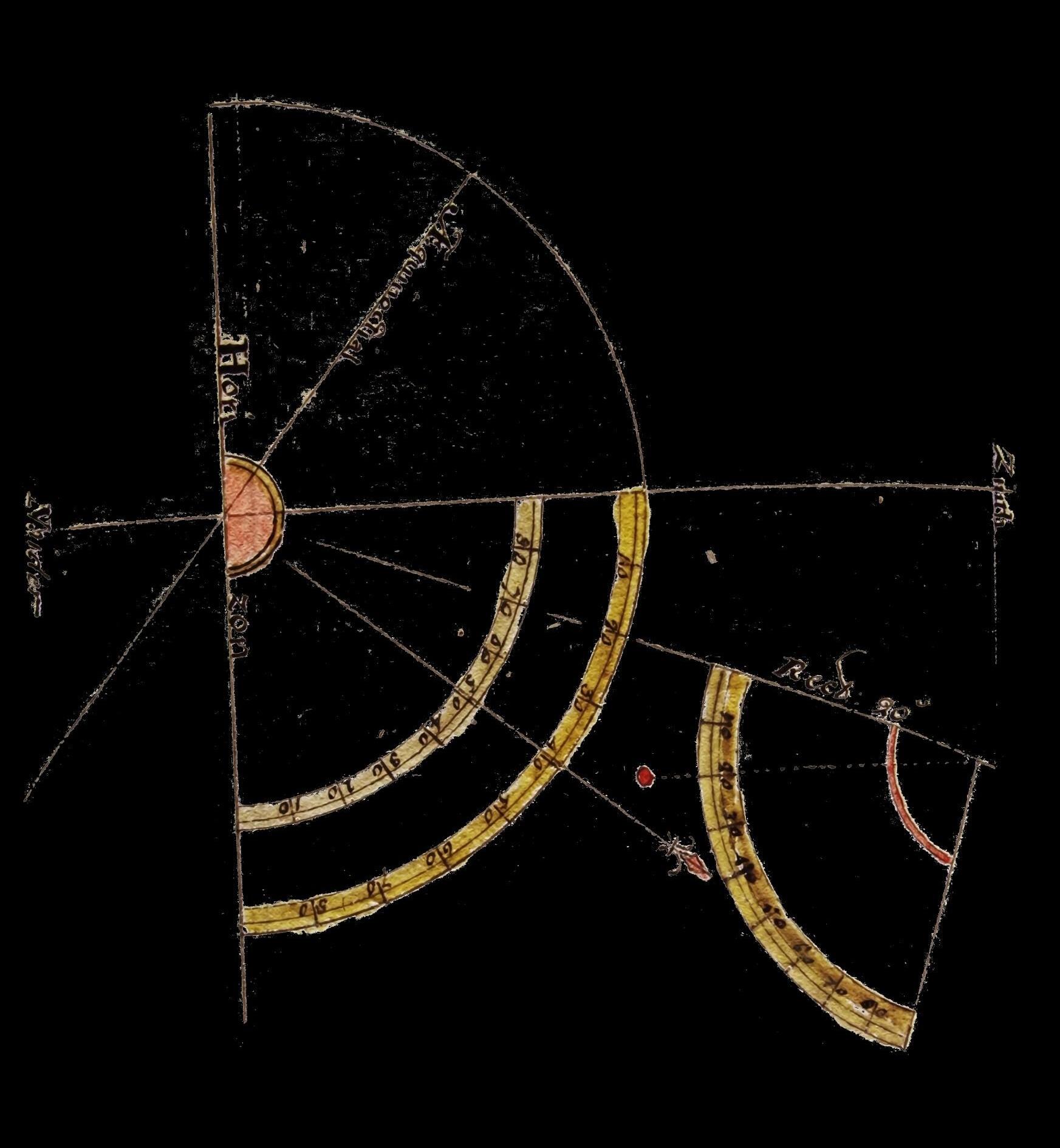

Wood has created a large and detailed section on dialling which features some 45 pages of coloured diagrams, fold-outs, geometric constructions, calculations and worked examples. We have been unable to identify the original sources for this section. This is probably because Wood has, as elsewhere, adapted the material to suit his own needs. The evident investment of time and care lavished on these highly visual pages is remarkable, and the inclusion of interleaved blank pages suggests ongoing engagement.

HenryWilson’sNavigation New Modelled

Wilson’s work forms one of the structural backbones of the volume, albeit with its vertebra broken apart, resequenced and repurposed. Across the manuscript, Wilson’s text appears in multiple sections which Woods has extracted from various editions, covering both fundamental and advanced navigational techniques. Early fragments focus on astronomical projection and spherical trigonometry (pp. 219–definitions of astronomical terms and alternative methods (pp.121–136 and Plate 9, unidentified). Woods then sets down his own handwritten summaries of equivalent problems such as finding the sun’s right ascension or altitude offering multiple solutions that use different mathematical techniques (logarithms, Gunter’s scale, plain trigonometry).

Subsequent excerpts return to more basic material, including geometrical constructions, planar trigonometry and simple sailing problems (pp. 4–14, unidentified), trigonometric methods (pp. 139–144, unidentified), and logarithmic navigation (pp. 35–62, unidentified), before including astronomical tables and problems (pp. 35 tables and compass translations (pp. 121 some cases, Woods annotates, colours, or completes these

fragments; in others, he inserts manuscript examples directly within the printed flow. Wilson’s original chapter order gives way to an organisational logic unique to Woods: one that begins with advanced material, circles back to basics, then finishes with practical computational tools. It suggests an iterative, comparative learning process less concerned with the linear development prescribed by a textbook than with following its maker’s individual concerns and journey of

Manuscriptworkedproblems

Wood includes approximately nine pages of manuscript workings which include subjects like “To find the Sun’s Altitude when due E & W” and “To find the Right Ascension”. Text remains unidentified, but it bears similarities to Henry Wilson’s Trigonometry Improv’d (six editions between 1720 and 1769), so is perhaps condensed from that work. These problems are solved using multiple techniques logarithmic calculation, Gunter’s scale, planar trigonometry often on the same page. This comparative approach indicates a pedagogical interest in method as well as outcome, reinforcing the manuscript’s function as a kind of cognitive workshop.

Printedandmanuscriptmaterialon astronomyandcalendarsystems

This section, some of which has been bordered in manuscript, includes fragments from Benjamin Martin’s The Marrow of A Companion to the Almanack (1765), and Mariner’s New Kalendar, juxtaposed with manuscript practical applications, and 12 pages from Perkins 1696. The Second Part of this Almanack. Astrological signs in

manuscript to upper margin. Towards the end of the volume, he has added pasted-in sections of a calendar from an almanac. The printed clippings have been neatly mounted and then bordered, annotated, and titled in manuscript “Old Stile”. One especially notable inclusion is a printed sheet entitled Directions for Using the Portable Card-Dial. This is unrecorded in ESTC. It was printed at Bath, by Thomas Boddely, in King’s-MeadStreet, but with no date given. ESTC records 14 publications by Thomas Boddely between 1741 and 1756; two of these record his address at King’s Mead (one also narrows his location to the Pope’s Head). In 1756, ‘Boddely’s Bath Journal’ is taken over by “John Keene, brother-in-law of Mr.

Thomas Boddely deceased”, so we can confidently date our otherwise unrecorded printed sheet to before 1756.

STRUCTURE AND USE

What was the purpose of Woods’ considerable labour in creating this manuscript? What appears at first glance to be a technical compilation (maritime calculation, surveying, astronomy, mathematical instruction) takes a form and particularly a structure that invites a deeper reading. The more we explore, the more it reveals itself as a novel creative act and a reification of process one that tells us as much about how knowledge was worked through as what that knowledge was.

Woods was likely not a professional compiler or institutional teacher, but an autodidact. Foundational topics (e.g. numeration, unit conversions, and planar geometry) appear multiple times, often after more complex material has already been introduced. For example, Woods presents spherical trigonometry problems from Wilson’s Navigation New Modelled well before including sections on basic geometric constructions, or even more simple forms of trigonometry, from the same work. Similarly, material on dialling a mathematically and visually rich topic is presented midway through, before circling back to more elementary topics.

This recursive structure challenges any assumption of a straightforward instructional logic. Instead, it suggests that Woods was curating and sequencing material in ways that reflected his own style of learning and comprehension: a style that involved assembling, adapting, and experimenting with the material tools of technical thought.

Despite being such a sui generis artefact, its author’s identity remains something of a mystery. An inscription near the end of the volume “John Woods Swanmore, 1780”, plausibly connects him to Swanmore in Hampshire, and raises the distinct possibility of a maritime connection. The village of Swanmore is located just 25 miles from Portsmouth Harbour. Indeed, it was in May 1787 that the First Fleet of ships left Portsmouth Harbour bound for Australia, taking the first British settlers there. They would arrive in Botany Bay on 18 January 1788. Was Woods a local officer, tutor, or mariner; a student of navigation, a teacher or an autodidact with a keen interest in the world around him?

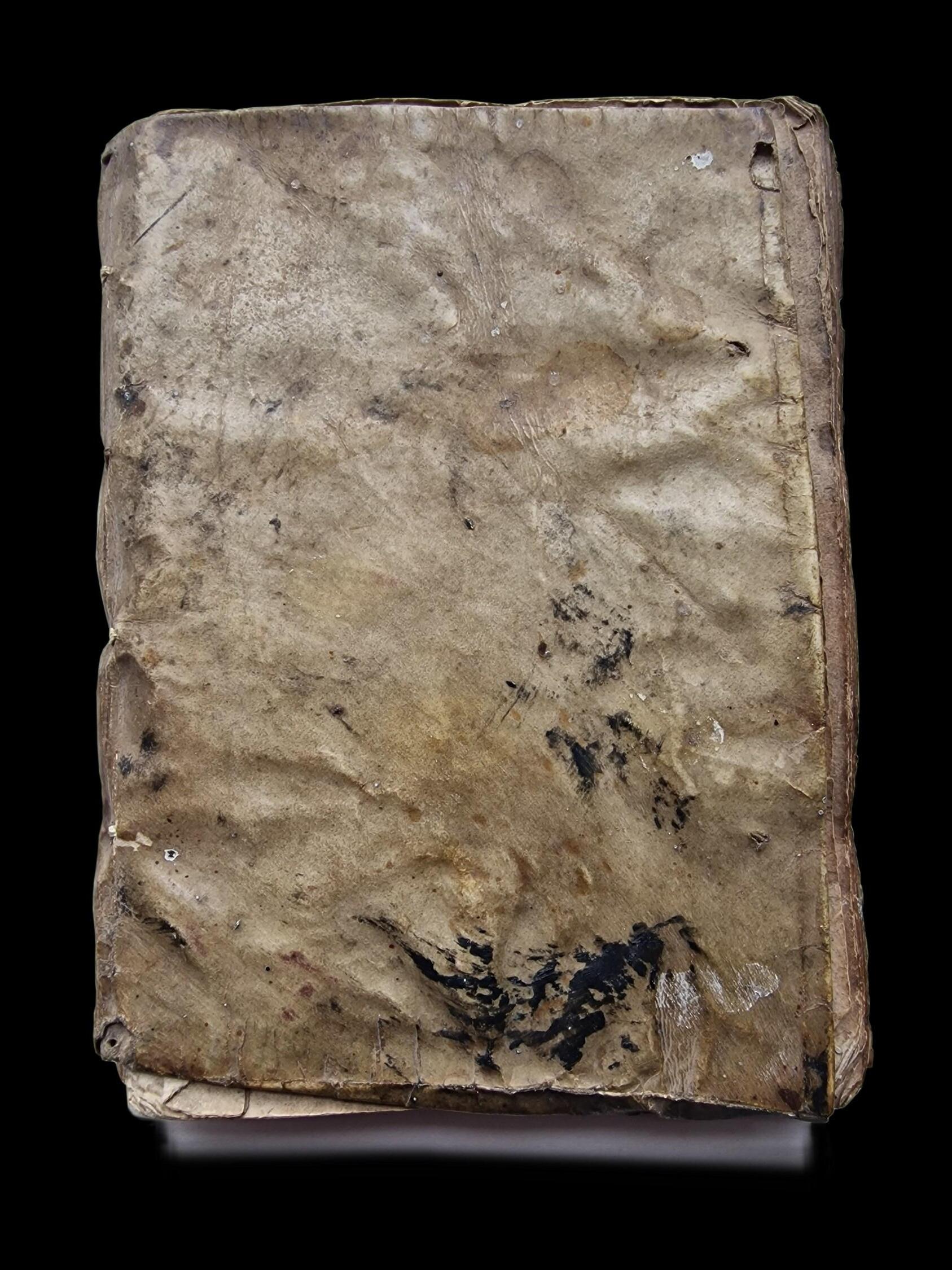

BETWEEN AUCTOR AND ARTIFEX

What makes this manuscript especially compelling is the way it blurs the distinction between auctor (originator) and artifex (maker). Woods copied, extracted, and pasted from a wide range of printed sources, including those mentioned above. But the arrangement, visual design, and material interventions are unmistakably and substantively his. In several cases, he interrupts a continuous printed section to insert manuscript content, often on a distinct but contextually relevant topic. Elsewhere, he reorganises chapters, adds marginal notes, and selectively copies out specific examples and problems.

The manuscript thus becomes a site of authorship through making. Woods is not a neutral transcriber he is shaping meaning through juxtaposition, sequence, emphasis, and visual embellishment. His additions often appear cognitively strategic: borders are perhaps intended to highlight key pages; colour draws attention to diagrams; marginalia hint at critical understanding. And yet, in other places, the manuscript is oddly whimsical containing, for instance, a pasted-in printer’s vignette or fragments of illustration that serve no instructional function. These playful insertions complicate the manuscript’s purpose: they resist categorisation as either purely practical or purely aesthetic. The result is a document in which knowledge is made not only through calculation and comparison, but also through an embodied, and sometimes slightly eccentric, process of physical composition.

Such details resist utilitarian explanations. They feel like moments of engagement for their own sake traces of enjoyment, visual thinking, or perhaps simply satisfaction in the act of compilation itself. Nonetheless they invite questions as to the nature of authorship, the purpose of this manuscript and the process of creation itself.

PAPER TRAILS

Adding a further layer of material history to the volume is the presence of a number of other inscriptions, probably by former owners of Woods’ copies of printed source texts (including Woods himself). The earliest is probably that of “Robt Darkn” (the end has been cropped) which appears on the fold-in to the front board. This suggests Woods has used an old vellum document to create the binding, and that the original text has been carefully washed away, save for the ownership inscription to the inner board. Woods has then neatly inscribed its new identity (“A System of Arithmetic and the Mathematics”) across the front board.

Whether Woods had been amassing texts for some time before embarking on his planned work is moot. His earliest inscription is the abovementioned “John Woods Swanmore, 1780”, which he has written on the title page to A Companion to the Almanack, for the Year 1765. He has, then, certainly been grappling with the subject since at least the beginning of the decade. His ownership inscription to front paste-down reads “Jn Woods August 10th 1788”, but we do not know whether he commenced or completed (or something in between) the book at that time. In any case, just a year later it was in the hands of a new owner, when it became “John Morells Jr Augst 5th 1789”.

Woods has inscribed two other texts: the title page of The General Magazine (“John Woods 1788”) and p.121 from Henry Wilson’s Navigation New Modelled. On the facing page to this inscription, there is a brief annotation to a single page from The Gauger’s Practice (“Came out of Winton Jany 30th / Came out of Bristol Feby 6th” and two further locations), which is signed “W. Dormton”. Other users of sections of the volume presumably before Woods repurposed them are “Oliver Ambrose His Book” whose inscription appears on the first text leaf of the volume, and “John Sluorr”? to the back of ‘An Accurate Map of the World’ – a folding plate from 1759 The General Magazine. Given their peripheral positioning, these inscriptions are probably by previous owners of harvested texts rather than owners or readers of the ‘finished’ work.

CONCLUSION

Those earlier inscribers add to the multitude of scribes, authors, readers, compilers, makers, and other users who have all converged wittingly or otherwise in the creation of this unusual hybrid object: manuscript and printed, instructional and reflexive, authoritative and exploratory. A paradigm example of a formative manuscript, John Woods’s “System of Arithmetic and the Mathematics” is fragmentary, interleaved, non-linear, but neither chaotic nor careless: it has been shaped by use and reflection, and by recombining and reshaping its source materials to become a form of knowledge-making in its own right. And it is Woods’ idiosyncratic agency which has brought these strands together.

In its interruptions, insertions, and re-orderings, the volume models a kind of embodied cognition that moves through the fingers, eyes, and pages. It invites us to rethink what it means to learn, to author, and to make. It is a record not just of what John Woods knew, but how he came to know it. It also reminds us that books, manuscripts, and hybrids are not passive receptacles, but instruments of thought – and that learning is both a shared experience and a deeply personal matter.

£6,000 Ref: 8354

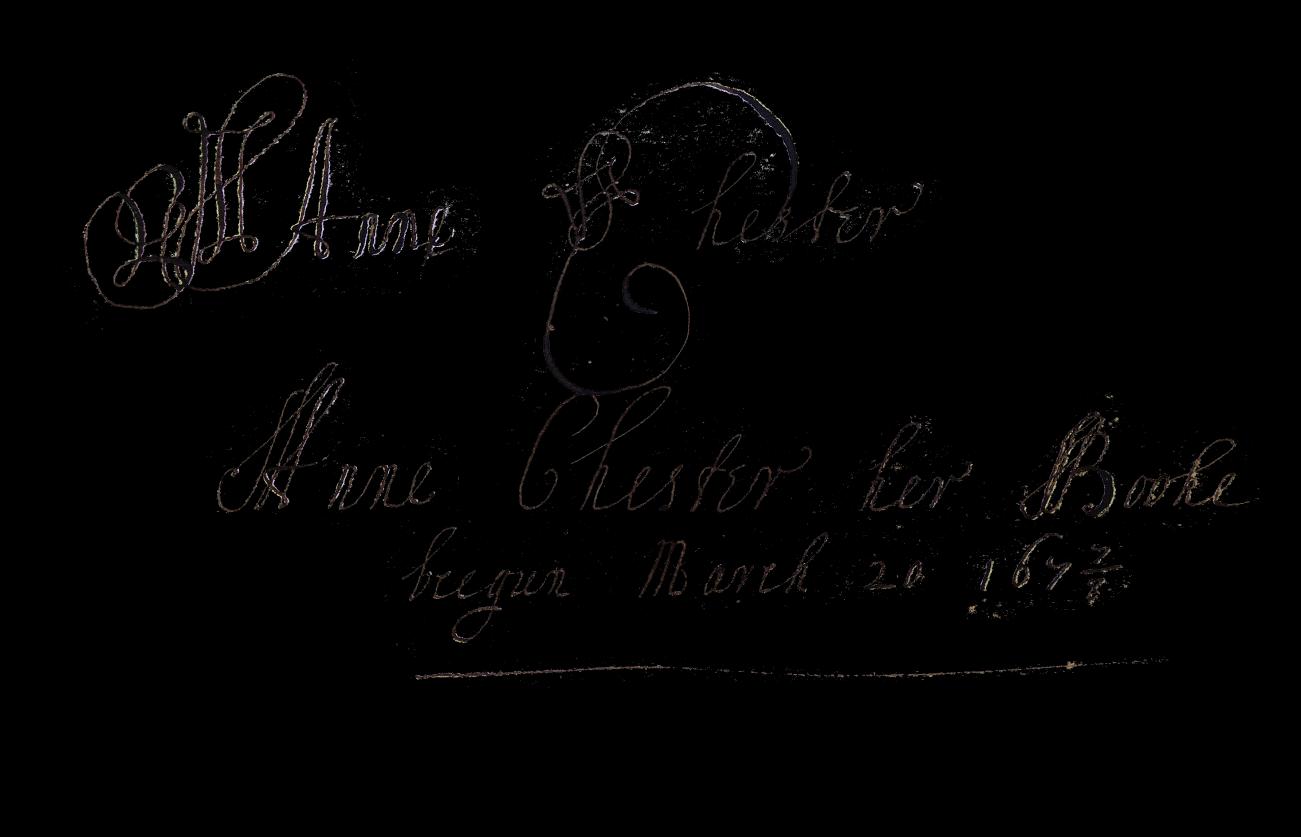

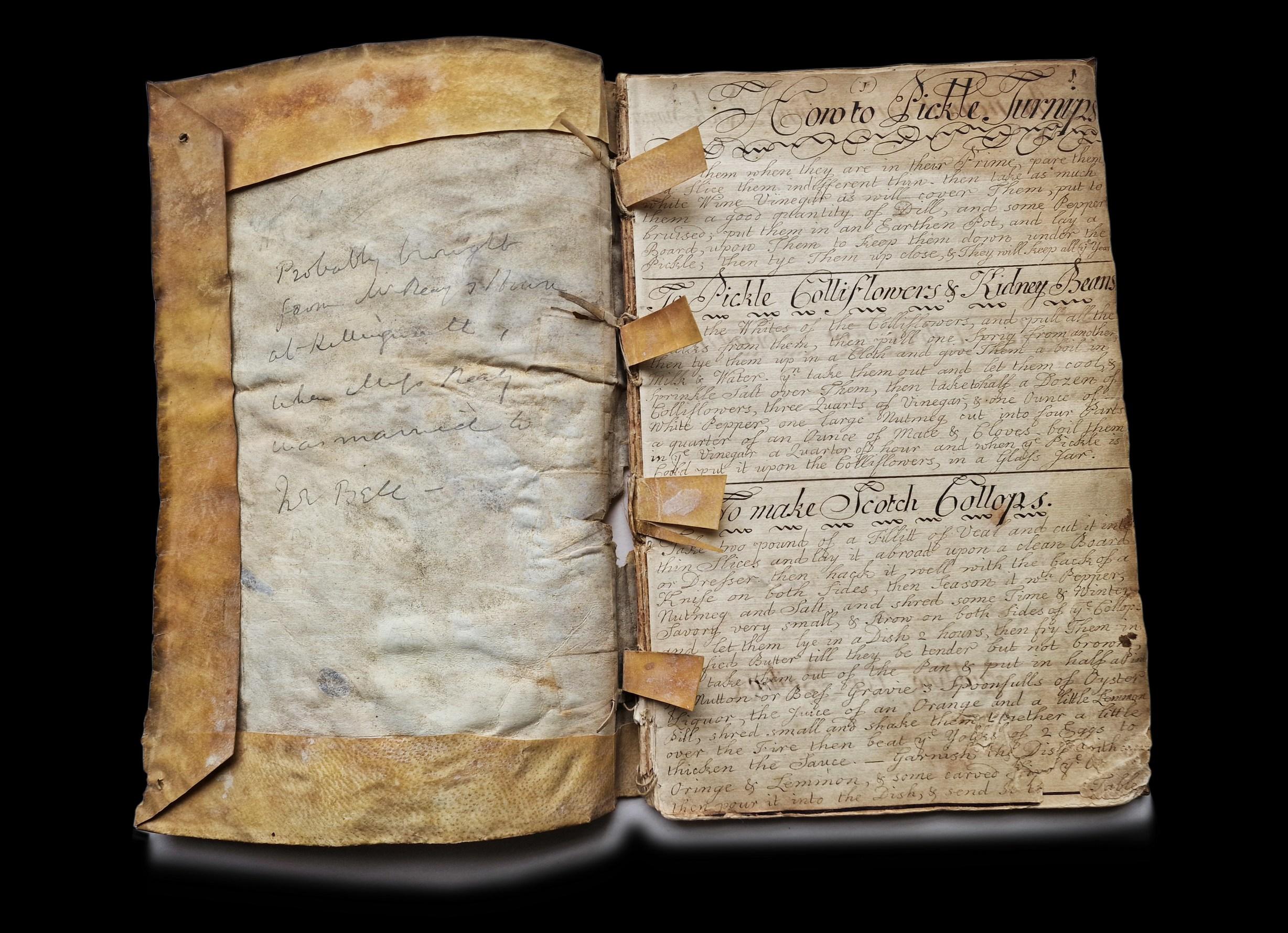

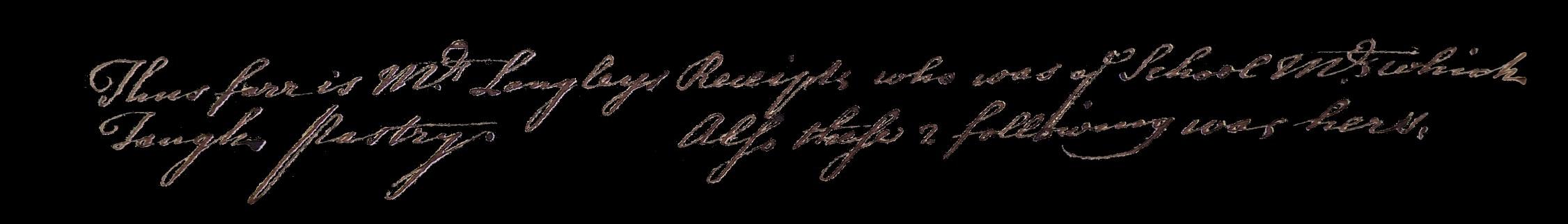

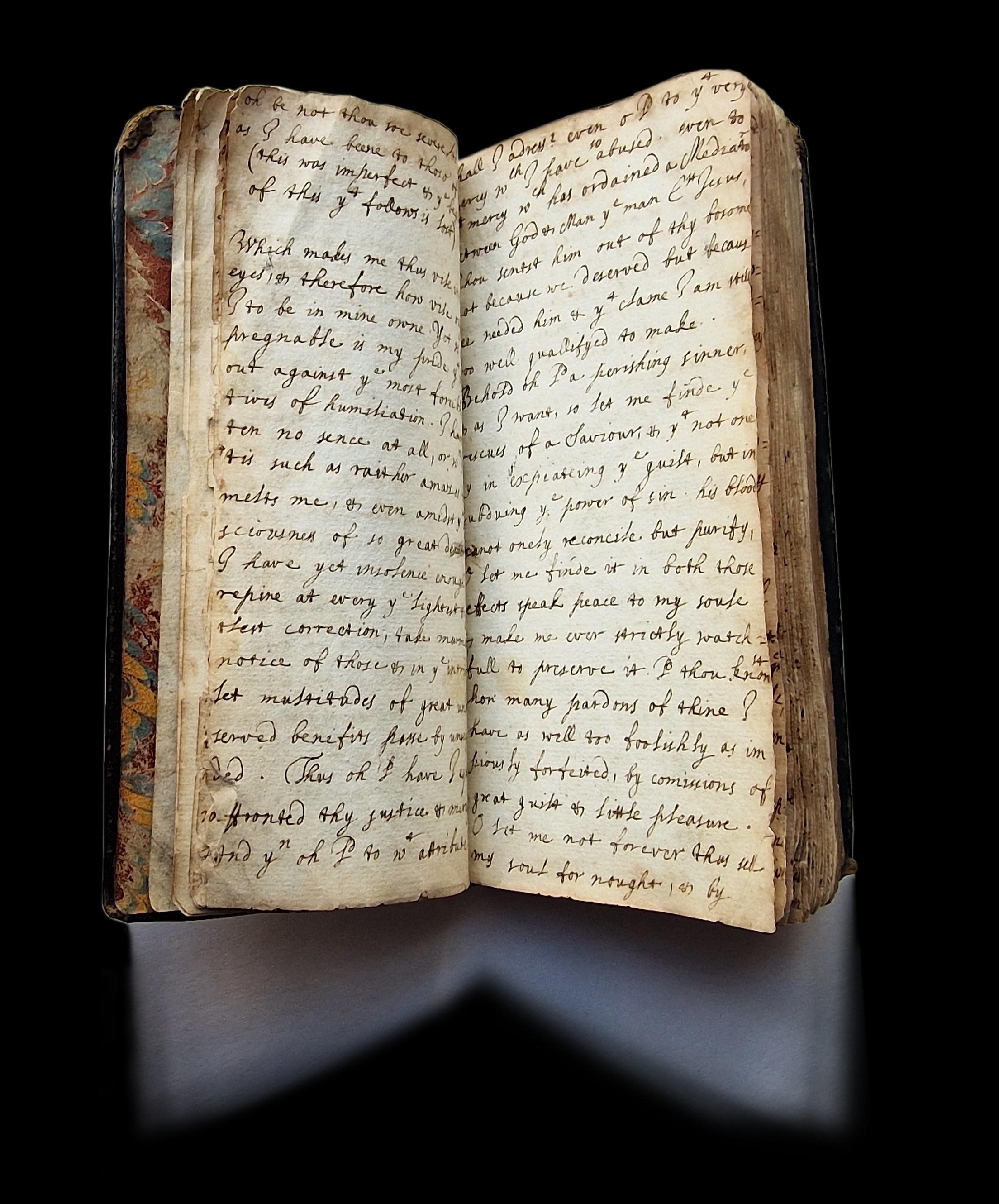

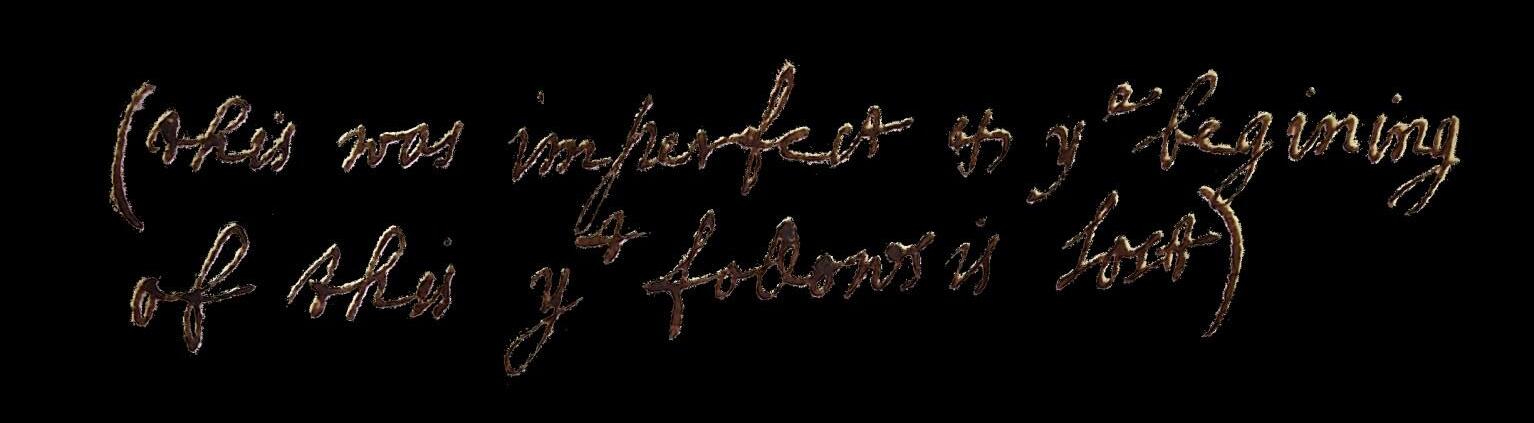

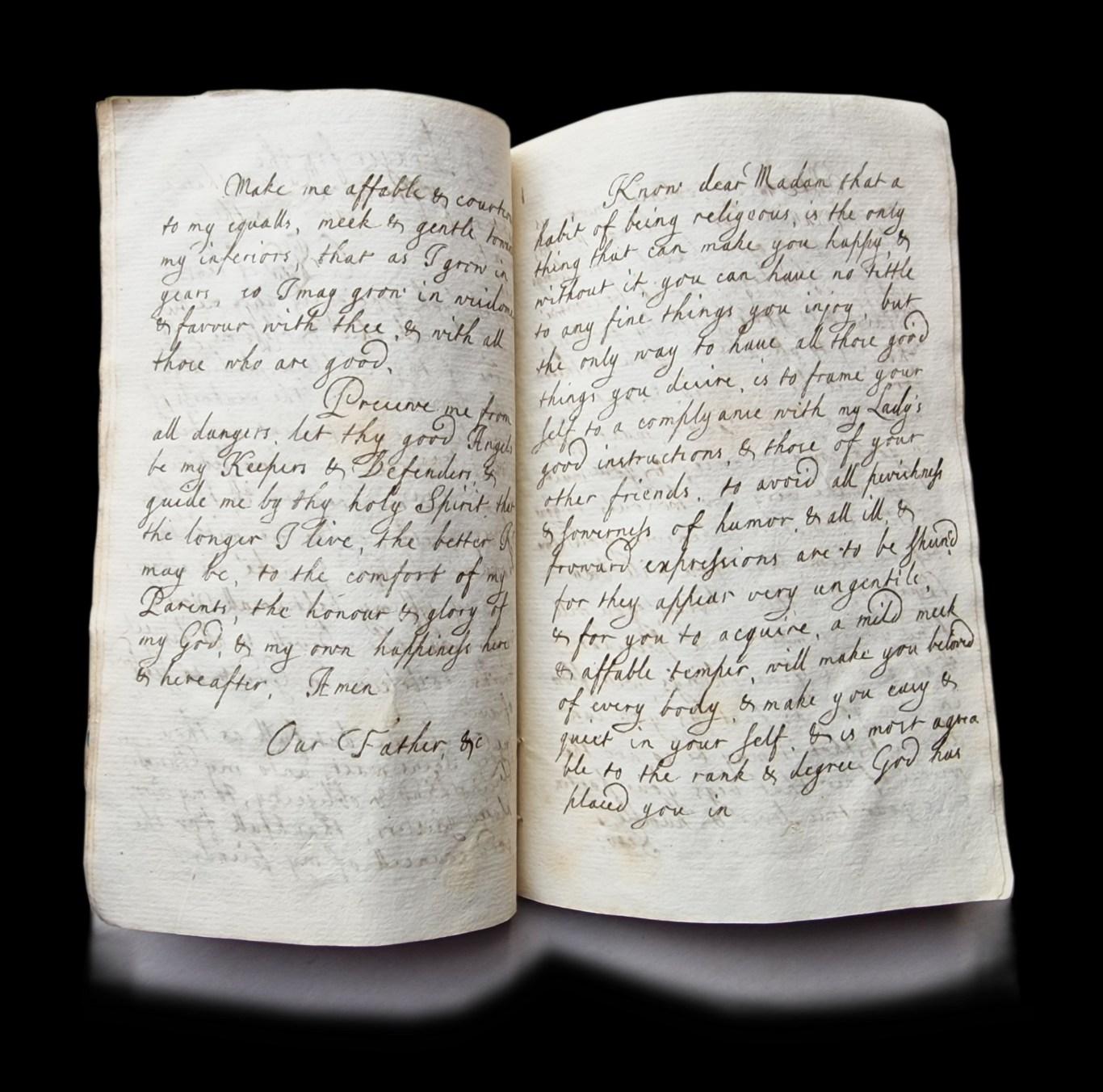

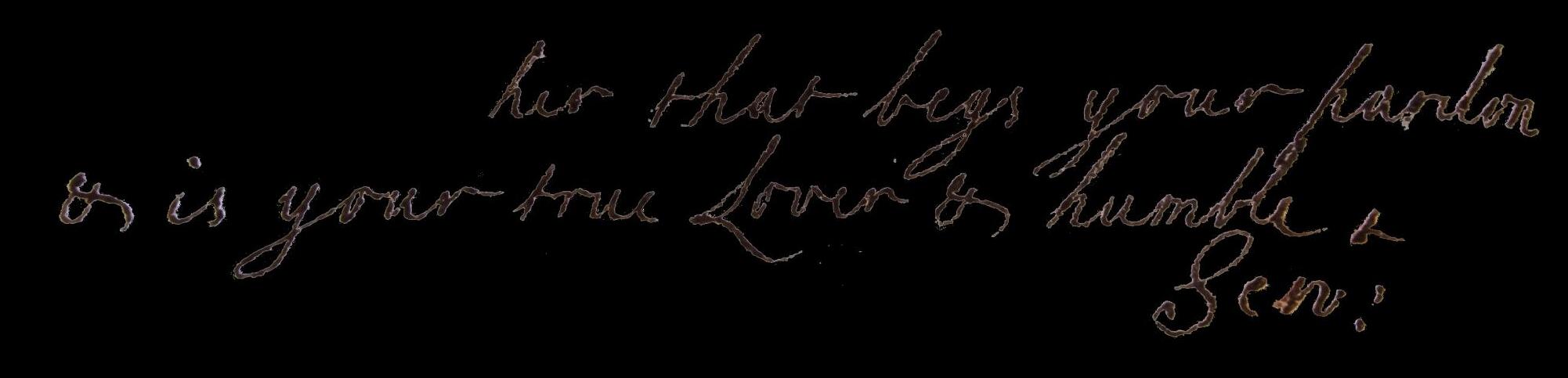

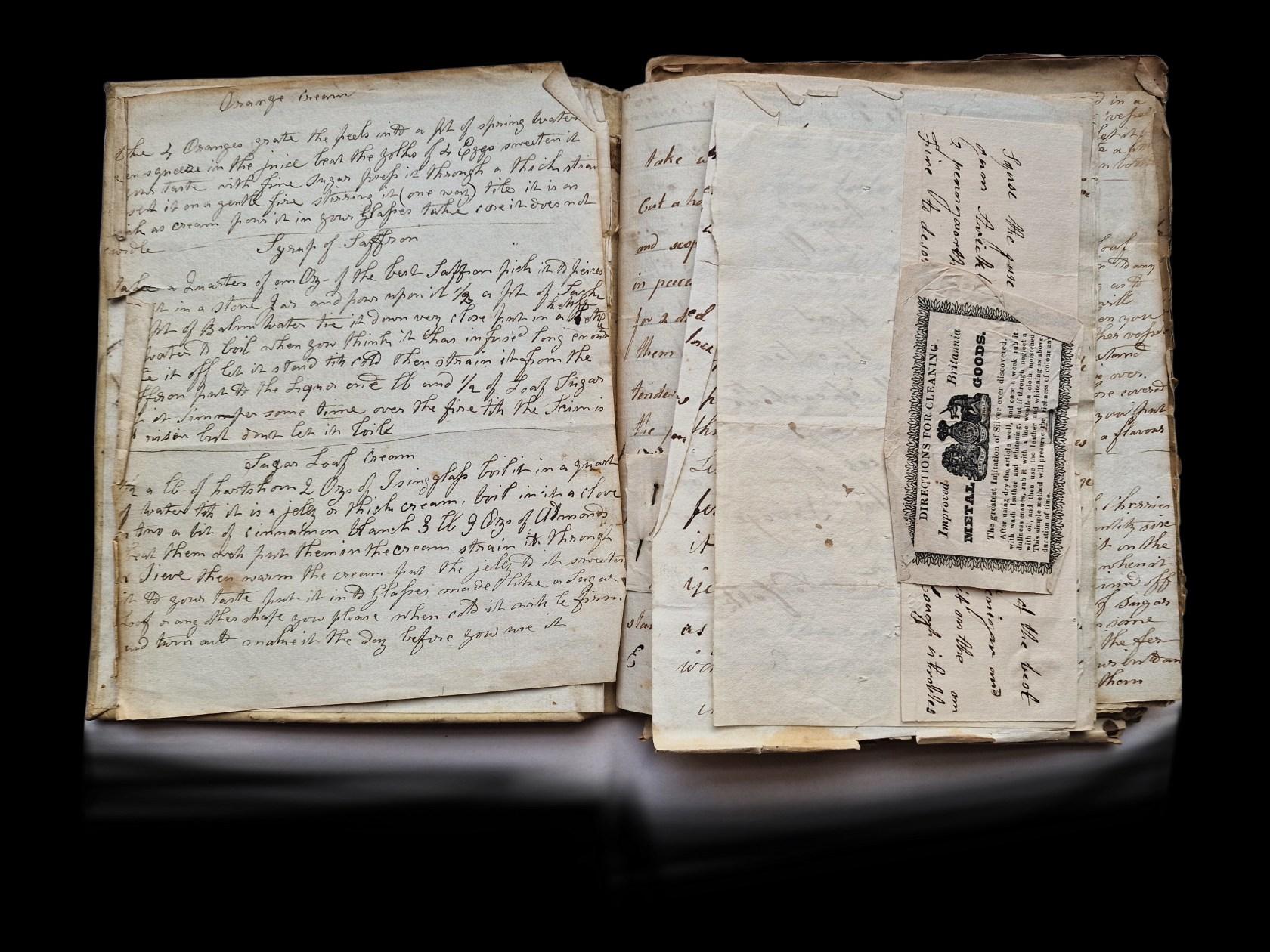

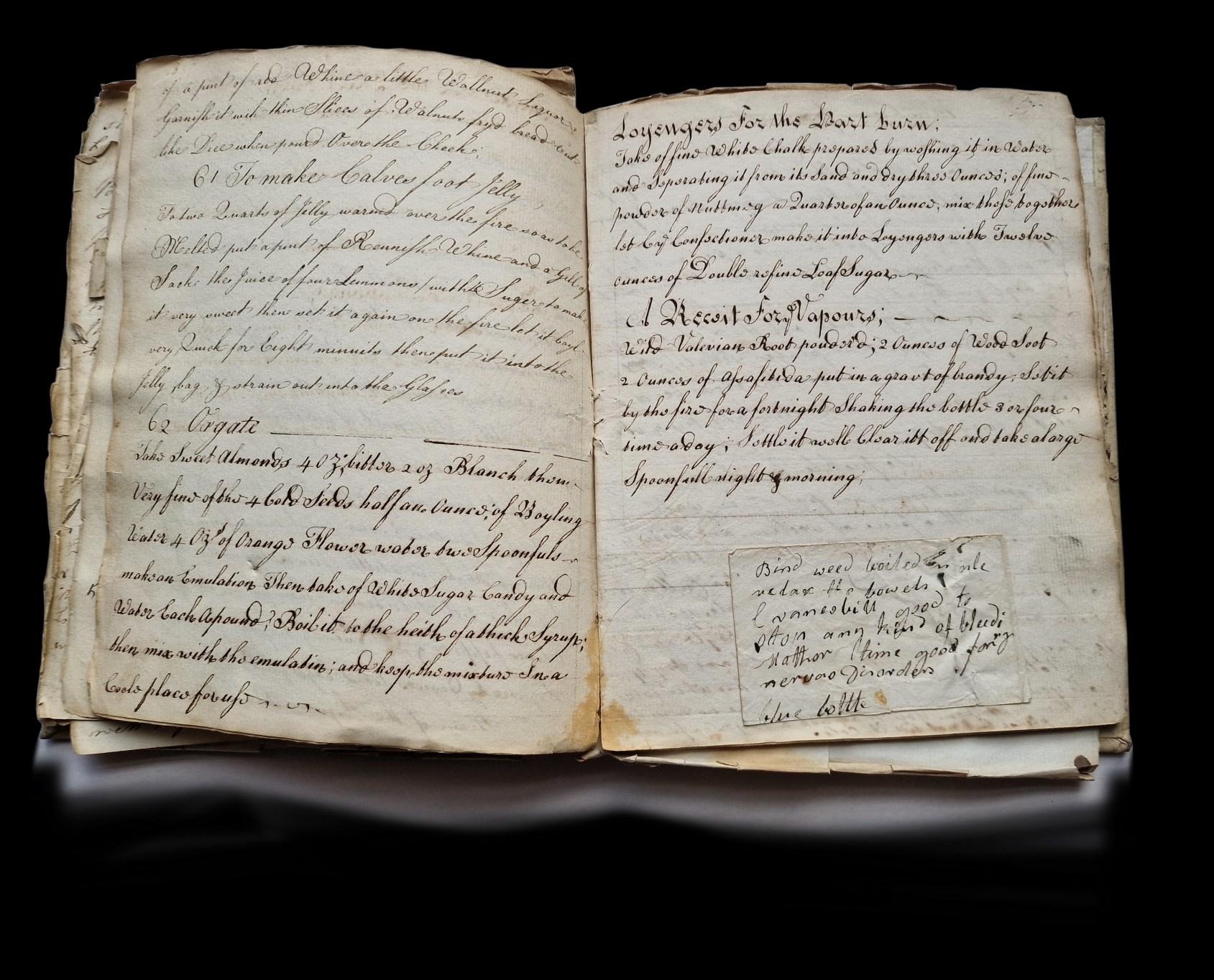

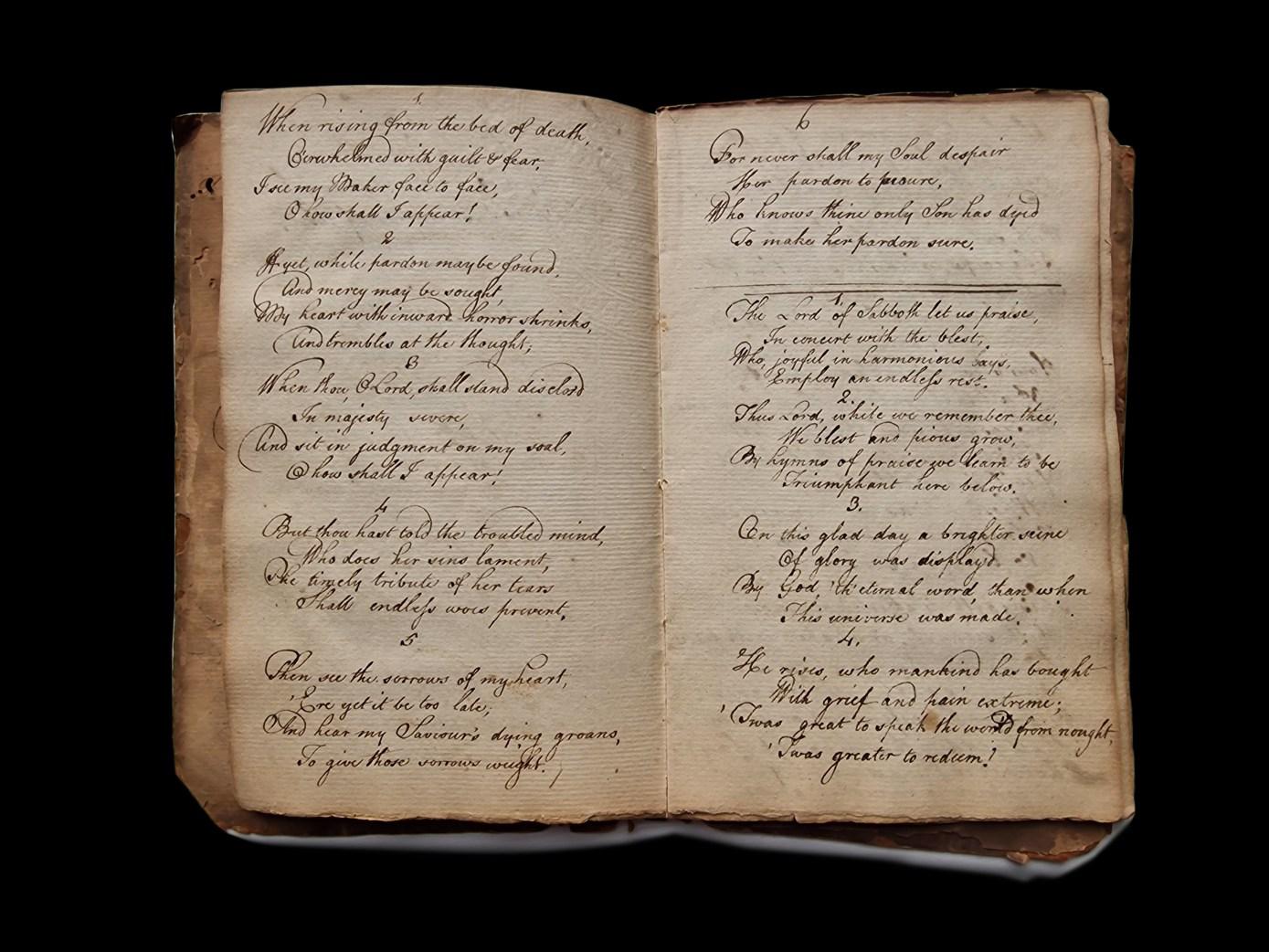

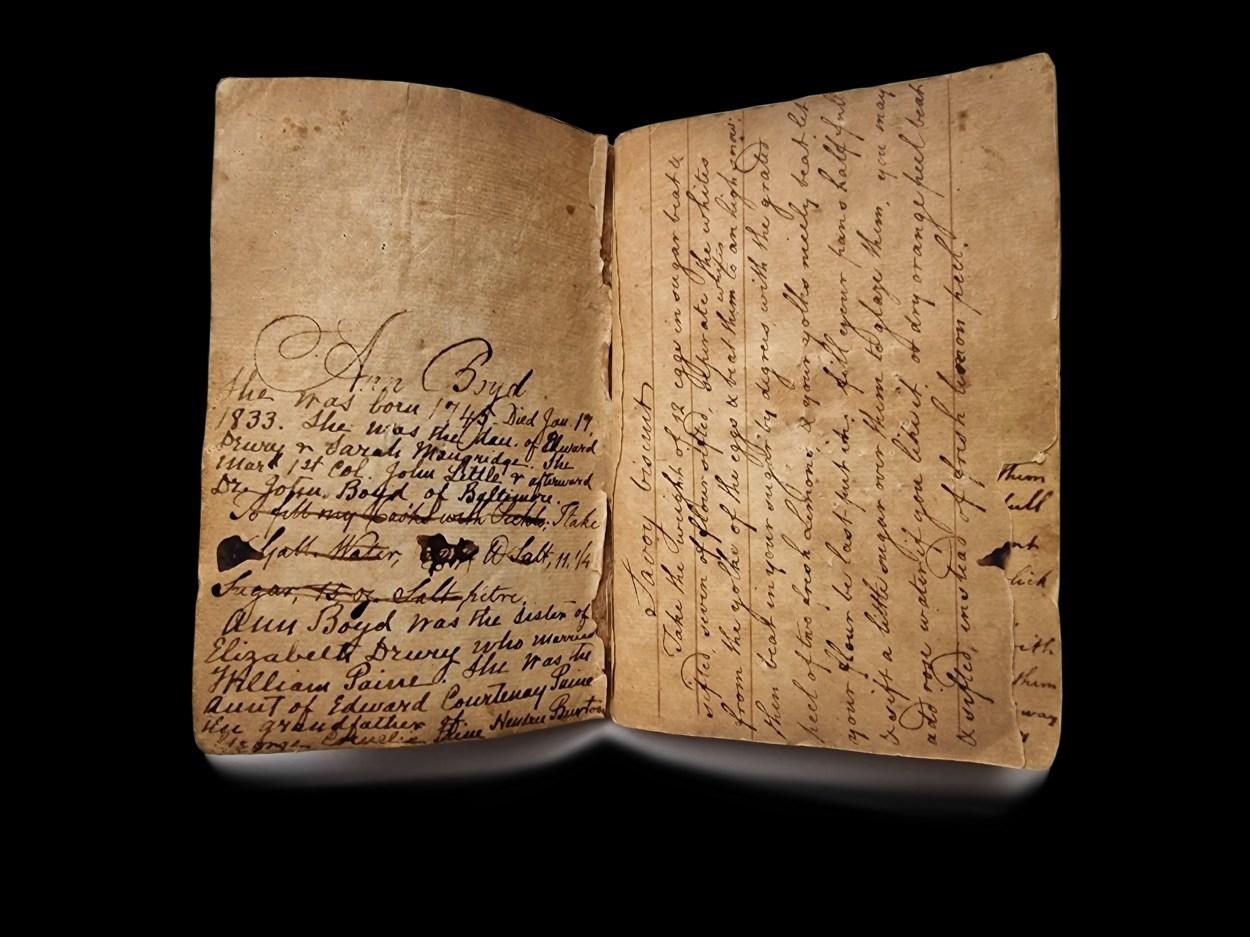

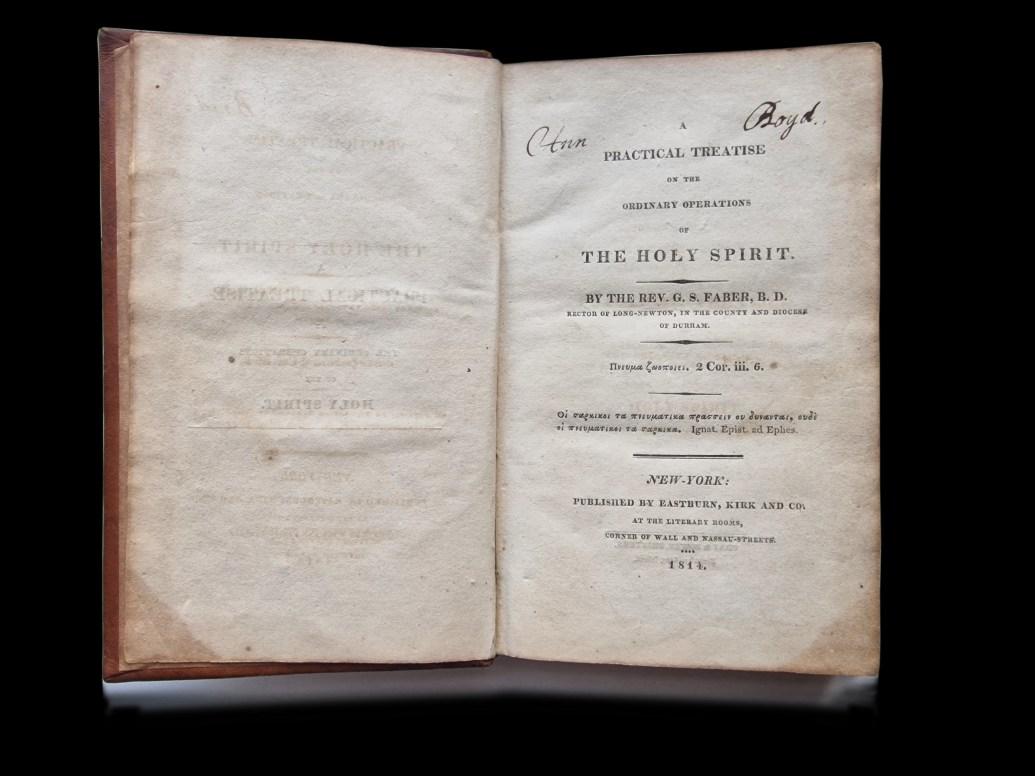

2. MY OWN PORTIONS

¶ Authority, authorship, and agency overlap, interlink and jostle, side by side and layer upon layer in this multifaceted manuscript. What probably began as something like a dowry manuscript a depository of practical and prestigious knowledge capital that a young woman could carry with her into marriage has, through circulation, curation, experimentation, and organisation, been transformed into a living document, responsive to new experience, new responsibilities and ongoing household needs.

Its compiler, Anne Chester, underwent her own transformation. Having started this volume aged around sixteen, she married and in due course became the head of a complex household. This is borne out by the record of her husband’s will (National Archive PROB-11-518-338), which leaves her the house, its contents, and its surrounding lands. Other property is left to various family members mostly their eldest son and Anne’s share perhaps represented her dower: that is, her right to a third of the total wealth during her lifetime. The will’s terms appear to go beyond the minimum, underscoring her authority by also making her joint executor. The manuscript thus both aids and records Anne Chester’s development from adolescence to marriage, to motherhood and matriarchy, and thence to widowhood, inheritance and management of a large estate.

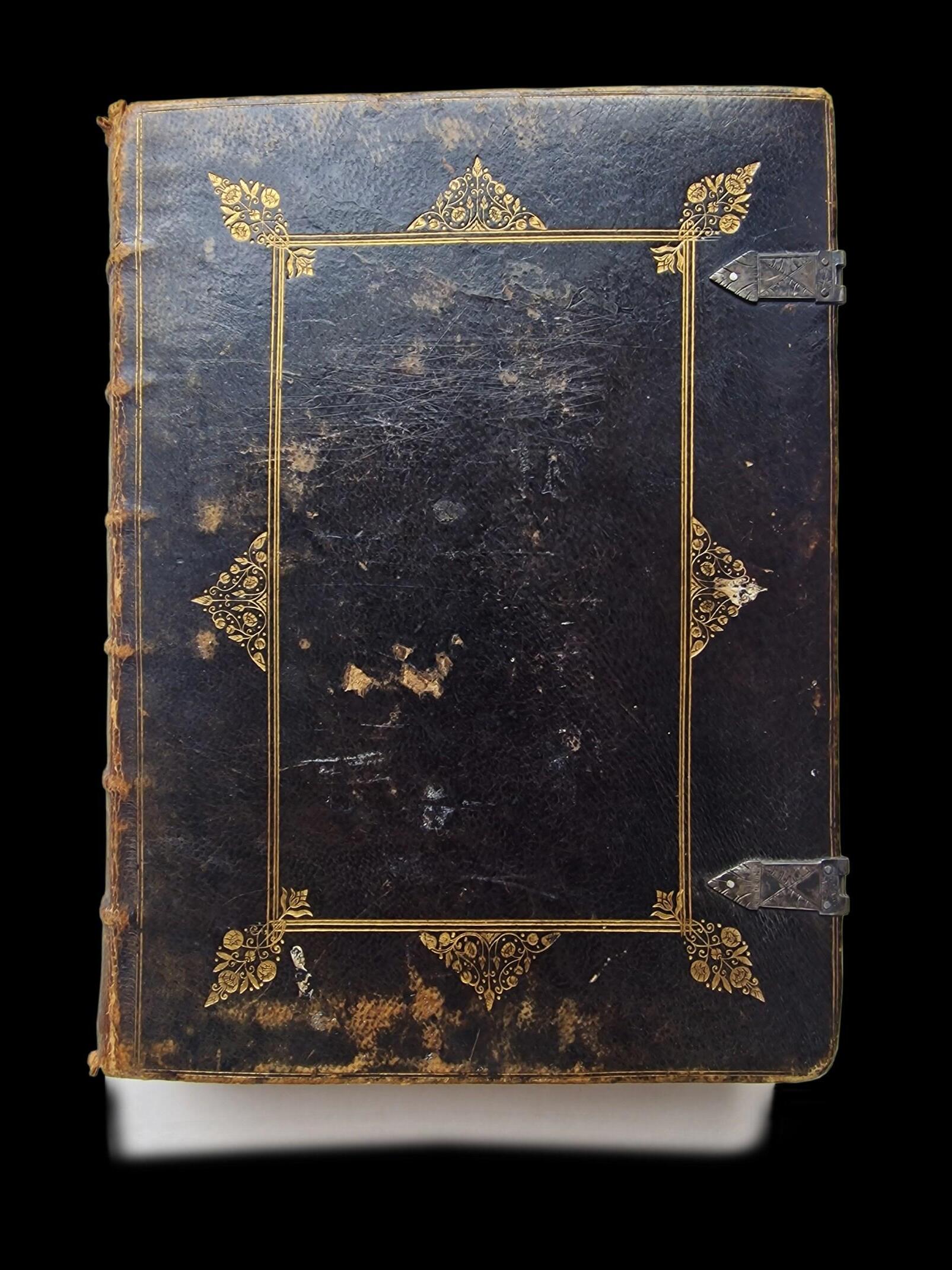

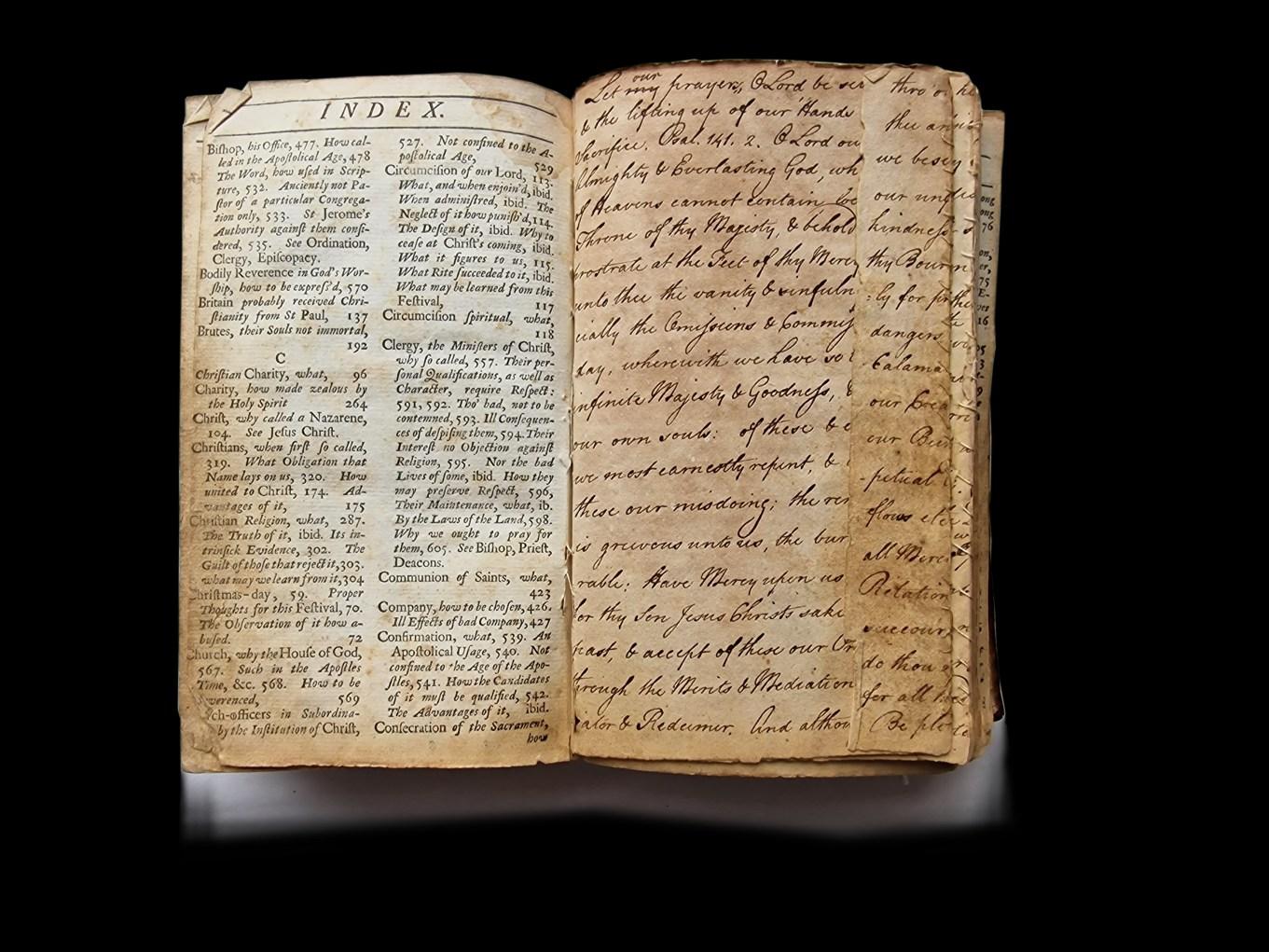

¶ [CHESTER, Anne (later FOUNTAYNE) (1661-1743)]. English 17th Century Manuscript Household Receipt Book. [Barkway, Hertfordshire, and Melton Manor, Suffolk.Circa 1677-1740].

Quarto (236 x 175 x 40 mm). Text arranged tete-beche: [1 inscription], [1, blank], [1], [3, blanks], [2, index], [8, blanks], 123; [1, blank], [7, index], [4, blanks], 82 text pages. A total of 206 text pages and nine pages of indexing on 188 leaves. Over 450 receipts in a 17th century hand (many quite brief) and 25 in a late 18th–or early 19th century hand.

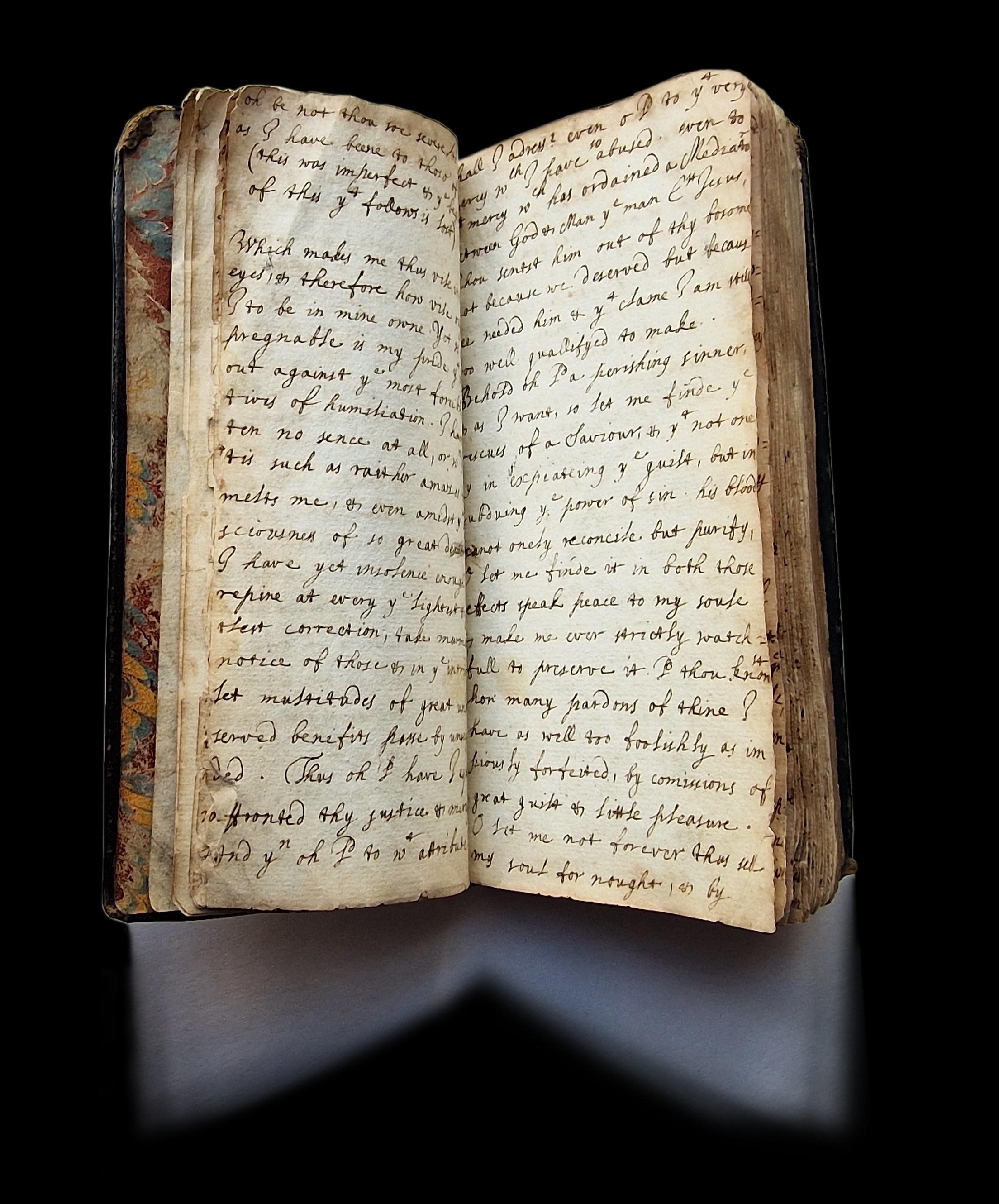

The miscellaneity of receipt collections can sometimes work against discussing them in an orderly way, as is the case here. Both an embarrassment of riches and a many threaded social document, it resists a simple breaking into categories or themes. Our descriptions below attempt to reflect at least some aspects of this multifarious manuscript, focusing on connections and preserving the porous nature of the contents.

APPEARANCE AND ORGANISATION

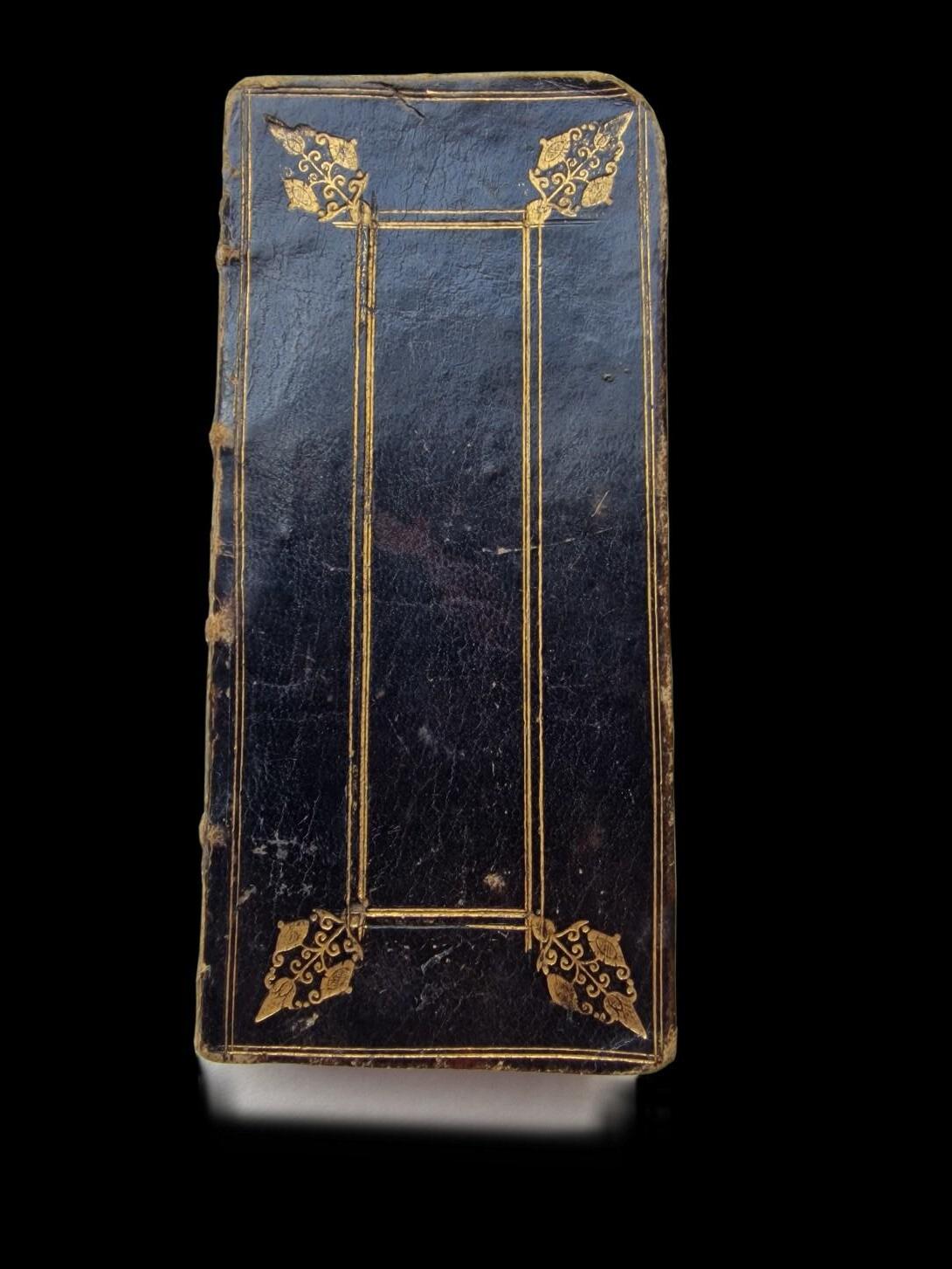

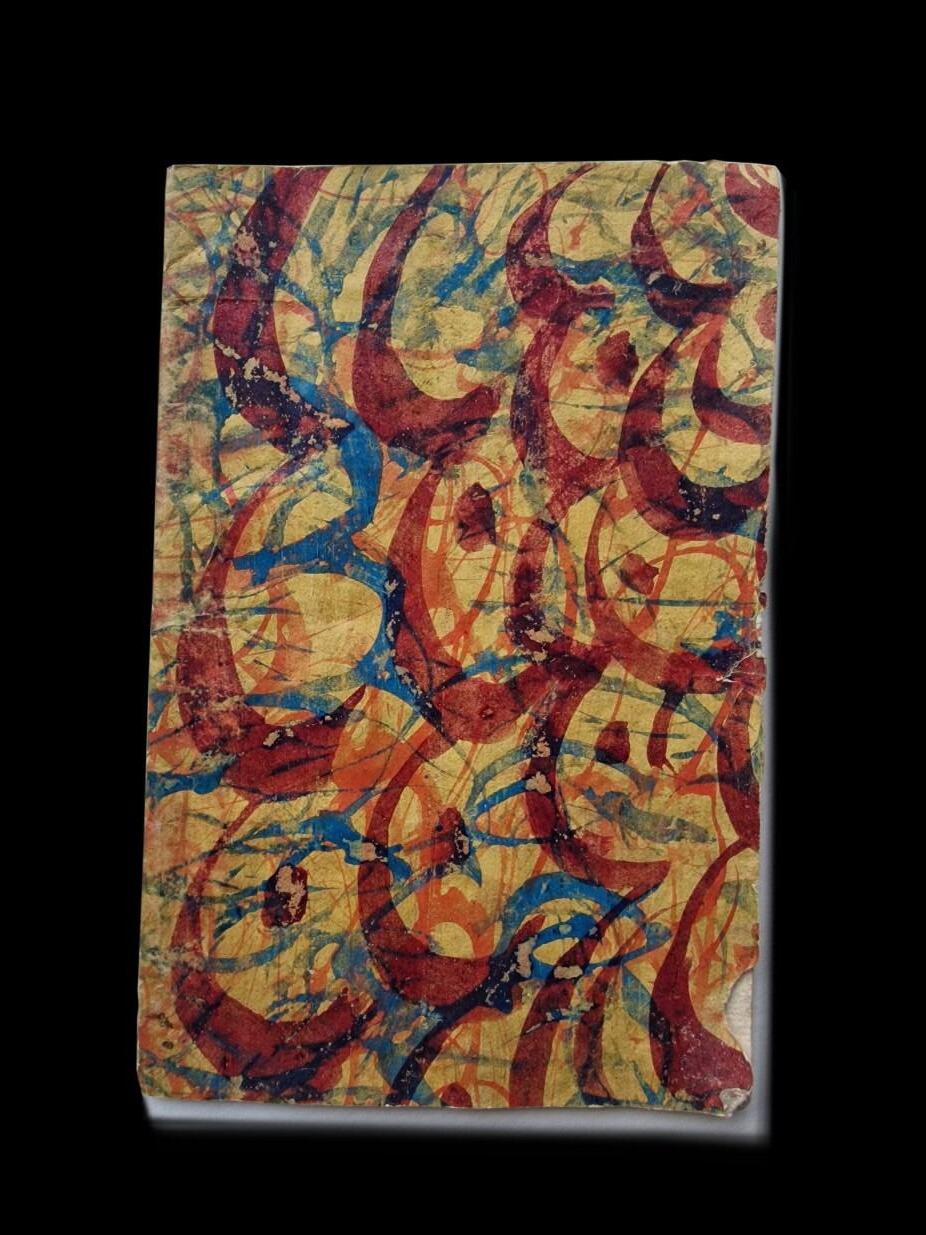

Contemporary black morocco, panelled boards, gilt, clasps broken, marbled endpapers, all edges gilt, front endpaper loose,and lacking rear endpaper.

Watermark: Fleur-de-lis, above 4, WR; Countermark: IHS surmounted by a cross.

(See Haewood 1788-90, and 1793).

The volume is handsomely bound in black morocco with gilt tooled panels, all edges gilt. The binding is rubbed, and it would once have been secured with clasps, however these are now broken with only segments remaining. Nonetheless, it retains its identity as a volume created to impress, an impression emphasised by the care taken in mise-en-page; the text is bordered throughout (although this peters out near the end of each section), including between receipts, most of which are neatly titled. There is an index at the beginning of both sections, and the remedies are arranged in (roughly) alphabetical order, with some receipts organised into subsections. The order has been slightly disrupted over time, as more receipts were added, and the beautiful page layout is not maintained by later users, but its original albeit decidedly miscellaneous structure survives.

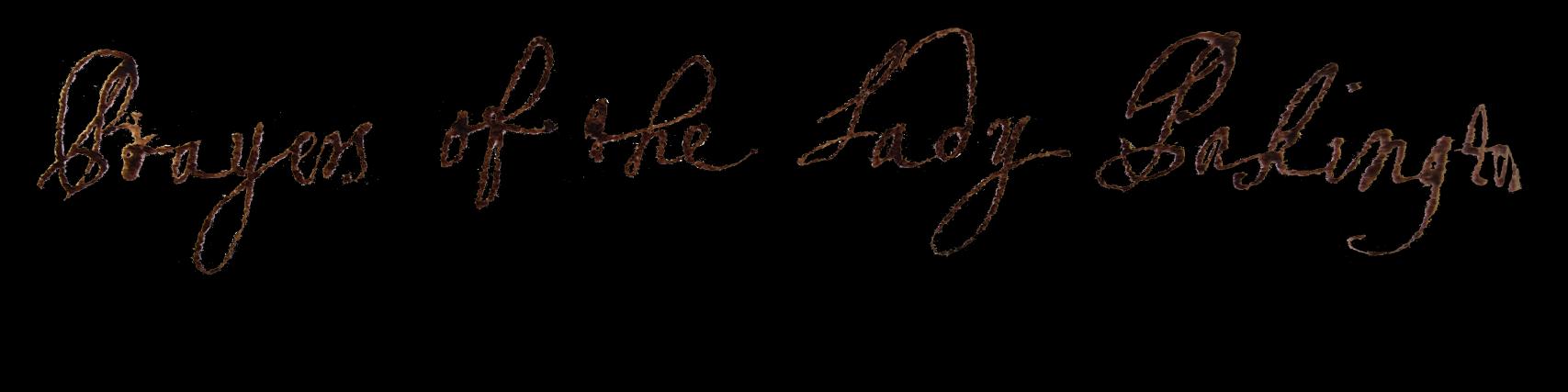

Provenance: Elaborate inscription to front blank: “Anne Chester / Anne Chester her Booke / begun March 10 1677/8”.

Bookplate to pastedown of Frederick James Osbaldeston Montagu, OBE MC (18781957), of Lynford Hall,County Norfolk.

This (initially) careful presentation strengthens our conjecture that the book was originally created as a dowry manuscript of the kind discussed by Pennell† and others. Such volumes are even more interesting when, as here, it was intended not just to impress, but to aid the complex business of making and running a household over several decades.

WHO WAS ANNE CHESTER?

The ownership inscription “Anne Chester her Booke” is complemented by a small marginal note on page 28, next to a recipe for “A Sack Positt”, which reads: “my mother fountaynes way”. This confirms our scribe as Anne Chester (1661-1743) of Barkway, Hertfordshire, daughter of Edward Chester, Sheriff of Hertfordshire (16431718), and Judith Chester (née Wright), daughter of Edward Wright of Finley. Anne married Thomas Fountayne (1639-1709), of Melton Manor, Suffolk, who attended King’s College in Cambridge, studied law at Lincoln’s Inn, and became a barrister. He inherited High Melton in 1680. Anne and Thomas had four children: John (1684-1736), who married Elizabeth Carew (1688-1768); Thomas (d.1708), who died of smallpox while a student at St John’s

College, Cambridge; Anne, who married Simon Patrick, of Dallam, Suffolk; and Judith, who married Thomas Sherlock, Master of the Temple.

Interestingly, she leaves the “Anne Chester her Booke” inscription unchanged, never amending it to her married name. We shall follow her example by continuing to use her birth name here.

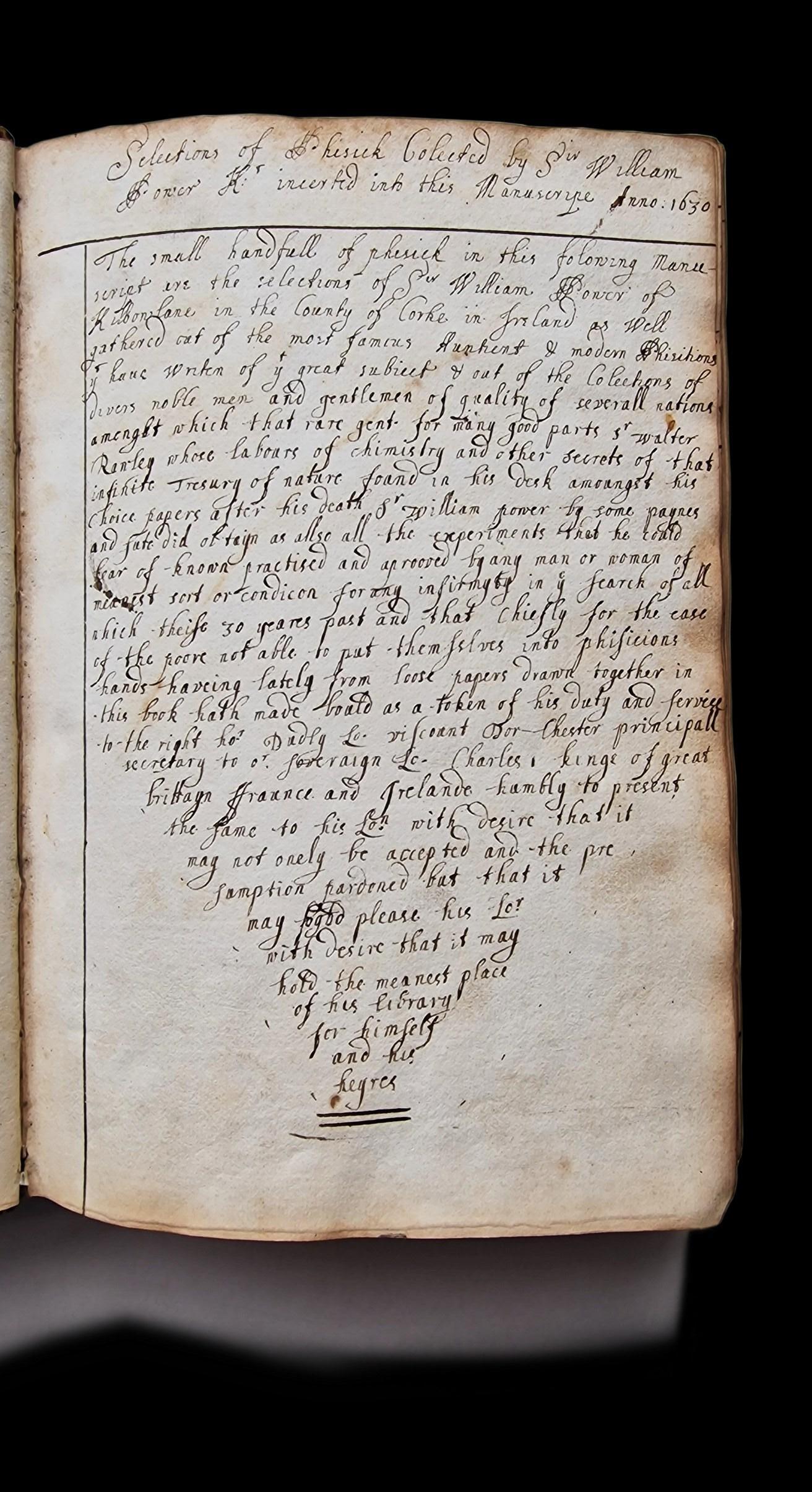

PAPER TRAILS

After her ownership inscription, Chester writes the title “Selections of Phisick Colected by Sir William Power Kt incerted into this Manuscripe Anno: 1630” (clearly copying this out from her source material, since it predates her own birth by over 30 years), indicating that this was her first inclusion. Her sustained bursts of labour transcribing these “Selections of Phisick” suggest that she was consciously laying a firm foundation for both her book and her future.

A certain prestigious and layered lineage is also implied here: Chester copies out a lengthy account in which Sir William Power (1565-1649) claims to have obtained much of his material from the posthumous desk of Sir Walter Raleigh (c.1553“gathered out of the most famous Auntient and modern Phisitions”, among them “Sr “labours of chimistry and other secrets of that infinite Tresury of nature” had been “found in his desk amoungst his Choice papers after his death.” The narrative, which at times is a little confusing, continues with an explanation that Power, “as a token of his duty and service to the right hon Dudly Lo. viscount Dor Chester principall secretary or soveraign Lo. Charles I”, passed it to the said Dudley Carleton, 1st Viscount Dorchester (1573 -1632), in the hope “that it may hold the meanest place of his library for himself and his heyres”.

Chester has been careful to mark over 20 of those she understands to be Raleigh’s with the initials “W R”. Included among these is his “great Cordiall”, a widely circulated 17th-century nostrum, which often contained as many as 40 different herbs (ours has a relatively restrained 30).

The “Vertues of Balsamums” (p.13) is annotated “W R” in the margin and includes several endorsements: “I have taken a way the grievious paine of my breast with a plaster of balsamum of succianum mastick & Antimone a pliedto-the place & I think that any of them will do it”; another has “I have cured a most dangerous swelling in my own knees with the balsamum of succinum mastick & caramen […] and with ther oyle above 30 persons of the dead palsey & as many of the Sciattica & other Aches”; and other similar commendations. But it is not clear whether it was Raleigh, Power, or Chester who claimed to have benefited from the balsam.

Other sources of medical authority supply remedies and treatments such as “Dr pamans bitter drinke for an auge” (ague, we assume) (p.66); “Lozenges for a Rhume Dr Rattliff”(p.104); “Dr Dentons Bitter Drink for an Auge” (p.105); “To procure quick Labour. Dr Chamberlin” (p.112) and “Dr Andersons pills which he gave to Duk Latherdale”. Less recognised figures are also on hand (“Mrs Scribb her Re- for ye yellow Jaundes”. (p.55); “Mrs Kays plaister” p.109); “A Water for ye Eyes Cosen Parson” (p.96)).

How did Chester come by this manuscript or its contents? We can find no family connection to Carleton or to Power. But her careful, even reverent copying down of the chain of attribution underscores the material’s importance and symbolic value. Chester was not only preserving a line of intellectual descent, but positioning herself as the inheritor, custodian, and active participant in a tradition of empirical knowledge. This is evident via attributions, comments, endorsements and revisitings she has made over the following decades.

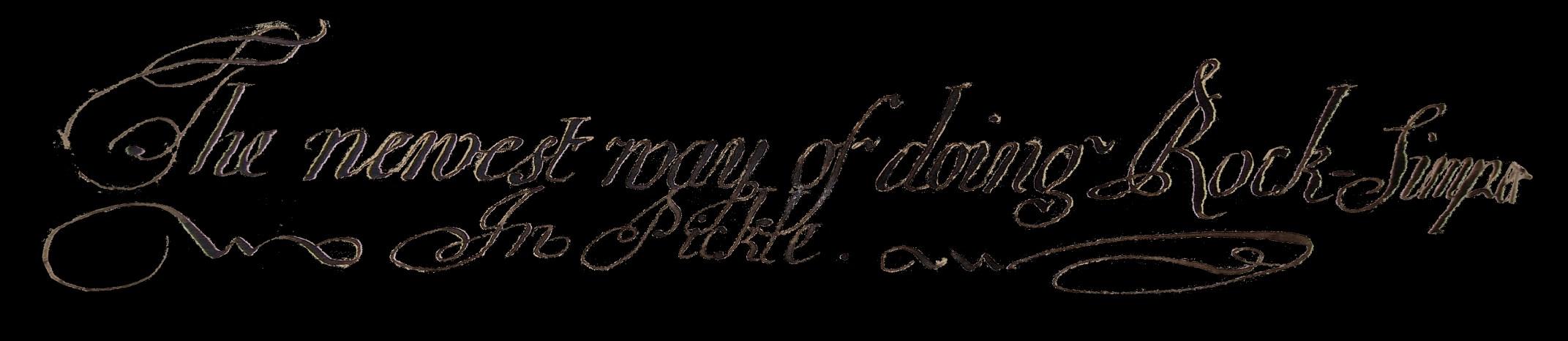

MY OWN MAKING

The multivocality of the remedies, as well as uncertainty as to how much Chester has transcribed verbatim from Power’s manuscript or has added herself, make the attributions in this section ambiguous. Sometimes the context helps; for example, “Sal prunella made” (p.27) includes the note that “mounsieur mayhern assured me yt it was also singular good against the stone” – likely a reference to Sir Théodore Turquet de Mayerne (also Theodore Mayhern) (1573-1655). Given his date of death, it seems likely that the recommendation was originally made to Power. Chester has, however, made the manuscript very much her own: it bears the marks of continued use and adaptation throughout, with ink changes, interpolations, crosses, manicules, and evaluative findings like “Proved” and “as I think best” – and even “not exelent” – indicating that recipes were tested, evaluated, and revised.

In contrast, the (mostly) culinary section at the opposite end of the manuscript offers some clarity as to whose voice we are reading. Among the most unambiguous are those receipts Chester claims for herself: on p.60 she confidently asserts “A Tansey as I think best”, presents “my Almond Puding” and shortly after, claims “Orang jumbals” (p.62) as “my own”.

Some recipes are attributed to close relations: her mother (mentioned above), her sister (“To Make Mead sister Flyer” (probably Floyer) (p.56)), a cousin (“A Water for ye Eyes Cosen Parson” (on p.96 at the remedies end). Others are gleaned from wider connections: a “Mr Crouch” knows how to “Make perfume for Bag” (p.57), while “Mrs Scribb” supplies “her Re- for ye yellow Jaundes” (p.55). Among the attributed culinary recipes are several alcoholic beverages (“To Make Chery Wine ye very best”, with marginal note: “Mrs Vincent” (p.58); “To Make Strong Meade. Mrs D” and “Reason Wine Mrs Cudworth” (both p.59)“Cowslip Wine Mr Crofts” (p.79)), fish (“Mr pohtack to dress Eeles” (p.63)), and cake (“To Make a Seed Cake Mrs Neal” (p.81)).

As with her treatment of Power’s remedies at the opposite end, some sections appear to have been copied out en bloc. For example, there are five receipts attributed to “Lad H” (pp.29-33), followed by nine attributed to “E C” interrupted by a single recipe from “Lad H”, two unattributed, and two more to “E C”, until “Lad H” is identified on p.41 in the recipe “To Make Allmond Butter” as “Lady Heart”. An interesting feature of these attributions is that all have been written in a different colour ink to the receipts, indicating that the attributions were added later (or at least, separately).

Among the other clear signs of use are Chester’s additions and amendments. A nice example occurs in the recipe on p.6, “To Make Oringe Marmalade” for which you “Take ye fairest oringes & scour them well wth salt […] for every pownd of oringes allo 3 pd of double refine sugar of which put in half att first with a pint of string jelley maide eather of pipiens or aple Johns”. She has added a note at the end in different-coloured ink: “I sometimes slice all ye peiles & put half a pint more of ye jelly to ye quantitey”.

CONNECTING THE BODY

The tête-bêche arrangement of the volume, which demarcates food and medicine while containing them in a single form, suggests that early moderns understood the holistic nature of the human body. But within that framework some parts of the physical body are accorded their own sections.

A short section on hands (p.51) begins “ye Hands heated”, a condition for which you must take a “handfull of Dock roots […] fayre water […] cow butter”. Hygiene is considered important (“to make ye Hands Cleane”, recommends rubbing “hony” and “yolks of eggs”), as is hand care (a treatment for “Chopt [we assume “Chapped”] Hands” contains a mixture of oil, roses, and wax). There are six receipts for conditions affecting “Leggs” (pp.59-61), notably “Lameness”, which calls for “a black sheeps head with ye wooll on it”, with its “braines & tongue removed”, to create a kind of broth with which to “bath the plaice lame”. Heart complaints, whether it be “payned”, “Diseased”, or afflicted with “ye passion”(pp.51-2), are treated with things such as “rose water”, “gallingale”, “juice of Borrage” “mother of pearls” and rarities like “filings of gold”. The head receives intensive attention, but its various conditions from the psychological to the irritations of infestations are treated in different sections. One group (pp.47-50) brings together several methods of combatting the effects of aging on hair (“Hayre defective”, “to hinder ye growing of gray hayre”, “to make haire grow”) or the

irksome “Nitts in y , and graver scenarios such as “y no fewer than 11 remedies for “ye Head Ach”.

Another batch of remedies (p.39) remains with the head but goes only skin deep: “Face Freckled” requires a simple mixture of “Allom” and “white of an egg” applied like foundation “to anoynt youre face”; to achieve a “Face made fayre”, take “flowers of rosemary & seeth them in white wine & wash you face therewith also if you drink thereof it will make you have a sweet breath”. Other cosmetics include remedies for “Face enflamed”, “face Blistered Red” and a method to have “Bad Blood taken out of the Face”. This latter requires the unfortunate sufferer to “Sett a horsleech or 2 to yor face but it is good to purge before & to direct the worms on the reddest place with a quill or Reed or goose skinn”.

Mental fatigue can be treated with three herbal remedies on pp.8-9 for “Brayn Restored”, “Brain Restored” and “Against forgettfullness”. One of these is to be added to “yr pottage”, another is to be “snufft up your nose” (apparently good for “braine or memory”), and for extra mental stimulation a mix of “Rude red sage mints

oyle of ollives & strong vinegar” requires that you “smoke thereof allso youre own haire burnt”, and it will “qickneth forgettfull parsons”. This remedy can also be repurposed to help “those that be heavy & sleepye” or persons “trobled with the falling sicknes”.

The inclusion of several remedies for memory, greying, and balding tempts one to assume that the scribe is of an advanced age. If that was indeed the case, then this indicates that these particular receipts have been copied out from one of the earlier sources: Power, Raleigh or one of the “antient” authorities, rather than the youthful Chester. That said, “Memory Restored” on pp.72-5 not only dedicates four pages to memory loss, but is emphatically marked out for attention by two manicules at the beginning of the section, suggesting that some people in her household were in need of attention. A lengthy introduction to the recipe claims that “There was by our time att Canterbury a Cannon a Dr of Divinity & allso in the law named Johanes Coletus” who acquired a technique from “a Christned Jew wherby obtained such a marvelous strong memory”. The even lengthier remedy gives detailed instructions, and recommends taking the mixture at first “every 8 weekes once 2 or 3 dayes together”, gradually reducing it to “once when the moone increceth the 3d yeare itt is sufficient once in 12 months & afterwards so long as you live once a yeare”.

Also grouped are treatments for maladies afflicting the reproductive system. For “Flowers flowringe excessivley in “herb Woodipp”, and “oaken leaves eaten” will apparently (p.41); whereas “For the pain & swellings in the genetalls” one should “seeth well the roote of Brasse & make a plaster thereof & put suet theretoo & bind it fast & it will cease the paine” (p.44). To relieve the misfortune of “Gonorhea Palsie”, meanwhile, take “seed of letties powder made into a powder & drank whith water it stopeth the flux yt paseth-forth in ye patients water against his will” (p.45).

PANACEAS

If a specific remedy proved of no avail, or the complaint was more general or less localised, a range of cure-alls were on hand, often employing a large quantity of ingredients. The last great plague ravaged England just over a decade before Anne Chester began to compile her book, and it would still have been a persistent spectre, hence the receipt for “A Cordyale or plauge Water” (p.66). Following the pattern of 17th-century plague nostrums, it gathers multifarious “flowers & leaves”, as if the sheer array of herbs might ward off the dreadful effects of plague. There are some 15 varieties of “Oyle” (pp.80-85) including “Pretious”, “Rue, “Wormwood” and “Saturne” for treating various conditions.

Early modern classics include “To Make Lucatellas Ballsum” (with its “Vertues”) on p.92; and two receipts for salves (“A Salve” and the grander “A Soveraigne Salve”) on p.67 (the latter meriting the whole of the following page for a rundown of its “Excelent effect”). A two-page receipt for “The Lady Hewitts Cordiall Water” (pp.64-5) contains a whopping 60 herbs, to be steeped in “sherry sack […] in a limbeck”, then prepared thus: “to each quart glass of water put ye quantities of Cordials heare expressed”. These include “15 graines of Bezer / 12 graynes of Muske / 10 graines of Ambergreece – half a Drm of flower of Amber half a pound of white sugar candy beaten”, along with “one Dram of flower of Corrall / one Dram of flower of pearle”, combined with the luxurious “4 leaves of leafe Gold a small bag of Saffron”.

PREPARATION, ADMINISTRATION, CONSUMPTION

Much detail is devoted to preparing and applying the remedies. The first group lists six cures for agues, beginning on p.1 with “Agues in Children” (for which you should either administer “powder of Cristall and lay it to soake in wine […] a suckinge Child shall recover” or “Take 3 burr roots & wash them and scrape them seeth them with half a pint of ale and so drink thereof luke warme before the fitt doth come”). The other four contain ingredients such as “iuyce of sorrell”, mixed with “milke” and taken “as hott as can posible bee endured”, or “rosemary sage & mariogolds” together with “bay leaves” and “pepper beeing warme”. Or you can always try “white wine sack or stale beere” mixed with “fresh horse dung” (pp.1-2).

Seven remedies for bleeding include “To stanch blood when a master vine is broke” (p.4), which requires “rawe beef” cooked upon a “gridyron over fresh coales” and laid “to the sore”. When wrapped in cloth it also “stancheth bleeding at nose”.

Of the two remedies for “Brests Sore”, one (annotated “Proved”) mixes roasted “lilly roote” with “Ale with hony”, “whites of eggs & crums of browne” and “turpentine” into a wet cloth and “Lay to ye sore”. Also on p.5 are two drinks for “Brests Encombed”, which call for herbs mixed with wine or water.

Preparing remedies sometimes requires the involvement of animals, never to the latter’s advantage. “Cock Water for a Consumption & Cough of ye lungs” (p.23) recommends that for greatest efficacy one should “Take a runing

Cock pull him alive then kill him”; and to “heale wounds” there is “nothing so excellent […] as ye distilled water of spiders distilled in a strong balnu Balneum” (p.24). The slaughter continues intermittently in a batch of brief remedies for “Frencie in the Head” (pp.37-8), of which the first three are numbered: “1. Take the lights of a Goat & clapp it to the head of the patient. Cureth. 2. Also a spoonge dipt in whight wine warmed & put to the left papp. cureth. 3. Also the root called neproyalle boyled & laid to the head draweth forth all madness”. A fourth claims that “a roasted mouse is very good for the frensy”. More humanely, a subsequent cure employs “luce of smalledye reviver vinegere oyle violets or roses” mixed in a “vessell of glase over a fier”, the resulting compound to be laid “on the patients head itt being first shaven”.

Humankind is also called upon to render material service, but only posthumously: among four remedies for “Falling Sickns” (pp.42-3) each calling for a different collection of herbs, is one specifying that “before the sicknes doe come 2 or 3 dates lett the patient himself provide a hollow peece of a dead mans skull & lett him drink therein”. And it seems only fair that, on at least one occasion, animals appear as antagonists: “Bitten with a Dog” (p.10) requires “Isop” and “rue” boiled in butter, then strained and melted with “wax & roseen” and “put in a box” until needed; the concoction to be applied to the affected area using a piece of lint, “but you must dyet yor selffe with a little barley bread & milk until you be whoule”.

† Pennell, Sara. “Perfecting Practice? Women, Manuscript Recipes and Knowledge in Early Modern England.” 2004. Early Modern Women’s Manuscript Writing: Selected Papers from the Trinity/ Trent Colloquium, edited by Jonathan Gibson and Victoria E. Burke, 2nd ed., Routledge, 2016.

Archives:

Court Book of Manor of Old Hurst, Huntingdonshire. MHD/348. Lord of the Manor: Thomas Fountayne, esq., 1691-1707; Ladies of the Manor: France Fountayne, widow, 1712, and Anne Fountaine, widow 1715-1728.

Melton Hall Deeds. MHD/1-350. Records of the estates of the Fountayne and Montagu families at High Melton, Yorkshire.

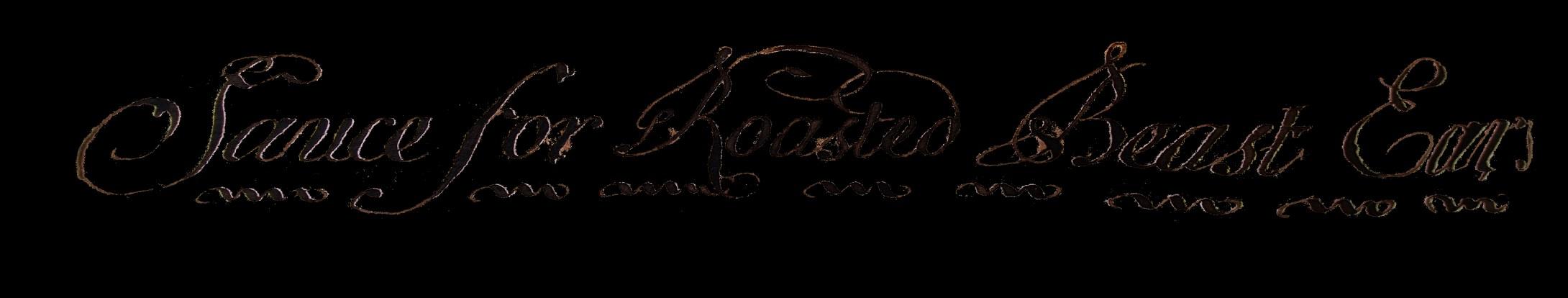

The culinary recipes, too, do not stint on the directions. Among the 12 varieties of “Creame” (pp.8-13), including standards such as “Barley”, “Clouted” “Goosbury”, and “Cherry” (interspersed with a method to “perfume Gloves ye Spanish way” and one to “To Make Gravell for a Sick body”) is an unusual receipt for “A Creame to lay under Snow” which imprecisely calls for “as much Creame as will serve yor turne boyle itt & take as much rice powder as will make itt pap” to which you add “rose water & sugar”, then spice the mixture with “cinamon & large mace”, stir in rosemary “yn lay itt under yor snow lett it be very cold before you lay ye snow on”.

Old kitchen favourites (“Damson Wine” (p.18), “To Pickle Pideons” (p.19), “To Make a Fruggacy” (p.20), “To Collar A Calves Head” (p.21)) are joined by less common recipes such as “To Bake a Red Deare”, for which you must “Take the hanch or side of a stagg & bone it then parboyle it very well” then “take some fat of bacon & cut some lards as long and as big as your little finger lard it very thick”, season it with “a good deal of peper & salt cloues mace nutmeggs and ginger”, and bake in an oven “as hot as for brown bread” (p.22).

More unusual still are directions for making “The Court Perfume”, which instruct the reader to “Take 3 ounces & halfe of Beniamin lay it one night in rose water with a litle goome draggon […] take out the Beniamin & beat it very fine in a mortar”, add “damusk rose leaves […] mingle with a ¼ of an ounce of Civitt mould them together with an ounce of the best duble refine suger”, then “make them into little & thin cake” and “dry ym in ye shade” (p.15). We have been unable to find any perfume with this name, nor even a similar receipt.

CONCLUSION

The social fabric of Anne Chester’s world is inscribed directly onto these pages, revealing not only the networks from which her knowledge came, but the ones she helped sustain. These attributions make visible the embodied labour of women’s knowledge, as well as the distributed, relational way it was shared, evaluated, and preserved.

The manuscript also offers a compelling example of how early modern household books could serve not simply as containers of miscellaneous information, but as dynamic instruments of thought. Its structural features alphabetical organisation, indexed entries, visual cues work to extend memory and scaffold practical reasoning; and its layered authorship and marginalia record evolving judgements and social networks. Its dual orientation to tradition and to lived practice positions it as a manuscript not only for remembering, but for refiguring: a site where authority is attested to, identity is enacted, and cognition is externalised on the page. In this light, it stands as an example of a tool that both reflects and contributes to the mental lives of those who make and use it.

£12,500Ref: 8324

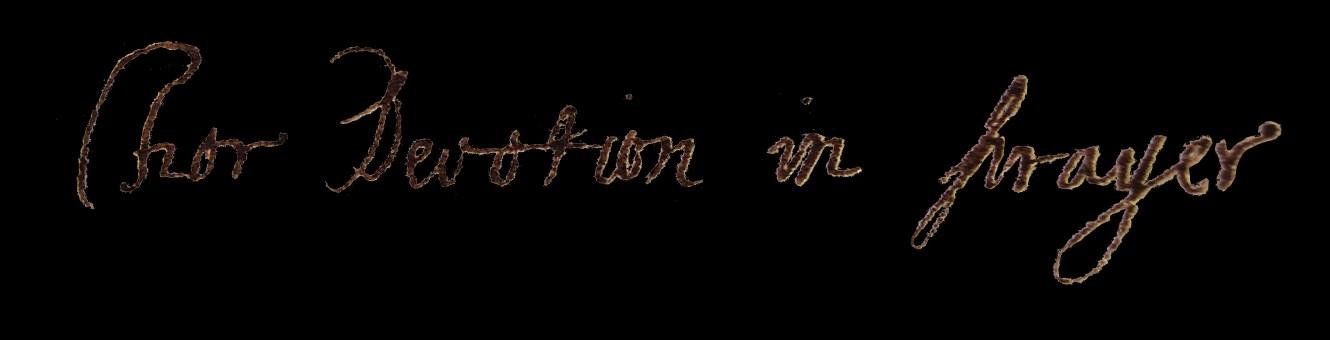

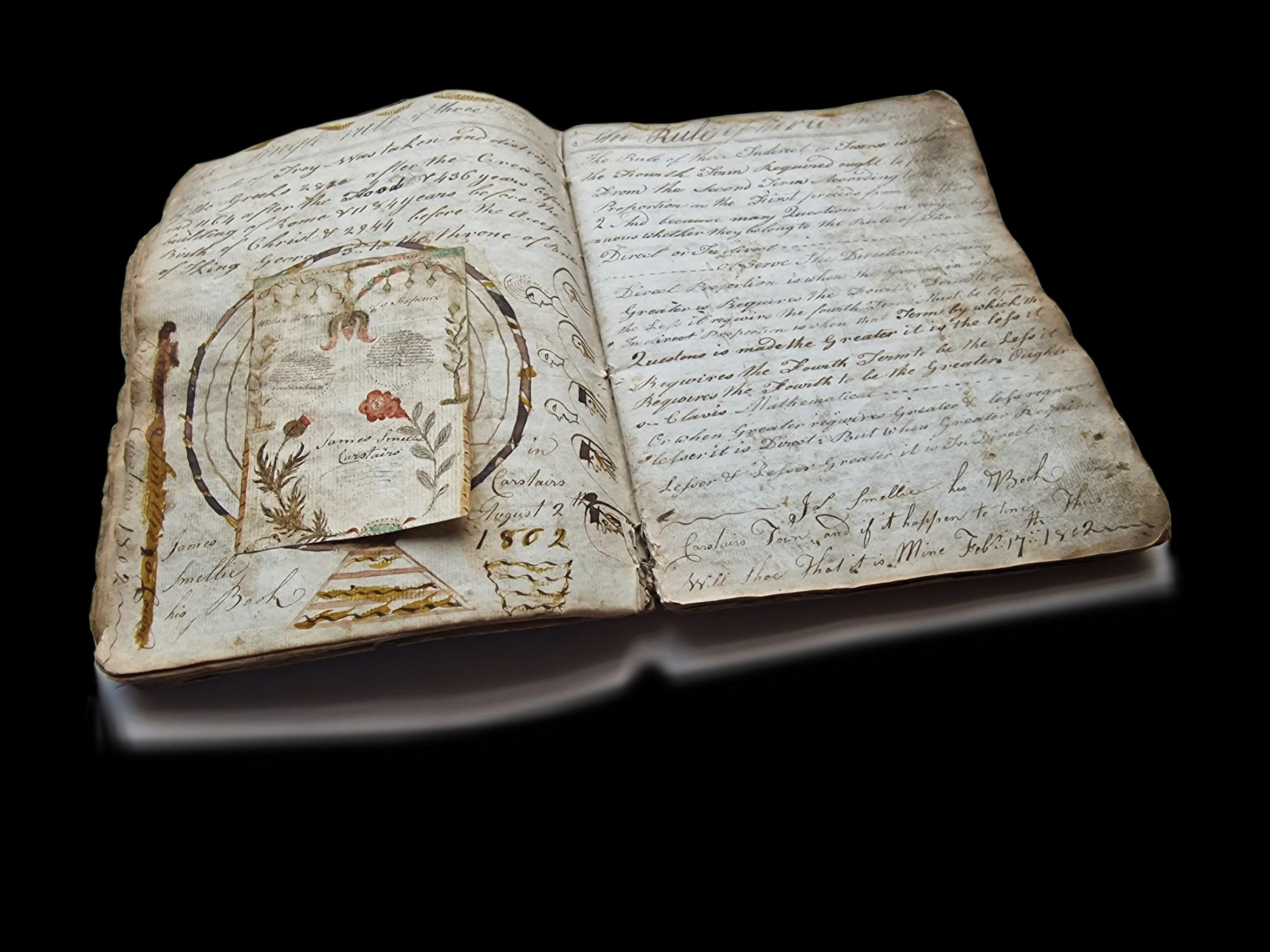

3. THE ART OF

LEARNING

¶ The purpose of rote learning is to embed information through repetition. But whether pupils actually understand what they are copying can be a moot point – hence teachers’ from-time-immemorial direction to ‘show your working’. Early cyphering books record just this kind of classroom instruction, with a pupil’s worked examples

This finely executed ciphering book was produced under the instruction of Stephen Barrett, schoolmaster and clergyman of Ashford, Kent. It records the progress of one of Barrett’s pupils, who carefully copies out the lessons of arithmetic, geometry, trigonometry, and surveying. Its structure follows the sequence of a complete mathematical curriculum: from first principles and definitions, through plane and solid geometry, trigonometry, mensuration, and surveying, including practical applications such as “Board and Timber Measure” and “Measuring Carpenters, and Bricklayers Work”.

¶ [BARRETT, Stephen (1719-1801)].

18th Century Mathematical Manuscript, entitled ‘A Plan of the Mathemats, The Revd . Mr Barret’s Ashford 1760’.

[Ashford, Kent, 1760]. Folio (324 x 23 x 13 mm). Title page and approximately 159 pages of text and calculations on 90 leaves. Bordered throughout, and pages numbered to p.162. Vignette title and five topographical vignette head engrisaille, in watercolour.

Contemporary calf-backed marbled boards, rubbed, small area of loss to spine.

Watermark: Britannia; Countermark: LVG (i.e. 18 th century Dutch papermaker, Lubertus van Gerrevink). (Haewood 201,circa 1765).

Stephen Barrett attended grammar school in Skipton, where he is said to have excelled in poetry and classics. He matriculated at University College, Oxford in 1738 and graduated BA in 1741 and MA in 1744. Having taken holy orders he became rector of the parishes of Purton and Ickleford, Hertfordshire, in 1744. He was a friend of Samuel Johnson and Edward Cave, and a frequent contributor to the

significantly elevated the school’s reputation, yet surprisingly little of his pedagogical work seems to have survived. There is a single commonplace book, now at the Beinecke Library [Osborn c193], recorded as “Autograph MS. Original poems dating from 1736-ca.1794”. Against this backdrop of scarcity, our anonymous student-produced “Plan of the Mathematicks” offers rare, first-hand evidence of the curriculum delivered in Barrett’s classroom, showing what was transmitted, copied, and internalised by those he taught.

but the finished object is above all reflective: a record of what had been learned, not a space for experimentation or interaction. Several blank leaves, unfinished sections, and missing theorems hint at an incomplete rendition of the whole curriculum, at odds with the general level of dedication displayed in the transcription.

The neatly executed illustrations lift the manuscript beyond simple didacticism. Mensuration examples, geometrical solids, and diagrams are neatly executed and shaded with attention to proportion and perspective (including several fine examples of towers rendered in miniature). Headpieces depicting landscapes introduce some sections, treating mathematical training as an arena for artistic as well as cognitive display, and underscore the degree of labour, intention, and pride invested in the work.

The structure of the text mirrors a fixed curriculum rather than shaping new intellectual order; indeed, its purpose was to record and memorialise the content of lessons rather than scaffold ongoing problem-solving. Nonetheless, the very process of copying out, diagramming, and ornamenting reveals how 18th-century pedagogy treated transcription as an act of cognition. What we see here is not a young mind in the flux of reasoning, but a record of that mind’s consolidation of learning.

£1,500 Ref: 8364

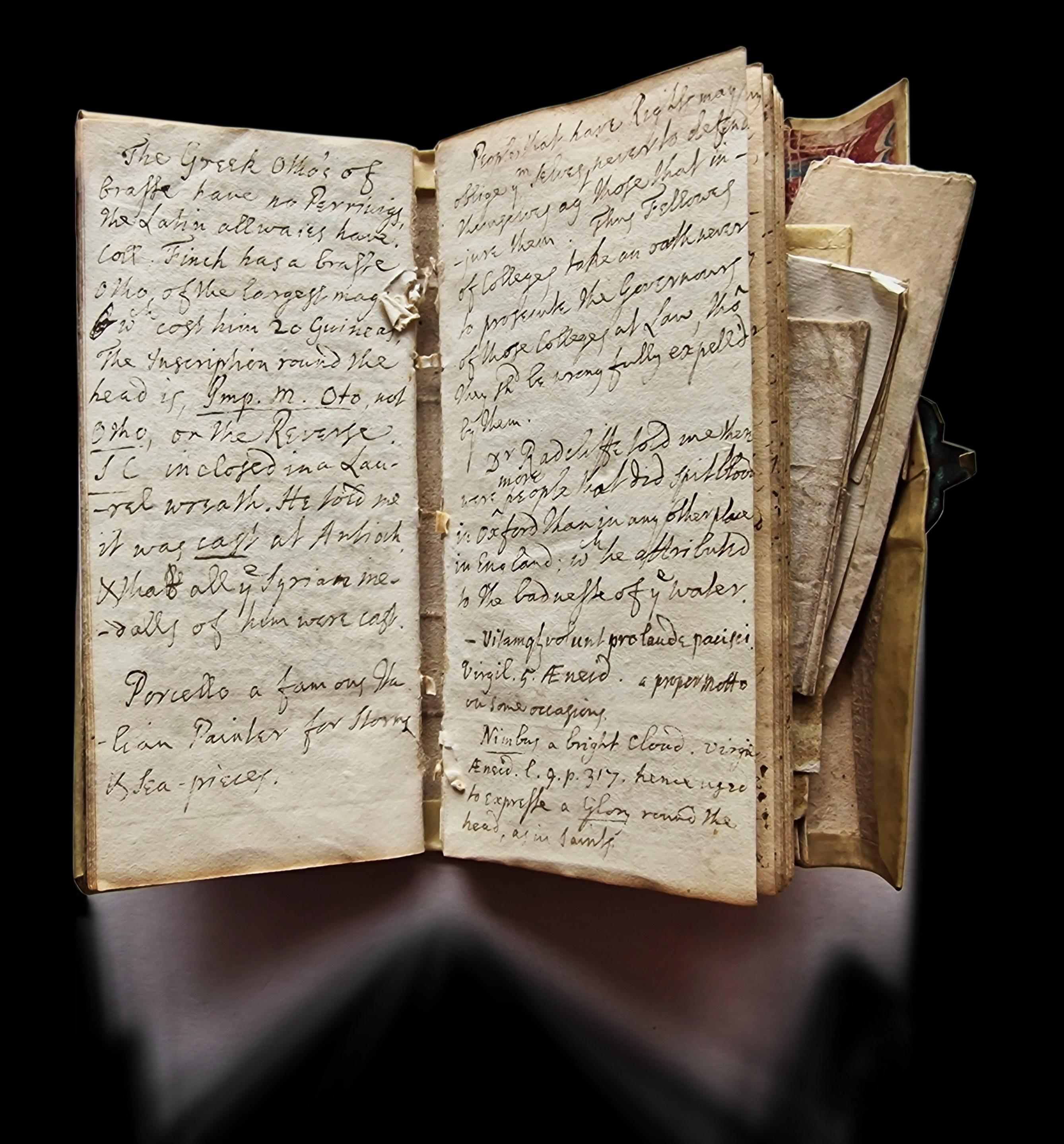

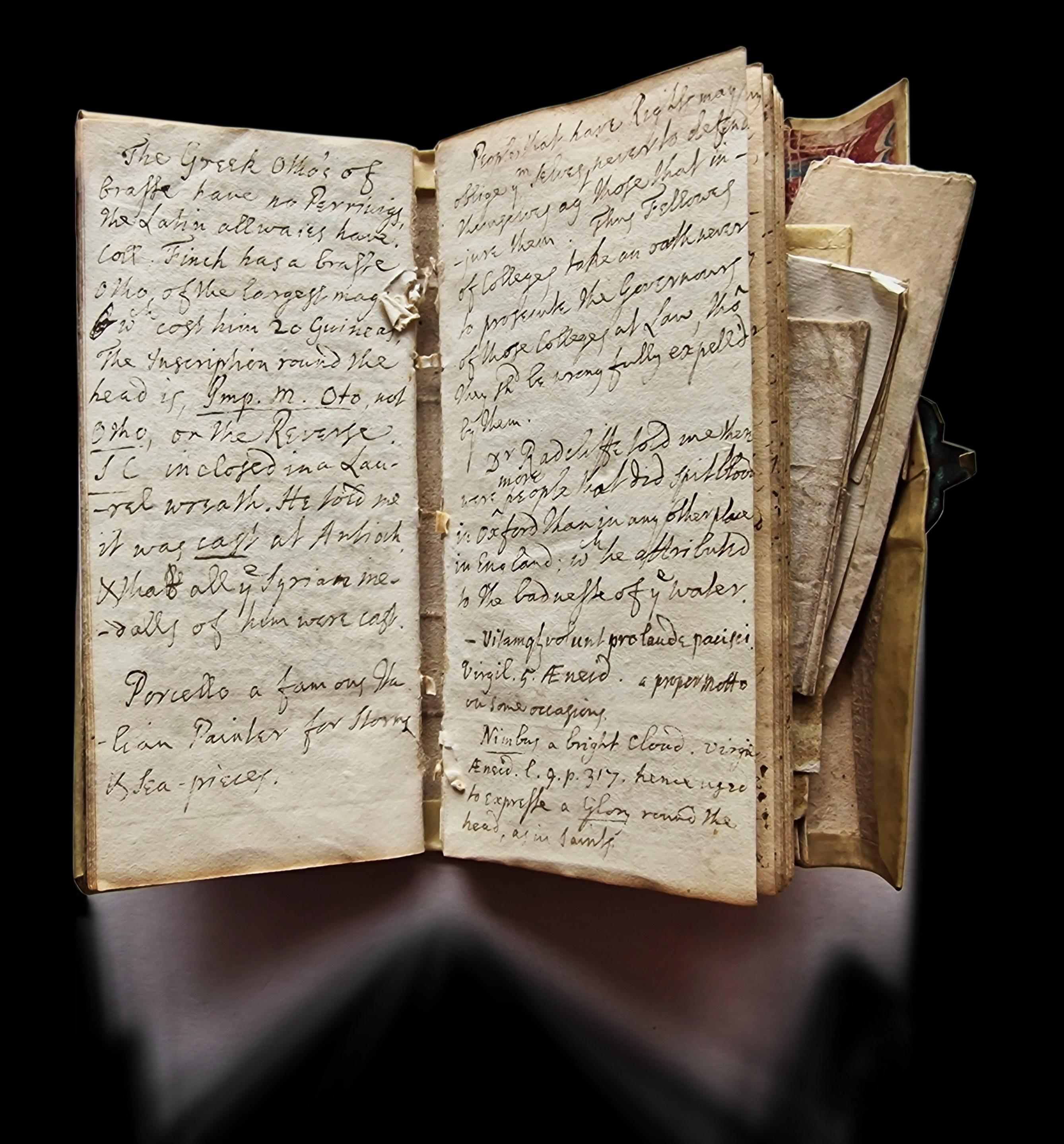

4. COMPACT CONVERSATIONS

¶ Overheard remarks, fleeting anecdotes, spoken exchanges – such saltatory snippets can animate our understanding of centuries-old social history if one of the interlocutors has thought to write them down (and happenstance has preserved them). They can also help to bring nuance to the character of a scribe, particularly if, as in this case, they are better known for writing histories and genealogies and transcribing antiquarian texts.

The scholar, librarian and nonjuror George Harbin has intermittently recorded his day-to-day interactions with a range of his peers and acquaintances, interspersing these memoranda of personal encounters among his more customary transcriptions from other texts.

There can be little doubt that Harbin carried this neatly clasped little book with him, likely tucked into a pocket. Carried around in public spaces yet kept close to the body, pocketbooks function as intimate tools for selfwriting and self-formation. Their compact form shapes how we record, organize, and interpret information, which in turn may influence our self-perception and alter

¶ HARBIN, George (c.1665-1744). Early 18th-CenturyManuscriptPocketbook.

[Circa 1710-11]. Oblong octavo (160 x 70 x 7 mm). Approximately 55 text pages (50 at one end, 5 at the other) on 30 leaves, one blank endpaper excised. Five loose leaf notes and documents tucked into letter pocket.

Contemporary vellum, wallet-style binding, with letter pocket at oneend,clasp intact.

ATTRIBUTION

Among several documents tucked into the letter pocket of this little volume are two – one paper, one vellum, perhaps scribal copies – relating to George Harbin’s (c.1665-1744) time at Jesus College; another, which gives sketches of his life, is signed on the other side “A: Malet”. This is presumably Rev. Alexander Malet (1704-1775), Harbin’s executor, and to whom his manuscripts passed. The note was written after Harbin’s death, and as there are no ownership inscriptions in the volume, it is a key piece of evidence for identifying our scribe. These documents, coupled with comparisons of the hand against other Harbin manuscripts, secures our attribution.1

George Harbin graduated BA from Emmanuel College, Cambridge in 1687, and migrated to Jesus College the following year. Having been ordained as chaplain – first to Francis Turner, bishop of Ely, then to Colonel Sackville Tufton in Northamptonshire – in 1699 he entered the service of Thomas Thynne, first Viscount Weymouth, becoming his librarian (his status as nonjuror disqualified him from the role of chaplain after the act of 1702 imposing the oath of abjuration). In 1710 – roughly the date of this volume – he drew on his extensive reading and assiduous manuscript-copying to publish The English Constitution Fully Stated (a riposte to William Higden’s View of the English Constitution (1709)); in 1713, The Hereditary Right of the Crown of England Asserted appeared anonymously, only years later identified as Harbin’s work.

BOOKS, LIBRARIES, CHATS

Harbin was evidently a highly sociable individual, and his pocketbook treats encounters with people as seriously as those with books. As if mixing at the same gathering, passages from printed and manuscript works (“Apud Rymer Fædera”, “Dr Tod’s Notitia Dioces. Carlolensis”, “Camden’s Eliz. A.D. 1577”) mingle with snatches of chat and anecdote. He relates hearing from “Dr Radcliffe” (probably the English physician, academic and politician John Radcliffe (1650-1714)) that “there were ^more people that did spit blood in Oxford than any other place in the England: wch he attributed to the badnesse of ye Water” (f.10r); and in an account of a conversation about printed maps, he writes: “Mr Johnson also shew’d me a Map of Moscovy, wch he said was given him by Mr Lock, and was a very great curiosity; none of them now to be had. It was made by one Monsr Witsen” (f.21v).

Books and libraries are a frequent topic, occasioning a few digression-heavy narratives; on “May. 1st”, Harbin “met wth Mr Toland in Mr Harley’s Library & asked him about Spaccio della bestia trionfante a bopoke written by Jordanus Brunus in 8vo he told me he did lend it for 3 or 4 hours to Monsr la Croze (as he owns in his Entretiens sur divers sujets d’histoire p.327) & that only for a Copy of this book he had a present made him of 50 Pistolls ^ by Prince Eugene of Savoy. He assured me this book was Printed in London by an Italian Printer … Mr Ch. Bernard gave 16 Guineas & at ye Auction of his Books, it was sold to Mr Clavell of the Temple (April 1711) for 28 pounds” (ff.11v12v). Particular volumes are discussed almost as though they are people: during a chat with “Dr Grabe” (presumably John Ernest Grabe (1666-1711), chaplain of Christ Church, Oxford), Harbin hears that his

august companion “never cd meet wth Lloyd’s Greek Edition in 12 Josephus περι αὐτοκρατορος λογισμου tho’ he searched for it in all The Libraries of Oxford, and that at Lambeth. That piece was printed from a MS in New College Library, but it has been printed by the Jesuite Comfetis & is in MS likewise at the End of the Alexandrian LXX” (f.11r).

The “Jesuite Comfetis” is likely François Combefis (1605 – 1679),2 whose publications included Flavii Iosephi De imperio rationis : in laudem Maccabaeorum liber (1672) and Φλάβιου

Τα εὐρισκόμενα (1691).

In a political anecdote, perhaps appealing to the nonjuror Harbin’s sense of principle, he writes: “Dr Sheridan, the Deprived Bp of Kilmore told me (May 20th 1711) that he was present at the execution of Sr Phelim O Neale in Ireland, for being the Chief Actour in the Irish Massacre”, and that, having been offered a reprieve in exchange for a declaration that he was effectively coerced “by vertue of a Commission” from “K Charles 1 O’Neale replied that “he wd not save his life by so base a lye” (ff.18v-20r). It may be an effect of his sheer conviviality that Harbin blithely follows this with an account of a conversation on the same day with a Johnson of Twickenham”, who informs him “that wee spoil our Peeches in England by letting them hang close to a brick wall, whose heat in summer is so great, that they are dryed up in a manner, and ys particularly affirmed to be true of the Mignion Peech, wch is very delicious in France, but of no great value in England” (f.20v-22v).

Another exotic but ill-fated specimen is profiled a week later: “May 26 1711. I saw at Burlington-house in Picadilly a Strange but very beautifull Bird wch had been lately brought by Captn. Coleman from Guinea, or the Country thereabout. It was of the bignesse of a tame-pidgeon, wth legs & clawes much like one from the head, to half of the body, the middle of his back, together wth ye breast, it was of a darke purple. The bill was very short & of a dark red colour. The head was crested, as a Cockatoo from y end of the bill to the hinder part of the head”. Harbin has, however, added a later note at the top of the page in different-coloured ink: “The under mentioned bird dyed at the beginning of the following winter” (ff.22v-

CONCLUSION

Fragments of early-18th-century conversation have been snatched out of the air and captured in this tightly clasped pocketbook, giving physical form to passing utterances and enshrining – along with some enjoyable digressions – among the literary transcriptions for which Harbin was renowned. In doing so, he assigns equal weight to written and to spoken material, presenting both as part of a continuum of reflection and a structure that helps him to form his own thoughts.

Its compact form is not incidental but integral. This pocketbook both expands and contracts the scope of memory. Its portability allowed encounters to be written down at once, expanding the temporal window of what could be captured, but its small format constrains detail, funnelling experience into compressed notes rather than extended narratives. The result is a record that is at once briefer and more immediate, framing how memories are formed, internalised and revisited.

£3,250 Ref: 8366

1. Library holdings include: Beinecke Library [OSB MSS 299].Northamptonshire Record Office [FH 281 . RoJ

The Marquess of Bath, Longleat House, Thynne Papers, Vol. XXVII. British Library [Add. MS 32092; Add. MS 32096; Add. MS 32095].

Somerset Records Office [DD\HN].

Phillipps acquired some the manuscript collections of Harbin [4801-4911; 10658] en from the English diplomat Sir Alexander Malet (1800-1886), descendent of Harbin’s nephew and executor Rev. Alexander Malet (1704-1775).

2. We are extremely grateful to Christopher Whittick for this information.

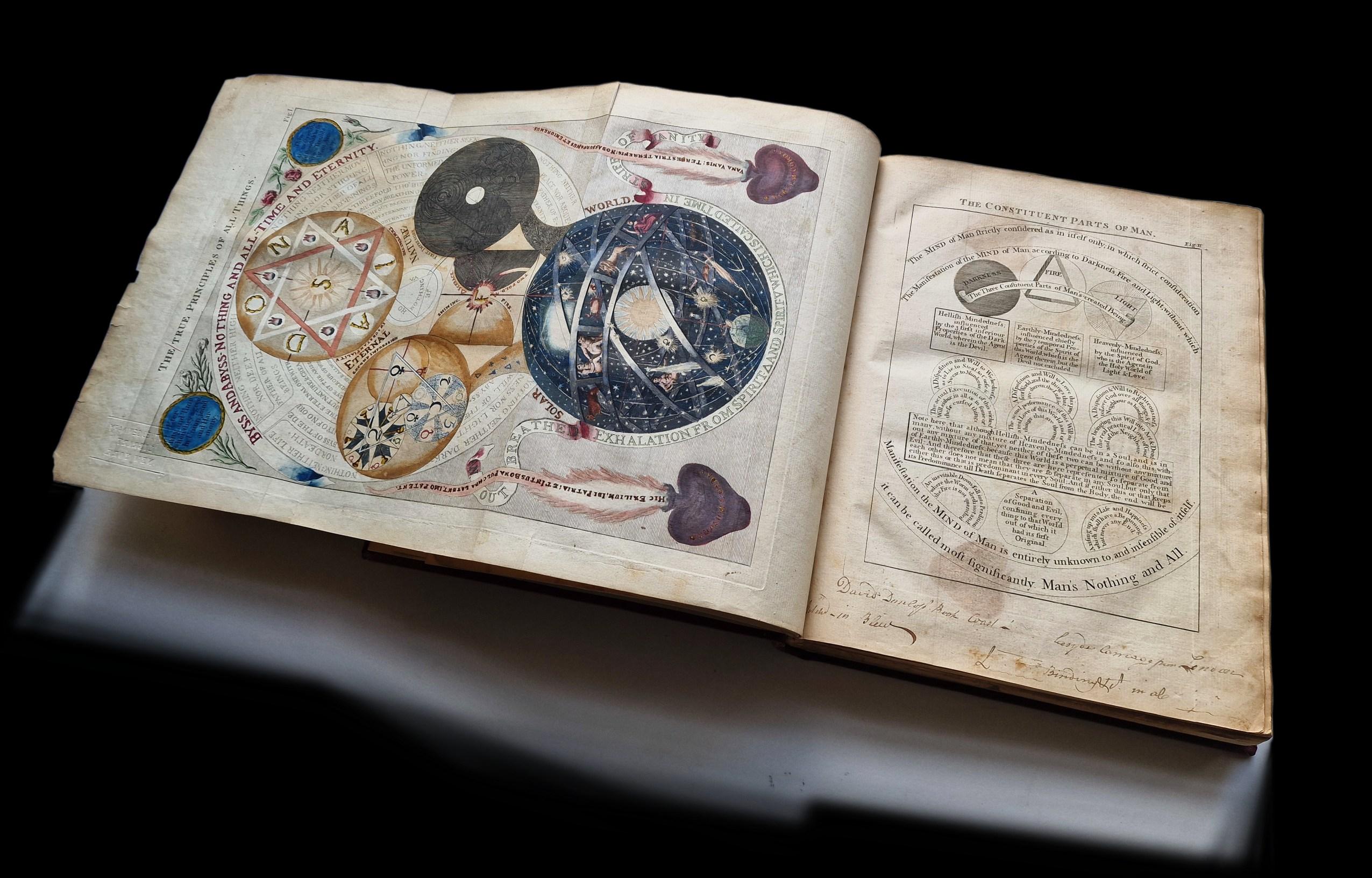

5. BOEHME ME UP SCOTTY!

¶ From affirmation and validation of thought and experiences to the birth of a second spiritual self, the zealous annotator of Jakob Boehme’s mystical writings records his remarkable bifurcation to create a kind of spiritual avatar (with possible allusions to Hermes), accomplishing his own alchemical Magnum Opus.

In over 600 marginal and interleaved annotations, clipped engravings, and handdrawn images, the scribe a Scottish merchant and shipmaster conducts an onthe-page dialogue with the text, shaping his own thought in the process – and invoking a third participant in the conversation.

COMPOUND AUTHORSHIP

Jakob Boehme (1575-1624) was a German Lutheran shoemaker turned visionary whose theosophical writings (following a profound mystical vision in 1600) provoked ecclesiastical censure but continued to circulate widely in manuscript and print. His work inspired many writers and thinkers, including German Romantic philosophers (Hegel considered him the first German philosopher), religious radicals, and poets, among them William Blake, John Milton, S. T. Coleridge, and W. B. Yeats. These four volumes collect English translations of his many treatises, including Aurora, The Three Principles, The Mysterium Magnum, and The answers to forty questions concerning the soul. They are lavishly illustrated with numerous engraved emblematic plates some with moveable onlays intended to reflect Boehme’s visionary quality.

¶ BOEHME, Jakob (1575-1624); Annotated by David DUNLOP (d.1793). The Works of Jacob Behmen,TheTeutonicTheosopher.

M. Richardson [-G. Robinson], 1764-81. First collected editionin English.

Bound in maroon library buckram, ink and blind library stamps (General Theological Seminary), page edges a little brittle, folded plates in volume I torn alongfolds and loosely inserted.

Pagination [vol. I]: xiii, [3], 22, [2], 23-269, [7], 301, [21]; [vol. II]: [4], 195, [37], 120, 160, 32; [vol. III]: [2], 507, [27], 37 [1]; [vol.IV]: [8], 8, [2], 9-297, [3], 218 (this section with errors in pagination, but appears complete), [8], 156. Plates: [vol. I] 4; [vol. II]. 15 plates; [vol. III]: 3 with moveable onlays (one of these laid down to sheet); [vol. IV]: 3 (including hand-coloured, folded plate). Half-title to volume IV only. Lacks frontispiece to volume I, and one other plate.[Caillet 1289].

Extra-illustrated with 12 small inset engravings pasted to margins of volume I. Extensive annotations and ink notes to margins in a contemporary hand.

Attribution of the extensive marginalia is made to David Dunlop (d. 1793), a merchant and shipmaster based in Irvine, Scotland, whose name appears repeatedly in the annotations. Several entries confirm the impression of a Scottish scribe with maritime connections: a passage dated 3 December 1782 places him “at Irvine Quay and William Shelly as just getting up in Harbour Syde or State room in said Cabbine when this was reveald to me last year at Edinburgh when attending the Courts as at present and I think in same month Novr or Decr 1781” (Vol. III, p.175). Dunlop frequently cites locations in this way, naming specific ports, roads, and churches, and especially when recalling spiritual experiences. For example, in response to Boehme’s printed text: “the sensual divine Understanding, a Tongue tinctured from the divine Ens of five Vowels” he writes in the margin: “now I saw a Toung come up from the Lord within me plain to Behold. in 1774 near to a Dock in Corke Called Hairs Dock” (Vol. II,

A reference to his wife and son reinforces our attribution: “William Dunlop the second son that was Conceived in Ann Kelly my Earthly Wiffe” (Vol. II, p.115) corresponds to a record of William Dunlope’s birth on 27 August 1750 at Irvine, Ayrshire to David Dunlope and Anna Kellie. Further offspring of David Dunlop and Anne Kelly (sometimes spelled “Keltie”) appear in the records: Andrew Dunlope, born 19 February 1757 at Irvine; Anne; George; Sallie; and Stevensone, born 5 February 1761 at Irvine.

THE NEW MAN AND AVATAR

What sets this copy apart from many other annotated books is the emergence, within the marginalia, of a second identity: “Davie Delope” (also spelled “Delape”, “Delop”, or “Dalope”). More than merely a pseudonym, “Delope” appears to be a mystic, spiritually reborn persona, something Dunlop affirms in the first volume: “David Dunlop now Davie Dalope” (Vol. I, p.98–99). In places, the scribe writes as both, oscillating between these co-existing identities. Delope seems to represent the fruit of Dunlop’s mystical transformation: in one telling gloss, Dunlop notes that the experiences he describes are “Experimentalie known to David Dunlop yett by David Delape the new man within the old” (Vol. I, p.83).

The name Delope while orthographically unstable may derive from Dolops, the mythical son of Hermes. The connotations here are twofold: in the Greek myths, the Argonauts and other sailors would make sacrifices to Dolops

for protection at sea; and Dolops, through his paternal association, is also tied to Hermes Trismegistus, the syncretic originator-god of Hermeticism who deeply influenced many strands of Western esoteric and mystic philosophy. Given Dunlop’s maritime background and the Hermetic resonances of Boehme’s mysticism, the name’s adoption is suggestive: Delope as both spiritual sailor and esoteric heir.

TRANSFORMATION AND VALIDATION

The volumes are visually arresting: four large quartos packed with dense esoteric printed text, moveable engraved plates, and abundant inked marginalia, pasted‑in engravings, and hand‑drawn emblems. Dunlop/Delope uses Boehme’s printed text as a dialogue partner, annotating to record, reflect upon and affirm personal revelations. One of the most striking features of his airy visions is that so many are precisely dated and tied to physical locations, almost in the manner of a ship’s log: for instance, “on a Alter in a Stone wall Church up a Hill near Passage west Syde of Cork river in Iearland 1774. about advent Sunday December” (Vol. II, p.145); “this was done to David Dunlop on Eighth of August 1784 whyle resting near a Park gate” (Vol. I, p.40); and “this is truly So how high was the Church Shewen me when I was sitting in Markes Church in Dubline. 1775” (Vol. III, p.173). Such levels of detail reach a peak of vividness in his description of a Christophany that occurred “on the road Kilmarnock”; Dunlop/Delope writes that he has “seen yea the Lord himself with the wound in his Syde and Blood on his Bodie and seen him coming down from Heaven and on the Cross & of the Cross in Cloaths and Wrapt in Linnent his right foot out and on the road his right arm out stretched […] and often angels. and the new man and the New wooman within me Duelling under the Shadow of the rock of Ages” (Vol. I, p.65).

The annotations often respond to Boehme with direct experiential affirmation. In response to the printed text “plucked the pearl from his Hatband, and his Hatband broke; and then he became as another earthly Man, and none saluted [reverenced or regarded] him”, our scribe declares, “this is agreeable to what was shewen me last night 14th of Septr 1782”. (Vol. I, p.177). In another passage, Boehme writes “there is the Power, and in the Power is the Tone or Tune, and rises up in the Spirit, into the Head, into the Mind”, to which Dunlop/Delope responds, “this I have Experienced in right & left Ears like a Chime of Bells” (Vol. I, p.47). This auditory trope reverberates again in “The Voice of God’s Anger, which forced into Adam’s Essence … the Tone or Hearing of the Dark World did sound [or ring its sad Knell]” – affirmed by Dunlop/Delope’s experiential report, “and this bringeth to mind the stroak of a Mighty Bell in left Eare in Scotland. 1774. & in Scotland. 1776 in left Eare like a Chime of Bells, and in a little time some few Stroakes in my right Eare in Scotland near Lord Glencairnes betwixt Inshannan Bridge 1776 or the troops Embanked for America” (Vol. III, p.101). In numerous passages, Dunlop/Delope assigns great authority to Boehme’s accounts, seizing on them for validation for his own experiences; declaring in one passage, “Isiah XXIX. 23 when thy Discern See their Children the worke of my right hand in them […] they that had an Erroneous Spirit in them shall gett understanding and they that were Scornfull shall learn Doctrine – this is just what god by Jacob Behemen mentioneth was at hand. and to me it has been Manifested or reveald & Seen. D. D.” (Vol III, p.152).

TRANSMUTATION

Dunlop’s invocations of “the new man within the old” may seem metaphorical, but his passionate embrace of Boehme’s alchemical worldview suggests otherwise. In traditional alchemy, transformation is commonly described through three emblematic stages: nigredo(blackening), albedo (whitening), and rubedo(reddening). In the laboratory, these terms referred to the visible processes of putrefaction, purification, and the final creation of the philosopher’s stone (the symbolic Magnum Opus of alchemy); but they also served as parallels for the soul’s inner work. Nigredo marks the decomposition of form and the descent into conflict and dissolution; albedo follows as purification, a clarifying of substance or spirit; rubedo completes the process as unification, perfection, and reintegration of the reborn self.

Boehme reinterprets this triad within his theosophical cosmology as the soul’s passage through the divine drama of creation: from the anguish and division of the dark world, through the inward breaking-through of divine light, to the fiery rebirth of the spirit in Christ’s likeness. This final state is marked by love, divine wisdom, and full alignment with the will of God. For Boehme, the soul’s regeneration is no metaphor it is a cosmological reenactment, an echo of creation itself. Viewed in this light, Dunlop’s annotations become not just devotional glosses but a lived alchemical record of descent, illumination, and rebirth, culminating in the emergence of a “new man within the old” – his own Magnum Opus

Dunlop chronicles his spiritual decomposition (nigredo) through visions of strife and hardship in several passages: for example, “yett often Since has the Divill appeared and raged against me since Driving to Dispair and Many Artful things Done to Deceive and Drive to Dispair” (Vol. I, p.40); and “This Battle was fought in the Spiritual world within David Dunlop / this I Saw and the men were like as prists in their Cloathing Black with Banns and Black gowns” (Vol. III, p.158); and “thou has a Vew in this letter what was caste out of me in the Rage of iniquitie” (Vol. I, p.221).

He describes his purification (albedo) through theophanies such as “Some time Calm o god of Hosts the mightie Lord; how lovely is the place whear thos Enthroned in Glorie Shewes the brigh[t]ness of thy face” (Vol. I, p.40); “I often have Ocular Demonstrations off by seeing Clouds of Gloryous Light Skimming around & before me” (Vol. I, p.45); and “this I. D.D. have Experience of seeing God face to face as is hear mentioned on the light of August 1784 it being on a Sunday” (Vol. II, p. 91).

Finally, the transformative reintegration of the self (rubido) appears through experiences of salvation and rebirth and the appearance of a ‘second self’: “it is a sore travail, the pains & pangs of being Born Again. yea Excruciating pains is attested by D. D. from Experiencing same so has it been with Jacob Behmen” (Vol. IV, p.268); “we know that Jesus Christ is the power of godlie Wisdom of God and is become the Rock of our Salvation – David Dunlop now Davie Dalope” (Vol. I, p.98-99); “looking up and seeing in the north whear the light is truest Experimentalie known to David Dunlop yett by David Delape the new man within the old . truth. Da: Delope” (Vol. I, p.83).

Dunlop also picks up on a specific reference by Boehme to the philosopher’s stone (the symbolic Magnum Opus of alchemy): “The Noble Philosopher’s Stone was as easy to be found by him as other stone, and then he might have adorned the outward life with gold, silver and precious Stones, Jewels and Pearls”. This passage is marked “^” in the text, and annotated in the margin, “now as I lay in Bed in my Roome covered with flowered stained paper this Change hear noticed to be done by the Noble Stone; then flowers was changed and like unto Embrydered Silk with Gold or Silver flowers richly wrought in the same. this is attested by Da: Delape”. (Vol. II, p.112). The motif of the “new man” and “new wooman” recurs, sometimes related to pasted in engravings (such as that in Vol. I, p.171) that visualise the internal metamorphosis.

These volumes can be read as a record not only of mystical experience but of transformation through the act of reading. Dunlop finds in Boehme not just insight, but companionship and affirmation a voice that makes sense of his own visionary life. By writing in the margins, he holds a dialogue with the text that both shapes and chronicles his own profound transformation.

CONCLUSION

These unusual interactions offer remarkable evidence of mystical experience grounded in everyday life: at quaysides and park gates, in ship cabins and Scottish and Irish churches. In Dunlop/Delope’s hand, Boehme becomes something more than a mystical philosopher he is a companion, a guide, a catalyst for the birth of “the new man within the old”.

This is a work of three authors: the visionary mystic Jakob Boehme, the Scottish shipmaster David Dunlop, and the alchemically reborn Davie Delope – a trinity of voices that produce a documented spiritual metamorphosis unfolding in dialogue, page by page. Their collaboration across centuries, media, and identities results in an extraordinary document of spiritual practice, experiential annotation, self-writing and self-fashioning.

£7,500 Ref: 8334

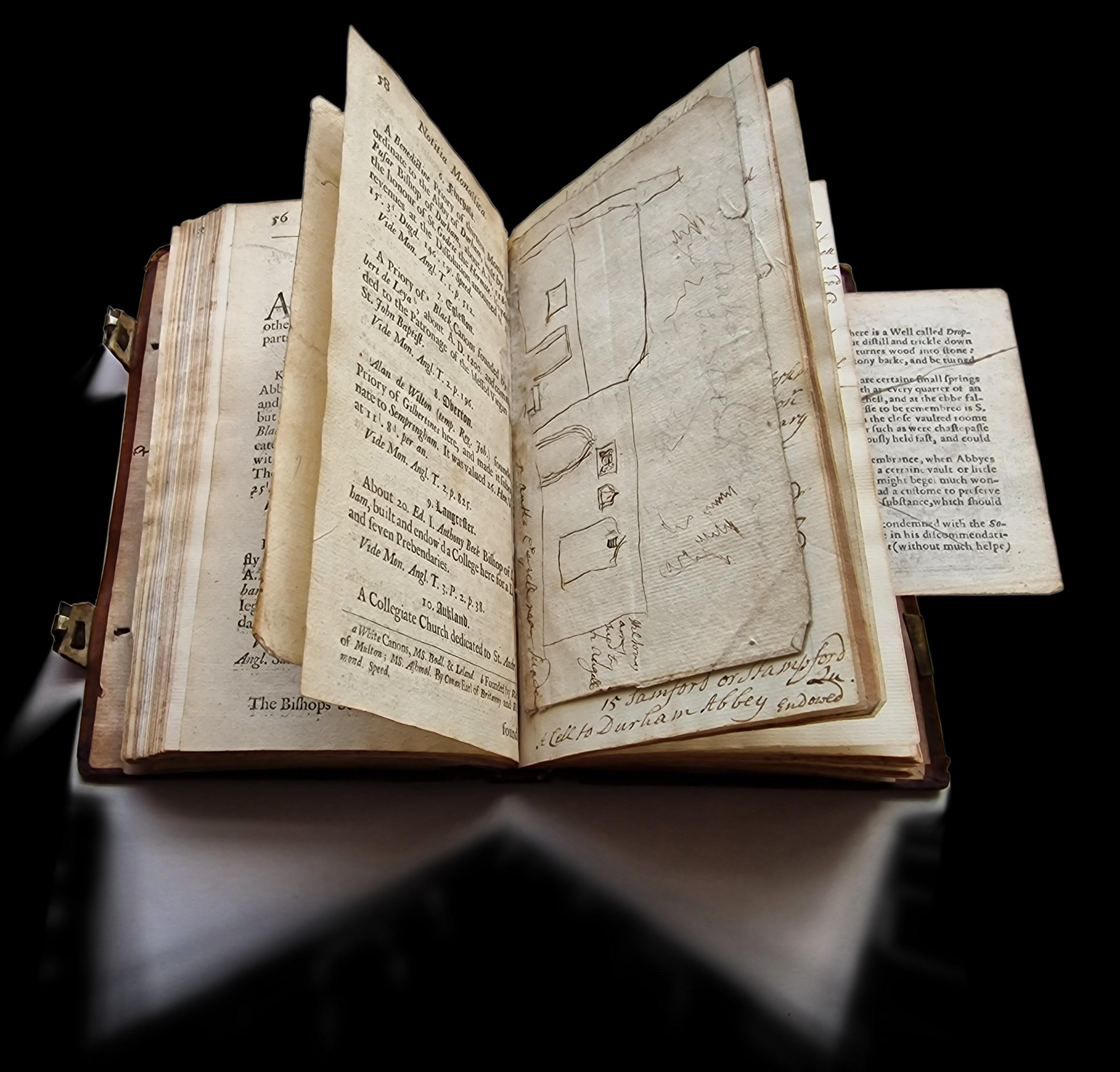

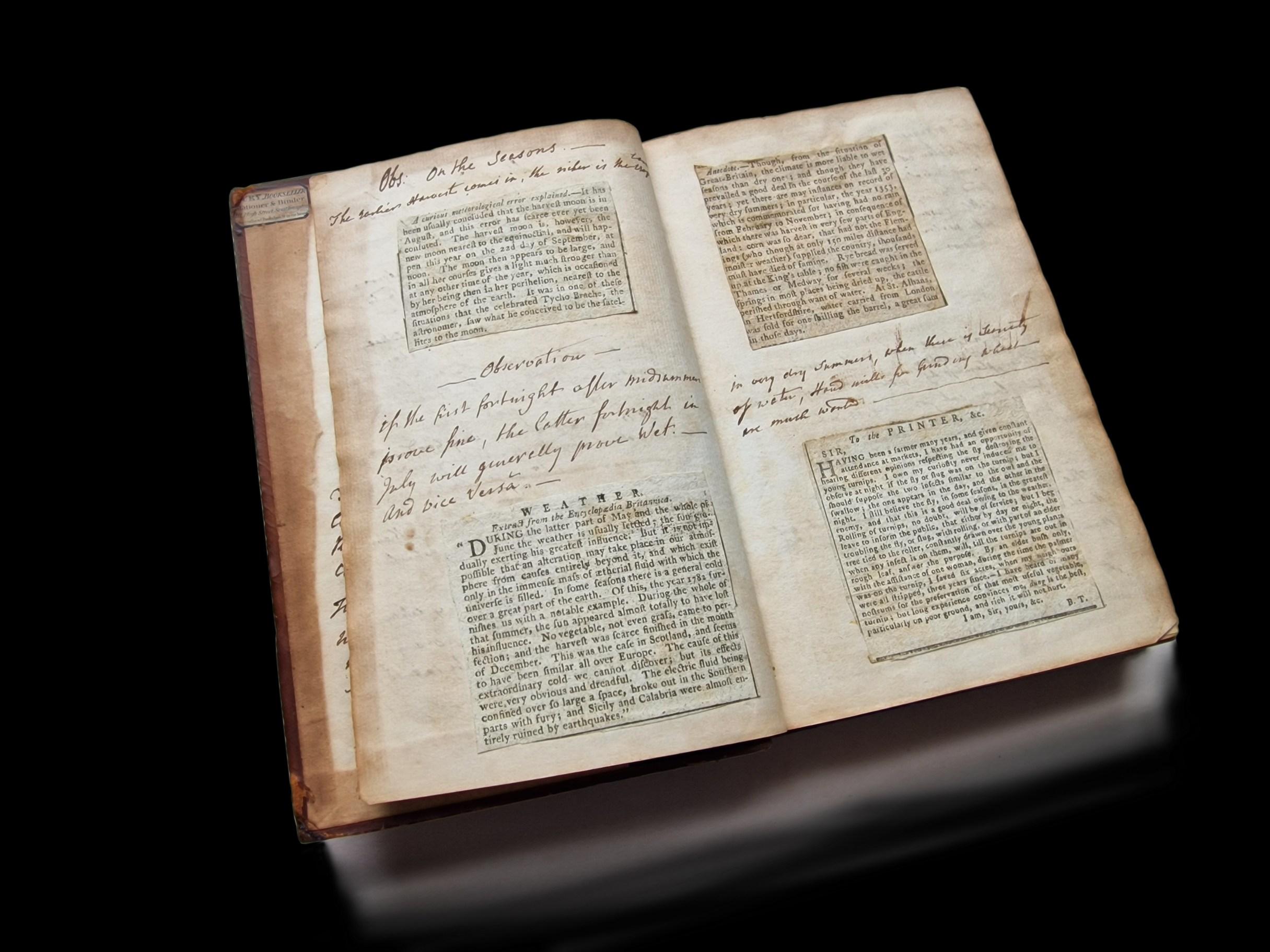

6. HYBRID HISTORY

¶ Despite its hybrid form and clear evidence of interaction including inserted maps, armorial sketches, and architectural sketches this manuscript is reflective of its compiler’s thoughts rather than formative. Its structure preserves existing orders of knowledge, and its interventions aim at completeness and coherence, not transformation. The manuscript thus functions as an instrument of historical reference rather than of intellectual development.

It was compiled by Edmund Lamplugh Irton (1762–1820) of Irton Hall, Copeland, Cumberland. Edmund, the eldest son of Samuel Irton and Frances Tubman, matriculated at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1780. He married twice, and his eldest son Samuel inherited Irton Hall following his death. The Irton family resided at the Hall for over 600 years until its sale in the mid-19th century. Edmund’s fine library was sold by auction at Irton Hall circa 1853, and later in Keswick.

¶ IRTON, Edmund Lamplugh (17621820) HybridTopographyNotebook.

[Circa 1790]. Octavo (176 x 110 x 10 mm).

bound in reversed calf with scorching close to the spine; rebacked in modern reversed calf with a new label. Working clasps hanging from the upper board; the substantial print and manuscript extracts are followed by around 60blank leaves.

Irton’s notebook constitutes the beginnings of a county history of Durham, with manuscript and printed extracts from the 17th and 18th centuries drawn from topographical descriptions, ecclesiastical history, and incumbents of monasteries. It includes excerpts from a dozen printed volumes among them pp.45-48, and folding map, extracted from Robert Morden’s The New Description and State of England, (1701); pp.509-536, with 2 page manuscript continuation from Browne Willis’s Mitred Parliamentary Abbeys (1718), and John Ecton’s Liber Valorum (1711). These appear alongside interleaved sketches, as well as manuscript notes such as “Sir Thomas Blackston of Blackston, M.S.S. Book in the Heralds Office relating to this Country / 41. Sir Willm Dugdale vis Ao 1666”.

The printed texts are inserted incompletely, with the missing sections copied out by hand; and these manuscript notes help us to ascertain his working method. For example, he inserts Durham-related printed material, but where the text continues to another topographical area, he has crossed this out and added a signposting note (“Enter’d in Dorsetshire Libr 8vo” , “Enter’d in Yorkshire Libr 8vo” , “Enter’d in Cheshire Libr 8vo”, and so on) indicating that he has transposed those texts to other similar notebooks. Furthermore, where the texts move from print to manuscript, the handwritten continuation takes up the printed catchword, indicating that Irton is simply copying out the printed text from one of his other county notebooks. He marks these divisions explicitly, crossing out references to other locations and noting their inclusion in companion notebooks across multiple locations.

£1,000 Ref: 8360

This appealing compilation of manuscript and print in this volume serves primarily to assemble, but not to juxtapose, compare or even augment knowledge of the subject. Rather they reflect a reordering of pre-existing knowledge, but an arrangement which maintains the status quo – albeit in a compelling artefactual format.

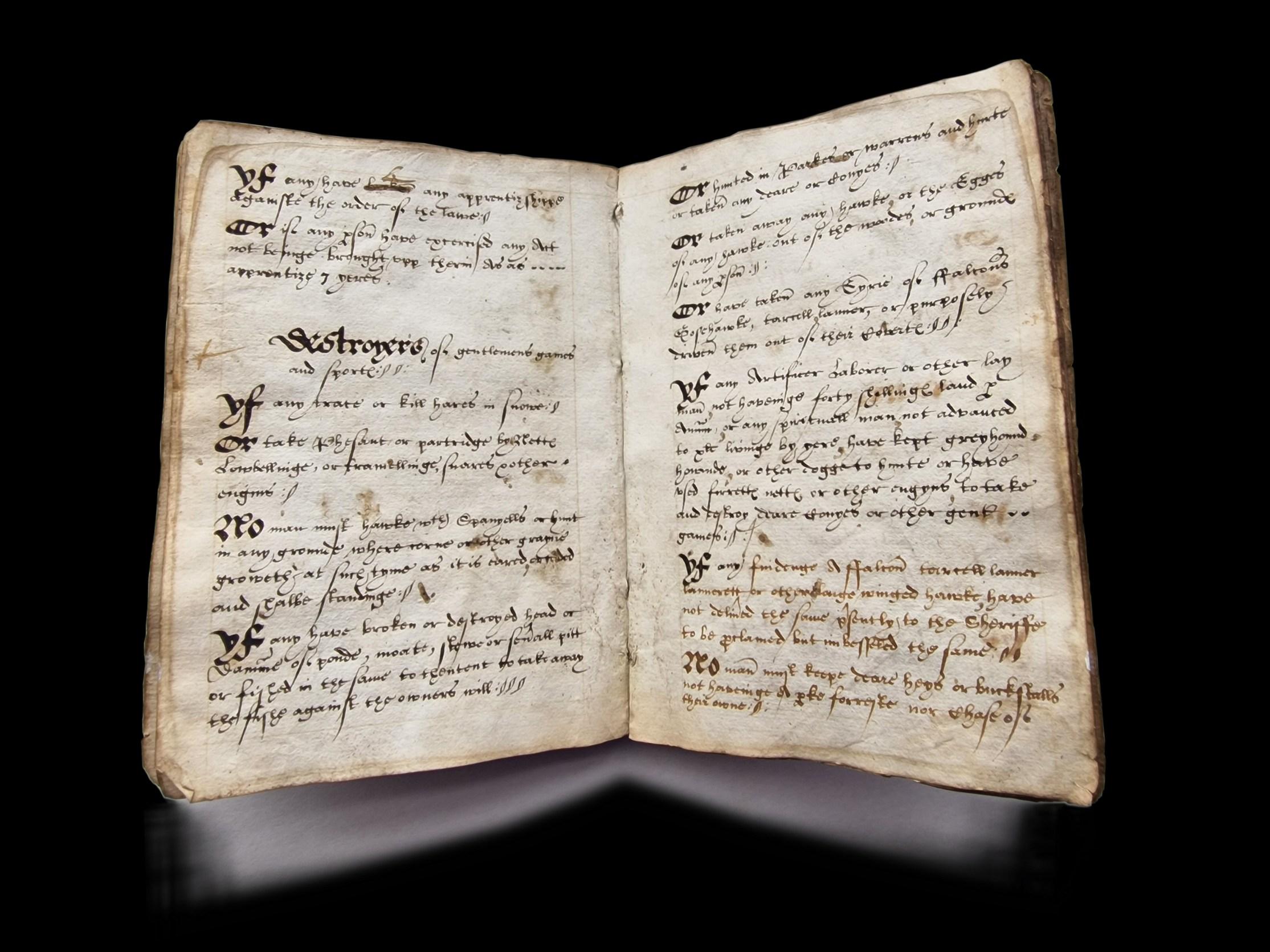

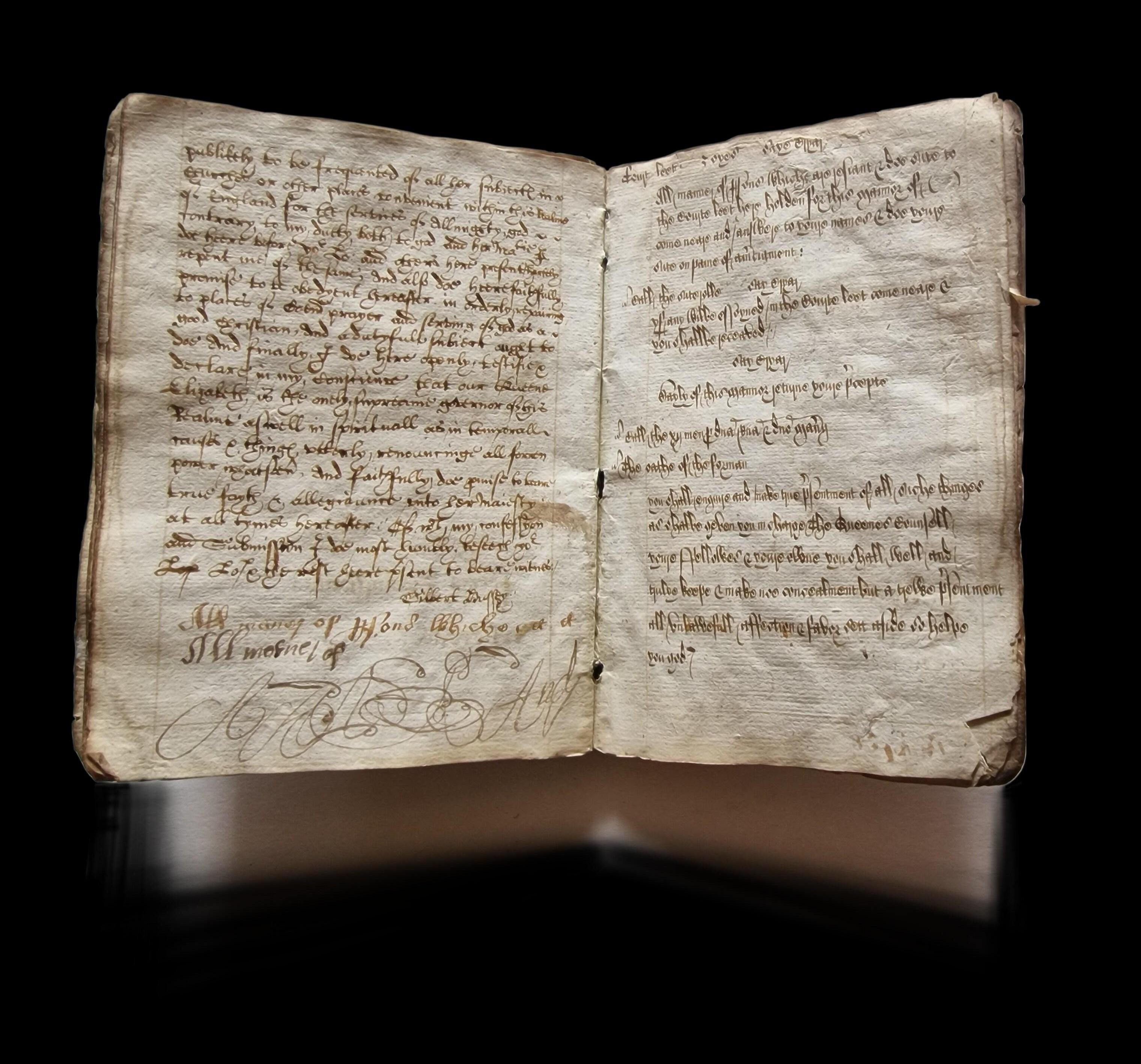

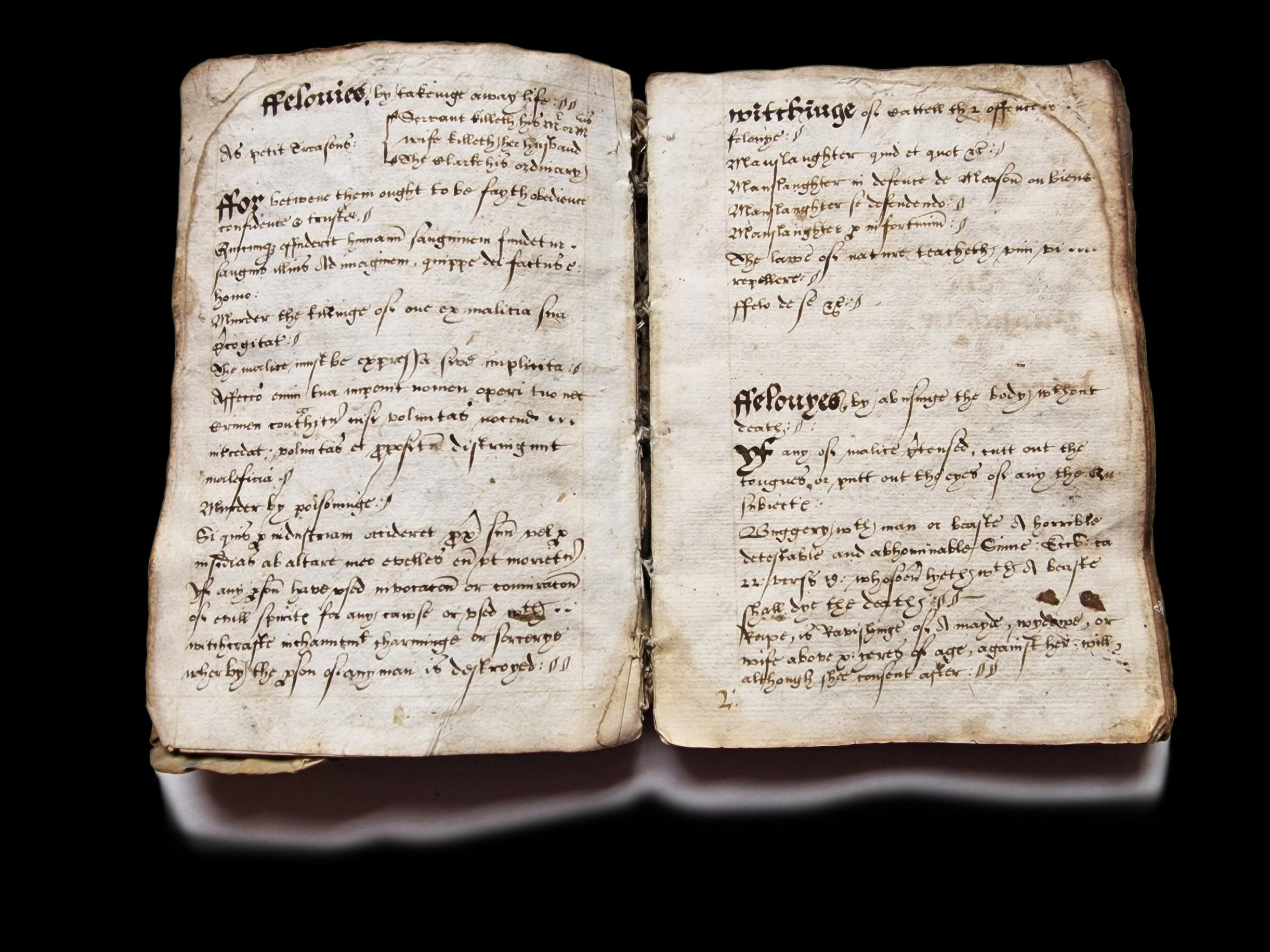

¶ [ELIZABETHAN SOCIETY].

English 16th-Century Manuscript Pocketbook.

[England. Circa 1590]. Octavo (148 x 100 x 10 mm). 113 text pages on 58 leaves. The text is divided into two main sections of 58 text pages and 55 text pages, separated by a single blank leaf. The first section covers the laws governing the people; the second section comprises protocols for assizes, court leet, and court baron. Contemporary limp vellum, damp staining to text.

Later inscriptions to front pastedown: “Abr[aham] Crosland His Booke 1673 Ex dono Clarissimi Amici Henery Mould Of Appleby”. Inscription to gutter margin: “Henery Mould did posses this booke”

7. POCKET MICROCOSM

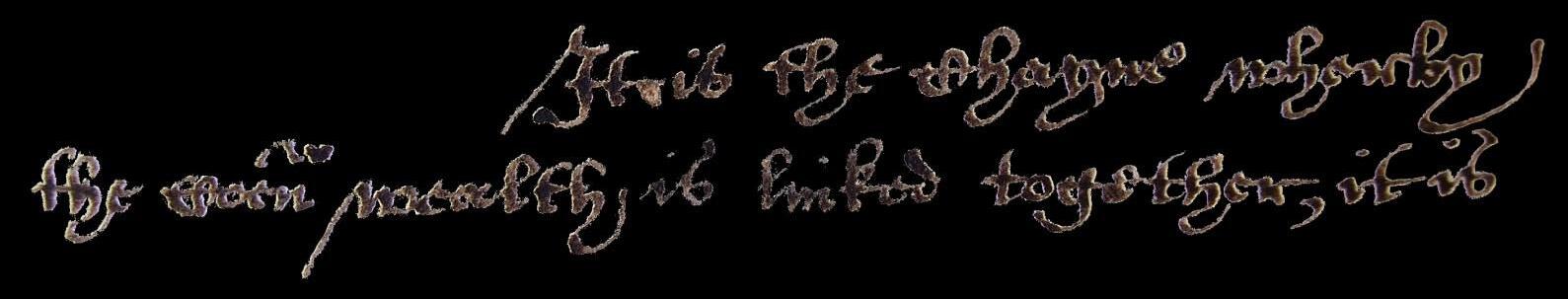

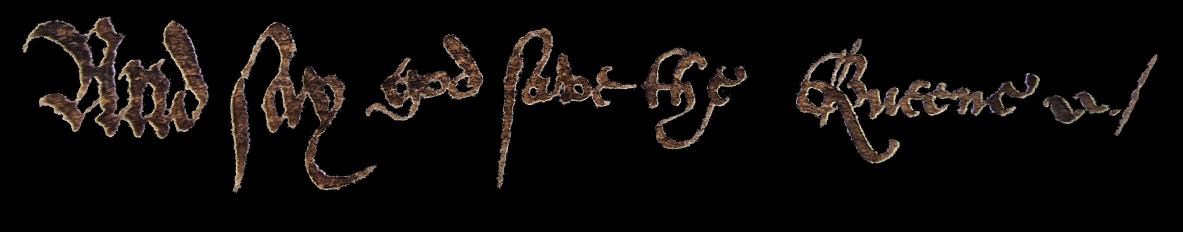

¶ The strictures and stratifications of Elizabethan society are packed into this little pocket book. Writing in highly expressive, sometimes richly metaphorical language, our scribe uses vivid imagery, especially in the parallel between the Queen’s relation to her people and the soul’s relation to the body, to underscore the crucial need for a robustly run state. The text moves from the political philosophy underpinning the social order, through to the mechanism by which that order was maintained, and the protocols and forms of words to be employed – and then to an illustration of this in practice, as a named individual is, in both senses, made an example of.

This progression from first principles to their practical application may indicate that our scribe intended to create a text – detailed but compact – that would guide not only their actions but their thoughts on the matters at issue.

DATING THE MANUSCRIPT