Information Catalog

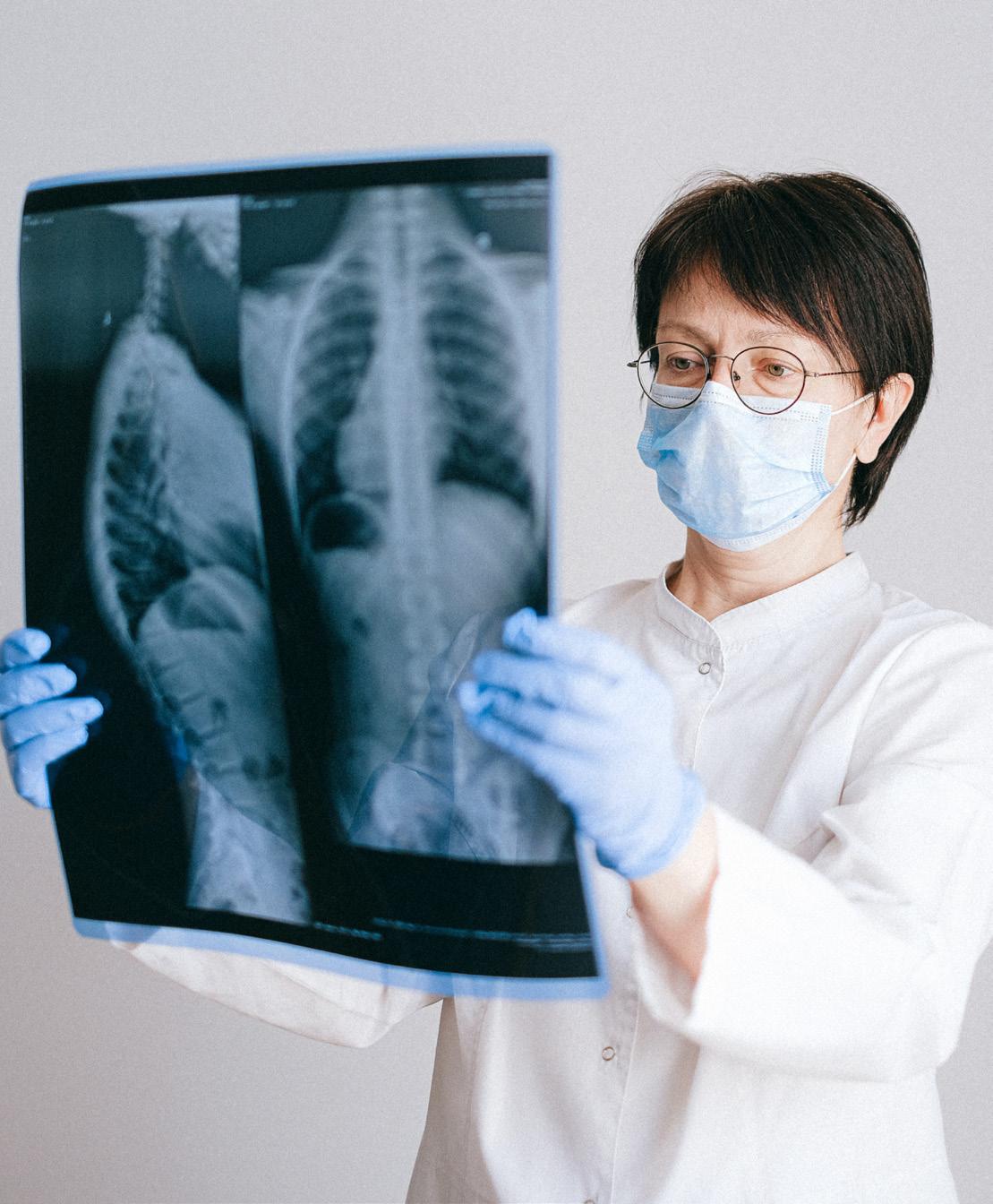

LungShield® helps to reduce the oxidative stress in the lungs caused by breathing in smoke, fuel emissions, chemicals, toxins and other free radicals that cause inflammation.

Oxidative stress is believed to play an essential role in the development of respiratory infections.

During exercise, your entire respiratory system works harder than usual and by managing oxidative stress during exercise LungShield can help to get the most out of your training sessions by boosting energy and reducing inflammation.

Similarly with asthma, COPD and other respiratory infections, LungShield helps to manage oxidative stress which causes inflammation and infections.

(Each capsule contains)

Alpha Lipoic Acid 100 mg

Ascorbic Acid 100 mg

Lycopene 500 µg

Zinc Gluconate 15 mg

Manganese 4 mg

Chromium 250 µg

Magnesium Citrate 240 mg

Copper 1 mg

Boron 2 mg

Molybdenum 250 µg

Vitamin B12 10 µg

Vitamin D3 500 iu

Take 1 capsule daily with at least 300ml water or as prescribed by your healthcare professional.

Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) also known as thioctic acid (TA) and 1,2 dithiolane -3-pentanoic acid, is an organic compound that is essential for the function of different enzymes. ALA or its reduced form, dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA) have many biochemical functions acting as potent antioxidants with anti-inflammatory properties, as metal chelators, reducing the oxidized forms of other antioxidant agents such as vitamin C and E and glutathione (GSH), and modulating the signalling transduction of several pathways, like insulin and nuclear factor kappa B (NFkB).

ALA has also shown to improve endothelial dysfunction and to reduce oxidative stress post exercise training; it also protects against the development of atherosclerosis and inhibits the progression of an already established atherosclerosis plaque. These above-mentioned actions have emphasized the use of ALA as a potential therapeutic agent for many chronic diseases such as Diabetes Mellitus (DM) and its complications, Hypertension, Alzheimer’s disease, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Asthma. Currently the use of ALA as a dietary supplement is growing in many aspects of medical and nutritional management of patients

ALA and its reduced form DHLA are considered powerful natural antioxidant agents with a scavenging capacity for many reactive oxygen species. ALA/DHLA can also regenerate other antioxidant substances such as vitamin C, vitamin E and the ratio of reduced/oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG). Glutathione is a sulfur tripeptide containing glutamate, cysteine and glycine. Their biosynthesis depends on substrate availability of cysteine, which is enhanced by ALA/DHLA which converts cystine into cysteine.

Considering the latter action, ALA/DHLA is an activator/inducer of translocation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) to the nucleus for regulation of antioxidant gene expression. GSH which has also a connection with circadian rhythms has many functions over different intracellular processes like ageing, oxidative balance and detoxification of many pollutants

In conclusion ALA is a potent antioxidant through multiple processes which can be used along with conventional drugs in the treatment of COPD, Asthma and other lower respiratory tract infections caused by chronic inflammation or oxidative stress.

Lycopene is a naturally occurring pigment in a large family of plant pigments known as carotenoids. Carotenoid is the pigment found in tomatoes, pink grapefruit, watermelon, papaya, guava etc. and produces colours ranging from yellow, orange and red. Carotenoids also contribute to some plant food aromas. Some carotenoids also possess provitamin A activity and have shown potent antioxidant activity. There are two primary types of carotenoids: hydrocarbon carotenoids and xanthophylls.

Hydrocarbon carotenoids, such as lycopene, are composed entirely of hydrogen and carbon. In contrast, xanthophylls, such as lutein, contain oxygen in addition to carbon and hydrogen. Some hydrocarbon carotenoids, such as β-carotene and -carotene, can be enzymatically cleaved to form vitamin A. Lycopene lacks provitamin A activity because of the absence of a terminal beta ionone ring.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are oxygen-containing molecules that either are or have the potential to generate free radicals. Overproduction of ROS results in a condition known as oxidative stress, which has been linked to cancer, cardiovascular disease and chronic inflammation. Carotenoids, including lycopene, can be potent antioxidant molecules and are especially effective at scavenging the ROS singlet oxygen. Of the carotenoids, lycopene is the most effective singlet oxygen scavenger in vitro.

In conclusion Lycopene as ALA is a potent antioxidant which can be used with conventional drugs in the treatment of COPD, Asthma and any other respiratory tract infection caused by chronic inflammation and oxidative stress.

Zinc is an essential nutrient that is required in numerous processes in the body, including; DNA synthesis, immune function, wound healing, cell signalling, apoptosis, and cell invasion. Studies have shown that zinc has anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. Some clinical trials have shown that Zinc can reduce the duration of cold symptoms. Other studies have shown that Zinc decrease airway inflammation and hyper responsiveness to other allergens, this suggest that Zinc could assist patients who suffer from asthma caused by allergens as well as athletes suffering from hyper responsiveness during exercise.

Zinc delays oxidative processes on a long-term basis by inducing the expression of metallothioneins. These metal-binding cysteine-rich proteins are responsible for maintaining zinc-related cell homeostasis and act as potent electrophilic scavengers and cytoprotective agents. Furthermore, zinc increases the activation of antioxidant proteins and enzymes, such as glutathione and catalase. On the other hand, zinc exerts its antioxidant effect via two acute mechanisms, one of which is the stabilization of protein sulfhydryl against oxidation. The second mechanism consists in antagonizing transition metal-catalysed reactions. Zinc can exchange redox active metals, such as copper and iron, in certain binding sites and attenuate cellular sitespecific oxidative injury.

Zinc is essential for normal development and function of the immune system because zinc is a cofactor for many proteins involved in immune regulation. Abnormal zinc homeostasis in immune cells also increases the risk of infection. A substantial body of work has been performed in adaptive immunity, where zinc deficiency

affects the thymus, resulting in decreased T-cell maturation/activation and altered Th1/ Th2 response. Zinc deficiency also negatively affects humeral immunity by impairing B-cell development and differentiation in response to immune stimuli.

The zinc transporter ZIP10 plays a critical role in B-cell antigen receptor signal transduction and early B-cell development. More recently, the role of zinc in inflammatory cells has also been established. Intracellular zinc concentrations are vital in the maturation of dendritic cells, a subpopulation of immune cells involved in the inflammatory response. ZIP6 has been shown to play a role in this activation of dendritic cells.

In humans, zinc supplementation has been associated with decreased inflammatory responses in populations susceptible to zinc deficiency, including sickle cell patients and the elderly

Manganese (Mn) is an essential element in the human body that is mainly obtained from food and water. Manganese is absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract and then transported to organs enriched in the mitochondria (in particular the liver, pancreas, and pituitary) where it is rapidly concentrated. Manganese is involved in the synthesis and activation of many enzymes (e.g., oxidoreductases, transferases, hydrolases, lyases, isomerases, and ligases); metabolism of glucose and lipids; acceleration in the synthesis of protein, vitamin C, and vitamin B; catalysis of haematopoiesis; regulation of the endocrine; and improvement in immune function. Moreover,

Manganese metalloenzymes including arginase, glutamine synthetase, phosphoenolpyruvate decarboxylase, and Manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) also contribute to the metabolism processes listed above and reduce oxidative stress against free radicals.

Importantly, Manganese is a required component of Manganese Superoxide Dismutase (MnSOD) for reducing mitochondrial oxidative stress. Mitochondria are the major place where physiological and pathological cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced. When excessive ROS accumulate abnormally, it would contribute to the oxidative damage found in several neuropathological conditions related to enhanced glucocorticoid expression, which plays an important role in regulating the biosynthesis and metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins. Additionally, MnSOD is the primary antioxidant that scavenges superoxide formed within the mitochondria and protects against oxidative stress. If mitochondria are impaired or dysfunctional, ROS production will be further increased and will exacerbate the oxidative stress in mitochondria.

Manganese can be beneficial in reducing the severity of oxidative stress in patients suffering from LRTI and Asthma, as well as in athletes during strenuous exercise.

Chromium is a trace mineral that enhances insulin receptor sensitivity in peripheral cells. Insulin resistance can lead to a number of comorbidities including hypertension, cholesterol and diabetes. Chromium supplementation can reduce the risk of acquiring these comorbidities and so promote healthy living. Absorption of chromium from the intestinal tract is low, ranging from less than 0.4% to 2.5% of the amount consumed and the remainder is excreted in the faeces. Nicotinic acid and ascorbic acid are required for Chromium absorption and act in synergy with this element. Ascorbic acid has been reported to enhance chromium transport and absorption. Absorbed chromium is stored in the liver, spleen, soft tissue, and bone.

The body’s chromium content may be reduced under several conditions. Diets high in simple sugars (comprising more than 35% of calories) can increase chromium excretion in the urine. Infection, acute exercise, pregnancy and lactation, and stressful states (such as physical trauma) increase chromium losses and can lead to deficiency, especially if chromium intakes are already low.

Type 2 diabetes and glucose intolerance, In type 2 diabetes, the pancreas is usually producing enough insulin but the body cannot use the insulin effectively. The inability of insulin to exert its effect on tissues is called insulin resistance. Insulin resistance is the primary cause of type 2 diabetes. Chromium increases receptor

sensitivity in peripheral cells which can decrease insulin resistance.

Lipid metabolism, Chromium can decrease total and low-densitylipoprotein (LDL) and triglyceride levels and increased concentrations of Apolipoprotein A (a component of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol known as HDL). This suggest that chromium can decrease cholesterol levels in the body In addition to its role in glucose and lipid metabolism, chromium also functions as an antioxidant. Recent studies have shown that chromium protects the body from oxidative stress associated with exposure to CCl4. Also chromium protects against lipid peroxidation and decreases the effects of free radicals in people with type 2 diabetes.

Magnesium is a mineral required for several functions in the human body. It acts as a cofactor for more than 300 enzymes, regulating a number of fundamental functions such as: muscle contraction, protein synthesis, nerve function, blood glucose control, hormone receptor binding, cardiac excitability, transmembrane ion flux and blood pressure control. Moreover, magnesium also plays a vital role in energy production: crucial for ATP metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis. Magnesium also plays a role in DNA, RNA and glutathione synthesis.

Magnesium homeostasis is regulated by the intestines, the bones, and the kidneys. The majority of magnesium is absorbed by a passive paracellular mechanism in the ileum and distal parts of the jejunum, while a smaller amount is actively transported in the large intestine. Around 24–76% of ingested magnesium is absorbed in the gut and the remaining is eliminated in the faeces. The

proportion of absorbed magnesium from the gut depends on the amount of ingested magnesium and the status of magnesium in the body. Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and oestrogen are hormones that play an important role in magnesium homeostasis. Smoking cigarettes reduces plasma Mg concentration and also increases the levels of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) which can lead to oxidative stress.

Several studies have indicated that dietary magnesium were associated with an improvement in lung function, as measured by forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume (FEV). While the mechanism of action is not entirely understood, it is possible that magnesium acts via anti-inflammatory effect and reduces lung inflammation along with the role of magnesium in regulating broncho-constrictors such as acetylcholine (Ach) and histamine.

Magnesium is also a bronchodilator; it relaxes the bronchial muscles and expands the airways allowing more air to flow in and out of the lungs. This can relieve symptoms of asthma such as shortness of breath.

In conclusion magnesium can reduce oxidative stress through glutathione production and also improve lung function by reducing inflammation and regulation broncho-constrictors such as histamine and Acetylcholine.

Copper (Cu) is an essential trace element. Needed only in trace amounts, the human body contains approximately 100 mg Cu. As a transition metal, it is a cofactor of many enzymes, Ceruloplasmin being the most abundant Cu-dependent enzyme. Ceruloplasmin is involved in the formation of

the iron carrier protein transferrin. Beyond its role in iron metabolism, the need for Cu also derives from its involvement in a myriad of biological processes, including antioxidant defence, neuropeptide synthesis and immune function (neutrophil production). Copper also help maintain the normal rates of red-and-white blood cell formation.

Though an essential micronutrient, Cu is toxic at high levels. An overload of this metal easily leads to Fenton-type redox reactions, resulting in oxidative cell damage and cell death. However, Cu toxicity as a result of dietary excess is generally not considered a widespread health concern, because of the homeostatic mechanisms controlling Cu absorption and excretion

Boron is a trace mineral that plays a role in mineral metabolism and membrane function. Boron’s beneficial effects on bone metabolism are due in part to the roles it plays in increasing the Half-life and bioavailability of Vitamin D. Boron also increases 17β-estradiol levels through the inhibition of the degradation of 17β-estradiol. Boron also significantly improves magnesium absorption and deposition in bone, where it is a cofactor for key enzymes that regulate calcium metabolism.

Numerous studies have indicated that boron decreases concentrations of inflammatory markers called cytokines; specifically hs-CRP and TNF-. Boron through this process possess anti-inflammatory properties which can be beneficial in the treatment of COPD and Asthma due to chronic inflammation .

is necessary for the de novo synthesis of purine nucleotides (and therefore DNA and RNA). Methionine itself is part of the chemical process involved in the creation of S-adenosylmethionine, a substance critical to myelin formation and the methylation of

Another co-enzyme form of vitamin B-12, 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin, serves as a cofactor for methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, the enzyme that leads to the synthesis of succinyl Co-A, an intermediate of citric acid and a precursor of porphyrin (and therefore, heme) synthesis. Succinyl-CoA is also critical to the catabolism of some fatty acids and the production of

Vitamin B12 deficiency symptoms include: fatigue, vision loss, mental problems like depression and nerve problems like numbness or tingling. Vitamin B12 deficiency is more common in the elderly with 1 in 10 people aged over 75 affected. Vitamin B12 deficiency can also lead to Anemia as Vitamin B12 is essentials in Red Blood Cell production. Anemia can lead to Tachycardia (irregular heartbeat), shortness of breath, weakness, fatigue and chest pain. The body does not produce Vitamin B12 this is why it is necessary to get this nutrient through your diet or as

Vitamin D3 is an essential nutrient stimulates intestinal calcium absorption. Without vitamin D, only 10–15% of dietary calcium and about 60% of phosphorus are absorbed. Vitamin D sufficiency enhances calcium and phosphorus absorption by 30–40% and 80%, respectively. Vitamin D deficiency affects almost 50% of the population worldwide. An estimated 1 billion people worldwide, across all ethnicities and age groups, have a vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D deficiency normally presents with bone pain and muscle weakness. However, for many people, the symptoms are subtle. Yet, even

It is well known that most vitamins cannot be synthesized in the body, hence supplementation is essential

without symptoms, too little vitamin D can pose health risks. Low blood levels of the vitamin have been associated with the following: Increased risk for cardiovascular disease, Cognitive impairment, severe asthma in children, Cancer Vitamin D Receptors is present all over the body including in antigen-presenting cells, with known direct effects on innate and adaptive immunity. Vitamin D decreases cell proliferation and increases cell differentiation, stops the growth of new blood vessels, and has significant antiinflammatory effects. New studies carried out by The University of Western Australia have found that Vitamin D deficiency correlates to poor respiratory functioning. Researchers’ measured serum Vitamin D levels, lung function and respiratory symptoms in more than 5000 patients and found that low levels of Vitamin D were associated with respiratory illness such as asthma and bronchitis. Other studies have found that the severity of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) symptoms can be reduced with Vitamin D supplementation.

Vitamin C is a micronutrient essential for a host of physiological processes in the body. This includes: development and maintenance of connective tissue, bone formation, wound healing and maintenance of healthy gums. Vitamin C helps in the synthesis and metabolism of tyrosine, tryptophan and folic acid, the conversion of cholesterol to bile acids (lower blood cholesterol), the hydroxylation of glycine, proline, lysine and catecholamine and acts as an antioxidant that protects the body against free radicals.

Bioavailability or the effective concentration of vitamin C essentially depends on its effective absorption from intestine and renal excretion. Reduced bioavailability of vitamin C is often seen in stress, alcohol intake, smoking, fever, viral

illnesses, usage of antibiotics and pain killers, exposure to petroleum products or carbon monoxide and heavy metals toxicity.

The clinical hallmark of severe and prolonged vitamin C deficiency is scurvy, which is fatal if left untreated. Other symptoms of Vitamin C deficiencies include: impaired wound healing, gingivitis, perifollicular haemorrhages, ecchymosis, and petechiae. This is largely related to impaired collagen biosynthesis and HIF-1 hydroxylation. Other symptoms of severe vitamin C deficiency are malaise and fatigue or lethargy, which may be difficult to diagnose clinically. These symptoms can be explained by impaired carnitine biosynthesis resulting in decreased fatty acid transport and subsequent β-oxidation in mitochondria required for ATP production and decreased synthesis of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine. The enzymatic synthesis of both carnitine and norepinephrine involves hydroxylation steps that depend on vitamin C for full enzyme activity.

Studies have shown that Vitamin C stimulate the immune system by enhancing T-cell proliferation in response to an infection. Vitamin C also supports various cellular functions in both the innate and adaptive immune system. Vitamin C deficiency results in impaired immunity and higher susceptibility to infection. In turn infections significantly impact Vitamin C levels due to increased inflammation and metabolic requirements. This shows that Vitamin C supplementation can both prevent and treat respiratory tract infections. Another clinical use of vitamin C is to increase nonhemeiron absorption in the small intestine. Vitamin C reduces dietary iron and allows for efficient transport across the intestinal epithelium. Food sources of vitamin C or supplements, when consumed with iron, may lead to increased haemoglobin production in anaemic patients.

Adcock, M & Rahman, I (2006). Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. European Respiratory Journal, 28, 219-242. DOI: 10.1183/09031936.06.00053805

Kirkham, P & Rahman, I (2005). Oxidative stress in asthma and COPD: Antioxidants as a therapeutic strategy. Respiratory Diseases, Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research. DOI: 10.1016/j. pharmthera.2005.10.015

Donaldson, K, Macnee, W, Morrison, D & Rahman I (1996). Systemic oxidative stress in asthma, COPD, and smokers. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Volume 154 Issue 4. DOI: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.4.8887607

Kouretas, D & Mylonas, C (1999). Lipid peroxidation and tissue damage. Department of Pharmacology, University of Leeds, U.K.

Gomes, M.B & Negrato, C.A (2014). Alpha-lipoic acid as a pleiotropic compound with potential therapeutic use in diabetes and other chronic diseases. Department of Internal Medicine, Diabetes Unit, State University Hospital of Rio de Janeiro. DOI: 10.1186/1758-5996-6-80

Harris, G.K, Kopec, R.E, Schwartz, S.J & Story, E.N (2010). n Update on the Health Effects of Tomato Lycopene. Department of Food, Bioprocessing, and Nutrition Sciences at North Carolina State University. DOI: 10.1146/ annurev.food.102308.124120

Brown, K.H, Peerson, J.M & Wuehler, S.E (2001). The importance of zinc in human nutrition and estimation of the global prevalence of zinc deficiency. International Nutrition and Department of Nutrition, University of California. DOI: 10.1177/156482650102200201

Brown, K.H, Drake, V.J, Ho, E, Huang, L, Peerson, M & Wuehler S.E (2015). Zinc. Advances in Nutrition, Volume 6, Issue 2, March 2015, Pages 224–226. DOI:10.3945/an.114.006874

Li, L & Yang, X (2018). The Essential Element Manganese, Oxidative Stress, and Metabolic Diseases: Links and Interactions. Department of Occupational Health and Environmental Health, School of Public Health, Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi, China. DOI: 10.1155/2018/7580707

Aschner, M & Erikson, K (2017). Manganese. Advances in Nutrition, Volume 8, Issue 3, Pages 520–521. DOI:10.3945/an.117.015305

Anderson, R.A (1997). Chromium as an Essential Nutrient for Humans. Beltsville Human Nutrition Center, U.S. Department of Agriculture. DOI: 10.1006/rtph.1997.1136

Abdollahzad, H, Aghdashi, M.A, Azar,M.R.M.H, Eghtesadi, S, Izadi, A, Mehaki, B, Moradi, S, Moradi, S, Pasdar, Y & Talab, A.T (2020). Effects of Chromium Picolinate Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Biomarkers in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: a Randomized Clinical Trial. DOI: 10.7762/cnr.2020.9.2.97

Chaturvedi, U.C, Seth, P.K, Shrivastava, R & Uperti, R.K (2002). Effects of chromium on the immune system. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology, Volume 34, Issue 1, September 2002, Pages 1–7.

Al Alawi, A.M, Falhammar, H & Majoni, S.W (2017). Magnesium and Human Health: Perspectives and Research Directions. International Journal of Endocrinology. DOI: 10.1155/2018/9041694

Genuis, S.J & Schwalfenberg, G.K (2017). The Importance of Magnesium in Clinical Healthcare. DOI: 10.1155/2017/4179326 Delimaris, I, Iakovidis, I & Piperakis S.M (2011). Copper and Its Complexes in Medicine: A Biochemical Approach. Biology Unit, Department of Pre-School Education, University of Thessaly. DOI: 10.4061/2011/594529

Chow, K, Chow-Johnson, H.S & Gaetke, L.M (2014) Copper: Toxicological relevance and mechanisms. Archives of Toxicology volume 88, pages1929–1938. DOI: 10.1007/s00204-014-1355

Pizzorno, L (2015). Nothing Boring About Boron. Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal.

Chang, S & Lee, H (2019). Vitamin D and health - The missing vitamin in humans. Division of Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, MacKay Children’s Hospital. DOI: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2019.04.007

Chambial, S, Dwivedi, S, John, P.J, Sharma, P & Shukla, K.K (2013). Vitamin C in Disease Prevention and Cure: An Overview. DOI: 10.1007/s12291-013-0375-3

Frei, B, Lykkesfeldt, J & Michels, A.J (2014). Vitamin C. Advances in Nutrition, Volume 5, Issue 1, January 2014, Pages 16–18. DOI: 10.1007/s12291-0130375-3

Heiner-Fokkema, M.R, van der Klauw, M.M, Wolffenbuttel, B.H.R & Wouters, H.J.C.M (2019). The Many Faces of Cobalamin (Vitamin B12) Deficiency. Department of Endocrinology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen. DOI: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.03.002

O’Leary, F & Samman, S (2010). Vitamin B12 in Health and Disease. Discipline of Nutrition and Metabolism, School of Molecular Bioscience, University of Sydney. DOI: 10.3390/nu2030299

DB Pharmaceuticals is a registered, Grade A certified pharmacy under the South African Pharmacy Council (SAPC) – with registration number Y60310.

We are fully compliant with the current South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) and the Medicines and Related Substances Control Amendment Act, No. 19 of 1976 requirements for Category D – Complementary Medicines.

Council as a pharmacy owner, grading certificate Grade A, and recording of a pharmacy.

Certification of the manufacturing plant also includes a Department of Health Manufacturing Pharmacy certificate and a Certificate of Acceptability for Food Premises and is registered with the South African National Department of Health.

DB Pharmaceuticals welcomes SAHPRA’s approach to regulate the manufacture and sale of Complementary Medicines and Health Supplements which we believe will result in a safer, more efficient experience for patients who seek quality natural health products.

All our products old and new have been developed by our two in-house responsible pharmacists who have 37 years of experience between them.

Once products and formulations have been researched and developed the formulation is sent to our team of specialist formulary pharmacists at the manufacturing site who review and test formulations against recent research to ensure safety, quality, and efficacy.

The manufacturing facility is licensed with the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) which is only granted after a positive GMP inspection by the regulator.

The manufacturing plant is further accredited by the South African Pharmacy

36 Sovereign Drive, Route 21 Corporate Park, Irene, Centurion Gauteng, South Africa 0062 info@lungshield.co.za www.lungshield.co.za Helpline: 012 111 8313