FREDERICK DOUGLASS MEMORIAL HALL DECODING

Howard University Office of Real Estate Development and Capital Asset Management

Howard University Office of Real Estate Development and Capital Asset Management

Above: The Latin motto Veritas et Utilitas, meaning “Truth and Service,” encircles the Howard University seal.

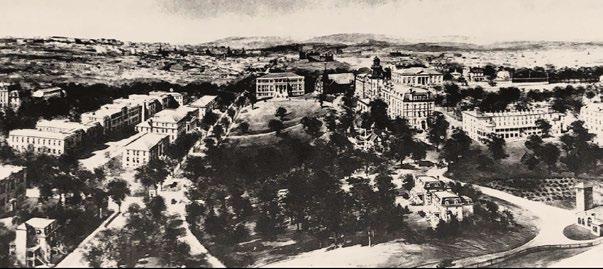

Opposite: Howard University campus and reservoir with Douglass Hall site outlined in white, circa 2025

Veritas et Utilitas—Truth and Service. At Howard University, the search for truth inspires discovery. Service connects the university to the world. Together, they shape an education grounded in action and accountability.

Founded in 1867, Howard University is a private research institution with 14 schools and colleges offering more than 130 areas of study. Guided by a mission to prepare leaders across disciplines, Howard has awarded more than 120,000 degrees in the arts, sciences, and humanities and is nationally recognized for nurturing generations of Black professionals in medicine, engineering, law, architecture, and education. Howard’s historic central campus in Northwest Washington offers an urban setting where education, research, and community engagement converge to prepare leaders who advance social justice and global impact.

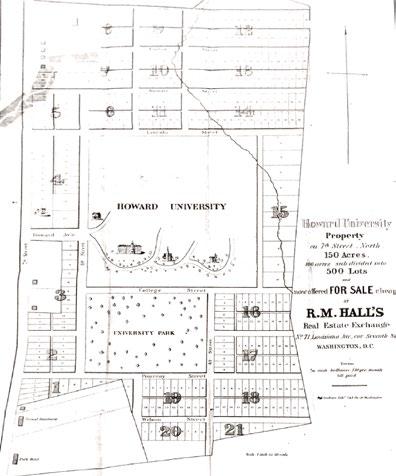

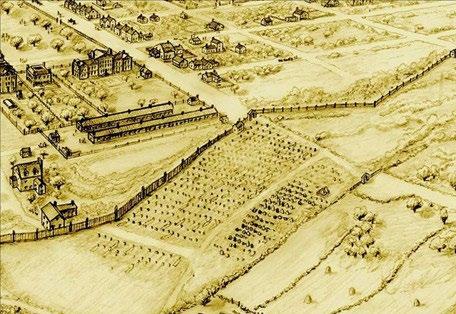

That mission shapes Howard’s academic programs, guides its public leadership, and is vividly expressed in the campus’s design and evolution. Published in 1996, The Long Walk: The Placemaking Legacy of Howard University traces this history. Authored by Harry G. Robinson III and Hazel Ruth Edwards, the book offers a meticulously researched

study documenting the campus’s progression from the original 150 acres acquired from John Smith in 1867 through the significant changes of the 20th century. This study illuminates how Howard’s architecture and landscape express a distinctive cultural identity and an enduring commitment to civic purpose.

Inspired by Robinson and Edwards’s work, Decoding Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall expands the narrative, diving deep into the life of a single building through its design, social context, and evolving role on campus. To decode architecture is to interpret how buildings express ideas and values. It means looking closely at form, symbolism, and material, and considering the cultural and political conditions in which a building was conceived and used. Decoding also traces the drift of meaning over time.

Decoding Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall is the first in a series developed by the Office of Real Estate Development and Capital Asset Management that explores the places that define Howard’s campus. This book offers insight into how architecture and social purpose align, and how design rooted in intention continues in Truth and Service.

Copyright © 2025 Howard University

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except as permitted by US copyright law. For permission requests, contact Howard University.

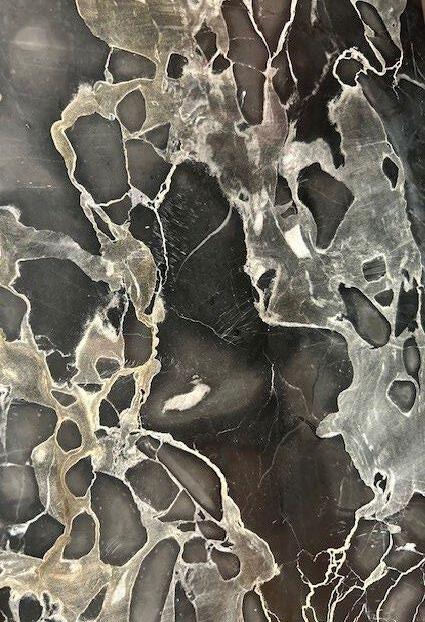

This detail is from the fireplace surround within the historic Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall reading room. The black marble with white and gold veining is assumed to be Nero Portoro, typically quarried in Porto Venere, Italy, also known as the Gulf of Poets.

Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall embodies resilience at the heart of one of America’s most influential historically Black universities. This landmark stands as a living symbol of struggle and renewal during an era when questions of equity remain urgent.

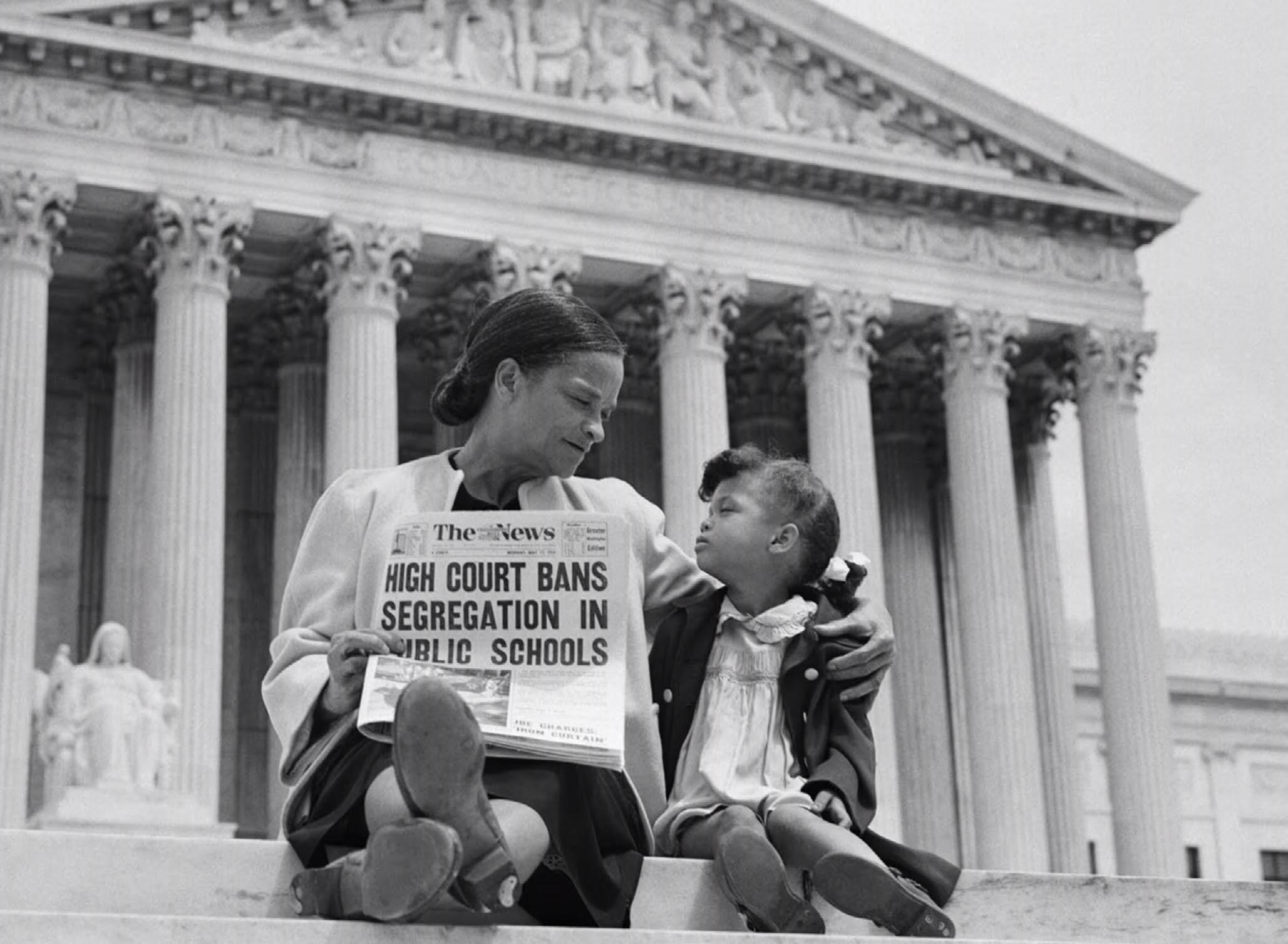

As our nation continues to confront the legacies of segregation, disinvestment, and systemic inequality, recounting the story of Douglass Hall is essential. Ninety years after the opening ceremony welcomed students through its doors, the building’s origins illuminate deep connections between architecture and justice. The structure’s endurance through challenging times reveals our collective responsibility to advance the ideals championed by one of history’s greatest human rights advocates. This book documents the layered story of a place carrying the weight of our shared future, serving as a record and a call to action.

The story begins with a vision: a building imagined as a memorial to its namesake and a plan for a resilient future. Frederick Douglass, abolitionist, orator, writer, and Howard University trustee, stands at its center. From

there, the story moves through the minds and hands of those who brought the building to life: David Williston, the first professionally trained Black landscape architect in the United States, and Albert I. Cassell, Howard’s pioneering architect and campus planner, who translated vision into form.

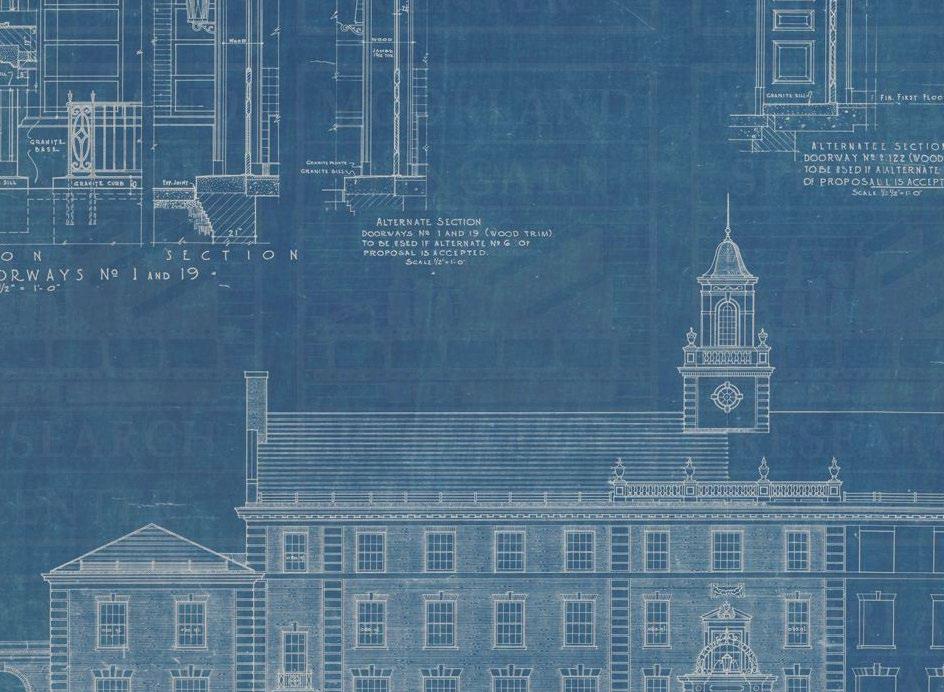

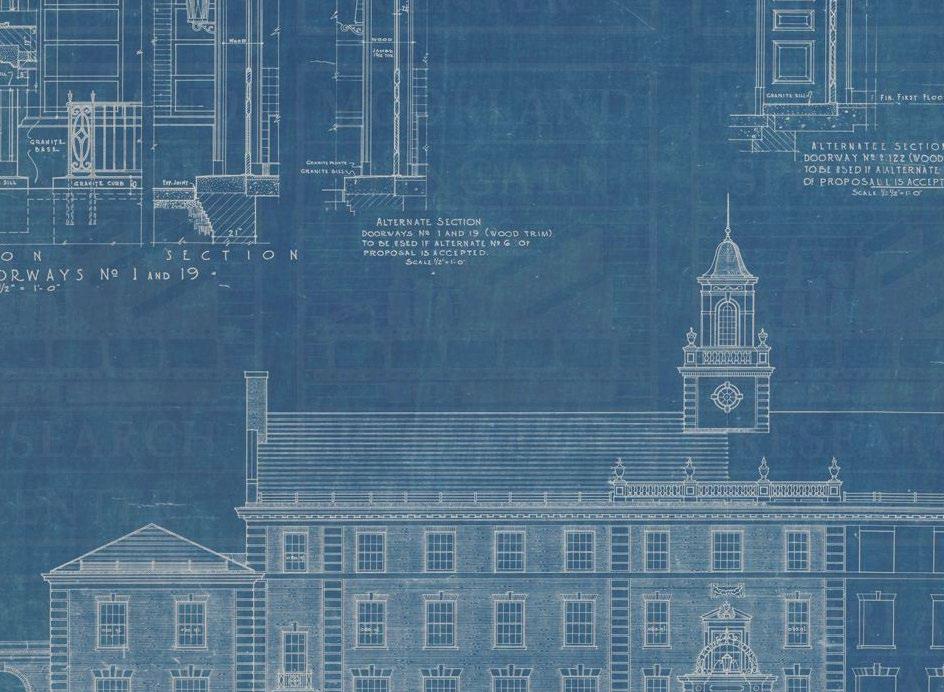

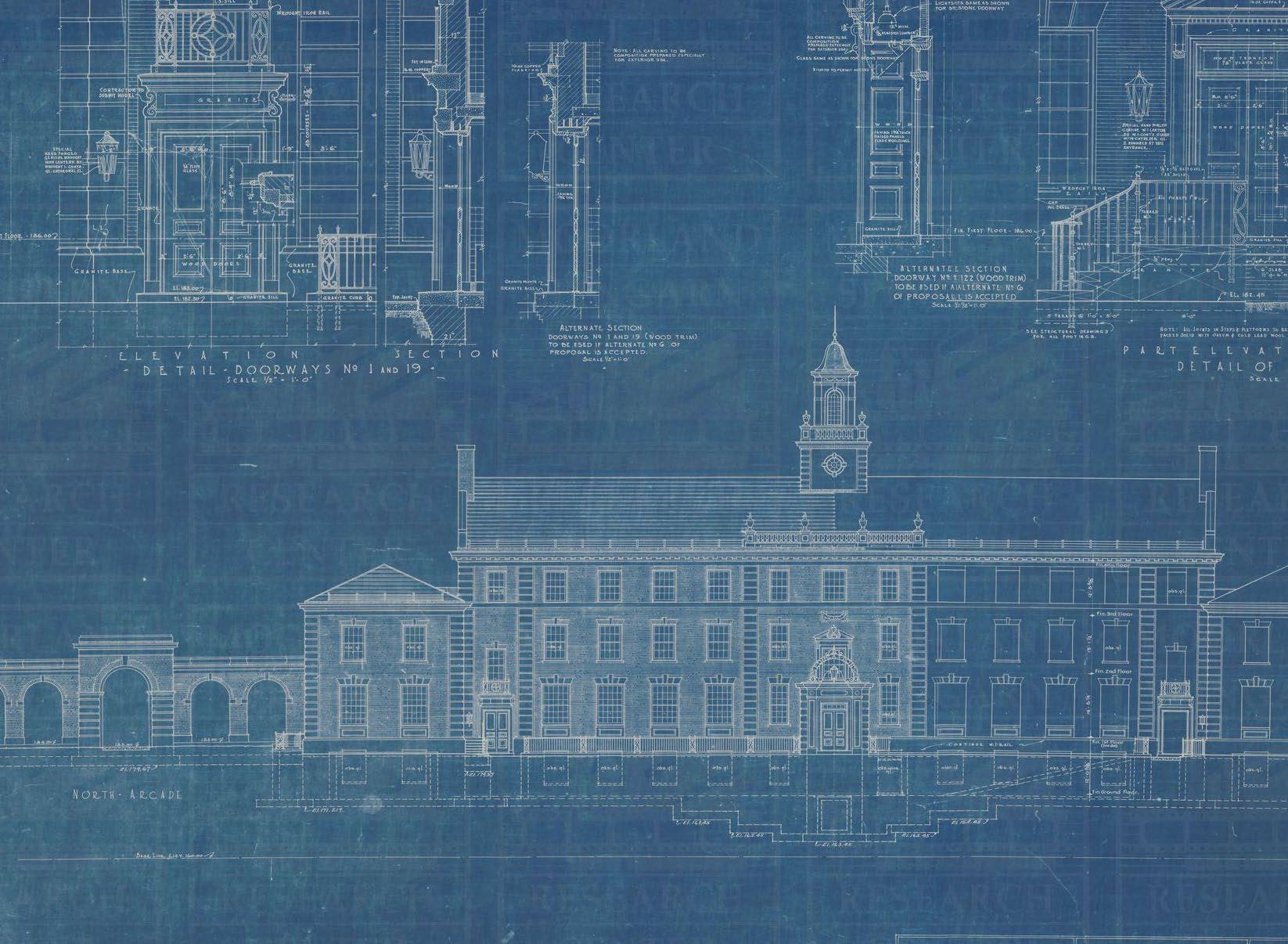

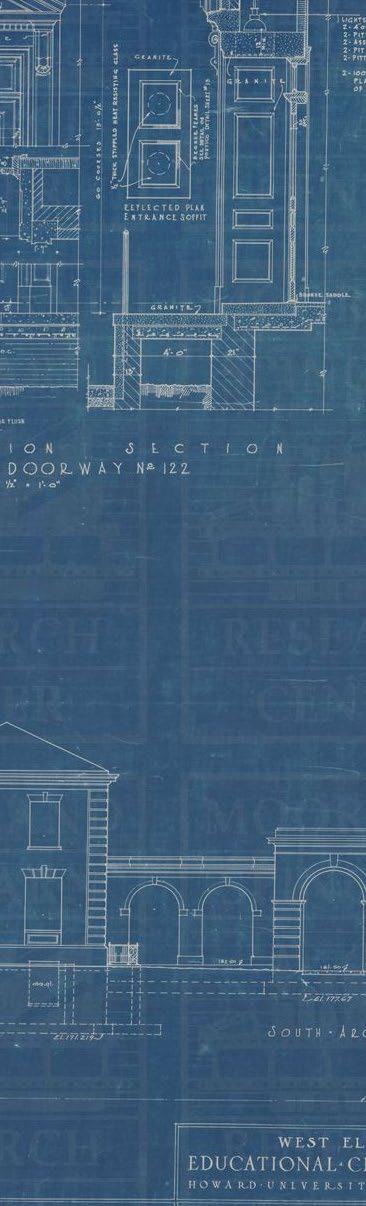

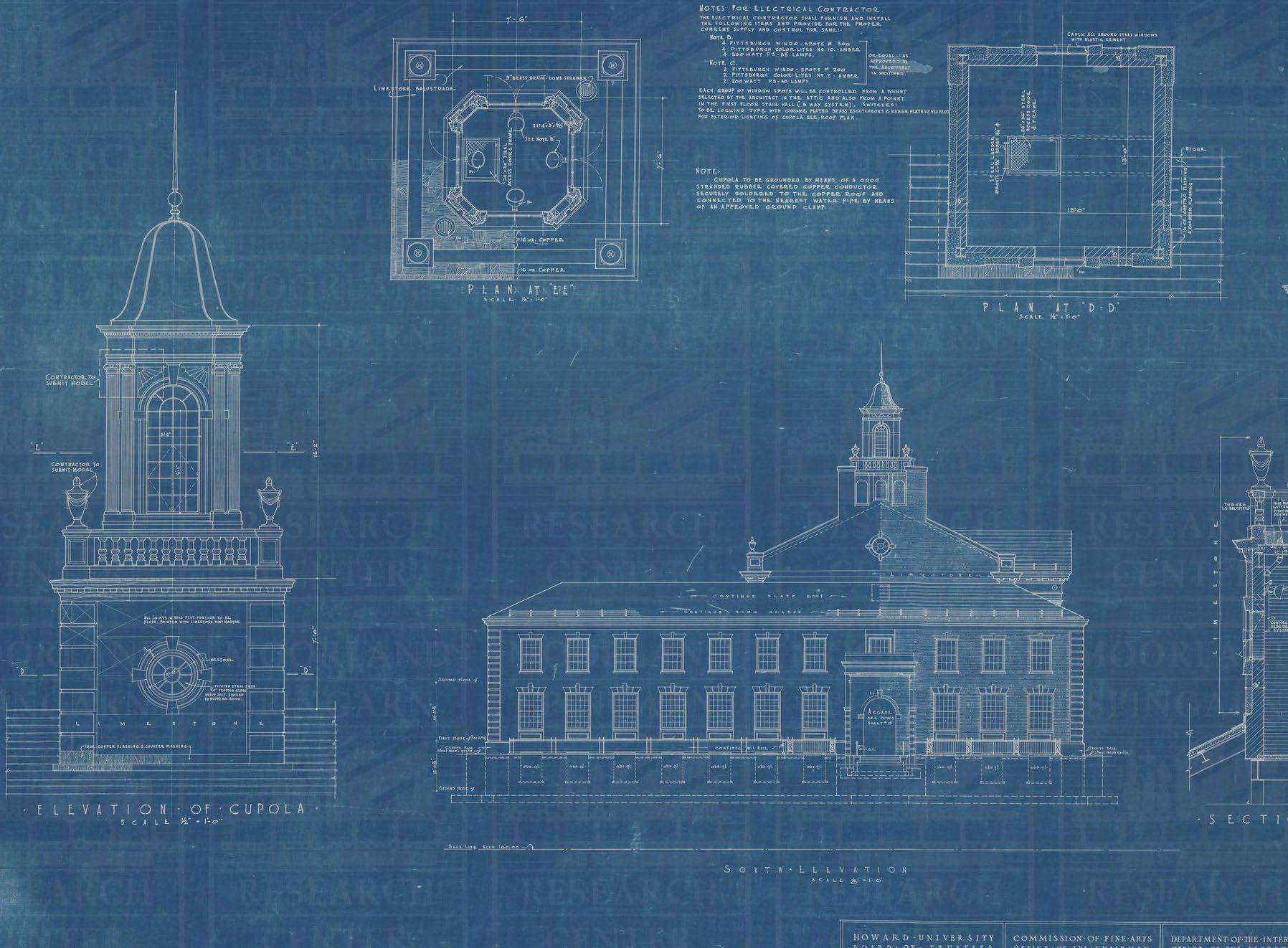

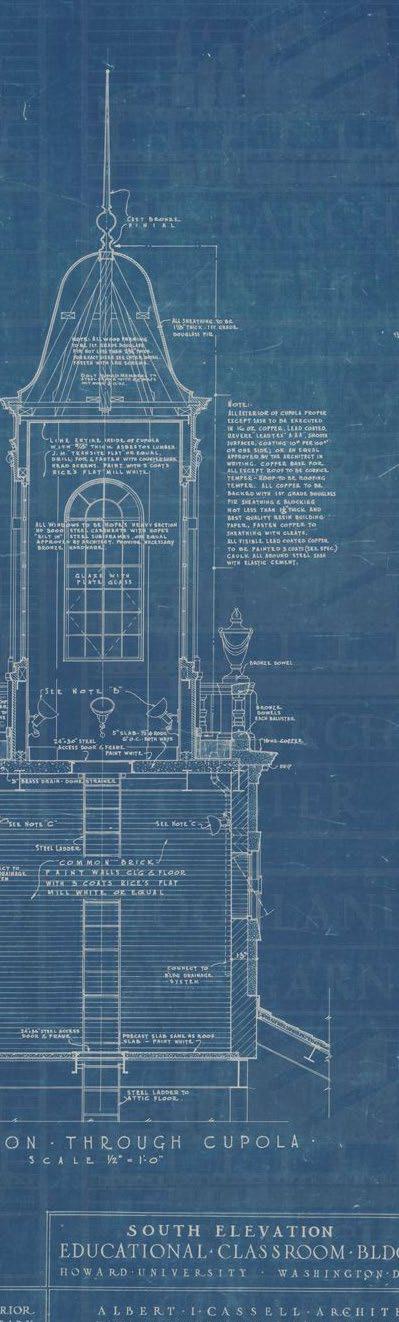

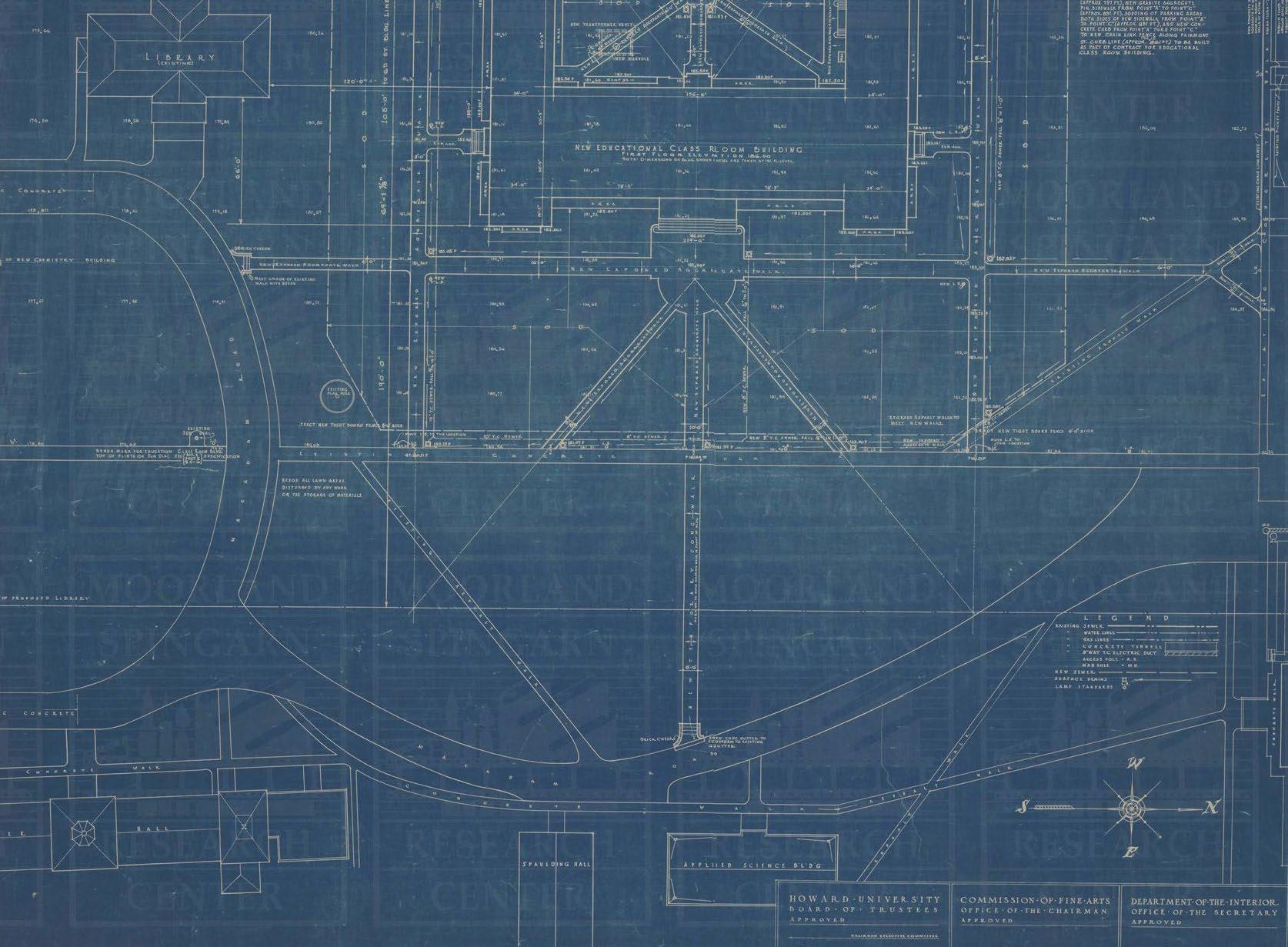

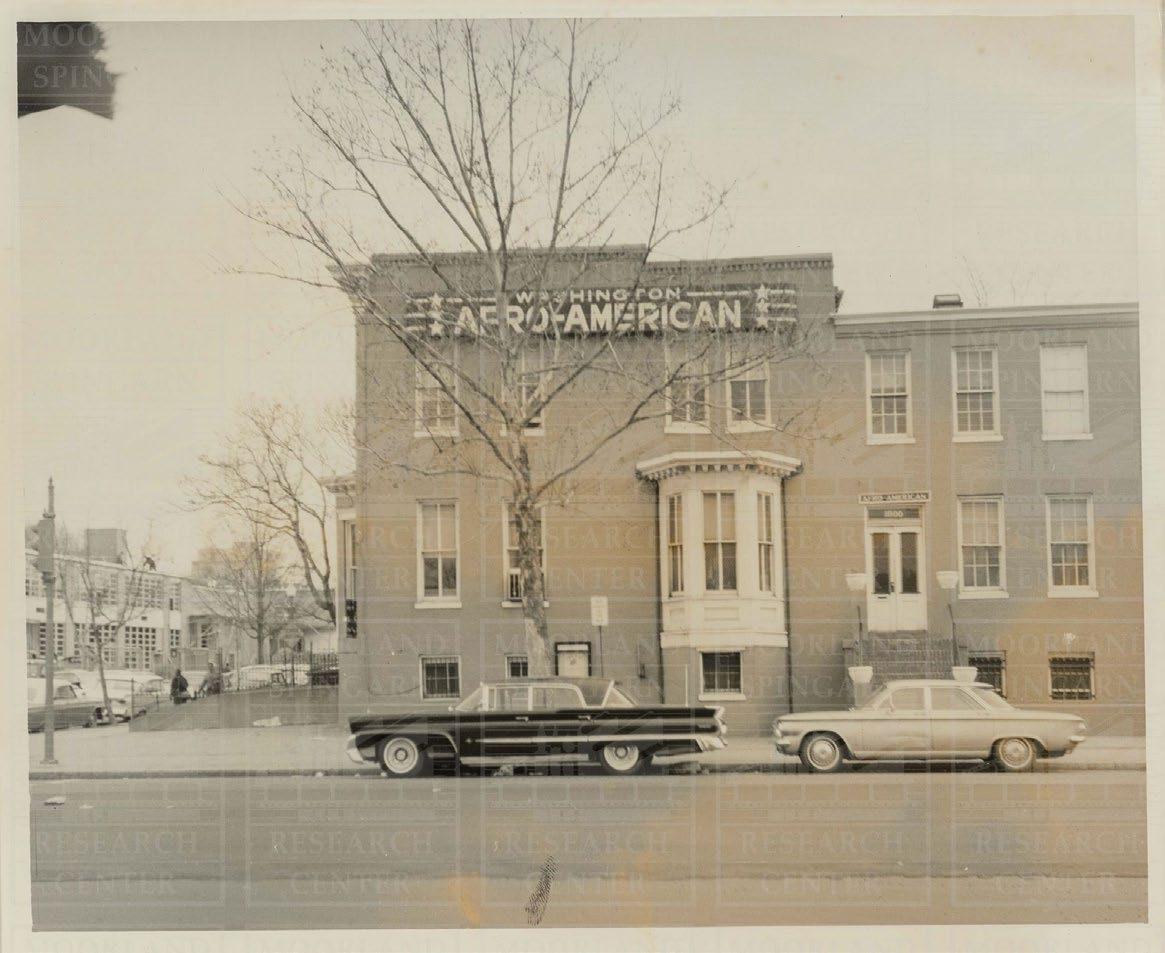

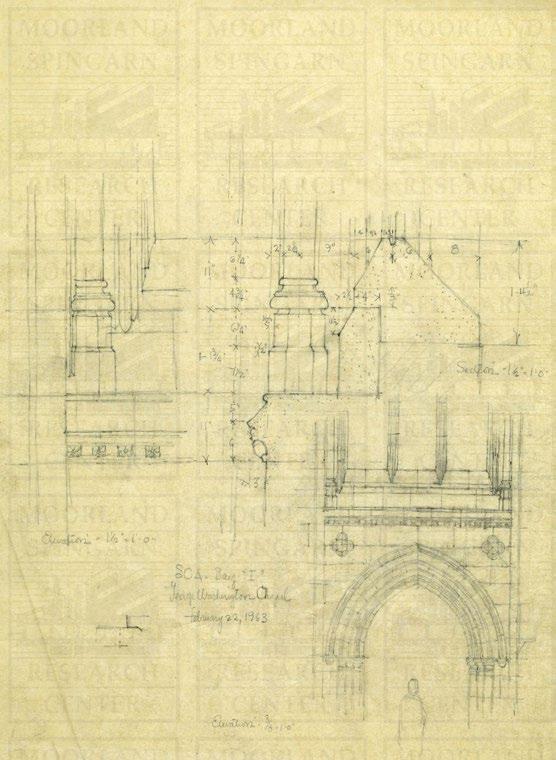

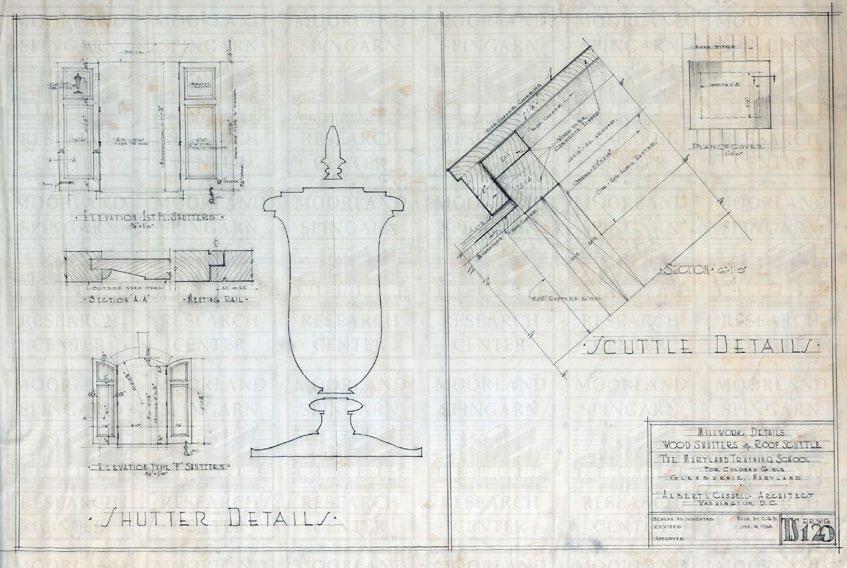

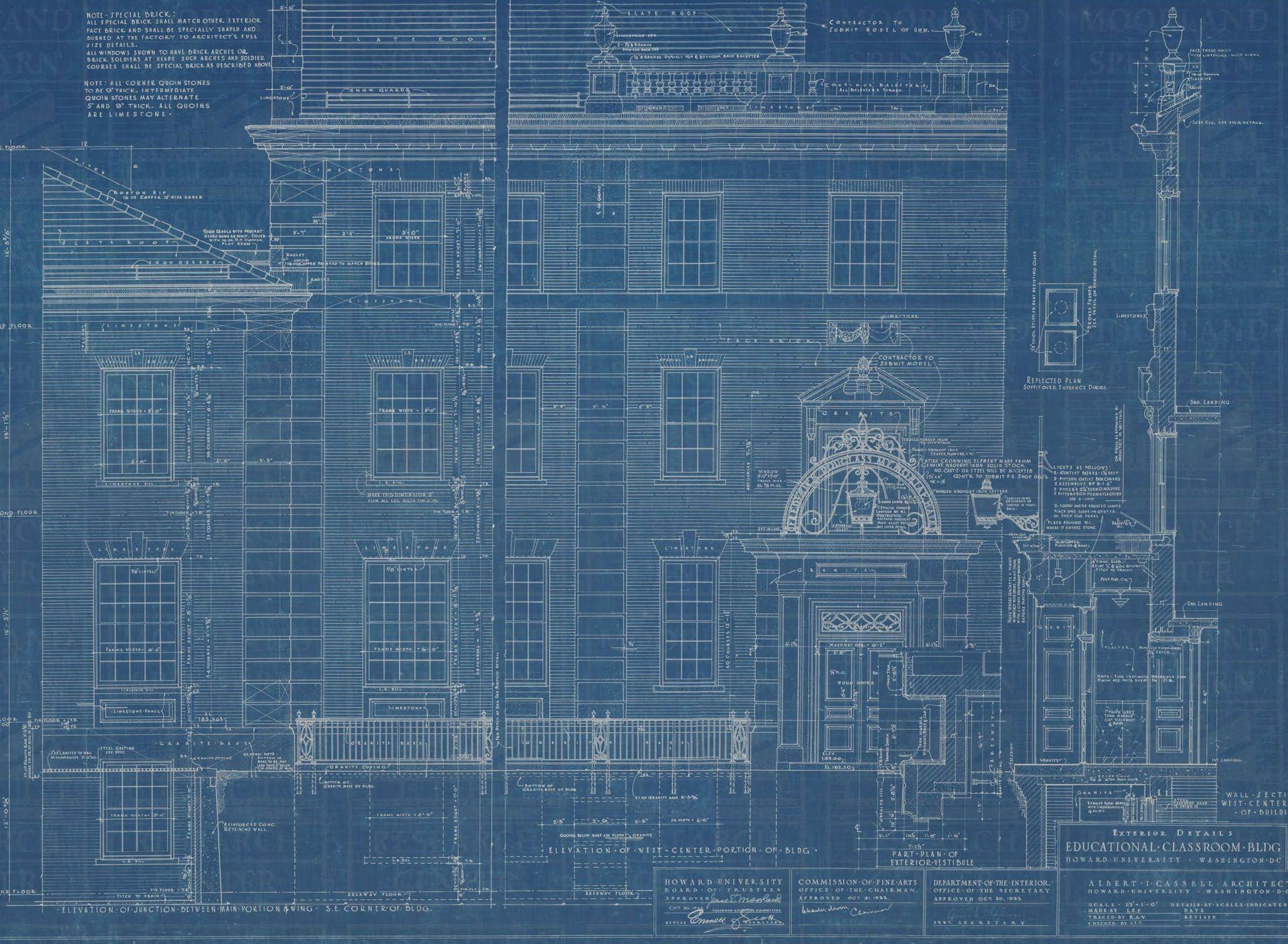

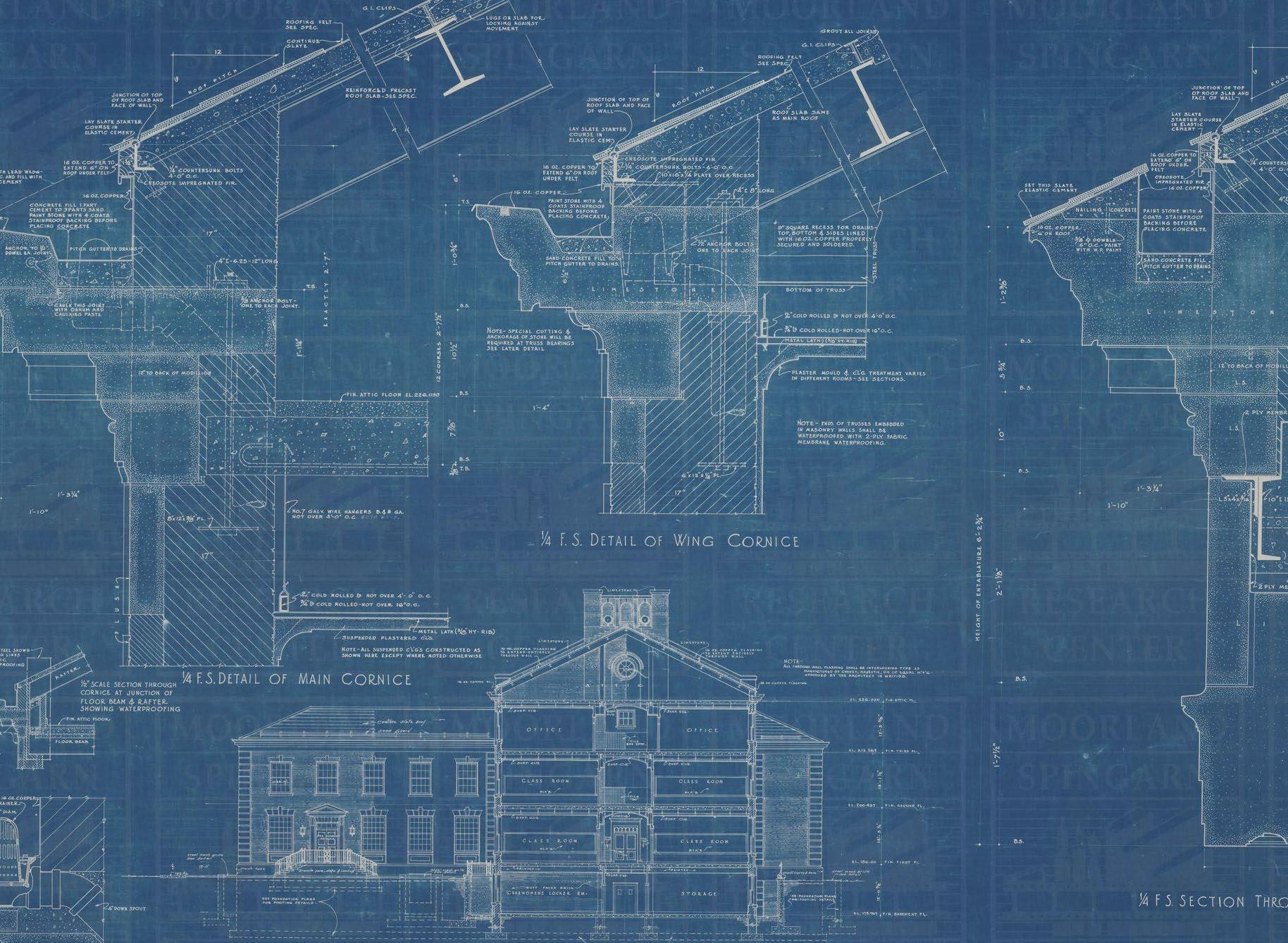

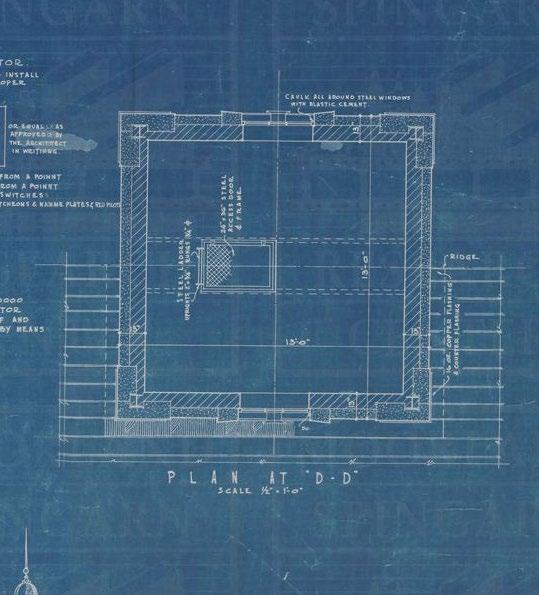

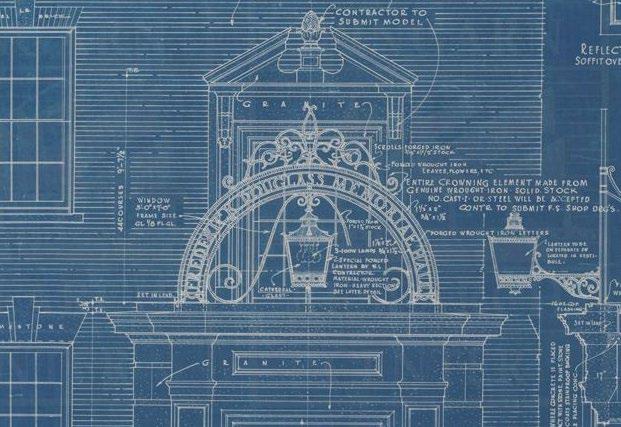

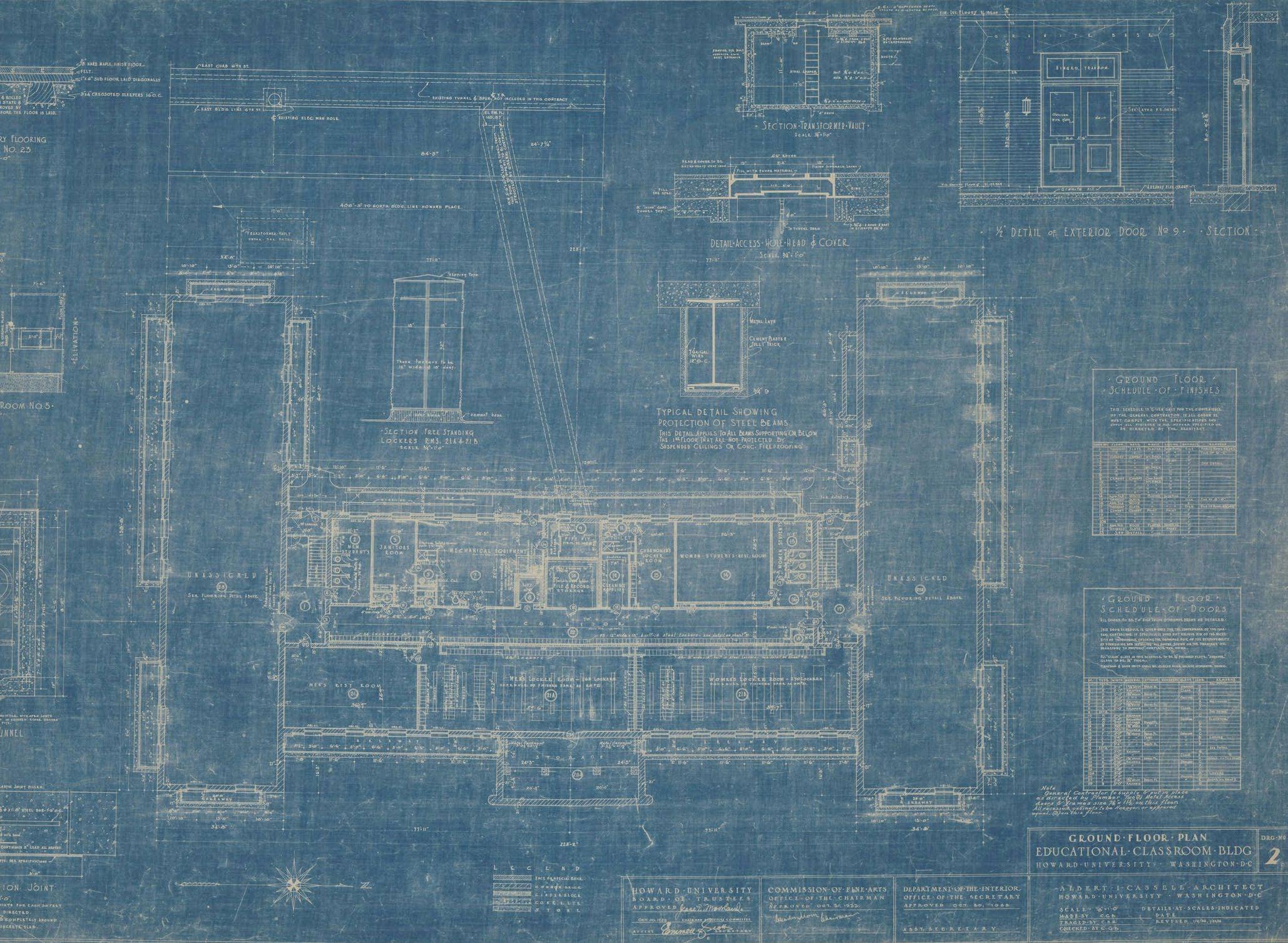

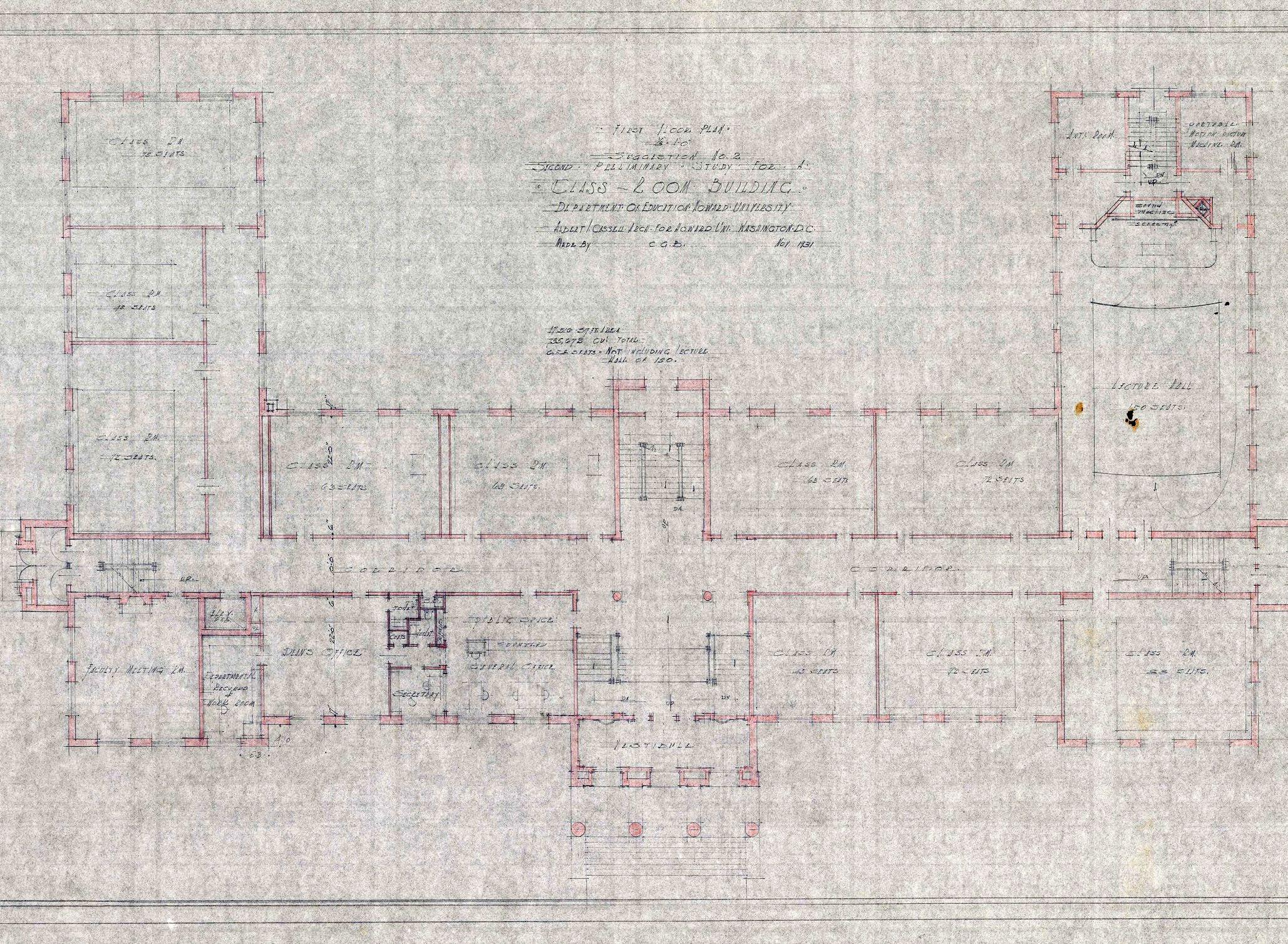

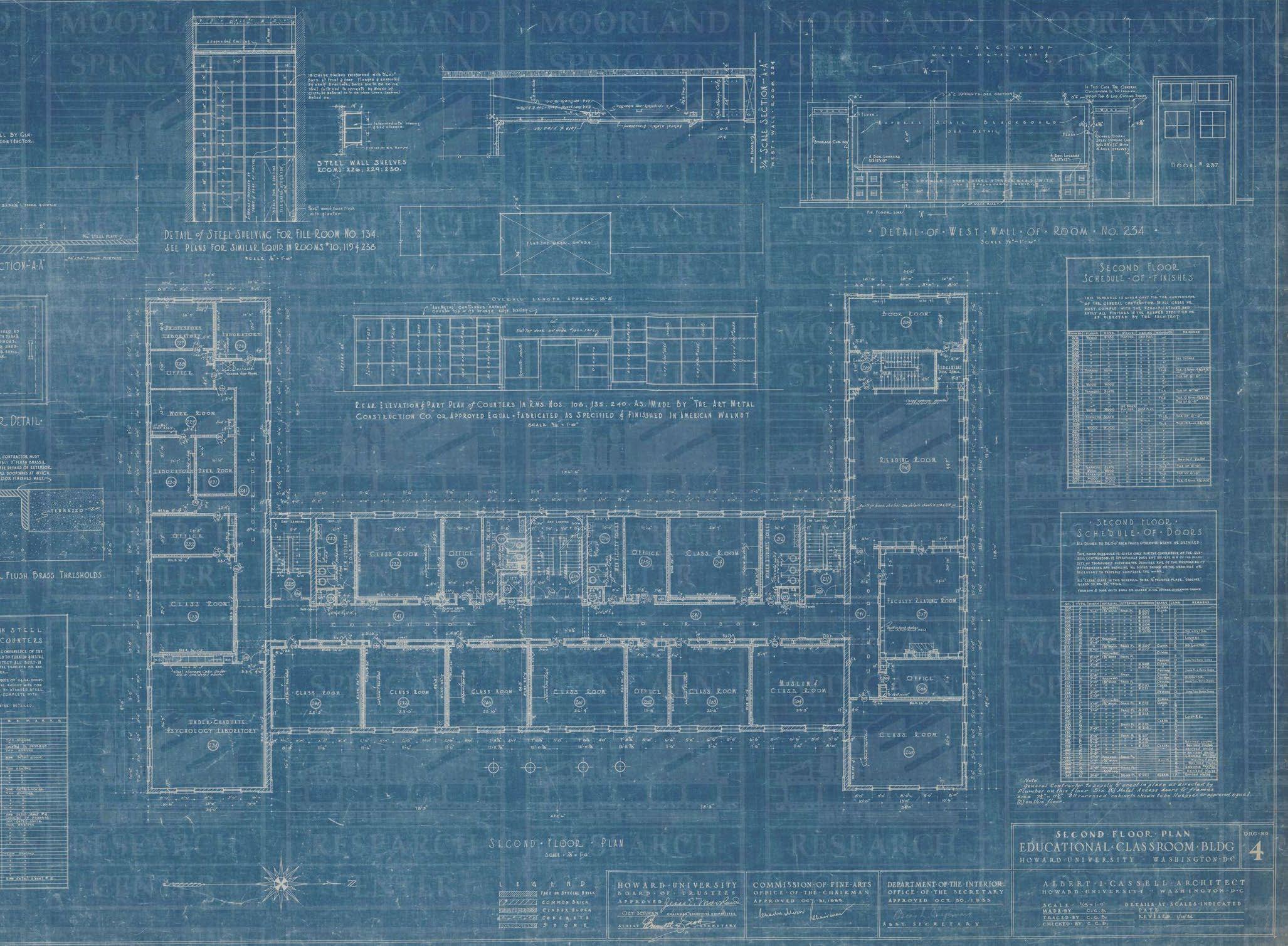

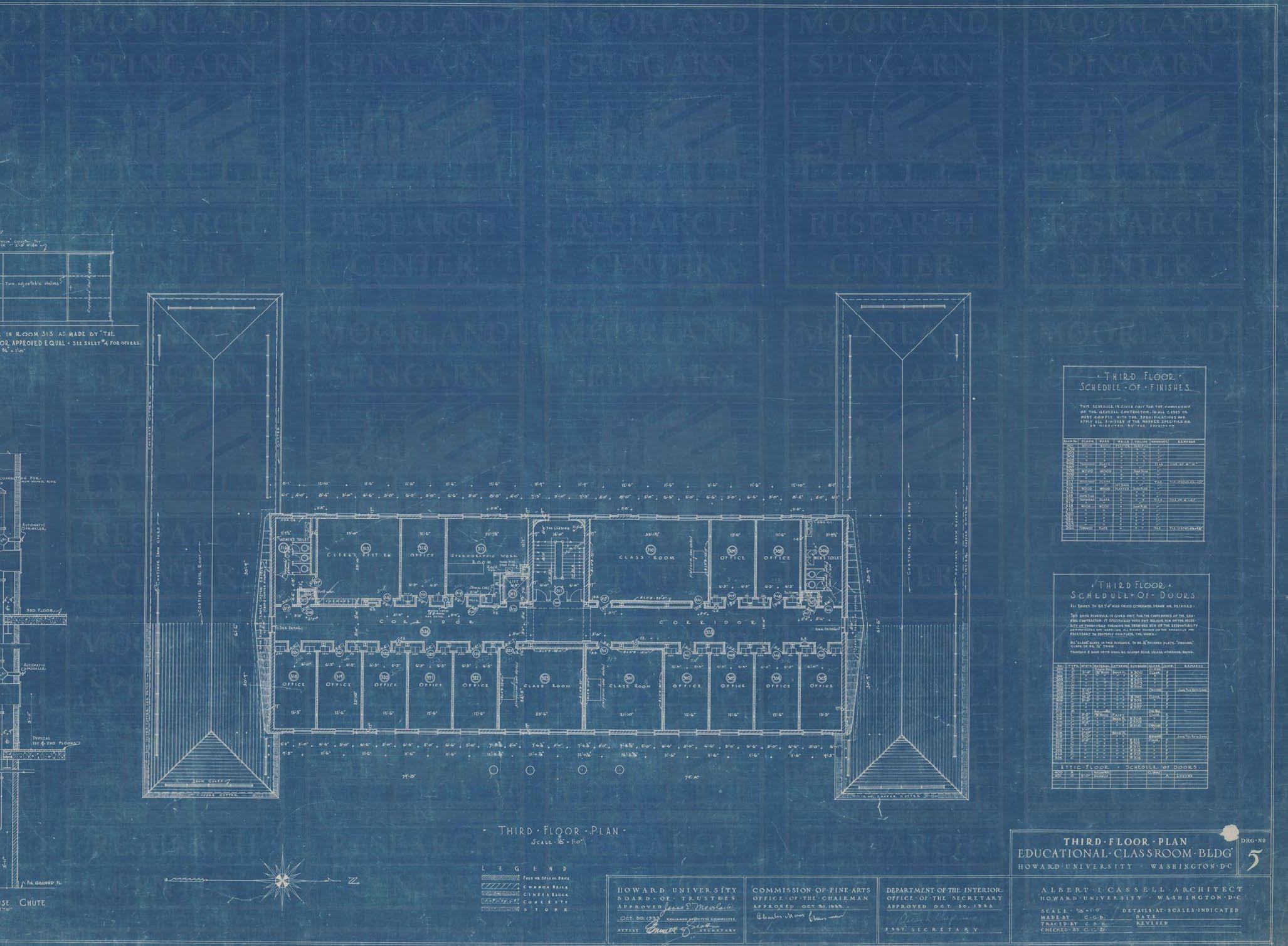

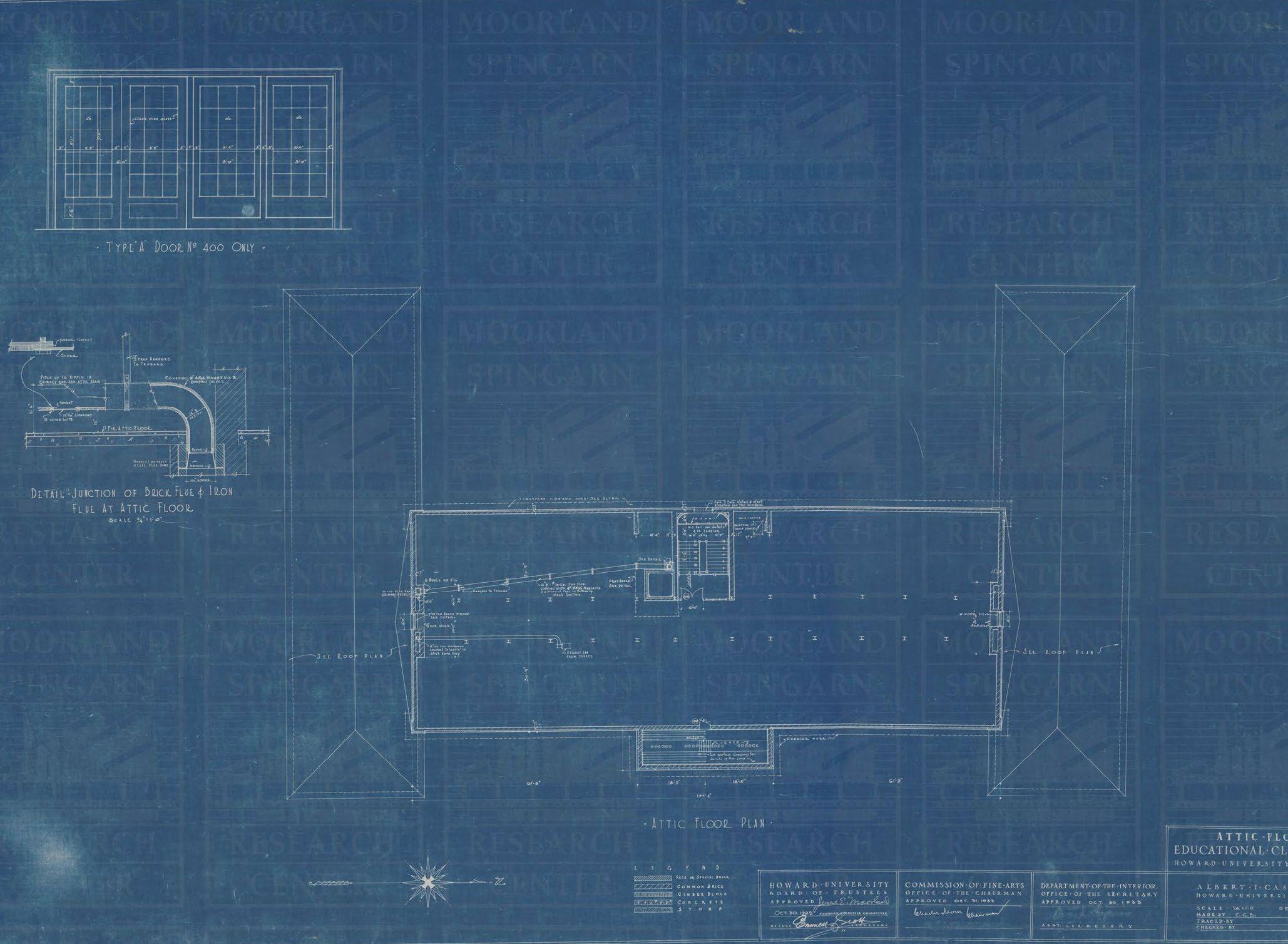

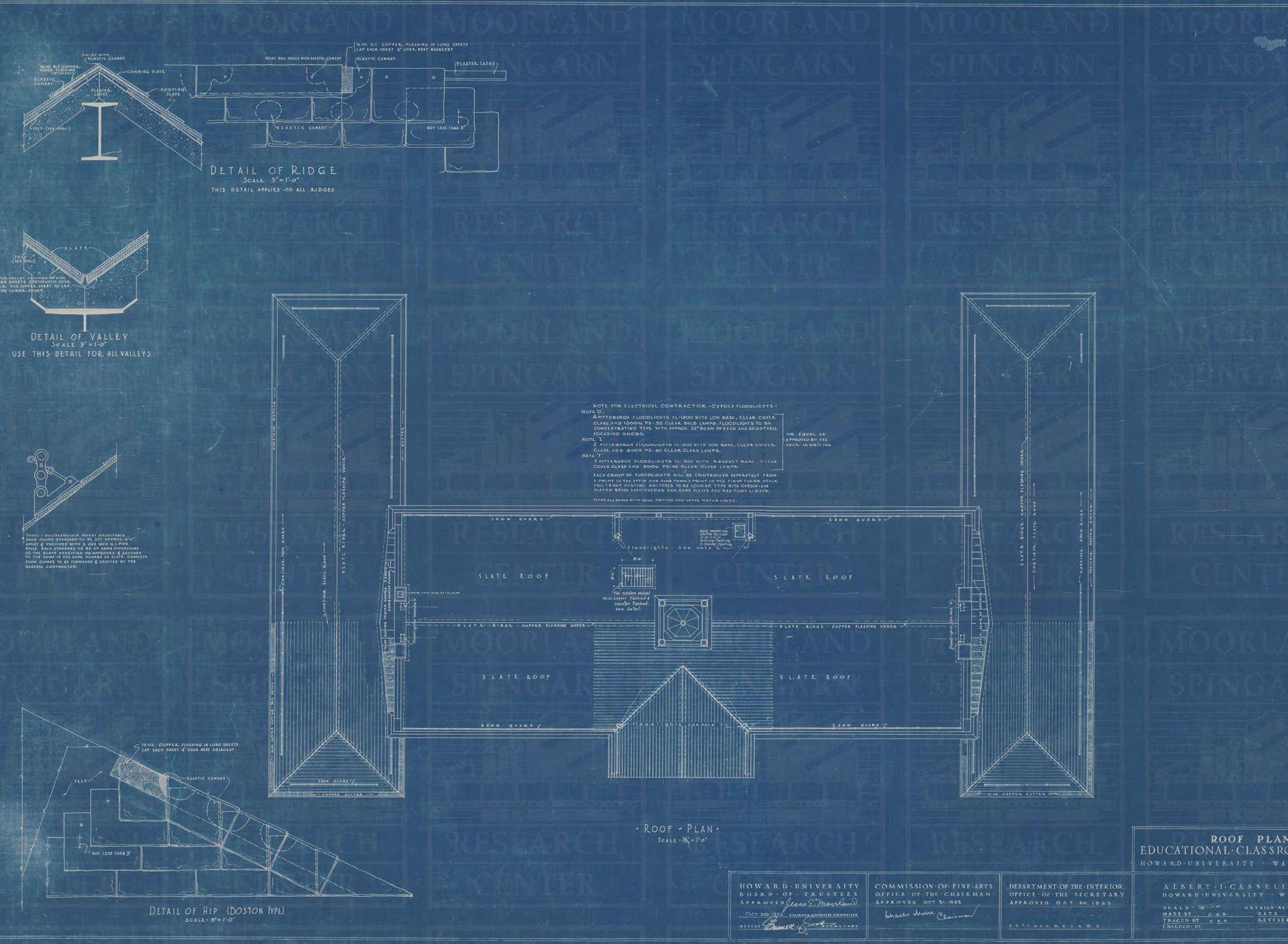

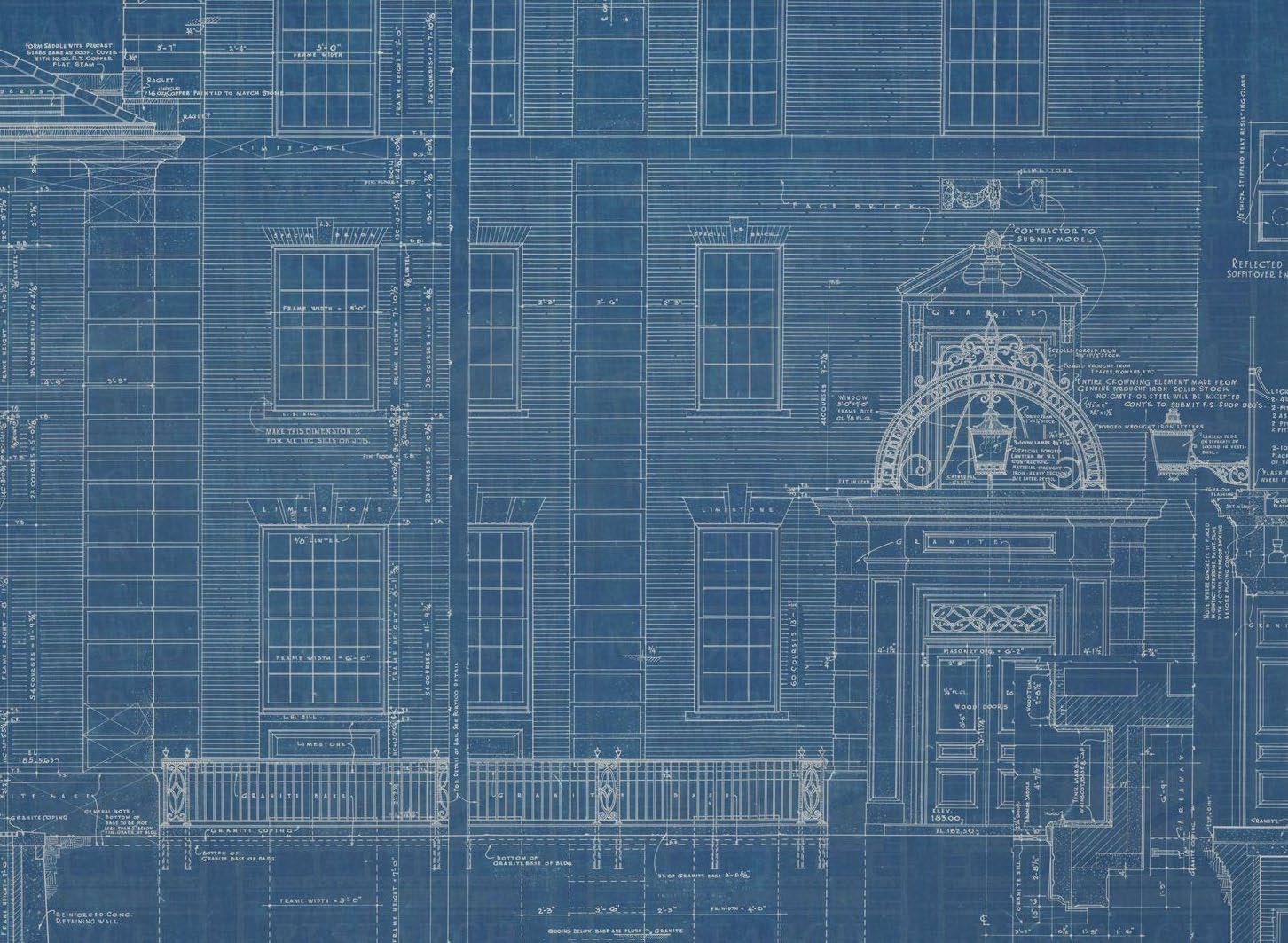

Original blueprints from the MoorlandSpingarn Research Center and Howard University Libraries show the intent of Cassell and Williston in detail, and the architecture itself, with its materials and its symbols, carries a language of heritage. Chapter 2 closes with the building’s 1935 opening ceremony, examining who spoke, who stood in witness, and how funding shaped its early identity.

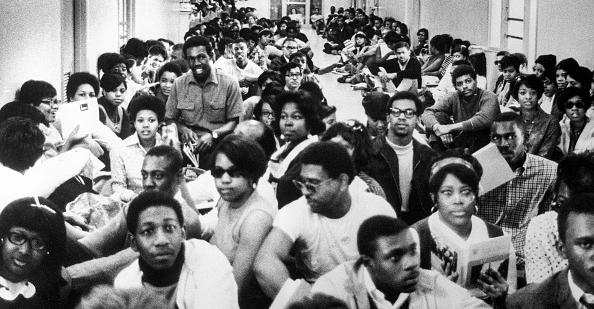

Next, we explore how Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall became a hallowed space. Over time, it emerged as a powerful symbol of equity and the ongoing pursuit of societal change. The building reflects a steadfast refusal to accept injustice and stands as a visible marker of progress. Its presence on campus has influenced national conversations and anchored generations of advocacy and scholarship.

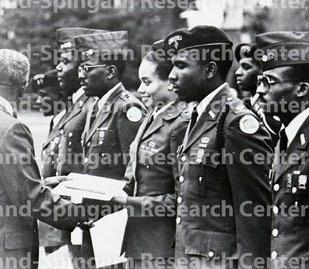

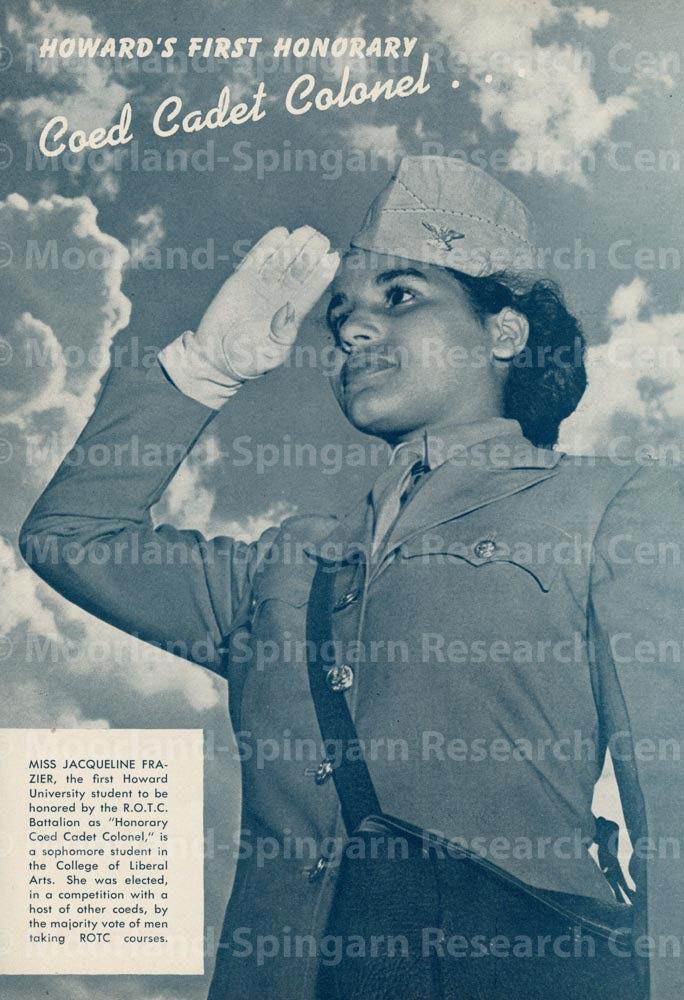

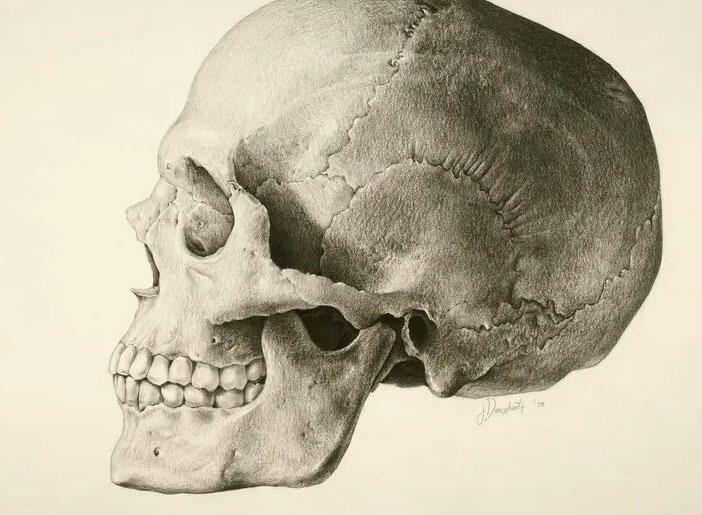

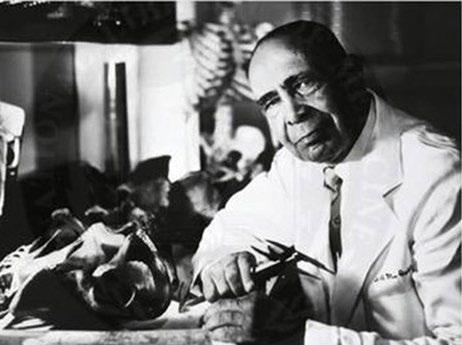

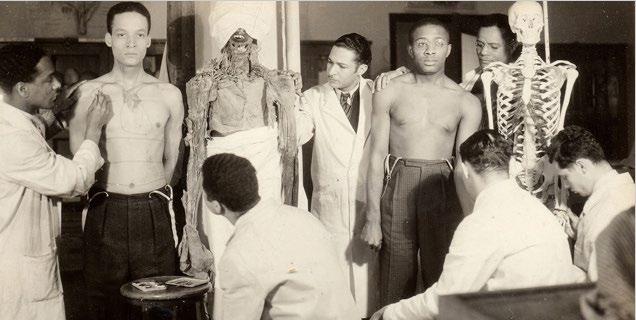

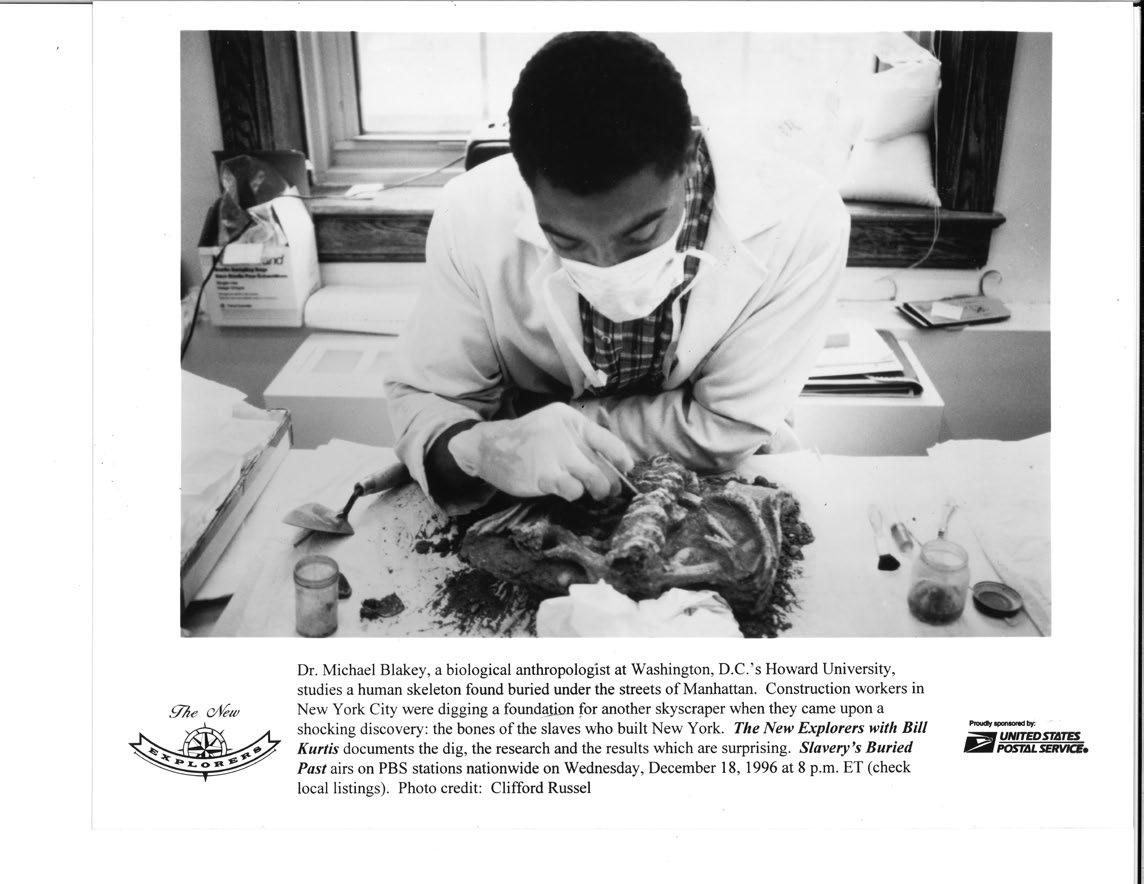

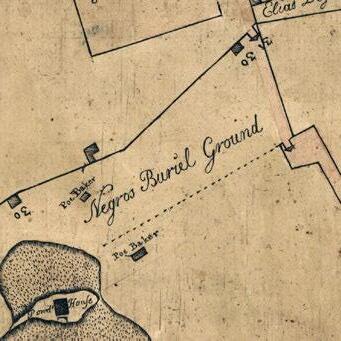

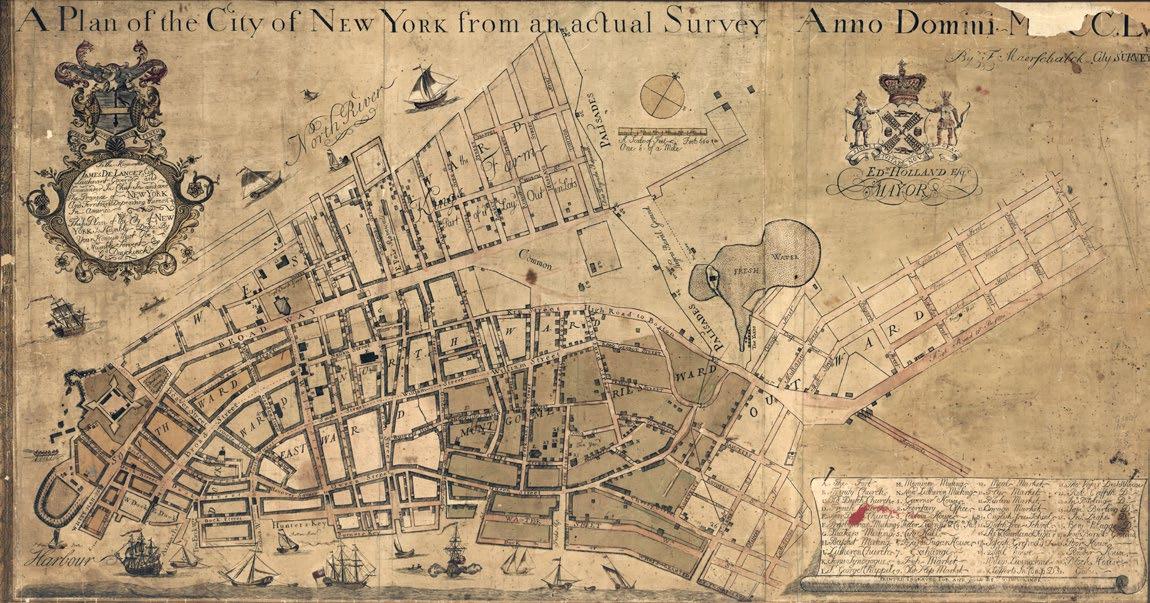

A timeline runs through chapter 3, pairing milestones from Howard University with national events. They show how Douglass Hall remains woven into our broader social consciousness. A set of program vignettes deepens that narrative, featuring the ROTC legacy, the civil rights era, the mission of The Journal of Negro Education, and “Bones of Truth,” a tribute extending the legacy of Dr. William Montague Cobb. For nearly five decades, Cobb used anatomy to expose racism and to replace the pseudoscience of racial hierarchy with evidence-based truth.

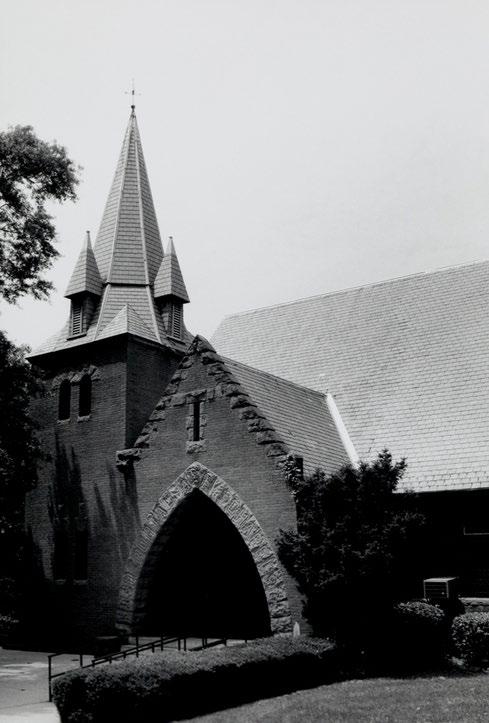

This arc of history reaches a moment of national recognition when Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall, together with Andrew Rankin Memorial Chapel and Founders Library, was named a National Historic Landmark in honor of the legal and intellectual work that helped challenge segregation.

Seventeen years later, on January 2, 2018, temperatures hovered around zero, and eighty-year-old steam lines ruptured, scalding the building and all its contents. Water poured through its core, destroying lesson plans,

original research, and archives. Still, the structure held. “Pressure and Progress,” chapter 4, recalls the night of the event and the resulting actions Howard University took to stabilize, remediate, and then renovate and modernize Douglass Hall. From a framework of the American Institute of Architecture design excellence, the chapter tracks the evolution of Douglass Hall into a highly sustainable and resilient structure to serve the next generations.

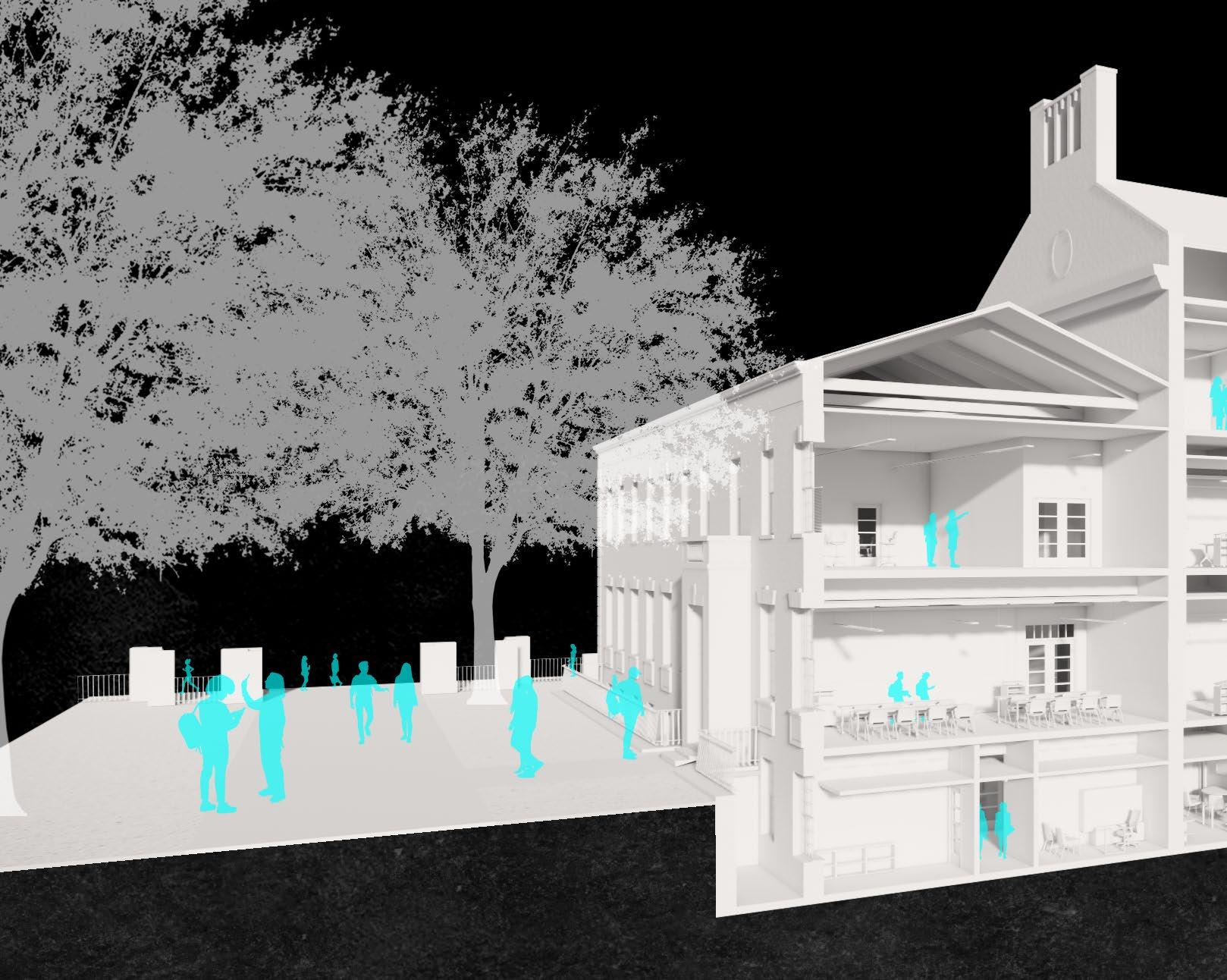

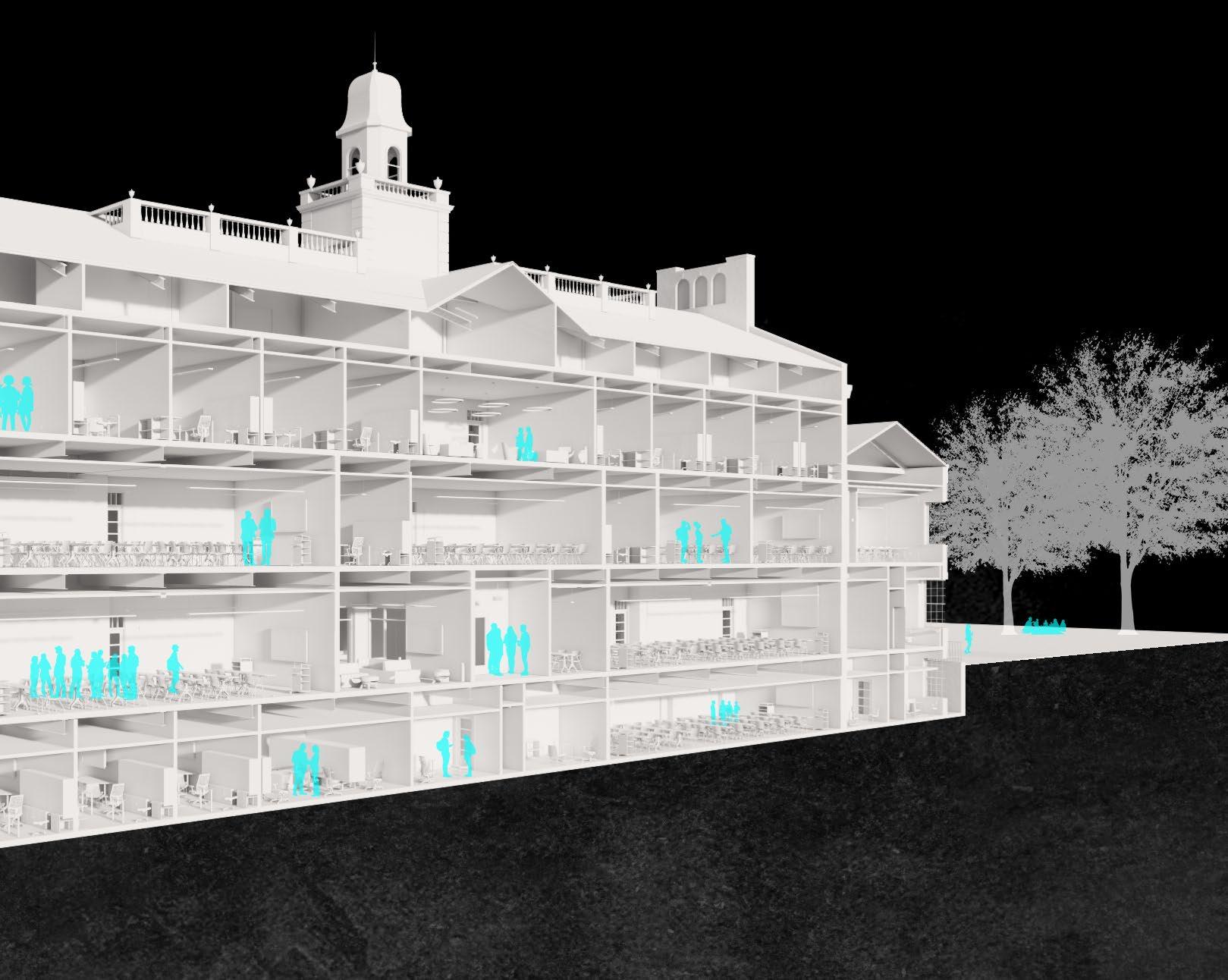

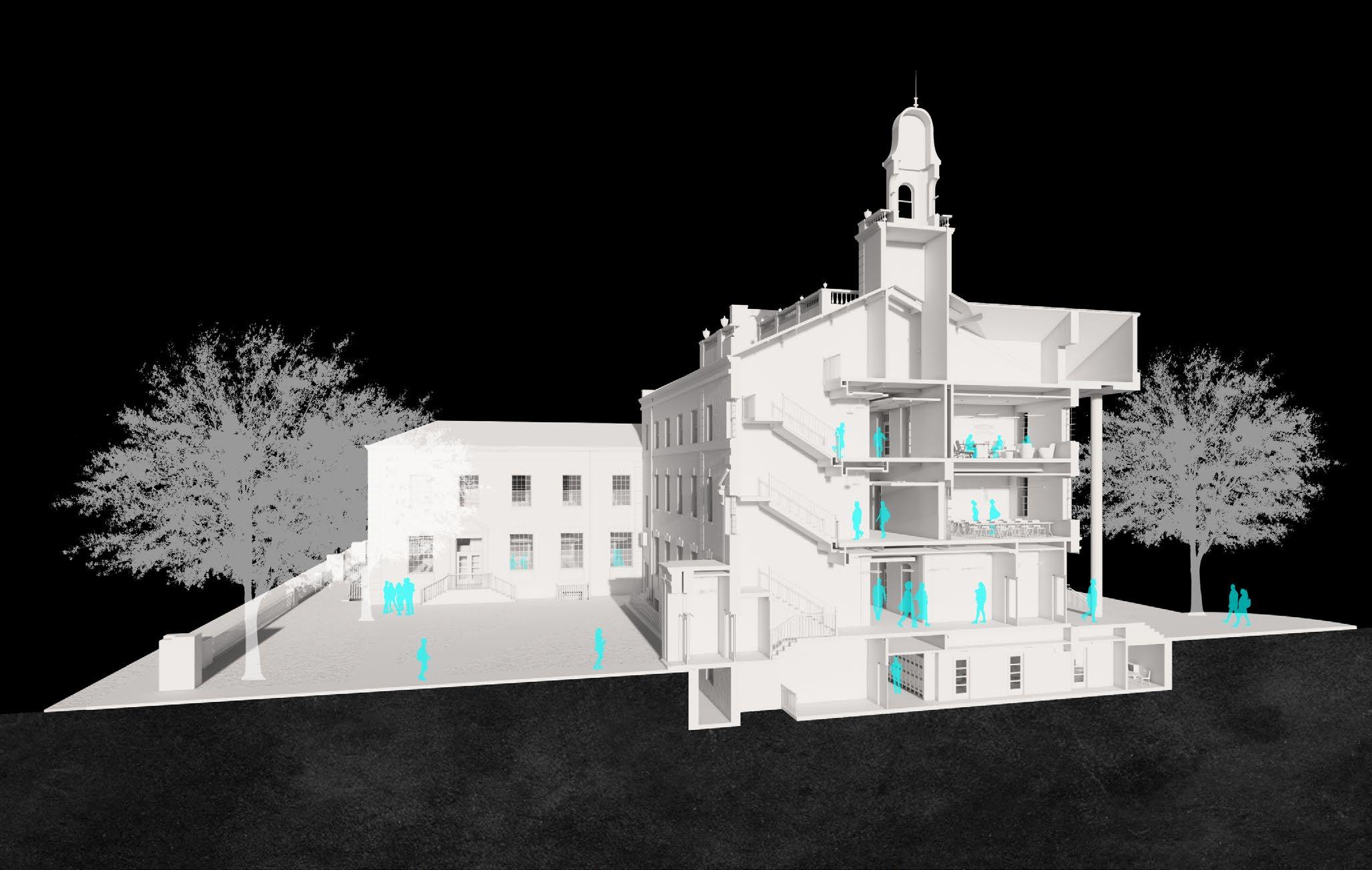

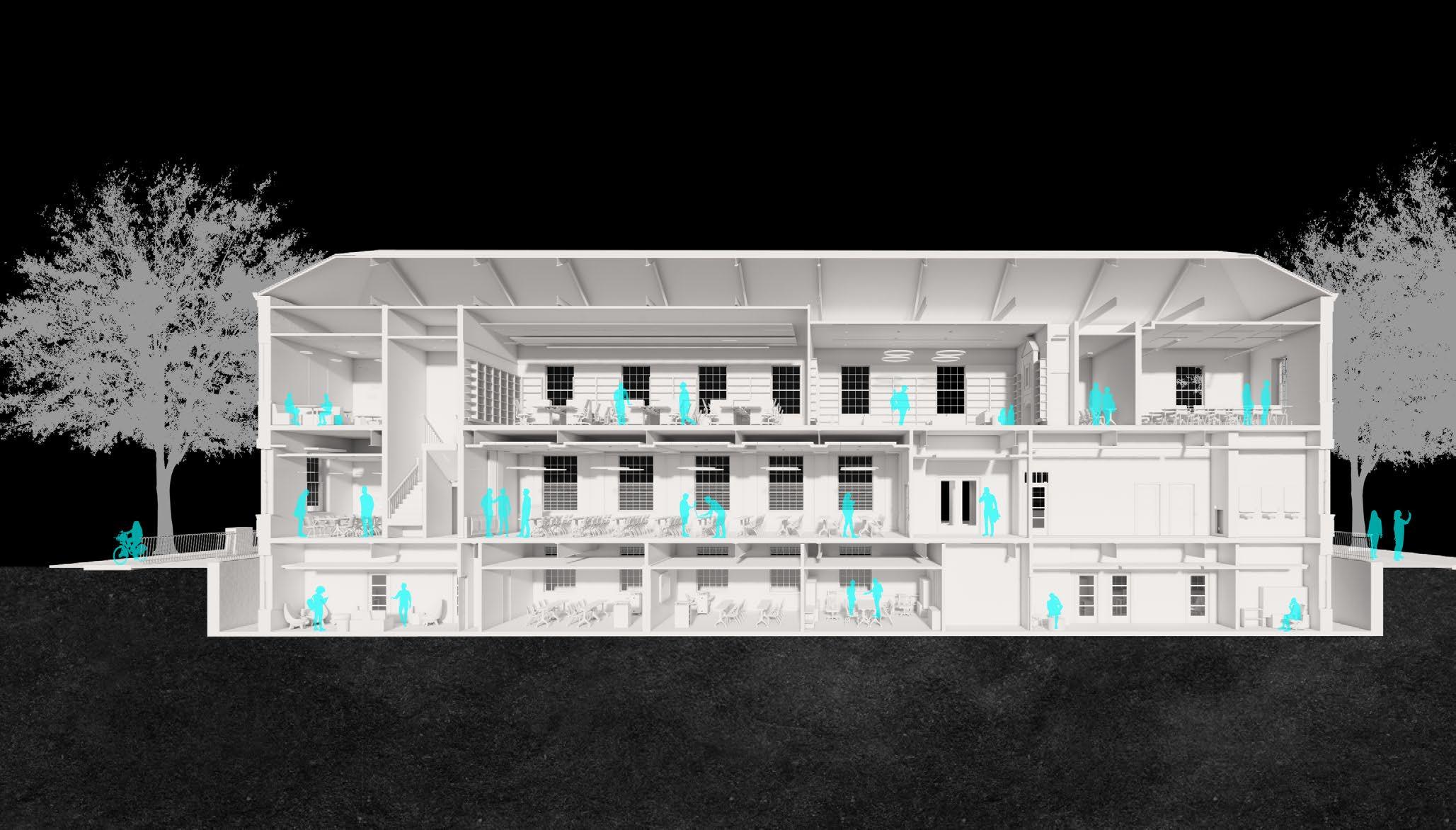

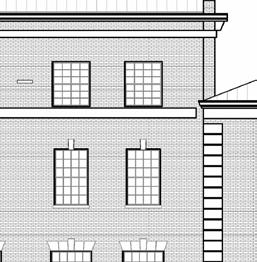

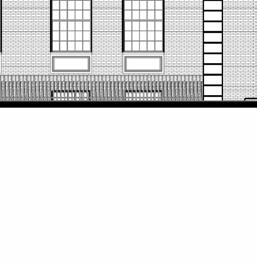

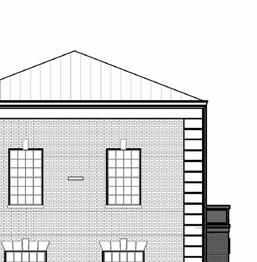

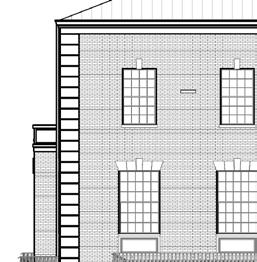

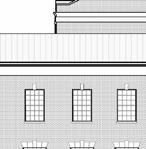

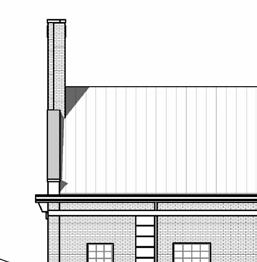

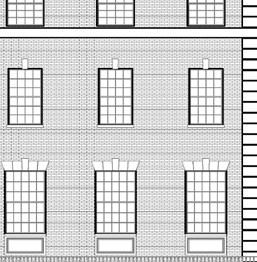

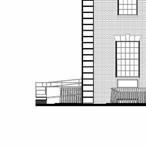

The renovation built upon memory and record, so the drawings become a vital point of return. Chapter 5 includes plans, sections, and elevations from the most recent modernization project, as well as Albert Cassell’s floor plans from the original 1933 blueprints.

Today, Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall stands ready for paths yet taken. Restored with care and equipped for the demands of modern scholarship, Douglass Hall remains a place where Howard’s mission is carried boldly into the future.

Enditatque modicid quaestis et fugia dolesero que audaesti omnimi, aute doluptur?

rooms. Today, these informal zones support collaboration, quiet reflection, and peer-topeer learning.

The first-floor corridor was opened to create a bright, inviting entry commons, a shift that created a “hall of learning” feel that anchors student experience in arrival and intention. Arched openings and original proportions were restored along the corridors, re-establishing a sense of rhythm and architectural clarity that had been obscured over time.

Teaching spaces were reassigned from individual departments to the registrar, allowing scheduling based on real-time academic needs. If political science was not meeting in the classroom, sociology could use the space. This shift unlocked capacity across the building, enabling departments to expand their offerings and collaborate more freely.

Rising prominently on the Yard, Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall houses the liberal arts at Howard University. This home for disciplines rooted in inquiry, communication, and justice echoes Douglass’s lifelong commitment to critical thinking, eloquent expression, and informed action. When the university named a building in his honor, it was an enduring recognition of his impact and an affirmation of his values. Within these walls, generations of students and faculty have wrestled with complex questions and shaped the language of progress.

Classrooms were transformed to support a shift in teaching philosophy from passive lecture delivery to active, student-centered learning. The design introduces SCALE-UP environments, where round tables, flexible layouts, and mobile instruction promote collaboration. Interactive technology supports hands-on learning across disciplines, including shared screens, writable surfaces, and modular furnishings. Select original blackboards were preserved, maintaining a visual thread between past and present.

After demolition exposed a long-forgotten plaster ceiling above a warren of old offices, the team brought in skilled artisans trained in traditional plasterwork. Using time-honored methods and custom tools, the team recreated the original etched patterns by hand, a craft that has become increasingly rare in modern construction. Though not entirely lost, such expertise is practiced by only a small community of specialists committed to historic preservation.

insisted that literacy would make Douglass “unfit” to be a slave. In that moment of prohibition, Douglass grasped a profound truth: literacy leads to agency.

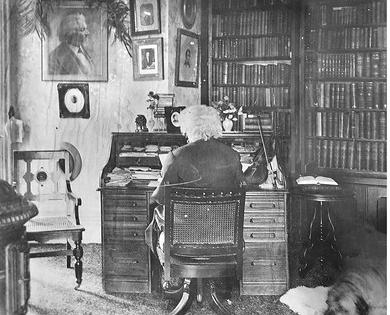

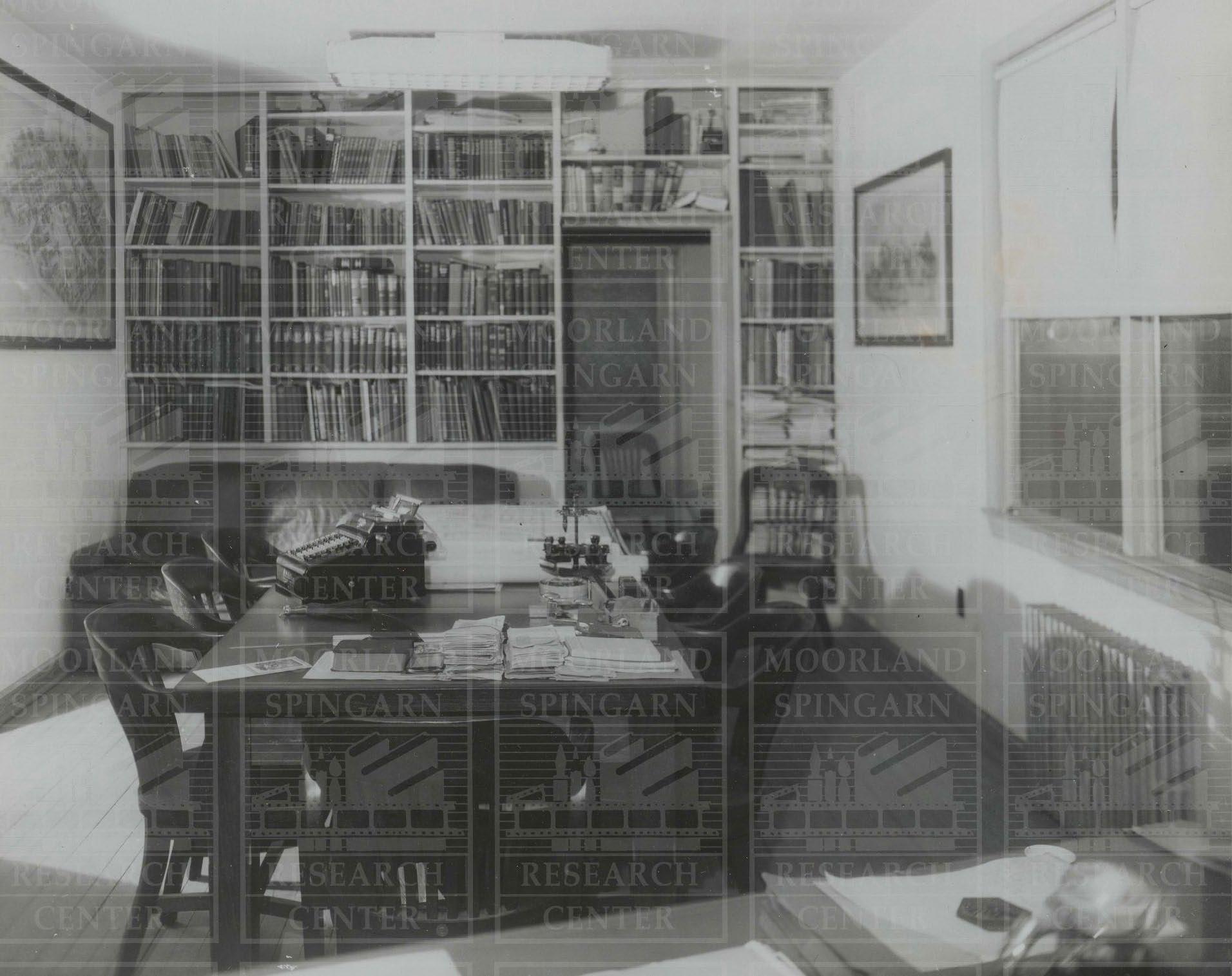

From its barrel-vaulted ceilings to its handcrafted millwork, the building required a meticulous preservation effort. In some cases, this work involved excavation and revelation. The discovery of a finely crafted fireplace, long entombed within the walls, marked the first hint of a forgotten elegance hidden beneath years of adaptation. As the restoration unfolded, ongoing efforts revealed bookshelves tucked within the frames of what had once been a grand library, their purpose obscured but never truly lost. These elements, unearthed and refinished, now stand as quiet tributes to the spirit of intellectual pursuit, evoking the timeless images of Frederick Douglass in his home library, surrounded by books, immersed in academic exploration.

Born into slavery in 1818 in Talbot County, Maryland, Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey would later choose a new name, Frederick Douglass, as part of his journey toward freedom. From his earliest years, Douglass understood education to be a gateway to emancipation. In his autobiography, he recounts how Sophia Auld, the wife of his enslaver, began teaching him to read until her husband stopped the lessons. Hugh Auld

Decoding Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall

Wood paneling, decorative plaster, and wrought-iron details were carefully restored or recreated. The team matched materials by hand and eye, guided by archival photos, field investigation, and institutional memory. Throughout the project, the team sought to build a dialogue between eras. Every restored detail reinforced the idea that Douglass Hall should feel as grounded in Howard’s legacy as it is equipped for its future.

After those first lessons with Auld, Douglass launched himself into a journey in selfdirected learning that embodied what we now recognize as the liberal arts tradition. He seized every opportunity to strengthen his facility with language, studying Webster’s spelling book, the Bible, and discarded schoolbooks. He read newspapers scavenged from the streets and traded bread for reading instruction from white children in the neighborhood. He observed, questioned, and engaged. One of the most formative texts he encountered was The Columbian Orator, a collection of essays and speeches on history, philosophy, and literature. These disciplines nurtured his critical thinking and rhetorical skills.

In 1838, at age 20, Douglass escaped enslavement by disguising himself as a sailor and traveling north. He settled jn New Bedford, Massachusetts, and then emerged into public life. In 1845, he published Narrative of the Life

In 1845, Frederick Douglass published Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, offering a powerful account of his early life in slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

“Education means emancipation. It means light and liberty. It means the uplifting of the soul of man into the glorious light of truth.”

Frederick

of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, a searing firsthand account of slavery that stirred action across the nation and beyond. His years of self-education prepared him for this moment of public emergence.

When Douglass began speaking at anti-slavery gatherings across the North and in Europe, his command of language and argument allowed him to meet the era’s most influential audiences on equal terms. He shattered stereotypes and revealed the falsehood of racial hierarchies. His speeches and writings illuminated the human cost of slavery and called for equality. In them, he revealed how education can inspire clear thinking, powerful communication, and just action. Douglass’s intellect and eloquence modeled a path by which learning reshapes self and society.

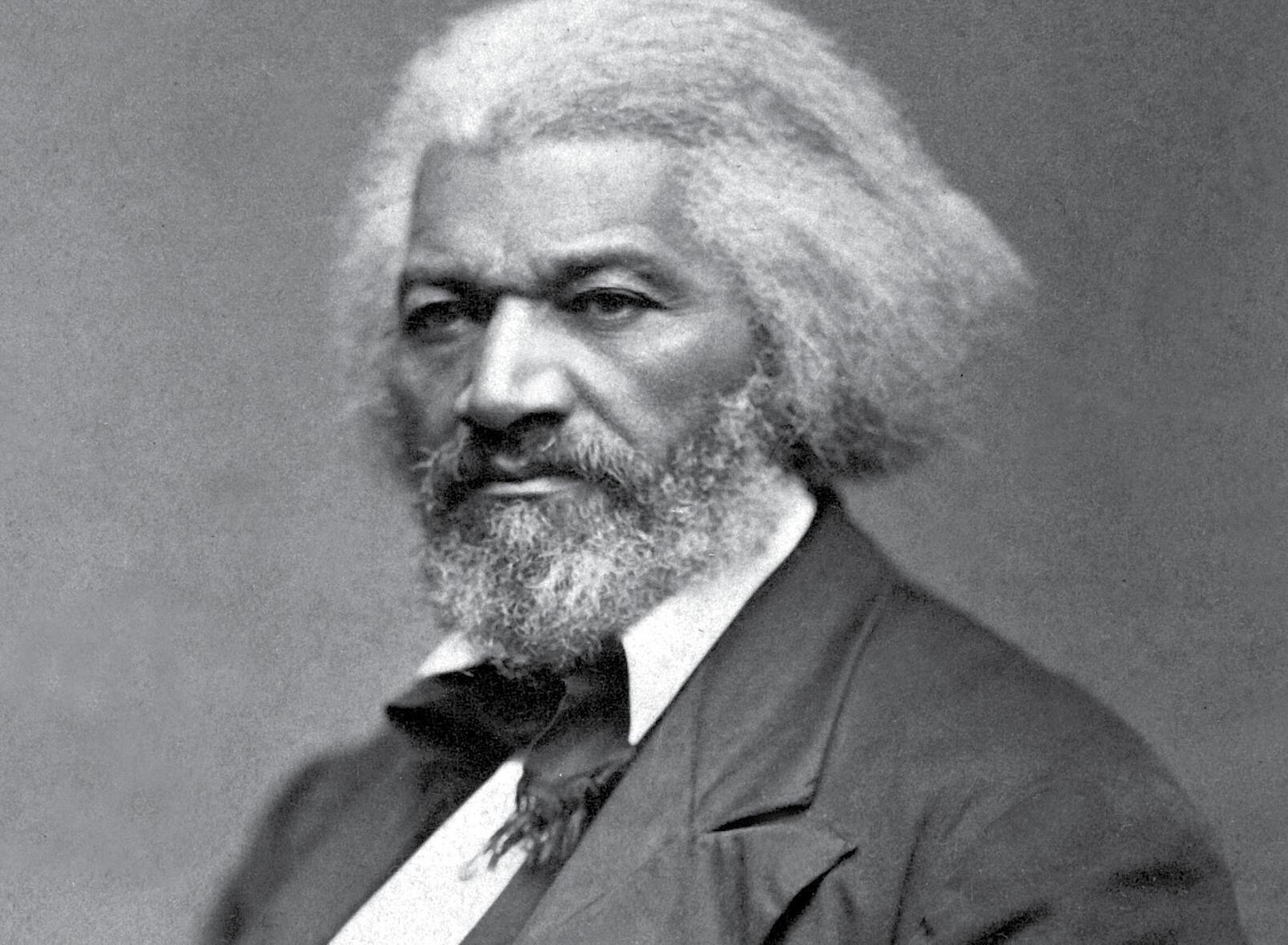

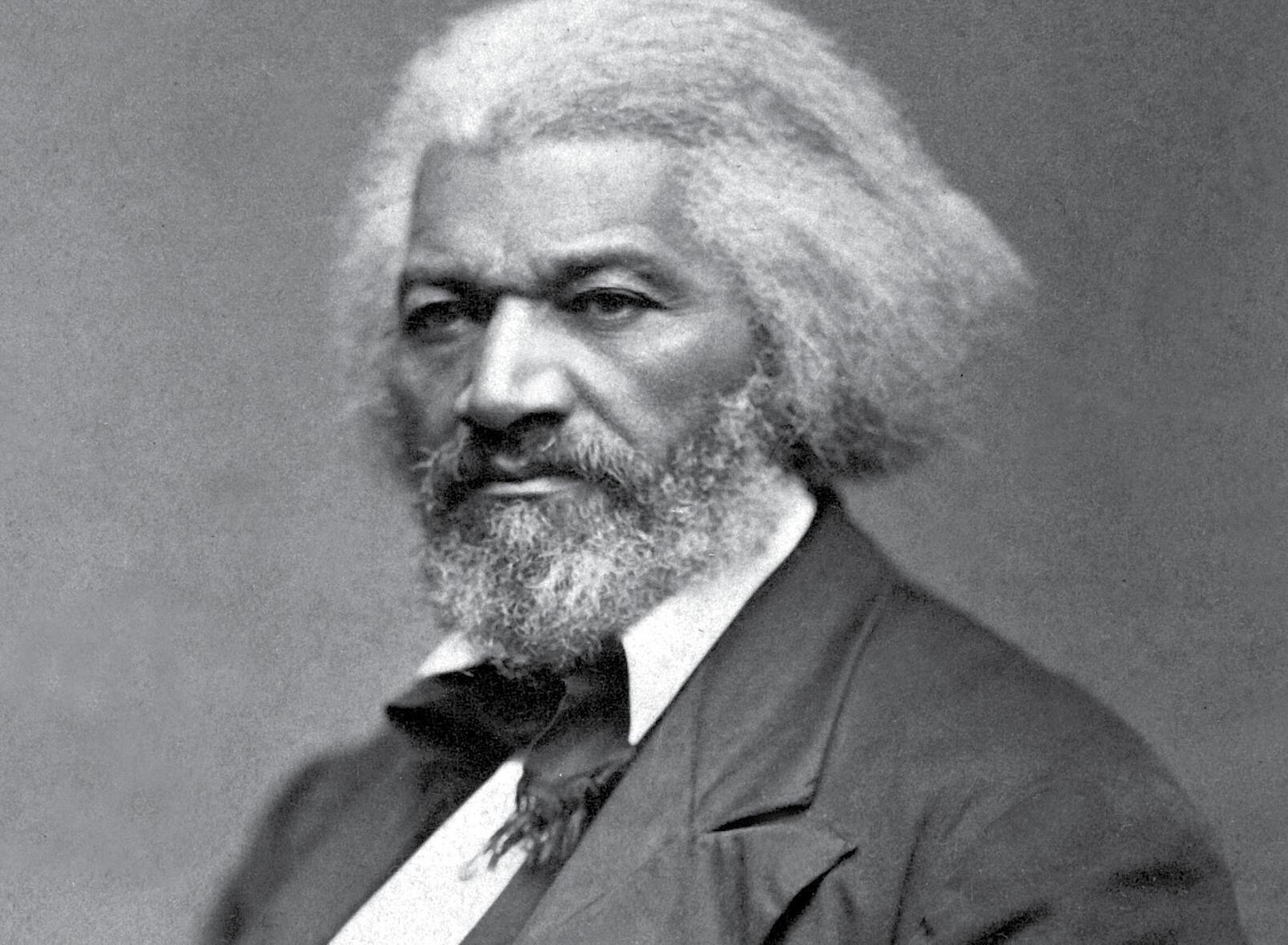

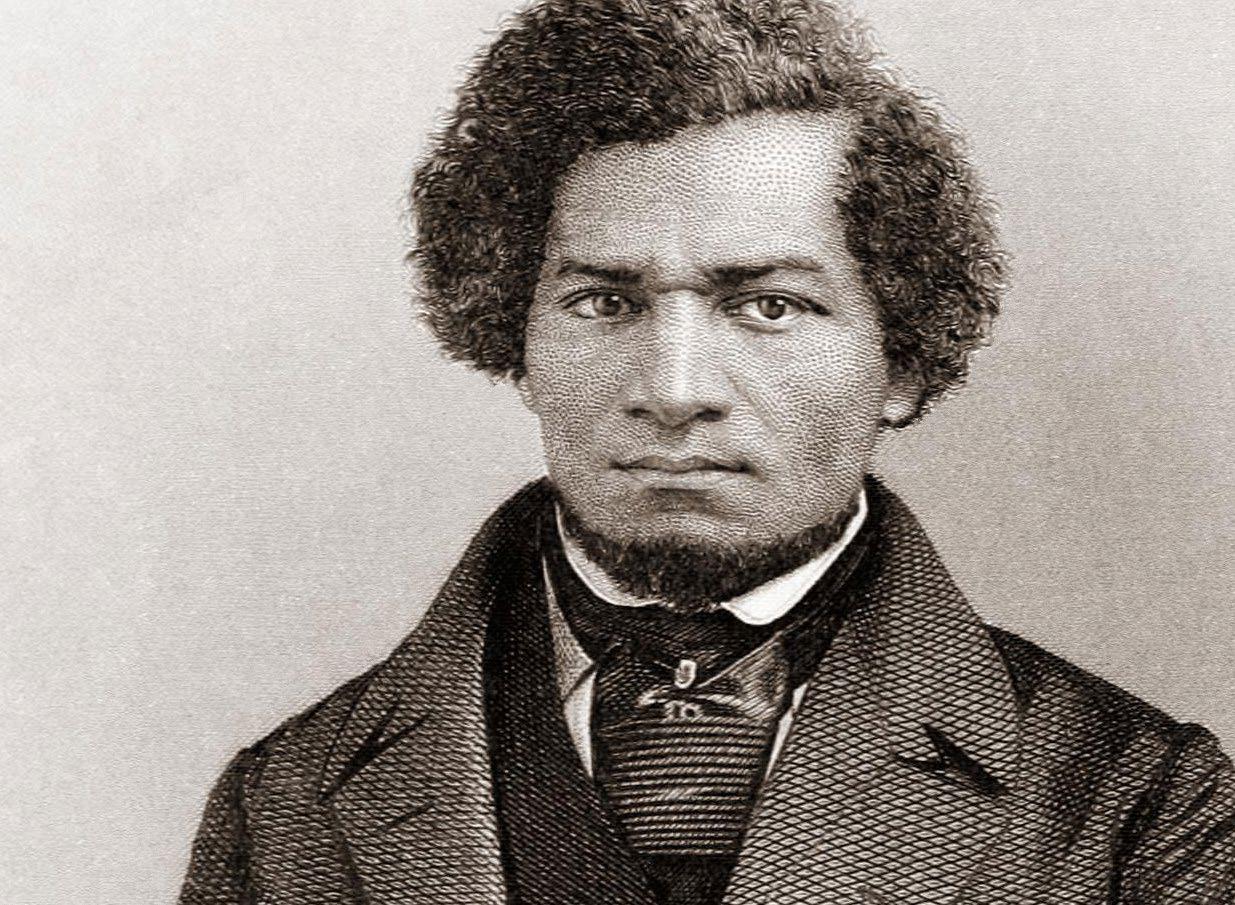

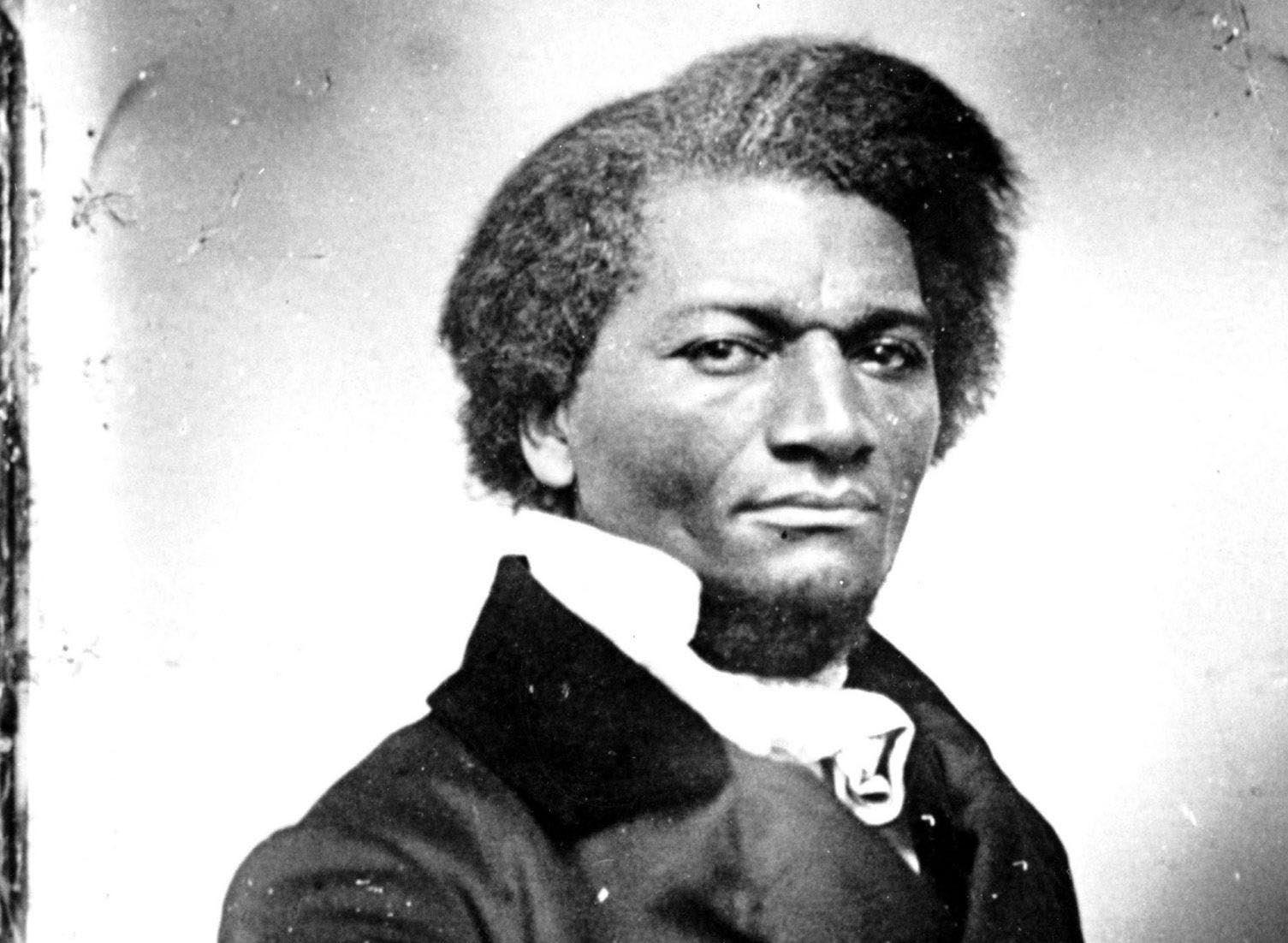

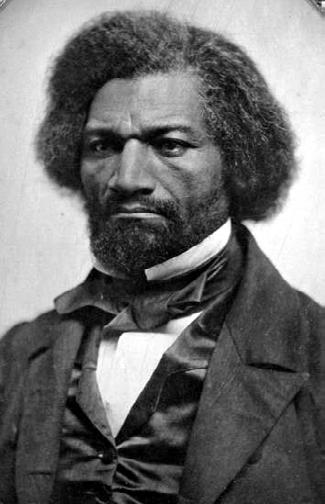

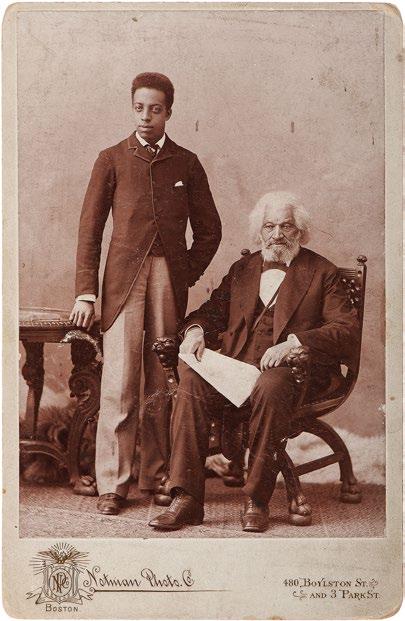

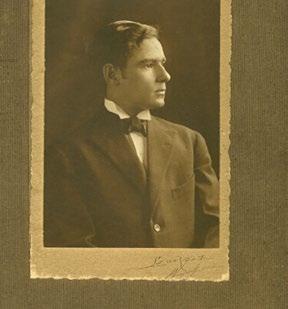

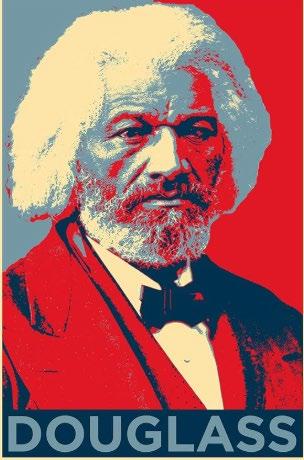

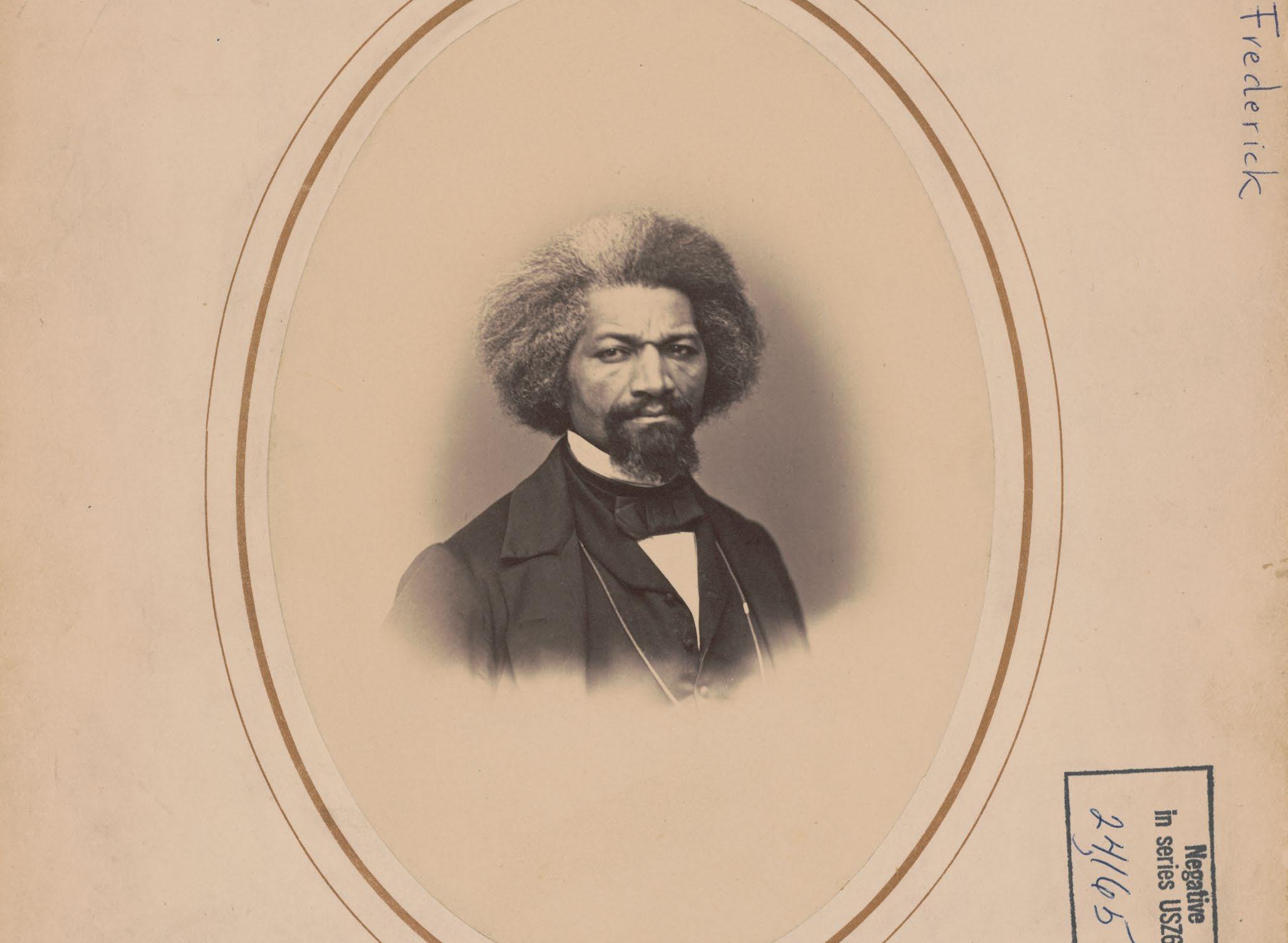

Frederick Douglass’s understanding of expression and representation extended beyond the written word. He became one of the most photographed Americans of the 19th century, using photography as a means to affirm Black dignity and counter racist stereotypes. In each portrait, Douglass

presented himself as serious, composed, and resolute. This deliberate visual strategy revealed how the humanities, including the visual arts, can bridge divides and forge understanding where words alone may falter.

His command of ideas, sharpened by study and guided by principle, found powerful outlets in print and speech. In 1847, Douglass founded The North Star, a newspaper that became a vital platform for abolitionist advocacy and Black intellectual culture. The paper’s writing, analysis, and dialogue shaped opinion and advanced equality. Through this endeavor and his speaking tours, Douglass collaborated with leading abolitionists and reformers, including William Lloyd Garrison, Gerrit Smith, Sojourner Truth, John Brown, and Harriet Tubman. The work anchored him in the heart of 19th-century debates on freedom, citizenship, and democracy.

Douglass’s influential presence allowed him to navigate fluidly across movements and audiences. In 1848, he participated in the Seneca Falls Convention, invited by Elizabeth M’Clintock, a Quaker abolitionist and advocate

1856 Portrait of Douglass. When this portrait was taken, mainstream depictions of Black Americans cast them as uneducated laborers, a caricature rooted in racism and control. Douglass understood the power of a photo to assist in changing that narrative.

Douglass, The Blessings of Liberty and Education, September 3, 1894 3

“To deny education to any people ... is to deny them the means of freedom and the rightful pursuit of happiness, and to defeat the very end of their being.”

Frederick Douglass, The Blessings of Liberty and Education, September 3, 1894

whose collaboration with Douglass reflected alliances across race and gender, grounded in shared ideals. Douglass was the only Black man known to speak at the Seneca Falls Convention, where he voiced strong support for the resolution on women’s suffrage. He viewed the struggle for gender equality as inseparable from the broader pursuit of justice and human rights. His ability to see connections and build coalitions captures the essence of the liberal arts mindset.

When Frederick Douglass joined Howard University’s Board of Trustees in 1871, the institution was still defining its future. Over the next quarter century, Douglass played a crucial role in shaping the institution’s early identity. His correspondence from this era reveals a man deeply engaged with the practical challenges of academia, assessing student concerns, weighing institutional decisions, and offering clear-eyed guidance during the university’s formative years.

Douglass balanced his duties at Howard with posts that placed him in local and national leadership. He served as US marshal for D.C.

(1877–1881), recorder of deeds for D.C. (1881–1886), and eventually as minister resident and consul general to Haiti (1889–1891). His career included advisory meetings with presidents, from Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War to Rutherford B. Hayes during Reconstruction. Although he did not seek the nomination, Douglass’s name was placed on the Equal Rights Party ticket in 1872 alongside Victoria Woodhull, underscoring his prominence and influence. These roles widened Douglass’s platform, enabling him to connect political power with cultural leadership in ways few of his era could.

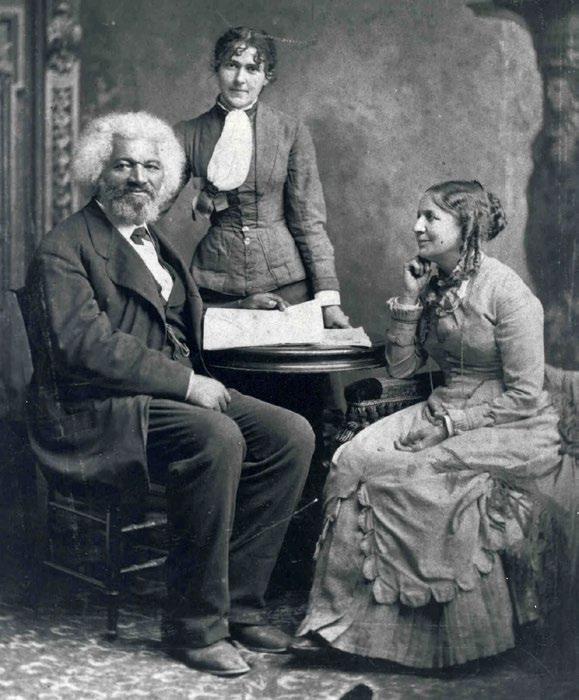

His personal relationships reflected the same integrity that marked his public work. His first wife, Anna Murray Douglass, supported his escape from slavery and helped turn their Rochester home into a safe haven on the Underground Railroad. After Anna’s passing in 1882, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a white feminist and former secretary in his Washington office. Their interracial marriage provoked national controversy, as critics fixated on their age and racial differences. After Douglass’s death, Pitts helped preserve

his legacy by founding the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association, safeguarding his papers and correspondence. Their union reflected a shared commitment to moral courage and the conviction that individuals must challenge unjust conventions and act on principle.

In his later years, Douglass published his final autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881, revised 1892). This expansive memoir built on the deeper reflections of his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), and chronicled his rise from servitude to statesmanship. Together, these narratives offer a sweeping view of one man’s transformation and the nation’s unfinished struggle with the legacy of slavery. Life and Times remains one of the most comprehensive reflections on American democracy written by someone who had been excluded from it by birth.

Douglass remained active in his advanced years, continuing to write, travel, and speak across the country. On February 20, 1895, after addressing a women’s rights meeting of the

Top: Douglass in his study at Cedar Hill, his home in Washington, D.C. Bottom left: Douglass with his second wife, Helen Pitts Douglass (sitting), and her sister, Eva Pitts. Bottom right: 1894 cabinet card photograph of Douglass with his grandson, Joseph Henry Douglass, an internationally renowned concert violinist.

National Council of Women in Washington, D.C., Douglass returned home and succumbed to a heart attack that evening. He was 77.

Naming Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall for him affirms the values that shaped his life and continue to guide Howard University’s mission. Denied a formal education, Douglass taught himself through reading, observation, and dialogue. He used that knowledge to challenge injustice, shape civic thought, and expand the nation’s moral imagination. His journey reflects the purpose of the liberal arts: to cultivate minds that think critically, speak with clarity, and act with conviction.

Frederick Douglass’s story still resonates. It calls us to embrace the liberal arts as essential to a thriving democracy. It reminds us that education must nurture intellectual independence and ethical responsibility, a commitment Douglass upheld through his lifelong pursuit of knowledge and his insistence on linking learning to civic action. That spirit continues to shape Douglass Hall. Its recent modernization ensures the building remains a place for bold inquiry and meaningful action.

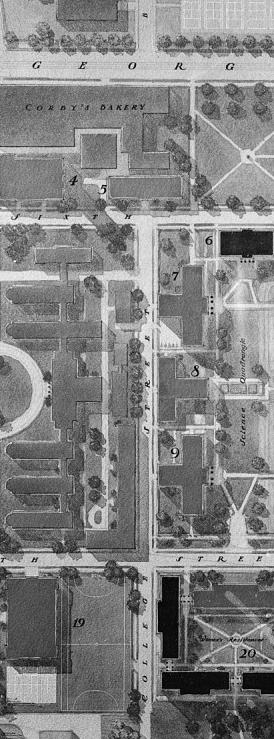

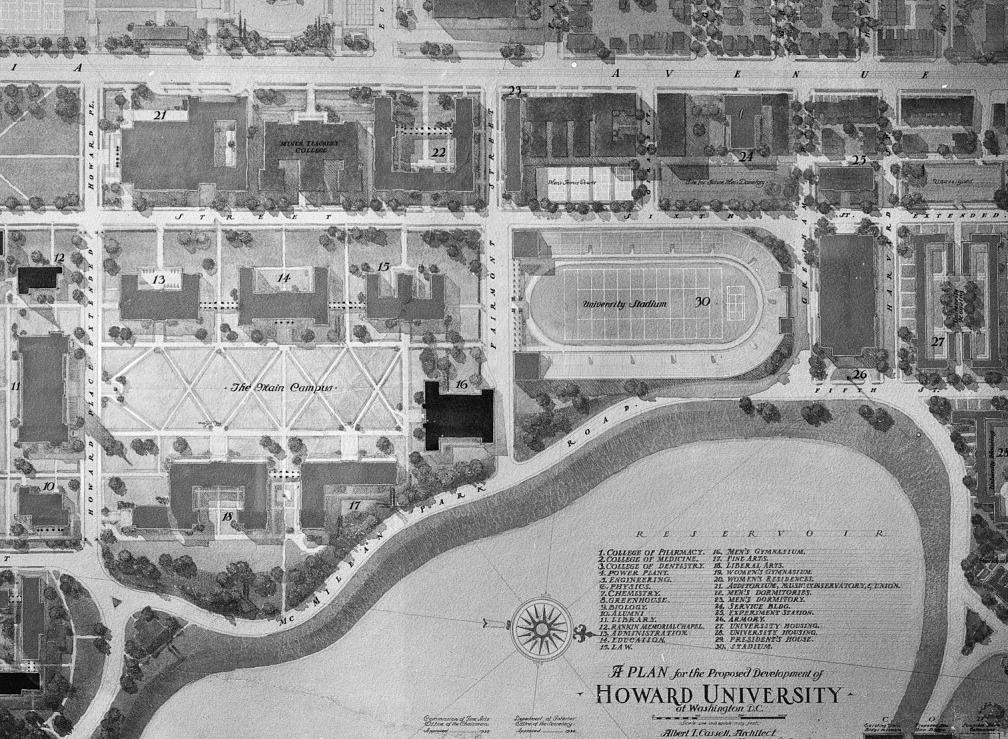

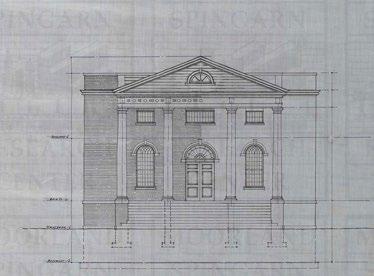

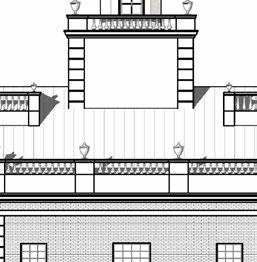

Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall was the first building constructed on Howard University’s campus as part of a cohesive architectural vision. That approach emerged from the 1932 Plan for the Proposed Development of Howard University, in which University Architect Albert Irvin Cassell designated it as Building 14. The structure embodied the institution’s values in form and material, shaping movement, hierarchy, memory, identity, and ambition across campus.

Currently, Howard University’s central campus reflects five distinct development phases, each influenced by university leadership, campus master plans, and architectural trends:

• 1867–1919: Founding period and early campus development evolving from informal building arrangements toward a unified pattern, organizing academic buildings around a central lawn

• 1920s–1949: Early 20th century and New Deal-era construction under University President Mordecai Johnson and architect Albert Irvin Cassell’s 1932 master plan

• 1950–1965: Modern era buildings influenced by the 1951 GSA (US General Services Administration) master plan

• 1966–1990s: Late 20th-century development guided by campus plans from 1966, 1971, 1975, 1986, and 1997

• 2000–2019: Early 21st-century development following the 2011 master plan

• 2020–2030: The Central Campus Plan pursues a balance between a heritage of preservation and propelling innovation and strategic, sustainable growth, aiming to activate the campus with new academic programs and structures

By the early 20th century, the US Department of the Interior, which oversaw the campus, recognized that many Howard facilities were in poor condition. In 1919, the US Department of Agriculture was tasked with creating a development plan for the university. The department’s proposal preserved the campus’s pastoral character, while replacing its informal layout with a unified development pattern that

Albert Cassell’s 1932 Plan for the Proposed Development of Howard University (Building 14,

“The Cassell plan is really the foundational plan on which the modern campus is built.”

Derrek Niec-Williams, Howard University Assistant Vice President for Planning and Architecture, 2022

grouped academic buildings around expansive open spaces. Regrettably, this initial plan remained unimplemented.

A turning point came in June 1926 when Dr. Mordecai Wyatt Johnson became Howard’s first Black president, a position he held until 1960. Throughout his 34-year tenure, Johnson established Howard as a center of excellence for African Americans. His influence extended beyond academia and included a deep interest in improving the university’s physical environment.

For the first time in the history of the university, President Johnson called upon Black design professionals to plan and implement campus improvements. Howard’s expansion coincided with substantial federal investment during the administration of President Herbert Hoover (1929–1933). Administered through the Department of the Interior, this work included a 1929 planning initiative that helped shape a long-term campus development plan. In 1930, Hoover signed legislation raising Howard’s annual federal appropriation from $385,000 to $1 million, a pivotal move that allowed the university to modernize and expand its campus infrastructure.

In 1922, Johnson created the university architect position, appointing Albert Irvin Cassell, an African American Cornell University architecture graduate who had joined Howard in 1920 as an assistant professor. As university architect, Cassell conducted a comprehensive campus survey that resulted in the 1932 Plan for the Proposed Development of Howard University. His plan introduced a formal arrangement reflecting symmetry and elegance, transforming the campus into an architecturally cohesive unit influenced by Beaux-Arts, Neoclassical Revival, and Colonial Revival styles.

The momentum that began under President Hoover continued into the Roosevelt administration, where the New Deal ushered in an era of federal investment in public institutions, including Howard University. Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s leadership, New Deal agencies such as the Public Works Administration (PWA) provided critical funding for campus expansion. These resources enabled the construction of major academic buildings, including Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall (1935), the Chemistry Building (1936), and the iconic Founders Library (1937). Together, these projects embodied the

university’s aspirations and the federal government’s growing commitment to Black higher education during the Great Depression.

Cassell designed buildings in the Georgian Revival style, arranged symmetrically around the main and lower quadrangles. He partnered with David Williston, America’s first professionally trained Black landscape architect, to create formal plantings, tree-lined pathways, and gardens at strategic locations. Thanks to the increased federal funding under Hoover and Roosevelt, Howard’s budget tripled, making it possible to execute Cassell’s vision of a formal, monumental campus, one that expressed dignity, permanence, and the rising intellectual and cultural ambitions of Black America.

After Cassell’s departure as university architect in 1938 following disagreements with the administration, other Black architects received commissions. Hilyard R. Robinson and Paul R. Williams designed Cook Hall, a men’s dormitory sited and styled in accordance with Cassell’s plan. The final major building from this era, funded through the Public Works Administration, was a tuberculosis annex at Freedmen’s Hospital, completed in 1941.

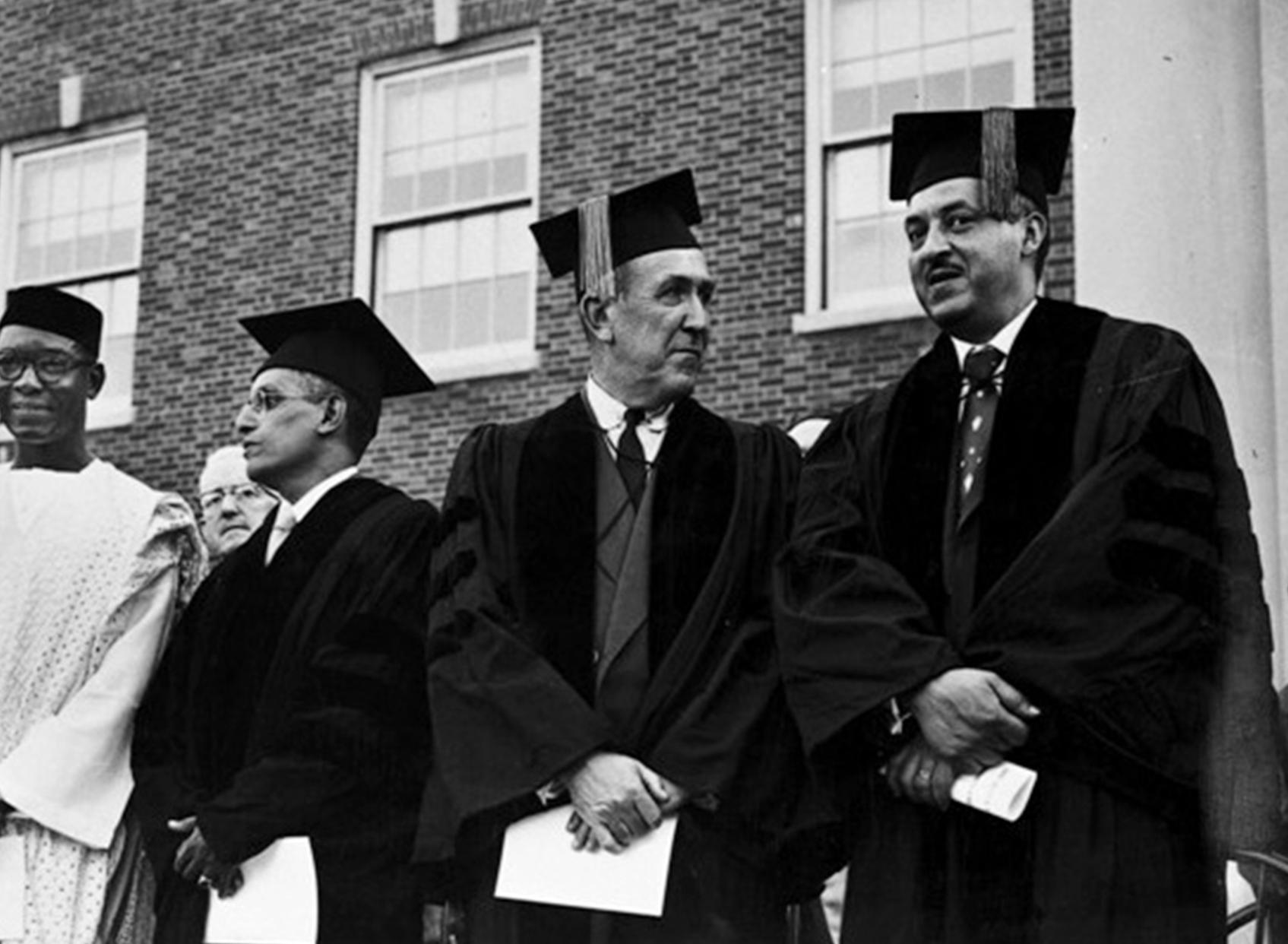

“What is the quality of your intent? When we intend to do good, we do … What each of us must come to realize is that our intent always comes through.”

Thurgood Marshall’s speech receiving the Liberty Award on July 4, 1992

Enditatque modicid quaestis et fugia dolesero que audaesti omnimi, aute doluptur?

rooms. Today, these informal zones support collaboration, quiet reflection, and peer-topeer learning.

The first-floor corridor was opened to create a bright, inviting entry commons, a shift that created a “hall of learning” feel that anchors student experience in arrival and intention.

Arched openings and original proportions were restored along the corridors, re-establishing a sense of rhythm and architectural clarity that had been obscured over time.

Classrooms were transformed to support a shift in teaching philosophy from passive lecture delivery to active, student-centered learning. The design introduces SCALE-UP environments, where round tables, flexible layouts, and mobile instruction promote collaboration. Interactive technology supports hands-on learning across disciplines, including shared screens, writable surfaces, and modular furnishings. Select original blackboards were preserved, maintaining a visual thread between past and present.

The Beaux-Arts framework informed the design of Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall. Located along the edge of the Yard, Douglass Hall helps define and frame this central open space, which reflects the classical quadrangle of historic academic campuses. This spatial organization places Douglass Hall and the Yard in deliberate dialogue, where the building’s classical features mirror the landscape’s orderly, civic character, reinforcing values of tradition, discipline, and progress. The building stands as an expression of Howard’s mission and a testament to the classical training that Albert Irwin Cassell and David Williston translated into a modern Black institutional context.

Teaching spaces were reassigned from individual departments to the registrar, allowing scheduling based on real-time academic needs. If political science was not meeting in the classroom, sociology could use the space. This shift unlocked capacity across the building, enabling departments to expand their offerings and collaborate more freely.

From its barrel-vaulted ceilings to its handcrafted millwork, the building required a meticulous preservation effort. In some cases, this work involved excavation and revelation. The discovery of a finely crafted fireplace, long entombed within the walls, marked the first hint of a forgotten elegance hidden beneath years of adaptation. As the restoration unfolded, ongoing efforts revealed bookshelves tucked within the frames of what had once been a grand library, their purpose obscured but never truly lost. These elements, unearthed and refinished, now stand as quiet tributes to the spirit of intellectual pursuit, evoking the timeless images of Frederick Douglass in his home library, surrounded by books, immersed in academic exploration.

Designing with intent is a core tenet of the classical tradition. That commitment to purposeful design was deeply embedded in the training Williston and Cassell received at Cornell University, where landscape and architectural disciplines drew heavily from the principles of the École des Beaux-Arts. Williston, graduating in 1898 as the first professionally trained African American landscape architect, received instruction in ordered spatial composition, axial organization,

After demolition exposed a long-forgotten plaster ceiling above a warren of old offices, the team brought in skilled artisans trained in traditional plasterwork. Using time-honored methods and custom tools, the team recreated the original etched patterns by hand, a craft that has become increasingly rare in modern construction. Though not entirely lost, such expertise is practiced by only a small community of specialists committed to historic preservation.

and the integration of site and structure. Likewise, when Cassell enrolled in 1917, the curriculum emphasized historical precedent, idealized forms, and symbolic composition. Students were taught to conceive buildings not just as utilitarian enclosures but as expressions of institutional meaning articulated through elements drawn from classical antiquity.

Wood paneling, decorative plaster, and wrought-iron details were carefully restored or recreated. The team matched materials by hand and eye, guided by archival photos, field investigation, and institutional memory. Throughout the project, the team sought to build a dialogue between eras. Every restored detail reinforced the idea that Douglass Hall should feel as grounded in Howard’s legacy as it is equipped for its future.

Profession

Born

Education

Role at Howard

Signature Style

Major Contributions at Howard Legacy

Landscape Architect

1868, North Carolina

Cornell University

Bachelor of Science in Agriculture (1898)

Landscape Architect

Classical landscape geometry, native planting

Shaped the campus through landscape design, planning, and preservation of open green space

Defined the user experience of HBCU campuses through landscape design guided by utility and beauty

Architect

1895, Maryland

Cornell University

Bachelor of Architecture (1919)

University Architect and Master Planner

Colonial Revival, Beaux-Arts symmetry

Campus planning and design of Douglass Hall, Founders Library, the Women’s Dormitory, and more, establishing a cohesive academic core

Comprehensive campus planning, institution-defining architecture such as Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall, and a lifelong commitment to mentoring the next generation of Black designers

Additional Work

Designed landscapes for numerous HBCUs, residential and civic projects, public parks, and memorials

Designed buildings for HBCUs, civic landmarks, and planned communities; advanced architecture through education, mentorship, and vision

“You have broken across all customary and well-trodden paths into a new field.”

President

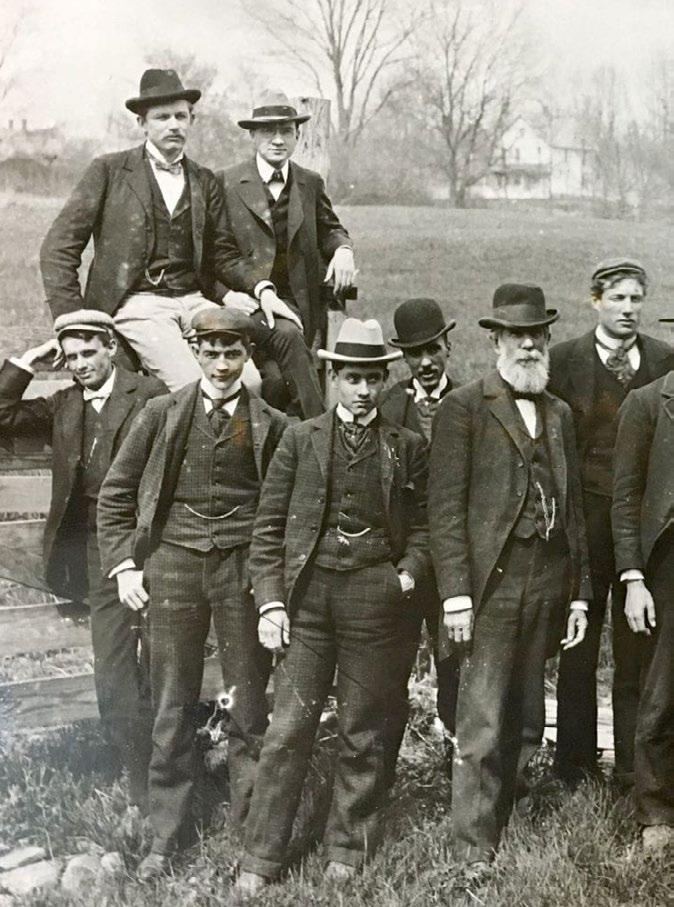

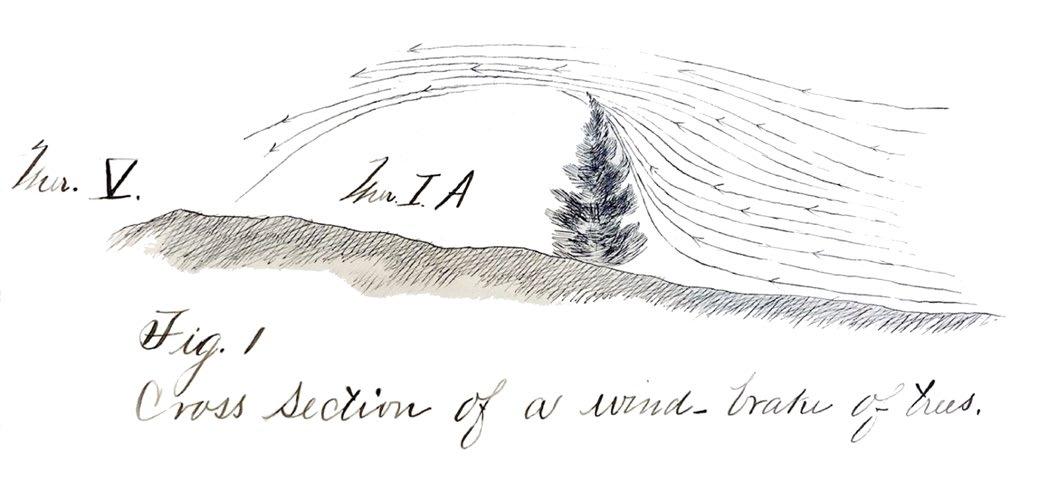

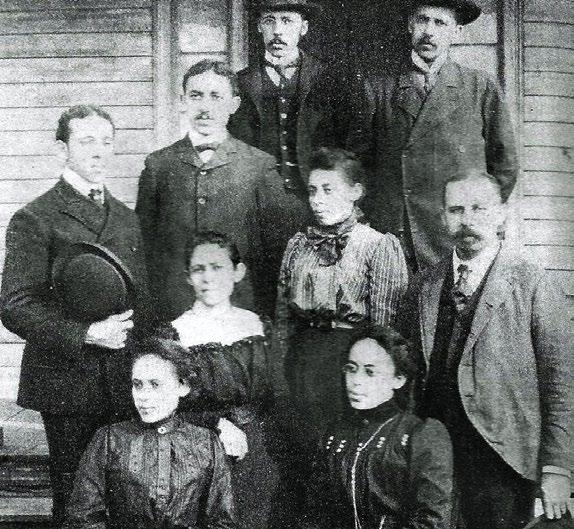

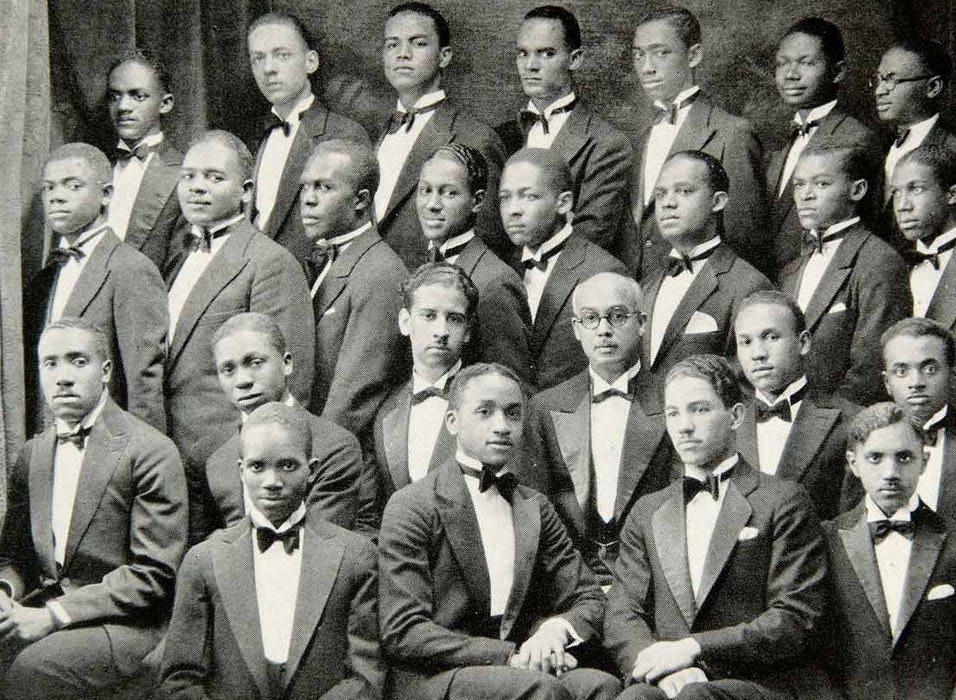

Late 1890s image of David Williston (fifth from right) with the College of Agriculture Professor and Dean Isaac Roberts (bearded, center) and other Cornell University classmates. Right: A hand sketch by Williston appears in his thesis, “Atmospheric Drainage,” where he explored the benefits of windbreaks in controlling moisture, reducing flower loss, and attracting pollinators.

David Augustus Williston’s story begins on a family farm near Fayetteville, North Carolina, where each of thirteen children was given a garden plot. As his niece Dorothy Harris later recalled, Williston, the second oldest, planted vegetables but always made space for a patch of flowers. That early attention to order and beauty took root in his modest plot and continued to grow throughout his career.

Today, his contributions are recognized for their technical merit and the communities they serve. His work shaped campuses, civic projects, and professional pathways. His landscapes endure, as does his legacy of private practice and public service.

Educated at the Normal School of Howard University (1893–95) and then at Cornell University, Williston was among the first Black graduates of Cornell and the first Black student to graduate with a bachelor of science in agriculture. He studied under Liberty Hyde Bailey, chair of practical and experimental horticulture. Williston joined the famed Bailey’s Boys Club, a horticultural group led by the professor, whose members studied the leading plant scientists of the day. Williston’s senior thesis, “Atmospheric Drainage,” used field data from a peach orchard to evaluate the benefits of windbreaks. His research reflected a practical, scientific approach to horticulture and confirmed that windbreaks reduce

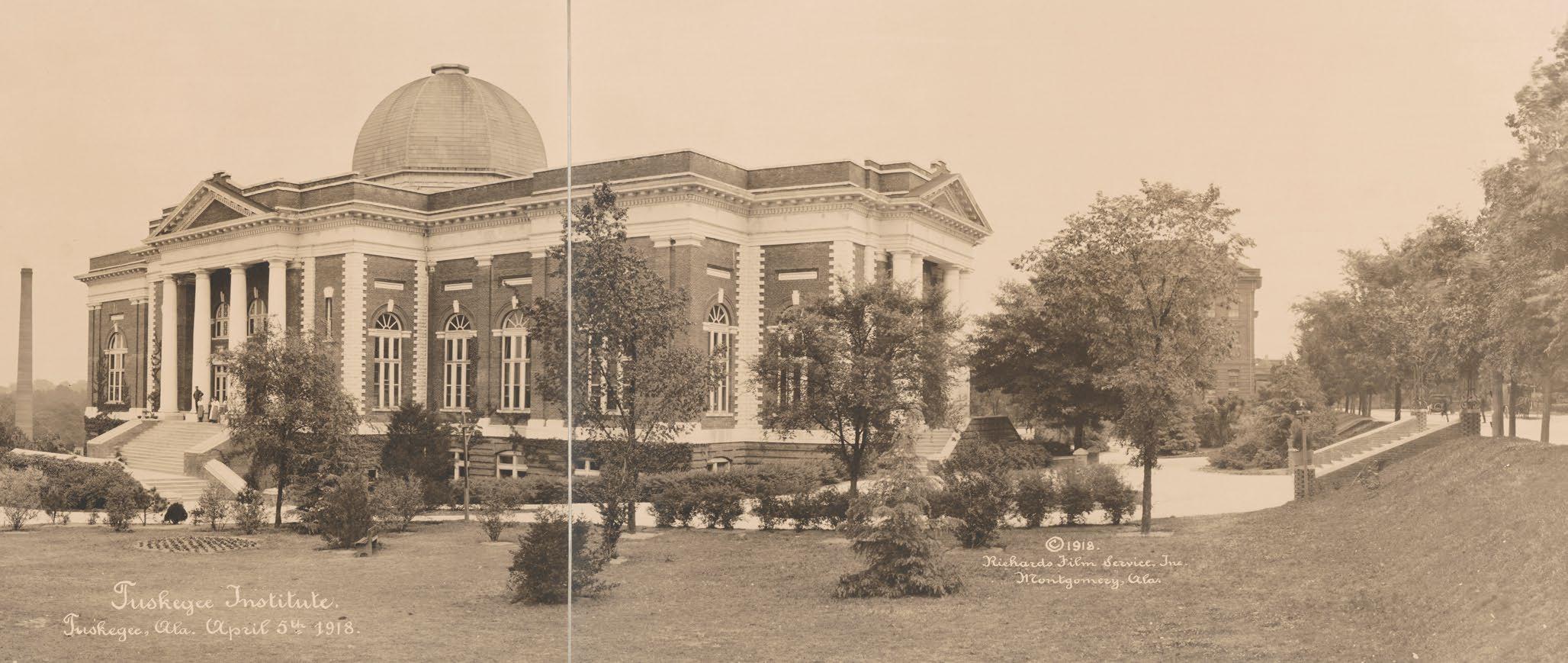

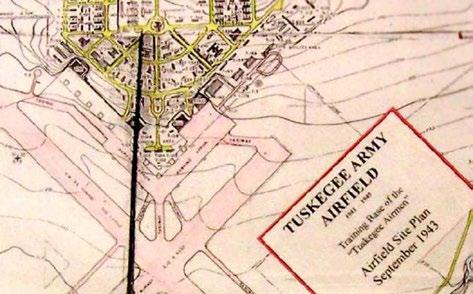

Below: Tuskegee Institute campus, April 5, 1918, when Williston served as superintendent of buildings and grounds

moisture loss and supported pollination. Williston later completed municipal engineering courses through the International Correspondence School in Pennsylvania.

According to historians Kirk Muckle and Dreck Wilson, writing in an article for Landscape Architecture Magazine, colleagues and students remember Williston as a learned man well-versed in Latin. He quoted from the classics, solved advanced mathematical problems with ease, and offered investment advice with the same confidence as horticultural wisdom.

Williston combined rigorous intellect with practical knowledge and a clear commitment to cultivating young minds.

Williston began teaching in 1898 at the State College of North Carolina at Greensboro. By 1902, he had joined the faculty at Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute as a professor of horticulture, where he would teach on and off for nearly three decades. In 1910, he became Tuskegee’s superintendent of buildings and grounds. There, he shaped the campus through formal site plans and extensive planting, often working with student

crews and struggling under limited funding. At Tuskegee, he formed close bonds with George Washington Carver and architect Robert R. Taylor. Together, they guided Tuskegee’s transformation into a national model for vocational and agricultural education.

Influenced by his time at Cornell and the teaching of Professor Bailey, Williston’s design approach reflected the English Landscape School. He selected plant materials with a painter’s eye and a scientist’s precision. He introduced native species alongside ornamentals, balancing aesthetic

vision with environmental adaptability. His landscapes shaped daily life at institutions nationwide, from Tuskegee to Alcorn State University, Fisk University, Clark University, and beyond.

The 1929 stock market crash brought widespread disruption to landscape and architectural design, stalling projects across the country and casting uncertainty over future commissions. However, Williston’s long-standing relationships with historically Black colleges and universities sustained his work during this volatile period. In the 1930s,

he moved to Washington, D.C., and established what is widely recognized as the first Black-owned landscape architecture firm in the United States.

His arrival in the capital coincided with a new era of federal investment. The New Deal, launched in response to the economic crisis, channeled resources into public infrastructure, housing, and educational facilities. This national focus on civic improvement created new opportunities for landscape architects, particularly those working in institutional and urban contexts.

Williston was well-positioned to participate. Washington had become a hub of Black professional life, and he joined a close-knit group of Black architects including Albert Cassell, John Lankford, Howard Mackey, and Hilyard Robert Robinson. Williston and Robinson had a long record of working together on numerous commissions, including the codesign of the site plans for the Langston Terrace Dwellings, the country’s first federally funded public housing development and a flagship example of New Deal priorities in action.

At Howard University, Williston worked on the 1932 campus plan alongside campus architect Albert Cassell. Historians Muckle and Wilson recount a moment of tension between the two. Williston reportedly objected to the placement of Founders Library, believing it blocked a long view of the city from the Yard. That debate aside, Williston shaped the landscape into a formal quadrangle, centering Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall, Rankin Chapel, and

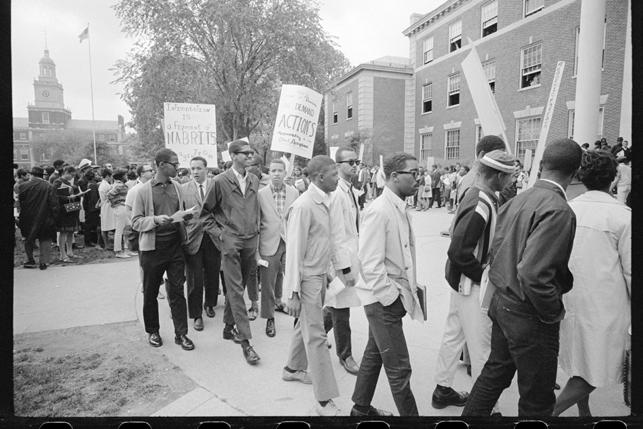

Founders Library within a rhythm of paths and greens. Originally laid out as a lattice of walkways crisscrossing between prominent building entries, the design evolved into the pattern we recognize today. Eight paths now radiate from a circular center point, creating a sense of connection and convergence. The Yard emerged as a public space for gathering, dialogue, and protest, and it remains so today.

To the west of Georgia Avenue, Williston envisioned parks and tree-lined greens that connected Howard to the surrounding neighborhood. He understood how campus design could radiate outward, shaping institutional character and public life. His work at Howard, like his projects at other HBCUs, affirmed the power of education, community, and collective vision.

In 1946, during Howard University’s Charter Day, President Mordecai Wyatt Johnson praised Williston’s pioneering path and national

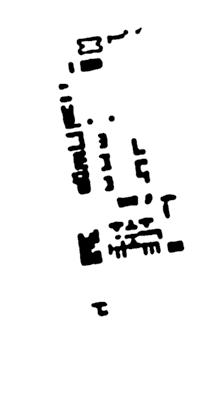

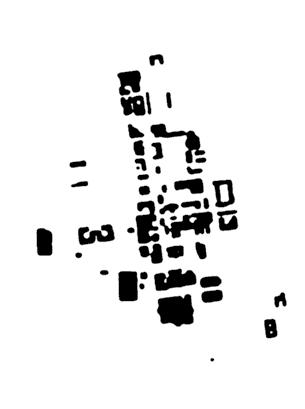

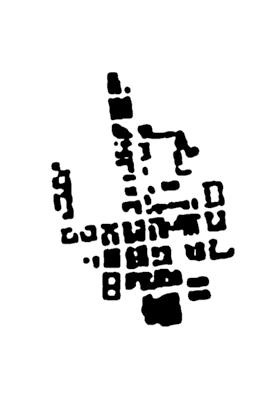

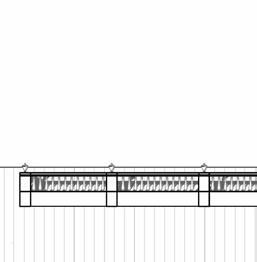

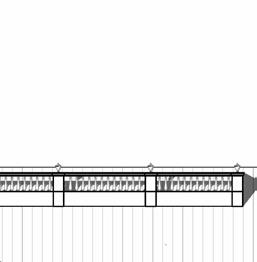

These Howard University figure-ground drawings trace the campus development from 1919 to a proposed 2030 future condition. The second image from left is of the 1932 campus plan vision, which introduced Douglass Hall as Building 14.

influence: “You have broken across all customary and well-trodden paths into a new field and have brought yourself, by repeated accomplishments, to be among the leading American landscape architects whose services are widely sought for private estates, college campuses, and landscape projects of state and federal governments.”

By the time of his death in 1962, Williston’s name was known within a close circle of students, colleagues, and institutions, but he has been too often overlooked in the broader history of landscape design.

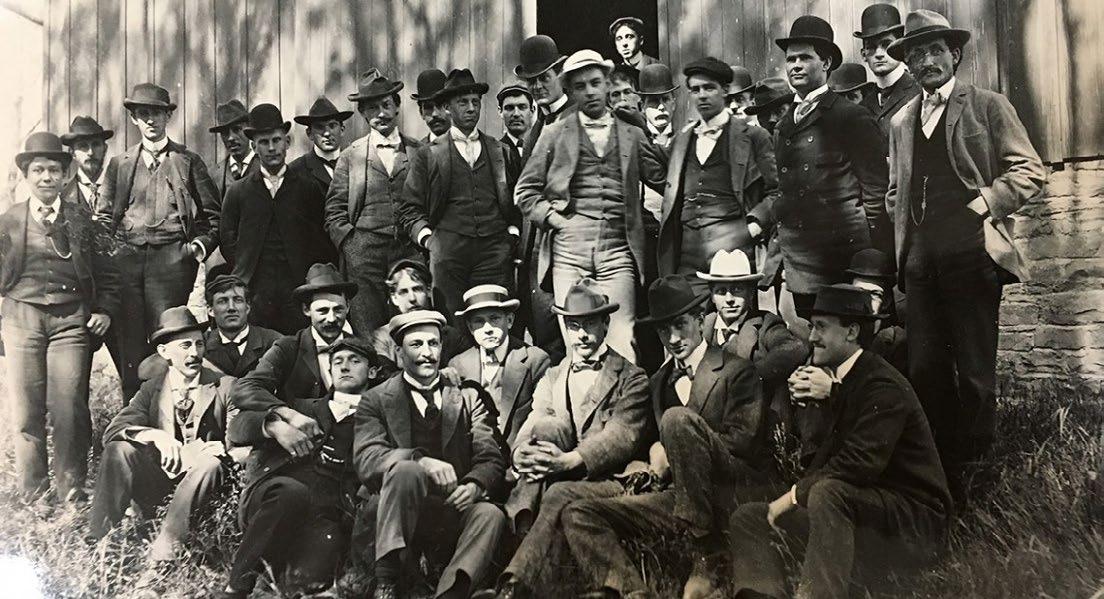

Right: Late 1890s group photo of the Horticultural Lazy Club, known as “Bailey’s Boys,” a circle of Cornell students mentored by horticulturist Liberty Hyde Bailey. Williston (fourth from left) was the first African American member, gaining access to vital mentorship and networks that shaped his pioneering career in landscape architecture.

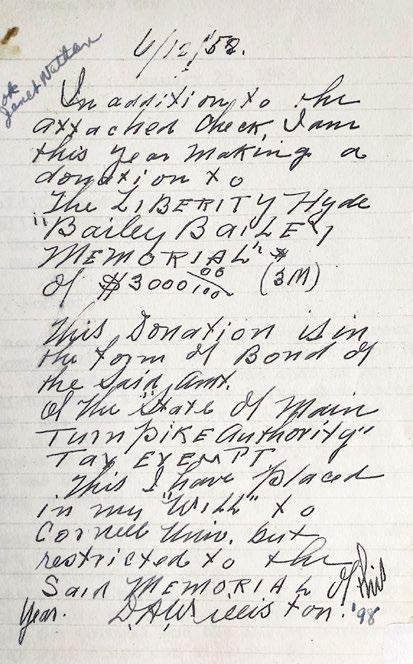

Below left: David Williston (top, left) alongside his brother Edward Davis Williston in portrait with other brothers and sisters. Below center: Williston’s 1958 handwritten donation to the Liberty Hyde Bailey memorial fund. Below right: Tuskegee Army Airfield site plan and photo, circa 1943; Williston’s attention to this project was instrumental to the success of the construction.

Left: Cornell University, Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity original crest, circa 1910s

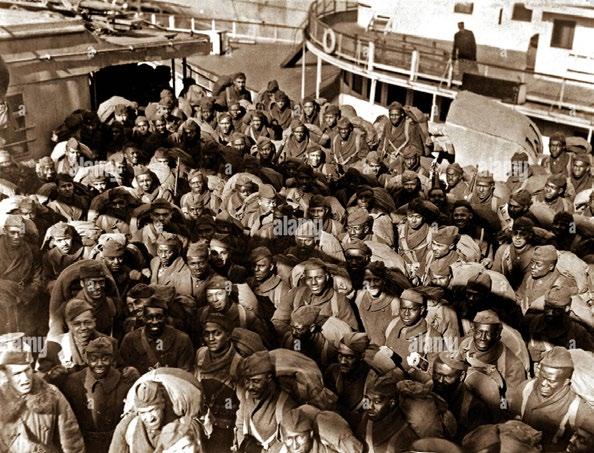

Right: Cassell’s 351st Field Artillery Regiment returning from World War I on the transport Louisville, February 17, 1919

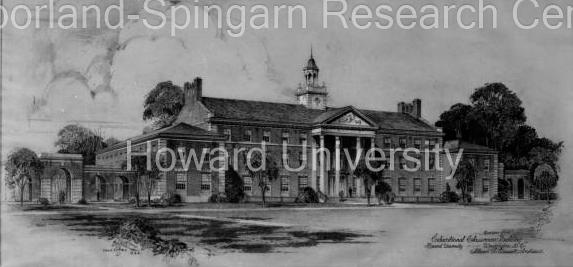

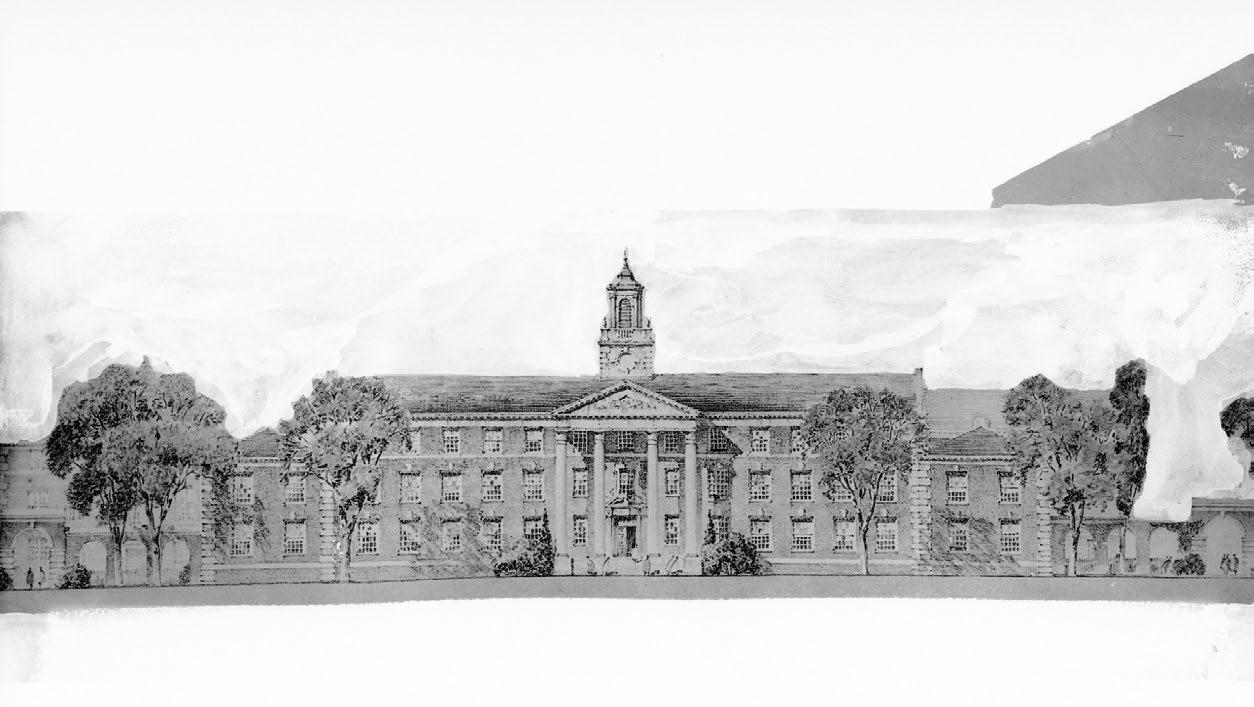

Below: Cassell’s graphite hand sketch of the proposed Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall, circa 1934

In the spring of 1913, a young man bends over a drafting table, working diligently with a graphite pencil. His instructor, one of the first African American engineering graduates from Cornell, watches closely, recognizing the force of intellect and vision taking shape before him. That young man was Albert Irvin Cassell, whose designs would reshape the landscape of Black higher education and infrastructure in the United States.

Albert Irvin Cassell (1895–1969) was born in Towson, Maryland, the third child of Albert Truman Cassell, a coal truck driver and trumpet player, and Charlotte “Lottie” Cassell, who washed laundry to help with household finances. At the age of 14, he entered a four-year program at Frederick Douglass High School, a segregated vocational school in Baltimore, where he studied carpentry and drafting. By the time of his graduation from the school in 1914, his talent had caught the attention of Ralph Victor Cook, the school’s head of technical education and a Cornelltrained engineer. Cook mentored Cassell and advocated for his admission to Cornell University’s architecture program in 1915.

At Cornell, Cassell entered an intellectual and cultural environment that expanded his sense of identity and artistic possibility. He joined Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., the first intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternity established for African American men. The fraternity’s rituals and iconography drew upon African and Egyptian symbolism, including representations of the Her-em-akhet, pharaohs, and pyramids, which reinforced ideals of heritage and leadership. Combined with the École des Beaux-Arts principles that shaped his architectural training, these influences helped inform the monumental character, symbolic richness, and classical order that came to define his later campus and civic designs.

Two years into his studies, Cassell was drafted into World War I and served in France with the 351st Field Artillery Regiment, 92nd Division. Cornell conferred his degree in 1919 as a “war diploma,” recognizing the interruption.

Cassell’s 1919 collaboration with William A. Hazel, an architect and educator, on five trade buildings at Tuskegee coincided with Hazel’s appointment as the first dean of Howard

University’s School of Architecture. Early in 1920, Cassell worked in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, as chief draftsman for Howard J. Wiegner, designing silk mills and other industrial facilities. Soon, Hazel persuaded Cassell to join him in Howard’s new program.

By 1922, Cassell was appointed university architect and head of the Department of Architecture. He led the program through 1928, shaping what would evolve into the College of Engineering and Architecture. His tenure coincided with President Mordecai Johnson’s broader vision for Howard, in which architecture was conceived as a deliberate instrument of institutional identity and national positioning.

President Johnson recognized the university’s architecture needed to convey legitimacy, permanence, and cultural authority within the symbolic landscape of the nation’s capital. The campus could not simply provide functional space; it should actively project heritage, power, and leadership, affirming Howard’s standing as the preeminent African American institution at the center of national life.

Cassell designed a series of landmark buildings that established the campus as a national symbol of Black intellectual achievement.

In appointing Cassell as the first university architect, Johnson strategically aligned Howard’s facilities with this vision. Cassell’s École des Beaux-Arts training provided him with a classical architectural vocabulary, rooted in Roman and Greek precedents, that Washington, D.C., aristocrats and decisionmakers would understand and respect. This vocabulary also allowed Howard’s campus to embody a formal organizational order that echoed the city’s monumental planning traditions. For Johnson, Cassell’s appointment was less about stylistic preference and more about harnessing architecture as a symbolic language to assert Howard’s legitimacy in the nation’s civic and cultural milieu.

Cassell’s preparation for this role and his partnership with Williston also were informed by his early professional experience at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (today’s Tuskegee University). Tuskegee’s architectural tradition was markedly different. Guided by Booker T. Washington and architect Robert R. Taylor, Tuskegee emphasized a practical design-build pedagogy in which students participated in design and

construction and used locally available materials. This interdisciplinary method, rooted in self-reliance and collective craftsmanship, embodied Tuskegee’s educational philosophy of cultivating the “head, hand, and heart.”

Tuskegee and Howard emerged from the same era of aspiration yet charted distinct paths, each shaping an architectural language that mirrored its educational philosophy. At Tuskegee, Booker T. Washington championed an ethic of practical learning and communal effort, where students literally built the campus that would, in turn, build them. The brickwork, forged by their own hands, became a quiet archive of self-reliance, craftsmanship, and the belief that labor and learning were inseparable. Its architecture grew from the soil outward it was rooted, tactile, and deeply connected to the rhythms of making.

Howard’s campus followed a different, but no less purposeful, trajectory. Influenced by Frederick Douglass’s insistence on broad intellectual pursuit and the urgent necessity of full participation in the national civic sphere, Howard sought an architectural presence that

reflected scholarly ambition and institutional legitimacy. Under Johnson’s leadership and through Cassell’s design vision, the buildings conveyed confidence, cultural authority, and the promise of professional advancement. This was a landscape shaped to signal belonging in the corridors of national discourse.

Seen together, these architectural traditions do not compete but converse. Tuskegee’s hands-on, community-built environment and Howard’s expression of academic stature reveal two complementary modes of empowerment. One was specifically grounded in the transformative nature of craft, and the other is a springboard for pursuit of intellectual leadership. Each campus embodies a philosophy that advanced African American education in its own way, using architecture as a pedagogical tool and a declaration of purpose.

Giving tangible form to this vision, Cassell designed a series of landmark buildings that established the campus as a national symbol of Black intellectual achievement: Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall (1935), the Chemistry

Building (1936), Founders Library (1937), and the Civil Engineering Building (1939). Together, these works form the core of the Howard University Campus Historic District, now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. During this time, Cassell also designed dormitories, hospitals, an athletic stadium, and utility infrastructure with the same level of architectural intention.

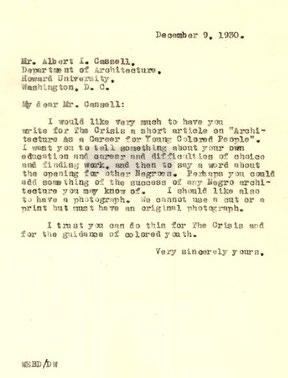

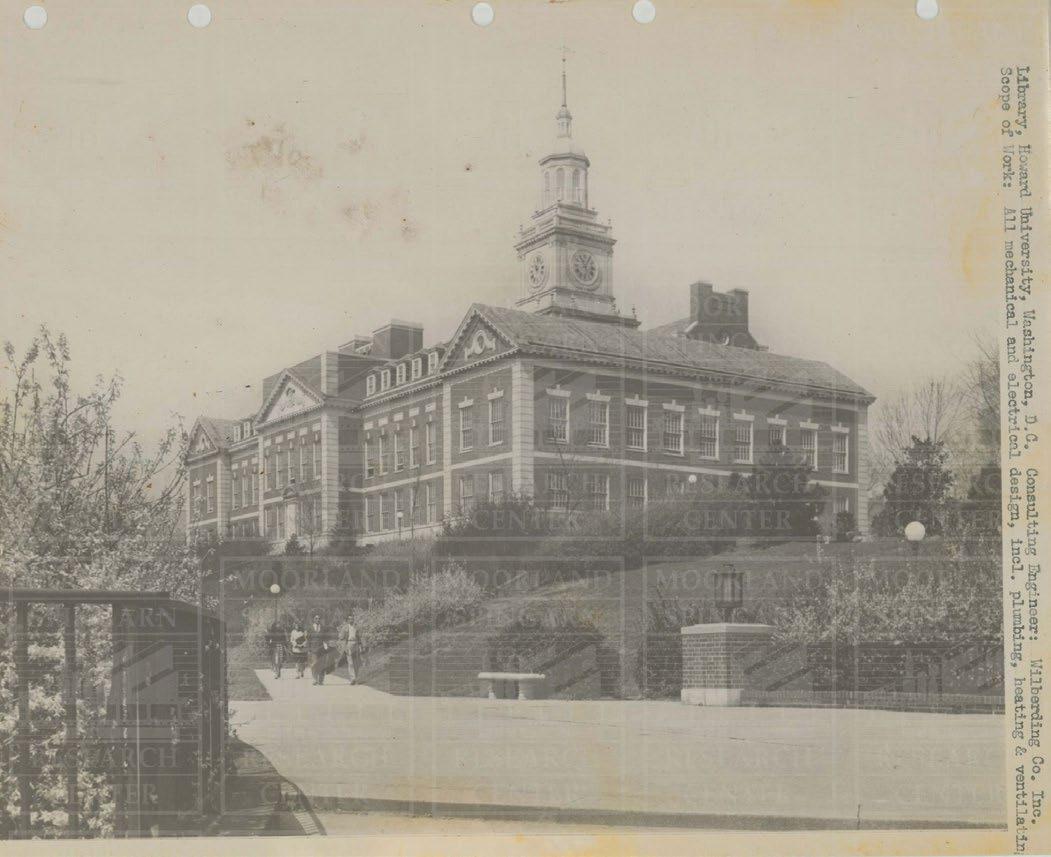

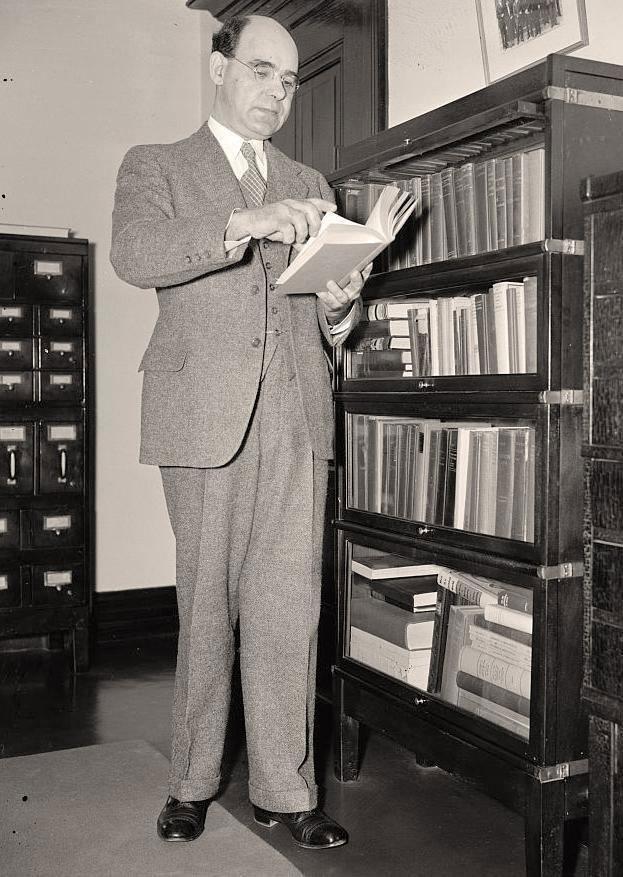

Cassell’s leadership at Howard extended beyond design. He helped secure major philanthropic grants, managed land acquisitions, and conducted detailed property surveys that shaped the university’s expansion. He laid the critical educational groundwork for the College of Architecture and oversaw technical and construction teams responsible for nearly every campus improvement between 1922 and 1938. In 1930, W. E. B. Du Bois, a co-founder of the NAACP and editor of The Crisis, its official magazine, invited Cassell to write about architecture as a profession for young African Americans. The request reflected Cassell’s recognition across Black academic and professional circles and his standing as a model for future generations.

Cassell’s service at Howard ended under strained circumstances with President Mordecai Johnson in 1938. The dismissal was controversial and appears to have stemmed from disagreements over his outside professional work, differences in vision for campus development, and conflicts with the administration. Some accounts suggest the university administration was uncomfortable with Cassell’s growing prominence and independent professional activities.

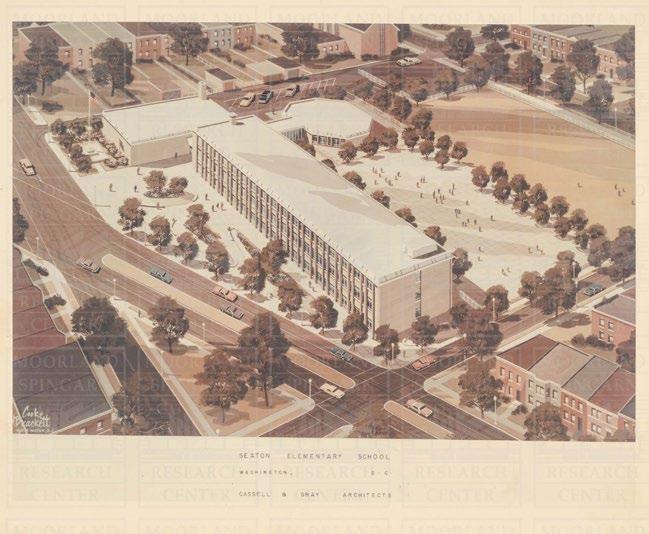

Nevertheless, Cassell continued practicing architecture independently and later through the firm of Cassell, Gray & Sutton. He completed major commissions for other historically Black colleges and universities,

including Morgan State University, Virginia Union University, and what is now the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, where his architecture continues to reinforce a sense of institutional pride. The breadth of his practice also extended to Masonic temples, churches, institutional buildings, and select private residences throughout Washington, D.C., and Baltimore.

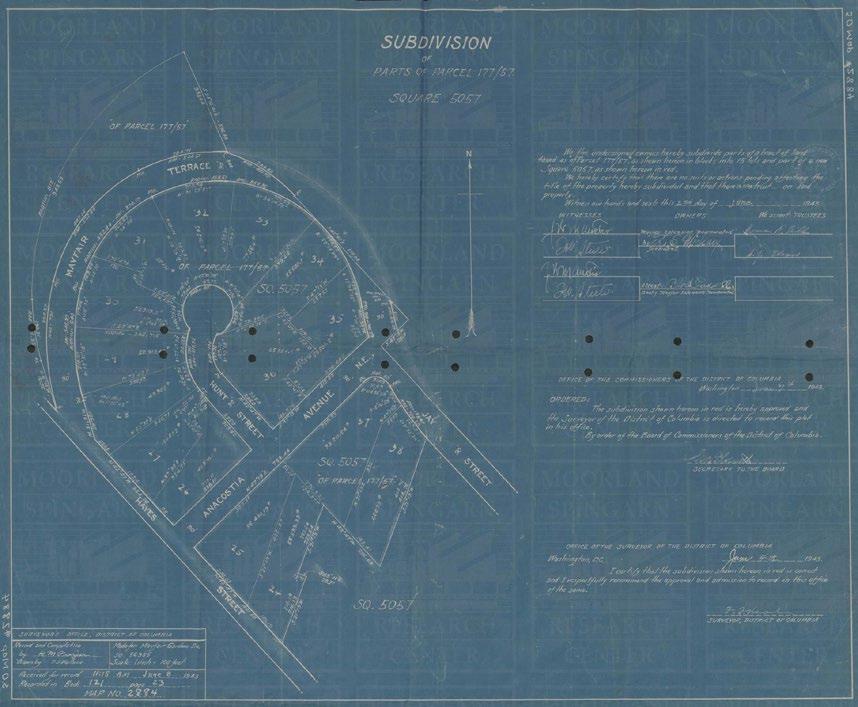

Among his most significant post-Howard contributions were residential developments. He designed public and private housing for middle-income African Americans. These projects included the James Creek Dwellings (1943) and the Mayfair Mansions Apartments, completed in 1946. The latter development

Opposite: Albert Cassell’s office with shelves filled with books and folios. Cassell’s architectural papers are housed at Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center. Inset: Letter from W.E.B. Du Bois to Cassell, December 9, 1930, where Du Bois asks Cassell to write an article on “Architecture As a Career for Young Colored People” to be published in The Crisis.

became one of the first privately financed, FHA-insured apartment communities for Black residents nationwide. Its 594 garden-style units were designed with dignity and affordability in mind. Mayfair won an architecture award from the Committee on Municipal Art of the Washington Board of Trade for its civic contribution.

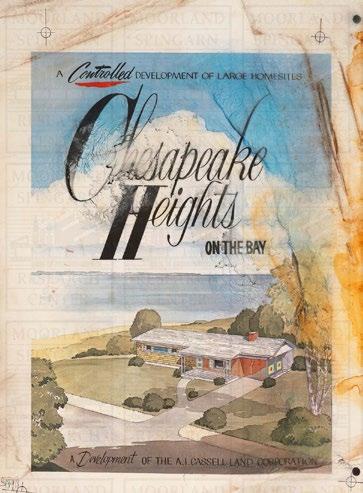

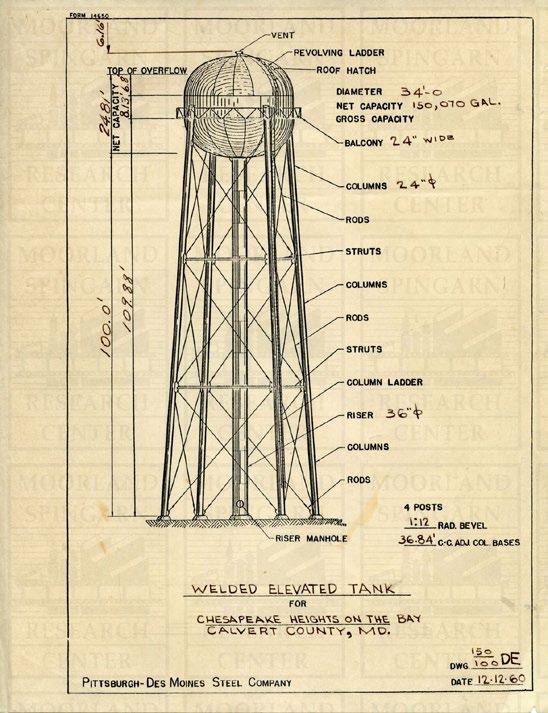

From early in his career, Cassell’s vision extended beyond buildings to entire communities. In the 1930s, at the height of the Great Depression, he purchased 380 acres on the Chesapeake Bay near Prince Frederick, Maryland, where he planned an ambitious, self-sustaining settlement called Calvert Town. Designed for African Americans, the town was rooted in the ideals of economic self-reliance, cooperative development, and racial equity. Cassell envisioned farmland, factories, a hotel, hospital, theater, boardwalk, and modern infrastructure, including electrification and sewage treatment. He applied for Public Works Administration support and met with President Roosevelt to advocate for funding, but the project failed to secure federal backing. For all the strength of

Cassell’s vision, the period’s economic constraints proved decisive. Even with private investment and charitable appeals, the town was never realized.

In the 1960s, he returned to Calvert County with a new plan. Chesapeake Heights on the Bay was to be a summer resort community for African American families. It would include homes, a marina, commercial amenities, and recreational access to the Chesapeake. Though some lots were sold, the project stalled after Cassell’s death in 1969. Today, a single street, North Cassell Boulevard, is all that remains of his decades-long effort to build a community where design could be a force for equality.

At the height of the Cold War, Cassell designed a large-scale residential leasepurchase project in northwest Washington, including a proposed underground bomb shelter. The development was ultimately shelved as diplomatic relations between the US and the Soviet Union began to ease. Undeterred, Cassell and his firm continued to shape the capital’s built environment through

a wide range of commissions, from schools and residences to Pentagon renovations and computing facilities. Cassell also worked with major institutions, including the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington and the District government.

Architecture was personal and generational for Cassell. He had six children and two stepchildren from three marriages. Four of the children studied architecture at his alma mater: Charles Cassell (’46), Martha Cassell (’47), Alberta Jeannette Cassell (’48), and Paula Cassell (’76). Together, the Cassells left an enduring mark on architecture and civic life.

After suffering a heart attack, Albert Irvin Cassell died at his home in Washington, D.C., on November 30, 1969. His funeral was held at Washington National Cathedral on December 3, followed by burial at Baltimore National Cemetery, where he received military honors. He left behind a built legacy that shaped the educational and civic infrastructure of Black America. His work endures. So does his vision of the campuses he transformed and the architects he inspired.

25

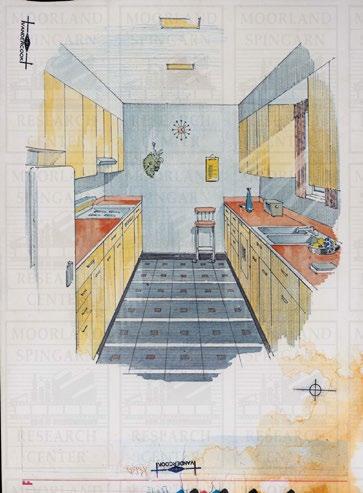

A selection of Albert Cassell’s architectural drawings, renderings, photographs, and site plans, reflecting his classical training, precision, and longrange planning for university, residential, and civic institutions.

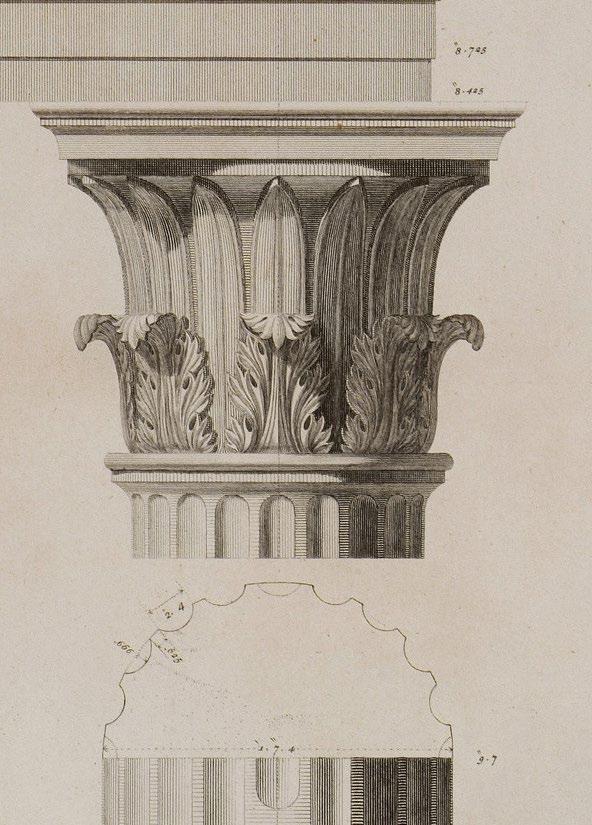

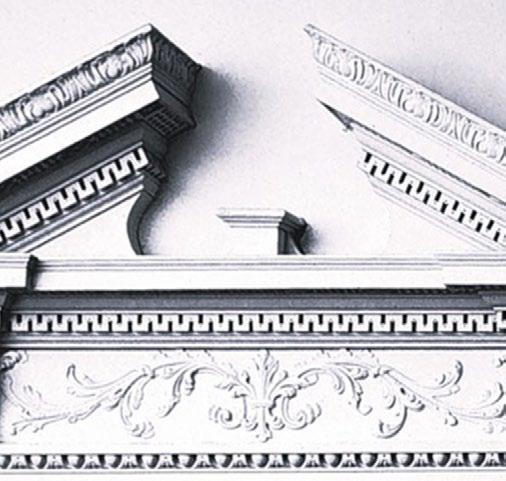

As Cassell is designing Douglass Hall, the building details are where his intent becomes tactile, intimate, and precise. These details are where concept meets craft, and the materials, forms, and symbols articulate the message. The following visual study assists in decoding how the building’s architecture communicates its purpose and place in the campus fabric.

Douglass Hall portico columns

Opposite: Corinthian capital and Tower of the Winds drawings from Stuart and Revett’s The Antiquities of Athens (1762) and Andronicus’ De Architectura (25 BCE), original editions of which are held in Cornell’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. Both of these would have been readily available during Cassell’s architectural studies.

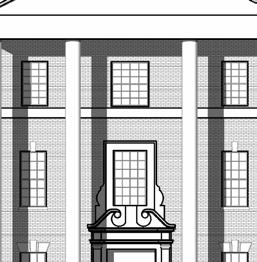

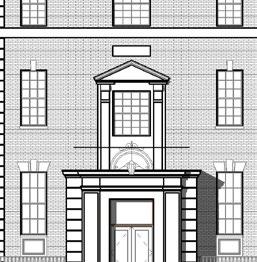

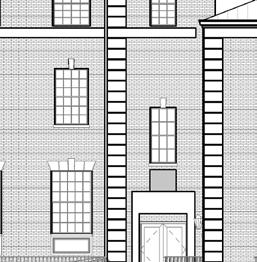

The portico of Douglass Hall stands as an enduring symbol of strength and legacy. Stoically oriented east toward the Yard, Douglass Hall’s pediment, entablature, and columns have provided a meaningful architectural backdrop for significant events since the building’s dedication. The selection of the column order reflects Albert Cassell’s intentional engagement with classical precedent, informed by his education at Cornell University and his desire to embed the Western and North African intellectual traditions of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian heritage within the building’s form.

Cassell drew specifically from the Tower of the Winds ( Ωρολόγιο

), constructed c. 100 BCE in the Roman Agora of Athens. Designed by Andronicus of Cyrrhus, the tower integrated meteorological and horological functions, employing sundials, water clocks, and wind vanes, to embody the pursuit of empirical knowledge.

Cassell’s particular variation of the Corinthian order carries dual heritage references: the lower acanthus leaves reflect Western classical tradition, while the upper lotus-like “water leaves” evoke ancient Egyptian capitals. The lotus, which flourished in the fertile mud along the banks of the Nile, was a powerful symbol of cosmic creation and rebirth in ancient Egyptian design and mythology due to the way it closes at night and reopens each morning. Egyptian plant motifs like the lotus and papyrus predate and likely inspired later Greek and Western design traditions.

The fusion of lotus and acanthus motifs within Douglass Hall’s capitals provides a glimpse into Cassell’s intent to foreground African lineage within Howard’s architecture. By privileging Egyptian over Greco-Roman symbolism, he aligned the university with a broader intellectual movement among African American artists and activists. From the Harlem Renaissance to the Black Arts movement, Egypt was invoked as proof of Africa’s civilizational authority and as a counter to narratives that denied African contributions to the foundations of culture and learning.

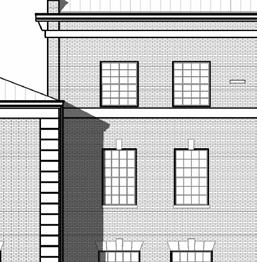

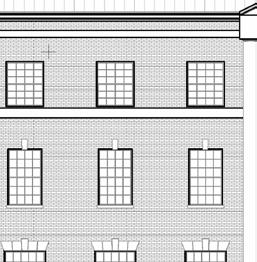

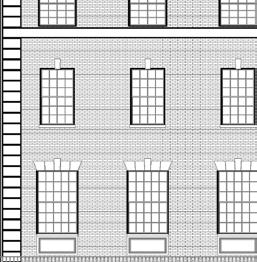

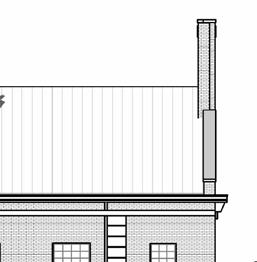

Cassell’s window design for Douglass Hall reflects a thoughtful blend of classical proportion and modern function. In the 1920s, educators and architects were beginning to prioritize natural light and ventilation in schools, shaped by European modernist ideas and the industrial evolution of American building materials. Cassell’s window design integrated large windows into the façade, allowing for ample daylight to flood the interior. Campus lore asserts that he was pressured to employ smaller, more proportionally specific windows, which no doubt would have been more economical in this frugal era of construction. Yet, Cassell held steadfast.

By incorporating these large windows, Cassell was able to marry the symbolic dignity of classical architecture with the modern needs of educational spaces. The decision to integrate significant natural light into the building was a reflection of the period’s progressive health consciousness and a practical solution to enhance the learning environment.

Cassell’s experience designing silk mills in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, likely influenced this

decision. In 1920, as chief draftsman for architect Howard J. Wiegner, he worked on projects like Laros and Lehigh Valley Silk Mills. These facilities featured wide-open floor plans supported by steel and timber trusses, along with generous window-to-wall ratios that maximized daylight for workers.

Echoes of that design logic surfaced during the renovation of Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall in 2020. Behind layers of alteration, the building’s open, light-filled wings revealed their industrial DNA. Both the north wing, home to the historic auditorium and library, and the south wing’s open commons used similar structural strategies. On the first floor, 15-over15 double-hung windows line the façade. The second and third floors feature 8-over-8 units, nearly identical to those used in the silk mills, and subsequently in Cassell’s buildings at Morgan State University. Originally constructed with individual panes of glass, these windows were removed and replaced in the late 20th century with insulated, singlepane double-hung units. While the historic muntin patterns remain, the material clarity and depth of the originals have been lost.

Morgan State University Memorial Chapel, Baltimore, Maryland, circa 1941

Laros and Lehigh Valley Silk Mill, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, c. 1919. Cassell’s experience designing mills likely influenced his use of generous window-to-wall ratios that maximized daylight and married the dignity of classical architecture with the modern needs of educational spaces.

Integrated within the dentil band is the “meandros” pattern or “meander,” a Greek key motif symbolizing infinity, unity, and the cycle or journey of life.

The detailing within Douglass Hall is typically simple and illustrative of an economy of means and restraint of décor. As such, the areas where Cassell introduces more ornate details stand out. The finely crafted fretwork dentiling found in the millwork of the library lies at the intersection of Cassell’s classical architectural training and his foundational experience in skilled craftsmanship.

The use of dentils (an essential element of classical entablature) reflects Cassell’s BeauxArts education at Cornell University. The execution of these details in intricate woodwork signals a more tactile and material sensitivity, likely rooted in Cassell’s early vocational training in carpentry at Frederick Douglass High School in Baltimore. This dual background enabled Cassell to engage classical forms not only as abstract design principles but as expressive, embodied gestures grounded in the craftsmanship of making.

These details resonate as a foundational symbol of American democracy. Rendered in the language of neoclassicism, the choice aligns powerfully with Cassell’s broader project: to articulate African American institutional identity through architecture grounded in intellectual heritage, permanence, and the ideals of the Enlightenment. Design Details

Integrated within the dentil band is the “meandros” pattern or “meander,” a Greek key motif with countless historical variations. A decorative border built from a continuous line turning 90 degrees at regular intervals, it is an ancient symbol of infinity, unity, and the cycle or journey of life. Framing the thresholds to the library and reading room, this dentil’s specific articulation can be traced to the porticos of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Given Cassell’s time working in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, it is possible he traveled to Philadelphia, sketching and studying its architecture. One wonders if in choosing that motif he sought to echo a symbolic journey, linking personal and communal progress to the ideals of national independence and democratic expression.

Design Details

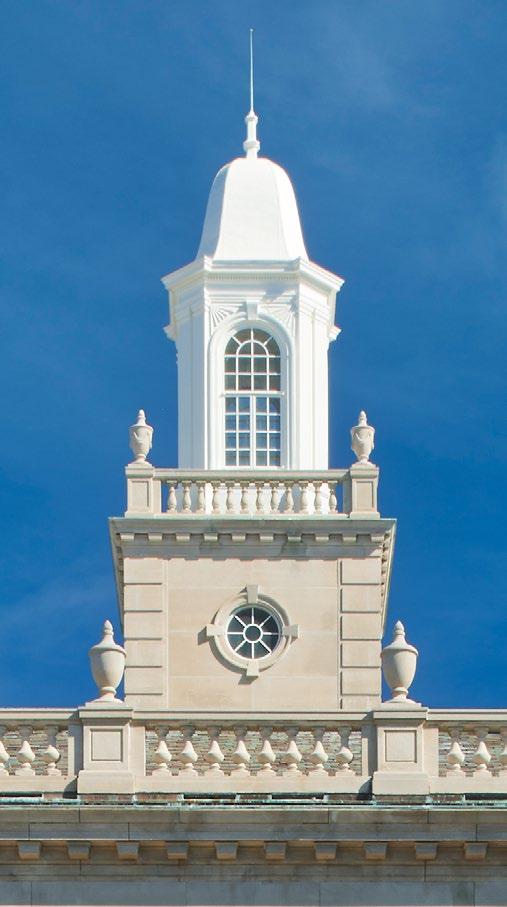

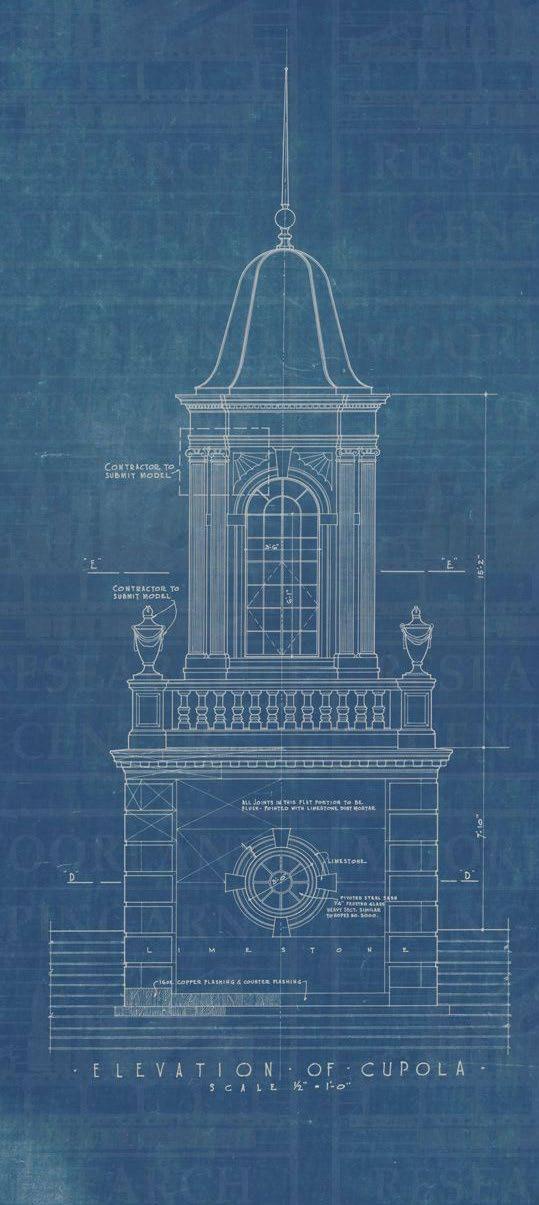

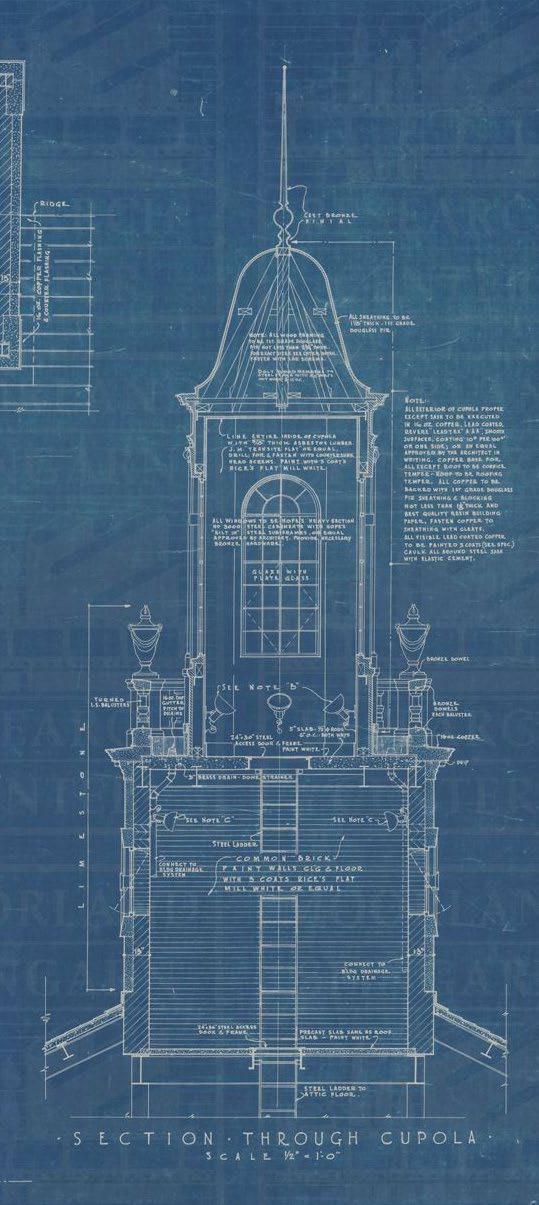

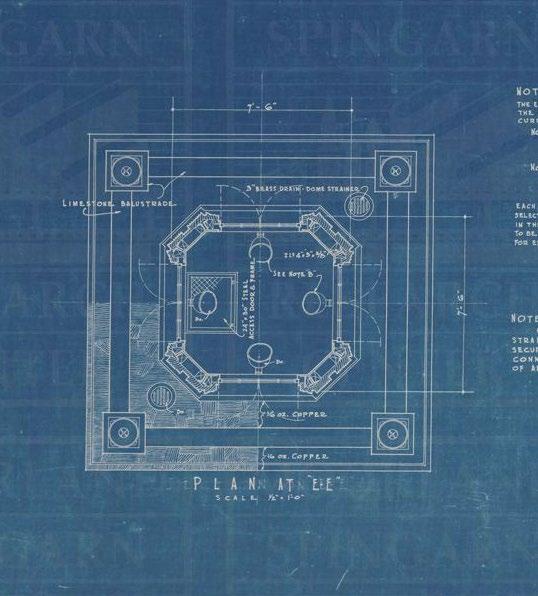

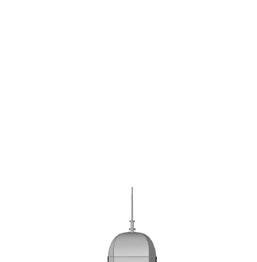

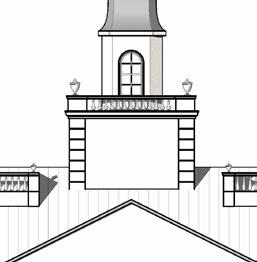

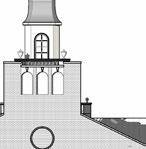

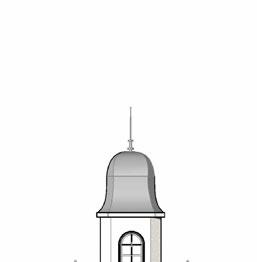

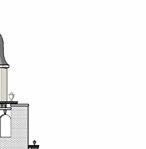

The cupola rises above the center of Douglass Hall and is unique in its assembly as an originally designed roof lantern for Howard University. Built before the cupola on Founders Library, it reflects Cassell’s exploration of how form and light can express purpose and presence. By day, it crowns the roofline with visual clarity. By night, it becomes a beacon, guiding students toward the heart of the Yard.

The cupola’s design follows a tripartite composition. A squared limestone base anchors it to the pitched roof. Above that, a glazed lantern made of lead-coated copper rises as the central element. At the top, a painted curved roof sheathed in lead-coated copper supports a cast bronze finial that completes the silhouette.

Material and meaning are fully intertwined in this structure. The lantern’s structure is notched, framed, and sheathed in Douglas fir—spelled “Douglass Fir” in Cassell’s original architectural drawings, likely as an intentional nod. This timber, highly valued in the 1920s for its strength and resilience, was probably sourced from the Pacific Northwest. Its

Opposite: Cupola atop Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall as illustrated within the 1933 blueprints

presence connects distant geographies, uniting coastlines through a structure that speaks to ideals of equity and belonging.

At its base, limestone blocks form a strong foundation, detailed with quoined corners that emphasize edges and reinforce a sense of permanence. Above, a limestone balustrade with hand-turned balusters supports carved urns. These ceremonial elements were originally designed with swags and finials, tying the lantern to classical design traditions. Within neoclassical architecture, urns symbolize remembrance, respect, restraint, and reason.

Double pilaster fluted Ionic order columns support the perimeter entablature for the rooftop. Given Cassell’s knowledge and reverence for architectural legibility, these columns suggest strength paired with refinement. The scroll-like volutes at their capitals recall ancient symbols of knowledge, pointing to a design rooted in intellect and intention. In the Hellenistic period, the Ionic order was often reserved for buildings associated with the gods of wisdom and the arts.

1–2. Howard University’s original 19th-century seal bore the motto “Equal Rights & Knowledge for All,” depicting Black and Native American figures surrounding the globe beneath a radiating sun. This imagery of inclusivity and enlightenment guided the university for four decades. As the institution grew, its emblem was reimagined. In the early 20th century, the modern seal was adopted, encapsulated in the pediment tympanum of Douglass Hall: the motto Veritas et Utilitas encircles a shield displaying an open book inscribed deo et reipublicae (“by God and the republic it is permitted”). These ideals are expressed in the architectural details of the building, where the open book motif framed by Corinthian acanthus leaves reinforces the enduring values of knowledge, purpose, and civic duty.

3. The base of the cupola and the ceremonial entry gates are crowned with limestone urns, symbolizing the building as a memorial.

4–5. Mahogany, prized for its deep, rich color and the high cost of harvesting and shipping it in the 1930s, was selected for the Frederick Douglass Reading Room, the building’s most scholarly and celebrated space.

6. Public corridors are finished with checkered-pattern terrazzo flooring, which supports the building’s warm atmosphere while offering exceptional durability and resilience. These original floors were preserved and restored with only light buffing and mopping.

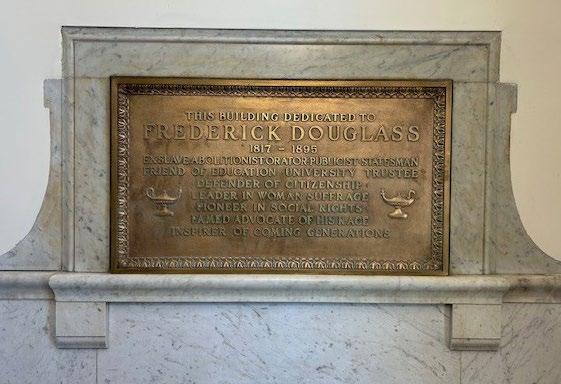

7. At the building’s entry, white Carrara marble quarried in the Apuan Alps frames the bronze Frederick Douglass dedication plaque. The plaque reads: “This Building Dedicated to Frederick Douglass, 1817–1895: Enslaved Abolitionist; Publicist; Statesman; Friend of Education; University Trustee; Defender of Citizenship; Leader of Woman Suffrage; Pioneer in Social Rights; Famed Advocate of His Race; Inspirer of Coming Generations.”

8. Black and white marble with intense gold and white veining surrounds the fireplace in the Frederick Douglass Reading Room. It appears to be Nero Portoro, a dramatic variety quarried in Porto Venere, a region also known as the Gulf of Poets, and this harkens to the black marble mantle in Douglass’s own study in his home at Cedar Hill.

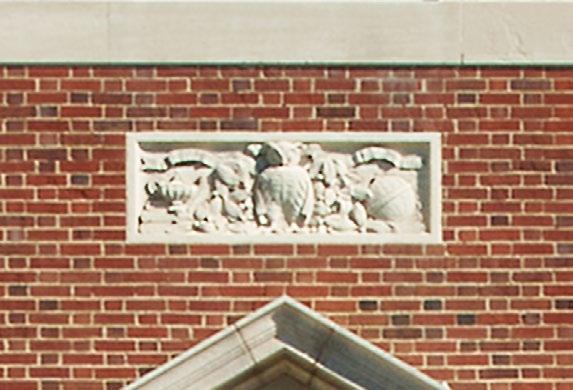

9. The bas-relief limestone panel above the entrance reflects Albert Cassell’s grounding in classical symbolism. At its center, an owl, long associated with Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, embodies the pursuit of knowledge. A lantern suggests hope, guidance, and the triumph of light over darkness, while a globe conveys wholeness and a global reach.

(Following spread)

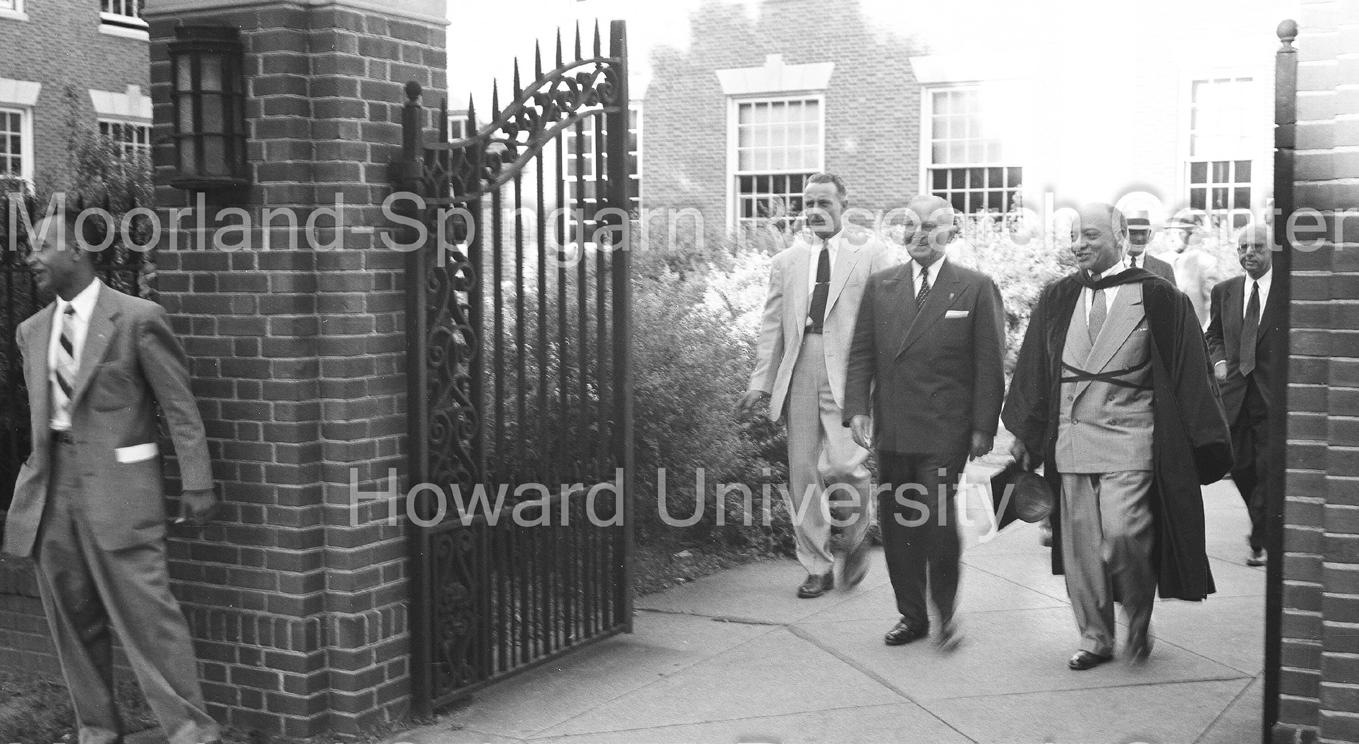

10. Cassell’s design for Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall’s wrought iron entry gate features symmetrical scrollwork volutes with pointed finials, drawing on African and European influences. While architectural styles of the 1930s were influenced by the Art Deco and Art Nouveau movements, wrought iron gates typically maintained a more classical style. Typical of gates and balconies of the era in Southern cities like Charleston, Savannah, and New Orleans, wrought iron was often fabricated by skilled Black artisans, many of whom were freed slaves or their descendants. Ironwork was a symbol of resilience and craftsmanship within the Black community and a source of cultural pride despite social and economic challenges.

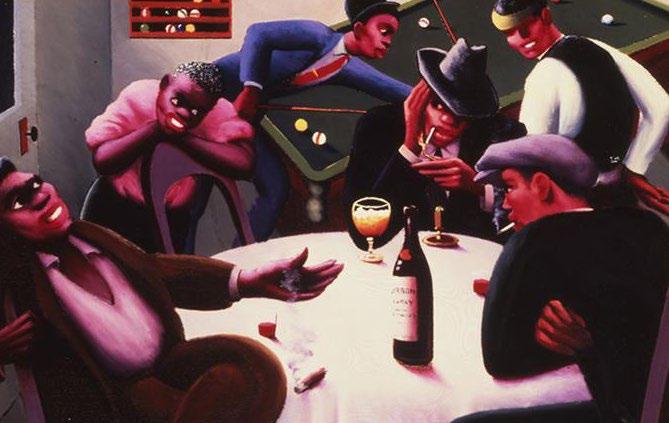

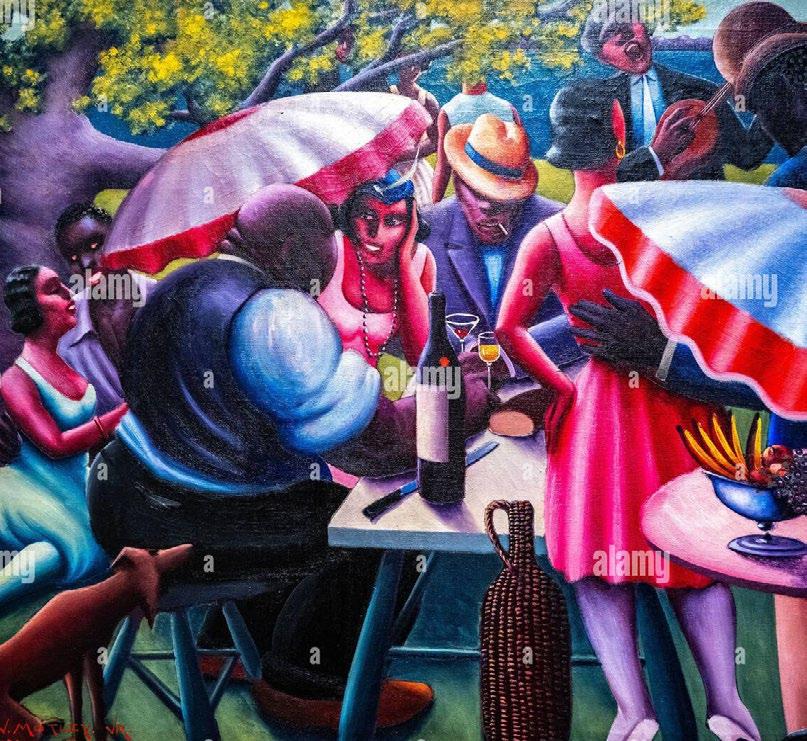

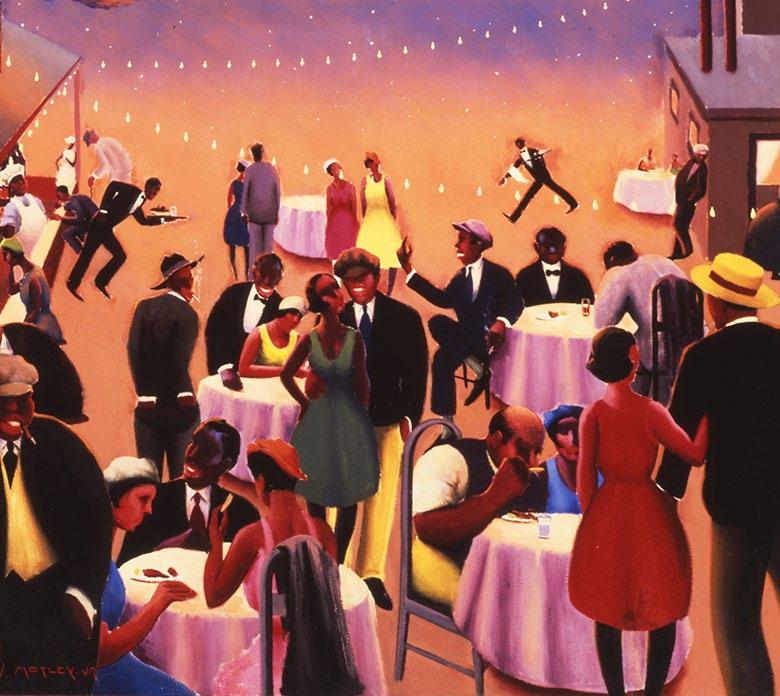

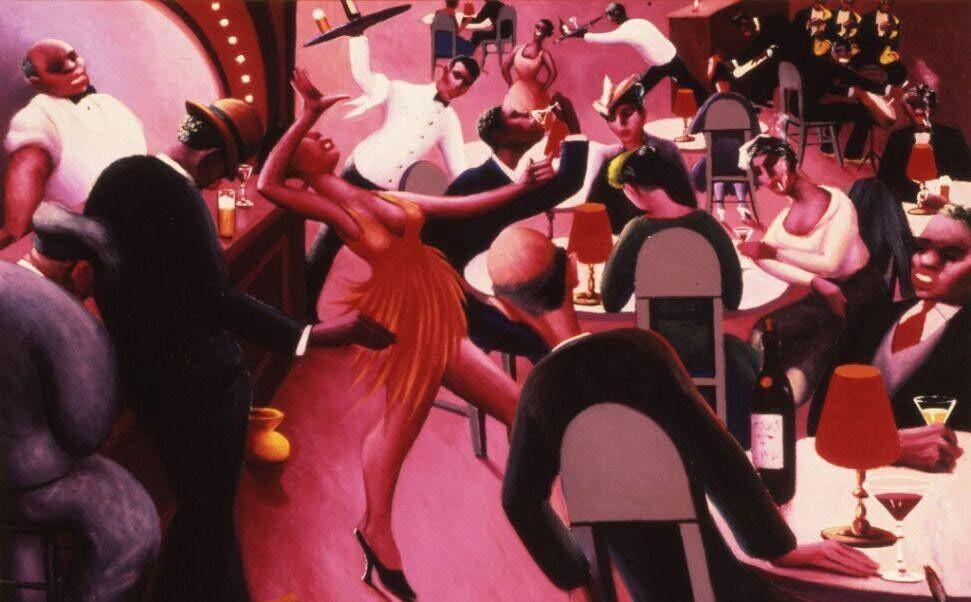

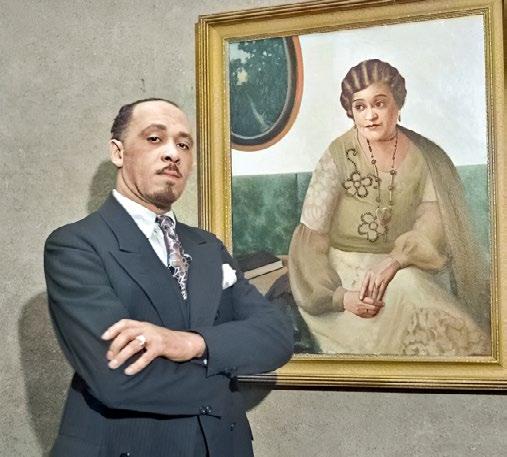

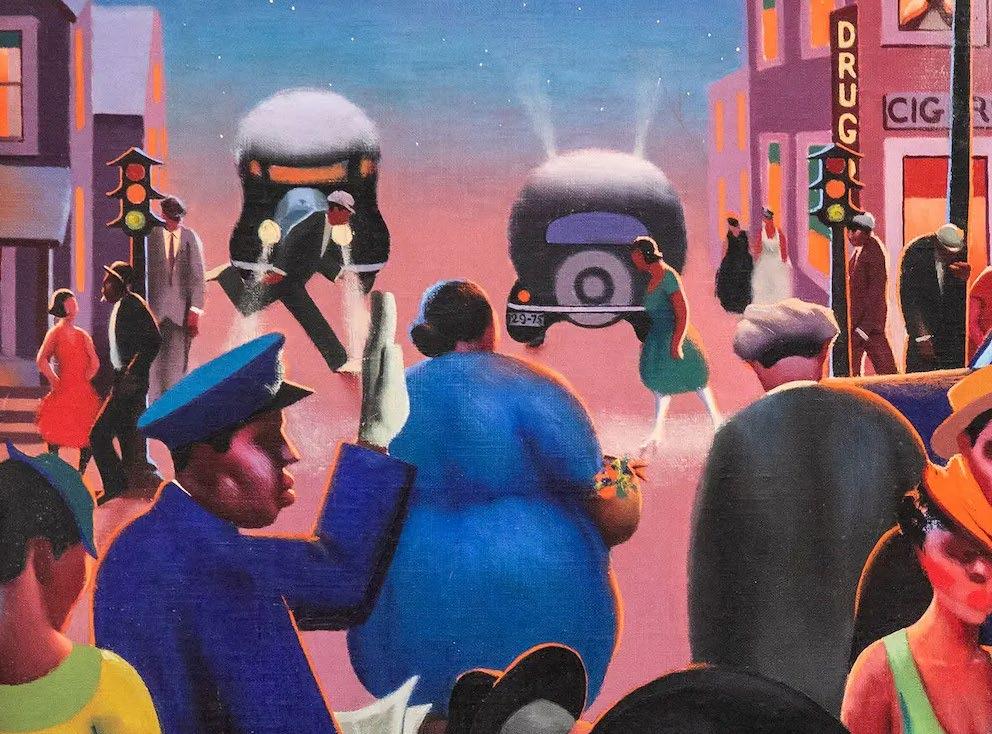

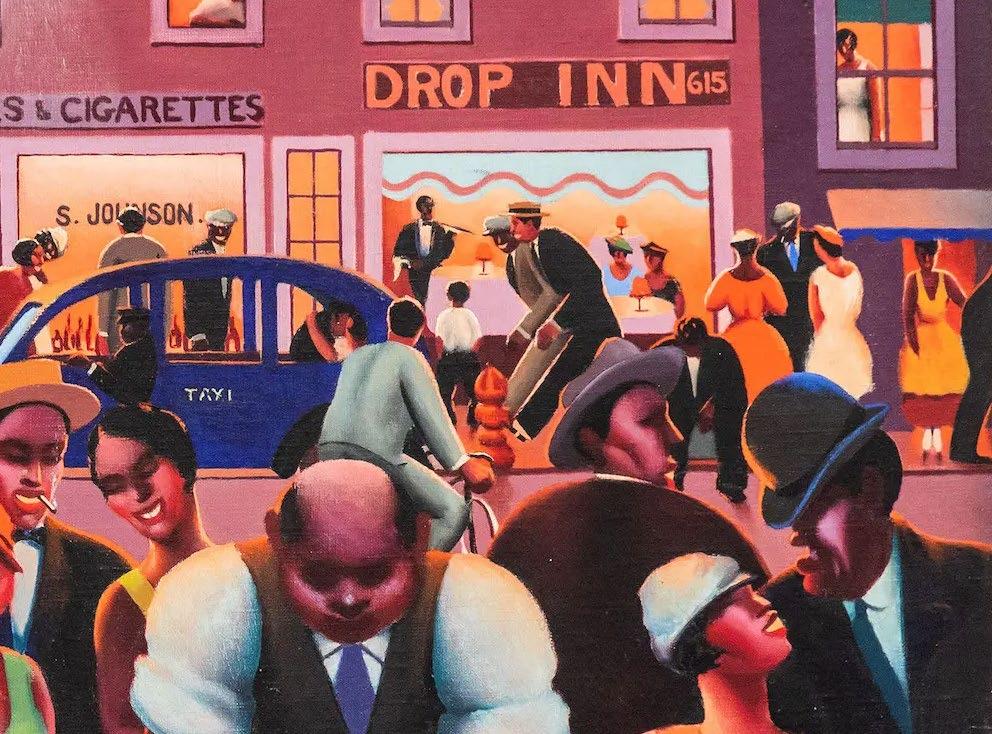

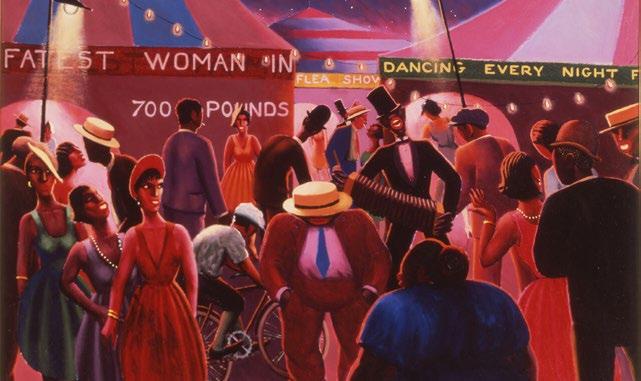

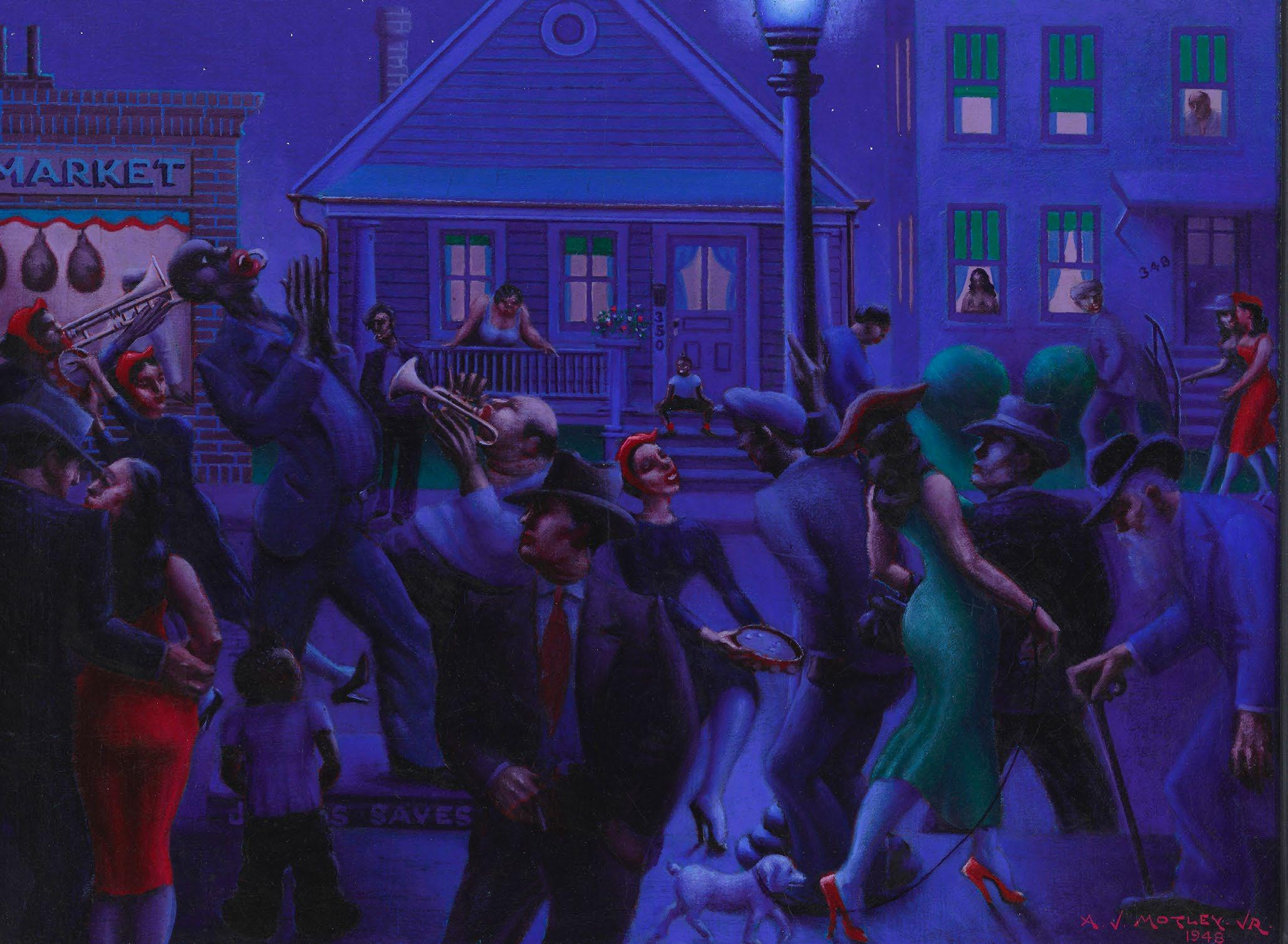

In 1935, Archibald J. Motley Jr., a defining figure in American modernism and the Harlem Renaissance, brought his vision to Howard University when he accepted a commission to create a mural for the entrance lobby of Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall. The work has vanished, its surface buried under layers of later paint, yet the story behind it still commands attention.

Commissioned by the New Deal’s Treasury Relief Art Project with a June 30, 1936, deadline, the mural may be linked to an easel painting titled Frederick Douglass (c. 1935), referenced in the Smithsonian’s art inventories catalog. Scholarship notes that it most likely served as a preparatory study for Motley’s larger work.

Howard President Mordecai Johnson and art department chair James V. Herring supported Motley by providing housing and appointing him visiting instructor. Motley was known for vibrant depictions of African American life in Chicago, capturing Jazz Age energy through bold color, stylized figures, and layered narratives that challenged racial stereotypes.

His work stands as a cornerstone of early 20th-century Black visual culture.

The Douglass Hall mural illustrated key moments from Frederick Douglass’s life and was installed prominently in the main entrance hall. Regrettably, the mural vanished under later alterations, and no photographs have been discovered. Despite its loss, the work represents a significant intersection of Black art, education, and public investment during the New Deal era.

Motley’s legacy continues at Howard University today. The Howard University Gallery of Art, one of the oldest galleries at a historically Black college, holds several of his works including The Picnic (1934), Saturday Night (1935). Barbeque (1935), and The Liar (1936). Together with his other paintings of this era— Black Belt (1934), Between Acts (1935), Africa (1937), and Carnival (1937)—Motley illuminates the beauty and vitality of Black life.

Archibald Motley posing with his work Portrait of My Mother (c. 1930) at the Thirty-Sixth Annual Exhibition by Artists of Chicago and Vicinity at the Art Institute of Chicago, February 11, 1932. A trailblazer of the Harlem Renaissance, Motley used his art to make Black life visible, vibrant, and unapologetically central to the American story.

Opposite, clockwise from top left: Details from The Liar (1936), Barbeque (1935), Saturday Night (1935), and The Picnic (1934)

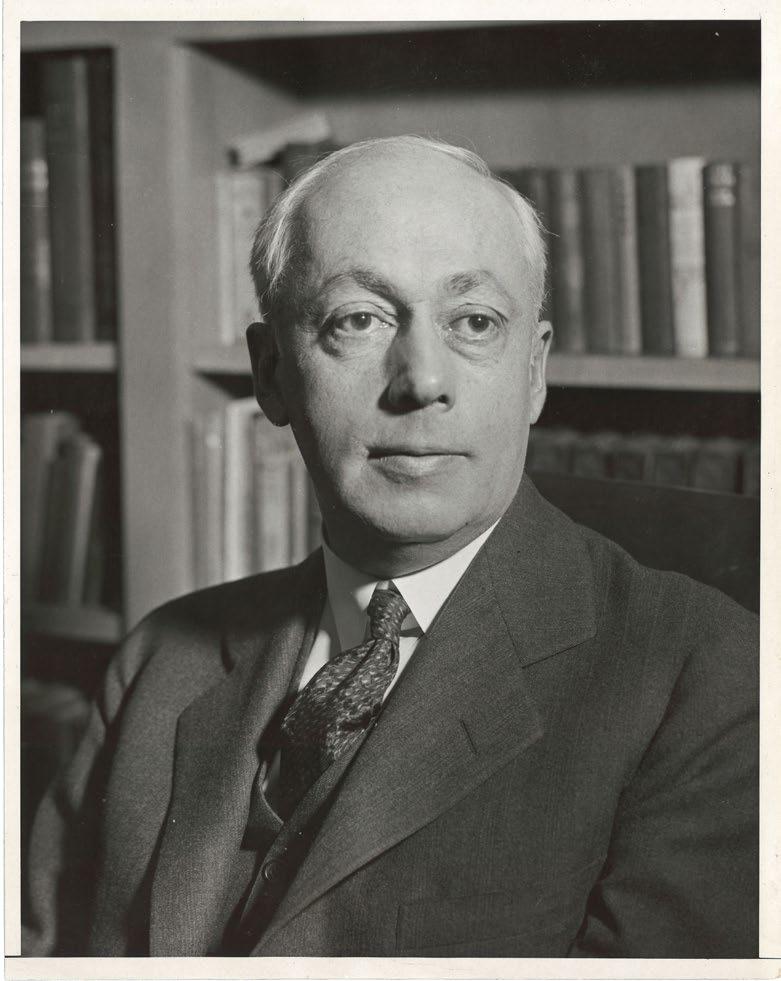

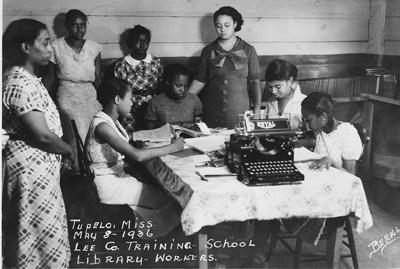

1936 print of the distinguished Howard University Glee Club, directed by

A year earlier, the ensemble performed at the dedication of

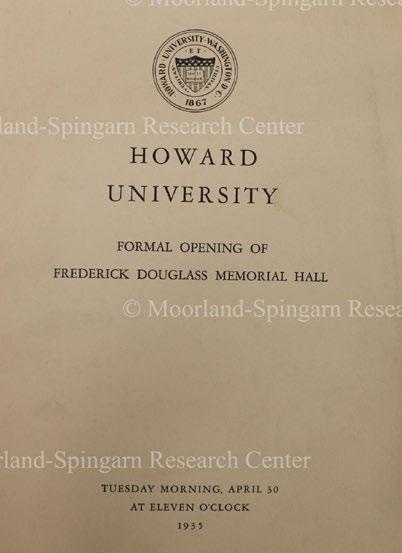

On Tuesday, April 30, 1935, the Howard University community gathered in a moment of ceremony and significance to mark the opening of Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall. Dedications like this one brought together architecture, politics, education, and legacy in public view. In recalling the details of that day, we glimpse the ideals and ambitions etched into brick and stone, marking the promise of Howard’s ambitions.

The Washington Tribune reported a crisp morning, where “the chilly wind played havoc with the hats of hundreds of spectators.” The ceremony opened with music from the University Glee Club. Under the direction of Professor Roy M. Tibbs, a gifted pianist, educator, and the Glee Club’s founder, one can imagine the ensemble lifting Howard’s “Alma Mater,” giving voice to the values Douglass Hall was to uphold.

The Reverend Howard Thurman gave the invocation, adding spiritual weight to the proceedings. President Mordecai Wyatt Johnson followed, offering greetings and describing the new educational classroom

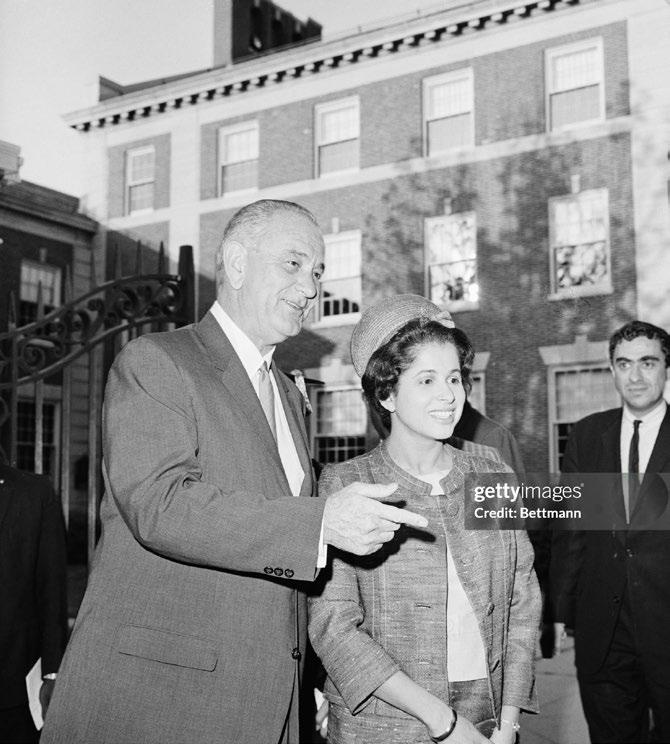

building as “the fulfillment of the Howard dream that started back in 1867.” He presented Albert I. Cassell, the architect and vision behind what the Tribune called “the beautiful American-structured edifice.” Johnson also read a letter from Helen Pitts Douglass, the second wife and widow of Frederick Douglass.

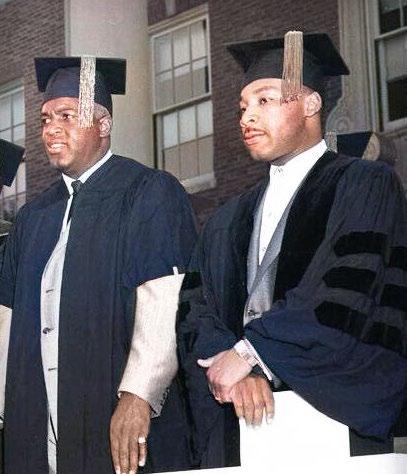

Several members of the Douglass family attended this momentous occasion: Joseph H. Douglass and Haley G. Douglass, both grandsons of Frederick Douglass, accompanied by their wives, and Frederick S. Weaver, a great-grandson. During the dedication, Joseph Douglass, a nationally known violinist and music teacher, presented a portrait he had painted of his grandfather to the university president.

Major Philip B. Fleming, acting deputy administrator of the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works, formally presented the new building to Howard University on behalf of the federal government. He stood in for Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, head of the Public Works Administration, who could not attend

“We must bring to our classrooms an atmosphere of realism, a sense of the world … Our windows must face outward on life, not inward on cloistered gardens.”

Dr. Harry Woodburn Chase, Chancellor of New York University, Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall opening ceremony, April 30, 1935

due to pressing business commitments. Ickes had overseen the funding that made Douglass Hall possible. He was nationally recognized for his leadership in the New Deal and outspoken support of civil rights. According to the Tribune, Fleming praised the building as “a great achievement wholly satisfactory in every respect to the Administrator of Public Works,” and congratulated all who contributed to its construction.

Major Thad L. Hungate, chairman of the Board of Trustees of Howard University, accepted the building. He expressed his pleasure in receiving this important addition to the university’s educational resources. Justice James Cobb, a faculty member, also spoke, offering perspectives on the building’s significance to African American education and advancement.

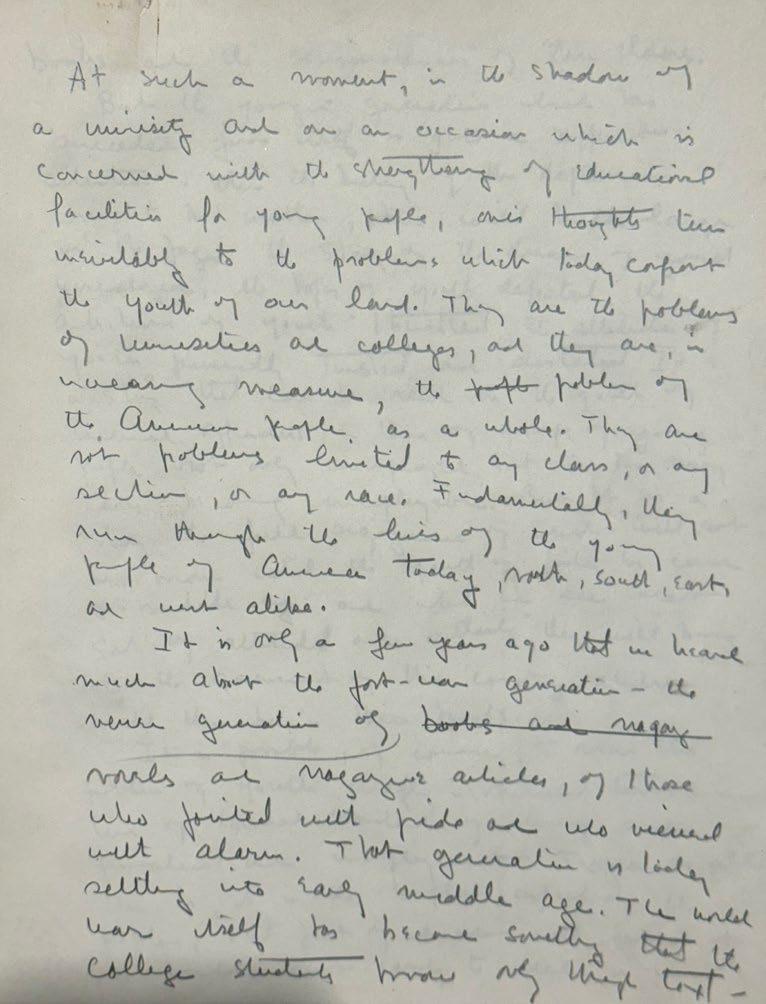

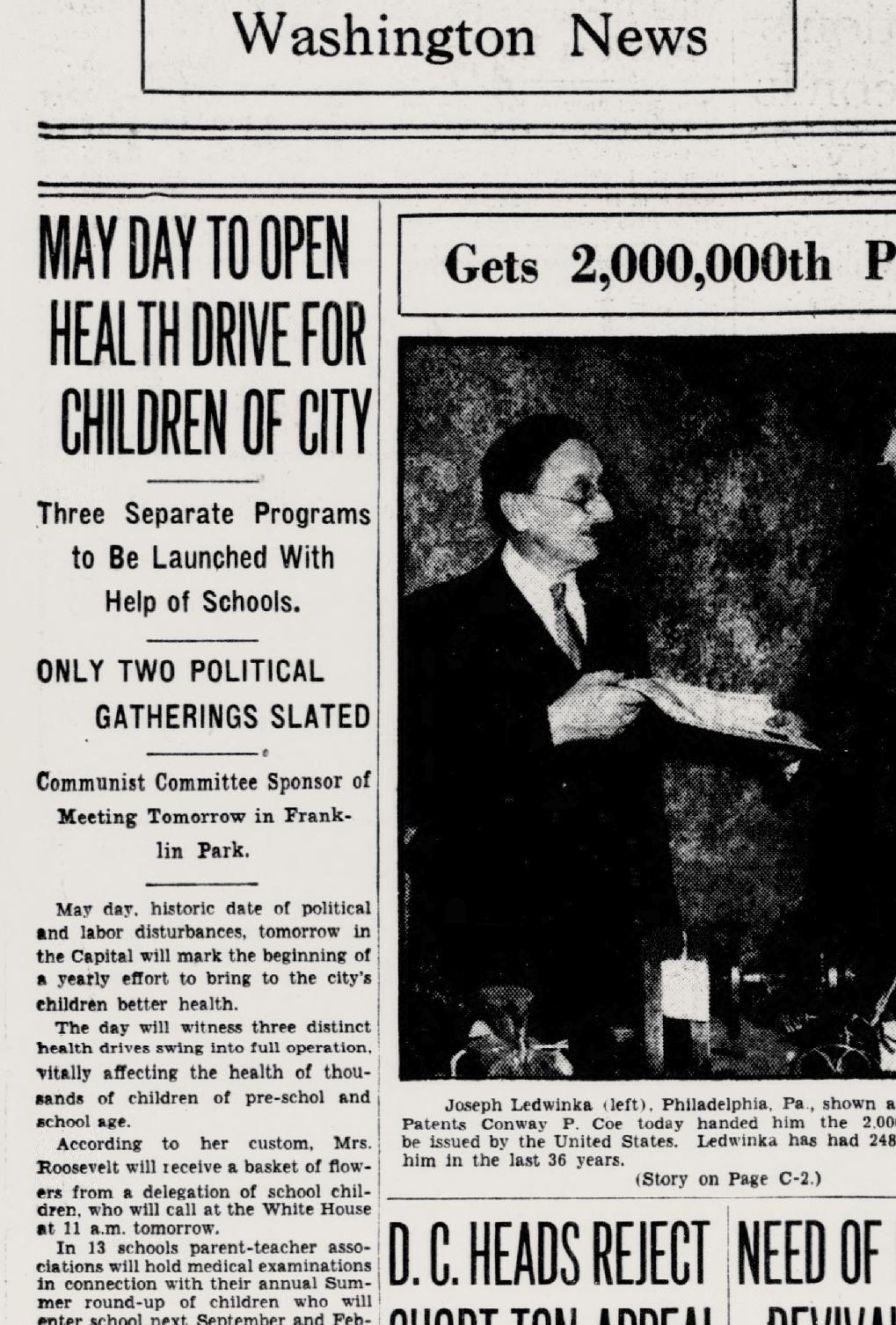

The final formal address came from Dr. Harry Woodburn Chase, chancellor of New York University. A respected voice in national academic circles, Chase paid tribute to Frederick Douglass as “a distinguished man … who will always remain an outstanding figure in the history of America” and framed the

dedication of the new hall as a symbol of upward struggle and educational progress. In his remarks, Chase addressed the crisis of the age, the disillusionment of youth amid economic depression and instability, and the responsibility of universities to respond. “Youth is at a crisis in philosophy and faith as well as in employment,” he warned, urging institutions to cultivate critical thought and social understanding. He called on colleges to “face resolutely the fact that they are set down in the midst of a complex and bewildering world,” and to prepare students not just for careers but for “the life of the mind and of the spirit.” Echoing this belief, he declared, “We must bring to our classrooms an atmosphere of realism, a sense of the world … Our windows must face outward on life, not inward on cloistered gardens.”

Chase spoke with particular passion about the role of universities in the defense of free speech and liberal democracy. “A university is only a university when it is free to seek for truth in every field; when its atmosphere is one, not of propaganda, but of cool and detached weighing of facts and conclusions,” he argued in a plea that may be as urgent to students today as it was in 1935. “Youth must

be trained in the American atmosphere of freedom of expression if American institutions are to survive.”

Chase’s words carried the weight of national concerns for a distinguished audience whose presence underscored the day’s importance. Representatives of the faculties of the nine schools and colleges of the university attended the ceremony as well as students, trustees, and dignitaries, including the Honorable Theodore A. Walters, first assistant secretary of the interior; Congressman James P. B. Duffy of Rochester, New York, where Frederick Douglass had lived for many years; and Dr. Clark Foreman, special counsel to the Secretary of the Interior, among others.

After the ceremony, members of Howard University’s ROTC guided visitors through the building’s halls, showcasing classrooms, lecture spaces, and offices filled with possibility.

That spring morning in 1935, Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall stood as a place that would prepare thinkers and changemakers for the world ahead. Today, it stands revered. And as always, it stands for Howard.

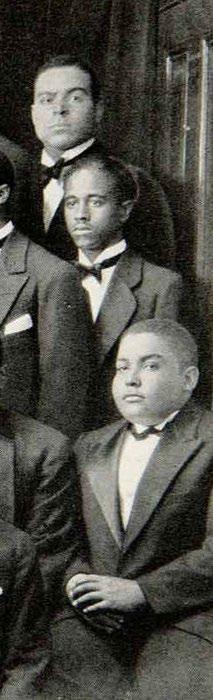

Dr.

Chase, chancellor of New York University, delivered the formal address of the Frederick Douglass Memorial

opening ceremony on April 30, 1935.

Howard University Board of Trustees,

Opposite: Article from The Evening

on the

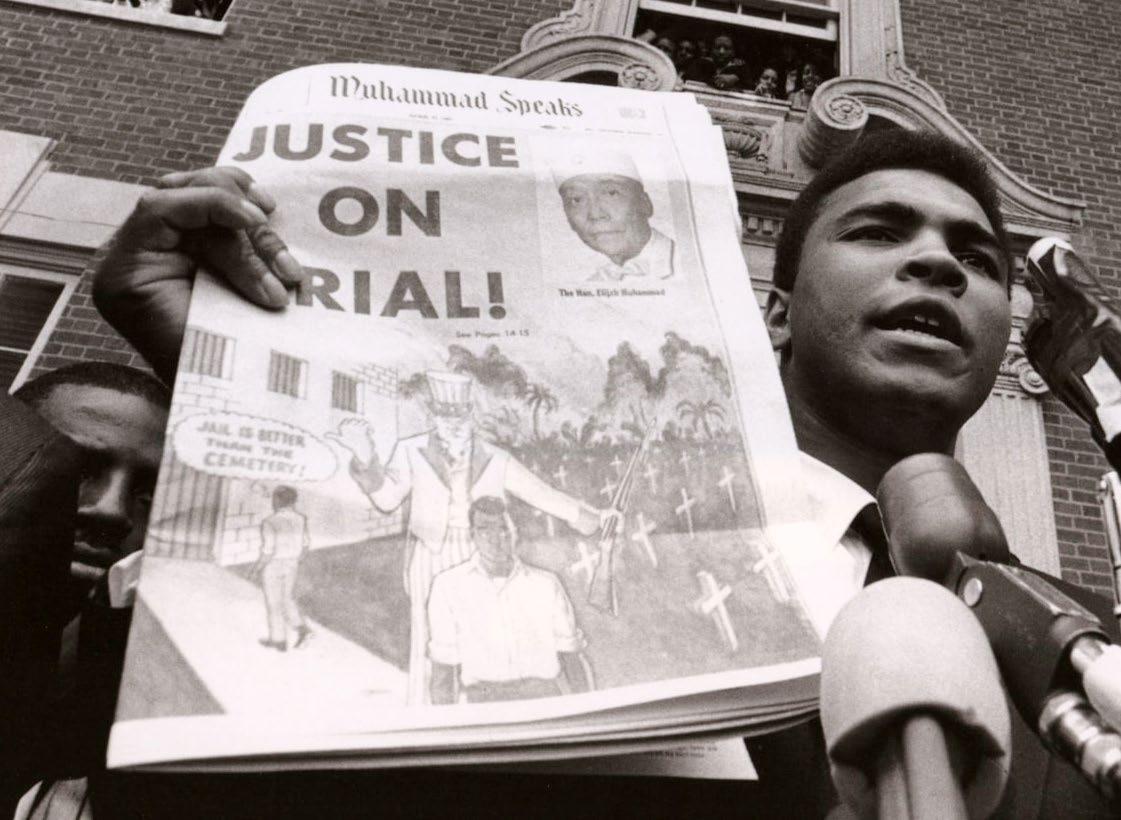

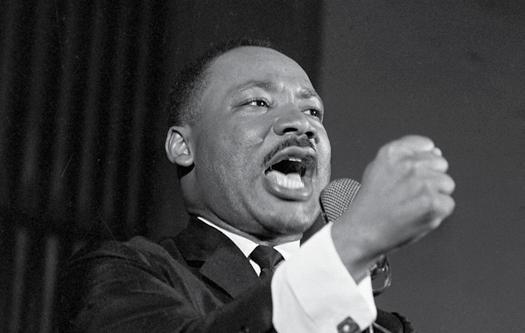

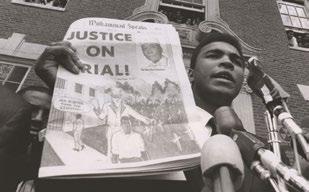

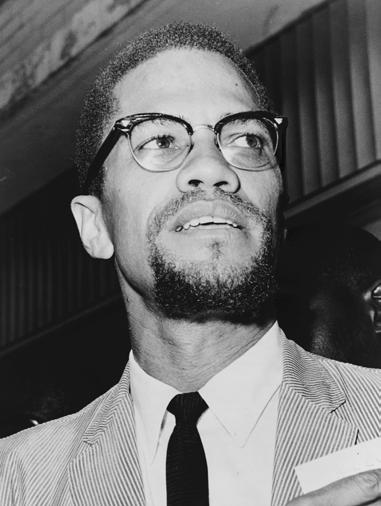

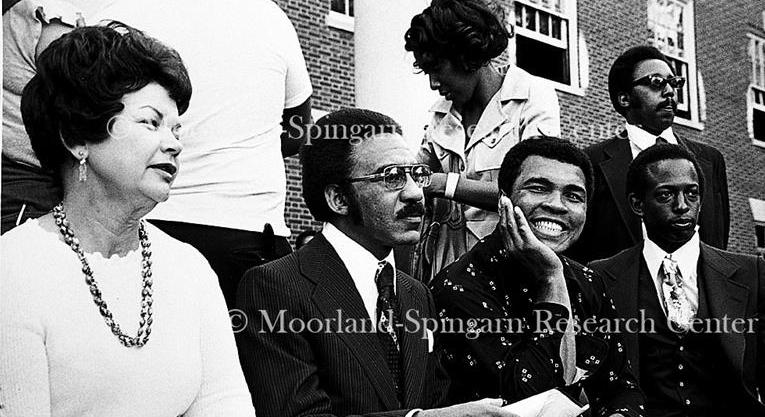

1967 Black is Best speech, in which Muhammad Ali exhorted students to abandon society’s concept of them and to fashion their own, based on pride in themselves and their people: “All you need to do is know yourself to set yourself free,” he said.

Enditatque modicid quaestis et fugia dolesero que audaesti omnimi, aute doluptur?

rooms. Today, these informal zones support collaboration, quiet reflection, and peer-topeer learning.

The first-floor corridor was opened to create a bright, inviting entry commons, a shift that created a “hall of learning” feel that anchors student experience in arrival and intention. Arched openings and original proportions were restored along the corridors, re-establishing a sense of rhythm and architectural clarity that had been obscured over time.

Teaching spaces were reassigned from individual departments to the registrar, allowing scheduling based on real-time academic needs. If political science was not meeting in the classroom, sociology could use the space. This shift unlocked capacity across the building, enabling departments to expand their offerings and collaborate more freely.

Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall stands as a proscenium and catalyst of American societal transformation. Dedicated in 1935 during the Great Depression, this academic building emerged from a specific historical context in which New Deal programs provided unprecedented funding for Black education through the Public Works Administration.

Classrooms were transformed to support a shift in teaching philosophy from passive lecture delivery to active, student-centered learning. The design introduces SCALE-UP environments, where round tables, flexible layouts, and mobile instruction promote collaboration. Interactive technology supports hands-on learning across disciplines, including shared screens, writable surfaces, and modular furnishings. Select original blackboards were preserved, maintaining a visual thread between past and present.

From its barrel-vaulted ceilings to its handcrafted millwork, the building required a meticulous preservation effort. In some cases, this work involved excavation and revelation. The discovery of a finely crafted fireplace, long entombed within the walls, marked the first hint of a forgotten elegance hidden beneath years of adaptation. As the restoration unfolded, ongoing efforts revealed bookshelves tucked within the frames of what had once been a grand library, their purpose obscured but never truly lost. These elements, unearthed and refinished, now stand as quiet tributes to the spirit of intellectual pursuit, evoking the timeless images of Frederick Douglass in his home library, surrounded by books, immersed in academic exploration.

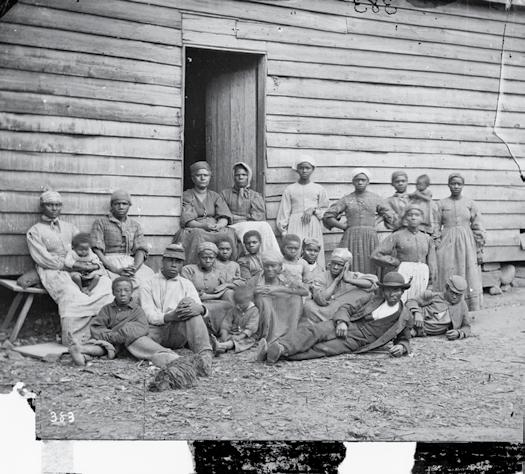

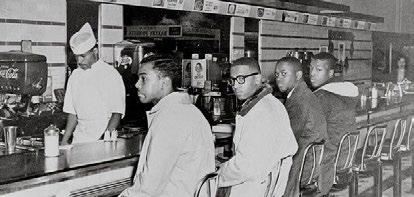

The hall’s construction took place against a backdrop of rigid segregation. While Jim Crow laws maintained racial boundaries across the American South, Howard University created intellectual spaces where African American scholars could develop the arguments that would ultimately dismantle legal segregation. The liberal arts departments housed within Douglass Hall, including History, Philosophy, English, Political Science, and Sociology, became incubators for revolutionary thinking.

This academic center materialized during the cultural flowering of the Harlem Renaissance and the economic devastation of the 1930s. Its walls witnessed students and faculty navigating