John Trevisa's Information Age: Knowledge and the Pursuit of Literature, c. 1400 Emily Steiner

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/john-trevisas-information-age-knowledge-and-the-pur suit-of-literature-c-1400-emily-steiner/

JohnTrevisa’ s InformationAge

JohnTrevisa’ s InformationAge

JohnTrevisa’ s

InformationAge

KnowledgeandthePursuit ofLiterature, c.1400

EMILYSTEINER

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©EmilySteiner2021

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted FirstEditionpublishedin2021

Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2021938599

ISBN978–0–19–289690–2

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780192896902.001.0001

PrintedandboundintheUKby TJBooksLimited

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

LITERATUREANDCULTURE

GeneralEditors

ArdisButterfieldandChristopherCannon

ThemonographseriesOxfordStudiesinMedievalLiteratureandCulture showcasestheplurilingualandmulticulturalqualityofmedievalliteratureand activelyseekstopromoteresearchthatnotonlyfocusesonthearrayofsubjects medievalistsnowpursue inliterature,theology,andphilosophy,insocial,political, jurisprudential,andintellectualhistory,thehistoryofart,andthehistoryof science butalsothatcombinesthesesubjectsproductively.Itoffersinnovative studiesontopicsthatmayinclude,butarenotlimitedto,manuscriptand bookhistory;languagesandliteraturesoftheglobalMiddleAges;raceandthe post-colonial;thedigitalhumanities,mediaandperformance;music;medicine;the historyofaffectandtheemotions;theliteratureandpracticesofdevotion;the theoryandhistoryofgenderandsexuality;ecocriticismandthe environment;theoriesofaesthetics;medievalism.

Acknowledgments

In2011,LawrenceJ.SchoenbergandBarbaraBrizdleSchoenbergdonatedtheir manuscriptcollectiontothePennLibraries.Thiscollection,thethemeofwhichis thetransmissionofknowledge,wasagame-changerforPennmedievalists.Larry feltstronglythathewoulddonatehiscollectiononlyiffacultyandstudentscould provethattheywoulduseitinteachingandresearch.SuddenlyIfoundmyself givingtalkstovisitorsaboutLatinencyclopedias,suchas Denaturarerum (LJS23),Frenchuniversalchronicles(LJS266),Meccacalculators(LJS434), andHebrewtreatisesonastronomy(LJS57).Thesetopicswerefaroutsideof myexpertiseinmedievalEnglishliterature,butafterafewyears,theystartedto getundermyskin.IevendesignedanewcoursecalledMedievalWorlds,so Iwouldhaveanopportunitytoshowcaseobjectsfromthecollection.Ithankthe Schoenbergsforexpandingmyworldviewandgivingmetheinspirationtowritea bookaboutmedievalcompendia.

Thereisnothinglikeaglobalpandemictomakeyouappreciatethelibrary. IwanttothankespeciallythelibrariansattheBodleianLibrary,theBritish Library,CambridgeUniversityLibrary,Chetham’sLibrary,PrincetonUniversity Library,StJohn’sCollegeLibrary,Cambridge,amongmanyotherswhohelped meaccessarchivalmaterialsovertheyears.Thetravelbaninsummer2020, duringthelastheadymonthsofbookrevision,mademetotallydependenton thekindnessofstrangers.Evenwithreducedoperationsandaskeletoncrew, LambethPalaceLibrarymanagedtosendmeadigitizedcopyofRanulfHigden’ s Distinctiones, andEmilyC.Runde,CuratorofMedievalandRenaissance CollectionsattheshutteredColumbiaLibrarytookphotographsformeofan alphabeticalindex.Icannotbegintothankallthewonderfullibrariansand scholarsonsocialmediawhosentmePDFsofarticles,microfilmcopies,screenshotsofcitations,andmore.

IamgratefultothegeneraleditorsforOxfordUniversityPress,Ardis ButterfieldandChristopherCannon,fortakingachanceonJohnTrevisa,and totheanonymousreadersforthePress,whogavethoroughfeedbackonmy manuscript.JoNorth’sandDanielDavies’seditorialassistanceandkeeneyessaw thebookthroughtotheend.AylinMalcolmandMargueriteLeoneprovided valuableresearchassistance.A first-yearcollegestudent,MichalLoren,turnedout tobeoneofthebestLatinistsIhaveevermet,andIthankherforhercareful readingsofthemanuscript.Iwouldliketothankmyworks-in-progressgroup ElizabethAllen,LisaLampert-Weissig,EmmaLipton,andMyraSeaman whose collectivewisdomisunrivaledamongmedievalscholars.MycherishedPenn

colleaguesRitaCopeland,ZacharyLesser,WhitneyTrettien,andDavidWallace commentedonchapterdraftsatthebusiesttimesoftheacademicyear,and IamevergratefultothemandtotheentirePennMed-Renworkinggroup.

Finally,IthankmyfamilyforrefrainingfromaskingmewhatIdowhenI’ m notteaching.Astheoldsayinggoes,that’sformetoknowandyouto findout.

ThisbookisdedicatedtoRitaCopelandandDavidWallace,mentors, colleagues,anddearestoffriends.

ListofIllustrations

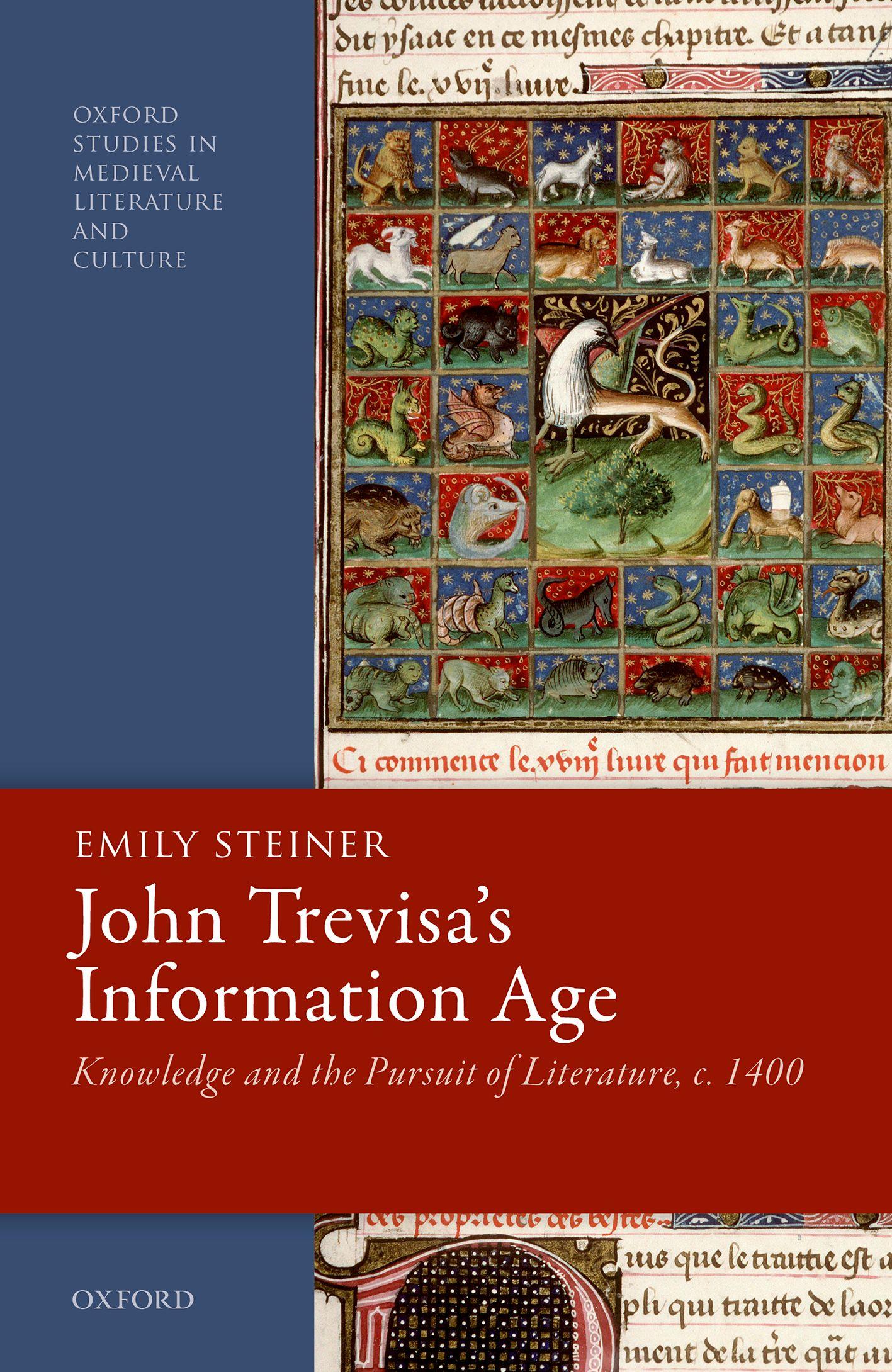

1.1aTableofcontentsandconcordancetothe MoraliainJob.Cambridge, CorpusChristiCollegeMS1,f.6r(c.1425–1450).Reproducedwith permissionoftheParkerLibrary.3

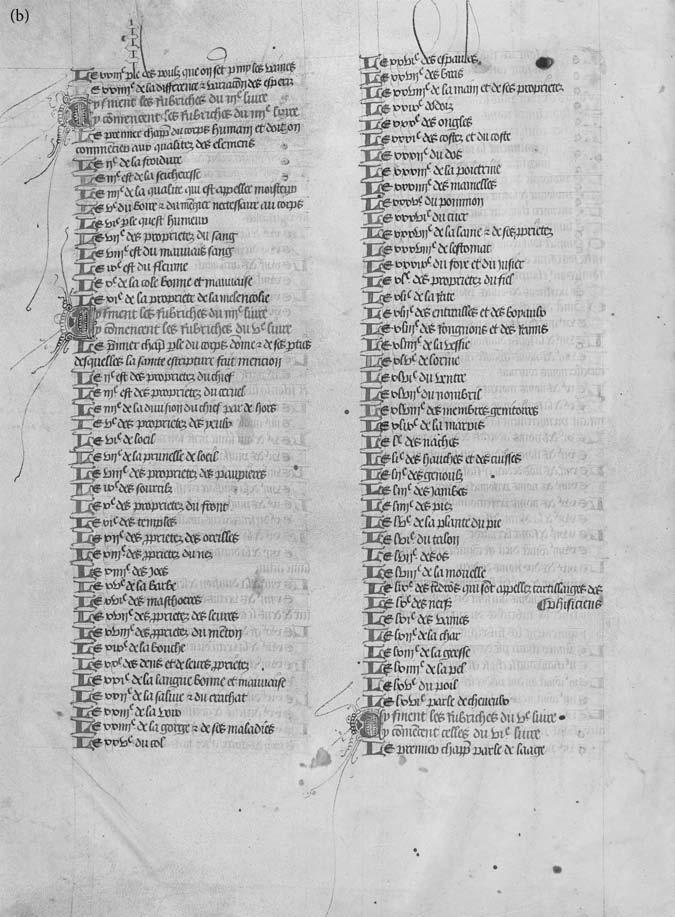

1.1bTableofcontents, Deproprietatibusrerum,tr.JeanCorbechon.Minneapolis, JamesFordBellLibrary,1400oBa(unfoliated)(early fifteenthcentury). ReproducedwithpermissionoftheJamesFordBellLibrary.4

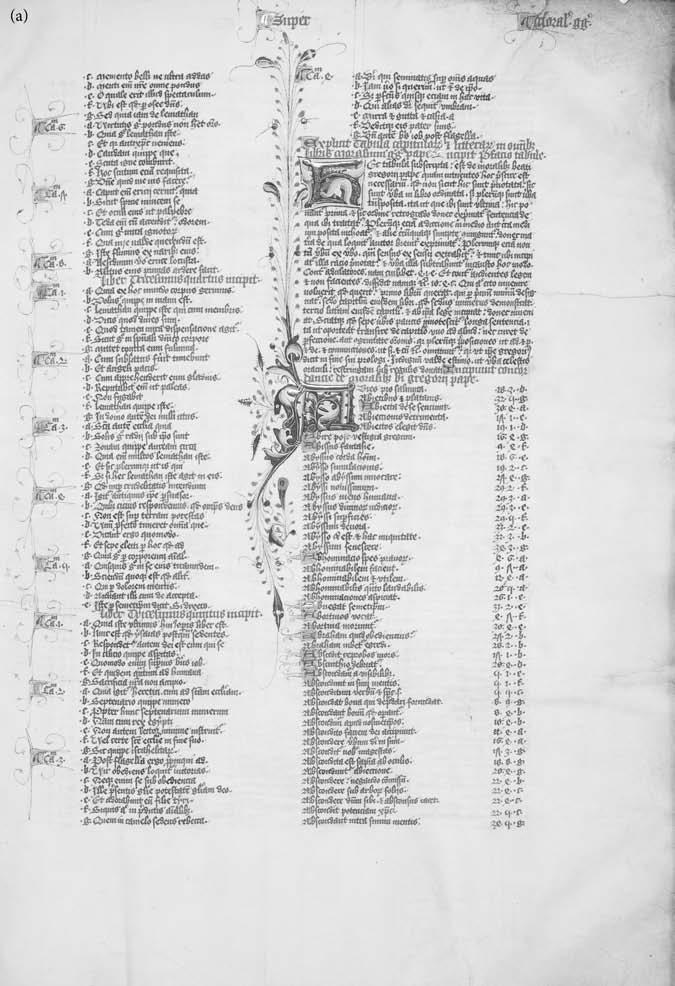

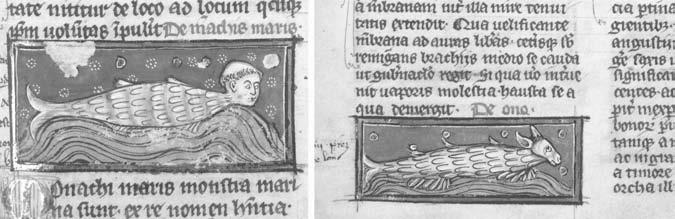

1.2ThomasofCantimpré, Liberdenaturarerum.Valenciennes,Bibliothèque Municipale,MS0320,f.117randf.117v(c.1290).Reproducedwith permissionoftheInstitutdeRechercheetd’HistoiredesTextes.6

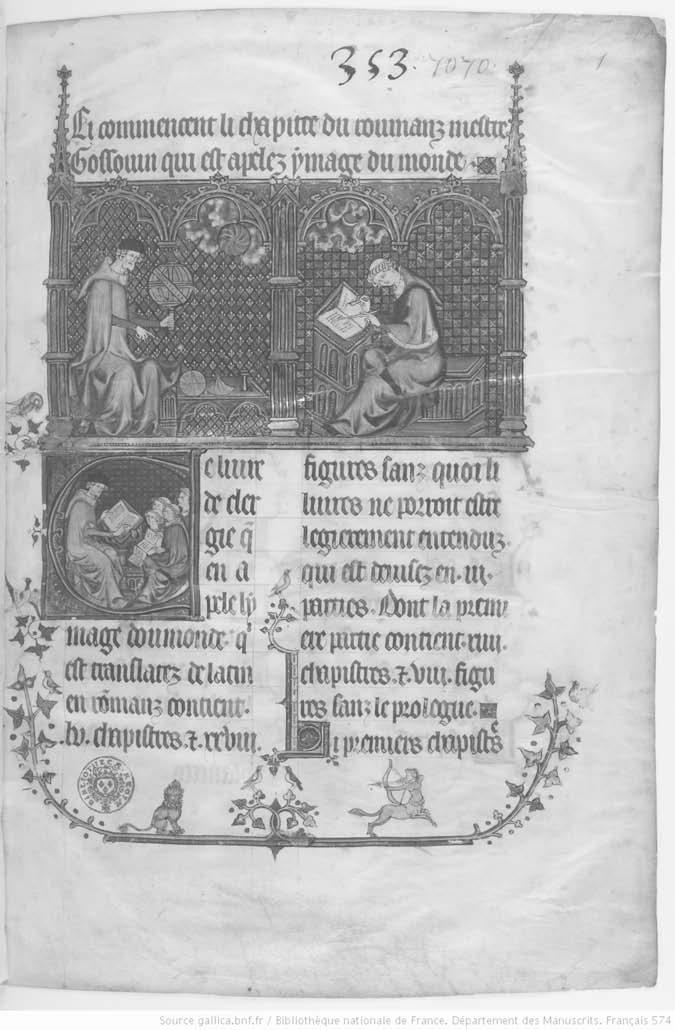

1.3GossouindeMetz, L’Imagedumonde.BibliothèquenationaledeFrance, MSFrançais574,f.1r(c.1300–1325).Reproducedwithpermissionof theBibliothèquenationaledeFrance.9

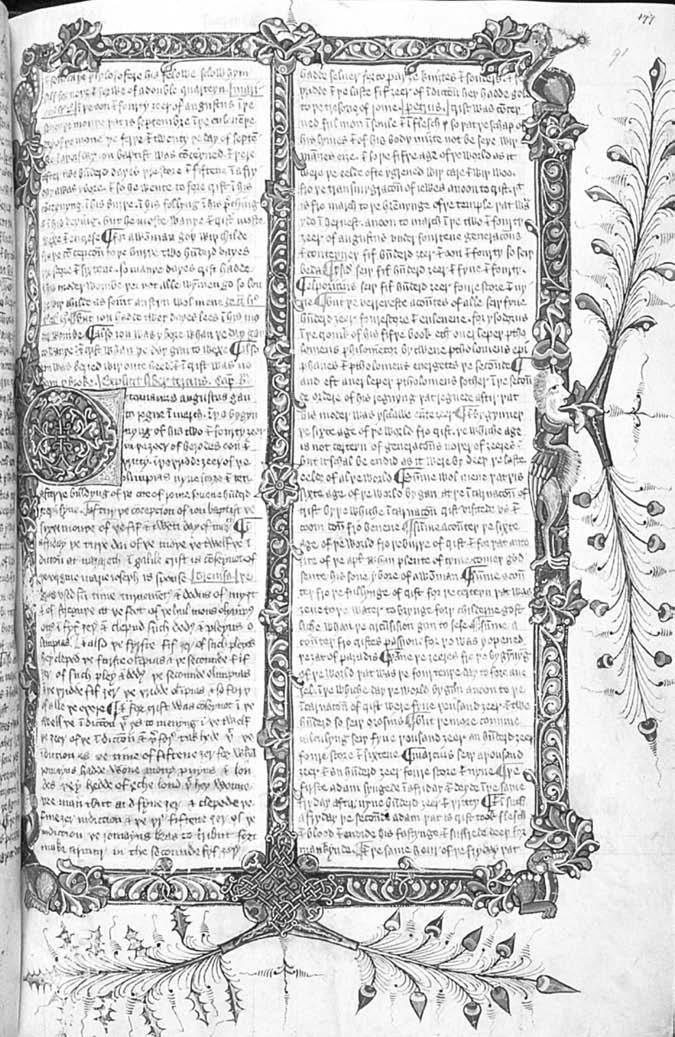

1.4RanulphHigden, Polychronicon,tr.JohnTrevisa.BritishLibrary, StoweMS65,f.59r(c.1400).Reproducedwithpermissionofthe BritishLibrary.20

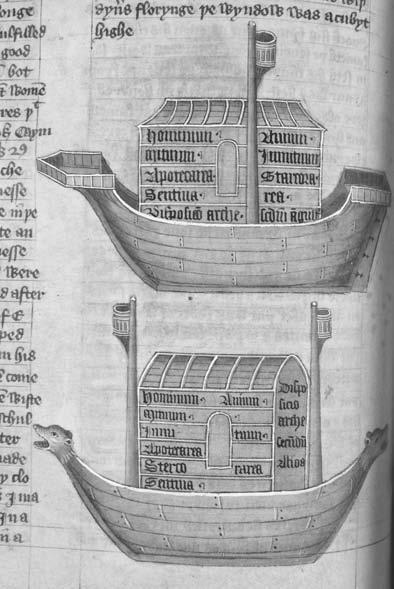

1.5RanulphHigden, Polycronicon, tr.JohnTrevisa.Cambridge, St.John’sCollegeLibrary,H.1,f.80v(c.1400–1425).Reproducedwith permissionofSt.John’sCollegeLibrary.21

1.6a Dialogusintermilitemetclericum,tr.JohnTrevisa.Cambridge, St.John’sCollegeLibrary,H.1,f.6r.(c.1400–1425).Reproducedwith permissionofSt.John’sCollegeLibrary.22

1.6bÉvrartdeTrémaugon(orPhilippedeMézières), LeSongeduvergier. Paris,BibliothèqueMazarine,MS3522,f.2v.Reproducedwithpermission oftheBibliothèqueMazarineandInstitutdeRechercheetd’Histoire desTextes.22

1.7BartholomaeusAnglicus, Deproprietatibusrerum,tr.JeanCorbechon. Reims,Bibliothèquemunicipale,MS0993,f.8.Reproducedwith permissionoftheInstitutdeRechercheetd’HistoiredesTextes.24

2.1RanulphHigden, Polychronicon.HuntingdonLibrary,HM132,f.5v (mid-fourteenthcentury).ReproducedwithpermissionoftheHuntington Library.31

2.2 Liberdepomo.BibliothèquenationaledeFrance,MSItalien917,f.37r (c.1275).ReproducedwithpermissionoftheBibliothèquenationale deFrance.51

4.1PrayerBook,BritishLibrary,HarleyMS3828,f.28(Netherlands, c.1450). ReproducedwithpermissionoftheBritishLibrary.109

4.2SubjectindextoNicoleOresme’stranslationofandcommentaryon Aristotle’ s Ethics.BibliothèquenationaledeFrance,MSFrançais9106, f.337r(c.1398).ReproducedwithpermissionoftheBibliothèque nationaledeFrance.114

4.3AlphabeticalindextoRanulphHigden, Polychronicon.BritishLibrary, Royal13EI,f.242(England,secondhalfofthefourteenthcentury). ReproducedwithpermissionoftheBritishLibrary.116

4.4aand4.4bN-O-P.AlphabeticalindexestoRanulphHigden, Polychronicon. Manchester,Chetham’sLibrary,A.90,f.55randf.69r (Gloucestershire, c.1400).Reproducedwithpermissionof Chetham’sLibrary.118

4.5Þ-3-W.AlphabeticalindextoRanulphHigden, Polychronicon. Manchester, Chetham’sLibrary,A.6.90,f.73r(c.1400).Reproducedwithpermission ofChetham’sLibrary120

4.6 Polychronicon.Tokyo,SenshuUniversity,MS1(1400–1425). ReproducedwithpermissionofSenshuUniversity.131

5.1WynkyndeWorde’s1495editionof Deproprietatibusrerum.University ofPennsylvaniaLibrary,FolioIncB-143.Reproducedwithpermission oftheUniversityofPennsylvaniaLibraries.146

5.2Elementsandzodiac.BartholomaeusAnglicus, Deproprietatibusrerum, trans.JeanCorbechon.BibliothèquenationaledeFrance,MSFrançais135, f.285(LeMans, c.1430–1450).Reproducedwithpermissionofthe BibliothèquenationaledeFrance.154

6.1Zodiac.LeLivredeSydrac.Lyon,BibliothèqueMunicipale,MS0948,f.146v. ReproducedwithpermissionoftheInstitutdeRechercheetd’Histoiredes Textes.182

6.2 LeLivredeSydrac,illustratedbyJeannedeMontbastonfortheQueenof Navarre,f.5(c.1338–1353).Privatecollection.Reproducedwithpermission ofLesEnluminures.183

6.3JacobvanMaerlant, Dernaturenbloeme. TheHague,Koninklijke BibliotheekKA16,f.41r(Flanders, c.1350).Reproducedwithpermission oftheKoninklijkeBibliotheek.184

6.4aand6.4b L’Imagedumonde and LeLivredeSydrac.CambridgeUniversity Library,MSGg.1.1(c.1320)f.359randf.510r.Reproducedwith permissionoftheCambridgeUniversityLibrary.187

ParisinGloucestershire

WhatwouldmedievalEnglishliteraturelooklikeifwevieweditthroughthelensof thecompendium?Inthatcase,Chaucer’scontemporary,JohnTrevisa,mightcome intofocusasthemajorauthorofthefourteenthcentury.Trevisa(d.1402)madea careeroftranslatingbiginformationalLatintextsintoEnglishprose,supportedby thepatronageofthebaronThomasdeBerkeley(1352/3–1417).Theseincluded RanulphHigden’ s Polychronicon (c.1327–1352,translationdedicatedtoBerkeley in1387),anenormousuniversalhistorywithcontinuationstothepresent; BartholomaeusAnglicus’swell-knownnaturalencyclopedia Deproprietatibus rerum (c.1240,translationdedicatedtoBerkeleyin1398);andGilesofRome’ s belovedmirror-for-princesmanual, Deregimineprincipum (c.1277–1280,trans. before1402).Thesewereshrewdchoices,accessibleandontrend: Deproprietatibusrerum and Deregimineprincipum hadalreadybeentranslatedintoFrenchand copiedindeluxemanuscriptsfortheFrenchandEnglishnobility,andthe Polychronicon hadbeencirculatinginEnglandforseveraldecades.

ThisbookarguesthatTrevisa’stranslationsofcompendioustextsdisclosean alternativeliteraryhistorybywayofinformationculture.ModernreaderstypicallyencountermedievalEnglishliteraturethroughTrevisa’scontemporaries, Chaucer,Gower,andLangland,atriumviraterepresentingarangeofliterary stylesandlanguagesformativetoEnglishletters.Howmightthenatureofthis encounterchangeifJohnTrevisawasinthemix?Canbiginformationalgenres giveusapurchaseonmedievalEnglishpoetryandprose?Andhowmight Trevisa’soeuvreenableustoenvisionanewliteraryhistoryrootedinthe compilationandtranslationofcompendiousinformationalongsidetextstraditionallylabeledasliterary?

AnInformationAge

Trevisa’sthreemajortranslationsfallundertherubricof “compendia,” bywhich Imeantextsdesignedtosynthesize,summarize,andsystematizealotofinformationaboutasubject,or,inMaryFranklin-Brown ’sdefinition, “toprovidea comprehensiveoverviewofknowledge,toorganizeit,andtopropagateit.”¹

¹Franklin-Brown, ReadingtheWorld,9.

JohnTrevisa’sInformationAge:KnowledgeandthePursuitofLiterature ,c. 1400

©EmilySteiner2021.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780192896902.003.0001

.EmilySteiner,OxfordUniversityPress.

Acompendium,inotherwords,referstobotha kind oftextanda process through whichknowledgeaboutasubjectorsubjectsiscompiled.Medievalwritersgive thesetextsavarietyoftitles: compendium, florilegium , speculum,orsimply liber, titlesthattellusfairlylittleaboutgenre.Theword encyclopedia,thoughapostmedievaltermassociatedwithsecularmodernity,canbeusedtodescribea subgenreofthemedievalcompendium,onethatassemblesinformationabout manysubjectsinoneplace,withanemphasisonthecreatedphysicalworld.² Bartholomaeus’ s Deproprietatibusrerum,forexample,dividesitsmaterialsinto theheavenlyorders,thesoul,senses,thehumanbody,diseases,estates,planets, elements,timesandseasons,birdsandbeasts,stonesandminerals,trees,regions, musicalinstruments,weightsandmeasures,andbeverages.

Compendiousgenres,whethernaturalhistories,legalsummae,universal chronicles,orpreachers ’ manuals,dosharesomegenericfeatures,suchasform (theytendtobelargetextsdividedintomanysmallerunits),subject(useful information),andfunction(readyandconvenientaccesstoinformation).They alsoshareaconceptof ordo ororderingsystem,whichsimultaneouslyaidstheuse ofthetextandstandsinfortotalknowledgeofitssubject.Forinstance,Higden’ s universalhistory,the Polychronicon,followsachronologicalorder,dividedinto sevenbookscorrespondingtothesevendaysofcreation,whereas Deproprietatibusrerum,dividedintonineteen(orsometimestwenty)books,followsahierarchicalscheme,beginningwithGodandtheangels.Eachbookof De proprietatibusrerum isfurtherdividedtopicallyoralphabeticallyorboth.

Oftenwithmedievalcompendia,theirgenericandphysicalfeaturesareoneand thesame:aswithamodernreferenceset,suchasthe EncyclopediaBritannica,ora worldatlas,youknowonewhenyouseeone,andindeed,recognitioniskeyto navigation.Forthisreason,bothmedievalandmoderncompendiatendtohave distinctivelayouts:shortentries,impressivebulk,numberingsystems,diagrams, indexes,tablesofcontents,glossaries,andmore.Perhapsmorethananyother genre,thecompendiumismoreidentifiablefromadistancethanitiscloseup. Differentlyfrommodernreferencebooks,however,medievalcompendiashowoff therelationshipbetweeninformationandluxury.Tobesure,thepriceofabound EncyclopediaBritannica continuestobehigh(around$1,500foraset),though mostreaderstodaywould findsuchapurchaseoutmoded.IntheMiddleAges, eventhemostmodestcompendiawereextremelycostlytoproducebecausethey requiredsomuchmaterialandsuchahighleveloforganization.Themanylavish compendiaproducedinthelaterMiddleAges,asexemplifiedbytheconcordance tothe MoraliainJob inFigure1.1aorthetableofcontentstoJeanCorbechon’ s translationof Deproprietatibusrerum inFigure1.1b theapogeeofencyclopedic luxury flaunttheresourcesneededtomakeinformationbeautiful.

²SeeTwomey, “InventingtheEncyclopedia” foradiscussionoftheterm,andalsoMuhanna’ s perceptivecommentsin “WhyWastheFourteenthCenturyaCenturyofArabicEncyclopedism?,” 345–47.

Figure1.1a Tableofcontentsandconcordancetothe MoraliainJob.Cambridge, CorpusChristiCollegeMS1,f.6r(c.1425–1450).Reproducedwithpermissionofthe ParkerLibrary.

Minneapolis,JamesFordBellLibrary,1400oBa(unfoliated)(early fifteenthcentury). ReproducedwithpermissionoftheJamesFordBellLibrary.

Figure1.1b Tableofcontents, Deproprietatibusrerum,tr.JeanCorbechon.Thethirteenththrough fifteenthcenturieswastrulyaninformationagein WesternEurope,anagethatwitnessedanexplosionofreferencebooksbothin Latinandinthevernaculars.Theseincludebiblicalconcordances,suchasHughof St.Cher’s(c.1230),and distinctiones collections,suchasThomasofIreland’ s Manipulus florum (c.1300),collectionsofpreachingtopics,suchasJohn Bromyard’ s Summapraedicantium (1330s),digestsofcanonlaw,suchasthe Repertoriumiuriscanonici byPetrusdeBraco(d.1352),andalphabeticalsubject indexes,suchastheonecreatedforthe MoraliainJob byThomasHorsted (c.1350).³Theyalsoincludemore “literary” texts:universalhistories,suchas VincentofBeauvais’ s Speculumhistoriale (c.1260),universalgenealogiessuchas Lachroniqueanonymeuniverselle;andmanynaturalencyclopediascompiled betweenthe1240sandthe1260s,suchasGossouindeMetz’ s L’Imagedu monde andBartholomaeus’ s Deproprietatibusrerum.Theseoldschool “Wikipedias” weremajorscholarlygenresofthelaterMiddleAgesandstaples ofmedievalbookcollections. ⁴

Theresemblancesbetweenmedievalandmoderncompendianotwithstanding, therearecrucialdifferencesbetweenthem.Unliketheirpost-medievalcounterparts,forexample,medievalcompilersgenerallystrovetobecomprehensivebut notexhaustive.Formanycompilersthegoalwastoassemblenotfactsbut authorities,whosedivergentaccountswereoftenplacedsidebysidewithlittle attempttoreconcilethemoreliminateredundancies.Forthatreason,asFranklinBrownobserves,compendiainthisperiodtendtobe “discursivelyheterogenous” and “‘heterotopias’ ofknowledge – thatis,spaceswheremanypossiblewaysfor knowingarejuxtaposed, ” and,assuch, “servedaslibrariesinminiatureatatime whenlearninginallitsplethoricdiversity,wasinhighdemand.”⁵ Likewise, medievalreferencebookstendtobestructurallyaccretive:forexample,auniversal historymightbebroughtuptodate,asHigden’ s Polychronicon wasbyTrevisa, AdamUsk,theWestminsterchronicler,andtheprinterWilliamCaxton,andover timeanaturalencyclopediasuchas Deproprietatibusrerum mightaccumulate authoritiesandevenwholechaptersonthepropertiesoftheelephant.Ifaccretion andredactionarecharacteristicsofamanuscriptcultureinwhicheachtextual objectisunique,theyarealsoimportantstructuralfeaturesofmedievalcompendiousgenres.

Fromadifferentangle,formedievalcompilers,noteverythingneededknowing, andnoteverythingthatwasknownneededtoberecorded(anauthoritativeentry

³SeeChapter4,p.121ff.

⁴ ForoverviewsseeRouseandRouse, Preachers,Florilegia,andSermons; AuthenticWitnesses; ManuscriptsandtheirMakers;andSteiner, “CompendiousGenres.” SeealsoTwomey’sappendixon “MedievalEncyclopedias” inKaske, MedievalChristianLiteraryImagery. ⁵ Franklin-Brown, ReadingtheWorld,6–8.SeealsoMeier, “OntheConnectionbetween EpistemologyandEncyclopedic Ordo. ” Themanymedievalmiscellaniesdesignedtocontainmultiple andoverlappingencyclopediassuggestfurtherthatcomprehensivenesswastheobject,notexhaustive mastery.

Figure1.2 ThomasofCantimpré, Liberdenaturarerum.Valenciennes,Bibliothèque Municipale,MS0320,f.117randf.117v(c.1290).Reproducedwithpermissionofthe InstitutdeRechercheetd’HistoiredesTextes.

onshellfishmightomitthescallop,forinstance).⁶ Nordideverydetailina medievalnaturalencyclopediarequireconfirmationthroughobservationor experience orevenauthority.Totakeoneexample,BartholomaeusAnglicus includesinhis Deproprietatibusrerum bothkeenlydetailedobservationson migrainesandfabulousdescriptionsofmonstrousraces.Totakeanotherexample, ThomasofCantimpré(d.1272),inhis Denaturarerum,inthesectionon fish(see Figure1.2),proliferatesentriesforthedogfishandmonkfishintothecow-fish, rabbit- fish,anddonkey-fish.Illustratedmanuscriptsemphasizetheaesthetic pleasuresofproliferation,notunlikeearliercollectionsofprodigiessuchasthe Libermonstrorum .WhatMarciaColishwritesaboutmedievalwritersgenerally holdsespeciallytrueforcompendiouswriters:theyseemtohavebeenwillingto “liveinmorethanoneimaginativeuniverseatatime.”⁷

Whethertheycontainmanyentriesorfew,attestedorfantastical,whether organizedconceptuallyoralphabetically,medievalcompendiatendtoprioritize varietyandplentitudeoverexhaustivemastery.Thisprincipleisastruefor theologicalcompendiaasitisfornaturalencyclopedias.Anotableexceptionis VincentofBeauvais,whosemassive Speculumnaturale,itselfonlyoneoutofthree booksofhis Speculummaius,ispainstakinglysubdividedinto32booksand3,718 chaptersonsubjectsrangingfromhumanreproduction,togeography,toprecious stones.Notsurprisingly,avolumeofthissizeandscope,alongsidemassive biblicalconcordances,suchastheoneassembledbytheDominicanteamofSt. JacquesinParis(c.1230;1280–1330),helpedtogeneratenavigationalaids,suchas subdivisions,tablesofcontents,andalphabeticalindexes,onwhichpost-medieval compilerscontinuedtorely(seeChapter4).

⁶ Onthispoint,seeZahora’sintroductionto Nature,Virtue, andtheBoundariesofEncyclopedic Knowledge

⁷ Colish, “WhendidtheMiddleAgesEnd?,” 216.

Bycontrast,however,manymedievalcompendiaaregiganticwithoutbeing fullycomprehensive.Astrikingexampleis Omnebonum (BritishLibrary,Royal MS6EVI/1andRoyalMS6EVII/1),compiledandwrittenbyJameslePalmer,a clerkoftheExchequerin1357. Omnebonum isastaggeringfour-volume,1,100folia,illustratedLatinencyclopedia,acompendiumofcompendia,containing 1,350topicsorganizedfrom Absolucio to Zacharias. ⁸ YetlettercategoriesN–Z includeonlyoneentryeach:perhapsthecompilerloststeamtwothirdsoftheway through,⁹ orperhapshiswassimplyacaseofpoorplanning. Omnebonum would certainlyhavebeenadifficultfeatforanyonetorepeat.Andyetmedievalwriters understoodthatacompendiumcouldbeusefulwithoutbeingexhaustive,either becauseitcateredtotheneedsofspecializedaudiences,suchassermon-writers,or becauseitcouldbeenlargedinsubsequentversionsandmanuscripts.AnnBlair hasbrilliantlychartedthemanywaysinwhichearlymodernauthorscopedwith theproblemofhavingtoomuchtoknow.Generallyspeaking,medievalwriters didnotworryabouthavingtoomuchtoknow,notbecausetherewasn’tenoughto knowbeforeglobalexpansionandtheprintingpress,butratherbecause,unlike theirearlymoderncounterparts,theyfeltlessofanincentivetorecorditallatone timeinoneplace.¹⁰

Althoughallkindsofcompendiousgenres flourishedinthisperiod,several notableencyclopediaswereproducedinpreviouscenturieswhichprovidedcontentforlaterreferencebooks.¹¹ThemostinfluentialwasIsidoreofSeville’ s seventh-centurysumma,the Etymologies,whichtransmittedclassicallearningto theearlyMiddleAgesandwhich “offeredalong-influentialmodelforinformation management.”¹²Pliny’ s NaturalHistory (c.77–79 ),whichcelebratesthe “abundanceofaccumulation,” wasalsoasourceandamodelforlaterencyclopedists andanimportantthroughlinefrommedievaltoearlymodern.¹³Othersignificant chronologicaloutliersincludeRabanusMaurus’s(d.865) Deuniverso (or De rerumnaturis)andLambertofSt.Omer’sidiosyncratic Liber floridus (Bookof Flowers)compiledintheearlytwelfthcentury.¹⁴ Alsocriticaltothedevelopment ofthirteenth-centurynaturalencyclopediaswerethenumerousbestiariesand aviariesassembledinmonasticscriptoriafromthetenththroughtwelfthcenturies,¹⁵ inadditiontoseveraltwelfth-centuryencyclopedictreatisessuchasAlain deLille’sversified Anticlaudianus and DeplanctuNaturae (which,together,cover

⁸ Digitizedathttp://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=royal_ms_6_e_vi!2.

⁹ SeeSandler, OmneBonum

¹⁰ Blair, TooMuchtoKnow,12. “Anewattitudetowardseekingoutandstockpilinginformationwas thecrucialcauseoftheinformationexplosion,moresignificantthananyparticularnewdiscovery.”

¹¹Foranoverviewofsomeofthisearliermaterial,seeKeen, “ShiftingHorizons.”

¹²Blair, TooMuchtoKnow,18.

¹³Ibid.Forahelpfuloverviewofclassical “informationmanagement,” seeBlair, TooMuchtoKnow, chapter1.

¹⁴ SeeDerolez, MakingandMeaning.IthankProfessorDerolezfortakingthetimetoshowmethe manuscriptinperson.

¹⁵ SeeSteiner, “EncyclopedicBeasts.”

plants,birds,andbeasts,thevirtues,andtheliberalarts)andAlexanderNeckam’ s influential Denaturisrerum,amoralizedtreatiseonthecreatedworldthatserved asaprefacetohiscommentaryonEcclesiastes.¹⁶ Theseforerunnerswerecontent providersforlatermedievalencyclopedias.Relevant,too,tothelaterencyclopedic traditionarethemanyearlyherbalandmedicaltreatisescompiledintheMiddle Ages,fromWalafridStrabo’secstatic Hortulus (ninthcentury)toMatthaeus Platearius’salphabeticallyordered Circainstans (twelfthcentury;translatedin thethirteenthcenturyas LeLivredessimplesmédecines),areferencebookthat remainedpopularthroughtheageofprint.

Significantlyforthisstudy,thethirteenthandfourteenthcenturiesaremarked byamajorinitiativetocompilevernacularaswellasLatinreferencebooksandto translateLatinonesintothevernacular.TheearliesttextswerecompiledinLatin, largelyinFrance,butwereswiftlytranslatedintoEuropeanvernacularsand copiedforlayaswellasclericalreaderswellintothe fifteenthcenturyandthe ageofprint.¹ ⁷ AnimportantearlyexampleisGossouindeMetz’ s L’Imagedu monde (1240s),adaptedfromHonoriusofAutun’ s Imagomundi,andwhich survivesintwoverseandtwoproseversions(andinoverseventy-fivemanuscripts).¹⁸ Thirteenth-centuryLatinandvernacularencyclopedistslikeGossouin andBartholomaeusAnglicushelpedcreatesyllabiofgeneralknowledgesuitable forelitenon-academicaswellasacademicreaders,and,intheprocess,established whotheirreaderswere,whattheywantedtoknow,andinwhatform.

Weseethisprocessoftransmissionbeingworkedoutinindividualmanuscripts,as,forexample,BnFMSFrançais574(c.1300–1325),agorgeouscopyof theredactedversionoftheprose L’Imagedumonde,dedicatedtoGuillaumeFlote, chancellortoPhilipVI.Theproductionteamofthis “livredeclergie,” which wouldeventually finditswayintothecollectionofJean,DukeofBerry,sparedno expensedepictinguniversitymastersandstudentsstudyingthesevenliberalarts.

Italsosuppliedexquisitecosmographicaldiagrams,whichwerethestock-in-trade ofearlyastronomytextbooks,suchasJohannesdeSacrobosco’ s Tractatusde sphaera (c.1230),butwhichhereshowcasesthepairingofacademiclearningwith vernacularluxury.Thesplendidpaintingonthe firstfolio(Figure1.3)showsan astronomerwithhisastrolabedictatingtoatonsuredscribe,followedbyaninhabited capitalCdepictingtheastronomerlecturingtostudents.Thebook’sleisurely mise-en-pageanditscelebrationofhigherlearningstandinsomecontrasttothe epilogue,whichcomparesthebriefnessofencyclopedicentriestotheattentionspan

¹⁶ ForanexcellentrecentstudyofNeckam,seeZahora, Nature,Virtue,andtheBoundariesof EnyclopedicKnowledge. ¹⁷ Forrecentsurveysofmedievalencyclopedicliterature,seeMeier, “Encyclopedias”;Binkley,ed., Pre-ModernEncyclopaedicTexts;Ribémont, “OntheDefinitionofanEncyclopaedicGenre”;Twomey, “Encyclopedias” and “InventingtheEncyclopedia”;andSteiner, “EncyclopedicBeasts.”

¹⁸ SeeBrown, “TheVernacularUniverse.” TranslatedfromtheFrenchbytheprinterWilliam Caxtonin1481,possiblyfromFrenchmanuscriptBritishLibrary,RoyalMS19AIX(c.1464), The MirroroftheWorld wasprobablythe firstillustratedtextprintedinEngland.

Figure1.3 GossouindeMetz, L’Imagedumonde.BibliothèquenationaledeFrance, MSFrançais574,f.1r(c.1300–1325).ReproducedwithpermissionoftheBibliothèque nationaledeFrance.

andlifespanofthelaity.Ordinarypeoplepreferthingsthataresimpleanddon’ttake alongtimetoexplain(“debriefsenseetdebrieftens”).Afterall,theirlivesareshort andtheirbodiestransitory.Theirdayspassevermorequickly,thecenturiesrollby, anddeathcomesbeforeyouknowit.¹⁹

Like L’Imagedumonde,ThomasofCantimpré’sLatinencyclopedia Denatura rerum (before1244),extantinover150Latinmanuscripts,wasswiftlytranslated intoseveralvernaculars,mostsignificantlyintoDutchverse(Dernaturenbloeme, c.1273)bytheaccomplishedFlemishauthorJacobvanMaerlant(c.1230–1300). Maerlant’simpressiveoutputconsistedofversifiedtranslationsoftwoother compendiousreferencebooks,PeterComestor’ s Historiascholastica (1271)and VincentofBeauvais’ s Speculumhistoriale (after1272),inadditiontoearlier adaptationsofFrenchhistoriesofArthur,Troy,andAlexandertheGreat. BartholomaeusAnglicus’ s Deproprietatibusrerum,mentionedabove,anatural encyclopediawithalongshelf-life,wascompiled firstinLatinaround1240, translatedintomanyvernacularlanguages,includingFrench(byJean Corbechon, c.1372),English(byJohnTrevisa, c.1398),andDutch(trans.and printedbyJacobBallaert, c.1485)andcopiedintosomeofthemostluxurious manuscriptsofthelateMiddleAges.VincentofBeauvais’ senormous Speculum naturale (revisedversionbefore c.1260,translatedasthe Lemiroirdelanature) wasnotaswidelycirculatedashis Speculumhistoriale (Frenchtranslatedas Le miroirhistoriale byJeandeVignayforJeannedeBourgogne,QueenofFrance, c.1332;translatedintoDutchverseas Spiegelhistoriael byJacobvanMaerlant, after1282),butitwasbyfarthemostsystematic,comprehensive,anddetailedof thethirteenth-centurynaturalencyclopedias.²⁰

Bythe1260s,newencyclopediaswerebeingcompiledinthevernacular.Oneof themostsuccessfulexamplesofvernacularencyclopedismwas LiLivresdou trésor, firstcomposedinFrench c.1260forCharlesofAnjou,brotherofLouis IX,bythegreatFlorentinepoliticianBrunettoLatini,whoalsotranslateditinto Italian.The Trésor,extantinoveronehundredmanuscripts,andamajorsource forlaterencyclopediasandtravelnarratives,wasintendedforreaderswholacked specializedscientifictrainingbutwhowantedprivilegedaccesstoinformation.²¹ Dividedintothreesections,thenaturalworld(history,geography,bestiary,

¹⁹“Detoutesceschosesvousavonsnousconté et aucunesraisonsauplusbriévmentquenous poons,rendues,carlesgenzd’orendroitn’ontcuredelonguesgloses,ainzaimmentmieulzleschoses quisontbriés,commecilquisontdebriefsens et debrieftens.Leurviessontbrieves et leurcorssont brief;carenpetitdetenssontfeniz,ettouzjoursdevendrontplusbrief,tantqu’anoientvendront.Car cissieclestrespasse ]detensentensausicommevent, et defenistdejourenjour; et petitsejourifait chascuns,Cartantestplainsdevanité,qu’iln’iadeveritépoint;etcilquiplusicuidedemourerest souventcilquimainsidemeure et quiplustostmuert” (Priored., ImageduMonde,203).Compare withtheendingtotheverse L’Imagedumonde,ed.Connochie-Bourgne,6538ff.,quotedinChapter6 below,pp.177–78.

²⁰ ForanupdatedbibliographyonVincentofBeauvaisseehttp://www.vincentiusbelvacensis.eu/ index.html.

²¹SeeRoux, Mondesenminiatures,on Trésor manuscriptsandillustrations.

astronomy),Aristotelianethics,andCiceronianrhetoric,the Trésor taughtits noblereaders,fromAlfonsoXofCastile(1221–1284)toThomasofWoodstock, DukeofGloucester(1335–1397),howlivingwellandspeakingwellisboundupin ourrelationshiptothephysicalworld.

Likethe Trésor, LeLivredeSydrac (c.1280),whichdrawsfromboththe Trésor and L’Imagedumonde,was firstcompiledinFrenchfortheFrenchcourtandthen translatedintoItalian,aswellasintoCatalan,Dutch,Danish,German,and Englishoverthecourseofthenextcentury. Sydrac,ahugecollectionofentries aboutthephysicaluniverse,Christianbelief,andsocialbehavior,couchedasa philosophicaldialogue,survivesinproseandverseversions,aswellasinover fifty-threeFrenchmanuscriptsandclosetoonehundredtotalmanuscripts, includingeleveninMiddleDutchandeightinEnglish.²²Thistextisdiscussed indetailinChapter6.

Itmaynotbeacoincidencethatthesurgeofvernacularencyclopedismin thirteenth-centuryFrancehadacounterpartinoneofthemostinfluentialworks ofthirteenth-centuryArabicliterature, KitabAja’ibal-makhluqatwaGharaibalMawjudat (TheMarvelsofCreaturesandStrangeThingsExisting), firstcompiled inArabic c.1260bythePersianscholar,Zakarīyā ibnMu : hammadal-Qazwīnī (d. 1283),andlatertranslatedintoPersian.Al-Qazwīnī’sencyclopedia,ahierarchicallyarrangedmirrorofdivinecreationlikeThomasofCantimpré’ s Denatura rerum orBartholomaeusAnglicus’ s Deproprietatibusrerum,containssectionson zoology,angelology,cosmology,astrology,botany,and “ethnography,” thatis, fantasticalcreaturesandmonstrousraces,whichal-Qazwīnī callsJinn.²³Similarly, theMamlukencyclopedia, TheUltimateAmbitionoftheArtsofErudition, compiledaround1313bytheEgyptianadministratorShihabal-DinAhmadibn Abdal-WahhabalNuwayriandcopiedandcitedforseveralcenturiesafterwards, containssectionsonastronomy,geography,ethnography,animalclasses,pharmacology,andplants,butalso,andinwaysinwhichBrunettoLatiniwould appreciate,proverbs,artsofwriting,politicaltheory,andabriefhistoryofthe Mamlukstate.²⁴ Thirteenth-centuryMuslimandChristianencyclopedistsshared adesiretoorganizebroad-basedscientificinformation,andindoingsotransmitted fieldsofgeneralknowledgetonon-specialistaudiences.²⁵

²²Thetotalnumberofextantmanuscripts,whichsurelyexceedsthese figures,isdifficultto determine.SeeWeisel, “DieÜberlieferungdes LivredeSidrac, ” 53,forthenumberofsurviving Frenchmanuscripts.NotfewerthanseventeenFrencheditionswerepublishedbetween1486 and1537.

²³SeeZadeh, “TheWilesofCreation.”

²

⁴ SeeMuhanna, TheWorldinaBook,hiseditionandtranslationof TheUltimateAmbition ofthe ArtsofErudition,andhishelpfulsurveyofthirteenth-andfourteenth-centuryencyclopedism, “Why WastheFourteenthCenturyaCenturyofArabicEncyclopedism?” ForasurveyofMamlukencyclopediasandtheirtoolsforinformationretrieval,seevanBerkel, “OpeningUpaWorldofKnowledge.”

²⁵ SeeChapter6formorediscussionoftherelationshipbetweenMuslimandChristianencyclopedists.

ReturningnowtoJohnTrevisawecanseethathistranslationsofthreemajor compendiaparticipateinalargerEuropeantrendofcompilingandtranslatingbig informationalgenresintothevernacular,atrendstronglyidentifiedwithmedieval France.Thisbookarguesthattheyplayanimportantroleinshapingvernacular Englishliterature.Thecompendioustomesofinformationproducedinthelater MiddleAgesarenotliteraryintheconventionalsenseofreproducingfamiliar literaryforms,suchaslyric,dream-vision,orromance althoughtheyoften intersectwiththoseformsininterestingways.Andyet,theyteachusalesson aboutliteraryhistory,namely,thatourattachmentstothosetextswecallliterary, andwhichweinvestwithrichnessandcomplexity,haverootsinmedieval informationculture.Tobesure,incorporatinginformationaltextsintothestory ofliteraryEnglishmeansovercomingtraditionaldistinctionsbetweeninformationandliteratureandembracingthemedievalcompendium’speculiarviewof theuniverse.Trevisawillprovetobetheperfectentrypointintoaliteraryhistory ofinformation.

TheParisoftheWest

LikehiscontemporaryGeoffreyChaucer,Trevisa’slifeiswelldocumented. Importantly,hiscareerstraddledtwoinstitutionsofculture,theUniversityof OxfordandBerkeleyCastle.PossiblyoriginallyfromCornwall,hecanbetracedat Oxfordfromthe1360sthroughthe1380s, firstatExeterCollege(1362–1369), whichdrewstudentsfromDevonandCornwall,andthenatQueenshall(later Queen’sCollege),whereheprobablyreceivedanMAintheologyandlikelyknew thereformersJohnWyclifandNicholasHereford,bothQueenshallstudentsin the1370s.²⁶ AccordingtoJohnShirley(d.1456),ascribeintheserviceofThomas deBerkeley’sson-in-law,theEarlofWarwick,Trevisawasalsoadoctorin divinity.²⁷ AccordingtoDavidFowler’sstudyofcollegerecords,Trevisawasin residenceatQueen’sonandoffagainbetween1369and1385,thoughhisstatusas afellowiscertainonlyfortheyears1369–1374;hewasexpelledfromQueen’ s afterariotalongwithothersouthernersin1378–1379(seeChapter3)andwas againpayingincidentalexpensesandrentfromtheperiod1385–1387.Itis temptingtothinkthatthislatterperiodwasformativetoTrevisa’stranslationof the Polychronicon:Trevisadatedaglossinhistranslationofthe Polychronicon,a glossnotablyconcerningrecentchangesinthelanguagesofinstruction,to1385, laterdedicatinghistranslationtoThomasdeBerkeleyin1387.Trevisaappearsto haverentedroomsatQueenshallonceagainduringtheperiod1394–1396,dates

²⁶ SeeChapter3,pp.176–77.

²⁷ ForShirley’sconnectionstoBerkeley,seeConnolly, JohnShirley,114–16.

perhapssignificanttothescholarlyactivitythatallowedhimtocompletehis translationof Deproprietatibusrerum,whichhededicatedtoBerkeleyin1398.²⁸

ThomasdeBerkeley’spatronagefurtherlocatesTrevisainBerkeleyCastle, Gloucestershire,thebaronialseatandhometoasmallcoterieofscholarsand translators.EcclesiasticalandcastlerecordsdocumentTrevisa’sclericalappointmentsaschaplaintoThomas,ascanonofthecollegiatechurchofWestburyfrom whichhewouldhavereceivedastipend,andasvicaroftheparishchurchofSt. Mary’sBerkeleyuntil1402,when,presumably,hedied.TheBerkeleyparish churchbelongedtoSt.Augustine’sAbbey,Bristol,nowBristolCathedral,whose financeswereoverseenbythebaronsofBerkeley.²⁹ Itseemsreasonabletosuppose thatThomasdeBerkeleyunderwroteTrevisa’sstudiesatOxfordinthe1380sand 1390s,inadditiontosponsoringhisappointmentsinGloucestershire,andthathe hadavestedinterestinTrevisa’stranslations.Unlikemodernstudents,who usuallyearnadegreetogetajob,mostmedievalstudentsattendeduniversity untiltheysecuredaposition,asTrevisamayhavedonearound1374 the positionwasthegoalratherthanthedegree.Itwasnotuncommon,however, forscholarstocontinuerentingroomsinacollegeperiodicallybutinamore distinguishedcapacity,asTrevisamayhavedoneinthemid-1380sand1390s.

Trevisa’soeuvreconsistedofEnglishtranslationsofLatinworks,nearlyallof whichcouldbeclassifiedas “informationforlaylords,” aclassi ficationsuggested byTrevisahimselfandborneoutbytheearlymanuscripttransmissionofhis works.³⁰ ThiscorpusoftranslatedLatinsuggestsanongoingtransactionbetween universitylearningandthelayaristocratichousehold.AsHannapersuasively argues,thereissomeevidenceforagreathousearistocraticcoterie,which includedaprovincialmagnate,Berkeley,hisdaughterElizabeth,andhisson-inlaw,theEarlofWarwick,butalso,possibly,Thomas’sstep-grandmother, KatharinedeBerkeley,who,in1384,foundedagrammarschoolforamaster andtwo “poorscholars” atWotton-under-Edge,themarkettownforBerkeley.³¹ Sometimearound1422–1423,thescribeJohnShirleydrewupaversifiedtableof contentstoBritishLibrary,AdditionalMS16165,animportantanthologycontainingpoetrybyChaucerandJohnLydgate.³²ThereShirleyattributesaprose

²⁸ Fowler, LifeandTimes,29–30,85,112–13.

²⁹ Trevisa’sliferecordsareexhaustivelyanalyzedbyFowler, LifeandTimes,chapter3.

³⁰ SeeSomerset, ClericalDiscourseandLayAudience,chapter3.

³¹I.e.,KatharineLadyBerkeley’sSchool,oneoftheoldestsurvivingschoolsinEngland:https:// www.klbschool.org.uk/about/history-of-klb/.Thetranscriptofthefoundationdeedcanbefoundhere: https://archive.org/details/educationalchart00leacuoft/page/330.Thedeedstipulatesthatthemasterof theschoolprayforthesoulsofKatharine,ThomasdeBerkeleyandhiswifeLadyMargaret,SirJames deBerkeleyandhiswifeElizabeth,andKatharine’stwodeadhusbands,ThomasIIIandSirPeterVele. SeeHanna, “SirThomasBerkeley,” 102.SeealsoOrme, “EducationinMedievalBristoland Gloucestershire.”

³²SeeHanna, “JohnShirley” andEdwards, “JohnShirley,JohnLydgate,andtheMotivesof Compilation.”

item,theMiddleEnglish GospelofNicodemus,toJohnTrevisa.³³Accordingto Shirley,BerkeleygraciouslyarrangedfortheworktobetranslatedbyTrevisa, “ a clerkforthemaystrye.” Shirley’sunctuouspraiseofbothpatronandtranslator “

ThankethelordandtheClerk/Thatcaused firstthatholywerk”—issurelya referencetoTrevisa’sprefacetothe Polychronicon,the “DialoguebetweenaLord andaClerk,” inwhichalordandaclerkdebatethelegitimacyofEnglish translation.³⁴ WeknowthatShirleywasconnectedtotheBerkeleyfamilythrough hisemployer,theEarlofWarwick,RicharddeBeauchamp,husbandofBerkeley’ s daughter,theCountessElizabeth,whowasherselfthededicateeofJohnWalton’ s versetranslationofBoethius’ s Deconsolationephilosophiae (1410).³ ⁵

Iftwootherpossibletranslatorsarefactoredin,thetranslatoroftheshort apocalyptichistoryattributedtoMethodius,whichwascompiledinTrevisamanuscriptsbutwhich,onstylisticgrounds,wasunlikelytohavebeenwrittenby Trevisa,andthetranslatorofVegetius’ s Deremilitari (1408),compiledwith Trevisa’stranslationof Deregimineprincipum inMSDigby233,³⁶ thefaintoutlines emergeofasmallliterarycenterinGloucestershire,operatingbetween1385and 1410.³⁷ ThroughTrevisa,thiscenterhadtiestoOxford,andpossiblytoacoterieof scholarsworkingonbiblicaltranslation,andthroughtheBerkeleyfamily,toBristol institutions,suchasSt.Augustine’sAbbey,andSt.MaryMagdalene’shospital,to whichThomasdeBerkeleybequeathedaRichardRolleGlossedPsalter(BodleyMS 953),³⁸ andtoLondon,wheretheBerkeleyfamilyhadcommercialandresidential interests.InLondon,andlikelythroughBerkeley’sdirectoffices,Trevisamanuscripts cameintocontactwithprominentLondonscribessuchasscribeD,whoproduced BritishLibrary,AdditionalMS27944(Deproprietatibusrerum),³⁹ andscribeDelta,

³³Connolly, JohnShirley,chapter2.SeeChapter3belowforadiscussionofthistext.

³⁴ GiveninFowler, LifeandTimes,32.

³⁵ TenmanuscriptsofWalton’ s ConsolationofPhilosophy survive.HannasuggeststhatShirleyspent timeinWotton-under-Edge,themarkettownnearBerkeleyCastle,andtheburialplaceofThomasde Berkeley;perhapshewasdealingwiththedeadcountess’sfraughtinheritanceinGloucestershire.One Trevisamanuscript,HuntingtonLibraryHM28561,whichcontainsthesolesurvivingtextoftheMiddle English Turpin’sChronicle,maypointtotheafterlivesofBerkeleyliterarypatronage.StephenShepherd hasidentifiedtheowner,whomightormightnothavebeenthecommissionerofthetranslation,as ThomasMull(c.1400–1460)fromHarescomb,Gloucestershire,situatedjust11milesfromBerkeley.Mull probablyknew,ifnotThomasdeBerkeleythensurelyhisnephewandheirJames(d.1462).SeeShepherd’ s excellentintroductiontohiseditionof TurpinesStory,xviii–xxv.

³

⁶ HannasuggeststhatWilliamClifton,masterofthegrammarschoolatWottonin1416,is responsiblefortheVegetiustranslation(“SirThomasBerkeley,” 891ff.,esp.900–901).Muchofthis discussionisowedtoHanna’scogentanalysis.

³

⁷ Hannaarguesthat,thoughTrevisawasthestar,helived “atthecenterofa floatingclerical community” (“SirThomasBerkeley,” 893).Green,in PoetsandPrincepleasers,154–55,paintsasmaller picture.

³

⁸ Hanna, “SirThomasBerkeley,” 883;Doyle, “EnglishBooks”;Kuczynski, “ThePsalms,” 198. AccordingtoBriggsetal.,Bodley953sharesdecorativefeatureswithDigby233,bothproducedina BerkeleyscriptoriumorBristolatelier(Governance,xii).

³

⁹ AccordingtoHanna,MorganMSM.875(Deproprietatibusrerum)(1400–1410),andColumbia UniversityLibrary,PlimptonMS263(c.1440)werederivedfromthesameexemplarusedbythescribe ofBritishLibraryAdditionalMS27944.PlimptonservedasWynkyndeWorde’scopytext(Hanna, “Sir ThomasBerkeley,” 910).

whoproducedseveralcopiesofTrevisa’stranslationofthe Polychronicon:British Library,AdditionalMS24194,St.John’sCollege,Cambridge,MSH.1,andpossibly PrincetonUniversityLibrary,Garrett151.IfHannaiscorrect,Berkeleybroughta Gloucestershireexemplarofthe Polychronicon,Chetham’sLibraryMS11379 (1390–1415)toLondon.⁴⁰ Significantly,oneofscribeDelta’scopiesofthisexemplar, BritishLibrary,AdditionalMS24194,whichsharesmissingtextswithChetham’ s, belongedtoRicharddeBeauchamp(d.1439),EarlofWarwick,Berkeley’sson-inlaw,andwaslikelyproducedespeciallyforhim.ByThomasdeBerkeley’sdeathin 1417,however,thisliterarycenterinGloucestershirehadlostitsmomentum,and althoughTrevisa’stranslationscontinuedtobecopiedandevengivennewlivesin print,BerkeleyCastlecametoberememberedasthesiteofEdwardII’sgrislydeath in1327,ratherthanofvernacularliteraryproduction.

AlthoughtheBerkeley–Trevisacollaborationmaynothaveamountedtoso muchasa “courtofletters,” neverthelessitclearlyaimedtoemulatetheachievementsoftheFrenchcourtofCharlesV(reigned1364–1380).⁴¹In1345thegreat bookcollectorandBishopofDurhamRichardofBuryproclaimedthat,though theParisbookmarketwasstillpreeminent,themantleof(Latin)eruditionwas beingpassedfromParistoBritain.Burywasclearlybiasedinhisassessment, channelingsomeoftheburgeoningnationalismofEngland’swarwithFrance.⁴² CharlesV’sreign,whichwitnessedanexplosionofvernacularscholarship,would provejusthowwrongthispredictionwas.Fromthelatethirteenthcentury, beginningwiththeFrenchtranslationsofGilesofRome’ s Deregimineprincipum (translatedbyHenrideGauchyin1282,theoriginalLatincompilationdedicated byGilestoPhilipIV, c.1279),andVegetius ’ s Deremilitari (latefourthcentury), whichwastranslatedbyJeandeMeunfortheCountdeEuin1284andretranslatedbyJeandeVignayforPhilipVIandJeannedeBourgognein c.1320,⁴³the Frenchcourthadcommissionedtranslationsandglossesoftextsoncetheprovenanceofscholarsbutnowincreasinglyadaptedtotheinterestsofthegoverning classesandcopiedintodeluxemanuscriptsforwealthylaybookowners.This royalinitiativewasanticipatedbythirteenth-centuryvernaculartranslationsand compilationsofthenaturalencyclopediasdiscussedabove,suchas L’Imagedu monde (c.1240),the Trésor (c.1260),and Sydrac (c.1280s–1290s).

CharlesV’spatronage,however,tookvernacularbookproductiontoanew level.WhatDeborahMcGradyhaslabeledCharles’ s “sapientia project” consisted ofseventeenwriters,fourteentranslators,andthirty-fivenewworkscommissionedordedicatedtothemonarch, ⁴⁴ inadditiontoahugeproductionstaff laboring “toharmonizetherulingclass’sviewofbooksasexpressionsofpower

⁴⁰ Hanna, “SirThomasBerkeley.”

⁴¹MuchofthematerialistakenfromSteiner, “BerkeleyCastle.”

⁴² Philobiblon trans.Thomas,chapter9.

⁴³Briggs, GilesofRome,81–89;Green, PoetsandPrincepleasers,153–54.

⁴⁴ McGrady, TheWriter’sGift,9.

andprestigewiththeintellectualidealsoftextsassourcesofknowledgeand truth.”⁴⁵ CharlessponsoredtranslationsofthemoralworksofAristotle(trans. NicoleOresme,1370s),Augustine’ s DecivitateDei (translatedbyRaouldePresles, c.1371–1375),BartholomaeusAnglicus’snaturalencyclopedia, Deproprietatibus rerum (translatedbyJeanCorbechon,1372),JohnofSalisbury’ s Policraticus (translatedbyDenisFoullechat, c.1372),and LeSongeduvergier (“TheDreamof theOrchard”),adebatebetweenaknightandaclerkabouttemporalsovereignty, translatedfromtheLatinin1378byÉvrartdeTrémaugonorPhilippedeMézières anddedicatedtoCharlesV.OthertextsproducedintheFrenchcourtinthis periodincludevarioushistories,suchas LesGrandeschroniquesdeFrance, commissionedbyPhilipofValoisbutupdatedandsumptuouslyillustratedfor CharlesV, LeMiroirhistorial (before1332),Vignay’stranslationofVincentof Beauvais’ s Speculumhistoriale,luxuriouslyreconceivedforCharlesVandforhis uncle,therenownedbibliophileJean,DukeofBerry,⁴⁶ andtheexpandedversion ofthe Biblehistoriale (firstadaptedbyGuyartdesMoulinsintoFrenchfromPeter Comestor’smassivelyinfluential Historiascholastica, c.1169–1173).⁴⁷

Charles’scommissionsshowedthatacademictextscouldsatisfytheintellectual ambitionsofagreatlord,andthatinformationalprosewasworththeeffortto translateintothevernacularandcopyintosumptuousmanuscripts. ⁴⁸ Agenerationlater,Trevisa’stranslations,intendedforThomasdeBerkeley, invoketherangeoftextstranslatedfortheFrenchcourt:GilesofRome’ s mirror-for-princes,BartholomaeusAnglicus’snaturalencyclopedia,anational historyonauniversalscale(i.e., Polychronicon vs. LesGrandeschroniques and the Biblehistoriale),andadialoguebetweenaknightandaclerkabouttemporal sovereignty(Dialogusinterclericumetmilitem vs. LeSongeduvergier,bothtexts derivedfromOckhamandwellknownoneithersideoftheChannel).

NotonlydidtheTrevisa–BerkeleyprojectreproduceregionallyandinminiaturethetranslationprojectofCharlesV’scourt,italsoreliedonthetextsand manuscriptsthatemanatedfromParis.TranslatingprimarilyfromtheLatin, TrevisaclearlyhadrecoursetoFrenchversionsofGilesofRomeand BartholomaeusAnglicus.TheFrenchtranslationofGiles’ s Deregimineprincipum survivesinforty-twomanuscriptsinsevenversions,themostfamousversion beingthatofHenrideGauchy,copiesofwhichwereownedbynobilityandrich burgessesinEngland(sixoutofthirty-oneextentmanuscriptsofHenri’stranslationhaveanEnglishprovenance).⁴⁹ AFrenchmanuscript,nowlost,wasowned

⁴⁵ Ibid.,24. ⁴⁶ BnFMSNAF15944.

⁴⁷ SeeHedeman, TheRoyalImage,chapter5,andLobrichon, “TheStoryofaSuccess.”

⁴⁸ ThisdiscussionofFrenchcourttranslationstakesitsinspirationfromMinnis, “Ispekeoffolk” and “AbsentGlosses.”

⁴⁹ SeePerret, Lestraductionesfrançaises,xvii.AccordingtoPerret,allthegreatbibliophilesofthe Frenchcourtwantedcopiesofthistext:PhiliptheBold,DukeofBurgundy,paidforoneinJanuary 1402(Brussels,KBRMS9094);Jean,DukeofBerrywasgivenacopyforNewYear1404(Chantilly, MuséeCondé,MS339)andpurchasedanotherin1416(Rheims,BMMS993);CharlesVI’ssonand

in1388bySimondeBurley,tutortothefutureRichardIIandLordWardenofthe CinquePortsandConstableofDoverCastlebetween1384and1388.⁵⁰ Inthe fifteenthcentury,PierpontMorganLibrary,MS122(France,1300–1325)belonged toaCalaismannamedWilliamSonnyng,whomarkeditupwithoveronehundred Englishnotes.⁵¹AsJoyceColemanhasdiscovered,theillustratorresponsiblefor DigbyMS233(c.1410),thesinglewitnesstoTrevisa’stranslationof Deregimine principum,lookedtoFrenchmanuscriptsoftheFrenchtranslationofthattext.⁵²

Mosttellingly,perhaps,the “defective” readingsinTrevisa’stranslationof De regimineprincipum,readingswhichitsmoderneditorsattributetoanunknown Latinexemplar,canbetracedbacktoGauchy’sFrenchtranslation,acopyof whichTrevisausedintandemwiththeLatin,orperhapsasinthecaseofthe DigbyMS233illustrator,asamodel.Forexample,in Deregimineprincipum, BookI,partII,chapterXI,inadiscussionofdistributivevs.commutativejustice (followingThomasAquinas),Trevisainsertsthefollowinganalogyborrowed fromHenrideGauchythat,justasthesoulmaintainsthebody forwithout thesoul,thebodywouldwasteaway sojusticemaintainstowns,cities,and realms: “andasthesouleconteyneththebody,fortherwithoutethebodyisdissolued andshrynketh,soiusticiacontenynethtownes,thatisciteesandregnes,for therwithoutenociteneregnemaystonde.” Inthispassage,Trevisaglossesthe LatintextbyincorporatingapassageliftedfromtheFrenchtranslation: “etaussi commel’ametientlecorsenvie,etquantl’amesedepartlecorsmoertetseche,tout aussijusticeetdroituresoustient lescitezetlesreaumescarsaunziusticenepuent lerealmedurer” (myemphases).⁵³

LikeGilesofRome’ s Deregimineprincipum,BartholomaeusAnglicus’ s De proprietatibusrerum,translatedin1372forCharlesVbyJeanCorbechonas Le Livredespropriétésdeschoses,wasenthusiasticallyreceivedbytheEnglishand Frencharistocracyandwastreatedtorichprogramsofillustration.⁵⁴ Trevisaused thisversionoccasionallyasacrib.Forexample,inthesectiononfeet(5.54 “De pede”),⁵⁵ Bartholomaeusexplainsthatyoucantellthesexofafetusbythegaitof themother:pregnantwomenextendtheirrightleg firstiftheyarehavingaboy (Latin: “compositispedibus”;French “lespiesiointez”;Trevisa, “jointespee”). Interestingly,too,aglossintheEnglish Deproprietatibusrerum (I.9),whichin manuscriptisattributedtoTrevisaashisoriginalcontribution(“Trevisa heir,LouisDukeofGuyenne,seizedJeandeMontaigu’scopyin1409(BritishLibrary,AdditionalMS 11612).

⁵⁰ Scattergood, “TwoMedievalBookLists.”

⁵¹SeeNall, ReadingandWar,33–35,andBoffey, “BooksandReaders.”

⁵²Coleman, “FirstPresentationMiniature.”

⁵³TheEnglishtranslationisquotedfromBriggsetal.,eds., Governance,60.TheFrenchistaken fromMolenaer,ed., Lilivresdugouvernementdesrois,47.

⁵⁴ Ofthe45survivingCorbechonmanuscripts,33areillustrated.Oneofthemostsplendid,British Library,RoyalMS15EIII,wasprobablymadeforEdwardIVinEngland.Ontheillustrations,seeVan denAbeele, “Illustrerle Livredespropriétésdeschoses ”

⁵⁵ QuotedfromSeymour,ed., OnthePropertiesofThings.

exemplum”),actuallycomesfromJeanCorbechon’sFrenchglossontheLatin (perhapsultimatelyfromaLatingloss).Bartholomaeusexplainsthatthereare threekindsofnouns:concrete,abstract,andmiddle.Themiddlenounshavethe mannerandformofabstractnounsbuttheuseandofficeofconcretenouns.Thus youmightcallGod “theLight” or “Light” butyouwouldbestillbereferringto someoneinparticular.Trevisa’sgloss,translatedandexpandedfromCorbechon’ s French,offerstheTrinityasanillustrationofsuch “middle ” nouns: “Trevisa exemplum:thefadirandsoneandholygoostbethonlightandnoughtmany lightis,wisdomandnoughtmanywisdoms” [“Etcommenousdisonsquelepere estsapience,le filsestsapience,etlesaintesperitestsapience.Etcestrois personnesensemblesontunesapienceetnonpaspluseurssapiences”].⁵⁶

Inseveralofhistranslations,moreover,Trevisaadvertiseshimselfasanexpert onFrenchlanguageandculture.Take,forexample,hisfamouscommentabout thediversityofdialectsinFranceinhistranslationofHigden’ s Polychronicon Higdenthinksitagreatwonder(mirandumvidetur)thatEnglishinitsnative EnglandissodiversebuttheFrenchofEngland,aNormanimport,issounified, spokensimilarlybyall.TrevisacommentsthatFrenchinFranceisasdiverseas EnglishisinEngland: “NeverthelesthereisasmanydyversmanereFrenschein thereemofFraunceasindyversmanereEnglischeinthereemofEngelond” (I.59). ⁵⁷ Inthe Polychronicon,HigdenrecordsthatJuliusCaesarfoughtrepeatedly againsttheGermansandtheGauls.TrevisainterruptstoexplainthattheGauls arefromGaul,aregionwhichisborderedbythreebodiesofwater,andwhichis oftenmistakenlyidentifiedwithFrancewheninfactitcontainscontemporary Francealongwithothercountries:

TheyghGalliaandFrauncebeoftei-countedalleoonlondeandcontray,notheles aswespekethcomounlicheofFraunceandnowhereofGallia.Galliaconteyneth althereameofFraunceandmenyothercontrayesandlondesanonetotheRyne northward,totheRoonestward,totheseeofBritayneandofEngelonde westward.(3.40)

HigdentellsaversionofastoryaboutastandoffbetweenPopeLeotheGreatand BishopHilaryofArles(fifthcentury)concerningdiocesanauthorityinFrancia. Thepope,accostingHilary,asks, “Areyounotagallus(acock)andthesonofa gallina(ahen)?” Hilaryanswersthatheisindeedagallus(Frenchman)butnota gallus(cock).Leoboasts, “youareHilaryfromGaul,andIamLeo,theapostolic

⁵⁶ TranscribedfromBnFMSFr.135,f.36v.Latintext: “Itaenimlicitabstractivesuntaliquando supponuntpropersonisvtcumdiciturlumendelumine.Sapientiadesapientiaprincipiumde principioetsimilia.Ethecnominaabstractapredicantursicutdequalibetpersonaperseetdeomnibus simulnonpluralitersedsingulariter.”

⁵⁷ Quotationsfromthe Polychronicon aretakenfromBabingtonandLumby’sedition,citedbybook andchapternumbers.Medievalletterformsaresilentlymodernizedthroughout.

bishopandjudgeoftheseeofRome.” Hilarygetsthelastword, “YouareLeobut notaleo(i.e.,alion)ofJudah, ” ananswerthatenragesthepope.Trevisastepsup toparsethisLatinjoke,whichapparently,fornon-Latinatereaders,requiressome knowledgeofFrenchculturetounderstand: “Gallusisacok,andGallusisa Frenscheman;thennehementthatHillaryewasafrenssheman,whan,heseide, ‘ThouartGallusandnoghtgallina, ’ HismenyngewasthatHillarywasaFrensche manandnoughtacok” (4.27).

IfTrevisa’scollaborationswithThomasdeBerkeleysoughttoimitatethe Frenchcourtofthe1360sand1370s,theyalsoraisedthepossibilitythatEnglish literaturewouldrevolvearoundaregionalbaronialpowerratherthanacitylike LondonorParisoraroyalcourtsuchasRichardII’s.HadLondonhada universityinthefourteenthcentury,perhapsacourtofletterswouldhavebeen locatedthere.IfRichardIIhadprovedalittlemoreinterestedinliterature,Trevisa mighthavesurfacedinroyalcircles,ratherthanatabaronialseatintheWest Country.⁵⁸ ButtheEnglishking,anoccasionalpatronofthearts,wasnoselfstyledscholarlikeCharlesV,whowasoftenportrayedasascholar-clerk,asin JeanBondol’ s flatteringportraitofhimwearingagrayteacher’scloak,receivinga Biblehistoriale fromhisclerk,JeanVaudetar(c.1372).⁵⁹ Thebookdepictedwithin theportraitiswritteninFrench,mirroringtheking’sauthorityinthe firstlineof Genesis: “Aucommencement,Dieucréalescieuxetlaterre.”⁶⁰

ThebooksproducedforthecourtsofCharlesVandVIareamongthemost splendidofthelaterMiddleAges,andthebookindustryofTrevisa’sEngland couldnotcompete.WewouldnotexpectTrevisamanuscriptstoapproachthe decorativesplendorofthebooksdesignedfortheFrenchcourt,someofwhich endedupin fifteenth-centuryEnglishcollections,suchascopiesofJean Corbechon’stranslationof Deproprietatibusrerum,andyettheydoshowa concertedefforttoturnoutluxuryvolumesworthyofrecipientswillingand abletostepintotheroleofroyalpatron.OftheapproximatelythirtyTrevisa manuscriptswhichsurvive,nearlyallaredeluxeheavyvolumes,theeffortand expenseofwhichsuggestseveralcommissioningpatrons.Manyofthemfeature decorativebordersandilluminatedcapitals,oneofthemostspectacularofwhich isthecopyofthe Polychronicon inBritishLibrary,StoweMS65(Figure1.4).⁶¹

⁵⁸ OnRichardII’sliteraryandartisticpatronage,seeBarr, SocioliteraryPractice,chapters3and4, andBennett, “TheCourtofRichardII.”

⁵⁹ BibleofJeandeVaudetar,MuseumMeermanno-Westreenianum,MS10B23,f.2.SeeSherman’ s discussionondedicationfrontispiecesin ImaginingAristotle,chapter5.

⁶⁰ AsColemanpointsoutaboutthemanyteachingscenesthataccompaniedtranslationsintended fortheFrenchmonarch,andinparticular,thosefoundinillustrationsof LeLivredespropriétésdes choses,thesewere “aconsciousattempttobridgethetextfromitsacademictonewlayaudience” (Coleman, “MemoryandtheIlluminatedPedagogyofthe Propriétésdeschoses, ” 31).SeealsoBoudet, “Lemodèleduroisage.”

⁶¹CCCCMS354,acopyofTrevisa’stranslationofthe Polychronicon (c.1500),isanexception.

Figure1.5 RanulphHigden, Polycronicon,tr.JohnTrevisa.Cambridge,St.John’ s CollegeLibrary,H.1,f.80v(c.1400–1425).ReproducedwithpermissionofSt.John’ s CollegeLibrary.

Thecopyofthe Polychronicon inBritishLibrary,AdditionalMS24194,as mentionedabove,waslikelycommissionedforitsowner,theEarlofWarwick (d.1439).ThebeautifullydecoratedPlimptoncopyofTrevisa’stranslationof De proprietatibusrerum,whichweighsoverthirtypounds,andwhichsupplied WynkyndeWordewithhiscopytextforthe firstprintededition,wasownedby SirThomasChaworth(d.1459),SheriffofNottinghamshireandDerbyshire.⁶² UnlikethemanuscriptsproducedforroyalandducalcourtsinFrance,Trevisa manuscriptstendtobesparselyillustrated,butnotableexceptionsincludethe finelyexecuteddiagramsofNoah’sark,whichsignificantlyimproveuponcorrespondingexamplesinLatin Polychronicon manuscripts(seeFigure1.5),⁶³andthe lovelyminiaturesforthe Dialogusintermilitemetclericum insistermanuscripts BritishLibrary,Additional24194andSt.John’sCollegeMSH1,depictinga

⁶²Fordetaileddiscussionsofthistextanditsmanuscripts,seeChapters5and7.

⁶³FoundinBritishLibrary,Additional24194,St.John’sCollegeH.1,AberdeenMS21,Princeton TaylorMS6,andSenshuUniversityLibrary,MS1.