JOURNAL OF ARCHITECTURE

(SUPER)NATURAL DATUM NO. 14

ABOUT US:

DATUM (SUPER)Natural is a journal of A/architecture founded and edited by students at Iowa State University.

The publications seeks to manifest and catalogue DATUM’s community of discussion and act as a platform for further inquiry and critique. It is organized around a central theme that DATUM feels has been misrepresented, neglected, or needs further examinations.

DATUM would like to thank Iowa State University Department of Architecture for their continuous support and invigorating enthusiasm for the journal and community.

datumcollective.org / instagram: datum_isu

|Nat· u· ral| , [adj]

• existing in or caused by nature; not made or caused by humankind.

• being in accordance with or determined by nature.

Natural commonly refers to things that exist in nature rather than being created or altered by humans. It encompasses phenomena, substances, processes, or characteristics that occur organically and spontaneously

without artificial intervention. Commonly accepted natural elements include plants, animals, minerals, landscapes, weather patterns, and biological processes.

SUPERNATURAL

|Su·per· nat· u· ral| , [adj]

• (of a manifestation or event) attributed to some force beyond scientific understanding or the laws of nature.

• of or relating to an order of existence beyond the visible observable universe.

In traditional understandings, supernatural refers to phenomena, entities, or forces that operate beyond the scope of natural

These concepts typically defy explanation by conventional scientific methods or imperial evidence.

(SUPER)NATURAL

DATUM is particularly interested in investigating the ways in which the intersections between humans and the natural environment create supernatural conditions. In modern society, technology, industry, and urbanization have led to significant transformations of natural landscapes and processes. Negative externalities including pollution, deforestation, and climate change are examples of humaninduced changes that affect the natural world. These human interventions require us to consider whether there is anything left that has not been imposed on by humans?

In architecture, nature is represented as as a form of abstraction; curved lines, naturally occurring patterns superimposed on materials of steel, glass, and concrete begin to

transform our expectation of organic ecology. Our current systems and infrastructures continually seek to legitimize and naturalize these concepts, deflecting nature to reflect ideal beliefs that money and power can regulate nature. Ultimately, the concept of “natural” is a human construct and subjective dependent on one’s perspective. Some contend that nothing remains untouched by human influence and thus there is no more “natural” land, while others believe that human intervention is an integral part of the natural world. As designers and stewards of the built environment, these concepts begin to challenge our understanding of ecological, material, and cultural value as we continue advocating for more sustainable and ecologically responsible infrastructures.

* It is important to note that the difference between natural and supernatural can be subjective and culturally influenced. Different belief systems, cultures, and religions may have varying interpretations of what is considered natural or supernatural. Ultimately, the definitions and implications of these terms can vary.

REMAINING MARKS Izzy Witten CAPITALISM: THE (SUPER) NATURAL CONDITION Nick Cheung A ROOM WITH A BETTER VIEW Meredith Petellin PALESTINE RALLY AFTER HOURS Griffin Lilly 38 40 32 28 24 16 12 (SUPER)NATURAL NATURE Sierra Wroolie NEIGHBORS Arden Stapella

INTERVIEW WITH Joshua Stein

44

SILENCED VOICES

PRESERVATION & SUSTAINABILITY

OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

Tim Zhang

Amani Taleb THIS DESIGN IS VERY HUMAN

Aidan Andrews

INTERVIEW WITH Aaron Betsky

WHAT’S IN A NATURE?

Finn Digman

MIDWEST MONUMENTS

Connor Shanahan & Daniel Leira BEFORE THE BOMBS CAME

Sophi Allen

54

60

66

70

78

84

90

REMAINING MARKS

Izzy Witten

It is a common thought that leaving your mark on the world is the way to solidify your experience or impact as a human.

It is an idea that is seemingly born with us, whether large or small, an impulse that drives us. But why do we have this desire? What is the reasoning behind a seemingly frivolous pursuit? What are the ways that it manifests itself in the world around us?

Imagine a packed cityscape, such as New York or Chicago. Places such as those are often a hub of human activity, a melting pot of human experience and emotion. Appropriately, there is an abundance of art expressing the masses. I’m talking about Graffiti.

12 | DATUM

“ “

The very concept of leaving our mark in the world carries a special power; it encourages us to reflect on and solidify the impact that we are leaving in our wake alongside each other, feeding into the desire to be part of something larger.

Marking our names or symbols in places as we pass through them solidifies our abstract experience of life. Linking the eternal concept of human experience to a tangible sign of its passing. Leaving our mark provides us with a chance to bridge the two - our tangible, concrete world and the oftenintangible nature of our lives. Our mark, then, stands as a powerful reminder of our life in a fleeting, transient world. The mark is an embodiment of the impermanence of a personal human experience combined with the permanence of a mark. Whether it is a simple primal instinct or some deeper,

universal pull, I can only provide my insight. There are no reasonably explainable answers as to why exactly we long to mark the world around us, only speculations on the collective human behavior and a (super) natural instinct. It’s something we all possess: the ability to find something within us to leave behind in the world and make an imprint. The idea of leaving our mark is an idea that speaks to the very essence of being human.

(Super)Natural | 13

CAPITALISM: THE (SUPER)NATURAL CONDITION

Nick Cheung

There has not been a force as impactful on our planet as humans. During that time, humans have developed a parasitic relationship with nature, extracting its resources to advance. In the modern globalized world, humanity has continually created (super)natural conditions that impose our will on the natural ecology and one another. Capitalism is perceivably the most dominant of them all: A supernatural force corroding our natural order and environment.

“

MODERN MAN DOES NOT EXPERIENCE HIMSELF AS A PART OF NATURE BUT AS AN OUTSIDE FORCE DESTINED TO DOMINATE AND CONQUER IT.

16 | DATUM

- E.F Schumacher, Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered.

NATURE’S FINITE RESOURCES:

Capitalism is arguably the main cause of the climate crisis, imposing negative externalities on countless species and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. It relies on production and consumption, exacerbating environmental issues in pursuit of economic growth and wealth accumulation. Its impact comes through the facilitated exploitation of nature by excessive depletion and destruction of biodiversity, as well as irresponsible care of the natural ecology. Competition and commodification exacerbate the irrationality of supernatural market forces driven by profitability rather than human well-being and ecological considerations. Capitalism enforces unsustainable social norms detrimental to the

environment that are apparent in countless aspects of modern life, including our modes of transportation, places we live, things we buy, and foods we eat. This is visible through excessive food production, waste, and fast fashion, a capitalistic enterprise that accounts for “20% of global wastewater and 10% of global carbon emissions” (Waugh). With no market mechanisms incentivizing environmental preservation, we fall prey to overproduction and overconsumption. Given Earth’s finite natural resources and capitalism’s reliance on consistent growth, we are approaching an unsustainable threshold where we will completely exhaust and deplete our resources.

HOW CAN WE PROMOTE SYSTEMS THAT ENABLE MORE EQUITABLE LIVING FOR HUMANS AND THE ENVIRONMENT?

(Super)Natural | 17

ENGINEERED SOCIAL STRATIFICATION:

Capitalism also enables the consolidation of social status through wealth accumulation, facilitating extreme discrepancies in human flourishing. This becomes a perpetual cycle fueled by human greed and capitalist constructs of production and consumption. By allocating opportunities through generational wealth, capitalism builds on inherited inequalities of class, ethnicity, and gender. Wealth is concentrated in the upper echelon, leaving the remaining citizens with depleted resources and opportunities.

A study conducted between twenty-three developed nations and various states of the United States observed: “negative

FORM, FUNCTION AND EXPLOITATION:

will exist perpetually.

Capitalism’s supernatural presence is also felt in architecture, where it is exploited and commodified as a product and a process. Capitalism ensnares us in its profit-driven motive, evaluating designers in hours and productivity. This is exacerbated in education as it is unwilling to distance itself from the capitalistic paradigm embedded in academia. While our universities pride themselves on creating designers with nuanced

correlations between inequality and physical health, mental health, education, child wellbeing, social mobility, trust, and community life” (Hodgson). This creates adverse and inequitable outcomes for most of society that last for generations. As capitalism becomes more knowledgeintensive and education becomes more certification-based, the result is an unskilled and lowpaid working class. We are willing to gain selfishly at the detriment of others, enabling capitalism to become a supernatural force that predetermines and dictates our place in a rigid social hierarchy. Unless robust social welfare programs are enacted to ensure a more equitable society, inequality

understandings of form, style, and aesthetics, they suppress more progressive conversations on how architecture could facilitate more equitable collective ownership. Thus, architecture is reduced to the confines of what is socially acceptable and practical, limiting possibilities of how people inhabit places. This puts designers in an environment to justify their services and value, magnifying competition and the degree to which they can be exploited

18 | DATUM

(Super)Natural | 19

20 | DATUM

EDUCATION’S CURRENT FRAMEWORK IS SEVERELY LIMITED, INDOCTRINATING US WITH PRE-EXISTING IDEAS, PREJUDICES, AND BACKGROUND THEORIES TO A SITUATION, INSTEAD OF TRULY THINKING FOR OURSELVES.

- E.F Schumacher, Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered.

“

(Super)Natural | 21

“

THE PROBLEM COMES DOWN TO OUR NATURES - WE ARE GREEDY AND ENVIOUS AND STOP AT NOTHING TO ENSURE OUR MATERIALISTIC GROWTH. OUR DESIRES ARE AT ODDS WITH OUR FINITE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT. IT’S ON US TO FIND A NEW SYSTEM THAT SUPPORTS OUR ENVIRONMENT BEFORE WE DESTROY IT. CAPITALISM WILL, EVENTUALLY, RUIN US. “ “

socially and financially. Furthermore, a premium is placed on pristine visuals that prioritize spectacle over experience. This streamlines production and consumption as students scramble to complete drawings to satisfy

deliverables rather than allocate time to develop projects thoroughly. This is mirrored in practice as buildings are standardized and projects and “value engineered” to maximize the most profit from their projects.

STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS:

Capitalism’s core production and consumption components are fundamental to its existence, enabling negative externalities of excessive competition and concentration of wealth and power. We must shift to smallerscale methods, allowing us to work in tandem with nature and promote local sufficiency. EF Schumacher proposes we adopt more appropriate technology suitable to the socioeconomic conditions of the geographic area in which it is to be applied. New structures should exchange excessive wealth generation for equitable human

flourishing. Our economic systems should serve us, not enslave us. This will require conscious moral efforts to transform and reimagine our economic structures. We must challenge the viability of our existing socioeconomic conditions of the geographic area in which it is to be applied. We can advocate for more vernacular systems appropriate for their contexts, refraining from becoming supernatural and giving way to the natural order and processes that flourish in their natural contexts. Enterprise on a manageable scale enables improved employment,

22 | DATUM

sustains the economy, and places less strain on the environment. New structures should exchange excessive wealth generation for equitable human flourishing. Our economic systems should serve us, not enslave us. This will require conscious moral efforts to transform and reimagine our economic structures.

1. Bell, Karen. “Can The Capitalist Economic System Deliver Environmental Justice?” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 10, no. 12, 22 Dec. 2015, pp. 1–8.

2. Desmond, Matthew. “American Capitalism Is Brutal. You Can Trace That to the Plantation.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 14 Aug. 2019.

3. Hodgson, Geoffrey. “How Capitalism Actually Generates More Inequality.” Evonomics, Evonomics, 28 Apr. 2018.

4. Mangold, William. “Money-Tecture...Or How Architecture Is Exploited by Capitalism.” Where Do You Stand?, no. 99, 6 Mar. 2011, pp. 74–78.

5. Schumacher, Ernst Friedrich. Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered. Blond & Briggs, 1973.

6. Walker, Darren. “Are You Willing To Give Up Your Privilege?” The New York Times, The New York Times, 25 June 2020.

7. Waugh, Chris. “Is Capitalism Causing Climate Change?” The University of Manchester, The University of Manchester, 7 July 2022.

(Super)Natural | 23

PALESTINE RALLY

Des Moines, Iowa

By the time we sat down to write our reflections on the Palestinian Genocide and invasion of Gaza, 123 days of war had passed. We had planned, as a collective and organized voice, to be as vocal as possible about the injustice being perpetrated by the Israeli state. However close to our souls the images of the atrocity were, the institutions around us insisted on going business as usual. Swept away by the obligations of the academic machine, our efforts went as far to get us a moderate Instagram presence on the issue and plans to include our reflections in this year’s issue.

We were able to make it to the rally on October 24th in Des Moines. Organized by the Party of Socialism and Liberation along with Des Moines Black Lives Matter and Des Moines Mutual Aid groups, the rally started in the Cowle’s Common and led into a march to the Des Moines River.

24 | DATUM

Pressed with time to prepare for the event, I ended up fashioning a makeshift sign with a hand-drawn Palestinian flag on the front, and an embarrassingly scrawled “Free Palestine” on the back. I had never attended a rally before, and wanted to make sure I didn’t show up empty handed. Luckily, there were plenty of others with free hands and signs alike, and the atmosphere was not one I felt self-conscious in. Instead, what permeated the crowd was an overwhelming sense of community and spirit. There was the anguish that followed the stories of Palestinians in the crowd who had family in Gaza, anger for the outburst of violence 75 years after the Nakba, and the hope that follows anytime humans gather to uplift a voice of liberation.

Too often the rhetoric of “natural tendencies” finds its way into the discourse on colonialism. The idea

that some sort of predetermined narrative of dominant and subordinate cultures is the cause of such violence is undoubtedly from the minds of the ruling class. And yet, does this prescribed outcome provide us with hope? In the Anthropocene, where supernatural forces trump all, is nature not on the ropes? Or is it that this supernatural occurrence of malicious genocide doomed to fall to the natural processes of changing social attitudes on liberation?

With a death toll of 29,000 as of February 27th, 2024, it feels pointless to even ask such questions. By now, 1.9 million Palestinians have been displaced from their homes, communities, and social spheres. Maybe it would be a better idea to deliberate on what constitutes urbicide, cultural erasure, or evil itself.

(Super)Natural | 25

A ROOM WITH A BETTER VIEW

Meredith Petellin

May I please?

May I please?

I need to move to a room with a better view.

Are you listening to me? I can’t deal with this.

No I’m not asking anymore. I need a room with a better view. Because if I can’t see it, it’s not there.

May I please?

May I please?

I need to get to a room. If I could only have a room.

Are you listening to me? It’s so cold out here.

No I’m not asking anymore, I need a room with a better view. Because if I can’t see it, it’s not there.

May I please?

May I please?

Be allowed to live, be allowed to live in a room.

Are you listening to me? I don’t have a place, and my blood will be on your hands.

No, I’m not asking anymore. Ignorance does not create freedom.

Because if I cant see it, it’s not there.

A modern problem, a modern solution, of superimposed spikes to keep my existence out.

You can’t look through me. A problem you created through denial.

The supernatural existence of a room with a better view.

Because I can’t see it, it’s not there.

An investigation into the practice of drawing ; and the subsequent dissonant relationships formed between the page, the perceiver, and the drawing. “ “

AFTER HOURS...

Griffin Lilly IDIOM

We live our lives through the stories we tell ourselves. As designers, this ability to visualize, internalize, and communicate these narratives to ourselves and others can unknowingly become a double-edged sword. Within this loop we as designers often play the role of both the spectator and the visionary. Expected to conjure a portrayal of a world without the ability to physically see it, manifesting a reality seemingly out of thin air. Does this rehearsal of repeated observation divert our attention, or does our constant orientation to the work become something more than truthful… more than simply representational? Have we ever been in tune with the world we are conjuring, or has the dissonant identity of the designer and visual nature of the practice blinded us from what’s in front of us?

32 | DATUM

ACT I ( PERCEPTION )

“The process of seeing can only be understood backwards but must be experienced forward.”

What do you see, or rather, what do you wish you could see? Our personal experiences of how we discern and react to the circumstances we occupy is often opportunistic and momentary. What we see predominantly depends on what we are looking for; but it’s hard to tell if we know what we are looking for until we see it... Within this visual practice the intuitive habit of training the eye, slowly becomes a subconscious mechanism of visual calibration. This instinct of seeing what to see

can quickly become an unreliable means of forecasting. Where the tuning of this lens decides what we notice and what we neglect. This adjusting of lenses is only possible due to the role that visual overconsumption plays within our personal experiences. One of the many places where this ritual of assessing visual media is shamelessly evident is within the comparative and competitive nature of the practice. This contagious desire to look and categorize often veils its subject in spectacle. Begging the question, are we hurting ourselves by attempting to see the whole picture?

34 | DATUM

ACT II ( REPRESENTATION )

Our identity balances between two realities, tasked with the role of representing both the technical and the ethereal. These contradicting truths of representation influence the beliefs we hold and our relationship to our work. Does this act of collective faith towards architectural fiction make it any more truthful? Are we lying to ourselves by momentarily trusting in the dishonest representations of a project? Or does the act of internalizing and believing the narrative give the work its validity? The degree to which an individual is willing to embrace and embody a representation is dependent on their optics of it. As creators, we are entrusted with developing a set of instructions… not only to communicate what is to be made but also what is to be believed… For some, the incomplete representation of a drawing, shows more than a resolved finished work ever could. It’s within these gaps of a depiction that these lies become something more than real to the individual.

This fragile relationship between the imagined portrayal of the unbuilt and the physical actualization of it produces a surreal parallel of representational truths. Is the built any more real than the imagined unbuilt? Does the spirit of a project become any less tangible once actualized?

ACT III ( ANNOTATION : DENOTATION : CONNOTATION )

What ingredients are lost in the process of seeing the immaterial become material? What aspects of a drawing are we unable to be represented through a visual medium alone? The architectural means of annotation, denotation, and connotation fill the role when illustration alone fails us. Acting as way-points, this field of data guides us through our journey of accepting a project by vocalizing the persona of the drawing. We as designers need to ask ourselves, should we trust the commentary of these footnotes, what do the guiding lines call attention to, and what do they redirect attention away from? As these markings and notations begin to inhabit and recompose the page, the delineation between drawing and advice becomes one and the same. Contextually, the connotation of the annotations can’t function without the drawing, and the drawing can’t become actualized without these denotations. At what point does the notational space invalidate or become the drawing? Is the essence of a drawing contained within the embracing fields of markings that orbit it, or does this relationship lie outside of our dialect with it?

(Super)Natural | 35

What encounters does the drawing have with us? What conditions are necessary to give a project enough room for it to decipher itself while still remaining an active participant in it? The negotiations we have with ourselves, others, and the work all act to conjure the temperament that the work is restlessly seeking. So, where do we stand in relation to the work and its audience? Does the morality of the drawing seek to deceive its observers? What crude geometries are intentionally being concealed

from the collective eyes of the audience? Has the uncaring nature and composition of the page ever been attentive to the world it is building? This relationship becomes evident in asymmetrical agreements and the power that the work holds over us. The nights sacrificed to mend lines and polishing pixels… the overlooked costs, cuts, and calories necessary to see the work become actualized. We are pre-determinately acting upon the ambitious demand of the drawing.

ACT IV ( NEGOTIATION )

It’s in the Afterhours … the sleepdeprived design decisions… the moments of nocturnal clarity… and the late-night strolls home… that the drawing is haunted by its own hypotheticals… It’s in the breath of momentary solace after a review… it’s in the lingering phantom regrets, of unresolved details, and virtues lost along the way… that the work finds itself looking back…

Situated directly in the middle of nowhere, standing in the exhausted landscape of the page, the drawing for a moment becomes something more than just representational… As it reminisces on the life it led and the part that it played, it wonders, was it ever in tune with

may not have spoken in the way it saw just, granted… all markings are afflicted by their own lack of trust. When it’s all out of time, and there’s nothing left to erase, no marking, no annotations, no surfaces left to trace, will the blank page remain an ethereal space… or will the lines recall their once intended place?.. The page is for those who can let go and forget, as the drawing will remain dormant till those conditions are met. If its lines are heavy and it begins to step out of scale, the page must take a detour and learn to exhale…

Consider the horizon; it isn’t trying to look right, it simply looks to the land to re-allocate its light… If you look real close, the drawing isn’t that… it’s this, it’s the depth

ACT V ( SPECULATION )

Arden Stapella NEIGHBORS

Based on the short story by Raymond Carver.

Based on the short story by Raymond Carver.

(SUPER)NATURAL NATURE

Sierra Wroolie

As architects, we often see ourselves as saviors. We are tasked with solving wicked problems and intellectually challenged on the regular to design solutions for these complex problems. But, the reality is not that everything needs to be saved. Sometimes, no intervention is the best intervention. The wild doesn’t seek taming. The natural shall never falter to the synthetic.

To preserve is to be conscious. It is a method of storytelling, a documented history. Our story unfolds through cause and effect, the balance of risk and reward. To preserve is to see the bigger picture, to understand our place in time. To destruct is to forsake, to ignore, and to avoid. Destruction gives up in favor of a clean slate, creating a blank facade. New York City is over-saturated with blank, empty facades, lacking a purposeful narrative. With a lack of purpose, what is the point?

AN EXPLORATION OF THE NEW YORK CITY’S HISTORICAL AND CONTEMPORARY ECOLOGY THROUGH THE LENS OF KOOLHAUS' DELIRIOUS NEWYORK.

40 | DATUM

(Super)Natural | 41

In its raw state, the Highline was an anomaly in the city. Ecology is untouched, an unintentional rewilding. However, such anomalies cannot exist in New York City. There has to be a method for control, a systematic structure, a set of guidelines and rules. To be wild in New York City is to break the Grid, a forbidden endeavor. Central Park is a global icon. Created to provide a natural

escape from the hustle of New York City in response to the desire for rural ecology following the city’s rapid urbanization. While the picturesque scenery appears natural, it is all manufactured—A built environment. Every sight line traced, every step surveyed, every experience curated. There is no wandering when the path is predetermined.

“ In Manhattan's culture of congestion, destruction is another word for preservation.

“

42 | DATUM

“

The systematic conversion of nature into a technical service.

“

A SERIES OF MANIPULATIONS AND TRANSFORMATIONS PERFORMED ON NATURE 'SAVED' BY ITS DESIGNERS.

(Super)Natural | 43

INTERVIEW WITH Joshua Stein

DATUM had the opportunity to have a conversation with Woodbury University Architecture Professor, researcher, and practitioner Joshua Stein. Stein is the founder of Radical Craft, a Los Angeles-based research and design studio operating between fields of architecture, art, and urbanism. He was invited to ISU’s College of Design to give his lecture, Slow Motion Materiality. Below is a transcription of the discussion on February 17th, 2024.

Stein’s lecture shares his research on topics adjacent to Reciprocal Landscapes and circular economies of materials within the practice of architecture. His work questions to what extent we think beyond purely quantitative effects to the environment while also tracking and tracing the extractions that build the modern metropolis.

* Kiel Moe is an architectural theorist who has written extensively on building environmental systems and the role of energy exchange in architecture. The reading Stein refers to is of Moe’s ideas on the Seagram building. In the text, Moe lays out a comprehensive ecology of the Seagram building, its design, construction, and the cultural practices that gave rise to the building and its conception.

Thank you for taking the time to speak with us. We wanted to start the conversation with our observations of the practice of architecture and how overwhelming it can feel as a designer to understand one’s responsibility. While there is a lot of excitement built around the energy of rising to the challenges of living, adapting, and planning, there is also a lot of room to wonder what our responsibility is in all of architecture’s perceived externalities.

Okay, yes, are you all familiar with Jane Hutton and Kiel Moe?

Yes, our third-year Landscape Studio touched on Jane Hutton’s idea of Reciprocal Landscapes.

Yes, Jane Hutton and *Kiel Mo seem to be pursuing similar projects, with Hutton focusing on landscape architecture and Mo on architecture, around the same period. Their books were released within a short timeframe of each other. I introduced my students to Mo’s book on building nutrition, and they found it incredibly daunting. Mo delves deep into the origins of every building material, exploring what is embodied within each structure. My students felt overwhelmed, realizing that this level of investigation is necessary for every building project. I empathize with their feelings of being overwhelmed. However, I believe it’s important to confront this discomfort rather than letting it paralyze us.

What I aim to achieve is to delve into projects like the Geological Atlas of the Built Environment, which delves into the geological components of urban development. For instance, studying the Monadnock building involves understanding its geological aspects. My goal is to find methods to portray these extraction sites within architectural structures. Architects excel in creating tangible objects, so the challenge lies in acknowledging that every building design also impacts or alters a landscape elsewhere in the world.

(Super)Natural | 45

JOSHUA STEIN

DATUM

JOSHUA STEIN

DATUM

DATUM

Several of us last semester were also examining sites of extraction. We were working with * Kathryn Yusoff’s lecture on geologics, natural resources, necro-politics, and infrastructures of extraction. We are curious about this in relation to the Monadnock Building case study. How did you come up with the representation methods for the project?

JOSHUA STEIN

* Kathryn Yusoff’s lecture titled “Geo-Logics: Natural Resources as Necropolitics” was a talk given at the Harvard Graduate School of Design on November 16th, 2020. During the talk, Yusoff ties together the stratification of race in the imagination of settler colonialists and the advent of the discipline of geology as manifestation of this imagination. She argues that normative attitudes towards natural resources are a result of white geology and black undergrounding.

I’ve been exploring geology as a means for architects to engage with pressing issues that we should be addressing. Despite our proficiency in representation, there are certain skills beyond our traditional scope. So, temporarily, I turned to geology to see if it could offer fresh perspectives. One aspect is the notion of gradual material movement over time. We instinctively grasp this concept in architecture, even if it’s on a scale of decades for a building. We sense the subtle shifts and settling.

However, we seldom envision these processes on regional or continental scales. Although we understand that building materials are sourced from distant and sometimes nearby locations, we tend to compartmentalize these issues. There’s the building itself, and then there are the materials used in its construction. Before they become part of our building, we often consider them someone else’s concern—a matter for another discipline to handle.

Culturally and disciplinarily, what do we do? We’ve inherited a really problematic situation. And how do we keep moving forward, understanding that it’s fundamentally flawed? It’s probably too much to dismantle it completely, but portions of it need to be dismantled and rethought. That’s a really kind of, like, lofty answer to your question. But I think this is the fun of the moment that we’re in. What else can we do besides just employing a little bit of optimism and assuming that we can make some progress? Optimism maybe is a dangerous word, but there are places where we can rethink and make some fundamental changes.

46 | DATUM

“There’s the building, and then there’s the construction materials that go into the building. But before it’s the building, we don’t really consider it ours, right? It’s somebody else’s. It’s another discipline’s problem, another discipline’s responsibility.

“

complexity, especially in architecture, where simplification often prevails due to external pressures. Your work explores these higher powers and their interplay, aligning with our journal’s theme this year of examining Supernatural and Natural forces in the landscape. Take the Los Angeles River, for example; the natural tendency of the soil to wash away water contrasts with humanity’s supernatural intervention to control it. While we flock to coastal areas for their beauty, we often overlook the environmental consequences of our infrastructure. Do you explore the relationship between these forces in your work?

The term “supernatural” sparks my interest as it challenges our conventional notions of what is “natural.” I’ve come to realize the extent to which human activity has reshaped our planet’s landscape. Despite this, we still hold onto the idea of untouched “wild” spaces, even though they’re increasingly rare. The concept of “reconstructed wetlands” embodies this transformation, revealing how many areas we consider “natural” are actually recent human interventions. For example, in Chicago, the transformation of lawns into wetlands in parks has led to the thriving of diverse species. While I can’t apply this success universally to all cities, it’s a promising trend. Furthermore, the term “supernatural” also suggests something beyond the rational, which intrigues me. Although I don’t often delve into this aspect in my work, I strive to infuse my projects with a sense of enchantment—an element that sparks discussions beyond mere rational discourse. Recently, at the Beauty Investigated Symposium, I explored the magical qualities of materials like glaze. I’m comfortable embracing this dimension because I believe it enriches our engagement with pressing global issues. By crafting artifacts with mystic qualities—

48 | DATUM

JOSHUA STEIN

objects that ignite conversations and evoke wonder—I envision a path forward that excites me.

Many of us kind of are bonded by architecture’s involvement in humanities. We believe we can relate to the broader culture without necessarily having to be right in tune with those “universal” or so-called “natural” laws of science. It leads us to ask: are you a spiritual person?

I would say yes, although I shy away from religion. Not because there are automatic, inherent problems with religion, just because there are some historical problems. Those are two different things, right? It puts me in a place of questioning and skepticism. But the skepticism isn’t necessarily a spiritual skepticism. It is a skepticism of cultural institutions. DATUM

Then to touch on this idea of the sacred, we had a question about your LA River project. At what point does human-made geology need to be preserved? What’s the difference between the LA River basin and Trajan’s Column in Rome?

The recent projects I’ve presented, such as the exploration of sediment-based cultural heritage and the study of Trajan’s Column, prompt us to question what aspects of our built environment we value and how we define that value. While I don’t profess to have all the answers, I maintain that within our cultural heritage, we must acknowledge even the toxic elements as part of our collective legacy. Take, for instance, a town in Italy known for its wool textile industry; its identity cannot overlook the associated toxicity. We must embrace the entirety of our heritage, recognizing that there are no externalities—no way to separate the good from the bad. In the debate between preserving Trajan’s Column and addressing the eroding concrete of the LA River, there’s a legitimate discussion to be had regarding which deserves historical designation. Not every structure warrants preservation; some, like the dingbats in Los Angeles, are poorly constructed

DATUM

JOSHUA STEIN

JOSHUA STEIN

“

“ What aspects of our built environment do we deem valuable and how do we define them?

and offer sub-par living conditions. However, we need to assess whether they possess historical significance or potential as viable housing options. Striking a balance between preservation efforts and the pressing need for more housing and improved living conditions demands nuanced consideration.

Many of us actually were in Rome last spring and got to experience the spolia of the city, or the reuse of materials from monuments for use in others. We were wondering if this enhanced or complicated your work with Trajan’s Column?

During my time in Rome in 2010 and 2011, I hadn’t yet explored architecture and urbanism through the lens of geology. However, living with art historians who could pinpoint the origin of every architectural element in medieval churches, I became aware of the intricate provenance of structures. Trajan’s Column, unlike the Colosseum, was never dismantled extensively, though it bears blemishes from Middle Ages’ interventions. My project critiques this dual perspective, wherein Trajan’s documentation oscillates between a pristine ideal and the reality of weathered decay, neglecting the middle ground of analytical examination. I’m intrigued by the material realities and fantasies of ancient architecture, questioning whether structures like Trajan’s Column were designed to degrade over time. This exploration delves into historical concepts we seek to integrate into contemporary architecture. Spolia, the reuse of architectural fragments, parallels anthropogenic weathering, prompting us to consider how we guide the gradual erosion of structures. Adaptive reuse, while essential, may not fully engage with the materiality of structures.

Your lecture’s perspective on adaptive reuse, as nudging existing materials to better suit human needs, resonated with us. The notion of a “receptacle for its own dissolution” is particularly striking, applicable not only to

(Super)Natural | 51

DATUM

JOSHUA STEIN

DATUM

Trajan’s Column but also to cities at large. As we metaphorically “mine” our metropolis for materials and re-purpose them, it’s akin to hollowing out or eroding what’s no longer necessary, like fortifications against climate change. Prioritizing projects and developments with suitable materials becomes crucial, though it’s somewhat disheartening to view our cities as aging and receptacles for their own decay.

The idea of dissolution adds a nuanced layer to the concept, slightly distinct from decay. While “circular economy” aims to reuse materials optimistically, “receptacle for self-dissolution” evokes a more somber tone. The term “circular economy,” while rational and directional, may feel somewhat lacking poetically, particularly with the inclusion of “economy,” which implies financial concerns rather than solely a means of resource management.

Does the term circular economy imply a closed system - one that ignores a broader system at a maybe planetary scale?

Maybe, but I think it is okay to consider closed systems. Considering closed systems, such as imposing jurisdictional boundaries around a city to restrict material flow, can offer valuable insights. This approach is akin to fasting, where one resets their metabolism. Resetting the metabolism of a metropolis, metaphorically speaking, is necessary for sustainable urban development. Temporarily isolating a city from external material inputs, even for a period like 20 years, could prompt innovative solutions.

Sounds like a fun social experiment!

Exploring the concept of walled cities or urban enclaves, akin to Renaissance Italian citystates, is gaining attention among urban planners. These entities encompass a territory larger than a city but smaller than a state, focusing on meeting the metabolic needs of the city within its boundaries. William Cronon’s “Nature’s Metropolis,”

52 | DATUM

DATUM

JOSHUA STEIN

JOSHUA STEIN

DATUM

JOSHUA STEIN

DATUM

which discusses the colonization of Chicago across a vast territory, offers valuable insights into the historical context of resource utilization and urban growth. The book sheds light on contemporary issues stemming from historical practices, providing a nuanced understanding of urban development dynamics.

Overcoming political boundaries is a source of hope, particularly with the growing movement among youth to challenge abstract divisions. The concept of a city-state like Chicago, encompassing surrounding areas, feels relevant today. However, considering material needs within a walled-off city overlooks the complexity of modern society, which extends beyond raw materials to encompass psychological and cultural needs. While there’s a push for hyper-localization, we’re still influenced by ideals and narratives from distant places, creating a tension between localism and global connectivity that’s challenging to reconcile.

JOSHUA STEIN

In the past, vernacular construction techniques aligned seamlessly with available materials, but today, with access to global techniques, this alignment is less straightforward. Material availability is flexible but comes with environmental costs, such as the atmospheric footprint of aggregate mining in parts of Los Angeles. This extractive industry contributes to respiratory issues in affected neighborhoods, compounded by factors like freeway pollution and waste incineration. Viewing these issues through a geological lens underscores their complexity, particularly the airborne impact of construction materials on local communities. These communities face a dilemma: while dependent on these industries for jobs, they also suffer from their negative effects. Transitioning to more humane modes of production and extraction, as part of a broader concept of a just transition, is imperative. However, it’s essential to ensure that frontline communities aren’t left behind in the global push for change.

(Super)Natural | 53

SILENCED VOICES: The Forced Sterilization of Latina Women

Amani Taleb

The history of sterilization in Puerto Rico is a grim testament to the exploitative forces of colonialism, driven by a demand for Puerto Rican labor but devoid of any concern for their well-being or autonomy. The ruthless appropriation and exploitation of Puerto Rican lands for profit mirror the broader patterns of oppression ingrained within this system. This project seeks to forge a path towards empowerment and healing, where individuals reclaim ownership of their bodies and ancestral lands by sharing their stories and reshaping dominant narratives. Through this collective effort, we strive to disrupt the destructive cycle of colonialism and channel our creative energies toward acknowledging and redressing the profound harm it has inflicted. Through storytelling, advocacy, and collective action, we aim to foster a new environment of empowerment and healing. It is a journey towards reclaiming dignity, restoring sovereignty, and building solidarity within and beyond the Puerto Rican communities. Confronting the actions of colonialism and charting a path towards a more just and equitable future.

56 | DATUM

(Super)Natural | 57

PRESERVATION & SUSTAINABILITY OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

Tim Zhang

When imagining the National Park System, the public imagines a picturesque scene in their mind; the deep forests and colorful geysers of Yellowstone, the shining half dome and beautiful valley of Yosemite, or a sunset over the peaks in Glacier. In this image, this land is untouched by humans. However, it cannot be overlooked that this is not at all the case. The land that National Parks reside in is an incredibly designed and supernaturally altered built environment. The National Park System is a place of preservation, but they are also a major attraction for tourists and a site of consumerism. This essay seeks to understand the issue of conservation and sustainability in association with the National Park Service and System, whose mission is to “preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the national park system for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.” By looking at the history of the National Park Service, as well as its architecture and its built environment in the National Park System, one can begin to understand the labor and struggle that is preservation and sustainability. Since the founding of the National Park Service, environmental awareness began growing, and especially now in the 2010s and 2020s, environmental awareness has only increased. The National Park Service’s leadership has started to see nature as the basis of our civilization. These opinions have led to more inquiry about park administration.

How has the National Park Service managed to strike a balance between the preservation of the natural untouched landscape while also building roads and other structures in uninhabited areas that were previously only visited by wildlife? How does the National Park Service decide if rules promoting sustainable design are appropriate? To understand the issue of sustainability and preservation today, one must look at the history of ideology revolving around conservation and sustainability in the past. Before even the National Park Service was established, the tale of sustainability and preservation in the National Park started. Growing concern about the country’s natural resources’ future marked the conservation era in America, which spanned the years 1891 to 1920. One important topic that gained much media attention was the wide utilization of American resources. It was backed by several organizations and professions, including businesses like railroads, mining companies, and logging companies, that had financial stakes in managing natural resources. High-level politics on conservation were driven and centered by several economic and cultural concerns. Protection at the period was intimately correlated with how people reacted to the changes caused by the development of modern industrial society. As the years passed, on August 25, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson issued an executive order that established the National Park Service as a brand-new government agency inside the Department of the Interior. Its duty was to protect the 35 national parks and monuments the organization was in charge of, as well as future ones. Most Europeans and Americans thought of nature as a source of food, clothes, and shelter prior to the nineteenth century. Early environmental protection efforts in Europe were centered on the work of affluent landowners to conserve wildlife for game

shooting and trees for timber. The root of the issue lies here in classism and an ironic consumerist ideology. With these deeply held principles in mind, the Park Service was established to unify and bring order to the management of national parks, but it was not yet apparent what national parks were to be. Nobody knew it explicitly; it was simply widely known. Here, a split grew in the National Park Service’s purpose: was it to be geared toward utilitarianism or recreational? The main participants in this dialogue are the writers, journalists, artists, and organizational leaders. From the story’s beginning, transcendentalists like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman, as well as artists like Thomas Cole and Asher Durand, captured the majestic grandeur of the American environment. These authors and artists influenced the principles behind the American conservation movement. Nowadays, the representation and uplifting aura revolving around preservation and National Parks come from shows, books, and social media content. Along with the artists, creatives, and organizations, it’s the politicians who ultimately decide the policies dictating the management of the National Park Service that holds a great seat in the dialogue of National Park management, preservation, and sustainability. The Yellowstone National Park Protection Act was enacted by the US Congress in 1872. The bill’s creators intended for it to be a “pleasuring ground”

(Super)Natural | 61

for the benefit of all Americans, with the exception of Native Americans, who would be practically prohibited from park property. The ethical concerns around sustainability and the cultural preservation of the National Parks are brought to light by this action. When the Service may be more interested in safeguarding the natural environment than in developing it for more human appeal, the Service, whose job it is to protect the land, must evaluate the role of leisure and tourism. Commercially driven rules over time, such as the Antiquities Act and the Sustainable Building Program, have pushed for more preservation and sustainability. Presidents have the authority to designate portions of public property as national monuments under the Antiquities Act in order to preserve their ecological or historical importance. The preservation of historic Native American sites and artifacts was the principal objective of the Act. To lessen the negative environmental consequences of buildings, the Sustainable Buildings Program is in charge of developing service-wide policies and initiatives.

provide the president the power to shrink the size of already-existing monuments. These changes have given rise to the Alt National Park Service protest movement. The organization includes representatives from the National Park Service, other federal agencies, state park administrators, environmental experts, and others. When considering sustainability and preservation, the National Park Service has a greater sense of direction today; nonetheless, the main difficulty is the funding and policies that are provided to them.

In relation to the issue of sustainability and preservation of the environment in National

The National Park Service continues to work toward sustainability via several projects, strategies, and programs. The National Park Service’s staff has declined by 11% in recent years, despite the fact that park visits continued to rise to record-high levels between 2011 and 2018 when the budget was severely slashed. Additionally, the Natural Resources Committee of the House of Representatives advanced a bill in late 2017 that would make it more difficult to establish new national monuments under the Antiquities Act and would

Parks, there are many views. Some people, such as those in the Alt National Park Service, believe that the National Park Service needs help. Over 2.1 million Alt National Park Service members believe that the National Park Service is not strong enough to fight for its mission of preservation, especially due to the prior administration’s attitude toward the environment and wildlife. The government and the National Park Service claim that they have a more positive outlook on their work and believe everything is going according to plan. Still, they maintain that they are “a global leader in safeguarding natural and cultural resources.” As a result, they protect the best vistas in the nation and serve as an example of how to manage resources sustainability. Environmental organizations, like the Sierra Club, hold a different point of view. They think that visitors to parks could endanger

them and that any development done to make accommodations for them will worsen the natural settings of the Park System, just as civilization has done to the rest of

the natural world. Perhaps earlier efforts to host tourists were overly excessive. From the beginning and growth of the National Park Service, there have also been critiques from the public, the workers, and journalists. A journalist who has long watched the Park Service describes it as having “accumulated inconsistencies,” “confusion of purpose,” and “a crisis in dilution of purpose” in Ronald A. Foresta’s book National Park and Their Keepers. Another visitor also critiques the Service, saying that “the Service is confused by America’s changing values and policies.” From global environmental groups, the United States government, and the public eye, the National Park Service has many different views on how it’s managed its mission of sustainability.

Park Service’s sustainability initiatives and collaborations with organizations across the nation speak to how they are able to stick to their mission to “preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the national park system for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.” Even though they cater to tourists, I think it’s unrealistic to expect

I think that although many of the National

grow about preservation and sustainability, especially with a system whose mission is to preserve the natural and cultural

THIS DESIGN IS VERY HUMAN

Aidan Andrews

Every. Design. Project. is a series of decisions. All we can hope for is that these decisions are based in logic and empathy. It does not matter whether it is a space, image, or object—there is an understanding as designers that our decisions should make sense.

66 | DATUM

(Super)Natural | 67

68 | DATUM

Every. Body. is made up of a series of decisions. All we can hope for is that these decisions are based. It does not matter whether it is a partner, flavor, or word - there is an understanding as people that our decisions should be based.

(Super)Natural | 69

INTERVIEW WITH Aaron Betsky

DATUM had the opportunity to sit down and talk with architectural theorist and author Aaron Betsky in wake of his most recently published work, The Monster Leviathan: Anarchitecture. He joins us at the King Pavilion, sporting a velvety, iridescent suit and is in good spirits to be among our enclave of eager students who have come to engage with him before his talk that evening. We sit at a long table in the sunny Hansen Exchange and pick his brain on topics from authorship to Hollywood world-building.

70 | DATUM

DATUM

DATUM has been investigating the supernatural and the natural. We would love to get your thoughts on these terms as they relate to architecture and beyond.

The immediate association lies with horror, Sci-Fi, and gaming genres, which have influenced architecture, albeit in a more subdued manner. While architectural hints of a gory aesthetic exist, they often undergo a process of moderation. However, there’s a historical connection to the eerie and gruesome aspects of architecture dating back to the late 18th and early 19th centuries, particularly evident in neogothic forms. Additionally, there’s a link to eclectic styles that viewed the supernatural as belonging to another realm, often claiming inspiration from what they posited as exotic cultures, such as Arabic and Chinese ones, or what they imagined those to be.

Queerness also intersects with this narrative in a manner perhaps best exemplified by figures like William Beckford. Beckford, the son of England’s wealthiest man (a fortune based on slave plantations in the Caribbean), faced social ostracization after he was caught in a sexual situation with a cousin. Retreating to the countryside, he constructed Fonthill Abbey, blending neogothic elements with eclectic ones. His novel “Vathek” is regarded as an early horror work, reflecting his outsider status. This association between the supernatural and transgression extends to challenging societal norms and our understanding of humanity as shaped by architecture.

Furthermore, the term “supernatural” can evoke notions of something exceptionally non-affect, cool or radical, super, akin to hip-hop aesthetics. This perspective prompts reflections on architects like Virgil Abloh and their ability to imbue projects with a supernatural, organic sensibility.

DATUM

It’s cool to switch things up and focus on the idea of super-designed stuff seeming totally natural. Take the US park system, for example, and those trails that look all wild and untouched but are actually carefully planned out. They’re designed to make you feel like you’re out in the wild, calling the

(Super)Natural | 71

AARON BETSKY

* Gregory Crewdson’s photography captures the enigmatic and vivid essence of rural Northeastern life, blurring the lines between everyday reality and the uncannily surreal. His meticulous attention to detail and ability to generate strikingly vivid images has made a significant impact on the art world. Crewdson’s work resonates deeply, especially with those from the Midwest, as it embodies a spectrum of emotions and narratives that speak to the complexities of domestic and rural existence.

shots and feeling totally free.

In essence, these designed spaces are carefully crafted to evoke a sense of harmony with nature while providing visitors with a controlled and curated experience. Despite their artificiality, they offer a semblance of immersion in the natural world, highlighting the powerful role of design in shaping our perceptions and interactions with the environment.

This discussion prompts a deeper exploration of how design can influence our relationship with nature and blur the boundaries between the artificial and the natural. It also raises questions about the authenticity of our experiences in constructed environments and the ways in which design can mediate our connection to the natural world.

Taking it further, there’s this vibe that Disney, in particular, nails with this whole hyper-real thing in the work of their “imagineers.” You also might want to check out the work of some photographers interested in the intersection of real and unreal architecture from the past 15-20 years, going back to the early 2000s. One guy that pops up is * Gregory Crewdson’s. He’s based in New York but mostly shoots in the upper northwestern part of Massachusetts in old mill towns. He started off making images of interiors that seemed totally normal, like your average lower-middleclass home. But then you realize there’s something funky about them. They’re crazy high-res and detailed—it takes months to put one shot together, like a whole movie crew getting it just right for this one surreal moment. He captures it with this super-duper high-res digital camera, the kind NASA uses, and presents it in this mind-blowing detail. So it messes with your head because it’s so ultra-realistic, and we usually associate realism with reality. It’s like a hypersuper-reality, but also kinda eerie because something’s not quite right about it.

Absolutely, the integration of AI into architectural workflows raises interesting questions about the potential impact on the human aspect of design. AI excels at creating hyper-realistic and

72 | DATUM

AARON BETSKY

DATUM

DATUM

exaggerated outputs, often surpassing what humans can achieve on their own. While this can be incredibly useful in streamlining processes and pushing creative boundaries, there’s a risk that relying too heavily on AI may diminish the human touch in design. Architecture, at its core, is deeply intertwined with human experiences, emotions, and cultural contexts. The unique perspective and creativity that humans bring to the table are what give architectural designs their soul and character. If AI becomes the dominant force in the design process, there’s a possibility that designs could lose some of their humanity, becoming sterile and impersonal. This could potentially lead to a “supernatural” effect in design, where structures lack the warmth and connection to human experience that traditionally imbue them with meaning. It’s crucial for architects to strike a balance between leveraging AI’s capabilities for innovation while retaining the human element in their designs. By consciously infusing designs with empathy, cultural sensitivity, and a deep understanding of human needs, architects can ensure that their creations remain grounded in humanity, even in an increasingly AI-driven world.

(Super)Natural | 73

Gregory Crewdson Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003, 2023

DATUM

midjourney prompt: distorted_ landscape_superimposed_with_ unique_element_in the_style_of_ Aaron_Betsky_low_saturation

“

AI is essentially a mash-up of countless human actions, decisions, and creations. It’s this blend that makes AI appear both totally natural and kind of weird, almost like it has a supernatural quality.

“

AARON BETSKY

DATUM

I disagree with you, respectfully, because the issue lies precisely there. It’s both the beauty and the problem. AI is essentially a mash-up of countless human actions, decisions, and creations. It’s this blend that makes AI appear both totally natural and kind of weird, almost like it has a supernatural quality. However, this also means that mistakes and fantasies get mixed in, creating what they call in the field, hallucinations, and thus a supernatural vibe. AI starts to “hallucinate,” adding to its mysterious aura. So, the real question is where AI fits between humans and the abstract idea of humanity. It’s a deep question, and I think it lands somewhere in between, don’t you?

You bring up a really good point. We don’t know if AI will ever cross that threshold where it can self-generate and be fully distanced from the biases of humans. We have AI that are constantly replicating these biases and just causing a lot of problems. But we also think a more interesting conversation is about relinquishing control. As a society and especially in the Midwest, there are still reservations to accept AI. To what degree are we willing to relinquish some sense of control? We think AI is fascinating and advancing it and understanding it is critical. And we believe the more that happens, the more abstract it will become, and the more of a collective knowledge will become, rather than this biased abstraction of things or agendas.

AARON BETSKY

Again, don’t let it fool you. It’s just another tool, and now it’s an incredibly powerful tool, marking a big change in terms of how I can work and the effectiveness of my work, but it’s still a tool. I think the best students I’ve seen refuse to be in awe of it and just say, okay, how do I get this darn thing to do what I want to do? Get over the fun part of drawing Villa Savois as a home in Game of Thrones or writing a review of Louis Kahn’s Exeter Library in the style of Aaron Betsky, which it did frighteningly well. Get beyond that, and then I start saying, okay, no, I want you to do this. I want to get this. I want this. I want this. I want. I start becoming an agent who uses that as a tool. So, in general, I’m very tired and irritated by these continual discussions that crop up in architecture schools about how tools will

(Super)Natural | 75

change everything. Many people complain that the youth of today don’t know how to design because they have no eye-hand coordination between the pencil. Its nonsense. Just drives me crazy. I doubt Midjourney will be the last of AI tools for architecture, but whatever it will be, it will be prompted by us as designers and free agents.

Could you give us a little bit of insight into what your lecture is going to be about tonight?

The book is really my big theory thing. So it’s really, first of all, just that it’s my theorizing in a book, and it tries to unearth a kind of secret history of modernist architecture that proposes a series of alternate realities, not utopias or dystopias, not solutions, not ends, but other ways of looking at and interpreting the world as we have made it, finding within the world as we have made it, perhaps supernatural overtones, things that we might not have seen things that might not even exist except in the interpretation of the writer. And the writers are not just architects; they’re philosophers and critics and painters, novelists, poets, and things like that.

How did you produce the cover image of the book?

It’s funny, when I was wrapping up the book and thinking about the cover, I stumbled upon this guy, Cesar Battelli, an Italian architect living and teaching in Madrid, who had discovered Midjourney right after it started about a year and a half ago now, and was creating these whimsical images. He introduced me to this artist named Desiderio Monsu, who might have been, in fact, two different artists: a Northern French or Flemish artist living and working in Naples at the end of the 17th century, known for these bizarre, visionary paintings. Very strange stuff. So, I reached out to Cesar and asked, “Hey, can I maybe use some of your images for my book?” He replied, “Sure, send me the text, and I’ll create one for you.” So, he read the text, and this is his interpretation of what the book is all about.

DATUM

How does that work in terms of authorship, if it’s generated through a pattern, or just in terms of publishing an image that is created through Midjourney?

76 | DATUM

DATUM DATUM

AARON BETSKY

AARON BETSKY

DATUM

Well, there’s nothing recognizable in here at this point. I mean, I’m sure if you were a really good art historian, you could probably parse some of the sources that are folded into the image. But that’s the thing about Midjourney. It rips everything off. Now, everyone from the New York Times to various hip hop artists and others are suing Midjourney and Dall-E and these platforms, including ChatGPT, for making use of their authored material because it all gets consumed by the algorithms.

The real source, of course, is collage, which I talk about a lot. You’re using bits and pieces that other people made. What’s the famous saying, “Good artists copy, great artists steal”? Most of hip hop is made up of this collage approach. Well, the first lesson I learned in architecture school was to get in, make your move, get out fast. And the second lesson I learned was, if you like it, steal it.

We are really fascinated by that term collage in the capacity that you’re using. Could you elaborate more on that as maybe a form of creative practice and how you’ve been applying that as a method?

I’m less interested in the idea of coming up with an ordering system and imposing that on whatever project is at hand and more interested in hunting and gathering, finding nascent orders, however ephemeral they might be, everywhere, and combining them and putting them all together. So, to me, that’s a very different attitude towards architecture. I’ve always been interested in those architects who don’t come up with the grid, the geometry, the big idea plunked down, and more interested in those architects who find fragmentary orders, images, tastes, and smells within the project and then try to build that out.

Aaron Betsky is a recently retired Director and Professor of the School of Architecture and Design at Virginia Tech. Owing his upbringing to a mixture of experiences in the US and The Netherlands alike, he has enjoyed a fulfilling career of curation, academia, and authorship. Offering many provocations on utopia and dystopia alike, Betsky came armed both with personal and historical narratives that reveal architecture’s chaotic and monstrous tendencies. He brings forth a powerful message on how we could conceive of our environments and what that means for the future.

(Super)Natural | 77

AARON BETSKY

AARON BETSKY

WHAT’S IN A NATURE?

Finn Digman

at once i am agony, i am awe pushing something colder thicker slower than blood

at once i am ire, i am indifference carving my space in this world arrows drawn on tempered skin

can’t you see for once i am the contour tracing the lands below flesh hewn for space in this world

In a fable accredited to Lev Nitoburg, a scorpion needs to cross a river; a frog offers them a ride; halfway across, the scorpion (as is their nature) stings the frog, and together, they drown. This tale is used to explain the inherent (natural) viciousness of people or systems. That, if it is in our nature to destroy, we will do so, no matter how it may harm us. In this framework, the viciousness of the scorpion is assumed. So is the naivety of the frog. But nature is not a single truth or a rigid thing with simple divisions. Scattered in visuals and poems throughout this publication, I ask who defines the natural body in its singular, emotional, socio-political, and creative form and what we are allowed to do with those definitions. I question the separation of the body from the landscape. I wonder at what imaginaries and physicalities our anger, fear, and sorrow create and how such creations can be used for accountability or instrumentalized as tools of oppression. I explore the division of engineered artifacts from natural ones and the evolutionism evident in supposedly natural systems that separate us from nature. All these to ask: what, if anything, is natural? What is greater than nature? Who gets to decide? And what do they do with that decision?

(Super)Natural | 79

80 | DATUM

(Super)Natural | 81

82 | DATUM

Can you imagine my rage? see me coming, fear me see me running, hunt me down you have hurt the ones I love

(Super)Natural | 83

MIDWEST MONUMENTS

Connor Shanahan & Daniel Leira

Industrial architectures of the Midwest emerge from the plains as monuments of extraction. Their towering dystopian presence protrudes as skyscrapers in a prairie environment. While often overlooked for their architectural qualities, these structures carefully compose the relationship between bodies, buildings, and machines. This creative research surveys the architectural contexts, forms, and experiences of these industrial structures and their contributions to the Iowan landscape.

84 | DATUM

(Super)Natural | 85

86 | DATUM

(Super)Natural | 87

88 | DATUM

(Super)Natural | 89

90 | DATUM

BEFORE THE BOMBS CAME

Sophi Allen

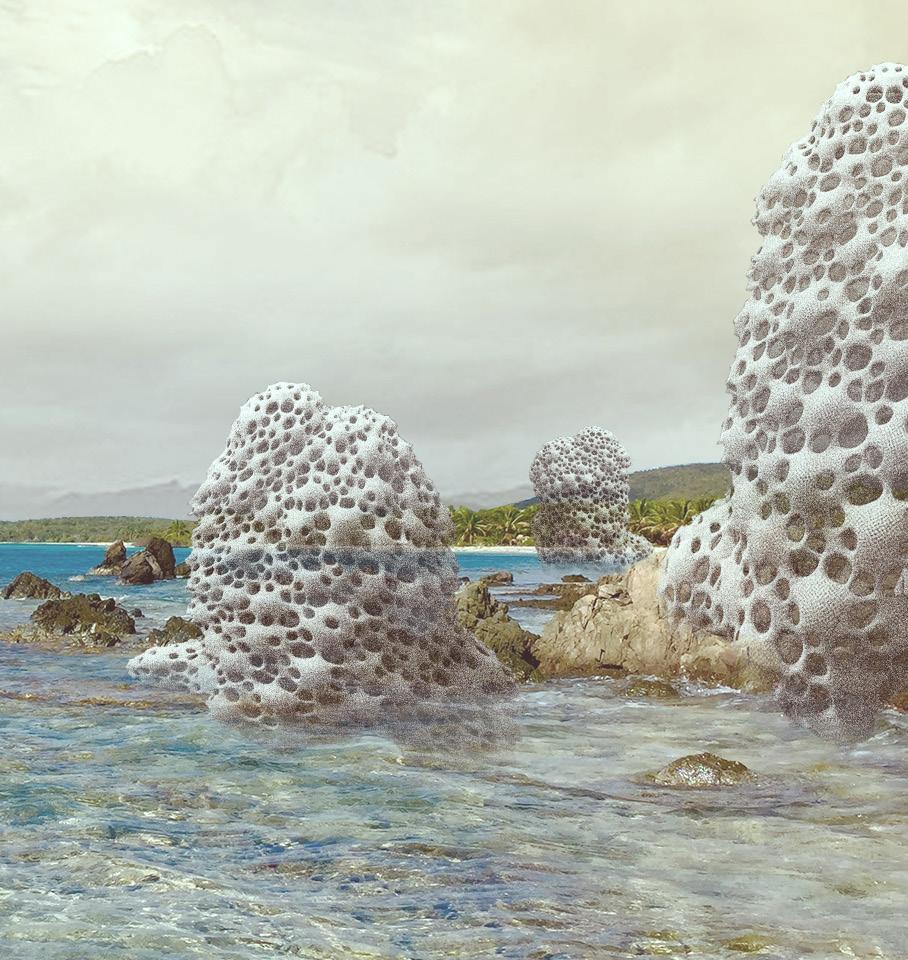

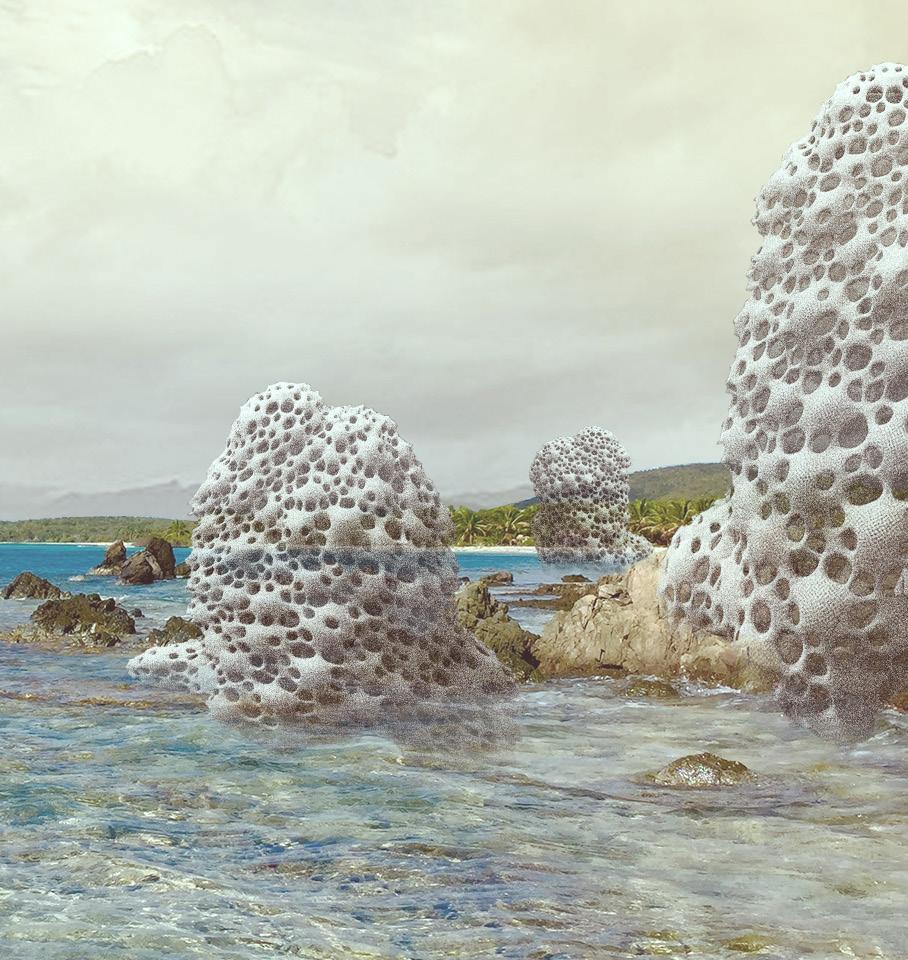

04.15.3067

They grow slowly.

Yet I know that they are alive because of photos taken here from past generations. Where did they come from?

They are sustained by the toxins within the earth. How lucky they are to have found this place, where the crater-like scars from the past provide neverending nourishment.

They are beautiful, inhabited over time by the tiny creatures native to the island, resembling an extreme topography that once might have existed - before the bombs came.

(Super)Natural | 91

Byproducts and Sound Frequency Emissions of US Military Ordnance during the Military Occupation of Vieques, PR (1938-2003)

Propane, Ammonia, Hydrogen, Hydrogen Cyanide, Methane, Methyl-Alcohol, Formaldehyde, Acetylene,Ethylene,an d Phosphine Aluminum Oxide (35-38%) Water Sand Gun Powder (Lead, Antimony, Barium, Calcium, Silicon, Antimony,Barium), Depleted Uranium

Carbon (6-13%)

92 | DATUM

Carbon dioxide Nitrogen (27%)

Carbon Monoxide (16%) Water (8%) Ethane (3-5%)

INERT RO

GUN

0-200 Hz 10-300 Hz 100-2000 Hz

LIVE BOMB PRACTICE BOMB

MACHINE

AMMUNTION

Long-term exposure to low frequency noise (LFN) (<500 Hz, including infrasound) can lead to the development of vibroacoustic disease (VAD). Thickening of cardiac structures (i.e pericardium) is an indicator of the cumulative amount of LFN-exposure.

Vieques natives are 8x more likely to die of cardiovascular disease and 7x more likely to die of diabetes than natives of PR mainland.

The risk of dying from cancer on Vieques is 1.39x higher than on the PR mainland.

In 1997, the Vieques general mortality rate was 47% higher than the mainland’s mortality rate.

5-20 Hz

0-200 Hz

<3 Hz

Ammonia, Hydrogen Methane, Methyl-Alcohol, and Formaldehyde, Acetylene,Ethylene,an (<1%-2)

White Phosphorous, Thermite, RDX, sulfur, potassium chlorate, and sodium bicarbonate, refined kerosene, tricalcium phosphate

SOLID_ Ammonium Nitrate, Ammonium Dinitramide, Ammonium Perchlorate, Potassium Nitrate Octogen, RDX, Aluminium, Beryllium

LIQUID_ Dinitrogen Tetroxide, Hydrazine, MMH, UDMH

(Super)Natural | 93

gasoline thermite carbon dioxide

ROCKET

Napalm

ROCKET

INCENDIARY BOMB GRENADE

1 2 6 3 9 12 13 8 5 7 10 11 4 15 14

SPECIAL THANKS

We would like to express our gratitude to everyone who has made a contribution.

Aaron Betsky

Aaron Koopal

Arden Stapella1

Aidan Andrews2

Amanda Lopes Altelino

Amani Taleb3

Bayleigh Hudson

Cameron Campell

Connor Shanahan4

Cruz Garcia

Daniel Leira5

Doug Spencer

Finn Digman

Gabriela Robles-Muñoz

Gabriella Saholt6

Grace Morhardt7

Izzy Witten8

Joshua Stein

Ka Heun Hyun

Meredith Petellin9

Mircea Ionuț Năstase10

Nathalie Frankowski

Nick Cheung11

Peter Zuroweste

Shelby Doyle

Sierra Wroolie12

Sophi Allen13

Sophia Maguiña14

Timothy Zhang15

DATUM is a medium for critical academic discourse through the exchange of bold design and progressive ideas. As a student-run publication, we are grateful to print local at Heuss Printing Inc. and thankful to the Iowa State Student Organizations for their continual support. We would also like to thank previous donors for providing the funds to get us to where we are today. Donors have no influence on, or involvement with the work selected for the publication.

(Super)Natural | 95

Based on the short story by Raymond Carver.

Based on the short story by Raymond Carver.