Maya Wiley ‘86 on Reimagining America

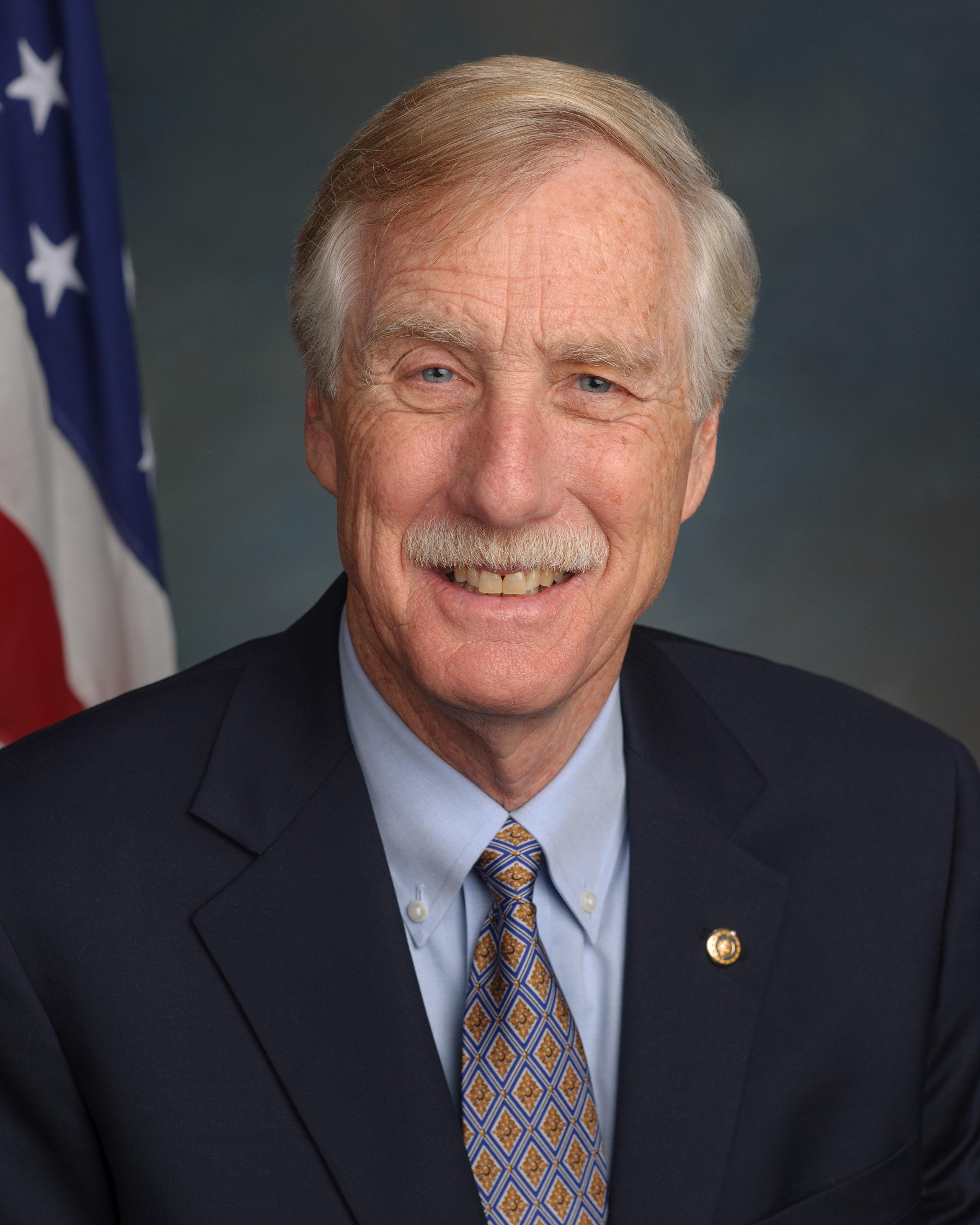

Senator Angus King Jr. ‘66 on Public Service

David Brooks on the State of Higher Education

Maya Wiley ‘86 on Reimagining America

Senator Angus King Jr. ‘66 on Public Service

David Brooks on the State of Higher Education

It is with pride and gratitude that we celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Dartmouth Center for Social Impact and this commemorative volume of the Dartmouth Social Impact Review. At this important milestone, we joyfully celebrate the remarkably dedicated community of faculty, staff, alumni, students, and partners who advance our mission to educate Dartmouth students to be transformative leaders for the common good.

Since its founding in 2015, emerging from the legacy of the William Jewett Tucker Foundation, DCSI has become a bold catalyst for creating sustainable, thriving, and just communities. Through DCSI, Dartmouth students learn alongside faculty and community leaders, broaden their horizons through alumni mentorship, and develop the skills needed to create effective and lasting change. Dartmouth has always sought to make a meaningful impact on the world, and DCSI has honored and advanced that community-wide goal by:

• Creating the Social Impact Practicum, a classroom-based program where liberal arts education meets real-world challenges within our local community.

• Launching leadership development initiatives which ground students in systems thinking and foundational skills in changemaking.

• Elevating awareness and opportunities for impact careers through robust alumni and global community networks and mentoring.

• Focusing local efforts to support public education and youth, engaging aspiring educators, and strengthening community ties.

Our success has been fueled by many partners who generously share a wide array of tools needed to make change through perseverance, innovation, creativity, and empathy. From business to the environment, inside and outside the classroom, and in our own backyards and across the globe, the Dartmouth community brings a wealth of talent to our most pressing social challenges.

Our work is far from over. The complex and acute challenges facing our communities—local and global—call upon us to sustain our efforts and intensify our commitment. Looking forward to the next 10 years, DCSI will deepen the connections between scholarship and real-world applications through community-engaged learning and research, foster vibrant networks on and off campus to support student pursuits of impact careers, and build enduring communities of practice among students, faculty, alumni and the community. In all these ways and more, we will ensure that future generations of Dartmouth graduates are fully prepared and motivated to work toward the common good.

This, our tenth birthday, is both a moment to reflect on a decade of progress and a chance to rededicate ourselves— our energy, passion, and skills—to the essential work of building strong, equitable communities. After you turn these pages, I hope you will help us open our next chapter as we continue to educate Dartmouth leaders dedicated to building a more just, livable, and compassionate world.

Tracy Dustin-Eichler, Director, Dartmouth Center for Social Impact

Since 2015, the Dartmouth Center for Social Impact has become a launchpad for thousands of students committed to building more just and livable communities.

Over this past decade, they’ve paired rigorous learning with real-world practice by embedding community-centered projects into the curriculum, enabling impactful internships, and building connections between students and our incredible alumni network.

Through DCSI, students learn not only what they, with their unique talents and perspectives, might contribute to the common good but how to do so in a way that centers community, honors difference and drives lasting change.

The work is interdisciplinary, experiential, and, like other key institutional efforts, grounded in the local community our campus calls home.

I am immensely proud of DCSI’s contributions to Dartmouth and society more broadly. As dean of the newly instituted School of Arts and Sciences, I congratulate them on 10 years of meaningful progress and look forward to the next decade of innovation and impact.

- Nina Pavcnik, Interim Dean, School of Arts & Sciences

Humans of the Upper Valley, inspired by the popular photo blog “Humans of New York,” is an initiative led by Associate Professor of Sociology Emily Walton and managed by a team of dedicated Dartmouth students. It aims to tell the stories of the wonderful and diverse community that surrounds campus – known as the “Upper Valley” – and build connections between students and local residents.

Emily Walton is an associate professor of sociology at Dartmouth College. Her research applies a racial lens to health and community sociology. Her forthcoming book, "Homesick: Race and Exclusion in Rural New England," is set for publication in November 2025.

The Irving Institute’s Energy Justice Clinic brings together students and faculty to support Upper Valley communities facing energy insecurity, highlighting the difficult choices residents make between essentials like food and energy. Through partnerships with local groups such as LISTEN Community Services and the Lebanon Energy Advisory Committee, student leaders and faculty conduct surveys and interviews to capture the real experiences of those burdened by energy costs. Their collaborative research not only uncovers critical challenges but also amplifies community voices, driving practical solutions that enhance health, resilience and well-being for the common good.

Welcome to this first (and perhaps only) edition of the Dartmouth Social Impact Review.

I say “only” because this publication is, at present, the manifestation of an ad hoc opportunity, coinciding with the 10th anniversary celebration of the Dartmouth Center for Social Impact (DCSI), and being printed in honor of it.

Tellingly, I write to you not in the formal role of magazine editor but as the assistant director of the DCSI, where I mostly oversee programs, not publications.

I make this prelude less to excuse any editorial shortcomings (though I do ask for forgiveness on that front) but to confess that our ambitions for this magazine started out a bit more modestly than where they ended.

Our initial hope was to curate a space that could exhibit the stories of social action and impact springing from our Center and the Dartmouth community.

Though we found no shortage of inspiring cases for the genuine, positive social change being driven by our community, we also found ourselves bumping up against a larger and more complicated conversation, of which these stories would inevitably come to be just one part.

This conversation, unfolding not just in op-eds or atop the ivory tower, but at kitchen tables and town halls, centers around a deep, society-wide critique of higher education itself.

From political and economic leaders of all stripes, to the communities that surround these institutions, and to the students attending these institutions themselves, we seem to be asking, as Americans, if higher education (especially of the elite, ivy-clad variety) is actually a driver of social good in our country, and the world more broadly.

While our answer is ultimately “yes," we certainly should not ignore the sweeping, multifaceted, and legitimate criticisms directed at institutions such as ours.

So, besides showcasing the community-centered values and public service DCSI has embodied over the past decade, we felt called to take up the challenge of speaking to these criticisms in our publication.

To that end, we begin this issue in conversation with renowned columnist David Brooks, whose critiques of higher education and elitism—most notably 'How the Ivy League Broke America' in The Atlantic, Dec. 2024— help frame our discussion.

From this interrogation of the system as it currently stands, each subsequent section will move through an answer of sorts to the question “Are We Educating for the Common Good?” by speaking to how the Dartmouth community is seeking to do so.

We begin by showcasing what educating for the common good has looked like for us, the Dartmouth Center for Social Impact.

Then, we turn outward to hear from Dartmouth alumni who have leveraged their education for the common good in various ways, especially within the education sector itself.

Finally, we invite readers to explore ideas and perspectives from the Dartmouth community that address some of the greatest challenges of our time—insights rooted in the collective knowledge and experience a good education should impart.

We forward these “answers” not seeking exoneration from criticism, but as prompts for what we educators might be getting right, and where we are still falling short.

In moving through this narrative, we hope to inspire a genuine, productive dialogue around the purpose and practice of higher education, ideally leading to a more definitive, shared understanding of what “educating for the common good” can and should look like.

Henry Do Rosario, Assistant Director, Dartmouth Center for Social Impact

Henry Do Rosario, Editor-in-Chief

Warren

Valdmanis, Contributing Editor

Charlotte Albright, Managing Editor

Cass North, Creative Director

Sabrina Chu, Editorial Assistant

Emma Hwang, Cover Illustrator

Yawen Xue and Angela Shang, Illustrators

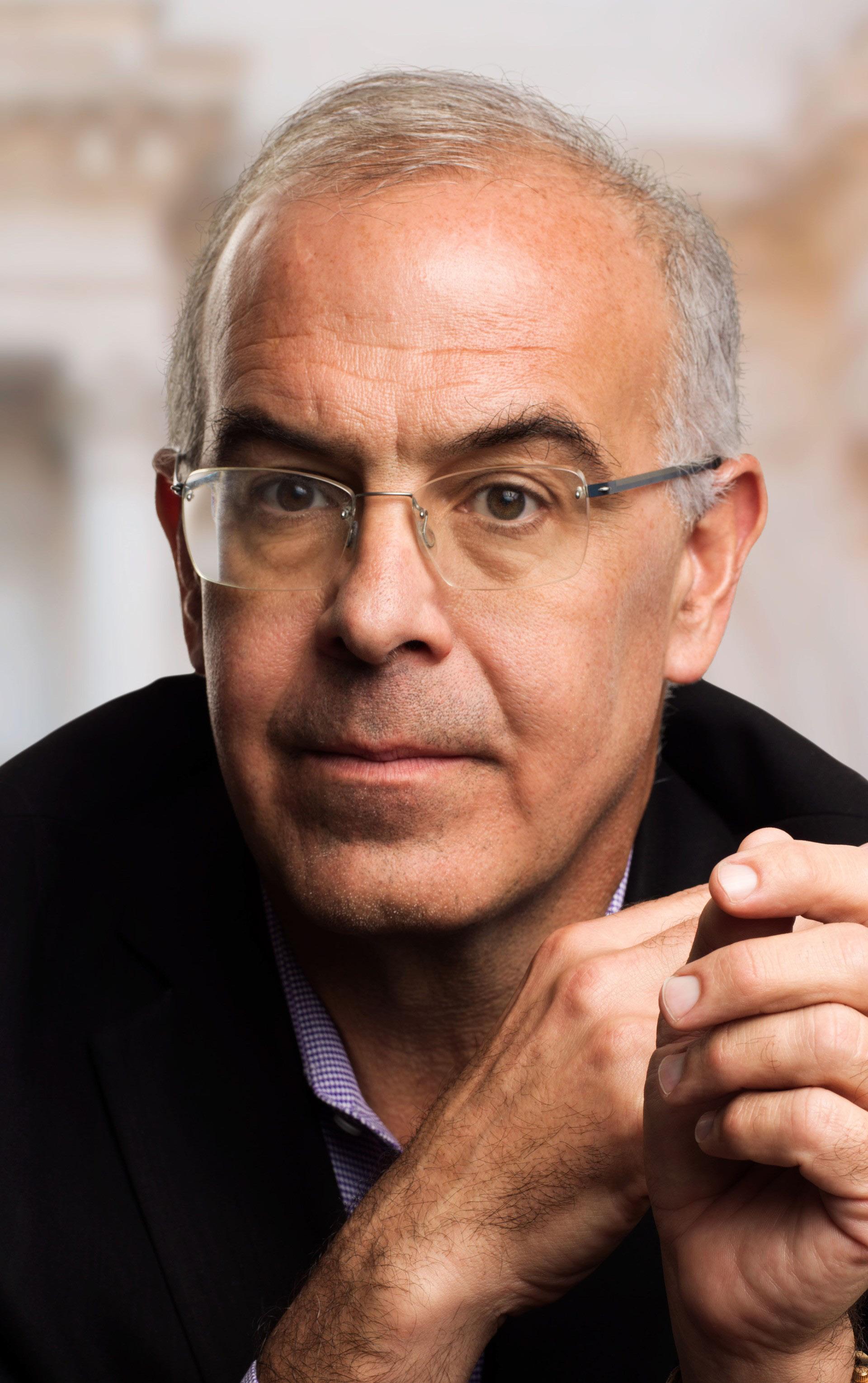

David Brooks in conversation with Warren Valdmanis '95

Read David Brooks' piece "How the Ivy League Broke America" in The Atlantic here. This conversation has been edited for length.

Warren Valdmanis: Your recent Atlantic essay, “How the Ivy League Broke America,” struck a nerve across higher education. What motivated the writing of this essay?

David Brooks: One of the odd things that's happened in American politics is that it used to be that you could tell how somebody voted by their income. Rich people voted Republican and poor people voted for Democrats. And that's no longer true. You can't predict anything by income. But you can predict phenomenally well by education levels. College educated people vote for Democrats and high school educated people are much more likely to vote for Republicans. And that's not the only difference. College educated people live about 10 years longer. College educated people obviously make a lot more money. College educated people are much more likely to marry. College educated people are much less likely to have drug addictions, to commit suicide, to be obese.

So we have created a caste society, an inherited caste society, where families pass along their educational advantages down to their children. And this chasm, in my view, not only explains a lot of the polarization of our society, but it explains the rise of populism. Essentially 80 % of Americans or Europeans—because this is a Western phenomenon—are saying the top 20 % have too much cultural power, have too much financial power, too much political power, and we're going to flip the table. I just wanted to know, how did this come about?

Warren Valdmanis: The essay describes the unintended consequences of meritocracy, so I did a little research. Michael Young, a sociologist and politician, wrote in an essay called “The Rise of the Meritocracy” that, by the year 2033, the meritocrats will have all the power and the common people will have none. Should we have listened to Michael?

David Brooks: Yes, he understood where we were headed beautifully. I went back and read that novel before writing that Atlantic piece, and it's pretty accurate.

Warren Valdmanis: And so now this is an unintended

consequence, presumably, of meritocracy: a system that creates arrogance at the top and resentment at the bottom. You describe a system that has built-in hypocrisy where institutions and students preach equality but practice exclusivity.

David Brooks: Yes, if you go back to the 1920s, we had a different social ideal. We had a different view of what makes a talented person. That was not being smart. It was being well bred. And if your dad went to Harvard, your odds of getting into Harvard were 90 %. It really was the East Coast aristocracy, whether in the New England area or in Philadelphia or other places. And that's where they sent their kids for finishing school. And people actually thought at the time this was the way to run an elite, because these people were bred to know how to do public service. It was not totally stupid. When I look back at Franklin Roosevelt or Teddy Roosevelt or George H.W. Bush—they were not bad leaders. They were bred in a certain way. “We are the elite. We don't really deserve to be the elite. It's just the way it is in our bloodlines.” And so you have responsibility to the common good. But between the 1930s and 1950s, James Conant, who was president of Harvard, said we can't run a 20th century American society governed by the dimwitted blue blood heirs of the old Mayflower families. We need a better aristocracy. Conant was very much worried about oligarchy. He thought these families have too much power, they control all sorts of wealth, and so we need to democratize. So we changed the definition of what ability is. It was no longer the well-bred person. It was the intelligent person. Conant thought he was democratizing the admissions process, but in fact, he was really prioritizing the kids who came from families who could invest massively in them and turn them into the sorts of kids who could get into an Ivy League school.

Warren Valdmanis: Your article is called “How the Ivy League Broke America.” Can the Ivy League help fix America?

David Brooks: Well, first of all, that was not my favorite title, because I taught at Yale off and on for 20 years. I love going to Ivy League schools. I have friends there. I think the Ivy League can reform itself not only by changing admissions criteria, but by inculcating in its students a greater sense of social responsibility.

Warren Valdmanis: Speaking as someone who graduated from one of these schools with a boatload of debt, it seemed to me at the time, not only was there a prestige element, but there was also a reality. I was scared I wasn’t going to land on my feet. But one of the things that we try to do at the Dartmouth Center for Social Impact is to show folks that just because you may start your career in banking or consulting doesn't mean you can't bring purpose to your job. It doesn't mean you have to stay in that line of work exactly. So I started down that road but ended up in impact investing actually. There are many more paths now to find purpose, regardless of where you start out.

David Brooks: I don't really begrudge finance and consulting firms. They teach people how to think. And once they take that ability to another field, they can do tremendous good. The one thing I do resent about some of these firms is they prey on the insecurities of undergrads. So I met a young man at Williams several months ago who had a summer internship at Bain his sophomore year, and they offered him a job the summer of sophomore year and so he didn't have to go through the last couple years of college wondering what am I going to do? I think that's just exploiting the insecurities of the youth. He had no clue at that age. He's 19.

"I think the Ivy League can reform itself not only by changing admissions criteria, but by inculcating in its students a greater sense of social responsibility."

Warren Valdmanis: Do you think elite college admissions should be screening for more than just academic ability, IQ, SAT? Are there other things that they could be screening for? If so, how could they go about doing that?

David Brooks: All these Ivy League schools get so many applicants, they can pick from a lot of kids who are smart, and who are astoundingly talented. But the first screen, before they even look at your essay, is SAT scores and grades. And that's basically a proxy for IQ. But IQ is not the same as good judgment. IQ is not the same as what they call metacognition, the ability to look at your own ability, your own thinking process and then detect errors. IQ is not the same as social skills. IQ is not the same as being a good human being. IQ is not the same as kindness. Those soft skills, which are harder and more expensive to quantify, are to me the most important thing.

Warren Valdmanis: So if you could change one thing about the college admissions process today, what would it be?

David Brooks: I’d change the high schools so they're more involved in project-based learning, where you work in teams to produce projects together. That's what more workplaces are actually like. And I think we should make college admissions criteria much less IQ-based, much less rigorous. If you admit anybody from the top 20%, they're going to be fine at almost any school.

Warren Valdmanis: The way you described some of those projects is much like some of the projects that we do at the Dartmouth Center for Social Impact, where a lot of the community engagement work and the pedagogical work is fundamentally done by teams— often students, faculty, and folks at local organizations in the Upper Valley, working on real problems together.

Another thing you talk about is moral formation, moral ecologies. Philosophers throughout history, from Plato, through St. Augustine, through Nietzsche and Jung— they've talked about the body, mind, and soul, nourishing all three. Do you think colleges have abdicated their responsibility to work on the soul?

David Brooks: Absolutely. When the founders created this country, they realized human beings are wonderfully made but also broken. And so they decided that what was most important was moral formation. Moral formation is a fancy and pretentious phrase, but my best definition comes from the gospel of Ted Lasso, when he’s asked, “What's your goal for your football team FC Richmond?” He says, “My goal is not to win a championship. It's to help these young fellows become the best versions of themselves on and off the field.” That's what moral formation is. It's helping people restrain their selfishness. It's helping people treat each other with consideration in the complex circumstances of life, and it's helping people find a moral purpose in their lives, meaning in their life. That used to be job number one, not only for colleges, but for every single educational institution from K through whatever. But for some one reason or another, we have gone several generations without passing these skills down.

Warren Valdmanis: When I was at business school at an elite university, there was a lot of talk about leadership, but it was never clear to what end. I mean, there are lots of effective leaders who have morally ambiguous or even negative legacies.

David Brooks: We define leadership often as being all about optimization and effectiveness. And believe me, I love effectiveness. I rent a car; I want Avis to be effective. But there's a difference between the utilitarian lens and the moral lens. And when you walk into a room, you can either put on one lens or the other.

Warren Valdmanis: The president of Dartmouth, Sian Beilock, has said the goal of Dartmouth is to teach students how to think, not what to think. Understanding that’s just one goal she outlined, do you think that's enough?

David Brooks: No, because life is more than about thinking. The distinction we make between the brain and the body, reason and the emotions—these are bogus distinctions. A lot of the mistakes we make are because of what I call cognitivism: overemphasis on cognition and underemphasis on affect, which is our emotion, and conation, which is our motivation. If we're just training people to think and not what to want, then we're leaving students unguided about where they should direct their lives and unguided in where they should bring their motivation and energy to life.

Warren Valdmanis: At the Dartmouth Center for Social Impact, we've got a mission to educate transformative leaders for the common good. And we seek to fulfill that

mission through a combination of initiatives like imbuing community engagement into the pedagogy through partnerships with faculty. We also send students on an immersive trip to the border—all kinds of ways of exposing them to relevant issues and getting them more oriented towards purpose. What other suggestions do you have for us?

David Brooks: I would say in the schools where I do teach, so many students come from the most affluent 20% that they really are strangers to working class kids from Bismarck, North Dakota, for example. To create cross-class experience strikes me as completely necessary. The second thing that comes to mind is it's very easy to use public service as a patch over moral formation. It's very possible to spend your life working for the Salvation Army or UNICEF or whatever noble organization and still be a rotten human being. Moral formation is not only what do you do, but how do you care? How do you empathize? Moral formation is really a process of transforming the inner self. The inner capacity to be loving is different from serving food to the homeless, as noble as that is.

"Moral formation is not only what do you do, but how do you care? How do you empathize? Moral formation is really a process of transforming the inner self."

Warren Valdmanis: At DCSI, we are doing the equivalent of serving food to the homeless while also encouraging the reflection that would lead to moral formation. It is interesting that our center grew out of the Tucker Foundation, which was religiously-focused, but we are not. And I think many students today see colleges as a secular place. So how do you actually encourage moral formation with that backdrop?

David Brooks: The first thing is to take the great books of moral philosophy seriously. My faculty at Chicago burned with enthusiasm. They thought if you read Hobbes, Aquinas, Augustine, Plato, Aristotle's Ethics, with care and intensity, you will know how to live. And that totally rubbed off on all of us. Second, you hold up exemplars. We tell students today—and this is the worst thing we tell students—come up with your own values. Come up with your own truth. If your name is Aristotle, maybe you can come up with your own value system. Most of us can't do it. But if you take those four years in college or in grad school and say, you are the lucky inheritor of a whole bunch of moral traditions—stoicism, Epicureanism, Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, rationalism—try them out. See which one fits you. Then you'll have a world view, and you'll have criteria to judge

right from wrong. Another thing that faculty can do is embody a certain way of being. Small gestures of consideration, of respect, of tolerance, of difference—you pick up on those small gestures.

Warren Valdmanis: I want to talk a little bit about the students and what they can do. You’ve said that Ivy League student cultures are built around keeping your options open and a fear of missing out, and that we live in a society filled with decommitment devices. What can students do to counter that?

David Brooks: The first thing they can do is understand that over the next 20 years of their life, they're probably going to make four big commitments. They're going to make a commitment to a vocation. They're going to make a commitment—probably—to some sort of family structure. They're going to make a commitment to a community where they want to live. And they're going to make a commitment to a philosophy or faith, what they're going to believe. And so making those four big commitments is really going to determine largely how your life goes.

Warren Valdmanis: Let's bring this down to the individual level. You spent a career interviewing and observing purposeful people. What distinguishes those who can sustain that over time?

David Brooks: Let me go back to the people I found who are the most purposeful. I started an organization in 2017 called Weave: The Social Fabric Project. It was based on the idea that a lot of our problems are caused by social distrust. People don't trust each other. This problem is being solved at the local level by people we call Weavers, who are active in the neighborhoods where they live. And some of them have big formal organizations. There's one called Thread, an organization where they surround the underperforming kids in the Baltimore school system with networks of volunteers who basically serve as extended family. But some of the people who are Weavers have no formal organization. Whether they're organized, part of an organized nonprofit, or just active in their community, they're driven by moral motivations.

One of the things I've learned about these Weavers is, you would think if you're working as a corporate lawyer working 90 hours a week, you were really prone to burning out. And of course, maybe you are. But if you are working to save your community, you're working 100 hours a week. And that's where the burnout really is most dangerous. It was a surprise to me that the people doing the most altruistic work have the strongest ambition, and actually, they need to do more self-care than the rest of us because they put pressure on themselves.

Warren Valdmanis: Do you think that AI and other technological advances have changed the way people interact and develop a moral orientation?

David Brooks: I use AI every day. I'm not down on AI, but it will not sit with the widow. When somebody is depressed, AI may offer the simulation of a relationship. I don't think it's going to do some of these jobs. I think it's pretty great at cognition. But I don't think AI is going to have motivation. I don't think it's going to have imagination. I don't think it's going to have empathy. And so I still think there will be some skills, which may not be cognitive skills, but other skills that we will rely on even more. There are just basic human interactions—falling in love, having a dream, having an ideal—that AI is not going to be able to do, and those will become super important for humans. That'll be our decisive advantage.

Warren Valdmanis: You've been candid about your own journey from careerism to what you've called “second mountain living.” How does that experience shape your view of universities?

David Brooks: Well, first of all, they should be lifelong. In the last couple of years, I've been teaching a course for people over 65 who are trying to figure out the rest of their lives. They're retiring. They probably have 20 or 30 vital years. Another thing universities can do is to narrow the chasm between town and gown. We need to make it so that people in the community don't only feel invested in the sports teams of the university but the everyday life at the university. And that's proving to be a challenge. You can send kids out to the neighborhood. How do you get the neighborhood to come onto campus?

Because there are a lot of people in all these towns who look at Columbia University, Harvard University, and think, that's a very forbidding place. I am not going there. We've created these chasms. And that's maybe just inherent because town-gown conflicts have been going on since the Middle Ages. But somehow that needs to be addressed if we're going to get out of this era of populism, where people just not only hate the universities, they come to hate knowledge.

"It's helping people treat each other with consideration in the complex circumstances of life, and it's helping people find a moral purpose in their lives, meaning in their life."

Warren Valdmanis: David, we've talked about how the Ivy League broke America. We’ve talked about political divide and many other issues. Yet through all of this you describe yourself as an optimist. What fuels your optimism in these challenging times?

David Brooks: History. I read a lot of history. And I ask people, if you're depressed now, what decade do you want to go back to? Like the 1930s? Was the Depression so rosy?

But when I ask people who made you the person you are today, no one ever says, “I had this fantastic vacation in Hawaii.” They always point to some hard time, and they got through it. And I think we grow, as people and as a society, through a process of rupture and repair. Right now, we're in a period of rupture. It’s brutal to live through this period, especially if you're a scientist at NIH, or if you're a researcher at Harvard, or any of these schools. All the personal assassination, all the nastiness. But human beings are tremendous at innovation. And culture shifts when a problem arises, and the whole of society pivots. I think we're in the middle of this kind of pivot. We went through 60 years of a very individualistic culture and we're now trying to find our way to community. You could define the current moment as this big brawl over what kind of community we want to have. You might like MAGA or not like MAGA, but it is a form of community. You may like the social justice movement or not. It's a form of community. And so, we're having a fight over what kind of community we want to return to. We've got to return to some more communal thing, where we think about our social impact.

Warren Valdmanis: David Brooks, thank you so much.

David Brooks is a longtime New York Times columnist and a commentator on PBS NewsHour, where he provides political and cultural analysis. He is the bestselling author of The Road to Character, The Second Mountain, and How to Know a Person. Through his journalism and books, he explores morality, community, and the pursuit of a meaningful life.

Listen to the full conversation here or look up "All the Difference" wherever you get your podcasts

Since its inception in 2015, the Dartmouth Center for Social Impact has served as a powerful catalyst for creating sustainable, thriving, and just communities the world over. Our primary means of doing so has been a suite of rich, immersive, and diverse experiential learning programs that place students at the forefront of local and global changemaking.

Though the constellations vary, the guiding star of these programs is that they seek to educate students to be transformative leaders for the common good. After a decade of progress, we’ve honed in on a few key elements of our practice that have been most essential for driving the growth and learning that helps develop students into these transformative leaders—connecting the curriculum to real societal needs, grounding students in authentic partnership with the communities they seek to empower, and embedding them on the frontlines of change.

We begin this section with a thoughtful piece from Associate Professor of Religion Devin Singh. In it, he speaks to what may be driving today’s students towards moral action in a more secular age from the heyday of the religiously centered Tucker Foundation (from which DCSI branched out). The stories that follow map how different DCSI programs have shaped students and their trajectories, enabling them to tackle global issues through local action with support from forward-thinking faculty.

By Devin Singh

Earlier this year, I enjoyed an engaging lunch at the Hanover Inn's Pine Restaurant with two students, one a committed believer and the other an avowed atheist. They had invited me to mediate their spirited yet friendly debate: “Do you need religion to live a moral life?” It’s one of those enduring questions of our modern age. What drives people to do good in a world where traditional religious imperatives, once deemed central to ethical responsibility, no longer hold sway?

The Dartmouth Center for Social Impact supports students who are passionate about making a difference, but the motivations behind that passion are far from uniform. Some arrive with deep commitments grounded in faith. Others bring a strong ethical vision shaped outside any religious framework. Still others stand somewhere in between, influenced by inherited traditions but uncertain about their personal beliefs.

While some students with strong religious convictions explore service through the religious communities and chaplaincy initiatives supported by the Tucker Center, many others pursue their social action work through DCSI. But the relationship between these centers is complementary, not oppositional. Religious students often design projects through DCSI, and secular students sometimes find themselves drawn into Tucker-supported initiatives. This overlap reflects the deeper reality: there is no simple mapping of religious and secular motivations onto institutional structures, let alone onto the nature of the service projects with which students engage.

That complexity mirrors the pluralism of our broader society. The question it prompts among many has implications beyond Dartmouth: if religious commitment is no longer the dominant framework for social service and moral leadership, what takes its place? Now, I’m not sure I agree with the underlying assumption that there was ever a unified religious framework in the past or that it clearly drove social action. Still, the notion is common enough that it’s worth taking seriously.

One response can be found in the language of care. Ethics of care, a moral framework developed over recent decades, argues that morality arises from our relationships—our mutual dependencies, our vulnerabilities, our obligations to others. Rather than begin with abstract rules or universal duties, this approach starts with attention to concrete people in particular situations. It emphasizes empathy, responsiveness, and the moral significance of encounter and relational bonds. Many Dartmouth students

speak in this register, whether they use philosophical terms or not. They describe being moved to act by someone’s story. They express a desire “to be there” for communities they’ve come to know, the groups they’ve joined and senses of fidelity they’ve kindled. Their motivations reflect a moral imagination shaped less by rules and more by connection.

Another framework is virtue ethics. Originating in ancient philosophy but resonant today, virtue ethics focuses on character and the cultivation of moral habits. It asks not simply "What should I do?" but "What kind of person am I becoming?" For students at Dartmouth, this process of moral development often happens implicitly, whether through the communities they inhabit, the mentors they encounter, or the intellectual traditions in which they engage. Even those who do not identify with any religious tradition are nonetheless shaped by moral narratives: the stories they hear, the values their families uphold, the peer cultures they inhabit.

Here, the liberal arts—the humanities, in particular—play a vital role. In studying literature, history, philosophy, religion, and the arts, students cultivate capacities essential for moral leadership: empathy, critical reflection, ethical imagination, and the ability to hold multiple perspectives in tension. These disciplines do more than transmit knowledge; they form people. They invite students to consider not only what is true, but what is just, meaningful, and worth striving for. In a time when ethical foundations can feel unstable, the humanities offer a space to wrestle with enduring questions of purpose, responsibility, and care.

While reflection is critical, action is key. More than this, critical reflection on action—on praxis—emerges as essential. Praxis emphasizes that we come to understand the world not only through contemplation, but through participation. Working with a mutual aid organization, tutoring a child in a nearby school, organizing for environmental justice—these are not only acts of service; they are experiences that shape one’s worldview. They generate insight. They reorient assumptions. They can transform identity and values.

This view aligns with traditions of thought that see solidarity with marginalized communities not simply as ethical obligation, but as a way of knowing. While this idea has roots in liberation theology, it does not require religious belief. It simply affirms that lived experience and moral commitment are sources of knowledge, not just sentiment.

Importantly, the motivations that drive students to serve do not always fit into tidy categories. Some are driven by ideals of justice, others by compassion. Some see their work as a response to structural inequality; others are motivated by personal relationships. The diversity of motivations is a strength. What matters is that institutions like Dartmouth create spaces where those motivations can be explored, deepened, and translated into thoughtful action.

That exploration also includes wrestling with discomfort. Many students express frustration or disorientation as they confront injustice or their own complicity in systems of privilege. Others wonder whether their work is truly effective or if their motivations are "good enough." These struggles are not signs of failure but rather moral growth and deepening wisdom. By supporting students through these tensions, we can help them build the resilience and clarity needed for long-term engagement.

In short, DCSI and the broader Dartmouth ecosystem provide more than opportunities to serve. They provide opportunities to ask why service matters and how it changes us. In a time when easy answers are abundant but increasingly suspect, this deeper inquiry is essential. And in a liberal arts context, where questions of value, identity, and responsibility are central, it is also profoundly appropriate.

So, if religion no longer functions as a primary motivator for doing good, what takes its place? The answer is not singular. It likely never was, despite what proponents of tradition might claim. Motivations for service are as diverse as the students who walk through DCSI’s doors. But whether rooted in care, character, justice, or community, these motivations are real. They are shaped by experience and tradition, nurtured by relationships and reflection, and refined through action. They form the basis for the kind of moral leadership our world so urgently needs.

Devin Singh is an associate professor of religion, teaching social ethics and market morality, and serves on DCSI’s Lewin Fellowship review committee.

By Erich Osterberg

I was brought onto Dartmouth’s faculty to study climate science—to track the relentless rise of temperatures, the surge of storms, and the creeping threat of rising seas in the polar regions and in my own New England backyard. My students and I drilled ice cores like forensic scientists and combed through weather data to reveal the unfolding story of a planet in crisis. At its core, my job was to discover and deliver the sobering science: diagnosing climate change and communicating its urgency to the world.

But something shifted fundamentally in how I saw the world. The years 2016 and 2017 shattered global temperature records—shocking jumps that spoke louder than the UN climate reports. The following year, two

graduate students in my lab, working on seemingly unrelated projects, independently identified 1996 as a critical turning point. One was tracking the acceleration of Greenland’s ice melt; the other, the surge of heavy rainstorms flooding New England communities. The connection was undeniable—the same processes melting the Arctic are fueling the floods in our streets. August 2018 became New Hampshire’s wettest month on record, drenching communities with unprecedented rainfall. That’s when I realized that studying the disaster wasn’t enough. I needed to evolve from diagnosing climate problems to building solutions.

At the same time, higher education was entering a moment of reckoning. In an age where billions of facts, instant answers, and AI-generated content are at our fingertips, what, really, is the purpose of a university education? If knowledge is cheap and instantly accessible, the value of higher education must shift from passive consumption to active engagement. We need to pull students out of our ivory towers and immerse them in the realities outside the Dartmouth bubble. They must be challenged to collaborate with people who see the world differently and to tackle messy, seemingly unsolvable problems whose outcomes matter to someone other than a professor with a red pen.

My first steps down this new path came through the DCSI Social Impact Practicum. Years earlier, I had joined the Upper Valley Climate Adaptation Workgroup (UVAW)— not as “Professor Osterberg,” but as a community member ready to get things done. UVAW brings together state and municipal leaders, business leaders, nonprofits, social workers, and researchers—anyone committed to making our region climate-resilient. Starting in 2018, UVAW partnered with Dartmouth students through ten different SIP projects: surveying urgent community needs, securing funding, developing branding, organizing neighborhood meetings, and even building a carbon footprint app. Suddenly, education wasn’t just theory, it was providing real impact for an organization I valued.

Building on this momentum—and inspired by Professor Eugene Korsunskiy’s “Senior Design Challenge” course— my colleague Carl Renshaw and I launched “Community Partnerships for Climate Resilience,” a two-term transformative experience for Dartmouth students. Supported by the Climate Futures Initiative, the course was designed to serve as a proving ground for meaningful student engagement with the community. We received 13 project proposals from across the Upper Valley and selected four community partners for our student teams:

- Storing sunshine on a ski hill. With the Lyme Energy Committee, students explored converting Dartmouth’s Skiway into a pumped-storage hydropower battery—pumping water uphill when solar energy is abundant, then releasing it to generate power at night. This isn’t science fiction; it’s a practical, tangible clean energy storage solution built around infrastructure we already have.

-A safer future for a flood-prone neighborhood. Together with Sustainable Woodstock, students suppor ted residents of a mobile home community repeatedly flooded by back-to-back storms. Their actionable plan examined a range of solutions from partial relocation and river eng ineering to temporary flood protections, balancing hard science with the humanity of a community under siege.

-Growing resilience, one tree at a time. Working with Upper Valley Apple Core, students helped secure g rants and refine the strategic plan for a nonprofit that plants fr uit and nut trees in public spaces. Their key insight: beyond carbon sequestration and local food production, these trees foster social connections as neighbor s gather to plant, maintain, and har vest together.

-Mapping r isk to protect jobs and ecosystems. Partnering with Hypertherm, a certified B Corp, students assessed flood r isks at a warehouse, developed flood models, and uncovered how a historic stone-arch br idge complicates the picture. Their work didn’t just identify hazards—it demonstrated how existing floodplains provide cr ucial protection for downstream communities.

When students presented their findings to community partners and campus leaders, the verdict was unanimous: rigorous, valuable, and transformative for both students and community partners. This is a model of higher education working for both students and the broader community.

Why does this matter? Because this is about far more than Dartmouth. It’s a blueprint for what climate education must become when fake facts and instant data are everywhere. In this era, the true challenge for students is not regurgitating answers—it’s mastering the human work of listening, building trust, squaring trade-offs, and developing solutions whose stakes are real and immediate. This is education no AI chatbot can replicate.

Erich Osterberg is one of dozens of faculty members that have partnered with DCSI to embed a community based project in their course. These Social Impact Practicums support students in connecting classroom theory with real world impact - a strategic priority area for DCSI.

By Nico D'Orazio '28

On a beautiful fall afternoon, I walked onto the Green with Collis stir-fry in hand, searching for the perfect picnic spot with friends. Looking around from the center, our campus extended as far as the eye could see, embracing me with its magnetism. For better or for worse, my early college life unfolded inside the Dartmouth Bubble, and my learning, growth, and ambitions became inspired by Dartmouth experiences alone.

That all changed when, as a freshman, I discovered TEACH, an immersive program run by the Center for Social Impact that places Dartmouth students in a local elementary school classroom to assist teachers. When I first stepped into Mrs. Miller’s first-grade class at Dothan Brook School in Hartford, Vt., my Dartmouth Bubble burst. My students did not care about what I was studying or which classes I was taking. Instead, they cared about a sick grandparent or their pets at home. Though I was only two miles away from campus, it felt as if I had stepped into a whole new world.

On my first day, I was struck by how distinctly the challenges of teaching in a rural school system differed from those I saw at home. Mrs. Miller’s class reminded me how easily Dartmouth can blind you to the outside world, and this reminder only magnified each week I returned to her class. As we worked through phonics and my students slowly learned to read and write, I saw how they struggled to grasp even simple concepts. Their profound daily struggles took me far from my own college classroom experiences. My one hour at Dothan Brook became the most important part of my week. It didn’t matter if I had to skip breakfast and run straight from spin class to make my shift. What mattered was whether my students understood how the letter 'e' can change a vowel’s sound, and whether the child who had a challenging home life had the support they needed to learn. No lecture could teach me how difficult and personal literacy education can be for early learners.

Yet, because of the intense difficulty of teaching a child how to read, the small successes were incredibly gratifying. I distinctly remember when a boy we'll call Michael finally grasped 'c' versus 'k', or when a girl we'll call Clara made it through her favorite book without my help. Being a partner in Mrs. Miller’s efforts was a privilege, and I gained a deep sense of responsibility for her students. Skipping or being late to a shift was not an option because if I wasn’t there, her students lost the support they depended on.

As a prospective government and Spanish major, my commitment to TEACH and my students at Dothan Brook amplify my “why.” Mrs. Miller’s class reminds me of the human side of policy, making my studies in government that much more important, and her students are reminiscent of the English language learners back home who inspired me to continue studying Spanish. As I join her class each week, I consider policy interventions, career paths, and ways I can make even the smallest difference. My students drive me to use my education for the common good, and I view TEACH as a proving ground where classes like Educational Testing, Politics of the World, and Spanish 20 can come together and inform my understanding of policy. Every day I enter Mrs. Miller’s first-grade classroom, I am allowed the unique opportunity to turn theory into practice.

I could not be more thankful for my time in TEACH because, in bringing humanity to my studies, I am exploring fields I had never imagined before. This past summer, I interned at the National Head Start Association to grow my knowledge of early childhood education. My experience in Mrs. Miller’s class led me to pursue this experience, an opportunity to understand policy by learning directly from educators. And while I may not become a teacher, I hope for a career that provides the same sense of purpose, connection, and impact.

Although it is easy to get pulled into big-money jobs like investment banking and corporate law, I worry that without path or purpose, these careers waste our potential to have an impact on the world. The knowledge we gain from a prestigious institution like Dartmouth is a privilege. So, why not use it to benefit those most in need? Making service a part of my Dartmouth education has taught me that my passion lies in supporting our youngest learners.

What will it teach you?

Nico D’Orazio '28 is a teacher’s assistant at Dothan Brook School through TEACH. He also interned with the National Head Start Association in DC through the DPCS Internship program.

TEACH provides students with the opportunity to serve as teaching assistants in local schools. Participants gain hands-on experience in the field of education, while providing support to local educators and youth.

By Maanasi Shyno '23

This fall, I’ll be beginning my sixth year in college access work. My journey began as an adviser for Strengthening Educational Access with Dartmouth (SEAD), which laid the foundation for my relational approach to community work. SEAD gave me a community of peers with a deep sense of collective responsibility and ultimately inspired my commitment to educational equity.

After graduating, I joined a college access nonprofit in San Francisco, where I work with middle school students. Here are three philosophies I’ve come to value in my short career. 1.Act within an ecosystem.

When I got the assistant student director position for SEAD, I was troubled. I had assumed it would go to a first-gen adviser with lived experience. However, none of them had applied. Although I trusted myself to move into the role with respect and consideration, I worried my perspective as a non-first-gen student would limit my effectiveness.

While I didn’t easily dismiss this concern, I decided it should not hold me back. Yes, college access initiatives should have first-gen leaders. But those of us who aren’t first-gen should not discount our ability to listen, assess what is needed, and commit ourselves to the tasks at hand. Questioning "Who am I to do this?" may invite us to consider whether we are right for a role. But a more useful question is "Who am I doing this with?" Over time, I realized I wasn’t doing this work alone. I was constantly learning from my student director and eventually my own assistant student director, both of whom were first-gen. The advisers didn’t hold back on feedback, challenging me to weave their expertise into our curriculum. Every idea I proposed was shaped by the team’s diverse experiences and rooted in our solidarity.

2.Commit to making social change.

In his book of essays, "The Revolution Will Not Be Funded," violence prevention activist Paul Kivel asks, "Can we provide social service and work for social change, or do our efforts… maintain or even strengthen social inequality?"

This has been on my mind as I help launch a program at a new school. On one hand, I hold close the importance of depth over breadth when it comes to impact. On the other hand, I realize the work I do does not change the education system, which perpetuates inequity. Instead of encouraging school systems to directly integrate access support in community schools, nonprofits too often come in with stopgap solutions. For those of us brought into social impact work with a desire for change, the contradictions are endless. Over time, they grate on us. We sometimes ask ourselves, "What are we doing here, really?"

There are no perfect formulas or easy answers. We must constantly reflect on the outcomes of our work and

whether they align with a vision for social change. Kivel provides a series of questions for us to grapple with, a primary one being “Whom are you accountable to?”

Doing direct service work, I come face to face with the students I’m accountable to every day. My relationships with them push me to consider what I owe them, beyond the responsibilities of my job. To honor this, I’ve begun to intentionally study where the cracks in our education system are, and to imagine how we may begin to strategically repair them.

3. Invest time in community partnership.

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned in my time in education is that the strongest partnerships are reciprocal —that relationship-building is integral to our work.

My supervisor has modeled what this looks like in practice. He emphasizes the importance of showing up and supporting school events, especially those not related to our work. We attend awards ceremonies, gather at barbecues. Because of these efforts, our program is known for always helping out and chipping in. This knits us into the school community. Schools understand our work better and make extra efforts to support us. Partnership isn’t just built on the services we provide, but on how we build trust.

I'm learning to promote collaboration at the classroom level as well. With my second cohort, I struggled to cultivate an environment of active participation. I tried a variety of strategies with limited success. One day I stopped my lesson early to ask my class what was stopping them from participating and what would make it easier for them to do so. To my surprise, the students with whom I’d least successfully engaged expressed their fears and ideas the most clearly. Soon afterwards, I implemented their ideas in my practices and saw a vast change in classroom culture. I hadn’t needed to struggle so much to find what worked for the cohort. I just needed to invite them to work with me.

Community partnership is anchored in investment and requires a steady focus on time and resources. Tending to the soil in this way centers our relationships, because those are what fuel and shape the work we do together.

Maanasi Shyno '23 is an educator in college access in San Francisco. She was formerly the student director for DCSI’s Strengthening Educational Access with Dartmouth (SEAD) program and participated in DCSI’s Philadelphia internship cohort.

SEAD connects Dartmouth students as advisors to local low-income high school students, many of whom would be the first in their immediate family to attend college. SEAD advisors support these students in building the skills and knowledge needed to succeed during and after high school.

By Rafe Steinhauer

It's the first week of March. A kindergarten classroom sits empty of children but full of adults—teachers, administrators, and district staff gathered after school. For the past five months, a team of Dartmouth undergraduates and kindergarten teachers has studied the benefits of play for kindergarteners. The goal of the study has been to help stakeholders in this district better understand the link between play and learning. Now comes a pivotal moment. After sharing insights from this primary and secondary research, the team asks, "On a scale from '1 (not very)' to '5 (very),' how important is increasing our kindergarteners' play time in our schools?" After three minutes of nervous silence, the responses come in: one participant writes "4" and everyone else writes "5." The team has secured buy-in for change.

Interactions like this—Dartmouth students and local teachers working together to seek a district community's feedback—anchor the unusual Dartmouth undergraduate course I teach, Design and Education.

Why are gaps between theory and practice so persistent in American K-12 public schools, and what improvement strategies are both effective and ethical?

We explore these questions in my course through both theory and practice. Crucially, by "we" I mean not only me and Dartmouth students minoring in human-centered design or education, but also small teams of teachers and administrators from local public school districts working on year-long school improvement projects in the program I started, Upper Valley Education Design Clinic. Rather than the more common “client-consultant” model of service learning, our program uses what's known in legal education as the "clinic model." Each group of local teachers proposes the school-improvement project, comes to class several times to learn design thinking and systems thinking alongside Dartmouth students, and fully leads the project for a whole school year.

One team in last year's cohort sought to increase playtime for kindergarteners in their district. Although research shows that play supports both social-emotional growth and long-term academic success, the amount of time for play in kindergarten nationwide has dropped in recent decades. How might a college like Dartmouth help local kindergarten teachers shift their district's policy and practice —bucking national trends—to increase student play? To answer this question, we must concurrently examine why change is difficult in public education, and which improvement strategies work best. Three insights from scholarship on these questions informed our program's design.

Insight #1: "Power is Distributed, Therefore Co-Design."

In "Tinkering Toward Utopia," David Tyack and Larry Cuban examine failed movements to change American public school practices throughout the 20th century. They explain how the split governance of public schools creates a status quo bias: any major stakeholder group that's sufficiently opposed can block or significantly hinder change. School board members and administrators can enact mandates limiting classroom possibilities. Families can pressure against proposed changes. Teachers may choose not to implement directives they see as misguided or too onerous.

This is why our program prioritizes co-design. Together, district teams and undergraduate students learn design thinking—a human-centered approach to problem-solving that emphasizes understanding stakeholders and seeking their continual feedback. Co-design goes further, inviting stakeholders to collectively interpret insights from literature and community data, brainstorm interventions worth trying, and reflect on learnings from small-scale experiments. Throughout our program, the educators and undergraduates jointly run co-creation sessions: large gatherings of district staff, administrators, board members, families and—depending on age—students.

Through these co-creation sessions, as well as dozens of interviews primarily conducted by the undergraduates, the kindergarten team created broad community support. But co-design not only increases political viability; it also improves work quality by incorporating stakeholders’ knowledge and feedback. After confirming support, the kindergarten teachers and undergraduates next presented the most challenging barriers to implementation, such as the limited time teachers had for class prep, and the district's purchase of a costly but prescriptive curriculum. The team asked participants to brainstorm ways to overcome these barriers.

Insight #2: "Content and Context Matter, Therefore Educators Facilitate Improvement." Teachers, as well as many administrators and other building staff possess unique dual expertise. Formally trained, they understand curriculum, pedagogy, and child development. Through daily experience, they are most likely to know how proposed changes might impact their diverse students; how receptive colleagues are to experimentation, which school processes are more sacred than others; and much more. And as the deliverers of instruction, teachers and staff are typically the people who must implement proposed improvements. Thus, teachers and staff are best-positioned to facilitate the co-design process.

As Anthony Bryk and others show in "Learning to Improve" (Harvard Education Press, 2017), top-down reforms aimed at scaled standardizations typically fail because they neither account for local factors nor do they allocate resources for the experiment-learn-iterate cycles that effective implementation requires. The authors propose "Networked Improvement Communities," in which teachers, administrators, and staff leverage design thinking,

systems thinking, professional learning communities, and improvement science—a model that heavily influenced our program's design.

Once the kindergarten teachers created district-wide buy-in, they could immediately begin trying ways to incorporate play into their classroom, informed by the input of their community.

Insight #3: "Make Sessions Fun and Empowering." Teachers and administrators are extraordinarily busy. While our program offers stipends and professional development credits, these pale beside the reality that educators travel to Dartmouth after long school days and dedicate countless hours to these projects.

For the program to be sustainable, the experience must be fun, empowering, and intellectually stimulating in ways that increase educators' overall sense of satisfaction, agency, and efficacy. This is where liberal arts colleges like Dartmouth shine. Dartmouth undergraduates model joyful experimentation, collaborative inquiry, and genuine respect for practitioners' expertise. The undergraduates’ diverse academic backgrounds mirror the interdisciplinary nature of school improvement itself, while their curiosity helps educators see familiar challenges with fresh eyes.

This collaborative learning environment creates a professional development experience that the teachers describe as professionally invigorating. "The experience was thoroughly enjoyable," said Joshua Hunnewell, a middle school teacher on a team implementing restorative practices to replace traditional disciplinary approaches in Plainfield, NH. "I felt like a school kid again deeply involved in a process of brainstorming, creation, and critique with fellow educators and Dartmouth students."

Many teachers in our program report that the most valuable outcome was increased enthusiasm at work, born from collaborating in new ways with both district stakeholders and Dartmouth students. This is an exciting model for town-gown partnership—not just universities serving schools, but higher education and K-12 educators working as co-designers of change.

Editor's note: Steinhauer's course and program are made possible by support from Dartmouth’s Center for Social Impact, the Thayer School of Engineering, Dartmouth’s Center for Teaching and Learning, the Design Initiative at Dartmouth, Dartmouth’s Ethics Institute, and the Jack and Dorothy Byrne Foundation.

Rafe Steinhauer is an assistant professor of engineering who focuses on human-centered design and teaches a DCSI Social Impact Practicum in collaboration with local school districts.

By Abby Kambhampaty '25

I was a sophomore in high school when I first understood the true story of Interstate 81. My father drove me to school on it every morning through my diverse but segregated home town of Syracuse, N.Y. Construction of the I-81 through an economically thriving Black neighborhood allowed quick travel from the suburbs to the city, but the highway displaced Black residents, destroyed affordable housing, and locked immigrant communities into poor health and homelessness. I began viewing all the structures that shaped our community members’ lives and health care rights as metaphorical I-81s. My determination to tear down these structures has inspired how I’m pursuing my career in medicine.

The following year, every weekday at noon, I found myself on the I-81 again, this time in the driver's seat, taking my father to his radiation treatments. The daily drives became our therapy: a stitched-together language of Telugu and English filled the car with jokes and stories. On one drive, I asked him what was hardest about adjusting to life in America after being born and raised in India. He barely thought before answering: “I can’t be funny in English.” Humor was how my father and I said "I love you." In America, language barriers, cultural gaps, and a lack of community left him isolated in ways I had not fully seen. His experience ignited my resolve to dedicate my life to immigration advocacy, ensuring that dignity and belonging are fundamental rights for all.

I deepened my engagement with migration justice work in college. I joined and later led, alongside a DCSI staff member, Dartmouth’s Center for Social Impact program to the U.S.-Mexico border. I studied the forces shaping migration—topics that were never addressed in my pre-med courses, but essential to understanding health inequities. Amid this injustice I witnessed in the borderlands, I also encountered joy, resilience and community. It was here that I found my love for community organizing and for working alongside others to build systems rooted in care.

In 2022, I visited Team Brownsville’s border center as a sophomore participating in the border program. Team Brownsville was a bustling welcome hub, filled with community and hope, a first stop for people walking from the refugee camp in Matamoros in the Rio Grande Valley, Texas. When I returned in 2024, it was gone, shut down by a lack of funding. Resilient volunteers still drop off donations across the border in this patchwork of a crumbling system.

Yet, even amid these harsh realities, our group found a sense of lightness at the border. Leading up to a youth maker space workshop, in partnership with Sul Ross University, we spent weeks coordinating logistics, planning hands-on activities and rallying students to join. As the day

approached, we were unsure if the effort would resonate. When the day arrived, families poured in as children learned about water conservation and filtration techniques. Children’s laughter filled the air as they decorated recycled containers and playfully pretended to deliver weather reports from an imaginary newsroom. I discovered my love for community organizing as a way to educate and create spaces of joy and connection. This workshop was a testament to the strength, happiness and resilience of border communities, often overshadowed by stories of struggle.

These experiences shaped my perspectives and fueled the desire of many border-trip participants to pursue impactful careers and advocacy efforts. The trip has solidified my commitment to becoming a physician who serves refugees and underserved populations, working on the border or in similar contexts. I hope to use my future education and partnerships to explore sustainable ways to contribute to migration justice and health care access. Through this program, I also had the privilege of meeting some of my closest friends, each bringing unique perspectives from their diverse fields of study—from theater to environmental studies to computer science. Within these interdisciplinary connections, I envision future collaborations, combining our unique skills and passions to drive meaningful change in the areas of migration justice. Just as I-81 carved through my hometown and divided communities, immigration policies and violence continue to fracture lives at the border. Yet, in every space I have entered, I’ve witnessed that what survives beyond these man-made barriers is resilience, solidarity, and care. My hope is to help reimagine systems of care that no longer resemble highways cutting through communities, but bridges that connect them.

Currently, I’m working in community medicine at NYU Langone, where I provide clinical services to unhoused and undocumented patients across New York City. In our exam rooms, I see the same forces of exclusion and resilience I first witnessed in Syracuse and along I-81: language barriers, fractured systems of care, and communities left to navigate impossible choices. My work in HIV care and health literacy is rooted in what I learned from families, organizers, and children at the border—that advocacy must be both systemic and personal, dismantling barriers while also creating spaces of dignity and belonging. As I move forward in medicine, I remain committed to transforming clinics into places of connection and justice.

By María Clara de Greiff Lara

The starriest sky I ever saw was in Vermont. I can say the same about the greenest mountains, the warmest lakes in the fleeting summer, and the whitest snow. Here I learned that Vermont’s Green Mountains, part of the Appalachian chain, guard the secrets of the Abenaki, Mohican, and Pocomtuc tribes. These seemingly impenetrable walls also hide a resilient population of migrants from other nations on dairy farms, survivors of structural violence that drove them from their motherlands. Not seeing them is a way of denying their existence, of de-legitimizing them, of justifying our comfort zones.

They labor in oblivion, working more than 72 hours per week and accounting for approximately 70 percent of the state’s milk production. Without adult and teenaged migrants, the dairy industry in the Upper Valley would not survive. According to the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, dairy farming, which yields more than two billion pounds of milk each year, is the state’s largest agricultural industry, and about half the milk New Englanders consume is produced here.

Teaching at Dartmouth, I have become aware of disparities within the student population and the complexity of their intersections. Yet I have also learned to have faith in the future after seeing their deep commitment to igniting social change. They thirst for a better reality through education—a kind of transformation whereby experiential learning leads to a better society.

I often remind my students that social impact does not begin in distant and foreign territories but in the immediacy of our own backyards. At Dartmouth, that lesson evolved at La Casa, one of Dartmouth’s living and learning communities for students. In March 2020, the pandemic arrived to remind us of our fragility and impermanence. That’s when I began meeting virtually with three La Casa residents—Gabe Onate '21, Juan Quinonez '23, and Keren Valenzuela '21, plus a Thetford Academy student, Frank Loveland. We each logged on from our own island: California, Texas, Mississippi, Vermont, and New Hampshire. Digging into our own pockets, we launched the FUERZA Farmworkers’ Fund. (In Spanish, “fuerza” means “strength.”) In those first months, as fear and uncertainty mounted, we visited six dairy farms to listen to the concerns and struggles of our migrant neighbors as they faced the advent of the new virus.

In a cruel irony, the farm workers felt little changed by the arrival of the pandemic, since they were already living their lives, for the most part, in forced isolation. Their main distress was for their families in Mexico and

Central America. What weighed on them more directly was the sudden hypervisibility they faced: “They gave us dirty looks when we went to the store because we didn’t have masks,” they told us. The shortage of masks left migrant farm workers unusually exposed, subject to a level of scrutiny they had not experienced before.

Thanks to the support of Thetford Hill Church and generous donations from relatives of FUERZA’s co-founders, we distributed over 200 homemade masks across the farms. We also launched a series of forums to ensure our friends on the farms were seen and heard. We organized panels titled “Hands that Speak, Voices From the Farms of the Upper Valley," allowing a space where the farm workers spoke directly with the audience, sharing their needs and stories.

The same spirit infused our DCSI Borderlands trip to Texas in 2024,"From the Upper Valley to the Lower Valley: Immigration and the ‘New Ellis Island’ of the Texas-Mexico Border," where students stood face-to-face with harsh immigration and asylum-seeking policies at the border. Upon returning to Hanover, the journey continued as students engaged in exploring other kinds of borders in the Upper Valley: fences of silence, invisibility and marginalization.

The work ahead remains daunting. Structural violence still hides behind green mountains. Health care is still inadequate. Education is still a privilege rather than a right. Walls continue to rise. DCSI’s anniversary reveals that cultivating awareness blossoms into social impact. FUERZA is one example, born at the peak of a crisis, but it is not the only one. FUERZA is part of a larger network within the DCSI community through which students are making life better for people they might not otherwise meet. They persist in listening until the invisible becomes a name, and empathy grows into camaraderie.

The rhetoric of “diversity, equity, inclusion” and “sustainable justice” rings hollow if we close our eyes and surrender to the lull of our privileges and certainties in our classrooms. As a journalist, I learned the importance of observing, discovering, acknowledging the other and recognizing our overlapping

vulnerabilities. Only then can we approach and embrace each other along the same horizontal line, attentive, with non-judgmental empathy. Awareness is the seed that harvests the visibility of others. Ignoring the other is wrapping ourselves in a lukewarm dormancy that numbs us more than the sharpest winter.

As long as this collective pulse continues beating, the Upper Valley’s night sky will remain as starry as ever, and our work below will be worthy of its brilliance.

María Clara de Greiff Lara is a Colombian-Mexican journalist, writer, translator, and lecturer in Spanish and humanities. She co-founded FUERZA Farmworkers’ Fund and works with the First Generation Office.

Immersion Trips embed students on the forefront of change and contemporary social issues. The current trip takes students along the Texas-Mexico border where they engage with the nuances of immigration policy and asylum-seeking.

The Dartmouth Center for Social Impact's mission is to educate students to be transformative leaders for the common good.

Besides the programs featured earlier in this section, DCSI provides a host of other opportunities that connect our students with community-engaged learning which are outlined below. Through these programs, the students that participate in them, the partner organizations that host them, and the alumni that help fund them, we’re able to support and empower our local community and other communities across the world.

Growing Change – Connects Dartmouth students with local children in pre K to 2nd grade to explore food systems and nutrition.

Outdoor Leadership Experience – Dartmouth students teach leadership and outdoor skills to local youth through nature-based adventures.

SIBS – Pairs Dartmouth students one on one with youth ages 6 to 12 to serve as mentors and friends.

Foundations in Social Impact – a social impact leadership program designed exclusively for first-year students who work together to actively examine social impact themes and their place as changemakers in society.

ImpACT Winterim Leadership Intensive – enables students to make an impact on a social challenge in their home community or within the Upper Valley while learning with peers about systems mapping, a practical tool for changemakers.

Social Impact Non-Profit Consulting – a student-led, mission-driven consulting group which supports local social sector organizations to maximize their impact in the communities they serve.

Dartmouth Partners in Community Service –supports students interning at social sector organizations with a living stipend and alumni mentorship (more on the next page).

Cape Town Social Transformation Internship

Cohort – places students as interns at social sector organizations in Cape Town, South Africa that are driving systems level change.

’82 Upper Valley Community Impact Fellowship –created and supported by the class of ’82, this fellowship enables students to build a long-lasting impact in the Upper Valley through a strategic, innovative project they complete over the course of three to four terms.

Breaking the Mold – an annual conference which brings alumni who have leveraged their careers for the common good back to campus to speak to students.

Schweitzer Fellows Program – funds graduate health professional and law students enrolled at institutions in New Hampshire and Vermont (including the Geisel School of Medicine) to address unmet health needs throughout the region.

Olga Gruss Lewin Fellowship – supports recent Dartmouth graduates who are pursuing significant acts of citizenship and service to others after graduation.

Bridges to Impact – an alumni-led professional development community for recent graduates working, volunteering, or studying in social-impact related fields with current chapters in Boston, Washington D.C., and New York City.

Dartmouth Partners in Community Service (DPCS) was born from a simple idea proposed at the Class of 1959’s 35th reunion: to create a structured way for alumni to support students who want to “give back” during an off term. The class rallied to raise funds, and with College approval, brought this idea to life in the form of the DPCS program. It provides a living stipend, alumni mentorship, and professional development support to students interning at social sector organizations. DPCS was housed within the Tucker Foundation and the Center for Social Impact continued to steward it after it branched out from the Foundation in 2015.

Since its founding in 1995, close to 20 alumni classes have joined the ‘59s to sponsor the program, along with hundreds of alumni who have volunteered their time as mentors to students. Over 1,000 students have participated in DPCS in the three decades since its inception, lending their time and talent to underserved communities across the country.

“This experience reinforced the idea that true social impact is a collaborative effort rooted in trust, empathy, and a deep commitment to fostering the resilience and capabilities of the communities we serve."

- Max Winzelberg '27

We are incredibly proud to be celebrating 30 years of DPCS alongside DCSI’s 10th anniversary. This program serves as a powerful example of how the alumni community can create an enduring legacy which reflects Dartmouth’s shared commitment to service and impact.

DPCS was formally recognized in 2019 with the Granger Award for Lifetime Achievement in Public Service, presented to the Class of 1959 (pictured).

A special thanks to the classes of '44, '58, '59, '63, '67, '79, '83, '85, '86, '87, '88, '89, '90, '92, and '95 for their continued support of this transformative program.

Every year, shortly after commencement, Dartmouth runs a cap and gown survey to glean where its most recent graduates have landed professionally. In its most recent publication, centered on the class of 2023, a full 49% of respondents indicated they were working in either finance or management consulting following graduation.