Dwindling Urban Wetlands

Examination of the Impact of Rapid Urban Development on Bengaluru’s Lakes by Darshan Thimmasandra Kenchappa

[ Student id : 22583388 ]

Dissertation Submitted to Manchester School of Architecture

In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the MA Architecture & Urbanism Degree Page left intentionally blank

Copyright © 2023

All Rights Reserved

Manchester School of Architecture

Manchester Metropolitan University [Student ID : 22583388]

University of Manchester [Student ID : 11454292]

Supervisor:

Eamonn Canniffe

Author:

Darshan Thimmasandra Kenchappa

No part of this publication may be reproduced. Stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronics, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright owner.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my supervisor Prof. Eamonn Canniffe for his invaluable guidance, unwavering support, and insightful feedback throughout the research process. His expertise and encouragement have been instrumental in shaping the direction of this study. I extend my appreciation to Dr. Debapriya Chakrabarti and Dr Matthew Steele for their thoughtful critique and valuable suggestions that have enriched the quality of this work.

I am grateful to my family and friends for their understanding, encouragement, and unwavering belief in my abilities. Their support has been a constant source of strength throughout this academic journey.

Abstract

This dissertation explores the interconnections between the historic significance of the lakes in Bengaluru, urban wetland depletion, rapid urbanization, biodiversity loss, and lake reclamation in urban areas. It is focused on the disappearance of the vital water/wetland resources at the heart of modern cities.

By conducting an extensive literature review, this research establishes a robust theoretical framework, examining factors, drivers, and outcomes associated with the degradation of urban wetlands. The methodology employs a multidisciplinary approach, integrating spatial pattern analysis, biodiversity assessments, hydrological modelling, and stakeholder interviews, drawing insights from a thorough examination of the literature survey. The contextualization section addresses research gaps, focusing on understanding wetland loss in Bengaluru and offering valuable insights for urban infrastructure planners. Subsequently, two sites in Bengaluru will be analysed as case studies, utilizing derived methods to facilitate critical analysis and provide recommendations for future research. This concise research paper aims not only to contribute to existing literature but also to offer valuable insights for policymakers, planners, and stakeholders to enhance urban resilience and sustainability.

01 00. List of Figures | List of Tables 01 Contents 05 06 07 02 03 04 Introduction 03 - 12 1.1. Background and Context 1.1.1. Wetlands in Bengaluru 1.2. Rationale for the Study 1.3. Objectives 1.4. Scope and Limitations Case Research: Lakes of Bengaluru 34-47 5.1. Bellandur Lake 5.1.1 Development Through the years: Spatial and Land use Changes 5.1.2 Present Biodiversity condition of Bellandur Lake 5.1.3 Responses of Government agencies 5.1.4 Comments, Suggestions in newspaper and Stakeholder involvement 5.1.5 Discussion 5.2. Sampangi Lake 5.2.1 Sampangi Lake, in the Pages of History 5.2.2 Sampangi Lake: Evidence from Archival Document 5.2.3 Discussion Conclusion 48-49 References 50-51 Literature Review 14-21 2.1. The Historical Significance of Lakes and its Relevance to Contemporary Urban Requirements 2.2. Urban Wetland Depletion: Causes and Consequences 2.3. Urban Wetland Depletion: Rapid Urbanization 2.4. Increased Flooding Risks in Urban Areas Methodology and Research Approach 24-26 3.1. Analysis of Alterations in the Lake body and Shoreline 3.2. Lake Condition Analysis 3.3. Hydrological Modeling 3.4. Stakeholder Interviews and Government Agencies 3.5. Data Collection & Analysis Contextualization 28-32 4.1. Bengaluru and its wetland management 4.1.1 Current Scenario Of lakes 4.1.2 Status of Lakes in Bengaluru 4.1.3 Status of water quality of Bengaluru lakes 4.1.4 Lake Management and proposed actions 4.2. Comparative Analysis with Existing Research 4.3. Bridging the Gap Between Urban design infrastructure and Wetland Ecology

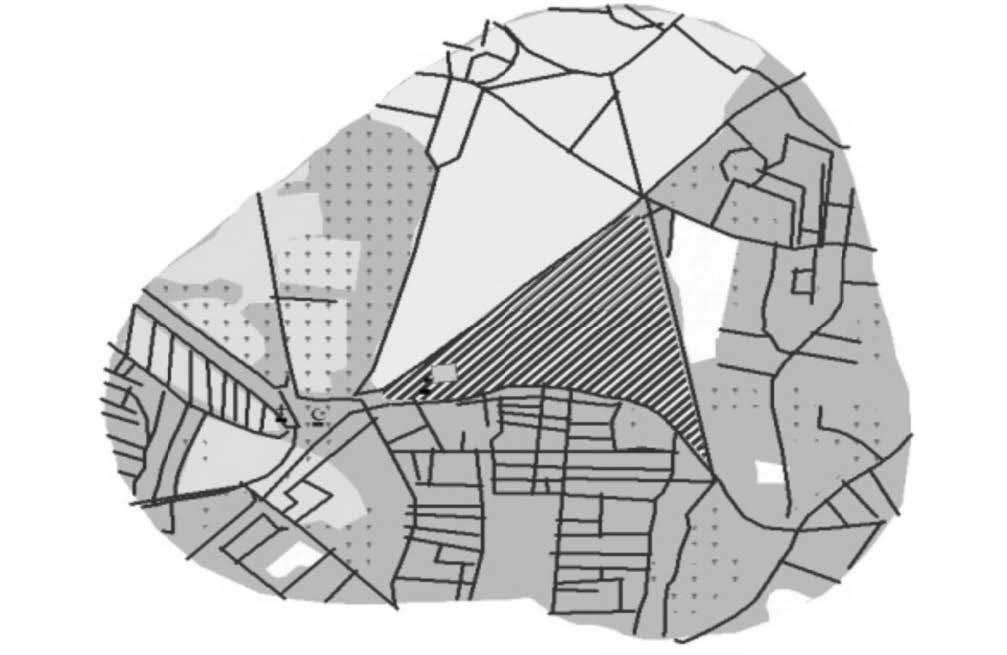

Figure 1 : Painting of Ulsoor Lake by Akhil Mekkatt [source: Saatchi Art]

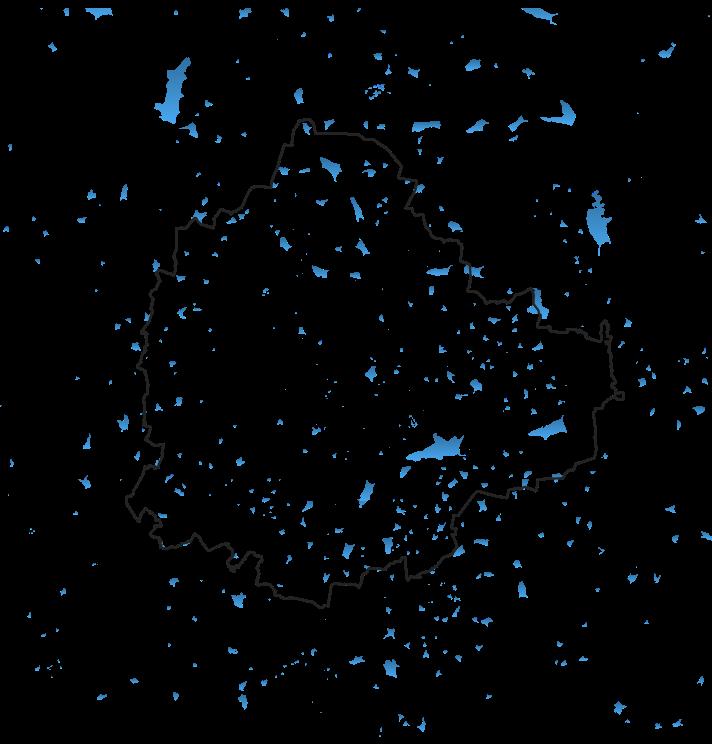

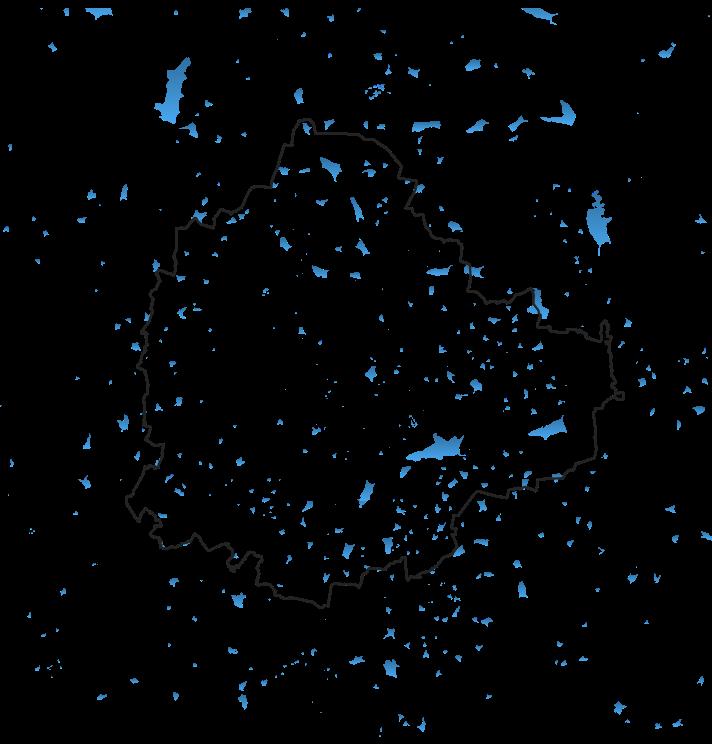

Figure 2 : Map showing the current lake bodies of Bengaluru [ Source: Author]

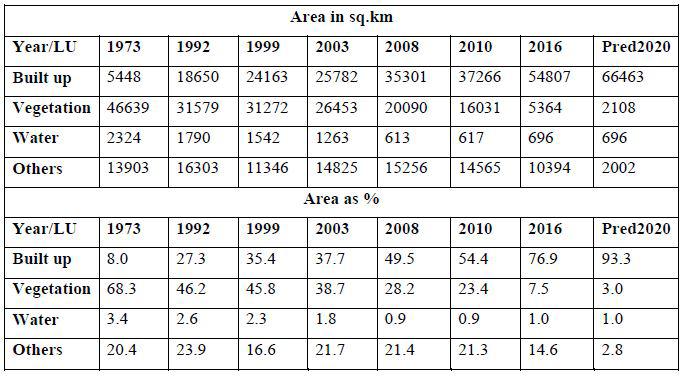

Figure 3 : Map showing the land use dynamics of Bengaluru [source: author]

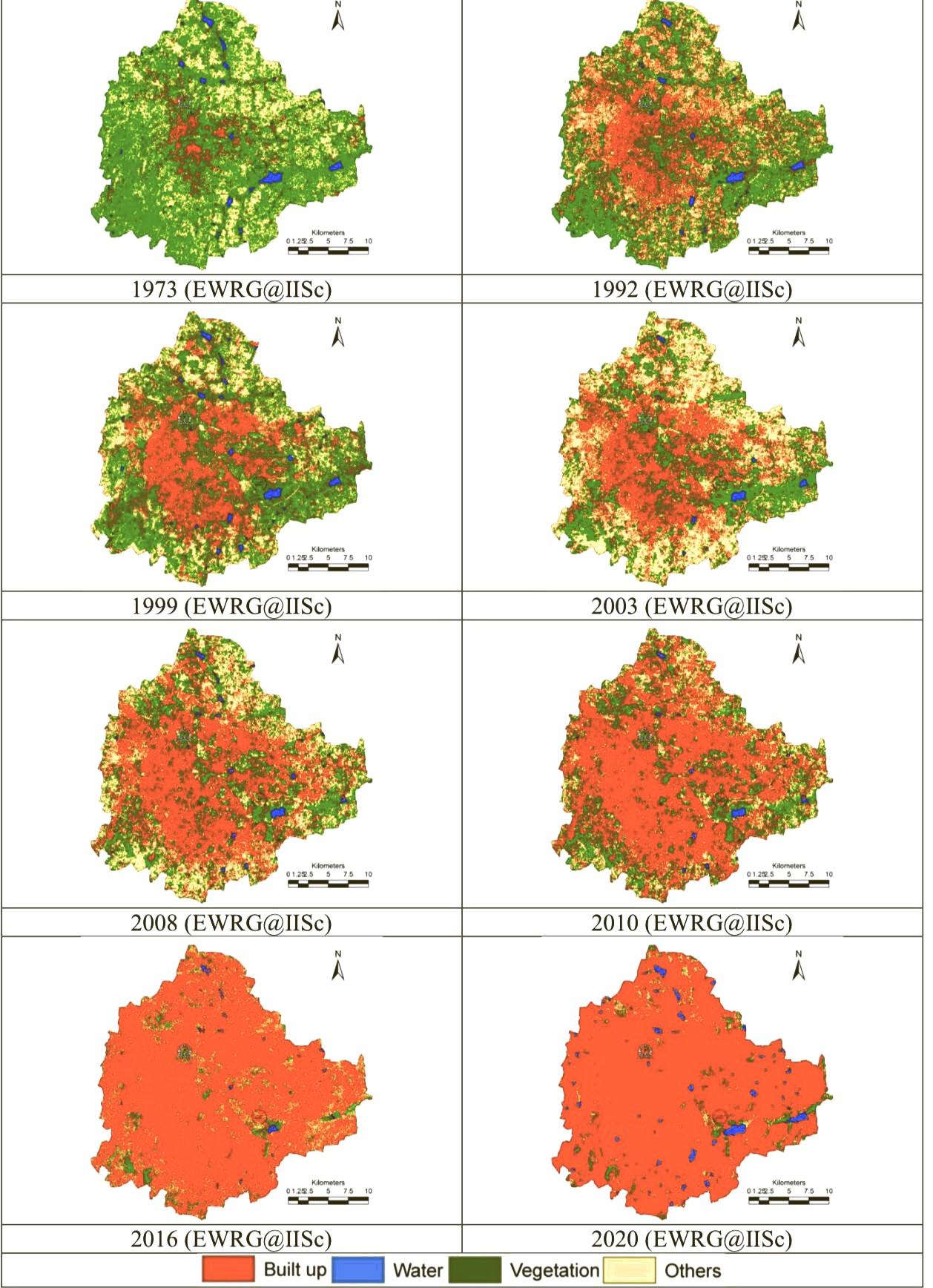

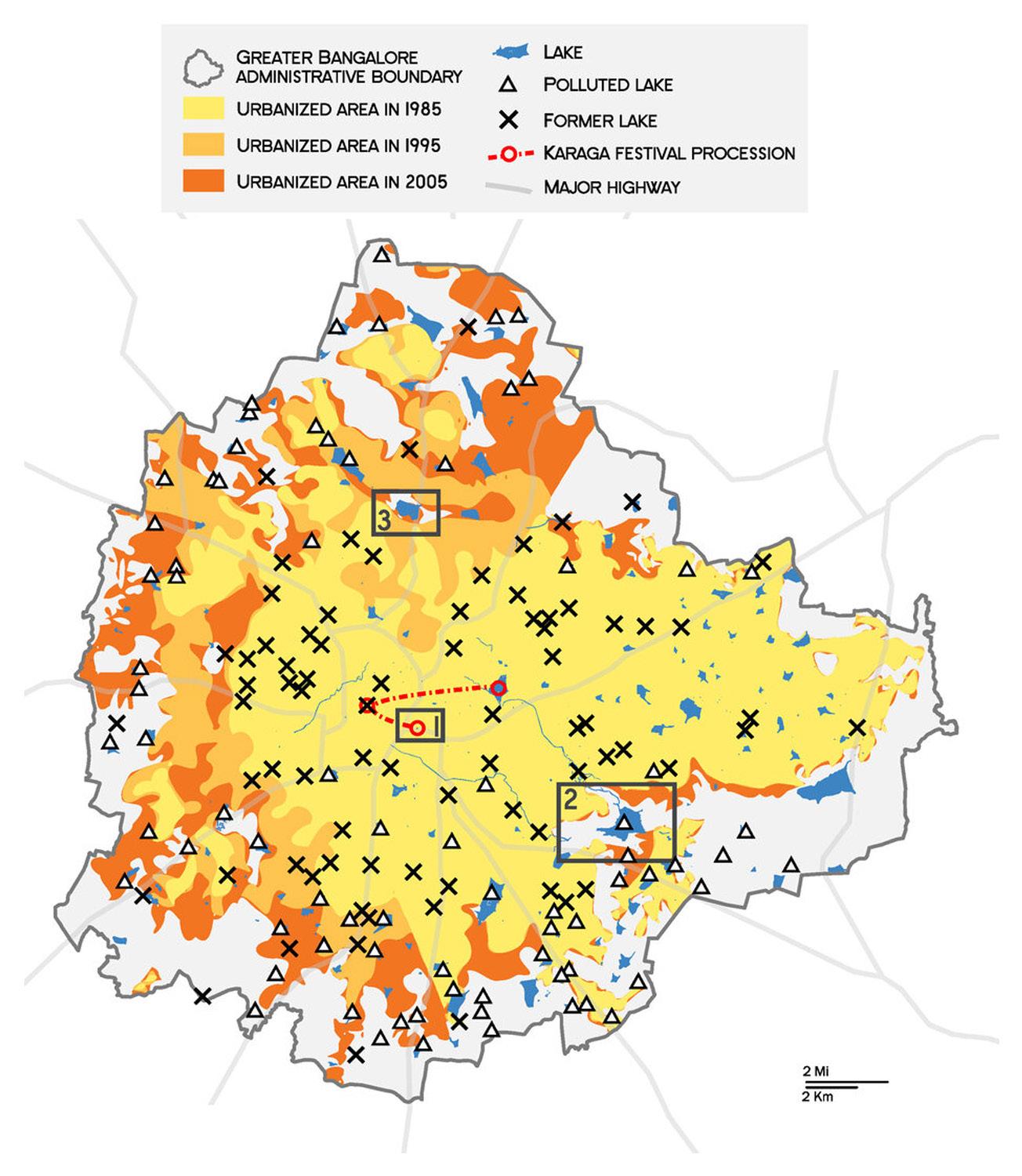

Figure 4 : Map showing the lake bodies with the context of urbanization [ source: Daniel Brownstein]

Figure 5 : illustrations of Urbanization in Bengaluru by Labonie Roy [source: Mongabay]

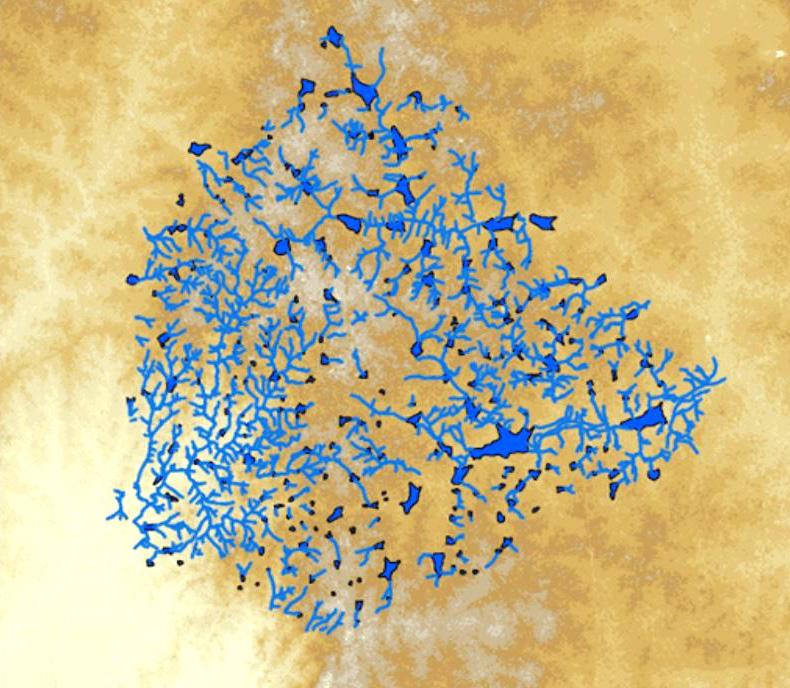

Figure 6 : Tank Map of Bengaluru tanks [source: Gubbi labs]

Figure 7: Ilustrations of Kere (Lake) in Bengaluru by Labonie Roy [source: Mongabay]

Figure 8: View of Ulsoor lake [source: Wikipedia]

Figure 9: View of non-maintained Bellandur lake in Bengaluru [source: Wikipedia]

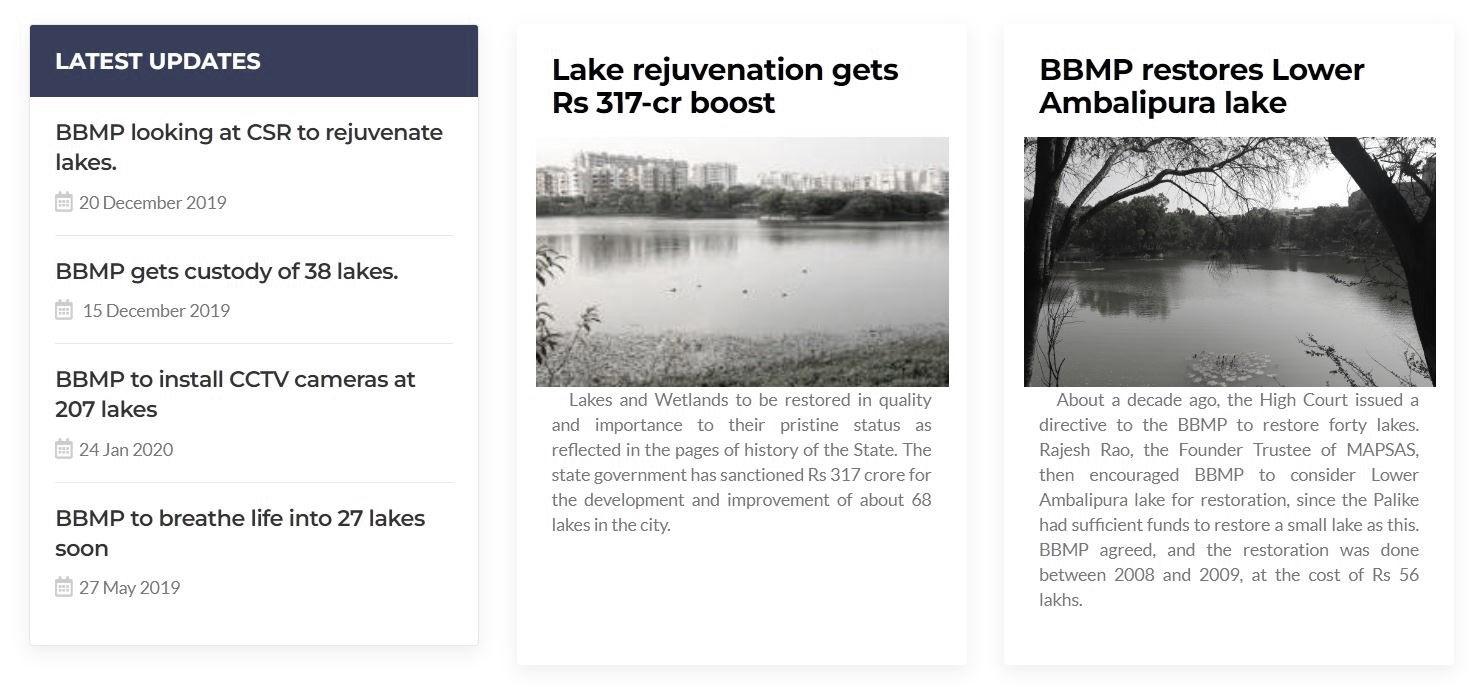

Figure 10: Snippet of future projects under lake development authority [source:BBMP Lakes department]

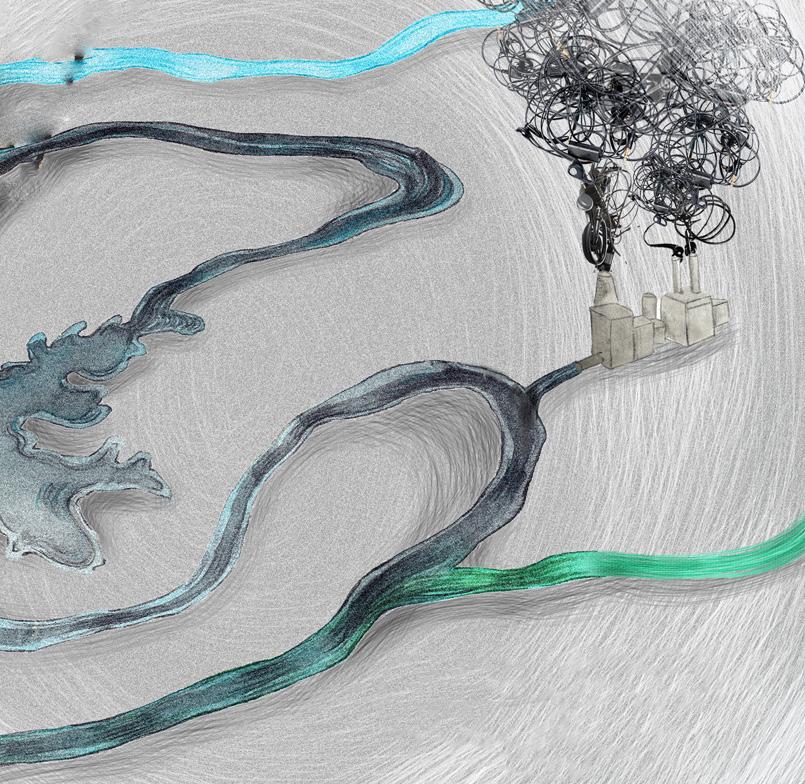

Figure 11: illustrations of lake pollution in Bengaluru by Labonie Roy [source: Mongabay]

Figure 12: Image of Bellandur lake[source:Wikipedia]

Figure 13: Map showing the variations in lake boundary of Bellandur lake [source: author]

Figure 14: Image showing the flames coming out of burning chemical froth of Bellandur lake [source: The Guarding Newspaper]

Figure 15: Image showing the view of remains of Sampangi river [source: author]

Figure 16: Set of images showing the transformation of Sampangi lake [source: author]

Table 1: Table showing lakes of old Bengaluru and their present condition

01

| List

List of Figures

of tables

1.1 Background & Context

Wetlands play a crucial role in natural environments, providing a wide array of benefits to ecosystems. Wetland is defined as ‘areas of marsh, fen, peat land or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tides does not exceed six meters (Secretariat, 2016)

Wetlands stand out as some of the most diverse and productive ecosystems on our planet. These habitats serve as protective buffers against natural disasters, contribute to our sustenance and water resources, and enhance our ability to withstand the impacts of climate change. It is important to note, however, that depending on how they are managed, wetlands can function both as repositories and sources of carbon. Given their dual significance and susceptibility to climate shifts, it is imperative for those overseeing wetlands to grasp how climate-related risks impact these areas and to formulate appropriate strategies for adaptation and mitigation(ICEM, 2023)

Looking at the same in cities, wetlands enhance the quality of urban life by enhancing water purity, sequestering carbon, offering homes for diverse wildlife, mitigating the impacts of urban heat islands, and providing recreational spaces(Brinkmann et al., 2020) Yet, preserving wetlands within urban settings encounters numerous obstacles, including diminished hydrological functions, altered water patterns from obstructions, pollution from wastewater, habitat depletion due to land-use alterations, and a decline in biodiversity caused by the introduction of non-native species(Brinkmann et al., 2020)

Moreover, I have endeavored to comprehend the various types of wetlands in India, specifically concentrating on the southern region, by narrowing down my focus.

Introduction 03

01 Introduction

Figure 1 :

Painting of Ulsoor Lake by Akhil Mekkatt [source: Saatchi Art]

India boasts a diverse array of wetlands, thanks to its varied precipitation patterns, physiography, geomorphology, and climate. Each of these wetlands is a unique and invaluable ecosystem. Those of conservation significance can be classified as Internationally Important Wetlands(MoEFC, n.d.). The benefits of wetlands are recognized globally, yet they remain a subject of apathy in Indian cities.

Although many government and state agencies have wetlands under the domain of responsibility, unclear and overlapping jurisdictions between them have caused significant losses of urban wetlands(Verma, 2023). Shifting focus to the southern part of India, specifically the state of Karnataka, the capital city, Bengaluru, has undergone rapid urbanization in recent years, with the reservoirs or tanks playing a crucial role in the city’s functioning.

1.1.1 Wetlands In Bengaluru

Bengaluru serves as the primary hub for administration, culture, commerce, industry, and knowledge in the state of Karnataka, India. Originating as a small village in the twelfth century, it has expanded over the centuries to become the fifth largest city in India today. According to popular belief, its name “Bengaluru” in the local language Kannada, from which “Bengaluru” is derived, is linked to an agricultural service, referencing the term “benda kaalu ooru” - meaning ‘town of boiled beans’. The establishment of modern Bengaluru is credited to Kempe Gowda, a member of the Yelahanka lineage of leaders, in 1537. Kempe Gowda is also acknowledged for erecting four towers in the cardinal directions from the Petta, the central part of the city, to mark out the projected expansion boundaries (Kamath, 1990).

Particularly about Bengaluru’s wetlands, we can see that lakes or reservoirs built during the 1750s have historically played a vital role in the ecological, social, and economic fabric of Bengaluru. They served as sources of freshwater, supported diverse aquatic ecosystems, provided recreational spaces, and contributed to the overall aesthetic beauty of the city. However, the exponential growth in population, coupled with urban sprawl and industrialization, has severely impacted these natural resources(Brinkmann et al., 2020).

Introduction Introduction 04 05

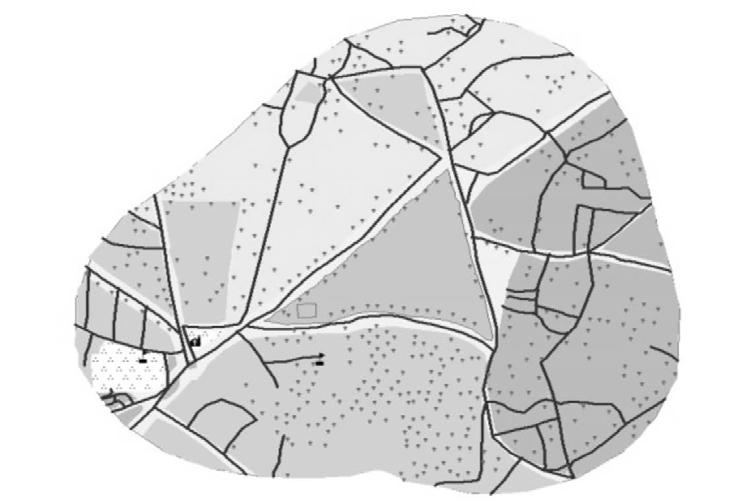

Figure 2 : Map Showing the Current Lake Bodies of Bengaluru [ source: author]. Black represents the boundary of bengaluru and blue represents the lakes.

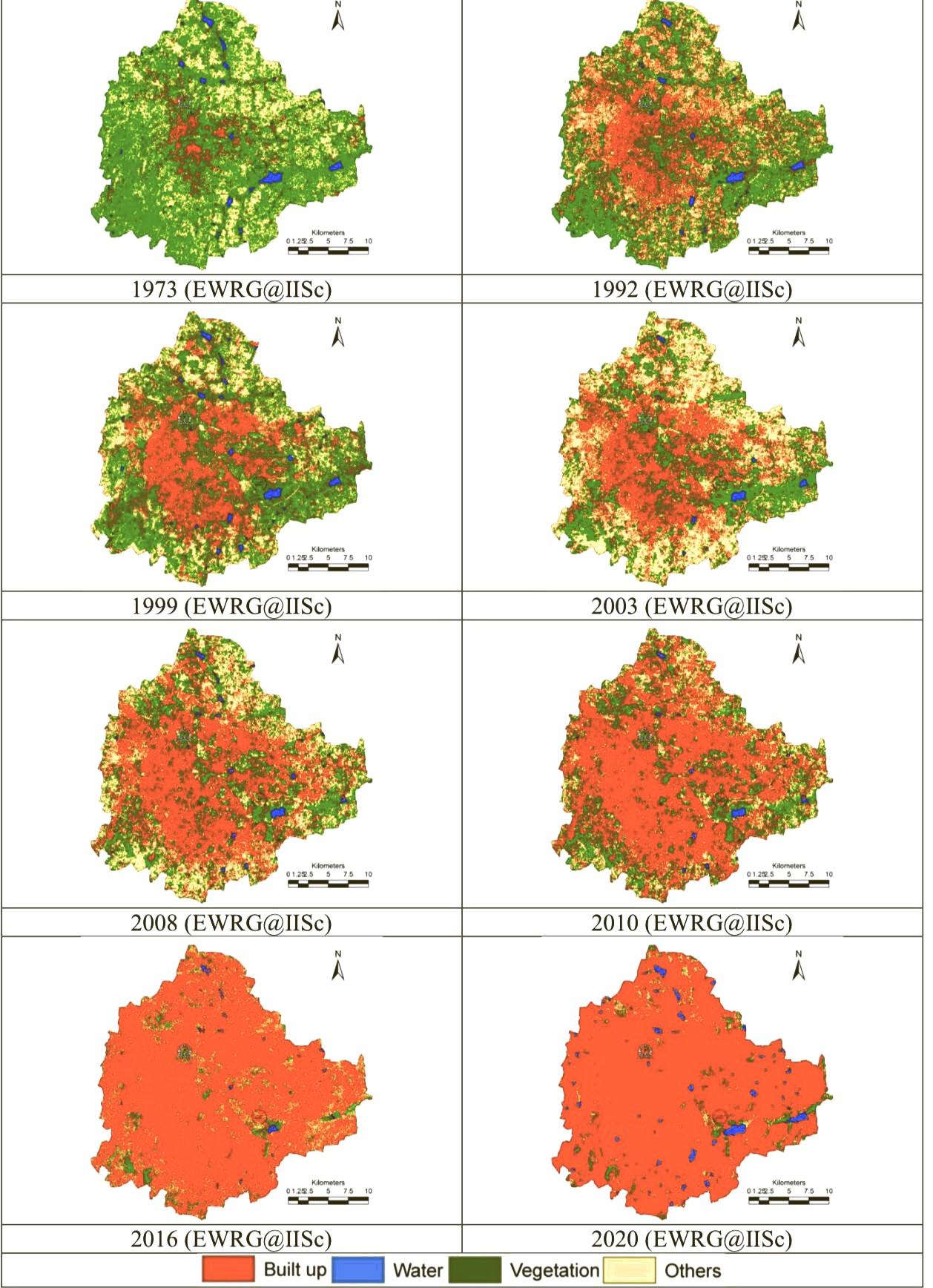

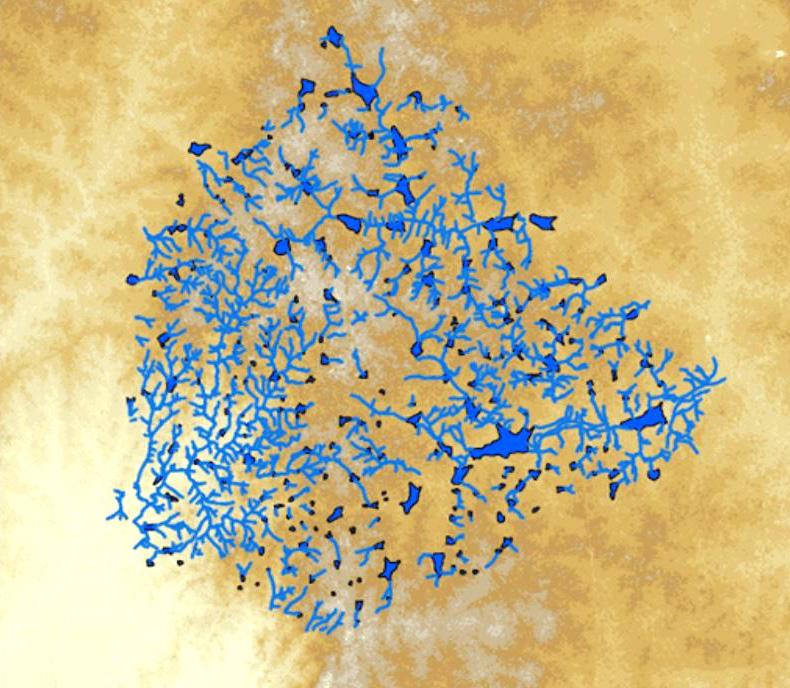

The urbanization of Bengaluru, started in the 1950s and led to the drastic reduction of the number of lakes in the hilltop city, once known as “the necklace of the lakes”(Brownstein, 2021). Seasonal rains during the monsoons were originally captured in the man-made lakes, ponds, and tanks of which some were built during the Kempe Gowda’s time(1500s) (founder of Bengaluru). The water thus captured was used for domestic drinking, agriculture including irrigation and livestock washing and religious practices. Today the disappearance of the water evidently has a relative absence of the gardens and parks. Moreover, the remaining water bodies are subjected to pollution from the untreated sewage water(Brownstein, 2021).

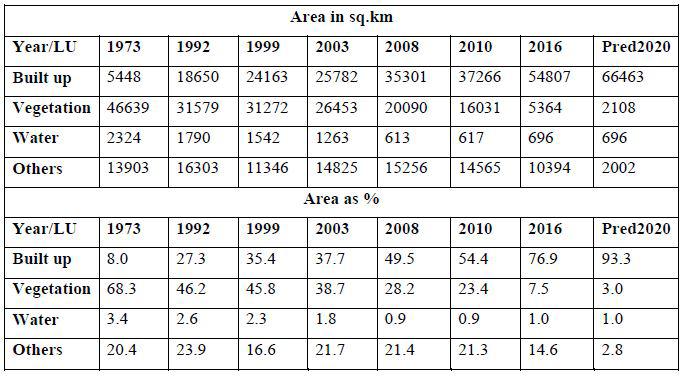

Over a period, the functions served by the lakes and tanks have gradually changed due the urbanization and the consequent changes. Due to the creation of residential and commercial layouts by bodies such as the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA), Karnataka Industrial Area Development Board (KIADB), Bangalore Metropolitan Region Development Authority (BMRDA) as well as illegal encroachments by real estate organizations, the number of lakes has diminished rapidly. The following table and maps shows the land use changes in Bengaluru city between 1973 and 2020. Land use analysis in bengaluru city shows about 1005% increase in urban area between 1973 and 2016 i. e. from 8% to 77% . The water bodies have reduced from 3.4% to almost 1% between 1973 to 2020. Unplanned rapid urbanization during post 2000’s has led to drastic and unrealistic land use changes.

Introduction Introduction 06 07

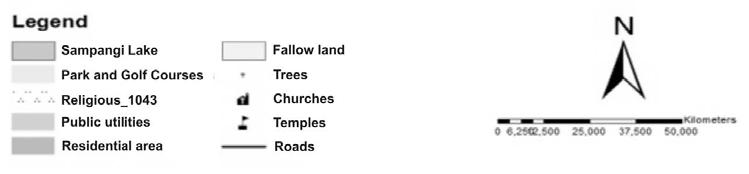

Figure 3a : Map showing the land use dynamics of Bengaluru between 1973 and 2020 [source: author].

Figure 3 : Map showing the land use dynamics of Bengaluru between 1973 and 2020 [source: author].

Official figures put the number of lakes at 117 as of now out of which only 81 are recognizable through government records. However, recent satellite imagery (2003) gives a different picture altogether. As per satellite imagery, only 33 lakes are visible out of which only about 18 exist in some shape while another 15-20 show some signs of existence. Many lakes have been converted into bus stands, stadiums etc. Some notable examples of these are- The Kempe Gowda bus stand, which was once Dharmabudhi Lake, Kanteerava stadium, which was Sampangi Lake, PGA golf course, which was Challagatha Lake(DSouza, 2006).

A list of such lakes has been listed on the website of the Department of Ecology & Environment, Govt. of Karnataka.

Name of Lake Status at Present

Shoolay lake

Football stadium

Akkithimmanhalli lake Hockey stadium

Sampangi lake

Dharmabudhi lake

Sports stadium

Bus stand

Challaghatta lake Golf Course

Koramangala lake

Nagashettihalli lake

Residential layout

Space department

Kadugondanahalli lake Ambedkar Medical College

Domlur lake

Millers’ lake

Subhashnagar lake

Kurubarahalli lake

Kodihalli lake

Sinivaigalu lake

Marenahalli lake

Shivanahalli lake

BDA layout

Residential layout

Residential layout

Residential layout

Residential layout

Residential layout

Residential layout

Playground, Bus stand

The below figure shows the urbanization of Bengaluru from 1900’s to present time. It depicts the existing condition of the lake bodies and their extent compared to the extent of increasing Bengaluru city.

Introduction Introduction 08 09

Figure 4 : Map showing the lake bodies of Bengaluru with the context of urbanization [ source: Daniel Brownstein]

Table 1: Table showing lakes of old Bengaluru and their present condition

Many cities consider the conservation and restoration of urban wetlands as a strategy in urban planning that can make cities more resistant to climate change. However, while wetlands play an essential role in cities and offer various services, these services are drastically under pressure due to rapid urban expansion(Alikhani et al., 2021).

Urbanization and city development present numerous challenges to wetlands. The loss of wetlands in urban areas is influenced by various factors, and there is ongoing debate about the potential positive aspects of certain alterations to existing wetlands, depending on their intended use. Major challenges faced by wetlands include direct habitat loss through activities such as land reclamation and dredging, alterations to the water regime caused by barriers, contamination from wastewater, garbage, and pesticides, and biodiversity decline resulting from the introduction of nonnative species(Alikhani et al., 2021)

Therefore, wetland preservation has been seriously threatened by the surrounding urban development and expansion processes. It is necessary to preserve wetlands in cities to help reduce climate change impacts. Therefore, the need to study wetlands and their effects on urban areas and their inhabitants is required (Alikhani, 2021).

The purpose of this dissertation is to delve into the various factors that are leading to the permanent loss of the Urban Wetlands (once reservoirs) which play a critical role in the city’s ecosystem. By examining the several elements contributing to the degradation of these water bodies, this research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex challenges faced by the city and explore potential strategies for lake rejuvenation and sustainable urban development.

1.2 Rationale for the Study

The depletion of wetlands in the central area of Bengaluru in recent years has resulted in significant consequences, prompting the need for new methods and research to establish a robust foundation for effective conservation efforts.

The study of urban wetland conservation in Bengaluru is crucial for several reasons, offering insights into the challenges and opportunities associated with integrating natural features, such as lakes, into the urban infrastructure framework. This is particularly relevant in the global context of rapidly expanding cities, where striking a balance between urban development and ecological preservation is a critical concern. While the wetland preservation community has made notable strides in analyzing various influencing factors, there is a requirement for enhanced understanding and methodologies to formulate strategies for urban infrastructure development that prioritizes the preservation of these essential lakes.

Moreover, understanding the dynamics of wetland conservation within urban design allows for the development of design interventions and strategies that can enhance the resilience and sustainability of urban areas. This includes the creation of blue-green networks, green corridors, and multi functional spaces that leverage wetlands for ecological, recreational, and aesthetic purposes.

1.3 Objectives

The primary objectives of this dissertation are:

a. To Investigate the historical and current alterations in lake patterns and their impact on the city’s biodiversity. To understand the different causes and consequences of wetland depletion.

b. Examine the various reasons behind wetland depletion and its repercussions.

c. To Develop a research approach and strategies for conserving and improving wetlands in Bengaluru, ensuring their effective integration into the urban environment.

d. Evaluate the authority, control, and stakeholders’ ownership of the lakes, examining reasons for the lack of regulation or attention to propose solutions for the diminishing shorelines of the lakes.

Introduction Introduction 10 11

1.4 Scope and Limitations

This study primarily focuses on the lakes within the municipal limits of Bengaluru, examining their relationship with urban fabric. While there may be other wetlands of ecological significance in the broader region, this research centers on those directly impacted by urbanization. Additionally, it acknowledges that wetland conservation is a multifaceted issue influenced by various factors, and this study will aim to provide a focused urban researcher perspective.

Through this research, we hope to shed light on the pressing issues related to the diminishing lakes of Bengaluru and generate valuable insights that can inform policymakers, urban planners, environmentalists, and local communities alike. By understanding the complexity of the problem and identifying potential solutions, we strive to contribute to the ongoing discourse on sustainable urban development and the preservation of valuable natural resources in rapidly growing cities around the world.

Introduction 12

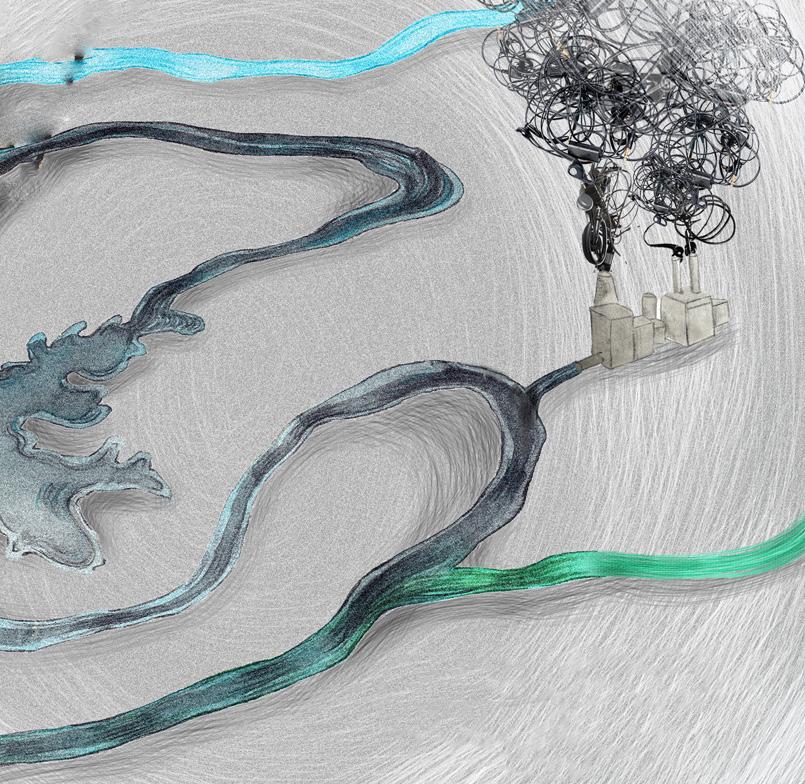

Figure 5 : Illustrations of Urbanization in Bengaluru by Labonie Roy [source: Mongabay]

This chapter delves into a comprehensive review of urban wetland literature, aiming to evaluate the factors contributing to its depletion and the detrimental impact of rapid urbanization on wetland loss. The examination extends to literature concerning temporal and spatial analysis of lakes, emphasizing their repercussions on the biodiversity of the adjacent areas. This scrutiny provides a critical understanding and elucidates key insights that prove instrumental in the subsequent phases of the research.

A critical review of literature has been conducted, focusing on specific categories related to lake degradation and rapid urbanization in Bengaluru, along with their implications for urban ecology. These categories include Historical Significance, Wetland Depletion, Rapid Urbanization, Biodiversity Loss, and heightened flood risks.

2.1. The Historical Significance of Lakes and its Relevance to Contemporary Urban Requirements

This literature segment delves into the historical evolution of lakes, emphasizing the importance of considering their cultural, social, and economic dimensions with the objective of developing a sustainable approach for preserving lakes within the context of increasing urbanization.

One of the articles, authored by delves into the historical uses of Bengaluru lakes and examines the ongoing changes in their shorelines. The article presents a historical perspective on Bangalore, emphasizing its continuous urban settlement from the mid-sixteenth century. Despite the absence of major perennial water sources, the city historically depended on a network of rainwater-fed tanks or lakes. These water bodies played a vital role in supplying drinking water, supporting agriculture, pastoralism, and contributing to the local economy. Positioned strategically in the naturally varied landscape, the interconnected lakes facilitated the flow of excess monsoon water from higher to lower elevation lakes(Unnikrishnan et al., 2018).

This article holds the opinion that Local communities played a pivotal role in constructing, maintaining, and managing these lakes. Inscriptions near lakes documented grants of land, orchards, and wells, showcasing the long-term visions of various contributors. These inscriptions also reflected the diverse social fabric, with rules and norms regulating access to ecological resources. The relationship between lake-dependent communities and the water bodies were characterized by social-ecological interdependencies, despite societal divisions. However, urbanization and population growth led to water scarcity challenges in Bangalore. During the colonial era, the city transitioned to piped water from external sources, marking a decline in dependence on local lakes. Rapid urbanization further contributed to pollution, and many lakes disappeared between 1885 and 2014(Unnikrishnan et al., 2018). The perception of lakes shifted from utilitarian resources to potential risks, leading to drainage and conversion for development purposes.

Literature Review Literature Review 14 15 02 Literature Review

Figure 6 : Tank Map of Bengaluru tanks [source: Gubbi labs]

The conclusion emphasizes the current water scarcity challenges that Bengaluru is facing and suggests a historical perspective for understanding past cultural relationships with lakes. It advocates for inclusive lake restoration that goes beyond recreational use and groundwater recharge, focusing on fostering a deeper social-ecological connection for long-term sustainability.

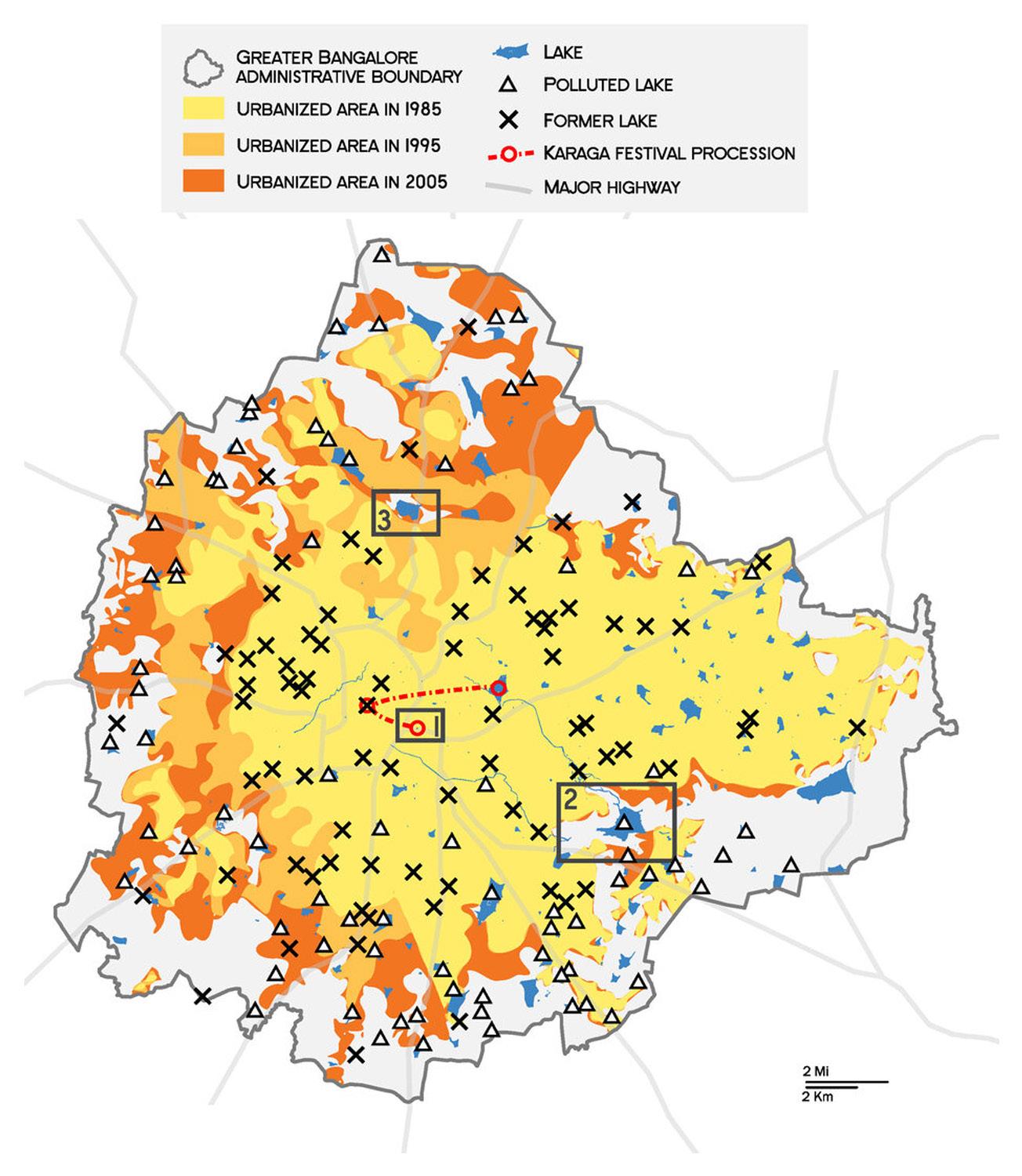

Numerous other works delve into the historical evolution of urban wetlands, but my emphasis has predominantly been on literature pertaining to the broader Bengaluru region to establish context and significance. A notable example is a publication by Ramachandra T. V., whose research posits that Bengaluru’s lakes played a crucial role in shaping the city’s history and culture. They were integral to the region’s agricultural practices, providing irrigation for crops and sustaining livelihoods. Additionally, these water bodies served as gathering places for communities and played a crucial role in religious ceremonies and cultural events. The interconnected network of lakes formed a resilient ecosystem, supporting diverse flora and fauna, and contributing to the overall well-being of the region(Ramachandra et al., 2014).

This paper also looks at the present scenario of a few lakes that over the years. Bengaluru’s lakes have also been celebrated for their aesthetic and recreational value. Lakes such as Ulsoor and Sankey Tank have been popular destinations for boating and picnicking, offering residents and visitors a respite from the urban hustle and bustle(Ramachandra et al., 2014). This historical significance underscores the importance of preserving and restoring these water bodies in the face of urbanization.

2.2 Urban Wetland Depletion: Causes and Consequences

This segment of the literature review centers on the main reasons and outcomes associated with the reduction of wetlands. Within the extensive body of literature on this subject, various factors pertinent to the specific study area would have been explored individually. To gain contextual insights, I am specifically investigating the causes of wetland depletion in Asia, with a particular emphasis on India, considering both climatic and socio-economic factors.

In one of the reports published by Prasad S. N, Ramachandra T.V and group have extensively looked at the core causes to the wetland depletion. The report suggests that wetlands, globally and in India, are facing increasing threats due to anthropogenic pressures such as population growth, land use changes, and development projects. The depletion of wetland resources in India is attributed to conversion threats from industrial, agricultural, and urban developments, resulting in hydrological disruptions and pollution. Unsustainable grazing and fishing activities further contribute to wetland degradation. Given that a significant portion of India’s population relies on wetlands for food production and potable water, their health is crucial. However, the loss of wetlands in India is exacerbated by factors like agricultural conversion, direct deforestation in wetlands, hydrologic alterations, inundation by dammed reservoirs, and chronic issues like watershed alterations, water quality degradation, ground water depletion, and the introduction of non-native species(Prasad et al., 2002). The study emphasizes the importance of addressing these issues to ensure the conservation of India’s diverse wetland ecosystems.

The “Wetlands” report by W.J. Mitsch and J.G. Gosselink, published in 2015, likely provides an in-depth exploration of wetland ecosystems. It covers topics such as the ecological importance of wetlands, their biodiversity, functions within ecosystems, and the impact of human activities on these vital areas. This report also discusses conservation and restoration efforts, along with the challenges faced by wetlands globally. The report suggests that the depletion of urban wetlands, including lakes, is a global phenomenon driven by a combination of natural and anthropogenic factors. Land use changes, including conversion for residential and commercial purposes, have been identified as primary drivers of wetland degradation (Mitsch and Gosselink, 2015). Encroachment on wetlands for infrastructure development and urban expansion has led to the direct loss of these critical ecosystems (Mitsch and Gosselink, 2015).

Additionally, By examining other articles we can conclude that pollution from urban runoff, industrial discharge, and domestic waste has significantly impacted the water quality of urban wetlands (Ramachandra et al., 2020).

Literature Review Literature Review 16 17

The resulting deterioration of water quality not only affects the biodiversity of these ecosystems but also poses risks to public health. The consequences of urban wetland depletion are far-reaching. Beyond the loss of biodiversity, the reduction of wetland areas has been linked to increased flooding events in urban areas (Kundzewicz et al., 2014). Wetlands serve as natural buffers against floods by absorbing excess water during heavy rainfall events. The loss of this regulating function can exacerbate the impacts of flooding on urban communities.

2.3 Urban Wetland Depletion: Rapid Urbanization

This part of review of existing literature delves into more detailed elements, such as the impact of urbanization on wetland reduction. It examines the available literature to comprehend the influence of evolving urban structures on the biodiversity of urban wetlands. It is crucial to grasp the dynamic spatial changes and their impact on the boundaries of urban wetlands. Numerous surveys conducted present varying perspectives on whether repurposing or reusing wetlands for human purposes is advisable.

To begin with, I have looked at multiple reports and articles which delves into research of the impact of urbanization on the wetlands. Bengaluru, emblematic of India’s urbanization trends, has experienced rapid growth in recent decades. This urban expansion has been characterized by a surge in population, accompanied by extensive land use changes. The resulting pressure on natural resources, including wetlands, has been substantial. The conversion of wetlands into built environments, including residential and commercial spaces, has been a notable consequence of this rapid urbanization(Rajashekara and Venkatesha, 2017).

Further, when discussing the concept of lakes that are disappearing or shrinking, there have been several articles that provide explanations for this phenomenon. One of these articles focuses on investigating the effects of urbanization and urban sprawl in Bengaluru, India, using temporal remote sensing data and landscape metrics. The aim of the research was to measure and understand the dynamics of urbanization by examining changes in land use and their spatial patterns, trends, rates, and impacts over a period of forty years. The study uncovered noteworthy growth in built-up areas,

accompanied by a decline in vegetation and water bodies in Bengaluru. The analysis of temporal data highlighted substantial increases in urban builtup areas during different time periods. Additionally, the research examined urbanization patterns at local levels by dividing the study area into zones and concentric circles, revealing a radial pattern of urbanization extending from the core of the city to its periphery. To gain a deeper understanding of urban sprawl, various landscape metrics were employed. Principal component analysis was utilized to prioritize the metrics for detailed analysis. The findings demonstrated a shift from smaller patches to a larger aggregated patch in recent years, indicating a trend towards increased compactness and urbanization. This transformation was attributed to the rapid urbanization and industrialization observed in Bengaluru(Ramachandra, Aithal, 2016).

The research emphasized the significance of landscape metrics and monitoring techniques as indispensable tools for effectively managing and conserving natural resources in the face of urban growth. It underscored the necessity of proper urban planning and sustainable management strategies to address the challenges associated with unplanned urbanization, while ensuring the provision of infrastructure and basic amenities in Bengaluru(Ramachandra, Aithal, 2016).

He further gives a figure of the urbanization impact. The research finds that Urbanization (1005% concretization or paved surface increase) has telling influences on the natural resources such as decline in green spaces (88% decline in vegetation) including wetlands (79% decline) and / or depleting groundwater table. Table 1 and Figure 1 gives an insight to the temporal land cover changes during 1973 to 2013. The built-up area has increased from 7.97% in 1973 to 58.33 % in 2012 (Ramachandra et al, 2012) and 73.72% in 2013 (Table 1). Bengaluru, once branded as the Garden city due to dense vegetation cover, has seen its green cover decline from 68.27% (1973) to less than 15% (2013). Like vegetation, Bengaluru was also known as City of Lakes for its numerous lakes (209 +/- lakes). The impact of urbanization has diminished lake bodies (93 lakes as per 2011) (Figure 2) and loss of feeder canals (rajakaluve). The water bodies have reduced from 3.4% (1973) to less than 1% (2013)(Ramachandra, Aithal, 2016).

Literature Review Literature Review 18 19

2.4 Increased Flooding Risks in Urban Areas

The last segment of literature review is focused on understanding the flooding risks caused by urbanization. Reviewing one of the articles published by Anil Gupta and Sreeja Nair, we find that Urban flooding in India, particularly in cities like Bangalore and Chennai, differs significantly from rural flooding due to impermeable catchments resulting from rapid urbanization. The Mumbai floods of July 2005 serve as a critical reference point, lasting seven weeks and affecting 20 million people, causing casualties, displacements, and extensive damage to homes and infrastructure(Gupta and Nair, 2011).

Subsequent urban flooding has become a recurrent issue in various Indian cities, including Ahmadabad, Bhopal, Bangalore, Chennai, Delhi, Gorakhpur, Hyderabad, Surat, Rohtak, and Kurukshetra. Factors contributing to these floods include heavy rainfall, dam-water release, inadequate drainage systems, housing in floodplains, and the loss of natural flood-storage sites. The unplanned and rapid urban development has strained natural ecosystems, making cities more vulnerable to disasters(Gupta and Nair, 2011).

Urbanization’s influence on basin runoff, marked by increased volume, elevated peak discharge, and reduced time of concentration, poses challenges to urban drainage. Climate change magnifies flood risks, underscoring the critical role of major drainage systems. Efficient urban drainage requires innovative design, litter management, and proper solid waste handling. Chennai, grappling with rapid population growth and expanding slums, faces difficulties in providing adequate motor able and parking space.

In densely populated urban areas, even minor floods carry the potential for substantial damage. Velocity floods, capable of causing building collapses, present severe threats. Climate change introduces complexities in pest and disease control, heightening concerns about water-borne diseases. Effective flood risk management necessitates comprehensive flood risk assessment, integrating urban criteria(Gupta and Nair, 2011).

Urban ecosystems, shaped by human interactions, respond to abiotic steering variables such as hydrology, water quality, and sediment load. The uncertainties arising from abrupt variability and changing rainfall patterns due to global climate change, coupled with the influence of local climate actors, contribute to flood disasters and water-logging-led epidemics. The reduction of urban wetlands in India by approximately 30% over the last 50 years diminishes their crucial role in mitigating downstream flooding(Gupta and Nair, 2011).

Literature Review Literature Review 20 21

Figure 7: Illustrations of Kere (Lake) in Bengaluru by Labonie Roy [source: Mongabay]

Figure 7: Illustrations of Kere (Lake) in Bengaluru by Labonie Roy [source: Mongabay]

03 Methodology and Research Approach

This research seeks to broaden existing literature by incorporating scholars’ theories and employing effective research methods. Some of the authors draw conclusions by building on prior work in the field or by making practical observations of wetland depletion, offering insights into the current situation. This approach enables readers to comprehend existing processes and theories, aiding the development of well-informed opinions grounded in established research. This chapter forms the cornerstone of the study, outlining the methods, data collection techniques, and analytical tools used to ensure the reliability and validity of the findings. It establishes a clear road-map for the research process, aligning with the study’s objectives and facilitating the critical evaluation of the results. The objective of this segment is to employ a mix of quantitative and qualitative data collection methods, coupled with an extensive literature review, to comprehensively understand the situation and suggest potential directions for future research. The methodologies utilized will include Analysis of Alterations in the Lake body and Shoreline, Lake Condition Analysis, Hydrological modeling, Stakeholder interviews and Government Agencies, and Data collection.

3.1 Analysis of Alterations in the Lake body and Shoreline

Analysis of the alterations of present lakes boundaries compared to the historical boundary is a crucial tool for urban infrastructure researchers to assess the existing distribution and configuration of wetlands within the urban landscape. By employing routes such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), remote sensing technologies or a clear comparison with the historical maps, one can identify key areas for conservation and potential sites for wetland restoration or creation. This analysis not only aids in making informed decisions about where and how to integrate wetlands into urban plans but also creates a platform for future researchers.

3.2 Lake Condition Analysis

It is crucial to understand the present condition of lake in terms of its pollutant levels and causes. This could also include the biodiversity assessments to understand the ecological value of such lakes. By prioritizing biodiversity conservation and reclamation , designers can create urban environments that not only function as human habitats but also support thriving ecosystems.

3.3 Hydrological Modeling

Hydrological modeling is a critical tool for understanding the water dynamics of urban wetlands. By understanding the simulation patterns of water flow, designers can assess flood risks, evaluate the effectiveness of proposed interventions, and ensure that wetlands are integrated in ways that enhance urban resilience to flooding events. This modeling informs the design of sustainable drainage systems and flood management strategies.

3.4 Stakeholder Interviews and Government Agencies

Engaging stakeholders, including local communities, environmental organizations, and government agencies, is essential for successful urban wetland conservation. Urban designers must facilitate participatory processes that involve stakeholders in the design decision-making. By understanding the needs, concerns, and aspirations of various stakeholders, it could be easier to develop solutions that are socially inclusive and culturally sensitive.

3.5 Data Collection and Analysis

Urban designers must gather comprehensive data on wetland ecosystems, including ecological, hydrological, and socio-economic data. This data serves as the foundation for evidence-based design decisions. Through rigorous analysis, designers can identify patterns, relationships, and opportunities that inform the development of effective conservation strategies.

Methodology & Research Approach Methodology & Research Approach 24 25

With the understanding of the above terms and methods, this research will further expound on existing literature findings and present a case study focusing on Sampangi Lake and Bellandur Lake in Bengaluru, aiming to discern its present conditions and efforts made to reclaim these lakes.

The latter could be accomplished through various means, and one approach I am taking involves comparing historical and present land use maps. The alterations would be correlated with the decline of water bodies. These changes will be analyzed across the different stages of urbanization, starting from the city’s inception to the various development phases, up to the present era of IT & BT revolution. Essentially, the goal is to evaluate the evolution of spatial patterns over time and their correlation with changes in biodiversity. This analysis will be complemented by multiple interviews and assessments from residents residing near urban wetlands, ultimately aiming to provide research insights for practical implications in wetland conservation.

Methodology & Research Approach 26

Figure 8: View of Ulsoor lake [source: Wikipedia]

04 Contextualization

To address urban wetland loss effectively, research must move beyond a generalized understanding and embrace contextualization. By incorporating insights from local ecology, socioeconomic dynamics, governance structures, and climate considerations, researchers can provide nuanced recommendations for policymakers and urban planners. One might also look at the urban design perspective, where implications necessitate a paradigm shift in the way wetlands are perceived and integrated into urban planning processes. Designers must recognize wetlands as valuable assets that contribute to the resilience and sustainability of cities. This involves envisioning wetlands as multi functional spaces that not only provide ecological benefits but also serve as cultural and recreational hubs within the urban environment(Ahern, 2013).

In a broader context, the literature review provides insights into the diverse methodologies employed by various organizations and governmental bodies for the restoration and reclamation of wetlands that have been lost or acquired. Given the comprehensive nature of this research, it becomes both challenging and imperative to focus on specific instances as case studies. This narrowing down is essential to gain a precise comprehension of wetland depletion and to propose reclamation methods if deemed necessary.

In the upcoming section, we will aim to examine Bengaluru’s lake and its management procedures and urban ecology visions and then the following section conducts a comparative analysis with existing research. Towards the end, discussions will offer perspectives on bridging the gap between research outcomes and their implications for urban design

4.1. Bengaluru and its wetland management

4.1.1 Current Scenario Of lakes

Rapid urbanization has transformed many lakes in Bangalore into urban utilities. Out of the 231 lakes in the city, 57 (8% of the total lake area) have dried up, impacting agricultural activities. The causes include the loss of storm water drains, over-exploitation of groundwater, siltation reducing rainwater storage capacity, and increased recharge and evapotranspiration (laset, no date).

Dry lakes pose threats of flooding, groundwater recharge, and micro climate stabilization. Bangalore has 174 perennial lakes (92% of the total lake area), with pollution rendering it most unsuitable for domestic use. Domestic wastewater discharge has led to eutrophication, reduced dissolved oxygen, and affected aquatic life. Sequential water quality degradation has turned lakes into urban utilities, recharging, and contaminating groundwater. Some lake areas are still used for irrigation, fishing, and cattle washing. Despite contributing to climate regulation and attracting migratory birds, pollution and sewage threaten the ecological balance. While 24 lakes (25% of the total lake area) have been rejuvenated, eight show no improvement due to untreated sewage discharge. Road and railway networks have divided seven lakes, caused storm water connection loss and dried. Smaller isolated lakes face extinction due to neglect and high maintenance costs. Thirty-five lakes in semi-urban areas and 26 in urban areas are spoiled from untreated water discharge, posing significant threats without underground sewer lines (laset, no date).

Contextualization Contextualization 28 29

Figure 9: View of non-maintained Bellandur lake in Bengaluru [source: Wikipedia]

4.1.2 Status of Lakes in Bengaluru

The natural topography of Bangalore, with hills and valleys, provides an ideal setting for the creation of lakes to capture and store rainwater. The city’s three major valleys, Hebbal, Koramangala-Challaghatta, and Vrishabhavati, are highlighted. Due to the semi-arid climate, the city’s founders strategically utilized streams to form man-made lakes, damming them at suitable locations. These lakes are interconnected in chains within each valley, with each lake collecting rainwater from its catchment area. The excess water flows downstream, spilling into the next lake in the chain, creating a reservoir system in each of the three valleys (Ramesh and Krishnaiah, 2013).

4.1.3 Status of water quality of Bengaluru lakes

A study conducted by the Lake Development Authority in Bangalore in 2001 assessed the water quality of 37 selected lakes across the city’s three valley systems under BBMP jurisdiction. The findings revealed that the dissolved oxygen content in several lakes, including Hebbal Lake, Sankey Tank, and others, fell below the tolerance limit of 4.0 mg/l. Additionally, the Biochemical Oxygen Demand (5 days at 20 °C), with a maximum tolerance limit of 3.0 mg/l, indicated that many water bodies had reached or exceeded the tolerance limit.

4.1.4 Lake Management and proposed actions

The benefits of wetlands are recognized globally, yet they remain a subject of apathy in Indian cities. Although many government and state agencies have wetlands under the domain of responsibility, unclear and overlapping jurisdictions between them have caused significant losses of urban wetlands(Verma, 2023).

The research shows that the upkeep of lakes in Bengaluru has proven to be a challenging task due to the fragmented ownership and responsibility across various government bodies. The IDIP Report, crafted by STEM for KUIDFC, reveals that out of 117 recognized lakes, 97 are owned by the Forest Department, 13 by the Minor Irrigation Department, and the rest by entities like the Bangalore Mahanagara Palike, BDA, CMCs, Panchayats, etc.(DSouza, 2006).

The proliferation of stakeholders with ownership and maintenance responsibilities has resulted in a lack of coordinated efforts. Each department tends to deflect responsibility, leading to the deterioration of many lakes due to encroachment or pollution. Consequently, only 33 lakes remain visible, with a mere 15 showing signs of being relatively healthy water bodies. This poses a severe threat not just to ecology and biodiversity but also to the livelihoods of traditional lake users, whose well-being is intricately tied to the health of these water bodies(DSouza, 2006).

In general, Bengaluru as such is governed by various entities. Different water bodies fall under the jurisdiction of different entities and hence the question of authority is a complex one. Besides what purpose does each water body serve also needs consideration. With increased urbanization and change in lifestyles, it can be assumed that very few lakes in Bangalore city limits are used as a direct source of water for daily/livelihood needs. But this generalization is based on a biased middle/upper class view of the situation.

[source:BBMP Lakes department]

Contextualization Contextualization 30 31

Figure 10: Snippet of future projects under lake development authority

4.2. Comparative Analysis with Existing Research

Comparing the current research with established studies on conserving urban wetlands offers valuable insights for Bengaluru’s urban designers. By examining successful global case studies, designers can extract effective principles and strategies that strike a balance between urban development and wetland preservation. In addition to the earlier-reviewed literature in this paper, we could also now explore live examples or recent case studies that have been put into practice. Unlike decades ago, this approach was less accessible due to the extended observation periods required. Today, researchers and urban planners can directly derive conclusions from methodologies employed in recent years, providing a more immediate and insightful perspective. For instance, the Cheonggyecheon Restoration Project in Seoul, South Korea, demonstrates the trans formative potential of rehabilitating urban water bodies. By uncovering and restoring a buried stream, Seoul not only enhanced biodiversity but also revitalized the surrounding urban area, creating a vibrant public space (Lee et al., 2014). By leveraging more similar case studies, urban designers and wetlands conservation department in Bengaluru can adapt successful strategies to the local context, considering the unique socio-cultural, ecological, and infrastructural conditions of the city.

4.3. Bridging the Gap Between Urban design infrastructure and Wetland Ecology

In the field of urban planning and design, professionals have embraced the sustainability challenge through various initiatives such as visioning competitions, pilot projects, and certification programs like LEED, LID, and Sustainable Sites. These efforts primarily focus on the spatial arrangement of urban structures, energy efficiency, and materials, addressing urban sustainability by (re)organizing urban form and spatial patterns. Urban planners and designers, with their expertise in urban form, have traditionally understood the pattern: process dynamic and applied it to tackle sustainability issues. However, a notable drawback in green infrastructure projects is the lack of post-implementation monitoring of claimed ecosystem services. Future research collaborations between landscape ecologists and urban professionals should prioritize developing an adaptive design approach, fostering a “learn-by-doing” method. Designers aspire to integrate landscape ecology into urban projects but face challenges in closing the learning loop to understand project outcomes, compare alternative solutions, and assess the transferability of results (Ahern, 2013).

Contextualization 32

Figure 11: illustrations of lake pollution in Bengaluru by Labonie Roy

Case Research: Lakes of Bengaluru

The preceding chapters have established a robust groundwork by examining the objectives, limitations, literature review, and methodology of the study. In this concluding chapter, I will delve into two historically significant lakes, treating them as case studies for analysis based on the categories outlined in the methodology section. A detailed examination of these lakes, affected by rapid urbanization and neglect, is crucial for a comprehensive understanding.

Within the Bengaluru Lake scape, I have selected two notable lakes for investigation. The first is Sampangi Lake, which, decades ago, fell victim to intense urbanization and now exists as a sports stadium in the city center. Currently, no traces of the original lake remain, as its bed has been re purposed to accommodate a substantial structure. The second site is Bellandur Lake, one of the largest lakes in Bengaluru. Unfortunately, it has become non-functional and has been entirely neglected by the authorities, despite concerns and inquiries raised by the nearby residents.

5.1. Bellandur Lake

Bellandur Lake, the largest within Bangalore city, spans 892 acres and is situated at a latitude of 12°58’ N and longitude of 77°35’ E, with an altitude of 921 meters above mean sea level. The lake boasts a catchment area of 110.94 square miles or 287.33 square kilometers according to the Minor Irrigation Department. With a water storage capacity of 17.66 million cubic feet, the lake measures 3 kilometers in length and 2.75 kilometers in width. Positioned about 20 kilometers southeast of the city, it stands as one of Southeast Asia’s largest man-made lakes(‘Bellandur Lake,’ 2023).

The current state of Bellandur Lake is a far cry from its past glory when it served as a vital ecological zone for Bangalore. Originally a pristine water source, the lake stored storm water and operated as a natural treatment plant with diverse aquatic plants and animals. Functioning as the city’s “kidney,” it prevented the bio accumulation of organic waste(Ramesh and Krishnaiah, 2013). The lake was a habitat for a wide range of fauna and attracted migratory birds from various parts of the country. In addition to supplying drinking water to half the city’s population, Bellandur Lake was a significant fish trading center in earlier times. Consequently, it played a crucial role as an indispensable ecological zone in Bangalore.

Bellandur tank forms an integral part of the drainage system in Bangalore, catering to the drainage needs of the southern and southeastern regions of the city. It serves as a collection point for water from three distinct chains of tanks. The first chain, known as the eastern stream, originates in the north, specifically from Jaya mahal, and covers the eastern part of the city. The central stream, originating in the central region around K.R. Market, covers the central portion. The third chain, called the western stream, reaches the tank from the southwestern area. Subsequently, water from Bellandur tank flows eastward to the Varthur tank, then descends the plateau, ultimately finding its way into the Pinakani river basin (Ramesh and Krishnaiah, 2013).

Case Research Case Research 34 35 05

Figure 12: Image of Bellandur lake[source:Wikipedia]

5.1.1 Development Through the years: Spatial and Land use changes

Bellandur Lake in the 1980s

In the tardy 1970s, Bellandur Tank encountered pollution, and in the 1980s, encroachments affected the chain of tanks leading to Bellandur. Some of these encroachments were carried out with the knowledge of the authorities.

Challaghatta Tank, which is part of the chain originating from K.R. Market, was transformed into a golf course during Ramakrishna Hegde’s tenure as Chief Minister. Another tank, Appa Reddy Palya Kere, situated upstream of Challaghatta, succumbed to housing developments. Disruptions in the central and western streams occurred, causing a break in the chain, particularly noticeable from Puttenehalli in J.P. Nagar to Bellandur. The emergence of IT companies in Koramangala in the late 1980s escalated the demand for residential areas, thereby disrupting the continuity of the tank chain. The combination of these disruptions and unregulated development resulted in insufficient rainwater reaching the tank, with untreated sewerage dominating its composition. This led to a decline in aquatic life, adversely affecting the fishing community, even though the tank’s water continued to be utilized for irrigation purposes

Bellandur Lake in the 1990s

In the 1990s, Bangalore witnessed intensified urbanization, driven by the Information Technology (IT) boom and the establishment of industrial parks like ITPL and Electronics City. This growth created a higher demand for land, water, electricity, and infrastructure, placing increased pressure on areas like Bellandur tank due to its proximity to major IT parks. The Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) proposed a ring road connecting ITPL to Electronics City, leading to local resistance in Bellandur against both the ring road construction and tank pollution. Farmers formed the Raitha Horatta Samiti in 1997 to oppose land acquisition for the ring road, resulting in some alterations to the BDA’s plans. Despite their efforts, the ring road was completed in 2000. Simultaneously, another struggle emerged to save the tank from pollution, initiated by Jagannath Reddy, the Panchayat president, and supported by environmental activists.

The media’s interest grew after Bellandur Lake was rejected as a venue for the National Games due to pollution. Villagers protested the BWSSB at the Challaghatta sewerage treatment plant, and legal action was taken, leading to improvements in the Sewerage Treatment Plant. Although untreated sewerage persists, the community’s efforts have raised awareness and prompted authorities to address the issue. Legal proceedings, including a Lok Adalat case, focus on household and industrial pollution in Bellandur tank, scrutinizing measures taken by government bodies like BBMP, BWSSB, and the Pollution Control Board for control and mitigation.

Bellandur Lake in the 2000s & Present

The Bellandur tank, once integral to local communities, is now in a state of decline. Large portions are covered by weeds, and the water appears dark and opaque with a foul stench. The absence of birds near the tank and visible foaming downstream indicates the presence of effluents. Studies conducted on water quality highlight the alarming pollution levels. A 2000 study by Sreekantha and K.P. Narayana reveals a high concentration of chemical substances, rendering the water unfit for human consumption. Another 2003 study by Chandrasekhar JS, Lenin Babu K, and Somasekhar RK from Bangalore University emphasizes the adverse impact of urbanization, transforming the lake from a natural, ecologically healthy state to an artificial reservoir filled with domestic sewage and industrial effluents.

5.1.2 Present Biodiversity condition of Bellandur Lake

Years of unchecked waste disposal have turned Bellandur Lake into an environmental disaster. Sewage and wastewater discharge, along with the dumping of solid waste into storm water drains, have contaminated the lake with raw sewage, industrial effluents, and household garbage. Unplanned areas lacking proper sewerage systems contribute to sewage discharge into drains. The presence of 339 slums within corporation limits, comprising 93,348 hutments and a total population of 5,03,559, highlights the scale of the issue(Ramesh and Krishnaiah, 2013). Additionally, converted revenue land into housing layouts lacks sanitary sewers, emphasizing the negative impact of industrialization, urbanization, and unplanned growth on Bellandur Lake pollution.

Case Research Case Research 36 37

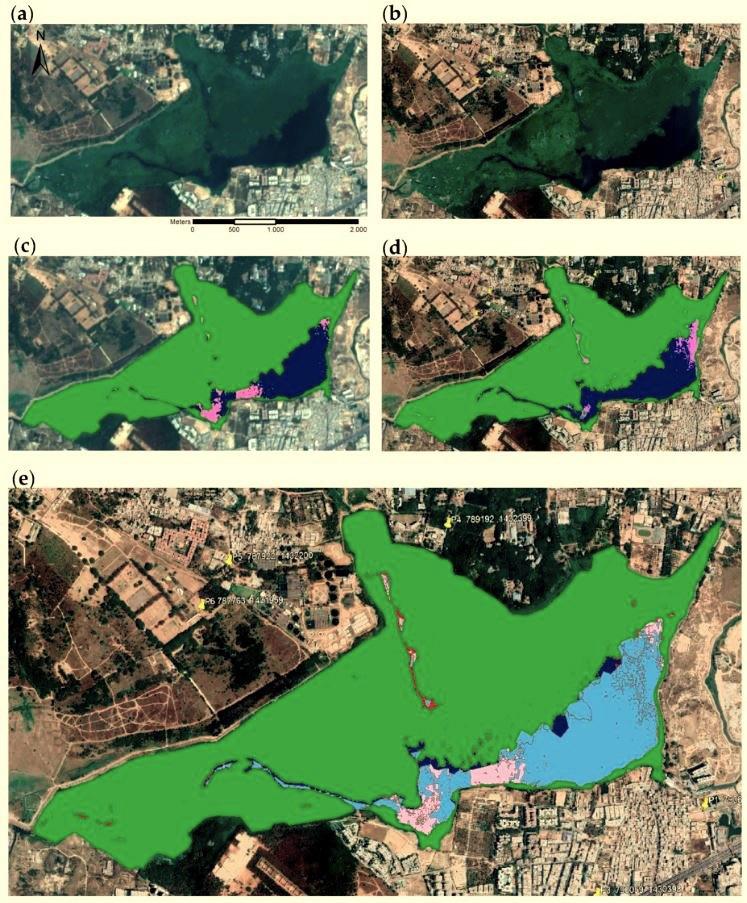

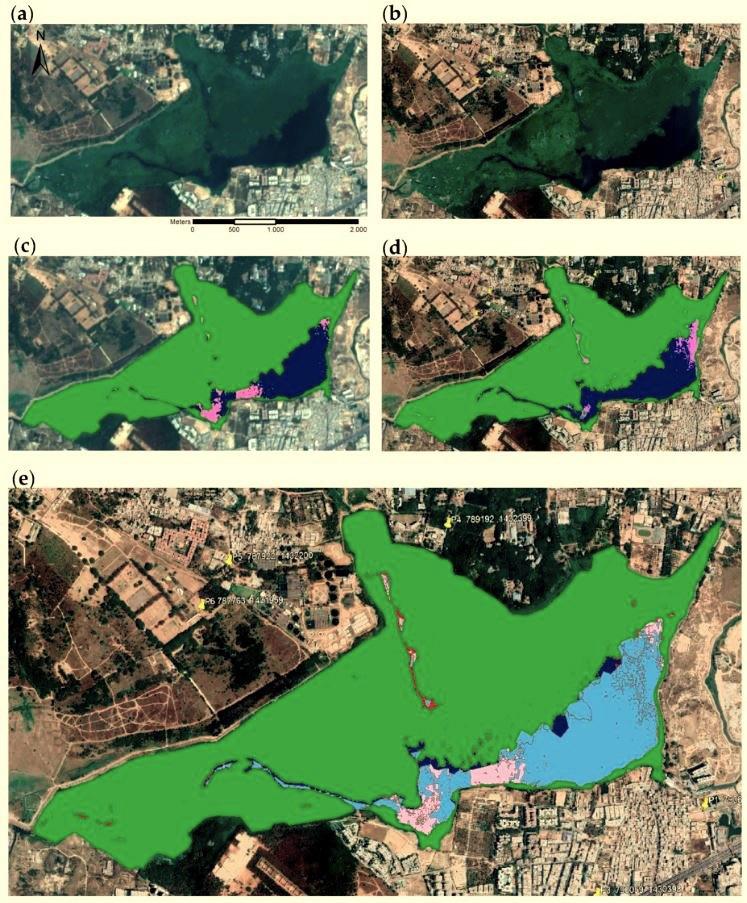

Sentinel-2 (a,b) and Google EarthTM (c–e) images of Bellandur Lake (Bengaluru, India) of 20 March 2019 with corresponding lake surface cover classification results for multispectral Sentinel image (b) and RGB Google image (d). Cover classes include macrophytes (green), algae (pink), and open water (blue). The image below (e) illustrates missing algae (red) and missing or shifted open water (dark blue) areas of the Sentinel-2 image classification.

5.1.3 Responses of Government agencies

The deteriorating state of Bellandur tank reveals a lack of effective response from various government agencies. Abuses, such as dumping sewerage, effluents, and solid waste, along with wetland and tank bed encroachments, remain unaddressed. Legal actions in the Lok Adalat highlight the inadequate efforts of bodies like BBMP, which focuses on court-directed measures for stormwater drains. BWSSB admits underutilization of Sewerage Treatment Plants, projecting increasing sewerage volumes. The Pollution Control Board suggests relocating industries but fails to clarify responsibility. The Fisheries Department reacts minimally, ceasing fishing licenses due to pollution. The Minor Irrigations Department lacks a coherent plan, and the Lake Development Authority shows little progress in bio-remedial measures. The shifts in control suggest a reconfiguration of resource access and usage, with local communities having diminished influence compared to governmental bodies and the judiciary. The affluent residents of Koramangala also play a role, seeking changes to protect their properties from flooding. The Bellandur panchayat’s notice to government bodies demonstrates an attempt to safeguard the common resource by elected officials familiar with the local challenges.

Case Research Case Research 38 39

Figure 13: Map showing the variations in lake boundary of Bellandur lake [source: author]

Figure 14: Image showing the flames coming out of burning chemical froth of Bellandur lake [source: The Guarding Newspaper]

5.1.4 Comments, Suggestions in newspaper and Stakeholder involvement

In March 2013, a social worker from Bellandur, Kasu Venkata Rajagopala Reddy, filed a petition in the High Court, highlighting the pollution of Bellandur Lake due to the malfunctioning Sewage Treatment Plant (STP) set up by the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB). The petitioner emphasized the adverse effects on water quality, rendering it unfit for consumption and agriculture. Another news report mentioned the threat of oil pollution in Bellandur Lake, likely from industrial waste, garbage, and sewage. Several efforts, including a 13-year-long plea for action called the “Bellandur Lake Run,” aimed to restore the lake, addressing pollution caused by untreated sewage. Despite legal interventions and petitions, the contamination issue persisted, posing health hazards and environmental problems. These reports underscored the urgent need for coordinated measures to halt the pollution of Bellandur Lake.

Overall, the urban development department also had intentions to engage a Mumbai-based organization to assess the issues of Bellandur Lake and propose rehabilitation measures. However, there has been no progress in this regard. In February of this year, the Bellandur gram panchayat filed a contempt of court petition against the state government and relevant agencies, but the case is still pending. Despite multiple attempts by the village panchayat to prevent lake contamination, there has been no improvement. Current activities around the lake do not include recreational activities, but villagers use the water for cattle grazing and irrigation. The 950-acre lake poses a significant health hazard to those in its vicinity, extending as far as Koramangala and the airport road. Besides contaminating underground aquifers, it serves as a substantial breeding ground for mosquitoes. Unless all concerned agencies collaborate on effective measures to curb contamination, any cleaning efforts will likely be futile.

5.1.5 Discussion

The disconnection of traditional residents from Bellandur tank appears to be nearly total, leaving them with little influence in safeguarding the tank and causing a breakdown in their connection to it. Previously, local communities, through their use and association with the tank, could assert some ownership claims over it. However, the ownership of tanks in Bangalore, including Bellandur tank, lies with various government departments, such as the Minor Irrigations department. The public trust doctrine, treating the state as a trustee of commons, has translated into ownership and control over common property resources in the context of Bangalore’s tanks.

The situation at Bellandur tank reflects the alienation of local communities on two fronts. Firstly, pollution, encroachment, and subsequent degradation of the common property resource have distanced the communities. Secondly, lacking ownership or rights, they are unable to initiate positive actions for the tank, and any such action needs to be facilitated through the government bodies holding ownership. These departments, lacking direct livelihood or social stakes, often exhibit a lack of proactive engagement in matters related to resource protection.

To understand the status of pollution, restoration, and management of Bellandur Lake in the Bangalore Metropolitan city, it is crucial to conduct systematic environmental studies. Currently, there has been a lack of comprehensive environmental assessments. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct step-by-step studies, including assessments of Characteristics, Status, Effects (on surrounding Groundwater, Soil, Human health, Vegetables, Animals, etc.), and addressing degradation issues. Additionally, it is essential to prepare a conceptual design for the restoration and management of the lake.

Case Research Case Research 40 41

5.2. Sampangi Lake

The Sri Kanteerava Stadium in Bengaluru, Karnataka, stands near what was once the expansive Sampangi Lake. Over a century ago, this lake served as a crucial water source for both the British Cantonment and the native city (Pete), benefiting from its central location. However, with the introduction of the Hesarghatta reservoir in 1898, the British Cantonment no longer relied on Sampangi Lake for water(Gibson, 2020).

Subsequently, the lake’s significance shifted from utility to aesthetics and recreation. Livelihoods like brick making were prohibited to maintain the lake’s visual appeal, leading to the displacement of local communities such as fishers and washers. The lake’s accessibility became restricted, prompting the migration of these communities, while new ones, engaging in livelihoods unrelated to the lake’s ecosystem services, took their place.

Notably, British polo players advocated for draining the lake to facilitate polo matches on its bed. Despite opposition from horticulturists who petitioned the Mysore king, the lake was eventually drained, and by the end of 1937, the once 35-acre lake had been transformed into a small tank, marking a significant alteration in its use and landscape(Gibson, 2020).

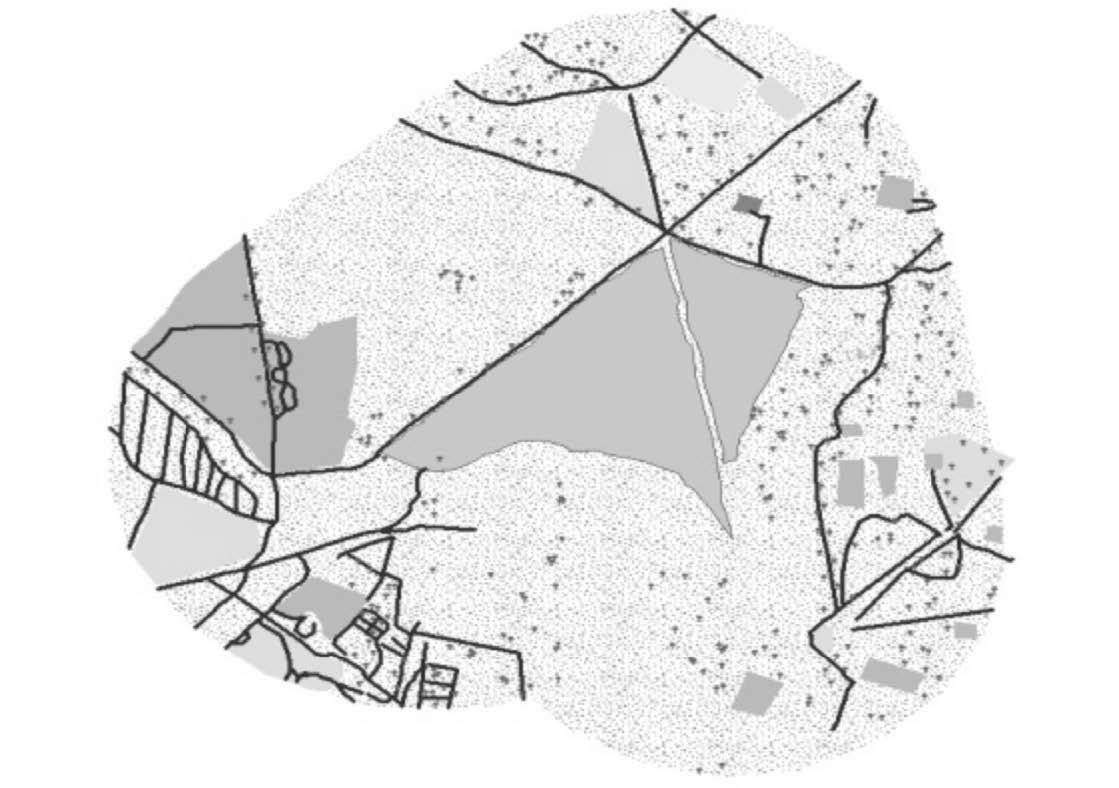

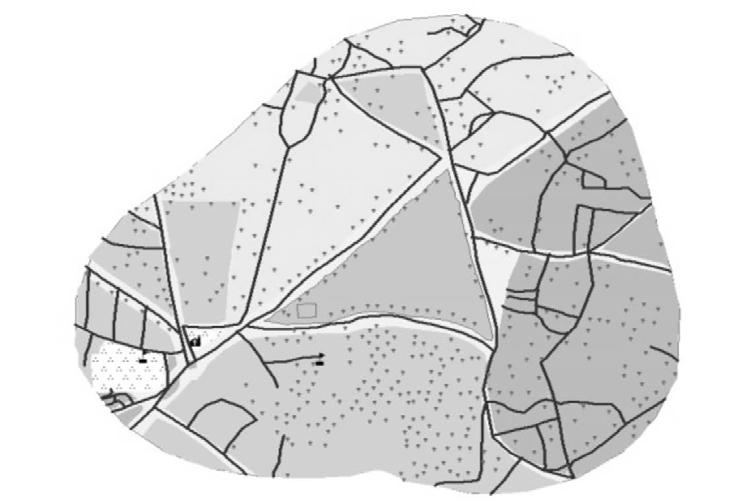

5.2.1. Sampangi Lake, in the Pages of History

In 1885, Sampangi Lake in Bengaluru was a sizable water body surrounded by open spaces. Nearby were St. Marthas and Maternity hospitals, a brewery, residential areas, educational institutions, a cemetery, and places of worship. By 1935, the landscape had transformed with increased urbanization, roads, and the conversion of the lake into a playground and golf course. A temple was built, hosting the annual Karaga festivities. Post-independence in 1973, urbanization continued, making it challenging to distinguish between residential and commercial spaces. The Kanteerava Indoor Stadium replaced most of the lakebed. Between 1973 and 2013, the area became a commercial hub, with the Kanteerava Stadium undergoing renovations. Tree covers diminished, existing mainly in small pockets like parks.

Historical accounts reveal that in the late 1870s, the lake area was known for horticultural achievements by the Vanhikula Kshatriyas. By 1957, cattle fairs suggested partial drying of the lake, and the surroundings saw significant changes, transforming into housing colonies or government offices by the 1950s. The period from 1884 to 1935 witnessed a sweeping transformation in the lake’s vicinity, as evidenced by archival documents and historical studies. In contemporary Bengaluru, the surroundings of Sampangi Lake have undergone significant changes, deviating from its historical social and ecological significance. Currently, only a modest rectangular tank persists, primarily revered for its centrality to the Karaga festival—the city’s oldest celebration, embraced by the Vanhikula Kshatriyas horticulturists. The water body, once of year-round importance, now becomes a focal point exclusively during Karaga, transforming into a site of jubilation and drawing crowds in the thousands.

Case Research Case Research 42 43

Figure 15: Image showing the view of remains of Sampangi river [source: author]

Case Research Case Research 44 45

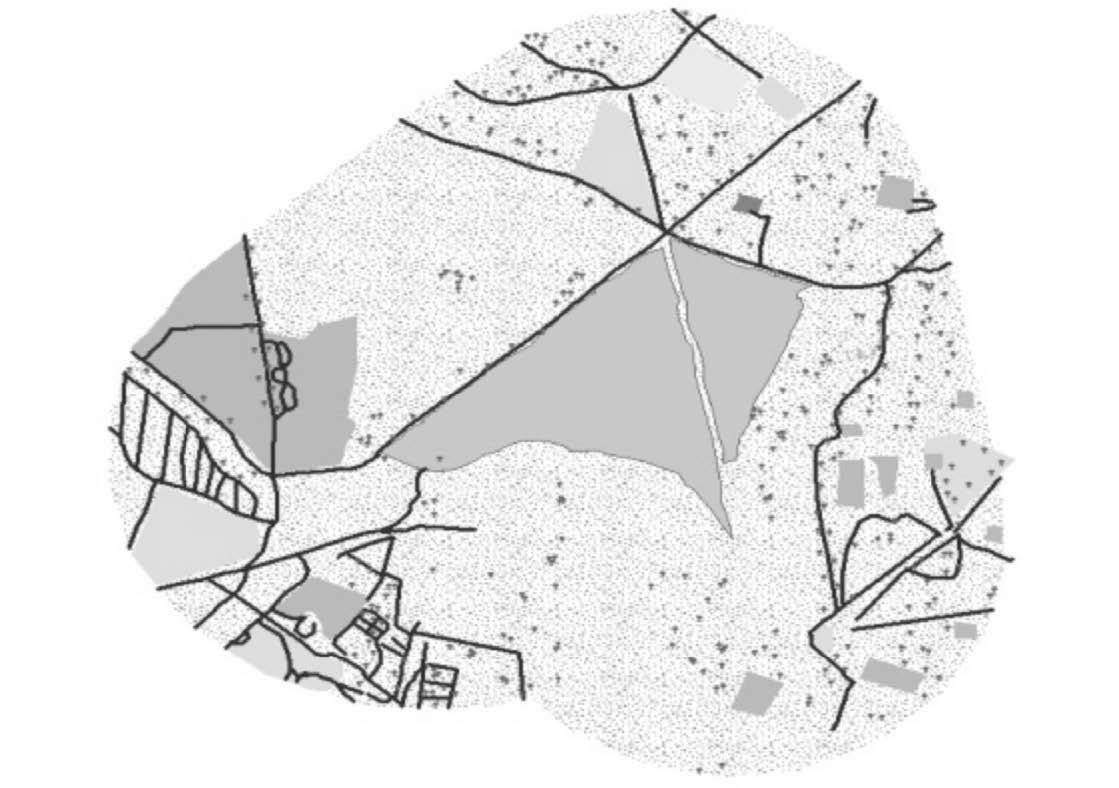

Figure 16: Set of images showing the transformation of Sampangi lake between 1885 and 2013 [source: author]

Sampangi and its surroundings 1885

Sampangi and its surroundings 1973

Sampangi and its surroundings 2014

Sampangi and its surroundings 1935

5.2.2. Sampangi Lake: Evidence from Archival Document

Between 1884 and 1935, Sampangi Lake in Bengaluru underwent significant transformations, and an analysis of archival documents from 1884 to 1912 provides insights into the dynamic landscape surrounding the lake. Initially, the lake served as a vital water source for the Civil and Military Station, leading to debates and disputes over its status and utility.

During this period, the lake faced challenges related to water supply, with two feeder channels providing water to neighboring tanks, including Millers Tanks I, II, and III. The lake’s significance was evident in the disputes, such as an 1883 disagreement between the Civil and Military Station regarding water supply from the feeder channels. Resolutions in 1884 restricted the deepening of the tank bed due to concerns about brick making and the potential impact on the landscape(Unnikrishnan and Nagendra, 2014).

Aesthetic considerations gained prominence as British polo players sought to drain the lake for a polo ground. Debates ensued over protecting buildings, breweries, and the polo ground, showcasing a shift from utilitarian to recreational priorities. The focus on aesthetics was reinforced by concerns about unsightly pits and the protection of buildings, breweries, and polo grounds. The evolving dynamics involved various stakeholders, including local communities, polo players, and the municipality. The power struggles reflected a broader trend of prioritizing recreational and aesthetic considerations over traditional utilitarian uses of the lake. The debates continued, addressing issues such as drainage, malarial infections, and flooding.

By 1935, the lake underwent a significant transformation, being drained and converted into a playground. The archival records from this period, represented by File Numbers 154 of 1935, discuss the ownership of the tank bed and the tank itself. However, specific details regarding this conversion were not found in the available records.

The historical events surrounding Sampangi Lake highlighted the complex interplay of power dynamics and changing priorities in the landscape of Bengaluru.

The recurrent theme of favoring aesthetic and recreational values over utilitarian needs demonstrated a broader trend in decision-making regarding urban water bodies.

The debates and decisions shaped the fate of Sampangi Lake, reflecting the evolving socio-cultural and political landscape of the city.

5.2.3. Discussion

Sampangi Lake in Bengaluru underwent a profound transformation from a crucial water source for the British Cantonment and native city to a symbol of aesthetic and recreational aspirations between 1884 and 1935. Initially serving utilitarian needs, the lake faced disputes over water supply and restrictions on activities like brick making. The arrival of the Hesarghatta reservoir in 1898 diminished its utilitarian role, leading to a shift towards aesthetic and recreational values.

Sampangi Lake’s surroundings continuously evolved. From a playground and golf course to the Kanteerava Indoor Stadium, the landscape underwent successive alterations, illustrating the dynamic growth and changing priorities of Bengaluru. Urbanization, commercialization, and diminishing tree cover reshaped the area, deviating from its historical significance. Sampangi Lake exists as a modest rectangular tank, primarily revered during the Karaga festival. The once year-round lifeline now serves as a site of cultural celebration, emphasizing its enduring importance to specific communities despite its altered form.

The case study not only highlights the physical transformation of Sampangi Lake but also unveils a broader narrative of urbanization, socio-cultural shifts, and the complexities of decision-making regarding urban water bodies. The lake stands as a historical witness to the evolving relationship between cities and their water resources, showcasing the diverse and dynamic nature of urban development.

Case Research Case Research 46 47

06 Conclusion

This research paper offers a comprehensive exploration of the intricate dynamics involving urban wetland conservation, the historical significance of lakes, rapid urbanization, biodiversity loss, and policies for reclaiming lost lakes, accompanied by general interviews. The findings have significant implications for various stakeholders, including urban planners, designers, policymakers, and the general populace of Bengaluru.

The study brings to light the alarming extent of urban wetland loss in Bengaluru, attributing it to factors like land-use transformations, encroachments, and pollution. The repercussions of this depletion extend across the ecological, social, and economic fabric of the city. Failing to address this issue could result in further environmental degradation and a diminished capacity of urban ecosystems to provide essential services.

Examining case studies of Sampangi Lake and Bellandur Lake, the research illuminates the intricate relationship between urban development, community engagement, and environmental sustainability in the context of water bodies. Sampangi Lake’s transformation signifies Bengaluru’s evolving priorities, shifting from utilitarian to aesthetic values, showcasing the city’s dynamic growth and commercialization. In contrast, Bellandur Lake highlights a disconnection between traditional residents and the tank, emphasizing challenges associated with common property resources. Pollution and encroachment underscore the need for community involvement, yet centralized ownership by government departments hampers proactive engagement.

These case studies underscore the importance of a holistic approach to urban water management, advocating for the integration of community participation, comprehensive assessments, and strategic restoration plans. Sampangi Lake’s historical testament and Bellandur Lake’s challenges contribute valuable insights to sustainable urban development, emphasizing the need to balance utilitarian needs with aesthetic values, involve communities, and establish effective governance for urban water bodies globally facing similar challenges.

Furthermore, the study addresses the profound ecological consequences of declining biodiversity within urban wetland ecosystems. The loss disrupts the delicate balance, diminishing the capacity to purify water, provide habitats for diverse species, and regulate local climates. This degradation of ecosystem services has ripple effects on the overall well-being and resilience of urban areas.

Most crucially, the dissertation stresses the urgent need to integrate wetland conservation into the heart of urban planning and design processes. Recognizing wetlands as integral components of green-blue infrastructure can significantly enhance a city’s capacity to absorb and recover from environmental stressors. Preserving wetlands equips cities to withstand challenges like floods, water scarcity, and the impacts of climate change.

The study also emphasizes the critical importance of inclusive and participatory approaches to urban wetland conservation. Engaging local communities, non-governmental organizations, academic institutions, and governmental agencies in collaborative efforts fosters a sense of shared responsibility for wetland preservation, strengthening social cohesion and amplifying the impact of conservation initiatives.

In conclusion, this dissertation not only establishes a robust foundation for advancing wetland conservation efforts in Bengaluru’s urban context but also provides valuable insights applicable to urban areas globally facing similar challenges. By synthesizing research findings, policy recommendations, and design strategies, this work aspires to offer a road map for enhancing urban resilience and sustainability through the preservation of diminishing lakes.

Conclusion Conclusion 48 49

Ahern, J. (2013) ‘Urban landscape sustainability and resilience: the promise and challenges of integrating ecology with urban planning and design.’ Landscape Ecology, 28(6) pp. 1203–1212.

Alikhani, S., Nummi, P. and Ojala, A. (2021) ‘Urban Wetlands: A Review on Ecological and Cultural Values.’ Water. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 13(22) p. 3301.

‘Bellandur Lake’ (2023) Wikipedia.

Brinkmann, K., Hoffmann, E. and Buerkert, A. (2020) ‘Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Urban Wetlands in an Indian Megacity over the Past 50 Years.’ Remote Sensing. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 12(4) p. 662.

Brownstein, D. (2021) Bangalore’s Disappearing Lakes. Guerrilla Cartography. [Online] [Accessed on 26th November 2023] https://www.guerrillacartography. org/blog.

DSouza, R. (2006) ‘Research Study to Assess the Impact of Privatisation of Water Bodies in Bangalore.pdf.’ Centre for Education and Documentation, January.

Gibson, L. (2020) ‘Sampangi Lake: The Tale of how a Lake became a Stadium.’ Lakes of India. 12th October. [Online] [Accessed on 29th November 2023] https://lakesofindia.com/2020/10/12/sampangi-lake-the-tale-of-how-a-lakebecame-a-stadium/.

Gupta, A. K. and Nair, S. S. (2011) ‘Urban floods in Bangalore and Chennai: risk management challenges and lessons for sustainable urban ecology.’ Current Science. Temporary Publisher, 100(11) pp. 1638–1645.

Iaset (no date) ‘DETECTION OF DECLINE IN THE EXTENT OF LAKES IN BANGALORE CITY USING GEOSPATIAL TECHNIQUES.’ ICEM (2023) Managing Climate Risks In Wetlands. New Delhi.

Kundzewicz, Z. W., Kanae, S., Seneviratne, S. I., Handmer, J., Nicholls, N., Peduzzi, P., Mechler, R., Bouwer, L. M., Arnell, N. and Mach, K. (2014) ‘Flood risk and climate change: global and regional perspectives.’ Hydrological Sciences Journal. Taylor & Francis, 59(1) pp. 1–28.

Lee, C.-H., Lee, B.-Y., Chang, W. K., Hong, S., Song, S. J., Park, J., Kwon, B.-O. and Khim, J. S. (2014) ‘Environmental and ecological effects of Lake Shihwa reclamation project in South Korea: A review.’ Ocean & Coastal Management. (The Korean Tidal Flat Systems: Ecosystem, land reclamation and struggle for protection), 102, December, pp. 545–558.

Mitsch, W. J. and Gosselink, J. G. (2015) Wetlands. John wiley & sons.

MoEFC, M. of E., Forest and Climate Change (no date) India’s Wetlands of International Importance. Wetlands of India Portal. [Online] [Accessed on 26th November 2023] https://indianwetlands.in/wetlands-overview/indiaswetlands-of-international-importance/.

Prasad, S. N., Ramachandra, T. V., Ahalya, N., Sengupta, T., Kumar, A., Tiwari, A. K., Vijayan, V. S. and Vijayan, L. (2002) ‘Conservation of wetlands of India-a review.’ Tropical Ecology. Varanasi, India [etc.] International Society for Tropical Ecology, 1961-, 43(1) pp. 173–186.

Rajashekara, S. and Venkatesha, M. (2017) ‘Impact of threats on avifaunal communities in diversely urbanized landscapes of the Bengaluru city, south India.’ Zoology and Ecology, 27, December, pp. 202–222.

Ramachandra, Aithal, T. V., Bharath (2016) ‘Decaying lakes of Bengaluru and today’s irrational decision makers,’ October.

Ramachandra, T. V., Asulabha, K. S. and Lone, A. A. (2014) ‘Wetlands of greater Bangalore, India: automatic delineation through pattern classifiers.’ Journal of Biodiversity. Routledge, 5(1–2) pp. 33–44.

Ramachandra, T. V., Sudarshan, P., Vinay, S., Asulabha, K. S. and Varghese, S. (2020) ‘Nutrient and heavy metal composition in select biotic and abiotic components of Varthur wetlands, Bangalore, India.’ SN Applied Sciences, 2(8) p. 1449.

Ramesh, N. and Krishnaiah, s (2013) ‘Scenario of Water Bodies (Lakes) In Urban Areas-A case study on Bellandur Lake of Bangalore Metropolitan city.’

Secretariat, R. C. (2016) An Introduction to the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, 7th ed. Gland, Switzerland.

Unnikrishnan, H. and Nagendra, H. (2014) ‘Unruly Commons: Contestations around Sampangi Lake in Bangalore Nehru Memorial Museum and Library 2014.’ NMML Occasional Paper, January.

Unnikrishnan, Hita and Nagendra, H. (2018) ‘The Lost Lakes of Bangalore.’ Environment & Society Portal, May.

Verma, N. (2023) ‘Urban Wetlands in India Need Urgent Attention.’ Observer Research Foundation.

References References 50 51 07

References

Figure 7: Illustrations of Kere (Lake) in Bengaluru by Labonie Roy [source: Mongabay]

Figure 7: Illustrations of Kere (Lake) in Bengaluru by Labonie Roy [source: Mongabay]