Let’s plant the seeds for our future together Your idea of growth happens here

Let’s plant the seeds for our future together Your idea of growth happens here

Publishers:

Gurvinder Singh

Ramneek Singh

Editor:

Ancy Mendonza

Contributing Writers:

Ancy Mendonza

Ekamjot Singh Deol

Harinder Singh

Harpreet Kaur Kang

Jasleen Kaur Brar

Dr. Joban Singh Bal

Naina Grewal

Natasha D’souza

Dr. Pargat Singh Bhurji

Graphic Designer:

Jaskaran Singh

Sumit Rai

Advertising & Sales:

Gurvinder Singh Hundal

Ramneek Singh Dhillon

Postmaster if undeliverable

By:

By Natasha D’souza

In Surrey, British Columbia, Hargun Dhillon, founder and president of the Age Strong Unity Wellness Society and co-founder of the Ignited Resilience Mentorship Foundation, is making waves as a changemaker who empowers the elderly and supports at-risk newcomer students. His journey showcases the power of South Asian values and the spirit of ‘seva. ’

Strengthening Generations: A Mission Rooted in Family

For Dhillon, community

service is more than just a passion—it’s a way of life.

Growing up in a Punjabi household, he witnessed the cultural emphasis on caring for elders. His journey to enhance elderly health began when his grandfather underwent multiple heart surgeries, revealing the hidden health challenges faced by South Asian seniors.

“My grandfather’s experience made me realize how overlooked structured physical activity and balanced nutrition are among South Asian seniors,” Dhillon shares. “Many elders lead seden-

tary lives, unaware of how small lifestyle changes can improve their health.”

Determined to bridge this gap, Dhillon started leading basic exercise routines for his grandparents. This initiative evolved into the Age Strong Unity Wellness Society, a nonprofit organization providing culturally tailored fitness classes to over 600 seniors in Surrey, Cloverdale, Abbotsford, Seattle, and even Punjab, India. Collaborating with institutions like the City of Surrey and Fraser Health, Dhillon has created spaces where seniors can prioritize physical

and mental well-being.

“Our classes go beyond exercise,” Dhillon explains. “They combat social isolation, create healing spaces, and strengthen community ties. By integrating South Asian music, traditional foods, and cultural celebrations, these sessions foster not only physical movement but also a sense of belonging.”

Dhillon’s dedication to elder care extends beyond Canada. Recognizing healthcare disparities in rural Punjab, he initiated

health clinics offering free medical checkups and essential medications to nearly 300 low-income families.

Dhillon also leads health awareness camps at Surrey’s annual Vaisakhi Parade, focusing on issues like menstrual health, breast cancer, and endometriosis. “These conversations are crucial in challenging cultural taboos and empowering women to take charge of their health without stigma,” he asserts.

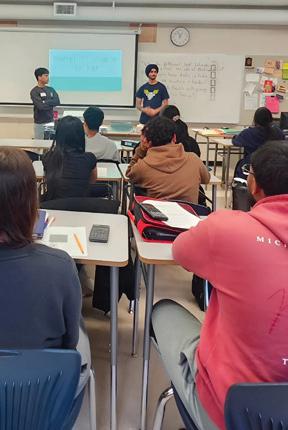

understands the challenges South Asian youth face adapting to Canadian society. Financial hardships, academic pressure, and cultural identity conflicts can overwhelm them. To help, he co-founded the Ignited Resilience Mentorship Foundation, connecting at-risk students with university mentors who provide academic guidance and emotional support.

“Representation matters. Many immigrant youth don’t see role models who look like them in leadership or academia. That’s what we aim to change,” Dhillon explains. His program offers mentorship that fosters trust, guiding students toward top-tier university admissions and away from harmful influences.

ML Emporio Wishes You And Your Family

A Happy Vaisakhi!

Grand Opening Incentives up to $40,000 off and more!

Despite his numerous leadership roles, Dhillon remains rooted in his South Asian heritage. “For me, leadership isn’t about titles—it’s about listening, serving, and creating spaces where others can thrive,” he reflects. Dhillon is unafraid to challenge outdated

norms, particularly regarding gender roles in health and wellness. Through his research, he identified cultural barriers preventing South Asian women from engaging in physical activity. In response, he launched women-only fitness classes, creating safe and culturally sensitive spaces where health is prioritized without judgment.

“My work is

about blending the wisdom of tradition with the innovation of youth,” he says. “Intergenerational connection is key to meaningful change.”

Despite being named to Surrey’s Top 25 Under 25 and receiving the BC Excellence Award, Dhillon has faced discrimination. “As a turbaned Sikh man, I’ve been underestimated, even mocked,” he admits. “But I’ve used these experiences as fuel to push forward and show that we belong in leadership spaces.”

Coming from a low-income household where both of his parents don’t speak English, Dhillon was the first in his family to attend university. Along the way, he faced financial hardship, racial discrimination, and moments of doubt. “I want you to know this: your story is powerful. Your background doesn’t limit you—it makes you resilient, resourceful, and real,” he asserts.

Hargun Dhillon’s work goes far beyond the communities he directly serves. Through elder wellness programs, youth mentorship, and breaking barriers in public health, his efforts are a beacon of hope, proving that true leadership lies in service and the courage to challenge the status quo.

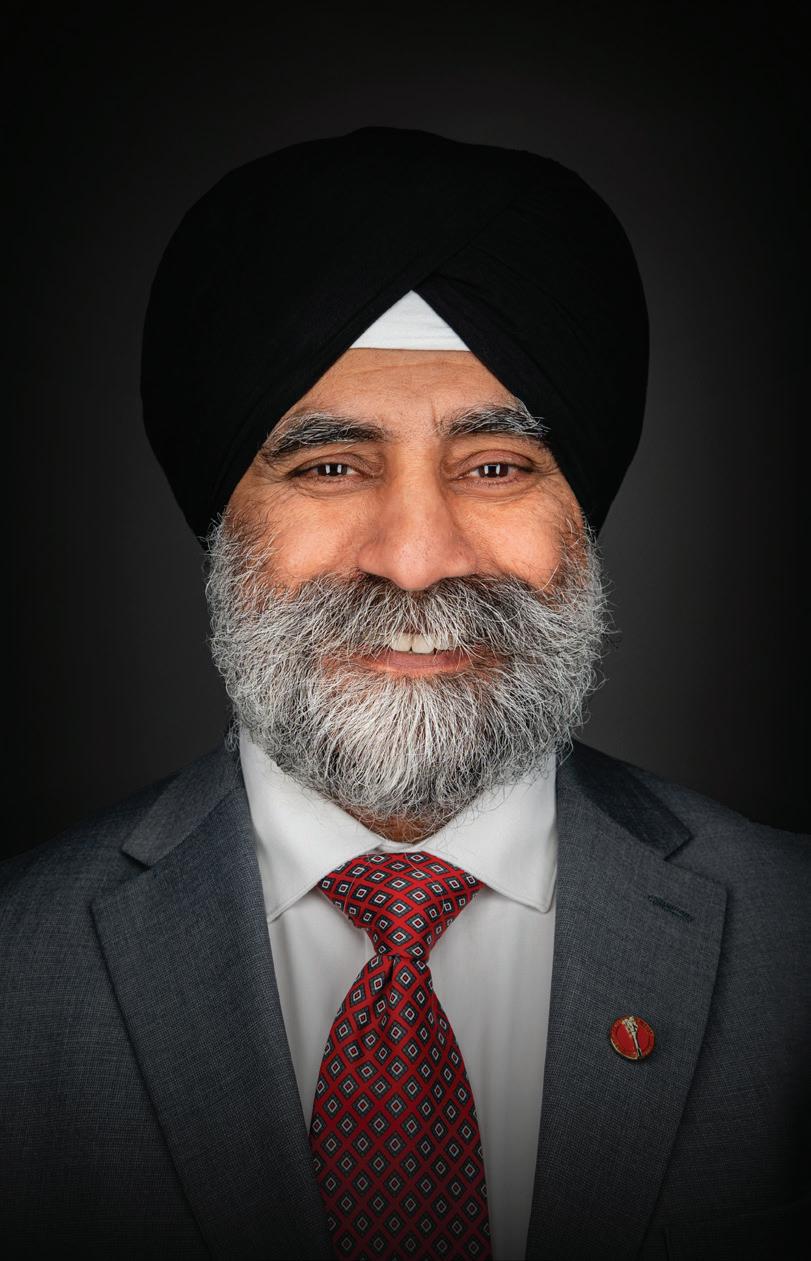

Some look up at the sky and see distance, but Hasandeep Singh Khural saw possibility. His journey from a sky-gazing child to cockpit commander is one of soaring ambition, quiet resilience, and groundbreaking achievement. As the first turbaned and bearded Sikh pilot with Air Canada, Khural’s path marks not only a personal triumph but also a meaningful milestone in the broader conversation about inclusion and representation in Canada’s aviation industry.

Khural’s fascination with flying began as a child, gazing up at airplanes in the sky with awe. “Aviation was always on my radar, even from a young age. I’ve been fascinated by flight since the first time I flew as a child. I was that kid who would always look

By Naina Grewal

up at the sky, watching airplanes with wonder,” he recalls. Though his dream was ignited early, it was in secondary school that the idea of becoming a pilot took hold as a real and achievable goal. He details, “Aviation is more than just flying. It’s about becoming a professional and connecting people, cultures, and ideas across the globe. As I learned more about the opportunities within the aviation industry, my interest only grew. I saw becoming a pilot as a chance to fulfill a lifelong dream of flying and seeing the world.”

The passionate pilot’s path wasn’t without its challenges. One of the most significant challenges Khural faced wasn’t academic or technical but cultural and institutional. A notable barrier loomed over Khural and other observant

Sikhs: aviation policy at the time prohibited beards, citing concerns about oxygen mask safety. “When I began my aviation journey as a student pilot in 2012, I wasn’t aware of these rules. Although there were times when I felt out of place or discouraged, I drew strength from my community, family, and faith. My journey to becoming a pilot has been driven by persistence, passion, and a strong commitment to achieving my goals,” he reveals.

That quiet strength and resilience paid off. In 2019, Air Canada commissioned a groundbreaking study through Simon Fraser University that tested oxygen masks on various beard lengths. The findings led to a historic policy change, first within Air Canada and

later influencing aviation standards nationwide. The change opened the doors wider—not just for Khural, but for future generations of observant Sikhs and others whose religious practices had previously been excluded by the industry’s safety protocols.

“Becoming the first turbaned and bearded Sikh pilot with Air Canada is both a tremendous honor and a responsibility I deeply respect,” Khural shares. “I strive to uphold the highest standards of professionalism, knowing that when I’m in the cockpit, I’m representing my community as a whole.” Rooted in Sikh values, Khural brings a grounded yet visionary approach to his work. He highlights, “My Sikh identity has played a huge role in shaping the way I approach my career. Sikhism teaches values such as humility, service to others, and maintaining a strong sense of integrity—values that are critical to aviation, especially as a leader. I believe in treating every individual with respect and in fostering a culture of inclusion and kindness within the workplace.”

That inclusive spirit has been matched by the warm reception he’s received from those around him. “The reaction has been overwhelmingly positive,” he emphasizes. “My family is incredibly proud, and their support has been unwavering throughout my journey. They’ve always encouraged me to follow my dreams, no matter how difficult or unconventional. The Sikh community, in particular, has shown im-

mense pride as well. As for my colleagues at Air Canada, I’ve received nothing but support and encouragement. It’s heartening to be surrounded by people who are not only accepting but also excited to see diversity represented at the highest levels of aviation.”

While breaking barriers is significant, Khural is just as committed to lifting others. One of the most meaningful aspects

of his career has been mentoring young people. This includes especially those from underrepresented backgrounds who dream of becoming pilots but might see the path as inaccessible. “The most rewarding experience in my aviation career has been the chance to mentor others who may have thought aviation was beyond their reach. Whether it’s through speaking engagements or teaching students who share my passion for flying, being able to inspire and create opportunities for others has been an incredibly fulfilling aspect of my journey,” he says.

To those interested in the field of aviation, Khural advises focusing on developing the right competencies and surrounding oneself with supportive individuals, whether it’s family, mentors, or communities. He encourages fostering connections and never shying away from reaching out for guidance. Khural’s message to the next generation of dreamers is clear and uplifting: “The sky is not the limit—it’s just the beginning.”

Meet Beant, a rising rap artist and curator from Leamington Spa, who is making waves in the UK music scene with his unique fusion of British rap and Punjabi folk music. Known for his standout tracks like ‘Brown Geezas’ and ‘Way Too Much,’ Beant seamlessly merges the raw energy of British rap with the soulful essence of Punjabi culture, staying unapologetically British while epitomizing his ‘desi’ core. His journey began in his teenage years, when he would write rap lyrics, spitting bars in classrooms, laying the foundation for his musical career. In 2023, Beant released his debut EP, ‘The Rules Of Engagement’, pushing creative boundaries and establishing himself as a fresh, authentic voice among the internet-smitten generation, all while staying deeply connected to his roots.

By Natasha D’souza

Beant’s love for music traces back to the Gurdwara, where he first encountered Kirtan and learned Dilruba. “I never practiced enough to get any good!” he laughs, but it was there that his passion for music truly ignited. His path into the world of digital content creation came later when he began documenting his experience teaching English to children in Italy on TikTok. It was during this phase that the 25-year-old emerging star ventured into Punjabi and Sikh-related content, starting with a video breakdown of Sidhu Moose Wala’s YSL. “I enjoyed making that video so much, I started creating more content,” he shares, and the community began to grow.

In 2023, Beant founded ‘Lishkara,’ an event series dedicated to authentic Punjabi folk music. “The idea germinated from one of my elders who urged

me to bring my internet audience into a physical space,” he explains. Since its inception, it has become a platform for showcasing talented Punjabi folk musicians like Preet, Dhami Amarjit, and Jet Karra, creating a stomping ground for younger audiences to connect with the roots of Punjabi music.

Blending his British upbringing with his Punjabi roots is at the heart of Beant’s artistry. Collaborating with producers and friends, he strives to create a sound that captures his British-Punjabi identity, “I’m inspired by artists like Skepta and Nines as much as I am by Manak and Bindrakhia,” he says.

Looking back at his highs and lows, Beant recalls the electric energy of performing live at JAWANI 4EVA, where freestyle rapping and audience interaction were highlights. “There’s something freeing

about engaging the crowd in the moment,” he shares. As a curator, one of his proudest moments was watching Preet perform at the first ‘Lishkara’ event. “Her vocals were unmatched, and the audience was so connected with the performance.”

He further elaborates, “Art is a huge part of culture, and creating new art that draws upon existing culture is a way to preserve and build it. We aim to bridge the gap between tradition and innovation, providing an authentic space for Punjabi folk music while introducing it to fresh, younger audiences.”

With a keen eye on the future, Beant is excited about the resurgence of the Punjabi underground scene in the UK. “The diaspora is keen to learn about legends like Manak and Chamkila. These artists have so much to offer,” he says, reflecting on the potential for Punjabi music to reach new heights. He’s also excited to see more Punjabi sounds entering global platforms like Amapiano and Red Bull Culture Clash, marking a new era.

Beant’s music fuses the past and the future, so get ready for a new wave of sound that’s as raw as it is real, with the power of culture glinting in every verse.

By Naina Grewal

Some heroes don’t wear capes—some wear uniforms, quietly serve their communities, and act when it matters most. Gurmehar Pabla, a high school student from Panorama Ridge Secondary and an active Air Cadet with 278 Cormorant Royal Canadian Air Cadet Squadron in Surrey, em-

bodies that quiet heroism. On June 6, 2024, during a school trip, Pabla prevented a potential drowning, yielding a moment that would later earn him official recognition from the City of Surrey and applause from Mayor Brenda Locke during a February 2025 council meeting.

“In that moment of crisis, Gurmehar acted selflessly,” Mayor Locke said, acknowledging not only his quick thinking but also the composure and sense of responsibility he demonstrated under pressure. While the community has rightfully celebrated Pabla’s bravery, he himself sees the moment with humble simplicity. “It was a time when someone was in need. I didn’t think much of it,” he recalls. “The situation was potentially dangerous. He was struggling and not comfortable. I knew I was a bit more proficient and sustainable in the water, so I stepped in.”

Despite the media attention that followed, Pabla didn’t initially consider the moment to be a big deal. “At first, I thought it was pretty small,” he says. “I

didn’t think it’d be that big, but it was covered by the media and many people posted it. It was a pretty big shock. I’m thankful for the recognition and it’s nice to share the story with the community.”

That sense of calm and perspective didn’t come from nowhere. Pabla credits his time in the Canadian Cadet Program for instilling the life skills that helped guide his actions that day. He’s been involved in the cadet movement

since the age of nine, starting with the Navy League before transitioning to Air Cadets. “Cadets build self-integrity and leadership. These things become a big part of your life—you don’t even realize it at the time. It’s built my character.”

Captain Amar Tiwana, Commanding Officer of 278 RCACS, wasn’t surprised when he heard about Pabla’s heroic actions. “I was really happy! I thought to myself, here’s someone putting their skill to good use,” he says. Amar sees Pabla’s act not just as an individual success, but as part of a broader story. “It’s amazing to see kids from our community stepping up. When youth like Gurmehar succeed, the whole community benefits.”

It’s amazing to see kids from our community stepping up.

When youth like Gurmehar succeed, the whole benefits.community

Capt. Amar Tiwana Commanding Officer, 278 RCACS

Surely, Pabla’s approach to the situation was methodical. He stresses the importance of assessing risk before jumping in. Pabla notes, “Many people say think about others first, but it’s important to also think about yourself. Assess where you are and how you can help. The first step is always to evaluate the situation. Call 911 first and then help. If

you’re in danger yourself, it’s best to make sure to call for help and then proceed.”

That level-headedness is rare in someone so young, but not surprising for anyone who’s watched Gurmehar Pabla grow within the Canadian Cadet Program. In fact, he’s already been part of high-profile national events. He participated in both the opening and closing ceremonies of the Invictus Games 2025. Pabla has also attended the Basic Aviation and Air Rifle Marksmanship Instructor Course at Cadet Training Centers and is a qualified Cadet Correspondent. These experiences speak to the confidence and sense of community that continues to guide him.

Tiwana, who was a cadet himself, has witnessed firsthand the impact of the Canadian Cadet Program and sees mentorship as a lifelong mission. “My focus is giv-

ing back,” he says. “What’s the point of success in our personal lives if you can’t use it to uplift others? He beams with pride when speaking about his cadet and highlights that the Canadian Cadet Program provides opportunities for youth to gain valuable skills that build confidence and help pave the way in transition to adulthood.

Cadets engage in varied and unique experiences while developing competencies in leadership, citizenship, and physical and mental fitness. He details that the program strives to offer youth a safe, welcoming, and supportive program environment where all feel respected, valued, included, and able to achieve their full potential.

As for Pabla, his aspirations are grounded. He’s set his sights on a career in business, with plans to study accounting and finance. Undoubtedly, no matter where he goes,

the lessons of leadership, community service, and humility will continue to be a beacon of light for him. Formative moments have shaped not just his leadership skills, but also his deep sense of service to others, which is a quality that shines through in everything he does.

Pabla’s story of quiet bravery isn’t just about saving a life, but also about the power of courage, character, and community. It’s a reminder that heroism doesn’t always arrive with fanfare; sometimes, it’s found in the steady resolve of those who act selflessly when no one expects it. Such actions remind us that leadership can come quietly, and often, from those who simply choose to do the right thing. For Gurmehar Pabla, the deed may have felt small, but its impact will resonate far beyond that one day!

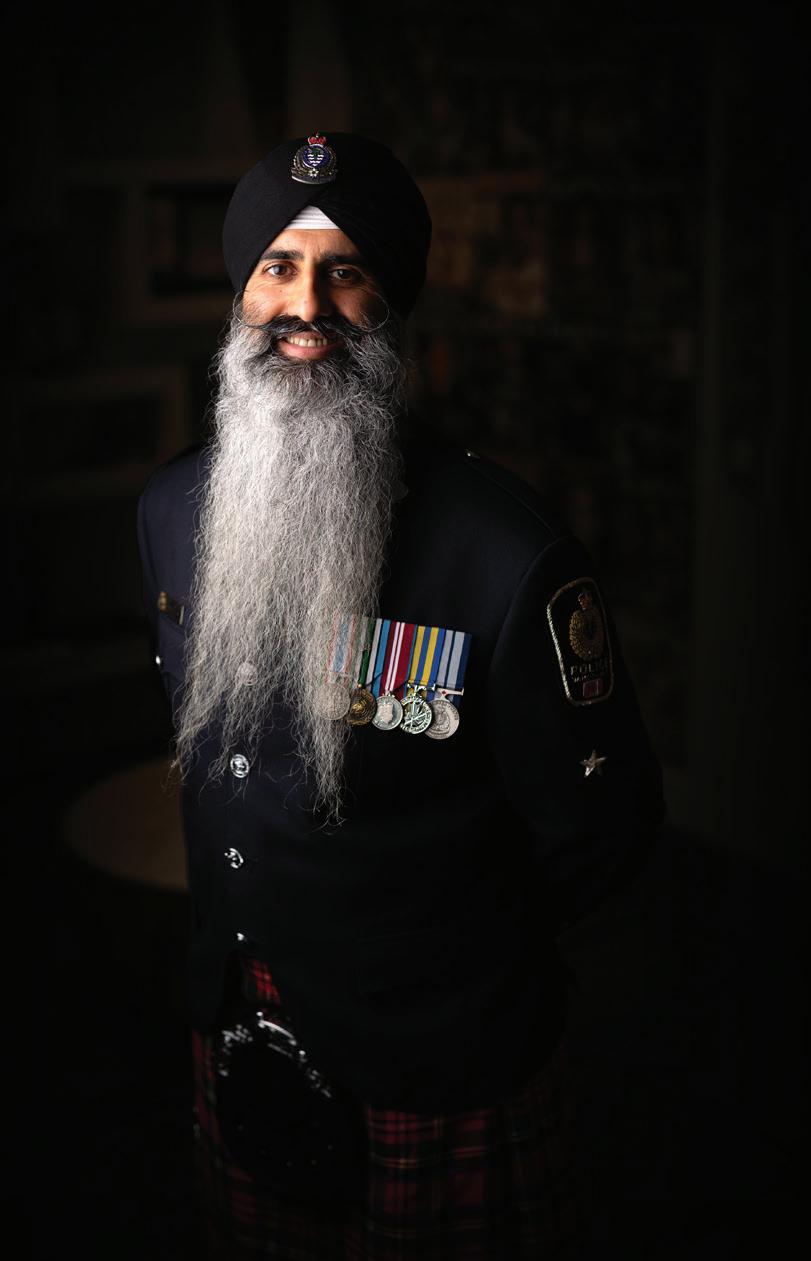

Traffic Enforcement Officer Sukhvinder Sunger has dedicated his career to serving and protecting the residents of Vancouver as a proud member of the Vancouver Police Department (VPD). With his many years of experience in law enforcement, he has made incredible contributions to the community, not just through his work as a police officer but also through his deep involvement with the Vancouver Police Pipe Band - the world’s oldest, continuously serving, non-military pipe band.

By Ancy Mendonza

Raised in Victoria, it was only natural for Constable Sunger to begin his journey in law enforcement with the Victoria Police Department as a reserve constable. His teenage dream of becoming a police officer was finally realized after he joined the VPD in 2002. As a member of the VPD for the past 23 years, he works tirelessly to uphold justice and ensure the safety of Vancouver’s diverse population. With a diploma in criminal justice, he goes above and beyond enforcing the law—he is trusted in the community and actively engages with citizens to build stronger relationships between law enforcement and the public.

Over the years, Constable Sunger has been in various roles within the department—most notably his appointment as a United Nations Peacekeeper in South Sudan: “It was a life-changing experience, and I’m never going to be the same anymore. But the Shabads I carried on a

USB drive really helped me during the time.”

Beyond his responsibilities as a police officer, Constable Sunger is a drummer with the Vancouver Police Pipe Band. The band, known for its rich Highland tradition and deep-rooted connection to both the police force and the community, is a prestigious musical group that represents the VPD at events locally and internationally.

Constable Sunger, the first person of

color to join the band since its inception in 1914, has performed in Switzerland, Belgium, France, and most notably in India, where the band visited Amritsar, Nawanshahar, and Chandigarh to commemorate 100 years of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. As a South Asian member of the band, he helps bring greater cultural diversity to the group while inspiring others from the community to accept opportunities in different fields. He particularly takes pride in representing his heritage through the music he plays.

Constable Sunger’s journey is an inspiration for many, particularly within the South Asian community. His message to young South Asians is one of perseverance and confidence. He encourages individuals to step outside of their comfort zones, pursue their dreams with dedication, and never shy away from new opportunities.

Through his work with the Vancouver Police Department and his involvement in the Vancouver Police Pipe Band, Constable Sukhvinder Sunger continues to embody dedication, passion, and cultural pride, proving that service to the community extends far beyond the badge.

By Naina Grewal

Every April, communities across Canada unite to raise awareness about the life-saving impact of organ and tissue donation, with National Organ and Tissue Donation Awareness Month at its core. It’s a time to spark vital conversations with loved ones about the

lasting impact of donation. Fittingly, April also marks Sikh Heritage Month, offering a timely opportunity to explore the cultural and spiritual connections between Sikh values and the act of giving life.

Dr. Reetinder Kaur, project director at the University of British Co-

lumbia’s Kidney Transplant Research Program and Punjabi language instructor at Simon Fraser University, leads organ donation advocacy efforts and has spent over five years working closely with transplant patients, donors, and families. As a newcomer to Canada in 2020, Dr. Kaur immedi-

J o i n H i - C l a s s J e w e l l e r s

f o r V a i s a k h i o n

A p r i l 1 2 , 2 0 2 5 i n

V a n c o u v e r ' s P u n j a b i M a r k e t

f o r t h e a n n u a l N a g a r K i r t a n

ately noticed a critical gap. “What struck me most was that the storytelling around organ donation and kidney transplantation lacked representation from the South Asian community, specifically the Punjabi-speaking Sikh community,” she shares.

Dr. Kaur’s fluency in Punjabi, combined with her understanding of cultural and religious nuances, positioned her to fill this gap. Through community engagement and research, she’s helped give voice to stories that often go unheard. One such initiative is her powerful multilingual photo exhibit,

Surviving and Thriving, which highlights stories of Punjabi living kidney donors and transplant recipients.

Among the stories featured in the exhibit are that of Randeep Singh and Mantej Dhillon. Randeep, diagnosed with kidney failure, made a public plea for a living donor on Punjabi radio. A complete stranger, Mantej, heard his story, got tested, and turned out to be a match. His selfless act not only saved a life but inspired an entire community. “Their story is the embodiment of seva,” says Dr. Kaur, refer-

,, ,, At Virk Law Group, we treat you and your legal matter with professionalism confidentiality and respect.

• Divorce

• Nullity / Annulment

• Cohabitation / Separation Agreement

• Pension Division

• Claims Against In-laws

• Child / Spousal Support

• Guardianship / Contact Orders / Custody / Parenting Time

• Asset / Property Division

• Child Apprehension by MCFD

Criminal Law

• Assault

• Uttering Threats

• Theft

• Peace Bond (Recognizance)

Estate/Civil

• Wills Variation Cases

• Trustee & Executor Disputes

• Claims by Beneficiaries

• Wills Disputes

• Dog Bite Cases

• Slip & Fall Cases

• Debt Collections

ring to the Sikh principle of selfless service.

For many, like Gurjit Pawar, a Registered Nurse who works with patients living with kidney disease and is herself a twotime kidney transplant recipient, the journey is long, personal, and emotionally layered. Diagnosed with kidney disease at just 13 years old, Pawar’s life trajectory changed overnight. “I remember sitting at home with my family when the pediatrician called. My mom answered the call and looked at me with fear in

her eyes. That phone call changed everything,” she recalls.

Over the years, Pawar endured various treatments, including dialysis. Her diagnosis not only altered the course of her own life but also deeply impacted her mother, who was soon diagnosed with depression, leading to a profound shift in their family dynamics. Pawar details, “This was our first exposure to chronic illness in our family. I don’t think that any of us were given the tools to navigate through it.”

Her first transplant came through a paired exchange program, which is a network that allows incompatible donor-recipient pairs to swap matches with others. Her then-boyfriend, now husband, donated his kidney to a stranger so she could receive one in return.

“He stole my heart, and I stole his kidney,” Pawar jokes. Today, they have two sons, the second born via surrogacy due to changes in her health. Pawar’s second transplant came years later,

after battling COVID-19 and seeing her kidney function decline. This time, it was a friend—a former colleague—who stepped forward. Pawar expresses, “It’s a hard gift to accept and can be overwhelming to think that this level of kindness exists, but I will forever be grateful to my donors and the community of people that have supported me through this journey.”

From her position in healthcare, Pawar regularly sees the cultural and emotional barriers that persist in the South Asian community. “Organ donation is rarely discussed. We don’t talk about death,” she says. “For those needing a transplant, there’s often guilt, shame, and fear of judgment. It’s not that our culture is negative, but that many people shield themselves from asking for help, or simply don’t have

the tools to do so.”

Dr. Kaur echoes the sentiment, adding that women face added cultural pressures. “Some families worry that donating a kidney will affect a woman’s marriage prospects or ability to have children. These concerns add complexity,” she explains. Both stress the importance of education, open conversation, and language-accessible resources. For those unsure where to begin, Dr. Kaur suggests starting with BC Transplant’s website to learn about donation types, eligibility, and the family’s role in consent.

BC Transplant emphasizes that organ donation is the ultimate act of selflessness and generosity. As per BC Transplant, “Living donors who choose to undergo surgery to save someone’s life, and the deceased donors and their families who make this

selfless decision during their grief, are profoundly inspiring. We know that 90 percent of British Columbians support organ donation, yet fewer than one in three have registered their decision on deceased donation.”

Undoubtedly, sharing stories is key to breaking the stigma and inspiring action. “If you’re considering donating, talk to someone with lived experience. That had the biggest impact on me,” says Pawar. “I get to live a full life, give back, and raise two beautiful kids. That’s the gift of organ donation.”

As April reminds us, giving life is one of the most powerful acts of humanity. In the Sikh community and beyond, it’s a time to reflect, register, and start conversations—because sometimes, a simple dialogue can give someone else a future!

■ PERSONAL INJURY / ICBC CLAIMS

■ RESIDENTIAL / COMMERCIAL REALESTATE

■ CORPORATE / COMMERCIAL LAW

■ TRUST & SHAREHOLDER'S AGREEMENTS

■ BUYING / SELLING BUSINESSES

■ PROPERTY SUB-DIVISIONS

■ WILLS & ESTATES

■ CONTRACT DISPUTES

■ COMMERCIAL LITIGATION

■ BUILDER'S LIENS

■ COLLECTIONS

■ GENERAL LITIGATION

■ FAMILY LAW

By Ancy Mendonza

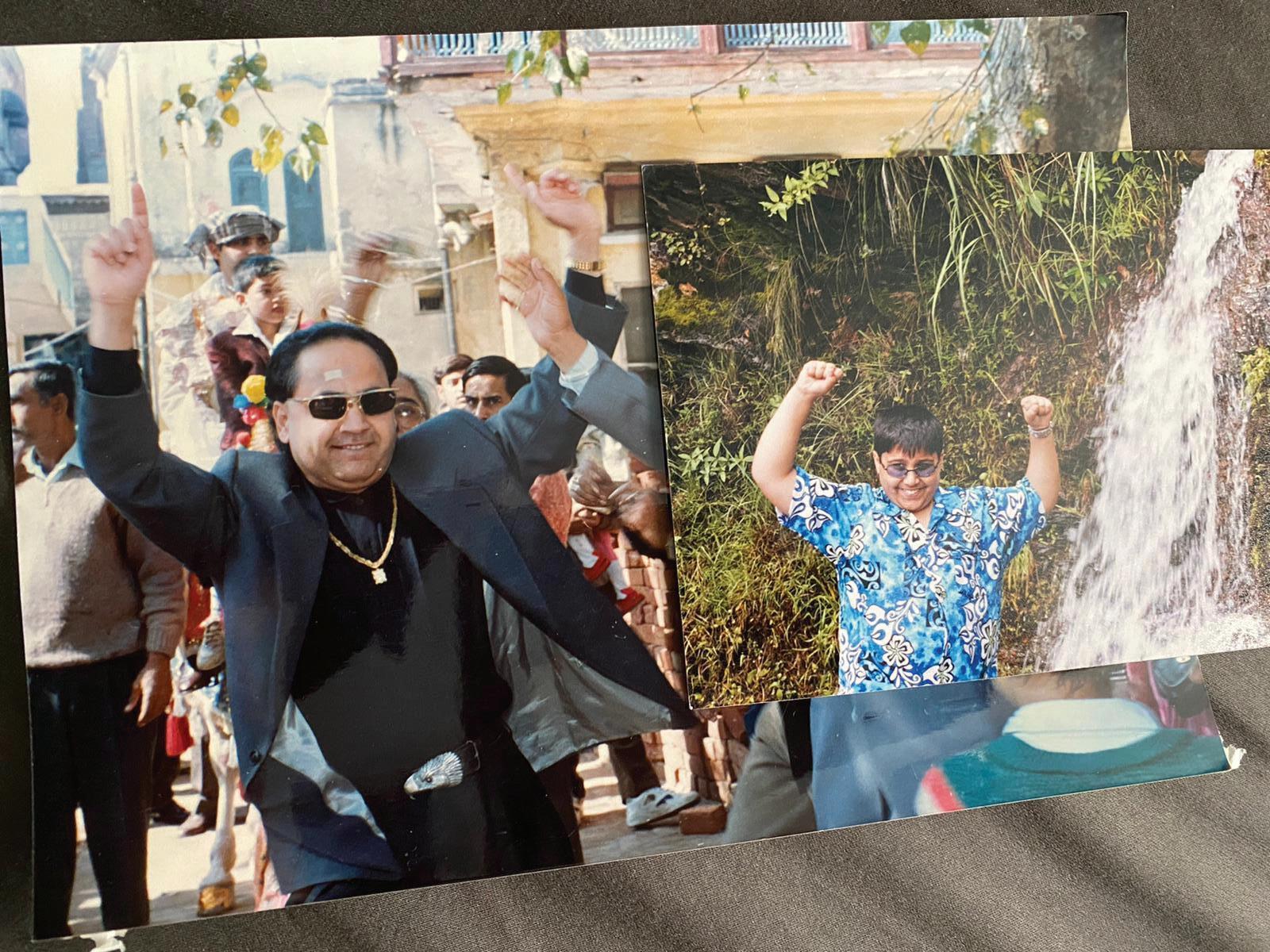

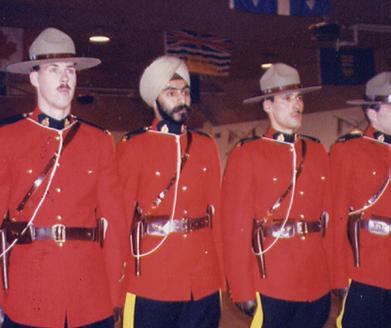

In the heart of Canada’s rich multicultural landscape is a man whose journey has not only broken barriers but has also inspired generations of Sikhs across the country.

Baltej Singh Dhillon’s story is one of resilience, conviction, and an indomitable spirit to uphold his identity and principles. From being the first turbaned officer in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) to his recent appointment to the Senate, his path has been anything but ordinary. As Vaisakhi approaches, a time of renewal and reflection for Sikhs worldwide, there is no better moment to celebrate this trailblazer who has paved the way for inclusivity while staying true to his roots.

In 1983, Dhillon immigrated to Canada from Malaysia, carrying with him the aspirations of his family and the teachings of his faith. Like every new immigrant, he faced the daunting challenge of building a life in a new land: “We came here with very little and had to work to make ends meet. I picked berries and went to school at the same time, and I’m certainly thankful for the experience as it prepared me for what was to come next.”

Policing was never his first career choice: “I always wanted to be a lawyer. I had no desire to become a police officer, partly because I didn’t see

anyone who looked like me in the police force.” It was during his degree in criminology that he started to volunteer with the RCMP as an interpreter to communicate with recent Asian immigrants. The encouragement and advice from RCMP police officers led him to switch careers and formally apply to the police service in 1988.

Though he met every requirement to join the police force, the uniform code posed a major challenge–the RCMP dress code at the time forbade beards and turbans and demanded officers to be clean-shaven and wear the standard Stetson hat on duty. This meant that for Dhillon to join the force, he would have to compromise his identity and Sikh faith. But he was not one

to choose between his faith and his calling. Instead, he chose to challenge the norm.

What followed was a landmark battle that shook the foundations of the RCMP’s traditions. Dhillon petitioned for the right to wear his turban as part of his uniform, igniting a national conversation about religious freedom and cultural inclusivity. His fight was met with resistance, both from within the force and from segments of the public who believed that altering the uniform’s dress code was a threat to Canadian tradition: “I saw police officers in Malaysia, in the UK, serving perfectly well with their Dastaar, so I knew that the turban was not an issue. I was simply standing up for my rights as a Canadian.”

Over 90,000 Canadians signed petitions against the turban in the RCMP. There were anti-turban pins, calendars, road signs, and editorials mocking the campaign. Yet, his perseverance, coupled

with support from the Sikh community and human rights advocates, led to a historic decision: In March 1990, the Brian Mulroney government officially allowed Sikhs to wear turbans and keep their beards while serving in the RCMP.

The victory was more than just personal; it was a triumph for the Sikh community and every other community who believed in the fundamental right to religious expression. For Dhillon, this was just the beginning—he trained in Regina and graduated to active duty in 1991. In his 30-year-long career since then, he played a vital role in many high-profile cases,

including the Air India bombing and the Robert Pickton case. His main focus throughout his time remained battling gang violence and curbing the toxic drug supply in the country.

Beyond his professional contributions, Dhillon became a symbol of what it meant to embrace one’s heritage while serving a broader cause. His presence in the RCMP inspired young Sikh Canadians to consider careers in policing, knowing that they too could wear their articles of faith with pride. His journey dispelled myths, challenged stereotypes, and reinforced the idea that being Canadian does not mean shedding one’s cultural identity—it means enriching the national fabric with diverse threads.

While Dhillon’s name was already etched in Canadian history as the first turbaned RCMP officer, his recent appointment as a Senator reaffirmed his standing as a leader and changemaker. On February 7 this year, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced his appointment to the Senate of Canada, a role that allows him to shape policy and defend issues close to his heart: “I’m so thankful for this privilege to be able to serve and represent British Columbia. My primary focus as a Senator would be to create pathways that enhance policing and advocate for diversity and inclusion.”

His journey from a young immigrant to a national figure of influence is a testament to the Sikh principle of seva—selfless service. Through his work, he remains committed to creating opportunities for

underrepresented communities and ensuring that the sacrifices he made in his early years pave the way for a more inclusive future.

Despite his many accolades, Dhillon remains grounded in the principles that have guided him since childhood. Beyond his professional achievements, he is a devoted family man, deeply connected to his faith and personal well-being. Each morning, he dedicates the first hour of his day to meditation and prayer, a practice that keeps him centered amidst the demands of public service: “I haven’t missed a day, I will never miss a day. That’s what keeps my demons at bay.”

These days, Dhillon finds immense joy in his role as a grandfather. His grandson, Jovin, is the heart of his world, keeping him busy with laughter, mischief, and the boundless

energy of childhood. For someone who has spent decades in high-stakes environments, his time with Jovin offers a different kind of fulfillment—one rooted in love, legacy, and the passing down of values that have defined his life.

As the Sikh community prepares to celebrate Vaisakhi, Dhillon’s journey serves as a poignant reminder of the essence of this occasion. Vaisakhi is not just about festivity; it is about reaffirming one’s commitment to principles, standing firm in the face of challenges, and serving humanity with unwavering devotion. In many ways, Dhillon’s life embodies the very spirit of Vaisakhi—a relentless pursuit of justice, identity, and community upliftment.

Baltej Dhillon’s name will forever be synonymous with breaking barriers. But more than that, it will be remembered as a name that brought people together, challenged the status quo, and proved that faith and service can go hand in hand. As Vaisakhi dawns upon us, we celebrate not just the festival, but the spirit of individuals like Dhillon— who, through their unwavering conviction, continue to inspire generations to come.

By Ekamjot Singh Deol

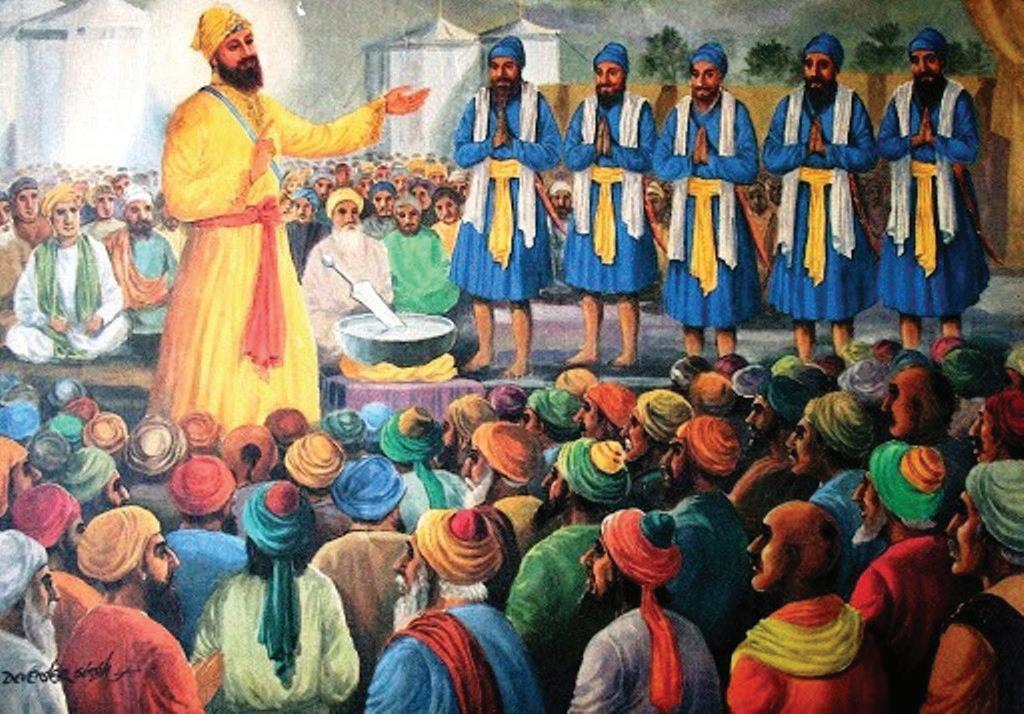

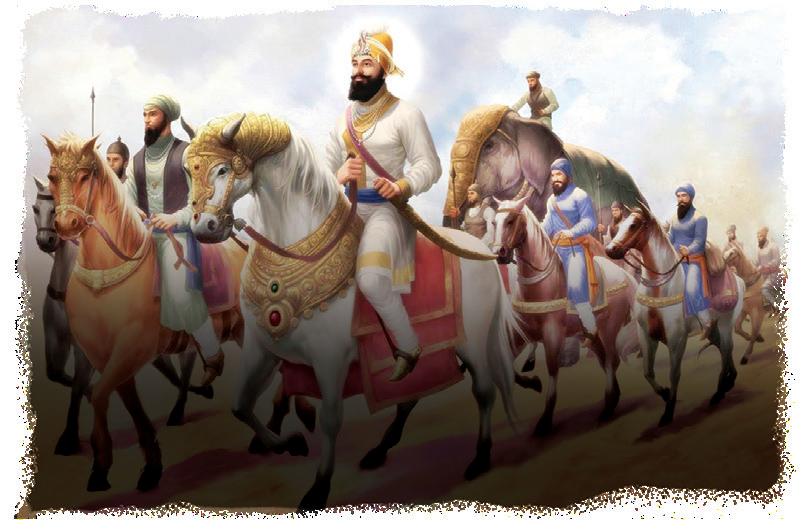

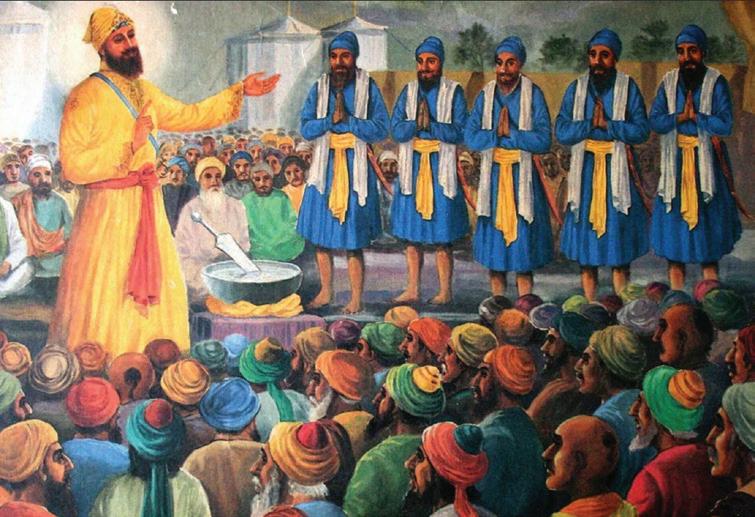

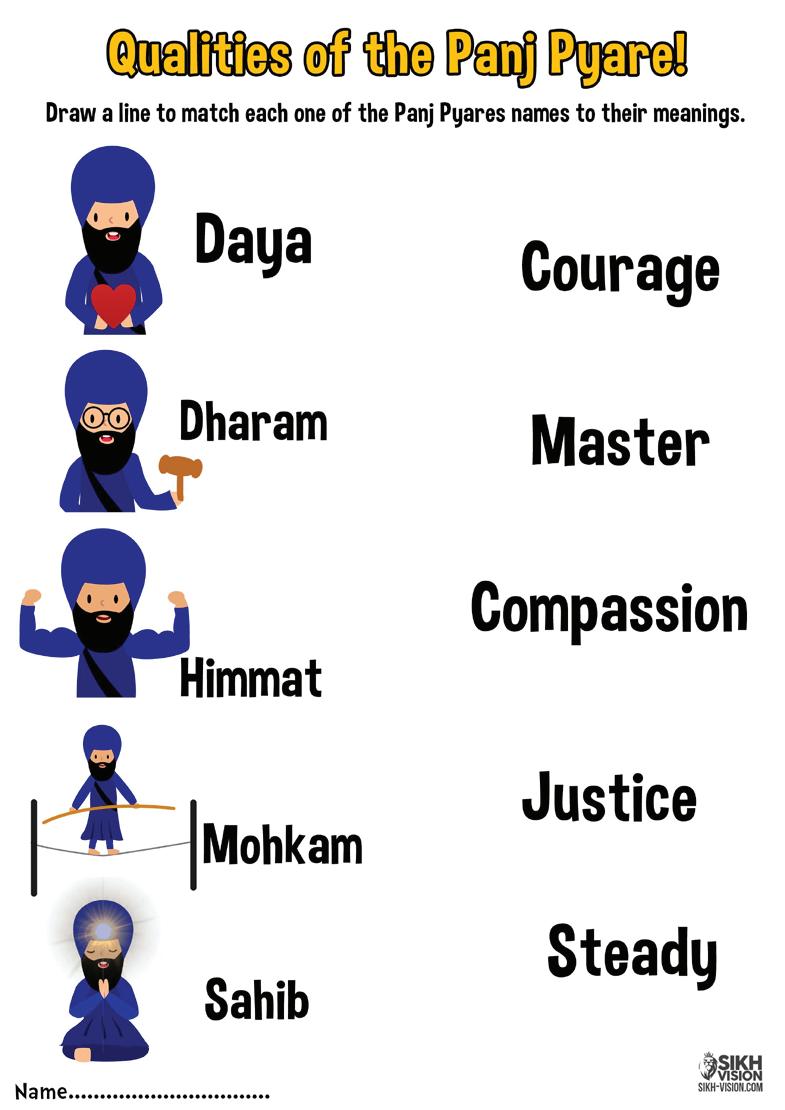

On the day of Vaisakhi, 1699 at Anandpur Sahib, a sea of Sikhs watched as Guru Gobind Singh Ji, made a demand testing their commitment by asking for a head. One devotee, named Daya

Ram, stepped forward and offered his life. This demand was repeated four more times, leading to four more souls—Dharam Das, Mohkam Chand, Himmat Rai, and Sahib Chand, offering themselves. From the shadows, they emerged,

reborn, dressed in the same attire as Guru Sahib, and presented to the congregation as the Panj Pyaare—the five beloved ones. Guru Sahib then initiated the Amritpaan ceremony. Amrit was prepared in an iron bowl, filled with wa-

ter and patasse (sugar crystals), and stirred with the khanda (the double-edged sword) while Gurbaani was being recited. Firstly, Amrit was administered from Guru Sahib to the Panj Pyaare, then, astoundingly, from the Panj Pyaare to Guru Sahib himself. In a revolutionary step, their last names, the indicators of caste and division, were scrapped and replaced with “Singh” and “Kaur.” Thus, the Khalsa, a casteless community of Amritdhari Gursikhs, was born.

The option of taking Amrit was then opened to the entire congregation. Thousands embraced Amrit, joining this new order. Guru Gobind Singh Ji, by taking Amrit from the Panj Pyaare, enshrined their

Media Coordinator, Sikh Heritage BC

Ekamjot Singh Deol is a third-year law student at the Allard School of Law at UBC, and holds an undergraduate degree in Criminology from Simon Fraser University. He is a media coordinator with Sikh Heritage BC. Sikh Heritage BC is a passionate, volunteer-driven, not-for-profit organization committed to preserving and celebrating Sikh culture, heritage, and history in British Columbia. Their mission is to shine a spotlight on the rich tapestry of Sikh heritage, fostering positive change within the Sikh community and beyond. Ekamjot’s passion for preserving and highlighting his culture drives his work with Sikh Heritage BC.

ultimate highest authority in the Panth going forward. He practically depicted the concept of “Aape Gur Chela”—i.e., the Leader of the Panth is also a disciple of the Panth. This ultimate authority has been evidently exercised at crucial junctures in history. For instance, during the battle of Chamkaur, despite his initial resistance to the suggestion of leaving the fortress, Guru Sahib bowed to the Panj Pyaare’s command, leaving the fortress to continue Khalsa’s fight against tyranny. The Panj Pyaare, therefore, came to signify the embodiment of the Panth’s collective will, as depicted by their commands, which are binding on the entire Panth, includ-

ing the Guru himself. Today, the legacy lives on. Five Amritdhari Sikhs, bound by the Khalsa Rehat Maryada (Khalsa’s way of life), come together to form the Panj Pyaare. The authority conferred upon the Panj Pyaare is exercised at the highest level in taking major Panthic decisions that impact the whole Khalsa Panth as well as in everyday matters such as leading Nagar Kirtans, administering Amritpaan

ceremonies and conducting disciplinary hearings of those that have strayed from the Amritdhari Path.

Therefore, the Panj Pyaare perform a dual role: they guide the Khalsa Panth and embody its collective voice. Their ultimate goal is to ensure that members of the Panth live in adherence to the Gurmat Rehat Maryada and achieve Anand (a state of true and eternal bliss) in doing so. This year, Sikh

Heritage BC’s celebration of Sikh Heritage Month is thematically centered on the concept of Anand. We encourage the Sangat to attend our events to experience, explore, and discuss the depths of the multi-faceted understanding of Anand in Sikhi while celebrating the contributions of Sikhs to the social, economic, and cultural fabric of British Columbia and Canada.

Dr. Joban Singh Bal is a UBC Family Medicine Resident Physician and the President and Founder of the One Blood For Life Foundation.

By Dr. Joban Singh Bal

Chardi Kala lives in all of us! It is a call to rise, serve, and live with joy, even through pain. In today’s world, nurturing this light isn’t just an aspirational virtue—it’s a responsibility we carry, both for ourselves and for future generations.

Rooted in Sikhi, Chardi Kala is often translated as eternal optimism or rising spirit, but it is more than just a feeling. It is a conscious choice to live joyfully with resilience and compassion, especially

in the face of adversity. It shapes how we show up in our lives, through seva, spirit, and a deep sense of responsibility. This principle has shaped my journey, from medicine to entrepreneurship to community service. No matter the setting, I see Chardi Kala as a foundational and powerful daily prescription we have been given to care for our mind, body, and soul. Principles rooted in Sikhi can inspire our wellness practices and align well with modern longevity science. These include waking up at amritvela (before dawn), serving others through seva (selfless service), and being tyaar bar tyaar (ever-ready) for whatever life may bring.

porating this into our lives, we must first look inward. Are we in the right frame of mind? Are we practicing mindfulness? Whether through meditation, jour naling, or quiet reflection, we must make space to reset the foundation of our mental resilience. Fortu nately, we do not have to do this alone. As social beings, we are strength ened by connection with our families, friends, and support networks - our sangat. In the world of medicine, more than ever before, social factors like this are being recognized as having dramatic impacts on long-term health outcomes and factor into the holistic well-being of a person.

■ MAJOR ICBC CLAIMS

General Civil Litigation

■ MAJOR ICBC CLAIMS

■ MEDICAL & DENTAL MALPRACTICE

General Civil Litigation

■ EMPLOYMENT DISPUTES

■ MEDICAL & DENTAL MALPRACTICE

■ MAJOR ICBC CLAIMS

■ MAJOR ICBC CLAIMS ■ MEDICAL & DENTAL MALPRACTICE

■ EMPLOYMENT DISPUTES

■ PRIVATE INSURANCE DISPUTES

■ MEDICAL & DENTAL MALPRACTICE

■ EMPLOYMENT DISPUTES

Civil Litigation

■ DEFAMATION

■ EMPLOYMENT DISPUTES

■ PRIVATE INSURANCE DISPUTES

■ PRIVATE INSURANCE DISPUTES

■ MAJOR ICBC CLAIMS

■ DEFAMATION

■ DEBT COLLECTION MATTERS RELATED DOCUMENTS

■ PREPARATION OF WILLS & RELATED DOCUMENTS ■ ESTATE LITIGATION & WILLS VARIATION CLAIMS

■ PREPARATION OF WILLS & RELATED DOCUMENTS

■ PREPARATION OF WILLS & RELATED DOCUMENTS

■ ESTATE LITIGATION

■ ESTATE LITIGATION & WILLS VARIATION CLAIMS

■ PREPARATION

■ DEFAMATION

■ PRIVATE INSURANCE DISPUTES

■ MEDICAL & DENTAL MALPRACTICE

■ DEFAMATION

■ DEBT COLLECTION MATTERS

■ DEBT COLLECTION MATTERS

■ EMPLOYMENT DISPUTES

■ DEBT COLLECTION MATTERS

■ PRIVATE INSURANCE DISPUTES

■ DEFAMATION

■ DEBT COLLECTION MATTERS

■

■ ESTATE LITIGATION & WILLS VARIATION CLAIMS ■ BUYING AND SELLING PROPERTY

AND SELLING PROPERTY

To live in Chardi Kala, we must also honor the body we have. Health is not just about living longer, but also living stronger - with energy, mobility, and clarity throughout our lives. Daily movement, a balanced diet with enough protein, strength training at least three times per week, and regular restful sleep form the foundation of lifelong vitality. Especially as we age, these habits improve bone density, brain function, and metabolism and reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression. Needless to say, when the physical body aches, it becomes much more difficult to embody Chardi Kala how we may want to!

At its core, for many, Chardi Kala is a spiritual state. It

is a steadiness that allows us to carry light in the midst of darkness. Perhaps no one embodied this more powerfully than Sri Guru Gobind Singh Ji. Despite immense personal loss, including the martyrdom of his four sons, he never surrendered his vision or spirit. He wrote the Zafarnama, a declaration of truth, resilience, and divine strength that continues to inspire generations. His life teaches us that Chardi Kala is not about avoiding pain. It is about rising above it through fearless love, selfless service, and a deep connection to the Divine. When we apply this spirit to our physical health, mental resilience, and spiritual practice, we can begin to embody Chardi Kala in our daily lives.

Throughout my work in medicine, entrepreneurship, and community service, there have been times when the path was difficult or unclear. There will be more, but Chardi Kala means continuing forward with purpose and aligning our ambitions with something much greater than ourselves. This belief has shaped my work, from building health-focused ventures to leading initiatives like the One Blood For Life Foundation. I have seen how small acts of service and mentorship can ripple outward, creating stronger and more united communities. When we show up with intention and humility, today’s obstacles can become tomorrow’s launchpad.

By Naina Grewal

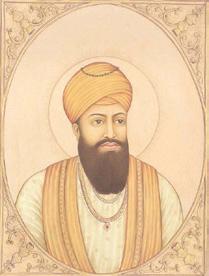

Since the foundation of Sikhism, Sikh women have stood as pillars of strength, spirituality, and service. At a time when many societies around the world relegated women to the background, Sikhism emphasized equality. Guru Nanak Dev Ji, the founder of the faith, openly challenged gender discrimination, asking, “Why call her bad, from whom kings are

born?” This powerful foundation set the tone for the generations of Sikh women who would go on to shape history.

■ DIVORCE

■ NULLITY / ANNULMENT

■ COHABITATION / SEPARATION AGREEMENTS

■ PENSION DIVISION

■ CLAIMS AGAINST IN-LAWS

■ CHILD / SPOUSAL SUPPORT

■ GUARDIANSHIP / CONTACT ORDERS / CUSTODY / ACCESS

■ ASSET / PROPERTY DIVISION

■ MAJOR ICBC CLAIMS

■ MEDICAL & DENTAL MALPRACTICE

■ EMPLOYMENT DISPUTES

■ PRIVATE INSURANCE DISPUTES

■ DEFAMATION

■ DEBT COLLECTION MATTERS

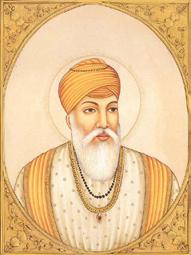

The tradition of langar, or the free community kitchen, is central to Sikh identity. While many associate this practice with the Gurus, it was Mata Khivi, wife of Guru Angad Dev Ji, who played a key role in establishing and expanding this beautiful tradition. Known for her compassion and dedication, she ensured that no one who came to the Guru’s court ever left hungry. Her commitment to equality, service, and nourishment helped lay the foundation for seva, selfless service, as a core Sikh value.

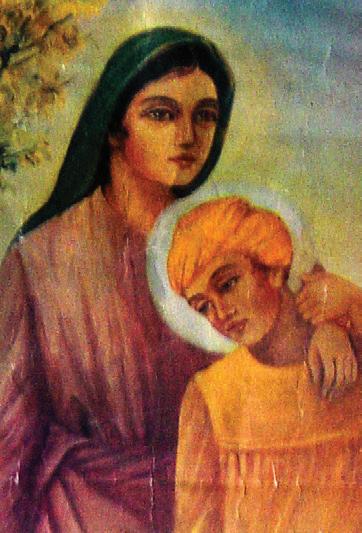

The story of Sikhism begins with a woman, Guru Nanak Dev Ji’s older sister, Bibi Nanaki. She was not only his sibling but also the first to recognize his spiritual greatness. Her unwavering support allowed Guru Nanak Dev Ji to begin his mission with confidence and purpose. Bibi Nanaki’s role is a reminder that behind every great leader, there can be quiet, powerful supporters who help shape history in their own way.

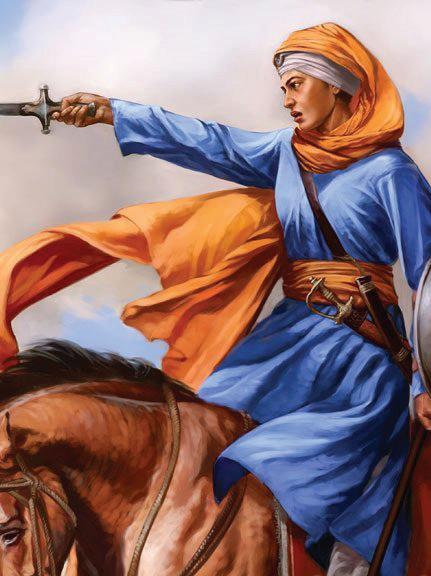

Mai Bhago is one of the most iconic women in Sikh history: a fearless warrior and spiritual guide during Guru Gobind Singh Ji’s time. When 40 soldiers, known as the Chali Mukte, abandoned their duties in battle, she confronted them with fierce conviction and rallied them back into action. Her leadership was so powerful that Guru Gobind Singh Ji, with just those 40 warriors by his side, went on to face an army of 10 lakh Mughal soldiers. Her legacy remains a powerful reminder of Sikh women’s resilience, valor, and unwavering commitment to justice and faith.

Mata Bhani, daughter of Guru Amar Das Ji, holds a special place in Sikh history as the wife of Guru Ram Das Ji and mother of Guru Arjan Dev Ji. Deeply devoted to the Sikh faith, she supported its growth from within the household. One story tells how she noticed Guru Amar Das Ji meditating on an unstable seat and silently held it steady with her bare hands, causing her palms to bleed. Touched by her devotion, the Guru blessed her, declaring her offspring would inherit the Guruship.

Mata Sahib Kaur holds a revered place in Sikh history as the spiritual mother of the Khalsa. Guru Gobind Singh Ji bestowed upon her the eternal title of “Mother of the Khalsa” during the creation of the Khalsa Panth in 1699. It was Mata Sahib Kaur who added sugar crystals, patasas, to the holy nectar, Amrit, symbolizing compassion and grace alongside courage and discipline.

Mata Gujri, wife of Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji and mother of Guru Gobind Singh Ji, is remembered for her quiet strength and deep spiritual conviction. After her husband’s martyrdom, she raised Guru Gobind Singh Ji with steadfast guidance. In her final days, she was imprisoned in freezing conditions with her younger grandson in Sirhind. Despite the hardship, she remained composed and unwavering in faith, inspiring her grandsons to stand bravely against tyranny. Mata Gujri stands alone in Sikh history as the only woman whose husband, son, and grandsons all became martyrs for the faith.

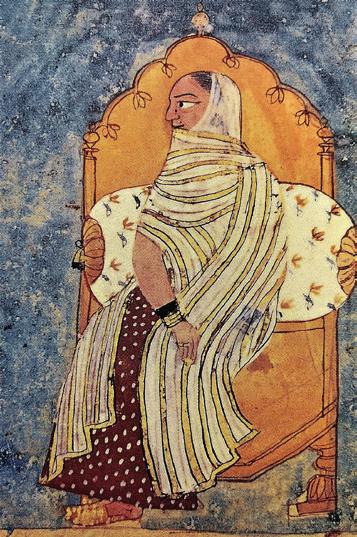

Maharani Jind Kaur, widow of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, was a fearless leader and one of the last reigning figures of the Sikh Empire. As regent to her young son Duleep Singh, she fiercely defended Punjab’s sovereignty during British expansion. In a tragic turn, the British took her young son from her and exiled her from the kingdom. Though imprisoned, she escaped custody, rallied allies, and made tireless efforts to reunite with Duleep Singh and restore the Sikh Empire. While her mission was ultimately unsuccessful, her sharp political acumen, unbreakable spirit, and refusal to be silenced by colonial forces cement her legacy as a queen, mother, and freedom fighter.

Punjabi names—Jaswinder, Rupinder, Sharnjeet, Harpinder, Gurparveen—carry the gravity of history and identity. Yet, sometimes, their multiple vowels leave others stumbling. So, we wring out the richness, condense them into Jas, Rup, Sharn, Harp, Gurp—names that fit neatly into mouths unaccustomed to the syllables of the land of five rivers.

When my name was chosen, it wasn’t a random decision—it was a collaboration between the Almighty and my family. The Guru Granth Sahib gifted me a beginning. The letter ‘ਹ’(ha-ha)—became

By Harpreet Kaur Kang

Harpreet, meaning the one who loves God. But growing up, I’d slice my name in half, making it smaller, easier. I’d listen to the effortless way others’ names rolled off tongues, watch how easily they were remembered. In classrooms, I shrank my name into something less noticeable—Harp. A name that wouldn’t take up too much space or time. My Punjabi would whisper to me, asking why it was always measured against English, like that cousin every brown mom constantly brags about. I ignored its voice.

Then, one day, my Nani made me see my

name differently. Her full name was Gurmej Kaur Hayer. Jokingly, I told her I’d start calling her GKH— to make her sound hip and cool. She laughed but replied in Punjabi, “I like my name. It’s the name my parents gave me; the name God wanted me to have. Why would I change a gift from God?”

I’ve never seen God, but my Nani was the closest I’d ever gotten. And in that moment, it felt like she was passing down a piece of divine wisdom.

Slowly, I realized my name wasn’t meant to be whispered. Punjabi isn’t quiet—it’s a language that

speaks in bold, a language with its volume on loud.

My name is a privilege, a gift shaped by ancestors who knew how to roar. It carries the courage of my Nani, who raised five children. It carries the strength of my mother, who packed her bags and left home for Canada to give me a better future. It carries the resilience of my parents, who worked long shifts and early mornings so I could have a voice. Why hide a name woven from sacrifice and love? Why not say it with pride?

Sikh names aren’t just names. They are blessings, drawn from a

Sikh names aren’t just names. They are blessings, drawn from a sacred book of poetry and wisdom. There is power in hearing a full Punjabi name pronounced, each letter rolling off the tongue like a hymn, purifying the space it enters. A bit of God lingers in these names.

sacred book of poetry and wisdom. There is power in hearing a full Punjabi name pronounced, each letter rolling off the tongue like a hymn, purifying the space it enters. A bit of God lingers in these names. Our names are more than just words; they are a greeting, a Sat Sri Akal. They are a firm handshake from an uncle, a tight embrace from a Bibi who just wants to feed you. They are long, accent-heavy, and deeply intentional—crafted by God, presented to us so that when we say them, we ignite an emotion.

By Jasleen Kaur Brar

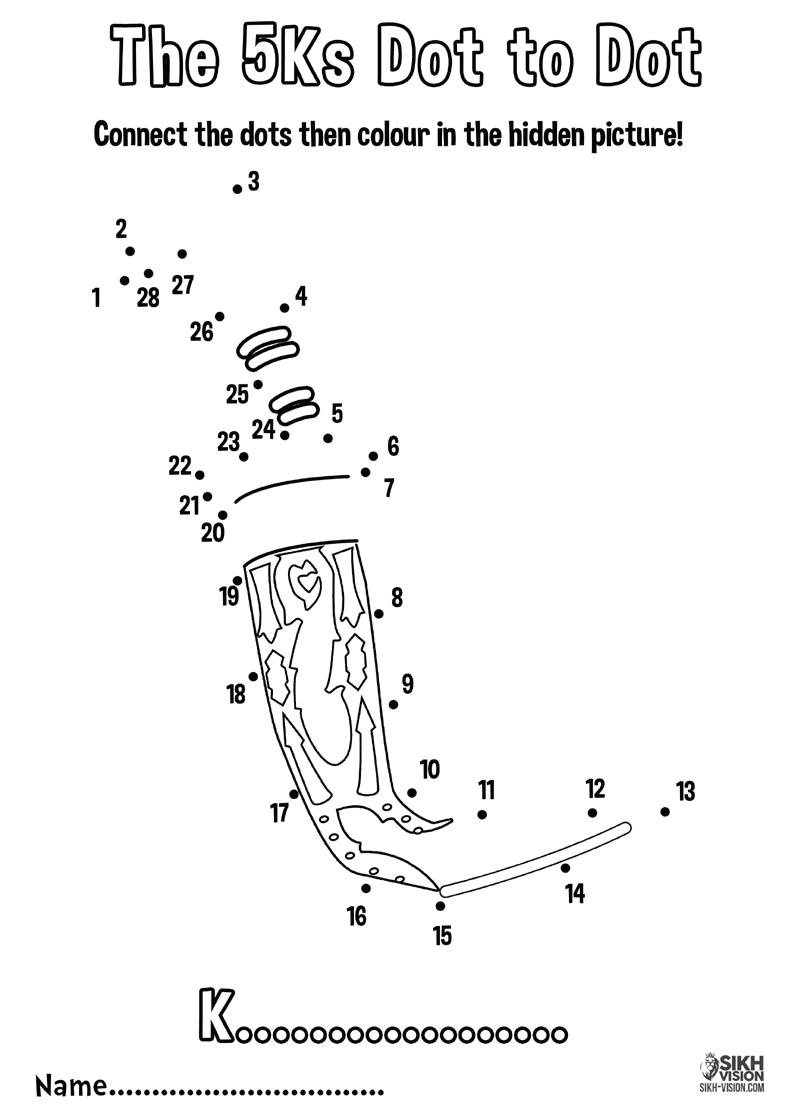

As we honor the Sikh Heritage Month and prepare for Vaisakhi, it’s important to understand the significance of the five Ks of Sikhi. Initiated (Amritdhari) Sikhs commit to following the Sikh Code of Conduct, which includes daily meditation and wearing the five Sikh articles of faith, also known as the five Ks or panj kakaar, at all times. The 5 Ks date from the creation of the Khalsa Panth by Guru Gobind Singh in 1699. They are not only an external aspect of a Sikh’s identity but also represent deep spiritual commitments. Initiated Sikhs regard them as a part of their body. The five Ks are as follows:

Unshorn hair, known as kesh, symbolizes the acceptance of God’s will. Sikhs consider all body hair as a sacred gift from God. Initiated Sikhs keep their hair covered at all times with a Dastaar (turban or head-covering), which represents spiritual wisdom and equality. Maintaining uncut hair is a way of expressing love for God and serves as a visual reminder of His perfection.

A kanga is a small wooden comb worn in uncut hair. The kanga promotes cleanliness and reflects the Sikh values of self-care and discipline. Sikhs comb their hair at least twice a day to keep it clean and tidy. Just as the wooden comb helps maintain cleanliness and removes dead hair, Gurbani, God’s hymn, purifies the mind and reminds Sikhs that human life is limited, much like the hair they shed.

is an iron or steel bracelet worn on a Sikh’s wrist and has many acts as a reminder for Sikhs to practice righteousness and selfless service with their hands. The circular shape signifies there is no beginning or end of the Creator. should be made of iron, as it is a strong, inexpensive, and accessible metal for all. If a Sikh is allergic to iron, a steel kara can be should not be made of gold or silver, as these metals are not strong and are considered ornaments rather than serving the true purpose kara.

The kirpan is a significant article of faith that looks like a miniature sword. The word kirpan means grace and honor and signifies the Sikh’s duty to stand up against injustice. It symbolizes bravery and protection of the weak and innocent. Initiated Sikhs wear the kirpan sheathed and restrained in a cloth belt called a gatra. The kirpan should not be regarded as just a sword because Sikhs who wear the kirpan have a spiritual responsibility to abide by the Sikh values of justice, protection, and compassion.

A kachera is a cotton undergarment that symbolizes chastity, discipline, and self-control. The kachera assists in regulating body temperature and reminds Sikhs to control lust, one of the five evils in Sikhi.

These five sacred articles of faith stand as powerful reminders of a Sikh’s commitment to justice, righteousness, compassion, and selfless service. By embracing the five Ks, Sikhs honor and carry forward Guru Gobind Singh Ji’s legacy with unwavering devotion.

By Dr Pargat Singh Bhurji MD, FRCP(C)

Globally, we will be celebrating the 326th birthday of the formation of the order of Khalsa this year. The word Khalsa originates

“Raaj

karega khalsa, aaki rahe na koi, Khuar hue sabh milenge, bachey sharan jo hoye.”

The pure consciousness of Khalsa will be that the rulers and sinners will be vanquished. Those separated will unite, and all the devotees shall be saved.

from the word khalis, meaning pure. Khalsa is pure in thoughts, pure in action, and pure in commitment.

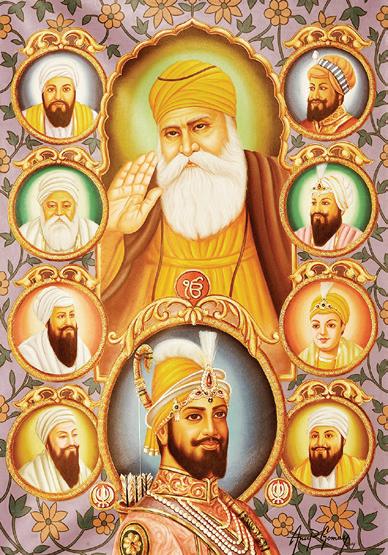

We need to go back three centuries in the past when it was ordained into the Sikh faith. The

first nine Guru jis made us saints first, then came the miraculous act of being a soldier, which was done during the time of the 10th Guru ji.

Several months before Vaisakhi of 1699, our tenth Master, Guru

Gobind Singh Ji, invited his followers from all over India to come to Anandpur Sahib. As a result, on that particular day, hundreds of devotees and onlookers gathered. Many came as a sign of respect for the Guru and following his invi-

tation, while some came out of curiosity. On the appointed day, the Guru addressed the congregants with a stirring oration on his divine mission of restoring their faith and preserving Dharma (righteousness).

After his inspirational discourse, he flashed his samsheer and said that every great deed was preceded by equally great sacrifice. He asked, with a naked sword in his hand, “Is there anyone among you who is prepared to die for their faith?” When people heard his call, they were taken aback. Some of

the wavering followers left the congregation, while others began to look at one another in amazement. It was a crowd of over 80,000 people.

After a few minutes, a brave Sikh from Lahore named Daya Ram stood up and offered his head to the Master. The Guru took him to a tent pitched close by and, after some time, came out with a blood-dripping sword. The Guru repeated his demand, calling for another Sikh who was prepared to die at his command. At this second call, even more people were shocked, and

some were frightened. A few more of the wavering followers discreetly began to filter out of the congregation.

However, to the shock of many, another person stood up. The second Sikh who offered himself was Dharam Das. This amazing episode did not end there. Soon, three more—Mohkam Chand, Sahib Chand, and Himmat Rai, offered their heads to the Guru. Each Sikh was taken into the tent, and some thought that they could now hear a ‘thud’ sound—as if the sword was falling on the neck of the Sikh.

Guru ji then brought these 5 brave men out of the tent, wearing the 5 Kakkars Kesh (uncut hair), Kanga (wooden comb), Kara (iron bracelet), Kachera (military shots) and Kirpan (sword). Guru ji prepared Amrit with water in a sarab loh (pure iron) vessel, Mata Sahib Kaur put patasey (sugar puffs) into the water, and a khanda (double-edge sword) was used to stir it while the bani of japji, jaap, savayiyae, choupai benti and Anand Sahib were recited. Guru ji then baptized these five brave hearts by sprinkling Amrit in their eyes and hair and asked them to drink it five times while saying “Waheguru Ji Ka Khalsa,

Waheguru Ji Ki Fateh!”

Guru ji called them the Panj Pyaare or the beloved ones, changing their names to Daya Singh, Dharam Singh, Himmat Singh, Mohkam Singh, and Sahib Singh. These are the stages of the spiritual journey through which one will have to start from Daya to meeting Waheguru ji.

Guru Gobind Rai then stood in front of these Panj Pyaare and asked for the blessing of the Amrit, changing him to Guru Gobind Singh Ji. This act created the abolition of prejudice, equality, democracy, common worship, and a common external appearance—combining Bhakti and Shakti.

The creation of Khalsa culminates 240 years of training by each Guru ji to create the perfect image of a saint, scholar, and soldier. In order to mold his personality, the Guru inculcated in him the five virtues - Sacrifice, Cleanliness, Honesty, Charity, and Courage, and prescribed Rehat or Maryada - the Sikh code of discipline.

In Surrey and Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, we have some of the world’s largest Nagar Kirtans to celebrate the birth of Khalsa with a devotional congregation of over 650,000 people.

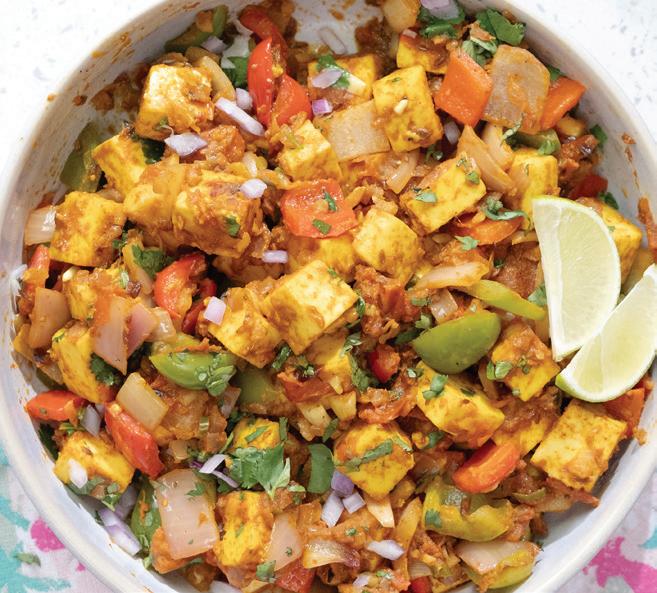

Born in Victoria, B.C., and raised in Surrey, Raj Thandhi never expected food to be her calling. A trained graphic designer, her love for cooking truly ignited after her children were born. What started as an effort to decode heritage recipes soon became a mission—to preserve and translate traditional Punjabi flavors for a new generation.

From perfecting age-old techniques to adapting them for a North American kitchen, she built a thriving online community of over 100,000 people who connect through cultural cuisine. To her, keeping Punjabi flavors on the table matters most—whether it’s through a classic dish, a creative fusion, or a quick weeknight meal.

Now a professional recipe developer and food stylist, Raj collaborates with multinational brands to spotlight Punjabi flavors, ensuring they get the recognition they deserve. Her expertise has landed her on the pages of the Vancouver Sun, Globe & Mail, The Washington Post, and even on CBC.

But she isn’t stopping there. With a hunger for knowledge, she’s now attending culinary school to earn her professional chef designation—turning a lifelong passion into a full-time career.

Through her work, Raj Thandhi proves that food is more than just sustenance—it’s a bridge between generations, a celebration of culture, and a way to keep tradition alive in a fast-changing world.

By Chef Raj Thandhi

• 4 tablespoons strawberry puree

• 1 tablespoon rose & basil simple syrup

• 1 ½ cups tonic water

• To make the strawberry puree, blend together - 2 cups of fresh or frozen California strawberries, 1 tbsp honey, and the juice of one lime. You can store this in the fridge for 3-5 days.

• To make the rose & basil simple syrup boil - 1 cup water, 1 cup sugar, 3-4 basil leaves, and 2 teaspoons of rose water. Reduce by half. Remove the basil leaves and store in the fridge for up to three weeks.

• For the Strawberry Rose margarita, mix 4 tablespoons of the strawberry puree with 1 tablespoon of the rose & basil simple syrup in 1 ½ cups of tonic water.

HOT TIP

The rose & basil syrup tastes great over vanilla ice cream too!

By Chef Raj Thandhi

• 3 tablespoons dry mango powder (amchoor powder)

• 1 1/2 cup cold water

• 3/4 cup powdered gur (shakkar)

• 1 teaspoon black salt (kala namak)

• 1/2 teaspoon deghi mirch

• 1/2 tablespoon roasted cumin powder (jeera)

• 1 teaspoon dry ginger

• Add the amchoor powder to cold water and whisk well. Make sure you whisk out any lumps.

• Bring the water and amchoor mixture to a boil on medium heat. Reduce to a simmer and let cook for 2 minutes.

• Add in the shakkar and simmer for 10 minutes, stirring occasionally. At this point, taste the chutney and add

more sugar if you’d like it sweeter.

• Add the rest of the powdered spices and mix well. Simmer for another 5 minutes.

• Strain the mixture into a glass jar. Cool and store in the fridge for up to 3 months.

Always use a clean spoon when pouring the chutney to prevent it from going bad.

By Chef Raj Thandhi

• 4 cups thinly sliced veggies - a mix of red onion, carrot, cucumber, bell pepper, and daikon

• 2 tablespoons tamarind (imli)

• ½ cup water

• ½ teaspoon black salt (kala namak)

• ½ teaspoon salt

• ½ tablespoon brown sugar

• ½ teaspoon deghi mirch

• Juice of half a lime

• ¼ cup chopped cilantro

• Soak the imli in water for ½ an hour to an hour. In the meantime, slice all the veggies into thin julienne style strips.

• Squeeze any seeds out of the imli and strain it through a sieve. Keep the water and toss the pulp bits.

• Add the imli water and seasonings to a bowl. Toss in your

veggies, top with cilantro and a squeeze of lime.

If you are making this salad ahead of time, keep the imli water in a separate bowl and toss just before serving.

Vaisakhi Recipes

By Chef Raj Thandhi

• 1 tablespoon butter

• 1 teaspoon cumin seeds (jeera)

• 1 cup chopped onions

• 1 tablespoon each chopped garlic and ginger

• 1 green chili chopped (optional)

• 2 tablespoons tomato paste

• 1 teaspoon salt

• 1 teaspoon cumin powder

• 1 teaspoon coriander powder

• 1.5 cups massar (red lentils)

• 5 cups water

• 1 tablespoon ginger garlic paste

• 1 teaspoon salt

• 1/2 teaspoon turmeric powder (haldi)

• 1/2 tablespoon coriander powder

• 1/2 tablespoon cumin powder

• 1/2 tablespoon deghi mirch (use spicy red chili if you prefer)

• 2 cups of grated fresh broccoli

• 1 teaspoon garam masala

• Juice of 1/2 a lemon (optional)

• Wash the lentils and add them to the water in a large pot. Add the ginger garlic paste, salt, turmeric, coriander powder, and deghi mirch.

• Bring the mixture to a boil, then reduce the heat to medium-low and simmer until the lentils are tender, about 15 minutes.

• Once the lentils are cooked, add the grated broccoli to the pot. Stir well and cook for 5-7 minutes.

• Prepare the tadka: In a small pan, melt the butter over medium heat. Add cumin seeds and let them sizzle for a few seconds. Add chopped onions and sauté until they are translucent and lightly browned. Add chopped garlic, ginger, and green chili (if using). Cook for another minute. Stir in the tomato paste, salt, cumin powder, and coriander powder. Cook for about 2 minutes, until the mixture is fragrant.

• Combine the tadka with the dal: Pour the tadka mixture into the pot with the lentils and broccoli. Stir well to combine. Add the garam masala and mix thoroughly.

• Taste and adjust the seasoning as needed. If desired, squeeze the juice of half a lemon over the dal for a bit of brightness.

• Serve hot with rice or roti.

Vaisakhi Recipes

By Chef Raj Thandhi

Tadka: Paneer:

• 3 tablespoons oil

• 1 teaspoon cumin seeds (jeera)

• ½ cup chopped onions

• 2 garlic cloves chopped

• 1 inch piece of ginger chopped

• 1 green chili chopped (optional)

• 1 cup tomatoes chopped

• 1 block of paneer chopped into cubes

• 1 tablespoon oil

• 1 teaspoon salt

• ½ teaspoon black pepper

• 1 teaspoon turmeric

• ½ tablespoon cumin powder

• 1 tablespoon coriander powder

• ½ tablespoon deghi

mirch or paprika

• ½ cup onion chopped into petals

• ½ cup each red and green bell pepper chopped into petals

• Marinate paneer cubes with oil and all the spices listed. While it rests, move onto the tadka/tempering.

• Make a tadka in the air fryer using all the listed ingredients. To do this - Add all of your tadka ingredients to an oven-safe cooking pan that fits in your air fryer and cook at 360 degrees Fahrenheit for 8-10 minutes, stirring every 3 minutes.

• Once the tadka is ready, add in the paneer, onions, and bell peppers to the dish. Mix well and cook for another 8 minutes in the air fryer. Take it out at 4 minutes and mix.

• Finish with a squeeze of lime and some chopped cilantro.

To cook sabzi style dishes in the air fryer, chop things a little smaller than you would for stovetop cooking. In this preparation, I cut the bell peppers and onions smaller than usual.

By Chef Raj Thandhi

• Zest of 2 oranges

• 1 cup fresh or bottled orange juice

• 3 tablespoons soy sauce

• 1 teaspoon sesame oil

• ½ cup sugar

• ¼ cup rice vinegar

• 1 teaspoon red chili flakes (increase if you prefer more heat)

• 1 tablespoon garlic chopped

• ½ tablespoon ginger chopped

• 2 tablespoons cornstarch

• 3 tablespoons water

• 1 block of paneer cubed

• ½ cup cream

• ½ cup all-purpose flour

• Salt & pepper

• Oil for frying

• Start by adding all the sauce ingredients to a heavy-bottomed pan over medium-high heat. Bring to a light boil.

• Mix cornstarch and water to create a slurry, add slowly to the sauce and whisk continuously. Cook for 3-4 minutes and switch off the heat.

• Mix the cream, all-purpose flour, and salt and pepper.

• Heat a pan of oil over medium high heat. Dip the paneer cubes in the cream mixture and deep fry until golden brown.

• Add the fried paneer to the orange sauce, mix well and garnish with cilantro, green onion, and red chilies for heat.

Orange Paneer pairs perfectly with Masala Fried Ricethe recipe for that can be found on the next page.

By Chef Raj Thandhi

• 3 cups cooked cool basmati rice

• 2 tablespoons ghee

• 1 tablespoon garam masala

• 1 teaspoon cumin powder

• 1 teaspoon coriander powder

• ½ teaspoon turmeric powder

• 1 teaspoon deghi mirch

• 1 teaspoon salt (adjust to your liking)

• 2 tbsp oil for cooking rice

• ½ tablespoon cumin seeds

• 1 tablespoon garlic chopped

• 1 tablespoon ginger chopped

• 1 cup onion diced

• 1 tablespoon tomato paste

• Hot water for cooking

• Cilantro for garnish

• Lemon or lime for finishing

• Add ghee to the cooked rice. Mix well and coat all the grains of rice with ghee.

• Add garam masala, cumin powder, turmeric powder, deghi mirch and salt to the rice and mix well.

• Heat oil to medium high in a pan and toast cumin seeds for 90 seconds. Add the garlic and green chili and cook for 60-90 seconds.

• Add in the onion and cook for 2-3 minutes until it’s light and translucent.

• Next add in the tomato paste and mix well. Add a splash of hot water to prevent burning. Cook for 60 seconds.

• Add the seasoned rice to the pan and mix well. Increase the heat to high and cook everything together for 2-3 minutes.

• Switch off the heat, finish with freshly chopped coriander and a squeeze of lemon or lime.

By Chef Raj Thandhi

• 2 tablespoons ghee or butter

• 1 cinnamon stick

• 1 star anise flower

• 2 cloves

• 3 cardamom pods slightly crushed

• 1 cup prepared tadka

• 1/2 cup thick plain yogurt (dahi)

• 1 cup grated cauliflower

• 3 cups walnut meat – made from 2 cups of whole walnuts

• 1/4 cup - 1/2 cup hot water – as needed.

• 1 tablespoon deghi mirch or paprika

• 1 tablespoon garam masala

• Chopped cilantro for garnish

• Start by soaking your walnuts for a minimum of 4 hours (or overnight if time permits).

• Prepare the walnut meat by draining the walnuts and pulsing them gently in your mixer. Don’t chop them, pulsing will create a more meat like texture. More details in this recipe.

• Add ghee to a pan on medium high heat and toast the cinnamon, star anise, cardamom, and cloves for 90 seconds, until fragrant.

• Add your prepared tadka. For this recipe, I like to add extra heat with Kashmiri red chilies to my tarka. Walnuts hold up really well to the spice, however, you can limit it if you prefer.

• Once your tadka is heated through, drop the heat of your stove down to low and add the dahi slowly. Before you add the dahi, whisk it lightly to prevent curdling.

• Once the dahi and tadka are combined, add your cauliflower and walnuts. Stir well and cook on medium for 5-7 minutes to soften the cauliflower and walnuts. At this point the mixture may thicken up. Add 1/4 cup to 1/2 cup of boiling hot water to create a slight gravy consistency. Now taste for seasoning and adjust salt if needed.

• Add degi mirch and garam masala, combine well and cook for another 2 minutes.

• Garnish with cilantro and serve hot.

If you are reheating the Walnut Keema, you may need to add a little hot water to loosen things up.

By Chef Raj Thandhi

• ½ cup milk

• ¼ cup chopped strawberries

• 1 ½ cups all-purpose flour

• 1 ½ teaspoon baking powder

• ¾ teaspoon baking soda

• 1 cup dahi or yogurt (avoid Greek Yogurt)

• 1 cup powdered sugar

• ⅓ cup melted butter

• 1 to 1 ½ cups sliced strawberries for decoration

• Make strawberry milk by blending strawberries and milk.

• Sieve the flour, baking powder, and baking soda. Mix all three together.

• In a large mixing bowl whisk the yogurt well. Add in the butter and whisk again to combine.

• Add in the sugar and cream together with the yogurt mixture.

• Add in the strawberry milk, combine gently.

• Now add in the flour in small batches, folding together gently.

• Pour the batter into a greased cake tin.

• Bake at 365 degrees Fahrenheit for 35 minutes, or until a toothpick inserted in the centre comes out clean.

By Chef Raj Thandhi

• 6 cups grated carrots (approximately 1.5 lbs of carrots)

• 5 ½ cups milk

• ¾ cups sugar

• ¼ teaspoon cardamom powder

• ¼ -½ cups mixed nuts (I used cashews and slivered almonds)

• Ghyo/ghee for frying nuts (optional)

• Start by bringing the milk up to a boil and letting it cook for 2-3 minutes at a rolling boil. Add in the carrots and bring the temperature down to low/medium. You are looking for a light simmer. Keep stirring the carrot mixture frequently. You don’t want the milk to stick to the pot.

• Cook the carrot mixture for 45 minutes and then add in the sugar and mix well.

• At this point you can turn the heat up to medium and cook for another 15-20 minutes or until the mixture comes together (it will get thicker as it cools). Keep stirring the entire time so the mixture doesn’t burn.

• Remove from the heat and top with cardamom powder and nuts.

By Chef Raj Thandhi

• 1 kg pureed dates

• 4 tablespoons tahini

• 1 cup chopped salted Hawaii macadamia nuts

• 2 cups puffed rice

• ⅓ cup sunflower seeds

• ¼ cup chia seeds

• ½ cup freeze dried raspberries

• ½ cup chopped dried apricots

• 1-½ cups melted dark chocolate

• 2 tablespoons finely chopped Hawaii macadamia nuts for topping

• Warm the pureed dates in the microwave for 2-3 minutes to make them softer and easier to mix. Add in the tahini and puffed rice, mix well to combine. Next, add the Hawaii macadamia nuts, chia and sunflower seeds, raspberries and apricots. Mix everything together until well combined.

• Press the mixture into a sheet pan and refrigerate for 30 minutes.

• Melt chocolate and pour over the date mixture, then top with additional Hawaii macadamia nuts. Chill in the fridge for an additional 30 minutes to set the chocolate before slicing.

By Chef Raj Thandhi

• 300 gms Parle G Biscuits

• ¾ cup melted ghee or butter

• 1 block paneer grated (approximately 341 gms)

• 1 ¼ cups heavy cream

• 1 tin sweetened condensed milk

• ¼ cup of corn starch

• 1.5 cups of mango puree

• Start by pureeing the Parle G biscuits to a fine powder. Mix with ghee/butter and pack on the base of the cheesecake pan. I recommend using a springform pan. Place in the fridge for 30 minutes.

• Mix the paneer, condensed milk, and cornstarch together, add to a pan and then top with whipping cream.

• Cook the mixture on low heat for 18-20 minutes, stirring frequently. Cool the mixture for 10 minutes.

• Pour the paneer mixture over the cookie base and place in the fridge for 4-6 hours or overnight.

By Harinder Singh

Harinder Singh is a thinker, author, and educator. He is the co-founder of the Sikh Research Institute and the Panjab Digital Library. He tweets at @1Force.

“In the constitution of the Khalsa commonwealth, the greatest act of genius of Guru Gobind Singh was when he transferred the divine sovereignty vested in him to the God-inspired people, the Khalsa.” - Prof. Puran Singh On Vaisakhi Day 1699, ‘The Rider of the Blue Steed’ inaugurated a highly dynamic personality – the Khalsa. This community’s ‘Light of Life’ ceaselessly radiates glory, justice and love. The Nash doctrine enforced on Vaisakhi day freed us from the shackles of slavery: shattered inequities due

to caste-apartheid or lineage, eliminated doubts borne out of a polluted mind, and eradicated sexism through annihilation of patriarchal hegemony.

Today, Vaisakhi has become a reminder to all Sikhs to reflect on the Guru’s vision of personal and community development as articulated in the Guru Granth Sahib. It implores us to revive the Spirit Ascendant that changed the destiny of South Asia and beyond through unparalleled sacrifices. It demands us to think strategically and respond to the critical issues

and challenges we Sikhs are facing worldwide, both internally and externally.

Let us become active agents of freedom. Let us treat women with dignity and respect in our private and public lives. Let us identify and align with the unrepresented and under-represented communities: from the Dalit struggle in India to genocideladen Darfur. All this is possible once every Sikh recognizes and maintains the Guru-granted sovereignty.

In today’s global Sikh reality, Vaisakhi translates into making genuine and concerted efforts on three fronts simultaneously: break intra-Sikh barriers of prejudice and hostility among people and institutions due to gender, caste, social-strata, tribe or clan; confront global powers, not conform, when they act against the well-being of the Sikh nation and the rest of humanity; and build inter-religious understanding, especially where prejudice runs strong through strategic alliances with likeminded people who live by the principle, ‘The end does not justify the means’.

Let us become active agents of freedom. Let us treat women with dignity and respect in

our private and public lives. Let us identify and align with the unrepresented and underrepresented communities: from the Dalit struggle in India to genocide-laden Darfur. All this is possible once every Sikh recognizes and maintains the Guru-granted sovereignty. Guru Nanak and Guru Arjan share great insights with us on Vaisakhi. To them, Vaisakhi is a beautiful moment: submitting to the Guru in totality, feeling the divine presence in everyday life, and discovering the Divine via infinite wisdom. At that moment, one is ready to be part of the Guru Khalsa Panth, the collective whose utter volunteer spirit becomes Guru-like. This is not the panth of jutts, bhapas, ravidasis, or the androcentric males. Our Panth is One Panth that belongs to the One Force. One Panth that frees and empowers each and every person. One Panth that lights a fire in the gut and explodes the creative potential. One Panth that makes us humble and courageous concurrently. One Panth that delivers justice to the enemy within and outside. One Panth that is sharpened by the 10 Nanaks and follows the Guru Granth Sahib.

Which Panth do you belong to? Take charge. Claim your legacy!

The golden fields sway in the breeze, Harvest ripe beneath the trees. April dawns with skies so bright, Vaisakhi comes, bathed in light.