Лінгвоцид*

*Linguicide: the revival of Ukrainian language over the past decade

ї

ґ

2 1. 2. 3.

*Nations do not die from heart attacks. First, their language is taken away. Lina Kostenko (1930-)

Famous Ukrainian poet and one of the founders of the Sixtiers movement

не від інфаркту. Спочатку їм відбирає мову»*

«Нації вмирають

3

Content 4 Introduction.................................................................6 Centennial Oppression.............................................8 Ukrainian as a Linguistic Afterthought..............16 ‘The Rustle of Language’........................................20 Kiev or Kyiv?...............................................................24 Conclusion .................................................................26 References...................................................................28 ї ґ ґ ї

5 ґїї ґ ґ

Introduction

Growing up bilingual in a predominantly Russian-speaking family, I have not genuinely questioned why so many Ukrainians, including me, speak Russian. Of course, it is to do with the Soviet Union and its predecessors. But I have never dug enough to understand that - this fact is an aftermath of years of colonialism and suppression of the Ukrainian language and culture.

After the USSR collapsed, the Ukrainian school system changed drastically as to what kind of information was taught to the students. History books had to be rewritten and cleansed from Soviet propaganda. The curriculums changed, and Ukrainian literature had a rebirth. My experience was different to my parents’ as post-Soviet education didn’t have the same amount of propaganda. However, the echoes of the USSR were still present when I was a child and the fact that so many Ukrainians still speak Russian is one of them.

To be a Ukrainian student means you have to face and unravel the trauma of your ancestors. For a young impressionable child, it can be a bit much. I remember how difficult it was sometimes to learn and not be deeply affected by the History lessons. All this injustice makes you feel angry and helpless. However, Ukrainian people always prove to themselves and the world that they are strong-willed and will do anything to preserve their culture and the right to self-determination.

6

This zine is an attempt to raise awareness of what has been happening to the Ukrainian language over the past centuries and how it has transformed into the modern language that Ukrainians use now. What events have shaped it? How, despite all the prohibitions, the Ukrainian language has not only survived but has also spread all over the world and the number of people who use Ukrainian consistently growing as well.

It is also my way of spreading the truth and exploring my culture. The year 2022 has forever changed the course of history for the Ukrainian language and how it is perceived in the world. Living abroad, I believe it is my mission to be vocal about my culture and the Ukrainian people’s sufferings. It is my way of honouring people who came before me and paving the way for people to come.

7

Centennnial

The usage of the Ukrainian language was banned more than 134 times by the Russian government during the 400 years of occupation, extending to the printing of books in Ukrainian, traditional songs, libraries, Ukrainian schools and theatre, essentially anything to do with Ukrainian culture (Sokolova, 2022). The forbidden literature was either confiscated or in most cases destroyed. Ukrainians who would go against the regime were sent to Siberia, jailed or executed.

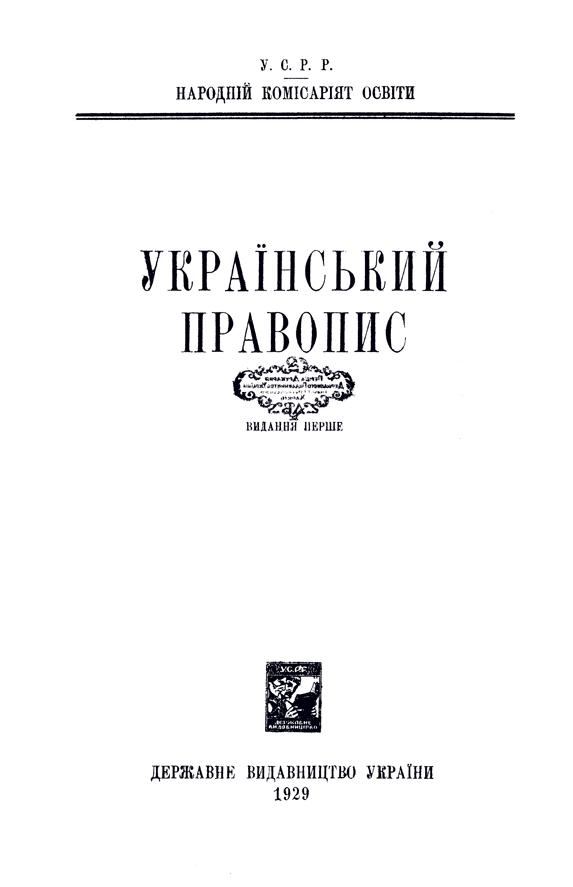

The Orthography of Kharkiv in 1928 became of one the most successful examples of Ukrainization. It was an orthography of the Ukrainian language adopted in 1927 with the compilers including well-known linguists and writers from Galicia and Soviet Ukraine (Svidomi and the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, 2022). During this period, the Ukrainian language benefited from the arrival of new dictionaries and textbooks (Flier and Graziosi, 2018). As George Shevelov, a Ukrainian-American professor and linguist said:

… “Ukrainization reasserted the existence of Ukrainian as a standard language…, extended the mastery of that standard language through various strata of the population, and contributed to its survival during the coming years of constraint and persecution.” …

8

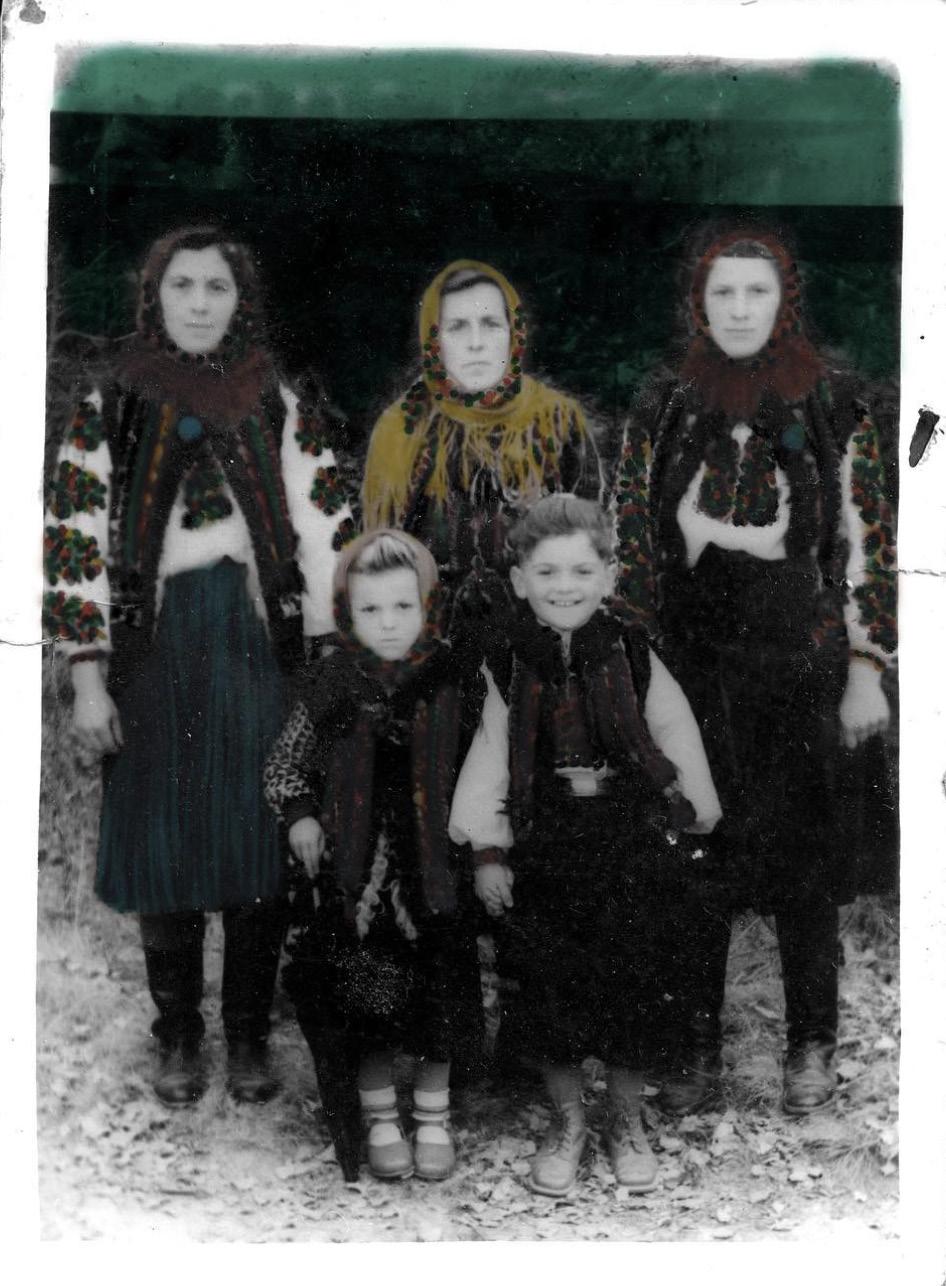

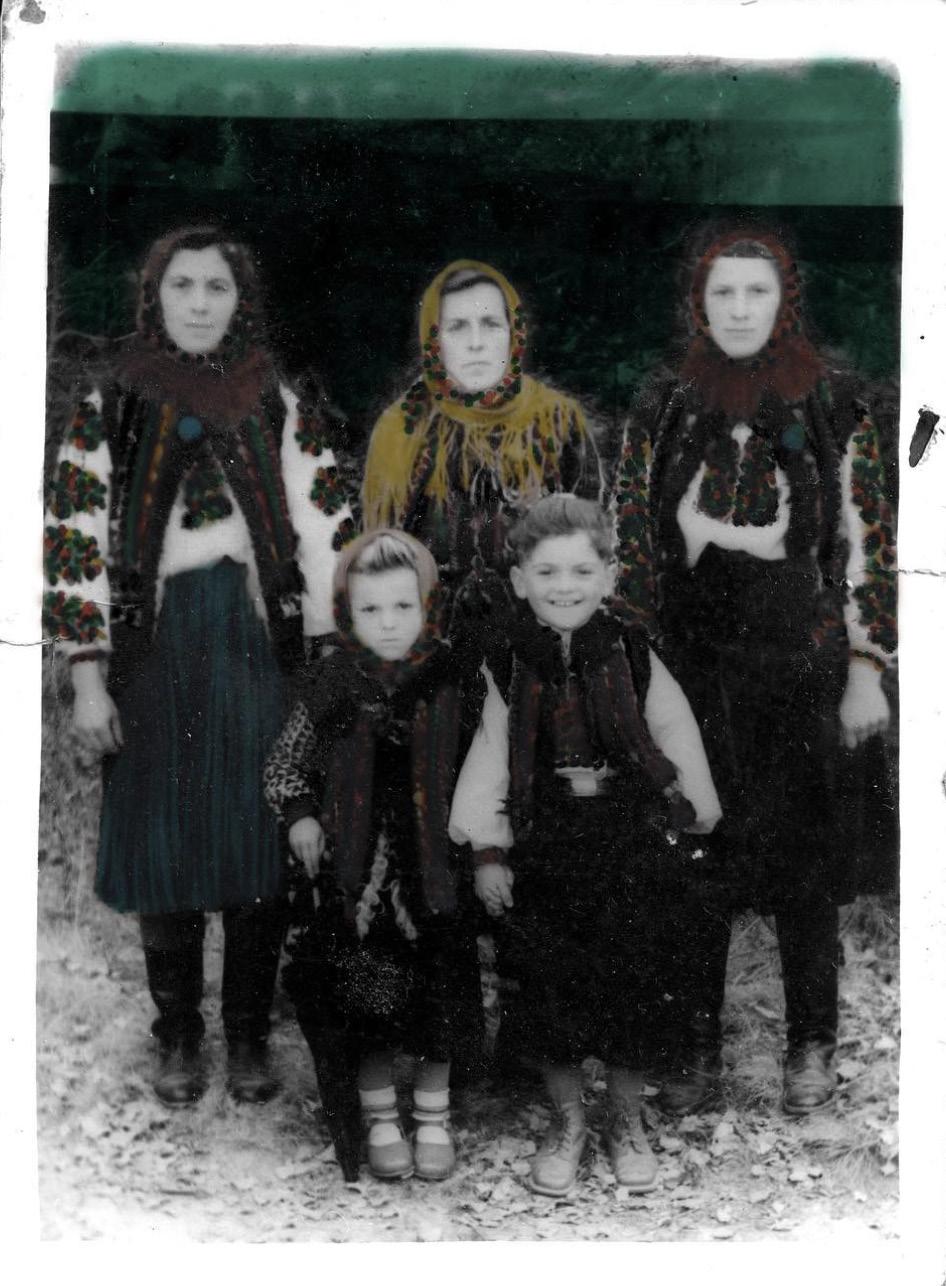

This photo became a symbol of the extermination of the Ukrainian intelligentsia by the Stalinist regime.

Stalin’s reversion of Ukrainization in the 1930s coincided with the collectivisation, the Holodomor, and the annihilation of most of the Ukrainian intellectual elite, also known as the Executed Renaissance, which resulted in the launching of a calculated campaign to russify everything about the Ukrainian language in the USSR, to make Ukrainian as close to Russian as possible, and to vandalise its clear distinctiveness. The more powerful the Ukrainian language was becoming, the harder the pressure was exerted by the Russian Empire.

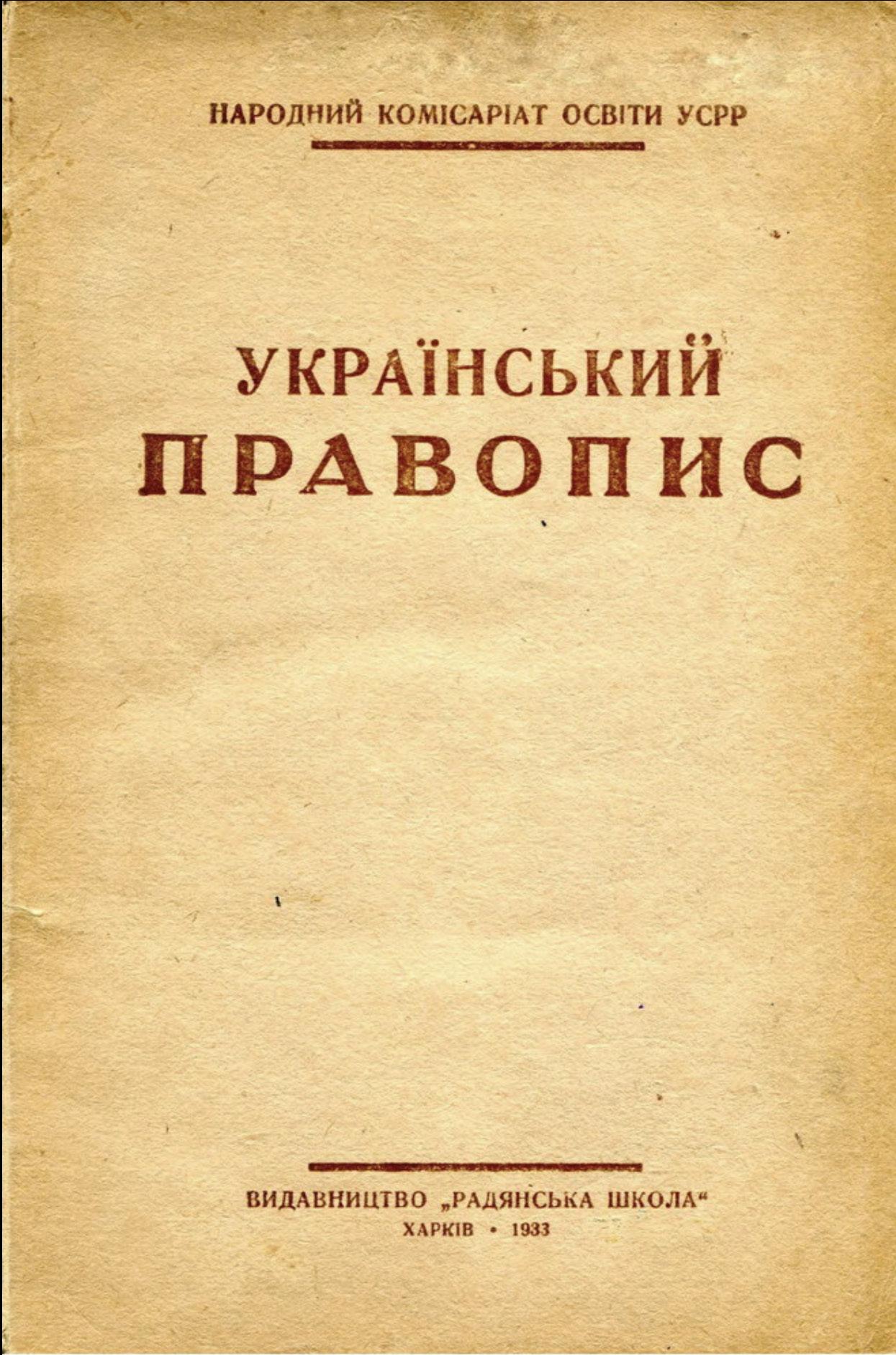

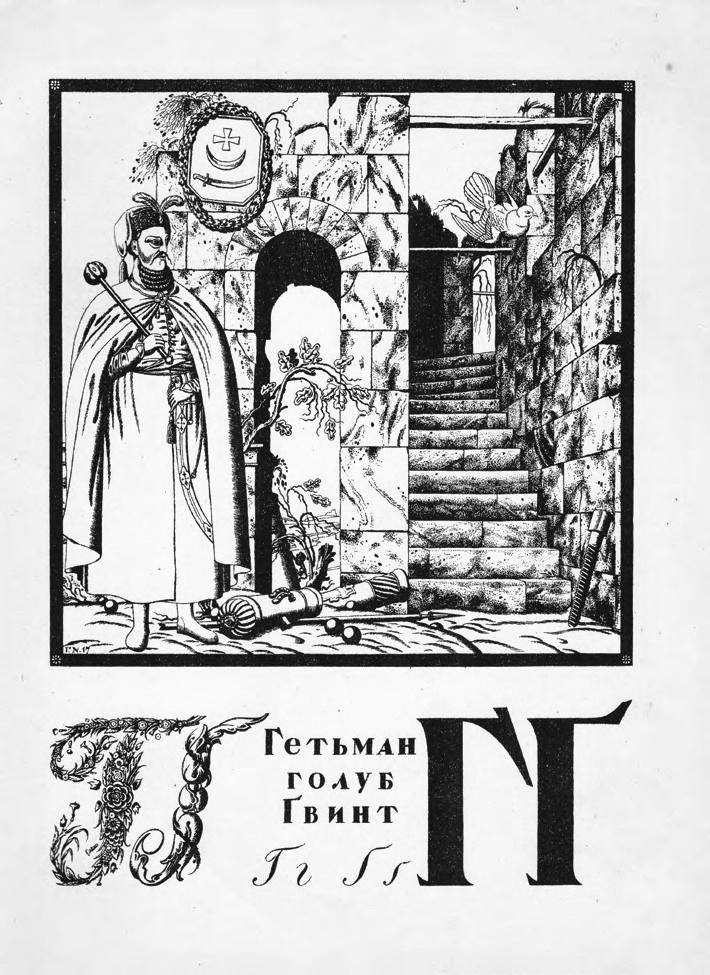

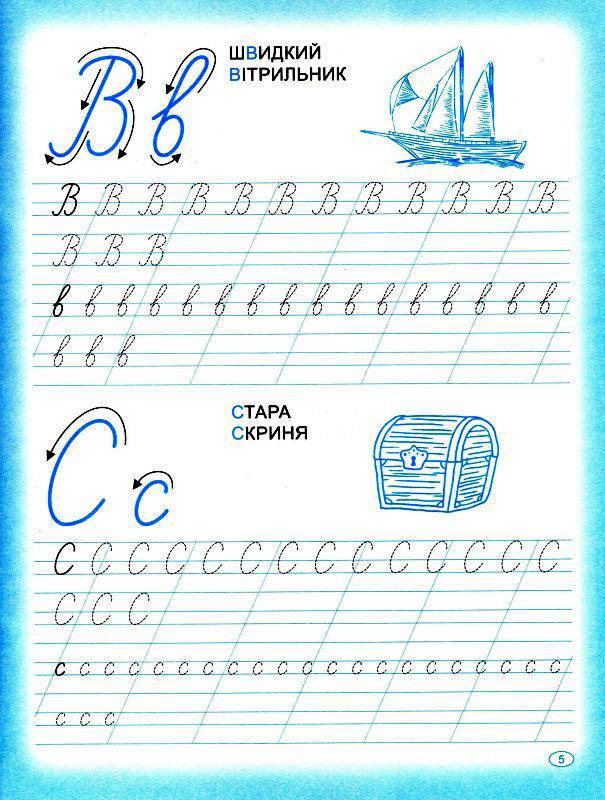

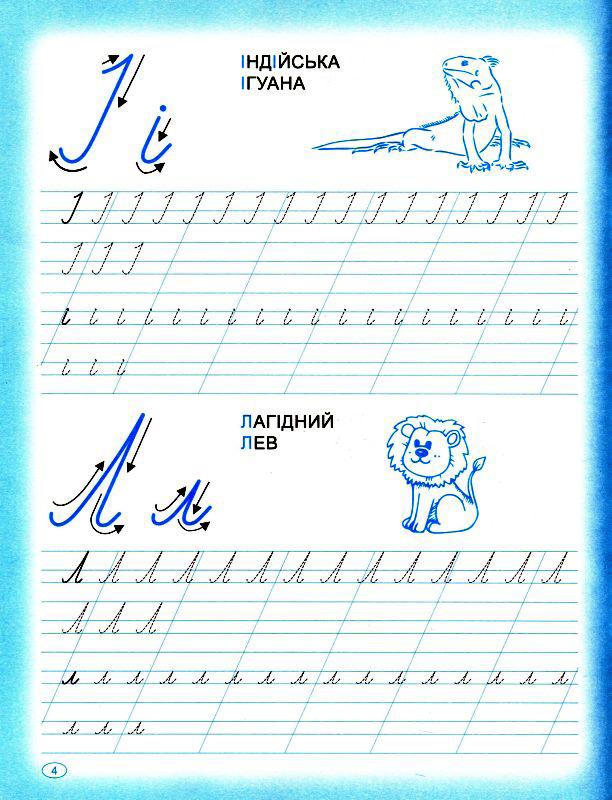

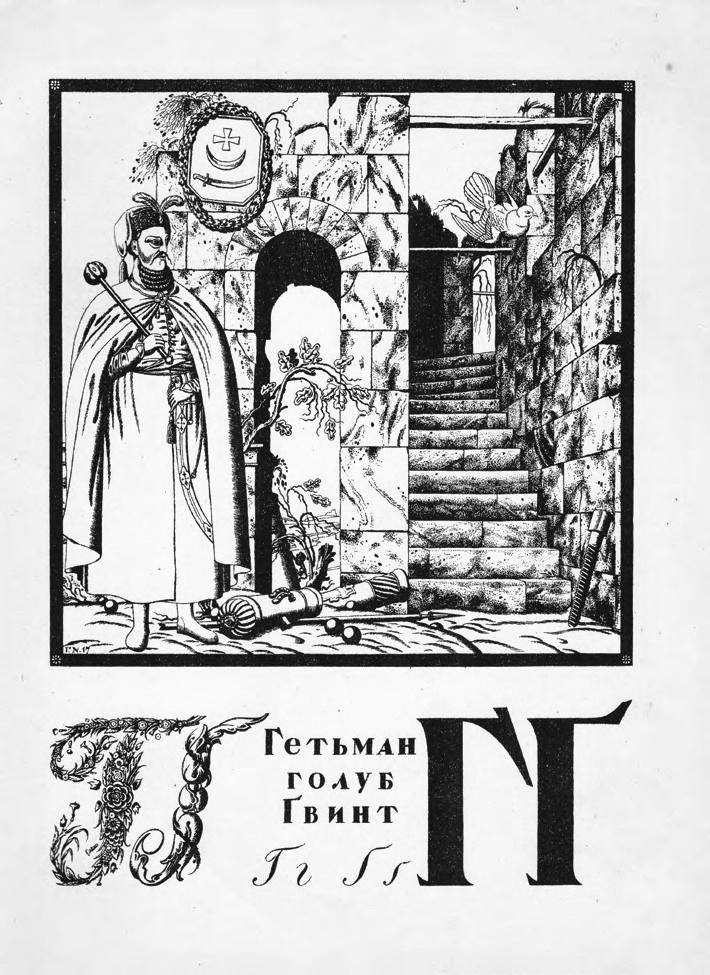

As a result, the Kharkiv Orthography was tossed aside in 1933, the Soviet authorities did not like it and announced that it allegedly aimed at the separation between two languages and even removed the special Ukrainian letter “Ґ” (Flier and Graziosi, 2018).

Oppression

4. The Krushelnytskyi family, the beginning of the 1930s. Sitting (from left to right): Volodymyra, Taras, Maria, Larisa and Antin. Standing: Ostap, Galya, Ivan, Natalya, Bohdan. In 1934-37 Volodymyra, Taras, Antin, Ostap, Ivan and Bohdan were repressed and executed.

10

5. Ukrainian Orthography, 1929.

11

6. Ukrainian Orthography, 1933.

The creation of orthography was a particularly crucial event in the history of the Ukrainian language. In fact, for the first time in Ukraine, a list of regulations was established, combining different traditions and rules. The spelling of the literary language was regulated, which for many years was influenced mainly by Polish and Russian (Svidomi and the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, 2022). It regularised the spelling of foreign words and names. The spelling was as close as possible to the living vernacular (Svidomi and the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, 2022). In the early 90s, there were suggestions to revive some regulations of The Kharkiv Orthography and only the “repressed” letter “Ґ”, which in 1933 was prohibited and even called nationalist, was returned to use (Svidomi and the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, 2022). More rules were revived in the latest edition of the Ukrainian orthography in 2019 (Svidomi and the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, 2022).

12

7. An illustration of the letters “Г” and “Ґ” by Heorhij Narbut for his Ukrainian Alphabet series, 1917-1919.

13

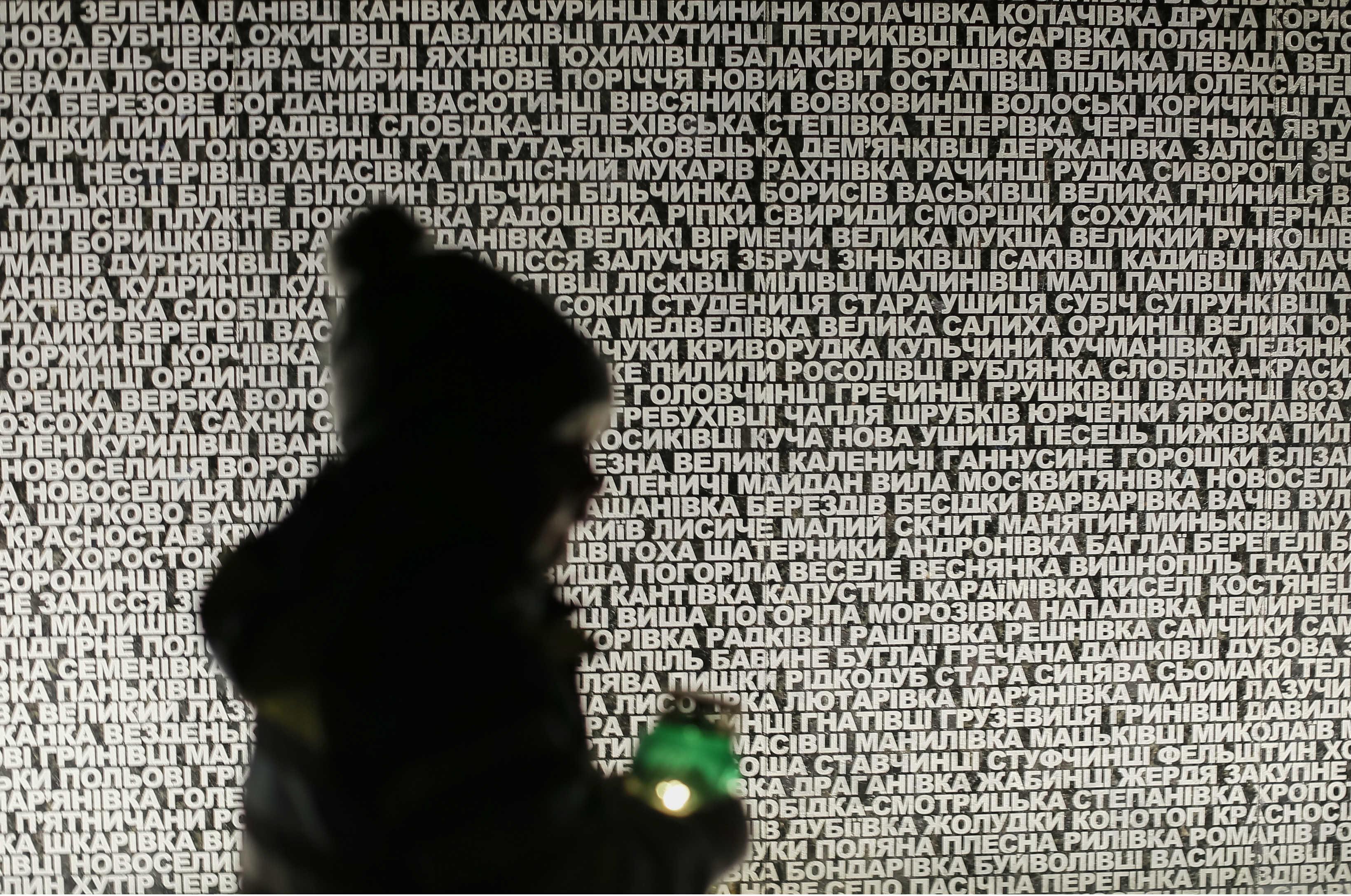

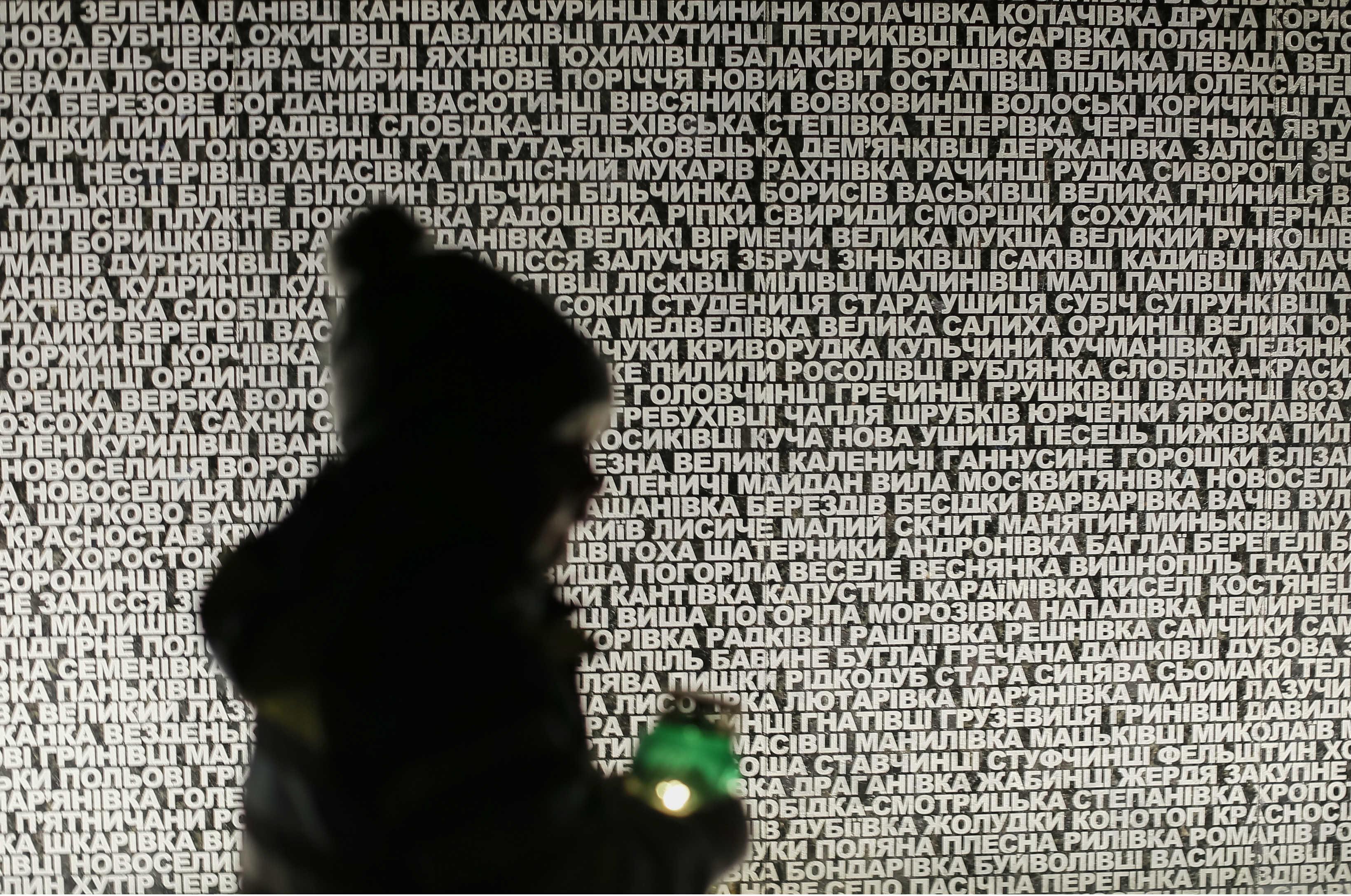

The biggest mass murder of Ukrainians organised by Stalin’s regime happened during 1932-33, to suppress the Ukrainian people and eliminate the resistance to the announced collectivisation of agriculture in 1929 (The National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, 2022). It is known as Holodomor, and countries worldwide recognised it as an act of genocide (The National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, 2022). Holodomor translates to death by hunger in Ukrainian. The unofficial death toll is over 7 million people and 3 million people in other regions of the USSR (The National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, 2022). After the Holodomor, the Soviet government relocated ethnic Russians to Ukrainian regions, to repopulate the land and assimilate the Russian language in Ukraine even more (Vovkanets, 2015). Therefore, Russian speakers heavily inhabited the East of Ukraine. That gave a solid foundation for language divisions among Ukrainians, especially in the East of Ukraine. This forced assimilation in some parts of Ukraine and the undermining of the Ukrainian language had a tremendous effect on the growth of Russian speaking population. The Ukrainian language was not perceived as a language and was always made fun of and considered amusing by Russia. Until recently for years Ukrainian was considered a ‘peasant’ language. Many Russian politicians still make fun of the Ukrainian language by mocking the pronunciation etc. Such an attitude shows a top-down view of the Ukrainian language and chauvinistic concepts of Russian imperialism.

14

15

8. A photograph of a child holding a candlelight next to the Holodomor memorial in Kyiv. In the background are all the towns affected by Holodomor.

linguistic afterthought

Ukrainian as a

I was a teenager when the Revolution of Dignity, also known as the Maidan Revolution, happened in Kyiv in 2013-14. The Maidan protests were against the pro-Russian ex-president Viktor Yanukovich and his desire to create stronger relations with Russia. The events that occurred have shifted people’s mentality about the role of language in their lives and how important it is. Ukrainians consider the Revolution of Dignity a huge turning point for the Ukrainian language revival. Many language-related laws were implemented over the past eight years. One of the most recent ones is the law about the usage of Ukrainian in the customer service and hospitality industry (Barkar, 2021). At that time I was working as a sales associate in a vintage store in Kyiv. I firsthand experienced the effects of the new law. I was pleasantly surprised at how many people were following it, but it was mainly the customers and not the employees.

Moving to the UK in 2015 to study and create connections with people from all around the world, made me realise how many misconceptions there are about the Ukrainian language and Ukraine as a whole. A lot of people perceive the Ukrainian language as a branch or a dialect of Russian. This is completely wrong and misleading and is the consequence of Russian centennial propaganda. Ukrainian language is far older than Russian and has more differences than similarities (Dalby, 2006).

afterthought

When Steve Kaufman, the co-founder of the digital learning service LingQ and a polyglot, visited Ukraine, he discovered that he needed to learn Ukrainian and not just Russian to fully immerse himself in the country’s culture (Pearce, 2022). He explained:

…

“There’s a tendency to treat Ukrainian or Ukraine as a sort of junior Russia, which it isn’t. It has a language of its own, a culture of its own, with a language well worth learning.” …

At the beginning of 2022, after the full-scale invasion by Russia, the number of users taking Ukrainian language courses on the app Duolingo grew by 577%, according to the company, with Ukrainian moving from the 33rd most popular language to the 13th most favoured on the app (Pearce, 2022).

17

Despite the outside similarity, they are two distinct languages that are only partially intelligible. Russians understand Ukrainian poorly, while Ukrainians are a lot better at understanding Russian. For example, it is a very common thing in Ukraine that you can go to the store and have a conversation in both languages, you can speak Russian to the store assistant and they will reply in Ukrainian or vice versa. However, it is very much changing due to the majority of people switching to Ukrainian exclusively. There are cases of young Ukrainian parents switching their primary language to Ukrainian so that their children will grow up as native Ukrainian speakers (Pearce, 2022).

The blatant invasion has only strengthened the Ukrainian language’s symbolic grip. In a way, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine made it matter more.

Language is a nation’s DNA. The language’s meaning is to be spoken. The more broadly the language is embraced, the more lived-in and rich it becomes. Barthes (1989, p.77) refers to it as ‘The Rustle of Language’. He says that the rustle is the noise of what is working well.

18

19

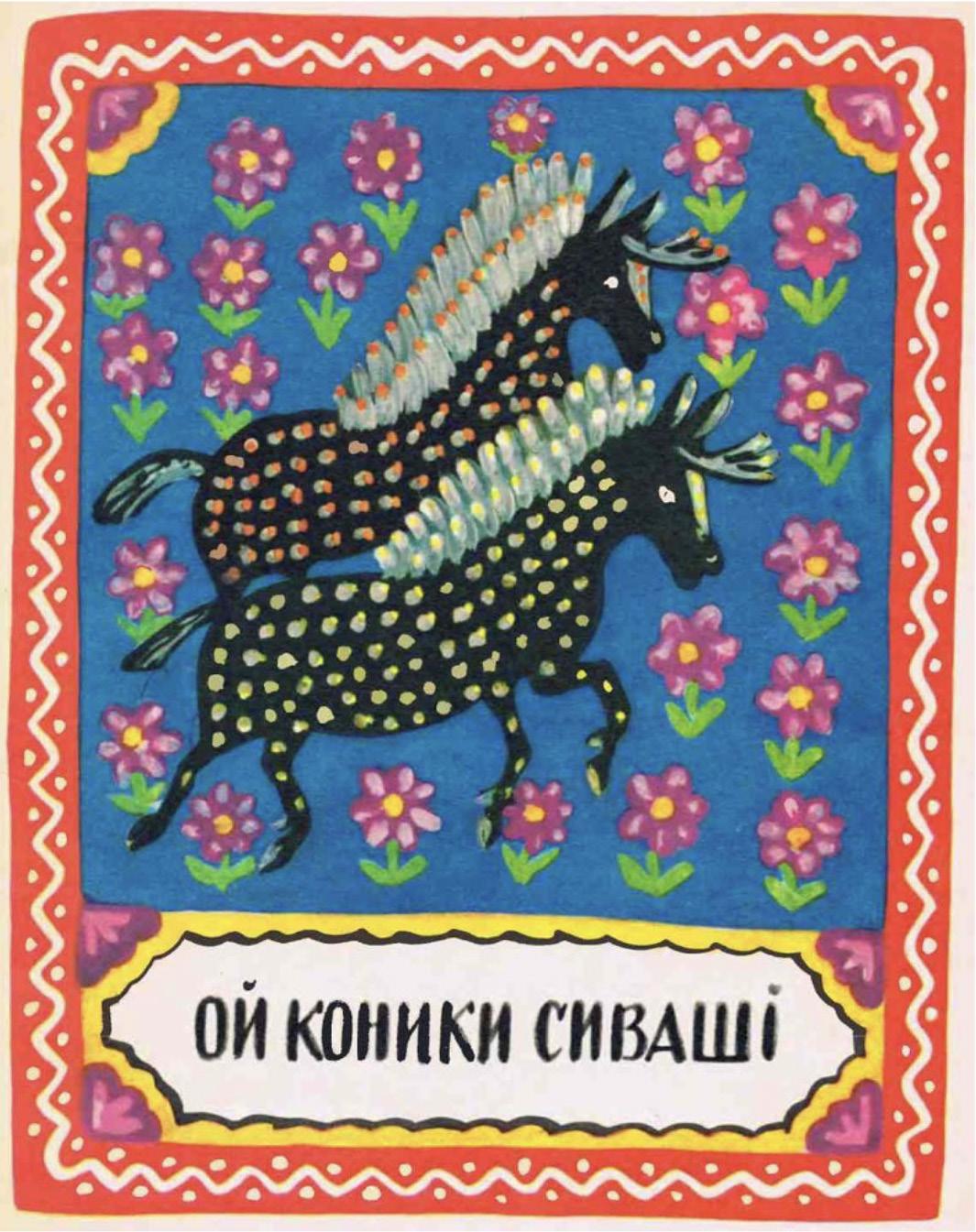

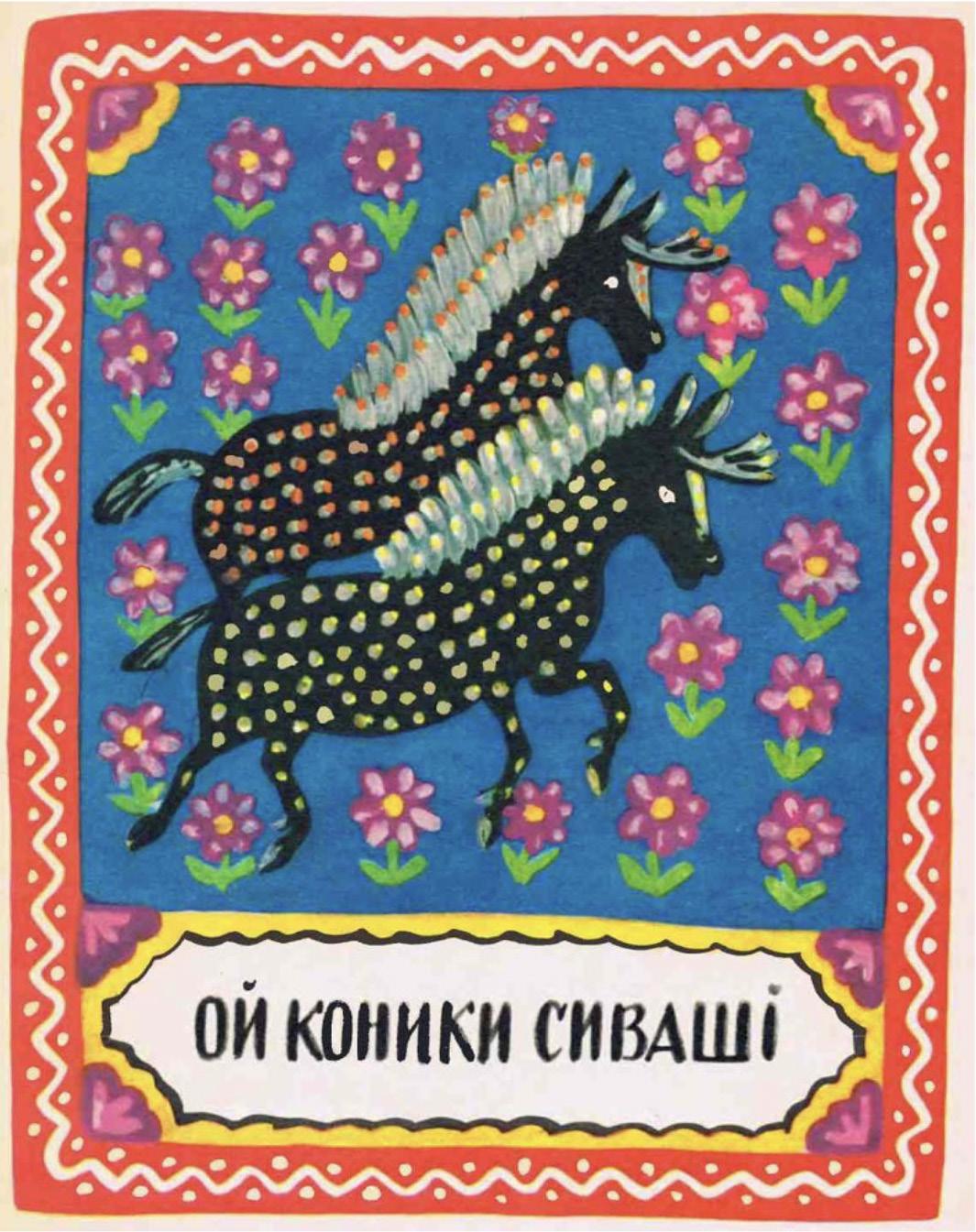

9. An illustration by Maria Prymachenko for a children’s book Veselka about Ukrainian folk songs, 1975.

…The Rustle of Language…

20

After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, there has been a new wave of the revival of Ukrainian culture and language, especially. The topics of unravelling Ukraine’s colonial past have been emerging more and more.

Coloniality is a term originated by Aníbal Quijano, a Peruvian sociologist who argues that coloniality resulted in a caste system (Quijano and Ennis, 2000). Those at the top are superior and those at the bottom are inferior due to their culture etc. 2022 is the year of total decoloniality for Ukraine. Professor Tlostanova explained the idea of decoloniality as a movement of disillusionment, a movement that realises it is not possible to do anything in political terms, but the way people think can be changed (Ukrainian Institute, 2022, 8:00). Meaning the decolonisation of the mind and aesthetics is as significant as the economic and political decolonisation. This means that the rejuvenation and preservation of the culture is a crucial part of removing the layers of the colonial past.

21

10.

This year a media phenomenon can be seen. Where people write Russian geographical names or names of Russian politicians in lowercase letters. This is a linguistic gesture of disrespect for the aggressor country. This way people are trying to get rid of and cope with all the atrocities that happen. The new spellings like "russia" and "russian federation" are now used by social media users on multiple outlets, and even by some mass media and news agencies like "Hromadske" and "Ukrainian Pravda" (Ukraїner, 2022) Also, Putin’s name is written in lowercase letters. The spelling of these words in lowercase letters is, of course, not regulated by the current Ukrainian orthography. Subjectively, such a decision is completely understandable, but in the long run, it may lead to confusion in the use of grammar and words.

A lot of Ukrainian universities initiated language clubs to support Russian-speaking Ukrainians who have decided to switch to Ukrainian (Ukraїner, 2022). Online learning platforms offered by public organizations are also available (Ukraїner, 2022). Such initiatives help to overcome the linguistic stigmatization of Ukrainians from the East, who communicated in only Russian due to the long colonisation by Russia and help them feel more confident switching to Ukrainian.

Decoloniality in post-Soviet countries is a quite an unknown topic to the people in the West. Unfortunately, Ukraine has been underrepresented in Eastern European and post-Soviet studies. Most Eastern European faculties are filled with Russian scholars and bearers of old Russian imperial narratives (Bochelnikova, 2022). There is also a massive budget that Russia spends on propaganda and disinformation campaigns to manipulate and twist the view of Ukraine’s language context (Bochelnikova, 2022).

22

23

Kiev or Kyiv?

11.

Often abroad, we come across Russian transliterations of Ukrainian cities, for example, Kiev instead of Kyiv. This is not surprising, because at that time Soviet regime promoted the Russian language for all foreign names in all republics (Project R.I.D., 2022). Ukraine was forcibly influenced by it and this spelling of Ukrainian geographical names took root.

With Russia's military aggression and with its constant attempts to undermine Ukrainian culture, the choice of writing with Ukrainian transliteration means you have an understanding of its importance. While researching, I found a comment on Instagram that quite made an impression on me. This person was saying that sometimes the translated names of geographical places lose their authenticity and we would have to change the names for the whole world. That just shows that some people are not aware of or do not understand the meaning of it in Ukraine.

Currently, Ukraine seeks to reclaim its identity, and language is an important part of this struggle. So spreading Ukrainian transliteration is a valuable way to resist the destruction of Ukrainian culture. Writing competently is our small contribution to the formation of the pro-Ukrainian image of Ukraine abroad.

25

Conclusion

The role of the Ukrainian language is complex and still changing. The Ukrainian language is in a place of resurrection and improvisation. Andriy Kurkov, a Ukrainian writer, predicts that the Russian language will be extinct in Ukraine in the future (Ukraїner, 2022). The usage of the Ukrainian language will be an element of national security. More bilingual Ukrainians are switching languages to oppose Russian interference. However, in the mentalities of many Westerners, the two languages are still blurred together. A lot of people still confuse Ukraine with Russia and for the world to take us seriously as an independent country, we need to change this perspective of how the world perceives us. What we are seeing right now is a birth of a modern nation.

26

Thousands of Ukrainians were killed for their beliefs, ideas and attempts at self-preservation. We as Ukrainians have to admit: the fact that our language has survived after so many bans and repressions is a gift and a great responsibility. The responsibility to admit that we have been deceived. They undermined our language and stole our pride. It is time to discover the truth and preserve it, because when, if not now?

27

Images:

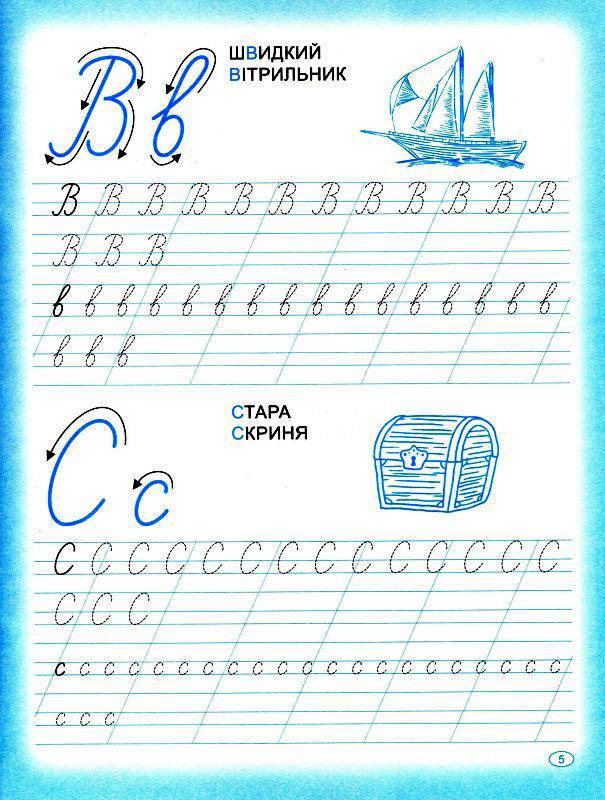

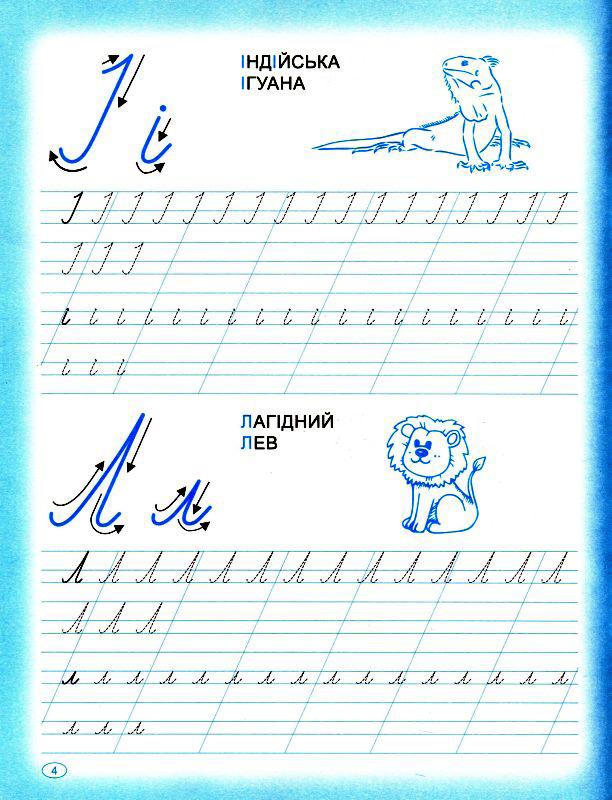

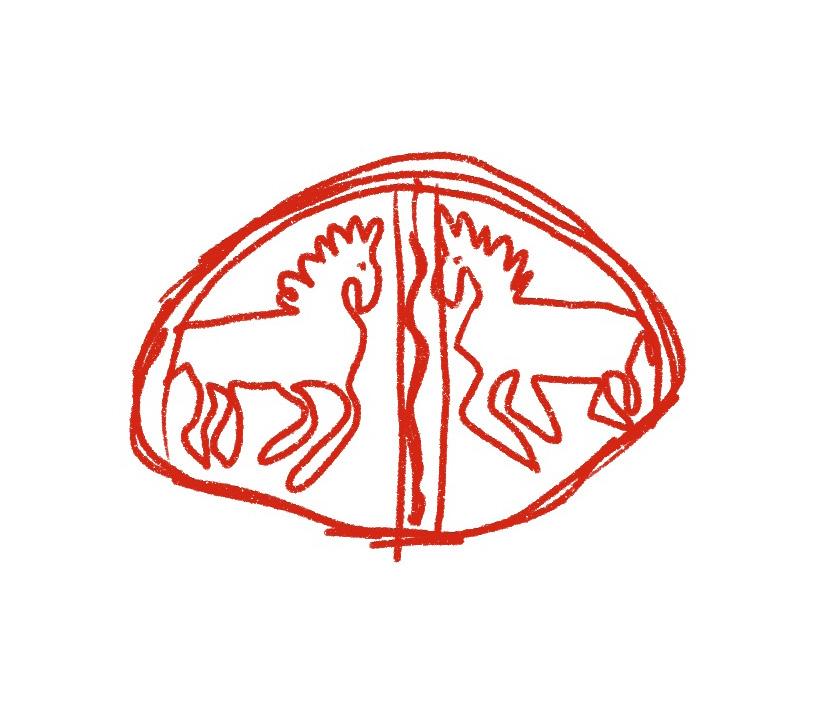

1. Fisina, A. 2021. Cursive Handwriting Book for Children in Primary school. Available at: https:// vsiknygy.com.ua/books/propisi_pishemo_propisni_literi_573317/ (Accessed: 14 December 2022).

2. Fisina, A. 2021. Cursive Handwriting Book for Children in Primary school. Available at: https:// vsiknygy.com.ua/books/propisi_pishemo_propisni_literi_573317/ (Accessed: 14 December 2022).

3. 2022. A school classroom in Kharkiv damaged by a rocket explosion.

4. 1930s. A photograph of The Krushelnytsky family, who were executed during the Stalinist regime. Available at: regime.https://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/Розстріляне_відродження#/media/ Файл:Krushelnycki.jpg (Accessed: 14 December 2022).

5. 1929. Ukrainian Orthography. Available at: https://zbruc.eu/node/69113 (Accessed: 13 December 2022).

6. 1933. Ukrainian Orthography. Available at: https://uahistory.com/topics/language_fun/2553/attachment/український-правопис-1933-1933_big (Accessed: 13 December 2022).

7. Narbut, H. 1917-1919. An illustration of the letters “Г” and “Ґ” by Heorhij Narbut for his Ukrainian Alphabet series. Available at: https://www.are.na/block/3497401(Accessed: 15 December 2022).

8. A photograph of a child holding a candlelight next to the Holodomor memorial in Kyiv. Available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/holodomor-remembrance-day-why-thepast-matters-for-the-future/ (Accessed: 15 December 2022).

9. Prymachenko, M. 1975. An illustration by Maria Prymachenko for a children’s book Veselka about Ukrainian folk songs. Available at: https://uartlib.org/allbooks/dityachi-knigi/oy-koniki-sivashi-ukrayinski-narodni-dityachi-pisenki/(Accessed: 15 December 2022).

10. @carpathiancult on Instagram. Personal collection of hand-coloured photographs of the Bilak family in Bukovets village. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CXBlgDSNQxq/ (Accessed: 6 December 2022).

11. An image of a road Kyiv sign. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0br687x (Accessed: 15 December 2022).

Videos:

Ukraїner (2022) Chomu varto perehodyty na ukrajinskyu? 3 September. Available at: https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=9253isyEjn4 (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

Ukrainian Institute (2022) Key-note by Madina Tlostanova. Decoloniality. 6 September. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=52Wvi9I5qjo (Accessed: December 15, 2022).

references

Books:

Barthes, R. (1989) The Rustle of Language. Translated by R. Howard. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. pp. 76-79

Loomba, A. (2007) “From Colonialism to Colonial Discourse,” in Colonialism/Postcolonialism. 2nd edn. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, pp. 35-37.

Dalby, A. (2006) “Ukrainian,” in Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. London: A&C Black, pp. 659–660.

Quijano A. and Ennis, M. (2000) Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. North Carolina, Durham: Duke University Press. Volume 1.

Instagram:

Svidomi, National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide (2022) ‘Kharkivskiy pravopys: yak odyn z uspihiv ukrajinizacii’ [Instagram]. 22 June. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/ CfHKfUatC6s/ (Accessed: 15 December 2022).

Project R.I.D. (2022) ‘Ukrainian Transliteration’ [Instagram]. 20 October. Available at: https:// www.instagram.com/p/Cj7wTWIj36Z/ (Accessed: 1 December 2022).

Bochelnikova, M. (2022) ‘A mini-guide to Ukrainian and Russian languages in Ukraine’ [Instagram]. 13 May. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CdgB8DON5NI/ (Accessed: 1 December)

Journals:

Flier, S M., Graziosi A. (2018) ‘The Battle for Ukrainian: A Comparative Perspective ‘, Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 35(1-4), pp. 11-30.

Blogs:

Vovkanets, V. (2015) Ukrainian and Russian: Two separate languages and Peoples. Ukrainian Institute of America. Available at: https://ukrainianinstitutenyc.wordpress.com/2015/08/28/ ukrainian-and-russian-two-separate-languages-and-peoples/#comments. (Accessed: 6 December 2022).

Websites:

National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide (2022). Holodomor history. Available at: https:// holodomormuseum.org.ua/en/the-history-of-the-holodomor/ (Accessed: December 15, 2022).

National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide (2022). Worldwide recognition of the Holodomor as genocide. Available at: https://holodomormuseum.org.ua/en/recognition-of-holodomor-as-genocide-in-the-world/ (Accessed: December 15, 2022).

Barkar, V. (2021) Zakon pro movu v 2021 rotsi. Vid 16 sichnya obsluhovuvanya ukrajinskoyu ta ispyty dlya chynovnikiv. Available at: https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/movny-zakon-sfera-obsluhovuvannia-derzhavna-mova/31044007.html (Accessed: December 15, 2022).

Pearce, M. (2022) For centuries, the Ukrainian language was overshadowed by its Russian cousin. That's changing. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2022-03-30/ la-ent-ukrainian-language (Accessed: December 6, 2022).

Sokolova, Y. (2022) 400 rokyv lingvocydu: yak Rosiya stolittyamy nyshchyla ukrajinsyku movu. Available at: https://fakty.com.ua/ua/ukraine/suspilstvo/20221109-400-rokiv-lingvoczydu-yak-rosiya-stolittyamy-nyshhyla-ukrayinsku-movu/ (Accessed: 6 December 2022).

Ukraїner (2022) Yak ukrajinska mova zminyuyetsya i zminyuye svit. Available at: https://ukrainer. net/mova-i-viyna/ (Accessed: 6 December 2022).

ї ґ