Filling the Strategy Gap: Strategic Art and the Elements of Strategic Design

Daniel H. McCauley6 May 2024

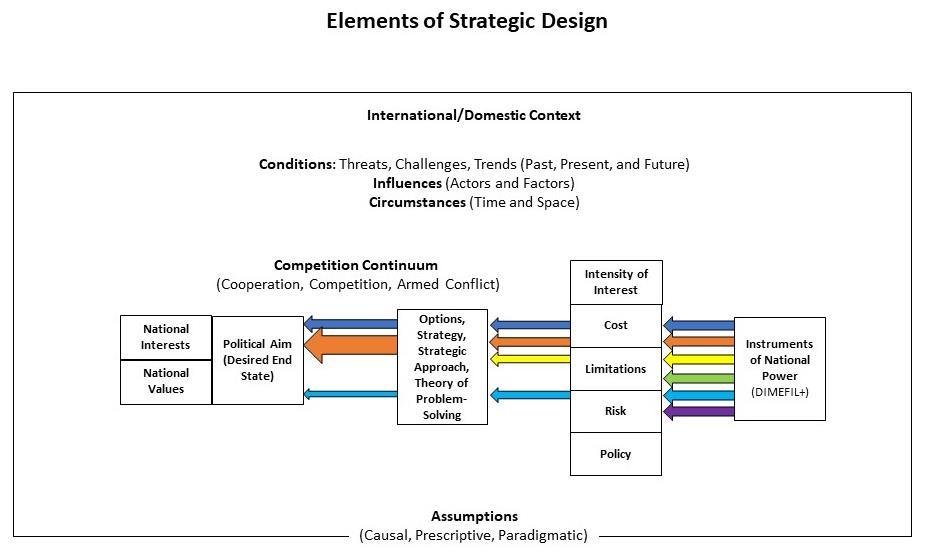

National strategic civilian and military leaders develop options, strategic approaches, and strategies to achieve national security objectives for the nation through the application of strategic art and design. The essence of strategic art and strategic design is both inductive and deductive. The conduct of strategic art and design requires strategic decisionmakers and practitioners to think analytically, logically, and conceptually to frame competing national security interests and objectives in a complex and uncertain international environment.

Strategic art is the cognitive approach used by senior civilian and military strategic decisionmakers supported by their expertise, experience, creativity, and intuition to develop policies, options, approaches, and strategies to organize and employ the nation’s instruments of national power that achieve or protect national security interests Strategic art relies on the strategic thinking skills of the strategic leader to accurately analyze the national security challenge and then identify the specific instrument of national power, or combination of instruments, that most effectively address the challenge.

Strategic thinking is a holistic method that leverages hindsight, insight, and foresight, and relies upon intuitive, visual, creative, conceptual, collaborative, and communicative processes to identify, analyze, and synthesize emerging patterns, issues, connections, and opportunities. The intellectual output of strategic thinking is strategic art, which influences and shapes the development of strategic options, approaches, and/or strategies.

Strategic design is the problem-solving analytical framework used in policymaking and option or strategy development The strategic design framework is necessary to conceptualize and communicate the strategic leader’s strategic thinking. Strategic design provides the necessary context that frames the depth and breadth of the challenge as well as the logic for the proposed approach to overcome the challenge Key components of effective strategic design include:

1. System-Centered Approach: Strategic design begins with a deep understanding of the international security system's: purpose; state, non-state, and individual actors; and the formal and informal rules for interaction. Further developing an understanding of individual strategic actor security needs, and how the international system facilitates or inhibits those needs, enable strategic leaders to develop more effective and longer-lasting solutions for all stakeholders

2. Holistic Perspective: Strategic design must account not only for the international security system surrounding a problem or opportunity, but requires an understanding of the interrelationship of economic, technological, social, political, environmental, and other relevant systems that contribute to or drive international security challenges. This holistic perspective helps ensure that solutions are focused on root causes and are more resilient and sustainable over time

3. Cross-Function Collaboration: Given the complexity of security challenges, strategic design necessarily involves collaboration across various governmental and non-governmental functions and organizations, such as government, industry, and academia Leveraging these diverse

experiences, expertise, and perspectives, strategic leaders can generate more innovative and effective solutions.

4. Iterative Process: As the international security environment is constantly in a state of change, strategic design is a necessarily iterative process that involves constantly refining solutions based on daily events and activities. This iterative approach allows strategic leaders to adapt to changing circumstances and to continuously refine their solutions or develop new ones as necessary

At its core, strategic design integrates traditional operational design methodologies within the strategic decision-making process. This methodology seeks to create a seamless intellectual alignment from the strategic level to the operational and tactical levels of government. Just as there is a need to create innovative solutions at the operational and tactical levels of war, strategic art and strategic design seeks to create effective, innovative, and sustainable solutions that not only meet immediate national security needs, but also provides a clear path to achieve or protect long-term national security interests and objectives.

There are sixteen elements of strategic design that provide a conceptual framework for the application of strategic art.

1. National Interests - Interests are qualities, principles, matters of self-preservation, and concepts that a nation or actor values and seeks to protect or achieve concerning other competitors. National interests refer to the goals, objectives, and priorities that a nation pursues to protect and promote its well-being, security, and prosperity. These interests typically encompass a wide range of political, economic, social, and security considerations, and they can vary depending on the specific circumstances, historical context, and priorities of each country. National interests are not static and can evolve over time in response to changes in the international environment, shifts in domestic priorities, and advancements in technology and ideology. Governments often formulate policies and strategies to advance their national interests and protect their sovereignty and security in a complex and interconnected world. Interests are contextual and may include the maintenance of physical security, economic prosperity, continuity of government and culture at home, and value projection in the geopolitical environment, as well as emotional triggers (fear, honor, glory), and other drivers (virtual, cognitive) that animate action. National interests are not a specific or achievable end state; rather they are aspirational and thus distinct from political aims, which are tangible conditions.

Some examples of national interests are:

Security and Defense: Protecting the territorial integrity of the nation from external threats, including military aggression, terrorism, and cyber-attacks. This often involves maintaining a strong military, forming alliances, and participating in collective defense agreements.

Economic Prosperity: Promoting economic growth, stability, and prosperity for the citizens of the country. This may involve fostering trade relationships, attracting foreign investment, ensuring access to key resources, and promoting innovation.

Energy Security: Ensuring a stable and reliable supply of energy resources, such as oil, natural gas, and electricity, to meet the needs of industry and households. This can

involve developing domestic energy sources, diversifying energy imports, and investing in renewable energy technologies.

Regional Stability: Promoting peace, stability, and cooperation within the country's region or neighborhood. This may involve resolving conflicts through diplomatic means, supporting regional organizations, and participating in peacekeeping missions.

Humanitarian Assistance: Providing aid and assistance to alleviate suffering and promote development in regions affected by natural disasters, conflict, poverty, or disease. This reflects a country's commitment to humanitarian values and may also serve its broader strategic interests by fostering stability and goodwill.

These examples illustrate the diverse range of interests that countries pursue to safeguard their security, prosperity, and values.

2. National Values – National values and national interests have a symbiotic relationship. Values are those beliefs that are held in the highest regard and guide perceptions, decisions, and structure actions. They help to determine principles, inform behaviors, set norms, and provide an impetus for how people view themselves and society. National values play a significant role in shaping a country's national interests, as they often inform the priorities, goals, and actions of a nation on the global stage. Examples of national values and how they can influence national interests are shown below:

Identity and Cultural Heritage: National values are often rooted in a country's history and cultural heritage. These values shape how a nation perceives itself and its place in the world. National interests may include preserving and promoting cultural traditions, language, and heritage.

Security and Sovereignty: National values related to security and sovereignty strongly influence national interests in safeguarding the country from external threats and maintaining territorial integrity. Protecting borders, ensuring national defense, and securing vital resources are often prioritized as core national interests.

Economic Prosperity: Values related to economic prosperity, such as entrepreneurship, innovation, and free market principles, can drive national interests in fostering economic growth, competitiveness, and prosperity. Pursuing trade agreements, attracting foreign investment, and promoting economic development domestically are examples of key national interests.

Human Rights and Democracy: Nations that prioritize human rights, democracy, and freedom often seek to promote these values as part of their national interests in the international environment. Supporting democratic governance, advocating for human rights, and promoting civil liberties are often central to a country's foreign policy approach

Environmental Sustainability: National values concerning environmental stewardship and sustainability can shape national. Pursuing international policies and agreements aimed at mitigating environmental degradation and promoting sustainable development may align with these values and national interests.

International Cooperation and Diplomacy: Values of cooperation, diplomacy, and multilateralism can drive national interests in fostering peaceful relations, resolving conflicts, and promoting global stability. Engaging in international organizations, participating in diplomatic initiatives, and building alliances may be key to advancing these interests.

Overall, national values provide a framework through which countries define their national interests and engage with the international community. By aligning policies and actions with these values, nations seek to advance their core interests while simultaneously upholding the principles and ideals that define them.

3. Conditions (Factors) – Conditions are those variables or factors of an operational environment or situation in which a unit, system, or individual is expected to operate and may affect performance. Conditions may also be the physical or behavioral state of a system that is required for the achievement of an objective. Conditions can change or be changed over time, and the rise, fall, emergence, convergence, and evanescence of these conditions over time form trends.

Conditions are also the outcomes of activities, events, or the cumulative or cascading effects over time. Conditions are similar to effects, but are more enduring over time and typically require the effects of several or many activities or interactions to change permanently.

Conditions are typically categorized as past, present, and future (probable, possible, plausible, and desired) Future conditions are generally categorized as: probable means the condition is more likely than not to occur; possible means it could happen but is not likely; plausible means it is possible but requires a number of other things to occur beforehand to occur; and desired means that those are conditions that are preferred, but may fall into one of the other three categories. Examples of conditions are: the proliferation of cheap advanced technologies, the effects of climate change, the initial application and use of artificial intelligence, the widespread use of drones or automated systems, etc.

The effects of specific conditions, groups of conditions, or circumstances (see below) can result in:

a. Trends: A trend is a prevailing tendency or inclination, and it has a statistically detectable change over time. Examples of trends are: increasing wealth disparity, increasing use of artificial intelligence, increasing use of deep fakes, the aging population of developed countries, etc.

b. Threats – A threat can be from a condition or trend or a state or a non-state actor with the capability and/or intent to cause harm. Examples of threats are global warming, nation-states, non-state actors, terrorist organizations, transnational criminal organizations, natural disasters, cyberattacks, etc.

c. Challenges – A challenge is simply a stimulating task or problem An example of a national security challenge are cybersecurity threats. Cybersecurity threats have become increasingly significant as nations, corporations, and individuals rely more heavily on digital networks for everyday functions. These threats include various forms of cyberattacks such as hacking, phishing, ransomware attacks, and espionage.

4. Circumstances – A circumstance is a condition, fact, or event accompanying, affecting, or determining an event or decision. The circumstances of a situation are defined by subordinate or accessory facts or details that provide the context as to how and why something did or did not occur. Circumstances are also the sum of environmental factors, such as an event or situation with respect to time, place, manner, or influencer, that accompanies, determines, or modifies a fact or event. In the national security context, opportunities are a favorable set of circumstances extant in the strategic environment that may allow for the advancement of one or more national interests.

5. Influences - Influences are the ability to cause an effect in direct, indirect, or intangible ways. An influence can be a human or non-human (such as a condition, trend, or circumstance) entity that has the power or capacity of causing an effect on interests, decision-making, and/or actions. Influence can be benign or manipulative, depending on the intention behind it and the means used. Understanding the mechanisms and effects of influence, such as persuasion or coercion, is crucial for navigating the diplomatic environment effectively. Influences typically fall into two broad categories:

a. Actors – nation-states, non-nations states, organizations, individuals and other entities that have the capability and capacity to affect the conditions or circumstances in some manner.

b. Factors – conditions, such as cultural norms or values, or circumstances, such as national elections, that have the capability to influence actors.

6. Political Aim/Purpose/Problem Framing Statement – The political aim is typically recategorized as the national-level objective. The political aim is the desired end state of a national security strategy or plan. The political aim defines the outcome that the strategic leader believes will preserve, protect, and/or advance the national interest(s) at stake. As the political aim is a distinct and achievable goal, it is best defined using nouns and adjectives for example, “a stable, secure Yemen.” The strategist must ensure that the overarching political aim the desired outcome preserves or advances a nation’s national interests. In this case, the underlying logic of the aim should explicitly discuss how an unstable and insecure Yemen is undermining its security. Likewise, a discussion of how a stable and secure Yemen will enhance or allow a nation to secure its national security interest must also be made.

Accurately defining the political aim is essentially defining and framing the problem. Problem framing is an opportunity to take a step back, assess the depth and breadth of the security challenge, break down its root causes, and then focus on potential solutions that are likely to lead to the desired outcome. Framing the problem is important because it sets the direction and scope of the strategic design process, ensuring that efforts are focused on addressing the core issues. Also, it helps avoid wasted time and resources on irrelevant or superficial solutions. Here are the key components of a good problem statement:

a. Description of the Problem: A clear and concise explanation of the problem. The description should be specific enough to give a clear picture of what's wrong, what needs improvement, and why.

b. Potential Consequences of the Problem: The statement must detail the potential consequences, good and bad, of the problem. This includes who is affected and how they

are affected. Identifying and describing the consequences helps to underscore the importance of solving the problem and can motivate stakeholders to engage in finding a solution.

c. Quantification: Whenever possible, use data to quantify the problem. This could be statistical evidence, costs, numbers of affected people, or any measurable aspect of the problem. Quantification adds credibility and urgency to the problem statement.

d. Contextual Background: Provide any necessary background information that helps to situate the problem within its broader context. This may include historical details, conditions that have led to the problem, past actions, or other relevant factors.

e. Specific Location and Time Frame: Clearly state where the problem occurs and the time frame it covers. This helps in understanding the scope of the problem and targeting the solutions appropriately.

f. Constraints and Restraints: Identify any specific constraints or restraints that must be considered in formulating a solution. These might include budgetary limitations, technological considerations, legal requirements, or environmental effects

g. Goals and Objectives: Define what a successful solution would accomplish and describe (using conditions) what the environment will look like upon mission termination For example, describing what a stable and secure Yemen looks like politically, economically, socially, educationally, financially, etc. is necessary to determine the depth, breadth, and potential costs of the effort.

h. Implications of Not Solving the Problem: To create buy-in and to provide a sense of urgency, describe what could happen if the problem is not addressed. These implications help to prioritize the problem-solving process, especially in resource-constrained environments.

7. Competition Continuum - Competition is a central characteristic of the international environment. While competition among like-minded actors can be keen at times, in cases where actors have incompatible aims, it can erupt into diplomatic, economic or military conflict. As the aim of a national security strategy or approach is to achieve strategic objectives by gaining or maintaining a position of competitive advantage, actors that lose a competitive edge will seek ways to undermine the approach. Given the range of national security issues, actors can be engaged in the international community in cooperation, competition, or armed conflict, or all three states of interaction simultaneously.

Understanding the strategic security environment and the nature of strategic competition requires strategic leaders to have a comprehensive understanding of the issues, key stakeholder intensity of interest, and the instruments of national power available to each. Therefore, understanding the competition continuum and where actors reside within that continuum relative to specific issues helps to shape the strategic leader’s approach, and associated risk mitigation efforts, as national interests are pursued.

International Context/Domestic Context – Context is the interrelated conditions, circumstances, and influences in which something exists or occurs. By analyzing the context in which a security problem exists, strategic decision-makers can develop effective options or strategies that pursue political aims that align with their national security objectives. Understanding the role of context in problem identification is critical: different competitive contexts require different approaches to the development of options or strategies Conditions,

circumstances, influences, and assumptions (see below) within the domestic and international environments form the contextual framework within which strategic decisionmakers operate.

The domestic context includes political matters (liberal, conservative, elections, type of government), the economy, employment, taxes, tribal factors, or other social needs norms and structures that influence the strategic decision-maker’s international considerations. The international context includes trade, currency exchange, governance and stability, international law, migration, resource management, geopolitical risks, and human rights among other factors.

8. Instruments of National Power – The instruments of national power are the means available to a government (or organization) in its pursuit of national objectives. Instruments of national power are usually expressed as diplomatic, economic, informational and military (DIME) or diplomatic, informational, military, economic, finance, intelligence, and law enforcement (DIMEFIL) Strategic leaders may also consider that any ministry or department is a potential instrument of national power from which it can draw on depending upon the specific issue. For example, a ministry focused on agriculture or tourism can be used as an instrument of national power. An example of this is that in the 2009 U S National Security Strategy, President Obama identified development, the American people, and the U.S. private sector as additional instruments of national power.

Instruments of power are derived from a nation’s elements of power. Elements of national power are the tangible and intangible factors from which the power of a state or nonstate actor is built and sustained. While there is no definitive list of the elements of power, they include: economic size and diversity, geographic size and topographical variance, type of governance, available human capital, industrial development, education of population, infrastructure, international reputation, national will, natural resources, and research and development/technology among others. To have enduring viable strategic options through robust or varied instruments of national power, states or actors must sustain, conserve, or build their elements of power or seek alliances and partnerships to mitigate shortfalls.

9. Intensity of Interest – Directly related to national interests, there are four levels of intensity that help to frame their pursuit or protection: survival, vital, major, and peripheral. Properly identifying the intensity of interest enables strategic decision-makers to frame the extent of the problem, to develop the depth and breadth of the response, to allocate the appropriate resources, to determine the immediacy of action and the time necessary to execute successful operations, and to garner domestic and international support for the potential activity as needed. The four levels of intensity of interest are:

a. Survival: A survival interest is one in which the very existence of the nation-state is in jeopardy as a result of military attack on its territory or from an imminent threat of attack. Under these circumstances, all instruments and elements of national power are used to take immediate action the expenditure of national treasure and significant loss of lives are expected.

b. Vital: A vital interest is one in which serious harm will likely result to the state unless strong measures, including the use of conventional military force, are employed to counter a hostile action by another actor or to deter it from a serious provocation. Under these circumstances, all instruments and elements of national power are considered, and there is an expectation of large expenditures of national treasure and loss of military and civilian lives.

c. Major: A major interest is one in which the political, economic, and ideological wellbeing of the state may be adversely affected by events and trends in the future and thus require corrective action to prevent them from becoming vital or survival threats. Economic, diplomatic, information, legal and other instruments of national power are typically used to shape the current and future security conditions that better support national interests over time. Some national treasure may be used in pursuit of these interests, but loss of life is not anticipated. Typically, the military instrument of power is not used or it is used in a supporting role to other governmental agencies, allies, or partners.

d. Peripheral: A peripheral interest is one in which the well-being of the state is not adversely affected by events, but the interests of private citizens, companies operating in foreign countries, or the health and welfare of the global citizenry are endangered. These are also known as humanitarian interests and are primarily addressed through the nonmilitary instruments of national power. The military instrument of power may be used but purely in a supporting capacity to fill gaps in civilian capacity or capability in timecritical situations, such as hurricane relief.

10. Costs – Costs are the losses you expect to incur if the option, strategy, or plan is implemented. Costs can include deaths, resources, expenses, penalties, prestige, or missed opportunities (known as opportunity costs) An opportunity-cost is the forgone benefit that would have been derived from an option other than the one that was chosen. To assess opportunity costs properly, the costs and benefits of each available every option, to include the option of not acting, must be considered against the others.

11. Limitations – A limitation is an action required or prohibited by higher authority, such as a constraint or a restraint, and other restrictions that limit the strategic leader’s or commander’s freedom of action, such as domestic considerations, diplomatic agreements, rules of engagement, political and economic conditions in affected countries, and host nation issues.

a. Constraints - In the context of strategy and planning, a constraint is a requirement placed on the leader or commander by a higher leader or commander that dictates an action, thus restricting freedom of action.

b. Restraints - In the context of planning, a restraint is a requirement placed on the leader or commander by a higher leader or commander that prohibits an action, thus restricting freedom of action.

12. Risk – Risk is the probability and consequence of an event causing harm to something valued. It is the loss or losses you expect to avoid, but may not if the strategy or plan does not go as

anticipated. Risk is generally discussed in terms of probability and potential consequence, and is classified within one of four risk levels: low, moderate, significant, or high. Military strategic risk is specific to the military instrument of national power, and is the probability and consequence of current and contingency events with direct military linkages upon the nation such as to the population, territory, civil society, institutional processes, critical infrastructure, and interests. Drivers of Risk are those factors that act either to increase or decrease the probability or consequence of risks arising from various sources Activities that reduce or eliminate risk must be part of the strategic discussion and included in the option, approach, strategy, or plan.

13. Policy – A policy is the stated or historical position of the government and the interests and values that the policy serves. Policy typically provides the desired end state, assumptions, available resources, and any limitations for option or strategy development Policy guidance may be quite general, as in a vision statement, or a more specific statement of guidance containing elements of specific ends, ways, and means. Whereas policy provides the foundation for strategy, it is informed or modified by the option or strategy development process or execution

14. Option, Strategy, or Theory of Action – An option is something that may be chosen, such as an alternative course of action using one or multiple instruments of national power. Options are derived from different scenarios and potentially distinguished by different assumptions, termination criteria, and/or objectives. Policy, and the values or interests and intensity underpinning it, provides the broad framework within which options are developed. The development of a range of options derived from the instruments of national power enable national security strategic decision-makers to engage in an iterative dialogue to select an approach that most effectively achieves national security objectives while reducing strategic risk.

Military options, for example, provide strategic decision-makers with flexible and responsive military ways with which to solve or assist in solving a problem. Military problem-solving options typically are presented in broad terms, such as missions and capabilities, along with resources required, time, and potential risk.

Once an option is selected, a strategy is developed to develop a coordinated effort. A strategy is a prudent idea or set of ideas for employing the instruments of national power in a synchronized and integrated fashion to achieve national security objectives. A strategy prioritizes objectives, sequences actions, and coordinates instruments of national power to ensure they are not working at cross-purposes and balance limited resources between instruments and objectives.

Central to both option and strategy development is the identification of the problem. A problem statement (see Political Aim) is the concise summation of why a strategic threat or opportunity requires action. A theory of action is derived from the problem statement and represents the logic of the proposed action(s) that achieves the strategic political aim or purpose with available means at acceptable levels of cost and risk. Examples of modes of actions are direct/indirect military action, unilateral/multilateral action, sequential/parallel economic and diplomatic action, strategic communication messaging, and covert or clandestine intelligence activities.

15. Assumptions – An assumption is a specific supposition of the strategic or operational environment that is assumed to be true and is essential for the continuation of strategy or plan development. They help define perceived threats to one’s own interests and the cause-and-effect

of potential actions. For an assumption to be accepted as truth, it must be recognized as an assumption and an internal logic must exist to provide a foundation and broad acceptance.

In addition to filling knowledge gaps, assumptions are beliefs of the world and one’s place in it. They represent general beliefs about one’s self, the environment, and other actors. Assumptions allow a nation to envision how the international environment may respond to its actions.

a. When developing options and strategies, there are three broad categories of assumptions to consider:

i. Paradigmatic assumptions are structuring mechanisms used to order the world into fundamental and objectively valid perceptions of reality. These types of assumptions are rarely examined critically as they are unconscious perceptions of the individual’s social world and what society has deemed important and valuable. These are sometimes called critical assumptions, which are used to distinguish between one theory or worldview from another. An example of a paradigmatic assumption is whether one ascribes to a realism, idealism, or constructivism viewpoint in international relations theory.

ii. Prescriptive assumptions are what we think should happen in a general situation. Grounded in our paradigmatic assumption, prescriptive assumptions surface as one thinks about how someone should behave, what a good process should look like, and what obligations people have to each other. Prescriptive assumptions are based upon past problem solving and the actions that “worked” in those circumstances. Prescriptive assumptions allow for quick decision-making and responses, and are generally accurate. As the prescriptive assumption is applied to a specific situation, however, the specific circumstances render the prescriptive assumption less accurate. An example of a prescriptive assumption is if a counterinsurgency was successfully conducted in Malaysia in 1957, similar actions or activities would work in Afghanistan in 2024. Whereas a counterinsurgency approach is a likely effective theory of action, the specific circumstances in Malaysia in 1957 and Afghanistan in 2024 are entirely different, which therefore require a wholly different approach or strategy based upon the specific domestic and international environmental factors and actors

iii. Causal assumptions, along with prescriptive assumptions, are the most familiar to military planners. These assumptions are based upon previously presumed cause-andeffect outcomes, and are usually stated in predictive terms. Causal assumptions are far more accurate when evaluating relatively simple systems, such as a surface-to-air missile system, but become less accurate when trying to evaluate complex adaptive systems, such as human actions and decision-making. An example of a causal assumption is that if one bombs a command and control bunker with a certain weapon within certain parameters, and it stops communicating, then if one does the same thing in the future to another command and control bunker the same result will occur. This causal assumption and action can likely be repeated until the system is changed or replaced. In the human domain, or with complex adaptive systems, past actions and outcomes are far less deterministic.

*The linkage of the strategic design elements generally follows the discussion above; however, there is an iterative aspect in that each element informs the other elements.