The Oceanic Envir onment

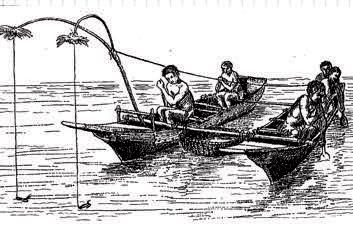

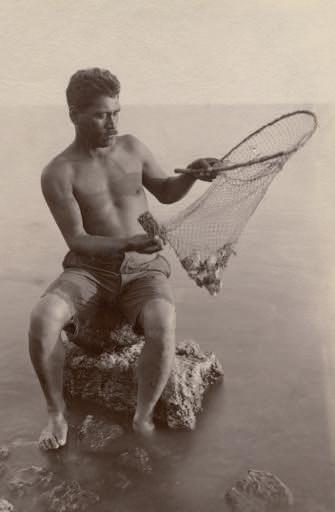

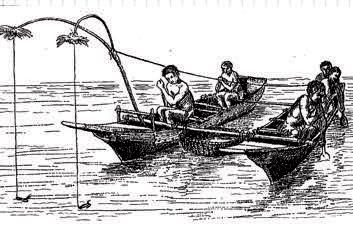

Enor mous expanses of ocean dotted with thousands of islands of var ying size are the hallmarks of the g eog raphy of Oceania T he different marine environments that sur round them provide a means to most of the islanders to satisfy a larg e por tion of their nutritional needs Fishing plays an especially vital role on coral atolls, where women and children g ather bottom dwelling species on beaches and from reefs, also sometimes using cast nets (*1) and hand nets (*2) to catch small fish, while men take to the open seas in boats, and use various techniques to catch larg er species.

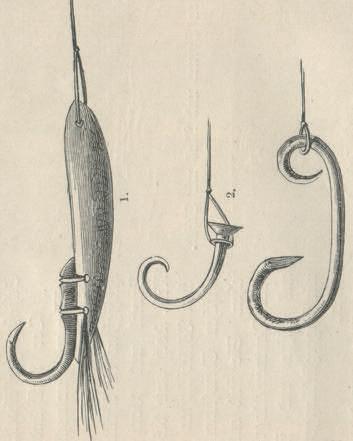

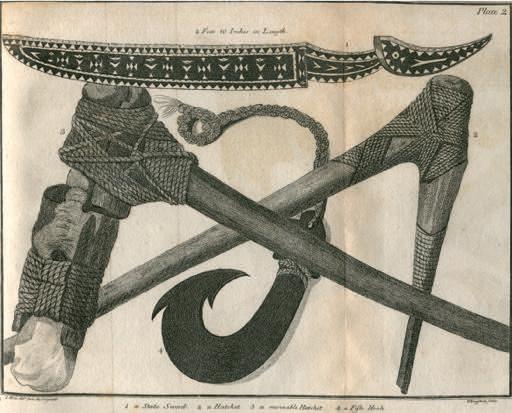

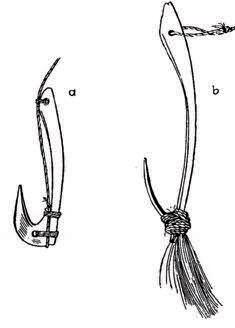

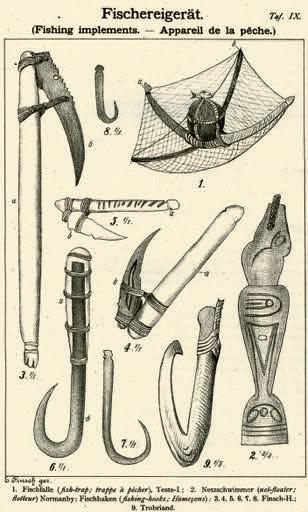

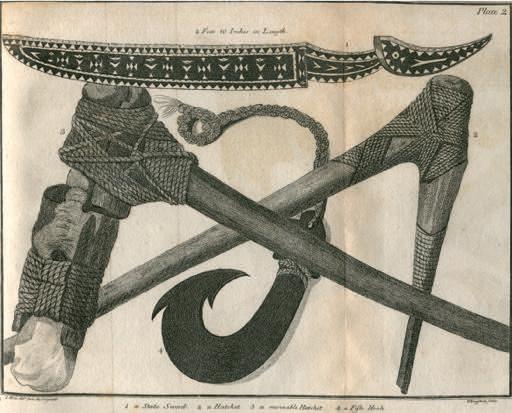

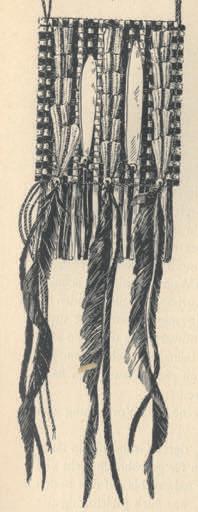

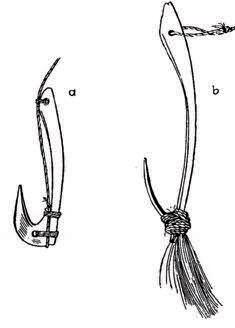

T he highly developed and ver y varied methods used for catching fish include the following tools and techniques: hooks, nets, traps, wicker basket traps, weirs, nooses, shark nooses with rattles, anesthetization with herbal poisons, spears, ar rows, har poons and kite fishing (*3) (202): Pl 2

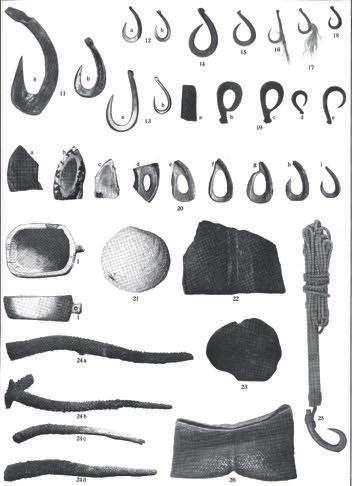

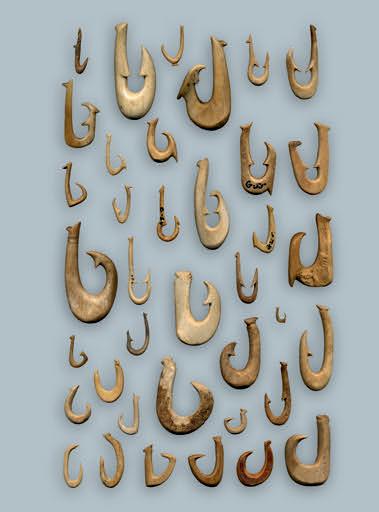

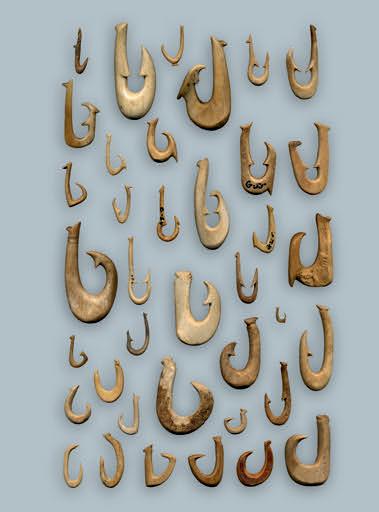

T his publication deals exclusively with hook fishing, which is widespread throughout all of Oceania No other area on ear th comes close to having so many different kinds of hooks. T here are countless variants and types. Tiny hooks, a few millimeters in size, are known from Hawaii, the Solomon Islands and excavations in the Marquesas Islands while some wooden types can reach a massive 50 centimeters in size Some hooks are relatively simple, while others are ver y complex and ing eniously designed, and made from a wide variety of materials T hese materials include plant fibers, seashell, snail shell, bone, tur tle shell, wood, teeth and rarely stone, thor ns and crab pincers T he result is an almost unbelievable number of hook types. In some cases, only one type of hook is known in a par ticular area, but more often, a given cultural area makes use of many different kinds

T he g eog raphic division of Oceania into Australia, Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia cor responds in some measure to the anthropological and cultural differences between these larg e areas, but the boundaries between them remain f luid because, with the exce ption of the Australians, Oceanic peoples had highly developed nautical and navig ational skills, and succeeded in reaching even the remotest island g roups We never theless decided to use this division which is traditional to ethnog raphical literature and most conveniently understood

19

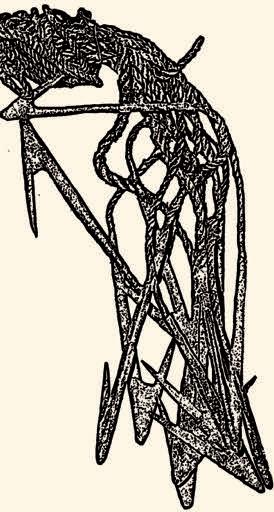

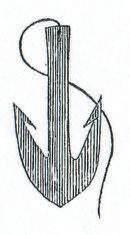

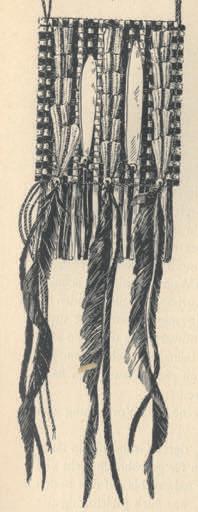

(*3) Fishing Kite from the Solomon Islands made of leafs, wooden sticks, string and a bunch of spider web fibers as bait for the Flying Fish

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 19

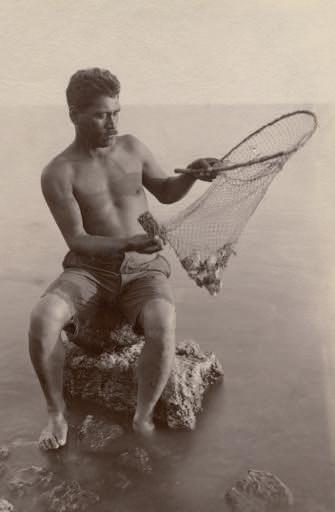

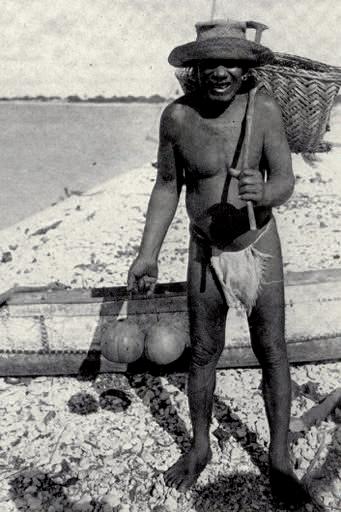

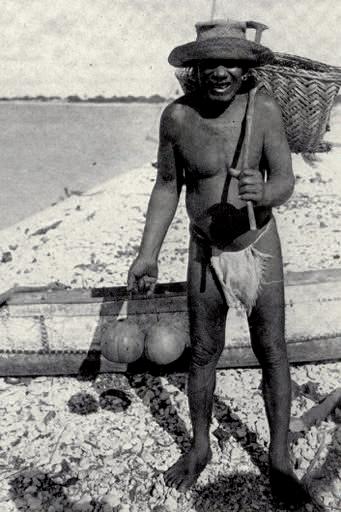

(*2) Fisher man catching shrimp in Hawaii Photo by Davey, c 1880

20 aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 20

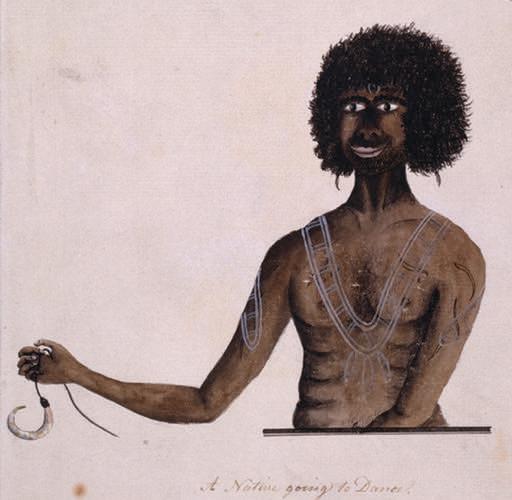

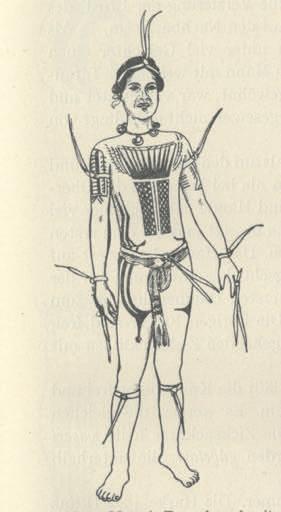

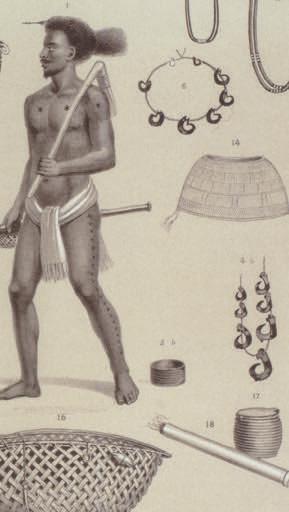

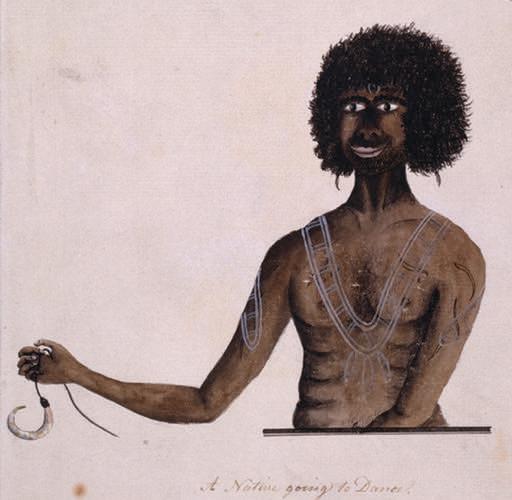

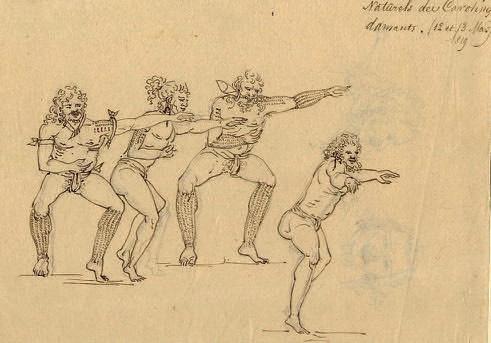

(*1) “A Native g oing to Dance - A Native of New South Wales, or namented after the manner of the Countr y, ” Drawing 55 by the Por t Jackson Painter, 1788-1797, from the Wattling collection now in the Natural Histor y Museum Picture Librar y, London

Australia

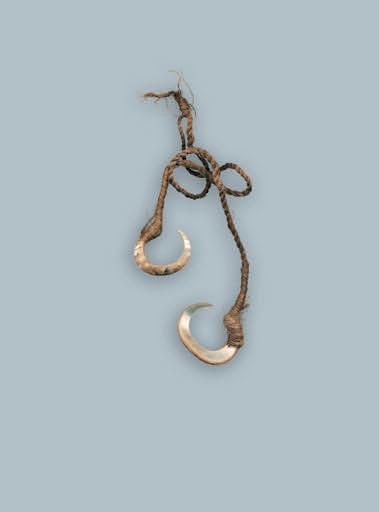

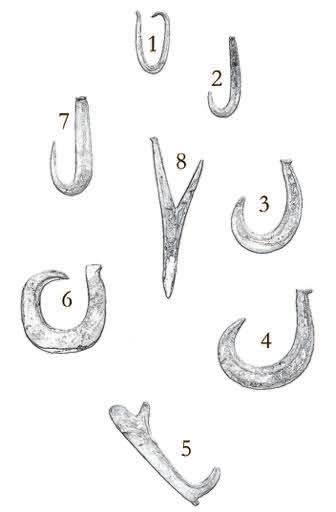

Australian hooks are seldom seen in the literature or in collections Already in 1878, Brough-Smyth illustrates several types and describes their use (50): 391, Fig. 226-229.

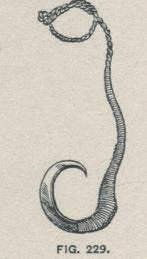

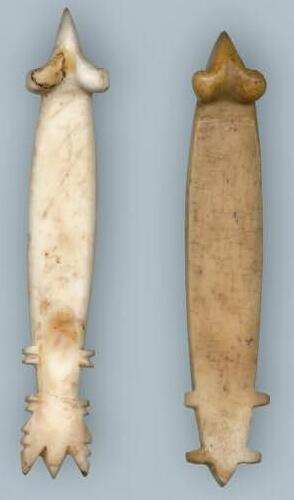

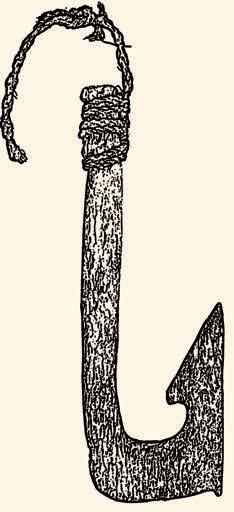

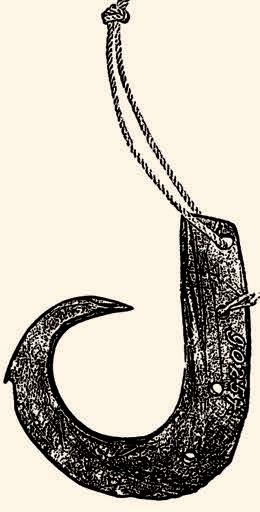

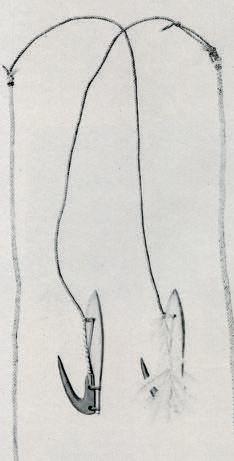

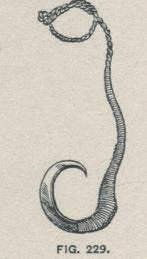

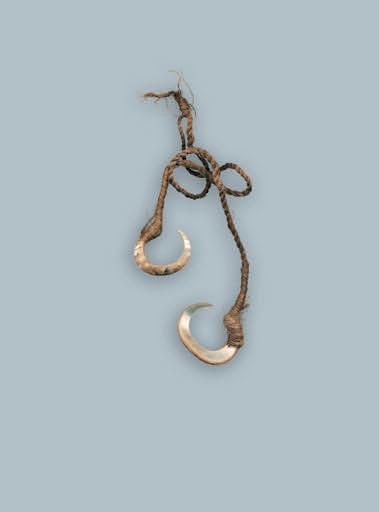

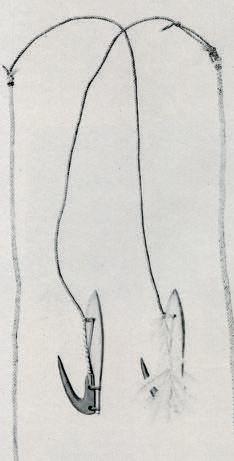

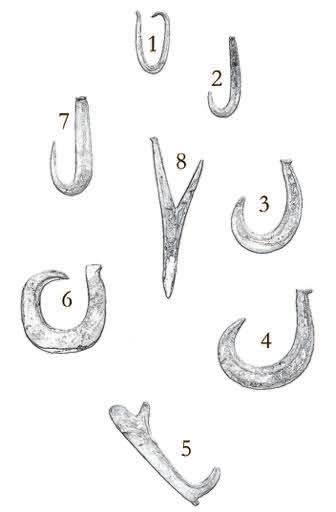

He shows a hook from Rockingham Bay in Queensland, ver y similar to the two illustrated here (plate one) and states: “T he material used is a section of the shell of a species of haliotis (in fact it is Turbo ninella torquata, Gmelin 1791, as has been kindly pointed out by Yosi Sinoto) It is beautiful in shape, highly polished, and has a ver y shar p point. It is securely and neatly attached to the cord with twine made of the fibre of some plant T his is in all respects a most excellent hook ( ) and might be used now, I have no doubt, with success, in taking larg e fish.” (*1), (50): Fig. 229. “Another kind of fish hook – made of tur tle shell – is also in use at Rockingham Bay In for m it is exactly that figured above ” BroughSmyth also illustrates a ver y similar hook made of bone (50): Fig 226 T his old type of hook had already become scarce in Victoria by 1878, having been larg ely re placed by European hooks

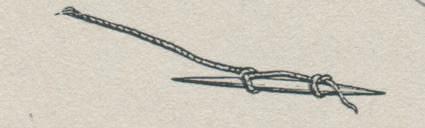

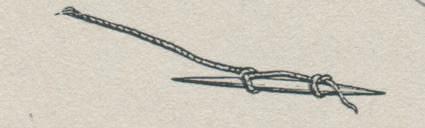

Brough-Smyth illustrates a small wooden stick, pointed on both ends, that might also have been made of bone (*2). An ing enious knot ensured that the stick would not slip from the line “It was baited, however, and when seized by the fish and the line strained, the bone stuck in the jaws, and the prey was secured T his is a ver y simple but a ver y ing enious contrivance for taking fish ” (50): 391

Another unusual type of double hook was used in Queensland (*3) It consists of a single piece of hardwood, pointed on both ends, and fur ther equipped with two points tur ned inwards (50): 391 T his double-ended wood or bone hook is not only the oldest known type of Australian Aboriginal hook, but is possibly the archetype and original for m of the fish hook altog ether.

A ver y rare type of hook shown on plate two could only be compared to one similar reference example in the literature Lewis illustrates this hook type, which was collected in the 19th centur y by the Spencer-Gillen expedition at the Daly River in the Nor ther n Ter ritor y (51): Fig 166

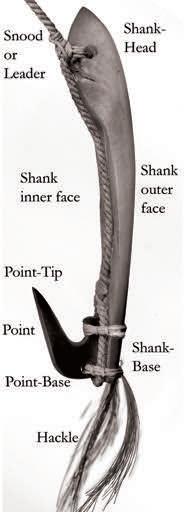

T he hook and its rod illustrated on the following plate were collected on the Cape York Peninsula in Nor th Queensland. A bone point is tied to a simple wooden shank with tree bast Some traces of gum are still visible T he hook is attached with a plant fiber line to a simple wooden fishing rod

To underline the significance of Australian hooks, we once ag ain quote Brough-Smyth: “How it happens that their fish hooks are so well made, that their lines, if not always neatly twisted, are as g ood as ours ( ) may induce new speculations in the minds of those who believe that the Australian is poor in invention ” (50): 289

21

(*2) (*1) (*3)

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 21

(*) Francois Peron, Voyag e de Decouver tes aux Ter res Australes, Paris, 1824, Atlas, Pl XXII, Fish hooks of mother of pearl shell from NewHolland, drawn by C A Lesseur

Pl 1 Pl. 2 Pl 3

Australia 22 1 aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 22

23 aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 23

Australia 24 2 aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 24

25 aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 25

Australia 26 3 aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 26

27 aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 27

28

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 28

(*) Fish traps (wup na tatakia) on the Gazelle peninsula, (23): 80/81, Pl 6

Melanesia

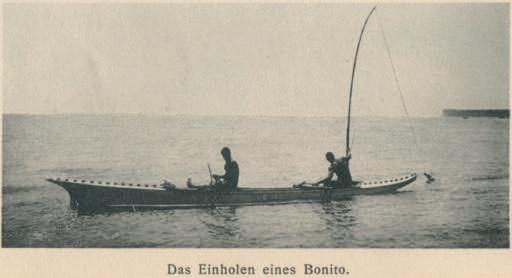

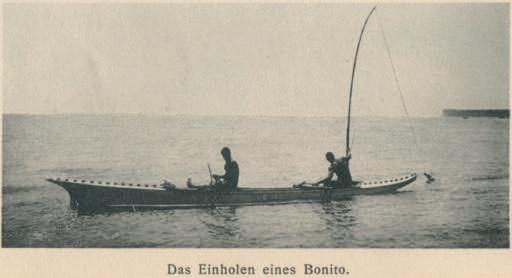

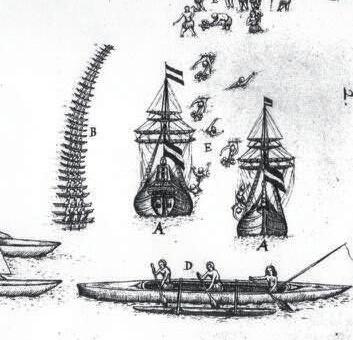

It is sur prising that in this hug e area, there appear to be larg e regions where no evidence sug g esting that fishing with hooks existed T his is especially tr ue of larg e par ts of the coastal regions of New Guinea. Why it is that the typical two-piece hook for m was widely adopted and used only in the Huon Gulf, while for the Nor thwest Coast all the way to Geelvink Bay there are in the literature only a few and vague references to hooks, without illustrations, is a question that future research and archaeological work might be able to shed some light on. T he hooks illustrated on the plates 4 and 5 show all the variants of two-piece fish hooks, whose shank may be made of bone or Tridacna shell Mother of pearl was not used T he upper ends of the shanks are either g rooved or lightly crenellated to help secure the fiber snood that is tied around them While not exclusively intended for use as bonito hooks, it can be assumed that bonito were caught with them Finsch remarks: “T hese hooks were not used for fishing in the strictest sense of the word, an activity unknown to Papuans, but rather were used like hooks used for catching mackerel, that is to say they were attached to a line which was drag g ed behind a fast sailing canoe. (...) I have obser ved fish hooks of this type being used from the Huon Gulf to Friedrich-Wilhelm-Hafen (Madang) on many occasions I saw none west of there, but suspect they do occur there ”

(15): 191

(*1) Finsch’s obser vations on the use of these hooks in the regions he describes are accurate, but as sur prising as it may seem, his guess that their use extended westward was incor rect. T he coastal inhabitants whom Finsch described and who used bonito hooks, were devoted fisher men, as the many re presentations of fish on their boats, their houses, and their bowls sug g est

A masterfully manufactured fish, also beautifully painted, collected at Astrolabe Bay by Krämer, and made from palm bast, a ver y difficult material to work, is illustrated in (*2), (37): Ill 69

Siassi Islands, South of the Lar ger Island of Umboi

T hese tur tle shell hooks often show clear signs of having been heated at the points in order to facilitate bending them T he shank is lashed to a second piece, made of bone, mother of pearl, or Tridacna shell

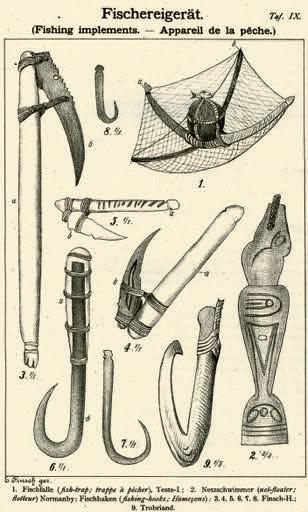

T he first illustration of this type of hook can be found in: “Ethnologischer Atlas” by O Finsch, (*3) without a description of how it was used T hat two-piece hooks can display ver y ar tful workmanship is demonstrated by the example seen at bottom left of the plate, and by a ver y unusual example illustrated by Bodrogi (38): Fig 187 Here the hook appears to re present a hor nbill It compares to the Huon Gulf hooks on the previous plates. T he bone and tur tle shell points bound on to those hooks can indeed also be seen as re presentations of bird heads In addition to these types, there are also simpler examples, made of single pieces of tur tle shell, bent by heating.

29

Pl 4

Pl. 5

Pl. 6

(*2)

(*3) Ethnologischer Atlas, Leipzig 1888: Pl IX,6

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 29

(*1) Bodrogi refers to Biro and states: “Biro repor ts that in the Huon Gulf area fish hooks are made only on the Tami Islands and Tamigidu ” (38): p 129

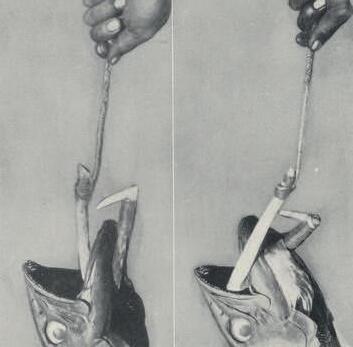

A type of two-piece hook made from palm wood is known from the extreme southeaster n tip of New Guinea and the Massim area. T he carefully made binding covers the entire shank and the snood is tied on ver y precisely Schlesier mentions a similar hook with a f loat He states that its name is Yahuana, and gives the following description: “T he method of use for this hook is especially conceived for the capture of the Mwalaw e fish T he line is unwound and thrown into the sea T he f loat stays on the surface, and the hook sinks beneath it A bait fish is attached to the end of the line where it meets the hook and to the top of the hook itself with its head pointing upwards When the Mwalaw e fish bites, a rod about a meter in length that is placed in the bait fish’s mouth and reaches to the water’s surface, is set into motion, thus indicating that the bait has been taken ” (39): 65 Other types of hooks are known from the Massim area, which Beasley describes and illustrates in several pag es of his publication. (8): 78-82.

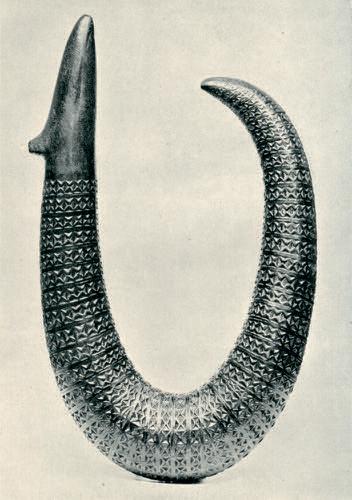

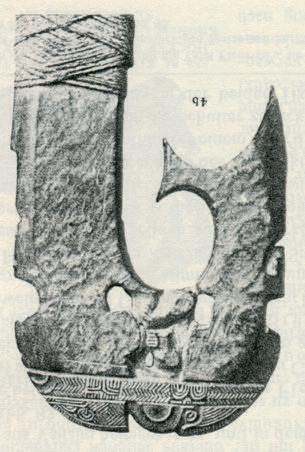

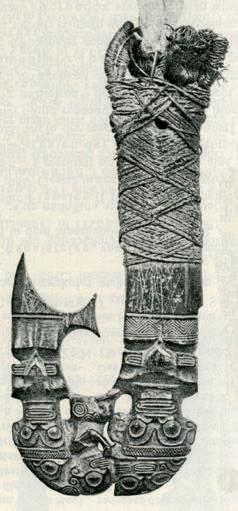

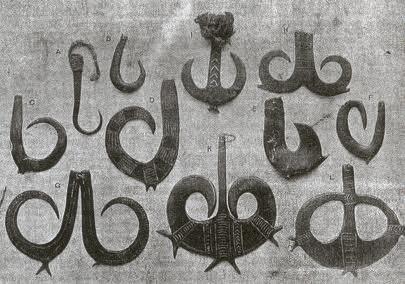

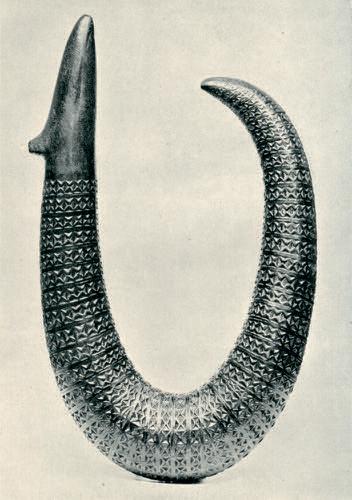

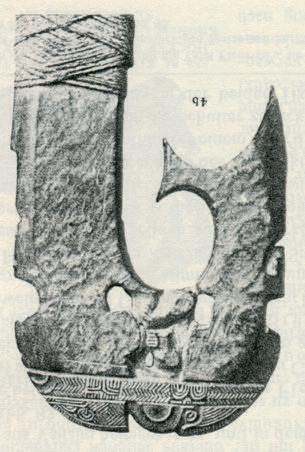

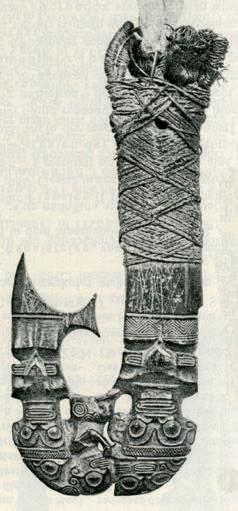

The Most Beautifully For med Melanesian Shark Hook fr om the Tr obriand Archipelago

T here is undoubtedly no region in Oceania where there is a g reater variety of for ms of shark hooks than in the Trobriand Archipelag o Two types are especially notewor thy: First, a larg e wooden V-shaped hook with a relatively undeveloped point, which Edg e –Par tington illustrates (3): Series 3, Pl LXXVIII

Its 54 cm length probably makes it the larg est hook in Oceania Beasley also illustrates this hook, and another as well (8): Pl CXXIII and CXXIV He remarks:

“T he snood loop ( ) is composed of numerous strips of rattan cane, bound tog ether with the same material and strengthened with wooden wedg es. ” (8): 81.

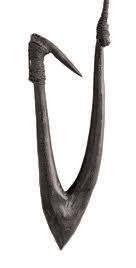

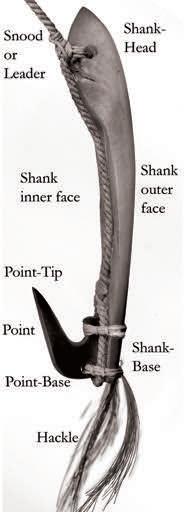

T here is another example of these impressive shark hooks in the Berlin Museum of Ethnolog y Beasley shows three hooks, each with a distinctively stylized head at the end of its shank. T he head’s offset chin ser ves to secure the line to the hook. T he shark hook illustrated here (*1) substantially sur passes those shown by Beasley both in ter ms of for m and workmanship A crenellated ridg e r uns down from beneath the stylized head along the outside of the hook. T he ridg e is meticulously car ved into the heavy wood and adds to the wonderful swee ping sculptural movement of the piece T he hook is an example which testifies not only to its creator’s highly developed sense of for m, but also to his uner ring comprehension of the materials he used T he fiber binding which attaches the tip to the point is fur ther evidence of this fact T he hook was collected on the island of Kiriwina in 1904. It shows signs of use, and it is consequently likely that it was manufactured at some time in the late 19th centur y (*2) T here are two other shark hooks of hard and heavy wood from the Lawland Islands, now in the Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde in Munich, which measure 37 5 (*3) and 43 cm (*4) respectively, and which are probably the oldest hooks still in existence from the Massim region T hey display countless bite marks and are quite different in for m from other known types of hooks One of them is unique in the way the head of the shank is designed Both hooks were collected in 1885 by Max T hiel, and, on account of the extensive evidence of use they display, may be safely assumed to date from the early 19th centur y or even earlier (Inv #B1700 and B1701)

30

Pl 7

Pl 8

(*1)

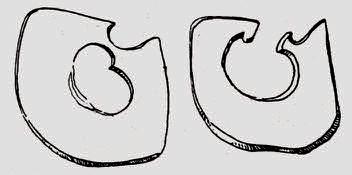

(*) Tur tle shell or naments, Sabar gorar, wor n in Tor res Straits, from specimens in the British Museum; photog raphed by Mr H Oldland In: (41): fig 12, p 33

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 30

(*2) First published in: Meyer, Anthony JP : Le Pays Massim-Papua Nouvelle Guinee Catalogue d'exposition Galerie Meyer, Paris 1987

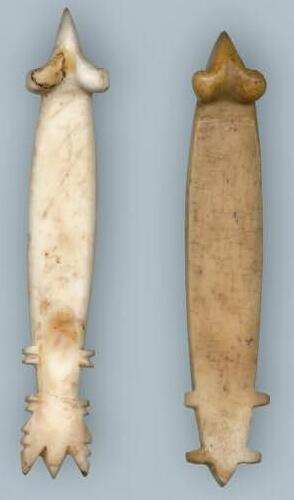

Examples almost identical to the following one-piece tur tle shell hook on p l a t e 9 a r e i l l u s t r a t e d by B e a s l e y. T h e y we r e c o l l e c t e d o n t h e D a n i e l s Ethnog raphical Expedition of 1904-1906, and appear to be ver y rare, as there are no other examples known in the literature apar t from those mentioned here

T he tur tle shell hook illustrated here measures 9.3 cm and is the long est example known It was cut from the tur tle shell and not bent under heat Its surface was meticulously smoothed It has the same eleg ant for m as Beasley’s hooks A crenellated ridg e is also present here, but only along the outside of the hook’s base Visually, the ridg e seems to connect the shank with the point, the two being almost parallel with one another. Unfor tunately there does not seem to be any infor mation or explanation available with reg ards to the possible meaning of the crenellated ridg es Equally little is known about how exactly the hook was used, or what type of fish it was intended to catch.

Finsch, who had much first-hand knowledg e of the nor th coast of New Guinea, stated the following: “Net and reef fishing are predominant, and hook fishing is of lesser impor tance. T here are no fish hooks along the south coast or in the easter n por tion of British New Guinea But Moresby mentions some from the latter area (Possession Bay), apparently made of pearl shell ( )” (40): 129

A simple bent tur tle shell hook is known from the Tor res Strait. Haddon states: “T he fish hooks were used in pairs, each being tied at the end of a piece of thin string of sinnet but they admit of ver y little decoration ” (41): 35

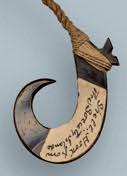

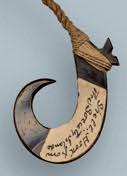

T he decorated one-piece tur tle shell hook illustrated here was not used for fishing It was made from the thick par t of the edg e of the shell Haddon shows several examples of the Sabagorar hook or naments, and makes the following obser vations with reg ards to their use: “T he Sabagorar is a ver y interesting tur tleshell or nament of varied for m which was wor n by the girls, and for med par t of their mar riag e outfit. T his cer tainly was the case in Mer; but I do not know how far the custom extended in the Straits ” (41): 33

T he one-piece hook on plate 11 is also made of a thick piece of tur tle shell. T he shell becomes thinner near the head, in which a suspension hole is drilled T he fiber remains of the attachment string are ver y similar to those on the previous hook and indicate that the hook was used as an or nament T he shank par t of the hook with the fin-shaped extension at the base can be inter preted as a stylized fish A small label on this “fin” reads “purchased Febr 12, 1838”, and this date makes this the oldest known Sabagorar (*5) Wichmann documents ships known to have moved through the Tor res Strait in the 1830s. (30): 37-42. In 1836, Lewis visited various Tor res Strait islands (including Mer, Waier and Er ub) in search of sur vivors of the Charles Eaton, and made contact with the natives there T he hook is similar to the example illustrated by Haddon (41): Fig 12, E T he finlike extension is present in this case, but ver y r udimentar y T he three V-like extensions, with hatch marks that extend onto the hook itself, present on the example shown in Fig 12, K, can also be inter preted as re presentations of fish

Four other Sabagorar hooks shown on this plate are similarly decorated

There is no infor mation available on the use of fish hooks by the peoples of the Papuan Gulf area Williams obser ves: “There is a g reat variety of fishing

31

Pl. 9

Pl. 10

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 31

Pl 11 (*3) (*4) (*5)

methods in Orokolo Bay, and often mighty small results from any of them ” (42):18

T he Marind-Anim appear to practice hook fishing in only a ver y limited way In his comprehensive publication, Wirz shows only a drawing of a composite hook fashioned from palm bast and remarks: “T he Marind hook is in fact quite primitive, and of not much use. (...) T he materials it is made of make it suitable only for ver y small swamp fish, and it is consequently seldom used ” (43): Par t 1, 102 In the various recently published monog raphs on the Asmat and the Mimika, no mention is made of hook fishing

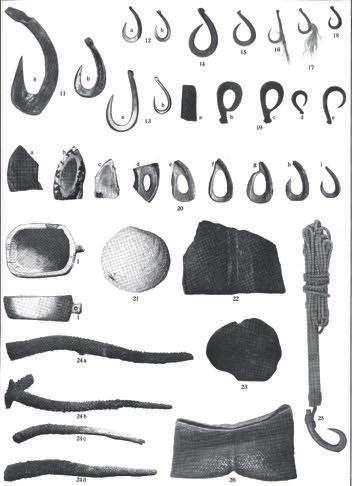

A one-piece bone hook was in use in the Sepik River area(*1a/b) (45): 2223. Reche describes one-piece hooks made of both bone and mother of pearl. (44): 249 Two Se pik bone hooks with barbs, collected by Mead in 1933-34, are in the American Museum of Natural Histor y in New York (#80 0-8186B) HauserSchäublin states that hook fishing was a women ’ s activity on the Se pik, and that men did not practice it

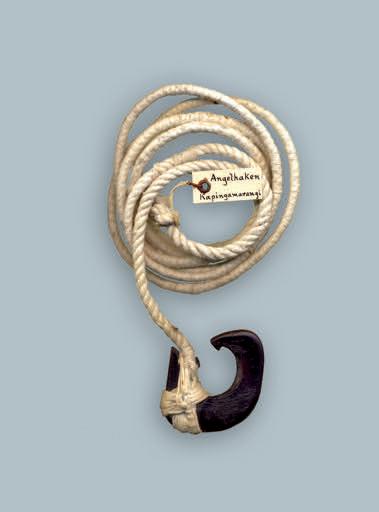

T he islands of Wuvulu and Aua along the nor th coast of New Guinea are described by Finsch as “centers for the mass production of fish hooks”, and constitute a case apar t (40): 130 “On these isolated islands, one works however only to supply one ’ s own needs, and produces hooks that all have the same for m, but may be of var ying size and either entirely of tur tle shell or entirely of sea shell.”

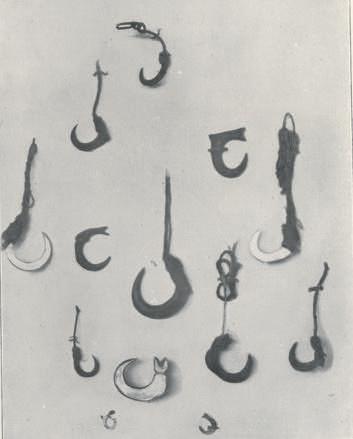

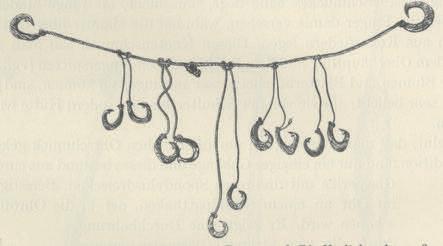

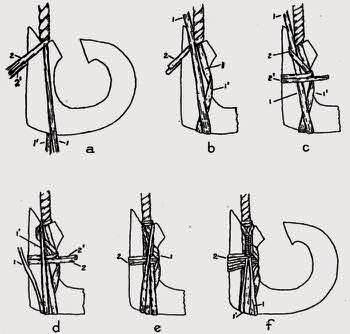

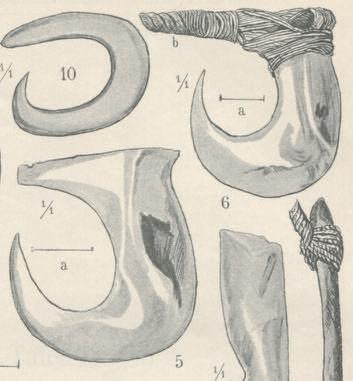

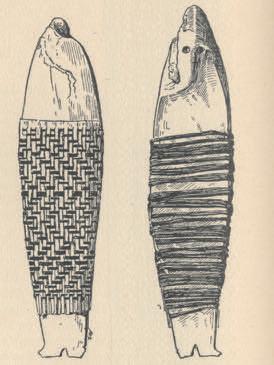

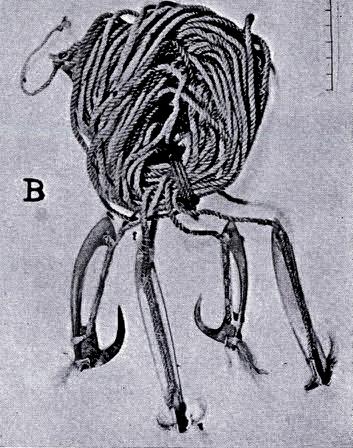

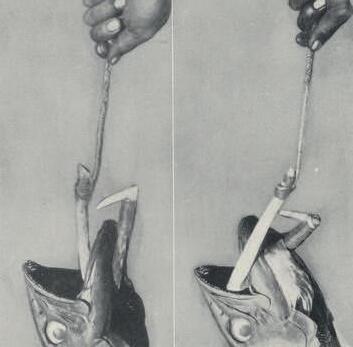

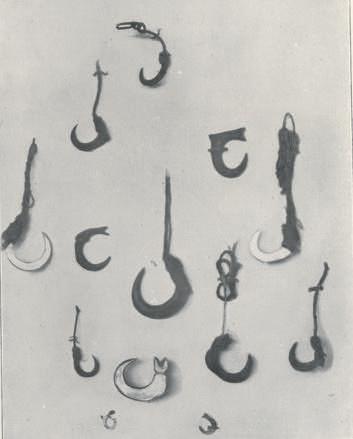

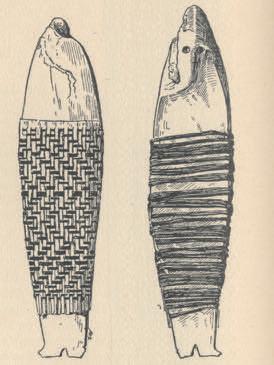

Hambr uch describes the manufacture of these one-piece hooks in g reat detail (*2), (46): 110 Plant fiber mats (for example banana leaf mats on Wuvulu, and coconut bast mats on Nukuoro) are made for hanging g roups of hooks in rows Plate 12 illustrates a mat of this kind, which displays all varieties of one-piece hooks, made of Burg os and Trochus shell, as well as of tur tle shell. Ar tificial hackles are sometimes affixed to these little hooks T hey are made of feathers, as in the case of the hook in the middle (*3), or of plant fibre, as may be seen on the hooks shown on the plates 13 and 14. Hambr uch shows the unusual binding of the lines to the ver y carefully worked sea and tur tle shell hooks (*4), (46): 110

Robust one-piece Trochus shell hooks, ranging in size from a few centimeters to as much as 9 centimeters, are a par ticularity of the Wester n Islands of the Bismarck Archipelag o

“T hey are used with or without bait, de pending on what type of fish one intends to catch. Often the faint glitter of the mother of pearl that the hook is made of can be enough to substitute for bait, if the hook is cleverly thrown ” (47): 215 T hese hooks are made from the lower spiral of Trochus Niloticus or Turbo Mar moratus. “Fish hooks of this type (Awi) (*4) were an expor t item until a few decades ag o, from K aniet to Ag omes and Ninig o ” (40): 130 A hook that is nearly identical to one seen in T hilenius is illustrated in the lower right of the plate 14 (47): 245 It is different from it in that no g roove is present for the tying of the line T his carefully fashioned hook was once used by the fisher men of Ninig o for catching larg er species of fish. Two classic shark hooks from Aua are shown on plate 15

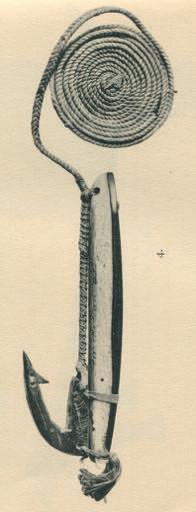

T hey are masterfully crafted with the simplest tools from the lowest spiral of a Trochus shell. T he filed g roove at the top of the shank around which the meticulously tied plant fiber line is attached, is readily recognizable In order to

32

Pl 12 Pl 13 Pl. 14 Pl 15

(*1a) A fishing pole with a one-piece bone hook is displayed in the per manent collection of the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin.

(*5) Hambr uch calls them Awui (46): Pl XIV 11

(*3) Detail of the mat illustrated in plate 12

(*4)

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 32

(*2) (46): Pl XIV, illustrating the different materials used in fish hook manufacture

make this line more capable of withstanding a shark’s bite, it was strengthened by winding a finer fiber line tightly around it.

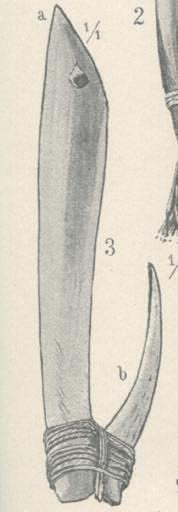

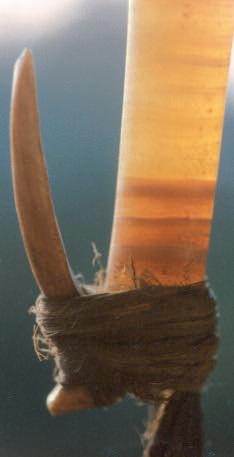

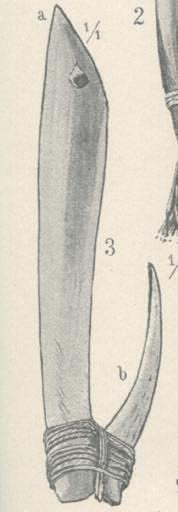

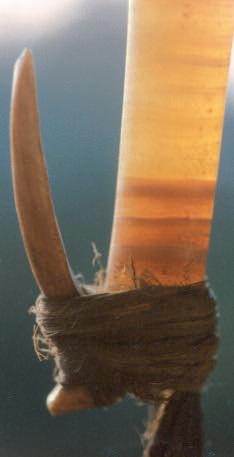

T he following hooks also present a cer tain par ticularity T heir lines are equipped with a wooden bite bar T his consists of a longitudinally cut wooden tube, through the middle of which a line is passed. T he two sections of the tube are bound tog ether at the top and at the bottom, and in the case of the long est one, also in the middle (46): Pl XV

T here are hooks from the Admiralty Islands in many collections that have been debated intensely for over 100 years T hey are made up of a wooden shank through which a piece of Trochus shell (*6) or a pig tusk is bored and secured with Parinarium gum T hilenius describes these hooks as tools for picking fr uit Never

mann states that these up to 40 cm long hooks were used in various ways: “T here is probably not just one way of using these hooks, but they rather ser ve alter nately as fr uit pickers, fish hooks, or even suspension hooks, according to the custom of the location or, as on Pitilu, the need of the moment” (48):161 Ohnemus illustrates a shark hook from Andra that is made of a half pig jaw with only one tusk remaining in it All the other teeth are removed, and the g aps filled with Parinarium gum (49): Ill 150 Finally, there is an example at the Linden Museum in Stuttg ar t, whose ver y long shank sug g ests r ules out that it could have been used for anything but picking fr uit

T he one-piece trochus shell hook (*7) from the Admiralty Islands (Manus Island) is similar to an example that Moseley illustrates in his account In 1877, he wrote: “Fish hooks are used made of Trochus shell, all in one piece T hey are of a simple hooked for m without barb. T he natives did not seem to care for steel fish hooks, and apparently did not, at first at least, understand their use ” (209): Pl XXI, fig 12; 27-28

Ohnemus presents a comparable hook, whose three stranded plant fiber line is attached to the hook with a resin paste as it is on this example (*8)

We lear n from Never mann that “T he hooks ( ) are 5 or 6 centimeters long, and at their tops (...) have a dense binding of finely made string, which is sometimes additionally covered by a layer of Parinarium gum paste ( ) Parkinson (1907) already noted that the Trochus shell hooks were being re placed by iron ones (...) Usually, three men fish simultaneously with rods from one canoe ” (48): 162163 As is so often the case, there is unfor tunately no indication given of what kinds of fish these hooks were intended to catch

Never mann illustrates only 3 to 4 cm long tur tle shell hooks from the St. Matthias Islands, all quite cr ude and without barbs (52): Ill 31 T hese had been nearly completely re placed by metal hooks by 1908 Even from New Ireland, with its extensive coasts, there is only ver y sparse infor mation on the practice of hook fishing Beasley illustrates two Trochus shell hooks that probably come from the Wester n Islands. (8): Fig. 30. Neuhaus describes fishing on the reef as more of a pastime or a spor t: “For fish hooks, the natives used a barbed piece of Rotang palm or Mumlang a Mumlang a is a plant which is abundant along the coast, and has long tendrils and thor ns. T he barbs on the Rotang palm and the Mumlang a are small, and the natives could only catch ver y small fish with such hooks ” (53): 92

33

16 Pl 17

Pl.

(*7)

(*1b)A bone hook from the Sepik

(*6) Detail of the shank of the left hook on plate 17.

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 33

(*8) According to Ohnemus, the sap of the Pir u palm is mixed with that of the breadfr uit tree (Kuli) to make this paste on Andra (nor th coast of Manus Island) (49): Fig 148

T he hooks that the natives made of tur tle shell and bent under heat were much strong er, but they were eventually re placed by the introduced metal hooks.

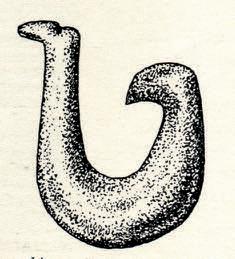

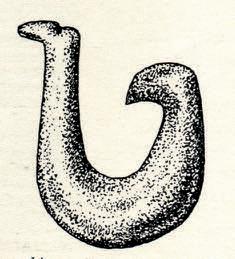

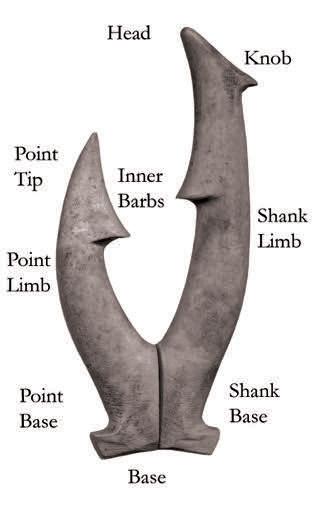

T here is however a type of hook known in museums and mentioned in the literature Beasley illustrates but misattributes it in (8): Pl CXXX Buschan brief ly mentions a tur tle shell hook from Siara in souther n New Ireland. T here are numerous records of such hooks in Ger man ethnological museums In Stuttg ar t’s Linden Museum, Buschan’s hook (*1), (54): Ill 98 is shown alongside several other examples of this type T he half-circle shaped head, the widened and notched shank limb, and the point bent upwards under heat, are the hallmarks of this type of hook. Another variant of this type can be found in the Hamburg er Museum für Völkerkunde (*2) (55): Pl 5 14 It is of special interest because of a stone sinker that is ar tfully tied into the line Unfor tunately, no infor mation is available as to how this hook was used. Was it cast from a reef or from a boat, and what kind of fish was it intended to catch?

Ste phan and Graebner give an over view of fishing equipment from souther n New Ireland. (56): Ill. 61. T he authors attribute the impor tance of fishing to the scarcity of g ame animals on the island, and to the wealth of edible species of fish in the sea “T he original hooks were made of tur tle shell Nowadays, notably in Laur, iron hooks are already being used, but they are tied to a piece of mother of pearl in a traditional manner ” (56): 65 It is difficult to ascer tain to what extent the aforementioned hooks were used on the larg e island of New Britain, due to the dear th of infor mation in the literature on this subject With respect to the Duke of York Islands, which lie between New Ireland and New Britain, Ribbe remarks: “Hook fishing does not appear to have been ver y widespread in the Duke of York Islands Nowadays only European hooks are used Fish hooks from the inland are said to have been made of mother of pearl, wood, and fish bones, but I have never seen such a hook on the Duke of York Islands”. (57): 443. While the hooks attributed to New Britain and illustrated by Powell in 1884 (*3) tur n out to be mostly fantasies, some proper examples are illustrated by Beasley (8) Pl CXII

T he composite hook he shows does resemble those seen in Ste phan and Graebner. (56): Ill 61 Beasley says the following about Powell’s composite hook: “T he shank is of mother of pearl, having a tur tle shell barb, obviously shaped by heating into a pronounced cur ve. ” (8): 73. Next to it, Beasley illustrates the earliest hook collected on New Britain (*4) He writes: “Fig 29 is taken from Hunter’s Voyag e (58): 233, and was obtained in 1791 from the Duke of York Islands T he material is obviously tur tle shell, and (...) is reminiscent of those from Mur ray Island in Tor res Straits ” (8): 73

Similar tur tle shell hooks are known from the Solomon Islands

It is possible to conclude that hook fishing was of ver y little impor tance on New Britain Missionaries like Meyer and Kleintitschen, who spent many years on the island among the natives and investig ated fishing ver y closely, describe hook fishing only peripherally In the comprehensive chapter entitled “Hunting and Fishing” (59): 65-90, Kleintitschen does not even mention it, while Meyer describes it as being ver y primitive. The latter states: “Fish hooks made of shell were unknown here The hook consists of a Rotang palm spine a few centimeters in length

34

(*3) Powells plate of fantasies in: Allg emeine Völkerkunde, A Heilbor n, Leipzig, 1898, Ill 52 (*4)

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 34

(*1) (*2)

Bait was attached to the end of the spine The line was hand held, or placed in the water with a f loat.” (60): 1078-79, Pl. 10.

Solomon Islands

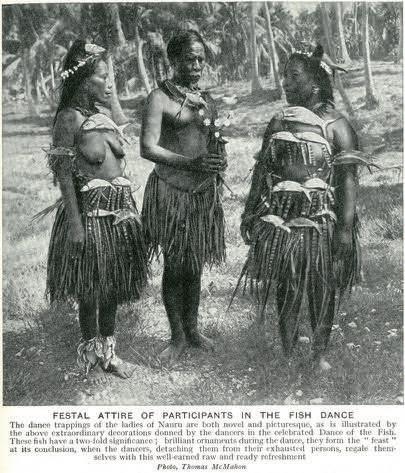

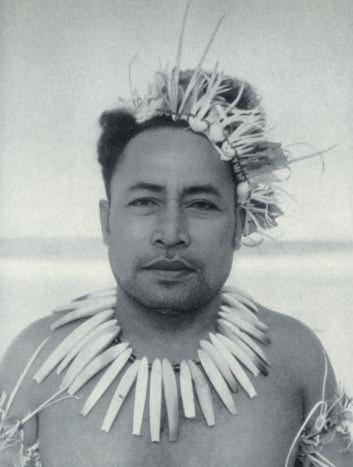

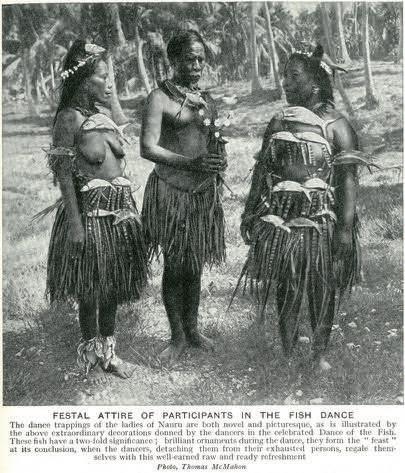

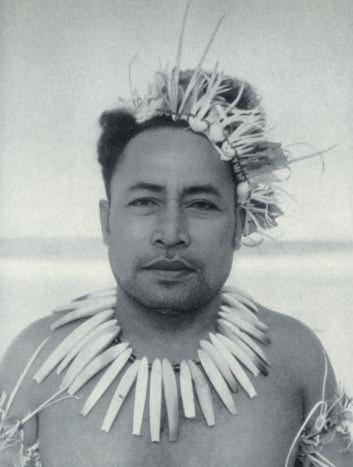

T he most ar tfully made fish hooks of Melanesia are from the Central and Southeast Solomon Islands T hese composite hooks are used for catching bonito In order to understand why these hooks are so carefully made, and why so much time is devoted to their manufacture, it is impor tant to know a few basics about the bonito cult, which was most widely practiced in the southeast Solomons “T he chances taken in bonito fishing, the constant dang er of bad weather and sharks g enerated a dee p feeling of de pendance on the spirits of the Ocean. T he vision and worship of these g odly beings dominated the religious and to some extend the ar tistic life of these peoples ” (221):209 T he bonito cult plays a central role especially in the initiation rituals for boys. T hey move out to sea with experienced fisher men, in the sacred and richly or namented boats, to catch the first bonito By drinking some drops of its blood the mystical substance of the bonito is passed on to the initiated boy. (*5), (compare (136): 158, 312-314)

Hooks were all the more valued when they had been successfully used, and were passed down from g eneration to g eneration

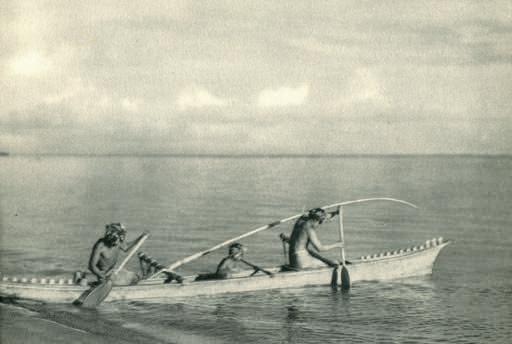

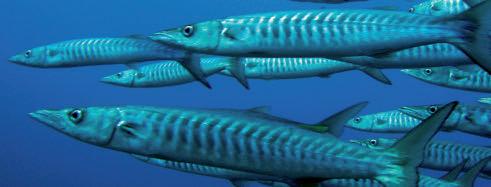

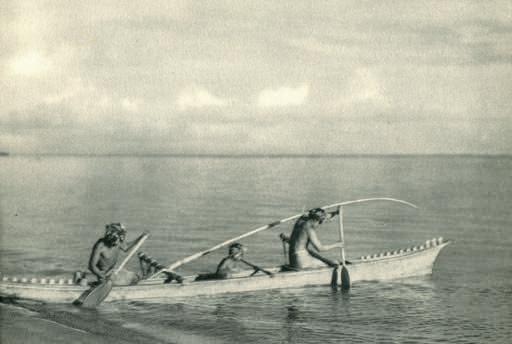

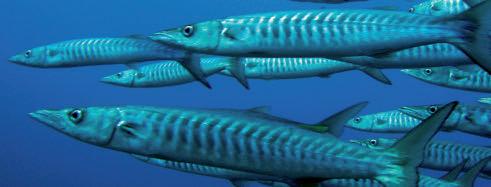

T he bonito (*6), which weighs up to ten pounds, was a highly coveted fish In the windless weeks from December through March, it was pursued by light and beautifully decorated three-man canoes, and caught with these hooks. T he location of bonito swar ms could be deter mined by the presence of seagulls and frig ate birds hovering above them T he birds were attracted by the surface splashing of small fish being hunted by the bonito.

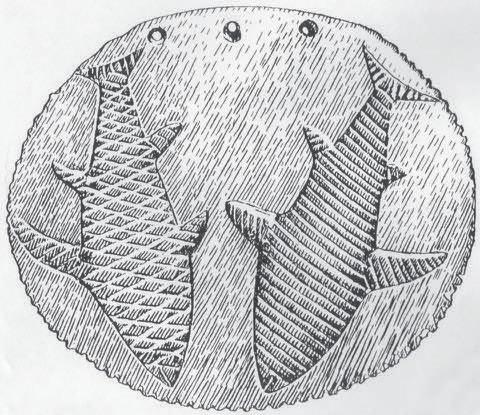

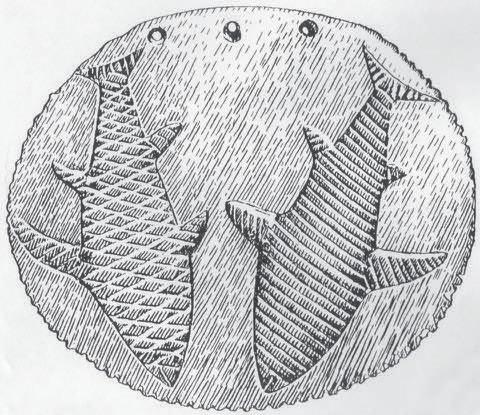

A paddle blade from Santa Isabel Island (*7) impressively renders the dynamic of the bonito hunt Sea spirits lead the bonito swar ms towards the coast

A sea spirit is shown at upper right on the paddle blade. Ever ything that had to do with the catching of the bonito was of sacred character Bonito hooks were not seen simply as functional tools, but as the prized objects that should tempt the desired fish to catch them. As a result, all of the component pieces of the hook –the Tridacna shell or mother of pearl shanks, the eleg ant tur tle shell points, the bead hackles, and the finely worked plant fiber lines that ar tfully held the par ts tog ether – were made with meticulous care and attention to detail. When one considers the frig ate birds that f ly above the seagulls and steal their small fish, one is tempted to draw a connection between the shape of their eleg antly for med beaks holding prey and the beautiful shape of the tur tle shell hook points T heir inward cur ve seems to imitate the wonderful swee p of the frig ate bird’s beak T he prey can find release from neither the frig ate bird nor the hook.

T he bonito hook (*8) has a tur tle shell point which is probably unique, in that the head and beak of a frig ate bird are clearly rendered on it T his of course suppor ts the notion expressed above.

T here are many different types of hooks from the Solomon Islands and

(*6)

Pl 18

Pl. 19

Pl. 20

Pl 21

Pl 22

Pl 23

Pl 24

Pl. 25

Pl 26

Pl 27

Pl. 28

Pl 29

Pl 30

Pl. 31

(*8)

35

(*7) Illustrated here is a r ubbing made from the relief car ving on the paddle.

(*) A frig at bird amulet from New Georgia in the Central Solomons, car ved from mother of pearl (14,5 cm max length)

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 35

(*5) H Fischer-Har riehausen gives a comprehensive description of the bonito ritual in Central Melanesia, using all available bibliog raphical infor mation

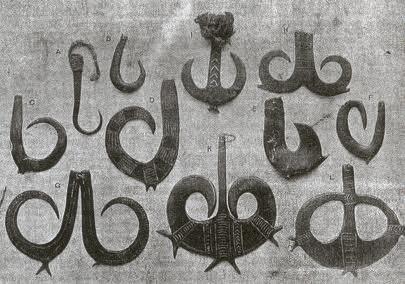

they are among the best researched in Oceania T he first illustrations appear in the Godeffroy catalog of 1881 (2). Edg e-Par tington illustrates nearly all the different kinds in 1890 (3) Additional illustrations and infor mation are found in Woodford (1918) (4), Ivens (1927) (5), Blackwood (1935) (6), and Ber natzik (1936) (7) T he first comprehensive over view of Oceanic fish hooks by Beasley, published in 1928 (8), describes nearly all known types from the Solomons “To deal adequately with all the hook for ms which originate from this g roup would be an almost impossible task It is rare to meet with an example that is properly localised, and it is only by accumulating considerable numbers that one may ar rive at even a rough deduction In this g roup the composite varieties are much in evidence, and var y from the cr ude shank of Tridacna shell down to the minutely car ved for m of some insect, attached to the tur tle shell barb, which, in order to render the contrivance more effective, has chang ed into a complete hook.” (8): 67-68. For ty five years later, Cummings (9) investig ated hooks used for bonito fishing on the basis of examples in Chicag o ’ s Field Museum of Natural Histor y and other examples in the literature He distinguished five different hook types and assigned them to par ticular areas.

T hree years later, K aschko (10) studied hook types on Uki Island and obser ved the process of their manufacture Bell/Specht/Hain (11) examined Cummings’ work in light of the 259 specimens of composite hooks in Australian museums, and came to both identical and dissenting conclusions, with reg ards to their locations of origin Neither study includes infor mation on the one-piece hooks in the UkiUlawa area or the hooks of Sikaiana K aschko (10) made impor tant contributions to knowledg e of the hook types on Uki He obtained infor mation on six types of hooks, including their indig enous names, methods of use, methods of manufacture and value

Tw o-piece Bonito Hooks

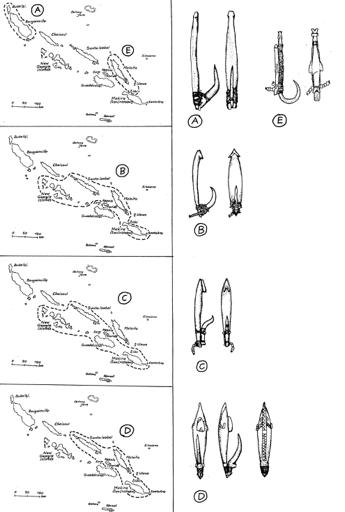

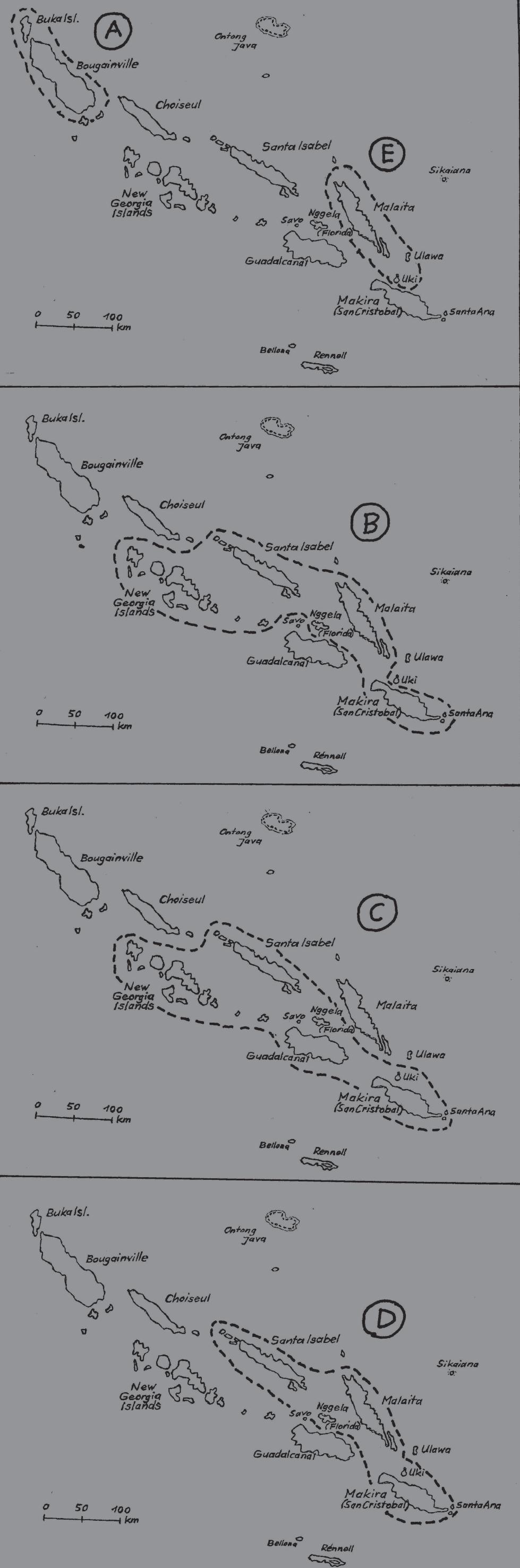

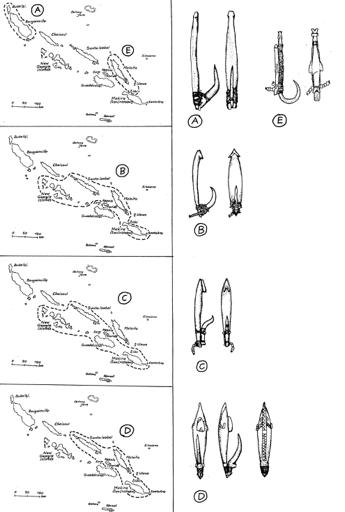

T he four maps show the regional distribution of five hook types Why some hook types occur in a ver y limited area, and others over a several hundred kilometer region is ver y difficult to ascer tain It is cer tainly tr ue that in spite of cultural and linguistic differences between them, the islanders traded actively and g roups had contact with one another. Fish hooks were among the commodities that thus traveled over wide distances

T hese simply designed hooks (A) were restricted to the islands of Buka and Boug ainville. We know from Blackwood that “T he hooks var y considerably in size ( ) No mention was made of choosing hooks of colour suitable to weather and water, as re por ted by Hiroa for the Samoans, or that one kind was used in the bow and one in the ster n as re por ted by Ivens for the S E Solomons ( ) bonito fishing is usually car ried out from a plank canoe (mon), the smaller ones, with three seats, being used for this pur pose (...). Two rods are taken in each canoe, one to be used from the ster n and the other from the bow T he ster n line is ke pt trailing behind the canoe, the bow line is cast If there are more than two men in the canoe, the man in the bow does not paddle, but devotes all attention to playing for the fish. T he man at the ster n must attend to the steering as well as to his rod and line His

36

Pl. 18

(*) A typical C type hook

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:08 Uhr Seite 36

(*) A typical E type hook.

37

(*) A typical D type hook.

(*) A map, illustrating the regional distribution of bonito hooks of types A, B, C, D and E in the Solomon Islands, drawn after Cummings (9) and Bell, Specht, Hain (11)

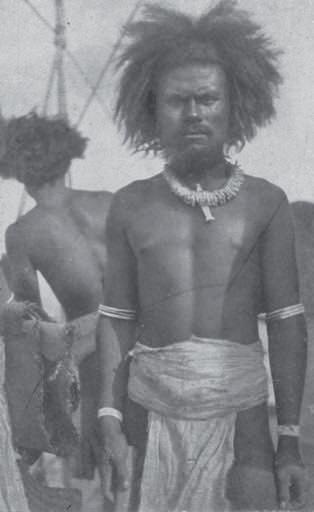

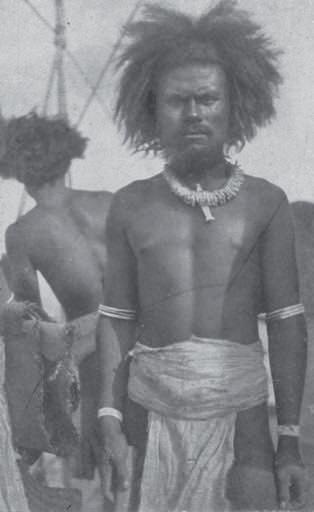

(*) Chief Hopkins on Ulawa, holding two strings of spider web bait, raotai, to be used with a kite for catching mwanole fish (see also p 19 (*3))

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 37

Photo: Amu Reiter

rod is not held in the hand, exce pt when landing a fish ( ) When a fish takes the hook, the paddle is thrown into the bottom of the canoe, the rod is caught up, and the fish jerked over the side Only one hook is attached to each rod No bait is used, the resemblance of the hook to the small fish on which the bonito feed being sufficient attraction. T he first bonito caught after a period of bad luck is decorated with paint and put back into the sea T his is supposed to attract the other fish to the hook ( ) In view of the impor tance attaching to bonito fishing in the native mind, it is natural that there should be a larg e number of “medicines” or magic, and an elaborate ritual directed towards ensuring a g ood catch Bonito magic is not common knowledg e, usually only one or two men in each villag e know it.” (6): 329331

T hese type A hooks are the long est in the Solomons “T he leader (attachement knob) is simply a g roove around the top (head) of the shank. (...) T he point is lashed into place with the help of lugs or holes through it Smaller fillersticks of wood on either side of the point ser ve as suppor t ” (9): 10 T his method of securing the tur tle shell point with little sticks of wood is also widespread in Micronesia

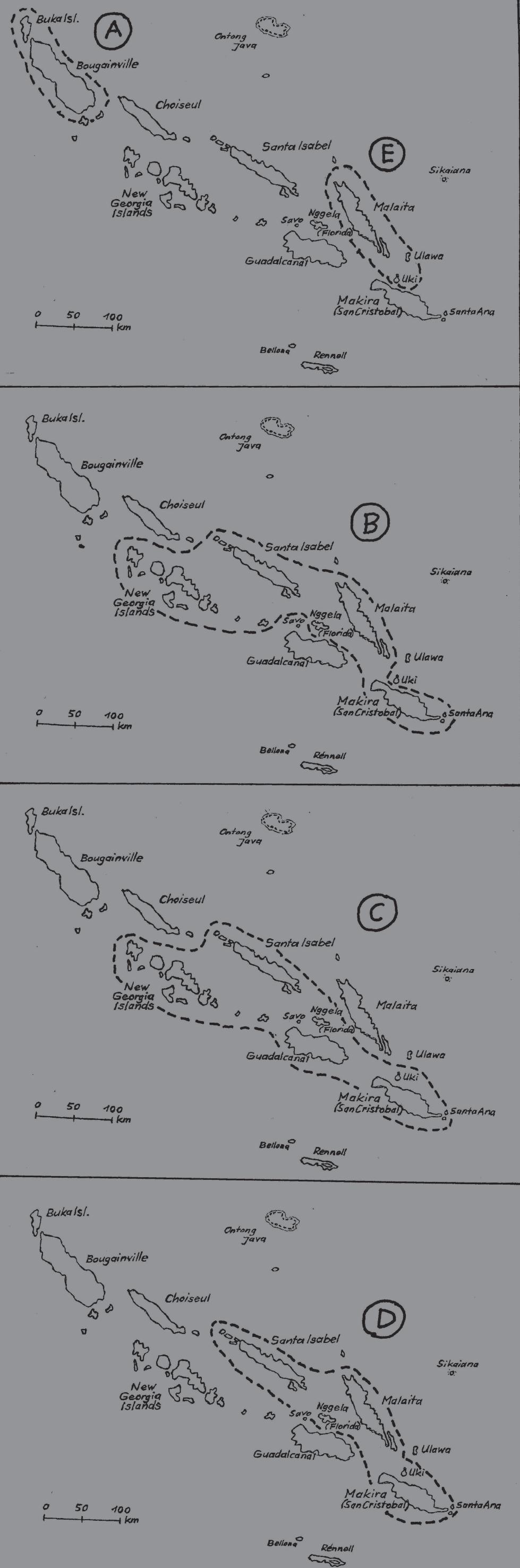

An examination of the distribution maps of composite bonito hooks reveals that Choiseul Island is the only island in the Solomons for which the literature provides no infor mation on any type of hook However, research in the Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde in Dresden uncovered the existence of some examples attributed to Choiseul (coll 1897 by R Parkinson, no 32091), which are nearly identical to the hook illustrated here on plate 19 T his hook consists of a wooden shank bound with plant fiber line to which a wooden point is tied at a shar p angle T he binding is often strengthened with an application of Parinarium gum In the British Museum, there are also three V-shaped two-piece wooden hooks from the Beasley collection. T hey are attributed to nor ther n Boug ainville (the neighbouring island) and described as Ir okokoito Unfor tunately there is no infor mation on the method of use of these hooks In the Museum für Völkerkunde in Munich, there are two bundles (*1) containing over a dozen of these hooks (12-43-33b), which are incor rectly attributed to the Admiralty Islands T he description states that they are made of one piece of wood, notched and then bent back to for m the stee p angle, and finally bound tightly with strips of plant fibre (in the strictest sense of the word they therefore would have to be filed under “one-piece” hooks)

T he following plates clearly show us the variety and beauty of Solomon Islands bonito hooks T he shanks are most often of mother of pearl, rarely of Tridacna shell (*2) T he points are made of tur tle shell T he hook (*3), which is clearly type C, has a highly unusual and striking shank, which is made from the lip of a cowrie shell Samoan bonito hooks with similar shanks are known (compare plates 83 and 84).

T

understanding of the working of the materials involved So do the bonito hooks on the following plates. T he fisher men who created these objects unfor tunately remain unknown We can only refer to ethnog raphic literature to understand how

h e t wo e x a m p l e s o n p l a t e 2 0 d i s p l ay e v i d e n c e o f a c o m p l e t e

38

Pl 18

Pl 19

Pl. 83 Pl 84 Pl 20

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 38

(*1) (*3)

they were manufactured, and the time it took to produce them Like all bonito hook shanks, the Tridacna shell shank shown here on Pl. 20 u.l. and (*2) assumes the for m of a stylized fish, but it is exce ptional for its detailed work T he eyes, the fins and additional or namentation are rendered meticulously, all with only stone ag e tools. T he Tridacna shell fish appears to swim towards the eleg antly shaped tur tle shell point of the second hook A fish hook of such vir tuosic for m is without peer in all of Oceania For what reason did its creator summon all of his skills and for mal ideas to make such a hook? Undoubtedly, the idea that the sacred bonito on a sacred fishing mission could only be caught with a “beautiful” hook played a central role in motivating him. T he plates 21, 22 and 23 show all variants of types B, C and D T he compact hook (Pl 22 t m) is of type B, and widely distributed in the Solomons T he shank was par ticularly ar tfully constr ucted in the for m of a stylized fish. Cummings states the following about this type of hook: “It is wide on the top, tapering towards the base, with the thick hing e par t of the shell at the top to for m the knob T he knob itself is car ved to for m two shor t projections which point downward and ser ve to hold the line in place.” (9): 11. T he type B, C and D bonito hooks illustrated here show a g reat deal of variation both in the shape of the tur tle shell point and the manner in which the knobs are car ved to fit the snoods. Cummings states the following with reg ards to type C: “T he knob of these hooks is car ved on the shank near the head; it is triangular in shape and projects out from the inner surface of the shank It is g rooved to hold the line ” With reg ards to the point, he adds: “T he point is attached using small car ved lugs on the point without the help of the holes ” (9): 12 T he two hooks (1 and 4) illustrated in the lowest row are classic examples of type D. Cummings describes them as follows: “Specimens of this type differ clearly from the other recognised stylistic for ms in several respects T he dorsal side of the shank has a car ved ridg e (or, in a mother of pearl shell example, an incised central panel) with cross-hatch, zigzag, her ring-bone, or transverse incised lines ( ) T he knob of all Type D hooks is a projection located on the inner surface of the shank, one-fifth of the way down from the head. T he knobs have either a simple appearance, or are more or less triangular in outline, in which case they closely resemble those on Type C specimens In addition, at the sides of the shank, on the same place as the knob, there are projecting fins or small transverse incised lines. T he head of the shank comes to a point ( ) In shor t, a Type D hook gives the appearance of a highly stylized fish ” (9):13 T he earliest illustration of this attractive type of hook appeared in the Godeffroy Museum catalog published in Hamburg in 1881 (2), on Pl XVII, Fig 10 2 T he smallest hook on plates 22 and 23 could be considered type C on account of its binding It is first illustrated in Edg e-Par tington (3): 209 On plate CIV of his monog raph, Beasley shows other examples of this quite rare type of hook Its place of origin is cer tain, as Codrington collected it on Ulawa Beasley remarks: “Whilst confor ming to the g eneral type of composite spinner hooks, yet in outline and the use of a par ticular shell for the shank they are unique T hese are cut from Trochus tesselatus and preser ve the delicate colours of this shell ” (8): 69, Pl. CIV.

Plate 23 illustrates the back sides of the shanks of type C and D hooks,

Pl. 20

Pl. 21

Pl. 22

Pl 23

(*2)

Pl 22

Pl 22

Pl 23

39

Pl 23 aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 39

Pl 23

Pl 22

Pl 23

Pl. 22

Pl 24

Pl. 25

Pl 26

most of which are decorated T he literature unfor tunately provides no satisfactor y explanation for the meaning of these or namentations. T he question as to whether they are marks of ownership remains open to question T he decorations usually consist of cross-hatching, applied to a convex strip that may r un along the entire length of the shank, or only a par t of it. T hese hatch marks also ador n the sides of the shank beginning at its middle On plate 23, Hook 4 also shows this type of lateral decoration Eleg ant cross hatchings are seen on the beautifully for med shank on plate 22 (u r ) T hey r un along the sides, from the area that re presents the pectoral fins to the shank’s end, where they meet Plate 23 of side views once ag ain demonstrates the ing enuity with which various materials were used in the manufacture of bonito hooks T hey are all type C T he var yingly shaped and eleg antly for med tur tle shell points are bound to the shanks with fine plant fiber twine, and the carefully worked side strip prevents the line from slipping. In the 20th centur y nylon line was also used because it was more resistant to cor rosion from sea water As early as the 19th centur y, finely worked shell beads such as those seen on plate 22 (bottom row) beg an to be re placed in many instances by impor ted European glass beads (Pl 22 first and second rows)

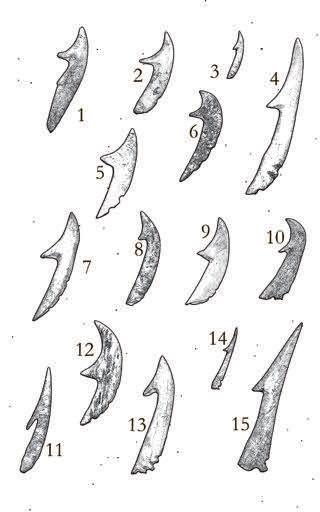

Pl 24

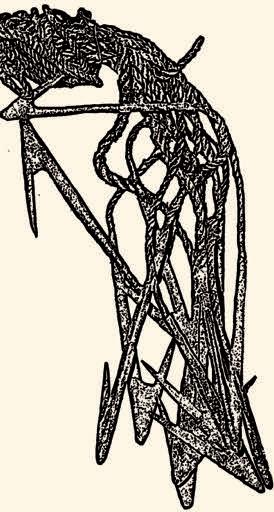

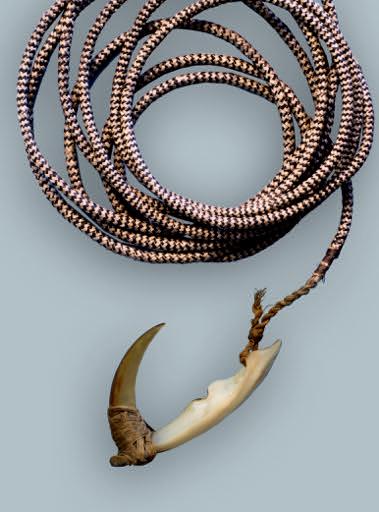

A unique variety of type E bonito hook (*1), restricted to the island of Malaita and the small southeasterly islands of Ulawa and Uki, is shown on plates 24-26 Cummings says the following about it: “T hey differ from the other types recognised in that the shank itself is of tur tle shell, bent in the shape of a conventional metal fish hook, rather than of mussel or pearl shell A strip of mother of pearl or other shell, however, is tied on to the dorsal side of the singlepiece hook (...). T he added strip is car ved to resemble a stylized fish or a cuttlefish or squid or a reef wor m (*2a) T he shank area of the tur tle shell hook is wrapped with native twine ( ) ” (9): 14 No comparable piece is found in the literature for the extremely small hook on plate 24. It appears to be unique. T he hook in the lowest row at right is of exce ptionally ar tful manufacture (*2b) In order not to obscure the imag e of the wonderful stylized mother of pearl fish with the extremely fine plant fiber binding, tiny protr usions around the head and caudal fin areas ser ve to hold the line securely to the tur tle shell shank Cummings, Bell, Specht and Hain all maintain the type E hook occurs only on Malaita However K aschko found it on Uki as well (10): 194. T he indig enous name for the hook is

Ta’i Hinou

Fully sculptural renderings of fish such as (*3) are rare among type E hooks. Edg e-Par tington shows a ver y similar example (3): 209, Fig. 6. T he hooks shown give a g ood impression of the countless variations seen in the mother of pearl lures, which are always bound to their shanks with meticulous care T heir ver y special appearance can be attributed to their for merly sacred character, in the times when the hunt for the highly prized bonito was sur rounded by taboos, and the techniques for the manufacture of hooks was transmitted from g eneration to g eneration

Pl 26

Plate 26 illustrates well the incredibly accurate plant fiber lashings all along and around the shank (bonito hook type (E)).

40

(*2a, 2b)

(*4)

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 40

(*1) A type E bonito hook collected on the Kor rig ane expedition with a stylized fish made of stone tied to its shank

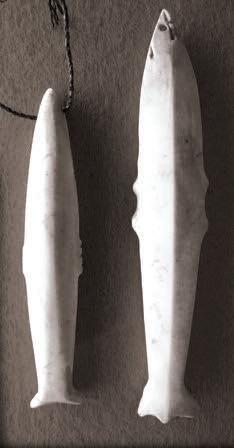

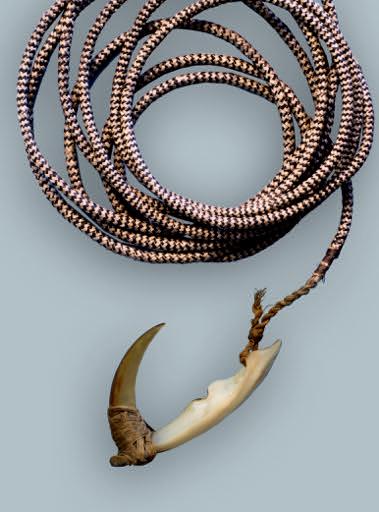

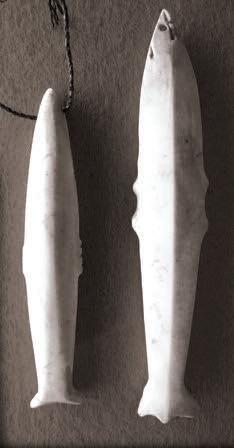

T he earliest illustrations of these unique hooks are also found in the Godeffroy-Catalog (2) T he hook appears in Edg e-Par tington (3) some ten years later. It is sur prising that these hooks, once ag ain re presentations of fish, remained confined to the islands of Uki and Ulawa nor th of Makira T hanks to Michael K aschko, who inter viewed the then 65 year old Wilson Waisau in 1971, many interesting details on the use and manufacture of these hooks are known For the hooks made of various materials shown on plates 27 and 28 we use K aschko’s studies as a reference. (10). T he fisher men call these hooks Ta’i on Uki. “T he Ta’i is a one-piece bonito hook that is made of various for ms of sea and snail shell But tur tle shell and bone are also used Mother of pearl predominates, and bone Ta’i are fairly rare”. K aschko gives a detailed description of the manufacture of mother of pearl hook “A new shell is broken by bur ning and pecking with a piece of cher t, and a piece is g round on the hau mea (g rindstone) to make it f lat and round T hen the haukala (stone file) is used to make a cut in the middle, and branch hau kau (coral) is used to expand the cut and shape the inside T he stone file is used to finish the shaping, the base, and the knob for attaching the line, and finally to smooth and shine the entire lure. A hau nati (cher t f lake) is used to drill small holes for eyes and make other markings on the body of the Ta’i T he bur nt fr uit of the talo tree is used to blacken the makings on the lure It takes four days of full-time work to make a Ta’i, and each man should have at least three or four ” (10): 195

When a par ticular Ta’i had proved especially successful, it would often be handed down from g eneration to g eneration, and was both stored and used with g reatest care If such a hook broke, it was ke pt, so that similar Ta’i could be made subsequently, using it as a model

T he extent of the Oceanic fisher man ’ s inventiveness with introduced materials is made clear by one of the rows of the one-piece hooks on plate 28, which are inlaid with circular pieces of lead Sur prisingly, K aschko does not allude to these long used hooks. On two of the Ta’i, the lead appears to re present eyes (nrs 5 and 9), and on hooks nrs 1 and 4, it reminds of the punctuate marks on the hooks called Toheo (compare plate 29) Nr 2 is another variant with lead inlay, and also has a small piece of lead tied to the back of its shank with nylon line. T he Ta’i on plate 28 (l l) is unusual for its somewhat compact for m, which results from the inlay, secured with Parinarium gum, on the back of its shank Unfor tunately no infor mation is available on the pur pose of these inlays, but it can be sur mised that the lead adds the right weight to the ver y light tur tle shell hook to facilitate sinking it to the optimal de pth

A few other unusual Ta’i hooks are especially notewor thy (*4) On the previous pag e is an old mother of pearl hook with notches along its rim T he stylized fish on the back of the shank also has these notches on its belly side. T he hook with shell inlay also appears to be unique It was collected in 1865 and is among the earliest hooks known from the Solomons T he shank made from Turbo mar moratus shell was covered with Parinarium gum, into which two shell beads were inser ted as eyes Another unusual hook was in the Hooper collection

41

The One-piece Bonito Hooks fr om the Uki-Ulawa Ar ea

Pl. 27 Pl 28 Pl. 28 Pl 29 Pl 28 Pl. 27

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 41

(*) Shanks of type B, left made from Tridacna shell and right made from bone

(*3)

Although of Tridacna and tur tle shell, bound tog ether with the ver y hard dr ying Parinarium gum, it must be classified as being of the Ta’i type. X-shaped pieces of cut Nautilus shell are pressed into the Parinarium gum on both sides of the shank (61): Pl 141, 1120

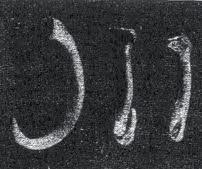

Two one-piece hook types, which K aschko classifies as Toheo and Toraho, are, like the Ta’i, restricted to the islands of Uki and Ulawa, which lie between Malaita and Makira Edg e-Par tington shows two of these small mother of pearl hooks and attributes them to San Cristobal (Makira) (3): Vol 1, Fig 10, 11

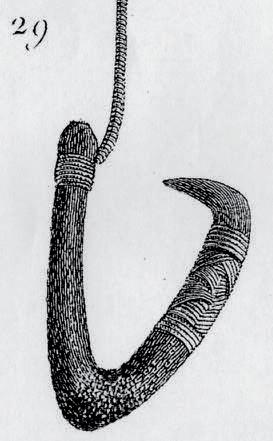

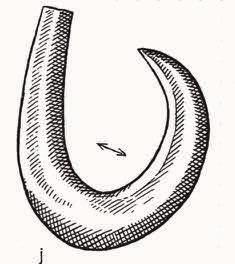

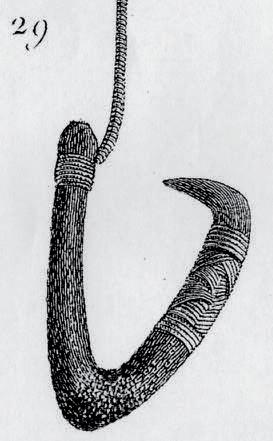

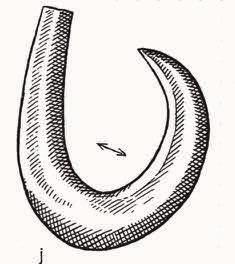

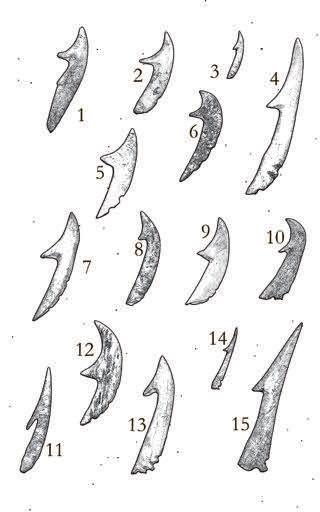

K aschko gives detailed infor mation on this hook type With reg ards to the Toheo on plate 29 he remarks: “T he Toheo is a small U-shaped lure and is made from r oa (pearl shell, usually of the black-lipped variety), wawahiu (an unidentified freshwater bivalve found on Makira), lauhi (Turbo mar moratus), and hato (Trochus shell). T he Toheo is used on a bamboo pole from a platfor m made of sticks and branches over the reef It is dipped up and down inside the water below the platfor m, and is meant to re present the movements of a tiny fish T he fish caught is the puma (mackerel). T he puma appears seasonally in r uns once a year, and in a g ood r un a man can catch a g reat many T he Toheo can break in three places: T he point can break off, in which case it can be reshar pened If the string breaks, the Toheo can be retrieved from the clear water. If a g ood Toheo loses its point limb, the shank may be retained as a model for making a lure A g ood Toheo may last a long time and be passed through g enerations ” (10): 196

Hook 3 on plate 29 (*5) differs from other Toheo in its almost naturalistic treatment of the caudal fin On other Toheo, this par t of the hook is used to fasten the line, and protr udes out from the shank at a right angle. T he shanks of nrs. 7 and 8 are sculpted in the for m of a fish, while the other hooks on this plate are more stylized re presentations of fish bodies

K aschko calls the ver y small hook nr. 11 Toraho. It took two or three days to make one Neither the Toheo nor Toraho hooks were used from boats, but rather from platfor ms T he Toraho was used to fish for a par ticular species of sardine

K aschko offers the following ver y detailed infor mation about Toraho nr. 11:

“T he Toraho is the smallest lure and similar to the Toheo It may be made from the same shell as the Toheo T he sequence of ste ps in the manufacturing process to produce a suitable blank are the same as for the Toheo (...). It takes about two or three days of full-time work to finish one Toraho Each man should have at least three or four Toraho or more T he Toraho is used on a bamboo pole from a platfor m over the reef, as the Toheo is (...). T he fish that is caught is the R aho, a sardine. T his fish appears seasonally in r uns once a year T he R aho strikes the Toraho as it hits the surface of the water T he Toraho and Toheo are used at different times, as the raho and puma appear at different times As with the Toheo, a g ood Toraho may last a long time if well cared for ” (10): 197

Woodford says the following: “T he lure is dropped about a foot dee p into the water and drawn up to the surface with a jerking motion When a fish is hooked it is skillfully dropped direct from the hook into a basket held ready for the pur pose in the fisher man ’ s other hand.” (4): 132. Hook nr. 9 on plate 29 is an unusual tur tle shell hook with a thickened shank Just as the previously described hooks from Uki,

42

Pl. 29

Pl. 29

Pl 29

Pl 29

Pl. 29

(*) A moder n combination of an old shank with a small fish car ved out of g reen plastic, from Ulawa

(*3)

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 42

(*5) Sketch of Pl 29

it was undoubtedly used only to catch smaller fish Comparable hooks are illustrated by Edg e-Par tington (3): Vol. 1, 209, Fig. 13, who attributes them to San Cristobal (Makira), and by Starzecka and Cranstone, who refer to them as being “probably Central Solomons” (12): 19, unfor tunately with no fur ther explanations

Other hook types from the Solomons are on the plate 30. T hey are made of tur tle shell Exce pt for the exce ptionally well made hook (u l ), which also has a ver y fine plant fiber binding, there are comparable examples in the literature Woodford illustrates this type and states: “T his is a hook of tur tle-shell, and appears a clumsy enough implement in itself, unless it is intended to be both hook and bait in one; it may be meant to re present a wor m, (...) or it may be a por tion only of a complete lure ” (4): 131 T he hooks u r and l l have well sculpted shank heads T he second (u m ) is an unfinished tur tle shell hook, at a stag e of manufacture where the shar pened point still needs to be bent with heat, before it assumes the shape of the one below

T hree One-piece Tur tleshell Hooks and a Prehistoric Bonito Hook Shank from Guadalcanal (windward coast)

T he in-de pth research done by Amu Reiter in 2007 and 2010 is to thank for the identification of the hook types shown here T he one-piece tur tleshell hooks were collected in the area of Marau (on the east coast of Guadalcanal) (*1)

T he triangular shape of the top of the shank distinguishes these hooks from other tur tleshell hooks in the Solomons

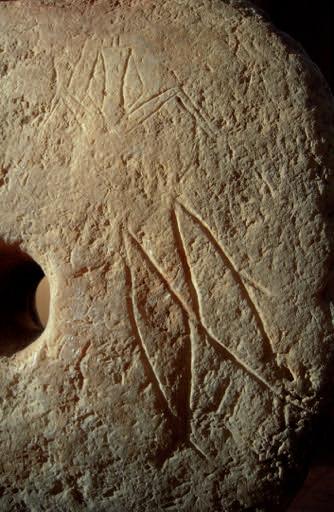

T he prehistoric shank (*2a) is notewor thy for two reasons: firstly, because it is so far the only archaeological bonito hook shank known from the Solomons, and secondly because it displays a configuration of the shank top only found on a historic example (*2b) discussed below. T he prominent cross ridg e on the shank ensures that it can be bound to it to its line ver y securely T he ver y old and ar tfully shaped shank is probably made of Tridacna shell and has a binding which is unique not only in the Solomon Islands, but in all of Oceania. Future research and archaeological excavations on the so-called windward coast might bring other examples to light in the future T hat the tradition of making shanks with this cross ridg e for the attachment of the binding endured well into the 20th centur y, is demonstrated by the complete bonito hook with its mother-of-pearl shank T his hook was also collected by Amu Reiter on the windward coast, in Masi villag e

A One-piece Tur tleshell Hook and Two Sinker Stones from Ulawa (*3)

One-piece tur tleshell hooks are known from many regions in the Solomon Islands Exactly how they were used, and what types of fish they were used to catch, is inadequately understood. No infor mation could be obtained about this hook, nor about the two sinker stones, which were collected inde pendently of it T hey are, and will probably remain, silent witnesses to a highly developed fishing culture that once existed (*4). It is possible that tur tleshell hooks of this size were baited, and lowered to the desired de pth with the small sinker stones

(*1) T he two type E bonito hooks, with the stylized bound mother-of-pearl representation of a f i s h , w h i ch a r e t y p i c a l o f M a l a i t a , we r e collected on the windward coast of Guadalcanal, and are readily recognizable by vir tue of this triangular shape at the top of the shank

(*4) Hviding (1996) describes a larg e number of fishing techniques for tiny Marovo Lag oon alone: “More than seventy named and distinct fishing methods exist in ten main categ ories, and t h e nu m b e r i s mu ch h i g h e r i f f u r t h e r classification is made, based on subcateg ories of methods that are species-specific and adapted to n a r r ow l y d e f i n e d m i c r o - e nv i r o n m e n t s ( )

Hook-and line fishing (21 methods) is the most widely used categ or y of fishing in contemporar y Marovo ” (215): 212 It is moreover ver y probable that only a fraction of the many methods once used could still be identified in 2011

43

Pl 30

(*2a; 2b)

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 43

T he old and unusually shaped tur tleshell hook on plate 31 has a two-stranded twined plant fiber line, and a description tag written by Hans Never mann (*1), identifying it as being from the Solomon Islands Only one comparable hook, for merly in the Konietzko collection, could be found. Although identified as being from Choiseul, it is possible that it comes from a completely different par t of Melanesia (New Ireland or New Britain) T he ver y meticulously executed binding of the line to the shank, additionally covered by a 4 5cm long dense wrapping, was designed to make this hook, which was cer tainly baited, resistant to damag e or breakag e from a ver y substantial fish bite. T hat makes it safe to conclude it was used to catch larg er prey T he several millimeter thick tur tleshell shape r uns out to an ar tfully for med point

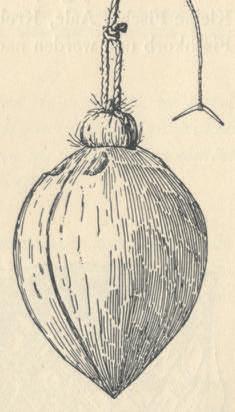

Fishing Floats on Ulawa

Beasley illustrates ver y ar tfully made f loats in the shape of a frig ate bird from the Central and Southeast Solomons (8): Pl CI T hey are decorated with Nautilus pompilius shell inlay, just like the stylized bird f loat here lacking the stone sinker. (29): 151.

Guppy’s remarks are interesting with respect to this: “It should be obser ved that these f loats are used to catch only f lying-fish, and that on account of their extreme shyness In the Solomon Islands f loats, on which the figure of a bird occurs (*2a, 2b, 2c), the line is wound round the hollow of the bird’s back and a projection below made for the purpose. For this the shape of a bird is cer tainly convenient, and the genius of those people leads them to or namented for ms ” (29): 151

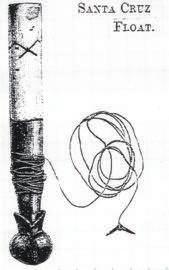

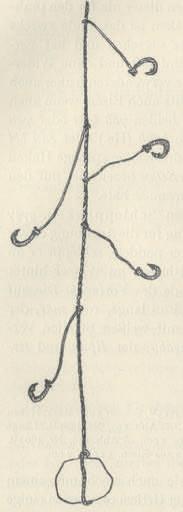

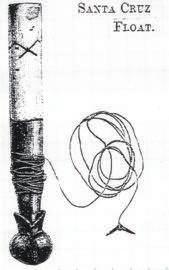

Illustrations of these interesting fishing devices appear in Codrington in 1891 (28): 317 and in Edg e-Par tington in 1890 (3): Vol. 1: 197, Fig. 2. Waite describes and illustrates the f loats collected on Ulawa in 1865: “Floats from the Santa Cr uz and Easter n Solomon Islands functioned similarly despite their different appearance. Both consisted of ver tical pieces of wood to the bottom of which was attached a stone weight tightly enclosed in a little net-like bag of strips of cane A long fibre line with a hook or g org e at one end was wound round the wooden shank of the f loat. In f loats from the Solomon Islands, the line could be fastened around the spur that projects from the nar row stick-like por tion of the f loat and might also be wound around the back of the car ved imag e Hooks were of pearl (*3) or tur tle shell.” (64): 56.

Ivens gives a comprehensive description of the f loats from the island of Maramasike just south of Malaita and the island of Ulawa east of Maramasike: “Flying fish are caught in the summer months, long wooden f loats with stones attached being used, twelve f loats for ming a line (5): 385, Fig a T he f loats are all different, and each has its name and its place in the line. T he tops of the f loats are car ved to re present birds or fishes or other objects, or a leg endar y person like Kar eimenu Kar eimenu is a hybrid human shark figure re presenting a shark spirit (a ver y similar figure in (12): Fig. 17). T he line is fastened round a boss just below the car ving, and is three fathoms in length T he bait consists of the f lesh of the robber

44

(*2c) (*2a) (*2b) aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 44

Pl 31

crab or of prawns ” (5): 385/386

Mead makes the following obser vations with reg ards to the Star Harbour area at the southeast tip of M a k i r a : “ F i s h i n g f o r g a r f i s h ( m a r o r e ) by t h e f l o a t technique in which a set of ten upright, wooden f loats e a ch d e c o r a t e d w i t h f i s h o r b i r d f o r m s a n d e a ch individually baited with small aigausu (g oat fish) or aiganafui fish is set in the harbour and allowed to drift with the wind In a demonstration that I witnessed a g arfish was caught within seven minutes of the f loat being set.” (65): 41

An Unusual Hook Or nament fr om the Solomons

T he exce ptionally beautifully shaped tur tle shell hook (*4) reminds one of Polynesian for ms. But the shell bead hackles, to which two dolphin teeth are attached at their ends, are more reminiscent of the southeast Solomons, where bonito hooks have similar shell bead hackles (compare plates 2123). According to Ivens, bonito hooks were used for ear piercing on Ulawa. He also writes of another use on the island of Makira in the southeast Solomons: “T he hole in the tip of the nose is a convenient place for car r ying a spare fish hook ” (5): 82 Ivens unfor tunately does not illustrate such a hook, so its for m can only be guessed at A drawing (*5) by Alphonse Pellion from 1819 is interesting in connection with this. It shows dancers on the Caroline Islands in Micronesia, two of whom are wearing fish hooks pulled through their right ear lobes T here is unfor tunately no fur ther infor mation on Pellion’s drawing, which is a unique document on the manner in which fish hooks could be wor n in Oceania.

The Unique Rennell Island Shark Hook

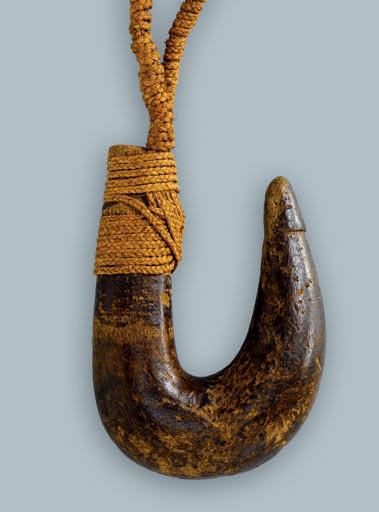

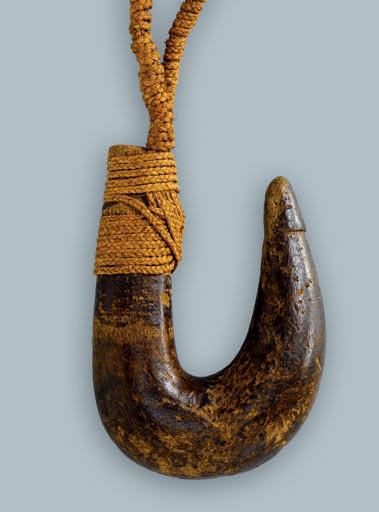

Like the small islands nor th of the larg er Solomon Islands, Rennell Island is considered to be one of the “Polynesian outliers ” Polynesian navig ators reached and settled these outer areas of the Solomons between 1200 and 1600AD. Where they found small existing g roups of people, they mixed with them, and the result was that many elements of Polynesian culture are manifest in these places Rennell and its smaller neighbour Bellona are the wester nmost outposts of Polynesia. Because its coasts are larg ely inaccessible, fishing played only a subordinate role on Rennell T he intimacy with the sea for which Polynesians are so well known is not present among the people of Rennell It is therefore not sur prising that only the monumental shark hook is known from there Even it, however, is rare in collections.

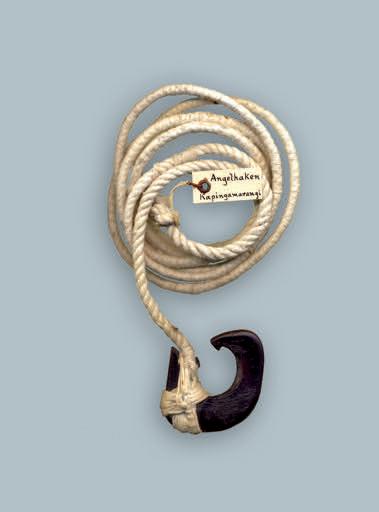

Both hooks on plates 35-35 show signs of much use and g reat ag e T he ver y ar tfully made sennit bindings had to be redone from time to time “Shark fishing was a religious and spiritual ritual. T he shark hook, Guan’akao, is an ar tifact of these Polynesian fishing rituals T he hook itself was tapu According to

(*5)

Pl 21

Pl. 22

Pl 23

(*4)

Pl 33

Pl 34

Pl. 35

Pl. 35

Pl 34

Pl 35

(*1) Hans Never mann (1902-1982) must be seen a s o n e o f t h e m o s t s i g n i f i c a n t G e r m a n ethnologists After his g raduation in 1924, he was active at the Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde f r o m 1 9 2 6 t o 1 9 2 8 , a t t h e M u s e u m f ü r Völkerkunde in Dresden in 1930 and 1931, and then ag ain in Berlin from 1931 to 1956 He was on numerous research expeditions, and is the author of countless publications about Oceania

(*3) Mother of pearl hooks are not mentioned in the literature

45

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 45

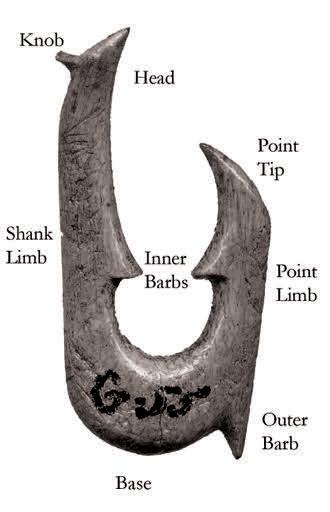

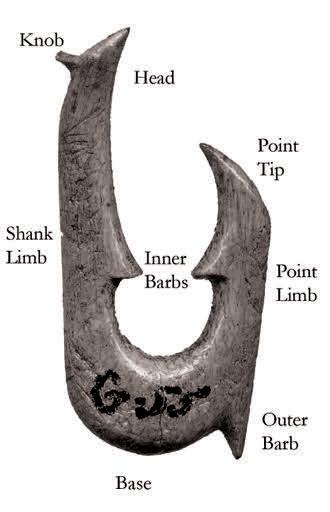

d’Obrenan on the voyag e of the Kor rig ane in 1939, “Fisher men took their places in the boat, leaving the centre seat free for a divine spirit; and special prayers were recited as the shark was bludg eoned to death ” (Quoted in Birket-Smith, (13): 7273 ) Birket-Smith says the following about the hook: “It is made of one piece and has a rather butt point, slightly f lattened and shouldered off from the rest of the cur ved limb, but without a barb T he shank limb is straight, ter minating in a knob and f lattened on the upper par t of the inside (*1) T he snood is of heavy sinnet wound around the shank in such a way as to for m two lashings se parated by a slightly projecting ledg e exce pt on the f lat inside of the shank where a her ring-bone patter n is produced. At the top the snood for ms a larg e loop with a seizing of somewhat finer sinnet ” (14): 71-72 Successful shark hunters enjoyed g reat recognition T hey hung the sharks’ caudal fins in their houses (14): 71 Kuschel illustrates an example with a thin plant fiber line beneath the somewhat offset point T his line was used to tie the bait to the hook (31): 74 Both hooks illustrated here show evidence of much use Small pieces of broken shark teeth are found embedded in the hard wood. Birket-Smith sug gests that shark fishing was abandoned with the introduction of Christianity, but was later resumed (14): 73

A rare Ruvettus hook from Nukumanu is illustrated on plate 32 Only its slender appearence and the ver y simple snood attachement distinguish it from those from Ontong Java

Four Bonito Hooks from Ontong Java

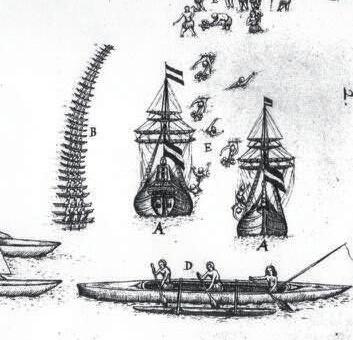

T he bonito hooks on plates 36/37 take us to Ontong Java, the nor ther nmost atoll of the Solomons, with a gig antic lag oon Only some 1500 people of Polynesian descent inhabit the over 100 tiny islands, which rise only a few meters above sea level. Parkinson writes: “In any case, the population of these islands comes from many different par ts of Polynesia, and consequently has characteristics in all respects which testify to its connection with faraway places.” (16):108. Plate X in Parkinson’s work (*2) clarify his statement It includes objects which show Melanesian and Micronesian inf luences as well One-piece hooks of identical for m to the one in Fig. 12 are known from Manus Island and from the Wester n Islands. T he Trochus shell hook from Nukumanu (*3) is also of this type T he hook in Fig 10 could be from the Micronesian island of Ponape and the hooks in Figs. 7 and 16 show evidence of being of Polynesian origin. Sur prisingly, the hook on Fig 17 appears in neither Beasley’s nor Anell’s monog raphs It is identical to the left hook in plate 38, which Parkinson unfor tunately mentions only brief ly, to state that it was used for catching smaller fish On account of its length and compactness, such a hook could have been useful for capturing larg er fish T he word “Choiseul” is written in pencil on the right hand hook. It is cer tainly possible that boats moving on documented inter-tribal trade routes between Ontong Java and the southeasterly Sikaiana atoll g roup might have g otten lost and reached Choiseul. So the hook could indeed be from there. A third ver y similar hook is in the American Museum of Natural Histor y in New York (Cat No:80 1/2228)

46

Pl 36 Pl 37 Pl 38

(*3)

(*2) aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 46

(*1) Pl 32

Parkinson incor rectly designates the hook, lower left in Pl X, as a shark hook T he misattribution can probably be traced back to Finsch (15), who describes a similar hook from the Ellice Islands as a shark hook

Even thorough research often fails to identify undocumented bonito hooks. T his is because there are many imprecisely identified examples in museums and the literature, and because only small details may differentiate hooks which come from areas ver y distant from one another, but which otherwise have a ver y similar overall appearance T hese details include the drilling of the point, the use of materials, and binding techniques T he four bonito hooks shown here can be attributed to Ontong Java. In an infor mative re por t published by MAN (*4), Lazar us, an inhabitant of the atoll, and Beasley, illustrate four two-piece hooks that also have the same kind of multiple stranded twined line as the examples shown here. Lazar us gives a detailed account of a fishing expedition. Excer pts from that account follow: “It is car ried out only in fine weather, and the fish caught are of three or four kinds, bonito called ( ) He-pa by the local people; secondly a kind of mackerel He-abo and occasionally a few Makobo along the reef-edg e on the retur n jour ney home ( ) T he canoe used was of a small type, plate D1, called Pan-pan and the crew on this occasion consisted of four natives, a small boy and the writer T he equipment was composed of ten long bamboo rods, He-makila, five shor ter ones and five sticks about 2 ft long also used as rods; a coconut leaf basket, 8 ft long by 1 ft dee p, with a rounded bottom and the top stayed out with sticks for holding the live bait was par tly submerg ed (*5) ( ) T he canoe proceeded outside the reef, where Mr Lazar us was instr ucted in the r ules of conduct for such an occasion, which included abstinence from talking, smoking and the throwing of anything overboard ( ) On sighting cer tain birds near the surface of the water, Hosivi (the headman of the canoe) g ave a shar p order and all paddled fast ( ) Seeing the bonito below he commenced throwing out live bait, one or two at a time and calling on his Kipua (in this case the spirit of his father) to make the fish bite ( ) After fishing for some time, the canoe pulled for the passag e in the reef, where, lifting the tabu on talking and smoking, Hosivi g ave a demonstration of the catching of Makabo No live bait was used exce pt on one small hook which was thrown out ag ainst the tide so that it would have sunk by the time it could have drifted level with the canoe. (...) On retur ning to Leueneuwa the fish - 50 in all (...) - were car ried to the house of the owner of the basket - the bonito first – and all laid across the bearer’s ar ms, which were first wrapped with a por tion of one of the centre leaves of a coconut palm. Hosivi shared them out to ever yone, including the owner of the house; the women then car ried them to the recipients’ houses, which in one case of one individual was the house of his prospective wife ” (213): 57/58 Beasley makes the following remarks about these hooks: “T he four hooks contained in the wooden pot, plate D3, are re produced in plate D2B, Kie-kawa or He p-pa Each measures from 8.3 cm to 10.7 cm and is provided with a strong thick twisted line, Hoo-wa, 19 ft long and of neat workmanship, having the ends tapering in the approved Polynesian style ( ) All the four hooks are strongly made, but lack somewhat the fine finish of those found fur ther east. All are constr ucted in exactly the same way, and were probably made by the same hand T he barbs are of strong

(*) T his ver y small bonito hook from the area of Ontong Java and Sikaiana differs from the Polynesian type in its slender shank and how the snood is tied on T he small shank head does not allow for the drilled hole A notch around the head allows for a secure fastening of the snood t o t h e s h a n k a n d t h e p o i n t T h e p o i n t attachement is fur ther stabilized by slipping fish bones under the line attachement on either side of the point A bunch of eight comparable bonito hooks (from Tobi and 3,5-5,5 cm long) is housed in the ethnog raphical Museum in Munich (Inv nrs 12-43-32 a-h)

(*5) Compare with drawing on pag e 207

47

Pl. 36 Pl 37

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 47

(*4) Four bonito hooks from Ontong Java illustrated in: MAN, Vol XXXVII, April 1937, Fig 2b

(

(*) Ruvettus fishing in the Ellice Islands (24): Pl 3, Fig 7

Pl 41

T he shank of one of these four hooks has a small g roove filed into the the shank head It therefore re presents almost perfectly the head of a small fish with eye and mouth (*2)

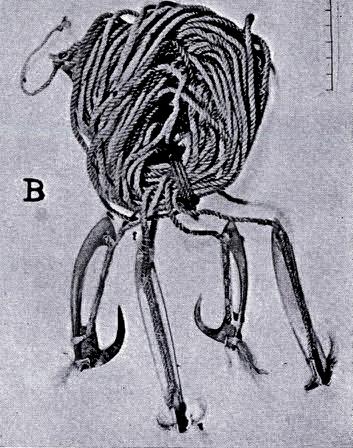

Beasley comments on the similarity of these hooks to those of the Ellice Islands to the east “It is obvious that similar types ag reeing even in small details must have a common source of origin ( ) Weighing up the evidence it becomes clear that Ontong Java has experienced more than one culture inf lux, and from several distinct and far-away localities ( ) ver y obviously these culture-elements have been introduced at different inter vals and over a long period. Most would be chance ar rivals by stor m blown canoes ( ) T he few sur vivors of one such canoe would have little difficulty in introducing new methods and customs among such a small population as Ontong Java is capable of suppor ting” (213): 59. Beasley also discusses the unique “domed wooden box koo-an on four shor t legs T hese boxes (*3) are no long er in use, and the specimen illustrated (pl D3) was obtained from the present chief Makaite, who had retained it as an heirloom.” (213): 59/60.

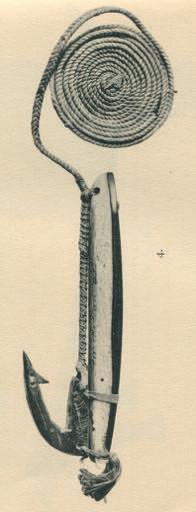

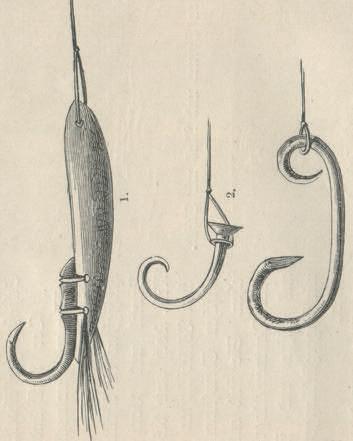

An Unusual Hook for a Dee pwater Fish, RUVET TUS PRETIOSUS

T he hook on plate 39 and those on plates 40 and 41 resemble the previous one in ever y detail It is a Ruvettus hook, a type widespread throughout Oceania, but most commonly known from the Wester n Pacific Anell cor rects several er rors made by Gudg er, and clearly distinguishes this type from shark hooks He gives exact infor mation on its distribution and occur rence in all the island areas of Oceania (19): 228-237 It is sur prising that Hedley was the first to describe this hook type in 1897 (20) Either it escaped the attention of earlier explorers, or it is a for m that developed late, like the New Zealand Kahawai hooks, which Cook would have obser ved and collected had they existed at the time of his visit, but which only begin to be documented in the early 19th centur y

Ruvettus Pretiosus, the Oilfish, is variously described in the literature (21): 258, (18): 211, (19): 229, (17): 38 It reaches a length of about 180 cm and a weight of 60 kilos, and inhabits waters between 200 and 500 meters in de pth T he fish is highly prized for its oily white meat, although its consumption has laxative effects.

Beasley’s statements

(*3) Along with a number of two-piece hooks, Sarfer t and Damm illustrate five ver y different wooden receptacles, all nonetheless ver y typical of Ontong Java and the neighbouring islands of Luangiua and Nukumanu (214): Ills 79, 80 T he authors also make the interesting asser tion that two-piece hooks were introduced by way of a canoe from Sikaiana “At the time Sarfer t was there, the people of Nukumanu still went to Sikaiana to obtain mother-of-pearl hooks” (214): 116

T he oil is used for medicinal pur poses On the Ellice Islands, according to Koch (17): 38, only the “designated master fisher men ” were able to manufacture Ruvettus hooks. For the V-shaped shank and the V-shaped point, they used the hard wood from the cr utches of the Pemphis acidula tree T he two pieces were bound tog ether with bast line in such a way that the point descended at a downward angle back towards the shank, and slightly to the side, so that the Ruvettus could take it Finsch describes the oilfish as having “wonderful larg e eyes ” that see ever ything, so that fisher men only ventured out beyond the reefs to catch it in absolute darkness and in a complete calm T hey baited the hooks with f lying fish sliced open and tied to the point and around a par t of the shor ter side of the shank (15): 258. Gudg er illustrates a hook on which the line for securing the bait fish is clearly visible (18): Fig 32 Few Ruvettus hooks in collections still have the stone

48 t u r t l e - s h e l l , w i t h t h e e d g e s n e a t l y r o u n d e d o f f ( ) ” ( * 1 f o l l ow i n g p a g e )

Pl. 39

Pl 40

Pl 67 * 1 ) T h e h o o k s s h ow n h e r e a l s o s u p p o r t

aktuelles hakenbuch 12.okt:miot neu vertikal 30.11.2011 18:09 Uhr Seite 48

(*2)