This exhibition invites you into a landscape of memory, woven from images, stories, and layered histories. It began as a return: a journey through sacred and storied terrain, where the weight of history is felt in the land itself. These geographies – desert, forest, canyon, and sky – became portals for remembering, for witnessing, and for making meaning.

What you’ll find here are fragments: photographs, echoes, and gestures, each shaped by the act of paying attention. Some carry silence. Others carry presence. All invite reflection.

As you move through the exhibition, we invite you to pause, to consider what surfaces, and to let your own experiences, memories, and connections rise. This guide offers one pathway through the work. It doesn’t explain so much as open.

Throughout the gallery, you may notice small invitations to respond. These are gentle openings.

You are welcome to engage now, later, or in your own way.

Traces is not fixed. It is a living, breathing space shaped by presence, yours included.

Thank you for being here.

Magalis Videaux / Artist-Curator

This exhibition, Traces: Witness and Trespass, does not move in a straight line.

It does not offer a tidy beginning, middle, or end.

Instead, it breathes –unfolding like a palimpsest, where memory, silence, and encounter bleed through one another in layers that refuse easy separation.

It invites us to step into a living archive: one that carries the imprint of many times, many bodies, many ways of seeing.

At the center of this exhibition is a practice, a way of moving through the world that Bill Graustein has cultivated over decades, sometimes consciously, mostly intuitively. His photographs are not static images captured in time. They are portals to discovery of hidden meanings. Each frame holds traces of presence, absence, longing, rupture, and return. Each image is a threshold, asking not just to be looked at, but listened to. The work resists finality. It insists on motion, on reverberation, on the impossibility of a single story.

In curating Traces, we lean into frameworks that honor the layered, nonlinear, and decentralized nature of memory and land. We draw from the sensibility of spectral traces: the understanding that what is present is inseparable from what is absent – that landscapes themselves carry grief, resistance, and dreaming.

We move with the understanding that memory does not grow in straight lines. It weaves underground like roots searching for water, tangling, touching, crossing

unseen. Stories, like roots, do not follow a singular path. They reach outward and downward at once, sensing, connecting, remembering what the surface forgets. In this way, memory becomes not a timeline, but a living web, breathing, branching, endlessly becoming.

Bill’s journey as a photographer mirrors these organic, relational structures. His early encounters at places like Hell Gap in Wyoming set the stage: moving from intellectual curiosity into a slow, somatic listening to place. Over time, his practice evolved from documentation and toward participation. Away from mastery and toward humility. Away from mild observer and toward reverence. This evolution is not a quiet backdrop to the exhibition; it is the exhibition. Traces offers a map not of places visited, but of a practice evolving a long witnessing that becomes, itself, a living story.

Central to this exhibition is the tension between witness and trespass. Photography carries a privilege, a gaze, a weight of history that cannot be unacknowledged, especially when moving through Indigenous landscapes, sacred sites, and communities shaped by colonization. Bill’s photographs carry this awareness not through overt declarations, but through gesture: through the taking off of shoes at the Whitney Plantation; through the quiet gravity in the image at San Luis; through the openness to being shaped, challenged, and changed by what was encountered.

The work asks: How do we see without consuming? How do we witness without claiming? How do we let the land, the ancestors, the spectral memories speak even if their language is unfamiliar to us?

In this exhibition, we invite multiple ways of knowing, feeling, and remembering to coexist. We honor what is revealed and what remains hidden. Some histories cannot be fully told. Some wounds cannot be fully seen. Some beauty emerges only

through the cracks. And so this exhibition holds space for opacity, for mystery, for the unfinished, inviting each visitor into the shared act of meaning-making.

To navigate Traces is to move through a living palimpsest. Some paths are clear; others are obscured. You are invited to read not only what is written but what is erased, what is muted, what is struggling to be heard. You are invited to notice your own body’s reactions – what makes you pause, what stirs your grief, what ignites your longing. You are invited to dream of futures where story, land, memory, and spirit are honored in their fullness, their plurality, their sacredness.

Ultimately, Traces is not an exhibition about closure. It is not about arriving at a single understanding. It is about entering into relationship with the land, with the ancestors, with our own fragmented memories and unfinished reckonings. It is about surrendering the idea that we can know everything, and instead embracing the sacred work of listening.

This is a map of the unseen. A song of the remembered and the forgotten. A call to witness not with the eyes alone, but with the whole body, the whole heart, the whole spirit.

May you find your own echoes here. May you leave your own traces. May you remember what your body has not forgotten.

This photograph was taken on the final evening of a six-day backpacking trip through the Grand Canyon in 2000, along the trail between Indian Garden and Plateau Point.

I was drawn to the profile of Redwall Limestone, the sharp texture of the outcrop, and the quiet presence of the rising moon. I took the picture quickly, without much forethought, simply because something in that moment captured the feel of our days the canyon and asked to be witnessed.

At the time, I didn’t know what the image would become. I only knew that the moment felt whole. Years later, I came across a quote by Brian Andreas on a greeting card that echoed that same feeling: “I’ve always liked the time before dawn, because there’s no one around to remind me who I’m supposed to be, so it’s easier to remember who I am.” Those words stayed with me. They spoke directly to something I’d felt out there in the Canyon, something I’ve felt often in the wilderness, but hadn’t named.

The Grand Canyon is a place of deep time, layer upon layer of rock that has held memory longer than we’ve had language for it. The Redwall Limestone, with its resistance to erosion, forms a cliff that encircles the inner canyon. It’s one of those layers you see from anywhere in the canyon, anchoring you in time and place even as the trail shifts beneath your feet. That evening, surrounded by vastness and silence, I felt both small and held.

This is where Traces begins: not with a shutter click, but with listening. Listening to the breath of the canyon. Listening to the hush of ancestral memory. The camera becomes a portal, a way of noticing what lingers just beyond visibility. A gesture of witness. Each photograph in this collection holds a question I couldn’t answer in words. They are my way of staying close to something sacred and unfinished.

In the time before dawn, I walk into the land without announcing myself, asking permission in a language that isn’t spoken out loud. The camera does not lead me. My body does. Sometimes I move slowly, almost reverently. Sometimes I pause so long it feels as if I’ve become part of the stone or the shadow. It’s not about taking a picture but about being available to the conversation the land wants to have with me.

Cliff and Moon Grand Canyon, Arizona 2000

Verse by Bryan Andreas

I parked at the trailhead by the visitor center, busied myself with going over my checklist for the umpteenth time, focusing on assembling all the stuff I’d need for a three-day hike, excited and anxious.

Finally, everything is as ready as it’s going to be. Swing the pack up, cinch the waistbelt and step out on the trail heading upstream along the creek. The physical rhythm of the hike started that moment, but the transition to the mental and spiritual journeys was gradual and continuous.

The trail easy to follow, the smell and cinnamon color of the ponderosa pines, familiar. Creek burbling. Not getting back in the car today or into a bed tonight. After a couple of hours, start looking for a campsite. None marked on this trail. Just find a place. No guidance. This is a new feeling. I pick a spot, throw down a tarp and pad, unroll a sleeping bag, and set up a tiny stove. The busyness of making camp occupies me. Eat, clean up, ready for bed.

So. This is what alone in the woods feels like. I know where I am. I feel safe. At the same time I’m disoriented. Takes a while to fall asleep.

Wake occasionally during the night. Creek is still burbling, wind still sighing in the trees. The wilderness is still in progress. I’m just a visitor and witness. Wake up to a new day. Go about the routine of breakfast and breaking camp. Swing the pack up again and back on the trail that now feels a little less foreign than the afternoon before.

Come to the junction, turn onto the trail that leads up out of the canyon. Seeing and feeling the changes in the land around. Slow the pace, no sense pushing too hard against the climb, altitude and weight of the pack. The slope is cool and shaded by the canyon wall, the forest thins as I reach the plateau. Walk into a glade where the sunlight and shadows paint striking patterns on the forest floor. Drop the pack, set up the tripod and camera, mount the lens, get out the focusing cloth. The sun and shadows have shifted enough in the time it took to set up that it’s not even worth clicking the shutter. Eat lunch, pack up the camera, and move on. Clouds gather. Take a short break, breathe deeply, check the map, back on the trail. Start to feel like I’m in the landscape rather than just on my way to a destination.

The trail follows down the gentle slope of the Pajarito Plateau. Pine parkland gives way to scattered pinyon pines and junipers. The open spaces between them are on a human scale – both open to the sky and separated from each other. By the time I reach the area I’d planned to camp, a light rain has started. Hmmm, this doesn’t feel so promising.

In one of the open spaces a ring of stones surrounds the weathered figures of two crouching mountain lions. The figures were carved in the time before contact with Europeans. The ceremonial life of many Indigenous peoples continues to be rooted in this place. Outsiders are permitted when the tribes are not in ceremony, and unwelcome when they are. This place looks as it did in photographs, but it feels different than I could imagine, and different for having walked ten miles through that landscape to get here. Different, too, for the ring of elk antlers, which, I guess, indicates that it is close to a time of ceremony. For the next hour or so, I move around, feeling my way into relationship with this site, aware that it has been a place of ceremony for more than 500 years. When the rain stops, I set up the camera in the spot that feels right.

I move a respectful quarter mile away and set up camp again, make a quick side trip down the adjacent canyon to get water, eat supper, watch the sky clear and the full moon rise over the mountains. Sleep peacefully under the stars.

Break camp the next morning and set out on a different trail back to my car. “Glorious” becomes a complete sentence. With a view across the Rio Grande, I stop midday and rummage through my pack for crackers and a can of sardines.

One sensory memory from the trip that is easy to communicate is the aftertaste of those sardines lingering for the next three hours of hiking. So vivid and incongruent is that aftertaste that I have not eaten another sardine since that day, September 28, 1985.

Other changes from that trip have been more subtle, more personal and much harder to describe in words… so I leave it to you to develop your own relationship between this image, your memories, and your imagination.

Jeanie and I met on the Hell Gap archaeological dig on a cattle ranch in Wyoming in 1965 (more of that narrative appears in the Photographer’s Statement). That summer quickly became our standard for an “immersive experience”.

Part of the experience was intellectual - what could we tell about ancient hunters from the debris of animal bones and stone tools that we uncovered in their campsites?

Part was imaginative – we lived through the same flow of the days, vagaries of weather, and stars at night as the ancients had.

Part was sensory – it evoked awareness that bypasses words and sticks deeply in memory – from the smell of the sagebrush in the cool of the morning to the rattle of the dry grass in the afternoon breeze to the sudden assaults of thunderstorms.

Part was mysterious – we felt the connection to the humans who last touched the bones and stone tools we uncovered 10,000 years ago, and connection to Creation itself. Each of these ways of knowing was an entry point to comprehending the natural world and our relation, as human creatures, to it. We experienced each of these ways vividly that summer; they became reference points for a relationship that deepened over five years into marriage.

Turning her attention to living Indigenous people, Jeanie spent a year as a VISTA volunteer on the Turtle Mountain Reservation. In the year before our wedding, she was enrolled in an M.Ed. program for former VISTAs. She did her student teaching in Shonto, Arizona, in the northwest corner of the Navajo Reservation, about ten miles from the Betatakin cliff dwellings.

While she was teaching, a group from the school visited Betatakin. Jeanie was immediately enchanted by the scene. She insisted we make a detour on our honeymoon so that I could experience a sense of the place that so captured her imagination and her spirit.

In preparing this exhibit guide, I think I’ve discovered why Betatakin so enchanted Jeanie.

The lives of the people at Hell Gap 10,000 years ago were harsh – their camps were simple, they had to move often to follow game, and their hunts were exciting and terrifying – they stampeded 2,000-pound bison towards their campsite. A nice place to visit, but we wouldn’t want to live there.

The 700-year-old ruins of Betatakin, however, evoke more appealing visions: a small village in a sheltered alcove in the midst of a harsh and beautiful landscape. The ancient people captured her imagination – keen observers of the

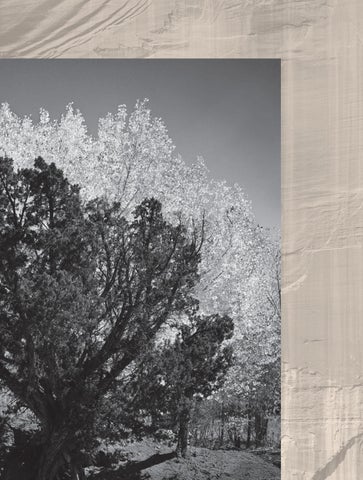

Navajo National Monument Shonto, Arizona 2019

natural world, sophisticated in their understanding of how meet their needs with what little that landscape offered and how to pass their way of life on to their children

Jeanie’s imagination embraced this more welcoming vision. Following that imagination led her to develop a groundbreaking environmental justice program for her church, helping parishioners see themselves as inhabitants and stewards of a continuously unfolding Creation.

Enchantment, of course, does not need to have an explanation to be real.

In his television series a few years ago, Ken Burns reminded us that all of us who pay taxes are the owners of the National Parks.

To check out the condition of our property, some friends and I took a few days for a walking inspection the Grand Canyon.

Backpacks bulging, we approached the rim, looked into the immense space surrounded by rock, paused, then wondered, “How can something so vast be so silent?”

The trail dropped us slowly through lessons in earth history I’d read about in texts. Now I could reach out and touch the solid pages – ancient sea bottom, mud flats, sand dunes.

We descended a few hundred million years then turned right, sometime near the middle of the Cambrian period, onto the Tonto Trail - a narrow, lightly worn track full of detours - large ones that swung into shaded side canyons and out to promontories high over the riverand small detours to avoid the spines of prickly pear and blackthorn bush.

Out attention turned from rock to water. We found only seeps. Everything that grew around us had learned how to drink less often and live on less water than we needed.

The third afternoon, at the edge of the shadow of a cliff, languid pools linked by shimmering films of water moistened the sandstone. Past and present seemed to merge – the rock is the remains of an ancient beach at the edge of our continent.

I closed my eyes and imagined the surges of waves climbing the shore; opened them to see a small plant flowering where it had found water in the desert – water that we gratefully drank.

We slept on the rock of this ancient beach. When I woke, the languid pool had turned to gold, reflecting a red cliff lit by the rising sun.

It wasn’t until I turned away from that scene that I saw the fossil trilobites in the rock underneath me, the remains of extinct creatures who had their day at this beach 500 million years ago.

Like them, we were just passing through.

Owners? Hah! We aren’t even paying rent.

Grapevine Creek Grand Canyon, Arizona 1989

September 1992. I’ve been coordinating my mother’s care for two years. Her mind is sharp. Her death is inevitable, but not imminent. There’s enough time before her passing for me to take several days away to attend to my grieving – grieving the loss of her and for the loss of the conversations we’ll never have about the events that shaped her life, events of which I know very little. I plan a short backpacking trip in New Mexico for retreat.

Driving back to Albuquerque and the airport after three days of contemplative solitude. There’s a sign at a turnoff: San Luis. I’ve wanted to see that village since I’d gotten stuck in the mud trying to get there 25 years ago. The road sign becomes a door – one I can pass by or choose to enter. Five miles of dirt road, I arrive in San Luis. The place is nearly abandoned: adobe buildings melting into the desert, vacant windows, rusted cars, no movement, no sound. Only the church stands in good repair, behind it, a camposanto with a solitary grave – that of Esequiel Dominguez – and a vista of the landscape I’d inhabited and studied decades ago. Looking around and seeing no one to take offense at my presence in the camposanto, I set the camera on its tripod. The moment is quiet, dignified, and peaceful.

This place and this moment embrace me. This landscape holds deep time along with human traces. In graduate school I returned here to collect a chunk of the rock that caps Mesa Prieta, the landform in the left background of this picture. I took that chunk of it back to the lab, disassembled it, made some arcane measurements, and determined that it had formed two and a half million years ago. That rock and that mesa have seen 700 feet of sandstone and shale below them removed by erosion since then. I see the landscape still in motion, still becoming. The human stories are also part of that continuum of becoming.

Shutter clicks. An SUV pulls in behind me. Uh-oh. Many Spanish villages in this area don’t take kindly to Anglo visitors.

As I feel a surge of fear at having been caught intruding, a woman, Renee Candelaria Fletcher, gets out of the SUV. She is welcoming. She had lived here with her father 20 years earlier and she carries stories of four generations of ancestors who made their living off this land. She had driven from Albuquerque with her brother and grandchildren to see what has become of the village

that raised her and show it to her grandchildren. I tell her I’m fearful that I might be intruding. “No, I’m glad you’re recording this place because it won’t be here much longer.” She muses: “I wonder if Esequiel Dominguez is still living here?”

We are here with the same intent: to see and witness a landscape that had shaped us, albeit in very different ways, and to honor those who have passed from it.

We exchange addresses, I send her a print of the picture, we don’t meet again, and soon lose touch.

Last fall, as I started to plan this exhibition, I recognized how much Renee’s words have illuminated what, for me, is the often murky boundary between witness and trespass. I wanted to reconnect with her and acknowledge with gratitude the significance her words have held for me. I couldn’t find a link to her online, but did find her son Harrison and reached out to him. Harrison teaches creative writing at Colorado State; he has published memoirs about his mother’s family and their connections to the land and its history, and, most compelling for me, about his mother’s determination that he understand the depth of his roots and how those roots penetrated the landscape and history. He told me that his mother kept the print that I’d sent her thirty years ago and hung in her living room. Some years later, he asked her where the photograph came from; she did not remember.

To recognize, through chance encounter, that the piece of art that I’d made as a way of working through my grief, has now been held by two generations, reminding them of their connections to land of their origins, amazes, gratifies, and humbles me.

Bill

This image marks a pivotal moment in Bill’s practice. As our conversations deepened throughout the shaping of this exhibition, we came to recognize it as a turning point, a shift from capturing a photograph to being fully present for one. From seeing himself as an intruding observer to becoming an intentional witness. It is graphically compelling and profoundly resonant, carrying ancestors, layers, and stories that can never be fully told.

This past February, I visited San Luis for the first time. For Bill, this was a return. We stood there quietly taking in the moment with the Cabezon Peak rising in the distance. It felt like stepping into a dream woven from memory – a place where the land speaks in fragments and invites quiet listening. Bill recalled what he witnessed in 1992, when he first captured the image. San Luis had changed, he said. Where once there had been a single grave, there were now many, lovingly tended and remembered. What had resembled a ghost town now felt like a place slowly learning to carry its past with care.

This piece is one of the anchors of Traces. Not because it’s definitive, but because it’s porous. It holds memory, grief, trespass, beauty, and transformation. It looks forward and back. It reminds us that landscape is never just background, it’s a participant, a witness, a keeper of story.

To the viewer: I invite you not only to look, but to listen. Like backpacking, this exhibition offers an experience that is both solitary and shared. You carry what you need. You walk your own path. And still, the trail is communal.

M agalis

The summer before my senior year in college I worked on an archaeological dig in New Mexico. The formal title was The Anasazi Origins Project, but the crew of the dig just called it Armijo, after the rancher who had built the only two structures within miles – a small stone cabin and a simple dam across the head of a broad canyon to catch runoff and water his cattle.

We turned the cabin into a kitchen and lived in tents on a narrow rock bench that overlooked the canyon. The only way to get there was to follow the two-rut track the rancher had worn.

My job wasn’t digging; it was reading the land. I was studying the geologic processes that had shaped the world where the ancestors once made their living. I was looking for evidence not just of people, but of the effects of wind, water, and time. I’d learned some geology through books and lectures; now the landscape taught through its presence.

Dust devils spun through camp, strong enough to knock you sideways. The wind could lift sand low into the air and send it stinging across your legs. The downpour from one thunderstorm sent a sheet of water across sloping land carrying sand, mud, branches, and rattlesnakes into the pond behind the dam, and making the ranch roads impassable for days.

The storm passed and the weather had stilled by sunset. After dark, a chorus of frogs, brought from their burrows by the rain, echoed through the night, punctuated by the occasional bellow of a cow. The landscape softened in the starlight.

I slept under the stars almost every night, the cycles of the moon harmonizing with the rhythm of the days. The land was teaching me how to live inside its time, not against it.

After the flood, the survey crew – those looking for other sites the ancients had inhabited – were stuck in camp until the roads were passable. I had a four-wheeldrive pickup, so, after a few days of drying sun, I was volunteered to take the crew up toward San Luis. I’d been warned to be careful. I stopped to check the surface ahead each time the road crossed an arroyo, testing to see if the surface was dry and could hold my weight.

A broad swale passed that test, so I gunned the engine, built momentum, and . . . sank over the front axle in the gooey mud just below the dried surface. Wrong test. Five miles from camp. No shovels. Nothing to fasten the winch to. Just hands to scoop mud from under the truck.

Draped over the front wheel, scooping or on my belly doing the breaststroke in the mud, I began to recognize my lesson for the day: to survive in this landscape, one needed to be a much keener observer than I.

That day, we christened my green pickup The Slick Pickle. The ceremony consisted mostly of anointing it with mud while cursing as we dug it out inch by inch, covered in clay, merging with the landscape. The photo in the centerfold was taken about halfway to getting unstuck.

It took me 25 years to make it to San Luis. By the time I got there I’d come to understand that traces aren’t always things we leave behind; sometimes they’re what the land leaves in us. That we are not separate from what we observe, but part of it. That the land initiates novices on its own schedule. That there are always more traces to discover.

Beginning on May 20, 1999, more than 200 Jemez tribal members walked from the plaza of Jemez

New Mexico Alliance of Health Councils, 1999

In 1999 my faith community offered a retreat, titled “Emerging Ministries” in Greenfield, Massachusetts over a weekend in May. At the time I was grappling with choices about the direction to take in my work, but the title initially put me off – it felt too pretentious to describe what was nagging at me. The rest of the description, however, seemed a good fit – for me, the working title became “What the heck are we going to do next?”

Dealing with a Friday rush hour on I-91 didn’t feel like a good way to prepare for the retreat, so I took two days to bicycle up to Greenfield. The piles of paper on my desk and distracting to-do lists were soon out of my attention.

When I got to the retreat, we first met in a small group and were given no instructions. One person suggested that we share the reason we came to the retreat and began speaking. She stopped about a third of the way through and said, “Why don’t we pass it around and each take a turn starting their story?” As each person spoke, they picked up on the threads others had begun, and by the time we’d gone around once, I realized we all shared something deeply similar: We had all been through difficulties or wounds of one sort or another, we had all done work of healing, and we were all wondering if our healing was complete enough to be at the center of the next chapter of our work.

As it turned out, I didn’t need to go to the retreat to understand that theme. A photograph in the newspaper the morning I was leaving on my bike caught my eye – I recognized it as New Mexico. The story was of a much larger journey of healing that was underway – the remains of nearly 2000 individuals were in transit that day from a museum in Massachusetts to their ancestral home of Pecos Pueblo in New Mexico.

Pecos had been so weakened by colonial conquest that its population had dwindled from more than 2000 to 17. Those 17 had abandoned Pecos in 1838 to live with the only other pueblo that spoke their language. The ruins of Pecos were excavated by an archaeologist in the 1920s and nearly 2000 graves were uncovered and the human remains removed to Massachusetts.

On that day as the remains were being carried across the country in a semi trailer, the descendants of Pecos, now numbering several hundred, were walking for three days, following their ancestors’ path of exile, to return to their ancestral home and welcome the remains of their ancestors with ceremony.

More pieces of that story kept dropping in front of me over the next months and years, filling out a picture of how the return had touched individuals, families, communities and the larger levels of society. The next year I made a detour to visit Pecos, to experience the echoes of the past with my own senses and to try to capture some of those echoes on film. The photograph of the remains of the mission church, Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles de Porciuncula, is the only image in this exhibit that is the product of such intention.

The more I learned of the history of Pecos, the more I could recognize how past events still echo to this day. As significantly, my ears began to be more tuned to picking up threads of the echoes of harm, the labor of healing, and the yearning for repair, in conversations around New Haven. As the breaking story of Pecos shaped how I made meaning out of the emerging ministries retreat, so the growing understanding of that story shaped how I tried to make fabric out of those threads of local conversations.

Starting the Community Leadership Program (CLP) in 2002 was a consequence of this learning. I heard many New Haveners speak of wanting to work more across boundaries for the common good and wanting support in building relationships that could withstand the challenges of such collaboration. I took from the story of Pecos that we, as leaders of CLP, needed to create a space that

allowed for the work of healing to begin or progress. As we leaned and learned into the work of developing CLP, I came to see how the work of collaboration requires the work of repair at both the individual and group level. The story of Pecos contains the elements of the work of repair on a grand stage.

New York Times, National Report, May 20, 1999

In what experts believe is the largest-ever single return of Indian remains, the bones of nearly 2,000 Pueblo Indians set out for home today. At 7 this morning, a 53-foot semitrailer loaded with boxes of skeletons began the long journey from the Peabody Museum at Harvard, where the bones have been stored and studied for more than 70 years, to the ancient Pecos Valley site in New Mexico whence they came.

Park Display

Pecos National Historical Park

Pecos, New Mexico

February 2025

Standing before the remnants of the Pecos mission churches, I was struck by the layers of presence and erasure.

The stone outlines of the 1625 church and the surviving 1717 walls gesture toward a longer and more complex story than the official sign allows. A story not only of architectural evolution but of forced transformation: cultural genocide, displacement, and spiritual imposition.

Someone had written directly onto the official signage, urgent and insistent markings not meant to be there. The words cut through the polished surface of public memory, interrupting a narrative that focused on architecture, dates, and missionary presence while leaving the deeper violence unnamed. The sign told one version of history; the handwriting exposed its omissions. This small act, an unsanctioned correction, became a form of testimony. A refusal. A trace of what endures. A rupture, subtle and undeniable, emerged, a presence pressing through the cracks of the sanctioned narrative, echoing what history so often tries to bury.

This site, like many others across the Southwest, holds more than ruins. It holds memory that resists containment. It remembers what the language of preservation often forgets: that colonization was not just a historic moment, but a wound. One that still shapes the land, the descendants, and the stories told about origins, salvation, and belonging.

The image speaks louder than the plaque. It shows how even formal attempts at remembrance can become palimpsests: layers of truth, omission, and quiet correction. It raises questions. Who decides what stays visible? And who continues to speak, even when the official story has already been written?

In this land, voices remain. In stone. In silence. In the urgency of handwritten words left behind like offerings. Traces is a practice of listening for them.

Chinle, Arizona 1990

Around 2000, the pull toward working with people and groups began to feel more urgent than my previous, relatively solitary, habits.

With that shift, I felt the urge to pick up a camera less and less frequently. One occasion, however, unexpectedly reactivated my practice, and moved it from what I did as a break from my ‘work’ to what I did as a part of my day job of engagement with others:

Two organizations shaped that season: the Community Leadership Program (CLP), which I helped launch, and Public Allies, where I served on the board. Though their structures differ, they feel like cousins in the same extended family—rooted in a shared purpose: nurturing the capacity to lead collaboratively, inclusively, and in service of the common good.

A few years ago a reorganization effort within Public Allies went badly off the rails; trust between individuals and between different parts of the organizational network was broken. When such events happen it’s a board’s responsibility to step in. I think we had 20 board meetings in 30 days to manage the crisis and stabilize the organization. Within a year, Public Allies was stable and back on course, but the turmoil had left lasting traces of hurt and broken trust.

As a step towards rebuilding trust and increasing the capacity of the team to work through difficult decisions, the board and senior leadership made a corporate visit to the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana, a plantation that has been turned into a museum curated from the perspective of the enslaved.

We met as a group over breakfast to prepare for the tour and the strong emotions encountering that history might evoke. At the end of the meeting one of the members of the board said, “If something catches your attention, or emotions rise up, take a picture of the scene with your cell phone and send it to me, so that we can look at them all together.”

On the tour we stopped at a jail that was built after Reconstruction to replace whipping as a means of maintaining control. When I stepped into the cell I tried to imagine what it was like to be confined there. I took off my shoes to feel the floor and experience the cell with more of my body. The shadow of the door made a striking pattern on the floor. My practice of photographing was reactivated, but now in the company of a group rather than in solitude.

— continue —

If I had been my myself, it would have been an easy decision, an echo of past encounters with traces of past times, to go barefoot. Here it felt more awkward – would others see it as performative, trespass on sacred ground, self-centered…?

I’ve come to think that the boundary between witness and trespass is seldom precise and clear; it evolves as the consciousness of those involved changes. The only way I know to place the boundary is to experiment with crossing it mindfully, and to ask for forgiveness if needed.

In addition to the objects from its past, the Whitney Plantation presents works of art inspired by its history. There are also a series of stone monuments engraved with the names of those who had been enslaved. Walking along the long rows of monuments was… don’t wait to find words, pick up your phone. The monuments were polished; distracting reflections were much more evident to the camera than the eye. Well, can I move around so the reflection becomes part of the picture. Oh! This is it.

The building in the background is the church that freedmen built during Reconstruction; the blurry figures in the middle are the senior leaders of Public Allies. This is one image where historical perspective seems reversed: the record of the past is clear, but the people present now, and their choices that will shape the future, are indistinct.

I now understand that part of our work that day was to increase our capacity, as a group, to recognize and hold each other’s individual reactions when encountering difficult traces of the past. So that, rather than reacting, we can pause and discover what emerges when we hold together the breadth of our experiences. So that we see more clearly what is at stake in this moment — for each of us as individuals, for the organization we steward, and for the communities we serve — as we prepare to choose the path forward.

Erik Clemons

I love the name of this exhibition, Traces, because it’s true.

There are traces of Bill not just in these images, but in all of us who’ve had the privilege to walk beside him.

Those of us he’s mentored, partnered with, challenged, encouraged: we carry his fingerprints, his questions, his generosity, his stillness, and his peace within us.

There are many more he’s touched who aren’t named here, yet hold pieces of him just the same.

When I look at these photographs, I don’t see finality. There are no periods. No "The End." These images are portals. They are beginnings. They are layered with silence, memory, and time - and they invite us not just to look, but to listen. To slow down. To feel what is rising in us as we stand before them. They allow us to discern the profane from the sacred.

Some of these photographs were taken decades ago — some as far back forty years. But they are alive today in a different way because Bill is not the same man who took them. And that’s what moves me. I asked him recently, “Do you think the images feel different now because you’re different?” He paused, nodded, and said yes. And that’s what I carry into this exhibition: the understanding that what we see is shaped by who we are — and that transformation gives us new eyes.

These landscapes - the Grand Canyon, the Pecos ruins, the cliffs of Canyon de Chelly - they are more than scenic beauty. They are sacred ground. Bill didn’t just pass through them. He received something from them. And I believe, in turn, the land received something from him. There is something protective in these images, something spiritual that guards what’s been captured, and at the same time, calls us to interrogate what we think we know and who we thought we were.

This work is not a program. It’s not a curriculum or a strategy. It’s not coming from a place of control. It’s an offering. And that, to me, is one of the most courageous things I’ve ever witnessed. Bill, who for years has shown up as a leader, a systems builder, a mentor, is now showing up as himself. Whole. Unordered. Vulnerable. And that takes courage. It takes spirit.

These photographs make space for grief, rage, beauty, and revelation. They’re not loud. They don’t shout. They whisper something deep. Something that makes me still. They’re beautifully haunting. They

ask: What are you missing? Who are you forgetting? What’s being said that you still haven’t heard?

My hope is that this exhibition becomes a space not just for viewing, but for reflection. I imagine a corkboard, a notebook, a sacred space where people can leave their own traces — their memories, their offerings. Because what Bill has given us isn’t just a body of work, it’s an invitation to show up differently. To show up wholly. To speak the unspeakable. And to listen to what we didn’t yet know we needed to hear.

Bill once called this a vanity project. But it’s not. This is not about ego. This is about vision. This is about a man showing up with his whole self and inviting us to do the same. These images are not static. They are dynamic. They are alive. And they are generous.

In them, I see Bill. But I also see myself. I see us. I see the sacred.

And I see the road that chose us.

County Road Price, North Dakota 1987

Bill Graustein

“The image educates where reason never reaches.” - Dorothea Blom

Near the end of my first year of college, I signed up as a laborer on an archaeological dig. A few weeks later I was sitting in a hole in the ground in Hell Gap, Wyoming, holding a mason’s trowel and scraping away silt, millimeter by millimeter. The crew of about 30, mostly college students, was camped in a grassy valley, separated from the Great Plains by a narrow, craggy ridge of granite that reflected the heat of the afternoon sun and turned my hole into an oven. Ten thousand years earlier, bands of hunters camped in this same place. We were uncovering the debris they had left behind: bones of animals they had eaten, stone tools and thousands of flakes of flint left from making those tools. From these fragments, we tried to piece together some understanding of their lives and what remained of them at the abandoned ancient campsites.

After a few weeks of finding nothing, I hit upon a bit of bone. I scraped and brushed the silt away until the full three-foot length of a bison rib appeared. The rib had long scratches on it where the meat had been scraped away. The next day I found a fist-sized piece of flint with a sharp edge. The serrations on the edge of the flint matched the spacing of the scratches. The last person to touch this rib and hunk of flint ate their dinner here 10,000 years ago. That recognition abruptly stretched my mind into a whole new dimension of time and of awareness of what had happened in this space that our crew was now inhabiting.

I fell in love with a geology course that fall and 1. switched majors; 2. signed up with the same archaeologist to work on another project, Armijo, the next summer in New Mexico; 3. spent the next eight summers doing geologic field work the west; 4. started a career in research to understand the invisible forces that shape the landscapes and environment sustain us; 5. lived happily in my left brain and 6. married Jeanie McCarthy, a young woman on the Hell Gap crew. I was only dimly aware of how deeply that landscape had imprinted itself in my body as well my mind.

When I turned 40, the more hidden parts of my mind started to demand attention. One day during a particularly dreary and dispiriting February, I felt a pull from the western landscape. Seemingly out of nowhere, it came to me take up photography again, this time with a 4x5-inch view camera, and to take a backpacking trip to immerse myself in the landscape and see what it might offer.

Scenes appeared seemingly asking to be photographed. Emotions that had seemed inaccessible came into focus, first on the ground glass and then in the darkroom.

For the next 20 years, I would carry that big camera with me when I traveled, as an incentive to slow down and pay closer attention to what was around me, or to capture what might suddenly grab my attention. When I encountered something that excited that part of my mind that doesn’t use words, I would stop to photograph.

A practice emerged from the doing: first, having an intention to set aside some time for being in an unfamiliar place; paying attention to how any of my senses might respond to the place; and noticing over time what feelings, words, or insight might attach themselves to the image of that place.

Last winter, several of the images I had captured decades ago unexpectedly kept raising their hands and asking for more attention. In a casual conversation last summer, Magalis told me of her artistic practice and of the idea of spectral traces: lingering, often intangible, remnants of the past, such as memories, histories, or presences, that subtly shape our present. That notion immediately helped me organize my images and begin to understand why they had kept coming to mind. Soon after, Magalis and I agreed to collaborate to design and curate this exhibit.

In the process of curating this set of photos for this exhibit, events coincided in unlikely to utterly improbable ways to illuminate connections. Magalis and I share the sense that many of these connections are significant not solely for us as individuals, but also for the communities we touch. The metaphor of uncovering the bison rib resonates with us. The more we dig, the more we come to grasp the complexity and significance of connections and consequence that have shaped our world and our society.

We invite you to join this process of uncovering unexpected connections that are meaningful for you. As you move through this exhibit, notice what stirs within you and honor your reactions. Consider the memories they awaken. Throughout this exhibit space you will find opportunities to leave your own traces: reflections, stories, scribbles. They will become part of the living exhibit and help others find their paths towards connection.

We, as individuals, communities and a nation, are challenged by forces that would divide us and would erase our awareness of the connections that have shaped and sustained us. I have a strong sense that the more we uncover about the web of interactions and meaning that have brought each of us to the place we now stand, and the more we can share those discoveries and understanding, the better prepared we will be to find common purpose and to prevail in an uncertain future.

Quotation from Rilke’s “Letters to a Young Poet”

Together we learned how to love the landscape

Dinosaur National Monument, Utah 1969