LEARN MORE ABOUT FIRST TUESDAYS AND JOIN THE

Jon R. Roth, MS,

EDITORIAL

EDITOR,

Lauren S. Williams

DESIGNED BY Morganne Stewart

Erin Roe, MD, MBA January 2025

Michelle Caraballo, MD, Chair

Ravindra Mohan Bharadwaj, MD

Jawahar Jagarapu, MD

Ravina R. Linenfelser, DO

Sina Najafi, DO

Celine Nguyen, Student

Shyam Ramachandran, Student

Shaina Drummond, MD, President

Gates Colbert, MD, President-elect

Vijay Giridhar, MD, Secretary/Treasurer

Deborah Fuller, MD, Immediate Past President

Neerja Bhardwaj, MD

Justin Bishop, MD

Sheila Chhutani, MD

Philip Huang, MD, MPH

Nazish Islahi, MD

Allison Liddell, MD

Riva Rahl, MD

Anil Tibrewal, MD

NEW DCMS HEADQUARTERS IN THE HEART OF UPTOWN

Jon R. Roth, MS, CAE

AS THE CALENDAR TURNS TO JANUARY, there’s a palpable sense of renewal in the air. The dawn of a new year brings with it a unique opportunity to reset, refocus, and reenergize. It’s a time when the slate is wiped clean, and the possibilities seem endless. But beyond the symbolic fresh start, there’s a deeper psychological significance to beginning the year on a positive note. How we approach January can set the tone for the entire year, influencing our mindset, motivation, and overall well-being.

January is more than just the first month of the year; it’s also a psychological anchor. The way we start the year can create a ripple effect, impacting our attitudes and behaviors in the months that follow. When we begin January with optimism and a proactive mindset, we lay the groundwork for a year filled with growth and achievement.

Research in psychology supports the idea that initial conditions can have a lasting impact. This phenomenon, known as the “primacy effect,” suggests that our first experiences in a sequence are more influential than those that come later. By starting January with positive intentions and actions, we can harness this effect to our advantage.

One of the most effective ways to start January on a positive note is by setting clear, achievable goals. Goal-setting provides direction and purpose, giving us something to strive for. It’s important to set goals that are specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). This approach not only makes our goals more manageable but also increases our chances of success.

I know my own experience has been to take some time at the beginning of January to reflect on what I want to achieve in the coming year. Whether it’s

personal growth, career advancement, or improved health and wellness, having a clear vision of your goals can provide the motivation needed to pursue them with enthusiasm.

A growth mindset, a term coined by psychologist Carol Dweck, is the belief that our abilities and intelligence can be developed through dedication and hard work. Embracing a growth mindset in January can set the stage for a year of continuous learning and improvement. Instead of viewing challenges as obstacles, we can see them as opportunities to grow and develop.

Starting the year with a growth mindset means being open to new experiences, willing to take risks, and ready to learn from failures. It’s about focusing on the journey rather than just the destination. By adopting this mindset, we can approach each day with curiosity and enthusiasm, making the most of every opportunity that comes our way.

In the hustle and bustle of daily life, it’s easy to neglect self-care. However, starting January with a commitment to self-care can have a profound impact on our overall well-being. Self-care isn’t just about pampering ourselves; it’s also about taking intentional actions to maintain our physical, mental, and emotional health.

I make self-care a priority by incorporating activities that nourish my body and mind. This includes a regimented exercise routine, healthy eating, mindfulness practices, and adequate rest. I find that, by taking care of myself physically and mentally, I feel like I have a strong foundation that enables me to tackle the challenges of the year with resilience and vitality.

Gratitude is also a powerful tool for enhancing our well-being and fostering a positive outlook. Starting January with a focus on gratitude can help us appreciate the present moment and recognize the abundance in our lives. Research has shown that practicing gratitude can increase happiness, reduce stress, and improve overall mental health.

Consider starting a gratitude journal in January, where you write down things you’re thankful for each day. This simple practice can shift your perspective and help you find joy in the little things. By cultivating gratitude, we can create a positive feedback loop that enhances our mood and outlook throughout the year.

Acts of kindness and generosity can also have a positive impact on gratitude and our relationships. Whether it’s volunteering, helping a neighbor, paying for someone’s coffee anonymously, or simply offering a kind word, these actions can create a sense of community and belonging. By fostering strong relationships, we create a support system that can help us navigate the ups and downs of the year.

While it’s important to set goals and have a plan, I think it is equally important to remain flexible and adaptable. We all know that life is unpredictable, and unexpected challenges are going to arise! Starting January with a mindset of adaptability and making the decision to navigate these

challenges with grace and resilience is a key to not getting rattled and off-center.

As we embark on this new year, let’s embrace January as a month of possibilities. By starting the year on a positive note, we can set the tone for a year filled with growth, achievement, and well-being. Whether it’s through setting clear goals, embracing a growth mindset, prioritizing self-care, cultivating gratitude, building strong relationships, or staying flexible, there are countless ways to create a positive foundation for the year ahead. Remember, the journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. Let’s make that first step in January a positive and intentional one, setting the stage for a year of endless possibilities. Here’s to a bright and successful year ahead! DMJ

Jon R. Roth, MS, CAE DCMS EVP/CEO

Scan with your phone to connect with us on social!

Dallas medical professionals look to the Dallas Medical Journal and its community of peer contributors as a valued resource for Dallas County medical information. Our goal is to provide insights on various topics, including patient advocacy, legislative issues, current industry standards, practice management, physician wellness, and more.

The Dallas Medical Journal selectively accepts articles from industry professionals that meet our editorial guidelines. We always seek original, informative articles that ultimately will be a useful source to give our professional readers a broad yet unique reading experience.

If you are interested in submitting an article for consideration, or have additional submission questions, please email Lauren Williams at lauren@dallas-cms.org.

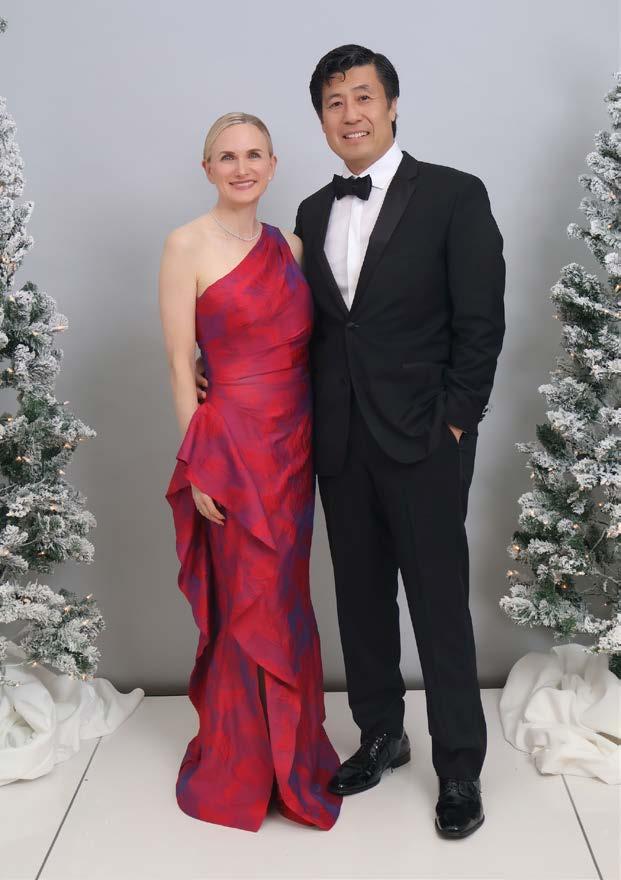

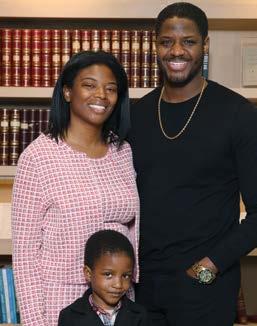

The 142nd President of the Dallas County Medical Society

Championing Compassion, Leadership, and Change in Medicine

by Samantha Sabio

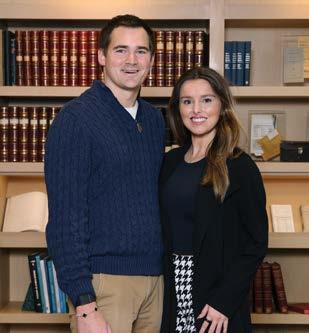

SHAINA DRUMMOND, MD, FASA, is a highly accomplished physician specializing in anesthesiology and pain management. As a first-generation college graduate, a devoted mother and wife, an associate professor of anesthesiology and pain management, and the incoming president of the Dallas County Medical Society (DCMS), she’s made significant achievements while gracefully managing various responsibilities with determination and resilience. And now she’s here to share her story.

Medicine wasn’t always an obvious career choice for Dr. Drummond. “I didn’t grow up around physicians, scientists, or engineers,” she said. “On my first day of high school chemistry, I felt completely out of place.” But thanks to her chemistry teacher, all that quickly changed. Her teacher emphasized critical thinking over rote memorization, and encouraged her to excel in science and consider medicine as a career. “My high school chemistry teacher’s mentorship changed my perspective and planted the seeds of possibility,” Dr. Drummond said.

As a first-generation college student raised by a single mother and her grandparents, Dr. Drummond understood that the path ahead would not be an easy one. “I knew I needed to find a way to finance my education myself,” Dr. Drummond said. She also knew that it would take a lot of hard work and perseverance to get her where she wanted to go. Fortunately, she had a solid support system at her back. “My grandparents were hardworking Kansans who taught me the value of a strong work ethic, kindness, and honesty,” Dr. Drummond said. “They consistently encouraged me to pursue my passions and dreams. Despite my grandfather’s poor health, both he and my grandmother worked tirelessly to support me, providing financial assistance and health insurance during my early adult years. Their sacrifices allowed me to focus on excelling in demanding science courses and summer internships, so I could pursue my dream of becoming a physician.”

Dr. Drummond attended Kansas State University, excelling academically and graduating summa cum laude with a Bachelor of Science. During her undergraduate studies, she was selected to participate in the University of Kansas School of Medicine’s Summer Mentor Program. This experience strengthened her interest in medicine. Working under Dr. Donna Sweet, a trailblazer in HIV/AIDS care, inspired Dr. Drummond

to approach medicine with compassion and a commitment to patient dignity. “Witnessing Dr. Sweet’s kindness toward patients during a time of immense stigma was transformative,” she said. “I knew I wanted to become a physician.”

After graduating from Kansas State, Dr. Drummond attended medical school at the University of Kansas (KU). In her second year of medical school, Dr. Drummond was elected by her peers to be president of the American Medical Student Association chapter at KU. This was her first experience with organized medicine. “It taught me the importance of teamwork and advocacy,” she said. Those lessons would come to shape her professional journey.

During her third-year surgery rotation, Dr. Drummond was exposed to the world of anesthesia. “I felt a sense of belonging and satisfaction of being in the operating room,” she recalled. Her decision to pursue anesthesiology solidified during her first intubation and IV placement under the guidance of a supporting female anesthesiologist. During her rotation, Dr. Drummond quickly learned that being a great anesthesiologist required more than just strong technical skills and academic knowledge. “While the science of anesthesia is crucial, the art of the profession is equally important,” she explained. “Anesthesiologists must be able to quickly build rapport and create a calming atmosphere for patients in stressful moments. It demands a balance of confidence, humility, and grace to earn a stranger’s trust that you will be able to put them to sleep and wake them up safely. “

After completing her anesthesiology residency at the University of Nebraska, Dr. Drummond elected to pursue a pain fellowship at the University of Vermont. This opportunity would provide her the ability to form lasting relationships with patients through continuous care, something she had missed in her anesthesiology residency. Upon completion of her pain fellowship, Dr. Drummond joined a private practice group in South Carolina that allowed her to practice a combination of both anesthesiology and pain management. However, changes in her personal journey led Dr. Drummond to leave small-town life behind and move to the big city. “I made the best decision of my life when I moved to Texas,” she said. “I came to Dallas alone, not knowing anyone. It was a leap of faith, but I knew I had to leave my small-town community to find a position that would offer more opportunities for leadership and allow me to become a more well-rounded physician.”

Dr. Drummond also made the decision to leave private practice and pursue a role in academic medicine at UT Southwestern. She currently works in the anesthesia division at Parkland County Hospital. “Working in academia has been incredibly rewarding, as education is key to shaping the future of medicine,” Dr. Drummond said. “By guiding the next generation of physicians, I can contribute to the advancement of medicine and ensure that future doctors are not only skilled but also compassionate and well-rounded in their approach to patient care.”

Dr. Drummond’s dedication to her work has led her to participate in a number of professional and community organizations. She’s a member of the Texas Society of Anesthesiologists and the Texas Pain Society, and serves as a vice councilor on the Board of Councilors for the Texas Medical Association. On a national level, Dr. Drummond is a member of the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the

Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia. Explaining her commitment to her professional organizations, Dr. Drummond stated, “I’ve always believed in the importance of being active in professional societies and organized medicine. I dedicate my time to these organizations because it allows me to contribute to the broader healthcare community and influence positive change. These platforms provide an opportunity to collaborate with peers, advocate for improvements in patient care, and shape policies that impact both the practice of medicine and the well-being of patients. Engaging in these efforts also keeps me informed on the latest advancements and best practices, ensuring that I continue to grow professionally while helping to advance the field as a whole.”

Dr. Drummond spoke thoughtfully about the growth of her career, while also acknowledging the challenges she has encountered along the way. “I’ve struggled with imposter syndrome and self-doubt throughout my life,” she shared. “Having faced significant hardships in my personal life, education, and career, I’ve often placed tremendous pressure on myself to succeed. I’m learning to show myself grace in the face of challenges and setbacks, recognizing that life doesn’t always unfold as planned—and that’s okay.”

Despite the challenges of navigating most of her educational journey on her own, Dr. Drummond recognizes that she could not have become a physician without the support of her grandparents. One of the most cherished moments of Dr. Drummond’s medical journey was when her grandmother, who had been her steadfast supporter throughout her education, attended her white coat ceremony in her final year of medical school. “I’ll never forget when she gifted me my first stethoscope after the ceremony,” Dr. Drummond recalled. “My grandmother shared that the gift was from both her and my grandfather, expressing how proud he would have been to see me in my white coat. It was an incredibly emotional moment that I will forever cherish.”

Now, in her career, Dr. Drummond continues to feel fortunate to be surrounded by others who share her commitment to making a difference. “Working at Parkland for many years has allowed me to care for a diverse patient population, including underserved and vulnerable communities with limited access to healthcare. In my pain clinic, I encounter patients who are incredibly grateful for the care they receive,” she said. Dr. Drummond recalled that, after the birth of her daughter, many of her patients with limited financial resources expressed their gratitude by giving her thoughtful gifts for her newborn. “That kind of generosity meant so much to me,” she shared.

Currently, Dr. Drummond is preparing to take on the role of president of the DCMS. “I’m both humbled and honored to be selected by my peers, though I must admit, I’m a little nervous about filling such big shoes,” she said. “It’s been a deeply rewarding journey, evolving from someone who aspired to lead into someone who now fully embraces that role. One moment, you’re quietly sitting in a meeting, unsure of sharing your thoughts because you feel inexperienced, and the next, you find the inner confidence to step into new leadership positions.”

Reflecting on the milestone of having three women serve consecutively as DCMS president, Dr. Drummond expressed her pride but also a deep sense of responsibility. “While I’m incredibly proud

of this achievement, I also feel a strong duty to advocate for women’s health issues in Texas and work to ensure that lawmakers protect and respect the patient-physician relationship,” she said.

Throughout her six years as a DCMS board member, Dr. Drummond has connected with respected and knowledgeable physicians across Texas on issues related to medical decision-making and inclusivity. These experiences have been both inspiring and influential, and she plans to carry these qualities into her presidency. “My goal for this year is to ensure that all physicians in Dallas see DCMS as an organization that enriches not just their professional lives but their personal ones as well,” she said. “I plan to continue strengthening our advocacy, practice management, and networking programs while expanding initiatives around work-life balance, diversity, mental health resources, and entrepreneurship opportunities.”

Dr. Drummond owes much of her success not only to herself but to the people who have led and guided her on her journey. From her grandparents to her high school chemistry teacher, her support system is something she’s been consistently grateful for. She’s been taught by mentors and colleagues like Dr. Kevin Klein, a professor of anesthesiology at UT Southwestern, who sponsored her leadership journey through DCMS. And she’s been celebrated by her family—her husband, Dr. Jonathan Oh, her daughter, Lilly, and her stepchildren, Olivia and Christian. In addition to spending time with her family, Dr. Drummond enjoys traveling, reading, discovering new restaurants in Dallas, sampling different cuisines, spending time outdoors, and playing tennis. DMJ

• Stop scope of practice expansion and grow the physician workforce

• Enhance health care access

• Expand access to care with telemedicine payment parity

• Protect public health by defending Texas’ vaccine laws

• Safeguard medical liability protections

• Reform prior authorization and streamline Medicaid

• Ensure new technology is physician vetted

• Improve women’s health

• Allow physicians to practice as trained

• Develop a noncompete agreement law that works for all physicians

FIRST TUESDAY VISITS WILL BE HELD IN EARLY 2025 in conjunction with the 89th session of the Texas Legislature. These visits offer an important opportunity to engage with legislators on the issues important to physicians and the patients you serve!

DCMS and the Texas Medical Association (TMA) have a strong history of advocacy and physician engagement during legislative sessions. In 2025, First Tuesday visits to the Capitol will be held in February, March, April, and May, though we encourage physicians to attend the earlier months if they must prioritize. DCMS invites our member physicians to register to attend on the TMA website. DCMS staff will coordinate and attend the visits, so even if this is your first time, you will have comfortable, organized, and productive meetings! Organized visits with legislators will take place and focus on the TMA Top 10 Legislative Priorities as well as any other key items that come up during the session. Please visit the TMA Events page to register.

The Texas Legislature is a bicameral legislature with 31 state senators and 150 state representatives. The Legislature meets in odd years for a 140-day regular session starting in January and ending in June. Special sessions may be called following the regular session to focus on specific items set by the governor. Dallas County has a number of legislators with all or part of their district within the county. DMJ

Vivian Agumadu, MD Internal Medicine

Yasmin Amir, MD Dermatology

Ray Aronowitz, MD Orthopedic Surgery

Noy Ashkenazy, MD Ophthalmology

Ali Baiomy, MD, PhD Radiology, Vascular & Interventional

Robert Brunner, MD Urology

Janet Cathriner, MD General Practice

Christina Chan, MD Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine

Lindsay Chapman, DO Psychiatry

Joseph Claiborne, III, MD Internal Medicine

Brian Conway, MD Cardiovascular Disease

Anand Dave, MD Internal Medicine

Lee Drinkard, MD Oncology

Yaser Elqutub, DO Family Medicine

Ramachander Eluri, MD Internal Medicine

Samantha Etienne, MD Oncology

Steven Fields, MD Radiology, Diagnostic

Andrew Gdowski, DO, PhD Hematology/Oncology

Jessica Gillen, MD Gynecological Oncology

Michael Grandison, DO General Practice

Surbhi Gupta, MD Internal Medicine

Russell Huq, MD Emergency Medicine

Vinson Huynh, MD Anesthesiology

Kristen Innes, MD Obstetrics and Gynecology

Ryan Kennedy, MD Surgery, General

Farhan Khan, MD Internal Medicine

Daniel Kim, MD Anesthesiology

Jorge Kim, MD Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation

Govind Krishnan, MD Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine

Krutika Kuppalli, MD Infectious Diseases

Ellen Labauve, MD Obstetrics and Gynecology

David Lam, DO Family Medicine

Charles Levin, MD Cardiovascular Disease

Tejaswi Marri, MD Anesthesiology

Christopher Martin, MD Hospitalist

Carrie Moore, MD, PhD Pediatric Surgery

Garrett L. Morris, DO Anesthesiology

Brianne Nicoletti, DO Infectious Diseases

Kathy Niu, MD Neuropsychiatry

Taylor Nohrn, MD Anesthesiology

Ebele Obialo, MD Endo, Diabetes & Metabolism

Bless Onaiwu, MD Obstetrics and Gynecology

Rene Parungao, MD Surgery, General

Alex Petrosian, MD Emergency Medicine

Jason Plata, MD Anesthesiology

Joseph Sailors, MD Pathology, Cytopathology

Mohammed Salameh, MD Pediatrics

Rufus Samuel, MD Obstetrics and Gynecology

Jay Shah, MD Orthopedic Sports Medicine Surgery

James Shull, Jr., MD Anesthesiology

Katherine Smith, MD Obstetrics and Gynecology

William Sory, MD Radiology

Alexander Tatara, MD Internal Medicine

Danyal Thaver, MD Pediatric Critical Care

Daniel Thimann, MD Pediatrics

Stephanie Watabe, MD Pediatrics

Frank Webster, MD Psychiatry

James Williams, DO Emergency Medicine

Risheng Ye, MD Family Medicine

Dae Ik Yi, MD Anesthesiology

Annum Zulfiqar, MD Family Medicine NOT

provides valuable services, programs, and advocacy for physician members throughout the Dallas area. For more info about membership, email info@dallas-cms.org or call 214-948-3622.

MORE ABOUT DCMS AT DALLAS-CMS.ORG

The Dallas County Medical Society and its physician members would like to congratulate Shaina Drummond, MD, on being installed as the 2025 President of the Dallas County Medical Society

THE DONOR RECEPTION AND OPEN HOUSE was held on Sunday, December 15, 2024, and it was a wonderful day of celebration! Every DCMS member who had contributed to the Capital Campaign, as well as a few special guests including the architects who worked on the project, were invited. The turnout was fantastic, and guests enjoyed food, cookies, a gift bag, lattes, and a champagne toast. Dr. Donna Casey gave remarks and awarded a plaque to each member of the relocation committee members. Guests especially seemed to enjoy the Lattes on Location station in the front of the building, and the building was full and had a festive spirit throughout the afternoon. This was a very special occasion in the history of DCMS it was a wonderful opportunity to socialize and celebrate the building and the future of the Society.

by Andrew GolSdsmith, MD, MBA; Lachlan Driver, MD; Nicole M. Duggan, MD; Matthew Riscinti, MD; David Martin, MD; Michael Heffler, MD; Hamid Shokoohi, MD, MPH, FDP- AEUS; Andrea Dreyfuss, MD; Jordan Sell, MD; Calvin Brown, MD; Christopher Fung, MD; Leland Perice, MD; Daniel Bennett, MD; Natalie Truong, MD; S. Zan Jafry, MD; Michael Macias, MD; Joseph Brown, MD; Arun Nagdev, MD

ULTRASONOGRAPHY-GUIDED NERVE BLOCKS (UGNBS) have become a core component of multimodal analgesia for acute pain management in the emergency department (ED). Despite their growing use, national adoption of UGNBs has been slow due to a lack of procedural safety in the ED.

OBJECTIVE: To assess the complication rates and patient pain scores of UGNBs performed in the ED.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS: This cohort study included data from the National Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Block Registry, a retrospective multicenter observational registry encompassing procedures performed in 11 EDs in the US from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2023, of adult patients who underwent a UGNB.

EXPOSURE: UGNB encounters.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES: The primary outcome

of this study was complication rates associated with ED-performed UGNBs recorded in the National Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Block Registry from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2023. The secondary outcome was patient pain scores of ED-based UGNBs. Data for all adult patients who underwent an ED-based UGNB at each site were recorded. The volume of UGNB at each site, as well as procedural outcomes (including complications), were recorded. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics of all variables.

RESULTS: In total, 2735 UGNB encounters among adult patients (median age, 62 years [IQR, 4177 years]; 51.6% male) across 11 EDs nationwide were analyzed. Fascia iliaca blocks were the most commonly performed UGNBs (975 of 2742 blocks [35.6%]). Complications occurred at a rate of 0.4% (10 of 2735 blocks). One episode of local anesthetic systemic toxicity requiring an intralipid was reported. Overall, 1320 of 1864 patients (70.8%) experienced 51% to 100% pain relief following UGNBs. Operator training level varied, although 1953 of 2733 procedures (71.5%) were performed by resident physicians.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE: The find-

ings of this cohort study of 2735 UGNB encounters support the safety of UGNBs in ED settings and suggest an association with improvement in patient pain scores. Broader implementation of UGNBs in ED settings may have important implications as key elements of multimodal analgesia strategies to reduce opioid use and improve patient care.

Ultrasonography-guided nerve blocks (UGNBs) are a critical component of multimodal analgesia across medical specialties. Along with offering optimal analgesia and reducing the reliance on opioids, these procedures can reduce health care–associated complications.1-7 UGNBs have become a staple of both perioperative pain control and chronic pain management in outpatient clinics.

Currently, pain medicine fellowships that emphasize training in UGNBs are attracting applicants from more than 20 different graduate medical education fields, thus emphasizing the multidisciplinary benefits of pain management education and training.8,9

The short-term and long-term deleterious effects of opioid use (tolerance, misuse, opioid- induced hyperalgesia, physical dependence, falls, and addiction) are broadly documented.10-18 Unfortunately, given the often inadequate pain control achieved with medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen for acutely painful conditions, opioid use has become commonplace in the emergency department (ED) setting. Along with the deleterious effects, use of opioids in the ED has been shown to increase health care costs and lead to poor patient outcomes.16-21 As such, ED-based pain management is beginning to rely on multimodal approaches to maximize pain management, minimize complications, and improve patient care.

Over the past decade, numerous case series, retrospective studies, and a few trials on specific EDperformed nerve blocks have suggested that UGNBs performed by ED clinicians may be safe and potentially effective for various acute injuries.22-24 However, a large study encompassing all ED UGNBs across multiple EDs has never been evaluated. A recent American College of Emergency Physicians’ policy statement delineated UGNBs as not only falling within the scope of ED-based practice but also named them as a critical component of ED-based pain management.25,26 Other specialties now also recognize UGNBs as a cornerstone of ED-based care including the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the American College of Surgeons, which in 2020 published best practices guidelines endorsing UGNBs as a standard of care for pain management in patients presenting with traumatic

injuries.25-28

While some EDs have begun to embrace the use of UGNBs, wide-scale adoption is lacking.

Barriers to widespread use include lack of procedural training and competency, unclear incidence of complications (eg, peripheral nerve injury, local anesthetic systemic toxicity), and uncertainty surrounding procedural efficacy when performed in the ED.29 Current safety and efficacy data have been limited to single institutions with variable reporting and low sample sizes.30 To our knowledge, there have been no large-scale multicenter analyses defining the safety and efficacy of UGNBs performed by emergency clinicians in the US.

Our study presents the findings from the National UltrasoundGuided Nerve (NURVE) Block Registry, a multicenter clinical registry developed by 3 authors (A.G., J.B., and A.N.) with contributions from all authors. To our knowledge, the registry is the first to assess procedural practice and outcomes of ED-performed UGNBs. Our overall aim was to define both safety and efficacy profiles of UGNBs being performed by ED physicians for acute painful conditions across the US.

The NURVE Block Registry is a multicenter retrospective registry of UGNBs performed in 11 EDs in the US from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2023. Sites self-selected for participation in the registry. The institutional review board of each participating site approved this cohort study prior to data collection and analysis and waived the need for informed consent owing to the use of deidentified data. This study was performed in adherence with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

All adult patients 18 years or older who underwent a UGNB in participating EDs during the study dates were included. Nerve blocks without ultrasonography guidance were excluded. To ensure the sufficient capture of UGNBs and that the dataset was representative of national practice patterns, each participating site director was required to confirm that greater than 90% of UGNBs were reported to the registry from each site to contribute data to the NURVE Block Registry’s database. In this dataset, all sites recorded 100% of their queried electronic medical record (EMR) UGNB procedure notes. This was queried against all procedure-documented templates to ensure that we were over 90% compliant.

Each site’s director was responsible for entering all registry data. Each site used a mixture of trained physicians and/or research assistants to complete the medical record review. Nonphysicians received at least 1 hour of training prior to the medical record review. Medical records were located by an EMR query of all UGNB procedure notes completed within the ED. All data were collected by retrospective medical record review and were inputted into a standardized data collection form designed by lead study staff (A.G., L.D., J.B., and A.N.) and distributed among participating sites. A subset of data at

each site was reviewed for accuracy, and if a disagreement occurred, a third reviewer served as a tiebreaker. Participating sites queried and submitted data twice yearly to the coordinating center (Brigham and Women’s Hospital) for compliance. A study staff member at the coordinating center (L.D.) reviewed reports for compliance.

Data on delayed complications, such as peripheral nerve injury (PNI), were collected by reviewing the medical record 30 days after the procedure through the local EMR and, if possible, an interoperability platform. The research team at each site entered collected site data into a web-based data collection from REDCap for each UGNB.31,32 Each site’s data were transferred to the coordinating center for quality assurance and analysis.

The primary outcome of this study was to assess the complication rate associated with ED-based UGNBs recorded in the NURVE Block Registry. The secondary outcome was to assess the associated patient pain scores of ED-based UGNBs. Missing data for specific patient variables (ie, pain scores) are presented, given the limitation of retrospective review.

Patient variables collected included demographic data, with identification of the patient’s sex, race, and ethnicity based on the EMR report, and body mass index. Race categories included American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, Black or African American, White, and other (as documented in the EMR and not reflective of specific subcategories). Ethnicity categories included Hispanic or Latinx and non-Hispanic or non-Latinx. Race and ethnicity were ascertained by self-report by individual hospital reporting policies in the EMR; these data were collected because they are self-reported per individual hospital reporting policies in the EHR. Procedural data collected included the specific type of UGNB performed, the clinical indication for UGNB, the type of anesthetic used, the type of adjunct medication used, and the level of training of the proceduralist. Outcome data collected included preprocedure and postprocedure visual analog scale pain scores, as well as both immediate and delayed and major and minor procedural complications. Immediate procedural complications were defined as any changes in hemodynamic status, compartment syndrome, and/or injuries directly resulting from the UGNB (eg, falls). The immediate time period was defined as any complication that occurred while the patient was in the ED during their initial encounter. Delayed complications (eg, PNI) were any complications identified after ED disposition from the date of service up to 30 days after the patient received the UGNB.

Major complications were defined a priori as local anesthetic toxicity syndrome, PNI, pneumothorax, and/or a delay in diagnosis of compartment syndrome. Minor complications were defined as any musculoskeletal injuries resulting from temporary muscle weakness or sensory loss in extremities; 2 of the authors (A.G. and A.N.) determined the type of complication as referred by the individual site. If there was a disagreement, 1 author (J.B.) provided the deciding vote. Three authors (A.G., A.N., and J.B.) have over 30 years of combined experience performing UGNBs in EDs.

Pain scores were measured using a visual analog scale, ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the most severe

pain. The percent change in UGNB-related pain was recorded from before to after the block at the time of disposition and was grouped into quartiles (eg, 0%25%, 26%-50%). These scores were recorded in the EMR by either registered nurses or by clinicians, depending on the institution. If there was a discrepancy in the postblock scores, the smaller improvement in pain score was used.

Data were exported from REDCap to Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp) for statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were performed. Continuous variables were presented as medians with IQRs, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages.

Raw agreement was used to evaluate interrater reliability. The mean (SD) raw agreement across all 11 sites was 0.95 (0.05). To calculate raw agreement, a second independent reviewer analyzed data from 10 randomly selected patients at each of the 11 ED sites, recording the proportion of cases in which the reviewer’s assessment matched the initial assessment across 25 variables per patient. The raw agreement rate for each site was then averaged to obtain an overall measure of agreement. Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

In total, 2735 UGNB patient encounters across 11 EDs nationwide were analyzed. Among patients, the median age was 62 years (IQR, 41-77 years), 1316 of 2727 (48.3%) were female and 1406 of 2727 (51.6%) were male. Of the 2484 patients with data on race, most UGNBs were performed on White patients (1833 [73.8%]), followed by those who were Black or African American (409 [16.5%]).

Among the other race categories, 31 (1.2%) UGNBs were performed on patients who were American Indian or Alaska Native, 181 (7.3%) Asian or Pacific Islander, and 30 (1.2%) other race. Of the 2654 ethnicity categories with data, UGNBs were performed on 533 (20.1%) Hispanic or Latinx patients and 2121 (79.9%) non-Hispanic or non-Latinx patients (Table 1). Of the 11 national sites, 2 were considered community EDs, and 9 had academic affiliations with residency training programs. Eight of the 11 sites had associated advanced emergency ultrasonography fellowships. The range of ED census across the 11 sites was 35 000 to 130 000 patients (eTable in Supplement 1). Of the 11 hospitals, each had at least 1 ultrasonography fellowship–trained physician. All academic sites were level 1 trauma centers, while the

community sites were not trauma centers. Ten of 11 sites were considered to be in urban geographic areas. The highest percentage of blocks performed by an ultrasonography fellowship–trained attending physician was at site number 10, which included a total of 28.1% (81 of 288).

In total, 2735 encounters with 2742 total UGNBs were documented across 11 national sites as a part of the NURVE Block Registry. The median number of patients who underwent nerve blocks per site was 157 (IQR, 129-278) (Figure 1). Overall, of the available data for 2560 UGNBs, 2296 (89.7%) were used for pain control, 246 (9.6%) were used for procedural analgesia, and 18 (0.7%) were used for both.

Among the patients undergoing UGNBs, the median weight was 73.7 kg (IQR, 62.0-86.2 kg), height was 167.6 cm (IQR, 157.5-177.8 cm), and body mass index was 22.6 (IQR, 22.7-25.8), calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Direct oral anticoagulants and/or warfarin were actively used by 135 of 2179 patients (6.2%) at the time of enrollment in the registry (Table 1).

The operator training level predominantly included residents (1953 of 2733 [71.5%]) with attending supervision. There were 221 of 2733 attending physicians (8.1%) with no ultrasonography fellowship training represented of the UGNBs performed. The experience level of the operator varied in terms of volume of UGNBs performed. Operators with over 20 prior UGNBs performed represented 890 of 2198 (40.5%) of UGNBs in the registry, while operators with 5 or fewer total prior UGNBs performed represented 430 of 2198 (19.6%) of the procedures (Table 1).

UGNB TYPES AND INDICATIONS

Among the 2742 UGNB types, the most commonly performed were the fascia iliaca block or femoral nerve block (975 [35.6%]), erector spinae plane block (401 [14.6%]), and forearm (eg, median, ulnar, and/or radial nerve) blocks (242 [8.8%]). Less common procedures, such as the stellate ganglion block and rectus sheath block, were each only performed once (Figure 2).

Among 2735 encounters, 1 major complication was reported in the primary outcome, resulting in a rate of 0.04%. This complication involved a

case of local anesthetic toxicity requiring intralipid administration. Additionally, 9 minor complications were reported, accounting for 9 (0.33%) of the UGNB procedures. These minor complications included hoarseness, breathing difficulty, hypotension, and transient nerve-related symptoms like numbness and weakness. Among the 10 encounters with complications, 6 (60%) required admission and/ or ED observation unit admission, while 3 (30%) were discharged home. Notably, 9 (90%) of the complications were immediate, with 1 (10%) reported as delayed. Further details of each complication are outlined in Table 2.

For the secondary outcome, Table 3 categorizes patients based on the percentage of pain reduction achieved, ranging from 0% to 25% to 76% to 100%, and provides corresponding frequencies. Among the 1864 of 2735 patients (68.2%) with documented pain scores, a total of 1320 (70.8%) experienced 51% to 100% pain relief following UGNB procedures. Notably, 211 of UGNBs (11.3%) had limited or no pain change after the procedure.

In this study, which to our knowledge is the first to use the multicenter NURVE Block Registry, we found that UGNBs performed in the ED setting were associated with low complication rates and improvement in patient pain scores. Our data support the premise that

Distribution of the Total Number of Encounters (N = 2735) With Ultrasonography-Guided Nerve Blocks (UGNBs) at 11 Hospital Emergency Department (ED) SitesHospital ED sites that were a part of the registry were randomly assigned a site number 1 through 11.

Total patients, No (%) (N=2,735)

1,864 (68.2)

Total patients with data

211 (11.3) 0-25%

333 (17.9) 26-50%

402 (21.6) 51-75%

918 (49.2) 76-100%

UGNBs can be incorporated safely into a multimodal regimen for pain control in an acute setting.

In total, 1 major and 9 minor complications were reported in the NURVE Block Registry, representing a complication rate of 0.4%. No patients had significant long-term sequelae from UGNBassociated complications, and no cases of PNI were noted. Cases of PNI, which typically present 48 to 72 hours after procedures, could be missed if the patient did not return to the same site or hospital (or electronically linked hospital center). These data correlate with safety trends reported in anesthesia literature, in which complication rates have also been reported as extremely low in 2 registries and 2 large prospective datasets.33-36 In these studies, the risk of PNI was found to be as low as 0.03%, and local anesthetic toxicity occurred in under 0.02% of cases.30,33-36 As the NURVE Block Registry data increase, updates in complication rates, including delayed complications, will need to be monitored. A future prospective study evaluating PNI will be needed to confirm this, given the inherent limitations of this complication in retrospective review and lack of complete follow-up of all patients at 30 days after a procedure.

The majority of the complications were associated with postprocedural paresthesias and/or weakness. Each case was self-resolving after a brief period (eg, known possible direct effects of the UGNB itself) and thus did not represent true cases of PNI. Clinicians performing UGNBs should be aware and counsel patients on the expected motor and sensory deficits that commonly occur after UGNBs to avoid miscommunications about outcomes and complications. The treating physician should also have a clear plan in place for patients who experience persistent neurological deficits beyond 48 hours. In this study, a transgluteal sciatic nerve block accounted for many of the complications. It is a known risk that patients may get a foot drop associated with the block.

Informing the patient of this common sequela (with clear shared decision-making) with use of crutches may prevent falls when motor involvement of the sciatic nerve block occurs.

Regarding efficacy, the NURVE Block Registry demonstrated that 70.8% of UGNBs were considered successful by reducing pain by 51% to 100%. Conversely, 11.3% were considered a failure due to minimal or no pain reduction, which is similar to values cited in anesthesia literature at approximately 5% to 10%, although in these studies, a failed block was typically defined as requiring additional analgesia or general anesthesia.37-41 We hypothesize that failure rates may have been, in part, due to operator inexperience. As educational UGNB training programs targeting emergency clinicians grow, we hope that the incidence of failure will decline. Future detailed studies may help to determine the root cause of block failures.

The most common UGNB in the registry was the fascia iliaca block (35.6%), which is typically performed for the indication of

acute hip fractures. This block is supported by its extensive literature endorsing the fascia iliaca block utilization in ED settings, as it has been shown to decrease opioid use, enhance pain relief, and lower delirium among the older patient population.42,43 The overwhelmingly supportive literature on the efficacy of the fascia iliaca block has translated to the development of standardized workflows that include UGNBs by ED clinicians for hip fractures.

Similarly, we believe that the safety data from the NURVE Block Registry for other painful ED conditions (eg, rib fractures, acute sciatica) will encourage clinicians, departments, and hospitals to incorporate UGNBs into the acute pain management protocols and reduce the reliance on opioids to improve patient care.

As accomplished for ED-based airway management by the National Emergency Airway Registry,44,45 we recognize the need for a more comprehensive analysis of national trends in ED-based UGNBs’ procedural practice and outcomes. Both the National Emergency Airway Registry and the NURVE Block Registry address ED-based procedures that have the potential to significantly improve patient care and outcomes but also to require specialized procedural competency and training. Despite our data supporting favorable safety and efficacy profiles, nationwide adoption of ED-based UGNB is lacking. Standardized training for emergency medicine clinicians has been cited as a barrier and concern.46-49 Recent data detailing educational initiatives and program development initiatives have been published, alongside guidelines for credentialing emergency physicians.50,51 Standardized training will help enable UGNBs to become standards of care in ED-based pain management, which is vital to reducing reliance on opioid monotherapy and offering optimal pain control to patients. As the NURVE Block Registry continues to expand and accumulate data, it will emerge as a vital tool for refining clinical practices and informing policy decisions.

This study has some limitations. As an observational retrospective study, this work is susceptible to potential reporting bias. Moreover, additional bias may be present due to missing data points inherent to retrospective reporting. Differences in retrospective and prospective registry design may have positively or negatively influenced specific variables. A future prospective registry will help confirm our conclusions. While many EDs use a visual analog scale for pain assessment, the lack of formal standardization may hinder comparability across sites. Additionally, most sites involved in the study were academic centers,

which could limit the generalizability of the findings. Including a broader diversity of sites is necessary to capture true national trends, as 1 of the sites in this registry performed a large portion of the blocks, potentially making our dataset less generalizable. Another limitation is the reliance on EMRs to capture delayed complications, as some complications may be missed in the medical record review. If patients sought care at an outside facility without data sharing, it is possible that these specific complications were not captured. Therefore, while we acknowledge the presence of delayed complications as a potential issue, readers should consider these findings as indicative rather than definitive, with the understanding that more robust, prospective studies would be necessary to accurately capture and assess these outcomes. Despite these limitations, the substantial number of

UGNBs included in this registry makes it less likely that these limitations were associated with our results. To improve data quality in future collections, strategies for data optimization and standardization should be implemented.

In this cohort study of 2735 UGNB encounters, which used a national UGNB registry, we found that UGNBs performed by ED clinicians were associated with overall improvement in patient pain scores. Data from this registry support the scaling of UGNB training and performance across EDs nationally. The findings advocate the widespread adoption of UGNB training and practice across acute care settings, offering a promising avenue for multimodal analgesia strategies that potentially would reduce opioid use and improve patient care. A large prospective database of ED UGNB will be essential to confirm these findings. DMJ

1. Li J, Lin L, Peng J, He S, Wen Y, Zhang M. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided parasternal block in adult cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Minerva Anestesiol. 2022;88(9):719-728. doi:10.23736/S0375- 9393.22.16272-3

2. Eccles CJ, Swiergosz AM, Smith AF, Bhimani SJ, Smith LS, Malkani AL. Decreased opioid consumption and length of stay using an IPACK and adductor canal nerve block following total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2021; 34(7):705-711. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1700840

3. Johnson P, Hustedt J, Matiski T, Childers R, Lederman E. Improvement in postoperative pain control and length of stay with peripheral nerve block prior to distal radius repair. Orthopedics. 2020;43(6):e549-e552. doi:10. 3928/01477447-20200721-14

4. McIsaac DI, McCartney CJL, Walraven CV. Peripheral nerve blockade for primary total knee arthroplasty: a population-based cohort study of outcomes and resource utilization. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(2):312-320. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001455

5. Tsai TY, Cheong KM, Su YC, et al. Ultrasound-guided femoral nerve block in geriatric patients with hip fracture in the emergency department. J Clin Med. 2022;11(10):2778. doi:10.3390/jcm11102778

6. Long B, Chavez S, Gottlieb M, Montrief T, Brady WJ. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity: a narrative review for emergency clinicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;59:42-48. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2022.06.017

7. Ketelaars R, Stollman JT, van Eeten E, Eikendal T, Bruhn J, van Geffen GJ. Emergency physician-performed ultrasound-guided nerve blocks in proximal femoral fractures provide safe and effective pain relief: a prospective observational study in The Netherlands. Int J Emerg Med. 2018;11(1):12. doi:10.1186/ s12245-018-0173-z

8. Silvestre J, Nagpal A. A 10-year analysis of application and match rates for pain medicine training in the United States. Pain Med. 2024;25(6):374-379. doi:10.1093/pm/pnae026

9. Christiansen S, Pritzlaff S, Escobar A, Kohan L. A sudden shift for pain medicine fellowships—a recount of the 2024 match. Interv Pain Med. 2024;3(2):100404. doi:10.1016/j.inpm.2024.100404

10. Friedman BW, Irizarry E, Solorzano C, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of ibuprofen plus metaxalone, tizanidine, or baclofen for acute low back pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74(4):512-520. doi:10.1016/j. annemergmed.2019.02.017

11. Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661-1667. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.16190

12. Lee M, Silverman SM, Hansen H, Patel VB, Manchikanti L. A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician. 2011;14(2):145-161. doi:10.36076/ppj.2011/14/145

13. Tompkins DA, Campbell CM. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: clinically relevant or extraneous research phenomenon? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(2):129-136. doi:10.1007/s11916-010-0171-1

14. Butler MM, Ancona RM, Beauchamp GA, et al. Emergency department prescription opioids as an initial exposure preceding addiction. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(2):202-208. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.11.033

15. Hoppe JA, Kim H, Heard K. Association of emergency department opioid initiation with recurrent opioid use. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(5):493-499.e4. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.11.015

16. Heard K, Ledbetter CM, Hoppe JA. Association of emergency department opioid administration with ongoing opioid use: a retrospective cohort study of patients with back pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(11):1158-1165. doi: 10.1111/acem.14071

17. Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, Lee J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. The comparative safety of analgesics in older adults with arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):1968-1976. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.391

18. Buckeridge D, Huang A, Hanley J, et al. Risk of injury associated with opioid use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1664-1670. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03015.x

19. Miron O, Barda N, Balicer R, Kor A, Lev-Ran S. Association of opioid use disorder with healthcare utilization and cost in a public health system. Addiction. 2022;117(11):2880-2886. doi:10.1111/add.15963

20. O’Neil CK, Hanlon JT, Marcum ZA. Adverse effects of analgesics commonly used by older adults with osteoarthritis: focus on non-opioid and opioid analgesics. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(6):331342. doi:10. 1016/j.amjopharm.2012.09.004

21. Miller M, Stürmer T, Azrael D, Levin R, Solomon DH. Opioid analgesics and the risk of fractures in older adults with arthritis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(3):430-438. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03318.x

22. Beaudoin FL, Haran JP, Liebmann O. A comparison of ultrasound-guided three-in-one femoral nerve block versus parenteral opioids alone for analgesia in emergency department patients with hip fractures: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):584-591. doi:10.1111/acem.12154

23. Blaivas M, Adhikari S, Lander L. A prospective comparison of procedural sedation and ultrasound-guided interscalene nerve block for shoulder reduction in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(9): 922-927. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01140.x

24. Kring RM, Mackenzie DC, Wilson CN, Rappold JF, Strout TD, Croft PE. Ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block (SAPB) improves pain control in patients with rib fractures. J Ultrasound Med. 2022;41(11):2695-2701. doi:10.1002/jum.15953

25. American College of Emergency Physicians. Ultrasound guidelines: emergency, point-of-care, and clinical ultrasound guidelines in medicine. April 2023. Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.acep.org/ siteassets/new-pdfs/ policy-statements/ultrasound-guidelines--emergency-point-of-care-andclinical-ultrasoundguidelines-in-medicine.pdf

26. American College of Emergency Physicians. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks. April 2021. Accessed June 8, 2024. https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/ultrasound-guided-nerve-blocks

27. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Management of hip fractures in older adults: evidencebased clinical practice guideline. December 3, 2021. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.aaos.org/ globalassets/quality- and-practice-resources/hip-fractures-in-the-elderly/hipfxcpg.pdf

28. American College of Surgeons. ACS trauma quality programs. Best practices guidelines for acute pain management in trauma patients. November 2020. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.facs.org/media/ exob3dwk/ acute_pain_guidelines.pdf

29. Goldsmith AJ, Brown J, Duggan NM, et al. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks in emergency medicine practice: 2022 updates. Am J Emerg Med. 2024;78:112-119. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2023.12.043

30. Merz-Herrala J, Leu N, Anderson E, et al. Safety and pain reduction in emergency practitioner ultrasound- guided nerve blocks: a one-year retrospective study. Ann Emerg Med. 2024;83(1):14-21. doi:10.1016/j. annemergmed.2023.08.482

31. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

32. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j. jbi.2019.103208

33. Liu SS, Gordon MA, Shaw PM, Wilfred S, Shetty T, Yadeau JT. A prospective clinical registry of ultrasoundguided regional anesthesia for ambulatory shoulder surgery. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(3):617-623. doi:10.1213/ ANE. 0b013e3181ea5f5d

34. Sites BD, Barrington MJ, Davis M. Using an international clinical registry of regional anesthesia to identify targets for quality improvement. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39(6):487-495. doi:10.1097/AAP. 0000000000000162

35. Barrington MJ, Watts SA, Gledhill SR, et al. Preliminary results of the Australasian Regional Anaesthesia Collaboration: a prospective audit of more than 7000 peripheral nerve and plexus blocks for neurologic and other complications. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34(6):534-541. doi:10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181ae72e8

36. Auroy Y, Benhamou D, Bargues L, et al. Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: the SOS Regional Anesthesia Hotline Service. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(5):1274-1280. doi:10.1097/00000542200211000-00034

37. Sinthuprasit W. Success rate and safety of ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks; a retrospective study of 1,830 cases. Thai J Anesthesiol. 2021;47(4):348-354. https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/ index.php/ anesthai/article/view/252818

38. Zadrazil M, Opfermann P, Marhofer P, Westerlund AI, Haider T. Brachial plexus block with ultrasound guidance for upper-limb trauma surgery in children: a retrospective cohort study of 565 cases. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(1): 104-109. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2020.03.012

39. Lewis SR, Price A, Walker KJ, McGrattan K, Smith AF. Ultrasound guidance for upper and lower limb blocks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(9):CD006459. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006459.pub3

40. Seidel R, Natge U, Schulz J. [Distal sciatic nerve blocks: randomized comparison of nerve stimulation and ultrasound guided intraepineural block]. Anaesthesist. 2013;62(3):183-188, 190-192. doi:10.1007/s00101013- 2150-5

41. Macaire P, Singelyn F, Narchi P, Paqueron X. Ultrasound- or nerve stimulation-guided wrist blocks for carpal tunnel release: a randomized prospective comparative study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33(4):363368. doi:10. 1097/00115550-200807000-00014

42. Reavley P, Montgomery AA, Smith JE, et al. Randomised trial of the fascia iliaca block versus the “3-in-1” block for femoral neck fractures in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(9):685-689. doi:10.1136/ emermed-2013-203407

43. Foss NB, Kristensen BB, Bundgaard M, et al. Fascia iliaca compartment blockade for acute pain control in hip fracture patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(4):773-778. doi:10.1097/01. anes.0000264764.56544.d2

44. Walls RM, Brown CA III, Bair AE, Pallin DJ; NEAR II Investigators. Emergency airway management: a multicenter report of 8937 emergency department intubations. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(4):347-354. doi:10.1016/j. jemermed.2010.02.024

45. Offenbacher J, Nikolla DA, Carlson JN, et al. Incidence of rescue surgical airways after attempted orotracheal intubation in the emergency department: a National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) study. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;68:22-27. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2023.02.020

46. Zewdie A, Debebe F, Azazh A, Salmon M, Salmon C. A survey of emergency medicine and orthopaedic physicians’ knowledge, attitude, and practice towards the use of peripheral nerve blocks. Afr J Emerg Med. 2017;7 (2):79-83. doi:10.1016/j.afjem.2017.04.003

47. Bhoi S, Chandra A, Galwankar S. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks in the emergency department. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3(1):82-88. doi:10.4103/0974-2700.58655

48. Stone A, Goldsmith AJ, Pozner CN, Vlassakov K. Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia in the emergency department: an argument for multidisciplinary collaboration to increase access while maintaining quality and standards. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021;46(9):820-821. doi:10.1136/rapm-2020-102416

49. Brown JR, Goldsmith AJ, Lapietra A, et al. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks: suggested procedural guidelines for emergency physicians. POCUS J. 2022;7(2):253-261. doi:10.24908/pocus.v7i2.15233

50. Farrow RA II, Shalaby M, Newberry MA, et al. Implementation of an ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia program in the emergency department of a community teaching hospital. Ann Emerg Med. 2024;83(6):509-518. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2023.11.013

51. Walsh CD, Ma IWY, Eyre AJ, et al. Implementing ultrasound-guided nerve blocks in the emergency department: a low-cost, low-fidelity training approach. AEM Educ Train. 2023;7(5):e10912. doi:10.1002/aet2.10912

Easily understand your specific CME requirements and compliance status, find and take renewal-ready courses, and report your course completions directly to the Texas Medical Board for a hassle-free renewal.

Benefits: Find, complete, and report approved CME; View your forever course history; Take CME on the go with the free mobile app; Access to 24/7 support and more!

www.cebroker.com

Dallas County Medical Society (DCMS) does not endorse or evaluate advertised products, services, or companies nor any of the claims made by advertisers. Claims made by any advertiser or by any company advertising in the Dallas Medical Journal do not constitute legal or other professional advice. You should consult your professional advisor.

Dallas-Fort Worth Fertility Associates

Growing Family Trees Since 1999

Samuel Chantilis, MD

Karen Lee, MD

Mika Thomas, MD

Ravi Gada, MD

Laura Lawrence, MD

Jennifer Shannon, MD

Monica Chung, MD

Melanie Evans, MD

Locations:

Dallas: 5477 Glen Lakes Drive, Ste. 200, Dallas, TX 75231, 214-363-5965

Baylor Medical Pavilion: 3900 Junius Street, Ste. 610 Dallas, TX 75246, 214-823-2692

Medical City: 7777 Forest Lane, Ste. D–1100 Dallas, TX 75230, 214-692-4577

Southlake: 910 E. Southlake Blvd., Ste. 175 Southlake, TX 76092, 817-442-5510

Plano: 6300 W Parker Road, Ste. G26 Plano, TX 75093, 469-592-8557

www.dallasfertility.com

Health and Human Services/Texas Health Steps - Back cover

Let Biogenic Solutions upgrade your facility with our OSHAcompliant, mobile waste disposal containers & reusable Sharps program for DCMS members.

Maurice G. Syrquin, MD

Marcus L. Allen, MD

Gregory F. Kozielec, MD S. Robert Witherspoon, MD

3414 Oak Grove Ave. Dallas, TX 75204 | (214) 521-1153

Baylor Health Center Plaza I 400 W. Interstate 635, Ste. 320 Irving, TX 75063 | (972) 869-1242

3331 Unicorn Lake Blvd. Denton, TX 76210 | (940) 381-9100

1010 E. Interstate 20 Arlington, TX 76018 | (817) 417-7769

8315 Walnut Hill Lane, Ste. 125, Dallas, TX (214) 363-6000

Robert E. Torti, MD

Santosh C. Patel, MD

Henry Choi, MD

Steven M. Reinecke, MD

Philip Lieu, MD, FASRS

1706 Preston Park Blvd., Plano, TX 75093 | (972) 599-9098

2625 Bolton Boone Drive, DeSoto, TX 75115 | (972) 283-1516

1011 N. Hwy 77, Ste. 103A Waxahachie, TX 75165 | (469) 383-3368

18640 LBJ Fwy., Ste. 101 Mesquite, TX 75150 | (214) 393-5880

10740 N. Central Expy., Ste. 100 Dallas, TX 75231 | (214) 361-6700

Carrell Clinic

A Division of OrthoLoneStar Orthopaedic Surgery & Sports Medicine www.carrellclinic.com

James R. Sackett, MD

Daniel E. Cooper, MD

Paul C. Peters Jr., MD

Andrew B. Dossett, MD

Eugene E. Curry, MD

Daniel A. Worrel, MD

Kurt J. Kitziger, MD

Andrew L. Clavenna, MD

Holt S. Cutler, MD

Mark S. Muller, MD

Todd C. Moen, MD

J. Carr Vineyard, MD

M. Michael Khair, MD

William R. Hotchkiss, MD

J. Field Scovell III, MD

Jason S. Klein, MD

Brian P. Gladnick, MD

Bradford S. Waddell, MD

William A. Robinson, MD

Tyler R. Youngman, MD

Justin Cardenas, MD

9301 N. Central Expy., Ste. 500, Dallas, TX 75231

3800 Gaylord Pkwy., Ste. 710, Frisco, TX 75034

Phone: (214) 466-1446 Fax: (214) 953-1210

Over 100 Years of Orthopaedic Excellence

SINCE 1955, TMA INSURANCE TRUST HAS SERVED AS TRUSTED ADVISORS FOR TEXAS PHYSICIANS, THEIR FAMILIES, AND THEIR EMPLOYEES. Created and exclusively endorsed by the Texas Medical Association, we at TMA Insurance Trust are proud to partner with TMA member physicians to meet their personal insurance needs and help protect their livelihood.

Every day we work exclusively with Texas physicians. Our focus is to help you protect what’s important — your family, income, practice and staff. We walk alongside physicians throughout their entire career journey from medical school to residency and all the way through to retirement.

In an industry that is largely commission based, it can be hard to know if the insurance you’re being sold is what is best for you. All TMA Insur-

EVERYONE IS SIGNIFICANT, AND AT FROST, WE TREAT THEM THAT WAY. WE GIVE OUR CUSTOMERS A SQUARE DEAL AND KEEP THEIR ASSETS SAFE AND SOUND. These beliefs have guided Frost from the very beginning in San Antonio and served our customers well since 1868.

T.C. Frost provided Texans with the supplies they needed to prosper on the frontier. Today, Frost provides individuals and businesses with financial tools and advice to thrive in a fast-paced world.

We offer our customers a full range of banking, investment and insurance products to help them better manage their money, grow their wealth and protect their assets. And our disciplined relationship approach has stood the test of time.

ance Trust employees are salaried, motivated only by excellence, while providing customers with sound advice they can trust. Collectively, our agents have hundreds of years of experience working with, and for, Texas physicians.

Over the past 70 years, we’ve faced a number of challenges, all of which have made us and our partnerships with our customers, insurance companies and consultants, stronger. Our seasoned advisors have seen it all throughout the years, and have a working knowledge of what each insurance company has to offer. This, coupled with a genuine desire to meet the needs of our members, is what makes TMA Insurance Trust one of a kind.

Whether it’s education, economic development, health and human services, or the arts, we support the nonprofit organizations where our employees and customers live and work.

We're from here, and we’ve always played an active role in the communities we serve and call home. Through volunteer programs or independently, our employees offer their hands and hearts to mentor young people, serve on the boards of nonprofits, care for the elderly, and help with important causes. We don’t just open new financial centers to serve the area’s financial needs, but also to play a part in bettering the community for years to come.

At Frost, everything we do is aimed at making people's lives better. And for over 150 years, that commitment has steadily guided our approach to our employees, our planet and the communities we proudly serve.

When you have an account with Frost, you have a relationship with Frost. We’ll answer the phone when you call 24/7, right here in Texas. And we’ll be here for you with a square deal and prudent financial advice and tools to help you with all the milestones in the years ahead.

Many physicians believe that protecting their income is a one-and-done transaction. However, most things in life are not that simple including protecting your income. If you secured your disability insurance some years ago, your income and financial responsibilities have most likely increased. Has your coverage kept pace with these changes?

Physicians who receive disability insurance as a benefit from their employer should consider there are most likely limitations on their coverage. For instance, it most likely covers only 60% of your salary. It may limit the length of time you can collect benefits, and if your employer is paying the premium, your benefits will be taxed as income. If you leave your employer your coverage will end. By then, you may be older and have chronic medical conditions that would make it more difficult and costly to obtain coverage.

To help members, we are now offering $5,000/month of medical specialty own occupation TMA Member Long Term Disability Insurance. This coverage is issued by The Prudential Insurance Company of America. We offer simplified underwriting without the need to verify your income or submit any financial information. Benefits are paid regardless of any other coverage you have and if necessary, benefits can be paid until you reach your Social Security retirement age.

A phone conversation with one of our experienced advisors will help you determine if you are well protected or if you have financial exposure. Call them at 800-880-8181 Monday to Friday, 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM CST. It will be our privilege to serve you.

Group Insurance coverage is issued by The Prudential Insurance Company of America, a Prudential Financial company, Newark, NJ. The Booklet-Certificate contains all details, including any policy exclusions, limitations, and restrictions, which may apply. Contract Series: 83550 1083788-00001-00