ART MUSEUM

Inside The Paper

ALUMNI DONORS PAGE 4

FIRST LOOK AT THE MUSEUM PAGE 5

INSIDE THE PAVILIONS PAGE 6

ART MUSEUM, BY THE NUMBERS PAGE 16

24 HOURS IN THE ART MUSEUM PAGE 18

THE MUSEUM CONFRONTS ITS PAST PAGE 22

DOES THE NEW SPACE DELIVER? PAGE 24

MOSAIC RESTAURANT PAGE 26

STAFF PICKS: FIVE MUST-SEE ITEMS PAGE 28

THE MUSEUM’S BEST STUDY SPOTS PAGE 29

DAVID ADJAYE’S LEGACY PAGE 30

ARCHIVES: MUSEUM RENOVATIONS PAGE 31

editor-in-chief

Miriam Waldvogel ’26

business manager

Jessica Funk ’26

149TH MANAGING BOARD

upper management

Eleanor Clemans-Cope ’26

Isabella Dail ’26

director of outreach

Oliva Sanchez ’26

editors at large Research

Andrew Bosworth ’26

Bridget O’Neill ’26

Bryan Zhang ’26

creative director

Malia Gaviola ’26

Sections listed in alphabetical order.

head archives editor

Lianne Chapin ’26

head audience editors

Paige Walworth ’26

Justus Wilhoit ’26 (Reels)

head cartoon editor

Eliana Du ’28

head copy editors

Lindsay Pagaduan ’26

James Thompson ’27

head data editors

Vincent Etherton ’26

Alexa Wingate ’27

head features editors

Raphaela Gold ’26

Coco Gong ’27

head humor editor

Sophia Varughese ’26

associate humor editors

Tarun Iyengar ’28

Francesca Volkema ’28

head news editors

Victoria Davies ’27

Hayk Yengibaryan ’26

head newsletter editor

Caleb Bello ’27

associate newsletter editor

Corbin Mortimer ’27

head opinion editor

Frances Brogan ’27

Guest opinion editor

Jerry Zhu ’27

head photo editors

Calvin Grover ’27

Jean Shin ’26

head podcast editor

Maya Mukherjee ’27

associate podcast editors

Twyla Colburn ’27

Sheryl Xue ’28

head print design editor

Juan Fajardo ’28

head prospect editors

Russell Fan ’26

Mackenzie Hollingsworth ’26

head puzzles editors

Wade Bednar ’26

Luke Schreiber ’28

head sports editors

Alex Beverton-Smith ’27

Harrison Blank ’26

associate sports editors

Lily Pampolina ’27

Doug Schwarz ’28

head web design and development

editors

Cole Ramer ’28

John Wu ’28

149TH BUSINESS BOARD

assistant business manager

Alistair Wright ’27

directors

Andrew He ’26

Tejas Iyer ’26

William Li ’27

Stephanie Ma ’27

Jordan Manela ’26

James Swinehart ’27

Adelle Xiao ’27

Chloe Zhu ’27

business manager emeritus

Aidan Phillips ’25

149TH TECHNOLOGY BOARD

chief technology officer

Yacoub Kahkajian ’26

software engineers

Abu Ahmed ’28

Jaehee Ashley ’25

Brian Chen ’26

Nipuna Ginige ’26

Angelina Ji ’27

Allen Liu ’27

Rodrigo Porto ’27

Stephanie Sugandi ’27

ui/ux engineer

Joe Rupertus ’26

THIS PRINT ISSUE WAS DESIGNED BY Malia Gaviola ’26

president

BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Thomas E. Weber ’89

vice president

David Baumgarten ’06

secretary

Chanakya A. Sethi ’07

treasurer

Douglas Widmann ’90

treasurer

assistant

Kavita Saini ’09

trustees

Francesca Barber

Kathleen Crown

Juan Fajardo ’28

Suzanne Dance ’96

Gabriel Debenedetti ’12

Stephen Fuzesi ’00

Zachary A. Goldfarb ’05

Michael Grabell ’03

Danielle Ivory ’05

Rick Klein ’98

James T. MacGregor ’66

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd

Abigail Williams ’14

Tyler Woulfe ’07

trustees ex officio

Miriam Waldvogel ’26

Jessica Funk ’26

CALVIN GROVER / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN

EDITOR’S NOTE

When I arrived at Princeton in Fall 2023, the space between Whig-Clio and Brown Hall was a wide pit hidden behind construction barriers. Someday, people said, it would be an impressive art museum, housing a portion of Princeton’s even more impressive collection. One day, they promised, we would be able to see Andy Warhol’s “Blue Marilyn” and Claude Monet’s “Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge” between classes.

Over the last two years, I have watched the art museum slowly take form, starting with metal stakes in the ground, then grey concrete slabs, then cantilevers and ribbed exteriors. Years of students graduated — including the Class of 2025, who experienced a whole four years of construction, never seeing inside the museum — and years of students complained about its solemn grey exterior.

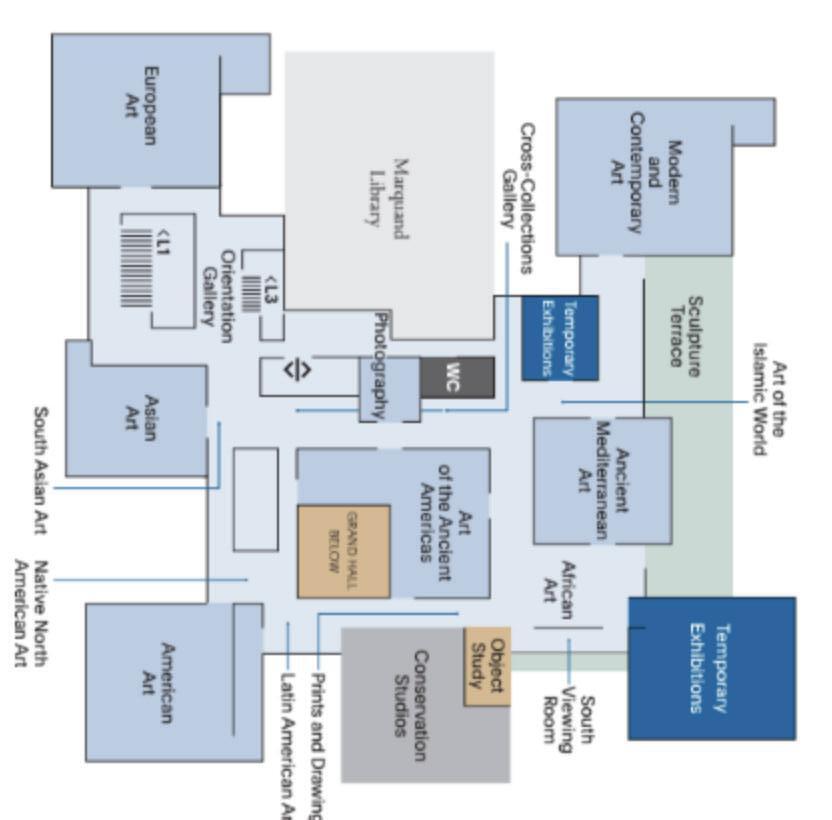

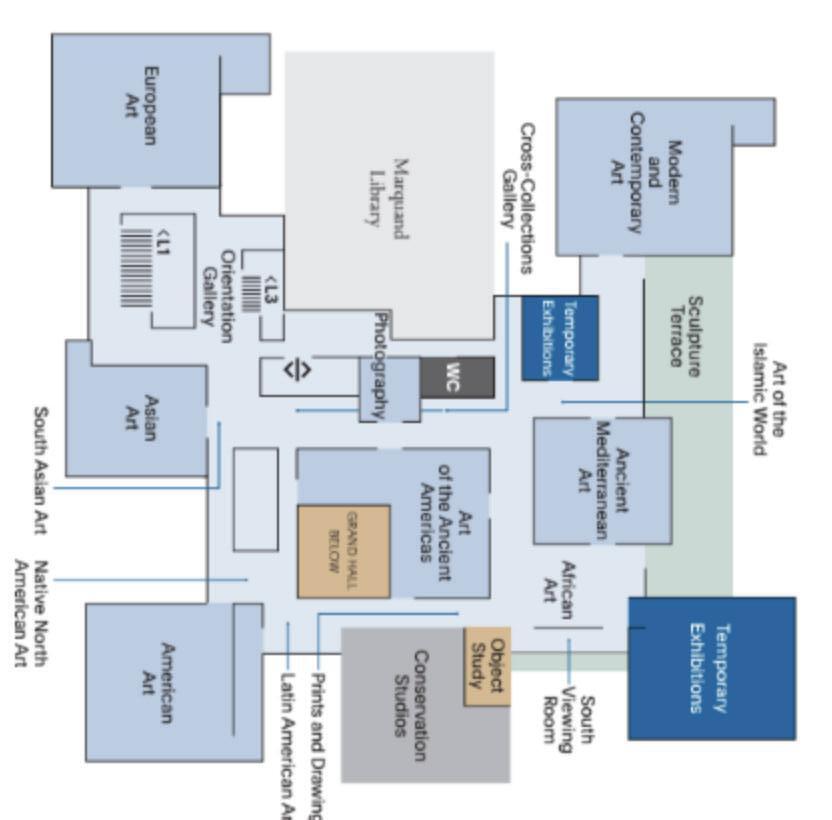

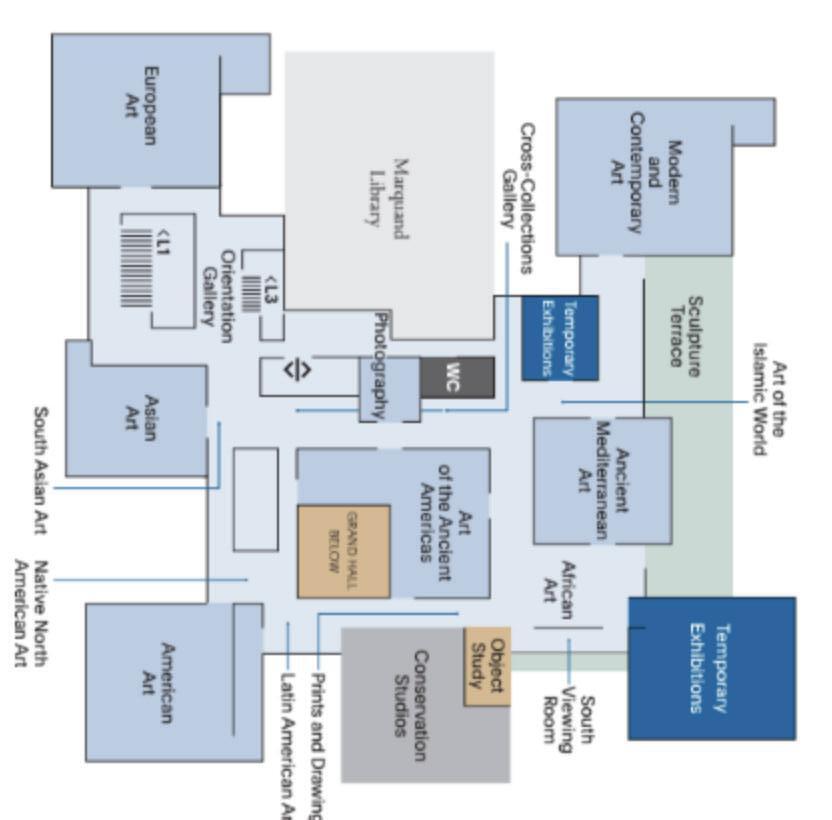

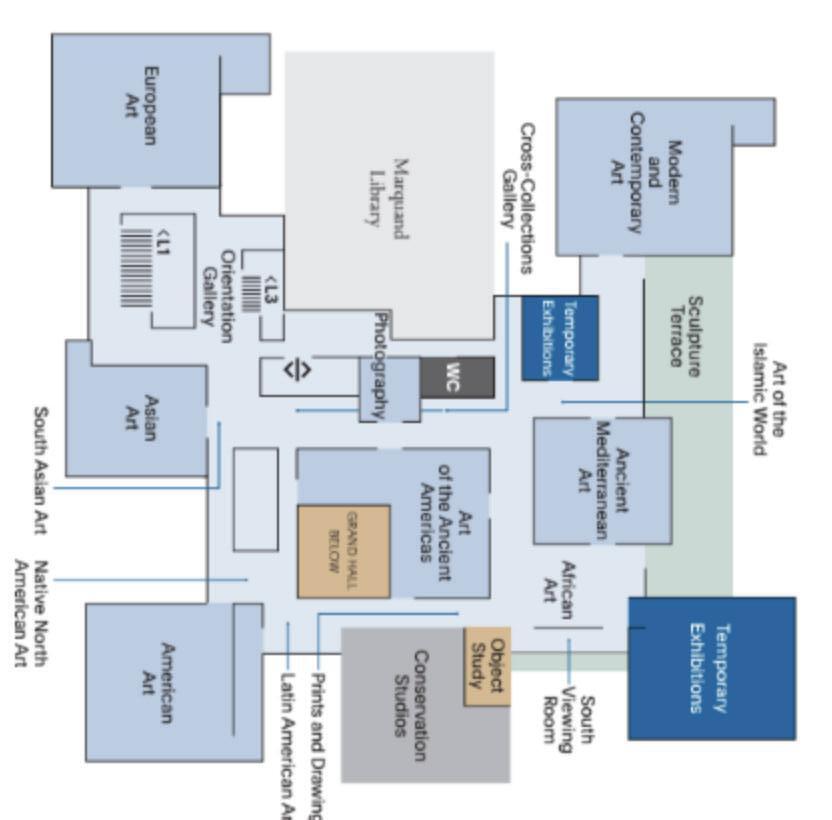

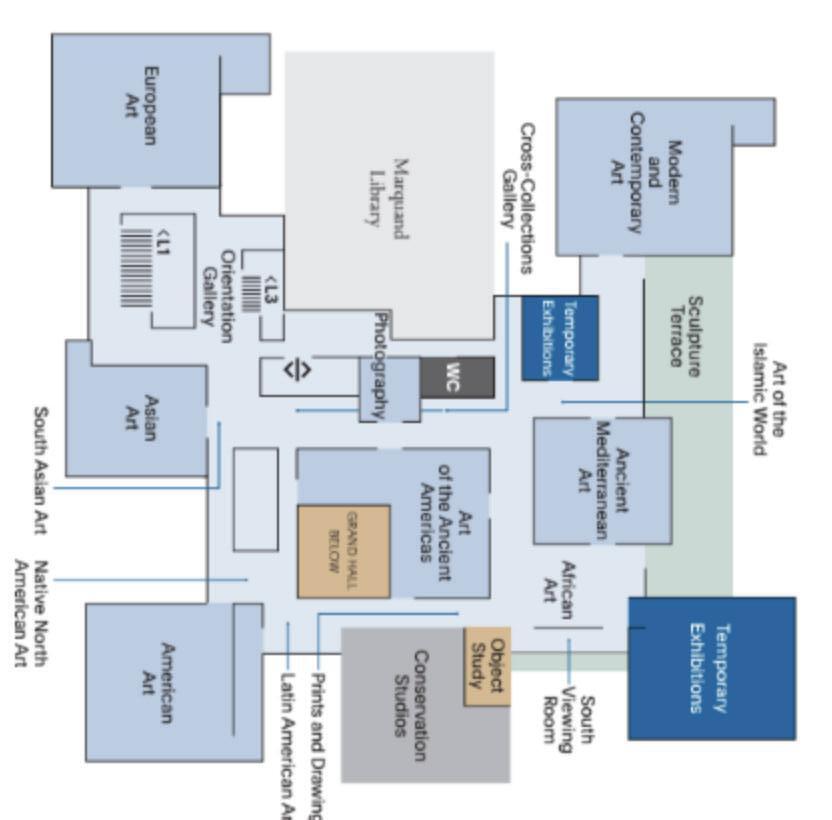

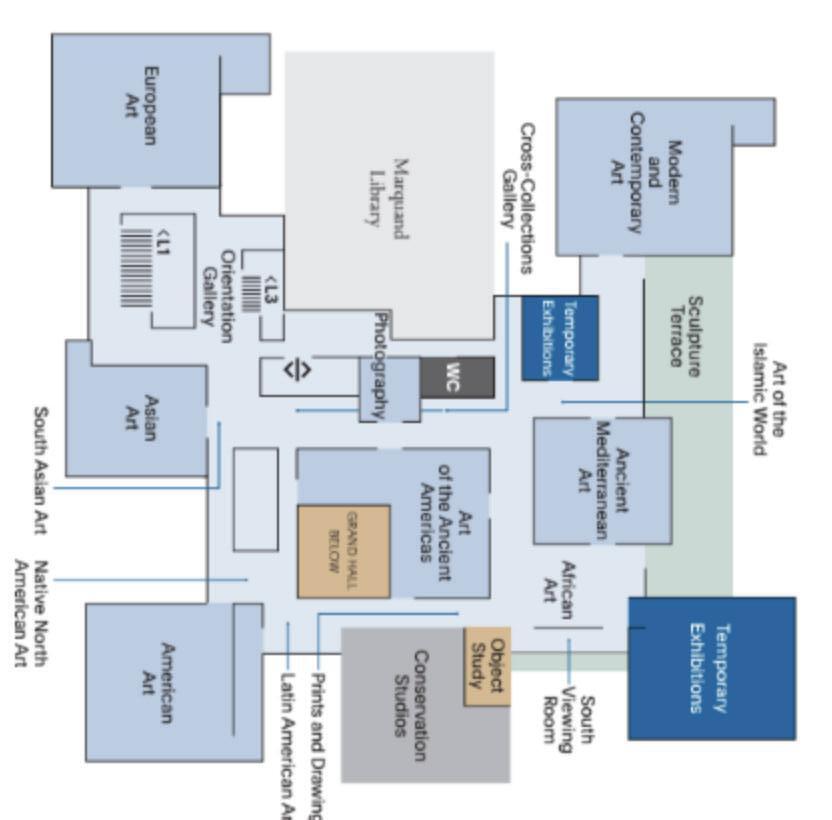

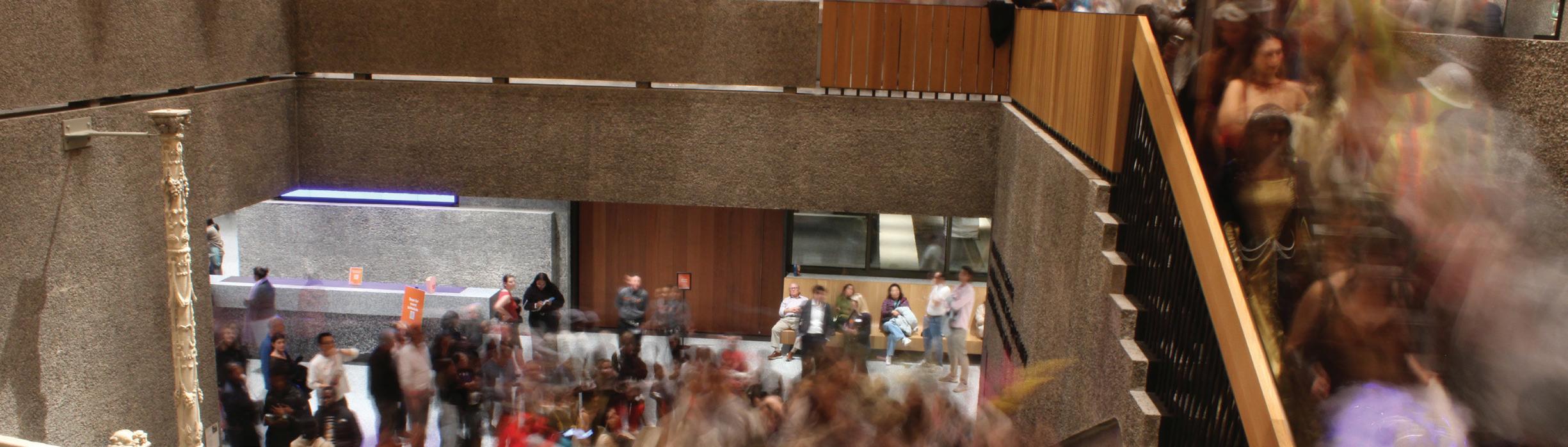

Now, finally, we get to look inside. On Oct. 31, 2025, the art museum re- opened with a 24-hour opening event. Students, professors, staff, town resi- dents, alumni, and children flowed through. With nine pavilions, a restaurant, views of the old halls surrounding it, and almost 5,000 works of art, the museum is the centerpiece of campus and a node connecting the University to the outside world.

In this first-of-its-kind magazine from The Daily Princetonian, you’ll find reviews of each of the pavilions, the hallways and transition spaces, and the new Mosaic restaurant, and bundles of illuminating photos. To bring you this issue, our reporters spoke to curators, tried $13 matcha, and stayed in the art museum for every moment of its 24-hour opening.

Victoria Davies is a head News editor for the ‘Prince.’

Victoria Davies Head News Editor

CALVIN GROVER / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN

Art museum galleries and pavilions dedicated to alumni donors

By Nora Linssen & Victoria Davies Contributing News Writer & Head News Editor

Ahead of the formal opening of the Princeton University Art Museum (PUAM) next week, the Office of Advancement announced the dedication of 15 galleries and three pavilions on Oct. 7 following a years-long Venture Forward campaign.

The donations to PUAM include three “leadership gifts” from Nancy A. Nasher and David J. Haemisegger ’76, Preston Haskell III ’60, and the Fisher family, including Bill Fisher ’79.

“Princeton has a phenomenal art collection and it’s appropriate for a university like Princeton to have a museum like that,” Bill Fisher said in an interview with The Daily Princetonian.

The Grand Hall — a three-story open room that is able to be converted into a 250-person lecture hall — was supported by a gift from the Fisher family, including Bill Fisher, his parents Doris and Don Fisher, the founders of clothing line GAP and honorary members of the Class of 1976. The family also includes his brothers Bob Fisher ’76 and John Fisher ’83, the principal owner of the Oakland Athletics, and his daughter and son-in-law Remy Fisher Wilkinson ’14 and Shane Wilkinson ’13.

“There’s sculpture and art all around you, and it just seemed like a beautiful place to hang out,” Bill Fisher said.

The rest of the first floor is primarily split into the Haskell Education Center and several locations named for the Nashers and Haemiseggers: the Nancy A. Nasher & David J. Haemisegger Family Hall and Grand Stair lead up to the second floor, and the temporary exhibition space currently hosting “Toshiko Takaezu: Dialogues in Clay” is named for their son, David Nasher Haemisegger ’22. The official title of Art Museum Director James Stewart is also named for Nasher and Haemisegger.

American Art is housed in the Wilmerding Pavilion, named by Louisa Stude Sarofim in honor of late Princeton professor of art and archaeology John Wilmerding, who was significant in the development of the Princeton American Studies department. The pavilion contains five galleries dedicated to the Anschutz family.

“I loved the old museum and am very excited to see how the art that I remember so well from my days as a student shines in the new spaces,” Sarah Anschutz ’93 wrote to the ‘Prince.’

She told the ‘Prince’ that Wilmerding “was one of my thesis advisors and I took many of his courses while I was

at Princeton. We kept in touch over the years after I had graduated and [he] was helping my father transform his personal art collection into a small museum.”

Additionally, the Paul & Heather Haaga Conservation Studios in the south of the new building was named in honor of Paul G. Haaga Jr. ’70 & Heather Sturt Haaga. In the previous art museum, conservation space was limited to just one room; now, there are two floors spanning the south pavilion dedicated to conservation.

Heather Haaga is an honorary member of the Class of 1970.

“[Conservation] was a function that, in the past, Princeton had to obtain from others,” Heather Haaga wrote in a statement to the ‘Prince.’ “Now art works can be preserved on campus without sending them out to another museum.”

In addition, the Haagas hope that students will be able to “learn the painstaking work of art repair and conservation.”

“It is a small world of incredibly talented people that keep art safe for future generations and now Princeton will be able to grow that world of experts,” Heather Haaga wrote.

Beyond monetary donations, art donations have been crucial to the opening of the new museum. The tem-

porary exhibition, Princeton Collects, celebrates the more-than 2,000 works donated by more than 200 members of the Princeton community in the last four years, with around 150 works on show until March 2026.

Many other donors have also been honored through various rooms and galleries in the new museum, with two other pavilions named for major gifts from Yan Huo GS ’94 and Dori Walton ’78, Bill Walton ’74, and their children.

Paul Haaga wrote that he is excited about the opportunity to “display a much greater percentage of the museum’s iconic collection.”

Having seen the gallery space in the Spring, Sarah Anschutz wrote she “was impressed by how beautiful the art looks in the new gallery spaces.”

“[It’s] a beautifully contained unit that has traffic flow through all different directions around the building, and is integral and fits into the University campus,” Bill Fisher said.

Nora Linssen is a News contributor for the ‘Prince.’ She is from Boston.

Victoria Davies is a head News editor for the ‘Prince.’ She is from Plymouth, England and typically covers University operations and the Princeton University Art Museum.

CALVIN GROVER / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN

Students looking at portraits of Elizabeth Allan Marquand (Sargent, 1887) and Center of Creation (Michael) (Moore, 2019)

‘Absolutely coming back’: Students get first look inside art museum

By Leela Hensler, Emily Chien, and Sena Chang Staff, Contributing, & Senior News Writers

In an evening featuring music, mocktails, and movies, students received an exclusive first look inside the Princeton University Art Museum (PUAM) on Saturday, Oct. 25.

The preview, which ran from 7 p.m. to 11 p.m., drew an estimated 3,000 attendees and featured Grammy-winning producer Jazzy Jeff as its headliner, alongside performances from student groups. Many students expressed that PUAM was significantly more impressive than anticipated, and that they plan on returning for the official 24-hour opening on Oct. 31.

“[PUAM] actually exceeded my expectations. I think the architecture is really beautiful,” Corinne Jordan ’27 told The Daily Princetonian. “I am definitely coming back — it seems like a lovely place to study, or just hang out.”

“I’m absolutely coming back,” Stephanie Ko ’28 told the ‘Prince.’

“We forget, on the day-to-day, where we are and what kind of institution Princeton is — we get bogged down by our classwork and stuff,” Ko said. “But when we get the chance to slow down and look around, it’s very exciting to see the things that we have access to.”

Julianne Somar ’26, an Architecture major, said that “the initial walk-in was quite magnificent. Being able to see what finally has been revealed and unfolded and seeing the grandeur of the space is really, really nice to take in.”

Seven of the nine pavilions within the museum are only partially walled off to the ceiling, creating open galleries. This open space is intended to “awaken a sense of discovery,” PUAM director James Steward said.

“There’s no path we’re telling you you have to take, there’s no sequence,” Steward told the ‘Prince.’ He said that museum-goers are able to discover

cultures as they please.

Megan Kang GS said that she was “awestruck” by both the museum’s architecture, and described the curation of the art on display as “very playful and very surprising.”

“One of the first pieces I saw was [a] Rothko next to [an] indigenous painting,” she said. “The curation of old and new is really unique, and something you don’t see in a lot of museums.”

Amelia Melendez ’28 said that once she stepped inside, she was enthralled. “It’s like everything catches your eye ... [there’s] so much information and so

Students also appreciated the broad range of art showcased in the museum, with collections dedicated to European, Asian, Middle Eastern, and American, among others. The collections also range across different mediums, including pottery, mosaics, landscapes, furniture, and sculpture.

Sophie Gao ’28 highlighted how parts of PUAM art directly related to the rich history of both the city of Princeton and Princeton University itself, providing a grounded perspective that sets the PUAM apart. Charles Wilson Peale’s “George Washington at

many stories.”

PUAM is not only spatially non-traditional, but also visually unorthodox. Its sprawling modern facade stands out compared to its 19th-century neighboring buildings. The building has garnered criticism from students for its hulking stone design and tendency during construction to block the fastest paths across campus.

“I must admit, it was very annoying with the construction blocking all the routes [to class], freshman, sophomore, junior year, [and] part of senior year,” Joyce Chan ’26 said. However, after visiting the museum, Chan felt it was worth the wait. “I wasn’t expecting to see all these rare art pieces on display.” she said.

seeing a puzzle activity featuring paintings in the gallery.

“Tons of people are getting roped in and absorbed into the activity, so [they’re] appreciating the art in [another] way,” he said.

Unlike Reudelhuber, Officer Simon Sosa, one of the many cultural properties officers who will be working at the museum, didn’t expect to spend his nights at an art museum. “When I came to Princeton as a PSafe officer, I wanted to be more like a police officer,” he said.

“You try to make it fun,” Sosa said. “I like to look at the artwork. Sometimes, if I’m standing for too long, I’ll go read the descriptions.”

The museum will host a 24-hour opening event from 5 p.m. on Oct. 31 to 5 p.m. on Nov. 1, which will be open to members of the larger Princeton community as well as students. Many of the attendees at Saturday’s event planned to return to the grand opening.

Reudelhuber also looked forward to the opportunity to return to the museum as a student rather than an employee. “I’ll get to sort of experience all the levels [and] all the different displays,” he said.

the Battle of Princeton,” for one, sits at the entrance to the American Art pavilion and was installed in Nassau Hall for over two centuries.

“You realize where Princeton was situated in the context of [American history],” Gao told the ‘Prince.’

Throughout the night, PUAM hosted film screenings of “Night at the Museum” (2006) and its sequel alongside live performances from slam-poetry group Songline, eXpressions Dance Company, improv group Quipfire! and Princeton University Ballet. TigerTale also released a limited-edition pin featuring the art museum building designed by Kellen Ducey ’26.

Luke Reudelhuber ’29, who was working for the event planning company Rafanelli, was in charge of over-

“I feel like the vibe here tonight is really good, but I think next weekend it’ll be even better,” Laura Green ’29 said. “I think the community will want to see it too. It’s a great museum.”

Leela Hensler is a staff News writer and a staff Sports writer for the ‘Prince.’ She is from Berkeley, Calif. and can be reached at leela[at]princeton.edu.

Emily Chien is a News contributor for the ‘Prince.’ She is from Arcadia, Calif., and can be reached at emilychien@princeton.edu.

Sena Chang is a senior News writer for the ‘Prince.’ She typically covers campus and community activism, the state of higher education, and alumni news.

MC MCCOY / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN Students Pointing at Paintings.

PUAM’s Modern and Contemporary art pavilion contrasts cultures and textures

By Lulu Mangriotis Contributing News Writer

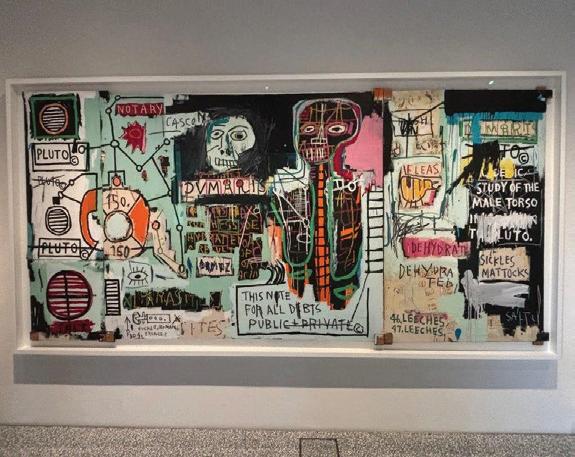

The Princeton University Art Museum’s Modern and Contemporary Art Pavilion, curated by Alexandra Foradas, spans textures, mediums, and styles, with the viewer seeing a new juxtaposition of pieces no matter where they stand.

The pavilion starts strong with Jean-Michel Basquiat’s “Notary” (1983) at the entryway. In this piece, and many of his others, Basquiat does not erase his work, instead letting the viewer in on his creative process. He crosses out words or letters just to later rewrite them, blurring the lines between draft and final product.

The pavilion’s walls do not reach the ceiling, lending an openness to the walk and encouraging viewers to look out across the gallery, where they will be greeted by a lively horizon at nearly any angle. In many places, it is possible to look through doorways to see large slices of the gallery, hosting a collection of radically different and curious pieces that draw you further in.

The collection boasts another Basquiat, a Yayoi Kusama painting, and multiple Willem de Kooning works. Further into the exhibit, different textures permeate the walls in a simple yet striking way. A frameless canvas with crumpled paper, glitter, sequins, and strings covered in acrylic paint — an untitled piece by Howardena Doreen Pindell (1977) — provides a range of textures in a contemporary medium.

Pindell was ahead of her time —

much of her art is similar to contemporary works. She used a hole punch to draw the viewer’s eye to specific points of light and color, according to the piece’s didactic. More typical works from the 1970s might include Andy Warhol’s bold striking prints and colors, but Pindell subverts this preconception with its simplistic and “undone” characteristics.

Foradas’s predecessor, Kelly Baum, started the curation for the pavilion, prioritizing the way pieces interact when choosing artworks and positions.

“My predecessor and colleagues chose and juxtaposed objects in ways that encourage the viewer to consider the impact of cultural contact and exchange,” Foradas wrote to The Daily Princetonian.

Whether steeped in meaning or entirely meaningless, the art in the pavilion has been organized to foster curiosity and inspire.

The gallery juxtaposes Sanford Bigger’s “Tunic” (2003), a feathered puffer coat, with Elias Sime’s “TIGHTROPE: ECHO?!” a rectangular sculpture made of reclaimed electrical wire and components. The aesthetic contrast of these two pieces in such proximity reminds the viewer of how conventional artistic boundaries are broken by contemporary artists. The sharpness of “TIGHTROPE: ECHO?!” stands out against the colored feathers of Bigger’s work.

Perhaps the most charming part of the pavilion is the Hans & Donna Sternberg Viewing Room attached in the northeastern-most corner of the art museum. There, the viewer leaves the layered views of textured contemporary art and finds a single work: Jane Irish’s “Cosmos Beyond Atrocity” (2024), embedded in the ceiling.

The captivating piece was commissioned for this specific room of the art museum, making for a cohesive viewing experience. While a mesmerizing distortion of angles and pastel colors warp the viewer’s perspective, an arm emerges from the sky and reaches towards them.

“The Museum was keen to work with a regionally based artist committed to the continuing vitality of painting; we were thrilled that Jane was so keen to mine the collections for inspiration and to draw on the past,” Museum Director James Steward said in a statement.

The new viewing room was adapted in modern style from a similar room in the old art museum.

“The other viewing room felt a little bit more like a living space with a restful feeling,” said Princeton resident Matthew Feuer. “[The new viewing room] is more integrated into the museum.”

However, Feuer noted that there were clear resemblances between the two: both featured identical circular win-

dows and were surrounded by trees, including the dawn redwood marking the eastern-most point the new museum reaches. Feuer also noted that the old room didn’t have any art — it was only a domestic escape from the rest of the museum.

“[The old room] was charming, but it was nothing like this,” Feuer said.

The new Sternberg Viewing Room coaxes the viewer into meditation, providing a haven of natural and artistic surroundings.

The pavilion as a whole will be ever-changing, as the museum will periodically update the modern art displayed.

Foradas has spoken with students and professors alike to gauge what the Princeton community looks for in contemporary art.

“A few key themes emerge: landscapes and borders, activism and liberation, ways of (hi)storytelling, questioning abstraction, and the relationship between art and performance and other types of liveness,” according to Foradas.

In the meantime, there is much art in which to indulge. This pavilion is sure to have something grab your attention, either with an eye-opening piece or a striking view across many.

Lulu Mangriotis is a News contributor for the ‘Prince.’ She is from New York City.

CALVIN GROVER / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN

“Blubber” by Ellen Gallagher in the Modern Art pavilion.

PUAM’s Ancient Mediterranean pavilion steps into the past, with a modern twist

By Zane Mills VanWicklen Contributing Prospect Writer

In the Princeton University Art Museum’s Ancient Mediterranean pavilion, each step carries you across centuries and civilizations.

Entering the pavilion, you tread upon a glass floor, beneath which lies a mosaic pavement once used as flooring in an elite villa in the ancient city of Antioch, now modern-day Turkey. You then pass a mixing bowl from the 4th century B.C.E. in southern Italy, featuring rich shades of black, orange, and white, which create stark contrasts and dazzling designs. Across from this, you see another vessel with art of a similar style; yet, rather than depicting a Greek god or a Roman emperor, it depicts modern city streets, telephone poles, and graffiti. This is the work of Roberto Lugo, a modern ceramicist who takes inspiration from ancient Greek art for his modern day works.

In an interview with The Daily Princetonian, Associate Curator of Ancient Mediterranean Art Carolyn Laferrière calls this contrast another one of the “surprising juxtapositions” the pavilion presents to museum visitors. Through this decision, she hopes to inspire “curiosity,” inviting people to ask “questions or … rethink assumptions.”

Laferrière also says that, in the Ancient Mediterranean, art was used to tell stories. In Lugo’s vase, one continues to see how “art is a really powerful vehicle for telling the stories of your community and of people who did extraordinary things.” Visitors are asked not to simply glance at a wall of ceramics but rather delve into the details of each piece, to ask how the works were made in the ancient world and how they are made today.

Echoing this point, art and archeology professor John Sigmier says

these surprising juxtapositions “make the past seem not so alien.” While the objects in the pavilion may appear “strange” at first, their pairing with a contemporary piece of a similar visual idiom allows visitors to view depictions of life in the ancient world as they would those of life in the 21st century.

The pavilion puts pieces that span great gaps in time and space in conversation with one another, seeking to accomplish the museum’s goal of promoting “dialogue among diverse audiences, foster[ing] inquiry and curiosity, and afford[ing] encounters that excite the imagination,” as stated in its mission statement. Sigmier said that the space achieves this goal and that he plans to bring the students in his courses to the pavilion and say to them, “Here’s what we’re talking about.”

The pavilion situates itself within a larger global community. Laferrière chose pieces from the ancient civilizations of “Near East, Egypt, Greece, Italy, and the Roman and Byzantine Empires,” to reveal that objects, people, and ideas moved across the Ancient Mediterranean; each piece is placed in conversation with one another. A visitor walking past various sculptures of Aphrodite from different time periods and places experiences the similarities between the pieces and the inspirations the ancient peoples took from one another.

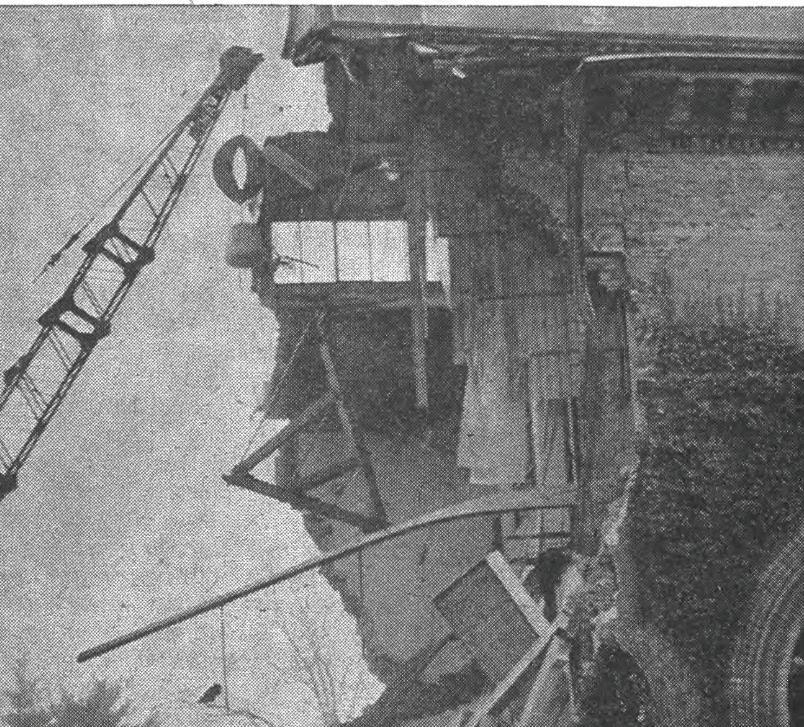

One fascinating element of the pavilion is that these pieces not only tell ancient stories but also give insight into modern geopolitical relationships. For example, former art and archeology professor Ernest DeWald Class of 1916 GS discovered that a marble head of a goat on display in the old art museum had been stolen from the Capitoline Museums in Rome during World War II. After learning this, the museum returned the piece to its arightful owners in

1953. According to Lafèrriere, Italy was so grateful for the gesture and, knowing it to be a favorite of the students, returned it to Princeton. Beside the piece is a photo of the ceremony in which it was bestowed upon the University.

These works thus span great gaps both in time and space. The visitor, in perusing the pieces, travels these distances with single steps, one moment examining a vase from fourth century B.C.E. Greece and another a fragmented statue from second century C.E. Rome. In organizing the pieces, Laferrière aimed to highlight the “range of lived experience that was available in the ancient world.”

Each of the works holds a story. Whether in “surprising juxtapositions” or clear pairings, the artwork whispers tales of war, love, ritual, and everyday life to its visitors.

The pavilion presents these works in all their uniqueness and splendor, telling a story not just of the diversity of these civilizations and the connections to modernity

but of a world in which we are all connected, where we are inspired by one another to bring forth newness and originality.

Laferrière wants visitors to leave with a sense of “curiosity” and “to think through some of the questions that the ancient objects are asking of themselves,” for many of them we continue to ponder today.

Zane Mills VanWicklen is a contributing writer for The Prospect and a member of the Class of 2029. He can be reached at zm6261@princeton.edu.

ZANE MILLS VANWICKLEN / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN

Two-story conservation studios open alongside new art museum

By Victoria Davies Head News Editor

For the last five years, Princeton University Art Museum conservators have been working out of a temporary building 15 minutes away from the University, overseeing the repair of over 300 objects and paintings.

Now, the conservation team has a new home in the brand new, two-story Paul & Heather Haaga Conservation Studios, equipped with suction tables, fume hoods, and an X-ray room in the new art museum building.

“Having more space and more room for specialized equipment and materials is going to really expand what we’re able to do internally as a department,” said Elena Torok, who works on object conservation, during a tour of the studio.

Bart Devolder, a conservator specializing in painting conservation, has been with the art museum since before the new space was designed. He worked closely with Samuel Anderson Architects to design a conservation studio with the right space and equipment to bring in conservators with different specializations.

The two conservators moved into the nearly pristine studios only recently, with conservation work yet to start.

“We’ve started to make sure that everything that’s here functions properly,” Devolder said.

A significant amount of space on the first floor of the conservation studios is dedicated to paper. This includes a suction table — a table with a humidity-controlled acrylic dome over it — as well as a giant sink fitted with taps for deionized and heated deionized water, and tables that are lit from below.

The other side of the room is primarily for object conservation, with a fume hood — a cupboard designed to extract vapors and fumes — for small objects and moveable tables for larger artifacts. There are also a number of “trunks,” which have a similar function to the fume hoods.

“We can sit at a table and work and then pull the solvent extraction over to us,” Torok said.

The first floor also includes a room for repair work “that’s loud or noisy,” according to Devolder, and is also equipped with a laser.

The second floor of the studios features a mixture of adjustable easels and microscopes, alongside suction and regular tables. The pyramid-shaped roof of the pavilion is visible from the inside, designed to only let in sunlight from the north. Devolder notes that painters and conservators in the northern hemisphere have preferred north light for centuries. It’s favored for being softer, more consistent, and colder than south light.

The second floor also includes a large suction table — custom-made and shipped from Australia — which heats up and will be used for painting conservation. Devolder plans to use it for Richard Phillips’s 1716 painting “Jonathan Belcher (1682–1757),” which awaits repair on a nearby table.

“This one would be really nice to now put on this table, do the suction which helps to flatten down,” he said. “The next thing would be to fix these tears … hopefully I can re-stretch it and then clean it.”

A lead-lined X-ray room on the same floor will allow conservators to examine the condition of artworks and identify forgeries, among other purposes.

The conservation studio shares the pavilion with one of the six object-study rooms in the museum, which are spaces designed for teaching and close study of objects. Arranged seminar-style, the object-study room has a wall of cabinets displaying a colorful assortment of objects: dyes, glues, and small artworks used for demonstrations.

While Princeton students won’t be able to do conservation work in the studio or the object-study room, the conservators plan to host lecture-style sessions and demonstrations explaining conservation processes while showcasing artworks.

Devolder and Torok hope to bring

in summer interns from different conservation programs across the country. This is not currently an option available to Princeton students, although Torok is “hopeful that there will be chances in the future to work with undergraduates in an internship role. We’re just not quite there yet.”

With the new space almost fully operational, both conservators are looking forward to getting started properly.

“A lot of the objects that come through the studio come to us because they’ve been requested to go on view … so as all of that starts to roll forward, we’ll have new projects in the studio too,” Torok said.

The conservation studios will have visiting hours each month, with the next scheduled for Dec. 11 from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m.

Victoria Davies is a head News editor for the ‘Prince.’ She is from Plymouth, England and typically covers University operations and the Princeton University Art Museum.

VICTORIA DAVIES / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN Table in the Conservation Studio.

Despite crowded central displays, the Ancient Americas pavilion gives some works space to breathe

By Cynthia Torres Associate News Editor

In the Art of the Ancient Americas pavilion at the new Princeton University Art Museum, the first thing one notices is the crowded, dense displays in glass cases wrapping around the museum’s central Grand Hall.

But while plates are next to plates and vases next to vases, the dense displays appear less important than the thoughtfully displayed objects found in the rest of the pavilion that are given appropriate space, sometimes with 360 degrees of viewing.

“The Princeton Vase,” one of the museum’s most iconic pieces, has its own dedicated case in the pavilion. A Mayan chocolate-drinking cup inscribed in codex style, the vase presents a story depicting human sacrifice, calling upon the viewer to continually rotate around the vase and reveal the story told through rich iconography.

The pavilion also features several other Mayan drinking cups, called uk’ibs, with inscribed images and a story told by rotating the vase. Some other Mayan drinking cups tell more pivotal stories for Mayan history. One uk’ib depicts the story of the infamous defeat of major underworld Gods, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, and another tells the story of the annual cycle of rebirth of the maize god, Hun Hunahpu. The displayed uk’ibs date back to the second half of the first millennium.

Outside of ceramic vases and plates, ceramic figures are on display throughout the pavilion. The Jaina figurines were particularly eye-catching,

displayed in a line directly at eye level with their earth tones contrasting with the navy blue wall behind them.

The Jaina figurines were from 600–900 A.D. and associated with the islands of Jaina and Uaymil off the west coast of Mexico. Each of the figures represented different noble Mayans with various court positions and genders. The didactic explains that these figurines were often unearthed by looters and presumably associated with burials.

Museum visitors Kruti Ramani and Sabrina Yanetta described the collection as “very expansive.”

“There’s so much to see, to look at. You see it once, and then you walk around the second time you see

stuff you didn’t see the first time,” Yanetta said, describing the circles she walked in the relatively small gallery.

Representing over 5,000 years of art crafted by indigenous Americans from Alaska to Chile, the collection varied across many empires across the North and South American continents.

Another compelling aspect of the Ancient Americas pavilion was the small study cases, something not available in most other pavilions in the museum. Featuring objects smaller than an inch long, the study tables provide a space in the center of the museum to examine individual objects.

Artifacts include a series of metal figures and ornaments from Qhapaq

Hucha, an important sacrificial site for subjects of the Inca Empire. Metal headdress ornaments and chest plates from Peru during the first millennium are also available for close study.

The Art of the Ancient Americans pavilion is not ancient in any way. The pavilion is modern and thoughtfully juxtaposes the centuries-old artwork with a sleek design, breathing in new life and appreciation to previously forgotten art.

Cynthia Torres is an associate News editor and archives contributor. She is from New Bedford, Mass. and typically covers University administration. She can be reached at ct3968[at]princeton.edu.

CYNTHIA TORRES / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN Jaina figurines.

CYNTHIA TORRES / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN Displays surrounding the Grand Hall.

CYNTHIA TORRES / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN Entrance of the Art of the Ancient Americas pavilion.

CYNTHIA TORRES / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN The “Princeton Vase” displayed in the Art of the Ancient Americas.

Transcending dimension: PUAM showcases photography through Peter Bunnell’s objects

By Michael Grasso

Contributing Prospect Writer

What does a photograph look like? Is it just a picture pasted on a wall, or is it something you can hold and move with? Maybe, according to Peter Bunnell, it’s all of the above.

This is the question the Princeton University Art Museum (PUAM) wrestles with in its first photography exhibit. The idea comes from Bunnell, a legend in the history of photography and the first endowed professor of photography history in the U.S. His quote, “What Photographs Look Like,” is the core theme of the gallery. The description on the wall reads, “Bunnell used the phrase to upend his students’ expectations of photographs as strictly two dimensional prints and to invite delight in the expansive nature of the medium.” I took a walk through the gallery to determine if it effectively conveys this theme of transcendence through medium and surprise. The pavilion has only one way in: a confrontation with Narcissus. The colossal piece that characterizes the gallery, Vik Muniz’s Narcissus from his series “Pictures of Junk,” towers over its onlookers. Due to its size, it completely blocks the viewers from seeing the rest of the gallery; one must travel around Narcissus in order to see the rest. Playing with perspective and distance, Narcis-

sus delights from afar with its reproduction of the 16th century painting by Caravaggio.

Its magnificence reveals itself by looking closer and seeing that it is entirely composed of pieces of trash, arranged by Muniz’s assistants. Not just a photograph, but a living piece of artwork and sculpture, Narcissus encapsulates the idea of surpassing the medium of photography and entering other worlds. This makes it an apt choice to begin the viewer’s experience of this gallery.

“I think it’s fantastic. I think it manages to pack an encyclopedic history of photography into an intimate space,” said Monica Bravo, an assistant professor of art and archaeology who specializes in the history of photography and modern art in the Americas.

Bunnell’s legacy is celebrated with a display of his personal collection of “What Photographs Look Like,” which includes objects like magazines, postcards, and even an albumen print of Nassau Hall. Bravo told the ‘Prince’ this collection of Bunnell’s provides “a range of different photographic processes as well as formats, and any idea of photography in an expanded field too.”

This collection surpasses the two dimensions that often constrict photography, and there are plenty of videos featured next to images around the gallery. Bravo expressed how she thought the

two could be mixed, saying, “I actually always believe that photography should be taught in relation to other media because photography exists in a larger visual ecosystem. So for me, it was very effective to see photography placed next to video.”

However, one piece fits awkwardly amid the rest. Wu Tsang’s Miss Communication and Mr:Re is a two-channel film, presented by two video screens parallel to each other. Mounted on the back of a dividing wall, Tsang’s film is accompanied by two speakers projecting separate voicemail messages of the subjects shown on screen. They look directly at the camera, expressionless. Although video and photography work in relation to each other, this piece interacts oddly with its environment.

The two voices are muffled in the noise of the other, and the flat facial expressions provide little to no enrichment when regarding for more than a couple seconds. It lacks congruency with the rest of the gallery due to its awkward placement, facing Bunnell’s collections and mounted on a faux-wall. A little forgettable — and more experimental than the rest — Miss Communication and Mr:Re transcends the realm of photography solely by being a film, not as an interesting merge of the two art forms.

Besides that piece, the gallery comes together cohesively. The multitudes of

black and white filling the walls mask subversive elements of the artwork. One may wonder why a drawing finds itself in the photography gallery, but Sir John Herschel’s “Castle of Chillon” camera lucida drawing evokes the beginnings of the art form. The camera lucida was an optical device invented to superimpose an image of a certain object on a canvas, allowing for smooth tracing.

Paired with the history of photography, Bunnell’s legacy is at the forefront of this first exhibition. Bunnell died in September 2021, just mere months after the old art museum was demolished. People familiar with the history of photography will likely be familiar with his impact, and the importance of his centrality in the exhibit. However, if this is someone’s first entrance into photography, they may not understand the emphasis.

That does not mean they will not learn from him, as Bunnell was, above all, a teacher. His teaching persists in PUAM’s photography gallery, as the photographs, photo sculptures, camera lucidas, and more show “what photographs look like.”

Michael Grasso is a contributing writer for The Prospect and a member of the Class of 2029. He can be reached at mg7604[at] princeton.edu.

MICHAEL GRASSO / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN

A portrait of Peter Bunnell, along with some of his collected photographs.

MICHAEL GRASSO / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN

‘Europe is and has long been a crossroads’: the European art pavilion’s new perspective on a global continent

By Devon Williams

Contributing Prospect Writer

As I first stepped into the European Art pavilion, I found myself surrounded by color: maroon, gold, and blue hues covered the walls as ceramics, paintings, and prints from diverse eras, artists, and regions converged. Yet the pavilion goes beyond unifying an eclectic color palette — it also offers a powerful message on cultural intersection.

One of the works I was most moved by was the renowned Alfred Stevens painting, “The Psyché (My Studio).” Its intricately painted refined art studio space, with the delicate woman peeking from behind the mirror to meet my eye in the reflection drawing me over for a closer look, strikingly contrasts a painting by the lesser known Berta Wetman’s “Interior.” Wetman’s painting mirrors the subject matter and perspective of Stevens’ work, but with a grittier, simpler beauty absent of a female muse.

The curatorial choice of creating conversations between known and lessknown artists complemented one another, encouraging me to learn more about every piece. The pairings brought pieces unfamiliar to me to the forefront, expanding the context and meaning of the piece alone into one that encompasses the works on the walls surrounding it and the pavilion itself.

Even the corridor that flanks the pavilion’s entrance highlights pieces of seemingly non-European origin. Three central objects dominate the corridor: the Incan Cup of Montezuma brought to Spain in the 17th century, an Indian ewer made for the

British Empire, and a West African ivory spoon brought to Portugal. According to Associate Curator Alexandra Letvin, the pieces are “not European, but that circulated in Europe.”

While this may appear strange, Letvin says this choice was intentional: “objects that circulated in Europe had a European provenance unintentionally, or were intentionally made for European audiences.”

Letvin added that she aimed to “show Europe looking outwards, not just looking inwards.”

“Europe is and has long been a crossroads — a diverse continent with many cultural traditions,” said Annemarie Ike GS ’23, Lecturer in the Princeton Writing Program and Art History Ph.D.. Display of European art has often centered on white, traditional voices while obscuring the diverse and complex nature of populations colonized and integrated. Yet the new openness and interdisciplinary nature of the museum help convey this reality, as a metaphor for the continent itself: porous, dynamic, and in constant exchange.

In the University’s old art museum, European art dominated the main level, leaving little room for art of other cultures. The new museum equalizes this space, with each pavilion sharing roughly the same footprint, and an open floorplan that allows each room to flow into the other. As I walked through and inevitably got lost, this openness and exchange between cultures and histories certainly came through in proximity between diverse pieces alone.

“The collection is laid out more or less chronologically and geographically,” Letvin explains. The Art Museum has long been a teaching center for professors and students in the Art History department, and Letvin has intentionally maintained this teachability by keeping content in thematic groupings in addition to chronological organization.

To achieve this fluidity, Letvin outlined three driving points, beginning with, “Europe’s place within a global world,” she explained. Works from India, Africa, and more find a home directly in the pavilion, creating a new and complex vision

of Europe and its relationship with other countries.

“I like to push back on the term masterpiece. And so one thing that we started using when we were thinking about these galleries, but really the whole museum was the idea of anchor objects,” Letvin said. Anchor objects are used to engage other works to generate new interpretations of the work. Examples range from Gérôme’s “Napoleon in Egypt” and Monet’s “Water Lilies” to works by unknown artists.

The well-known works are recognizable but don’t dominate — they contextualize and inform the works that may be more obscure. This representation of lesser-known works and works across cultures even lends itself to the more famous pieces like Manet’s Woman with a Cigarette, which, as Iker noted, “because of the uncertainties about the identity of its subject, seems to be at home in a new way in the new [pavilion].”

Exploring the pavilion’s four galleries, the works seemed to flow into one another, a woven tapestry of intersecting media, cultures, and time periods. The contrast between these artistic factors and origins kept me curious about every piece and its place in the world, and that curiosity could have kept me walking around for hours.

This ambitious philosophy of centering non-European art is realized through Letvin’s choice to host a case of works in

the central corridor of the pavilion as opposed to a single “important painting.” The case of works highlights the “circulation of commodities throughout Europe and so, in a sense, becomes a more personal reflection of the stories that these three objects are telling.” This recenters high art on a personal level, a theme that aids the sense of an interconnected global community on an intimate scale while simultaneously rewriting what defines ‘European art.’ Many visitors come to museums seeking the most famous pieces, but in doing so, they miss the chance to truly learn from what they are experiencing. In choosing pieces that are less well known or unconventionally European, visitors can expand their idea of what art is worthy of witnessing.

Through this focus on exchange in geography, layout, and media, Letvin leaves visitors with a clear message: “I hope that they leave the pavilion thinking that Europe is more connected to the world around it, and I also hope that they will see that Europe’s boundaries shift over time ... I hope that people understand [the Art Museum] as a place within a connected world.”

Devon Williams is a contributing writer for The Prospect and a member of the Class of 2028. She can be reached at dw9268@princeton.edu.

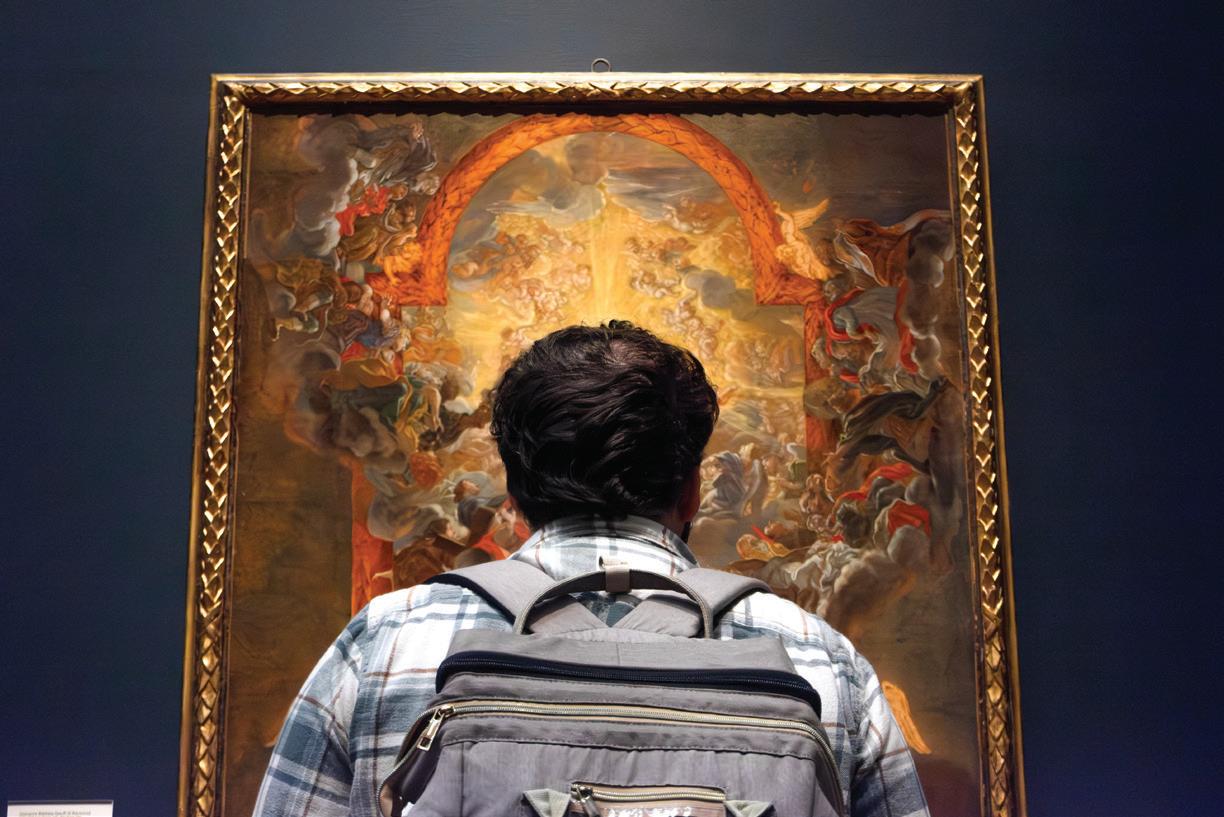

MC MCCOY / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN Viewer in European Gallery.

New museum’s Asian art pavilion undertakes a near-impossible task to mixed success

By Kate Chun Contributing Prospect Writer

Showcasing artworks from Chinese handscrolls to Pakistani Buddhist figurines, the Asian Art Pavilion in the newly renovated Princeton University Art Museum undertakes a near-impossible task: representing the vastness of Asia in a room only slightly larger than a lecture hall. I entered the Pavilion with the expectation that the layout of the room would be by country — and my expectations were both met and broken.

“It’s an incredibly difficult thing to bring together objects from the enormous spatial, temporal, and cultural reach of what we describe in one short word as ‘Asia,’” Professor of Japanese Art History Rachel Saunders wrote to The Daily Princetonian.

As I entered, I immediately noticed that East Asian cultures were integrated into varying themes, such as ‘Lacquered Objects.’ This section featured lacquerware, a medium that originated in ancient China. With a collection spanning both time and geography, from the Chinese Eastern Zhou dynasty (771–256 BCE), the Japanese Edo period (1603–1868), and the Iranian Safavid dynasty (1501–1736), this art form highlighted the spread of Chinese influence across the continent, traced through a singular common medium.

The Pavilion’s South Asian and Southeast Asian pieces were isolated on the left side of the gallery, creating a feeling of division. As far as I could tell, the only representation of South and Southeast Asia comprised a small case featuring Buddhist sculptures and religious figurines from Cambodia, Pakistan, and India.

Given that there is also a collection of Buddhist sculptures housed in a hallway outside of the pavilion, I felt the section lacked a

variety in subject matter. While I expected to see secular items like household objects and ceramics, as I had seen in other parts of the gallery, the display was limited to religious items.

As the back wall inside the left wing was dedicated to the Silk Road — thus featuring more Chinese art — a South Asian and Southeast Asian presence felt like an afterthought.

The pavilion’s curator, Zoe Kwok, is “a Chinese specialist that is working with other colleagues to curate the entire collection, leading to people moving outside of their specialities,” Yuchen Wang GS, a Ph.D. student in the Art and Archaeology department, said.

While the museum is only currently showing 5 percent of its whole collection, according to Wang, the Pavilion may begin to rotate through its pieces.

However, there were also aspects of the pavilion I enjoyed. I appreciated its overall structure, which fluidly blended scrolls, vases, and paintings, holistically embodying the vibrant history of East Asia.

Instead of the familiar cultural segmentation or chronological order that can constrain Asian history to Western stereotypes, the room’s venture to interweave varying pieces — old and modern; Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Tibetan — placing them in conversation with one another, showcased a more nuanced perspective.

Even within the same culture, pieces interacted thoughtfully with one another. A case featuring Korean ceramics — including pieces such as a maebyeong, a Korean plum-shaped bottle from the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392); an 18th-century porcelain jar; and ceramics by modern artist Young Sook Park — led me to compare the diverse styles throughout Korean history.

On the right side of the pavilion,

I was greeted by a fascinating contrast of Japanese prints. The layout guides viewers through the transition from the Edo period’s woodblock prints of ordinary people to landscape images of bridges and gates, showcasing the impact of photography on Japanese art. Here, I could see the clash between modernity and the desire to hold onto traditional styles. I appreciated the pavilion’s decision to include modern photographs.

I also appreciated the pavilion’s juxtaposition of two large scrolls at the center of the back of the room. One was a handscroll by one of the Four Great Masters of Song calligraphy, Huang Tingjian, the other a more modern 2010 woodcut scroll by Ji Yunfei. The former was an example of “running script,” while the latter depicted the Three Gorges Dam migration and its effects on millions of people. The calligraphy scroll was filled with elegant characters, a traditional Chinese art form seen across various media. On the other hand, Ji’s scroll could be compared to a watercolor painting, with sketches of humans

and natural scenes to tell a story not with words, but visceral images. I enjoyed how much the works emphasized the artist’s role as a storyteller, their thoughts flowing out in different directions.

“[The Pavillon’s curators] reshape ways of how people understand. Instead of telling a narrative, they are trying to engage the viewers to think. The Museum is a space for viewers in dialogue,” Wang said.

Kate Chun is a writer for The Prospect and part of the Class of 2029. She can be reached at kc6370@princeton. edu.

seated in “royal-ease” pose, ca. 1250”.

American art pavilion sparks dialogue on America’s past and future

By Caroline Naughton

Contributing Prospect writer

Standing valiantly in front of an active battleground and Nassau Hall in the distance, “George Washington at the Battle of Princeton” by Charles Willson Peale was the first painting acquired by Princeton and, fittingly, the first one to be hung in the new art museum itself. The painting is a reminder of the longstanding history of Princeton and acts as a beacon for visitors of the Wilmerding Pavilion of American Art, asking them to explore and confront both the curated space and their ideas of America itself.

While the organization of the gallery can be disorienting at times, the pavilion is an intriguing take on the difficult task of representing the complexities of American history and identity.

While I had briefly spent some time in the pavilion during the museum’s student preview on Oct. 24, it wasn’t until my personal tour with Karl Kusserow, senior curator of the American Art Pavilion, that I truly digested it in full.

“A hallmark of this institution,” Kusserow said, “is the kind of mixing up of works of art from different places and different periods of time to suggest different ways of understanding. This whole installation is organized around that kind of juxtaposition.”

To this point, the pavilion attempts to prompt viewers to piece together the nuances of American history themselves, inviting discussions on protest movements, gender, and environmental justice.

The first example of this juxtaposition is in the arrangement of the George Washington display. The famous painting that greets all visitors of the pavilion is flanked by two busts of the first president. One, is cast in bronze and was previously owned by Thomas Jefferson, while the other, made of a metallic mirror-like material, was created by Hugh Hayden, a Native American artist. The piece, titled “Hanodaya:yas (Town Destroyer): Reflect,” was specially commissioned for this exhibit. Made

from a highly reflective material, the bust forces viewers to confront their own image and, in turn, Washington’s imprint on America. The bust’s base is made from a salvaged piece of ash to represent the burning of Native American villages.

When discussing the mistreatment of Native Americans and African Americans throughout American history, Kusserow said, “We try, in this pavilion, to engage the idea that it’s not just a matter of victimhood.

“They expressed their own agency in sort of combating a lot of the injustices that were inflicted on them,” he added.

Indeed, interconnectedness is the pavilion’s guiding principle. Pieces that seem unrelated at first glance enter into conversation when placed together. For example, “The Culprit Fay” by John Adams Jackson is a sculpture carved from marble from Carrara, a region in Italy scarred by centuries of mining exploitation. This sculpture sits opposite a clay jar by Pueblo artist Maria Martinez, who gathered her materials from the earth after seeking spiritual permission. Together, these pieces illustrate the contrast between Western exploitation of nature and Indigenous stewardship of it.

Opposite this arrangement is a display with similar messaging, an arrangement of various still lifes from the 19th century. Hung in chronological order, the earliest painting depicts natural produce with an arrangement of peaches. However, as the chronology advances, nature soon gives way to the man-made, transitioning to natural products like cheese and champagne, and eventually to solely manufactured goods. This progression reflects a shift from harmony with nature to domination over it, mirroring America’s industrial and environmental trajectory. In the very back of the pavilion lies the Arts and Crafts section, by far my favorite as someone interested in both textiles and ceramics. In a glass box display, there were several Tiffany glass designs and ceramic items, all in organic shapes that contrasted the manufac-

tured approach of the time period. The display’s ceramic items are classified as Newcomb Pottery, a form that evolved from Tulane’s Newcomb College for women.

During a lull in our conversation, Kusserow pointed me toward his favorite wall in the pavilion, showcasing two quaint landscapes: one of ships in a harbor, and the other a nameless marsh. While unassuming beside the Bierstadt landscape, these pieces emphasize the interconnected thinking behind the curation of this gallery.

Another notable moment of contrast lies around the corner from the Washington portrait in the Libby Anschutz Gallery. Here, Renee Cox’s revisionist photograph, “The Signing,” emulates the famous “The Signing of the Constitution” painting, replacing the founding fathers with people of color. Just beside this powerful photograph sits the massive painting by Thomas Sully of Mrs. Reverdy Johnson, the wife of Reverdy Johnson, the lawyer of the slaveowner in the Dred Scott decision. The connection between the two pieces took me aback; it felt as though history was confronting itself in this little corner of the museum.

While thought-provoking, the displays can also read as busy and disjoint-

ed. I felt the logic behind the pavilion’s curation best revealed itself after taking extended time to linger on each work. While it is likely not possible for a casual museum guest to reflect on each arrangement in the American pavilion, it is a meaningful endeavor for those who take the time.

In the end, the pavilion’s strength lies not in seamless order, but in its deliberate tension. Those who take the time to read, to look, and to think will find that the pavilion offers not just a gallery of art, but a space for a dialogue that challenges, questions, and, ultimately reimagines the story of a nation.

Caroline Naughton is a contributing writer for The Prospect and a member of the Class of 2029. She can be reached at cn8578[at]princeton.edu.

CAROLINE NAUGHTON / THE DAILY PRINCETONIAN

“George Washington at the Battle of Princeton” by Charles Willson Peale at the Princeton University Art Museum.

‘Princeton Collects’ is too chaotic for cohesion

By Sena Chang Senior News Writer

In no other room than the “Princeton Collects” exhibition could a punch bowl from China’s Qing Dynasty, a skirt from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and a Willem de Kooning oil painting sit so close to one other. The exhibition — borderless, eclectic, and cross-temporal — is located in the southeast pavilion of the new art museum, one of two main temporary exhibition spaces.

“Princeton Collects” celebrates more than 2,000 works donated to the museum by more than 200 members of the Princeton community between 2021 and 2025. Around 150 works are on view in this inaugural exhibition. From abstract Expressionist canvases to 19th-century British portraiture and Chinese earthenware, “it is … impossible to impose on such sprawling gifts a single organizing principle,” the pavilion description reads.

At first glance, the effect can be dizzying. The high-ceilinged room, combined with the lack of a cohesive theme or motif, struggles to orient the visitor as they enter. Immediately after a towering wall featuring donors’ names, sculptures of all sizes stand at the center, with photographs of tattoos and oil paintings housed in frames big and small on the wall behind. Everything and nothing draws your attention.

The further you venture inside, the more messy the pavilion appears. Ai Weiwei’s “Porcelain Cube” (2009), an ornate three-dimensional ceramic cube, sits in the center of a collection of oil paintings. Nari Ward’s “Scape” (2012), a shredded fabric ladder, stands just around the corner from the cube. At every turn, you are hit with an amalgamation of diverse artistic media — fabric, ceramic, painting, and

photography — that at times feel overwhelming and excessive.

Even the positioning of certain objects — for example, a Qing-era Punch bowl sitting below an etching and engraving depicting William Hogarth’s “The Gate of Calais or The Roast Beef of Old England” (1748–49) — can seem almost arbitrarily placed with no concern for visual or historical continuity.

Upon closer inspection, however, viewers will see a deeper artistic connection between the two works.

As the punch bowl’s didactic reveals, the Chinese pottery showcases a reinterpretation of Hogarth’s painting. The two works, in effect, embody the circulation of ideas and aesthetics along trade routes that connected two very different worlds.

In these ways, moments of cohesion emerge from the exhibition’s apparent chaos as artworks reveal unexpected continuities across such an eclectic collection. Connections are made between seemingly disparate artworks, helping the viewer make sense of the visual commotion that permeates the pavilion.

For all its eclecticism, visitors enjoyed the diverse works of art showcased in the pavilion.

“I like that the colors don’t match,” said Elizabeth Watson of Ewing, N.J. “The pieces go together, but it’s because somebody had a wonderfully fun time figuring out what goes with something else — I think that adds to the visual intrigue.”

Amid the visual noise of the space, anchoring the exhibition is Irish artist Sean Scully’s “Night and Day” (2012), a massive painting of white, gray, and milky rectangles. Around it, tigers on ancient papyrus, porcelain deities, and oil landscapes draw viewers into fleeting visual affinities rather than clear narratives. Meanwhile, the set of

Asian scrolls adjacent to Scully’s painting features works from 1761, the mid-1800s, and 2006, spanning Japan and China. These unexpected dialogues between time and geography lend credence to the pavilion’s description of a “museum in miniature.”

“The collection is so big, and the way the materials are presented just keeps me interested,” Watson said. “Just keeps me looking, and looking, and looking, and exclaiming.”

Still, “Princeton Collects” occasionally feels less cohesive than other pavilions in the museum; in some ways, its lack of a unifying artistic theme feels foreign within the broader museum, where pavilions are mainly grouped by geography.

While the exhibition succeeds as a study in contrast and cross-cultural influences, its spatial isolation raises questions about curatorial strategy. The thematic looseness — though deliberate — can leave visitors unsure of where to look or how to linger. The exhibition seems noticeably quieter than its neigh -

boring collections, with viewers drifting in and out in a matter of minutes.

The spirit of the exhibition, however, is a fitting debut for the new museum, inviting viewers to reconsider how art travels, adapts, and accrues meaning across time and culture.

“Princeton Collects” mirrors the museum’s own moment of renewal, using the renovated architecture and non-hierarchical organization to invite visitors to think about connections between eras, materials, and makers.

The pavilion’s simple layout, coupled with lots of open space, makes the pavilion easily re-purposable for future temporary exhibitions. But the current exhibition fails to bring together the space.

Sena Chang is a senior News writer for the ‘Prince.’ She typically covers campus and community activism, the state of higher education, and alumni news.

Eclectic pairings and interconnecting cultures: Transition spaces in the art museum

By Haeon Lee & Amaya Taylor Contributing News Writers

In the Princeton University Art Museum, the art is everywhere — including in the hallways.

Upon ascending the Grand Stair of the museum up to the collections, the first pieces of art that many visitors see are those of the Orientation Gallery, which rings around the main staircase. Before even entering one of the seven pavilions dedicated to art, visitors pass through various hallways and transitional areas that double as compact galleries dedicated to art from the Islamic World, Latin America, Native North America, South Asia, and Africa.

The Orientation Gallery makes up one of the most unique areas of the whole museum, with works such as Andy Warhol’s “Blue Marilyn” (1962) juxtaposed against a long assortment of European Renaissance stained glass pieces.

“I like the mix of modern and ancient, the mix of time frames. I can’t think of another museum where I’ve seen that,” said Sherry Friend, docent at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art, during a visit to the museum.

“The opening to the second floor of the museum is highlighting the fame of the museum, the fame of Princeton, and the caliber of art that they’re able to collect with their means,” said Madison Anderson ’27, an art history major and former member of the museum’s Student Advisory Board.

“Some galleries also serve as circulation spaces, we don’t see any of the gallery spaces in the building as ‘hallways,’” said Art Museum spokesperson Morgan Gengo.

Rather than simply connecting one gallery to the next, the circulation spaces present visitors with an unpredictable and diverse array of pieces. Tall glass cases above the Grand Hall, for instance, house a dizzying array of bowls, vases, and objects from a broad array of cultures. Meanwhile,

the Cross-Collections Gallery, located just outside of the Asian Art Pavilion, builds Josiah McElheny’s “A Twilight Labyrinth (Alchemy)” (2019) into a wall near a Spanish alabaster carving of a knight from circa 1500.

But unlike areas like American, modern, and ancient Mediterranean art, which have dedicated pavilions, the museum’s African and Latin American art is largely showcased in the hallways.

“The museum, I know for a fact, has a very strong Latin American art collection … and the Latin American Gallery of Art is quite literally a corner,” Anderson told the ‘Prince.’

Perrin Lathrop GS ’21, Associate Curator of African Art at the museum, wrote in a statement that the “interstitial galleries emphasize ideas of cultural contact and exchange.” African and Latin American art galleries “are present throughout the museum and are inescapable,” she added.

“You can’t escape the fact that there will be art in that hallway,” Anderson said. “You’re going to have to pass by it, so why not look?”

Before the museum’s renovation, European, American, and contemporary art dominated the main upstairs

floor, while non-Western art was placed in the downstairs galleries, where there were fewer visitors.

“The new museum, by putting art on the same physical level, helps convey that all art is important, it’s valuable,” said Annemarie Iker GS ’24, a scholar of modern art.

“The African art galleries have increased in size by some 700% from the previous building and are strategically located adjacent to the galleries for art of the Islamic world and the ancient Mediterranean,” Lathrop added.

Many of the pieces on display in the African art collection are attributed to an “Artist unrecorded,” a label that Lathrop wrote “recognizes the individuality of the person who created the work, before providing information about their culture and geographic origin.”

Similarly, the Latin American and North Native American art galleries, located by the entrance to the American art pavilion, include many ceramic figures, vessels, and objects by artists that are unidentified, such as the “Model yaakw (canoe)” (before 1882). Most modern art from the cultures showcased in the transition spaces, however, is located in the Modern and

Contemporary art pavilion.

“I’m not sure how much of this at the time people would have thought of as art,” Friend said, adding that the frequency of unnamed artists for certain cultures may be a consequence of the blurred line between art and product.

From iconic paintings of mythological and historical scenes to obscure Attic and ceramic Olmec pottery, the museum’s transitional spaces have much to offer. Despite not having their own dedicated pavilions, the African, South Asian, Native North American, and Latin American art scattered across the museum’s second-floor galleries provides visitors with the opportunity to learn about the cultural histories, traditions, and identities of artists from around the world.

Haeon Lee is a News contributor for the ‘Prince.’ She is from Brooklyn, N.Y. and can be reached at hl1389[at]princeton.edu.

Amaya Taylor is a News contributor for the ‘Prince.’ She is from Memphis, Tenn. and can be reached at at9074[at] princeton.edu.

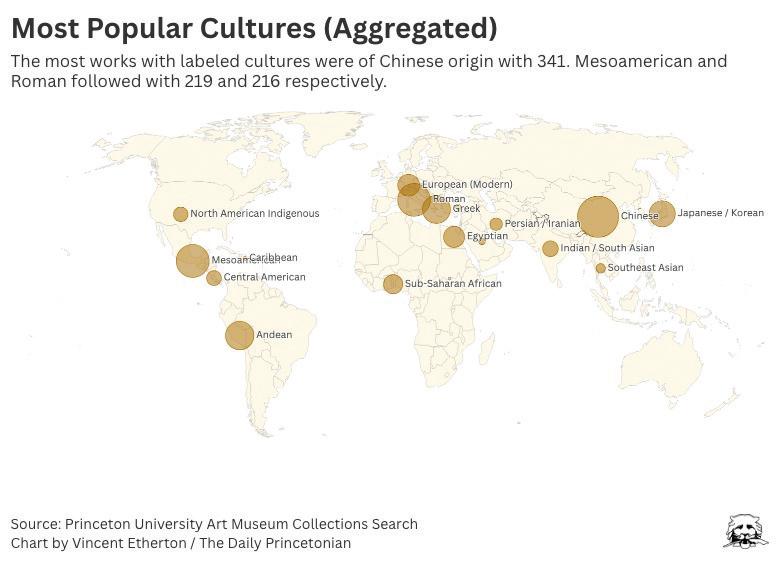

After nearly five years of renovations, the Princeton University Art Museum has reopened, showcasing more than 3,000 pieces from a collection of over 50,000. Featuring household names like Monet and Warhol alongside works from more obscure or even unidentified artists, the data reveals a varied curation across over 500 artists and 1,000 distinct artistic mediums in Princeton’s newly renewed public art experience.

The Daily Princetonian analyzed trends from the art museum collections database, focusing on the 3,241 artworks currently on display out of 58,348 total in the database.

Where the data was consistently formatted, the ‘Prince’ used simple text-analysis machine learning (ML) techniques — word tokenization (breaking text into words or phrases) and clustering (grouping similar items based on shared features) — to organize the mediums and dates of works into broader categories.

The art museum opened to the public on Halloween, drawing more than 20,000 visitors over a 24-hour opening event.

Artists

The ‘Prince’ first looked at a breakdown of credited artists on display at the art museum. Any art piece in the collections database whose artist description mentioned “unknown”, “attributed”, “unrecorded”, or “unidentified” were removed for this analysis.

There are 514 credited artists with works on display, 14 of which have more than four works on display. The artist with the most works on display is Eleanor Antin, mostly as part of a project called 100 Boots, which documents the staged travels of 100 pairs of black rubber boots. The project consists of 51 postcards of the boots photographed in a cross-country journey.

The ‘Prince’ used the Bosworth Art score, a modification of the Bosworth score, to analyze how well-known artists are based on Google Trends data. The score compares an artist’s number of monthly searches to Toshiko Takaezu, former Princeton art professor and creator of “Dialogues in Clay,” the welcome exhibit to the museum.

BY THE NUMBERS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUM:

Andy Warhol, Claude Monet, and Benjamin West hold the top three Bosworth Art scores, averaging roughly 84, 80, and 78 respectively for 2024. This means that each of these artists were searched about 80 times more often than Takaezu.

By this metric, seven of the fifteen

most recognizable artists are painters and four are photographers or print artists.

Mediums

The original dataset from the art museum’s collection search included 1,084 different art mediums. To make these easier to study, the ‘Prince’ used a machine learning technique called k-means clustering to group similar mediums into broader categories to analyze.

The original 1,084 medium entries were grouped into 40 broader categories, chosen using common data science methods to capture meaningful differences between mediums while keeping the categories simple enough to interpret.

More than 240 works were categorized as either “black-figure” or general ceramics. Roughly one-quarter of these originated from Greek or Classical Greek culture, many representing black-figure pieces, which are bowls and vases decorated with ornamental motifs along the sides.

Almost 99 percent of oil paintings, the second most frequently used medium, were not given a cultural label.

Cultures

There are 252 unique cultures on display at the art museum. Almost two thirds of works with labeled cultures had either East Asian, Mesoamerican, or Greek and Roman origins. 1,543 works had no culture label, usually indicating modern or contemporary art.

Image Analysis

The Museum’s dataset contained 2,384 unique images. For each, the “dominant color” was found by averaging RGB (Red, Green, Blue) values across all pixels. k-means clustering was used to group these works into eight groups, with each sharing similar color profiles.

Most of the works on display at the museum have muted color tones on average. About two thirds of all works have some shade of gray or beige as their average color — categorized into clusters representing the colors stone gray, ash brown, beige gray, and light sand. Golden tan, a smaller group of 253 works, has a yellow/gold average color, rep-

resenting many of the images of clay sculptures. The smallest group, slate blue, is a blue-gray color and contains many of the more colorful and modern works on display at the museum.

The ‘Prince’ also analyzed the relative brightness, saturation, and vibrance of works using HSV (Hue, Saturation, Value) codes. This was broken down by the ten most frequent cultural clusters, identified using k-means clustering.

Most of the artistic cultural groups had similar brightness levels, with Roman works falling below the average by 5.3 percent and works in the Greek (other) category having 7.1 percent higher brightness levels than average.

Olmec art, recognized for its stone sculptures and expressive human features, shows a 36.5 percent higher saturation than average. Etruscan art, known for its terracotta sculptures and ornate pottery, has a 15.3 percent higher saturation than average. In contrast, Japanese works, Egyptian works, and Non-Attic Greek works register about 10 percent lower saturation scores, suggesting subtler or more restrained palettes.

Differences in vibrance values are more moderate, with Chinese, Roman, Japanese, Maya, Nasca, and Olmec artwork being close to average in value. Notably, Etruscan works have a vibrance value 17.5 percent higher than average, while Egyptian works have a value about 10 percent lower than average.

The reopening marks an invitation to examine only a snippet of Princeton’s collections. By the numbers, the museum’s collection is vast and complex, hailing from many time periods and regions throughout human history.

All visitors are able to visit the Princeton University Art Museum’s collection of over 3,000 works for no cost.

Vincent Etherton is a head Data editor for the ‘Prince.’

Aayush Mitra is a contributing Data writer for the ‘Prince.’

MUSEUM 24 Hours in the

By Daily Princetonian Staff

In 1755, N.J. colonial governor Jonathan Belcher gifted his portrait to Princeton. It was hung in the prayer room in Nassau Hall. In 1777, the contents of the building were destroyed by fire.

Not to be deterred, the trustees began collecting art again in 1783. But a second fire in 1802 destroyed most of the collection, with Charles Willson Peale’s “George Washington at the Battle of Princeton” as one of the only surviving relics.

Shortly after, Professor John Maclean, a member of the Class of 1816, began rebuilding the collection with portraits of the University presidents — an endeavor to which he dedicated the rest of his life. Another fire raged in 1855, but this time, students and town residents were able to save the majority of the collections.

Princeton’s first museum opened in 1874 with these collections, displayed together in a dedicated space in Nassau Hall. Just 16 years later, a freestanding museum opened near Prospect House, costing just $40,000 at the start ($90,000 in total, or around $3.2 million today). This museum soon shared its space with the new School of Architecture, as well as the Department of Art and Archaeology, and expanded in 1923 to accommodate the departments.

Since then, McCormick Hall has stood in central campus, with additions and expansions being added to the complex throughout its almost 100-year tenure. The result? “A random and chaotic assemblage of additions in a host of disparate and even jarring historicizing styles,” or so predicted Professor Jean Labatut in the 1930s, as Museum Director James Steward

wrote in Renaissance: A New Museum for Princeton.

So in 2021, Princeton tore it down. After five years of construction, Steward promises that this building will be “a game changer for our campus, for our town.”

To usher in the opening, the Princeton University Art Museum (PUAM) held a 24-hour open house beginning at 5 p.m. on Halloween, welcoming almost 22,000 visitors. The Daily Princetonian was there the whole time, just in case a fire started.

5 p.m. — Steward opens the doors to the hundreds of people lined up outside of the building. Many are dressed in Halloween costumes, looking to party the night away surrounded by art.

5:11 p.m. — The galleries are filled with people; the lines going up and down the stairs are growing. In the Grand Hall, makeup artists are painting children’s faces.

5:31 p.m. — A family dressed as the Addams family walks past. They look incredible and are one of Senior Associate Director for Collections and Exhibitions Chris Newth’s favourite costumes so far. There are so many tiny children dressed up for Halloween as well.

5:40 p.m. — As people enter galleries, they’re asked to take off their backpacks and put them over one shoulder. People are also leaving food and drinks at the entrance of the galleries.

5:45 p.m. — I pet a golden retriever outside dressed as the cowardly lion. He is drawing a lot of attention, and he deserves it.

5:53 p.m. — The Modern and Contemporary Pavilion is popping. People like

Sonya Kelliher-Combs’s “Idiot Strings: The Things We Carry” (2017) in the middle. I’m sitting in the Hans and Donna Sternberg viewing room. I feel very calm right now.

5:59 p.m. — Right in the lobby, local resident Ashley Richardson and Assistant Professor of Molecular Biology Kai Mesa sport eye-catching Jackson Pollock-inspired costumes with splatter paint, a unique, on-theme outfit for the museum’s opening. “The energy feels high,” Richardson remarks.