October 2, 2025

Sponsored by:

Schedule a tour!

In Northern Liberties, Philadelphia Piazza Alta redefines modern luxury living with residences ranging from intimate studios to expansive penthouses. Every home is designed to inspire, with abundant natural light, spa-inspired baths, and chef-quality kitchens finished with a distinctly modern touch.

Unparalleled amenities elevate daily life, including a 25,000 sq. ft. fitness and recovery center, coworking lounge, private spa, and exclusive access to the Aqua Foro Rooftop Pool Club. With onsite parking, bike storage, and 24/7 concierge service, Piazza Alta is more than a home it’s a lifestyle.

Inquire today about our current offers.

o o er a closer loo at the hous ng s tuation e ond the m ths and m ster es he a l enns l an an nter ewed rst ear students to learn more a out the r e per ences n the college house s stem.

LUKE PETERSEN AND SKYLER FAN Contributing Reporters

Commonly held beliefs about different dormitories often guide first-year students’ housing decisions. To offer a closer look at the housing situation beyond the myths and mysteries, The Daily Pennsylvanian interviewed first year students to learn more about their experiences in the college house system.

Rooms and Amenities

While some college houses boast apartment-style suites with individual bedrooms, others offer a more traditional dorm experience with single, double, and triple rooms shared with roommates. Before the start of their first year, students are given the chance to rank

college houses according to their preference — a choice that re ects how they tailor their residential experience to their lifestyle.

College first year atherine uintanilla ranked Lauder as her first choice in the housing application because she desired more privacy. iven the number of students who rank Lauder first, uintanilla said she was pleasantly surprised when she was assigned there.

“I was very surprised when I got Lauder .” uintanilla said. “I picked it as my first choice because I value having my own space. The dorms in the uad are more social, but it’s

less private and more communal.”

utside of dorm rooms, each college house offers varying amenities in the common area. Hill has four lounges on each oor for students to study and socialize. All residents are assigned to one of the four lounge groups. College first year aynesha Mauvais, who is assigned to the blue lounge group, said she enjoys being able to meet new people easily by going to the lounges.

“The lounges are always occupied,” Mauvais said. “People are always talking, studying together. I feel very welcomed. If I ever need someone to talk to, it’s

easy to just walk out and find someone.”

Dining halls also set the college houses apart. McClelland Cafe, a popular dining facility known for its express sushi line and Asian cuisine offerings, is located in the uad. College first year Solinna nwochei, a resident of Ware College House, commented on McClelland as a central feature in the uad.

“We have a dining hall right in our front yard, nwochei said. Hill has their dining hall too, but McClelland is especially popular, because of the Asian cuisine and sushi is very popular around here. So I think the dining hall is in the center

of it all.

Lauder and ings Court College House also have dining halls, with Lauder offering special entrees at its dinner services. Though it is less popular with students due to its small size, uintanilla believes that the Lauder dining hall is “underrated, but good.”

Social Scene

With house events and open community spaces, Penn first-year dorms offer varying degrees of social living.

“Honestly, before moving here, I was a little terrified because of hearing how small the rooms at Hill were,” College and ngineering first year Anish

Dahl said. “But when I first got here, it wasn t that bad. veryone s super social, and super open to meeting people. I would say even if the rooms are small I think the community aspect of Hill makes it really special.

Dahl, who is a part of the agelos Integrated Program in nergy Research, lives a section of Hill with others in his program. Most coordinated dual degree programs at Penn have similar pre-assigned college houses.

“I think living together brings us closer together, and it s nice to come into college knowing a bunch of people and have a built-in friend group,” Dahl said. “I think it was a great move from the administration of IP R to facilitate that, and I m super grateful they did.”

College first year Alexis banks said she believes Lauder — which sits adjacent to Hill — seems to

lack the community aspects some of the other college houses have.

“There are events,” banks said. “But it s definitely not the most social place, which is kind of sad, but with Hill being nearby it makes it better . Still, you re in a room within a room, so it really prevents people from getting out.”

All interviewed first-year residents said that the uad dorms are the most social.

The uad features an open-concept design with a central courtyard, allowing for gatherings, events, and other activities.

“The uad has good social scenes in general,” College first year and Riepe College House resident Hans Manish said. “There s a lot of common areas to hang out in and very large study rooms, but also the actual uad itself and by McClelland, where there s chairs to hang out in the lawn.”

There are three four-year houses — regory College House, Du Bois College House, and Stouffer College House that host everyone from first-years to seniors, offering a different social scene from first-year only dorms.

With college houses located in different areas around campus, many students reported that they chose their residences based on the houses’ proximity to their classes.

Though uintanilla considered proximity to classes when deciding on Lauder, she ultimately felt ambivalent about the dorm s convenience.

“Since we are next to Hill, I feel like Lauder is pretty central to everything,”

uintanilla said. “Most of my classes are literally across the street, like in isher Bennett Hall or College Hall. But Lauder is

also far from the high rises, where most of my club meetings are So that’s a bit rough sometimes.”

Regarding the location of the uad, nwochei said that she does not think uad residents are “being done a disservice, even though we have communal bathrooms.”

She believes that Lauder and Hill are “really out of the way of academic spaces, and the uad, in turn, saves students from the long trek to a math class, Huntsman, or Commons like the college houses with suites and bigger rooms would have.”

Regardless of amenities, all first-years pay , for their college houses. Students interviewed by the DP said they believed the standardized price was fair, with each college house having its own benefits and trade-offs.

“I m paying the same

price for a much smaller room than someone in Lauder, but at the same time, I don t have to clean the bathroom and I get such a strong community,” Dahl said. “It s not just about space, it s about the whole experience holistically. Looking at that, I would say it s fine that all the houses are priced the same.”

Dahl praised further how income disparities are not re ected in students’ college house experiences, adding that “if you had different pricing for each college house, all the more a uent people or those that come from more a uent families will be grouped together.”

Arti ain and Alexa Smith contributed to reporting for this article.

Opening Fall 2026 at 3615-35 Chestnut Street, The Mark is proud to join the University City housing community, o ering a wide range of studio to sixbedroom apartments across 30 floor plans. Each unit comes fully furnished, with private bedrooms and bathrooms available for every unit type, providing residents with both comfort and convenience. Residents can enjoy luxury amenities, including a resort-style pool, hot tub, sauna, cold plunge, tanning beds, sports simulator, private study rooms, and a 24/7 fitness center. Outdoor spaces feature grilling stations, firepits, and a jumbotron for community gatherings and entertainment. At The Mark, we prioritize residents, hosting frequent events to foster an inclusive community. Discover a new standard of student living, where lifestyle, comfort, and community come together.

Now presenting The Clark - new, elevated residences with style and intrigue in University City. We’ve got it all (and you will, too) - Philadelphia’s rich history, a spirited community, bespoke amenities, and service that doesn’t skip a beat. Full of ambiance and intrigue, The Clark luxury apartments in Philadelphia is the perfect setting to call home.

he uad reno ation pro ect egan n and s currentl n ts th rd and nal phase w th reno ations to sher assen eld ollege ouse slated or completion n ugust .

JAMES WAN Contributing Reporter

With the last set of renovations underway, The Daily Pennsylvanian spoke to current first years and Penn Residential Services about ongoing improvements to the Quad.

The Quad renovation project began in 2023 and is currently in its third and final phase, with renovations to Fisher Hassenfeld College House slated for completion in August 2026. Construction of the Riepe and Ware College Houses were completed in August 2024 and August 2025, respectively.

The Quad renovations are focused on “improving building infrastructure,” Director for Design and Construction Scott Nobel told the DP. The renovations prioritize updates to the mechanical and electrical systems as well as roof and window replacements.

Namely, the Quad’s new amenities include improved bathrooms, common spaces, and furniture as well as the installation of elevators. Director of Residential Services Pat Killilee emphasized the importance of the student living experience in the renovation process, explaining that the updates to community spaces in the Quad have been designed to meet “today’s needs.”

The Quad is being renovated because the last renovations took place roughly 25 years ago, placing it in the cycle for improvements, Killilee explained. Another focus of the renovations is accessibility, hence the

addition of two elevators — one in Riepe and one in Ware.

“Because of the age of the building, it can never be 100% accessible, but it is significantly more accessible now than it was three years ago,” Killilee told the DP.

The DP spoke to first-year students who expressed general approval of the renovations. Wharton and ngineering first year Ava Martoma, who lives in Ware, expressed satisfaction with the upgraded bathrooms and common spaces in her college house.

“The common spaces are nice,” Martoma said. “I think the bathrooms are very nice compared to most dorm bathrooms that I’ve been in.”

Wharton first year Sean Liao, a Riepe resident, commented that the renovations are additional benefits on top of the Quad’s convenient location and social life. He emphasized his appreciation for the study lounges especially.

Last year, Quad residents told the DP that the renovations to Ware, which divided the upper and lower Quad, disrupted their social and residential experience. Current first years stated that the Fisher Hassenfeld renovations have been different, highlighting a lack of disruptions and construction noise.

Nobel told the DP that there are numerous measures being taken to avoid negatively impacting the current student experience

in the Quad, including separating the project into three phases, isolating construction areas, and considering students’ schedules.

“The contractors are working in accordance with the school schedule in ways where reading days and so forth are accounted for,” Nobel said. “There are also later starts to the construction piece to avoid early starts.”

Ware residents who spoke to the DP mentioned that the lack of a water filling station in their college house is “the main issue.”

“We are currently working on identifying a location for a water filling station in Ware,” Killilee told the DP.

He explained that it was missed during the construction phase, but that it will

be added sometime during the academic year. Riepe has a water filling station, and Fisher Hassenfeld will also have one once its construction has been completed.

Wharton and Engineering first year Anthony Yu, another Ware resident, also expressed concern about the air quality in the renovated Quad, adding that he has his “window open all the time.”

Still, the project places a focus on sustainability to ensure equipment is “commissioned to optimal levels.”

“The effect will be to improve the student experience by creating refreshed and functional, accessible spaces that minimize maintenance calls,” Nobel added.

cross ts ast scale o operations enn n ng and on pp tit the cater ng compan that partners w th enn are ta ng steps to adopt susta na le practices and em race en ronmentall r endl pol c es.

NORAH FINDLEY AND JACK GUERIN Staff Reporter and Senior Reporter

As Penn Dining initiates several interconnected sustainability initiatives following the 2024 release of the University’s Climate and Sustainability Action Plan 4.0, The Daily Pennsylvanian spoke with the division about how its team is working to meet its “nearzero waste” goals.

Every day, Penn Dining serves 12,000 to 15,000 meals across its residential dining, retail, and catering department, with operations ranging from food sourcing and preparation to waste management. Across

its vast scale of operations, Penn Dining, the University’s on-campus food service department, and Bon Appétit, the catering company that partners with Penn, are taking steps to adopt sustainable practices and embrace environmentally friendly policies.

How Penn Dining collects data and analyzes metrics

One goal laid out in CSAP 4.0 is to “[p]ilot zero-waste operations in at least one residential dining hall and begin a phased transition to require all providers to op-

erate zero-waste residential dining halls.”

In pursuit of this objective, Penn Dining is piloting a program at Quaker Kitchen this year that Bon Appétit Regional Sustainability Coordinator Elise Dudley characterized as striving for “near-zero waste." If the plan “goes well,” the division intends to expand the initiative to other residential dining facilities in the future, according to Penn Dining Associate Director of Operations Thomas MacDonald.

In a statement to the DP,

Business Services Director of Communications and External Relations Courtney Dombroski wrote that Penn is interested in expanding the effort to alk Dining Commons in Steinhardt Hall.

“Because alk operates under kashrut—Jewish dietary laws that guide how food is prepared and served—we may not be able to fully meet all of the zerowaste guidelines in that space,” Dombroski wrote. “That said, we are committed to working within those parameters to identify op-

portunities to reduce waste wherever possible.”

Dudley expressed optimism regarding the feasibility of all residential dining halls getting to a zero-waste status.

“I do believe it’s achievable,” Dudley said to the DP. “We’re already on track just because of the commitments that we have around waste management on campus.”

Penn Sustainability’s Student Eco-Reps — an environmentally focused leadership cohort of undergraduates — are working

with Bon Appétit to collect data on food waste at Quaker Kitchen and other dining halls, and to develop solutions to address zerowaste obstacles.

Dudley stated that the team will focus on “better understanding postconsumer food waste” by collecting data and then “implementing some interventions to try to reduce [it].” From there, Dudley said that the Eco-Reps will “do an inventory of all the other residential dining locations.”

Penn participates in the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment, and Rating System, an assessment run by the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education that tracks sustainability performances at colleges and universities. Penn has a rating of “gold” — the second-highest category — according to its STARS report.

The dining team also meets regularly with Penn Sustainability and campus stakeholders to discuss CSAP 4.0 implementation and goals. It also tracks and reports quarterly purchasing data to Penn Sustainability, which informs their “scope 3 emissions tracking and nitrogen footprint analysis,” according to Dudley.

Plans to leverage data into action

One project under consideration is a Green Fund at Houston Market, a customer-facing compost collection approach modeled after an existing scheme at Joe's Café. The initiative — a joint effort between the Undergraduate Assembly and Penn Sustainability — would be overseen by Bon Appétit Director of Retail Dining Daniel Wideman. The Environmental Sustainability Advisory Committee — a group of faculty, staff, and students that

advises the President — also has a single-use plastics subcommittee that is working with different vendors to move away from plastic towards aluminum bottles.

“The transition is underway,” MacDonald told the DP. “It’s a little hard to get aluminum water bottles at this point in this market. But we can recycle aluminum … much better than plastic, and that’s a goal that we’re working towards.”

Bon Appétit's Director of Operations Steven Green also discussed Penn Dining’s Green2Go, a reusable to-go box program available to students. Last September, Green2Go partnered with the app Reuzzi to increase their container return rate, which has since climbed to 97%.

“In the past, we faced challenges with the Green2Go program and receiving back the containers. At times, we ran out

of containers and had to switch to using single-use fiber containers,” reen said. “[Since] we instituted the app Reuzzi, we have found a vast reduction of challenges with running out of Green2Go containers.”

In the past year, nearly 13,000 Green2Go container transactions were recorded, with a monthly average of 500 students utilizing the program. The program has prevented 6,588 pounds of carbon dioxide emissions, according to a statement from Dombroski.

Penn Sustainability intern and graduate student in environmental studies Jason Klein, who recently led a New Student Orientation program surrounding waste and recycling, said he thought the Green2Go program was still “something that could be improved.”

“Some of the students [in the Student Advisory Group for the Environment], when we were talking

about Green2Go, [said] they thought it didn’t exist anymore,” Klein said to the DP. “I think that it needs to be marketed more.”

In the future, Penn Dining aims to lower its climate impact on the operations side through efforts such as setting purchasing guidelines for dining equipment and incorporating innovative disposal systems. The decision will follow these climate-friendly strategies in the upcoming 1920 Commons Renovation project. How food arrives at Penn

A key component of Penn Dining’s waste-reduction efforts is sustainable sourcing, which helps reduce climate impact before food reaches the kitchen.

One key factor driving decisions on what ingredients to purchase is what is on the menu in a given week, which is driven both by student and guest input and Penn Dining’s

“plant-forward menuing” philosophy.

“We have surveys. A lot of that survey information is used to write the menus, and then we are sourcing things under strict guidelines that Bon Appétit has created for their food standards,” Green said to the DP.

He added that “many” of these ingredients come from local farms and purveyors, which must meet certain established thresholds of local vendor sourcing.

The Penn Dining team has also set “purchasing commitments” that include considerations of humane certifications and fair trade practices.

“Our kitchen philosophy [is] serving food that’s prepared from scratch … alive with avor and nutrition, which we achieve through buying the freshest local ingredients,” Dudley said. “It’s always our first choice

to then source in a socially responsible manner.”

Penn Dining’s culinary team practices “plant-forward cooking,” which emphasizes plant-based foods, according to Dombroski. She emphasized that Penn Dining offers plant-based options at every facility, resulting in more than 59% of food purchases in 2025, by weight, being plant-based products.

Underlying the two new campus pilot projects is a comprehensive waste-management system designed with sustainability in mind.

According to Waste Not, Bon Appétit’s internal waste-tracking platform, 92% of food waste was sent to be composted at a local facility operated by Bennett Compost in Northeast Philadelphia, with 7% sent to a landfill and to food recovery. During the 2024-25 academic year, the

division stated that it had diverted an average of . tons of waste per month away from landfill and towards composting.

“We have a provider on campus that provides us with compost totes,” Green said. “We fill those totes with compostable food scraps and waste, and they pick up those totes regularly.”

Penn’s hierarchy of preferred waste-management methods mirrors the Environmental Protection Agency’s Wasted Food Scale, with landfill as the “last preference.”

Penn’s kitchens also employ a preventative “batch cooking” method to prevent waste creation. Any leftover food at the end of a day is sealed, labeled, and frozen, according to Green. Bon Appétit then connects with a food donation source to donate the extra products at the end of each semester.

Housing Fair and enter

It's the perfect way to upgrade your sleep sanctuary this fall.

Friday, October 3 11a.m.-2p.m. | Annenberg Plaza

Stay fueled and connected with a Penn Dining plan:

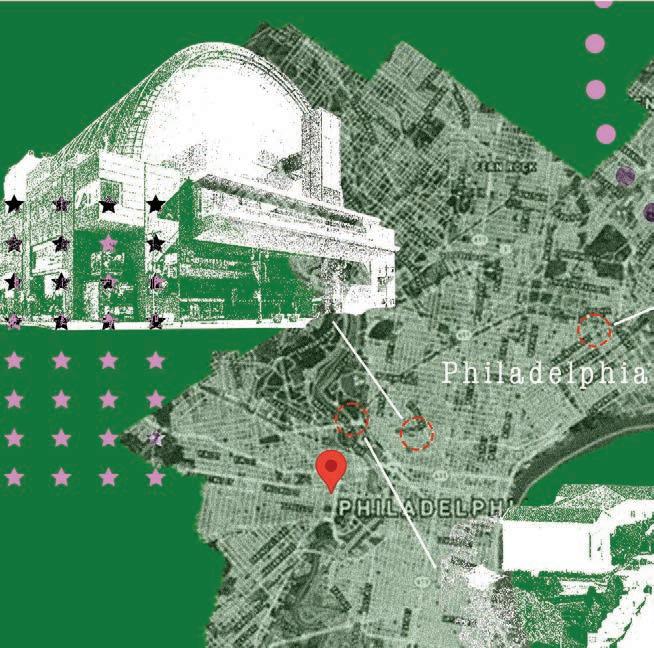

The Daily Pennsylvanian analyzed the property values of Penn's real estate holdings in University City using the City of Philadelphia's 2019 property records website.

The Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania own over $3.3 billion worth of real estate in University City — three times as much as any other educational institution in the area — according to an analysis of city property records by The Daily Pennsylvanian.

Penn’s real estate holdings in Philadelphia include the buildings on campus, University of Pennsylvania Health System facilities, several properties around the city, and many offcampus houses traditionally leased by students. Using the City of Philadelphia’s property records website, the DP analyzed over 1,600 properties located within the boundaries of 29th and 42nd streets and between Powelton and Grays Ferry avenues — the area depicted in Penn’s online Large Campus Map.

According to the Consolidated Statements of Financial Position detailed in Penn’s fiscal year financial report, the net book value of Penn’s facilities — excluding properties within the Health System — is closer to $3.9 billion. In an interview with the DP, Penn Executive Vice President Craig Carnaroli said that the discrepancy between Penn’s records and the city’s can be attributed to a delay in the city updating its records — illustrated by the fact that Gutmann College House, which opened in the fall of 2021, does not appear on the city’s website.

On the city’s website, the

Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania are listed as the owner on the deed of around 185 properties on Penn’s campus map, making Penn the largest real estate holder in the University City area. By comparison, Drexel University is listed as the owner of just 12 properties worth just under $1 billion total, and the University of the Sciences — now owned and recently put up for sale by Saint Joseph’s University — also owns 12 properties worth close to $200 million. The University City Science Center, which was established in with significant help from the West Philadelphia Corporation — of which Penn is a member — owns six properties.

Of the 20 properties with the highest estimated value within Penn’s campus map — which include several Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia facilities, Domus Apartments, Brandywine Realty Trust’s Philadelphia campus, and the area containing the Palestra and Franklin Field — the University Trustees own 11. Of the remaining nine, Penn has been involved in developing or overseeing four of the institutions — three being CHOP facilities and one being the Domus apartment building.

Carnaroli told the DP that Penn’s development strategy has evolved over the years from “Penn as a developer” to “Penn as landowners.” The difference, he said, lies in the

EMILY SCOLNICK Editor-in-Chief

University’s change in approach from using its capital to construct buildings on the land to renting the land to a third-party owner and having them invest in development.

“Penn’s real estate strategy is to attract outside investment from the private development market. Penn leased the land to The Hanover Company, a Houstonbased developer, for 65 years,” a Facilities and Real Estate Services webpage describing Penn’s involvement with Domus reads.

According to Carnaroli, Penn’s first major independent developments included The Inn at Penn and the Penn Bookstore, as well as developing the intersection at 40th and Walnut streets that now houses Acme Markets, Cinemark University City, and Panera Bread.

Although Penn does not

own CHOP, the hospital is part of the Health System and closely a liated with Penn Medicine. CHOP’s real estate holdings encompass six individual properties totaling just over $600 million. ther sites a liated with Penn Med include Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, which is centralized in several different buildings worth a total of $67.4 million; Pennsylvania Hospital, worth $32.4 million; and the Philadelphia eterans Affairs Medical Center and Nursing Home, properties that together are worth $31.2 million.

While the VA Hospital is not part of Penn Med, the institution has a formal partnership with the Health System.

The nearby Penn Med facilities owned by the University Trustees — which include the main

Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, HUP offices, the Perelman Center of Advanced Medicine, and two o ce buildings on Civic Center Boulevard — are worth about $460.3 million. Additional properties located off campus — one in Rittenhouse Square and another suite at 8th and Walnut streets — are worth nearly $27.6 million, bringing the total value of local Penn Medicine real estate to nearly $488 million.

The highest-valued property within Penn’s campus map is Brandywine Realty Trust’s Philadelphia campus, which is worth $370,556,400, according to the city’s property records website.

Penn’s off-campus property holdings include some niversity-a liated facilities or Universitysponsored housing. For

example, the building occupied by Penn’s reenfield Intercultural Center is owned by the University and located just off campus.

Penn also owns several buildings along Walnut and Spruce streets that house several of Penn’s greek life organizations. However, approximately 65% of the University Trustees’ individual properties are off campus and una liated with niversity facilities.

Penn’s off-campus presence in University City has often garnered attention and criticism, including its participation in efforts to develop the area formerly known as Philadelphia’s Black Bottom. As the niversity and its facilities — both medical and academic — continue to expand, the effects of this development have changed the architectural landscape of the area and affected how the area is viewed.

“The university has not al-

ways been a good neighbor or player [in West Philadelphia], especially for the surrounding lower income communities that have been continually displaced over the decades,” City and Regional Planning professor Jamaal Green wrote in a statement to the DP. “We are [a] major anchor institution but still act as if we are not a fundamental force in the development of this area of the city.”

1968 Wharton graduate and President Donald Trump’s administration’s recent “assault on higher education” could also impact Penn's approach to real estate, according to Carnaroli. He said the University’s evaluation of development opportunities may change to prioritize “replacements” for buildings requiring reinvestment of resources as opposed to growing campus itself.

“ on-profit educational institutions like Penn are

both asset and people intensive,” Carnaroli wrote in a follow-up email. “To carry out our mission, we require facilities to carry out our broad education, research and service missions, in addition to the people who perform those services.”

The University Trustees also own properties located further off campus, but their mailing addresses are listed those of Campus Apartments and niversity City Associates — two offcampus housing companies that Penn has had longstanding relationships with. Campus Apartments was founded in 1958 by Alan Horwitz to help create a higher standard of off-campus living for Penn students. Horwitz still serves as chair of Campus Apartments, and company C David Adelman sits on the Penn Medicine Board of Trustees.

The company launched a partnership with Penn in

2003 and has worked with the University on several campus projects since then; it also owns many properties around Penn’s campus.

CA, which is managed by Campus Apartments but completely owned by Penn, also owns many off-campus properties.

Campus Apartments and CA also manage Penn’s greek housing — including key pickup and maintenance requests — even while many of the chapter houses are owned by the niversity.

“We recognize that we don’t provide housing for all undergraduates, so we want them to have … safe options off campus,” Carnaroli said.

Another prominent local real estate agency, University City Housing, is owned and operated by 1964 College graduate and former University Commonwealth Trustee Michael arp. According to the DP’s recent

analysis, arp or CH are explicitly listed as the owners of just over $41 million worth of real estate near campus on Philadelphia’s property records website — but lease out many others that they do not explicitly own.

Studio - 5 Bedroom Apartments & Houses

Steps from Campus

Upgraded Apartments Available

Pet Friendly Options

On-Site Laundry

24/7 Package Pickup with Amazon Hub

10:00 AM - 11:00 PM 10:00 AM - 1:00 AM 3816 CHESTNUT ST (215) 925-2229 Sunday - Thursday Friday - Saturday

“The pizza was soooooo good! Omg it was so fresh and delicious! The 5 star rating is completely warranted here. The staff is also really fun!”

he n ers t n tiati e wh ch s run out o enn ra s the appl ed research arm o the e t man chool o es gn stud es hous ng cond tions n h ladelph a to ad se pol c ma ers.

ALEX DASH Senior Reporter

The Housing Initiative at Penn is working to confront Philadelphia’s affordable housing crisis, including responding to the recent proposal to sell properties that contain over 900 affordable rental homes in the city’s West and Southwest neighborhoods.

The University initiative, which is run out of PennPraxis — the applied research arm of the Stuart Weitzman School of Design — conducts empirical research on housing conditions in Philadelphia

to advise policymakers.

Last month, the private developer eighborhood Restorations announced its intention to sell its portfolio of federally subsidized affordable rentals in West and Southwest Philadelphia, marking the latest challenge for HIP.

The properties, which were built in the late s and early 2000s with federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, have 30-year affordability restrictions that have already begun expiring and will continue

to do so until . nce the restrictions expire, eighborhood Restorations can keep the houses affordable or sell them to a new owner. If the new owner chooses to move them up to the market rate, the tenants of the properties — who number over , — could be priced out, according to HIP founder and faculty director incent Reina.

“What we’re seeing in Philadelphia, much like the rest of the country, is essentially this scenario where in any given year, there are

hundreds and sometimes thousands of units where the affordability restrictions on these properties are set to expire,” Reina said in an interview with The Daily Pennsylvanian. “That doesn’t necessarily mean all the rents will go up, but it means they absolutely can.”

A re uest for comment was left with eighborhood Restorations.

The expiring affordability restrictions constitute a “knowable problem,” Reina said. City o cials know when the restrictions on

properties are set to expire, allowing them the opportunity to “proactively assess” which properties will expire and plan in advance to combat the effects of those expirations.

According to Reina, the impending expirations provide an opportunity for the city to maintain affordable prices and even improve housing quality through recapitalization.

“These properties often need some form of recapitalization, because they’re so old,” he said, adding

Sponsored by:

that expiring affordability restrictions allow the city government to “apply public resources and public will to ensure that many of those properties, if not all, are not only maintained as affordable, but also recapitalized so they’re highuality places to live.”

Reina has been working with city governments to inform housing policy since , when he helped to create Philadelphia’s first citywide housing plan.

“We realized there was a real kind of opportunity and need to partner with municipalities to help them both develop housing solutions, but also evaluate their impacts,” Reina said.

That work, he noted, emphasized the “need to

partner with municipalities” to “develop housing solutions” and “evaluate their impacts.” That realization eventually led to HIP’s creation.

During the C IDpandemic, HIP established itself as one of the leading authorities on emergency rental assistance research.

In May , HIP assisted city o cials from Philadelphia, Atlanta, Cleveland, Baltimore, akland, and Los Angeles with the implementation of emergency federal rental assistance programs developed during the pandemic.

In anuary , the initiative received a , grant from the nited States Department of Housing and rban

Development to study the effectiveness of the rental assistance program. The project studies the impact of the program on eviction rates during the pandemic and the factors that affected the program’s in uence on housing stability.

According to Reina, HIP now hopes to confront the problem posed by expiring federal affordability restrictions.

“Many other cities have gone through this effort, and there have been a lot of local efforts within Philadelphia,” Reina said. “There’s a real distinct opportunity to be consistently ahead of this conversation to leverage existing city resources to address that problem.”

Shop Penn o ers a variety of finds to help you reimagine your space—whether you’re organizing, adding a personal touch, or simply browsing for inspiration. Take a walk through University City and discover pieces that make your home feel uniquely yours.

Shop Local.

Penn.

total o households were randoml selected to partic pate n the program rom the h ladelph a ous ng uthor t wa tl sts.

The PHLHousing+ pilot program — a rental assistance project spearheaded by the Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation and the City of Philadelphia in collaboration with Penn — announced their findings last week.

Initially established in 2022 to help address housing insecurity in Philadelphia, the program provided rental assistance to participants in the form of monthly cash payments via a program-specific debit card. A total of households were randomly selected to participate in PHLHousing+ from the Philadelphia Housing Authority waitlists.

The pilot revealed a potential new method of housing assistance in addition to evaluating the effectiveness of existing housing assistance, like housing vouchers. “Philadelphia really needs multiple housing strategies because no single approach will work for everyone,” PHA President and CEO Kelvin Jeremiah said in a press release documenting the program’s initial outcomes.

Newly released research — authored by researchers from the Housing Initiative at Penn, the Risk and Resilience Lab, and PHDC — reported that the program “has had significant positive impacts on the housing security of participating families” that are “comparable to those reported by households that receive rental assistance”

ASHLEY WANG Staff Reporter

through the Housing Choice oucher program.

The brief detailed that cash rental subsidies “significantly reduced the chances of a household experiencing homelessness,” “improved the reported housing quality of households,” and decreased forced moves by“relative to households that received no assistance” after one year, among other benefits.

Though direct cash fares have promising positive outcomes, the research brief still a rms that both cash payments and vouchers are necessary to maintain robust, effective housing assistance.

“Both forms of rental

assistance are crucial for ensuring low-income families have safe, stable, and affordable housing,” the brief reported.

Penn researchers are continuing to help analyze the program’s results, evaluating both direct cash payments’ effectiveness in comparison with other housing assistance as well as their impacts on individual outcomes.

Professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning and Faculty Director of HIP Vincent Reina said that the findings tell a clear story.

“There are clearly positive benefits of this cash transfer program,” Reina told The Daily Pennsylvanian. “ olks

are clearly seeing higher levels of housing stability and improvements in housing uality.”

He added that the findings highlight the “reality that there’s a real opportunity — one for us to think creatively about how we apply rental assistance, but also to acknowledge that we need this broader tool set out there … to help households.”

In addition to promoting housing security, Department of Psychology chair and Psychology professor Sara affee explained how the cash subsidies can potentially impact several other individual opportunities.

“We’re also very inter-

ested in a related set of outcomes,” affee told the DP. “Does it enable our households to move to higher opportunity neighborhoods? We’re going to pivot in that direction, to start looking at the kinds of educational opportunities, employment opportunities, the kinds of health opportunities that exist in neighborhoods.”

affee added in the initial PHDA press release that the “lessons learned from this program will offer invaluable insight about the impact of housing assistance on a broad set of adult and child outcomes and about the difference exible assistance makes in people’s ability to access and maintain housing.”

en or olumn st r ti a enth l rea s down how enn s h gh r se res dences shoehorn stu dents nto o erpr ced d s unctional hous ng.

Over the nearly six decades that Penn has opened West Campus to student housing, the University’s infamous trifecta of highrise buildings — Harnwell, Harrison, and Rodin College Houses — has managed to consistently fall short of many already-low expectations.

Perhaps the most obscene case yet was on display just a few weeks back. The closest elevator to my dorm, situated at the center of a hall that residents pass through on their way in and out of the oor, had a strapless bra plastered onto its doors.

Who had the audacity to pull this off, to air their personal drama — and lingerie — to the masses?

That too, near the busy, camera-laden entrance of the hallway.

I was, unfortunately, not surprised. Penn isn’t a stranger to such stunts, especially during pledging season. More importantly, though, the attempted tour de force was just another notch on a list of grievances of temperature control problems, mold colonies, and faulty facilities in Penn's high rises.

My first visit to a high rise residence was last year,

during a premiere screening of an indie horror film hosted by the Wharton Undergraduate Media Company. The film was average — I could see why major studios didn’t pick it up. But the venue, Harrison’s Sky Lounge on the th oor, was the saving grace of the evening. Floor-to-ceiling windows offered panoramic views of Philadelphia. The illuminated LED logos of the Penn Medicine Pavilion shone against the skyline were a stark contrast to the former cotton plantation I’d overlooked at my boarding school in South Carolina. At the time, I was

optimistic about my future in the high-rises, and I only wish I could hold on to that optimism now as a high rise resident.

Within only two months of this academic year, Penn authorized up to $13.8 million for upgrades to elevators in Harrison and Harnwell College Houses, expected to be completed within the next two years. These plans, although promising, are set to take place following the graduations of the Class of 2026 and 2027 — but what do we make of the caution tape sealing off the elevators today? Meanwhile, in just

the last semester, I received 12 emails concerning elevator outages, all of which concluded with: “We will pass more information on repairs when it is available … Residents may wish to leave additional time to get to appointments or class or consider using the stairs if possible.”

These stairs are winding ights that span oors. Especially during rush hours, their concrete steps are a slip hazard. Safety shouldn’t hinge on our level of patience; and, patience runs thin when you’re waiting ten minutes for an elevator. Even then, waiting

is a gamble: you might step into the elevator and find the remains of someone’s morning coffee on the oor.

I'm sure at least some of you will ask why I don't just leave my dorm. If I even vaguely considered studying abroad this year — Greece, the United Kingdom, Singapore, really anywhere, even if unrelated to my degree — it was to avoid mandatory campus housing. Beginning with the Class of 2024, all sophomores were required to live on campus. Additionally, those transferring to Penn must also live on campus for up to four semesters. As for where we live, students are assigned a randomized selection timeslot for the room selection period. During their time slot, students log into the housing portal to view available rooms and select their desired option in real time. To put it simply, these time slots determine the

order in which students can choose their rooms. arlier slots provide better access to preferred housing options, including singles and specific apartments. I was among the less fortunate assignees, those with later times who are stuck overpaying for whatever’s left.

Typically, the standard rate of $12,640 for the 2024-2025 academic year applies to all first-year student rooms and most upperclass rooms in specific College Houses. However, for the premium rate of $16,580, students are offered apartments with a living room and kitchen in high rise buildings. nable to secure a standard-rate room, I was forced into a higher-rate apartment with a kitchen I have yet to use — and roaches as a bonus.

Considering Penn's requirement for students to also remain on a dining plan during their first two years,

the University has a captive market for its subpar services.

However, we’re not paying premium rates to just work around broken systems. We’re essentially required to engage with a system that seems to ignore our needs. And faulty infrastructure isn’t a privilege issue — it’s a safety one. Our residences aren’t short of maintenance staff and funding, but clearly, there’s a gap between effort and outcome. or now, Penn’s housing options don’t re ect the caliber of the institution they represent.

MRITIKA SENTHIL is a sophomore from Columbia, S.C. Her email is mritikas@upenn.edu.

Columnist Kanishka Agarwal argues that assigned rather than chosen roommates can allow for more authentic connections and personal growth.

A uintessential pre-firstyear experience is looking for a roommate online before school starts. Stalking Instagrams, scrolling through pictures, and sending that all-important first message. Conversations feel like dating bios with lines like: “Looking for someone who laughs at my terrible jokes, won’t judge my midnight ramen obsession, and loves going out … and staying in!”

But beneath the Instagram DMs and curated bios, which honestly feels like a weird pseudo-dating ritual, is something bigger: the first time since getting

in that you’re really being perceived by your new college community. It’s also one of the first moments that students start to adjust themselves based on what they find the Penn community expects. Here’s how it goes: You follow each other back on Instagram (it’s a match!), you slide into their DMs (anyone know any roommate pickup lines?), you have your first conversation filled with nervous small talk and subtle tests to establish trustworthiness. Maybe you part ways politely. Maybe you get ghosted. Maybe, if you’re lucky, you

FaceTime!

Of course, much like dating, everyone’s trying to seem cooler and way more put together than they really are. Because just like dating, we’re making ourselves vulnerable to rejection by people we think are good for us. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to put your best foot forward, especially when you’re swiping for a potential roommate as if Instagram is a dating app. Letting that instinct make its way into every interaction is when it becomes inauthentic. When I was finding a roommate, I caught myself

starting to perform a version of myself I thought college demanded. I introduced my interests by talking about popular music artists I liked because I thought mentioning my “Hamilton” obsession outfront would make me cringey. What starts as trying to find someone to live with becomes the introduction of a polished image meant to win approval, not just from a potential roommate, but from a whole new realm of people.

It’s a form of social risk management, a natural response to new surroundings driven by human

emotion. Simply put, we do not want to be isolated from our community for the next four years. We often think inability to resist peer pressure is a personal failure, but what if a structure around them perpetuates that stress? Finding a roommate is just the first step. An obvious answer may be to stop caring about what others think altogether. But honestly, that’s kind of unrealistic. A school like Penn creates huge expectations for unrivaled access to opportunities, and networking is a big part of taking advantage of those. The truth is, by letting

first years pick their own roommates, Penn begins to corporatize relationships before students even step foot on Locust Walk. We start to treat conversations like a sales pitch — only, we’re the product. Rather than trying to convince students to get rid of the normal urge to fit in, it’s time to call for institutional change instead.

While Penn does give students the option to go random, the issue lies in the fact that it also gives students the opportunity to pick their own roommates. This choice reinforces the idea of social bubbles, which create pressure to act a certain way in the first place. So while Penn’s options might be comfortable for some students, they can make the situation worse for others.

Many top schools choose all students’ first-year roommates for them, including Harvard, Yale, Stanford, and Dartmouth. If picking your own roommate is like using a dating app, then letting your university decide your roommate is like being set up by a mutual friend.

A third party sees the traits you have in common and matches you accordingly based on compatibility, such as sleeping habits and cleanliness, instead of optics. This makes us stop worrying about finding a roommate who is exactly like us, or exactly like who we want to be, and open our minds to new possibilities while (probably) minimizing the discomfort of rooming with someone with whom you have incompatible living habits.

What’s more, a thirdparty roommate match is likely to increase diversity. When you pick your own roommate, it’s tempting to minimize that social risk by trying to choose someone with similar traits to you, maybe the same hometown or intended major. It just feels a lot safer. But when schools assign roommates, it removes that pressure and broadens student perspectives. A study done across Duke, Stanford, and Tufts even showed a significant increase in cross-race friendships and more positive interactions across people from different backgrounds when universities randomly assign all incoming first years a roommate. Choosing your own roommate might feel like you get to swipe left or right on endless options to find “the

one,” but it can actually function more as a loop of endless talking stages. Suddenly, your terrible jokes and midnight ramen obsession become things you carefully hide, because you’re terrified of being ghosted. It forces incoming students to turn their genuine need for connection into a marketing pitch. This pressure to get it right reduces the chance of making unexpected, meaningful friendships. If Penn removes the option to choose your own roommate, it would take away the idea that people need to impress their way into belonging on campus. It gives students the chance to show up as who they truly are and meet people they might not have initially thought that they would get along with. Because let’s be honest,

there are far more productive things to prepare for in college than pretending you’re someone you’re not. Most first years are still googling “How to do laundry?” and hoping no one notices. It’s time for Penn to make sure students can focus on the right kind of growth.

KANISHKA AGARWAL is a College rst year from Cypress, Texas. Her email is agarwa1k@ sas.upenn.edu.

olumn st a d ran argues that enn s res dential college s stem a ls to del er the commu n t t prom ses and how t can e redes gned.

As I settled into my college house back in August, I was ecstatic to make new friends as a freshman. I heard Penn had a College House system, much like that of Hogwarts from “Harry Potter,” that I was looking forward to. However, after a few, low-attended events, that idealism was quickly and woefully extinguished.

Alan Kors, the professor of history who helped establish the first college house at Penn, warned in a Pennsylvania Gazette article from 1999 that Penn’s residential college system only existed in “name” rather than in

“spirit.” Kors’s warnings were never heeded, but he was indeed right: the residential college experience at Penn is deeply awed. The quintessential “Penn Freshman Experience” remains unchanged from the era before residential colleges. Incoming freshmen vie for the Quad for its social scene, only to end up desiring to leave it behind. And now that I’ve experienced it myself, I can say that the feelings are not unfounded. While the Quad is known for its “social life,” college house events usually go unattended. There isn’t much that brings people

together beyond pregames and the weekend frat parties.

Simply put, Penn’s residential colleges are only a place to stay, not to live. With college houses failing to build the sense of community that many desire, students turn to Greek life. An estimated 25% of Penn students are involved in Greek life, far greater than the 10 to 15% national average. I’m not saying Penn should abolish Greek life, I’m saying Penn should provide an alternative sense of community that meets the same needs currently fulfilled by reek

life to everyone. Despite efforts by the University to foster community through the college house system — including a faculty-in-residence model, heraldry and mottos to create a sense of tradition, and house-specific events — the experience just isn’t as intimate as it should be. So, what should we aspire to? Look no further than the golden children of residential colleges: Yale University, Rice University, and Northwestern University — whose experiences we’ve only half emulated. Yale’s first-years are randomly selected into one of four-

teen residential colleges. First-years mostly reside on Old Campus, Yale’s version of the freshman Quad, in sections designated to their respective colleges before moving into their college houses sophomore year. Rice’s residential colleges each have a form of elected student government overseen by a faculty “magister” that plans out a college’s social events. Many of Northwestern’s students live in residential colleges that host formals, philanthropy events, and inter-college competitive events. How do they make it work?

A study on residential

halls found that by fostering interaction, identity, and solidarity — the three pillars of community — students will become more socially integrated and committed to their institution. If Penn wants to create a truly functioning residential college system that benefits their students, it must rethink the entire College House system to take into account these factors.

First, the Penn Residential Services must consider the possibility of limiting first-year residents to firstyear dormitories and randomizing the college house selection process. Rather than selecting dorms based on social status or convenience, students would be forced to interact with their communities. This means applying with a roommate will not be allowed for firstyear students; however,

second-year students will have the option to do so and may also transfer to another college house. While some argue that students should continue to be free to choose their dorm and who they stay with, research on Duke University’s random roommate policy suggests that students who are randomly assigned a roommate are more likely to form unexpected friendships and build more diverse social networks through cross-racial interactions. Furthermore, students with cross-race roommates exhibited more positive behaviors in subsequent interracial interactions, suggesting lasting benefits beyond the dorm room. That means a random roommate policy might have the added benefit of breaking down the self-segregating social

norms that have been entrenched in Penn’s campus culture.

Second, first-year-only college houses should be completely abolished in favor of selecting students into four-year college houses. First-year dormitories that currently make up Fisher-Hassenfeld, Riepe, Ware, or the Hill College House would instead consist of sections belonging to four-year college houses. For example, students belonging to Harnwell College House might live in Warwick, Ward, McIlhenny, Cleemann, Ashhurst, and Magee; and students belonging to Gutmann College House might live in N.Y. Alumni, Carruth, Lippincott, and Provost Smith. After freshman year, students will move into their designated college house, and after sophomore year,

they could choose whether to remain in on-campus housing with their college house community or move off-campus while maintaining their house a liation. This would ensure that students develop an early connection to their assigned college house, creating a sense of identity.

Third, each college house should have its own student government like Rice, overseen by the faculty directorin-residence, coordinating its social events and philanthropic initiatives. Each college house would engage in a monthly inter-college competition (yes, like “Harry Potter”), promoting a sense of solidarity among students as they represent their house in everything from trivia nights to athletic challenges and creative competitions.

Penn’s residential colleges

are awed, but by taking these steps to emphasize interaction, identity, and solidarity, college houses can be made a place to live, not just to stay.

DAVID TRAN is a rst year studying urban studies from Fort Worth, Texas. His email is ddtran@sas.upenn.edu.

While it may feel easiest to stay close to campus, there are plenty of ways to explore Philadelphia while giving back to the community.

By going to school in Philadelphia, Penn students can access a culturally rich, vibrant city with so much to explore beyond campus.

While it may feel easiest to stay within the “Penn bubble” close to campus, there are plenty of ways to burst it — exploring Philadelphia while giving back, too.

Getting around Penn operates its own bus services that run Mondays through Fridays from 4 p.m. to 12 a.m. daily. Evening shuttles are available seven days a week within campus boundaries and, during limited hours, into Center City. These services are free with a PennCard, as are Drexel University buses.

Students can utilize SEPTA buses or trains — which include trolleys into Center City and buses that connect campus to different neighborhoods — to venture farther outside the blocks that comprise Penn’s campus and into the city. SEPTA services are due to be reduced significantly this month because of budget cuts. For Penn, this will mean reduced bus offerings and no trolley service after 9 p.m.

Students can also take Amtrak — which offers a 15% discount for college students — from the nearby William H. Gray III 30th Street Station to access other cities on the East Coast.

Exploring Philadelphia

The Schuylkill River Trail

WILLIAM GRANTLAND Senior Reporter

— a riverside path with views of the city that is popular for runners, walkers, and bikers alike — is a short walk from Penn’s campus. Wissahickon Valley Park and Fairmount Park also offer expansive access to nature.

A walk along the Schuylkill River leads to Philadelphia Museum of Art, which houses one of the nation’s most expansive fine art collections and offers “Pay What You Wish” admission on the first Sunday of each month.

Other notable museums nearby include the Rodin Museum, the Barnes Foundation, and the science-

focused Franklin Institute. Philadelphia’s cultural offerings also include orchestra concerts at the Kimmel Center and Broadway musicals at the Academy of Music, which recently hosted “Hamilton” and will soon feature “Kimberly Akimbo.”

The Philadelphia Chinese Lantern Festival is held in Old City every evening through the end of August. Philadelphia’s annual Christmas Village will begin in front of City Hall after Thanksgiving.

On Saturday mornings from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m., vendors from across the region ock to the Rittenhouse

Square Farmers’ Market, selling produce, bread, plants, and more. For a shorter walk, the Clark Park Farmers’ Market also takes place on Saturday mornings.

Engaging with the surrounding community Penn also offers numerous opportunities to engage with the neighboring community. These include Academically Based Community Service courses — known by their acronym, ABCS — which allow Penn students to connect with West Philadelphia students while earning academic credit.

These courses are offered

by the Netter Center for Community Partnerships, a hub for Penn’s community engagement, which also offers other volunteer opportunities that include math and writing tutoring, sports, food security, and mental health support.

Opportunities for community involvement are also available through Penn’s Civic House, where students can work alongside Philadelphia-area nonprofits, join trips focused on social justice issues, or tutor West Philadelphia students in various academic subjects.