MINGEI MODERN

Dai Ichi Arts, Ltd is a fine art gallery exclusively dedicated to celebrating modern and contemporary works of ceramic art from Japan

Since our inception in 1989, we have focused on placing important Japanese ceramics at the center of New York's contemporary art scene The gallery has introduced pieces to the permanent collections of several major museums, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Art Institute of Chicago, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the Princeton University Art Museum, and many more

We are committed to providing authoritative expertise to collectors, liaising with artists, and showcasing inspiring exhibitions and artworks We welcome you to contact us for more information

Mingei Modern: Japanese ceramics, aesthetic, and practice

Exhibition catalog

On view: March 13 - 21, 2025

18 East 64th Street, Ste 1F New York, NY, 10065, USA www daiichiarts com

DIRECTOR’S NOTE

This year marks a century since the term Mingei was first introduced into Japanese aesthetics, a milestone that invites us to reflect on its profound impact As the essays in this catalog remind us, Mingei emerged from a shared admiration for “ordinary objects” and their inherent beauty, yet its meaning and application were understood differently by its key figures Over the past century, the movement has transformed Japanese ceramics and art, elevating them to new heights The ceramics exhibitions in our gallery have borne witness to this movement and its influence beyond Japan

I extend my heartfelt thanks to Dr Chiaki Ajioka and Hollis Goodall, who have provided a detailed historical introduction, setting the record straight on the complexities of Mingei As they note, discussions on Mingei often focus on Yanagi Sōetsu’s philosophical framework, but “this historical narrative has long shaped discussions of Mingei, yet it falls short of addressing the broad concepts and contradictions the term encompasses ” Their essays highlight how figures like Hamada Shōji and Kawai Kanjirō approached Mingei through their craft, with Hamada describing it as a pursuit of “healthy, natural, and beautiful” objects, while Kawai questioned the very boundaries of Mingei, ultimately forging his own artistic path The renowned Tomimoto Kenkichi, known internationally for his beautifully Kyushu-inspired objects, was also a great teacher, influencing many who followed in his footsteps

Our gallery takes pride in collaborating with scholars to bring deeper scholarship to the ceramic art scene As the essays demonstrate, Mingei was not a static movement but an evolving aesthetic that challenged ideas of authorship, technique, and modernity The discussion of Bernard Leach and Tomimoto Kenkichi reminds us that Mingei was also shaped by international exchange, where Japanese traditions and Western Arts and Crafts ideals converged

I also want to extend my gratitude to our gallery staff Kristie Lui, Haruka Miyazaki, and Yoriko Kuzumi for their dedication and creativity in putting this catalog together Their efforts have beautifully showcased works from artists like Hamada, Leach, Tomimoto, Kawai, and many more

We hope this catalog will illuminate and inspire the ceramic community, offering new perspectives on a movement that continues to shape the world of craft

Beatrice Lei Chang

MINGEI LINKS AESTHETIC & PRACTICE

BY CHIAKI AJIOKA

JAPANESE ART CONSULTANT

REVISITING THE MEANING OF MINGEI

In English, when referring to objects, Mingei is commonly translated as "folk art" or "folk craft " However, as an aesthetic or creative approach, Mingei embodies qualities and ideals similar to those of the Arts and Crafts movement, which drew inspiration from the thoughts and practices of William Morris Discussions of Mingei both in Japan and, to some extent, internationally typically begin with its origins in late 1925, when the term was coined by three Japanese figures: the religious philosopher Yanagi Sōetsu (also known as Yanagi Muneyoshi, 1889–1961) and the potters Hamada Shōji (1894–1978) and Kawai Kanjirō (1890–1966) United by their admiration for “ordinary objects,” they described such items as minshū teki kōgei, or “crafts typical of the people,” which they shortened to Mingei Among the three, it was Yanagi who actively championed the concept Through his extensive collection of objects, writings, and lectures, he shaped the now widely accepted definition of Mingei According to Yanagi’s 1927 work, Kōgei no Michi (The W of Crafts), Mingei objects were everyday items, massproduced using local materials for practical use and sol affordable prices Their forms were simple and function of necessity, and their beauty lay in their inherent spirit o service

This historical narrative has long shaped discussions of Mingei, but it falls short of addressing the broad concep and contradictions the term encompasses For instance relying solely on Yanagi’s definition raises questions abo his promotion of individual artists such as Hamada Sh the British ceramicist Bernard Leach (1887–1979), and o and his decision to showcase their works in his Minge museum (1) To make sense of these contradictions, this essay attempts to provide an alternate approach by revisiting what Mingei meant for the other two founders

HAMADA SHŌJI AND KAWAI KANJIRŌ

Hamada studied ceramics at Tokyo Industrial College (n the Institute of Science Tokyo) (2), and later secured a position at the Kyoto Municipal Ceramics Testing Institu through his classmate Kawai, who worked there Both institutions provided a rigorous scientific education des to prepare students for the ceramics industry Although Hamada is known to have dismissed the value of his technical education later in life, this foundation was likel particularly useful when he and Bernard Leach were establishing the Leach Pottery from the ground up in St in the early 1920s Recent research claims that Hamada considered such technical knowledge an impediment w he needed to transcend in order to achieve the ideal he for himself (3) He nurtured this ideal alongside Leach at St Ives, where they studied local “folk” pottery, such as slipware,

and reflected on its beauty and how to incorporate its principles into their own work, and Hamada ultimately decided to create objects that were “healthy, natural, and beautiful” (see below)

During Hamada’s time away, Kawai fully utilized his technical training to establish himself as a reputable and respected potter in Kyoto During this time, he began to question the significance of his achievements In search of his purpose and direction as a potter, Kawai pondered some of the characteristics of ‘folk’ pottery how repetition of the potter’s hand movements would simplify forms or transform figurative drawings into near-abstract patterns (4)

It was around this time that Hamada and Kawai met Yanagi, who had moved to Kyoto from earthquake-ravaged Tokyo Yanagi had acquired an appreciation for the beauty of humble objects some years earlier, particularly through Korean ceramics of the Joseon period and the carved

A portrait of Bernard Leach in his St Ives pottery, taken by Ida Kar in 1961

From the Metropolitan Museum of Art permanent collections: Mokujiki Shōnin (1718–1810), Fudō Myōō (Achala Vidyaraja), The Immovable Wisdom King ⽊喰上⼈造不動明王像, 1805, chisel-carved (natabori) wood (h) 90 x (w) 37 x (d) 25 cm Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Portrait of Yanagi Muneyoshi (Yanagi Soetsu) taken at the Japan Folk Crafts Museum in Tokyo, in February 1948 Image courtesy of the Japan Folk Crafts Museum, Tokyo, and Mainichi Japan

THE THREE CONCEPTS OF MINGEI AT ITS ORIGIN

Yanagi, the philosopher, conceived Mingei as a category of craft distinct from both “art craft” (the modern approach to crafts as creative art) and traditional crafts made for the ruling classes

Hamada, on the other hand, viewed the characteristics of Mingei as guiding principles for his own work, which he articulated in the following words:

The three terms that are the core of mingei – health, naturalness, and beauty This is true mingei from my point of view; this is the definition of mingei All of my friends, including Kawai, knew this from the inside and therefore never actually moved away from it (5) [Original in English]

Kawai’s work is often considered “un-Mingei” due to its overt expressiveness, which Yanagi regarded as overly individualistic However, Hamada had a deeper understanding of both Kawai’s work and those of another celebrated potter, Tomimoto Kenkichi About this, Hamada remarked:

People such as Kawai and Tomimoto have trodden their true path, they have eaten folkcrafts and then have developed their own path This is legitimate the natural thing for them

In other words, at its origin, Mingei as an aesthetic was shared by the three men, but its meaning was multi-faceted: for Hamada, it guided the direction of his work; for Kawai, it compelled him to question his pursuit of technical perfection, ultimately helping him forge his own path

Yanagi, on the other hand, felt compelled to categorize, define, and propagate Mingei Hamada explained this conundrum in a recorded conversation with Leach:

[Yanagi] had to use a formula for folk art to illustrate the point that he was trying to make But it was quite clear to Yanagi that this formula was not meant to be followed exactly in our time and age when it comes to producing for those who are artists in need of producing, what is written and formulated about folk art is not enough I am saying that Yanagi knew this and yet he did go on with his thesis (7) [Original in English]

Hamada chose not to voice his concerns until many years after Yanagi’s death, and even then, only in English

ORIGIN OF MINGEI AS THE CRAFT-MAKER’S AESTHETIC

If we focus on Mingei as the craft-maker’s aesthetic, its origins can be traced to the 1910s, when Bernard Leach and Tomimoto Kenkichi (1886–1963) began exploring ceramics outside traditional Japanese ceramic practices Tomimoto is credited with introducing William Morris’ ideas and work to Japan through a series of illustrated articles He admired Morris as a designer who created according to his own taste, rather than following established systems In 1918, Leach wrote that he and Tomimoto had “made a good many pieces in which we have used old Japanese techniques to express European folk motifs ” (8)

Their works were displayed in small galleries in Tokyo, alongside modern paintings and other artworks by their friends (9) Hamada visited these galleries and recognized in their work the direction he wished to pursue (10) Kawai, on the other hand, was bewildered by Leach’s ceramics: “I felt indignant to see [this foreigner] throwing a totally alien kind of life into ceramics we [Japanese] knew and held dear I was incensed at seeing someone beat me to it ” (11)

For Tomimoto, folk ceramics were a constant reminder of what he strove to achieve but could not He observed “the immense power ” and “enduring life” in objects made in the past by anonymous producers, and wrote: (12)

“I hold an old, beautiful ceramic piece, and I’m in pain

People enjoy the Song, the Yi-Dynasty [Joseon period] pieces, but to me, a pain, just pain ”

It was the aesthetic characteristics of Mingei that the first generation of so-called Mingei artists, or dōjin, sought to emulate in their work, each in their own way These qualities continued to guide subsequent generations, including Hamada’s principal student Shimaoka Tatsuzō (1919–2007) and the textile artist Serizawa Keisuke (1895–1984) Serizawa, a versatile artist and designer, was initially drawn to the ceramics of Leach and Tomimoto, but the turning point of his career came when he encountered bingata, an Okinawan stencil-dyed textile technique, at the first Mingei exhibition held in Ginza in 1927 From that moment, he “began chasing bingata ” (14)

In Britain, where ceramic connoisseurship was not as developed as it was in Japan, Leach struggled for recognition as a studio potter Exhibitions in Japan, organized by Yanagi and his other friends, were his lifeline both morally and economically After one such exhibition at Kyūkyodō in Ginza, in mid-1925, Yanagi wrote to Leach that he admired Leach’s “well-digested English galenas (slipware) Because they are born-pottery, not madepottery ” (15)

The remark "born not made" by Yanagi has since become an unofficial criterion of Mingei It is significant in two ways: it was made before the term Mingei was coined, and it referred to Leach’s contemporary work, not the works of anonymous craftsmen from the past Additionally, it echoes Hamada’s definition of Mingei as “health, naturalness, beauty ” Leach, in turn, described Hamada’s work as having “austerity, nobility, simplicity, warmth, and naturalness, all at once ” (16) Therefore, for the craft-maker, Mingei was imbued with those qualities

Anonymous, Wine pot, Joseon dynasty, Korea, with wood box, porcelain, (h) 20 8 x (w) 20 3 x (d) 13 9 cm

Pictured left is an image taken by William Watson, “Fall 1952 Pottery Seminar: Hamada Shoji (1894-1978), Bernard Leach (18871979), Yanagi Soetsu (1889-1961) and Marguerite Wildenhain, (1896-1985)” The image is a digital print from a scan

Image courtesy of The North Carolina State Archives and Black Mountain College Museum

LANGDON WARNER: THE AMERICAN LINK

Yanagi and Leach had a strong ally in the United States In 1916, while Leach was in China, he met Langdon Warner (1881–1955), who later became a curator at the Fogg Museum and a lecturer at Harvard Warner was a frequent visitor to Japan, both for his study of ancient Japanese Buddhist sculpture and as a stopover on his trips to China and Korea In 1928, he and his wife Lorraine, a scholar of Korean ceramics, traveled to Korea with Yanagi, and the following year, Warner invited Yanagi to teach Japanese art at Harvard for a year (17)

Warner’s view of art was inclusive, as demonstrated by his exhibition Pacific Cultures for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco (1939) For its Japan display, Warner included a section of what he called "Peasant Art", featuring many objects from Yanagi’s museum Folk art, Warner wrote in 1952, “is immune from the diseases of snobbery, plutocracy, and the cults it is usually found to correspond to the three transcendentals – the Good, the True, and the Beautiful ” (18) Clearly, Warner saw value in

Yanagi’s originality of thought and his commitment to promoting folk art While Yanagi was in Boston, he and Warner organized an exhibition of Ōtsu-e, folk paintings from Ōtsu, near Kyoto, at the Fogg Museum Warner also invited Yanagi to contribute articles to his magazine Eastern Art

CONCLUSION

I have briefly discussed Mingei as an appreciation of folk art that united individuals from distant locations, yet closely connected by their shared passion for beauty Each person played a role in the international promotion of folk art, or Mingei From this perspective, Mingei is more broadly an aesthetic than a category of objects both a delight for the eye and a source of inspiration for makers By shifting the focus from Yanagi’s Mingei formula to an appreciation of the qualities of folk wares as artistic inspiration, one can gain a deeper understanding of the diverse approaches within Mingei, encompassing a world of aesthetics and connoisseurship that covers much more than Yanagi’s formula

CITATIONS

Note 1: Miyake Chūichi (1900-1980) disagreed with Yanagi’s policy and established Nihon Kōgeikan (Japan Folk Art Museum) in 1950 in which he excluded works by the so-called ‘Mingei artists’

Note 2: Until October 2024, it was called the Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Kōgyō Daigaku)

Note 3: See Sasa Fūta, ‘Science to be “forgotten”: Hamada Shōji’s time at the Ceramics Department [of the Tokyo Industrial College]’, Takeshi Nakajima (ed ), Yohaku No 2, Tokyo: Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2024, 32-43

Note 4: Hamada arrived at Kawai’s in March, and, according to the transcript, Kawai gave a talk ‘Tōki no shosanshin’ at the Kyoto City Museum in April

Note 5: Leach, Bernard, Hamada: Potter, Tokyo/New York: Kodansha International, 1990 (first published 1975), 196

Note 6: Leach, Hamada: Potter, 196

Note 7: Leach, Hamada: Potter, 167-68

Note 8: Leach, ‘Factories and handicrafts in Japan: II Pottery’ The New East April 1918, 328

Note 9: Leach, Hamada: Potter, 92

Note 10: Hamada: Potter, 93

Note 11: Kawai, Hi no Chikai (Pledge of fire), Tokyo: Kodansha, 1996, 64

Note 12: Tomimoto, ‘A water dropper of Yi Dynasty’, Tomimoto Kenkichi Chosakushū (Collected writings of Tomimoto Kenkichi), Tokyo: Satsuki Shobō, 1981, 277

Note 13: Tomimoto, ‘1925’, Tomimoto Kenkichi Chosakushū, 311-12

Note 14: Mizuo Hiroshi (ed ), Serizawa Keisuke Sakuhinshū supplementary volume, Tokyo: Kyūryūdō, 1980 (unpaginated)

Note 15: Curatorial Department of the Japan Folk Crafts Museum (ed ), Sōetsu Yanagi and Bernard Leach letters –from 1912 to 1959, Tokyo: The Japan Folk Crafts Museum, 2014, 85

Note 16: Leach, Hamada: Potter, 197

Note 17: See Ajioka ‘Global Mingei: its pre-WWII origins’, TAASA Review, vol 27, No 3, 2018, 4-6

Note 18: Warner, The Enduring Art of Japan, New York: Grove Press, 1978 (1952), 80

MINGEI & CONTEMPORARY CONCEPTS OF BEAUTY

BY HOLLIS GOODALL

JAPANESE ART CURATOR, WRITER, AND EDUCATOR

CHAPTER 1 `

SETTING THE SCENE THE BIRTH OF MINGEI (1850-1930)

What is beauty today? Depending on the individual, the definition can range from gilded porcelain to rusted motorcycles, minimalist arpeggios to punk rock, and a spring breeze to a raging fire Throughout history, people have often relied on “influencers” to define beauty for them One such figure was Yanagi Sōetsu (also known as Muneyoshi, Japan, 1889–1961)

Yanagi, like the boatman in Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa, navigated a tide of Western influence that he helped amplify as it swept through Japan As he completed high school and began publishing articles on European artists in Shirakaba (White Birch) magazine in 1910, he found himself in a landscape where the Japanese cultural elite was divided in their artistic interests Some celebrated the beauty of chanoyu (the Japanese ritual tea ceremony) and extended their interests to Buddhist and other historical Asian arts Others embraced the Western hierarchy, which prioritized painting and to a lesser extent, sculpture over decorative arts like tea bowls Decorative artists working in ceramics, metalwork, cloisonné, textiles, lacquerware, and doll making faced significant challenges until 1927, when the Ministry of Education officially recognized these fields for their aesthetic value This change allowed their inclusion in the prestigious annual government-sponsored exhibition, commonly known as Bunten

Between 1893 when Japanese decorative arts were first displayed alongside paintings at the Chicago World's Fair and the 1927 Bunten exhibition, decorative artists were excluded from high-profile competitions and awards Instead, their work was displayed with agricultural and industrial goods, diminishing their value as art

Around 1860, in Europe, John Ruskin and William Morris confronted a similar struggle: industrial mass production flooded markets with low-quality goods, sidelining decorative artists By 1887, the Arts and Crafts Movement, spearheaded by the writings of Ruskin and Morris, set an influential precedent on public appreciation of beauty in daily life, subsequently inspiring similar movements across Europe and

North America, and planting the ideological seed of crafted objects as art Their writings reached Japan in the late 1880s, just as Japanese artists were advocating for recognition of their own decorative arts

Yanagi Sōetsu first encountered these ideas of Ruskin and Morris around 1910, when he met English etcher Bernard Leach and Japanese designer Tomimoto Kenkichi, who had recently returned from England Both had studied the Arts and Crafts movement firsthand Tomimoto, inspired by its focus on folk art, explored global folk traditions in the collections of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum Yanagi, who was writing about figures like Auguste Rodin, William Blake, and the Post-Impressionist artists at the time, developed a growing interest in folk art and craft through his discussions with Leach and Tomimoto Meanwhile, Yanagita Kunio (1875-1962) foremost among Japanese folk anthropologists and a key figure promoting folk research, began publishing the journal Kyōdo kenkyū (Local Studies) in 1912, reflecting the rise of regional studies during the 1910s to the 1930s

In 1909, prior to meeting Leach and Tomimoto, Yanagi purchased his first piece in what would become a large collection of Joseon dynasty 18th-century blue and white ware from Korea in a local shop The following year, Japan would claim Korea as a protectorate, allowing budding enthusiasts such as Yanagi, and the Asakawa brothers who became archaeologists and historians of Korean porcelain, to access pieces sold off by Korean families facing straitened circumstances Yanagi’s articles in Shirakaba magazine opened eyes in Japan to contemporary art of Europe, and his subsequent writings on Korea and Korean porcelain inspired some Japanese enthusiasts to develop a new sympathy for the population of their colony Yanagi would remain committed to the beauty of Korean porcelain throughout his life His burgeoning interest in simple designs on luminous white Korean porcelain would plant the seeds of appreciation leading Yanagi to collect and inform the Japanese public about folk art

Tomimoto Kenkichi 富本憲吉 (1886-1963)

Jar, Pattern of wild berry on brushed slip, Iron brown, 1930, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 12 7 × (diameter) 15 2 cm

Tomimoto Kenkichi 富本憲吉 (1886-1963)

Jar, Pattern of four petaled flowers with persimmon glaze, 1934, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 15 2 × (diameter) 19 0 cm

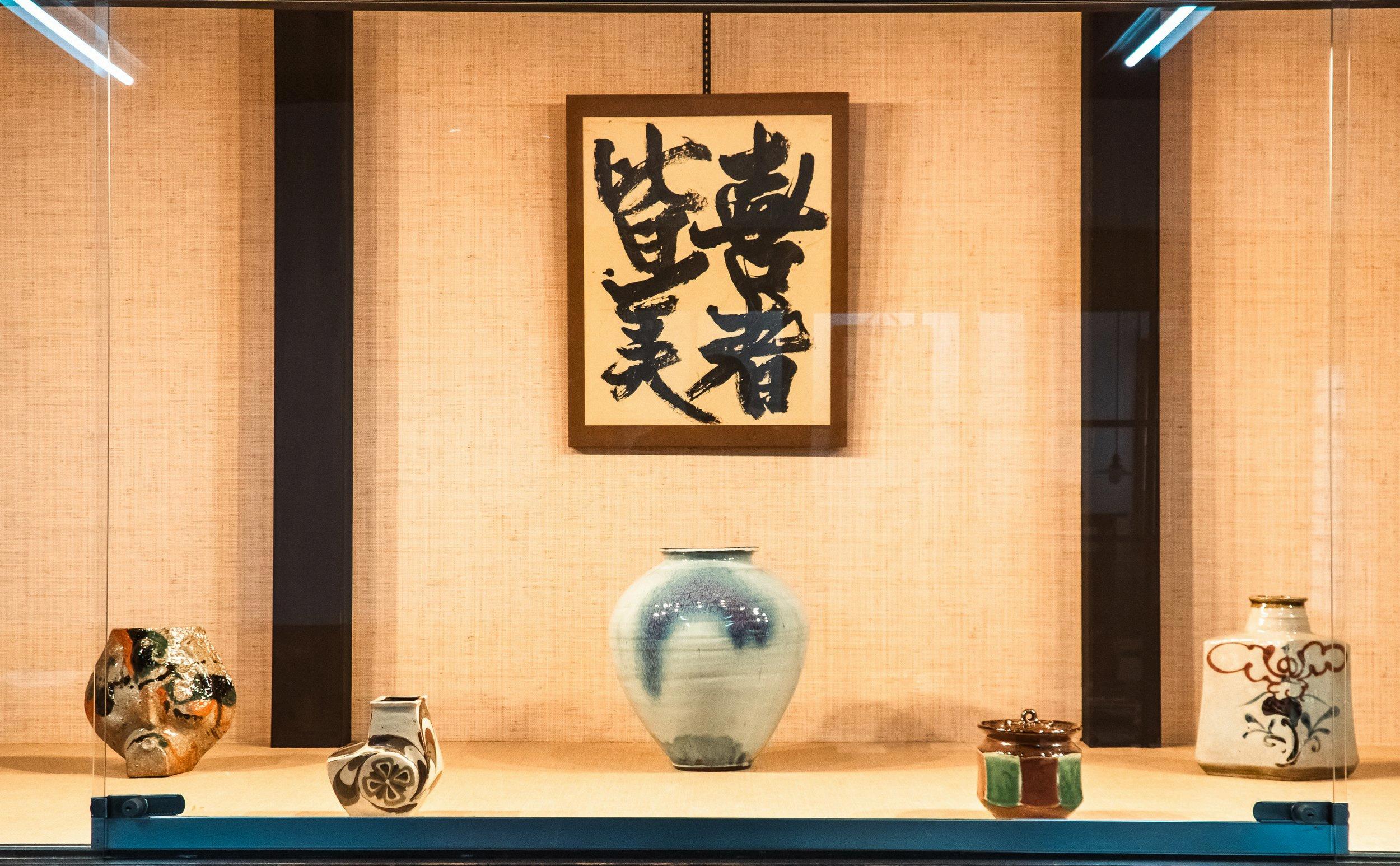

Tomimoto Kenkichi 富本憲吉 (1886-1963)

Painting with pattern of characters for "Wind, Flower, Snow, Moon" 風花雪月, cia 1950's

White slip painting on color paper

Image: (h) 41.5 × (w) 59.5 cm

Mount: (h) 63.8 × (w) 81.3 cm

Bernard Leach (1887-1979)

Faceted flower vase with black iron glaze, with signed wood box, Signed by Hamada Tomoo

stoneware, (h) 36 8 × (diameter) 19 8 cm

Kobayashi Togo 小林東五 (b. 1935)

Flat jar with black glaze, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 17 × (w) 16 × (d) 14 cm

Takesue Hiomi 武末日臣 (b. 1955), black glazed jar in the form of a 15th century Korean bale of rice 扁壺黒, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 23.4 × (w) 17 × (d) 20 cm

Anonymous, Faceted jar with lid, Joseon (Lee) dynasty, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 25.4 × (diameter) 21.6 cm

amber-glazed

Dong-Oh 안동오, Porcelain water dropper, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h)

THE CHARM OF THE SCHOLAR’S DESK

A water dropper is an essential tool for calligraphers, traditionally included in the set of implements necessary for both writing and painting, alongside the "Four Treasures of the Study ⽂房四寶" brush, ink, paper, and inkstone These droppers, often crafted from ceramic, feature elaborate shapes and intricate designs While ceramic is the most common material, jade and metals like copper and brass have also been used in their creation Ingeniously designed, ceramic water droppers have hollow bodies with two small holes, one for water and the other for air, allowing controlled droplets to

fall onto the inkstone, ensuring that only a few drops are released at a time In Japan, these objects are known as “Suiteki ⽔滴" (it’s literal translation meaning "water droplet") These fascinating small objects, which originated further west in Korea and China, offer unique insights into the world of calligraphy, scholarship, and literati culture

The appreciation of calligraphy as a sophisticated craft, an art form, and a vehicle for ideological or religious expression in Japan dates back to the 6th century AD when Buddhism and Confucianism were introduced to the country At that time, Chinese calligraphy entered

Faceted

water dropper, Joseon dynasty, with wood box, stoneware, (h)

Ahn

1

2

Takagaki Atsushi 高垣 篤, water dropper with celadon glaze on red clay, with signed wood box, Celadon glazed stoneware, (h) 6 5 × (diameter) 7 5 cm

Takenaka Ko 竹中浩, faceted round white porcelain water dropper, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 9 × (w) 10.3 × (d) 9.6 cm

Japan, particularly in the form of sutras and commentaries, written in various scripts using brush and ink on paper However, it wasn't until the late 18th century that water droppers became popularized as an essential scholarly tool in Japan and valuable form, following the influence of erudite culture imported from Korea's Joseon courtly world

Over time, Japanese potters, artisans, and ceramic enthusiasts have embraced these charming objects, recognizing them as integral to the process of scholarly reflection The significant influence of Korean ceramics within the Mingei movement may explain why modern

masters of Japanese folk pottery, such as Hamada Shoji created water droppers as part of their archetypal repertoire The ingenious two-hole design of the object serves as a welcome form for those who deeply contemplate functionality

It is pertinent to note that in contemporary society, the use of water droppers is no longer confined to the erudite elite; instead, it symbolizes personal introspection among other things

Anonymous, Wine pot, Joseon dynasty, Korea, with wood box, porcelain, (h) 20 8 x (w) 20 3 x (d) 13 9 cm

Ahn Dong-Oh 안동오 (1919-1989, Designated an Intangible Cultural Asset for Pottery in South Korea, 1976) Large porcelain jar, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 26.6 × (diameter) 31.7 cm

Kawai Kanjiro 河井寛次郎 (1890-1966)

Flat jar, c. 1955-1959, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 23.3 × (w) 17.0 × (d)10.6 cm

Hamada Shoji 濱田庄司 (1894-1978)

Black glazed flower vase, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 20.8 × (diameter) 17.2 cm

(Right) Hamada Shoji 濱田庄司 (1894-1978)

Amber glazed tea bowl with finger painting, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 9 × (diameter) 12 5 cm

(Left) Shimaoka Tatsuzo 島岡達三 (1919-2007)

Amber glazed water jar on rope impressed inlay, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 19 8 × (diameter) 19 cm

Shimaoka Tatsuzo 島岡達三 (1919-2007)

Large jar 壺, Stoneware, (h) 31.7 × (w) 30.4 cm

Gosu rectangular box 呉須筥, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 7 × (w) 11.2 × (d) 7.2 cm

Two small containers by Kawai Kanjiro 河井寛次郎 (1890-1966) Pentagonal box in Shinsha glaze, stoneware, (h) 7.6 × (w) 8.8 × (d) 8.8 cm

THE CULMINATION OF MINGEI

AND A NATIONALIZED MINGEI AESTHETIC (1925-1945)

Since the mid-1880s, Japan countered wholesale Westernization while it aligned with the military and industrial capacities of the West For many artists, as well as industrial leaders, modernization had meant Westernization Writers and lecturers of the 1880s such as Okakura Tenshin and Ernest Fenollosa, whom Yanagi would later emulate, warned against the Japanese losing what was essential to their culture For the next 40+ years, cultural historians endeavored to define and promote precisely what that meant

Searching for the nucleus of Japanese aesthetics, generations of art critics argued variously for sending artists for study in Europe to bring back what was new; for recognizing East Asian Buddhist icons as art; for re-engaging with tea-related Japanese aesthetics such as wabi, sabi, yūgen, shibui and others; and then from 1925, at the behest of Yanagi, for reexamining Japan’s rural zones for their arts seeking a path to modernize in an essentially Japanese way

Also coming from Europe was socialism and the social equivalency that political philosophy promised One returnee from Europe who chose a Russian route back to Japan was the printmaker Yamamoto Kanae (1882-1846) Yamamoto effectively set the flame that led to the creative print movement (lasting from 1904 to about 1960), and significantly for Mingei, began a rural art movement based on socialist models training farmers to make prints and crafts for auxiliary income Such subsidiary work in rural areas had dwindled as farmers’ offspring migrated en masse to the cities for work Yamamoto’s rural art movement organized through cooperative guilds formed a network for Yanagi’s later efforts at training local artists in Mingei aesthetics

Intrigued by the socialist ideals for enhancing the lives of rural workers, Yanagi discovered the beauty of folk Buddhist carvings by the monk Mokujiki Shōnin, and through those, folk art, whose parameters Chiaki Ajioka discusses in her essay Yanagi would mine folk arts for the heart of beauty in Japanese terms In this period from the mid-1920s to the 1930s his concentration was on the social and spiritual aspects of folk art, its honesty, humility, and the perceived transfer from a godly “other power ” of simple beauty allowed through the artisan’s dependence on kinetic memory

In Ajioka’s essay, one sees Yanagi converting the educated elite to what he termed “Mingei” (minshūteki kōgei, or “folk craft”), through writings, the Mingei Association which he started with Hamada Shōji, Kawai Kanjirō and Tomimoto Kenkichi, and the creation of a museum, Nihon Mingeikan (The Japan Folk Art Museum) which opened in 1937 The Mingei Association would later access the rural art movement organization of Yamamoto Kanae to start regional crafts initiatives, spreading Mingei training nationwide

As interest in Mingei proliferated, the attitude veered from the social aspect to a more nationalistic intent of extolling uniquely superior facets of Japanese culture in East Asia In the postwar era, Mingei became a means of supporting cultural exchange between Japan and its new American and European allies

Kanjiro 河井寛次郎 (1890-1966)

A stoneware flask with Gosu glaze 呉須扁壷, c 1961, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 20 3 × (w) 18 8 × (d) 14 3 cm

Kawai

(Above) Sam Francis (1923-1994), Untitled, 1955, watercolor on paper, mounted on canvas, (h) 76 2 x (h) 56 5 cm. Image © 2023 Sam Francis Foundation, California / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York & the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Hannelore B. and Rudolph B. Schulhof Collection.

(Right) Kawai Kanjiro 河井寛次郎 (1890-1966), shallow bowl with hakeme glaze on yellow clay, 1955, with signed wood box, Exhibited at Takashimaya department store in Osaka in 1959, stoneware, (h) 6 3 × (diameter) 27 9 cm

Two hands 双手, painting on wood panel

(h) 8.8 × (w) 13.9 cm

(h) 29.2 × (w) 23.8 cm

Serizawa Keisuke 芹沢銈介 (1895-1984)

Image:

Mount:

Serizawa Keisuke 芹沢銈介 (1895-1984)

Portrait of a dyer, signed at the right bottom Kei "銈", Reverse glass painting

Image: (h) 13 × (w) 10 cm

Mount: (h) 26 7 × (w) 23 6 cm

Clouds 八雲, stencil dyed washi paper

Image: (h) 5 5 × (w) 14 cm

Mount: (h) 22 5 × (w) 27 8 cm

Mount: (h) 29.2 × (w) 23.8 cm

Image: (h) 8.8 × (w) 13.9 cm

Serizawa Keisuke 芹沢銈介 (1895-1984)

Umbrella 傘, Japanese paper with stencil dye, wooden frame with glass cover

Munakata Shikō 棟方志功 (1903-1975) Festival of the sun and the moon 太陽と月の祭り, 1957, woodblock print, Image: (h) 18.7 × (w) 39.3 cm, Frame: (h) 26.6 × (w) 52.0 cm

POST-MINGEI MINGEI AND ITS LEGACY AFTER 1945

Much attention post-1945 went to the creative art-craft artists who imbued their pottery with the virtues of folk craft Tomimoto Kenkichi, who distanced himself from the Mingei movement in the mid-1930s, turned his focus to overglazeenameled porcelain of the Kutani style One can see the shift in his approach comparing his Jar, Pattern of Wild Berry on Brushed Slip, Iron Brown of 1930, and his Jar, Pattern of Four Petaled Flowers with Persimmon Glaze of 1934 Tomimoto’s motto, “ never make a pattern from a pattern, ” manifests in the naturalistic rendering of a berry vine leaf over the Korean-style hake brush strokes on his earlier, quietly toned stoneware jar By 1934, he transformed flowers into symmetrical quatrefoil arrangements, laying the foundation for the complex overglaze enamels he perfected in the 1950s and 1960s

Hamada Shōji, always loyal to Yanagi, created powerful objects by drawing deeply on his rural experience in Mashiko His Plate with Chrysanthemum Motif evokes the shadowy silhouette of wild chrysanthemums against a paper window in a countryside setting Iron Glazed Square Bottle with Finger Mark & Persimmon Under Glaze bears his unmistakable touch, presenting a shibui (briefly defined as an “ economy of means”) design perfectly suited to mid-century modern environments Hamada’s Large Plate with Black Glaze, inspired by Seto plates with “Horse Eyes” designs, bridges past and present, referencing both traditional motifs and the experimental calligraphy of the late 1940s and 1950s Though Hamada often relied on assistants to shape his pottery, the final brushwork was always his own, infusing his creations with bold expression and dynamic energy echoing Abstract Expressionism Hamada’s deceptively simple but invariably fascinating works continue to compel with their clarity and vitality

Kawai Kanjirō taught and lectured with Yanagi around Japan, providing models for emulation to rural potters In producing his own ceramics, Kawai was blissfully isolated in his Kyoto workspace pursuing his interests in glaze and shape while Yanagi lived in Tokyo, maintaining little sway over Kawai’s work

Kawai’s lifelong experimentation with glaze is evident in his Shallow Bowl with Yellow Glazed Clay Hakeme of c 1955, whose swirling motion calls to mind the current foot paintings of Gutai artist Shiraga Kazuo (1924-2008) As Shiraga’s paintings foreground the qualities of paint, Kawai’s bowl emphasizes the varied features of glaze

Kawai’s Stoneware Flask with Gosu Glaze combines a cobalt glaze (gosu) that had been used in Arita since the seventeenth century with a mold-made body bearing exaggerated bosses and loops, producing an activated form and surface design within a single, rich tone This piece could function in a space with or without flowers, though it was likely made initially for avant-garde ikebana flower arranging

True folk craft employs simplified designs and shapes as the wares were made in large quantities The generations of artists inspired by pre-modern Mingei Tomimoto, Hamada, Kawai, and their associates and present-day followers rely on compelling forms with essentialized designs The original attraction to folk crafts by Yanagi came from his search for keys to Japanese beauty, for the role that folk crafts could play during lean years on the farm, as a focus for the copasetic socialistic organization of mutual support within local villages, and for how his contemporaries as art-craft makers could be inspired by their healthy vitality As we look at these works today and inquire about their beauty, the subtle sophistication of these artists’ pottery, fabrics, and prints fascinates us endlessly

Influencers of the present moment often encourage us to look at works by artists outside of the mainstream, and folk craft presents us with that option Artists like Tomimoto, Hamada, and Kawai are exemplary artists who looked beyond the products of universities and ateliers to workshops of humble artisans for designs whose virtues could last through the modern era, no matter what forces momentarily drive culture

Hamada Shoji 濱田庄司 (1894-1978) Plate with chrysanthemum motif, with signed wood box, Iron glazed stoneware, (h) 6.3 × (diameter) 31.2 cm

NOTES ON E-SETO BY LUIGI ZENI

The term e-seto 絵瀬戸, literally “picture Seto,” refers to a type of painted ceramic produced in the region of Seto, in Aichi Prefecture Seto is recognized as one of the oldest and most important ceramic centers in Japan, dating back to the Kamakura period (1185–1333)

The many folk kilns scattered around the region have been manufacturing utilitarian ceramics of various types throughout the centuries up to the present day Experimentation with glazes and the variety of colors are some of the main characteristics of Seto ceramics: black, white, green, iron red, and ash glazes, as well as white and blue porcelain The folk production of ceramics in Seto, particularly by anonymous

craftspeople and t heir aesthetics, received significant attention and appreciation during the first half of the 20th century This category of ceramics was widely admired and eventually celebrated under the term “Mingei ⺠芸, ” or “folk art,” coined in the 1920s by the renowned philosopher and art historian Yanagi Sōetsu (1889–1961) Later, in postwar Japan, Seto was classified by ceramic scholar Koyama Fujio (1900–1975) as one of the Six Ancient Kilns of Japan – a cultural classification designated as “Japan Heritage” by the Agency for Cultural Affairs in 2017 Along with five other remarkable ceramic centers, Seto has been continuously producing pottery since the Middle Ages, maintaining a long history of exquisite craftsmanship in constant evolution

(Left) No 1 Plate with horse eyes motif, 19th Century (Late Edo period), stoneware, (h) 4 0 × (diameter) 20 8 cm

(Middle) Plate with monk viewing a landscape of Mt. Fuji, 19th Century (Late Edo period), with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 4 0 x (diameter) 24 6 cm

Today, many artist-potters base themselves in Seto, drawing inspiration from local techniques and visual languages, incorporating many historical motifs

One common trait of e-seto stoneware is that it is made from the bright clay derived from the soil in the Seto area

Potters around Japan praise this particularly light and creamy clay as one of the best surfaces for painting motifs Seto clay is transported around the country, even as far north as kilns in Kushiro, Hokkaido Some e-seto motifs are inspired by Korean ceramics from the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) This influence is most prominently observed

during and after the Imjin War (1592–1598), when many Korean potters were brought to Japan, introducing new technologies and aesthetic appeal Two key aspects of Joseon ceramics, which also recur in e-seto ware, are the simplicity of the designs and the natural motifs Some of them reflect Confucian ideals of simplicity and harmony through their elegance, which corresponded to minimal designs rendered with only a few brushstrokes on the ceramic surface

Tomimoto Kenkichi 富本憲吉 (1886-1963)

Small covered jar with motifs of bamboo leaves 絵高麗小壷, 1935, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 9 5 × (diameter) 11 cm

Fujimoto Yoshimichi (Nōdō) 藤本能道 (1919-1992)

Covered decorative jar with rose drawings, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 16 × (diameter) 14 cm

Hamada Shoji 濱田庄司 (1894-1978)

Iron glazed square bottle with finger mark & persimmon under glaze, 1970's, with signed wood box, Authenticated by Hamada Shinsaku, stoneware, (h) 22 8 × (w) 15 7 × (d) 7 6cm

Hamada Shoji 濱田庄司 (1894-1978) Tenmoku glazed vase, with signed wood: signed by his son, Hamada Shinsaku, stoneware, (h) 29 × (diameter) 13.5 cm

Murata Gen 村田 元 (1904-1988)

Jar with iron and rice husk glaze, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 20.3 × (w) 12.7 × (d) 12.7 cm

Murata Gen 村田 元 (1904-1988) Pitcher with persimmon glaze, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 25.9 × (w) 24.1 × (d) 20.3 cm

NOTES & PERSPECTIVES

Pictured above and below is Kawai Kanjiro 河井寛次郎 (1890-1966)’s home in Kyoto, which has since been converted into a museum, where visitors can experience a unique Kyoto-style house which is also inspired by Western rustic architecture The house, which was converted to a museum by Kawai’s granddaughter Tamae Sagi, also showcases many of Kawai Kanjiro’s ceramic works Image credit: Genji Kyoto

Pictured above is the climbing kiln (Anagama, ⽳窯) used by Hamada Shoji The kiln was taken from it’s original location and relocated to what is currently the Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art Image courtesy of the Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art, and Stephen Mansfield Photo for The Japan Times, 2014

Pictured to the right is an E-Seto dish in the permanent collections of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in the United States

The plate, like many from this period, was crafted by an anonymous craftsman in the Seto region, showcasing the impressive technological scale of production during this period Like the E-Seto plates featured in this catalog, this work is made from stoneware with an underglaze of iron oxide

Plate with "Horse Eye" design (or "Flaming Jewel" design), 18th century, (h) 5 08 × (diameter) 26 67 cm, Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation Image courtesy of the Musuem

Pictured on the left here is a E-Seto dish on display in the ceramics gallery at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom also crafted in the 18th Century, from the Seto region

Both E-Seto plates pictured here features the classic umanomi (⾺の⽬) or "Horse Eye" motif embellishing the border of this plate Hamada Shoji’s reinterpretation of this classic motif showcases the long-lasting impact of e-Seto ceramics The work is displayed alongside other ceramic objects from the 19th century from Japan Image courtesy of Dai Ichi Arts, LTD

(Above) Various accompanying wooden boxes of pieces featured in this exhibition, showing Hamada Shoji’s signature in calligraphy “庄司” , or “Shoji”

(Right) Shimaoka Tatsuzo’s accompanying wooden boxes showing his seal and signature that reads “達三” or “Tatsuzo”

(Left) A seal of Kawai Kanjiro’s, as featured on the accompanying wooden box of his Gosu glazed rectangular container, as featured in this exhibition catalog

(Left) Hamada Shoji’s seal, as found on the accompanying signed paulownia wooden box of his amber glazed tea bowl with finger drawings, as featured in this exhibition catalog

(Left) On the foot of many vessels by Bernard Leach, viewers can see his potter’s seal impressed onto the clay surface The seals often either include his initials "BL" in various fonts, or a symbol representing "Leach Pottery"

(Left) Many pots created by Mingei artists associated with Bernard Leach or Hamada Shōji are often accompanied by wooden boxes bearing authentication seals from Hamada Shōji’s descendants his son, Hamada Shinsaku, or his grandson, Hamada Tomoo, as seen with the box accompanying Bernard Leach’s jar Today, Hamada Tomoo continues to operate Shōji’s historic kiln, preserving the legacy of Mingei

(Right) Tomimoto Kenkichi’s signature, from the 9th year of the Showa period, 1934

Tomimoto always signed his works with 富 or “Tomi” The pictophonetic nature of Kanji characters offers much room for imagination, and he would often create little changes in the character, such as here, in which he had reimagined the upper radical of the character as a mountain

(Left) An example of Tomimoto Kenkichi’s reimagination of the upper radical of his signature “Tomi” (富) This signature is on the foot of his porcelain jar with four-petaled sometsuke designs, featured in this exhibition catalog

(Right) Another variation of Tomimoto Kenkichi’s signature “Tomi” (富) This signature is on the foot of the incense vessel with bamboo designs draw in iron oxide underglaze, as featured in this exhibition catalog

(Left) Murata Gen often signed his pots with the character “Mu” (む), a distinctive choice that set him apart from other Mingei potters of his time This unconventional signature is evident on the small square jar with iron glaze featured in this catalog

(Right) Kawai Kanjiro’s signature and seal stamp In ink, Kawai Kanjiro has signed “寛” or “Kan”, alongside one of his seals stamped in red ink, on the accompanying wooden box of a piece in this exhibition

Pictured above is the Nihon Mingei Kan, or Japan Folk Crafts Museum The museum is located in Tokyo, Japan, and is dedicated to Japanese folk-crafts and highlighting its impact on modern ceramics, as well as society The collection includes many important objects from the Mingei Movement Image courtesy of Dai Ichi Arts, LTD

© Dai Ichi Arts, Ltd , 2025

Authorship: Beatrice Chang, Chiaki Ajioka, Hollis Goodall, eds Kristie Lui

Catalog production: Haruka Miyazaki 宮崎晴⾹, Yoriko Kuzumi 久住依⼦

Photography: Yoriko Kuzumi 久住依⼦

Editorial & design: Kristie Lui