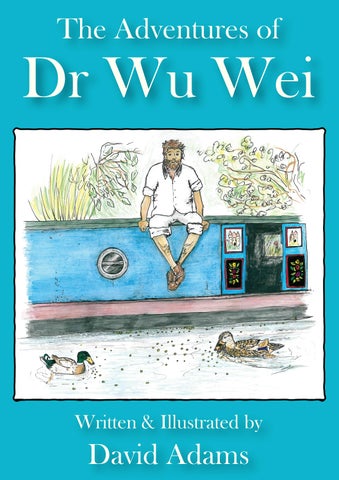

The Adventures of Dr Wu Wei

Written & Illustrated by David Adams

T he people who provide and are supported by mental health services.

A special thank you to Jen nifer Renee Tuft for helping me edit this story.

They say, 'Write what you know.' I wrote this in 2023 after completing my first year studying for an MSc in psychology. I'm 36 years old with a background in the arts, design, and bespoke tailoring. Over the years, I have struggled with the mental health condition bipolar disorder.

While studying, I work part-time as a facilitator for the mental health charity Mind. There, I run an art group for young people, which promotes mental well-being through creativity. I have a passion for philosophy, art, neuroscience, language, and consciousness. I like to explore these concepts in my creative work.

This is my first time sharing my writing with an audience, so I welcome any feedback. If you enjoy this, please consider supporting me at: https://gofund.me/599d8ddb."

W illiem sat on his roof bathing in the dispersed sunlight. Scattering through the leaves and refracting back at him like a kaleidoscope off the passing river. He enjoyed his peaceful morning coffee and hand-rolled cigarette. He enjoyed this almost every morning come rain or shine, dawn chorus or frozen fog. Not every morning of course, he was only human. But after living on a narrowboat for a number of years, that routine was always a peaceful reminder, that everything was ok. ‘Everything being ok’ was mostly a matter of perspective. But having the calming serenity of nature around, gave Williem moments to embody that perspective. Reminding him that everything can be ok, even when it feels like it isn’t. Exactly the reason he left the city and bought a boat in the first place.

Another day, another morning, quietly observing the movemen t of things. The subtle things. T he things that unless you slowed down and stayed still, you probably wouldn’t notice were moving at all. The more Williem learned to observe the more he saw some sort of truth. A truth that life was all around. Within every square inch of his focused attention , there was fractal complexity. It wasn’t the case of looking for it in this spot or another. Rather, an allencompassing topography of reality…life. It reached out in all directions, including inward through himself. The term ‘tapestry’, came to mind. Having heard that before, but the description now seemed to carry more semantic wisdom .

He imagined this sort of philosophical insi gh t was akin to that of a psychedelic experience from LSD , psilocybin, or DMT. Or quite possibly the same enlightenment, that came from religious euphoria. Williem felt a mild smugness in the know ledge that he didn’t need to ingest chemicals or become indoctrinated to achieve this. Although humility rebalanced that smugness. ‘No road to peace is without its criticism ’, Williem thought to himself. Someone with a certain set of PhDs and the DSM -V (The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) could easily describe and diagnose what he was experiencing, as a symptom of ‘Mania’. But he was ok with that. Being Bipolar he had experience mania before, which certainly resulted in the disorder of his life. However, this felt much more like ‘mental order’. After all, what some people call mental illness others just call the human condition . Most mornings were spent like this. Watching the fish and the birds. Or feeding the ducks while his mind went to the playground.

T hen this morning was different. This morning he felt cold blood run th rough his body. The same coldness from a rush of

noradrenaline after a near miss with a car, when step ping off the curb without looking. Or the high acuity of awareness that comes after an accident and you can see too much of your own blood on the outside of you. Occasionally enough, while quietly observing nature, it might throw something unexpected at you. Something that jacks your heart rate up and makes you say ‘W hoa’. For example, w itnessing an animal catch, kill, and eats its pre y right in front of you. A sight that will make you more awake than the strongest of coffee.

Again this was not that. There had been no such animal death, no such near miss . Such as slipping on the damp roof of his boat, which usually puts his heart in his mouth . He h ad just sat down to drink his coffee, the temperature of which was now competing with his stone cold hand. The sensation he was feeling was an anxiety coming from the fact that his reality had changed. Changed in a seemingly illogical way. He could feel a fight/flight/freeze reaction manifesting itself. His body wasn’t moving. It went with freeze. It’s n ot that he couldn’t move, it’s just that his brain was so p reoccupied with trying to find a rational explanation, that it would’ve taken someone else to remind him he had a body at all. This wasn’t a ‘did that just really happen?’ moment. N o, this moment was continuing to ha ppen. The answer to whether it was really happening, should have been much easier to answer.

“You’re not going mad ,” said the crow sitting a few feet away, “of course that depends on your definition of insanity.”

“But…what… me? I mean, but how …I mean ; excuse me?” Williem grasped for a question like a drunk trying to put his key in the door.

“Are you asking me how I can understand what you’re saying?” The crow asked calmly.

“Well yes… and how can I understand you for that matter?!” Williem asked in return.

“I’m not entirely sure, I am just a crow after all,” Williem felt like this response had a hint of sarcasm .

“Maybe because you’ve started listen ing, and as for understanding you… I’ll have you know I’m one of the best in my family at understanding English.” the crow continued.

Williem had always talked to the animals, mostly giving them a friendly hello. But this morning when Williem said ‘Hello Mr Crow, how are you doing?’ he never expected a response. Hearing the crow say “Good thanks, but I wish someone who understood would ask me more often .” This startled Williem , in turn , this startled the crow. After a back and forth of ‘Y ou can understand me?’, ‘Y eah, you understand me?’, the crow seemed rather at ease with the situation. Williem was not, Williem was question ing if he’d had a psychotic break or if he was still asleep.

Williem had to do a sanity check. He had been asked in many mental health questionnaires whether he heard voices. To which, he responded with a debateable ‘no’. He always thought that it depended on what they meant by ‘heard voices’. Sure he heard multiple voices. But recognised that they were all him. T he ones that argue whether to get up or stay in bed. The ones that were thankful when he did something awesome. The ones that try to trick him into doing something he shouldn’t, or the ones that told him he’s worthless and should kill himself when he was depressed . He just thought he had a particularly vocal form of consciousness. O ne he was spending his life learning which parts to take notice of, or which ones to ignore. He did not think these were the voices that the doctors meant when they asked. Assuming that if he was schizophrenic, it would sound more like a stranger’s voice in one’s head. His weren’t like that so he always answered ‘no’.

On this day it did seem like a stranger’s voice. For one thing, it had a different accent compared to his inner voice. But it must be in his head because cro w s don’t talk. This worried Williem. He tried to analyse and describe it but all he could

come up w ith was that it sounded exactly how you might think a crow talking would sound. Like asking ‘W hat colour is the day Thursday?’, or ‘What does blue smell like?’ you will have your own word for it, and you just feel what that is.

Williem tried to focus on the noise coming from the crow. He was hearing English but if he concentrated hard enough he could hear normal squawking. Comparable to one of those magic eyes pictures, but in reveres. O r saying one word over and over till it losses its meaning (potato, potato, potato, popato, popapo, putopato, putoppooatoo). It w as a strange auditory illusion, the harder he concentrated on the bird talking, the less it made sense and the more it just sounded like a bird (which was paradoxical because to Williem , birds sounding like birds was supposed to make sense). However, just listening he could understand what the crow was saying perfectly.

“This is weird !” Williem proclaimed.

“You’re right, this is new to me. And I’ve not heard of someone going from zero to almost fluent comprehension overnight.” said the crow , in a way that if it could, it would be rubbing its chin.

“Y ou mean other people can understand you?”

“I’ve never met anyone, but it’s been known. Hearsay tells of certain individuals across the globe and throughout history , having had such an ability. For some, they were born with it. For o thers it presented itself in their childhood development or puberty. Others have had the ability to a lesser extent,

close to a two-way conversation, but never quite made the leap to understanding.”

“Jesus Christ!” Williem proclaimed some more.

“Y eah , he was one of them, apparently. But that’s just what I’ve heard, us birds don’t write things down, so we take ‘facts’ with a grain of salt.”

“D on’t you mean, a pinch of salt?”

“N o, I mean a grain of salt.” snapped the crow.

The confused adrenaline was starting to w ear off, replacing it was a mild annoyance, feeling like this crow was giving him sass.

“I must have lost it, I’m going to have to start taking antipsychotic medication… and I was doing so well without it. People said if you move to the country side you’d go insane. A crow speaking English, this has got to be all in my head!”

“Of course it’s in your head.”

“W ait what?” Williem was confused, was his own psychosis confirming it was psychosis?

“I mean, I can’t really validate the state of your sanity, I’m not a doctor. But I’m not speaking English, that’s in you r head.”

“I knew this couldn’t be real, I’ll have to phone my doctor.” Williem sighed and reached in to his pocket for his phone.

“I said I’m not speaking English; I didn’t say I wasn’t real.”

All Williem could say was, “I’m confused.” pausing halfway th rough retrieving his phone.

“Aren’t you getting your doctorate in psychology?” the crow asked.

“W ell yes, but how do you…” Williem tried to ask how the crow knew that but was cut off.

“I’m speaking in my natural language , but some part of you r brain seems to have unlocked a comprehension for it. Make sense?”

“Not really.” Williem replied, somewhat bemused.

“You realise that goes for all animals right? We all understand each other – mostly- and humans – again mostly- it’s you lot that are the odd ones out.” T he crow continued.

“There will be different levels of comprehension depending on the species, and the individual animal of course, lucky I was here.” S aid the crow smugly. “Crows are quite intelligent I’ll have you know, plus we tend to find you humans somewhat fascinating. S o there’s a healthy amount of crossover when it comes to contextual comprehension .”

Williem felt like this crow was trying to show off how smart it was.

The crow continued some more, “It is interesting that you seem to have such clarity from seemingly now here. It has been m y philosophy that humans probably all posse ss the ability, but lack the open -mindedness to hear or perceive

what’s right in front of them. That, or it’s some sort recessive gene that only rarely unlocks in a particular time or environment.”

Williem looked around. It’s one thing to be having a conversation with a crow, but it’s another to be lectured by one on the subject of epigenetics. Someone must be pulling some sort of elaborate prank on him.

“How the hell do you know about recessive genes?” He asked.

“Look just because I’m a bird doesn’t mean I’m stupid. In my family, I’m the smartest, thank you. Except, if you ask them they might say my cousin Terry. B ut I maintain that just because he’s good at arguing doesn’t make him that smart.” The crow went on , with an air of insecurity, as if it was trying to convince itself.

Strangely enough, this level of ‘humanity’ felt rather comforting to Williem . Long gone had his cold rush of noradrenaline , and now had a familiar feeling of enthusiastic curiosity. The one that came with meeting a new person.

The crow added, “Y ou know I can read as well?” all pleased as punch.

“W ell no, I mean… I only found out you can talk, a minu te ago”.

“Oh yeah sure, newspapers, flyers, container s that have food in them .” They both paused momentarily, as people do with any conversation when the subject of food is brought up.

“Ok let me get this straight, so you r saying animals can understand humans, but we can’t understand you? But people are always trying to communicate with animals. It doesn’t seem like there is much indication they can understand us.”

“First of all, like most things communication is a spectrum .” T he crow states sharply, making Williem focus on the steellike shininess of its beak.

“It’s the same with human communication , no? T here is a spectrum of comprehension , context, ability, dialect, etc. It’s the same with animals. Ranging not just between species, but

also within. But yes, most birds, mammals, and intelligent animals can all understand each other and can understand humans. But most animals don’t really pay any attention to you. It also pays to be cautious of humans, even the nice ones can be unpredictable. T hose of u s who are interested, do so in a somewhat distant fashion. A nd just because we can understand you doesn’t mean we should automatically do what you say , like some circus act. Especially since the conversation doesn’t go both ways.”

“Well ok… ” Williem tried to reply but the crow was starting to monologue as if he had been waiting to talk to a human and get this off his chest.

“You humans are rather self-involved. I get it, you’ve got opposable thumbs which means you can do and m ake a lot of interesting stuff. B ut it seemed to have separated you from th e trillions of conversations and interactions all us animals are having every day. I just have to say, for humans who think they are so smart, and supposedly the ‘masters of the universe’, you mostly just use those thumbs to eat crap food, masturbate, watch TV, and get depressed…y ou know you should learn to shut your curtains.”

“Hey! Nosy!” Williem say, as he thought that might have directed at him personally.

“Look, no judgment. In fact, most of our animal existence is based around eating, sex, thinking, and talking. Watching you behave more like animals is fun for us, and makes us think there’s hope for you yet. All that extra stuff you lot worry about seems not to do you any good. ”

Williem couldn’t help but agree somewhat. He had definitely seen improvements in his mental health when he became

more accepting of himself. People are flawed and primal, he thought, but it seemed to him that constantly fighting it was exhausting.

“You humans are a sort of curiosity, fun to mess with. Like defecating on your car after you ’ve just washed it.”

“Hey! I knew you birds did that on purpose!”

“We know you know, or at least think you know , but you can’t be certain, which makes it never not funny.”

It suddenly dawned on Williem that there was an unusual amount of birds around in the trees, now paying attention to what he was doing. The normal chorus of bird song had transformed into a hum of slightly out-of-range conversations. Like sitting alone at a fairly quiet but large train station.

A journey of emotions was evolving in him, tumbling from one to another. From confused shock to excited intellectual fascination . N ow Williem started feeling uneasy. The once solitary peace that came from sitting amongst nature, started to feel more like the social anxiety of going to a pub. Williem had always felt a connection with animals, that there was a purity and magical quality to them . They were unburdened from the lack of complexity that was human social interaction. He enjoyed a peaceful voyeurism as opposed to being an active participant.

Thankfully and surprisingly that anxiety didn’t last long, as the emotion of connection started to wash over it. A stronger sense of belonging, rather than a feeling of being an outsider looking in. He had 35 years of feeling like that, which he was

just starting to make peace with. Now , that w as quickly being replaced with a sense of being a part of the universe, rather than a mere observer. At first, he thought it was unusual for him to be so at ease in the light of this new understanding, that it was taking root so quickly. B ut it occurred to Williem that this was probably because deep down , somehow he knew this all along. This was how existence was supposed to feel. The existential angst of youth probably came from knowing this, but not having much evidence for it.

T he thought of every animal around him bein g able to talk gave him stomach-churning anxiety. That they watched people, they knew things about him. Suddenly his privacy was gone. But Williem took three deep breaths, in through the nose, out through the mouth. He just told those anxieties to shut up (a neat trick h e had learned from meditation over the past few years). Instead, replaced those fears with more positive stories, such as; ‘Everything’s ok, nothing has really changed’, ‘the animals were always here, always communicating, but now I can understand them, that’s all’, ‘I’m a good person and I do my best, so it doesn’t matter if I don’t have that much privacy any more’, ‘…and maybe I’ll take that crows advice and shut the curtains when I want some alone time.’

Williem was glad he gave himself that little pep talk. It felt like a hop, skip, and a jump over what could have been a spiral into depression. One that a few years ago had the gravity well of a black hole. One so strong, that all it took was a light breeze to suck him in. These days that gargantuan celestial mass of power was more like the energy of an annoyed sloth. ‘Sorry sloth, talk to the hand, you can keep your depression and fatigue, I don’t want it, everything is ok, and I have stuff to be do’.

Full of this positive confident energy Williem started to explore the idea of what else all this could mean. The idea of telling his friends and family, getting them to believe him, what it could mean for scientific research and his career, he could become the world’s leading animal psychologist; he would become famous. Or should he even tell anyone?

All these thoughts came folding in all at once, like the 7 am opening of a shopping center on a Black Friday sale.

“I wouldn’t get carried away.” the crow said, as it could tell by Williem s facial expression that his cogs were whirring.

“W hat do you mean ?” Williem asked, somewhat worried that the animals could also read his thoughts.

“I can see you thinking about it, but a word of caution. If I know humans, as well as I think I do, they won’t take kindly to someone going around saying they can speak to animals.” The crow wisely offered up, then continued.

“A nd don’t think just because you can converse with any animal doesn’t mean it’s going to come in and do your laundry, like you’re some kind of Disney princess.” The crow went on.

“A word of warning, a hun gry tiger is not going to think twice about eating you, just because you can conversationally try to convince him not to. But hey , I might be wrong.”

This was a good point, as much as he hated to admit it. He had to calm his racing thoughts, something that being Bipolar had forced him to try and control. Just as there was a black

hole of depression on one side, the other side had a somewhat more tempting pull. That of mania. A roller coaster that got you so excited and got faster until you were sick everywhere. That balancing act used to be like walking a tightrope between the two. Now it’s more like a four-lane road bridge, a sturdy one that he can stroll down and enjoy the view. But still takes a moment of reflection to tell himself it wasn’t a good idea to jump off one side or the other.

No point getting ahead of himself. ‘This is all pretty new, no need to force life, it’s like a river flowing, what will happen will happen, and what will be will be ’, he thought to himself.

He felt g rateful to the crow, for giving him a moment of rational perspective, and not letting him get t oo excited about the unknown. This was exciting enough Williem thought. He had an inward chuckle at the whole scenario. The ups and downs he packed into the last five minu tes.

But that is not to take away from this moment of opportunity. Opportunity for discovery. After all its why he chose psychology in the first place. He always had an insatiable curiosity for life and loved to ask question s. To try and find answers, which mostly just led to more questions. But that’s why it was fun. ‘Could start now’ Williem thought.

“W hat.s your name?” Williem asked, as this seemed like a good to start.

“I’d thought you’d never ask, it’s Noam.”

“What like Noam Chomsky? D o you know who that is?”

“N ever heard of him, who’s that?”

Williem thought ‘This is getting weird er.’ It couldn’t just be a coincidence that he happens to meet a talking bird with the same name as one of the world’s most famous linguistic professors.

“W ell he’s… ”

“Sorry, I’ll stop you there. I have heard of him, and N oam ’s not my real name. I just liked that name and thought it would be fitting. My real name is Jack, I don’t like it”.

“O h… ok”, Williem spluttered. Somewhat relieved that the rabbit hole of weirdness wasn’t begin ning to spiral further. He was also somewhat threatened by the confident intellect of this animal. A natural instinct he had when he wasn’t sure if someone was being condescending. But that didn’t last long.

Williem always liked being the dumbest person in the room, that way he learn ed more. There was nothing to be insecure about, we all have our individual strengths and weakness. For all he knows every animal on the planet could therefore be more intelligent than every one of us humans. He was beginn ing to like this bird. He had a sort of jovial smarts that reminded him of himself.

“TELL HIM TO GET SOME OF THOSE SEED BALLS WITH THE FAT IN!” Y elled a voice from the tree. Williem looked up to see a cock necked, beady-eyed pigeon staring at him.

“Sourdough bread and dog biscuits!” Q uacked up from the river.

A crescendo of requests seem ed to rise from all around.

“Yes, yes, keep your undercoats on. Let’s not overwhelm the poor guy, he’ll end up going out and buying a rifle.”

The voices quietened to a murmu r.

“Whoa ok, well I’ll see what I can do, but I’m not made of money, I can’t suddenly feed all of you,” Williem responded.

“But can’t you lot live off the land like you’re supposed to?” Williem continued starting to worry that he was going to be emotionally blackmailed every day in to spending what little money he had on these greedy birds.

“In fairness, so could you ,” Jake replied, “w e have, what’s called verbal knowledge passed on from one another about how to live off what nature provides. Telling each other what we can and can’t eat. You could do that too, but for some reason, you only listen to the people who are selling food for profit. Doesn’t seem like a good system. But h aving said that, everyone here likes a high fat, high sugar content treat, so don’t stop feeding us leftovers, if that’s ok .”

It didn’t take long for them all to be driven by their stomachs and go find something to eat. After lunch Williem went for a walk down the river stopping by the field not far from where his boat was moored . Just off the tow path this particular field was occupied by a few cows. It was a bout an acre in size and had a gnarled tree in the middle. A path cut between the cow field and a section of woodland. Occasionally when using the path, the cows would give people quite a scare, particularly if they were in a bad mood. S wiftly throw ing their bodyweight in your general direction, just enough to remind you that a few pieces of wire – barbed as they may be- would be no match for a metric tonne of cow. Usually Williem stood by the fence on the river and watched them from a distance. Today they weren’t very far away. T o

Williem they were w ith in earshot, which before today he wouldn’t have known was a thing.

“Looks like that B738 is having to circle before landing. I think there must be heavy cross winds at the airport today,” one cow said to another in a slow chewy way that you would imagine a cow to talk.

“H OW DO YOU KNOW WHAT PLANE THAT IS ?” Williem yelled across the fence.

Somehow the cows looked at him sharply and slowly at the same time. The mild shock making them seem more d oe-eyed than usual. That might h ave been missed by someone else however, almost so soon as Williem could understand the wildlife around him the anim als instantly became more humanistic in their facial expressions.

“Excuse me, are you talking to us?” Said one of the cows.

“Sorry for the interruption , I just don’t know much about planes. I was interested in how you knew what it was doing ?” Williem enquired as politely as he would do when interrupting any stranger’s conversation.

“Well, it’s been circling… W ait, I’m interested in how you can understand me,” said the cow.

“Ah , I’m not really sure. I was admiring the countryside as I do most mornings, then inadvertently started talking to a crow. H e seemed to think it wasn’t that strange and he’d heard of such a thing before in ‘bird mythology’. I’ve only come across this in works of fiction myself. But the older I get, the more I realise that real life is stranger than fiction. T hat’s about as much as I know right now . ”

“Hmmmm ,” went the cow, in a very typical cow way.

This raised a question. H e’d heard cows make that noise before. Was this them thinking out loud every time? In the light of this new ability, he didn’t see why it wouldn’t be.

“Yes that rings a cow bell. I know the birds talk a lot. It’s hard to keep track of everything they witter on about, or what’s true. M ayvis, remember that time they told us about the giant stone trian gles?” one cow asked the other.

“That’s right, in Egypt, p yram ids I think, wasn’t there something else interesting about that?” said the other cow.

“Ah yes, well anyway, it’s a big world lots of things going on. A person understanding us, that’s new. But probably no more improbable than some of the other things we’ve heard,” said the cow.

Williem was surprised by the cows calm o pen -minded acceptance.

“W ell, its nice to meet you . I’m Bessy and this is M ayvis.”

“Nice to meet you too, my name’s Williem . S o, do you talk to the birds? D id they tell you what that plane was?”

“Y es they’re a good source of information. T here’s not much to do in this field other than eat and do a bit of plane spotting. You start to pick up patterns living near an airport, and if you don’t know something it helps to ask the birds for specifics, they’re quite knowledgeable. Y ou can hear them now, that stream of twittering in the backgrou nd.”

“Yes I suppose, It’s hard to tell what they’re all on about. T here’s a lot of noise and it’s pretty quick,” Williem replied, squinting one eye and looking up to trees.

“Of course. A ll the birds are talking to each other, talking to the rabbits, the deer, everyone. I tap in and have a listen when I’m bored. I also have a number a friends I enjoy talking to when they visit.”

“Before yesterday I thought all that bird song was just them calling out for a mate, or about food, or warning each other about predators. It sounded too tuneful to have any complex information,” Williem said shyly.

“B ut isn’t that exactly what you humans do? You make sounds with your mouths ? You can convey a lot of information with sound. Even if it was just about food , sex, or death, I’d say that’s pretty complex information ,” Bessy said, as if all of this was straightforward.

It was sinking in that Williem had been out of the loop up until now. As if he gone to a party, happening in a small room . Then someone opens a door and says ‘well of course the party wasn’t just going to be in this hallway, there’s the whole rest of the house !’

“Makes sense I suppose. I guess I’ve never really give n it much thought.”

Bessy slowly chewed on some grass and added, “Y ou humans seem so preoccupied. We just thought you had some kind of ‘other species deafness’, or perhaps we all have a bit more brain space for communication than you do.”

Williem wiggled his finger in his ear, “I do feel like I’ve just removed two wads of cotton wool from my ears and brain . It’s like I have this extra sense, as if I can see behind the curtain and have found all this communicating going on,” Williem said gratefully.

“The way I see it, it’s not much different from that internet thing you have on those phones of yours. W e have our own stream of information in the airways, the birds.”

“W ow , ok. Y es, that’s quite interesting when you put it like that. Also a natural one at that,” Williem replied as he pieced together the analogy.

“I suppose,” Mayvis mooed. “B ut this internet of yours is natural too, is it not?”

“Well, we had to build it. So not that natural. Y our bird network seems more organic,” Williem said, scratching his head, wondering if that made sense.

Bessy interjected and focused on Mayvis, “One could make an argument that there is a separation between natural behaviours and the unnatural construction of things.”

“True, but you could say that a bird who turns sticks into a nest is constructing something t hat wasn’t there before. Would you say that was unnatural?” replied Mayvis. Williem was starting to feel a bit left out.

“Fair point,” said Bessy, still chewing.

“The two of you are quite philosophical,” said Williem trying to jump back in.

“Like I said, there’s not much to do in a field other than eat and talk.”

“Sorry about that. A re you ok? Do you want me to try and free you somehow?” Williem suggested awkwardly, having the realisation that they were in a kind of prison.

“Oh please don’t, have you not been listening? E ating and chatting; its not a terrible existence,” said Bessy.

Surprised by this Williem questioned, “So you don’t mind being cooped up in this field? D on’t you have to instinctual urge to migrate, roam the countryside and be free?”

“Not so much. F reedom, doesn’t sound so good. Could you imagine? The constant worry ing about wolves, bears, droughts, starvation. Sounds stressful. No, we have it pretty comfortable here. And as far as I can tell, its been a long time since us cattle were wild animals. Put it this way, I have as much urge for freedom as you probably have the urge to sit naked in a tree.”

“I see your point. I always just assumed it w as cruel to keep you fenced in like this.” Williem didn’t feel the need to mention that the idea of sitting naked in a tree actually appealed to him.

He did feel the need to ask another deep question . “I’m assuming you know what a farm does? I mean… I should probably tell you that I eat meat, not a lot, mind you.” Williem wanted to divulge this information before they went any further.

“It’s up to you how you live your life. I do hear that we are quite delicious, so you’re welcome,” Bessy said as they both gave a snort and a chuckle.

Williem wasn’t sure if he should be uncomfortable or not.

“Oh ok. So you don’t mind that you’re being kept to eventually be eaten?” Williem asked empathetically.

“Not really, it is what it is. Worms are going to eat you eventually; do you mind?”

“Well no, but I’d probably have something to say if I knew that one day they were going to take me away and murder me, in order to do so,” said Williem.

“Firstly , how do you know they won ’t? Secondly, if they did you wouldn’t say anything because you’d be dead.”

“I guess,” Williem reluctantly agreed. “B ut side note… I’m finding out a lot of new information today. S hould I be worried about the worms?” Williem question ed, half joking.

“N o, I’m just saying, when you’re dead, you’re dead. If something wants to eat me when I am , fair enough. If someone wants to euthanise me before I get old and sick, fine. Is it ideal? Who’s to say, but it is what it is. At least in exchange I get a pretty comfortable lifestyle.”

Mayvis interjected and turned to Bessy, “That reminds me, the vet’s coming next week to do our health check up .”

“Oh fun! I like Sally, she gets in a laughing fit when I chew her smock. It does amuse me,” said Bessy.

Bessy turn ed her attention back towards Williem, “Are you much freer? I assume you’re tied to some place of work and a house.”

“I’m not sure that’s the same. I’m not being kept captive for food,” Williem exclaimed.

Mayvis gave Bessy a look like she was talking nonsense, “He’s right, of course it’s not the same, he’s free to travel around at will.”

‘That’s right,’ Williem thought. He then tried to rem em ber the last time he actually went anywhere. But his point was he could if he had the money.

“Fair enough,” Bessy conceded. “I suppose I tend to concentrate on the things in my life that I can control, rather than worry about the things I can’t. Not to mention that we’ve heard stories of cruel farmers, and horrible conditions; it gives me the chills. So things could always be worse. ”

Williem thought he could learn a lot from these cows. Perhaps the H indus were right, this was a sacred animal. It was still going to be hard not to eat them . T hinking about his meat eating habits, h e said to himself, ‘I should really abstain from picking up a steak in the supermarket now I’ve had philosophical discussion with one. But it’ll still be hard to say no when someone hands me a juicy beef burger at a BBQ . Especially since I basically just got permission from a cow to do so.’

“Try to keep your voice down though Bessy, Darsee will hear you from the barn,” Mayvis whispered.

“Oh yes. Darsee doesn’t share my philosophy on the acceptance of one’s situation . I try not to bring it up around her, we just end up talking round in circles. Not that I judge her view point. But I keep saying that unless she can do something about it, all it will do is cause her stress. It won ’t do her any good . It’ll just make her meat tough,” Bessy said with a wry smile.

W illiem was finding it difficult to focus on his work. After an hour or so of trying, all he could think about w ere the day’s events. Did that really happen ? O r was it a glitch in the matrix? He wasn’t a stranger to questioning his own perception. Being bipolar he was used to being subjected to periods of depression and agoraphobia. Time spent ridden with anxiety and a negative s elf-perspective. Inevitably he would improve, sometimes as if a light switch had been flicked on. H is fatigue retreated, food tasted better, and his concept of the future returned. He ha d to ask himself questions such as, ‘Why was I thin king that way?’, ‘Did that week really happen?’, and ‘Was that perception based in any truth?’ Once he had regained his strength , the only sensible way to answer those questions was to take a shower, put on

some clean clothes, get out into the world, and gather some data.

Questions like those tap-danced in his mind distracting him from the proofreading that he was supposed to be doing. The only thing to do was to accept that sometimes, trying to do something while preoccupied with something else, was a futile exercise. Therefore, h e made a cup of tea, climbed out the side hatch of his boat, and sat on the roof.

The birds were in full sing. It was difficult to make out what they were singing about, even though he could hear it in English. Singing wasn’t exactly the best way to describe it. More like a plethora of conversations all happening at once, sped up and at a higher pitch.

He was able to pick out words, but by the time his brain caught up, the topic of conversation had moved on to something else. It didn’t help that most of these birds were hidden from view . Either flying about or hidden in the trees. Who knew which bird was talking to which ? But it had a song-like quality . A kind of folk music; beautiful sound ing and lyrically full of information. Unfortunately, it seemed to Williem , to be playing at 250 beats per minute. Which was too fast to digest what that information was.

Whilst Williem was trying to listen , he was becoming more aware of the dynamics in range, tone, notes, and even the content of what wa s being said. He found it interestin g that when the birds talked to each other it sounded more like singing than when he was talking to the Jake the crow directly. Jake had a cadence that matched his own. ‘This was not unusual,’ W illiem thought. Thinking about how people would vary the way they communicate d with one another, depending on whom they were talking to. You might match

an other person’s energy or speed. A good example is when communicating with someone who doesn’t speak the same language as you. Y ou find an equilibrium that might consist of hand gestures, mimes, and facial expressions. You can get quite far with a Rosetta stone baseline of ‘yes I understand ’ , or ‘no I don’t understand’. Much like how people communicate n on -verbally when they play music al instruments together. You try to find an equilibrium by matching tempo, key, chords. Any number of things, in a variety of interesting ways to communicate something. Even if all you’re trying to communicate is how much you are enjoying communicating to each other. Similar to having a silly conversation with your friends for no other reason than it’s a good laugh.

Williem enjoyed playing some music in his spare time. He found it therapeutic, particularly since he wasn’t very good. Having no pressure on him to be good, is what made it therapeutic. Ironically, as the universe likes to be sometimes, h e noticed a quicker learning curve without a pressure to be any good. Maybe it was just a sign of getting older, that he was managing to shed some of that youthful poisoned chalice called perfectionism.

The psychology of music was something that had peeked William ’s interest. After hearing the symphonic dialogue of birds talking, Williem pondered on what made speech , speech and song, song. He recalled the “speech -to-song illusion ” from his psychology studies. A fascinating illusion in which a repeated spoken sentence would transform in the mind into singing. As if like magic, your brain adds an intangible musical quality after a couple of loops. Williem had only spent a bit of time reading around this subject, specifically the work of neurologist Oliver Sacks . However, this experience of listening to the birds sing/talk gave him an extra dimension to

his understanding that went beyond the purely academic. Williem couldn’t help but think of the thought experiment about Mary’s Room. In which Mary is a scientist in a black and white room. She knows everything there is to know about colour. One day she leaves the black and white room and sees colour for the first time. Is she learning anything new? It’s a good way to think about the difference between knowledge and experience; the epistemological and the phenomenological.

Whilst his mind wondered, Williem greeted the ducks. They passed by on the watery conveyer belt in front of him . “Hello, duckies…” Williem said with a smile. They mostly ignored him. They weren’t saying much to each other either. Some talk of where they had been and where they were heading next. But mostly they were in eating mode. It had rain ed the night before after a particularly sunny spell and the river had a healthy flow . T he duckweed was in abundance, as if luminous green confetti had exploded over the water and was slowly riding the current down stream. T he ducks franticly darted back and forth hoovering it into their gullet. Making sure not to miss the weed collecting on the side of W illiem ’s boat. They made a rhythmic fluttering of bills on the metal as they ate. No sooner had they appeared, they followed the flow of the river and were gone. No time to talk, but nobody likes h aving their dinner interrupted .

Williem caught sight a bird collecting twigs on the opposite bank. It was flying back and forth over the river, over his boat and into a tree behind him. A small bird, some kind of tit. Williem was terrible with names of species, unless it was something memorable or distinct. It also didn’t matter how old he got, he couldn’t help but smirk when calling a bird a tit. Not because tits were slang for breasts, but becaus e where he grew up calling someone a tit was a colloquialism for someone behaving stupidly. He always thought this to be rather unfair on the poor birds who shared the same name. But it did have funny and satisfying double T sound, much like another double T sounding insult word.

After w atch ing the bird make several trips , Williem got up and approached the tree in the hope he could see a nest being built. Peering into the foliage he could see a very aesthetically pleasing bird’s nest, and two birds. They were focused on the ir creation , moving around it at such speed that it seemed more like teleporting, than it did flying . N ot much

bigger than golf balls, with their heads switching from side to side to assess their work. One of the birds plucked a twig from the nest and discarded it to the ground. It did so w ith the speed and precision of an expert sewer who could thread a needle without even looking.

“W hat was wrong with that one?” Williem asked.

“Oh , hello… you must be the young man that Jake was talking to this morning,” the bird replied.

“I suppose I am . M y name’s Williem. Williem with an e.” He often slipped unconsciously into saying that. It was a force of habit.

“Nice to meet you William Wythanee. M y name’s Fable and this is my partner, Letterhead . ”

“No sorry, I meant; Williem spelt with an e. My surname is Wu,” said W illiem hoping it didn’t sound condescending to point out spelling to a species that didn’t write.

“Of course, I was just plucking your win g.”

Williem, was noticing a trend. He let that one go. He decided has wasn’t going to have many interesting conversations if he spent all his time correcting their idioms.

“Ah ok… T alking of names, Letterhead is an unusual name. W here did it come from?” h e asked.

“It might be unusual to you,” the bird said sweetly . “…H aving said that, I don’t think I’ve met another Letterhead. H ave you Fabel?”

After a micro bird pause to think, Fabel replied, “I can’t say I have.”

“So perhaps it is uncommon, but I believe it comes from what you call the head of a letter. W hich I do not believe is unusual. Isn’t that right, Fabel?”

“Yes, I do believe it is,” Fabel agreed.

There was a charming innocence to their manner. Williem thought about how in another tone that would have come across as stand-offish. But this felt like a genuine response. Letterhead and Fabel had an up-tempo call and response in the way they communicated. He wondered if this was just how all birds talked. Maybe he been too quick in anthropomorphising Jake when he thought he was giving him sass, or being sarcastic. H ad he fallen prey to stereotyping based on looks? T he midnight black, sharp beak, and razor talons did give William a mild uneasy feeling. He was glad crows weren’t the size of Labradors. Perhaps he had judged a book by its cover. Pe rhaps Jake was just as sincere as these two. But because Fabel and Letterhead were smaller and more decorative they came across like a sweet couple in their 80’s. A mild mannered couple that happen to have the physicality of a six-year-old hopped up on sugar. Of course, it could be that species has nothing to do with it. Just like humans there’s going to be individual differences in personality. So, perhaps Jake was giving him sass, and perhaps these birds weren’t.

Williem did, at times, find it hard to communicate with people. Not knowing if they were being purposefully condescending . He blamed the political commentators, Gore V idal and William F Buckley, and the four decades that

proceeded them. The combative opinions and insults between intellectuals that had dominated the western media. He knew people in real life rarely talked to each other like that. Still, his own insecurities made him a little defensive . Nonetheless, he tried never to let those insecurities get in the way of a good conversation.

Now the world had miraculously opened up an ability to connect with other minds. ‘Life was anything but dull,’ he thought to himself. It would be an interestin g road ahead. O ne paved with n avigating the nuance of conversation, understanding different humour, an awareness of the errors in translation, and the careful consideration to not stereotype. Just because to Williem , two animals of the same species might look indistinguishable from one another, it doesn’t mean they will communicate the same way. This road was similar to the first 30 years of his life, learning how to communicate with people. ‘This is going to be fun,’ thought Williem.

“W hy did you throw that twig away, if you don’t mind me asking?” Williem repeated the birds.

“Oh , well it just wasn’t right. S ometimes you see the perfect twig, sometimes you wont be sure if it’ll be right until you try it. Sometimes you try and place it in a few ways until it works. Other times you just know it’s not the right twig. This was one of those times. Is that not how your home is made?” Letterhead answered.

“Well not really. I’m sure my boat was plan ned and designed before construction, then put together with specific materials.”

“I supposed that seems sensible. The division of labour, it’s a helpful thing. Also make s sense to put those opposable thumbs to good use. W e’ve seen such a variety of interesting things humans have built. Its very impressive,” said Fable.

“Thanks. I do like that about people; their ingenuity and creativity. People build and create all sorts of things. U nfortunately , that also comes with a lot of problems. People like to argue and compete, so anything new created is liked by some and not by others. We like to think that we work on the principle of majority deciding, or at least that’s the ideal. It’s kind of the basis of the whole democracy thing. People vote with their words, their money, their time. I’m not smart enough to know if that’s the best way to do things. All I can say is that it works, when it works,” Williem said, trying to offer some brief explanation as to why humans do the things they do.

“Fascinating. Seems complicated. I suppose you could say that I try not to overcomplicate life. We needed some w here to nest our young. Here seems a good place. Then we used the tried and tested method of constructing with twigs and found objects. By using the natural quality of the materials it creates an insulated , lightweight, self-supporting structure. I

don’t give it too much thought. But, to get back to your original question, I just know, in that moment the twig was not right. We add one rig ht twig at a time until the whole nest feels right. I guess you could say I’m acting on instinct,” Fabel replied.

“Funny, w hen you explained to me how you build your nest, it sounded a lot like how I approach a piece of artwork. I’m always quoting Leonardo da Vinci by saying that ‘art is never finished, only abandoned’, and Thomas Sowell who said that ‘There are no solutions; there are only trade-offs’. I find art and music to be a lot like that. I like to paint and w hen I do I’m constantly making trade offs about little decisions about what mark to put where. Eventually you make enough good marks until you can stand back and say, ‘Ah yes, that’s right!’ O r at the least that’s as right as I can make it. I don’t always know why it’s right. A lot of the time it just feels instinctual. You’ll never get an exact copy of what’s in your head, but depending on the materials, and level of skill you can get pretty close. Sometimes the specifics of the materials can dictate what’s in your head. I imagine that might be like building your nest. You’ll have a n ideal nest in mind, but what emerges is a combination of that and the materials you find,” said Williem.

Without hesitation Letterhead added, “Yes indeed, it is a relationship between you and something that you are creating together. You see, when you explained to me how you approached making art, I felt like you were describing love. That is how I feel about Fabel. I have an ideal in my mind about a mate. I fell in love with him right away. Not because he w as a 1-2-1 representation of that ideal. But because I just knew instinctually he was right. I trust the processes enough to let myself swoop in love with him , based on that.”

“That is a nice thing to say , Letterhead,” said Fabel. T hen continued, “Of course , I can’t possibly know exactly what’s in another’s mind. B ut I certainly agree with that statement and feel the same. W e create together, this nest, the relationship we built. W e have a division of labour and w e create life in a way that is positive for both of us. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not always sunshine and mealworms. W e’ve had our share of hard winters. Which is why we usually join a flock in the winter, for strength in numbers. But it’s why we have each other’s back and love each other.”

“Wow , that’s interesting. I’ve not heard someone describe love like that before. I have to admit that when I have created a piece of artwork I’m really happy with, I do feel love for it. I appreciate the fondness for something you have made yourself; in psychology we call that the Ikea effect. I have also always wondered that about physical attraction. When you see someon e and you love the way they look. But why is it that you can fall in love at first sight? W hy is it that two people can superficially look the same, one might not elicit any response, whereas the other you might fall in love with?

T here seems to be some debate about that. Some argue that we are programmed by cul ture and things we are exposed to, w hich determin es what we are attracted to . Having stud ied psychology, my personal belief is that we are programmed by both nature and nurture. Since there are about 100,000 genes, and if you multiple that by the many more ways some can experience life. Then that math is too big to calculate a nd identify a causal relationship to a specific factor that tells you

w hy I’m attracted to one person over another. You’ll only have a spurious correlation at best. … Having said that, I have noticed a trend in my ow n personal life. I seem to have an attention for French and Middle Eastern women. Particularly ones with big eyes and flawless skin. So I don’t if that was in my genes, but the women look suspiciously like the Disney

princesses from my childhood. Who knows if I’ve got Disney to blame for programming my unrealistic expectations of female beauty. Or w hether Disney used those representations of female beauty because they are instinctual. A chicken or egg situation , you know?”

“No, sorry, I don’t know any chickens named Disney,” said Fabel unironically.

T he day was drawing its curtains and coming to a close. The air was still and the sunshine bled out into a tangerine twilight. Williem watched this from the roof of his boat. He proceeded to meditate in an attempt to calm his mind. Repeating his mantra and focusing on his breath. His consciousness slipped into a velvety black pool of nothingness. Like soaking sore muscles in the bath after a long day, it cleansed his soul.

H e then reflected on days’ events. A fundamental shift had occurred. He knew those moments happened in life. Williem just assumed a shift like that would come from the birth of his first child, or the death of a loved one. This was not on his radar, but it was usually the unusual that shocks the system. When something unexpected did happen, particularly if it was

a good thing, Williem just chalked it up the wonders of the universe. Times like these he remembered a quote from Oscar Wilde who said , "Life imitates art far more than art imitates life". This certainly rang true today.

The concept of truth made Williem reflect on his psychology studies. Something he tried to live his life by Baye’s Theorem. Thomas Bayes was a statistician who developed a mathematical formula, one th at helped update the probability of a hypothesis based on new information. An equation that used prior information and likelihood to determine the probability that an event would occur, after taking into account new evidence. Williem liked to describe the human mind as a ‘best guess machine’. Not that we didn’t use logic to systematically and rationally solve puzzles or challenges, following rules and drawing valid conclusions. But most of the time life had too many variables to draw a conclusion that gave you a fundamental truth. All a person could do was estimate a probability of how true something might be . It didn’t matter if you were questioning whether the theory of evolution was true, if the world was flat, whether god existed, if aliens were out there, or whether we live in a simulation or not. All a person can do is use the evidence available to them to make a best guess about the degree of truth. The same goes for questions like, ‘is chocolate bad for me?’, ‘should I buy this car?’, or ‘will I embarrass myself by telling this joke?’ Nothing is certain , however in Williem ’s case it was close to certain that he would embarrass himself when telling a joke. You couldn’t say for sure that letting go of a ball would have it fall to the ground. Only that given the evidence of prior examples, you might say it was very likely. It felt freeing to loosen the concept of a binary ‘true or false’, and instead looking at things as degrees on a scale. Particularly in a world where everyone wanted you to convert to their truth.

Whilst Williem was in a calm state, something was still niggling at him. He was weighing the probability that he was mentally ill. Was this schizophrenia? There was still no clear evidence to suggest this was really happening. Was he just suffering from psychosis? Knowing what he knew , there was a high likelihood that his brain was inventing these conversations. He took solace in the fact he was still compos mentis enough to question his own mental state. Thankfully, either way if it was a symptom of a mental disorder, or whether he had miraculously developed a skill that only existed, to his knowledge, in fiction, that it might not actually matter. After all, something should only be classified as a disorder or illness, or disability if it negatively impacts a person’s life, causes them pain, suffering, dysfunction and an unfair handicap when it comes to living a reasonably selfsufficient life. So if he was schizophrenic then hearing animals talking, if navigated properly, didn’t have to result in any of those things. And returning to doctors to get some support would help. Of course there may be a chance he wasn’t ‘ill’. Having spent the last few years practicing meditation and the art of ‘doing little to force life’ might have opened this new door in reality. What he needed was more data. More data would help update his knowledge and should give him some insight into how to proceed. He needed external validation for what was happening.

Williem asked himself, ‘How can I run an experiment? How do I test something that is only happening to me?’ The animals looked is if they were engaging in conversation, even if he couldn’t read their lips. He needed some other visual confirmation.

That was it, Jake could read!

“Jake! Hello! Are you up there? I was hoping was you might be able to help me with something, when you have a moment,” Williem called out to the trees.

A few squawks darted around his peripheries. After a moment, a gust of wind and a fluttering of black came swooping down and landed on his roof.

“Jake?” Williem asked

“That’s me, bu t I guess you’ll have to take my word for it, since you obviously can’t tell us crows apart. R acist.” Jake clacked. Williem thought he could see Jake give him a cheeky wink, but his eyes were to o small to know for sure. ‘That sounded like Jake though,’ he thought.

“Come on! It’s been a long day! Give me time.”

“Only pulling your wing. What’s up?”

“I was hoping you could do me a favour? Did you say you could read?”

“I hoping you’re not going to make a habit of this. I’m not a genie you can summon,” said Jake with an inflection that sounded like he actually enjoyed the attention. “Yes, I can read, somewhat. I’m sure this reading/writing thing serves some purpose, but do you humans have such bad memories that you need to w rite everything down?” Jake asked.

“I can’t speak for other people, but yes, my memory isn’t great. To be fair, neith er is my writing. However, being able

to write is quite helpful. If you’re having a conversation with someone you can tell if they understand you. You have more tools such as body language and gestures. Syntax and grammar aren’t as important when the person is right in front of you. It’s hard enough to transport what’s in your head to someone else’s when they are in the room. However, if you wan t to communicate something to someone who isn’t there, then it’s like a fun game trying to work out how to convey that information by using symbols written on paper,” said Williem.

“Sounds like in interesting puzzle. Each to their own I suppose, but I think I’ll stick to having wings and flying.”

Williem couldn’t disagree, as much as he loved to read and write, the idea of flying in the sky sounded idyllic, a concept that if he wasn’t already engaged in what he was doing he would have been happy to delve into a long conversation with Jake about it.

“Anyway. I have this pile of sticks. What I was thinking was, if I close my eyes, could you arrange them into a number, perhaps a number between 1 and 10 and call out what you have written? Do you think you could do that for me?”

“I don’t see why not, b ut what’s this all about? A re you ok?” Jake asked.

“I’m ok, thank you. I’m just trying to get a fix on what’s real and what’s not. I figured that if I hear you say a number and I open my eyes and that number is there in front of me, then that would be at least some additional evidence as to whether I’m crazy or not.”

“Fair enough , if puts your mind at rest. Of course I’m tempted into not doing anything and let you think you’re going crazy. But that does seem mean. After all, having you here might be helpful, know ing that if I get hungry I can always come and ask you for some food. Talking of which have you got any bacon…or walnut cake? ” said Jake.

“Hmm, I’ll have trust that you ’ll listen to your stomach over your mischievousness. I’m sure I’ve got something in the fridge, I’ll have a look in a minuet. Ok then, h ere we go. I’m shutting my eyes.”

William shut his eyes with a mild flutter in his stomach. He asked his body to try and to settle it, after all the outcome wasn’t a big deal, but it was hard to mentally change a physical sensation in the body. A few moments went by.

“Ok, so I’ve made the number five when you’re ready you can open your eyes,” said Jake.

It had already occurred to Williem that if he was experiencing an auditory hallucination, then it wasn’t outside the realm of possibility that he was also having a visual hallucination. What he really he needed was verification from another person. But one thing at a time, this could be done here and now. He wanted to be a scientist, and he knew that a good scientist didn’t draw many conclusions from one experiment. Either way this will add some data to his best guess brain machine. Plenty more experiments can be done after this.

‘Here we go,’ Williem thought.

He counted down.

“Ready in 3...2… 1…”