6 minute read

12 Two Wings of a Small Altar with Scenes of the Life of Christ

from JB Test 01/22

Fig. 1. Israhel van Meckenem, Ecce Homo, copperplate engraving, c. 20.9 x 14.5 cm Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. no. RP-P-OB-1107 Bitte Fig. 1 download: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/ collection/RP-P-OB-1107

Fig. 2. Master of the Kalkar Death of the Virgin Mary, c. 1460/1470, oil on panel, 88 x 70 cm, parish church of St. Nikolai in Kalkar

Advertisement

12

Fig. 3. Master of the Kalkar Death of the Virgin Mary, Detail, Apostle at the foot of the deathbed

Stylistically there are similarities between this work and that of the Westphalian painter Derick Baegert. Baegert also worked with great attention to detail and is reputed to have had Italian silk brocade as a reference in his workshop . Parallels can also be drawn to the so-called Master of the Kalkar Death of the Virgin Mary (panel painting in Sankt Nicolai in Kalkar, fig. 2). If one compares the face of James the Apostle, seated at the foot of the bed (fig. 3), with that of St. Anthony, stylistic similarities can be found in the facial features. The anonymous Master of the Kalkar Death of the Virgin Mary was probably active in Wesel. Today, he is thought to have taught Derik Baegert, the most important artist of the late 15th century in Westphalia and the Lower Rhine.

Due to the stylistic proximity to Derick Baegert, it is assumed that the artist of our two panels and Baegert were students of the Master of the Kalkar Death of the Virgin Mary. It is equally conceivable that he worked together with the workshop of Derick Baegert.

transition period from late Gothic to the Renaissance, created works largely of religious subjects. His customers included the Church and wealthy citizens. His first, prominent commissions that could be seen by the general public, primarily altarpieces and crucifixion groups, founded his artistic reputation and helped him establish a flourishing workshop in Würzburg.

13

Trotting Horse

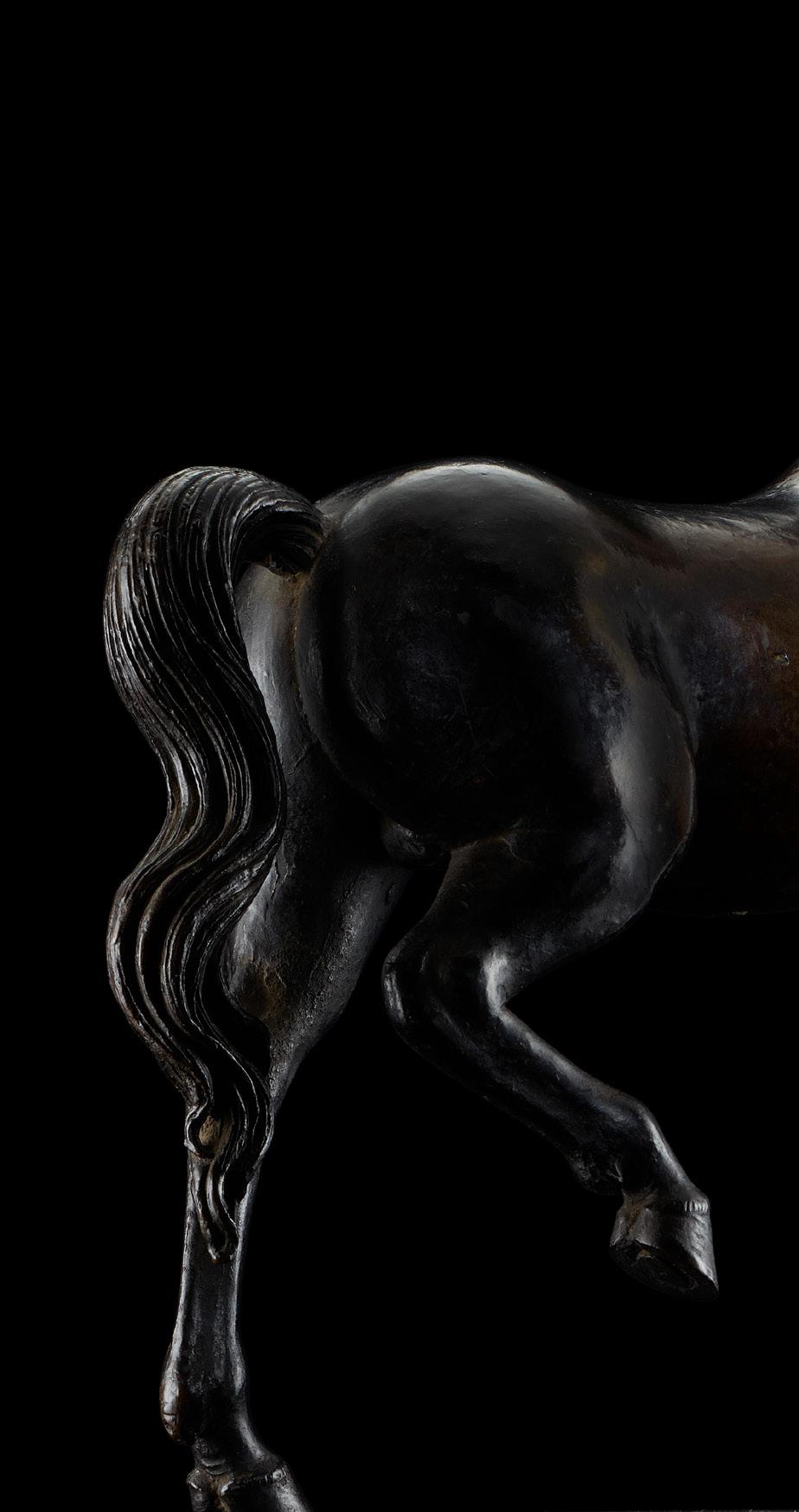

TROTTING HORSE

Italian (Florence or Milan) Circa 1500

Bronze, direct unique cast Height 27.8, length 31.5 cm

Provenance: Marczell Nemes Collection, acquired at auction at Mensing, Amsterdam, 13–14 November 1928, lot no. 113 (as being by a ‘Milanese Master’) for 7140 Reichsmarks by Heinrich Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon; thereafter through the family until 2006

The horse was produced using the direct casting method with which a figure is modelled in wax directly on a so-called casting core. An outer casting mould, a so-called investment, is then placed over the wax and held in place by core pins. This is followed by the firing process during which the wax runs out. Afterwards, bronze is poured into the hollow form created. The direct casting method has certain characteristics such as somewhat more solid walls of slightly varying thicknesses. In the case of our horse sculpture, an original, corrected and barely visible casting error has been identified behind the right ear. This was probably where a large part of the casting core was removed. No other corrections are discernible.

Indicative of the anonymous artist’s great talent are the outstanding, individual modelling of the mane and tail as well as the unusually realistic depiction of the hooves. In addition, the whole body has a delicately hammered surface structure. As the design, skilled production and artistic quality of this horse are exquisite it must have been created in the workshop or in the vicinity of one of the great Renaissance masters. In the Renaissance there were only a few statues of mounted riders or horses considered as prototypes. These include the Quadriga, comprising four gilded bronze horses, taken from Constantinople in 1204 for St. Mark’s in Venice and the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome dating from Antiquity. In 1453 Donatello completed his bronze equestrian statue of the mercenary leader Gattamelata and, up until his death in 1488, Andrea del Verrochio had been working for ten years on a memorial to the condottiero Bartolomeo Colleoni. This was first completed and cast in 1496 by another sculptor, Alessandro Leopardi. All of these equestrian figures, however, stand on three legs, not least of all to provide stability. What makes our horse so special is its elegant stride, with a diametrically opposed rear and front leg raised at the same time.

The movement of this step is reminiscent of the so-called piaffe in dressage that was already being taught in the Renaissance. The ‘Regisole’ (Sun King) monument in Pavia, that also dated from Antiquity but was destroyed in 1796, was probably the only one also showing two legs raised simultaneously. In looking for an artist who could have manufactured our bronze, one soon arrives at the circle of Leonardo da Vinci. Throughout his life Leonardo was preoccupied with creating the most anatomically precise depiction of a horse possible and made numerous sketches and designs of horses in various positions and gaits. The bronze cast for an equestrian statue to honour Francesco Sforza in Milan, in particular, for which Sforza’s sons sought an appropriate master of his craft after 1473, was a challenge to the universal genius.

In 1482 Leonardo writes to Lodovico Sforza in Milan offering his services as an architect of fortresses but also mentions the ‘bronze horse’: “... to [mark] the immortal glory and in eternal honour of your father as well as of the virtuous House of Sforza.” (Codex Atlanticus, folio 391r-a, cited in: Ladislao Reti (ed.), Leonardo. Künstler, Forscher, Magier, Frankfurt a. M., 1974, p. 88). Leonardo is called to the court and remains there for sixteen years.

13

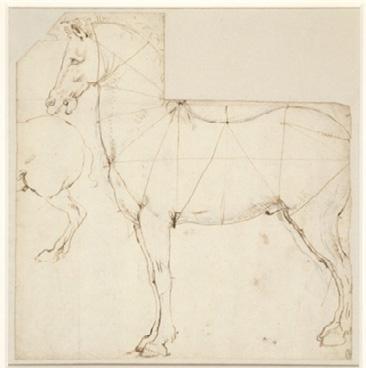

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) A horse in profile divided by lines, pen and ink over black chalk, c. 1480. Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) A horse in left profile with measure-ments, c. 1490 both Royal Collection Trust, © HM Queen Elisabeth II 2016

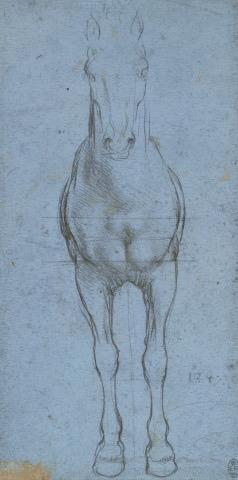

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) Studies for an equestrian monument, pen and ink over black chalk, c. 1517 – 18. Recto: a study of a horse, moving in profile to the right, and two studies of horses moving to the right, seen in three- quarter view from the rear. Verso: a study of a horse in profile to the left, and an equestrian figure riding in profile to the right, his right arm outstretched behind, and a fluttering cloak. c. 1517 – 18, Royal Collection Trust, © HM Queen Elisabeth II 2016.

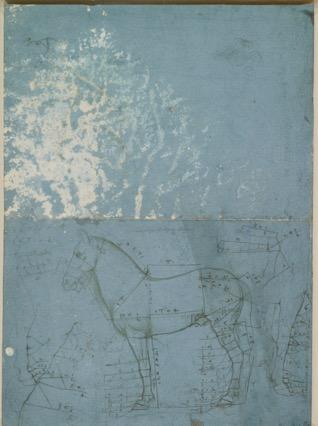

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) A quick study for a horse walking in profile to the left, pen and ink, c. 1490. Fragment from the Codex Atlanticus, 147 recto-b; Royal Collection Trust, © HM Queen Elisabeth II 2016 Leonardo da Vinci, (1452 – 1519) A Horse divided by lines, metalpoint on blue paper, c. 1490

Leonardo da Vinci, (1452 – 1519) A horse in profile and from the front, c. 1490, metal- point on blue paper, both Royal Collection Trust, © HM Queen Elisabeth II 2016