3 minute read

21 Christ Crucified, attributed to Georg Petel

from JB Test 01/22

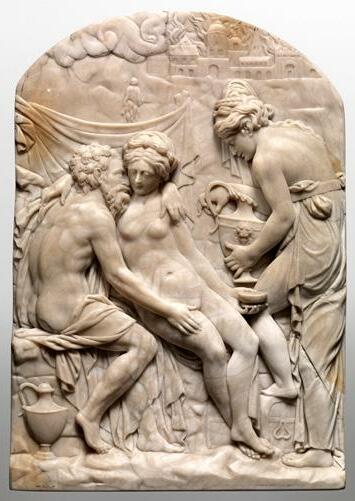

RELIEF WITH LOT AND HIS DAUGHTERS

Advertisement

DANIEL NEUBERGER THE YOUNGER Augsburg, 1621-1674/81, attributed to

Mid 17th century

Polychrome wax relief with partial gilding Height: 41.8 cm, width: 32.5 cm Within the original frame, height: 62 cm, width: 52 cm

Literature: Lipinska, Aleksandra. Moving Sculptures: Southern Netherlandish Alabasters from the 16th to 17th centuries in Central and Northern Europe, Leiden 2015, pp. 259-60, fig. 184. McGrath, Maeve. Daniel Neuberger the Younger and Anna Felicitas Neuberger. The Ciroplastic Œuvres 1621-1680 and 1650-1731, Regensburg 2016, p. 82, fig. 24 and pp. 164-66, no. 6.

Related literature: Lessmann, Johanna and König-Lein, Susanne. Wachsarbeiten des 16. bis 20. Jahrhunderts, Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum Braunschweig, Sammlungskatalog Band IX, Braunschweig 2002. The scene is erotically laden: two scantily clad young women have a rendezvous with an elderly man. One is holding a jug filled with wine; the other places her arm around the old figure who is obviously already drunk, as he approaches her with a lecherous look in his eye. The beauty, with a gossamer cloth draped over her thigh and arm that wraps around her body like a snake, has a Venus-like appearance – not only to the man at her side but, and in particular, to the viewer of this skillfully worked relief. The other female figure, also dressed like a goddess from Antiquity, is depicted in profile. She reveals her sensuously bared back, arm and shoulder as well as her right leg.

What is actually shown here, however, is the story of Lot as described in the Book of Genesis, chapter 19:30-38. Lot has fled the lost city of Sodom together with his wife and his two daughters. During the escape from Sodom, Lot‘s wife turns into a pillar of salt. Lot and his daughters take shelter in Zoar, but afterwards go up into the mountains to live in a cave. One evening, Lot‘s eldest daughter gets Lot drunk and has sex with him without his knowledge. The following night, the younger daughter does the same. They both become pregnant; the older daughter gives birth to Moab, while the younger daughter gives birth to Ammon.

Lot’s daughters see things pragmatically. As the only female survivors of the catastrophe, the destruction of Sodom, they are afraid that they are the last in the human race. In their desperation they decide to weaken their father’s will by plying him with wine before having intercourse with his own offspring.

22

1 Lessmann, op. cit., p. 12. 2 Lipinska, op. cit., pp. 257ff., esp. p. 259. 3 Ibid. p. 18 and p. 259, fig. 183 and p. 260 notes 31+32.

Fig. 1. Lot and his Daughters, alabaster relief, South-Netherlandish or German, circa 1560, 42.2 x 29.2 cm, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig (Brunswick), inv. no. Ste 27

22

During the Counter-Reformation, Lot’s relationship to his daughters, born of pragmatism and desperation, is interpreted moralistically. Both the act of incest with the father as well as intercourse without mutual consent with someone intentionally made drunk are taken as being symptomatic of the Catholic Church’s immoral behaviour: luxury items such as jewellery and the valuable jug underline this scene which, in addition to being a depiction from the Bible, is also an allegory of sexual pleasure. The beautiful, naturalistically depicted, naked women’s bodies stand for lust and embellishments of worldly trumpery. Lot’s two daughters, however, make an appealing subject for admirers of art, readily revealing the double standards of the times with the viewer shuddering at the horror and simultaneous sensuality of the scene.

For this depiction the artist uses one of the oldest raw materials – beeswax. Since Antiquity wax has been valued as a material for its aesthetic and intrinsic qualities. Purified and bleached wax bears similarities to the human skin like no other material used in sculpture. Wax is easy to model, cast and rework at a later stage, something that is not possible with clay or cast metals. Wax can easily be mixed with pigments as well or painted in different colours. By mixing additives wax can also be made softer or harder. Every workshop had its own recipes. In his treatise on sculpture, Della Scultura, Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) writes that wax becomes softer after adding fat, less malleable after adding terpentine and hard when mixed with pitch.1 Wax was also a popular material for portrait medallions.