3 minute read

18 Ewer with Bacchanal and Procession of Sea Gods, by the Master I.C

from JB Test 01/22

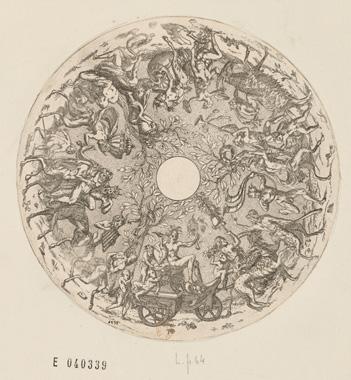

Fig. 1 Jacques Androuet Du Cerceau, Tome VI, Fol. 30. „Cortège de Silene et du jeune Bacchus, projet du fond de coupe“, vers 1546, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, MFILM E 040339. L.p. 64. Enamel objects with decorative grisaille painting are typical of the ‘IC’ workshops. Figurative and decorative elements are applied in white on a dark ground with delicately differentiated areas of light and shade. Grisailles were left monochrome or, in this case, coloured by pigments applied on top, creating the illusion of a bas-relief.

Jacques Androuet Ducerceau, whose engravings provided the basis for the ornamentation on the ewer, strongly influenced Limousin decoration in the 16th century with his graphic designs. Stylistically these belong to the Fontainebleau School, a French variation of Mannerism. Thanks to printmaking, these popular artistic models soon became widespread.

Advertisement

Our ewer belongs to a large group of very similar vessels from the workshop of the monogrammist ‘IC’ that are characterised by the same decorative principle.

At the time they were made, enamel objects of this quality were considered absolute luxury items, intended less for everyday use and more as decoration in a nobleman’s palace or a wealthy burgher’s house. Several enamellists from Limoges even created portraits for the French royal household. Today, enamel objects bearing the signature ‘IC’ can be found in international museum collections including the Louvre, the Frick Collection and the Walters Art Museum.

18

Damascene Mirror

19

DAMASCENE MIRROR

Italy, probably Milan Second half of 16th century

Steel damascened with gold Height: 30.5, width: 20 cm

Provenance:

Oscar Bondy Collection; Private American Collection.

This mirror is an excellent example of a rarely preserved Italian furnishing made of steel, from the latter half of the 16th century. Damascened in gold, the front, back and both sides of the rectangular mirror frame are adorned with elaborate, Greco-Romaninspired foliage and geometric decorations characteristic of the decorative arts of the period. In the centre of the cornice crowning the mirror, a small figurine of a putto extravagantly flourishes a laurel wreath, a symbol of victory, success and achievement. The mirror decorations have many similarities with the damascened plates on the casket from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 1).

The technique of damascening is believed to have originated in the Middle East and was named after the Syrian city of Damascus. While technically quite demanding and time consuming, the method facilitated a greater variety and complexity of designs, commendatory of both the object’s aesthetic splendour and the accomplished skills of its maker. Damascene surfaces are lavishly and often colourfully decorated, while also being very durable. The technique consisted of the inlaying or encrusting of precious metals onto iron or steel surfaces. In Europe, the most common process involved cross-hatching the iron surface using files to create puckered edges onto which the craftsmen could apply gold and silver leaf or wire that was then burnished flush with the surface.

During the late Renaissance period the technique became particularly associated with Milanese metalworking, known for producing elaborate armour for the noblemen of Europe, as well as high quality iron and steel furniture and decorations. The northern Italian city of Milan was one of the most populous and wealthy western cities of the time. Its continuous prosperity and growth in the 16th century occurred in spite of periodic plague epidemics, as well as frequent battles during the so-called Italian wars. Vastly subsidised by Sicily, Naples and Spain throughout these turbulent times, the city maintained and even increased its importance in a political and economic sense, becoming a synonym for high skilled manufacturing and the production of luxurious goods in any material and supplying highly praised products to every European court.

Fig. 1. Casket, Italian, probably Milan, circa 1545-47, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Inv. no. 56.139a,b

19