Eco-Art Activities For The Classroom

An innovative approach to environmental education.

presented by Carissa Welton

Table of Contents

• Introduction

• Eco-Art to Raise Awareness

• Getting Started

• Case Studies

• Lesson plans

• Sample Activities

• Quiz

• Resources

• Assessment Tools

• Feedback Forms

2

Introduction

It is really a joy for me to share everything I know about teaching eco-art with you. As educators, mentors, and trusted guardians – we all have a huge impact on what kind of future the children in our lives will have. Eco-art teaches them how to steer that course creatively and harmoniously with nature.

Over the years I have collaborated with several forprofit as well as non-profit partners to share creative ideas for environmental education. As a result, I have come to a fundamental conclusion that I continue to cultivate and develop:

Art is a language tool that needs no words to convey complex topics, allowing people of various backgrounds, education levels and cultural barriers to come together on the subject of environmental preservation. Over the years, I have found that the most successful method of producing and delivering eco-art experiences has been when I involved the “viewers” in the art-making process itself. Through the act of participation, the viewers become art creators themselves, joining a larger community to address or solve an environmental problem at the same time.

3

Calling Public Attention

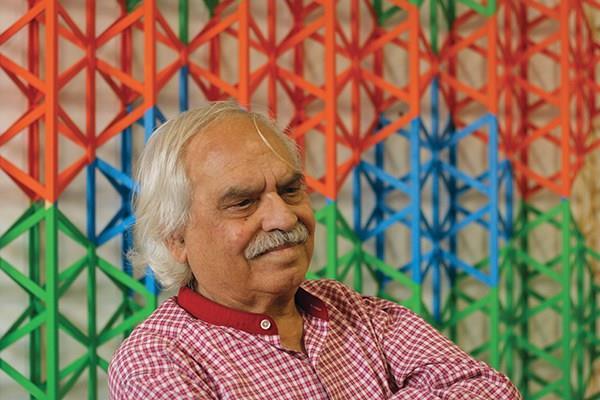

First, let me introduce myself. From 2007 -2017 I designed and produced eco-art activities in the USA and China. I am the co-creator of Greening the Beige, a non-profit volunteer network that promoted environmental awareness through art and community events.

4

Carissa Welton, Greening the Beige, Earth Day Meeting, 2007

The idea for Greening the Beige was actually born from a crosscontinental artwork called Refoliation. In Fall 2006, my creative team and I were selected by the Black Rock Arts Foundation for their annual event.

Our sculptures premiered at Burning Man 2007, the BLA’s annual event, and would later be presented in public spaces to further draw attention to the subject of plastic pollution.

Refoliation was a series of 5 lifesize trees made from recycled metal

(for the trunk and branches) and used plastic bags (for the leaves). The base of the trees were sourced and made in California, while I took charge of gathering 5,000 used plastic bags from the streets of Beijing, where I lived at the time.

Jennifer Forbes, Refoliation artist, Burning Man 2007

5

Through my research, I learned that China was actually importing waste from the USA to “recycle” but was struggling to do so. This made the significance of Refoliation come full circle, as I was importing “trash” back to the USA from China to help tell this story.

6

Jessica Reeder, Refoliation artist, learned how to weld for this project.

Beijing Street Sweeps

In order to meet the goal of collecting thousands of plastic bags for Refoliation, I began connecting with local environmental organizations and calling for more interested volunteers.

That was how I met Global Villages (Beijing) and their university student volunteers (pictured here) who helped me with plastic bag collection efforts. The students’ primary focus was the Plastic Bag Reduction Network, which was lobbying government officials for a plastic bag ban.

7

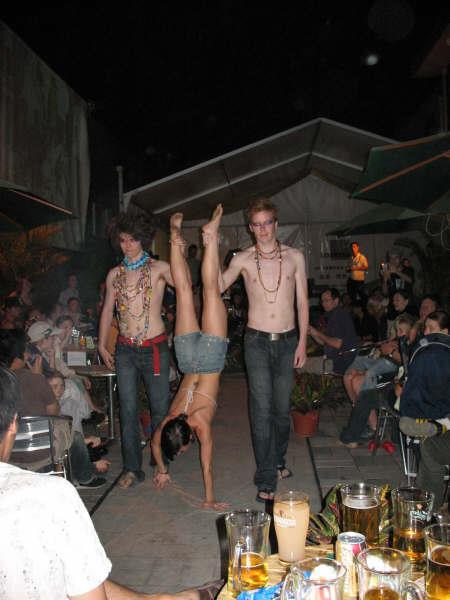

Refoliation was an interactive artwork and storytelling project. When it premiered in August 2007, we handed out leaves to Burning Man participants, inviting them to “refoliate” the branches of our trees. That gave us a chance to talk about the plastic pollution pandemic and raise awareness of the issue, just as the street sweeps helped us explain the plastic problem in Beijing.

8

Refoliation

The Mangrove Public Art Sculpture Garden, Reno, Nevada, 2008

The story telling continued even after Burning Man.

9

Since not everyone could see Refoliation at Burning Man, I organized a full day festival that brought everyone together to raise environmental awareness through music, dance, photography, DIY workshops, guest speakers and films. I could never have done it without the help of all the artists, volunteers, and organizations I had met through researching plastic pollution in Beijing. We called it “Greening the Beige”

), a crafty nickname, with beigesymbolizing the color of Beijing’s polluted skies.

10

(点废成绿

Lin Cuicui and her ecofashion designs, 2007.

That was how I met Lin Cuicui, a college student and member of the Plastic Bag Reduction Network, who was very passionate about the environment and fashion design. She inspired us to include an

“eco-fashion” show in our event.

Cuicui designed two outfits for the show with 500 bags she had collected from fellow dormitory students.

That’s when I realized Greening the Beige sparked creativity as well as community engagement.

11

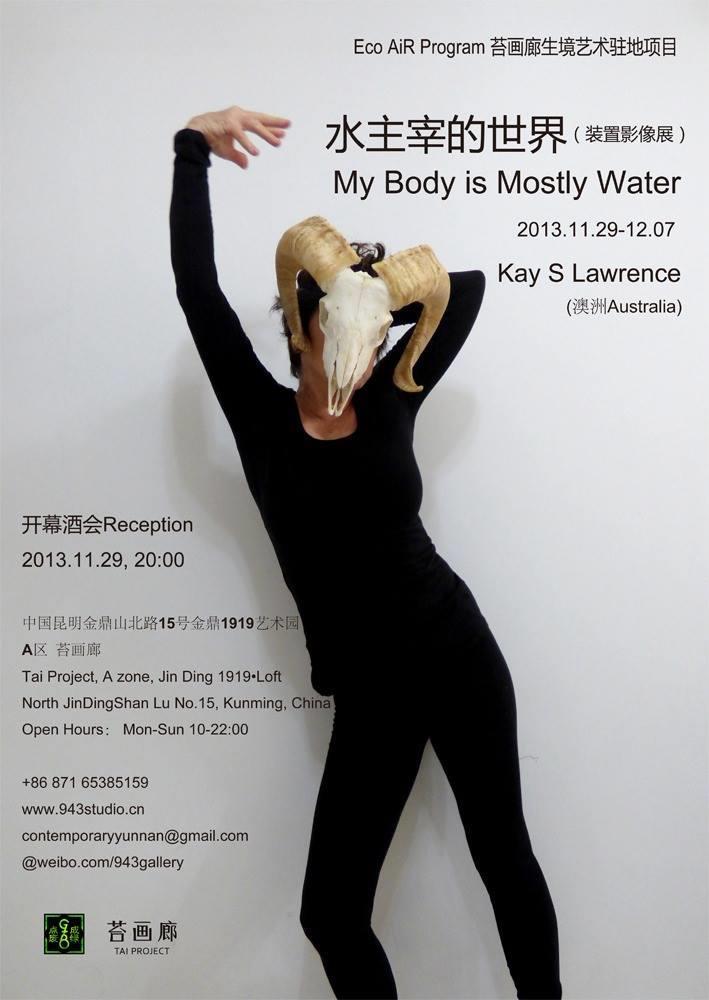

With the help of more than 100 volunteers, I spent the next ten years developing a variety of interactive eco-artworks through Greening the Beige. I held workshops and events not only in Beijing, but that reached cities across the nation. It became an annual event festival in Beijing from 2007 – 2013, that included a “GtB Fund for the Arts” and awarded emerging eco-artists across China as well as provided an international artists’ residency placement.

12

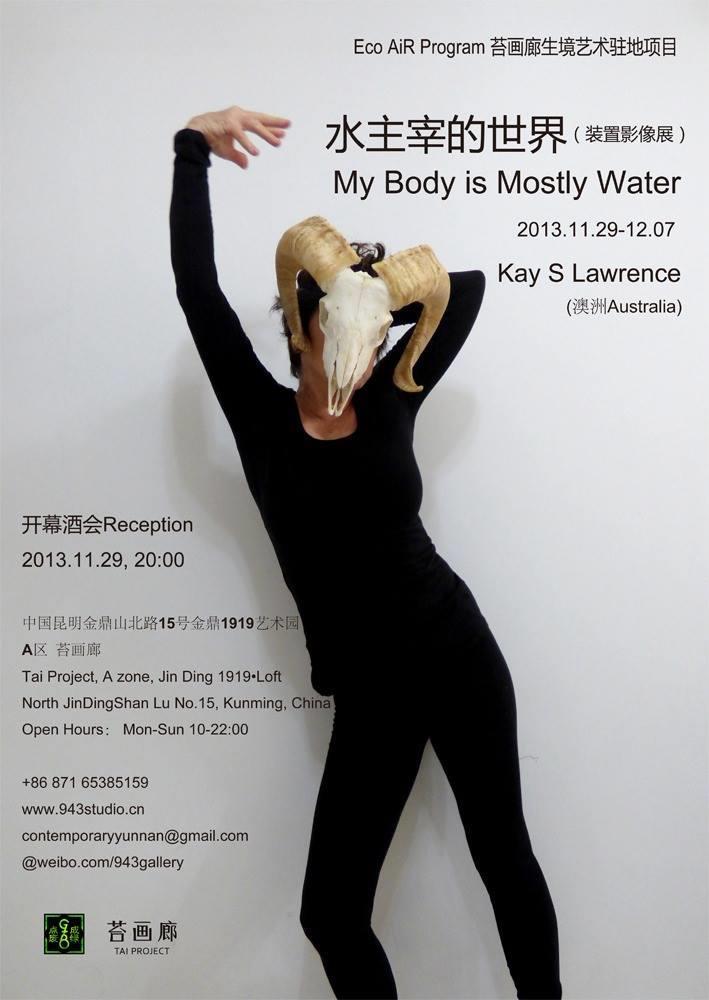

GtB 2013

GtB 2010

GtB Fund for the Arts 1st Place: Feng Feng

Eco-AiR Exhibition at 943 Studio, Kunming

13

Today Art Museum

Monthly Event Series, 2014 - 2015

The focus of Greening the Beige events were always based on waste management issues and using recycled materials, but also aimed to connect this problem to others like air pollution or species extinction and inspire creative solutions to tackle them all at once.

By 2009 I started to focus more on youth involvement and looking for ways to bring these issues into more schools and classrooms.

15

From 2014 – 2019 I became a mentor with the Jane Goodall Institute China’s Roots & Shoots youth leadership program. With the help of science and art teachers, I was able to launch Roots & Shoots activity clubs at 3 different schools for students ages 8 – 17.

16

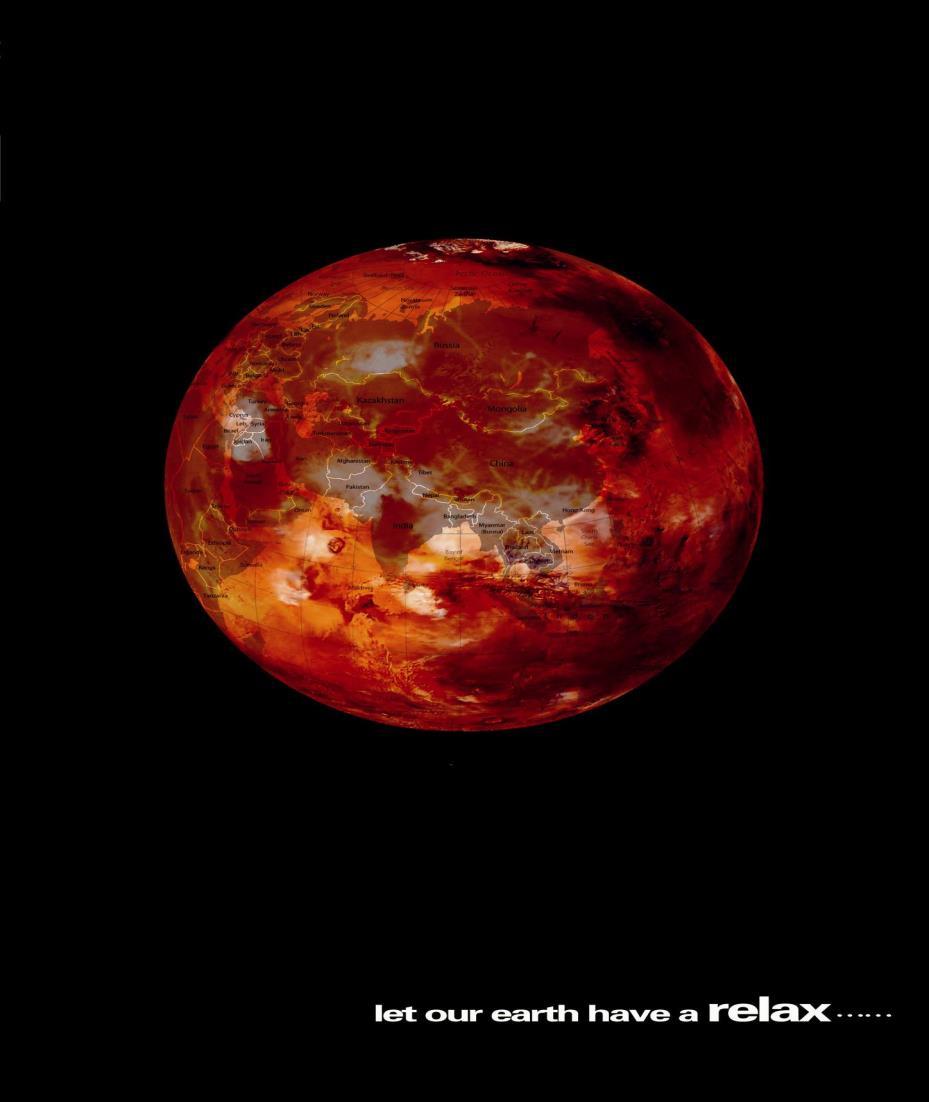

Eco-Art to Raise Awareness

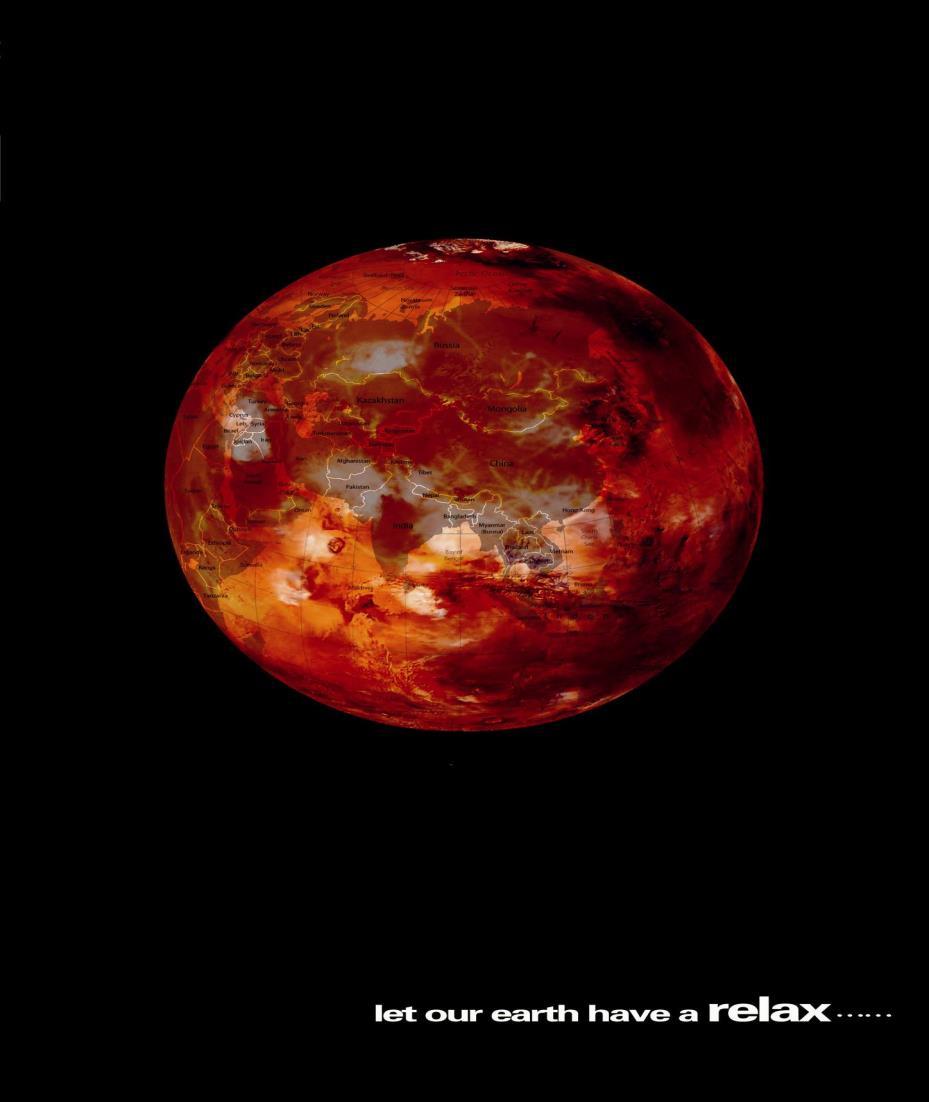

Art by AVA Creative

Through my experience over the years, I feel confident about the benefits from eco-art creation and the public awareness that it can raise.

Eco-art is a relatively new term in the art world. It is a response to a modern age conundrum; an art form that emerged with the rampant desecration of natural resources. It is sometimes confused with land art or environmental art, which also focus on nature. It is not a style but a mission.

I know that I have personally benefited tremendously, not just as a teacher but as a human being, from finding ways to “turn trash into treasure”.

In fact, I would love to hear your feedback as I am still learning about this process and trying to improve upon my delivery on a regular basis.

In fact, eco-art often excludes earthy materials and themes, instead highlighting the inorganic, man-made, toxic perplexities that threaten global society. Sometimes it is a combination of both themes which might illustrate damaged nature or demonstrate mankind’s self-destruction; invite hope or offer a solution.

17

Question:

What do you notice about the materials in both of these eco-art installations below? What kind of environmental message do you think they might have, just based on the materials chosen alone?

18

Central Academy of Fine Art, student installation 2007 / GtB Vertical Garden Simulation, Natural History Museum of Beijing, 2011

Another advantage of raising awareness through eco art is that it doesn’t rely on education or experience levels for learners to participate. Eco art can transcend language barriers and diverse cultural backgrounds. Complex ideas can be conveyed through the immediate experience of an artwork that might otherwise be too abstract to comprehend with words or numbers alone.

“Barber” GtB Art Submission, 2013

Sometimes an actual problem gets resolved through the creation of the artwork itself. For example, when Central Academy of Art student volunteers created “reverse graffiti”

(pictured left) with GtB.

19

Interaction

An essential element from Burning Man that Greening the Beige has carried interactive component to our art and activities. This is also an essential element of eco-art.

“Ecological art, or ecoart to use the abbreviated term, is based on an embodied sense of the artist in a larger web of interconnected relationships. Ecological art is much more than a traditional painting, photograph, or sculpture of the natural landscape. While such works may be visually pleasing, they are generally based on sublime, awe inspiring or picturesque, preconceived views of the natural world. Ecological art, in contrast, is grounded in an ethos that focuses on communities and interrelationships. These relationships include not only physical and biological pathways but also the cultural, political and historical aspects of communities or ecological systems.”

-- Ruth Wallen, artist

20

Today’s cities are filled with people who have become disconnected from nature.

Eco-art can help restore this connection by showing people (and perhaps revealing for the first time) the extraordinary wonders of our natural world.

21

Mia Gege Deng, GtB Volunteer, Sequoia Hug, 2012

It is important to remember that restoring and maintaining the delicate balance of Earth’s ecosystems in the midst of the 6th mass extinction is no easy feat. While eco-art alone cannot heal the damage that has been done, it might provide a space to grieve climate change and loss. Eco-art can help connect people around the world. It can create ways for more people to cooperate in the process of environmental protection, and (ideally) enjoy themselves in the process. This can have ripple effects that rapidly seep into cultures worldwide that get passed on through generations to come.

22

In 2009, Rasheed Araeen called for artists to focus their attention “on what there is in life, to enhance not only their own creative potential but also the collective life of earth’s inhabitants” (“Ecoaesthetics: A Manifesto for the Twenty-First Century” p. 684). Ultimately, it was a call for a critical mass to make a paradigm shift; for the cultural designers -- the artists –who are largely responsible for making the world a better place to live in, to effect change.

When we involve the public to become involved in our artwork, we empower the creative instincts of human nature, potentially unleashing a new era of enlightenment. Focusing this kind of collective artistic energy on environmental protection dangles the promise of exquisite results.

23

Reflection Point

• What motivates your students?

• What do you think might help them become involved/concerned about environmental issues?

• ________ is the key to starting an ecoartwork.

24

25

I always teach my students that observationis the key to starting an eco-artwork.

Eco-Art In the Classroom 26

Getting Started

Before the fun can begin, check to see if your classroom is eco-art ready.

Here are some tips:

•minimalism Create classroom rules implementing a class rule that all students must use the front and back of any piece of paper before it goes in the recycling bin. Talk to them about how paper comes from trees, how important trees are to all life on earth, and that by doing something as simple as using the whole sheet of paper, they can help protect our forests. (Opting for recycled paper when making your purchases also makes a big difference.)

•art supplies such as construction paper are standard in most classrooms for young children. Teachers buy them new so kids can create colorful art projects. However, it’s worth considering reusable options for art projects. Junk mail, magazines, gift bags and any of the countless paper items we come into contact with each day can be saved and used by students. Need construction paper because you have to have a solid color? Make sure that students put the scraps into a tub to be used for the next project. Also, encourage them to bring in found objects like colorful ribbon or old wrapping paper to add to the supplies. Little pieces can be just as great as large pieces when it comes to expressing a creative vision.

27

•choose eco-friendly pens and pencils. If you do a quick search online, you’ll find pencils and pens made from denim, newspapers, recycled plastic and tons of other materials you would never have thought could create a writing implement. Make those available for students to use and be sure to educate them on why their pens and pencils are earth friendly.

•go virtual. Working with older kids? Ask them to write their papers on computers (they most likely do anyway), but instead of printing out their stories and essays, ask them to email you the final result.

28

turn off the lights! Anytime the classroom will be left empty, the last student to leave should know that the lights should always be turned off. This is a simple way to conserve energy. If it’s a particularly sunny day and you have great light in the room, you might even find you only need to turn on half the lights or none at all. bring plants into the classroom. Not only will they purify the air, but you can help students learn how to care for living things by assigning a different student each week to be in charge of watering the plant.

29

Make sure the recycling bin is well placed. Human beings tend to make their choices based on convenience. Make your recycling bins much more easy to find and use than the trash can. In a classroom, because paper is the main tool, very little should actually be thrown away.

30

Reflection:

Can you think of anything to add to this list?

I’d love to add to this list and credit you for the feedback.

31

Once you’ve got your classroom and materials arranged, you can get on to the fun stuff: inspiring your students!

Show them outstanding works of eco-art. Encourage long brainstorming sessions. Watch videos about challenges and creative ways they were overcome.

Simple but effective eco-artwork examples to inspire!

33

Take a nature walk and remind students how important it is to make the connection between themselves and their surroundings. You don't need to go somewhere special, you can even do this in the schoolyard or nearby park!

Make a game out of your lessons with a clear goal in mind. Scavenger hunts can be fun activities for students of all ages. Or ask children to bring along their sketchbooks and draw what nature inspires them to draw.

34

Case Study

(taken from www.greenmuseum.org)

The Children's Forest Nature Walk

Location: San Bernardino, CA

Grade Level: 5-12

Artist: Ruth Wallen

In the San Bernardino Children's Forest youth are actively involved in the care and interpretation of forest resources. Artist Ruth Wallen was invited to work with area youth to develop five large interpretive panels to be placed along a nature trail of the youth's design. In a series of weekend workshops, participants created images and wrote stories from which, in consultation with the youth, the artist developed digital montages.

35

Each 24"x36" panel is covered with etched plexiglass, providing accessibility for the visually handicapped as well as a surface from which visitors can make etchings. On other occasions, Ruth also worked with youth to create an indoor mural for the Visitor Center and an Explorer Guide to the forest that has been widely distributed to forest visitors and schools throughout the San Bernardino/Riverside/Los Angeles region.

36

Reflection

How do you think Ruth Wallen guided her students to use their observation skills for this activity?

Research has revealed:

“Four days immersed in nature and the corresponding disconnection from multi-media and technology, increasing performance on a creative problem-solving task by a full 50%.”

37

Case Study for urban teachers:

Nature Walk in the City

Location: Baltimore City, MD

Grade Level: 7-10 & 13-17

Artist: Ann Rosenthal

This middle-school workshop was developed by University of Maryland Baltimore County students through the course, Imaging and Writing the Environment, crosslisted between the Art Department and Interdisciplinary Studies. Under the direction of Visiting Assistant Professor Ann Rosenthal, students engaged in readings and discussions to deepen their understanding of environmental issues, and surveyed how contemporary artists are responding to these concerns. Students identified environmental problems facing Baltimore City, and then agreed upon a collaborative community education project that highlighted connections between neighborhoods and the Chesapeake Bay. Mini-workshops were designed and taught by the college students to neighborhood children through the School 33 Arts Center, and covered Bay ecology, local tree identification, sewage systems, recycling, and postcard making.

38

Reflection

How do you think the University of Maryland Baltimore County guided their students to use their observation skills for this activity?

39

Lesson plans

40

Here are some examples:

WASTE: CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION

Purchasing goods and services for the sake of displaying wealth and earning status is referred to as 'conspicuous consumption'. Its flip side is 'conspicuous waste' defined as the disposal of any item that is still functioning.

Project: Collect the wrappings and packaging of everything you purchase over the course of a week and use these materials as your medium to produce a self-portrait.

Research / Discussion: All four artists in this section attempt to reduce the waste associated with conspicuous consumption by evoking guilt. Guilt is a product of three factors: awareness of having committed an offense; acknowledgement of responsibility for that offense; and feeling remorse. Discuss your personal contribution to the form of waste highlighted in any two artworks discussed in this section. Is guilt a part of your reaction? Estimate the effectiveness of the artist's strategy to induce guilt and affect change.

(source: http://lindaweintraub.com/teaching-guides/eco-issues)

41

What age students do you think this project would be best for?

Why?

What sort of challenges do you foresee with this lesson plan and your students?

42

Owls & Crows

Concepts, skills, and qualities taught: Review, Natural History

When and where to play: Day/Clearing

Number of people needed: 6 or more

Suggested age range: Ages 5 and up

Materials needed: Rope, 2 bandanas

Owls and Crows is an excellent game for reviewing information learned in class. To play, divide the group into two equal teams, the Owls and the Crows. Lay a rope across a clear area, and have the teams line up facing each other, each team about two feet back from the rope. About eleven feet behind each team, place a bandana on the ground to indicate home base.

When the leader makes a statement about nature, if the statement is true, the owls chase the crows; if it’s false, the crows chase the owls. If a player is tagged before he crosses the home base line, he joins the opposite team.

43

There is a certain amount of happy pandemonium in this game— players forget which way to run or are so confused by the statement that sometimes half the players run one way, and half the other.

To minimize chaos and make things as clear as possible, use blue and red bandanas to mark the two home bases—blue, behind the crows; red, behind the owls. Tell the players that the blue bandana represents “true blue.” When a statement is true, the owls chase the crows (all players run toward the blue bandana). When the statement is false, the crows chase the owls (all players run toward the red bandana). You can also point out natural features to remind players which way to run; for example, forest for true and meadow for false.

Make sure your clues are unambiguous and age appropriate. For example, if you say, “The sun rises in the east,” students may not be sure if you mean that the sun is first seen in the eastern sky (true), or that the sun rises at all—false, because it’s the rotation of the earth that makes it only appear to rise. The best statements are simple and clear: for example, “birds have teeth,” or “insects have six legs and a three-part body.”

Before beginning, it’s helpful to make a few practice statements. Have the players point in the direction they would run instead of actually running. Once everyone can easily point out the direction for true and false statements, then begin!

(source: www.sharingnature.ocom)

44

Activity 1

Now review the sample lesson plans by clicking here. Choose one to use with your students.

Reflect on the following:

1) Why did you choose this lesson?

2) What are the challenges you foresee with this lesson?

3) How can you potentially improve this lesson?

45

Activity 2

Now click here to read the hand-out Greening Arts Education Design a lesson plan for your students based on this material and what has been discussed so far.

46

Activity 3

Now go walk outside and observe your environment for at least 10 minutes.

Complete one of the following activities and design an activity based on your findings:

a) Take some pictures.

b) Collect some leaves, stones or shells.

c) Redesign a waste/recycle bin.

47

Congratulations!

You’ve reached the end of this workshop. Thank you for participating, I’d love to have your feedback. If you’d like to receive a certificate of completion for this workshop, just write your answers to the quiz below and send them to me in n email: carissawelton@gmail.com

Short Quiz

1. What is the key to starting an eco-art project? ___________________

2. Name at least 3 things you should do before you start class.

3. Would you be willing to share your lesson plans with other teachers here online?

48

Further Resources:

http://artofplay.weebly.com

http://ben.biomimicry.net/curricula-and-resources

http://www.hilaryinwood.ca/

http://www.mangroveactionroject.org

http://onehandoneworld.edublogs.org/

http://www,rootsandshoots.org

http://ruthwallen.net

Additionally, I designed a two week course (20 hours/week) for recycled art education. The course includes writing practice (creating a play and acting it out through puppetry – which students will craft and design themselves using recycled materials. It’s a lot of fun! (Recommended for ages 7 – 10). Just contact me (carissawelton@gmail.com) and I will send you the materials.

49

Thank you for taking this workshop!

50

I look forward to hearing from you soon..