WATER CITY Milwaukee pioneers a freshwater future

RESCUE AND RELEASE

Injured wildlife get a second chance Track the rise of electronic dance music

TURN IT UP

Injured wildlife get a second chance Track the rise of electronic dance music

Every minute of our lives, our pulse is constantly fluctuating. Whether we are standing up or lying down, moving around or sitting still, stressed or relaxed, our heart rate is constantly changing — just like our lives. Scientists say that our heart rate adapts to our body’s need for energy throughout the day, just as we as a society adapt to the changes life throws at us.

To say the last two years have been hard is an understatement. We have lived through one of the worst pandemics forcing us into an international shutdown while facing an increasingly polarized political environment that has further divided our country. The situation has forced our society to revamp and reevaluate the way we live.

Through all of the hardships, we often find ourselves asking: What does it truly mean to be alive? While for some it might mean living every day to the fullest and striving to become an elevated version of themselves, for others it means doing what has to be done to make it through to the next day.

This year, the Curb team took the “Pulse” of Wisconsin. We dug into what drives the heart that beats and propels us forward. In this issue, we explore the passions, hardships and discoveries that shape the people of Wisconsin.

We traverse the state through stories of how both people and businesses have fought to survive these difficult years, what they have done to continue to thrive and how they strive for greatness, bettering themselves and the surrounding community. It’s only up from here.

All the best, Editor In Chief

There’s more to love!

Visit us at curbonline.com

Curb is published through generous alumni donations and administered by the UW Foundation and in partnership with Royle Printing in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin.

©Copyright 2022 Curb Magazine

Brooke Messaye, Editor In Chief

Gina Musso, Managing Editor

Erin Gretzinger, Lead Writer Christy Klein, Lead Writer

Erin McGroarty, Lead Writer Charlie Hildebrand, Copy Editor Allyson Fergot, Copy Editor Zehra Topbas, Copy Editor

Ann Kerr, Business Director

Emily Rohloff, PR Director Jake Rome, PR Director

Samantha Benish, Marketing Representative Jamie Randall, Marketing Representative Robin Robinson, Engagement Director

Zoe Bendoff, Art Director Anica Graney, Production Editor Annabella Rosciglione, Production Associate Thomas Hill, Production Associate Perri Moran, Photo Editor

Nicole Herzog, Online Director Mason Braasch, Online Producer Matt Blaustein, Multimedia Editor Braden Ross, Multimedia Editor

Stacy Forster, Publisher

Unless otherwise noted, all photos are attributed to Perri Moran

By Zoe Bendoff

By Zoe Bendoff

We all have things that make us tick and fill our hearts with joy. Curb Pulse is all about diving into the lives of the people of Wisconsin to find out what drives their experience in the state. Here are some items to help you fuel the things that excite you. Whether you’re an avid music lover, a health nut, a connection seeker or simply enjoy the thrill of a racing heart rate, these products are sure to match your rhythm.

For the ones who just can’t stop the beat Happy Face Throw Pillow Bluetooth Speaker urbanoutfitters.com Listen to your favorite jams with quality sound technology from the comfort of your favorite spot in your home with this multifunctional pillow and Bluetooth speaker.

Game That Song amazon.com Test your knowledge of your friends’ and family’s favorite beats and build connections as you groove to the rhythm.

JBL Tune Wireless On-Ear Headphones 510BT target.com These lightweight, wireless headphones featuring JBL’s Pure Bass Sound make for an elevated music experience whether you’re getting your blood pumping or relaxing.

For the thrill seekers

Meta Quest 2: Advanced All-In-One Virtual Reality Headset - 128GB target.com Skydive, walk the plank or get in a bar fight from your living room with this virtual reality headset guaranteed to make your heart race.

“The Woman in the Window” by A.J. Finn amazon.com Anna Fox, who is suffering from agoraphobia after a car accident, thinks she witnessed a murder in her neighbor’s apartment. This psychological thriller will keep you on the edge of your seat.

For the heart healthy Avocado target.com Incorporating just two servings of avocado in your weekly diet can lower your risk for cardiovascular disease and heart attacks.

BlendJet 2 16 oz. Portable Blender bedbathandbeyond.com Whether you throw in hearthealthy leafy greens, fresh fruits or vegetables, this portable blender makes the perfect pulse, even on the go.

For those curious about what makes others tick We’re Not Really Strangers target.com Take your relationships to new depths and challenge your assumptions with this thoughtprovoking conversation game.

“I Never Thought of It That Way: How to Have Fearlessly Curious Conversations in Dangerously Divided Times” by Mónica Guzmán amazon.com Guzmán’s book teaches us we can find common ground to connect from the heart, even during the most polarized times.

1. How do you feel about the outdoors?

Find out where your next Wisconsin thrill should be! B. C.

A. Nothing’s better than fresh air I like it, but indoor plumbing is nice Eh, not for me

2. How much money are you comfortable spending on a trip?

A. Honestly, I need to save money I have to buy some souvenirs I’m treating myself! B. C.

3. Do you like roller coasters?

A. They’re alright I LOVE THEM! I get motion sickness B. C.

4. How do you feel about crowds of people?

A. Solitude is my sanctuary I can live with them I like getting lost in the crowd B. C.

5. Who are you taking on this trip?

A. Me, myself and I Looking for some family fun Just my S.O. and me B. C.

6. What would you rather do?

A. Fish for a musky Go on a ghost tour See a live band B. C.

7. How do you prefer to spend your weekends?

A. Hiking People watching at the farmers’ market Exploring museums B. C.

8. What are you packing for the trip?

A. The book on my nightstand A camera Headphones B. C.

9. You feel your best in...

A. Athleisure

Tee and blue jeans Anything that says “fashion” B. C.

10. Why do you want to travel?

A. To escape day-today stress

To have as much fun as possible To explore the city I’m visiting B. C.

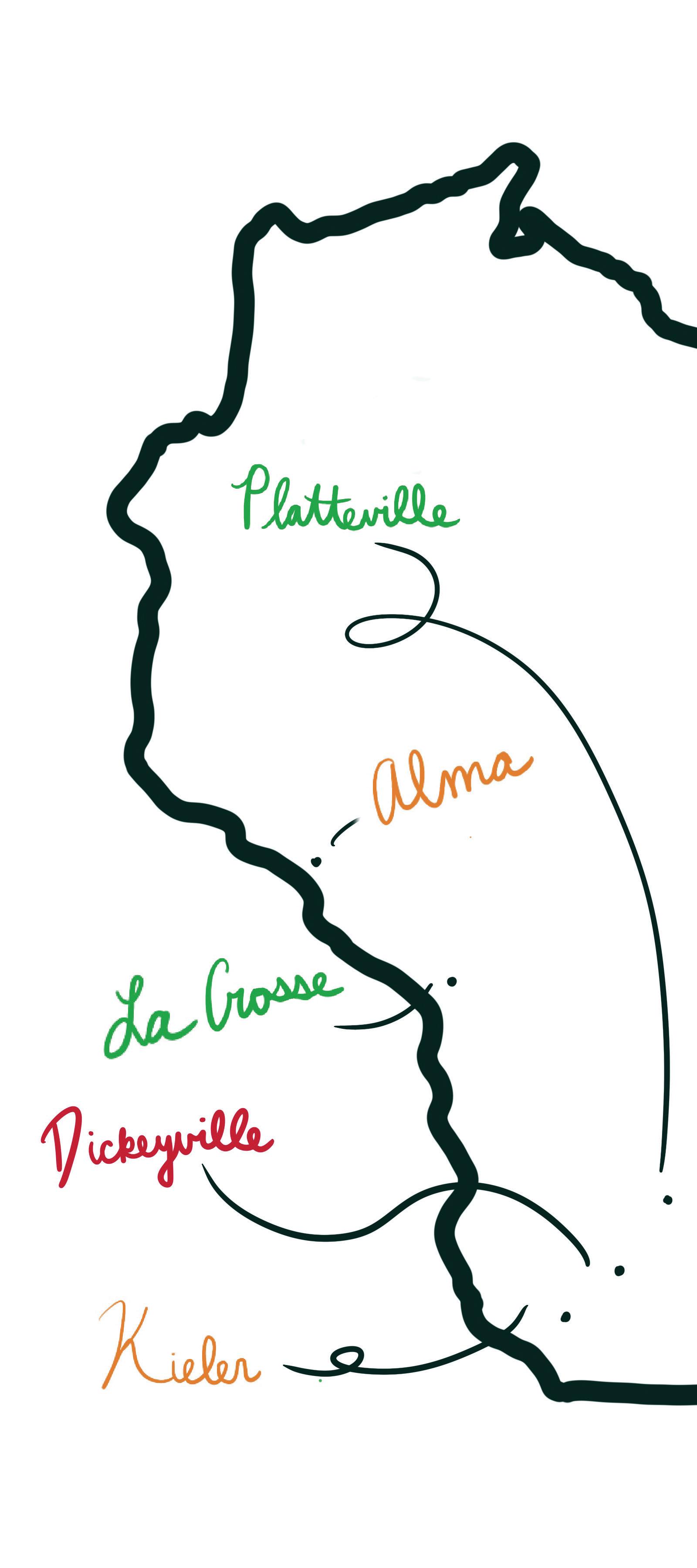

The Northwoods offer an opportunity to disconnect from technology and reconnect with nature. Night fishing, waterfall chasing or snowmobiling are sure ways to get your blood pumping.

The “Water Park Capital of the World” has a little bit of something for everyone. Tall roller coasters and water slides will keep an adrenaline junkie satisfied. If those aren’t your thing, magic shows, haunted houses or riding in one of the Wisconsin Ducks will give you the excitement you seek.

Between great food and cool museums, Milwaukee is a great place to visit if you’re looking for a thrill. Don’t forget to listen to some live music or visit the Milwaukee County Zoo while you’re there. Being around the buzz of Wisconsin’s biggest city will make you feel alive.

Wisconsin’s economy thrives on the inventions founded here. Many places that you pass by every day have been the birthplace of groundbreaking new technologies.

In 1924, Carl Eliason created the blueprint for the first snowmobile. In the Northwoods of Wisconsin, Eliason was in a garage behind his general store in Sayner when he thought of the idea of a motor toboggan. This idea sparked the invention of the snowmobile.

American Girl Doll Pleasant Rowland developed the concept for American Girl dolls in 1986. The dolls were created to help teach girls important moments in history and aspects of girlhood, and each was built with her own unique story. The dolls were manufactured in the Madison suburb of Middleton by The Pleasant Company.

Christopher Latham Sholes worked as an apprentice for a printer, but after four years, he quit to join his brothers who published a newspaper in Green Bay. In 1864, Sholes saw the initial patents for a writing machine and decided to see if he could do something similar. In 1868, Scholes was granted his initial patent for his “letter-printing machine” in Milwaukee, and in the following years, he was granted two more patents.

As the days become shorter and the temperature drops, finding activities to keep busy can be a challenging task. Though Wisconsin is often known for its summer spots, there are a wide variety of both popular and hidden gems throughout the Badger state that offer ideal winter activities for all ages. Grab a hat and gloves, and start exploring!

Snowshoe, hike and ski your way through the picturesque scenery of Copper Falls State Park. Located in Mellen in northern Wisconsin, the park contains more than 15 miles of winter trails. Experience mystical frozen waterfalls and snow-covered views in this real-life winter wonderland. Whether you prefer an active adventure or a serene day trip, Copper Falls is the perfect winter destination to add to your itinerary.

Explore

While the Apostle Islands feature beautiful scenery in the warmer months, the mainland ice caves at the Apostle Islands in northwestern Wisconsin are also a breathtaking sight in the winter. When Lake Superior freezes over, the sea caves are laden with icicle formations. This is an ideal destination for winter sightseeing as the magnificent landscape can serve as an exciting opportunity for photos and an appreciation of nature.

Farmers’ markets are not just a summer activity — from freshly baked goods to satisfying soups, the Milwaukee Winter Farmers Market offers delicious treats for all to enjoy this winter. Visitors can support local vendors while tasting the best seasonal goods in Wisconsin. This is also a great place to purchase holiday gifts, such as jarred spices, jams and artisanal oils. While your heart (and stomach) may be full afterward, a break from the freezing cold temperatures at this indoor farmers’ market will keep your body satisfied this winter season.

BY ANICA GRANEY

Even in the bitter cold, these dreamy destinations thrive with possibilities

By Allyson Fergot

By Allyson Fergot

On the edge of a neighborhood park in La Crosse sits a dense prairie. Its tall, browning plants stand in stark contrast to the freshly mowed, dark-green grass that surrounds the park. It’s a clear line between careful control and self-suf ficient freedom.

When you approach the boundary between the manicured lawn and the native landscape, you realize how thick the prairie is. Thatch from the plants conceals the ground, mak ing the soil something you can only imagine. The winding yellow-green grasses 10 yards from the border block your view to the other side. The prairie is only four acres from one end to the other, but you could easily get lost in the thicket.

There’s a soft but constant buzz in this ecosystem alive with various insects and birds. The purple, yellow and white flowers visible to an out sider are dotted with the few remain ing pollinators. It’s autumn now. Soon the sound will dull, the flowers will lose their color and the birds will migrate south.

This prairie, a sanctuary for wild life and virtually impenetrable by humans, was not here 15 years ago. It was brought into existence in the late 2000s by a group of amateur conservationists who were interested in bringing Wisconsin’s native land scape into the future.

Before European settlement, prai ries were an essential tool for the well-being of Wisconsin’s habitants. The prairies’ ability to create nutri ent-rich soil led Europeans to con vert them into agricultural land. When Europeans first settled in Wis consin, prairies took up 2.1 million acres. Today, less than 10,000 acres of native prairie remain. In their place stand houses and farmland, shopping centers and schools, and miles and miles of interstate. This modernization left prairies as one of the most decimated landscapes in the U.S.

Now, some Wisconsinites have dis covered a passion for restoring Wis consin prairies.

“It’s progress and whatnot, but I think you have to have a good imagi

nation to think back prior to Europe an movement here ... to see the native grasses and plants and trees,” says Gregg Erickson, one of the amateur conservationists that reconstructed the prairie by the park.

Erickson, now retired, used to work as a science teacher at Central High School in La Crosse. About 15 years ago, Erickson wrote a grant for seeds to grow a prairie containing native plants where he could take his students for educational purposes.

Erickson’s friends, including my dad, helped him prepare the land, plant seeds and burn away weeds in order to establish the new prairie. Now, whenever I walk through my neighborhood or play volleyball in the park with my little sister, I get to see a sliver of what Wisconsin used to look like.

Since restoring the prairie in my neighborhood, Erickson has recon structed more prairies, including one in his backyard. A prairie brings with it a whole ecosystem, and Erickson says there has been a clear change in the wildlife behind his house.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ALLYSON FERGOT The author’s father helped restore this prairie in La Crosse in 2020.“Turkeys love to eat grasshoppers, and because we have so many grass hoppers around, there’s turkeys all over the place laying their nests in our grasses,” he says.

Jack Buswell, an attorney in Spar ta, a half hour east of La Crosse, first got involved in prairie restoration and management in 1997 when he took over his family farm.

“The real reason I did prairie res toration was to create upland habi tat for birds such as pheasants and quail,” Buswell says.

Prairie restoration is not for the faint of heart, though. The prepara tion process and continuous weed removal can be tedious, and it can take years before the first native plants sprout. A prairie requires lit tle maintenance once established, except for a routine cleansing every few years to clear dead plants and any invasive weeds that have sneaked into the area.

One of the best ways to effective ly get rid of weeds is through one of Earth’s most feared elements: fire.

There are other ways to maintain a prairie, like spot treating weeds using herbicides or by mowing, but Neil Diboll, president and owner of Prairie Nursery in Westfield, in the central part of the state, says fire is the best method.

Although starting out can seem overwhelming, conservationists agree the benefits associated with re storing a prairie outweigh the initial investment of time and money. Not only do restored prairies add natu ral beauty to a landscape and create habitat for pollinators and endan gered species, they’re also a crucial component to fight climate change and mitigate its effects.

Prairies can store carbon deep into the earth because their root system stretches multiple feet into the soil. This makes prairies incredible car bon sinks, which means they absorb more carbon than they release.

The soil structure and root system of prairies also absorb water quickly. This water absorption mitigates the effects of flooding.

Because of habitat creation, envi

ronmental impacts and sheer beau ty, people working in prairie res toration have noticed an increased interest toward it.

“I think things have really been picking up momentum and picking up steam... in the areas of prairie conservation, protection and man agement,” says Armund Bartz, a con servation biologist at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

The DNR has partnered with private landowners to restore and manage properties. Darcy Kind, a private lands biologist with the Wisconsin DNR, focuses on resto ration and management to benefit at-risk species. Since she started working on the program in 2005, there has been a steady increase in people looking to restore prairies.

“Some people feel like they need to create this habitat because they really want to see monarch butter flies,” Kind says. “Then some people know the history of the property, know that they once had a prairie on their property, so they’re trying to get it back.”

Other groups across Wisconsin are working toward improving the status of prairies in the state. The Grasslands 2.0 project is educating farmers on how agricultural land can be converted into future grass lands and native prairies, which can be grazed by cattle; much like how Wisconsin’s native prairies were once grazed by bison.

Despite the steady increase in in terest, Bartz is hoping more people across the state become involved in prairie restoration. “It’s an under dog habitat that really needs help,” he says. “Prairies are a part of our history, part of our culture, a link to the past and a potential resource for the future.”

This prairie in La Crosse is starting to die as winter approaches. The plants will be back in bloom by summertime.

The morning fog covers rush hour on Reiner Road in the unincorporated community of Burke.

It is not uncommon for one to be curious about the in-between.

The homes, farms and play grounds that we see in a passing blur as we zoom by on the county high ways and interstates.

For much of Wisconsin, these are unincorporated towns and commu nities. They’re tucked in between cornfields quilting central Wiscon

the unincorporated town of Burke offers residents the quieter, smaller community feeling they were look ing for. Burke — sandwiched be tween Madison and its largest sub urb, Sun Prairie — was founded in 1851 after its separation from the nearby commuity of Windsor.

Burke quickly became a popular layover spot for travelers as early settler Horace Lawrence established The Prairie House, a hotel located on the road from Burke to Portage.

While The Prairie House no lon ger exists, Burke is still a common travel pit stop. Many people take advantage of the gas stations located along the interstate in Burke.

“That’s an opportunity that wouldn’t be available if it were a larg er community because it’d be such a higher population,” he says.

In 2036, Burke is slated to be an nexed by the surrounding towns of Madison, DeForest and Sun Prairie.

Berg explained that Burke’s bigger neighbors could annex any land they wanted as long as it was adjacent to their own borders.

In 2004, the people of Burke worked with lawyers to create a boundary agreement between these three municipalities to allow the town to remain unincorporated.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ANN KERRsin, resting below a series of lakes and filling the sprawling root of the peninsula. These places narrate the story of the state’s rich history.

In Wisconsin, there are 1,246 un incorporated towns spanning all 72 counties. These towns provide fun damental services to about 95% of Wisconsin’s geography and 30% of its population.

Even though these communities don’t have typical municipal gover nance, they have a heartbeat of their own that means something to the people who live there, and they are fiercely loyal as a result.

For Steven Berg and Lisa Rubrich,

“It’s kind of a funny thing that people stop here on their way to somewhere else,” Berg says.

Rubrich has lived in Burke since 2003 and now serves as a supervisor on the town board.

She initially moved to Burke be cause her kids could be bused to nearby schools. In addition, the lot sizes were large and she could pay for and manage her own well and sep tic systems, making her yearly taxes lower. The town was also quiet and neighborly.

Berg moved to Burke in 2004 to be closer to his job in Madison. Since living there, he’s served on four dif ferent commissions, as well as the town board.

While this agreement freed Burke to prosper for the last 18 years, its expiration date is set for 2036, when Burke expects to be taken over by Madison, DeForest and Sun Prairie.

Rubrich wants people to remem ber Burke for the same reasons she moved there — a welcoming and friendly community that has operat ed smoothly on its own and served its people well.

Rubrich believes that the annex ation of Burke will change its per sonality “from a quiet hamlet to a quite different style of community,” she says. “We want to leave a legacy for people who are going to get an nexed so that they remember that ... Burke was Burke at some point.”

“That’s an opportunity that wouldn’t be available if it were a larger community because it’d be such a higher population.”

In January 1992, a single call for ever changed the lives of, Yvonne Wallace Blane and her husband, Steve Blane, co-founders of Fellow Mortals Wildlife Hospital.

In the days after that first call, around 150 sick Canada geese would be brought to Yvonne and Steve to be treated. There was no facility — only two bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen, a basement and a porch in

their little log cabin home located in the southeastern town of Delevan. Neither Steve, Yvonne nor their team knew what was wrong with the geese or if they could treat them. Fellow Mortals’ experiences treat ing wildlife involved dealing with fractures, head trauma, orphaning, starvation and dehydration, but never this.

Today, 31 years later, Fellow Mor

tals Wildlife Hospital is in a new lo cation near Delavan, in Lake Gene va, and takes in about 2,000 injured or orphaned wildlife patients annu ally at no charge. Yvonne and Steve, along with their team, have become the heartbeat of wildlife care, provid ing a place full of second chances for Wisconsin wildlife.

The nonprofit’s 52 acres and 10,000-square-foot facility includes

The owl, Darby, a permanent resident of Fellow Mortals Wildlife Hospital, rests on a perch at the rehabilitation facility.

The heartache and joy of the people who nurse Wisconsin’s wildlife back to health

a state-of-the-art hospital, heated in door habitats, large flights, a critical care wing and isolation wards.

Fellow Mortals relies entirely on donations. The organization receives some of their funding through a monthly donation program called Team Hope. Here, members can choose to donate anywhere from $1 to $500 a month. Donors for this program also receive quarterly email updates on how their donations are being used to provide direct care to injured and orphaned wildlife.

When tending to the sick geese in 1992, the Blanes sent the geese to be tested by the staff at the Nation al Wildlife Center in Madison, who confirmed the geese were contami nated with lead poisoning.

Yvonne, Steve and their team be gan treating the geese through lavag es, which is the removal of lead from the gizzard. They also called for help from local and state federal agencies, such as the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Yvonne, still heartsick about the event, remembers dreading each morning having to walk in the cold over to the holding areas to collect the dead bodies of the geese and bring those dying inside her house for warmth.

The geese in critical condition stayed in Yvonne and Steve’s small kitchen and living room to keep warm. The other geese were kept in kennels, set up hastily in their back yard, tarped against the bitter cold and wind with bedded straw and heat lamps.

Today, it is the memory of the 74th bird, who acted as a totem during that horrible time, that stays with the Fellow Mortals’ staff. To the Fel low Mortals’ team he represented all of the birds who were rescued, fought to survive, and lived or died. The team was able to release him on Easter Sunday of that year, and with him, release the horror of those few months. The state and federal agen cies’ belief in the Fellow Mortals’ staff and their assistance with per sonnel, advice, caging and evidence collection is what is helping make their effort a success.

The cause of the sickness was not dealt with until several years later, in October 1996, when the U.S. Envi ronmental Protection Agency began removing more than 28,000 tons of contaminated soils and sediments from the site where the Canada geese, and hundreds of other wild life, had been exposed.

It was the worst case of lead poi soning in southeastern Wisconsin’s history, and it was the first time the EPA ever got involved in a case that resulted solely in the loss of nonhu man life.

“I think we had about 300 animals maybe that year,” Yvonne says. “Our numbers pretty much doubled over night. That was really the turning point I think for us where we knew, or we realized, we had to make a de cision.”

And make a decision they did.

Gail Buhl, program coordinator for the Partners for Wildlife at the Raptor Center in Minneapolis, says Yvonne and Steve have brought high standards to the field of wildlife re habilitation in Wisconsin by creating Fellow Mortals Wildlife Hospital.

“They have the best practices in mind all the time. Yvonne and Steve working together to design build ings, caging, or whatever it is, is magic to watch,” Buhl says. “And that partnership is what really built Fel low Mortals.”

Their most positive experiences are the ones where the staff of Fel low Mortals can see the animals’ care come full circle.

“They heal very quickly and they

have a great will to live,” says Dr. Scot Hodkiewicz, a volunteer veterinari an at Fellow Mortals. “The goal of all these animals is to be able to get released.”

Last October, a goose was dropped off at the Fellow Mortals facility. She had been shot, had a broken leg and could not stand because of the tissue damage from the pellet embedded in her foot. However, she fought and fought, and she refused to give up. The goose accepted the care of the Fellow Mortals staff and eventual ly made a full recovery. The team was able to release her back into the

wild, an emotional moment for all the staff.

“She gets out and she walks up to the water, she spreads her wings re ally big, she does a little tail feather wiggle, and she’s so happy,” says Jes sica Nass, an advanced wildlife reha bilitator and biologist at Fellow Mor tals. “Those are the little gems that keep us positive and keep us feeling like we are doing the right thing.”

The Wisconsin public also appre ciates the effort and education pro vided by the nonprofit.

Nass recounts how in September 2022 a gentleman brought in an owl to the Fellow Mortals facility after he’d been watching it sit on a log for a long time. The man was nervous to help, but Nass and other Fellow Mortals’ staff talked to him on the

Wallace

co-founder

the Fellow Mortals Wildlife Hospital (second from left) and the core team of caretakers and specialists at Fellow Mortals Wildlife Hospital.

“It means a lot to us that one life is saved, because it’s a life.”Yvonne Blane, of

phone and guided him through the process of how to safely capture and bring the owl into the hospital.

The man, upon bringing in the owl, explained to the staff that he had recently lost his wife, who was an avid lover of owls. He believes the owl is her spiritual animal and his wife was trying to reach him.

“We, as humans, have the capabil ity to interject ourselves into these things and do the right thing,” Nass says. “It means a lot to us that one life is saved, because it’s a life.”

The respect for wildlife and all liv ing things propelled the idea of Fel low Mortals to flourish.

Its foundation dates back to when Yvonne and her husband managed a mobile home park. As Yvonne was mowing the lawn one day, she accidentally ran over a nest of baby rabbits. Yvonne, upset and unsure of what to do, called several animal hospitals, but none of them had a solution to help besides advising her to let nature take its course.

Unsatisfied with this answer, Yvonne and her husband took the

baby rabbits into their home and cared for them, nurturing them back to health and then releasing them back into the wild.

“For me, it is mostly a matter of respect, appreciation and a feeling of duty that these other species that share our space are being impact ed by human activities every single day,” Yvonne says. “They have no one to speak for them. They have no one to help them. They have no where to go. And so that’s really why we’re still here today.”

Fellow Mortals’ impact continues to grow. She and her husband want to convert Fellow Mortals’ 52 acres of land into a permanent home for wildlife that can no longer be re leased back into the wild.

They envision having local com munity, school and church groups come into a controlled environment and letting them interact with and learn about the different wildlife of Wisconsin, while making sure the animals still have privacy and space to retreat.

The team at Fellow Mortals Wild

life Hospital is passionate and com mitted to helping the wildlife of Wis consin, no matter the condition, size or species that comes to them.

“We really do run on faith and hope,” Yvonne says. “I sometimes say one promise, one purpose, one life at a time.”

An array of wildife can be found at Fellow Mortals Wildlife Hospital, including this baby squirrel who is a current Fellow Mortals resident.

By Erin Gretzinger

By Erin Gretzinger

The first time Emerson Boettcher cried about the cost of college, she was only in sixth grade.

It was the height of the Great Re cession. Then, her mother started to lose her vision — and eventually her job. As her family’s finances tight ened under the strain of unemploy ment, the dreaded question arose in Boettcher’s mind.

“I remember so clearly: That message is just like, ‘You need to go to college to get a job,’” Boettcher says. “And at the [same] time, I was just being told no to new basketball shoes; being told no to go to the movies; being told no to like literally any normal child experiences.

“And I was like, ‘Well, I’m having an abnormal life because of money. What if it doesn’t change, and I can’t go to college like everyone around me,’” she says.

But there was one thing that Boettcher’s younger self didn’t yet understand about paying for college: “Obviously, I didn’t know what the heck a loan was when I was 11.”

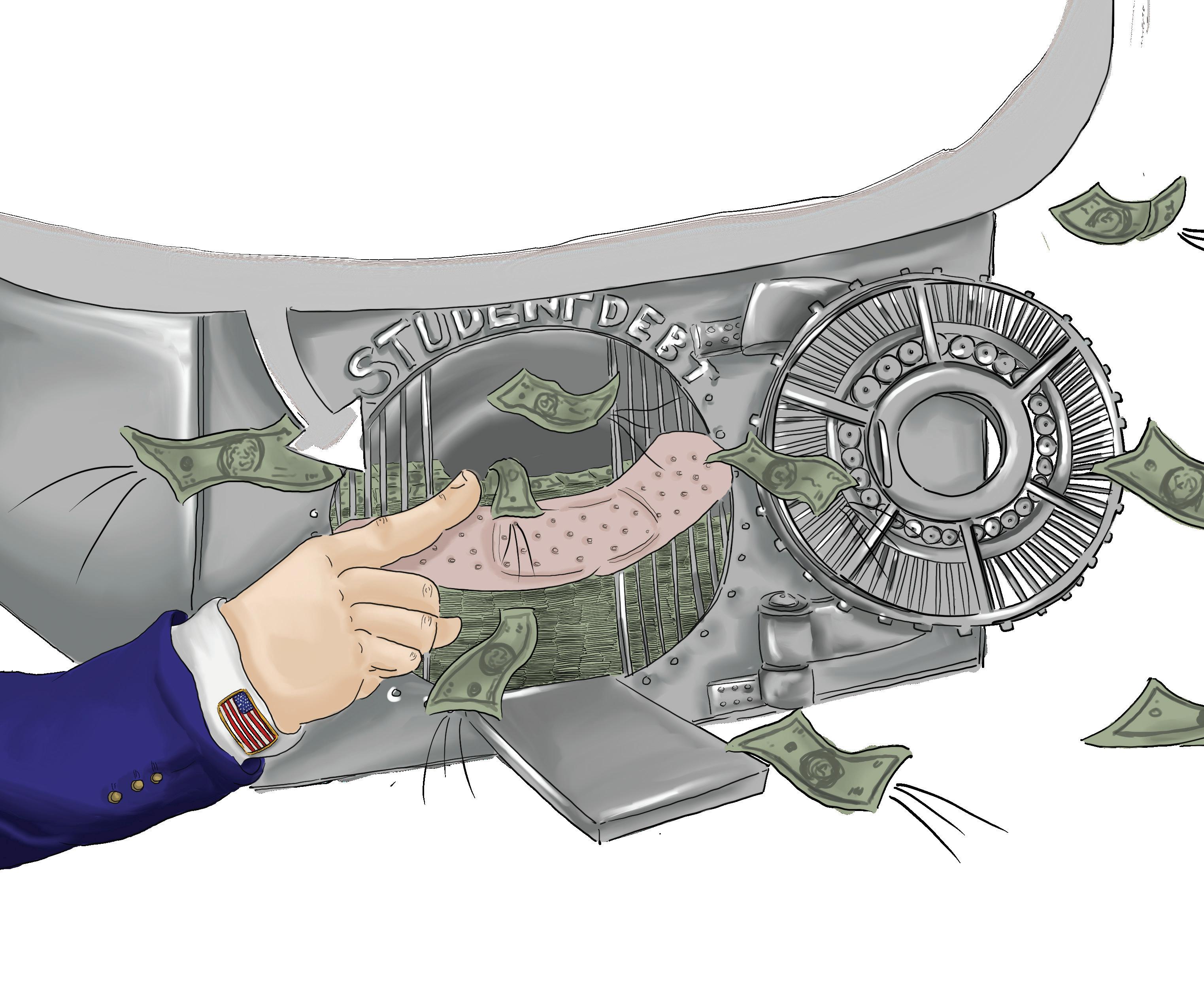

Boettcher, now a 24-year-old high school teacher in Minneapolis, says she feels like she is in a “pretty de cent boat” compared to others with student loan debt — with about $25,000 still remaining.

“This is defining the rest of your life,” Boettcher says of her student loans. “Not just the next four years,

nation’s borrowers, including more than 300,000 eligible in the state.

But the road to debt relief remains unclear as borrowers are stuck in definitely waiting to see if Biden’s plan will withstand legal challenges. Amid this period of uncertainty, ex perts have pointed out a blind spot in Biden’s plan: the danger of a onetime debt “jubilee.”

Regardless of whether Biden’s plan comes to fruition, experts and bor rowers will continue to grapple with how to combat the student loan crisis at its sources to sustainably address debt for borrowers today — and the next generation.

According to UW–Madison’s Stu dent Success Through Applied Re search Lab, an estimated 715,800 Wisconsin residents have federal student loan debt, which represents about one-fourth of the state’s labor force. Wisconsin borrowers owe $23.1 billion, putting the average balance at about $32,230 per person.

Cliff Robb, a UW–Madison expert in college student financial behavior, says the number of borrowers and the amount students borrow has in creased in the last decade. Account ing for inflation, tuition at public four-year institutions has more than doubled since the early 1990s.

According to Helen Faith, a stu dent loan expert who works as UW–Madison’s director of student finan cial aid, the university’s tuition costs over 22 times more than it did five decades ago.

“When you talk to folks who may be went to college quite a while ago ... [they] will say, ‘Well, you know, when I went to school, we just worked part-time and we covered our costs,’ and I think oftentimes there’s a failure to realize that the cost of education has gone up sub stantially,” Faith says.

Federal programs like the Pell Grant — a means-based award that doesn’t need to be repaid — were designed to help make college more affordable. But Robb and Faith say those support systems have not kept up with predictable rising costs. The Pell Grant, for example, used to cover nearly 80% of tuition at pub lic four-year universities. Today, it is worth one-third of its original value.

The result: Students take on more debt than previous generations.

Boettcher’s concerns about pay ing for college never faded after her epiphany in sixth grade. Despite be ing admitted to Georgetown Univer sity in Washington, D.C., Boettcher

instead left her northeastern Wis consin hometown of Two Rivers to attend UW–Madison and save some money with in-state tuition.

During college, she worked 20 to 40 hours a week and spent her spare time on scholarship applications. After graduation, Boettcher joined an AmeriCorps program, a non profit that provides service-year op portunities, in part because of grant assistance that offers some student loan forgiveness.

Following a similar path to Boettcher, fellow UW–Madison graduate Justine Mischka worked for AmeriCorps to help pay off part of her student loan debt. Still, she is unsure of when she will get out of debt.

“I work at a nonprofit, and we’re all 20-somethings with college debt,” Mischka says. “None of us have any sort of short-sighted goals of paying off our student loans.”

Significant at the Margins

Robb and Faith note that the av erage borrower can successfully pay off their student loan debt since college degrees often lead to high er-paying jobs. However, one-third of all borrowers don’t actually finish college. Other issues, such as mas sive interest accumulation or cer tain aggressive loan packages, can further hinder borrowers.

“It’s not like every person is in a bad situation because of student loan debt,” Robb says. “It’s more at the margins, but it’s still significant at the margins.”

Complicating the process, Robb says young people don’t always un derstand the magnitude of debt.

This was certainly the case for Mischka, a Whitewater native, lo cated in southeastern Wisconsin. In high school, as Miscka worked for pocket change at Rocky Rococo and her single mother provided the necessities, even college application fees felt daunting to her.

So when she got her financial aid back and saw she qualified for loans and grants, a 17-year-old Mischka jumped at the chance.

Despite receiving the Pell Grant, Mischka, now 25, still has about

UW–Madison graduate Emerson Boettcher (right), who has over $20,000 in student loan debt, worked between 20 to 40 hours a week during college to help assauge her concerns about debt after college.$35,000 left in debt. She wouldn’t have done anything differently, but she wished she knew more when she said “yes” to loans.

“It’s just like this one button on a website that you click, and then they put money in your bank account,” she says.

For Faith, a debt forgiveness pol icy must balance precise targeting and easy implementation. Biden’s plan, she thinks, accomplished both of those feats.

Considering people who struggle the most with debt borrow less than $10,000, Faith says that number is addressed by offering relief of up to $10,000 for non-Pell Grant recipi ents. The boosted forgiveness of up to $20,000 for Pell Grant recipients also provides means-based relief.

But debt relief today doesn’t ac count for the big-picture problems in the student loan system — or future borrowers’ inheritance of it.

“A one-time forgiveness — it is problematic,” Faith says. “It’s hard for me to imagine a situation in which that could happen again.”

Robb says a one-time relief could also create perverse incentives — leaving people waiting for more debt forgiveness or causing them to take out more loans in hopes of addition al debt cancellation.

For borrowers like Mischka and Boettcher — who both received Pell Grants — Biden’s plan would be a game changer. Mischka would have her debt at least cut in half.

Under Biden’s plan, Boettcher would be debt-free. But if it gets axed, she would have to “rethink teaching entirely” — whether she could afford to do what she loves. Despite benefit ing from the forgiveness, Boettcher recognizes the long-term solution is not simple. All she has to do is think about her students to realize that.

“I look at my students now as they are prepping for college, and while I have this really amazing blessing, it’s like kids are still getting themselves into debt that they don’t know how to pay off.

“When’s the next solution? Is the next solution just another big for

giveness?” Boettcher says. “When are we going to really get to the eco nomic part of what’s causing this trouble in our system?”

The answer to Boettcher’s ques tion is, unsurpisingly, complicated.

Faith admits it is not a perfect analogy, but she asks people to think about the student debt crisis as a health care situation.

“We can stop the bleeding, but if we still have this wound, we need to figure out better ways to address emergency care and preventative care,” she says. “If we can do more on the front end to be more preven tative, then we can reduce the need for emergency care.”

For Faith, this means making stu dent aid more straightforward and reducing the amount that people borrow. Medicine number one, Faith says: increasing the value of the Pell Grant to help students better cover college costs.

Robb says making community college free would pave the way for people to start at cheaper two-year schools and transition into high er-cost institutions later — decreas ing students’ overall debt.

Additional means-based grant programs could also help minimize debt. For example, under the re cently implemented Bucky’s Tui tion Promise at UW–Madison, both Boettcher and Mischka would have graduated debt-free.

As the nation wrestles with the best ways to address student debt, borrowers hold their breath, waiting for Biden’s promise of relief.

But until her balance is down to zero, debt will remain on Boettcher’s mind and in her actions — like pick ing out a birthday gift for her 2-yearold nephew.

“I’m setting up a college invest ment fund for him,” she says with a chuckle. “I’m not giving him toys.”

Wisconsin native Justine Mischka (left) moved to Washington after her graduation from UW–Madison for an AmeriCorps job. She has about $35,000 left in student loan debt and joined AmeriCorps to help offset her debt through its grant program.Ulysses Williams takes a puff of his cigarette before he begins to speak.

“I was born and raised in the in ner city of Milwaukee,” he says. “I left and came here, was middle class for 27 years, and then I got divorced and everything went downhill.”

We’re sitting at a picnic table in front of the house where he’s been living for the last seven years. But before this place, Williams was liv ing on the streets of Madison.

“I was homeless. That was 2011,” he says. “I stayed homeless for 14 months, got a place and then, like usual, I lost my job. Back out on the street again, and that was 15 months out on the streets.”

Williams knows firsthand the hardships of being unhoused. It was those experiences that led him toward working on a solution that he hopes will make life better for those who are experiencing home lessness. It’s an idea that would give people who already have very little an extra bump, a step beyond mere survival to a place where they are protected and even given a chance to get ahead.

In May, Williams introduced a Homeless Bill of Rights to the City-County Homeless Issues Com mittee, a local government body made up of Dane County super visors, Madison alders and people tied to the area’s homeless commu nity. The document lists nine rights he hopes to protect, including the right to use and move freely in pub lic spaces, the right to vote, a rea sonable expectation of privacy of personal property, and the right to pray, meditate or practice religion in public spaces, among others.

The idea of a Homeless Bill of Rights is not unique to Madison or Williams; it’s something that activ ists across the country have cham pioned for years. In drafting his own Homeless Bill of Rights, Wil liams drew inspiration from legisla tion that has been passed in other cities and states. The proposal was recommended by the City-County Homeless Issues Committee and

Ulysses Williams, member of the Madison Wisconsin Homeless Union, is one of the leaders pushing for a Madison Homeless Bill of Rights.Williams says it’s under consider ation by the Dane County Board of Supervisors.

“The original goal for a lot of them was to protect people from being criminally punished for try ing to survive in public spaces,” says Eric Tars, legal director at the Na tional Homelessness Law Center.

In 2012, Rhode Island became the first state to pass a Homeless Bill of Rights, followed by Illinois and Connecticut. Other states like California and Oregon have passed more specific homeless rights legis lation.

In 2021, U.S. Rep. Cori Bush, a Democrat from Missouri, intro duced the Unhoused Bill of Rights, the first ever federal resolution for homeless rights. If passed, the bill would signify a federal commitment to solving the issue of homelessness.

Tars says these policies are a step in the right direction, but many had most of the stronger protections stripped out of them during the leg islative process.

Homeless Bills of Rights are de signed to protect people experienc ing homeless from discrimination based on housing status, something Williams says is common.

“America unfortunately has a history of discrimination,” he says. “Firstly Indians, then African Americans, then Jewish and Irish. They do have that history, and right now, it’s homelessness.”

He says he’s witnessed and expe rienced discrimination due to hous ing status many times, from see ing people being denied service at businesses to being removed from certain street corners. On one oc casion, Williams says he was hand ing out water on State Street when he saw a police officer clear out an entire group after seeing one person drinking alcohol.

“The police officer came up and of course he poured it out and start ed talking to them about, ‘Hey you guys come down here, you start fights down here, how about you guys start moving it out of here?’” Williams says.

He says he specifically included No. 8 on the list, the right to engage in lawful self-employment, because of discrimination he says he and others faced while trying to make some extra cash by collecting and recycling aluminum cans.

“The city made an ordinance that you cannot take it out of any trash containers,” Williams says. “Then all of a sudden, the recycling places, you cannot walk up and bring cans. You gotta be in a car, which, boom, it’s no longer possible to do.”

The other and perhaps more dire goal of a Homeless Bills of Rights is to eliminate the criminalization of homelessness by getting rid of laws against illegal camping and pan handling, among other things. In Dane County, an average of 13% of the annual bookings into the Dane County Jail are people who are pre sumed to be homeless.

“We all sleep, we all eat, we all go to the bathroom, we all enjoy being able to shelter ourselves when it’s too hot or too cold outside,” Tars says. “But those activities that all of us take for granted can become criminal acts if they’re done outside in some places.”

Offenses that begin with a fine can land someone who can’t afford to pay them in jail, which then be comes a barrier to finding housing and a job. On top of that, jail time

can trigger mental health issues.

“Even long after you might have been arrested, these fines and fees can follow you and make it impos sible for you to get housing or stay housed for potentially years after,” Tars says.

Pearl Foster, a volunteer, advo cate and member of the Madison Wisconsin Homeless Union, also recognizes the harm in criminaliza tion and says even small steps are impactful.

“We need as many things to pro tect our homeless population as we can,” Foster says. “So if that’s a Homeless Bill of Rights plus home lessness as a protected class and any other laws such as overturning some of the ones that already crimi nalize homelessness. We just need it all out there.”

Advocates agree that these poli cies are not working to solve the is sue and hope that a Homeless Bill of Rights will both provide protections and push policymakers to rethink how they approach homelessness.

“The hope is that by creating this new floor of rights, that the solu tions that communities will turn to will be actual constructive solutions that work for everybody, rather than just allowing public officials to push the problem out of the public view for their own convenience,” Tars says.

Ulysses Williams and Garrett Olson set up their Homeless Union stand at the farmers’ market in Madison to hand out free coffee and hot chocolate as a thank you to those who sign their petition for the Madison Homeless Bill of Rights.

Originally “Mekonsing” or “River Running Through a Red Place” the state is named for the Wisconsin River that cuts through the center of our state.

Our wetlands are abundant and our rivers run deep. Wisconsin holds more than 15,000 lakes while its rivers and streams cover more than 84,000 miles of terrain. To the east, Lake Michigan holds over one quadrillion gallons of water. Lake Superior’s three quadrillion gallons — the deepest and largest of the Great Lakes — sits to the north, while the Mississippi River follows the southwestern border.

As climate change, contamination and population continue to endanger the global fresh water supply, Wis consin’s freshwater becomes increas

ingly valuable. Places with fresh water will flourish as climate change shifts weather patterns and droughts become more common.

The state’s forward-thinking, cen turies-long connection to water has led Wisconsin to emerge as an unexpected leader in the fight for survival in the national water crisis. Leaders across Wisconsin are mov ing forward to keep the state at the forefront of water technology for decades to come.

Much of that work is happen ing in Milwaukee, located on Lake Michigan at the confluence of three rivers: the Milwaukee, Menomonee and Kinnickinnic. “Minwaking,” the Potawatomi word for “gathering place by the water,” brought Native

Americans to the area due to its rich land and location. The city’s proxim ity to water drew in water-intensive industries like brewing, tanneries, meatpacking and transportation — all of which drove water innovation in the 1800s.

Now, the city is home to more than 150 water-related companies like A.O. Smith, Badger Meter and Pentair; The Water Council; and the country’s only School of Freshwater Sciences at UW–Milwaukee.

The Water Council, a nonprofit or ganization in downtown Milwaukee, is dedicated to freshwater innovation and water stewardship.

In 2009, the same year the organi

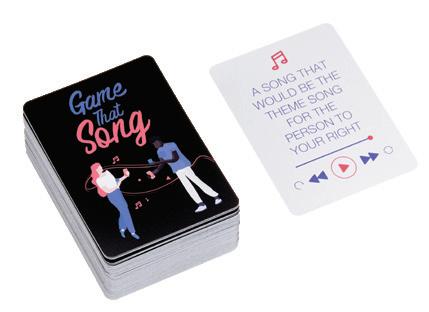

Milwaukee’s Lakefront Walk follows along the shoreline of Lake Michigan. Approximately 1.6 million Wisconsin residents get their water from the Great Lakes Basin.

zation incorporated into a nonprofit, the United Nations designated Mil waukee a U.N. Global Compact City — one of 13 cities in the world at the time selected for its concentration in a topic related to global health and development. The Water Council es tablishes a network of water industry go-getters by connecting businesses, utilities, government and innovators to bring water users into the future.

“It goes back 150 to 160 years ago,” says Dean Amhaus, president and CEO of The Water Council. “The breweries came in because of the access to the water, to the rivers, to the grains and the farms, and those breweries needed companies to help them process water ... It really goes back to producing beer.”

The UW–Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences found its home here for a similar reason: Milwau kee’s long-standing connection to water. Originally founded in 1966 as the Center for Great Lakes Studies, it is the only school in the entire country dedicated to the study of fresh water.

“Milwaukee has really been a force in research for a while and in educa tion and outreach on the Great Lakes,” says Rebecca Klaper, interim dean of the School of Freshwater Sciences.

The School of Freshwater Sciences has been a source of groundbreaking research in fresh water. Its program in Great Lakes Aquaculture research specializes in urban aquaculture. As ag riculture in the west becomes increas ingly endangered, the development of urban aquaponics has the potential to play a significant role in a new and expanding food revolution.

The school’s Great Lakes Genom ics Center is internationally known for its expertise in using genomics to address pollution concerns in fresh water. Their research consists of mea suring ecosystem health, identifying invasive species, sequencing corona virus strains in wastewater and more.

While Milwaukee has built a rep utation in the water industry, Wis consin itself can stand alone as a giant in fresh water. According to Todd Ambs, former deputy secre tary at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Wisconsin has 1,110 miles of Great Lakes shoreline and 5.3 million acres of wetlands. We have enough groundwater that if it were laid evenly over the state, it would be 100 feet deep.

For Ambs, what sets Wisconsin apart in water is our ability to man age it effectively.

“We’ve got some leaders in terms of how water management is done,” Ambs says, pointing to the Madison Metropolitan Sewer Districts, Green Bay’s wastewater treatment system and Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewer District’s work with both wastewater and habitat preservation and resto ration. “People that do this work for

a living will look to Milwaukee for some of the leading technology and efforts that are underway nationally.”

Ambs led negotiations for the state as the eight Great Lakes states creat ed the Great Lakes Compact, which bars any large-scale water diversions outside the Great Lakes basin. With Congress’s approval, former Presi dent George W. Bush signed it into law in 2008.

Shaili Pfeiffer, staff specialist at the DNR Bureau of Drinking Water and Groundwater Water Use Section, explains the heavy-handed policy as a means of water management.

“You can’t manage water if you don’t know what the water is that you have, and you don’t know who is using it,” Pfeiffer says. “So you need to know who’s using it, what they’re using it for and then how much they’re using.”

In Wisconsin, however, water pro tection policy has been common place throughout its history.

The state enacted the nation’s first shoreland protection law in 1965 and tackled the issue of pollution from lawns and farm fields in 1977, filling a gap in the 1972 Clean Water Act. In 1983, by achieving secondary treatment for all wastewater facilities in the state, Wisconsin was the first to meet the Clean Water Act’s interim goal for wastewater standards.

To keep waterways clean and ac cessible, water stewardship and water policy are critical. Dedication to free and public access to waterways is woven into the state constitution, declaring that all navigable waters are “common highways and forever free” to be held in public trust.

Wisconsin’s reputation for wa ter innovation and stewardship has primed the state as a leader in the fu ture of water. At The Water Council, the two go hand-in-hand.

Matt Howard, The Water Council’s vice president for water stewardship, stewardship means determining what needs attention, implementing the technology and then using the technology purposefully.

“We want to start working with businesses on the internal operation

... ‘So what are the best practices for operating a facility?” Howard says. “Then go out and find the right technology and right innovations to help you address those challenges or opportunities that we’re facing.”

One of the challenges that the country faces is the water shortage in the West. As a result of a 20-year drought the Colorado River is drying up, putting seven states, 29 federally recognized tribes and northern Mex ico all at risk of losing drinking water and electricity.

Howard points to the Colorado Riv er Compact, an agreement settled between the seven states and various tribes regarding water allocation, as the beginning of the end. While there have been technology implementations like smart meters and dams, the American

West has grown overly reliant upon innovation but ignored stewardship.

“If you don’t marry any of that with practice, you get yourself in a situation that they’re in right now,” Howard says.

There are several movements stirring in the West in response to the drought and water scarcity, but Wisconsin will likely have a hand in leading the country as a whole into a freshwater future. With Wisconsin’s leadership in pioneering water policies for centuries, The Water Council has had its eye on the West for some time.

“It’s around the quantity, but it’s also the quality of water,” Amhaus says. “So those companies [out West] have been doing that, and they will continue to do that as well. And we see ourselves as a solution provider.”

“People that do this work for a living will look to Milwaukee for some of the leading technology and efforts that are underway nationally.”

Debra Conway, a school psychologist at Vel Phillips Memorial High School, isn’t planning on leaving. But several of her colleagues have considered it.

The day starts for teacher Sally Watson before the sun rises. In the dark winters of Wis consin, it can be hard to rise before the sun, but this is what Watson’s been doing for 24 years. She’s used to it. She arrives at the high school over an hour before her students arrive to get organized for her day.

Watson teaches five classes a day. The remaining hours of her time at school are spent adjusting lesson plans, attending meetings and call ing parents whose kids are strug gling. By the end of the school day, she’s tired from wrangling ninth graders, who she often thinks act more like elementary schoolers than high schoolers.

She leaves school around 4 p.m. and spends the next two hours work ing from home: planning lessons, grading, reading and responding to emails. She spends from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. with her young children, and once they’re in bed, she spends about two more hours working.

The next morning, the cycle re peats. She’s thinking about quitting.

Watson, who asked for anonym ity because she’s not allowed to speak publicly about her role, is not alone. Teachers across Wisconsin are in difficult positions and are faced with hard decisions — they’re trying to endure and persist in the profession, but each day, the chal lenges seem harder to withstand. Many have already left their careers in education behind, contributing to the growing teacher shortage.

Teachers have always been valued community members, appreciated for their role of educating the next generation. Today, their roles have expanded, but the respect and sup port that was once provided by their communities has all but vanished.

Thomas Burkhalter, superinten dent of Viroqua Area Schools, has seen this trend over his time in ed ucation. At one point, teachers were revered in their communities and thanked often for their work, Bur khalter says. Now, he says things have completely shifted.

Many parents and other com munity members feel emboldened to criticize teachers and teach ing methods. Public school board meetings often give a platform to community members who are an gry with teachers.

“Some of the other things that are said at those meetings are just hurt ful,” says Amy Menzel, who was an English teacher at Waukesha West High School. Menzel, along with many colleagues, left Waukesha public schools after the 2021-2022 school year. “They say that they de mand respect in those [meetings], but I don’t see enforcement of that,” Menzel says.

Many politicians haven’t been supportive either. For several weeks in February 2011, thousands of teachers protested the budget repair bill at the state Capitol building in Madison. Act 10 became law not long after the protests. When Act 10 was passed, teachers and other public sector employees lost much of their ability to collectively bar gain. Teachers are still affected by it today.

Additionally, gerrymandering in the state has made change nearly impossible when it comes to elect ing politicians who prioritize school funding, according to Watson.

“ We have not properly funded public education,” Watson says. “We’ve kept things static even though inflation has gone up.”

With lack of funding for edu cation comes lack of resources in schools. Teachers are often left to pick up the slack.

At Vel Phillips Memorial High School in Madison, school psychol ogist Debra Conway frequently sees student needs that require more re sources than the school has to offer. To her, that’s the biggest challenge of working in a comprehensive ur ban high school.

“It can be a mental health need, it can be an academic need, it can be a social-emotional need, it could be a feeding need, it could be a housing need, it could be a clothing need,”

Conway says. The lack of resources doesn’t stop teachers from trying, though. It can be exhausting, but many teachers really care — enough to take work home and continue trying to meet student needs. Wat son does this almost daily.

“That’s what I’ve been doing for two years,” Watson says, “and that’s becoming unsustainable.”

Conway agrees. “It’s hard because you want to be the be-all-end-all for

Menzel says. “It put a lot of stu dents’ safety in jeopardy, perceived or otherwise.”

Even in more progressive dis tricts like the one in which Watson works, teachers are seeing a trend of identity being politicized.

“Books and things being pulled are often books that deal with issues of equity, whether it’s LGBTQ+ identity or racial identity or reli gious questioning,” Watson says.

Kids are already having these con versations about race and gender, and Menzel says it’s her job to help them do it in more effective ways so that they feel seen and heard.

“I don’t think we get better at talking about tough subjects by not talking about tough subjects,” Menzel says.

everybody, but you can’t,” she says.

Teachers, like students, are expe riencing their own mental health crises. Working more than 40 hours a week in an environment where teenagers are screaming at you and throwing things — yes, really, ask Watson — is draining, and no one allows teachers the time to recharge.

In fact, teachers say they have less time than ever these days. The time they don’t spend with students is also monopolized by administrative tasks, such as filling out forms or creating online lessons.

“My struggle with it is that it’s al ways a little more, a little more, a lit tle more,” Menzel says. “Now we’re at the point that it’s overwhelming.”

While teachers are being given more responsibilities in their class rooms, at the same time they are being stripped of their autonomy. Not only are books being pulled from the curriculum and libraries, but some districts have gone as far as to require teachers to take down any signage in their classrooms that could be deemed “political.”

At Menzel’s former school, staff were told to remove pride flags from their walls. According to Menzel, many teachers took issue with that request, including herself.

“I think it emboldened students to say things that were hateful,”

What does a community do when teachers are leaving? The consensus is simple: Trust teachers again.

It can be hard to trust even a qualified individual when everyone feels like they’re an expert.

“I think we’re one of the most unique fields because everybody went to school, so everybody thinks they know how it should be done,” Burkhalter says.

What the criticism of teachers is doing, Burkhalter says, is down playing the amount of training, ef fort and time that professionals in schools have gone through.

“Districts don’t trust teachers,” Watson says. “School boards, fami lies, voters don’t trust teachers.”

Menzel speaks similarly about trust. “There’s a lack of trust in what [teachers] have dedicated their lives for,” Menzel says.

Even Conway, a school psycholo gist, says “It’s hard, and it’s real. It’s hard not to take it personally.”

“We’re expected to provide for those needs and it can be overwhelming and hard to do.”

Royle Printing is proud to support the University of WisconsinMadison School of Journalism and Mass Communication and all contributing students who produced Curb Magazine.

If you’re looking for a challenging and rewarding opportunity to grow, look no further. As part of our growth, we’re looking for recent graduates to join our team! The neat thing about us is we’re an independent, family-owned business with zero debt. Visit www.royle.com for more information!

There’s something about art that makes you feel warm and enlightened — even when it’s 8 degrees below zero.

Art can be viewed from anywhere by anyone. It propels the human ex perience by telling a story in many forms, leaving us with perspective, appreciating what we knew before and what we just learned.

“Art is a wonderful educational tool that aids in the understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Art provides the viewer with new perspectives on life and new ways of thinking and seeing. It serves as a jumping-off point for inspiration and new ideas. Art enriches and en hances the soul,” says Avery Pelek oudas, Warehouse Art Museum pro gramming coordinator.

Exhibitions around Wisconsin offer various pieces that can be en joyed this winter.

Olbrich Botanical Gardens, locat ed on the north shore of Madison’s Lake Monona, includes 16 acres of outdoor display gardens and a 10,000-square-foot conservatory. It also features year-round art exhibits.

Olbrich’s annual Holiday Express, Flower & Model Train Show will be open from Dec. 3 to Dec. 31. The ex hibit is unique as it involves special designs with plants and a new theme every year — this year’s embodying carnival. In addition, the exhibit cre ates tradition, welcoming back fami lies and visitors.

“It’s a great place for anybody to just get away and relax, whether it’s from school, work or other life stresses,” says Missy Jeanne, Olbrich Gardens’ special projects manager. “We see familiar faces all the time of people enjoying [our] classes and workshops for all ages. Some are more art based, some are based on plant biology, it’s just kind of end less, all the different ways that you can learn and engage.”

A barber chair with leather and gold plating on display at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art is part of Faisal Abdu’Allah’s exhibition called “Dark Matter.”

The Madison Museum of Contem porary Art, known as MMoCA and located in downtown Madison, dis plays the work of a variety of artists and professors from UW-Madison. MMoCA has an exhibition of pieces from UW–Madison professor Faisal Abdu’Allah known as “Dark Matter.” It portrays cultural representation and shows Abdu’Allah’s most cele brated works.

Along with “Dark Matter,” which will be on exhibit until April 2, 2023, art by Wendy Red Star, an Apsáa looke (Crow) contemporary artist, made its way to the museum on Nov. 12. Red Star’s work offers accounts of American history that rectify the frequently flawed narratives about Native American people.

“It’s really about starting conver sations and having more meaning ful conversations with children that may not know how to approach the conversation of the histories that are missing in our textbooks, but this is a supplement that will give kids that moment with their families,” Brun gardt says.

In the winter, Lake Geneva hosts the annual Winterfest, which runs from Feb.1 to Feb. 5.

“[There is] a lot of communi ty pride in hosting this event,” says Deanna Goodwin, vice president of marketing, communications and development for VISIT Lake Gene va. “It’s so incredible. The crowds of people that come here and how hap py everybody is when they’re here. It’s a lot of work leading up to it, but it’s fun work.”

For nearly three decades, Lake Geneva’s Winterfest has hosted the annual U.S. National Snow Sculpt ing Championship. Fifteen teams of three people from around the U.S. participate in three days of craft, where they create 10-foot sculptures along the lakeshore. After sculpting, the final result is an art gallery of lakefront sculptures for the commu nity to enjoy.

“Winterfest is so larger-than-life when it happens. And to see so many smiling faces and kids in awe of how big these sculptures are because you get up really close to them,” Goodwin says. “You’re just within a couple feet of them actually working and doing the sculptures. And then when you see it all said and done in the detail, in the artwork, it’s just phenomenal.”

The Warehouse Art Museum, called WAM, opened its doors in 2018. Located in a historic ware house in the Menomonee Valley, the mostly woman-run museum show cases three to five exhibits every year. The artwork on display is all from the private collection of the co-own

ers and co-directors of WAM, Jan Serr and John Shannon.

“They have been collecting for about 40 years or so, and that’s essen tially why they created WAM, was to display their collection because they had so much work sitting around,” says the museum’s programming co ordinator Avery Pelekoudas.

From Jan. 13 to March 31, WAM will showcase art by Ruth Groten rath, a Milwaukee local.

“It’s gonna be super bright, col orful, fun ... we like to do that for the harsh gray Wisconsin winters,” Pelekoudas says. “So having a fun, colorful show during that time is always nice. Yeah, that’s one of the main draws for the exhibition during the winter.”

The difference between au thentic and imitation vin tage clothes depends on one thing: the stitching.

A single stitch at the hem and shoulder was the standard up until the mid to late ’90s, while a double stitch is the standard of today. It should be no surprise that Singles titch in Madison is the top shop for authentic looks of the past.

Mitch Hammes, also known as Single-Stitch Mitch, is the 22-yearold from a small town right outside of La Crosse on a mission to redefine how we shop and dress. Hammes opened Singlestitch in Madison in 2021, and it already sticks out from the rest.

Sales and hard work made Hammes successful, but his passion for recycled fashion and community is what has made him Madison’s king of vintage.

Vintage wear and secondhand shopping have exploded in the past 10 years.

“Whether it’s skateboard culture, sports culture or any of that ... it kind of all just stems from vintage,” says Joel Bergquist, manager and creative consultant at August, another State Street shop.

Another factor in the appeal of secondhand pieces is their individu ality. Many vintage items or clothing lines are either discontinued or are limited-release pieces. To many, this drastically raises the value of a piece.

This is the background to Hammes’ success. He has been thrifting since

he was a little kid, when his grand ma would take him to garage sales on Fridays and Saturdays.

Hammes is certainly the guy to rule over Madison’s vintage-wear market, but the timing is what made it work. The market wouldn’t have been ready for his passion just five years ago.

After high school, Hammes start ed selling clothes at garage sales. He says he had to “lug probably 800 to 1,000 pieces of clothing up and down a flight of stairs, plus all the clothing racks. And it got to the point where I was like, ‘It was either a storage unit or a store.”

Hammes chose the store.

A small space in La Crosse, on a remote street with just a gym next to it, was home to his very first store front, Lax Vintage, which did not match the ornate, hyper-detailed layout of Singlestitch.

“When we opened we had plastic hangers, Walmart clothing racks,”

he says. “Racks would fall down and break. It wasn’t a pretty sight at all, but it just worked.”

This is funny because Singlestitch’s design has incredible attention to detail. Every inch of the store, floor to ceiling, is covered in colorful vin tage trinkets, hats, shoes, T-shirts, jackets, pants, beanies, vinyls, maga zines, VHS tapes, overalls, sweaters, toys, banners, coats, video games and more. To a vintage lover, it is an adult candy shop.

Every rack that lines the walls and middle of the store is color coded and organized by garment. Above every rack is seemingly a collector’s item from the 1980s to the early 2000s, and just about anything you see in the store is for sale — if the price is right.

Hammes’ attention to every detail and to the curation of a timeless ex perience keeps people coming back.

Though Singlestitch is an upgrade from Lax Vintage, people will go

Mitch Hammes, owner of the Madison vintagewear shop Singlestitch, sits atop his throne of unreleased inventory. His neatly organized basement storage is home to nearly double the amount of items on display up in the store.

wherever Hammes is. Grace Paar, a senior at UW–Madison, is one of the few who have been to both store fronts. Even with the plastic hang ers and Walmart racks, Paar says, “People that were in there were very trendy ... and I was like, I need to dress nice to go in there.”

Hammes sets the tone wherever he is. Instead of creating competition between other stores in Madison, he made professional companions. Take Supra Sneakers, a “hypebeast” store selling high-end, street footwear just three doors down from Singlestitch as an example.

Jason Foss, who runs the store, says he and Hammes are friendly with each other and share ideas for their customers.

“We bounce off each other a lot,” Foss says. “A lot of times people look for shoes, [and] whenever they don’t like some of our shirts, we send them over there.”

The two even talked about setting

up a side-by-side shop in a new place.

Hammes does not only show compassion to his competitors, but his customers as well. His goal is to break away from the hierarchy of the producer over the consumer found in traditional retailer spaces.

“If you’re talking to somebody else who’s behind a counter, they will al ways be up on a podium,” Hammes says. But, “when you can sit down with somebody on the same couch and talk ... it’s totally different.”

This philosophy goes into Hammes’ plans for future expansion. Singlestitch is closing a deal on a sec ond shop in La Crosse and Hammes hopes to upsize his Madison loca tion. While expansion is necessary for Hammes’ incredible amount of inventory, he also wants to do it in order to provide a comfortable space for the community.

Another feature that would accom pany expansion would be a space for styling, which interests Hammes.

“Once I get to realize what people are collecting, what people are into, then I can kind of like go out and purchase items for them that I prob ably normally wouldn’t have picked up,” Hammes says.

Hammes and Singlestitch are al ready thriving after just one year, and it seems the passion and care he feeds into his business will only make this success more sustainable. His work is for the community, just as much as it is inspired by it.

“That’s why I do this, still, to this day. I do this to see other people,” Hammes says. “That’s probably my style ... It’s just stuff that I see throughout the day, it’s just seeing how people dress and trying to put my own twist on it.”

By Brooke Messaye

By Brooke Messaye

Being from California and choosing to come across the country to Wisconsin for college means I am con stantly being questioned about why I chose UW–Madison. After spending the last three and a half years in Wisconsin, I have fallen in love with this state and proudly respond to all the typical questions.

When I first thought of Wisconsin, I can admit my mind went to the typical country view of an expansive field with a red barn, like what you see on the side of a milk carton. While there is plenty of that, Wisconsin is so much more. With Madison’s four major lakes and a vast number of state parks, such as Devil’s Lake, the views are amazing. The Wisconsin Dells is also the “Water Park Capital of the World.” And let’s not forget that Milwaukee is a huge city with tons of opportunities and experiences at the tip of your fingers.

Yes, yes I do, and being in the cheese state has both expanded my cheese palate and provided me opportunities to do some really cool things, like milk a cow at Hinchley’s Dairy Farm. After living in Wisconsin, my favorite food is now fried cheese curds. That’s something anyone who visits must try. I am a proud cheesehead — and yes, I do own that cheese hat.

Ranked as one of the top five party schools, I can admit that UW–Madison students definitely “get lit,” but they also know how to pick themselves up and show out in the classroom. Drinking is a part of the culture in Wisconsin, so of course that carries over to the university. But just as we rank well on the party scale, we also rank well academically as the No. 10 public school in the nation, according to U.S. News.

As a huge sports fan, Wisconsin sports always hype me up. With the recent success of the Bucks as the 2021 NBA champions, the notoriety of the Packers with the most NFL championships in the league and the Badgers as a POWER HOUSE for college volleyball, it is no surprise that people who may not know much about Wisconsin immediately think about sports.

“UW–Madison, you must be a partier.”

“Go

My first encounter with race was at the age of six years old while attending elementary school in the Milwau kee Public Schools system.

Sitting in my kindergarten class room, I watched a group of girls rush towards a pile of dolls during playtime. After all the dolls were taken and the only Black doll was left in the corner, I walked over to grab the doll and asked one of the girls if I could play.

She said no; that the Black doll was on timeout because she was be ing bad just like me. The only thing was, I had never been on timeout before, and I was not bad.

The pulse of Wisconsin is traced with the controversial history of race relations that have been skewed by the lack of documentation and mis information across the state. Black Wisconsinites have been at the fore front of racial injustice, segregation and voting discrimination since the mid-1800s and continue to address

these matters through resistance.

To really understand this past and how it will affect our future, I set out to find where the pulse of history in Wisconsin for marginal ized individuals truly comes from. My journey began at the Wisconsin Historical Society in an interview with Lee Grady, the senior refer ence archivist.

Grady’s work in the archives in cludes providing access to legisla tive papers, photographs, business documents and personal, govern ment and public records from peo ple with local to elite status that dates back to when the state was established in 1848.

“We’ve tended to do a better job of documenting underrepresented communities and people of color, and it’s been better and better as time goes on, but we were not very good at it for the first 120 years of our history as an organization,” Grady says.

Over its nearly 175 years, Wis

consin history has been told from a narrow white male perspective.

“Most of the records are the per spectives of missionaries of govern ment officials, French fur traders and not from Indigenous peoples themselves,” Grady says.

Grady shared the story of Ezekiel Gillespie, an African American man who attempted to register to vote in Milwaukee in 1865 and was denied the right to vote by county officials. He challenged the courts under the provisions of the constitution and won a state Supreme Court case al lowing Black men in Wisconsin to vote in 1866.

UW–Madison’s Public History Project opened its exhibit “Sifting & Reckoning: UW–Madison’s His tory of Exclusion and Resistance” on Sept. 12, 2022, at the Chazen Museum of Art.

The exhibition recognizes gener ations of students at UW–Madison

who have been involved in move ments on campus and addresses the university’s history of racism and exclusion of its minority students.

Kacie Lucchini Butcher, the di rector of the Public History Proj ect, explains how engaging with the university’s history impacts her and everyone residing in Wisconsin.

“It’s gonna be really important for us as a university and a campus community to think not only about the role that these histories play in Wisconsin, but really in our com munity, where we live, how we’re going to make sure that we don’t repeat these histories in the future,” Lucchini Butcher says.

The exhibition spans over 175 years of history in Wisconsin and highlights hundreds of stories of struggle and resistance at the uni versity and in the Madison com munity. Through archival material, photos and oral histories, the exhib it showcases what students of color have been going through at the uni versity from the past to the present.

Standing in the exhibition sur rounded by the university’s dark past of discrimination and racism, I felt displaced in my identity of what it truly meant to be a Badger.

As my peers gathered around the exhibit, exposure of generations of injustice in UW Housing, athletics, Greek life and student engagement reflected years of students at odds with the university and its policies.

“Madison believes itself to be the mecca of Wisconsin, in that the folk in Madison think they’re so woke and so educated and they know ev erything there is to know about rac ism, but I think this will show them that they have a lot more learning to do,” says Grace Ruo, a native of St. Louis and First Wave Scholar at UW–Madison.