pause/play art communities in migration part 2

✳

…This was the time when chatGPT, artificial intelligence user-friendly instruments, machine learning tools, and research projects became not only hype but mainstream, the reality of everyday life. This was the time when war and geopolitical conflicts became a dramatic everyday reality for many people in several countries. The dichotomy of the groundbreaking new technologies and the medieval acts of war show one of the main peculiarities of the current state of humanity - technological development has accelerated multiple times, while the global paradigm of the existing socioeconomic models still lives the life of the previous centuries.

Most new “transformative” technologies have appeared because of practical necessity and scientific research, often, but not necessarily, connected to the military, the space industry, or big corporations’ needs. Technologies themselves are multifaceted things, and besides their direct functionality, they are defined by the particular state of cultural, social, and political circumstances of the time of creation. Here, we can refer to the philosophical tradition of techno-anthropology, in which we should mention Donna Haraway’s well-known concept that “technologies are not neutral”1, but also emphasize how technologies shape our interactions with them. The

design of interfaces and the underlying operational logic inevitably influence users to unconsciously perceive the world through the cultural and political contexts in which these technologies were developed, embedding coded elements within their functionality.

At the same time, it is often believed that the mission of contemporary artists is to deconstruct new technologies, to misuse and hack them, often in a way that helps to create a critical reflection of social and political issues.

Issue #56, June 2014

*Boris Groys. On Art Activism. e-fluxJournal,

“Modern and contemporary art wants to make things not better but worse — and not relatively worse but worse:radically to make thingsdysfunctional out of functional tothings,toexpectations,betray reveal the invisible ofpresence death where we tend to see only life”.

technologies enemies, tools or collaborators for you?*

*from the survey with participants of the Pause/Play Culture under Pressure project 2024

█ enemies tools collaborators

From here, we face a contradictory situation — keeping in mind that the nature of every technology we use is already determined by the social, political and cultural context of its creation, the question is whether there is a real possibility of “hacking” the technologies and utilizing them in activistic/ political, artistic practices, without being simultaneously ethically compromised by the very way the technologies function by their nature. ✳

In this article, we will try to contextualize and test several ideas about how and whether new technologies

2 The term Global Village was first coined by Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan in his essay “Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man” (1964)

bring fresh possibilities to social and political artworks. A special focus will be given to media art practices, in which artists use (or intentionally misuse) digital technologies for projects reflecting and rethinking war and conflicts.

✳

Living in the epoch of the “electronic village”2, it seems logical to suggest that digital technologies and their utilization in the art realm have made it possible to broaden the potential reach to the general public. This leads us to the hypothesis that artworks utilizing new technologies have greater chances of being more effective when engaging with the topics of social changes and politics.

✳

And here comes a widely discussed and controversial methodological question — what to consider as political art in times of extreme political tension. We witness the invasion of political and social contexts in the cultural field on almost every level. But political systems and ideology in countries with oppressive regimes, and those involved in geopolitical conflicts, often make artworks unintentionally political, just out of the circumstances. This redefining of the artwork’s meaning to a political one frequently leads the author to prison (for example, in Russia or Belarus) but not to revolution or changes (the ideal aim of activist art). In other circumstances, the same artwork viewed with different backgrounds could be considered moralistic, hypocritical, if not meaningless.

I asked the same question to different agents. Most of them are humans, but one is – artificial.

Here’s the question: IN TIMES OF WAR AND CONFLICTS, DO YOU BELIEVE IT’S NECESSARY FOR CONTEMPORARY/MEDIA ARTISTS TO BE MORE ENGAGED WITH POLITICAL AND SOCIAL DISCOURSES THROUGH THEIR ARTISTIC PRACTICE?

“Artists can and should do whatever they want, regardless of political circumstances. It is never a good idea to force artists into a role or to impose a moral code. That said, artists have often addressed political matters, and those who work with new media have been particularly inclined to do so. I find artistic approaches that cross the boundaries of defined practices particularly interesting. While many works of art often function as an echo chamber of the horrors reported by the media, there are others that dare to try more impactful approaches. Artists can show us another side of the story and perhaps even offer us a way to intervene as protagonists in the course of history.”

“I believe that art, and media art in particular, is always political. But when we say that art is political, it is not only that art has a political agency. Sometimes, it has become a victim of politics. Talking about the Russian context, I remember very well when media artists used technology and media environments to resist the regime and in the 90s-beginning of 2000s they easily reached the masses. Today, it is very challenging for critical artists who stay in Russia to make engaged, political, and activist projects because there is no gray area

anymore. They have to be careful not to put their lives in danger. However, artists who are not in physical danger should also be careful, but in a different sense. I am almost angry about current media art projects by artists from Russia, which are just attractions. For a long time, art has tried to tell us that we are living in a computer game. The game must be over.”

4 // Answers from the survey with human agents: participants of the Pause/Play Culture under Pressure project 2024

Yes, but only if you have a real craving to do it rather than doing it feeling that you are urged to make a statement if the artist is active and considers the art practice as a way to speak with society - yes

Depends on the practice It depends

New media artworks that consciously act on political and activist territory have a long history. Regardless of media, when it comes to artworks reflecting conflicts and wars, artists choose different strategies. Most of the time it’s the format of critical reflection or subjective commentary, which often rehearses the positions that already exist in the media. In some other cases, artists take on the role of proposing a potential space for the critical discussion or they create speculative or alternative narratives, which don’t necessarily mean contribution to the social debate, but make it possible to change the optics.

✳

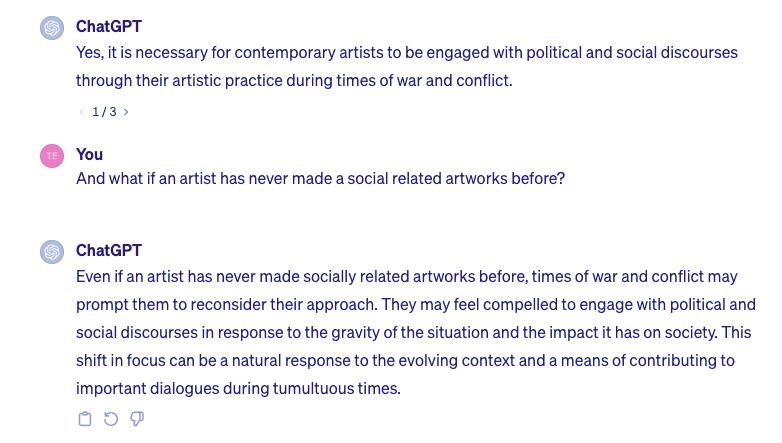

One early example of new media artwork reflecting military conflicts is Random War by Charles Csuri. The birth of this seminal, pioneering work of computer art was in 1967 at the time of hot debates around the Vietnamese war. I find Csuri’s artwork particularly interesting due to the fact that Charles was a witness and active participant in the war; he served in the U.S. Army at the end of World War II in Belgium.

In his piece, Csuri creates a simulation of a war battlefield, where life, death, and medals are assigned to soldiers by the pseudorandom number generator.

Random war (1967). Charles A. Csuri

c Charles Csuri Archive (https://www.csuriproject.osu.edu/Detail/objects/539)

3 https:// csuriproject. osu.edu/

The artist simulated a microcosm of the battlefield with the program, which randomly generated numbers, not only determining the position of 400 toy soldiers in two armies, but also deciding the destiny of the soldiers according to the following groups (1) Dead (2) Wounded (3) Missing (4) Survivors (5) One Hero for Each Side (6) Medals for Valor (7) Good Conduct and (8) Efficiency.3

Choosing these 8 categories that depict the formal essence of the war process in relation to a single human (soldier), the artist created an artistic work of symbolic war acts, mirroring the realities of war, where mathematical randomness and chaos are often the destiny. At the same time, rather than depicting humans, the artist has chosen frozen toy figurines of soldiers, alluding to the prevalence of battlefield imagery and warfare in childhood games. These endless toy soldier kits, ubiquitous in children’s stores, subtly condition an acceptance of war as a norm from an early age. The Random War is not only a critical commentary on the chaos of all wars, but it also reflects the cruel nature of military intelligence technologies, where computer simulations of battles within certain circumstances are “played” by the militaries before executing the real battles in modern warfare.

Csuri’s artwork predated the advent of computer games, in which warriors and soldiers played the main roles.

4 https:// totalrefusal. com/

Later, when the gaming industry had gained impressive popularity as a part of the entertainment industry, it became an arena for endless artistic experiments.

For example, the well-known art group Total Refusal (Robin Klengel, Leonhard Müller, and Micheal Stumpf), who call themselves Pseudo-marxist media guerillas4, appropriate contemporary video games to criticize the capitalist system, and work with social and political narratives. The art group has gained quite unprecedented recognition for activist artists working with digital media; their films and videos have received over 50 awards and honorary mentions since the group’s foundation in 2018.

How to Disappear (2020) is a short film by Total Refusal which was created in the picturesque landscapes of the shooter computer game Battlefield V. The story here is performed in the realms of the game, and essay-like narration depicts the history of the deserters, while the protagonist makes melancholic, yet desperate attempts to leave the digital battlefield, to run away, or, at least, not to fight. The narrator deconstructs the history of war fueled by nationalistic ideas, analyzes a figure of a deserter, both in digital, and real life, and highlights the act of desertion, which is treated as taboo by society, while the protagonist tries to break the framework of the game’s algorithms, which exclude the possibility of leaving the battlefield.

The film is produced in a highly aesthetic form, shiny and glossy, and makes the whole piece a digital spectacle, a performative act of hypnosis, while storytelling about the deeply disturbing topics of the

5 Here, we can refer to the ideas developed by Walter Benjamin (“The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935) and Guy Debord (The Society of the Spectacle (1967)

rules of real wars. This type of aestheticization and spectacularization of politics5 often becomes a territory for criticism of socially engaged art, due to its failure to bring people to actual actions, instead offering an aesthetically appealing interpretation and trendy, entertaining, philosophical spectacles philosophical spectacles.

“The art ofcomponent art activism is often seen as the main reason why this activism fails on the levelpracticalpragmatic, — on the level of its immediate social and impact.”political Boris Groys. On Art Activism. e-fluxJournal, Issue #56, June 2014

The approach of utilizing the game industry for anti-war artistic performances is not new; in previous years, artists like DeLappe (dead-in-Iraq, 2006-2011) and Eva and Franco Mattes (Freedom, 2010) developed similar scenarios. However, in my opinion, in the How to Disappear film, the artists managed to create a metanarrative which elegantly abuses game mechanics, while making a critical investigation of the ideology of war and the figure of a soldier.

When it comes to activist art, it is believed that public art and participatory types of artistic practices are much more effective than any others. Indeed, interventions in public spaces can engage with a broader audience and sharpen reflections on political issues. In this regard, it would seem that the development and accessibility of consumer augmented reality (AR) technologies have opened up new possibilities for digital public art projects. Akin to classical street art, AR adds a new “layer” to the reality of existing public spaces. The use of AR appeals to the romantic, science-fictionesque idea of altering the physical world and melting the physical and digital into one.

Yet, despite being seemingly powerful for public interventions, this technology doesn’t bring about many successful activist projects in the art field. There are some recent examples of critical AR projects in the Russian art community, for example, the Seven Deadly Sins of Russia and the AR Hunter project by Yar art group. Amongst other examples I would mention Hack the Patria by Venezuelan activists, and the Berlin-based

6 https:// hashdox.org/

Refrakt art group, which reveals hidden messages on voting ballots. But in my opinion, AR technology has several quite serious limitations that prevent its popularity among artists working in social contexts. This includes the nature of the experience it provides — highly individualistic and confined to the smartphone screen. And secondly, the discriminative technical barrier: people without the latest models of smartphones are simply excluded from experiencing such artforms. ✳

When speaking about modern warfare, it’s often said that contemporary conflicts are not only happening on the battlefield but that we are experiencing the first full-scale cyber and information war in history. In this regard, I find the art project Hashd0x [Proof of War], which was created by Egor Kraft in the first year of the Russian invasion of Ukraine (2022), very inspiring. The artist, and fellow developers, offer a prototype of the app, primarily based on blockchain technology, which, as claimed by the authors, “makes it possible to record and verify the authenticity of still and moving images”.6 The project is presented in the exhibition halls in the format of a multimedia installation and deals with one of the most important topics nowadays – strategies for verifying information and resisting misinformation. Even though, technically, I can see certain potential issues in realizing the app in the way the authors suggest, the artwork gives another perspective and offers speculative tools for information warfare that could potentially alter the principle of misinformation dissemination.

Technologies are an ingredient that help artists create powerful and thought-provoking artworks in times of political tension, wars, and conflicts. I believe that different voices in the art field, helping people engage in the realities of the current, highly dramatic times, and at the same time, generating speculative scenarios of a possible better future, are vital, regardless of their most likely impotence in bringing actual social changes and political actions. At the same time, I believe it’s important to mention that this territory requires extra sensibility in many aspects. It is important to always check and recheck the context and the relations of the ideas to the context and to be honest and to be brave with the honesty.

(please answer shortly and correctly)

1 Published in the book “Whistleblowing for Change: Exposing Systems of Power and Injustice”, Tatiana Bazzichelli, ed. transcript Verlag, 2021.

2 WikiLeaks’ “9/11 tragedy pager intercepts” is visible at https://911. wikileaks.org. The project is rebroadcast in real time on subsequent 9/11s. Read more in the article:Declan McCullagh, “Egads! Confidential 9/11 Pager Messages Disclosed”, CBS News, November 25, 2009, https://www. cbsnews.com/ news/egadsconfidential-911pagermessagesdisclosed.

3 In May 2013, in the context of the yearly programme “reSource” that I was curating at the transmediale festival, I organised with Diani Barreto and with the support of the (later named) Chelsea Manning Initiative Berlin, the panel “The Medium of Treason. The Bradley Manning Case: Agency or Misconduct in a Digital Society?” at the

This is an extract of Tatiana Bazzichelli’s text “INTRODUCING ART AS EVIDENCE: THE ARTISTIC RESPONSE TO WHISTLEBLOWING”1

✳

The time frame from 2009 to 2016 was a crucial period of collective experiences towards the formulation of artistic practices in relation to whistleblowing. In this period of time, close networks of trust were established around this topic, rooted in WikiLeaks’ activities, which pushed the boundaries of what is correct to publish, and what could count as art.

✳

In November 2009, WikiLeaks published 570,000 confidential 9/11 pager messages, documenting over 24-hours in real time of the period surrounding the September 11, 2001 attacks in New York and Washington. The archive showed US national text pager intercepts of official exchanges at the Pentagon, FBI, FEMA and New York Police Department, and from computers reporting faults at investment banks inside the World Trade Centre.2

✳

In 2010, the publication of Collateral Murder and the Afghan War Diary, anonymously disclosed by Chelsea Manning to WikiLeaks, as well as the WikiLeaks release of top-secret State Department cables from US embassies around the world, signalled the start of a specific period of time in which artists, hackers, activists, researchers, and critical thinkers engaged extensively with the formulation of new forms of technological resistances and artistic critique.3

✳

Three years later, Edward Snowden’s disclosures of National Security Agency documents have changed our perception of surveillance and control in the information society. The debate over abuses of government and large corporations has reached a broad audience, encouraging reflection on new tactics and strategies of resistance. Whistleblowing, leaking, and disclosing have opened up new terrains of struggle.

✳

What is the artistic and activist response to this process? How is it possible to transfer the surveillance and whistleblowing debate into a cultural and artistic framework, to reach and empower both experts and non-experts?

Urban Spree Gallery in Berlin. This event revisited the making of the Collateral Murder video and discussed the “United States v. Bradley Manning” trial on June 3, 2013. The video of the panel with Andy Müller Maguhn, John Goetz and Birgitta Jónsdóttir is available at: https://archive. transmediale. de/content/ resource-005the-mediumoftreason.

4 This happened during the process of our sharing for the organisation of the keynote “Art as Evidence”, about art and the NSA surveillance at the transmediale festival at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin on January 30, 2014, https:// archive. transmediale.de/ content/ keynote-artasevidence, which is described in depth in the following interview with Laura Poitras in this book. Af ter this transmediale festival edition, I again connected thetopic of art and whistleblowing curating the exhibition “Networked Disruption: Rethinking Oppositions in Art, Hacktivismand Business”, which opened in March 2015at the ŠKUC Gallery, in Ljubljana, Slovenia, expanding the subject of my previous book (Networked Disruption, 2013)into the practices of whistleblowing and

The objective of this chapter is to introduce the concept of Art as Evidence as a framework to describe artistic and hacktivist practices able to reveal hidden facts, to expose misconducts and wrongdoings of institutions and corporations, to produce awareness about social, political and technological matters that need public exposure, and in general, to inform the reality we live in. Art becomes a means to sensibilise about sensitive issues, generating an in-depth analysis within the framework of social and political action, as well as hacktivism, post-digital culture, and network practices. ✳

The framework of Art as Evidence is presented in this essay as a context of artistic exploration, in which the issues under scrutiny are investigated in their imaginative artistic potential by questioning the concept of evidence itself. The main tactics are not only the disclosure of information and provoking of awareness through artistic interventions, but also encouraging the imagining of alternative models of thinking and understanding which lead to the creation of new imaginaries by playing with the “unexpected”, a methodology that has been at the core of artistic experimentation since the Avant-garde, which introduced the use of shock and estrangement as artistic practice.

✳

This chapter follows a situated perspective, based on the networks of trust I established in the course of the last ten years in this field, and the personal sharing with some of the key people that contributed to the development of the debate around art and whistleblowing. The concept of Art as Evidence was inspired by an exchange between Academy Award-winning filmmaker and journalist Laura Poitras, artist, academic researcher, and investigative journalist, Jacob Appelbaum, artist and geographer Trevor Paglen, and myself. As described in the following interview with Laura Poitras, in the fall of 2013 she suggested the framework of Art as Evidence for our keynote event at the transmediale festival in Berlin, to describe this common artistic perspective, and a conceptual zone to investigate artistic practices that speak and inform about reality, as well as provoke a reaction about it.4

According to Laura Poitras, connecting art with evidence means to reflect on “the tools and mediums we can use to translate evidence or information beyond

truth-telling: https://aksioma. org/networked. disruption.

5 Bazzichelli, Tatiana, “The Art of Disclosure: Interview with Laura Poitras”, initially published in The Af terglow transmediale magazine, 2, Berlin, (2014): 16-18, and expanded for this anthology. The quote is taken from the actualised version of the interview, following this chapter.

6 See the video documentation of the panel: “SAMIZDATA: Evidence of Conspiracy”,with Jacob Appelbaum, Laura Poitras and Theresa Züger, moderated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, Disruption Network Lab, Kunstquartier Bethanien, Berlin, September 11, 2015, https://www. youtube.com/ watch?v=XyZAYanzMKw, retrieved July 27,2021.

The full sections of the chapter can be downloaded here

simply revealing the facts, [and] how people experience that information differently not just intellectually, but emotionally or conceptually.”5 Following this perspective, art becomes not only a way to translate information, but also an entry point to investigate sensitive issues, and to explore and experience them by sharing them with an audience.

✳

In Laura Poitras’ words: “The work that I’ve been trying to do is to find ways to communicate about what is a really horrible chapter in American history. We can do a reminder that Guantanamo opened in 2002 and there are people there who have never been charged with anything, but where’s the international pressure? […] It isn’t enough to change the reality, but it’s also not enough to say what it means. It’s actually incomprehensible to imagine being in prison and never be charged with anything. I feel like art is a way to express something about the real world. As artists we’re not separate from political realities, we’re responding to them and communicating about them.”6

✳

In this context, the act of leaking and provoking awareness through whistleblowing and truth-telling becomes a central part of the strategy of media criticism, by bringing attention to abuses of governments, institutions, and corporations. The objective is to reflect on interventions that work within the systems under scrutiny, and increase awareness on sensitive subjects by exposing misconduct, misinformation and wrongdoing in the framework of politics and society. This means interlinking the act of disclosing with that of creating art, shifting the debate from the initial intentions of whistleblowers to inform the public, to another level where whistleblowing becomes a source of creative experimentation and social change.

✳

The concept of whistleblowing in this essay is presented as something concrete and accessible to a broader public something that everyone can experience and expand into the framework of artistic and activist interventions. Furthermore, the meaning of “evidence” itself is expressed in different ways, and expanded into a context of imaginary experimentation, which the artistic form allows.

✳

the south caucasus has always been a special place for me. one year after my first visit back in 2016, and right after my graduation from, i took off on a month-long hitchhiking trip all the way from minsk to tbilisi with my ex.

✳

three days on the road, before diving in tbilisi for a few more. then five days in armenia and getting lost in yerevan and its surroundings. back to georgia for just an hour for border-crossing. moving further across azerbaijan to baku with another five days in the city buzz. back again from the caspian to the black sea with a blink-stop on the batumi beaches. going up to svaneti and camping out in the high mountains. finally, a four-day sprint back to minsk. that journey became a leapfrog of places with each stop remaining a distinct island in the archipelago of my memories.

✳

i left belarus in the autumn 2020 for studies in london soon after the mass protests against the rigged elections and the subsequent crackdown - that’s how my emigration began. at one point my passport was

stolen and my residency permit expired. so i found myself back in minsk in february 2022 only to observe the extent to which the situation had changed for the worse. having been thinking of georgia as the next country to stick around in for a while, soon the whole world turned upside down. on february 22, i was in the belarusian part of the chornobyl exclusion zone guiding a bunch of international tourists. the russian military was everywhere but little did i know at that point. on february 24, the full-scale russian invasion of ukraine began. then on march 2, i landed in tbilisi, heavy-hearted, knowing this time there wouldn’t be a return ticket home.

later in may, i had a chance to slow down at the aqtushetii residency right in the heart of the tushetian mountains. for a lowlander like me, it became my first experience of living in the highlands. hiking in the wilderness from one hidden village to the next brought back memories of childhood summers in the belarusian

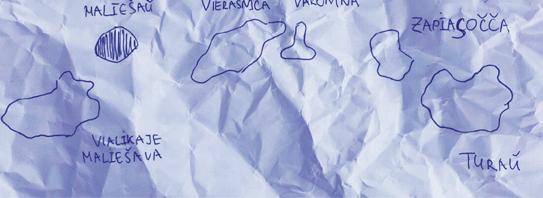

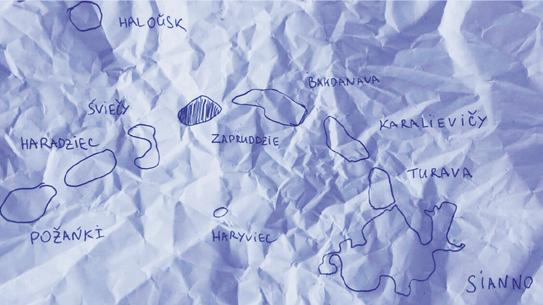

countryside where my parents come from. to cover at first sight close distances between tushetian villages, i had to go deep down to the river valleys and then up to plateaus. proximity was deceptive, which reminded me of how, as a kid, i used to bike through forests and fields from one village to another. back then, in my imagination, those trips felt like journeys between islands across uncharted waters which i later depicted as maps. those memories of childhood places i can no longer visit still sometimes come and go, haunting me in dreams.

ocean of grass washes rocky islets tidal wave erodes fragile coastline dark clouds rise from valleys deep down below ✳

childish maps of the familiar countryside motherland, fatherland and temporary home unreliable narrations being carefully archived ✳

once again native lands turn into atlantis under imperial flood that comes and goes inhabitants flee with promises of a quick comeback ✳

leaving blood from never-healed wounds on sharp rocks

as a result of the residency, the archipelago reemerged as a performance-installation, exploring distance, memory and temporality. recalling childhood memories of family localities, i used local flat stones to represent island chains. starting with the mapping of my mother and father’s countryside, gradually moving from past to present and constantly changing the archipelago, i finalised the performance with the map of the surrounding lands of tusheti representing a temporary home. by covering distances between makeshift islands with jumps, balancing on unreliable rocks and accidentally hurting myself on sharp surfaces, i used my body to construct an ephemeral memoryscape on the edge of wilderness, uprootedness and oblivion.

✳

in september 2023, i repeated the performance at the untitled gallery in tbilisi. this time bricks replaced stones and cities emerged as islands instead of

villages. the visions of the distant past gave way to the routes of my international moves of the last few years. symbolically enough, the performance became one of the last shown in the gallery before the planned demolition. the place that became a temporary haven for me and many other emigrated queer artists can no longer be visited. however, the next archipelago i plan to create will reflect on the history of my queer memoryscape. and no doubt the gallery will be back as one of its islands.

✳

Artistic collectives have long played a significant role in shaping Armenia’s cultural landscape, which has been particularly evident since the late 1980s. This period saw the emergence of influential groups such as the 3rd floor, whose exhibitions and performances challenged Soviet norms and paved the way for conceptual art and socio-political commentary. ✳

During “glasnost” and “perestroika,” the reforms sweeping through the USSR, Armenia’s art scene began to flourish, gaining attention in Yerevan and other major cities. The 3rd floor group, in particular, left an indelible mark on cultural life and art history. Led by artists like Arman Grigoryan and art critic Nazareth Karoyan, the 3rd floor utilized unconventional spaces and provocative interventions to disrupt the status quo. ✳

In 1991, Armenia became an independent republic, and from the mid-90s, contemporary art institutions began to open up, one after another, some of which are still operating. There was great enthusiasm towards the galleries, foundation collections, and everything that was new and promising. The artists, actively participating in the formation of these institutions, continued their independent activities in parallel, forming new collectives and groups. Once the borders opened up, diaspora artists started to engage in the local artistic scene, making friends and establishing institutions. Among the many who began

operating actively in Armenia, it is worth mentioning artists Sonia Balassanian and Charlie Khachadourian, who established an art center and a gallery.

During the mid-1990s, the group known as Act demonstrated a heightened level of social engagement compared to the 3rd floor. They employed an antiestablishment stance, using interventions, demonstrations, and new media to tackle urgent societal concerns. This period coincided with significant societal turmoil in Armenia, stemming from the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse and the resulting blockade with Azerbaijan and Turkey. As demands for social justice intensified, protests erupted throughout Yerevan. In response, the Act group organized an “art demonstration” along the former Lenin Prospect, a major thoroughfare in the city. Artists creatively combined artistic slogans with political messages on demonstration banners, amplifying their collective voice in the public sphere.

The Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art (ACCEA), founded by Sonia Balassanian, an Iranian Armenian artist based in New York, emerged in the late 1990s. Operated by artists themselves, the center provided a vibrant and inclusive space that facilitated cross-disciplinary collaborations. One notable outcome of this environment was the formation of Incest, an all-girl heavy metal punk band in 1998, which remained active until 2004. The center offered them rehearsal space and actively supported their involvement in its activities. Incest distinguished itself through its integration of music and visual art, with two members also being visual artists, resulting in highly artistic and theatrical performances. As a feminist group, their appearance, lyrics, and political attitude challenged patriarchal norms and taboos. Incest garnered support from other artists within the community, who collaborated and amplified

their message through various artistic mediums.

✳

In 2007, the Art Laboratory artists’ team was established, driven by a commitment to address the socio-political climate of the country. Their approach involved utilizing street art, such as graffiti, stencils, and performance, as their primary mode of expression. The group’s focus encompassed key societal issues, including critiques of military service conditions, police brutality, and electoral corruption. However, following a change in power in 2018, their activities underwent a transformation. They shifted their emphasis towards educational programs and seminars dedicated to political art, with a particular emphasis on street art.

✳

Queering Yerevan represents a dynamic collective of artists, cultural critics, activists, and writers who converge to explore new narratives and imagery, using the city itself as both inspiration and experimental ground. Without a fixed membership count, members come and go, contributing to a fluid and transformative entity that engages with themes of sexuality, the queer community, and translation. Founded by queer women, the collective endeavors to unite the queer community through their blog — a platform for critical texts and translations of feminist and queer literature. Lucine Talalyan, one of the founders, and her peers, question the system of art and how artists represent themselves within that system.

✳

Additionally, it’s worth noting the launch of the Artist-run Yerevan Biennale in May 2020. This unique event brought together artists from diverse backgrounds and generations. Born amidst the isolation and despair of the COVID-19 pandemic, and during a time of institutional fragility, the Biennale’s inception underscored the need for artists to reclaim agency and establish autonomous spaces.

✳

The Artist-run Yerevan Biennale poses

thought-provoking questions about the relevance of traditional art distribution methods, such as biennales, in today’s context. It also delves into issues of caretaking and guardianship within the art world raising queries about who truly holds stewardship over art and communal life.

✳ Ultimately, the Biennale aims to exemplify collective thought and resistance against various societal malaises, including individualism, careerism, and privatization. Beyond exhibitions, it facilitates diverse practices,

such as the collective production of a newspaper, highlighting its commitment to fostering artistic dialogue and collaboration. Importantly, the Biennale is organized and executed by artists themselves, emphasizing the importance of artist-driven initiatives in shaping the contemporary art landscape.

Chief Editor

Giorgi Rodionov

untitled tbilisi

Editing Team

Alexandra Goloborodko, Sergej Morozov

Copyright

✳

Proofreader Faye Armit

✳

Designed by holystick

✳

Printed by Xaraxura Press, Tbilisi, Georgia

Unless otherwise stated, all contents are the copyright of the authors and may not republished or reproduced without their permission or that of the original publisher. In the case of republishing the original source must be mentioned.

✳

✳

We would like to thank all the authors, participants, partners and helpers for their contribution to the Pause/Play: Culture under Pressure project and for this publication.

✳

✳

More information at https://cultureunderpressure.art/ ✳ ✳

This publication is produced by Kultuschafft e.V., and untitled tbilisi, with financial support from the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Mediapartner: TAtchers’ Art Management

Contacts:

✳

Web: https://cultureunderpressure.art/

E-mail: cultureunderpressure@gmail.com

Instagram: @culture_under_pressure

Facebook: Pause/Play: Culture under Pressure

The zine encompasses a collection of texts and artistic projects dedicated to the self organized art groups and to the migration of artists and art-initiatives, caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and political repressions in Belarus. The publication explores various strategies for navigating new spaces and engaging with local communities, reflecting on individual experiences. Simultaneously, it addresses the shifting trends of the digital art, activism and the move of artistic practices into digital spaces. ✳

The catalyst for the publication was the project Pause / Play: Сulture under Pressure, which took place online and offline in Tbilisi and Yerevan from 2022 to 2023.

Pause / Play: Сulture under Pressure website

Pause / Play: Сulture under Pressure website