FOSTERING HOPE

ISSUE 15 FALL 2025

DIRECTOR

Tom Greggs

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR

Joshua Mauldin

SENIOR RESEARCH OFFICER

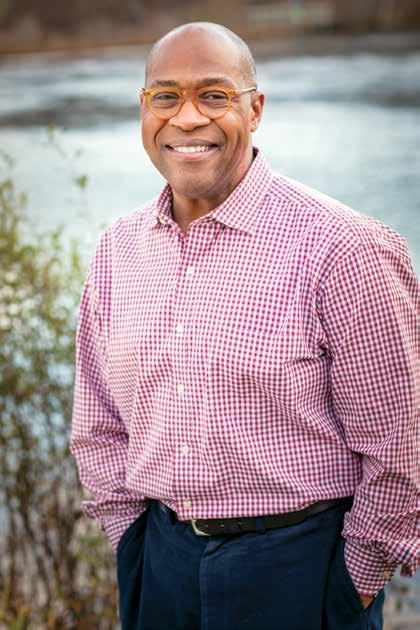

Frederick Simmons

DIRECTOR OF OPERATIONS

Michelle Tan

EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT

Sara Reamy

DIRECTOR OF FACILITES

Robert Jones

SOCIAL IMPACT FELLOW

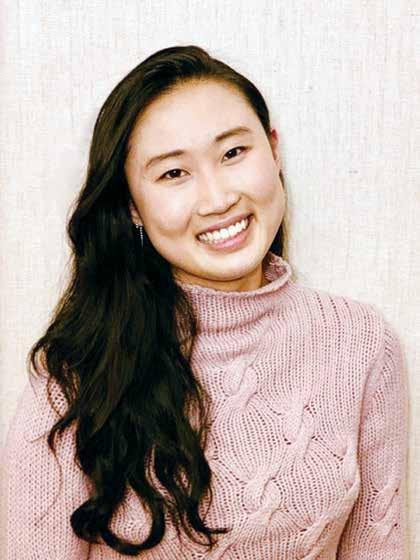

Sarah Joo

DESIGNER

Debra Trisler

CONTRIBUTORS

George Aberdeen

Valerie Cooper

David Ford

Tom Greggs

Eric Gregory

Sarah Joo

Roy Lennox

Joshua Mauldin

Kate Sonderegger

Iain Torrance

Robert Traynham

You’re a valued member of our community.

Please update your contact information to keep in touch.

Scan this QR code to fill out a two-minute form or email us at director@ctinquiry.org

OUR MISSION

BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Roy Lennox, Chair

Gayle Robinson, Vice Chair

Jon Pott, Secretary

Robert Wedeking, Treasurer

George Aberdeen

Fred Anderson

Darrell Armstrong

Bette Jane (B.J.) Booth

Tom Greggs

Robert Gunn

Douglas Leonard

Robert Traynham

Charles Wall

EMERITUS/EMERITA TRUSTEES

Robert Hendrickson

Carter Karins

Jay Vawter

Judy Wornat

Ralph Wyman

CTI undertakes rigorous exploration of all dimensions of faith and reason in the service of God for the benefit of church, culture, and all creation. In our inquiry we are sustained by our belief that the truth is one, and by our hope that our efforts will ignite a theological renaissance.

OUR PROGRAM The Hope for our Theological Future

— FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES —

Roy Lennox

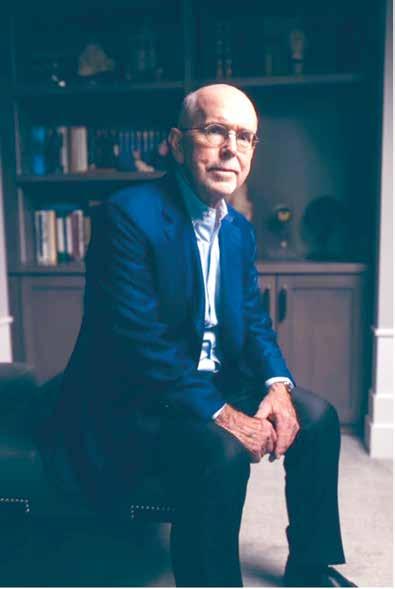

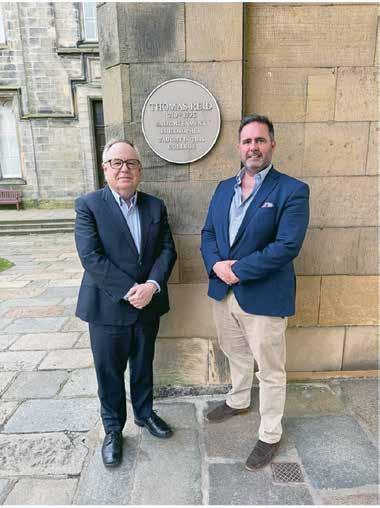

As Chairman of the Board of CTI, it is a great honor to open this issue of Fresh Thinking. In general, this opening page is written by our Director. However, since this marks the first edition of Fresh Thinking under our new Director, Dr. Tom Greggs, I wanted to take this opportunity to welcome him publicly and introduce him to our broader CTI community.

Dr. Greggs comes to us from the University of Aberdeen where he held the Marischal (1616) Chair of Divinity and also served as Head of Divinity. Dr. Greggs has a passion for Theology and its need to speak to the big issues of our world today. We are delighted that he will lead us in advancing our mission set over forty years ago by James McCord. As a distinguished theologian in his own right and a prominent religious leader with an international network, Dr. Greggs is ideally suited to lead what I believe is the world’s leading theological research institute. To find out more about Dr. Greggs, explore our website, where there are details about him as well as interviews with him.

Dr. Greggs has recently secured a $4.5mil grant from the John Templeton Foundation entitled: From Despair to Hope: Inter-Disciplinary Theology in the Service of Building Spiritual Capital. Over the coming three years, this magazine will largely be concerned with exploring these issues in relation to the areas in which our work on turning despair into hope will focus: Artificial Intel-

ligence; Civic Society; Health; Education; and Entrepreneurship.

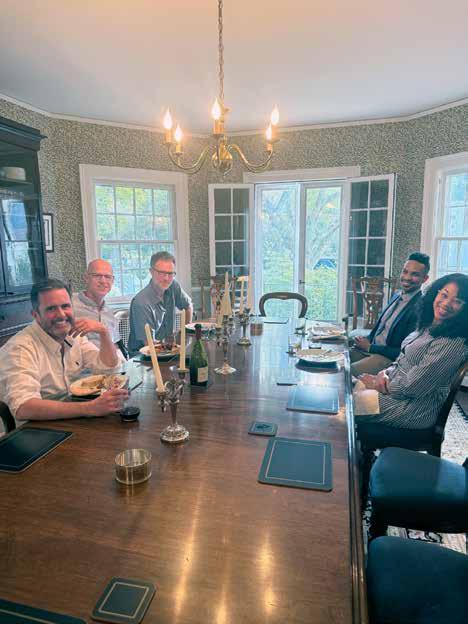

This edition of Fresh Thinking brings together our two themes which we are currently exploring: The Future of Theology (in residence fall 2025); and From Despair to Hope (digitally in fall 2025 and in residence from 2026). This is an exciting moment in CTI’s life. We have a new building, a new director, a new way of doing programming, and a major grant. In this edition, we explore what it might mean for CTI to Hope in Our Theological Future

In the magazine, you will find a series of shorter reflections on “Why Theology Matters” for the church, university, and world from leading thinkers and members of our community—Rev’d Dr. Katherine Sonderegger (Virginia Theological Seminary), Dr. Valerie Cooper (Duke University and current CTI senior fellow), and The Very Rev’d Professor Sir Iain Torrance, KCVO (President Emeritus of Princeton Theological Seminary). We also have a longer article by Dr. Greggs addressing why we might want to place hope in our theological future, as well as an interview with one of our new trustees, Dr. Robert Traynham (President and CEO of The Faith & Politics Institute). A longer interview piece with David Ford (Regius Professor Emeritus of Divinity at the University of Cambridge), placing Dr. Greggs’ tenure in light of his forty year relationship with CTI is also included in our magazine: Dr. Ford

was both the son-in-law of CTI’s first permanent director, Professor Daniel W. Hardy, and the Doktorvater of our new Director, Dr. Greggs; so he brings a unique perspective of the arc of CTI’s life. The location of CTI in Princeton and the place of Theology here is the topic of an article by current senior fellow, Dr. Eric Gregory (Princeton University). Another of our new trustees, The Most Hon. The Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair, closes the volume with his musings on the music of theology. We are sure our Fresh Thinking will provide much stimulation for you.

The fall edition of this magazine also formally records our thanks to those who have donated to CTI in the last year. Without the support of our donors, our programming and work would not be possible, and we are deeply grateful to you. We are seeking to increase our engagement with our friends and supporters in the coming months and years. Please do reach out to us if you wish to continue to support us, to give for the first time, or to give further. We sincerely believe our most exciting and impactful days lie ahead; and only your support can make this happen. Please join me in giving all you can so that we can ensure that the fresh thinking we have at CTI makes Theology matter in university, church, and world.

Dr. Roy Lennox Chair of the Board of Trustees

Why Theology Matters

The Hope for Our Theological Future

SIR IAIN TORRANCE President Emeritus of Princeton Theological Seminary

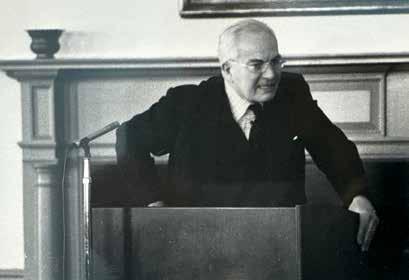

Ishould confess that I have skin in the game. I was president of Princeton Theological Seminary from the middle of 2004 until the very end of 2012 and served as a trustee of CTI. My father, T.F. Torrance, considered James McCord to be his greatest friend and was much involved in forging the vision for CTI and so I knew the Center from its birth.

When I was formally installed as president of the Seminary in March 2005, I tried to address theologically the needs of the time. In 2005, polarizing issues included acceptance of same-sex marriage and rendition (torture). I entitled my address “Beyond solipsism.” On receiving Tom Greggs’ invitation, from curiosity, I re-read my address of 20 years ago. I found I still stand by it. Even more than ever. We live in a deeply polarized space and only theology can supply sufficiently nuanced language to address it constructively. So I am partly reprising my former address for a different audience.

I quoted Stanley Hauerwas, a friend from whom I have learned so much. Hauerwas suggested, “No task is more important than for the Church to take the Bible out of the hands of individual Christians in North America.” He continued, “North American Christians are trained to believe that they are capable of reading the Bible without spiritual and moral transformation. They read the Bible not as Christians, not as a people set apart, but as democratic citizens who think their common sense is sufficient for the understanding of scripture” (my italics). It was Hauerwas’ perception of individualized, idiosyncratic, and possessive reading of the bible which caught my attention. When that is combined with great self-certainty we have most of the ingredients which have produced such divisions in western Christianity.

James Frederick Ferrier (1808-64) was a Scottish metaphysician who invented the word “epistemology.” He is important not least because he under-

mined solipsism (the radical form of Hume and Berkeley’s idealism) by breaking out of mono-lingual “sight language,” first through finding a way in which the eye is located within its own field of vision, and second by making use of another sense, in this case touch. This moves us to what I am interested in: with Ferrier we have the beginning of an analogy for how Christian scriptural reading may be released from its own self-absorption, competitiveness, and finality – the very difficulties cited by Stanley Hauerwas. So what we are looking for are more constructive ways of reading scripture than many of those which are currently offered.

How are we to find a vocabulary so that we may be more observant both of text and of humankind?

As part of a response, let me tell you a rabbinic story, which was given to me by the late Jacob Neusner. It comes from Lamentations Rabbati Petihta 24. The context is a debate about the destruction of the sanctuary. In the course of the debate, Abraham, pleading for his children, said to the Lord: “Lord of the world! How come you have sent my children into exile and handed them over to the nations? And they have killed them with all manner of disgusting forms of death! And you have destroyed the house of the sanctuary, the place on which I offered up my son Isaac as a burnt-offering before you!?” The Lord replied to Abraham, “Your children sinned and violated the whole Torah, transgressing the twenty-two letters that are used to write it,” and the Lord then called in turn upon each of the letters of the alphabet to bring testimony against Israel. Eventually, when they had all given evidence and Israel stood utterly condemned, Rachel sprang to Israel’s defense.

The pericope reads:

“Then Rachel, our mother, leapt to the fray and said to the Holy One, blessed be He, ‘Lord of the world! It is perfectly self-evident to you that your servant, Jacob, loved me with a mighty love, and worked for me for [my] father for seven years, but when those seven years were fulfilled, and the time came for

my wedding to my husband, [my] father planned to substitute my sister for me in the marriage to my husband. Now that matter was very hard for me, for I knew the deceit, and I told my husband and gave him a sign by which he would know the difference between me and my sister, so that my father would not be able to trade me off. But then I regretted it and I bore my passion, and I had mercy for my sister, that she should not be shamed. So in the evening for my husband they substituted my sister for me, and I gave my sister all the signs that I had given to my husband, so that he would think that she was Rachel. And not only so, but I crawled under the bed on which he was lying with my sister, while she remained silent, and I made all the replies so that he would not discern the voice of my sister. I paid my sister only kindness, and I was not jealous of her, and I did not allow her to be shamed, and I am a mere mortal, dust and ashes. I had no envy of my rival, and I did not place her at risk for shame and humiliation. But you are the King, living and enduring and merciful. How come then you are jealous of idolatry, which is nothing, and so have sent my children into exile, allowed them to be killed by the sword, permitted the enemy to do whatever they wanted to them?!’”

T.F. Torrance, Iain’s father and a founder of CTI.

The pericope continues: “Forthwith the mercy of the Holy One, blessed be He, welled up, and he said, ‘For Rachel I am going to bring the Israelites back to their land.’”

We live now in a context in which our tradition, the Christian one, has reached virtual deadlock over a whole series of issues, a zero-sum game in which if there are winners there are losers also. There are certain questions which we seem incapable of resolving so long as those issues are posed legalistically. The Rachel pericope shows the way. Jacob Neusner described it to me as being unique in the canon of formative Judaism. He wrote to me: “I cannot point in Midrash compilations that reached closure prior to this one to a passage of the narrative ambition and power of Samuel bar Nahman’s. We are in a completely different literary situation when we come to so long and so carefully formed a story as this one.”

The Rachel pericope is not definitive in the sense that it has no ambition for finality, but it is observant of human love at such a different level that it succeeded, in literary form, in eclipsing shortsightedness even in the Lord. I think it is that daring. It is the abject failure of our shortsightedness in our sight-language-only reading of sacred text which is my concern.

This is why scriptural reading matters, and why it is so imperative that we are enabled to move beyond the current impasse. And here I want to make some reference to the vision of Peter Ochs.

In his delineation of it, the aim of scriptural reasoning is to reconstitute modern thought as a practice of reflection upon our actions, and thereby to discern in them traces of the divine will. Scriptural Reasoning questions and seeks to interrupt the contemporary process which polarizes on the one hand secular modernism, and on the other anti-modern religious orthodoxy. Peter Ochs maintains that while truth claims are not impossible, they are more indirect than either side of such polarization permits. A sense of the indirectness of truth claims is what I am suggesting. As Peter Ochs puts it, “Truth is recovered in Jesus’ parabolic tradition, or in the Midrashic tradition, but certainly not through rude attempts to reassert a religious axiology by restating varieties of the Ten Commandments or the Sermon on the Mount as propositional creeds.’

Peter Ochs seeks to locate truth, now understood indirectly, with respect to its success or failure in resolving the problem or suffering which gave rise to the inquiry. I stand with Peter in that endeavor and this helps to illustrate why Theology matters.

Why Theology Matters

The River of Fire

KATE SONDEREGGER

Distinguished Professor of Systematic Theology

Virginia Theological Seminary

The great Russian expatriate, Sergei Bulgakov wrote a withering assessment of the debate over the Procession of the Holy Spirit between East and West: “From the point of view of positive dogmatics, this millennium-and-a-half logomachy pertaining to the procession of the Holy Spirit was totally fruitless. Despite immense efforts of thought, the problem of the procession remained in a nebulous dogmatic state, and the efforts of scholastic theology as well as the inquiries of patristics and exegetics produced nothing.…And the problem remains in a hopeless state of ‘suspended animation.’” As if this denunciation of dogmatic controversy from the Council of Florence onward were not enough, Bulgakov exposes the exorbitant cost of fruitless debate: “It is remarkable,” he writes in the 1930’s, “that this Filioque dispute killed all interest in the theology of the Holy Spirit….Each side in this dogmatic dispute attacked and anathematized the other for distorting the most important dogma concerning the Holy Spirit. Over the course of many years, I have sought traces of this influence, and I have attempted to comprehend the life-significance of this divergence and to find out where and in what it is manifested in practice.” Bulgakov concludes this lacerating survey with a word of bitter finality: “I must admit that I have not been able to find this practical life-significance; and more than that, I deny that there is any such significance.” All this from the immensely creative and influential author of The Comforter, a book described by Boris Jakim in rounded tones as “the most comprehensive and profound book about the Holy Spirit ever writ-

ten by a Russian theologian, and perhaps one of the most profound books about the Holy Spirit ever written.”

Although confined to the dogmatic contest over the Procession of the Holy Spirit within the Blessed Trinity, Bulgakov gives voice to a general dis-ease about Christian theology as a whole. Is it in truth a species of logomachy, a war of words, that in the end bears no fruit, and worse, bears no “life-significance?” Although I too have spent my life in theology, and share Mr. Jakim’s unembarrassed admiration for the work of Sergei Bulgakov, I cannot shake the impression that Bulgakov has spoken truthful words about our common discipline, words I must hear. Who has not read, or heard in synod, in lecture hall and in consistory, an exchange over doctrinal matters that in the end appears immensely learned and utterly futile? And much worse, have we not watched in grief, or even stolen pleasure, as lofty theological dispute has in truth divided and destroyed, not edified or healed? I imagine the readers of this essay will easily conjure up sad memories of just this kind. And just so the question, Why Theology Matters?, is hardly an idle one. Jesus Christ is the Way, the Truth, and the Life; our words about Him, the Living Word, must be true —and they must also live. Theology must matter: this is a central preoccupation Bulgakov shared with other European intellectuals in the Inter-War Years. One thinks here of Franz Rosenzweig, of his collaborator in the great work of Bible translation, Martin Buber, of Erich Przywara, of Hannah Arendt and Edith Stein, of Camus and Kafka and Mother Skobtsova, and of Karl Barth. These are philosophical thinkers for whom the intellectual questions of their era—central Europe in the

When we read theology that has crossed the true River of Fire, we recognize it immediately. It is a summons.

midst of collapse—meant life and death. Christian theology should matter in just this way. For in it we properly take up the elemental question of all life—the Krisis, Barth called this—our existence before the One Holy God. There is no “unengaged” theology, for its Subject Matter is the Origin and the Judge of all creation, God the Pantocrator. We may imagine, of course, that Christian theology is merely a discipline, an intellectual method and study program that fits, perhaps uneasily, within the university system of the arts and sciences. Most certainly, theology is demanding! The thought of God requires our highest intellect; indeed it is for this Thought that our minds were created. But this field of study, the scientia Dei, the science of God, cannot avoid the iron testing of its discipline, the encounter with the Living God. In that Fire, all metal is tested. When we read theology that has crossed the true River of Fire, we recognize it immediately. It is a summons. Such theology is written in every Church and tradition; it belongs to no single school or allegiance. It is rigorous, demanding, learned; yes. But it is the intellect at prayer, the whole of a life, born of God and borne by Him. That theology matters; nothing matters more.

Theology Matters is where serious theology meets real-world questions—with scholars like N.T. Wright, Sarah Coakley, and Peter Harrison diving into topics from biblical theology to human flourishing to the rise of secularism. Hosted by CTI, this podcast brings thoughtful, interdisciplinary voices into conversation about why theology still matters today. Be sure to comment and let us know your favorite episode. Please share your favorite episodes across your social media to help spread the conversation.

Why Theology Matters

The Beauty of Theology

GEORGE, THE MOST HON. THE MARQUESS OF ABERDEEN AND TEMAIR

Ilove music. Many different genres and artists but, in recent years, I have been getting increasingly into classical. Perhaps predictably, my favorite composer by far is Mozart. The standard of excellence astounds me. One can listen to the same piece a hundred times and hear something new each time. Some composers are noteworthy due to the technicality of their work. The listener is impressed by how difficult it must be to play. Mozart’s music, although also deeply complex, surpasses that metric because each note is orientated towards the beautiful. We find layer upon layer of music for an audience that is not just listening but feeling and experiencing

what is being played. It would be true to say that each part could be played on its own and sound glorious. For example, listening to his Piano Concerto No.21, it would be easy to assume, in the first two minutes, that the lead is the violin, and it is music that most composers would consider the defining work of their life. But Mozart has a whole new dimension to add. When the piano comes in, it is a completion that comes close to perfection and plays to every dimension of the listener.

Churches will preach sermons the equivalent of a commercialized pop song, while others dazzle with their complexity, to the applause of some academics. Perhaps we have fallen into the trap of giving people what they think they want rather than what they need. Some like pop, others don’t, but Mozart’s music transcends taste. There is something for everyone to enjoy. And, importantly, the music can be played by an orchestra of 100 professionals or simplified for a beginner in their living room.

This is what we need in theology; the radical pursuit of excellence and for every note to be orientated towards the beautiful. It is with that “sheet music” that the evangelical front line is suitably armed. Whether it is famous professional communicators playing the whole concerto, or the amateurs at home picking one line of the score, it speaks to the soul.

In Amadeus, the movie about Mozart’s life, Salieri says of his nemesis, “this was a music I had never heard. Filled with such longing, such unfulfillable longing, it seemed to me I was hearing the voice of God.”

As a Christian, I believe God revealed to us perfect theology in the person of Jesus. No person will ever be entirely correct in their interpretation and analysis. No composer will ever write the perfect piece. However, it is in that pursuit that, like Salieri, we might feel like we are hearing the voice of God.

This is why I am proud to be a part of CTI. The multitude of composers coming through the front door will be led by my dear friend and the Center’s new Director, Professor Tom Greggs, to give the world the beautiful concertos it needs.

Why Theology Matters

A Call to Hope

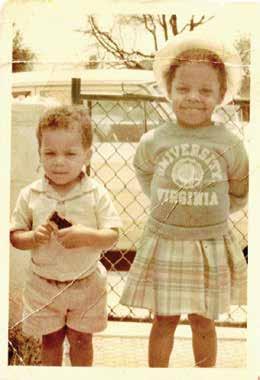

VALERIE C. COOPER CTI Senior Fellow

“May the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, so that you may abound in hope by the power of the Holy Spirit.”

Romans 15:13

When I taught at the University of Virginia, I kept a picture of myself as a little girl of between four and five years old on the bulletin board above my desk. The photo itself had been a mystery when my mother had rediscovered it while downsizing from the big old house where she and my father had raised our family. No one seemed to remember it, but it did seem serendipitous for it to have turned up shortly after I came to work for the University in 2005. In the photo, I am wearing a University of Virginia sweatshirt and standing beside my little brother, Jay, who was about two years old at the time, and clutching a toy car. From the background, I can tell that the photo was taken on the front walkway of my paternal grandmother’s house in Charlottesville, Virginia, the town where my father grew up. My father was surely the photographer.

I don’t remember the sweatshirt or the occasion when the picture was taken, but the photo reminds me of many visits I made to my grandmother’s house when I was little. After puzzling over it a bit, I began to imagine what might have happened in the hours leading up to the snapshot. My family probably had just returned from a shopping trip downtown where my brother had asked for a toy car, but I had, as usual, requested clothing. In all those childhood visits to Charlottesville, though, I don’t remember visiting the campus of the University of Virginia, although my grandmother lived within walking distance of it.

My grandmother, her sisters and her mother had all worked as domestics, taking in laundry for students at UVa in the days when the college was all male. While in high school, my father had worked on “The Corner”—the area across the street from campus where restaurants and stores vied for student dollars—first as a pin setter in a bowling alley with his friend “Stumpy” (whose real name was Clarence), and then as a busboy at a restaurant. Later, I taught at the university that would not have enrolled my father as a student—although he was a very, very good student—because he was black.1 I kept the photo of the little girl wearing the University of Virginia sweatshirt on my UVa office bulletin board to remind myself that my history with the university went back quite a long way.

Had my father remained in Charlottesville in those Jim Crow days when he was growing up there, he might have had a career as a meat slicer or perhaps a waiter. These were the last jobs he held before he graduated from high school and were probably considered good jobs for a black man in those days. Had my father stayed in Charlottesville, high school would have been the end of his edu-

cation: there were no historically black colleges in Charlottesville and at the time, UVa did not admit black men2 anyway. Because my father left Charlottesville after high school, he was able to go to college, to graduate school, and finally, to law school. Had he stayed in Charlottesville, he might have worked in a restaurant that probably wouldn’t have served him as a customer. Because he left Charlottesville, he was able to become a lawyer.

The photo on my bulletin board reminded me of the privilege I enjoyed in teaching at the University of Virginia, even as it called me constantly to remember the past, when the University was not so charitably disposed toward African Americans or women like me.3 At the time that I was photographed wearing a University of Virginia sweatshirt, the University had not yet admitted black women as undergraduates. I taught at a university that, for much of its history, permitted blacks on campus only as enslaved people or as servants, but not as students.4 I lived in Virginia, a state that had shut down some of its public schools rather than integrate them.5 I come from a family that had served the university but had hesitated to take me to campus to visit, for fear that we would not be welcomed there.

And yet, there I was in that photo on my bulletin board, smiling, and wearing a University of Virginia sweatshirt, a symbol of my family’s hope that perhaps someday would be better for all of us than all of the days that had gone before.

I embody all of those complications and contradictions. I embody all of that hope.

In my scholarship, I try to help people understand what such contradictions have meant. In studying and exploring African American Religious History and Black Theology, I work to help others appreciate how religious communities and leaders have grappled with the complications and contradictions produced by systems of racial and gender inequality. Central to this teaching is my understanding of the ways that racial segregation has hurt people like me and families like mine. I help students see the possibilities for tragedy and for transcendence that arise from living in and through

these complications but despite these limitations. Even as I help others see the pain and trouble in our shared history, I believe that I also help them see the hope in my little girl’s smile. Moreover, I continued to live the legacy I inherited as a little girl on my grandmother’s front walk, by teaching, speaking, and writing about what it means to be such a person as I am, while I worked at such a place as the University of Virginia, and for such a time as this.

In The Scandalous Gospel of Jesus, Rev. Peter Gomes writes, “Dietrich Bonhoeffer once warned against cheap grace, and I warn now against cheap hope. Hope is not merely the optimistic view that somehow everything will turn out all right in the end if everyone just does as we do. Hope is the more rugged, the more muscular view that even if things don’t turn out all right and aren’t all right, we endure through and beyond the times that disappoint or threaten to destroy us.”6

What kind of hope buys a little black girl a sweatshirt for a college that hasn’t yet enrolled any black girls? It is a mighty strong hope; it is a hope that endures. It’s a laughing hope; it’s a loving hope. It is the kind of hope that has kept my family going, generation after generation. And although my family may have hoped that someday I might become a student at UVa, I don’t think that anyone dreamed the bigger dream that I’d someday be a professor there. And yet that is exactly what that hope had produced, in me.7

These days, I serve as a senior fellow at the Center of Theological Inquiry (CTI), led by its newly installed director, Dr. Tom Greggs. The Templeton Foundation has given CTI a $4.5 million dollar grant to fund a project on hope entitled “From Despair to Hope: Interdisciplinary Theology in the Service of Building Spiritual Capital.” I look forward to thinking about, writing about, and discussing the sort of durable hope so necessary in difficult times and I invite your support and prayers as we begin this journey!

A Call to Hope ENDNOTES

1 Alice Carlotta Jackson was the first known African American to apply for admission to the University of Virginia. In 1935, she sought entry to a graduate program in French. Although the University was all-male at the undergraduate level, a few women had been admitted to graduate and professional programs. In rejecting her, the Board of Visitors of the University wrote, “The education of white and colored persons in the same schools is contrary to the long established and fixed policy of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Therefore, for this and other good and sufficient reasons not necessary to be herein enumerated, the rector and board of visitors of the University of Virginia direct the dean of the department of graduate studies to refuse respectfully the pending application of a colored student.”

When asked by Jackson to enumerate the “good and sufficient reasons” for her rejection, the University refrained from further comment. Then, the State of Virginia worked quickly to establish a graduate program at a nearby historically black college so that Jackson could enroll there instead. The state legislature passed the Dovell Act in 1936, which provided scholarships for qualified black applicants to attend schools outside of Virginia. “As a result of the Dovell Act, hundreds of African-American students pursued their higher education goals at the Commonwealth’s expense—albeit, outside of their home state.”

Programs like the Dovell scholarships were enacted to ensure that the University of Virginia could remain racially segregated by providing black students with separate-but-equal educational opportunities elsewhere. https://explore.lib. virginia.edu/exhibits/show/uvawomen/ breakingtradition.

2 When, in 1959, William L. Duren, Jr., Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences asked University President Edgar F.

Shannon about admitting African American men, Shannon wrote back, responding, “…[A]t present we are prevented from admitting a negro to the College solely because he is a negro…At present, I feel that I am not empowered to admit a qualified negro applicant without further instruction from the Board.”

Nevertheless, despite the administration’s apparent trepidation, the College of Arts and Sciences did finally admit a black student, Amos Leroy “Roy” Willis, the following year. He graduated with a B.S. in Chemistry and went on to earn an MBA from Harvard University. https://smallnotes.library.virginia. edu/2022/02/25/picketing-and-petitioning-desegregation-at-the-university-of-virginia-and-charlottesville-virginia-in-the-1960s.

3 Women were not granted unrestricted admissions to the undergraduate programs of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia until the 1969-70 school year. These admissions were at least partially in response to legal action against the University’s policy of male-only undergraduate admissions. https://explore.lib.virginia.edu/exhibits/ show/uvawomen/coeducation/ heretostay1.

4 Earlier in its history, the University of Virginia had owned enslaved people corporately—that is, that the University had purchased the enslaved people exclusively for University use. “The infrastructure of the university relied upon the labor of university and faculty slaves. Enslaved persons performed the vast majority of the hard labor and some of the master craftsmanship involved in building the Academical Village [campus]. The university hired most of these enslaved people from their masters, but some bondspeople were actually owned by the institution. The owning and renting of slaves by the university continued

through the Civil War.”

“In January 1819 the university was officially founded; in April, Thomas Jefferson, in his role as a member of the Board of Visitors, made a verbal agreement for the university to purchase a slave from Lewis Lashor for $125.” The University owned enslaved people corporately and from time to time, rented them. Faculty brought enslaved people with them to campus, and some of these were engaged in work for the university as well as for individual students. Although students were prohibited from “keep[ing] a servant, horse or dog” on campus throughout most of the antebellum period, some students still managed to bring enslaved people with them to Charlottesville. Catherine S. Neale, “Enslaved People and the Early Life of the University of Virginia,” Senior Thesis, (The University of Virginia, 2006), 4, 13, 22.

5 Susan Smith-Richardson and Lauren Burke, “The state’s policy of ‘Massive Resistance’ exemplifies the incendiary combination of race and education in the US,” The Guardian, November 27, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/ world/2021/nov/27/integrationpublic-schools-massive-resistancevirginia-1950s.

6 Peter J. Gomes, The Scandalous Gospel of Jesus : What’s So Good About the Good News? (New York: HarperOne, 2007), 23. Gomes was Plummer Professor of Christian Morals at Harvard Divinity School and the Pusey Minister of Harvard University’s Memorial Church. Robert D. McFadden, “Rev. Peter J. Gomes is Dead at 68; A Leading Voice Against Intolerance,” The New York Times, March 1, 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/02/ us/02gomes.html.

7 In 2012, I was the first black woman tenured by the University of Virginia’s Department of Religious Studies.

The Future of Our Thological Past

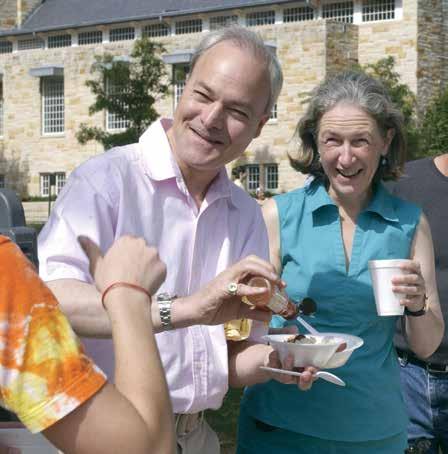

AN INTERVIEW WITH DAVID FORD

Our new Director, Dr. Tom Greggs, has a rather interesting connection to CTI’s past. Dr. Greggs’ PhD supervisor, and great mentor and friend, is Professor David Ford (Regius Professor of Divinity Emeritus at the University of Cambridge). Professor Ford’s closest colleague was CTI’s first ever Director, the late Professor Daniel (Dan) W. Hardy. In fact, the closeness of Professor Ford and Professor Hardy’s relationship surpassed collegiality: Professor Ford is married to Professor Hardy’s daughter, the Rev’d Deborah Ford! After retiring to Cambridge from CTI, Professor Hardy (who died in 2007) was also a friend and mentor to Dr. Greggs during his time in Cambridge—long before any possible connection for him to CTI would have been remotely imagined. In some ways, therefore, and quite rightly, our future is grounded in our theological past.

In this interview, we ask Professor Ford about both Dr. Greggs and Professor Hardy, about CTI’s past and about the hope he has for how Dr. Greggs might bring that past into an even brighter future.

David Ford at CTI in the 1990s

Professor Ford, David, tell us about your relationship to Dan Hardy. We know he was your fatherin-law but he was so much more than that as a colleague and as a theologian.

He was indeed! I first met him when he interviewed me for my first post as a lecturer in theology in the University of Birmingham. I became his main colleague in the areas of modern theological thought and systematic theology, and for years we met together every Thursday, for the whole morning, to talk theology. And, for Dan, theology, as for Aquinas, meant thinking about God above all, and then about everything else in relation to God. He was interested in everything, and I had never met anyone so well-read. He was also an utterly dedicated teacher. I attended his lectures and he attended mine (quite an experience, to give my first lectures with him in the back row!).

The result was an extraordinary, profound apprenticeship to a wise master of both theology and teaching. I could not have had a more inspiring and encouraging beginning to my years as a theological teacher.

What do you see as Dan’s great intellectual insights for the realm of Theology that remain relevant today?

“Intensity” and “extensity” were two of his favorite words, with both of them always related to God. His is not a theology that can be easily summarized. This is partly because of the range of his writings, which embrace historical theology, systematic and constructive theology (especially on God, creation, Jesus Christ, the Holy Spirit, the Church, the future, and the Bible, and on a wide range of thinkers); spirituality (especially on wisdom, worship, the Eucharist, engagement with God, Church, and world together, Christian mission, ethics, and pastoral care); philosophy of science, of rationality, and of language, and philosophers from the seventeenth to the twenty-first centuries; religious education, theological education, university education, and interdisciplinarity; poetry, music, and the visual arts; Anglican polity, the Church of England, and global Anglicanism; ecumenical theology and Receptive Ecumenism; and interreligious engagement. On every one of them he is still worth reading.

But perhaps above all his thought is hard to distil because of its consistent intensity, with repeated fresh improvisations—and he was always rethinking topics. For example, I attended several years of his lectures on both theology and philosophy from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, covering key figures and movements in European and American thought, and I never heard him give the same lecture twice—he had always rethought Luther or Calvin or Kant or Hegel or Kierkegaard or Barth or the Niebuhrs. It was fascinating to hear where he had got to each year. And that range and depth of thinking was matched by a life of practical involvement in the Church, the academy, and wider society.

I think his relevance today is above all as an example and inspiration for us too to stretch our thinking intensively and extensively, and always relate it to God. If you read his major work, God’s Ways with the World: Thinking and Practising Christian Faith (1996), you don’t emerge with neat answers or packages of meaning. Rather you get drawn into deeper engagement with God and the activity of God in the world, by following his creative rethinking of the main sources and topics of Christian life and understanding, while at the same time engaging, critically and constructively, with those aspects of human thought—scientific, historical, cultural, philosophical, religious, and theological—that give much modern life its vitality. He is someone always worth thinking with. He is also relevant for us now in the way he was continually open to developing his thinking in new directions, while always being deeply rooted in mainstream Christian understanding. The great culminating example of this is his role in beginning the practice of Scriptural Reasoning at CTI, and then following it through during his retirement in Cambridge.

What were Dan’s hopes for CTI, and how did that emerge from his commitment to how Theology should be done?

I hope you can see from what I have said how well suited to CTI Dan was. He reveled in the freedom to conceive a whole program of advanced studies in theology, and he threw himself into it. I lost count of the number of versions of his overall vision for the Center that I read and responded to—this iterative, creative, integrative thinking went on all through his years as Director.

His hopes for CTI were extremely ambitious, for nothing less than an intensity and extensity of collegial theological thinking together that would always engage deeply with God, while also being thoroughly involved with a range of other disciplines—and all within a global horizon. CTI was to be profoundly theological in multiple ways: God-involving, world-involving, church-involving, academy-involving, self-involving.

Our Director Emeritus, Dr. Will Storrar, discovered Dan’s institutional reflections, and it profoundly helped him shape the way he thought about CTI. Do you remember from conversations with Dr. Storrar what it was that grasped him from Dan’s thought?

I vividly remember the visit by Will Storrar to Cambridge soon after he became CTI Director. Dan lived next door to my wife Deborah (Dan’s daughter) and me, and I went there to take part in their conversation, followed by an extended lunch in the restaurant of a local hotel. Will had discovered some of the versions of Dan’s vision for CTI and been gripped by them. He had come to talk them through.

It was an extraordinary seminal moment. It was as if the vision that Dan had not had sufficient time to realize (he had only been Director for five years) was being given new life and energy. Will had really entered into it, and the three of us took off in conversation, exploring what the possibilities were. Will also had further conversations with Dan, which Dan told me about. I was moved by the way Dan felt he had been affirmed in his unfinished work at CTI. He was encouraged that all his constructive thinking and imagining had not been for nothing.

As anyone involved with organizations knows, the challenges of succession are among the most difficult, and succession often goes wrong. Here I had the privilege of witnessing succession going right. And I was also privileged to play a small part in Will’s realization of a good deal of Dan’s vision, when I served first as a Trustee of CTI, and later as a member of the Academic Board. I would add something else too. Dan was always practically concerned with the physical and material dimension of CTI—its funding, the buildings, the quality

of administration and the sort of experience staff and scholars had. It has been impressive how Will took up this part of Dan’s legacy too, and I am confident Tom too will attend to this.

In a fascinating way, you stand as a bridge between CTI’s first ever Director and our new Director, Dr. Tom Greggs. You’ve known Dr. Greggs for the best part of 25 years when he was your research student, and you shaped him in terms of his institutional and theological commitments. Tom arrived to study under you from having worked closely with the late Professor John Webster, FBA, and Professor Mark Edwards, FBA, in Oxford, and having been a teacher for a couple of years. What do you remember of Tom from those early days in his theological career?

I remember my first meeting with Tom at my home in Cambridge when he was considering coming to do his doctorate here. I had studied his CV and been impressed by its accumulation of achievements, including the best First Class theology degree Oxford had seen in many years. As we talked, I had the sense that this was not a conversation I wanted to end. And it has in fact continued through a quarter of a century, enriched greatly by our wives, Deborah and Heather, becoming fully part of the friendship. And our children have been part of it too—when Tom tutored one of our daughters for her A-Level examination in Religious Studies, that was the subject in which she got her best result, and she went on to study theology in university.

Tom’s doctoral dissertation involved him reading all Barth’s Church Dogmatics and other works (far in excess of six million words!) and all Origen of Alexandria’s works, together with much secondary literature, and engaging with both the early church and the twentieth century, and a great deal in between. I remember the consistent stream of draft chapter after draft chapter, accompanied by intensive conversations. This culminated in the completion of the work within three years, outstanding examiners’ reports, and publication of the thesis by Oxford University Press. But as if that was not enough, Tom also managed to do undergraduate

teaching (and even continued doing some lecturing for Cambridge after taking his tenure track position elsewhere), to play a full part in local church life (including preaching), and also to have a full social life (including a circle of whiskey connoisseurs). I was especially grateful for him being the organizer of the informal seminar of my graduate students and those of Dan Hardy (in his Cambridge retirement Dan did a good deal of doctoral supervision) which took place in my home, and was also attended by Dan. What conversations!

Tom and Dan used to meet regularly to talk about Theology, church, institutions, and the world. They were very different thinkers in some ways, but in other ways they had profound shared commitments. What resonances do you see between Dan and Tom in terms of their theological work and institutional leadership? Seeing Dan and Tom together I had a sense of déja vu Tom was having something like the experience I had had with Dan in Birmingham. They were indeed different in some ways. I suppose the most obvious way is that Dan was classically Anglican, had a special affinity with Richard Hooker and Samual Taylor Coleridge, was an Anglican priest, and served his church in multiple ways. Tom is classically Protestant, is a Methodist Preacher, is steeped in the magisterial Reformation and in the Wesleys, and has served the Methodist Church in multiple ways. Yet they share immersion in the scriptures, in the early church, in the whole Christian theological tradition since then, and a great deal more. Perhaps most important, the ecclesiology of each is committed within a particular tradition, but also both constructively critical of it and open to what needs to be received from other Christian traditions and also from other religious and secular sources. I think the first volume of Tom’s ecclesiology is the best book on the subject of the church that has been published since Barth, and in it he time and again shows his indebtedness to Dan Hardy. I greatly look forward to the next two volumes Tom has promised (and planned—I have studied the outlines), and I eagerly anticipate seeing how they will be enriched through his Princeton conversations, and his new American and global role.

Daniel W. Hardy in his CTI office

Tom Greggs is classically Protestant, is a Methodist Preacher, is steeped in the magisterial Reformation and in the Wesleys, and has served the Methodist Church in multiple ways.

The positive resonances between their theological works go way beyond their ecclesiologies. I suppose it should be the thing to be said about all Christian theologies, though it is not always so: Dan and Tom are above all united by the depth of their engagement with God, with loving God with all their minds, as well as in other ways. Tom’s mode of writing is different from Dan’s— he can both write in more of a Barthian style than Dan and also more of an informal, attractively popular style. But the substance of both is utterly God-centered, while also being rigorously intelligent.

You ask about their institutional leadership, and here I would see them as both similar and different.

They are completely at one in their commitment to the importance of institutions, and each of them has been both institutionally creative and also a faithful servant of the flourishing of the institutions to which they have been committed.

But Tom already has, I think, something Dan lacked before he became Director of CTI. Dan stayed for twenty-one years in the University of Birmingham but was never head of his department, meaning that his scope for exercising institutional leadership and creativity was limited. Then he went to Durham University, but he was there for only five years, and there too did not have much scope for innovation or long-term leadership. So CTI was the first time he was fully in charge, and then only for five years. Tom, by contrast, has been the main leader of his department in Aberdeen for many years, and has already led it in transformative ways; and he is coming to CTI as Director young enough to achieve something unprecedented.

Tell us what you think of Tom’s time at the University of Aberdeen. Was there anything from that period of time which you think will be important for his time at CTI—both intellectually and institutionally?

In the world of academic theology and religious studies in British universities it is generally recognized that Tom has been one of the most successful institutional

leaders. This was confirmed in the most tangible possible way in the most recent research assessment exercise across all universities when Tom led his department to take the first place among all the departments in theology and religious studies, ahead of Oxford, Cambridge, Durham, and all the rest. It has also been confirmed in other tangible ways, such as his remarkable fundraising ability. Tom knows the crucial importance of having generous benefactors.

Yet both research excellence and fundraising can sometimes be achieved at the cost of other less tangible yet extremely valuable things. In my visits to Aberdeen during Tom’s time there I found many of those other things too. There was above all a quality of collegiality that I have not found in any other university. Tom as head of department was known for his care for the welfare of both staff and students, and for all sorts of community-enhancing initiatives. The culture of conversation and debate was very lively, welcoming, and remarkably free of big egos. And some of the department prayed together with Tom most mornings in the chapel.

I know a good many of his Aberdeen colleagues, and what they all agree on is that Tom has led by example— being an active researcher with world class publications; doing more than his fair share of teaching students, both graduate and undergraduate; searching the world to attract academics to posts in Aberdeen; hosting social events; being available to students; fighting hard for the department within the university; and representing the department across the UK and around the world. Much of this needs to be experienced to be known, but some key elements have had clear confirmation—for example, in the year the department came top in research excellence in the UK it also scored 100% in student satisfaction rating.

For CTI under Tom’s leadership, both the tangibles and intangibles will be important, and I am confident he will deliver them. But there is no way he can deliver them alone. Perhaps the one for which he most needs strong support is in raising funds, the most ob-

jectively tangible thing of all. His gifts and abilities will only achieve their full potential if he has the funding to realize his vision. So my most basic hope for him is that some generous benefactors will support him, liberating him to fulfil the immense potential of CTI as the world’s leading center in advanced theological studies.

What do you think are the pressing needs for Theology today, and how might Tom’s leadership of CTI help contribute to those?

Last month, Baylor University Press asked me to peer review for publication a book by Tom which I think could act as a manifesto for his time in CTI. Its title is Saving Systematic Theology in Church and University: Irreducibility, Experience and Cohesion, and it powerfully advocates for the sort of theology that the church, the academy and the world need today. Theology always needs to learn afresh how to be centered on God and at the same time engage broadly and deeply with both the church and the world. It needs to be able to draw on all relevant disciplines and to testify to truth in the public sphere at a time when there is immense (and very well funded) confusion, distortion, and corruption. Above all, we need to seek, individually and together, the wisdom the church and our world need. And then to live it!

Tom knows all this, and his forthcoming book says it in terms that are acutely relevant to the serious times in which we are living. The same is true of his successful bid for $4.5 million from the John Templeton Foundation for CTI, which comes at exactly the right time to give huge impetus to his vision for CTI. Appropriately, the Templeton project is on the theme of hope. I have read the project prospectus, and see it as well designed in order both to find a wisdom of hope for our times and also orient CTI towards a future in which that wisdom is put to good use.

You have had a long-standing relationship with CTI—from being a fellow in the very early 1990s through Dan Hardy’s years as Director through to being on the Board and working with Dr. Storrar, especially in his early years as Director. Your relationship continues with CTI both personally through your mentorship and friendship with the current Director, but also because you will be part of an

inquiry in January into The Future of Inter-faith Dialogue. In light of this long and ongoing deep connection, what do you think are the principal challenges CTI has for this next phase of its life, but also what are your hopes for CTI?

CTI has, as you say, been very important for me. I am immensely grateful to it, not least for being the place where Scriptural Reasoning began—for me that is the most promising practice in inter-faith engagement at present, and I am delighted that Tom, who is a major contributor to Scriptural Reasoning, is leading next January’s inquiry. I am also delighted that Tom has been a pioneer of the companion practice of Biblical Reasoning, which is seeking to develop a way for Christians who are divided from each other to read the Bible together across our differences. Led by Tom, an Aberdeen University team of Christian academics from a range of different denominations has taken part, together with teams in the universities of Oxford, Durham, and Cambridge, in a project to develop and resource the practice. Can we have a widely accessible, flexible, tested, and teachable practice available to divided Christians who want to read together the one text they share, the Bible? Watch this space!

Overall, I have come to see CTI as uniquely important not only for the future of advanced theological studies, but also for practices such as Scriptural Reasoning and Biblical Reasoning—there really is nothing else quite like it.

So what are my hopes for the future of CTI at this promising juncture in its history?

My four main hopes are for CTI:

• to practice theology in line with what I have described as already being done by Tom, and in line with what Dan Hardy envisioned when he was Director;

• to gather, year after year, wise and gifted theologians to practice and improvise upon that kind of theology together, for the good of the academy, the church, and the world;

• to carry increasing weight in the learning, teaching and practice of theology around the world;

• and for all this to be supported by discerning and generous benefactors.

— THE LONG READ —

Hope for Our Theological Future

TOM GREGGS

To hope is to recognize (usually with lament) the condition in which we find ourselves while at the same time to have expectation and desire for something better ahead of us. This is an age in which we need hope.

At least in the Western World, the new millennium came with such anticipation. The zeitgeist was one of “delirious optimism.”1 The Cold War had ended. Apartheid had ceased. The Internet was in its nascence and offered such possibility. Democracy and capitalism seemed to be the global consensus. Education levels were rising globally. Universities were opening up to people (like me) who could never have anticipated college education just a couple of decades before. Quality of life was on a clear upward trajectory which seemed never ending. Such was the newly perceived global norm that Francis Fukuyama could declare The End of History and the Last Man, transforming political science and historical study in that book. The (perhaps naïve) sense was that the world had arrived at a shared late capitalist, democratic, global reality. Hope abounded.2

But the reality has been otherwise. The new millennium itself has not fulfilled these anticipations. Arguably, the opposite has been true. Indicatively: 9/11 presented the world with a new divisive, global reality; the financial crash of 2008 has led to a decline in living standards from one generation to the next in several advanced economies; the dashed hopes of the Arab Spring across North Africa has seen a changed context in the Muslim world; the Afghan war ended in a return of the Taliban;

the global context presents more of a challenge to advanced western, capitalist democracy than has been the case since the 1930s; the COVID pandemic brought the world to a halt and showed the limits of medical advancements; globalism has given rise to a variety of protectionist nationalisms; global economies have been replaced by Glocal economies; life expectancy has not increased in several major Western countries; South Africa’s hopefulness of a rainbow nation has not been fulfilled; the internet has led to algorithmically controlled life which creates binarized divides; technology is at the point of AI surpassing human intelligence; so-called post-modern paradigms have led to fractures in culture as truth becomes a contested reality, especially around identity; the environmental crisis has captured society with a frightening apocalypticism; the internet has become a means of surveillance rather than the hoped for tool of liberation; the mainstream media has lost the trust of many people in Western Society.

The stark nature of recent changes in society is pronounced and experienced at different levels as well as in different cultural and social settings. Measuring hope or despair is, of course, complex, and measurement of these in populations is a relatively new area of inquiry. But there are multiple indicators which show a lack of hope. On the individual level, there are psychological and even biological markers which might be used to correlate self-reported accounts of hope or well-being.3 Corporately, since the Millenium, there have been measurable increases in despair among particular socio-economic groups in society and among younger people.4 Social scientists have shown that happiness and satisfaction often correlate with hope and are associated with it; but the distinguishing feature of hope is a belief in the capacity to improve one’s situation. This has come by many to be seen as lacking.5 Therefore, on a national or global level, it might be notable that a recent survey by Ipsos of major economies saw that 58% of people thought their country was in decline and 56% considered it broken; only Singapore was an exception. In the USA, only 17% of people did not think their country was in decline. In Great Britain the number of people who believe the country to be in decline has increased from 48% in 2021 to 68% in 2023; this is a huge and rapid transformation. Of course, these measures are not

quite the same as direct measurements of hope and despair, but they are an indicator that people do not believe things are getting better, and at a societal or political level are unable to improve the situation. On an interesting aside, the four most secular countries surveyed (Netherlands, Sweden, Great Britain, France) occupy four of the five top spots in terms of believing their country is in decline.6 This may be connected to the fact that hopelessness expresses itself culturally as well. Ipsos’ survey also shows the lack of hope in the progress of countries is attributed by people across nations to globalism, political culture, rejection of classical political settlements and rejection of expertise. Indeed, according to Google NGRAMS, “despair” features more highly in common parlance in all forms of literature now than at any point from the end of the 19th century.7 The same is true for the term “powerless,” which is remarkable when one considers the limited franchise that existed at the end of the nineteenth century.8

This change and the societal implications associated with it has been captured in several academic discourses, perhaps most notably in the work associated with the Center of Theological Inquiry by Nobel Laureate in Economics, Angus Deaton, and Anne Case. As social scientists, they consider deaths which result from drugs, alcohol, and suicide.9 Their book Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism offers detailed empirical examination of this. They show that, for example, among white non-Hispanics in the USA, mortality rates among those aged 45-54 decreased from the year 1900 to the year 2000 from c.1,350 to c.390 per 100,000 of the population.10 However, and surprisingly, since the new millennium, mortality rates in this category have increased. Indeed, deaths from the side-effects of alcohol or drugs or from suicide among the white non-Hispanic US population aged 45-54 rose from 31 per 100,000 in 1990 to 92 per 100,000 in 2017—an almost three-fold increase in only around a quarter of a century.11

What Deaton and Case show through detailed empirical evidence is that the cause which lies behind these ostensible causes is what they refer to as despair. They trace the locus of this to the impossibility of advancement in

economic terms. But their focus is on the effect of this reality. Here, the reason for citing racial identity becomes evident. While African Americans are likely to be poorer, they are less likely to die the kinds of deaths listed above. Indeed, a steady decrease in these deaths took place from 1990 to 2015 among African Americans.12 What might mark this difference? Case and Deaton point to the positivity of people in terms of whether their life is going well and will continue to improve. After centuries of slavery and then legalized racism and racial segregation, African Americans had become more positive and hopeful with a c.4% increase in this aspect of the General Social Survey between 1970 and 2020, moving in a sustained and constant direction.13 Building on the work of Case and Deaton, Carol Graham notes:

By several measures, the United States is experiencing a full-blown crisis of despair. Suicides, fatal drug overdoses, and deaths related to alcohol use are at unprecedented levels. For example, overdoses alone caused nearly 107,000 deaths in 2021, up from 52,400 in 2015. And, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, surveys of high school students across the United States indicate that the rate of mental health problems in adolescents, especially young women, has consistently risen since the surveys began in 2011, a pattern exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, three in five teenage girls reported feeling persistent sadness, and one in three said they had contemplated suicide. And the malaise extends more broadly. When asked in a recent Gallup poll whether they were satisfied with the way things were going in the United States, only 19% of Americans said that they were. This percentage starkly contrasts with the high of 65% in 1986.14

Of course, satisfaction or happiness are not the same as hope, but they correlate with it. If satisfaction is the present condition in which we live, hope is the condition within the present in which we articulate our capacity to improve the level of satisfaction with which we live. In popular culture and writing, there has been a tsunami of literature attempting to diagnose the problem, usually siding with one side or other of the “culture

wars”. But despite the flood of materials on these issues in other academic and popular discourses, the situation is getting no better—dramatically worse, indeed, if the Ipsos figures for Great Britain (above) are anything to go by. This deluge of diagnosis and description is not hitting the mark: the need for some kind of meaning-making intervention is key.

Hope in Theology?

Where might we to begin to identify the reasons for this failure of alternative discourses to get to the root of the problems of the multiple forms, causes and locations of hope and despair? Those of us who are theologians, we must surely wish to argue that, without at least attending to the theological and spiritual dimensions of these issues, the chance to re-establish hope is always destined to some degree of failure. It is interesting to note, in these discussions, that what has not been sufficiently captured has been that all the while hope declined, so too did religious adherence in the West, especially in relation to the mainline Christian denominations. “Nones” are now the biggest category of people in the US while Western Europe is more secular still. In other words, the deficit in hope that social scientists are recording has coincided with rapid global secularization at least in the West.15 This is certainly true in the USA where deaths of despair have rapidly increased in recent decades. While secularization has already progressed for at least three quarters of a century in Western Europe and much of the Anglophone world, religious decline in the USA has only recently caught up: church or synagogue membership has fallen from 70% (a rate at which had held steady since the 1980s) in 1999 to only 45% in 2023. Furthermore, psychologists have found that dispositional optimism—which is at least prima facie related to hope—is correlated with religiosity.16 Relatedly, in his follow-up to Cultural Pessimism, Oliver Bennett examined “cultures of optimism,”17 identifying religion as an important institution in the building and sustaining of hope. While causal relationships cannot be evidenced, it is at least plausible that religion is a source of hope, and that its decline concomitantly removes that source of hope from many.

So, we might wish to say that if we are to re-gain hope in a world of despair, the need for religious engagement

with these matters is important—imperative even. For those of us with faith, this point might seem obvious. However, in a society which is more educated than ever before, some cheap optimism offered through an escapist focus on another world is far from satisfactory and will never capture and transform the imaginations of a culture of despair. Hope is not mindless, Ostrich-like head burying in the world while imagining another reality either in this world or in a dimension beyond it after death. Hope involves recognizing and acknowledging the circumstances in which we currently find ourselves and, in that, understanding and lamenting the fact we are not where we could be as individuals, societies, cultures and the world. Hope is, in one sense, born of realism and dis-satisfaction combined with a sense that we have not arrived, nor perhaps will we ever fully arrive. This sense of non-arrival is important: hope transcends and is something more than the assertion of one or another current worldview. It longs for and cries for something more. Theologically, we might say that hope as a category realizes the Kingdom of God might just be at hand, close enough that it is at our fingertips; but hope simultaneously acknowledges that that Kingdom will always avoid our grasp and hold. And, as such, simply repeating the same tired mantras of thought will not work. There needs to be a genuine sense of the situation in which we find ourselves and a meaningful vision for where the world is and might be able to go to fulfil its best potential and flourish. While the same themes and issues we as humans have needed since we first came into being will inevitably offer a cantus firmus, we will need to play new melodies on these and improvise on those melodies in each context.

It is this living understanding of the thought related to faith which the best of Theology can offer. My own teacher at Oxford and later my colleague at Aberdeen, John Webster, FBA, described the most illuminating Theology as involving three things:

(1) conceptual ingenuity, resourcefulness, and suppleness, which enable a projection of Christian claims suitable to draw attention to their richness and complexity; (2) conceptual transparency, which enables a more penetrating understanding of primary modes of Christian articulation of the

gospel; and (3) broad knowledge and sensitive and creative deployment of concepts inherited from the Christian theological tradition.18

And, of course, there may be parallels in Jewish Philosophy or Islamic Law. The need for “ingenuity,” for “subtleness” and for “attention to … complexity” is of vital importance to our current contexts of despair. One cause of our hopelessness, indeed, might well be that whatever side of our binarized cultural divisions we might find ourselves on, we face the realization of the worldview we hold not being fulfilled. Instead, our own binarized worldview is greeted by an equally fiercely held one on the opposing side, and the confrontation between the two leads to a mode of entrenched warfare that moves little with small victories for one side or the other all the while the opposition attempts to outflank our sides. Winning hearts and minds, improving our disagreement, enabling iron to sharpen iron is hard in such a mode of war. And while battles may be won or lost, the total victory in the “war” never seems to be possible. This situation demands fresh and insightful thinking which is culturally and intellectually engaged, speaking to our complex contexts and issues. This is no different with regard to our theological thinking. Indeed, Theology might offer something of very particular importance here. Theology reminds us that hope is not a category which involves realization of the concrete form of our present presuppositions. The transformatory work of God in creation is always on the way to its completion, beyond our imaginings and cannot be confused with any one worldview or another. We might say, indeed, that in our social, cultural, and political divides what we have done is replace hope for a better world with the certainty that whichever version of the current world we assent to is the perfect realization in the here and now of God’s purposes: we confuse liberalism or conservativism all too often with the Kingdom of God rather than understanding them both to be provisional understandings we have in which we are to hope for a better tomorrow. As such it is all too easy to despair that others are not subjugated to our kingdom in which our ideology takes the place of God’s complex ways with the world. This identification of the confusion of any political or ecclesial settlement with God’s redemption is an easy win for Theology in the current world—though all too often Theology itself becomes a thermometer reflect-

ing those issues rather than a thermostat setting them. But there is a rigor involved in Theology which is powerfully appropriate for articulating the rationality of faith in and to an age of despair which is also one of increased advanced learning. In society at large, the percentage of adults in the US between the ages of 25 to 64 with college degrees, certificates, or industry-recognized certifications has increased from 38.1% in 2009 to 54.3% in 2021. Theology is crucial in society if faith is to speak in this context. Indeed, the place of Theology within the academy is deeply related to that need. Theology involves the scientific (wissenschaftlich in German) study of God, God’s ways with the world, and all things in relation to God. Theology is the attempt at the intellectual understanding which follows from faith. In this way, Theology is subject to the same kinds of intellectual and academic rigour as any other academic discipline, even as it maintains its basis as thinking from faith. The father of Theology in the modern university, Friedrich Schleiermacher, argued that if Theology were to exist in the university, it must engage in the work of the university to teach people to

regard everything from the point of view of Wissenschaft [science or reason], to see everything particular not for itself but in its nearest scientific relations and insert it into a wide common frame, in steady relation to the unity and totality of knowledge, so that they may learn in all thinking to become conscious of the basic laws of Wissenschaft. 19

Schleiermacher asserted a “covenant” which seeks to maintain both the freedom of scientific critical method and to do so within a context in which faith has its place as well.20 This may seem a strange relationship, but of course all subject areas have their belief systems and metaphysics. In this sense, the place of Theology in the academic community has always been one which has had two horizons: the pure science and inquiry of the university and the living and thinking community of faith which considers its origins and ends to be God. Theology is, we might say, a subject which examines all of reality from the perspective of faith in God—asking everything from whether God exists to what we might learn from ancient wisdom to what belief in God might

mean for the world in the questions we currently face. But is Theology as it is currently exercised equipped to continue to do this work so desperately needed in order to shift an age of despair into an age of hope? The problem is, after all, that we no longer live in a society where the givenness of Theology in a university can be taken for granted. If the subject of Theology is rational reflection on the Christian faith, as soon as that faith is seen as irrational, unscientific, or irrelevant, then its place in an academic context is deeply contested. As secularization has happened and the traditional institutions of faith have declined in their number, status, power, and influence (in complex ways), so too has the overt sense of the place of Theology as a meaningful intellectual enterprise. There are many who would ask: What have the pulpit in the church and the lectern in the lecture theatre have to do with each other? What place does faith have in the corridors of advanced critical learning? Fewer vocations in a more secular society have made even the utilitarian case for retaining Theology in the university ever more difficult to justify and this has been compounded by the establishment of specialist seminaries, entirely divorced from university or research settings, which provide ministers with training aside from the critical cut and thrust of academic departments. Separation of church and state might well have originally meant a minimal secular settlement in which confessional identity could not be required in secular contexts. But that did not demand a complete disassociation of Theology from the powerhouses of learning, as the continued existence of Divinity Schools and Seminaries in the most prestigious university towns indicate. Nevertheless, it is increasingly the case that that minimal settlement is being replaced by a maximal one where secular society is imagined as the telos and endpoint of history. In such a situation, a metaphysically naturalistic or even atheistic starting point is presumed in university learning, seeking a modernist neutrality which suggests that matters of belief are shackles to be broken and have no place in prejudicing not only the thoughts of academics but also the hallowed environs of the university. Such an understanding of Theology as a basis of its exclusion from

universities is, of course, deeply arbitrary and does not reflect the norms required of other disciplines. Can we ever really imagine a situation in which those who teach History or Economics or Politics are not formed and shaped by historiography, belief in economic theory, or commitment to given political perspectives respectively? We would never challenge these beliefs as a (to quote Kant) “self-incurred tutelage” from which we need to be freed. Let alone could we think of the most famous intellectual of the twentieth century, Albert Einstein (who lived around the corner from CTI) without recalling his statements about inspiration, intuition and even miracles in relation to scientific inquiry! Stanley Hauerwas puts it starkly:

If, for example, most academics think there is no problem for departments of economics and schools of business to presume the normative status of the capitalist order, that is, capitalism can be advocated between consenting adults, why is there such a problem with theology?21

However, an imagined horizon of secularization has meant that even when Theology has been able to continue in university settings (as in Europe), all too often Theology departments have in effect become religious studies departments. The content of faith and speech about faith is studied as an object apart from the living community of those who profess faith. It is this which leads so often to the imagination of many people of faith that Theology is seen by members of the church as “a cold, rationalistic, arid discipline that denudes theory of praxis, Christianity of vitality, and worship of the very heart that yearns for God and salvation.”22 Theology becomes a meaningless discussion of unknowable realities (the number of angels on a pinhead) or a practice of museum like study of the past instincts of human beings in relation to that which we (in the university) now perceive to be irrational and unevolved spirituality. Theology becomes something which is observed rather than a living discourse which is participated in as if religious people could all be essentialized, all