FROM THE CURATORS

Carole Caroompas forged a fiercely intelligent visual language that wove together history, feminism, and the politics of representation. Her works are not only visually commanding but also conceptually dense narratives within narratives that resist definitive interpretation. Although I never had the privilege of meeting Carole personally, I feel fortunate to have come to know her work and legacy through the scholarship, insight, and generosity of my colleagues.

It has been both a privilege and an honor to work alongside essayist and independent curator Elise Neal and my CSUF colleague, Mary Anna Pomonis, Associate Professor of Art Education / Coordinator of Graduate Studies in Art. Their deep knowledge of Carole, both as an artist and as a force within her community, has allowed me to see her practice with a clarity and intimacy I could not have otherwise attained. Elise’s extended insights into each work, paired with Mary Anna’s reflections on Carole’s enduring intellectual and pedagogical presence, have illuminated not only the larger cultural and political currents that shaped Carole’s era, but also the ways her practice continues to resonate so urgently today.

With their scholarship as a foundation, I was able to focus on the exhibition’s design and didactic framework, collaborating closely with my gallery staff and students to shape a physical presentation that could honor the complexity of Carole’s vision. The process reinforced the pedagogical mission of our galleries while emphasizing the lasting impact of her work on both scholarly and public audiences.

This project was made possible through the extraordinary support of colleagues and partners who share in the commitment to sustaining Carole’s legacy. I am deeply grateful to Cliff Benjamin, whose gift of Carole’s works to the CSU Fullerton permanent collection ensures that her legacy endures at her alma mater. I extend thanks to Maria Mathioudakis and the team at the Getty Research Institute (GRI), whose generosity in granting access to the Carole Caroompas Papers was indispensable to our research, and to former GRI curator Pietro Rigolo, whose vision secured the importance of Carole’s documents within the GRI’s holdings. I am also indebted to my CSU colleagues, Holly Jerger and Erika Ostrander at the art galleries at CSU Northridge for their collaboration and the loan of materials that have enriched this exhibition. Special recognition is also due to Douglas McGowan of Yoga Records, whose support and commitment to preserving Carole’s legacy through sound and archival practice added an important dimension to this project.

Through this collective effort and with the wisdom of Elise and Mary Anna, I have been given the gift of proximity to Carole’s spirit and a chance to engage deeply with the richness of her vision. This exhibition is both a tribute to her influence and a testament to the community of colleagues, scholars, and supporters who continue to ensure that her work remains vital and resonant.

Jennifer Frias, Director/Curator, COTA Galleries, CSUF

I had the distinct privilege of being around Carole the last twenty-five years of her life. Fresh out of graduate school, I was given a phone number on a piece of paper by one of my advisors from Washington University in St. Louis, Michael Byron. When I called Carole to meet, I was immediately struck by her presence as a fiercely intelligent Greek woman. I had never met another working female Greek artist. Carole and I clicked right away. We shared similar backgrounds and strong bonds with our fathers, yet both of us often felt out of place in our families, as women whose independence and personality traits stretched beyond what was considered acceptable in Greek culture. At different times, we wore our hair short or let it grow unruly, spoke a little too loudly, and always had more to say than was expected. We shared taste in music and art, both drawn to the work of Los Angeles–based artist Karen Carson as well as bands like The Cramps, Lucinda Williams, and X

Over the years, Carole and I spent countless hours talking on the phone during studio time, driving to music and art events, and supporting each other as chosen family when times were tough. I was her emergency contact, and she became a second mother to my daughter. For the last 23 years of her life, our conversations ranged from the significance of making art to the joys of swimming laps and reading books. She introduced me to Orhan Pamuk; I introduced her to Rapsody.

Carole had a unique and singular passion for her imagination, spending her time alone with her cats, reading, painting, and listening to music. She valued solitude above all else. When not alone, she was teaching at Otis College of Art and Design, where she spent more than 30 years on faculty. She loved her students and peers and often told me that art was her husband, lover, and family all in one.

Carole was, by design, deeply self-involved, making a conscious choice never to center her life on anyone but herself. I admired the ferocity of her vision and strove to keep up with her as best I could. Writing this catalog with Elise Neal has been one of the most devotional projects I have ever undertaken. Together, we explored her imagination, with Elise bringing her own perspective from growing up around Carole’s studio.

After Carole’s passing, Cal State Fullerton sponsored an independent study student, Kimberly “Kimby” Ruiz, to help me prepare her studio notes for archiving. Kimby and I scanned notebooks and organized boxes of studio ephemera, which were ultimately placed in the Getty Archives. This labor of love has been a testament to our devotion to a dear friend and fiercely independent artistic guide.

In many ways, the title of this exhibition reflects the nature of my relationship with Carole, a profound and serendipitous union of chance and connection. I am grateful to Gallery Director Jennifer Frias for the opportunity to contribute to this project, which underscores the significance of Carole’s legacy as one of the leading women artists of Southern California at the turn of the century. Collaborating with undergraduate painter Elise Neal, an artist whose own practice has been shaped by Carole’s influence, has further emphasized the generational resonance and enduring relevance of her work.

As an Associate Professor and Area Coordinator for Teaching (Art Education) and Graduate Program Advisor, I strongly believe in the power of connection and collaboration. This show embodies both Carole Caroompas’ creative genius and her passion for mentorship.

Mary Anna Pomonis, Associate Professor of Art Education/Coordinator of Graduate Studies in Art, CSUF

Carole was the nicest mean girl I’ve ever had the pleasure of knowing. Tough to the core, she walked with the stomp of a commanding general; control was always hers, whether in a room or in conversation. With massive tribal tattoos and bold eyeliner, she was a force to be reckoned with. Yet beneath her armor and war paint, she could also be unexpectedly nurturing.

Her studio was a sacred space. Each tabletop served as an altar to some part of herself, every shelf an archive of movement and funhouse ephemera. The room carried a perfectly organized chaos; smoke-tinged but meticulously arranged. Every corner bore her touch, and the abundance of objects and imagery in her life echoed the dense, layered quality of her work.

This sense of order within chaos shaped my understanding of her narrative artworks, assembled environments composed of film stills. The images layered in her paintings, like the objects in her studio, are curated, and in many ways, she lived inside her paintings as much as she lived in her space. I envy her ability to immerse herself so completely in her own thoughts. Her meditative commitment to reading, writing, and thinking, both critically and imaginatively, is what made her such an extraordinary painter. To truly engage with her work, the viewer must be willing to sift through each individual reference to decode a complex cipher.

Music was equally central to her practice and her psyche. Her vast CD collection spanned genres and decades, its influence surfacing in her paintings through dedications and cameos of figures like Henry Rollins and the riot grrrls. Near the end of her life, she returned often to Marvin Gaye. She would close her eyes, pluck a necklace or keychain from a pile of thrift-store junk, and sway in front of the speakers. In those moments, she was calm.

Her artistic process was just as intense as her listening. She worked like a one-woman assembly line, ritualistic and precise. This streamlined approach gave her confidence and efficiency in the studio.

She also adored her Russian Blue cats, Blue and Iggy, who remained with her until the end. Arthritic, curmudgeonly, and endlessly devoted, they brought out a maternal instinct in her that few ever witnessed.

Her eyes remain vivid in my memory, along with her stance: one hand raised, arms crossed, her gaze a pointed mix of judgment and somehow tenderness.

Elise Neal, Artist, Independent Curator

A Closer Look at Carole Caroompas’ Works from CSUF COTA

Galleries Permanent Collection

By Elise Neal and Mary Anna Pomonis

The Tuning

1987–1988

Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 84 inches

CSUF Department of Visual Arts Permanent Collection, Gift of Cliff Benjamin

[Accession No: 2023.000608]

The Tuning brings together a series of visual fragments that address themes of work, communication, intimacy, and cultural symbolism. The title suggests an act of adjustment, to achieve balance or alignment. Throughout the composition, Caroompas examines how individuals attempt to “tune in” to one another and the barriers that can prevent genuine connection.

The left side of the canvas shows uniformed workers pulling and shaping candy canes along a production line. This image invites reflection on routine, effort, and mechanical production. Here, the production line flows toward an image of a couple sharing a cigarette holder designed for two people. While the gesture may suggest closeness, its awkwardness implies a staged performance of unity rather than an authentic exchange. In the upper right, two women are pictured on a roller coaster, their screaming laughs placing them firmly within the world of entertainment. This amusement park imagery connects to other circus and carnival scenes in the painting, including a trapeze artist, a cup juggler, and the foot of an elephant. Throughout the composition, roller coaster supports, trapeze ropes, and tall poles, telephone and telegraph wires create vertical and long lines. The repetition of lines unite the separate vignettes while also linking them to the painting’s focus on communication.

At the center of the work, Caroompas places sculptures of the Hindu deities Kamadeva and Rati. Together, they perhaps symbolize union and harmony. By including these figures alongside scenes of staged romance, labor, and broken communication, she raises the question of whether such an idealized partnership can exist within the constraints of everyday life, or if the concept is a mythology

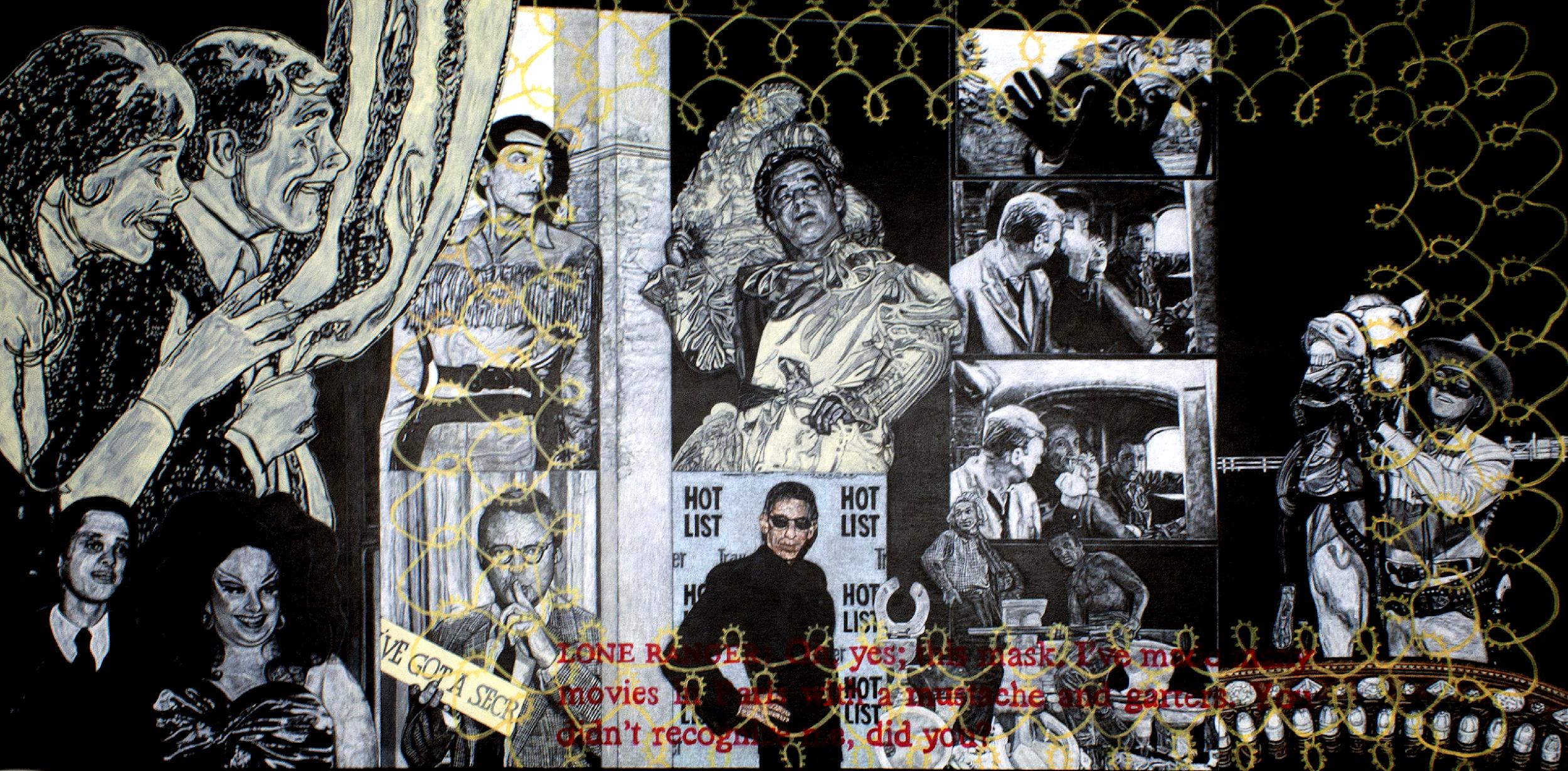

Lenny Bruce and the Masked Man 1993

Acrylic and collage on canvas, 36 x 72 inches

CSUF Department of Visual Arts Permanent Collection, Gift of Cliff Benjamin [Accession No: 2023.000611]

Lenny Bruce and the Masked Man is a visual map of American media history, dense with symbolic logic and cultural critique. Each layer operates like a subconscious dream tableau, in which pop culture, repression, and resistance collide. Perhaps inspired by an animation of one of Bruce’s stand-up routines, Thank You Masked Man from 1971, directed by Jeff Hale, which skewers the Lone Ranger and questions his motives and relationship with both his audience and his sidekick. The routine is a commentary on the nature of masculine identity to both perform for a heterosexual audience, while repressing the obvious queer themes implied in the close male intimacies depicted on television.

Caroompas often sourced her imagery from late-night TV reruns, those after-hours time slots where cultural detritus replays on a loop. In Lenny Bruce and the Masked Man, this becomes a foundational logic. The aesthetic of black-and-white film stills evokes the rigidity of a binary worldview: male/female, hero/villain, white/Black. But the layering destabilizes this tidy order. Her collage practice collapses space and time, warping the original hierarchies of Hollywood storytelling into something more unruly, ambiguous, and real.

Threaded across the surface is a pattern of yellow barbed wire, part frame, part cage. It evokes the invisible constraints around us: the unwritten rules that limit how we perform identity. What parts of ourselves are allowed to be seen? What remains hidden behind the curtain?

One of the key tensions in this painting lies in its exposure of cultural “masks.” A quote in red text, drawn from a Lenny Bruce monologue, reads: “Lone Ranger: Oh, yes; this mask. I’ve made many movies in Paris with a mustache and garters. You didn’t recognize me, did you?” The line humorously skewers the rigid roles assigned to men in American culture. The artist invites us to ask: what if the masked vigilante isn’t a symbol of justice, but of repressed queerness?

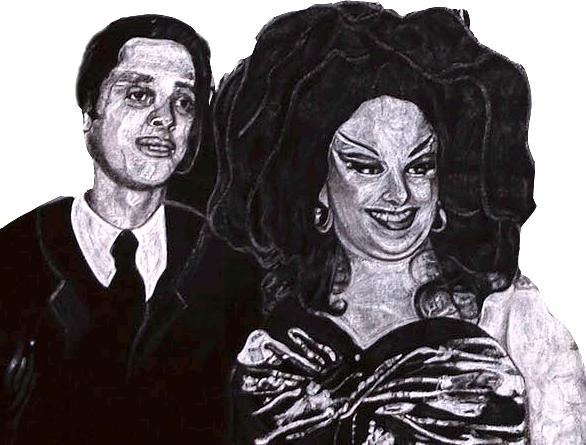

Throughout the painting, we see familiar characters recontextualized: Divine, the drag icon discovered by the filmmaker John Waters, appears alongside Zorro, Audrey Hepburn, Cary Grant, and Richard Belzer. Their juxtapositions provoke questions about performance, gender, spectacle, and power. Is Divine’s hyperfemininity any more exaggerated than the costume mask and fringe of a cowboy actor? Caroompas makes no clear distinction between drag and Hollywood; both are performative, costumed, and coded.

The inclusion of Tonto, the “sidekick” of the Lone Ranger, adds another layer. He’s an Indigenous figure reduced to a supporting role in a white fantasy of frontier justice. How can a Ranger be “lone” when he’s always accompanied? The title itself begins to unravel. Elsewhere, Caroompas references Charade (1963), a film full of misdirection and gender play. In the stills, Cary Grant shifts identities while Audrey Hepburn plays dumb to gain information, both embodying personas they don’t fully own. The film, like the painting, is a game of who’s hiding behind which mask.

Finally, Caroompas references her guilty late-night television habits through the inclusion of pop TV star Richard Belzer, the only figure rendered in full color. Belzer, best known for his role as Detective Munch on Law & Order: SVU, first appeared in the part in 1993, the same year this piece was created, a show Carole compulsively watched. Belzer’s noir cool evokes Lenny Bruce, with his dark glasses and insouciant pose; the masculine Belzer amps in the pose with an air of ambiguity. Under the dark shades, he becomes a caricature of cool, like everyone else in this theatrical display of misfits, miscasts, and media ghosts.

Lenny Bruce and the Masked Man is packed with contradictions, humorous, tragic, sexual, angry, and analytical. Through it, Caroompas pulls back the curtain on the performances we mistake for truth, revealing the mechanisms of cultural mythmaking and the traps that come with them.

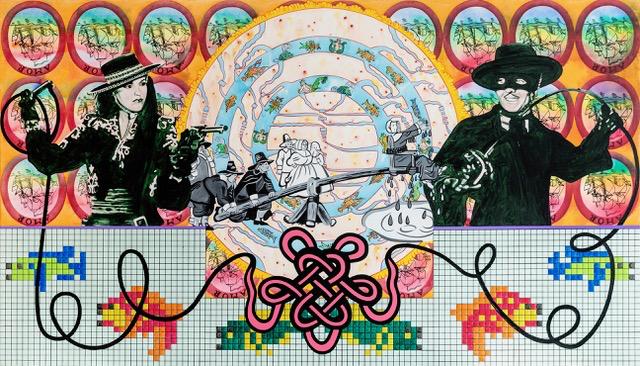

Hester and Zorro – In Quest of A New World: The Little Brook That Carries Woes

Acrylic, ink, oil on canvas, 48 x 84 inches

CSUF Department of Visual Arts Permanent Collection, Gift of Cliff Benjamin [Accession No: 2023.000612]

In this work, Caroompas explores the subject of female sexual empowerment and moral transgression through complex historical, cinematic, and literary references. In this series Caroompas combines the storyline of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s, The Scarlet Letter, and the masked avenger character from the Zorro movies. On the left stands Barabara, the heroinee, in, Zorro’s Black Whip: a 1940s character played by Linda Stirling. In the film, Stirling’s whip-wielding vigilante was a heroine empowered and active in a genre that rarely granted women such agency. Caroompas transforms this figure into Hester Prynne, an outcast single mother evoking themes of female shame, social punishment, and sexual independence. The painting’s title explicitly references Hawthorne’s symbolic “little brook,” which in the novel represents Hester’s daughter Pearl and the boundary Hester struggles to cross: a border between public shame and personal redemption.

Zorro himself appears on the right, smiling slyly under his trademark black mask. The Spanish word “zorro” literally means “fox” but also connotes cunning, even womanizing. In this iteration, Zorro is entangled in Hester’s whip; his sword bends under her power. Is his sword bent in submission, or is it posed ready to strike? Their weapons meet in the center of the composition, intertwined in a Celtic Knot. Traditionally, a symbol of continuity and unity, here it becomes almost bodily, and suggestive of inescapable entanglement. The knot’s endless loops present a Gordian knot–like form, intertwining male and female fates and hinting at the complexity (and perhaps inevitability) of their connection.

Caroompas complicates this battle of the sexes with historical and moral overlays. The grid-like lower half of the painting is decorated with needlepoint fish, alluding to traditional “women’s work”. Meanwhile, the repeating oval frames inscribed with “Amor” and featuring capsized ships suggest the doomed voyage of romantic love. The painting was completed in 1985, the same year the Titanic’s wreck was famously rediscovered.

Other elements deepen the critique of puritanical moral structures. The ducking stool, visible in the central ringed map, was a medieval punishment device used to shame outspoken women publicly. Its inclusion recalls how women like Hester Prynne were punished for the same sexual behavior celebrated in men. The map itself, with its winding blue lines and marine symbols, evokes the brook of The Scarlet Letter, which Hawthorne personified as “talking” about the solemn experiences it must have witnessed, whispering secrets and sorrows like Hester’s own repressed feelings.

Ultimately, the painting is not a simple feminist triumph of woman over man. Instead, it stages a complicated duel of equals: Hester cocks her gun, Zorro brandishes his sword, both ready for battle, their gazes locked in tension.

Fairy Tales: Red Riding Hood

1988

Acrylic on canvas, 82 x 82 inches

CSUF Department of Visual Arts Permanent Collection, Gift of Cliff Benjamin

[Accession No: 2023.000609]

Fairy Tales: Red Riding Hood is a turbulent, sensuous, and intricately orchestrated narrative in which myth, trauma, and feminist revision collide. Painted in 1988, the work rejects the Grimm brothers’ tale as a simple cautionary lesson about disobedience and reframes it as a passage of danger, repression, and awakening. Caroompas refuses to sanitize the fable; she restores its violence and ambiguity, exposing how cultural myths about girlhood are saturated with warnings, punishments, and prescriptions for female behavior.

Traditionally, the Red Riding Hood story warns girls of the perils of straying from the prescribed path, with both Red and her grandmother punished for deviation. Caroompas translates this theme into visceral imagery of control and consequence. Sexuality, she suggests, is policed by cultural norms that cast women’s bodies as sites of risk. In the painting, overlapping figures embody those dangers: a terrified blond doll, cradled in the hands of a young Asian girl, suggests the unwanted burden of reproductio n,

while a red clay mask draped over a shrouded female figure evokes both ritual and death, a chilling reminder of mortality tied to desire.

Caroompas broadens the fable’s framework by interweaving Eastern and Western cosmologies. On the left, Kali, goddess of destruction, entwines with Shiva, God of creation, as a serpent coils between them. This image recalls both Hindu mythology and the serpent of Eden, a symbol of forbidden sexual knowledge in the West. At once generative and destructive, the coupling stages sexuality as a threshold between life and death.

In the corner, a woman dangles a set of keys. They double as innuendo, recalling chastity and Caroompas’ own studio object, a medieval chastity belt she kept as a sculpture. The keys become emblems of patriarchy’s elaborate mechanisms for restricting women’s autonomy.

Rather than an ultimate warning, the painting transforms the Red Riding Hood tale into a meditation on passage and possibility. Caroompas herself described her “Good spirit diagrams” as sigils of change, shifting from white to red to mark transformation. This is not a triumphant vision of sexual empowerment but a sober reflection on the cycle of trauma, repression, and eventual self -soothing that often shadows female sexuality. Anchored by the yin-yang of the I Ching, the composition culminates in a vision of sexual awakening as a universal process: the mingling of masculine and feminine energies, life and death, fear and renewal.

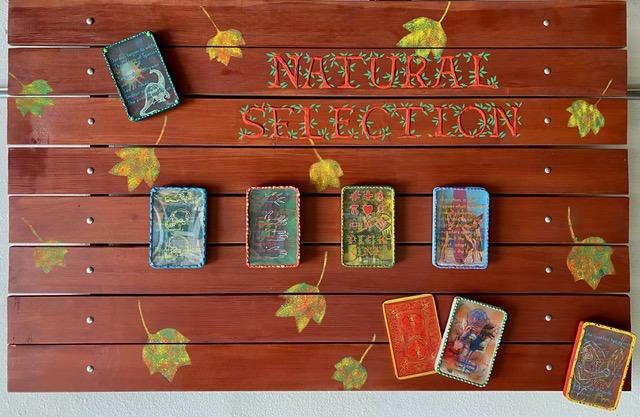

Natural Selection

1984

Acrylic, ink, wood, Plexiglas, found illustrations, 37 x 60 x 3.5 inches

CSUF Department of Visual Arts Permanent Collection, Gift of Cliff Benjamin [Accession No: 2023.000610]

Natural Selection is a complex mixed-media assemblage that stages the precarious game of romantic relationships as an evolutionary contest. The work’s title invokes the biological concept of “natural selection,” but its inspiration is even older: stanza 56 of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s In Memoriam A.H.H., written before Darwin formalized the term. In Tennyson’s poem, the phrase “Nature, red in tooth and claw” evokes a universe governed by brutal competition: a vision of a God who seems to have doomed all life to predatory struggle.

Caroompas seizes on this idea to reflect on human relationships, especially romantic ones, as similarly fraught with desire, competition, and ruthless selection. The work’s structure mimics a wooden picnic table or game board, complete with slats and scattered leaves. This surface doubles as both a natural setting and a stage for play. The words “NATURAL SELECTION,” painted in leafy, decorative lettering, suggest that life is a rigged contest: like a magician’s “pick a card,” it offers the illusion of choice while fate remains fixed.

Mounted across this surface are nine framed “cards,” each a small, intricate world of painting, collage, and text under Plexiglas. The cards are layered with imagery ranging from dinosaurs and pilgrims to tarot symbolism and pinup girls, highlighting both evolutionary science and human storytelling. Several cards focus on extinction and evolution. The green-framed dinosaur card contains references to Darwin, cacti in a desert, nostalgic song titles (“September Song,” “Bed of Roses”), and road imagery. In this card, romantic longing is rendered fossilized, a passion driven to extinction. Other cards overlay scientific diagrams of skulls, eyes, and evolutionary sequences with phrases about genetics and environmental molding, underscoring that our bodies and desires are shaped by forces beyond our control.

Elsewhere, her cards evoke spiritual reckoning. One red-bordered card shows The Hermit from tarot and pleads, “Heal my body, forgive my sins, o saint of dangerous and desperate causes,” suggesting pilgrimage and moral bargaining. Another shows hands shuffling cards, an image of apparent freedom that conceals how much fate is constrained by the choices at hand.

A satirical take on American pioneer mythology emerges in a card featuring pilgrims with guns and church spires behind them, paired with text describing adaptation as “weeding out the less fit.” Caroompas merges the language of evolutionary biology with colonial conquest, highlighting the brutality of each.

Gendered ideals of beauty and competition appear with particular force in the bright blue “Surfer Girls” card. Three bikini-clad women lounge with a giant pink surfboard in a tableau of mid-century Californian fantasy. But the text beneath complicates this carefree image with talk of adaptation and survival: “Crusaders approach. Weed out the less fit.” The term “bikini” itself alludes to the Bikini Atoll nuclear tests, the origin of the swimsuit’s name, and the idea of the woman as “bombshell,” highlighting the fusion of sexual allure with destructive power. The artist’s selection of pinup imagery thus comments on how women are packaged as objects of desire while carrying the threat of violence.

Other cards further blur the boundary between play and peril. Scientific drawings, pilgrims with weapons, pinup girls, tarot symbols of death and fate, and hands performing magic tricks or shadow puppets all populate this strange tabletop stage. Her use of Plexiglas to seal these images reinforces their status as artifacts or specimens: preserved evidence of cultural anxieties about love, competition, and gender.

Throughout, Caroompas deploys the logic of the card game or magic trick. “Pick one,” the piece seems to say, offering choice while quietly rigging the outcome. This reflects the illusion of freedom in romantic relationships and social roles: lovers may feel they choose freely, but their options are shaped by evolutionary drives, cultural expectations, and deeply coded stories. The leaves scattered across the tabletop underscore this natural cycle of growth, decay, and predation, while the entire staging reveals it as a social performance.

Natural Selection belongs to a period in the mid-1980s when Caroompas was especially interested in gaming and cards as metaphors for sexual politics and romantic entanglement. By framing lovers as animals in a battle for reproductive success, she both adopts and critiques evolutionary language. Her work asks: Are relationships acts of mutual care or covert combat? Is our sense of choice real or illusory? And how much of what seems “natural” is actually cultural storytelling that normalizes competition and hierarchy?

By fusing poetic allusions, scientific references, spiritual confessions, and pop-cultural imagery, including the darkly charged “bombshell” appeal of bikini pinups, she creates a work that is seductive and unsettling. Natural Selection is not only a meditation on love’s competitive nature but a critique of the conceptual apparatus that makes such competition seem inevitable. It exemplifies her commitment to interrogating the myths and metaphors that shape our most intimate relationships and asking us to see them for what they are.

The Diamond 1985

Plexiglas, acrylic, mixed media, and Masonite, 37.5 x 25.5 x 10 inches each (triptych)

CSUF Department of Visual Arts Permanent Collection, Gift of Cliff Benjamin [Accession Nos: 2023.000607.01, 2023.000607.02, 2023.000607.03]

The Diamond is a psychologically charged triptych that uses the form of the window box to explore entangled themes of love, power, and moral reckoning. Through Plexiglas layers, painted figures, and carefully positioned text, Caroompas constructs a three-part visual narrative where symbolism and narrative loop back on themselves, collapsing distinctions between personal myth and cultural iconography.

In the left panel, the diamond takes center stage, both as a geometric puzzle and a conceptual metaphor. Referencing Chapter 16 of The Scarlet Letter, which Caroompas also visually engaged in her painting Hester and Zorro: In Quest of a New World, the panel quotes a conversation about the nature of the diamond: its brilliance, hardness, and the fact that only another diamond can cut or polish it. This becomes a metaphor for relationships between equals, particularly romantic or creative ones, where tension and refinement emerge from friction. Superimposed numbers in a diamond configuration suggest a kind of game or riddle. At the heart of this panel lies a question: Can two people equally strong, or equally sharp, find harmony?

The center panel escalates the metaphor. A lone male figure dressed in flannel stands between two rocky cliffs, holding a lasso as if trying to mediate or restrain the coiling red and blue snakes beneath him. The snakes, rendered with vibrant, almost mythic energy, are entangled, mirroring the relational chaos between two powerful forces. The background text, “The cardinal rule of Paradise: Watch where you put your feet,” directly warns of trespassing and temptation. The use of the word “cardinal” plays on both religious and chromatic meanings, recalling the red of The Scarlet Letter, the red of sin, and the red of seduction. She invokes the iconography of the American frontier, a moral wilderness where the rules are unclear, and control is an illusion.

The final panel on the right brings the confrontation to a head. Two men, one older, one younger, face each other amid a backdrop of surreal foliage, winding serpents, and symbolic overlays. A disembodied

feminine hand, its nails painted red and wearing a diamond ring entangled by a ring-necked snake, floats overhead. Text reads:

“13. You are spending too much time in idle conversation / 14. Remember: A brilliant mind, like a gem, needs polishing.”

Carole spent an exceptional amount of time, energy, and dedication to perfecting her concepts and introspecting in her studio. She had the belief that these methodical practices were necessary for any artist. Part of this discipline is asserted in this card. These phrases introduce a critique of distraction and wasted energy but also reinforce the diamond as a symbol of refinement and internal strength. The snake, often linked to temptation, becomes both protector and captor of the jewel, offering a feminist double reading of danger and agency.

The interplay between word and image, seduction and constraint, reflects her signature approach: layering personal mythology, feminist critique, and literary symbols to build a complex visual argument. The snakes, diamonds, and red accents unify the panels thematically and visually, creating an internal logic that loops between desire and defense, beauty and danger.

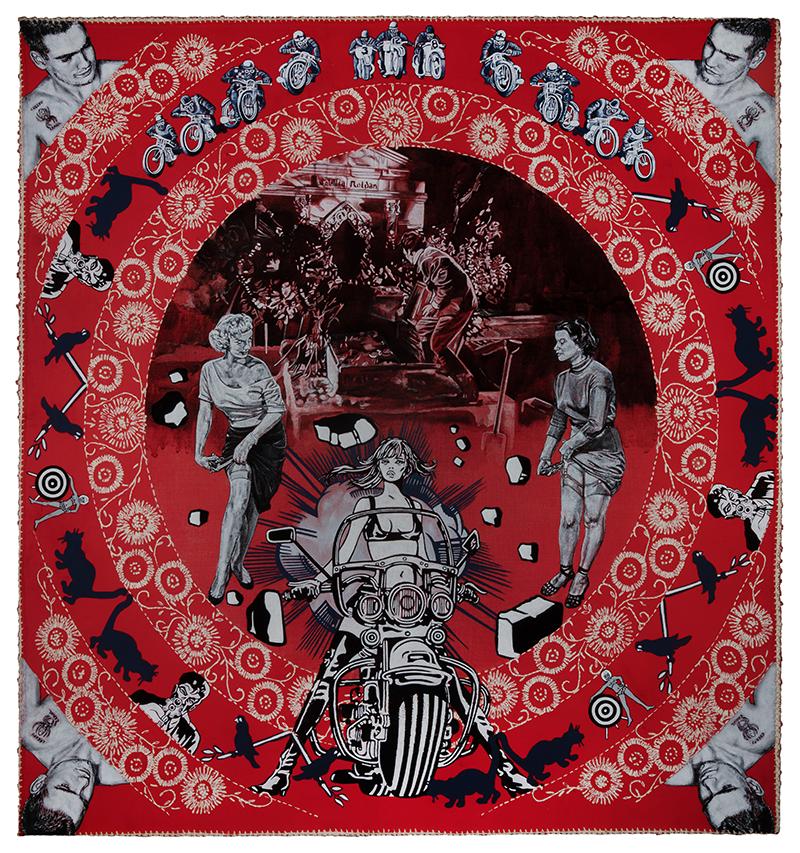

Heathcliff and the Femme Fatale Go On Tour: Dead or Alive 2001

Acrylic on found embroidery on canvas/panel, 32 x 30 inches

From Private Collection

Heathcliff and the Femme Fatale Go On Tour: Dead or Alive stages a collision of literature, pop culture, and feminist critique. In this densely layered painting, embroidered lace becomes a shooting target, biker culture meets Emily Brontë’s Gothic novel, Wuthering Heights, and archetypes of female sexuality burst through the picture plane. It is at once playful and menacing, seductive and destructive, a meditation on how women are seen, and how they can seize control in being seen.

At the center of the composition, a comic-book biker girl rides directly at the viewer, her hair flowing behind her, rubble cascading around her. This figure, both eroticized and defiant, represents Cathy from Wuthering Heights, reimagined as a 1960s “biker babe” in a bikini. Rather than languishing as the object of desire or tragedy, Cathy explodes forward, threatening to break through the canvas itself. Caroompas asks: What happens when the woman long positioned as the passive object of the gaze becomes the agent who looks back?

Caroompas’s series of paintings, Heathcliff and the Femme Fatale Go On Tour (1998–2001) uses Brontë’s doomed lovers as starting points, filtering them through twentieth-century subcultures and feminist theory.

In this work from the series, Heathcliff is represented metaphorically as punk icon Henry Rollins, the brooding frontman of Black Flag and the Rollins Band. Like Brontë’s Heathcliff, Rollins embodies intensity, anger, and an outsider’s raw masculinity. Her choice of Rollins collapses literary and punk mythology, framing the male lead not as a Byronic hero but as a restless, rebellious figure. In the background, Heathcliff digs Cathy’s grave, a direct nod to one of Wuthering Heights’ most chilling passages, when he demands that Cathy haunt him beyond death.

Surrounding the central rider are figures drawn from vintage film stills: gun-wielding femme fatales with garter holsters, modeled on Hollywood mega-stars Jane Russell and Marilyn Monroe. The two central female characters recall Hollywood archetypes of the 1940s and 1950s, women whose potent sexuality was inseparable from their fame. Caroompas does not simply reproduce them; instead, she recontextualizes them within a target pattern, reminding us that these women, as much as they menace the viewer, are marked and contained by the male gaze.

Laura Mulvey’s foundational theory of the “male gaze” posits that women in cinema exist as the objects of a presumed heterosexual male viewer. Caroompas inverts this logic. Here, the gaze does not merely objectify the women; the women return it, armed and defiant. The biker girl crashes forward, a femme fatale draws her gun, and even motifs like cats and crows seem alive with menace. The painting suggests that female sexuality, when uncontained, can be explosive, capable of destruction as well as empowerment.

Integral to the composition is the embroidery itself: a thrifted tablecloth repurposed as a painted surface. Caroompas collected hand-tatted lace and domestic textiles, artifacts of women’s labor traditionally associated with patience, craft, and propriety. By painting over this embroidery in red and transforming its circular patterns into bullseyes, Caroompas both honors and weaponizes women’s work. The lace, once decorative, becomes a target and a reminder that women’s accomplishments have historically been undervalued, dismissed, or made vulnerable to attack.

The painting is saturated with symbols of threat: targets, guns, knives, and crows perched on broken stakes. Violence here is inseparable from seduction. The central biker girl dazzles with sexual charisma, yet her energy seems dangerous, even apocalyptic. Caroompas presses us to ask: what happens when female sexuality is “weaponized”? Does it empower women, or does it lead to their destruction? The answer, she suggests, is both, and therein lies the haunting power of the femme fatale.

The original working title for the piece mentioned in Caroompas’s notebooks was, Heathcliff and the Femme Fatale Go On Tour: Wanted Dead or Alive. That phrase evokes both the Western outlaw and the fate of Brontë’s heroine Cathy, who is most powerful in her absence, as a ghost, a memory, or a haunting presence. Caroompas seems to question whether artists, too, become larger-than-life after death, their absence amplifying their myth.

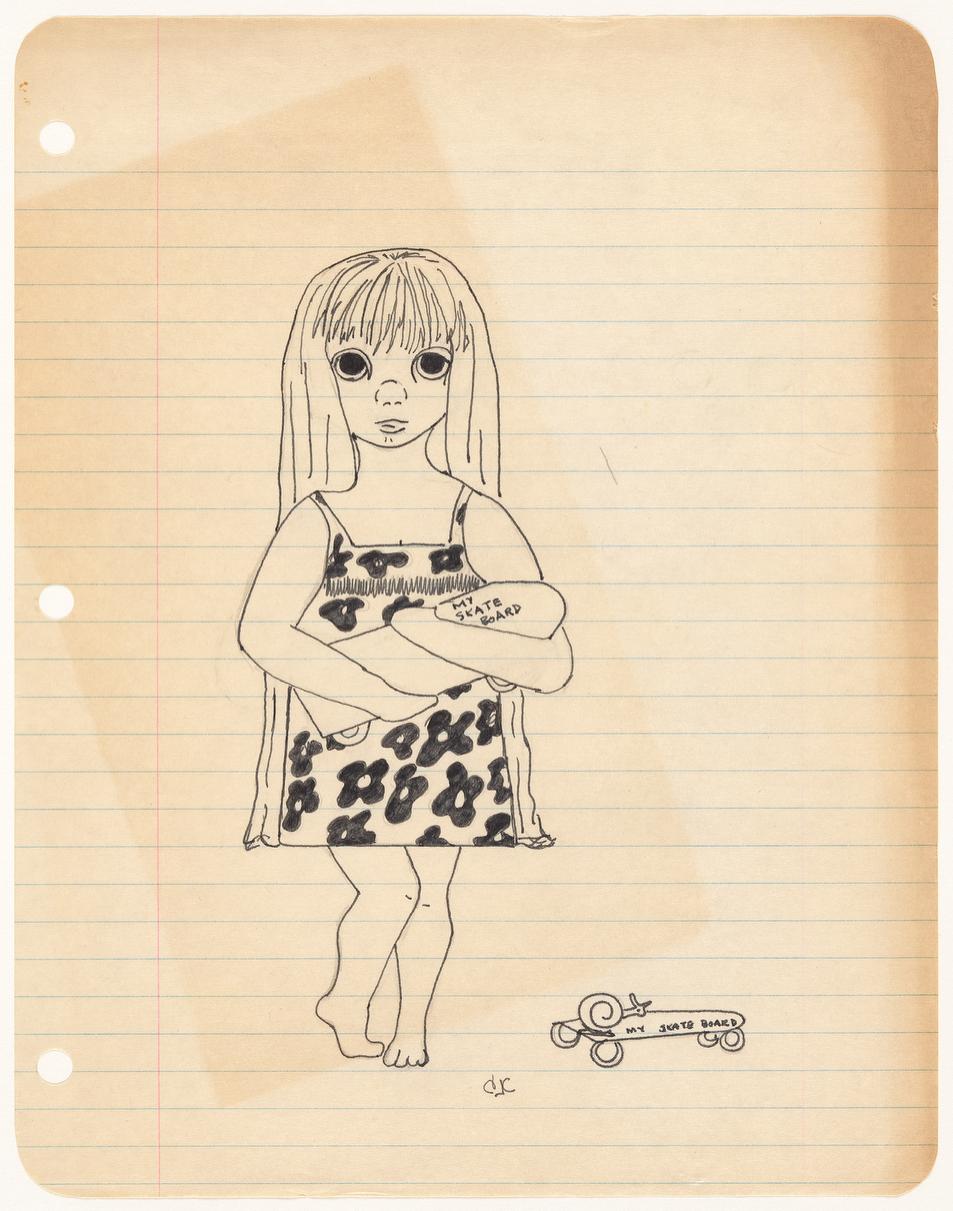

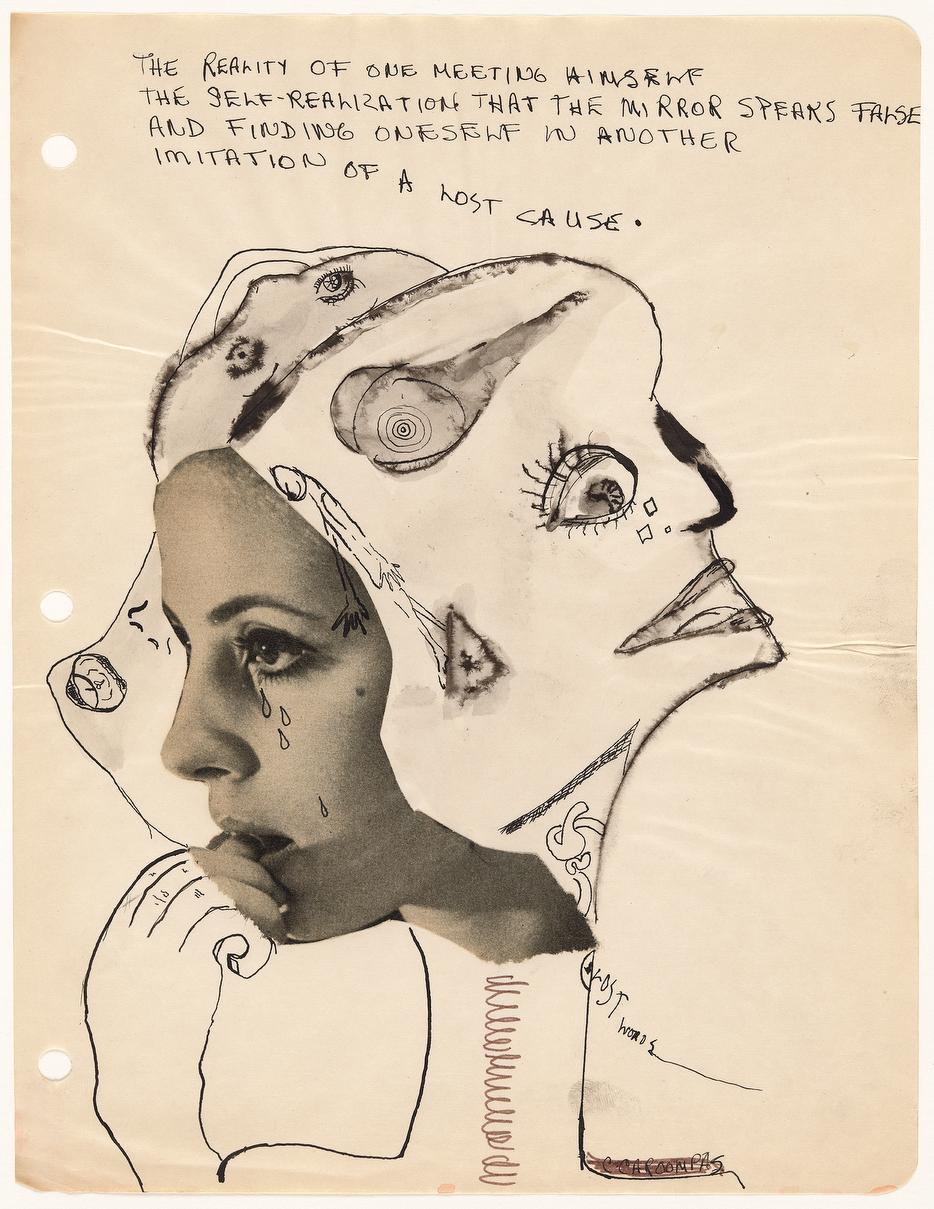

Early drawings by Caroompas, c 1960s – 1970s

Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles