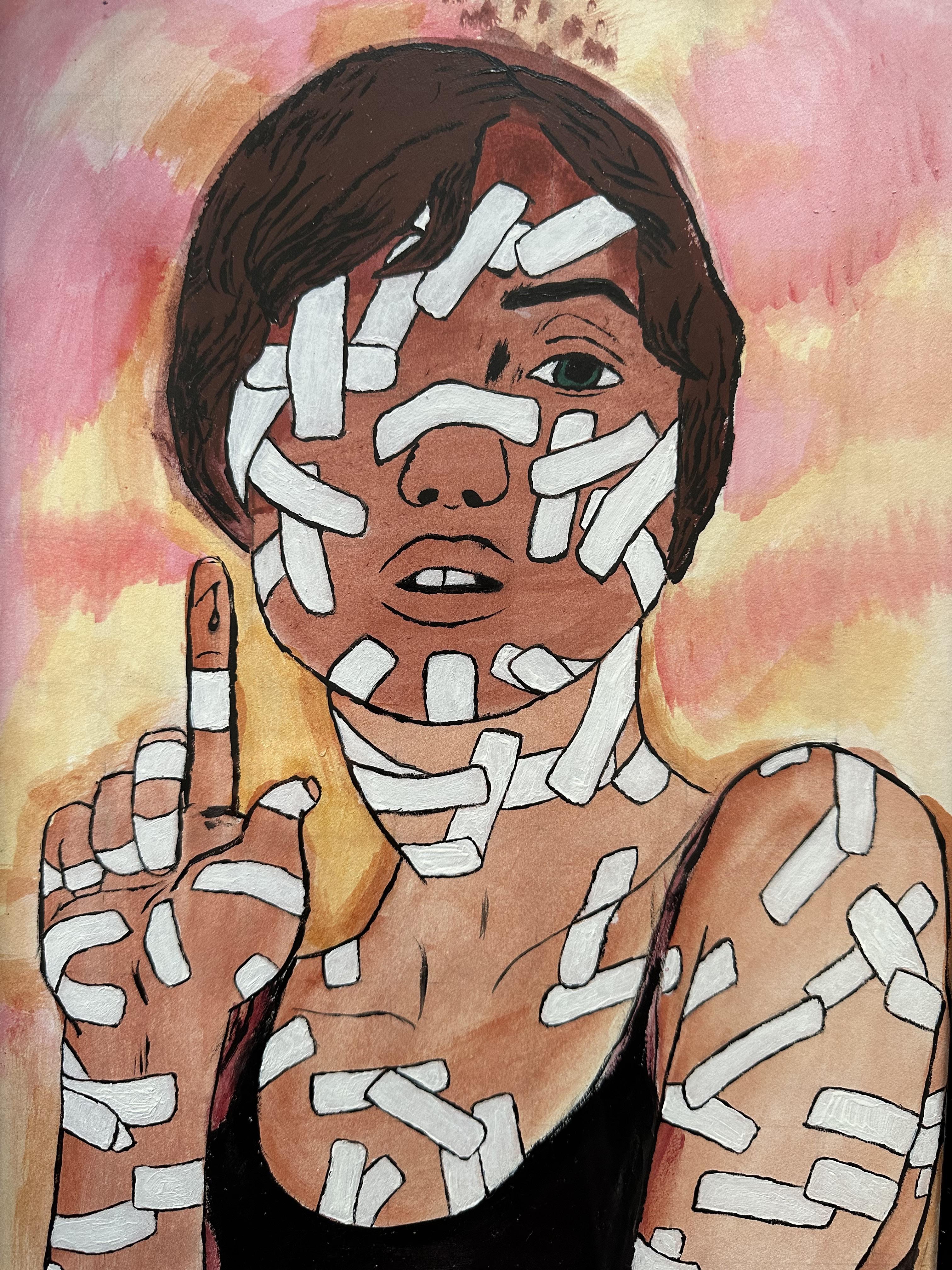

Cover Art

Catherine Taghizadeh

Revealing and Healing

Watercolor and ink on paper

Editors

Bretta Nienow

Carolyn Dean Wolf

Clarice Douille

Daniel Nguyen

Katherine McGuire

Kevin Ahn

Michael Hoenack

Reviewers

Nicole Piemonte, PhD

Karina Kletscher, MLIS

Tracy Leavelle, PhD

Rachel Mindrup, MFA

Letter from the Editors

Thank you for taking the time to browse this edition of our publication. Within these pages, you’ll find candid reflections from medical students navigating the challenges of pre-clinical studies, the profound and personal experiences of patient interactions during clinical rotations, and the ways these journeys shape both ourselves and those under our care. Our aim is to underscore the vital role of empathy, compassion, and authentic human connection within the healthcare sphere. We would like to take you out of the routine practice of medicine, prompting selfreflection on the transformative nature of these shared experiences with patients.

Through this vehicle of medical humanities, we have established a space for introspection and contemplation. We invite you to immerse yourself in these perspectives, contemplate your own experiences, and unite with us in nurturing a more compassionate, humanistic paradigm of healthcare.

While You Were Sleeping

Saad Khan

You are twenty-six years old, and you have a brain tumor. Here you are now, sitting in your personal pre-op bay, a thin gown failing to keep you warm as your bare skin finds little comfort against the scratchy white linen running rough against your back. Uncertainty looms over the next fourteen hours. You didn’t expect to be in this position – and who can blame you? Nobody ever does until it’s them. All sorts of folks pull back the curtain and talk to you–some of what they say makes sense, some of it doesn’t. Some of them look as young as you. Your bed starts forward with a jolt. All you see is the ceiling above, sterile tungsten lights flashing by one-by-one until you are wheeled into the arena. You think you’re calm, but the leads and wires stuck to your chest betray the truth of your heart. The medicine feels warm like sunshine in your arm as it flows into your veins. All fades to black – this is where your memories end. You won’t remember when your breath stopped and the breathing tube went in

“You think you’re calm, but the leads and wires stuck to your chest betray the truth of your heart.”

to keep you alive. You won’t remember being poked and prodded with needles as lines and tubing were fed into you. You won’t remember how you became nothing more than an inanimate body, flopping and drooling as you were rolled onto your belly. You won’t remember your skull being pinned and a window cut out of your bone. You won’t remember the calculated violence. You won’t remember when the tumor bled and bled and bled and brain disappeared beneath blood, nor will you remember how the surgeon stopped the bleed and took out the tumor. You won’t remember being pieced together, stitch by stitch, the scar running from your temple and around your ear. You won’t remember the nurse taking a blue cloth and washing your blood-covered face. You won’t remember how she combed your hair, how she laid a clean gown and warm blankets over your body. You won’t remember the restoration of your dignity, your humanity. You won’t remember your first breath off the vent, or the ride back to the bay. All you will remember is your eyes fluttering open as you return to yourself, relieved that it’s over.

Arrival

Digital photograph, edited with Adobe Lightroom

Stone Zhang

Why We CareReflections on The Art of Examination

Hyun Mok (Sam) Kang

Imust begin with a confession: I failed to read the fine print when signing up for my humanities elective. When I initially chose “The Art of Examination,” I assumed we were going to learn the art of “physical examinations” better – basically, I was hoping to hone my clinical skills. I was thrilled when I secured a spot through the lottery, thinking I’ll be a better doctor because of it. Little did I realize that the word “art” in the course title actually referred to visual art.

Several M2s who took the course hinted at the slight chance that I would be drawing models who would be scantily dressed, my face turned blue (or so I think). The only undressed people in my life for the past ten years were my own toddlers during bath time, and I wasn’t ready to meet one that’s way too grown, let alone draw their figure! I went into the very first class disgruntled, skeptical, and betrayed. Lesson certainly learned: always read the fine print.

Nevertheless, the profound lessons I learned in this course will be with me for a long time.

In the class, much of our focus was on gaining a different perspective, primarily that of the patient. Through various assignments and exercises, we delved into how our interpretations

of data could differ significantly from person to person, what it feels like in the waiting room, and what it’s like to be exposed and observed closely, like what a patient experiences during a clinical encounter. These perspectives were not groundbreaking in-and-of themselves; I had experienced them as a patient, and I’m sure many more have. However, it was refreshing to encounter these perspectives as a medical student.

Despite all the insight gained in the course, I remained somewhat unconvinced. Did I really need to be told what a patient’s experience might be like? What would I gain from considering the patient’s feelings and thoughts during an encounter? Even if I were to understand and see things from the patient’s perspective, there were practical concerns. Would I have the time to “slow down” with dozens of other patients waiting and charts to write? After all, patients will come because I have something to offer that can solve their problems, so why bother trying to be more “human” with them? In essence, why have compassion if competence is what truly matters?

My skepticism likely stems from the idea that doctors are like mechanics who repair cars. You take your car for a routine inspection, and the mechanic identifies issues, runs

tests, provides a diagnosis, and gives you an estimate. You don’t need to befriend the mechanic to get your car fixed; you just need them to do a good job. If you sense the mechanic is incompetent or attempting to deceive you, you look for another one. The relationship is purely economical. In a way, some might say, a doctor’s visit is like taking your car to the mechanic. You’re not there to socialize with the doctor. You’re there because you have a problem that needs to be fixed. Nonetheless, it’s obvious that fixing cars and treating patients are fundamentally different, and it just doesn’t feel right or fair to liken physicians to mechanics despite the similarities. There’s something that feels cold, mechanical, and even abrasive when the patient becomes a mere broken object, something to fix and set right. When we treat patients in such a manner, we lose their humanity – and in losing their humanity, we lose our own.

economical transaction – a trade of goods. In contrast, by caring, the tools and skills of medicine become extensions of our humanity. The scalpel in our hands takes on spirit, breathing life into the body it touches. In other words, when we care, we offer the patient the respect and dignity they deserve, and this allows us in return to honor our own dignity. This reciprocity of giving and receiving the gift of humanity connects and unites us. It adds a beautiful dimension to the

a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit— immortal horrors or everlasting splendors… Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbor is the holiest object presented to your senses”1. Patients or physicians are not lifeless objects. In truth, we all are immortals.

“By not caring, we relinquish our humanity, becoming akin to a mechanical extension of the lifeless tools we employ.”

By not caring, we relinquish our humanity, becoming akin to a mechanical extension of the lifeless tools we employ. The clinical encounter is diminished to a mere

encounter that is deeply fulfilling and enriching. We begin to see both the patient and the physician for who they genuinely are– not as means to an end, not as commodities, not as objects to dissect or repair, but as two equally beautiful, living, thinking, and feeling beings, created in the Triune image of God. As C.S. Lewis eloquently put it, “There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilization— these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of

In the Art of Examination, I learned that caring for our patients isn’t a distraction from our competence; it’s an essential component of it. As we genuinely care, we become more than the sum of our skills and tools; we become conduits of empathy, compassion, and understanding, which ultimately unites and uplifts both the physician and the patient. The lessons learned in the course weren’t about drawing. The point was to recognize the profound beauty of the patient-doctor relationship, which blooms from the shared journey between two immortals toward health and well-being. I feel proud and blessed to be a part of that journey.

1Lewis, C. (1949). The weight of glory, and other addresses. New York: Macmillan.

Carolyn Dean Wolf

Untitled Digital photograph

Ihonestly did not expect to break down when I did about the loss of a patient. Nor did I expect to be mourning a patient who was very much still alive. I was sitting at the kitchen counter giving my mom a raving review of the latest “veggie salad” sandwiches she had made when she stopped and asked why I was crying. I paused, felt the wetness on my face and, though none of my patients had died, I knew exactly who I was mourning. Whose wishes I was mourning. The first time I grieved for a patient was for a woman who had said nothing to me the entire time she was in the hospital, except that she wished to go home. Because of a psychiatric condition, she would not be doing that any time soon. That was something I may not have expected to grieve, but I did.

As I sat there with my family, I could not help but think about my fellow peers on the internal medicine rotation and how they must be struggling with the realities we were now facing. Realities that no warnings could truly prepare us for, and I thought of what we could do. After reaching out to a mentor, I had come to a decision that

The Wish

Nadia Khan

perhaps we could benefit from a chance to mourn those we had lost together and out loud. So I started to organize a memorial with the help of many faculty and other students. When the day came, I was absolutely moved watching my peers share their grief and talk about the suffering they had seen. I heard stories about patients on hospice and those facing death alone in silence. I heard stories about patients who could not afford life-saving care and patients who were animated and excited one moment and lost to us the next. I learned that grief was like an ocean: silent and lonely at times and turbid and terrifying at others. Reaching out to others felt like finally being able to take a breath without fear of completely drowning.

At the end of the memorial, we wrote on wish paper our hopes and the things we never got to share with those we lost. When we would burn the wish paper, I wanted to send my patient’s wish to go home up into the sky. I hoped more than anything it would come true, because now, that wish for her to return home had become one of my own.

Show Some Skin

Clarice Douille

Iknock on a door, slide it open, and greet the patient. On my family medicine rotation, I’ve been very surprised to almost always see patients fully clothed. In our preclinical years, we get used to seeing standardized patients in gowns and wearing minimal clothes.

Are we doing a disservice to patients by not having them in gowns for many of our visits? I think we miss so much when we keep patients “comfortable” and in the clothes they come to the office wearing. I know we are under time constraints and cannot address every concern that a patient presents with, but I think we can do better. We can get a better idea of our patients’ overall health and do more preventative medicine if we

saw more skin.

Sitting in a gown in a cold doctor’s office isn’t ideal for patients–it’s inconvenient and a nuisance–but it allows doctors to do a better physical exam and scan the body for abnormal moles, spots, or rashes. We can find clues to what the diagnosis is and any systemic manifestations of disease.

The patient population we work with at Valleywise is very vulnerable with many barriers to care, so we might be the only doctor patients see. We need to do what we can for patients and maximize our efforts when they come for a visit. We can easily miss a relevant physical exam finding that is hidden underneath clothing. The time it takes for patients to take off jackets or roll

up pants while in the room with the doctor could be more effectively used to visually scan their skin for abnormalities.

Instead of opting out of putting a gown on, patients have to advocate to opt-in to undress and put a gown on. If it was framed that you can put on a gown for a more thorough physical exam, what would most people choose? I believe a surprising amount of patients would choose the thorough exam rather than staying in their street clothes.

doctors to have chaperones more often? Economically, clinics might see less benefit because cloth gowns need to be washed and paper gowns are a one-time use. A patient’s clothes can also tell us more about each person–who they are and how they live–and remind us that each patient is different whereas a standard patient gown removes individuality.

knowledge to know what is abnormal or concerning, and then to express these problems. In reality, they might not understand what actually sets off alarms in our head and is relevant information for their doctors to know.

“A good physical exam is the cheapest test we can perform. Can we afford to lose this skill?”

Of course, there can be downsides to pushing gowns on patients who may feel uncomfortable. This intervention can be hard because telling people to get undressed puts the vulnerable population we serve in potentially compromising positions. People may feel less comfortable talking to their doctor undressed and be less forthcoming with information. Even if we are doing basic physical exams, would being gowned prompt

Family medicine is the point of entry into medicine, so if other specialties aren’t looking at the entire patient–from cradle to grave–we need primary care to pull this weight. There were countless patients that I know likely had edema that I didn’t check due to pants that couldn’t be rolled up well, or spider angiomas, or acanthosis nigricans, or dysplastic nevi, or countless other issues that I didn’t notice for one reason or another. We rely on patients having enough

In medical training, we become comfortable getting histories and ordering proper lab screenings, but the physical exam is one thing we are underutilizing to diagnose and address illness and disease. Clothes cover up a lot of the story of the patients sitting in front of us. We really have to take our patients as a whole into consideration and make the most of the limited amount of time we have in each visit.

So even though a good history is vital to get to a diagnosis, the physical exam should be prioritized. A good physical exam is the cheapest test we can perform. Can we afford to lose this skill?

Lesson in Compassion

Julia Shabanian

“You remind me of my daughter. She died eight years ago.”

My patient smiled at me through eyes filling with tears.

“Melissa” was my first patient of the day in OBGYN outpatient clinic. As I read through her chart before meeting her, I saw she was here to follow-up on her hormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms. This seemed straightforward enough; I assumed it would be a quick visit. I step into her room, introduce myself, and start asking her about her symptoms.

As a third-year medical student trudging through rotations, balancing clinical responsibilities with studying and life, it’s easy to forget that practicing medicine is a profoundly human experience. Am I coming off as a capable medical student to my

attending? Do the residents like me? Was the patient history I took comprehensive enough? Yet, certain patient encounters stay with me. They remind me why I chose to pursue medicine in the first place. Medicine is more than being able to apply a knowledge base and technical skills. It is an exploration of compassion, empathy, and the little threads that connect us as human beings.

My conversation with Melissa quickly shifts away from medical questions to when she interrupts me to tell me that I speak like, share mannerisms with, and look so much like her late daughter. She confides in me that losing her child has been the worst pain she could have dreamed of experiencing. I listened as she told me about her daughter. Together, we shared this moment of grief.

Medicine is personal, and it is a privilege to be able to connect with patients. I am grateful to Melissa for reminding me.

Carolyn Dean Wolf Untitled Digital photograph

diabetes and no insurance

Talal Alomar

During my internal medicine rotation, I was assigned to the case of a patient who had been referred to us from the Emergency Department, her primary concern being a perianal abscess. As I delved into her medical history and scrutinized her laboratory results, one alarming detail stood out like a crimson flag: her blood glucose levels were alarmingly elevated. It was a disconcerting chorus of déjà vu that echoed through the hospital corridors. “Another uncontrolled diabetic,” my resident remarked with a sigh of resignation.

With a sense of duty that weighed heavily on my shoulders, I embarked on a journey down the labyrinthine hallways of our hospital, ultimately arriving at Room 109. With a measured tone, I introduced myself. “Hello,” I began, “I am a medical student and a member of the medical team assigned to your care. Can you please share with me what’s been happening?”

The patient, well aware of her diabetic condition and the consequences of its mismanagement, revealed her predicament with a degree of resignation that was heartwrenching. Her history was marred by recurrent perianal abscesses, a painful testament to the collateral damage wrought by her uncontrolled diabetes. When I inquired further, she confided, “The times I don’t have insurance, I

can’t see a doctor. And the insurance I have now, no office will accept.” Her words, laden with the weight of despair, resounded off the sterile walls which enclosed us.

As I continued my conversation with the patient and conducted a thorough examination, I couldn’t help but reflect on the inescapable quagmire she found herself in. Her healthcare challenges were not limited to her perianal abscess; they extended into a disheartening nexus of financial struggles, familial anguish, and a perpetual cycle of emergency department visits borne from a lack of access to regular care. The healthcare system, which is supposed to serve as a bastion of healing and support, appeared to have failed her.

“The healthcare system, which is supposed to serve as a bastion of healing and support, appeared to have failed her.”

In this poignant encounter, the stark juxtaposition between patients with different insurance statuses became abundantly clear. Later that same day, we had another patient with Medicare insurance. The contrast in the medical team’s attitude was striking as a senior physician casually remarked, “Oh, he will have no problem getting meds. Prescribe whatever you want.” This contrast served as a stark reminder of the inherent disparities within our healthcare system.

In medical education, the emphasis is often placed on clinical acumen, diagnostic skills, and treatment modalities, but the multifaceted impact of socioeconomic factors on patient care remains underrepresented. The influence of monetary constraints on healthcare decisions is a complex and nuanced topic that is seldom explored in the confines of textbooks or medical curricula. Yet, the difference between an insurance policy that covers essential medications and one that does not can be a matter of life or death, ultimately determining whether a medical condition is effectively managed or left to fester into a cascade of deadly complications.

The woman in the ED, caught in the unforgiving web of insurance limitations, serves as a poignant reminder that the issues plaguing healthcare are not merely clinical or diagnostic but deeply entwined with socioeconomic disparities. Her plight should motivate us to advocate for more equitable access to care and to address the systemic deficiencies that perpetuate such heart-wrenching scenarios, ensuring that every patient, regardless of their insurance status, receives the quality care and support they deserve.

“What more could I have done?”

Mitchell Johnson

Still a somewhat fresh third-year medical student, I started my internal medicine rotation at the VA. I had heard mixed experiences about the VA, but mine was a pleasant surprise. The team I worked with was amazing, and the patients were kind, spunky, and loved to chat, which I enjoyed. Of the patients I worked with, I had the pleasure of caring for a gentleman who was admitted for hypertensive urgency and remained admitted for declining kidney function in the context of chronic kidney disease. He lives alone and works from home repairing vintage radios sent to him from all over the country, and he takes pride in his work. He is a movie buff, and most of our time together was spent criticizing recent movies and TV shows. I looked forward to talking with him every day.

Throughout his hospitalization, his kidney function continued to decline despite adequate treatment, prompting serious conversations about the possible need for dialysis to help his already failing kidneys. He was adamant about avoiding dialysis at all costs and was willing to do anything but that. His tone during this conversation was mostly that of anger and denial. Over the next few days after the initial conversation about dialysis, it was becoming more of a reality that it would be needed. One morning, while pre-rounding, I found the patient lying in his bed staring at the ceiling. When I asked him how he was doing, he turned to look at me, and, in a defeated voice, asked me a question that I often reflect on to this day:

“What more could I have done?”

I was taken aback. There were many things running through my head that I could tell him, like that his kidney disease was likely due to his poorly controlled diabetes, but I didn’t feel it was appropriate to tell him that in this situation. Instead, I told him I was sorry and that we would do everything we could to help him in the here and now. I’m not sure how much the conversation helped either him or me.

There are many problems that are difficult to manage within the field of medicine, like hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, and COPD, just to name a few. Even more broadly, this can apply to life, as well, such as the death of a loved one, the turmoil of having a new baby, or even something as simple as getting cut off in traffic. Of the majority of problems we deal with in our life, I believe there is a helpful solution in relieving, or even avoiding, pain and suffering that my patient taught me at the VA. That is, perspective.

are someone who believes this is the only chance we have on Earth, perspective– or the lack thereof– plays a significant role in our everyday choices. Perspective allows us to see the end of the road and how our choices will affect our futures and even those around us. If every person had perspective, perhaps there would be better patient compliance to treatment regimes, better diets, longer lifespans, emergency savings for rainy days, better retirements, and overall a better quality of life.

“Perspective allows us to see the end of the road and how our choices will affect our futures and even those around us.”

Whether you are someone who believes that there is more to this life than the mere 80 or so years we have to live, or if you

My heart ached for my patient who was suffering from regret and uncertainty, and I did all I could to help alleviate not only his physical pain, but his emotional pain, as well. Now that I am on to new rotations, I do not know how this patient is doing, and perhaps I never will, but I will never forget the friendship we had and the lessons he taught me. As I sit in my living room watching my 15-month-old daughter play with her kitchen set, I have a vision of my future, lying on my deathbed surrounded by my children and grandchildren, who lived fruitful, happy, and healthy lives, and being able to ask them not “what more could I have done?” but rather tell them, “I have done all that I could”.

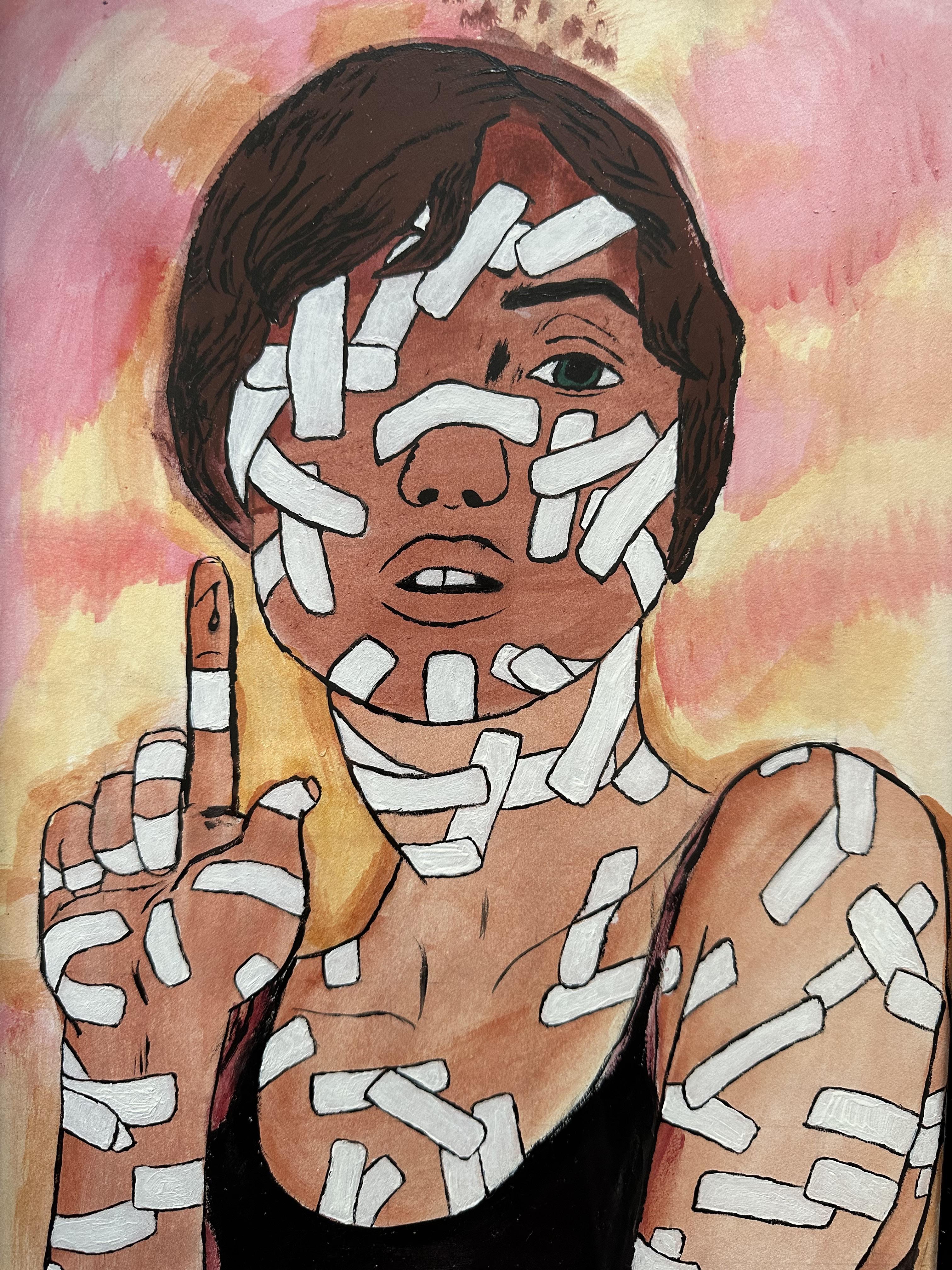

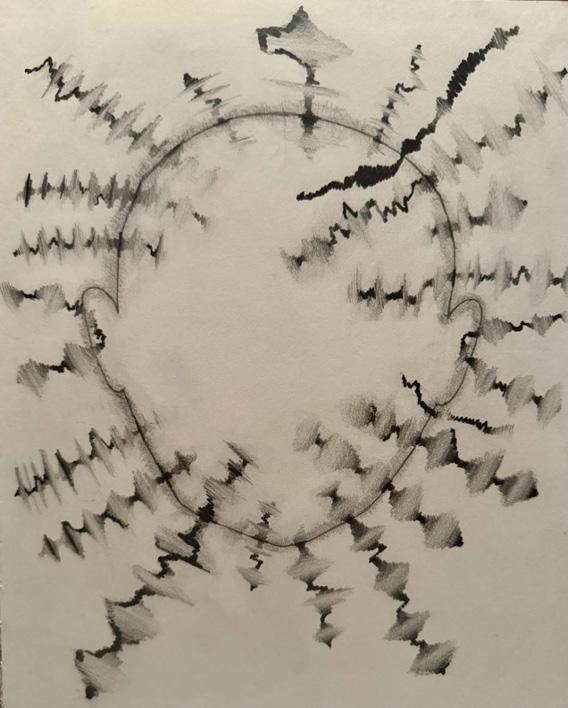

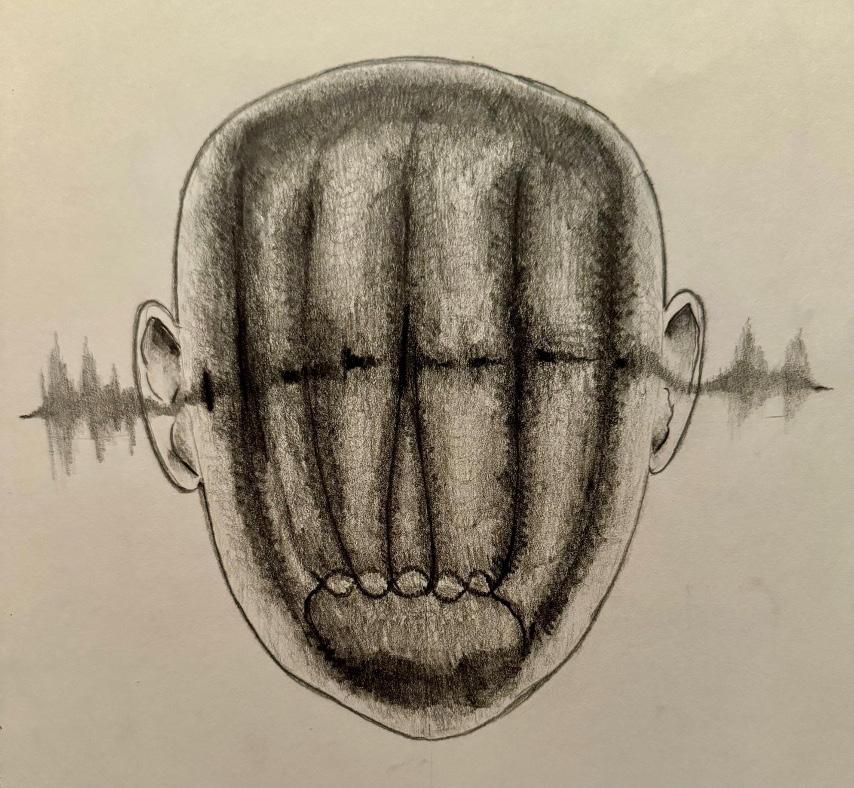

Overstimulation: Part 1

Pencil on paper

Anna Denman

The Incarceration of a Hernia

Malik Salman

Thrown into the clinic room without the opportunity for a comprehensive chart review, I went in to get the history and physical of a 51-year-old man presenting with an incarcerated inguinal hernia. I opened the door to find a man clad in an orange jumpsuit, handcuffed and shackled, sitting uncomfortably in a chair. A police officer stood watchfully in the corner of the room, his hands resting on his utility belt. I could immediately sense an uneasiness running through my body as I stepped into a situation I was not prepared for.

While pre-clinical coursework in the medical humanities can teach you the social determinants of health, they don’t always teach you how to navigate them. As I interviewed the patient, I found that he was unfazed by the officer’s presence. He spoke candidly about the symptoms he had been experiencing for the past year and asked how surgery may affect his sexual functioning. As for myself, I couldn’t help but feel the officer’s glare from the corner of the room.

As the patient awkwardly stood up in his shackles to pull down his pants for the surgeon to examine his hernia, questions ran through my head. What happened to patient privacy? What degree of confidentiality is this man entitled to? How does he feel as he’s being examined in front of an officer, student, and surgeon? Who decides that his hernia is bad enough to see a surgeon? Who pays for his procedure? Who schedules it? How will his recovery look?

The patient’s journey into the surgical suite unfolded against a backdrop of societal challenges. His physical restraints, both symbolic and literal, bore witness to a life marked by adversity and confinement. He

wouldn’t get to know when his surgery would be scheduled, as that would pose a security concern. His right to privacy would be constantly limited by the presence of an officer wherever he went. The American taxpayer would be funding the cost of his surgery. Finally, and certainly most concerning for the patient, was that his recovery would certainly be hindered by his incarceration.

The scheduled surgery, initially set a month away, took an unexpected turn when the patient presented to the emergency room in excruciating pain the next day. His hernia had become strangulated and needed immediate repair. In the operating room, we were once again followed by the officer, whose presence was a constant reminder of the interplay between healthcare and the legal system. As we operated, we found that one foot of sigmoid colon had herniated into his scrotum. His delay in care for so long was an unfortunate result of his incarceration.

Post-surgery, ethical questions lingered. How can the principles of medical ethics be applied to ensure the well-being of a patient who has been confined by societal constructs? His incarcerated inguinal hernia became a metaphor for the barriers that extend beyond the physical ailment. The operating room became a stage for addressing not only the patient’s immediate medical needs but also the profound implications of his life circumstances.

Most of my ethical questions remained unanswered after the patient’s care was completed, but I learned that you don’t always need answers to some questions. Sometimes asking them is enough to ensure that you acknowledge the intricacies of humanistic medicine.

The Elderly: Underserved and Unknown

Graham Grisedale

Isat next to the bed of one of my residents. His chest heaved with the struggle of each breath. No one knew his past, his family, or most importantly his story. Some even hinted that he had been homeless before he was brought in. John had arrived at our nursing home from the hospital with endstage pulmonary failure and was considered “terminal.” Unlike the others in the nursing home, he had few visitors and could not communicate with us other than simple phrases, so we were unable to learn his narrative and past. Within a couple of weeks, he started to severely decline and began the process of dying. As was the procedure where I worked, once someone begins the dying process, a nurse calls the family and they come to visit for the final hours; yet, this time, there was no one to call. A man who spent more than sixty-five years on

“As one of the nurses eloquently stated, ‘With the passing of each individual, a volume of history is lost.’”

earth–a son, a brother, a husband, maybe even a father–had no one there for him in the end. His death was tragic and lonely, and sitting with him, I reflected on my own mortality and the failed state of elder care in America. Shortly after my shift ended, we were notified that he passed away. As one of the nurses eloquently stated, “With the passing of each individual, a volume of history is lost.” That is the hard part of working in a nursing home– all of your residents pass away. Some may have years remaining while others may only have days. Either way, we owe it to the residents to provide exceptional care and proper resources for the rest of their lives, and many care homes are struggling to do that.

After graduating from college, I had the opportunity to work as a CNA in nursing homes for the majority of my gap year. Throughout college and volunteering, I learned about

many different underserved groups in medicine–immigrants, minorities, socioeconomically disadvantaged people, and rural communities–and the work being done to aid them in their journey to health.1 However, once I started my job, it became clear that there is another group of underserved individuals that do not get nearly as much attention, and this group will continue to grow with the aging of the Baby Boomer generation: the elderly. During those months at the nursing home, when people asked me where I worked, they would immediately respond with something along the lines of “Oh, that must be really hard,” or “I’ve heard being a CNA in a nursing home is the worst.” While it certainly did have its ups and downs, this stigma pulls people away from profession and detracts from all of the wonderful residents you may meet and the wisdom to be learned from them.

Still, there are a number of problems in geriatric healthcare that must be addressed in order for this stigma to be seriously challenged. The United

“These personal connections not only kept me going in times of burnout, but they also kept the residents going because living in a nursing home is challenging for most.”

States government spent approximately $900 billion dollars on Medicare related expenses in 2021, and that number will certainly continue to grow each year as people are living longer due to better medical care.2 In addition, geriatric physicians are in very short supply, and the Department of Health and Human Services estimates a shortage of nearly 27,000 geriatric physicians by 2025.3 Of course, this problem will likely be worse in rural areas leading to further strain on the system, also causing stress to the patients because of the uncertainty of their future. Furthermore, Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement

rates for nursing homes are significantly lower than the prices they charge for private payers and can lead to nursing homes trying to discharge people to make space for private payers in order to maintain desired profit margins.4 As a result of the financial pressures nursing homes face, many choose to cut costs by paying low wages to staff and reducing staff-to-patient ratios.

Worsening working conditions lead to burnout as a result of overwhelm and lack of professional fulfillment and in turn, resident care suffers across all levels. As a personal example, I once worked 86 hours over a seven-day period. Another time, due to a staff shortage, I was responsible for 27 residents during my 12 hour shift. Not only was this medically unsafe, but also personally unsustainable. It is no wonder why the burnout rate is so high, considering these experiences occurred

at one of the “better run” homes that I worked at.

After six months of work experience, CNAs can turn to agency work where they make better wages and control their exact schedule. I did this too when I moved to a new city and was horrified by what I encountered.

I learned that the “good” nursing homes typically do not need agency CNAs because they are able to keep a full staff. When I arrived for my first day of agency work and introduced myself, they just handed me a list of things without so much as a short welcome. They also did not even have the respect to refer to residents by name, only their room number. Sadly, many of these struggling nursing homes are staffed by a majority of agency CNAs, meaning there is a revolving door of employees and thus no continuity of care, nor any meaningful relationships built with residents and their families. This lack of continuity has drastic consequences for patients, families, and care providers alike.

Despite systemic issues in geriatric care discussed above, my experience as a CNA working with the elderly still held so much value in the opportunity to build relationships with unique, diverse, and wise residents with fully lived lives.

“It is up to us to promote true change because the current model often fails to respect the dignity of the person and does not provide adequate resources for their care.”

Tragically, they often have no one to talk to, which made my job of listening all the more important, especially when there was COVID in the nursing home and visitors were not allowed. One of my favorite residents was valedictorian of his high school,served in the Army during the Korean War, and was married for 72 years. Another resident was a huge fan of KU basketball, and even had a framed letter from Bill Self on her wall and watched every game. Yet another was proud to have hit a buzzer beater for his basketball state championship in high school! Listening to their personal

narratives and how they got to their current position taught me the importance of community. These personal connections not only kept me going in times of burnout, but they also kept the residents going because living in a nursing home is challenging for most. Being able to connect about something as simple as the score to the game opened up conversations that allowed me to recenter myself in the midst of an overwhelming shift. It allowed me to provide compassionate care to my residents who were depending on me. Many residents sadly passed away, taking with them a wealth of stories, knowledge, and experiences, but I was glad to have been a part of their lives.

Overall, nursing home work is very difficult due to resident deaths and staffing, but it is also the most rewarding. I had the privilege to meet so many incredible people who truly shaped our country, and to help them during their last months, weeks, days, and

hours into the conclusion of their earthly journey. In terms of the future, I am no economist or government official, but we need to do better. We as medical professionals can start by (1) learning about each patient through meaningful conversations to build a stronger understanding of their needs, (2) increasing awareness of this glaring lack of coverage in our health system, and (3) speaking to agents of civil change about patient care injustices when we witness them. We are failing our older generations by placing them in short staffed and underfunded nursing homes. These issues will be compounded as the elderly demographic grows, and as the next generation of doctors, we will face the burdens of this issue. It is up to us to promote true change because the current model often fails to respect the dignity of the person and does not provide adequate resources for their care.5

1U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Underserved Group - toolkit. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. https:// toolkit.ncats.nih.gov/glossary/ underserved-group/#:~:text= Underserved%20

groups%20refer%20to%20 populations,more%20 or%20the%20included%20 categories.

2NHE fact sheet. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS.gov. https:// www.cms.gov/data-research/ statistics-trends-andreports/national-healthexpenditure-data/nhe-factsheet#:~:text=Historical%20 NHE%2C%20 2021%3A,17%20percent%20 of%20total%20NHE.

3U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. 2017. National and Regional Projections of Supply and Demand for Geriatricians: 2013-2025. Rockville, Maryland.

4What to do if a nursing home is pushing for discharge but you don’t agree. Medicaid Planning Assistance. (n.d.). https://www. medicaidplanningassistance. org/nursing-homeevictions/#:~:text=Nursing%20 homes%20may%20 attempt%20to,well%20as%20 those%20on%20Medicare).

5Jervis LL, Hamby S, Beach SR, Williams ML, Maholmes V, Castille DM.

Elder mistreatment in underserved populations: Opportunities and challenges to developing a contemporary program of research. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2016 AugDec;28(4-5):301-319. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2016. 1245644. PMID: 27739929; PMCID: PMC5560611.

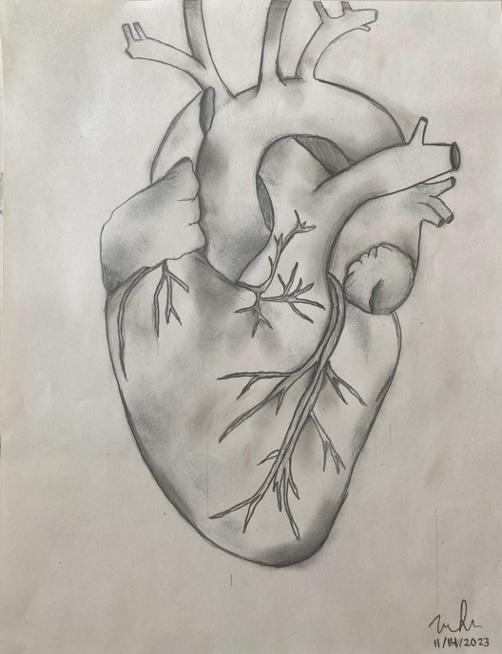

Anna Denman

Overstimulation: Part 2

Pencil on paper

strawberry ice cream

Caroline Doyle

Early mornings do not scare me.

Nor do local dive bars nor grocery store trips. Yet something within them mocks me.

They evoke a heavy, sinking feeling. And truthfully, I feel this burden in most everything I do. They somehow call in my ear: “Where’s your lover?”

I’m so tired of this voice inside my head. Loneliness is my very own monstrous, invasive beast. His sole purpose is to feast upon my daily life.

Each small dream of possibility becomes haunted by his reality.

Sleepy half-smiles appear on our faces, as our intertwined hands resistantly let go. But actually, an alarm screams it’s time to get up and start another day by yourself.

We drink a few beers, while standing hip-to-hip in a comfortable chatter amongst the noise. Instead, I get a little too drunk, and stumble home nearly in time for the stream of tears.

He pushes the cart, and grabs the Tillamook strawberry ice cream, just for me. You know damn well nobody cares about your favorite brand and flavor.

School is no safe haven. His constant whispers become a sounding drum down the halls. A tiring day of study is met with no partner-given relief.

Medicine feels heavier on those who pursue it alone.

He reminds me how much I crave this love-filled mundane existence. And then he rips my imaginings to shreds.

I loathe him.

A Bout with Self-Doubt

Sahil Sandhu

As I wrap my hands and don my gloves I approach the heavy bag Unbidden thoughts surface

A bombed quiz

My left hook smashes the bag 20% on today’s UWorld

A vicious right sends it careening

As I let loose a flurry of blows I couldn’t help but consider who my imaginary opponent was A bag? Or a sense of inadequacy?

We all feel it from time to time Life chips at us daily stripping at our perseverance our sense of worth

Medical school on top of that? It often feels akin to a boxing bout against an indomitable opponent and they’re not pillow-fisted

They wail on us with a barrage of blows pick us apart with the pressure punishing the slightest mistakes with targeted stunning strikes

Against such a superior opponent it’s about going the distance rolling with the punches to survive, learn, and move on

A bad performance may make me feel low Make me question my value as a person But one day or round doesn’t define me I am much more than that

My violent meditation complete I take a break and catch my breath Failure is not final There is always the next day

The next round

Lily Goodman Leo

Digital, using ProCreate on iPad

The Children Answer.

Bretta Nienow

We are the children you wish to nourish. You wish to give us what you had, what you gave, what you were, what you missed and what you wish to erase.

We will ask you to listen, for the answers you demand. Bleeding hearts breathe understanding unknown. Listen to the chorus of our unexpected wisdom echo around you, as we tell you what brought us to life at this time.

We will teach you to release the past bygone, to trust as you longed to trust your Selves as children. The world invented may not be reality gifted.

Remain hopeful, keep open, love the child you were. Celebrate in, exploration, discovery, uniqueness, diversity. Accept life evolving, observe Humanity progress. Allow time and life its way.

Respectfully, sincerely. The Children

Harmony of Strength: A Single

Megan Witsoe

Mother’s Tale

In a town where dreams seemed to fade, Lived a woman burdened, her spirit unswayed. Three little ones, clinging to her side, A single mom’s journey, a turbulent ride.

Her days were filled with struggles untold, A story of resilience, of a heart so bold. With each sunrise, a battle she’d wage, Fighting for a life, page by page.

An appointment loomed, a date with concern, To the OBGYN, she was meant to return. But wheels of fate can be cruel and unkind, No transportation, no solace to find.

The healthcare office, stern and cold, Judgment cast, stories left untold. “Why are you late?” they coldly inquired, As the woman stood, her spirit tired.

With eyes cast down, she spoke her truth, Of limited means, of the struggles uncouth. A single mom’s journey, a tale so dire, Yet, they couldn’t see, their hearts afire.

For she cleaned houses, heavy with life, A mother’s love, a relentless strife. Pregnant and bleeding, yet she’d toil, For her children’s sake, she’d burn and boil.

In the silence that followed, judgment did wane, The healthcare office, the truth did attain. A single mom of three, with one more on the way, In a world that judged, she found her say.

Compassion replaced the cold, steely stare, Understanding bloomed, like flowers in air. The woman, a warrior, in life’s brutal art, A canvas of strength, stitched with a mother’s heart.

For in her struggles, a beauty emerged, A symphony of resilience, a tale submerging. No longer just a patient, a number in line, But a beacon of strength, a story divine.

The healthcare office learned, as the story unfurled, That every soul carries a burden, a world. And in the heart of compassion, a lesson was sown, A story of a woman, strength overthrown.

The gift

Emily May

I can never know you, but I have looked beneath every part of you that has ever been touched or loved.

I have studied intently to know your muscles, your vessels your nerves. But I will never know you.

Instead, I imagine you. How you talked, how you laughed, if you sang.

I wonder about every you that has ever been, at two, at thirteen at twenty-five.

I inspect your hands and wonder about everything you touched and every thing you made.

I can’t think of anything more your own than the body you gave so that I may learn, may heal.

I feel undeserving to be one of the last people to touch you before you return to the earth, to the sky, to the ones who love you. To the ones who know you.

I imagine your family, and I imagine you as a part of mine. I hold your hands like I imagine your grandchild would, and I gaze upon your face to memorize it as everyone who has ever loved you has tried to do.

April Cooke

Hands across generations Film

An Ode To The Physician Who Got Me Here

Ashley Becker

You believed in me

Before you knew who I’d be You supported me

Dermatology

Meeting people where they’re at Was your life’s passion

For seventy years You kept practicing, serving And inspired me

I was accepted And you were so proud of me You already knew

I would follow you In this path of medicine To learn and to serve

“I’m jealous of you,” You would often say to me, “I would go back now!”

I’d share my stories When I’d come home on my breaks You’d always smile

Recently, things changed After one hundred one years You have now passed on

Without your guidance

The constant encouragement I would not be here

So an ode to you And to all those before you Who make us who we are.

Thank you. You are always with us.

Final Moment

Matt Lawler, 2026

As a healthcare worker, you never forget the first time you experience the death of a patient. Hospice provides a unique service to help patients and their loved ones navigate a terminal diagnosis through symptom management and interdisciplinary support. Working with the hospice patient population has helped me realize that physical presence is vital. We must really be there for these vulnerable patients and their grieving families to ensure a peaceful death devoid of unnecessary suffering.

Pastel on paper

Digital photographs of yarn

Art of tying knots: practicing for tying sutures.

Morgan Hopp

I started crocheting as part of a volunteer project in elementary school. I was eight years old. It was really just an opportunity to learn how to do something and hang out with the older kids at school. I became really interested and really enjoyed it and found that I had quite a way with yarn and a hook. Over the past decade and a half, I have continued to crochet, mostly self-taught, with the occasional class, and YouTube video here and there. I use it as a way to express my creativity to unwind from the stress of life, and to give some kindness and comfort to someone else. For the most part, I only make baby blankets and full-size blankets, but recently I have been testing my abilities and teaching myself how to crochet, right-handed in an effort to build my deck for the operating room. My right-hand projects are much smaller, more like hats and coasters. It’s a running joke amongst friends and family to find out if I have more yarn or more textbooks in my apartment at any point in time.

Working on my right-hand dexterity through crocheting allows me to use my hobby and relaxation to both build confidence and technical skill for my future as a surgeon. Although the knots in the OR are less visible, and definitely not as pretty of a final project to show off, I guess you could say I’ve been learning to tie knots to take care of others for 15 years.

The Heart of the Community

Maya Samuel

When I see the word “heart,” I think of two things: the symmetrical shape representing love, as well as the organ that keeps us all alive. I always wondered how the human heart, an organ, came to represent love. Greek philosophers believed that the heart carried our strongest emotions. Aristotle claimed that it was the source of love, anger, pain and courage. As many others, I now associate the heart with such feelings as well. When I think of the heart and its relation to medical humanities, I think of the heart of physicians, nurses, and the rest of the medical community. I see the love, the anger, the pain, and courage they carry with them as they help their patients. They are committed to their patients. They advocate for their patients and provide compassionate and empathetic care through the toughest of times. They are the heart of the community.

Pencil on paper

Idiopathic Altruism

Madison Ransdell, 2020

The image depicts whiteboard art done on an inpatient psychiatric unit by the author during her time as a C.N.A. during the pandemic of 2020. To her, this captures the concept of going “above and beyond” the call of healthcare staff to make patients going through difficult times comfortable. Additionally, there is a deeper meaning in the quote depicted in the image. The text mirrors that of the DSM-IV criteria for Major Depressive Disorder: A condition that can be theorized to be brought on by selfinflicted mental pain due to the intense desire or inability to find mental clarity from a problematic or unjust previous experience.

Digital photograph

Idiopathic Altruism

Diagnostic Criteria 729.01 (F20.5)

A. Five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 1-month period and represent a consistent disposition; at least one of the symptoms is either (1) self-sacrificing behaviors or (2) going out of one’s way to understand the mental or physical state of others.

Note: Do not include symptoms better attributed to another psychological predisposition

Marked increase in behaviors to aid or promote the mental or physical satisfaction of others at either no cost or at cost to the individual.

Feelings of guilt due to unequivocal social standing, although deserving out of effort.

Understanding the ethical principles of mutualism and reproductive fitness.

Fatigue from the added mental and physical effort.

The individual has the cognitive ability to understand cost-benefit analysis to the self but continues to assist others out of innate emotional and physiologic response.

B. The signs and symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

C. The signs and symptoms are not better explained by another medical condition and are not better explained by another mental disorder.

Note: Criteria A-C represent a moral human.