Human ConneCtions

Ivanna Tang

Beautiful Death, 2021

Graphite on paper

Bretta Nienow

Carolyn Dean Wolf

Clarice Douille

Daniel Nguyen

Katherine McGuire

Kevin Ahn

Michael Hoenack

Nicole Piemonte, PhD

Karina Kletscher, MLIS

Tracy Leavelle, PhD

Thank you for taking the time to browse our publication. Inside, you will find thoughtful reflections on a range of topics: the experiences of medical students as they move through the struggles of preclinical years, try to touch the lives of our patients as we start on the wards, and the ways these affect both ourselves and those we take care of. While doing so, we aim to highlight the importance of empathy, compassion, and the human connection in healthcare. We would like to take you out of the routine practice of medicine and help you reflect on the changes in yourself as you go through similar experiences.

Through our exploration of medical humanities, we seek to create a space for reflection and introspection. We invite you to engage with the material, to consider your own perspectives and experiences, and to join us in cultivating a more compassionate and humanistic approach to healthcare.

It’s 3 o’clock on a Friday, and I drag my eightypound keyboard down the fourth-floor hall of Mercy Council Bluffs Hospital. Having sacrificed arm strength for medical knowledge, this is no easy task. However, I must admit that I have become quite adept at weaving in-andout-and-between nurses, physical therapy teams, and food carts while only stubbing a few toes along the way.

Ivanna scouts ahead with her guitar slung over her back. When the nurses spot us in our eggplant-purple shirts with “music volunteer” printed across the back, I bet they are thinking: “Will we hear ‘Country Roads’ again?” Patients ask for country music about eighty percent of the time. Unfortunately, that’s the best we’ve got at the moment for that genre.

“Knock-knock! Hi, I’m Ivanna.”

“And we’re music volunteers. Would you like to hear any music today?”

A quick glance at the whiteboard tells us our patient’s name is “John.” He’s propped up in bed wearing a pale blue hospital gown. He looks at us but doesn’t speak. John’s wife, Mary, reclines on a gray sofa on the other side of the room, with her glasses pulled down to the bridge of her nose, head propped up on her hand, and legs crossed. Her eyes flicker up to us: they bounce from her phone, to her husband, then back down to her phone. There is darkness under her eyes and fatigue in her voice as she replies, “Sure, we like music. Go ahead.” So, I play Kabalevsky. When I finish, Mary claps. Half of John’s face lifts in a grin.

“That was quite lovely,” says Mary. “What else do you have?”

“How about some country?”

The familiar chords of “Country Roads” fill the room. Mary taps her thigh to the beat as we sing, and John leans forward a little.

“That was fun, we love that song!” exclaims Mary as we finish. “What else do you know on the piano? Those classical pieces were beautiful.”

Ivanna plays some Chopin. Mary closes her eyes; her head and shoulders rock back and forth with the rhythm. Her phone rests next to her on the couch cushion, with the screen face down. As Ivanna finishes, Mary opens her eyes, looks at John, and tenderly remarks, “We love music, don’t we, honey?”

John dips his head in agreement.

Mary continues, “We put some on every night. All sorts of music. Mozart, The Eagles, Elvis... We haven’t had music like this since we were last home.”

We had practiced an Elvis song seemingly just for this moment. Ivanna begins plucking on her guitar.

Wise men say only fools rush in, but I can’t help falling in love with you.

A long, low sigh sounds from the couch.

Shall I stay? Would it be a sin?

The cushions rustle as

she pushes off her seat to pad across the room to her husband in bed.

If I can’t help falling in love with you?

There’s the sound of sniffles. I peek up to see the glisten of tears on their cheeks. Mary is gently embracing and rocking her husband, crooning softly with the melody. John looks up at his wife and, for the first time, rasps,

“Is this real?”

Mary chokes out a wet laugh. “This is real. This isn’t a dream.” She places a kiss on his forehead.

As John and Mary share this moment, the hospital walls disappear. They are taken to a place where nothing else matters except their love for each other. In this moment, I realize that I am witnessing a different form of healing. I am witnessing a healing of the soul, a moment where the current circumstances no longer have power over our new friends.

As we finish, we sit in silence for a moment. “Is there anything else we can play for you?” offers Ivanna in a small voice.

Without looking away from her husband, Mary replies, “I

think we have all we need.”

I was once asked, “What role do the humanities play in medicine?” and I squeaked out that I couldn’t give a good answer. Apart from saying that the humanities— art in its different forms— touches the soul in ways that physical medicine can’t, I still can’t quite put it into more words.

What is music, especially in a hospital bed? For some patients we visit, it is entertainment. To John and Mary, it is an escape. A visit home—to times where the radio rumbles old tunes and the couple sway together on their worn living room carpet. And when it ends, sober acknowledgment of what has come to pass and the uncertain road ahead. Sometimes, music is an intrusion. One fellow, when asked if he wanted some music, replied with the most incredulous “why?”

I would be satisfied leaving it at this: music can express yearnings of the heart where spoken word often fails and provide healing for the soul where medicine falls short.

“In this moment, I realize that I am witnessing a different form of healing.”

Ibabysat two rowdy elementary school boys my first summer out of college. One morning, I strapped them into their car seats to visit their cousins in the suburbs. We left Chicago early and made it to their cousins’ suburban neighborhood by midmorning. The neighborhood was luxurious: quite the opposite of Chicago’s close-cut city streets. Outside our car, perfectly manicured, lush green lawns bordered multi-million-dollar homes. Wealth oozed from the sidewalks like the peanut butter and jam on the boys’ sandwiches I’d made for breakfast.

The cousins’ house was no less grand than its neighbors, the inside straight out of a Restoration Hardware catalog. I wasn’t surprised. I knew their aunt was a doctor and their uncle worked as a lawyer, so the spotless white couches and modern minimalist furniture seemed fitting. But as we pulled into their pristinely organized four-car garage, I couldn’t help but feel overwhelmed by the perfectionism of it all (my family home has always been the epicenter of chaos). Even their kids, the cousins, were neatly dressed and wellbehaved.

Then I saw it. At the doorway into the garage, there was a gigantic, messy, glorious pile of spilled coffee. The nanny mentioned that the mom, an OB-GYN, had been rushing off to work. That dark liquid mess immediately comforted me. I couldn’t pinpoint why back then, but I know why now.

So much of the journey to medical school

breeds anxiety and perfectionism. I’ve developed a habit of getting frustrated with myself whenever I slip up or make a mistake. But the most important lesson I’ve learned is to embrace my imperfections. My test scores might not be pristine; my white coat might sprout an extra wrinkle or a new coffee stain overnight. I might run late to a meeting because I spent too long talking to a patient. But a crucial part of sustaining this crazy lifestyle is recognizing my present and future shortcomings—celebrating them, even. Flaws are what make us relatable and loveable. The sterility and meticulousness of medical spaces have, for too long, ostracized patient populations who don’t feel at home within white-washed hospital walls. Who knows? That extra wrinkle on my white coat might be what comforts and reassures my patient that I too am human—just as that spilled coffee did for me so many summers ago.

No matter how perfect people’s lives might seem, we’re all messy and relatable somewhere. I love that part of life and people. Sometimes (most of the time), I’m an absolute mess in the mornings as I ride my bike to school. Maybe I had a flat tire, forgot my stethoscope, or am behind on Anki; the permutations are infinite. But every time I start to feel frustrated at my imperfections, I think about the spilled coffee in that perfect house. I smile instead. The most important skill medical school has taught me is to accept my flaws and shortcomings. Oh, and to invest in coffee cups with lids.

Eleanor Johnston

“That extra wrinkle on my white coat might be what comforts and reassures my pateint that I too am human...”

On a quiet October morning, I embarked on a journey to St. Vincent de Paul’s Annual Kidney Screening Event with high hopes and a desire to learn. As a first-year medical student, I was eager to use my skills to serve the community and make a difference in the lives of the uninsured.

As I arrived at the event, I couldn’t help but be struck by the potential for change that lay before me. Phoenix, the fifth largest city in the US, is home to many uninsured residents, and with St. Vincent de Paul’s central location, this event had the potential to reach and help many.

I was impressed by the hard work of the organizers and the dedication of the volunteers who had set up the venue and were eagerly awaiting patients. At first, a few patients trickled in one at a time, bringing hope that the day would be a success.

And yet as the hours drifted by, the ebb and flow of patients was all ebb and no flow. The venue remained largely empty. Most volunteers sat around idly. Despite the event organizer’s tireless efforts, attendance was low, with less than half of the registered patients showing up. It served as a reminder of the ongoing challenges of providing accessible healthcare to the uninsured population in Phoenix and the need for

continued efforts to bridge the gap.

While I had some understanding of the challenges faced by uninsured individuals in accessing healthcare, this experience at the kidney screening event was truly eye-opening. It made me reflect on the importance of accessible healthcare and the obstacles that must be overcome to achieve it. It reminded me that while we may make progress, there is always more work to be done.

I reflected on the significance of efficiency in healthcare and the need to seize every opportunity to assist. I reflected on how every second counts in the fight to provide accessible healthcare, that even the smallest changes can hold

tremendous potential for transformation. In particular, I thought about the impact that incremental improvements in efficiency could have on making healthcare more accessible to those in need. How many more

patients would our screening event have benefitted had the registration and transportation logistics been streamlined?

But amidst the disappointment, there were also moments of hope. I saw the community come together to provide for the uninsured— people from all walks of life donating their time and resources to support this important cause. Some were medical

professionals who provided free services, while others were volunteers who helped with registration or translation services. Together, they created a supportive and welcoming environment for uninsured individuals to receive the care they needed. I witnessed the strength and wisdom of the organization in setting up this event, and the altruism of the healthcare community as they came together to serve those in need.

The journey to provide accessible healthcare is not just about the destination, but also the journey itself. It’s about the effort, the hope, and the potential for change. It’s about the humanity in medicine and the power of the collective will to make a difference in the lives of others.

“The journey to provide accessible healthcare is not just about the destination...it’s about the humanity in medicine”

It should be close. Happiness, that is. Not yet achieved but promised on the other side of this education. Four years of carrying around a perpetual backache, heavy bags under my eyes, and guilt from minimal phone calls home were endured for a purpose. Yet I feel no different, even as the diploma, title, and profession have finally come into vision. The breath of air I had been promised is nowhere to be found.

Anger floods my body, soon replaced by disappointment and melancholy. Perhaps I am not close enough. If I give myself a year of residency that might do the trick. The promise of success and achievement can motivate me to keep going. I tell myself this, but for the first time, I do not believe it.

A noise outside shakes me from my distress, and I turn toward my window. It allows soft, golden beams to catch my face. It reminds me of late summertime– my favorite season, filled with walks in the early evening glow. As I pause and think, I remember the scent of fresh waffle cones downtown, and the exact bench I sit at to change songs before my trek home. Small, gentle things. It seems I have forgotten to appreciate them.

I get up and venture a bit closer. Thinly lined with dust, the cream-colored windowpane has scattered chips of paint and dented wood. Aging can be so cruel. It makes me remember stretches of time where I too felt broken and beaten. I can feel

my gut twist, as I recall the memories of my heavy sobs, created from a cadence of my own gasps for air. Heartbreak is a tricky thing - equal parts soul crushing and redefining. Striving to love and be loved, especially in this field of work, is no easy task. Despite every up and down, I feel peace and comfort in being with my own presence. At last, alone but not lonely. I rarely admit the strength it took to reach this point.

My gaze lingers outside, where my window overlooks the street. I see an elderly resident in my building. He often rides the elevator around 7:40 am and 5:20 pm, too. I smile to myself, thinking of our small conversations. It did not matter if we talked of the weather or a new restaurant opening nearby, for he somehow made me feel cared for in a short passing of time. Even his small, but intentional smile would brighten my mood. There is something contagious about kind strangers with good hearts. I do not stop to admire that simple joy enough.

In the pursuit of medicine, I fear I often overlook what it means to be human.

Has it always been close? Perhaps not happiness, but rather contentment. It has sat here patiently, surrounding me, yet remaining unclaimed. It is like the window– both nothing and absolutely everything. It is not a place nor a destination, but an element of each day. At last, I take a deep breath.

Caroline Doyle

“In the pursuit of medicine, I fear I often overlook what it means to be human.”

Nobody has seen the tug-of-war match I’ve been having with myself. Choosing to maintain authenticity in medicine often has me feeling like I’m at risk of drowning upstream.

I wish medicine was more than what it is. I wish medicine was less allencompassing in my life. I want to do everything. But at the same time, I don’t want to do most of it. That is, I don’t want to engage in many of the behaviors modeled for me–the detachment, the “professionalism,” the lack of vulnerability. Some people inspire me to do better. Others lead me to believe there’s no point in even trying. Who do I trust to guide me down the right path?

I laugh, joke, excitedly talk to everyone in sight, and I always have a plan brewing. Sometimes I may be blunt, but I am pretty genuine when I express my opinions. I’m not afraid to stand up and say something if I think it’s the right thing to do and that it will help others. I try to read between the lines and notice more than just what people simply say. I like to bring joy to those around me and be there for those who need someone, even when I’m busy. It doesn’t matter with whom; I really just enjoy building connections with people and making others smile.

And yet medical school has presented me with the constant undertone that makes me feel like I have to stop being myself. I hear whispers and unconcealed

comments about me. I don’t usually care and simply ignore them. I don’t like to be the center of attention, but my personality and how I carry myself put me there. I don’t necessarily fit the stereotypical doctor paradigm, and I’m usually fine with that. However, this year I’ve felt more at odds with maintaining my authenticity–more than I have in many years. I feel the pressure to hide who I am to maintain an image. I’ll take criticism and reflect on what I can or should take away from it. But at my core, I know I can’t accept not being me. There is nothing that I appreciate more than when I feel accepted for who I am.

I can be “professional” when I need to, and I can be more muted if the situation requires that. Should being professional in a clinical setting require me to be someone I’m not? I certainly don’t believe so, since that is just one way I’ll choose to present myself to the world. There are many aspects to me that I don’t let many see. I have layers. I’m an onion. A cake. Maybe I’m even an ogre like Shrek.

I’ve been told to “prove myself before I can be myself,” but why can’t I prove myself while being myself?

Why can’t my actions overshadow how I say my words or carry myself? Aren’t actions supposed to speak louder than words?

I don’t really know what medicine expects from me. I know I will never please everyone. The medical system is built on the idea of us pleasing the people we work with. I don’t want to lose myself in search of the golden ticket or golden evaluation that’ll help me get into my dream program. But I also don’t want to stubbornly remain as I am and become a detriment to my team and patients. But why should I change who I fundamentally am to fit into this broken system?

Medical school is a roller coaster in ways I didn’t expect. However, I hope to follow in the footsteps of those who have found a way to inspire me–whether

they know it or not. I may not always feel like I’m heading down the right path, but I think if I remain true to my goals and maintain my authenticity, I’ll enjoy medicine and life more than if I changed just to fit into the system. I wish this was a resolution and this struggle was over, but I know this will be a constant conflict I will face during my career.

How are we supposed to find the balance between remaining our authentic selves and staying afloat in a system that might expect us to act differently? Will I take in the socialization process by osmosis and not even realize who I’m becoming? Maybe I’ll realize I’m changing and let it happen. Will being a little different be acceptable to most people, and I’ve overplayed what I think hospital life is like? Everyone says medical school will change me… transform me. But into what or into whom? Can I go back if I don’t like what I have become? Will anyone even tell me I’m different? Will it be a slow fade only recognizable to those from a distance?

I don’t want to lose what makes me – me.

“I’ve been told to ‘prove myself before I can be myself,’ but why can’t I prove myself while being myself?”

“But why should I change who I fundamentally am to fit into this broken system?”

Doctoring is more than a cold science; it is an expression of being human. In medical school it is easy to forget what it means to physically suffer as we focus so intensely on learning the science of medicine. To be a good doctor you not only need to know the science of medicine, but also the art of being human. Science helps us to heal, but our humanity helps us to comfort. It was not until recently as I held the hand of an elderly woman who was locked in the throes of anxiety by her inability to breathe that I again reckoned with what it means to suffer, just as so many patients do. We medical students are, on the whole, “healthy,” but most of us have experienced bouts of biological dysfunction, and a few of us have experienced significant health issues. I personally have had fits of difficulty breathing either due to trauma, anxiety, or extreme overwork, but I have never had that experience extend for days and gradually worsen over time as that patient had. Often these people are anxious because they are stripped of life’s fundamentals, which we take for granted: things like breathing, eating, thinking, and

moving. We can trust our bodies, but for others, each breath, each heartbeat, and every step can be a struggle, or the very last they’ll ever take.

As a doctor and medical student, it’s easy to get lost in the science and objective goals of care, especially given that the current western medical system prioritizes quantity of patients seen over quality of patient care. However, in spite of this, we must try to keep our humanity through training and practice. We need to be kind to patients, actually listen to them, and not simply check boxes that maximize our pay. We should aim to be doctors who care for their patients in body, spirit, and soul. Most of us did not choose medicine to make money, but rather to help people. We must be conscientious of this premise not only in our individual practices, but also in the medical system as a whole. Through looking beyond ourselves and the

immediate future, we may help not only our personal practice reemphasize the root of our Hippocratic oath, but also those of clinicians who will practice, or are currently practicing, in different specialties.

“Science helps us to heal, but our humanity helps us to comfort.”

Asurprising word to describe American bioethics might be “reactionary.” O. Carter Snead, a law professor and bioethicist, describes the foundation of American bioethics, not as a premediated set of rules, but rather as a reaction to atrocities within the healthcare system. He points to three specific examples: Henry Beecher’s article on the abuses within clinical research, the Tuskegee syphilis study, and NIH debates about research on aborted fetuses before death. Due to the unique inception of American bioethics, which relied heavily on court ruling, Snead argues that an implicit and flawed anthropology has been given by the courts. In his book, What It Means To Be Human, Snead details the history of what he calls “American public bioethics,” and in turn, proposes a new anthropology, which better corresponds to human lived experience.

After detailing court rulings over the years, Snead paints a picture of what a human person is in the eyes of the court by coining the term “expressive individualism,” which is the underlying anthropology of American public bioethics. Expressive individualism states that the “individual, atomized self is the fundamental unit of human reality…the self is defined by its capacity to choose a future pathway that is revealed by the investigation of its own inner depths of sentiment” (86). Personhood is to both reflect and choose how to live one’s life. For Snead, the issue with expressive

individualism is that it does not account for the limitations inherent to the human body.

Instead, Snead offers an anthropology of embodiment, stating, “as living bodies in time, we are vulnerable, dependent, and subject to natural limits, including injury, illness, senescence, and death” (269). Humans undergo cycles of dependence. The opposite of dependence is not independence, but rather giving. He writes, “We need robust and expansive networks of uncalculated giving and ungrateful receiving populated by people who make the good of others their own good, without demand for or expectation of recompense” (269). Snead looks to the human life cycle to support his argument, from radical dependence in the womb, to a self-sufficient middle of life (barring significant illness), to again radical dependence at the end of life.

Snead’s argument is beautiful in that our humanness is tied up to our sense of community. Through giving to others and receiving from others, we enter into an interconnected web of gratitude. By participation in this web, we recognize both our dependence on each other and the inherent limitations of embodiment. Rather than ignoring these limitations of personhood, Snead fully embraces both limitations and charity as fundamental aspects of the human person. This new anthropology allows for recognition of personhood in all forms, from the very young to the very old and from the most dependent to the most independent among us.

Snead, O. Carter. What it means to be human: The case for the body in public bioethics. Harvard University Press, 2020.

“Through giving to others and receiving from others, we enter into an interconnected web of gratitude.”

I’m not sure what “medical humanities” means, but I want to reflect on my summer that involved the intersection between medicine, humans, and cancer, which continues to overwhelm both medicine and humans everyday.

This past summer I had the incredible opportunity to cycle across (most of*) the United States from Baltimore, MD to San Francisco, CA with twenty-four young adults with 4K for Cancer, which is a branch of the Ulman Foundation established to help families who are unwillingly dragged into the world of cancer. All of my teammates had an experience with cancer in some capacity as do 39.5% of Americans 1; however, the intensity and arbitrary nature that the disease struck each of their families was shocking.

Two great friends, J & J, lost their mothers to cancer as young teenagers. My tornado buddy, E, lost his father. B’s fiancé battled Ewing’s Sarcoma until finally succumbing to the horrible disease. Ewing’s is a very rare type of bone cancer (2.93 cases per 1,000,000 children 2) that has a dire prognosis with only ~20% of patients surviving 5 years past their initial diagnosis. My classmates and I actually learned about it during M1 year during the MSK block because of its characteristic clinical appearance of “onion skin” on XR and easily testable translocation of the EWSR1 gene on chr 22 (AMBOSS graphic below). Regardless of these high yield facts, everyone else on the team came to know

and call Ewing’s an absolute stinking heap of s#%! because of the way B described it. People affected by these illnesses don’t care that it has characteristic diagnostic components or certain gene associations. They care that their loved ones are fading in front of their eyes as their own bodies revolt against them and slowly overwhelm various organ systems.

possibly struggling/ hurting) alongside people who are still mentally and even physically hurting from a personal manifestation of these pathologies to strike home the importance of the career medical students are working towards. Smashing a spacebar for Anki for hours or maxing out at 60% correct on UWorld questions can make the goal of becoming a physician and the associated sanctity of being the person that families approach with their broken or failing bodies seem lightyears away. But try to remember, Ewing’s is a complete and total s@!#.

Imprinted into me now is the fact that the diseases and pathologies we study all affect real people. Please, hold your applause as this tidbit is pretty self-evident; yet, in my 1.5 years in medical school so far, it is all too easy to get lost in the weeds of learning to pair a certain gene mutation with a certain disease name. Maybe this is because we are in the pre-clinical, didactic years that primarily consist of rapid fire lectures that move at a pace akin to drinking from a fire hose. It took meeting and befriending (and

* The beginning of M2 year with the renal block forced me to prematurely end my ride at the western border of Utah in Zion National Park.

1 “Cancer Statistics.” National Cancer Institute, 2020, https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/ understanding/statistics.

2 Grohar, Patrick J. “‘Ewing Sarcoma.” National Organization for Rare Disorders, 2013, https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/ewingsarcoma/.

AMBOSS GmbH. Malignant Bone Tumors. https://amboss.com/. Accessed August 28, 2023.

“Imprinted into me now is the fact that the diseases and pathologies we study all affect real people.”

Talal Alomar

In medicine, the humanities play a role, Expanding our minds and touching our soul. Through literature and art, we learn to empathize, And see the world through our patients’ eyes.

We reflect on our biases and values with care, Developing compassion that we can share. With each patient we meet, a story unfolds, And the humanities help us to connect and be bold.

Meditation and reflection become our guide, As we journey with patients side by side. We learn to be humble, self-aware, and kind, And open our hearts to the suffering we find.

In the humanities, we find beauty and grace, A pathway to healing in this sacred space. For medicine is more than just science and cure, It’s the humanity we bring that makes medicine pure.

The hospital is ethereal at 3 in the morning. Halls populated only by the lights overhead and the masks abandoned on the floor. I shuffle down the stairwell into the basement that faintly smells of rotting garbage. The doors to the on call rooms are open, inviting, awaiting their newest occupant.

I’ve never been down here to sleep before. Only to use the coffee machine that sits in a narrow alcove next to the refrigerator.

The trauma bay is a good place to remember your own mortality. She was a little old lady going to the doctor just for a UTI. She crossed the street and got hit by a car. Auto versus ped. Such a kind way to say “someone ran her over.”

We run through the primary survey as planned and start the secondary until someone realizes she has no pulse. It takes 3 rounds to bring her back and get her stable enough to get to the CT scan We need to see what’s happened with the massive

subdural hemorrhage they saw in her brain before she got here. Of course it’s bigger. Let’s start mannitol. As if that can do anything for the blood compressing her brain against the other side of her skull I keep my eyes on the blood pressure monitor feeling my own heart race each time the numbers disappear Is the reader cycling again or is her pressure so low the machine can’t find it? It’s the latter. Let’s start CPR again. I help this time. It’s a lot higher stakes when the body below my hands is a person and not a plastic mannikin. My shoulders are screaming fatigue but I can’t slow down. This might be the only thing keeping her heart going right now. Her belly flops like a dying fish, air squelching from the edges of the ET tube Her pulse comes back just in time for her son to call and tell us she’s DNR. We frantically clean her off wiping blood off her chest and putting her limp body in a gown so she can try to keep some dignity as her son comes in to say goodbye. Is it disrespectful, I wonder to pull out my phone while her family is ten feet away in the other room waiting for her to die?

It is enough for the birds – hear them chatter! It is enough for the citrus tree, brimming with ample golden ornaments. It is enough for the wrinkle-faced woman pedaling her bike and smiling as I pass, for the daisies bursting beyond the bounds of the planter box and the brown-and-white cat sponging up sunlight from his owner’s lap.

This world, exactly as it is, was enough for the child who wrote “U R Ama-zing” in sun-bleached letters upon the sidewalk, for the muralist who took inspiration in Saguaro-scattered peaks, an iris desert sky.

It is enough to be in this world in a body that breathes, feels the rustling breeze, walks, sees.

~It takes only three blocks to remember this~

I, exactly as I am, am enough.

Before I felt the pull of blue ribbons, report cards or learned the omnipotence of the stopwatch, the hierarchy of gold-silver-bronze, the hierarchy of high-school adolescents, and long before I ever learned the word “pretty—”

Before the scrabble of GPAs and MCATs, alphabets of essays and acceptance (and rejection) letters, and long before my worth was delineated on 5 pages of my CV, ever-haunted by some phantom algorithmic likelihood of matching—

My parents held me, fuzzy-headed full-of-wonder, and loved me. I should remember that more often

It is their will to be here. Why here? (In this cold laboratory). Why with these strangers? (Ignorant of their strife).

It is their will to be here. Perhaps to fulfill a mission, Perhaps to bestow a blessing. Perhaps to teach a lesson, Perhaps to save a life.

It is their will to be here. And I cannot help but wonder, In the hours spent in study, And in the hours ever after, If I have understood.

It is their will to be here, That I too may fulfill a mission, That I too may bestow a blessing, That I too may teach a lesson, That I too may save a life.

Mothers and fathers, Sons and daughters, Brothers and sisters, It is your will to be here —And for that, I thank you.

Joseph

DausImagine your office is your living room and the patient presented to you is whom? It’s your partner

Your best friend

What do you do when this happens to you?

Do you go to the ER again to find out what’s wrong? Have them sit in their pain for so long? You wait for an answer but only get dread. “It’s Psychosomatic; It’s all in your head.”

They shuffle you out and you just want to shout, But you’re not a physician or PhD. You have a glorified Biology degree. A level of knowledge that gets you in trouble. Medical students are known for being neurotic, You can’t hunt for zebras; it’s idiotic.

You decide to stay quiet. Don’t start a riot. Trust the process. Try not to stress.

You try and you try. The try becomes a lie. Every day unknowing is another day of showing That our quest for the answers can become a cancer. It festers inside until it can’t hide.

Metastasize

You continue to promote positivity. But the tests aren’t conclusive. The diagnosis is elusive. The thoughts are intrusive.

They’re poked and they’re prodded. They tell the same story to be left with a bill and an allegory. A loved one in peril reveals the true falling Of two systems damaged; hers and my calling. So what do you do if this happens to you? I wish I had the answer.

Keep love in your heart and remember your purpose. Live life for others and do it through service. Be the change that you want to see. You’ll never have all the answers.

When navigating the busy life of a medical student, I think we often have trouble finding time to process the things we see. The medical profession exposes us to the highest of highs; yet, consequently, also reveals to us the lowest of lows. While our schedules may be busy, I feel that music is one way for me to take a step back and allow myself to work through my feelings. Although we, as medical students, may choose to focus on the “highs” we experience, I feel it is important for us to feel the “lows” as well. When struggling with a heavy emotional burden, I have been able to look toward Taylor Swift’s epiphany always comes to mind. While Swift specifically wrote part of the song alluding to the struggles of medical workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, I would suggest that the overall melancholic tone carries a more universal feeling that many of us students have experienced at one point or another. In those moments, I can hear the echo of the bridge of this song as I simply allow myself to process my experiences.

“Only twenty minutes to sleep

But you dream of some epiphany

Just one single glimpse of relief

To make some sense of what you’ve seen.”

Sometimes, as Swift suggests, we need time to make sense. Doctors, after all, are only human, too.

Jonathan Abdo

Jonathan Abdo

2020 was the first year I experienced the death of someone I loved. I lost both my grandparents, Alejandro and Sylvia Ramirez, within weeks of each other. The worst part was that I hadn’t made an effort to see them in person for a few years. My grandfather succumbed to esophageal cancer, passing away within a week of his diagnosis. Only a couple of weeks later, my grandmother moved from Beaumont, Texas to Arizona to stay with my family. Soon she was hospitalized from complications due to diabetes-- we were left with no other option than to take her off life support. I can’t really articulate what changed in me from that point on. I felt like I lost my people without a moment to catch my breath.

Eventually, I wrote a song that I named “Call Me Sometime,” which is dedicated to their memory. When it comes to words, I am not much of a craftsman, but I hope that through this song, I can convey the regret I hold for not making more of an effort to let them know how much they meant to me and the sadness that lingers with me every week that I wish I could call them. I used inspiration from the songs “Maggot Brain” by Funkadelic and “Echoes” by Pink Floyd to craft a 6-minute solo which concludes with the final voicemail I had saved from my granny.

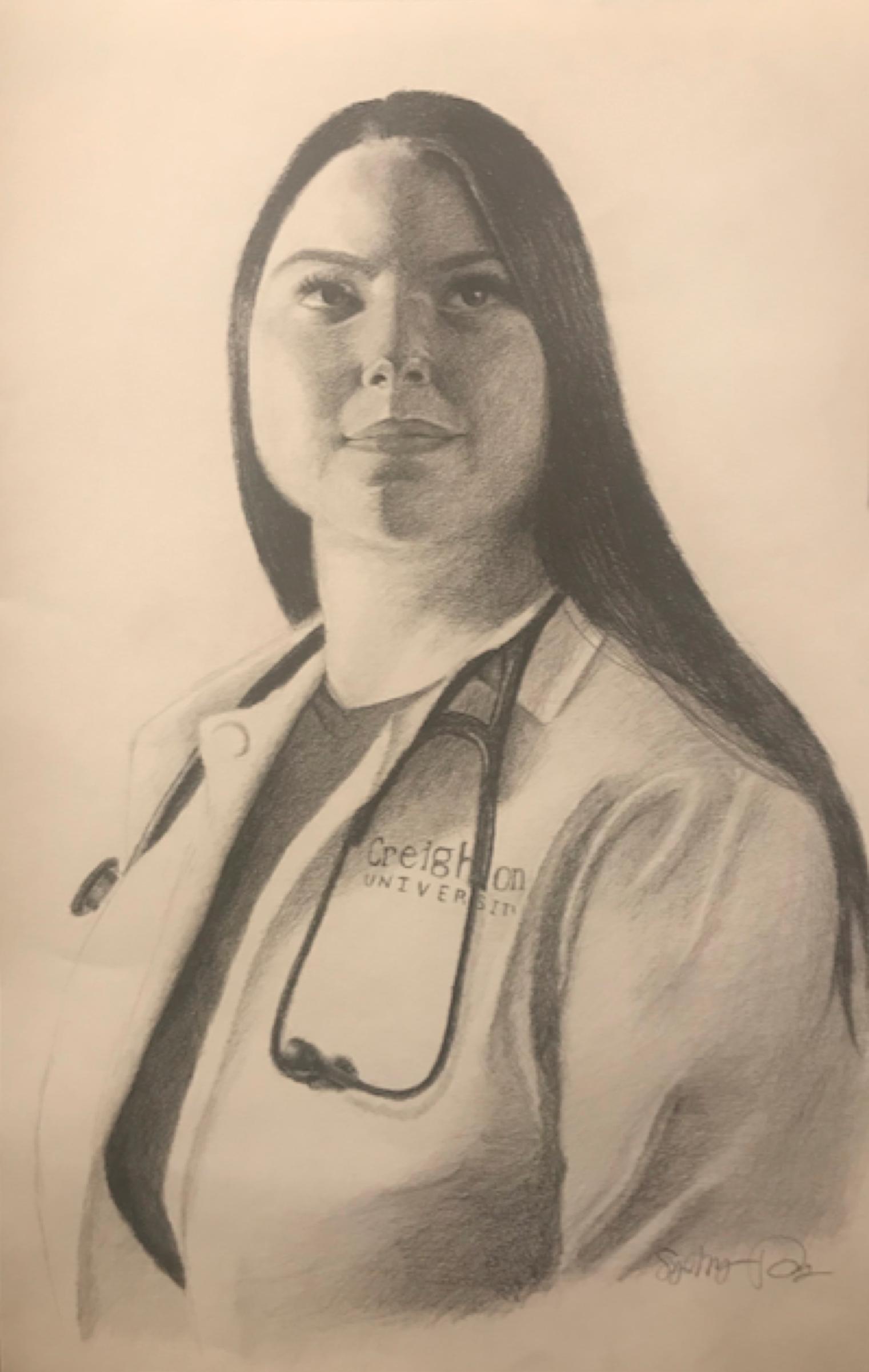

Biography: Bethany successfully matched this past spring. At the time of meeting her and writing this piece, she was an M2.

Bethany grew up in Rome, GA, a quaint town at the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. She has two younger siblings and believes her love to care for them strongly influenced her path to medicine. Bethany’s inspiration to become a doctor came from her mom, who was both an outpatient and school nurse. Other students would often come up to Bethany and tell her how much her mom made them feel better both physically and mentally. Bethany knew she wanted to be the same comforting, healing presence for others. Bethany’s mom passed away suddenly during her third month of medical school, but she hopes to continue her mom’s legacy.

As of now, Bethany is still unsure about her specialty of choice. She started medical school with interests in OB-GYN, and has since jumped around to ER, surgery, and other disciplines. She misses her family very much, but also yearns to return to the mountains of Colorado, where she lived for a year as a case manager at a nonprofit. Although she has many different dreams, she wishes to work in underserved communities, and believes she will likely move to wherever her sister is— her best friend. Bethany hopes to never lose sight of what is important in life.

What preconceptions did you have coming into medical school? What was something you did not expect?

“Basically, I went into med school thinking I’m just going to study and I’m going to make all these friends…Then I had the white coat ceremony, and everything was pretty much what I expected for two months. And then my mom died really unexpectedly. I was studying at the cardiac center on a Sunday morning and got a call from my grandmother who had not heard from my mom all day and went to her house and found her. She had a pulmonary embolism, basically a blood clot in your lungs, and died immediately.

After that moment in time, it totally changed. Nothing really changed day-to-day, but it was mentally much harder after that. I went home for about two weeks. My mom is single, and I have a little sister and my mother’s estate to take care of. I came back to school and basically didn’t have a break until the end of the year. It was impossible for me to make friends. Schedule wise, I just think medical school has been pretty much like what I expected, but emotionally and socially it’s been a lot harder. Then obviously COVID hit. Not what I expected because my life got turned upside down.

But being at a Jesuit medical school, I found support when I met Fr. Osborne, and he put together this group of people who have lost their parents either during or right before medical school started. We met regularly over the last year, and so, I’ve met some of my friends through that.”

Biography: Suhail is currently an M4 at Creighton SOM. At the time of meeting him and writing this piece, he was an M1.

Suhail is a suburban kid from Fremont, CA. While he feels his upbringing was influenced by the pressures of the Bay Area, he always managed to make time for what he loved: throwing shotput and discus and pursuing a degree in psychology. Suhail’s time at UC Davis was an extremely formative experience that helped him develop hobbies and an interest in medicine.

During his junior year of college, Suhail was diagnosed with idiopathic duct-centric pancreatitis. Luckily, he had incredible doctors. Afterwards, Suhail found himself drawn to a career in helping others. He shadowed Dr. Smith, whose close relationship with his patients and respect for evidence-based practices drew him to pursue medicine.

As a volunteer tutor at juvenile hall, Suhail led a weekly seminar titled “Storms to Success.” His primary goal was to teach the youth life skills that would help them assimilate back into society. Despite coming from different backgrounds, Suhail and his students dealt with similar academic or familial issues. Understanding his students’ perspectives was instrumental to help them. Suhail noticed the parallels between his relationship with the youth and that of a doctor-patient. He learned about the importance of psychological understanding in medicine.

Unlike many applicants who major in STEM, Suhail’s psychology degree motivated him to pursue a human-centered research position. He started working for LiquidGoldConcept (LGC), a breast health

and lactation education company. As a project manager, Suhail was lead investigator on the most comprehensive breastfeeding application review to date. He oversaw the sample selection, extracted the data, and wrote the manuscript. The most rewarding aspect of his research is that he helped mothers make informed decisions. Suhail hopes to continue to bridge the gap between app developers, physicians, and consumers.

While Suhail was initially intimidated to enter a predominantly female industry, his time at LGC was transformative. He presented at three conferences and published a paper in JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting (https://pediatrics.jmir.org/2019/1/ e12364/). Using the lessons learned from his unorthodox work experience, Suhail will uniquely approach problems in medicine.

How have you managed imposter syndrome?

“With lots of humor…In three years, I’m going to be finished with MD. In a few years, I’ll be a resident. That is crazy to me…But just look back and realize that you belong here.”

How do you think that medical humanities have impacted your education so far? “We do a gold track session every week or two that stresses medical humanities, and I’ll be honest, I cannot say that it’s impacted me currently because I’m not a physician yet. I’m not in the trenches…But I can say with confidence that it’s gotten these discussions started early, thinking about racism and healthcare. I need to start thinking about end-of-life decisions for patients… Having these difficult discussions early is important so that you can start forming the right ways to think…The fact that we’re broaching these conversations is wonderful.”

Biography: Taylor is currently an M4 at Creighton SOM. At the time of meeting her and writing this piece, she was an M1.

Growing up in a small town at the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, Taylor dreamed of living in a big city. When senior year came, she only applied to colleges on the East Coast. She accepted a four-year scholarship to Boston University.

During her first semester of college, Taylor began volunteering as an advocate for families in the Pediatrics Primary Care Clinic. One family stands out: a younger mother and two sons, whom they guided toward resources such as food banks. This relationship showed Taylor that her role with the program was more than just reciting a list of organizations; she had grown to be part of a support system. This work inspired her career goals, and Taylor changed her major from undecided to Human Physiology with Public Health.

Throughout college, Taylor also engaged in HPV vaccination research projects, an internship at a Public Health Department, and involvement with her sorority. Taylor decided to apply for medical school and work as a scribe during her gap year. Ultimately, Taylor decided to attend Creighton. She connected heavily to the Jesuit mission statement and was ecstatic to begin.

Taylor is now just weeks away from finishing her first year, and it feels like yesterday she received her white coat. Classes make time fly, as Taylor spends most of her day studying. Since being in Omaha, Taylor has met countless new friends and

found new hobbies such as Orange Theory Fitness classes. This summer, she is planning to participate in several weeks of career exploration through Creighton, which allows students to shadow physicians in various fields.

Though she is undecided on her future specialty, Taylor is excited for her future in medicine. Her significant other, Jake, will be finishing his Doctorate in Physical Therapy this summer and hopefully joining her in Omaha shortly after. She is also the proud mom of two guinea pigs. Taylor chose to participate in this portrait project to connect with and mentor other students at Creighton.

What preconceptions did you have coming in and what has been the reality? “Coming into medical school, I was really intimidated by everyone…No one is flaunting their accomplishments or anything. Everyone just wants to make sure you have friends and that you’re doing okay. There’s a big community aspect of medical school that I guess I didn’t anticipate; we have a really large resource drive with all of our textbooks…it’s really collaborative.

I guess I wasn’t expecting this great community, and not every school has that. Some of my friends go to schools where they feel they’re competing against everyone all the time, which is so stressful. And I’m glad Creighton kind of mitigates that and makes sure everyone’s on a level playing field.”

Sydney Dang graduated from Creighton University May 2021 with her Bachelor of Science, majoring in Biology and Studio Art and in 2023 with her Master of Science in Medical Sciences. Coming from a small private school in Phoenix, Arizona, Creighton was the perfect opportunity for her to step outside of her comfort zone, but still find support. Her two favorite Jesuit values are “women and men for and with others” and “forming and educating agents of change.”

During her fall breaks in 2017 and 2018, Sydney participated in Service and Justice Trips through the Schlegel Center for Service and Justice. On her first trip, she expected it to be mostly manual labor, living out the service part of the trip. What she took away was that there are many ways to aid a population. Listening, becoming educated, and advocacy can be just as powerful as manual service. She met with families on Temporary Protective Status and listened to their struggles of leaving a violent home country. This experience inspired the topic for a class presentation, in which she educated her peers on Temporary Protective Status and ways to advocate for those families.

Sydney credits Creighton’s Magis Core as well as Professor Rachel Mindrup for steering her toward an Art major. She originally

planned to focus solely on her premedicine coursework but found the addition of her art major to be formative in her understanding of patient care. During a joint drawing session with medical students and undergraduates, Prof. Rachel Mindrup asked her medical students to pose for 5-minute sessions when the scheduled model was canceled. The most impactful interaction was when a student was asked about the discomfort of having several eyes staring at him as he was drawn. He remarked that the pose he was holding with his arms in the air was too painful to focus on the staring eyes. Prof. Mindrup remarked on the similarities between this student’s pain and discomfort to a patient being examined by a healthcare provider.

Art has also helped Sydney in her clinical applications as a nurse aid, as her attention to detail has translated to patient assessment skills. Sydney has noted that the ability to be adaptable is also a skill required by science and art. Limited color pallets or changing lighting conditions can draw parallels to hospital supply shortages or the changing nature of a patient’s health.

Sydney recently presented her master’s capstone project this past May exploring the intersections of art, the body, and medicine. She is now an M1 at Creighton School of Medicine Phoenix campus.